Abstract

The increasing demand for continuous and reliable air traffic surveillance over remote and oceanic regions has prompted the exploration of innovative solutions beyond traditional radar and satellite-based systems. In this context, High-Altitude Pseudo-Satellites (HAPSs) have emerged as a promising technology capable of extending surveillance and communication coverage within the stratosphere at significantly lower cost and greater operational flexibility. This paper presents the results of Research and Development (R&D) efforts focused on the conceptualization and development of a HAPS prototype serving as a proof of concept to enhance Air Traffic Management (ATM) surveillance capabilities. The study quantitatively examines the HAPS operational environment by classifying and evaluating the geometric, physical, environmental, thermal and atmospheric factors influencing prototype performance. The developed prototype establishes a scalable foundation for future multi-platform HAPS networks, and forthcoming research will focus on experimental validation under real-world conditions and performance optimization to enable integration into next-generation ATM systems.

1. Introduction

Although the fundamental principles of Air Traffic Control (ATC) have remained largely unchanged since the 1920s, the operating environment in which it functions has evolved significantly [1]. Technology in its many forms has long been a key enabler in delivering and improving safe and efficient air transport services. Thereby, the field of Earth observation has grown rapidly, primarily driven by advancements in the satellite industry. As a result, in both telecommunications and aviation, service provision nowadays relies on a hybrid architecture combining satellite and terrestrial networks, a concept that also applies to aircraft surveillance and navigation.

The introduction of Automatic Dependent Surveillance–Broadcast (ADS-B) represents a major advancement in global surveillance capabilities. By broadcasting aircraft position and intent data, ADS-B strengthens situational awareness and introduces an additional layer of redundancy to the existing navigation infrastructure. Recognized by the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) as a next-generation ATC surveillance system [2], ADS-B has become mandatory for most commercial aircraft operations worldwide since 2020. However, with approximately 71% of Earth’s surface covered by oceans, the reach of terrestrial surveillance remains limited. Gaps also persist in remote regions, at low altitudes, and within mountainous areas where ground infrastructure cannot provide adequate coverage [3,4,5].

High-Altitude Pseudo-Satellites have emerged as a promising technological solution which can address these limitations. Operating in the stratosphere, HAPS platforms can provide persistent coverage for wireless communication, surveillance and Earth observation missions at a fraction of the cost of Low Earth Orbit (LEO) or Geostationary Earth Orbit (GEO) satellites [6,7,8,9,10]. They maintain constant line-of-sight connectivity, enabling high-quality communication links and continuous regional monitoring. Current HAPS designs can sustain flight for extended durations, ranging from several days to several months, with mission endurance expected to increase further as technology matures.

Although still in the early stages of technological development, HAPS platforms hold substantial potential for operational use in surveillance, navigation and safety, as well as for complementing existing ATM systems. Looking ahead, initial HAPS operations under specific regulatory frameworks are expected to commence in the European Union between 2025 and 2030. During this period, the number and diversity of HAPS platforms are projected to grow significantly as new manufacturers and operators enter the market.

This research paper presents the results of R&D efforts focused on the conceptualization and development of a HAPS prototype developed to enhance ATM surveillance capabilities. The prototype is designed as a short-lived balloon and is used solely for demonstration and concept validation, not as an ultimate operational solution. Long-endurance alternatives, such as solar-powered HAPS or zero-pressure balloons, are identified as future operational candidates. The main motivation of this research is to explore whether, how, and when HAPS can effectively address current operational gaps or complement existing communication, navigation and surveillance (CNS) systems. The paper introduces a comprehensive framework for a stratospheric HAPS-based ADS-B surveillance platform, combining platform design, environmental modeling, payload constraints and operational feasibility into a unified concept. It provides a technical overview of the prototype’s conceptualization and development, supported by mathematical formulations describing its design and behavior. The novelty of this work lies in the integration of these elements into a scalable HAPS-based surveillance architecture, enabling a systematic assessment of geometric, physical, environmental, thermal, and atmospheric factors influencing performance. A deeper understanding of these conditions and effects is expected to support future R&D initiatives, particularly in the refinement of flight performance models from launch, ascent and descent phases to landing.

2. Research Background

Traditional radar surveillance systems remain limited in range. For instance, dedicated terminal Primary Surveillance Radar (PSR) systems typically achieve a maximum detection range of about 60 Nautical Miles (NM), while en-route PSR systems extend between 100 and 250 NM. Secondary Surveillance Radar (SSR) systems, operating at interrogation and response frequencies of 1030 MHz and 1090 MHz, respectively, generally achieve comparable ranges under ideal conditions [11]. Thereby, terrestrial ADS-B systems exhibit similar constraints as traditional radar surveillance systems, leaving significant coverage gaps at low altitudes, over mountainous regions and across oceanic areas. Apart from coverage issues, ADS-B systems may also exhibit losses in data and signal quality in areas of high signal saturation. This manifests as a signal latency within the CNS network and a decrease in the overall performance of ADS-B as a primary surveillance method. However, empirical evidence substantiating the performance of ADS-B signal exchange via ground-based station networks in highly congested environments, as identified by Bagarić et al. [12], is limited and remains insufficiently substantiated in the literature [13].

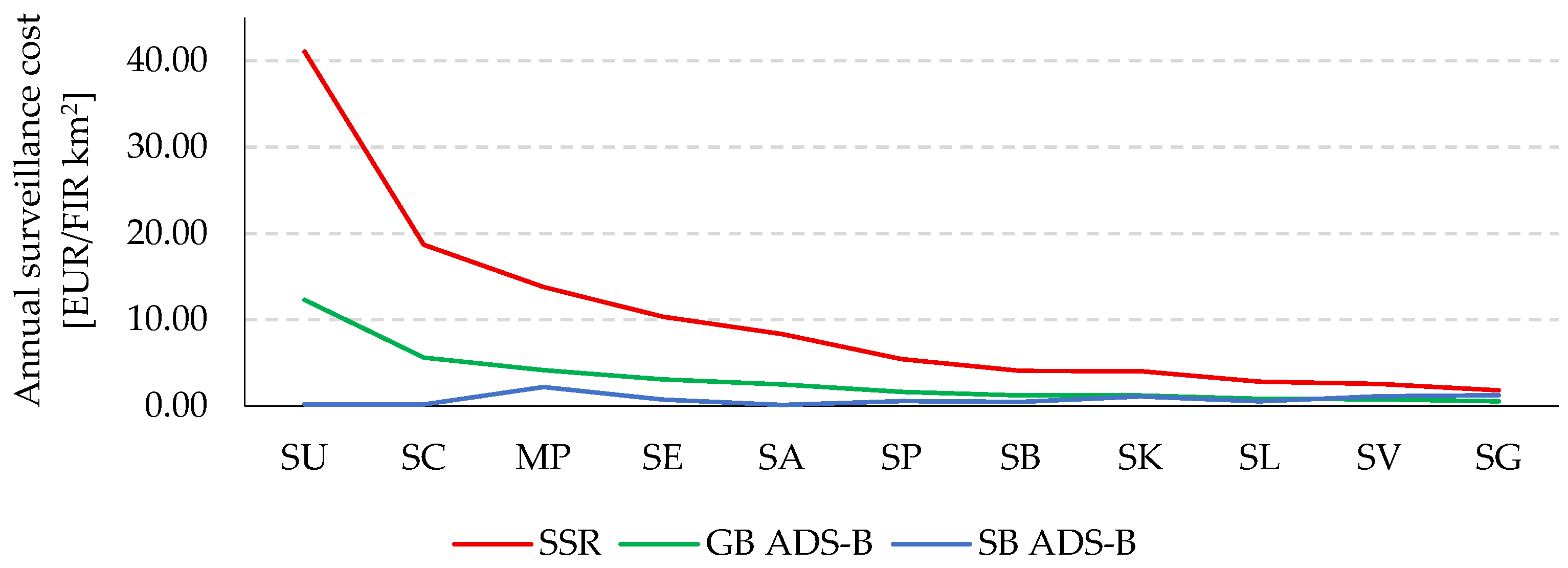

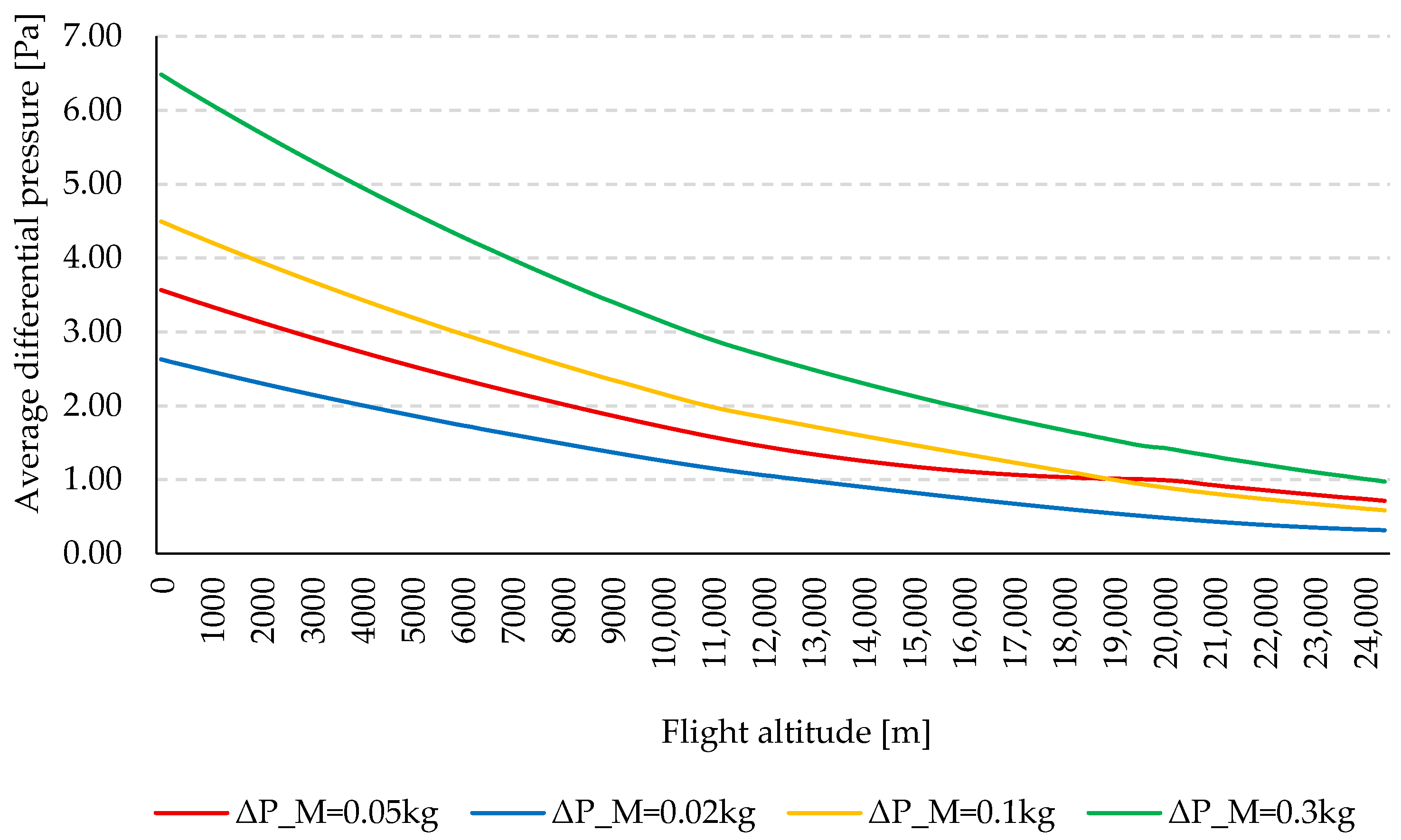

The successful development, deployment and commercialization of Space-Based Automatic Dependent Surveillance–Broadcast (SB ADS-B) technology marked a major milestone for the aviation industry. Moreover, the deployment of SB ADS-B technology represents a transformative step for the ATM system, enabling satellite-based surveillance and reducing dependency on costly ground infrastructure [14]. SB ADS-B extends real-time aircraft tracking to remote and oceanic regions, allowing for reduced separation minima and the transition from procedural to surveillance-based control. For instance, the world’s first operational SB ADS-B system, developed by Aireon LLC (McLean, VA, USA), has already demonstrated the viability of space-based aircraft tracking. Similar initiatives are emerging in China [15,16], Canada [17], Denmark [18] and Germany [19]. Jaya et al. [20] report on the feasibility of SB ADS-B technology in Indonesia and highlight its comparative advantages over GB ADS-B systems. In Papua New Guinea, as of 2019, the SB ADS-B system maintains an operational availability exceeding 99.9% and delivers position reports with a signal latency of 1.5 s [21]. Also, back in 2024, several International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) Member States in the Asia/Pacific (APAC) region initiated studies to evaluate the applicability of SB ADS-B, particularly to enhance aircraft separation in oceanic airspace [22]. Furthermore, according to the ICAO’s South American (SAM) Region analysis [23], the annual cost of SB ADS-B-based surveillance per square kilometer of Flight Information Region (FIR) ranges between €0.14 and €2.19. This represents a reduction of €0.67–38.80 compared to SSR-based surveillance, and €0.18–15.48 less than Ground-Based (GB) ADS-B solutions, depending on the region’s geography and infrastructure. Nevertheless, strategic priorities, such as sovereignty and national independence, often outweigh purely economic considerations, motivating states to explore domestically controlled surveillance solutions. Figure 1 shows the distribution of annual surveillance costs per ICAO SAM Member States, as per ICAO nomenclature.

Figure 1.

Comparative overview of annual surveillance costs per ICAO SAM Member States.

While satellites provide global coverage, they remain expensive and inflexible. In this context, HAPSs offer a complementary approach. Operating at stratospheric altitudes, ADS-B equipped HAPSs can overcome many limitations of GB and SB systems, offering a cost-effective alternative with enhanced line-of-sight coverage, resilience and redundancy. Unlike satellites, HAPSs can be rapidly deployed over targeted regions, enabling flexibility and rapid scalability. In that context, Di Vito et al. [24] highlight that HAPSs can provide emergency surveillance over high-risk areas, such as natural disasters, terrorist acts, Search and Rescue (SAR) operations, etc., before, during and after such events. Most importantly, ADS-B-equipped HAPSs mitigate reliance on third-party providers of SB ADS-B coverage. Beyond purely economic considerations, they also overcome issues of sovereignty and national independence, motivating states to pursue domestically controlled SB ADS-B solutions. Furthermore, the potential for HAPSs to be owned and operated by private or institutional stakeholders from civil or military domains creates new market opportunities and fosters market competition, particularly as inputs derived from SB ADS-B solutions are expected to become an integral component of the future ATM system [25]. However, unlike SB ADS-B, HAPSs do not inherently provide global coverage, underscoring their role as a complementary rather than a replacement technology. This limitation can be mitigated through the deployment of an interoperable multi-platform HAPS constellation. In that regard, Karabulut Kurt et al. [26] envision the future with a massive constellation of HAPSs, termed as a HAPS mega-constellation, enabling high-capacity network access, computation offloading and data processing applications, whereby each HAPS should have a wide footprint of about 500 km in radius [27]. Simultaneously, this brings new challenges, including constellation design, service quality optimization and coordination among HAPSs to prevent interference or coverage overlapping [28]. As such, the next-generation challenge lies in ensuring accessibility and scalability of such technology at the lowest possible unit cost.

Public awareness of High-Altitude Pseudo-Satellites increased significantly following several incidents involving unidentified stratospheric platforms. Since September 2025, Europe has experienced a growing number of airspace incursion events caused by high-altitude balloons violating Lithuanian and Polish airspace. These incursions resulted in temporary air traffic flow restrictions and multiple airport closures, exceeding 15 occurrences, leading to the disruption of thousands of flight operations, particularly during periods of northwesterly winds originating from Belarus. Notably, the widely reported case of HAPSs operating over the United States was ultimately shut down by USAF U-2 aircraft [29]. Although such events remain insufficiently addressed in the scientific literature, where HAPSs are more frequently discussed as instruments for the prevention of unlawful activities rather than as sources of disruption [30,31], they nonetheless demonstrate the operational feasibility of balloon-based HAPS concepts and indicate their increasing frequency and global presence. Moreover, the limited body of existing literature reflects a lack of established prevention mechanisms and highlights a significant misalignment in terms of surveillance, detection and ATM system readiness to accommodate the growing presence of HAPS operations. Ultimately, these events have underscored both the surveillance potential and the regulatory ambiguity surrounding HAPSs, stimulating international discussion on their civilian, military, strategic and tactical applications.

From a regulatory perspective, flight operations above Flight Level (FL) FL660, i.e., within the upper airspace or near-space domain, remain under active review. In the United States, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) are developing the Upper-Class E Airspace Traffic Management Concept of Operations [32], addressing the management of operations transiting to and from these altitudes. This concept emphasizes cooperative digital information sharing to complement conventional ATC services where traditional radar surveillance systems are limited [33]. Similarly, in Europe, the European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) has, since 2023 [34], initiated preparatory work on a regulatory framework expected by 2030, which will enable higher airspace operations under controlled conditions [35]. The literature review also outlines scientific and market analyses conducted as part of the European Higher Airspace Operations (HAO) project, which highlight the need for harmonized safety, traffic management and environmental standards to accommodate emerging vehicle types, including high-altitude platforms and stratospheric vehicles, and identify regulatory gaps that must be addressed to support innovation while maintaining safety [36,37]. Also, the literature review highlights that in addition to air traffic considerations, legal challenges persist due to the absence of clearly defined boundaries between national airspace and outer space, creating an ambiguous regulatory environment for near-space operations that demand cohesive international and national legal frameworks [38].

The suitability of HAPS platforms as contenders for CNS system augmentation is well substantiated through the development of Concepts of operations (CONOPS) for HAPS integration into high-altitude operations within the Single European Sky ATM Research (SESAR) project, coordinated by EUROCONTROL [39]. CONOPS explicitly recognize HAPS among new entrants that require tailored procedures and performance requirements for safe integration into the ATM environment, given their unique operational characteristics compared to conventional aircraft [40]. Additionally, the European Concept for Higher Altitude Operations (ECHO) project aims to confirm the operational feasibility of integrating HAPS into the ATM system, among other objectives. Live simulations carried out under the ECHO2 work program have tested specific operational procedures for HAPS within controlled airspace, including 4-dimensional trajectory management and reserved airspace volumes to minimize disruption to traditional traffic flows [41].

The successful validation of HAPS integration into the ATM system, particularly regarding safe separation assurance, efficient air traffic flow and effective airspace management, is widely recognized as essential for future HAPS operational deployment and regulatory endorsement. Thereby, the literature review emphasizes that integrating platforms such as HAPS into the ATM system requires first addressing existing communication, navigation and surveillance performance gaps inherent in legacy CNS infrastructure.

This study differs from and complements the existing literature in the field of study by shifting focus from evaluating HAPS as an integrated element of the ATM system to the conceptualization and development of a HAPS prototype itself. Accordingly, it provides analytical and conceptual contributions that establish foundational technical insights and support the design of HAPS-based ATM support functions.

An applied research approach is particularly relevant in the context of HAPSs’ technical properties and resistance, as, despite their promise, HAPS operations face formidable operational and atmospheric challenges. The stratosphere presents one of the harshest operational conditions within the aviation industry, including physical, environmental, thermal and atmospheric conditions and effects. In that respect, i.e., given the technical, regulatory and economic significance of HAPS development, this research contributes to the growing body of scientific literature by detailing the conceptualization and development of a HAPS prototype capable of maintaining stable flight within near-space altitudes. Building upon previous studies [42,43,44,45,46] on the feasibility of accurately detecting and tracking aircraft-transmitted ADS-B signals using satellite-borne receivers, this study extends the investigation toward the development of a low-cost, scalable HAPS prototype for surveillance applications.

3. Prototype Conceptualization and Development

3.1. Conceptualization Phase Review

The conceptual framework applied and supporting the later development of the HAPS prototype was derived from the need to conceptualize and develop an unmanned aerial system capable of sustained operations. The prototype must endure extreme environmental conditions, such as air temperatures as low as −90 °C; intense solar, ultraviolet and cosmic radiation; and significantly reduced atmospheric pressure. Therefore, within the conceptual framework, and later materials and components selection and development, know-how is needed to ensure structural resilience, operational efficiency and reliability under demanding environmental conditions.

3.1.1. Prototype Platform Conceptualization

The platform is conceptualized as a self-bursting stratospheric sounding balloon capable of sustained high-altitude flight above FL660 (66,000 ft) and designed to reach altitudes of approximately 80,000 feet (24,400 m) Above Mean Sea Level (AMSL). The initial configuration employs a high-altitude balloon for preliminary testing, serving as a scalable and low-cost solution during early development phases. In the long term, the concept foresees a transition to high-altitude zero-pressure balloons, which are widely recognized as accessible and cost-effective platforms for near-space research and technology validation [47,48,49,50,51].

Geometric and Physical Conditions and Effects

The high-altitude platform balloon is filled with helium (He), a monoatomic gas with a density lower than that of air, for which the dynamic viscosity (He) and thermal conductivity (kHe) vary as functions of the helium gas temperature:

where THe denotes the temperature of helium [K]. Thereby, to determine the fundamental geometrical and physical parameters of the prototype platform, a set of equations was applied to describe the unconstrained volume, balloon diameter, height, surface area of the balloon envelope, and the resulting buoyant differential pressure. The unconstrained volume (Vb) may be approximated as:

where MHe denotes the mass of the lifting gas [kg], RHe denotes the specific gas constant [J/kg·K], while PHe notes gas pressure inside the balloon [Pa]. Balloon diameter (Db) in a top view is quantified as:

where ρHe denotes the gas density [kg/m3]. The length of gore (Lb) exposed in the bubble, denoting the fabric segment forming the balloon surface, equals:

while the surface area of the balloon (Ab) may be approximated using the diameter or volume of the balloon:

The top projected area of the balloon (Tb) is determined as:

while the height of the balloon envelope (Hb) is approximated by:

As the balloon ascends, the balloon, i.e., the helium, expands due to temperature change and decreasing atmospheric pressure, resulting in an increase in volume and a corresponding decrease in gas density. Approximate average differential pressure (∆P) due to buoyancy forces between the internal helium temperature and the ambient atmosphere can be calculated as:

where g denotes gravitational acceleration [m/s2], while ρair marks air density [kg/m3] that can be estimated through the perfect gas law as follows:

where Rair represents the gas constant for air, TA denotes ambient temperature (12), while Pair marks pressure (13) for the troposphere and stratosphere; the latter two are given by:

The net buoyancy of the balloon varies in response to variations in differential pressure throughout the flight. The variations in differential pressure occur due to changes in environmental, thermal and atmospheric conditions. For instance, changes in the surrounding atmospheric temperature, air pressure, air density, thermal radiation and gravitational acceleration throughout the flight directly or indirectly affect buoyancy, i.e., the internal helium temperature and helium mass of the balloon [52].

Environmental Conditions and Effects

The conceptualization of the prototype requires a detailed assessment of environmental conditions that prevail in the lower stratosphere and their influence on the platform’s structure and propulsion. For instance, at altitudes typical for HAPS operation, the ambient temperature can fall below −60 °C. As a result, this extreme thermal environment affects material behavior, power system performance, and energy storage efficiency. Also, air density in the stratosphere is less than 10% of its sea-level value, substantially reducing aerodynamic lift and cooling efficiency.

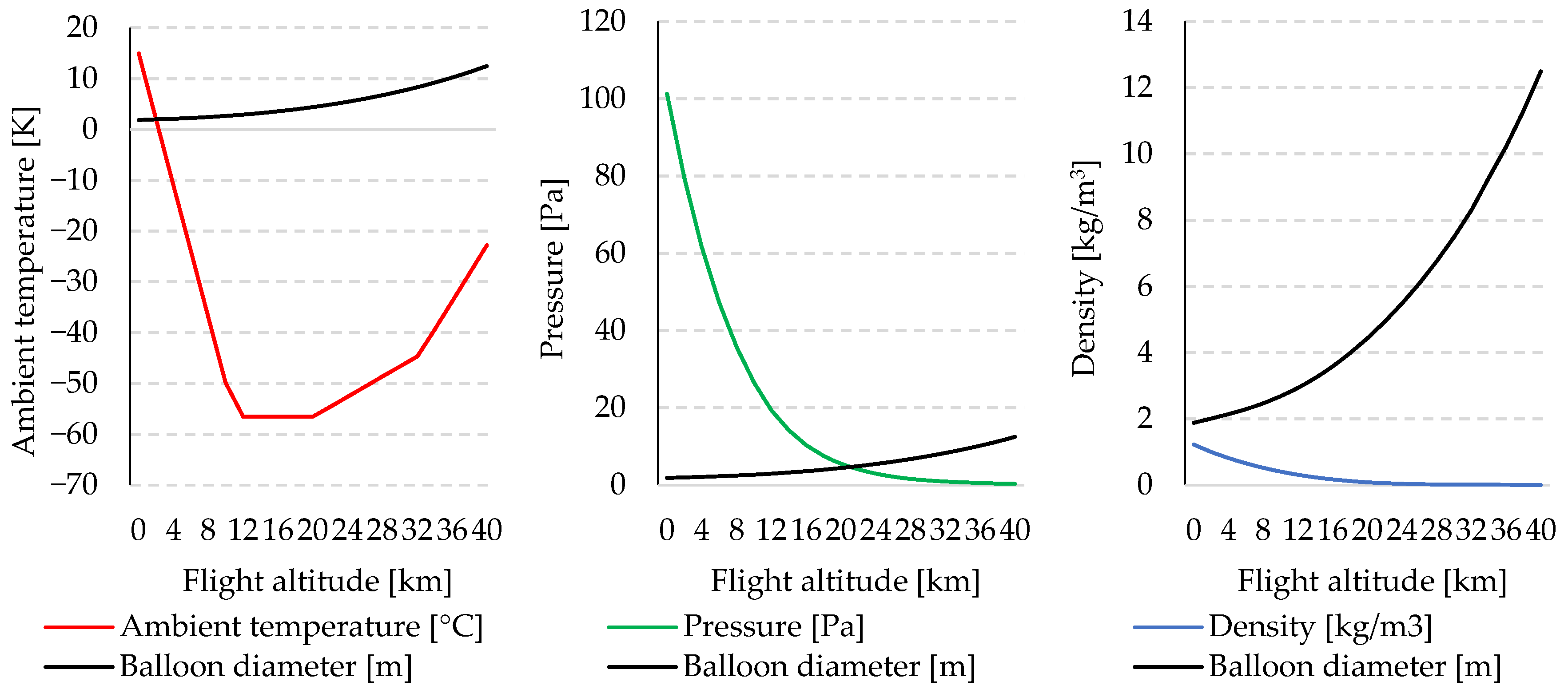

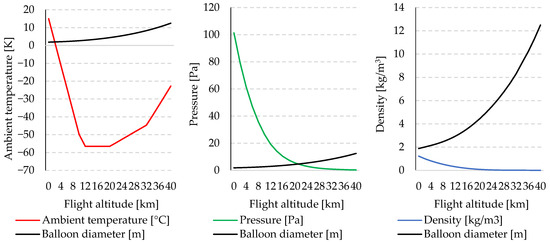

Wind conditions and turbulence at stratospheric altitudes, although generally lower in magnitude than those in the troposphere, exhibit considerable spatial and temporal variability [53,54]. In the presence of horizontal wind components, the prototype platform is subject to both horizontal drift and induced vertical oscillations. Consequently, regardless of the structural design and aerodynamic features incorporated during prototype conceptualization, the expectation of achieving universal station-keeping remains unattainable without the integration of substantial lateral propulsion capability [55]. Figure 2 presents the distribution of environmental parameters influencing flight performance, illustrating the effects of ambient temperature, pressure and density on balloon diameter.

Figure 2.

Distribution overview of environmental conditions affecting balloon diameter change.

Thermal Conditions and Effects

The flight profile of the prototype is conditioned by thermal conditions, where the main heat sources affecting flight performance include solar short-wave radiation and long-wave radiation (atmospheric infrared and surface thermal radiation). Moreover, since solar radiation plays a crucial role in the balloon energy balance [56], prototype launches conducted during the nighttime will result in a lower ascent rate. Therefore, within latter prototype development, the quantification of these thermal factors guided the selection of envelope materials with optimal absorptivity–reflectivity balance to ensure thermal stability and structural integrity during prolonged stratospheric exposure.

The short-wave component of solar radiation includes several radiation types and effects, including absorbed direct solar, ground-reflected, sky-scattered and Earth’s infrared radiation, each influencing the prototype’s thermal environment to varying degrees. The absorbed direct solar radiation (Rd) by the balloon envelope consists of energy absorbed by the outer (illuminated) and the inner surface of the balloon film, where this process can be expressed as:

where α indicates the film absorption factor of solar radiation, φ stands for the solar radiation constant number [W/m2], τR is the film transmissivity factor of solar radiation, rR marks the effective solar radiation reflectivity factor of the balloon film, while τ denotes the atmospheric transmissivity factor. It accounts for attenuation of solar radiation as it passes through the atmosphere, and it may be quantified as:

where δ represents the absolute atmospheric optical air mass, i.e., a measure of the optical path length of sunlight through the atmosphere, which varies with solar elevation angle and atmospheric pressure. Accordingly, due to Earth’s curvature and the variable optical thickness of the atmosphere, τ is defined differently depending on whether the solar elevation angle is lower (16) or greater than 5 degrees (17):

where h marks the solar elevation angle [°], P0 denotes local atmospheric pressure at operating altitude [Pa], while P0 represents standard atmospheric pressure [Pa]. Thereby, solar elevation angle is a site-specific factor which varies spatially (regionally) and temporally (season and time of day) as it depends on the position of the Sun relative to the prototype latitude. In general, it ranges from 0° (denoting nighttime) to 90° at noon, a moment of the greatest intensity of solar radiation during daytime. It can be determined as follows:

where ϕb marks geographic latitude of the airborne prototype [°], ξ refers to solar declination angle [°], while η denotes solar hour angle [°]. Thereby, the main cause of solar intensity variation stems from the solar geometry, particularly the variation of the solar declination angle, hour angle and true solar time. The solar declination angle represents the angular position of the Sun relative to the Earth’s equatorial plane. It varies throughout the year due to the Earth’s axial tilt and orbital motion around the Sun, and it may be quantified as follows:

where Ni stands for the day’s sequence in the year, while fluctuations of solar hour angle, which expresses the angular displacement of the Sun east or west of the local meridian due to the Earth’s rotation, may be approximated as:

where TH marks the true solar time [hours] which differs from mean solar time because of the elliptical shape of the Earth’s orbit, resulting in the distance and the relative position between the Sun and Earth varying with time, and the obliquity of the ecliptic, as Earth’s equator does not coincide with the plane of its orbit around the Sun. To account for these effects, true solar time is calculated as follows:

where stands for the regional standard time, which depends on which time zone the prototype is in; λb marks the geographic longitude of the airborne prototype [°]; refers to the regional standard time position’s longitude, which is equivalent to the longitude of the center line of the time zone; while ΔTH stands for the time difference [minutes], which is formulated as follows:

where W denotes Earth’s orbital time angle [radians], which reflects the position of the Earth in its orbit around the Sun and is defined as:

where ε stands for Earth’s orbit eccentricity. Ultimately, considering the reflective properties of the balloon film, the cumulative effect of multiple solar reflections can be expressed through the effective solar radiation reflectivity factor (rR) as follows:

Other solar short-wave radiation types considered within prototype conceptualization are ground-reflected radiation (Ra) (25) and sky-scattered radiation (Rs) (26), which were quantified as follows:

where eR indicates Earth’s surface reflectance factor, and ϑb denotes the angular coefficient from the balloon’s surface to Earth’s surface. Last but not least, the short-wave radiation type considered within the prototype conceptualization was Earth’s infrared radiation (REi), and it has been studied using the following equation:

where αIR denotes the balloon film absorption factor of infrared radiation, εE marks the ground’s average infrared emissivity factor, σ refers to the Stefan–Boltzmann constant, TE represents Earth’s surface temperature, τIR denotes the atmospheric transmissivity factor of infrared radiation, τR,IR is the balloon film transmissivity factor of infrared radiation, while rR,IR denotes the infrared radiation effective reflectivity factor of the balloon film.

In terms of long-wave radiation, within conceptualization, the effects of atmospheric infrared radiation and surface thermal radiation are important. The first one can be expressed as follows:

where εS denotes the atmospheric average infrared emissivity factor, while TS marks the sky equivalent temperature, which is quantified based on ambient temperature:

The latter, surface thermal radiation, which affects the film’s external (Rei) and internal surfaces (Rii), may be quantified using the following formula:

where ē represents the average infrared emissivity factor of the film material, while TF represents the temperature of the film material of the balloon.

Atmospheric Conditions and Effects

Atmospheric conditions and effects exert a significant influence on the overall thermal behavior of a high-altitude balloon throughout its ascent and float phases. For instance, variations in ambient temperature, air density, pressure, and wind velocity alter the dominant modes and efficiency of convective heat transfer as well as the relative contributions of radiative and conductive exchanges. Thereby, at lower altitudes, forced convection due to relative motion between the balloon and surrounding air dominates, while at higher altitudes, where air density decreases sharply, natural convection and radiative heat transfer become more prominent. These dependencies directly affect the heat exchange between the balloon film and the atmosphere, and between the film and the internal helium, thereby influencing internal gas temperature, buoyancy, and overall flight stability.

The convective heat transfer of a high-altitude balloon includes convective heat transfer between the balloon film and the external atmosphere (Rcx) and the convective heat transfer between the film and the internal helium (Rci). Thereby, in terms of atmospheric conditions and effects, there are two types of convective modes, forced convective heat transfer (Hf) and natural convective (Hl), as follows:

where Hx represents the external convective heat transfer coefficient, which is usually a coupled heat transfer process, so Hx may be broken down as follows:

where Hf represents the forced convection heat transfer coefficient, while Hl is the natural convection heat transfer coefficient. For the convection heat transfer between the film and the internal helium, its convective mode is natural convection, which may be defined as follows:

Atmospheric conditions also affect heat transfer on balloon film, whereby, within the process of prototype conceptualization, the temperature of the film has been assumed to be uniform and is formulated as follows:

where CF denotes the specific heat capacity of the film material. The assumption applied is thereby consistent with lumped-parameter thermal models, where rapid internal conduction justifies a uniform temperature approximation for conceptual analysis [57]. In addition, it has been assumed that the temperature and pressure of the internal helium are uniform. This is a common assumption in thermodynamic balloon models, where the lifting gas is treated as well-mixed and homogeneous [58]. According to the first law of thermodynamics, the temperature change rate of the internal helium is specified as follows:

where CV marks the specific heat capacity at a constant volume of helium, and γh is the specific heat ratio, which equals CP/CV, where CP denotes the specific heat capacity at a constant pressure of helium.

3.1.2. Prototype Payload Conceptualization

The methodological framework payload leverages the existing ADS-B systems widely deployed across the global commercial aviation fleet. As most modern aircraft are already equipped with ADS-B transponders, the integration of this system into the payload eliminates the need for any additional hardware investments or modifications by aircraft operators. Consequently, this approach ensures cost-efficiency, interoperability and immediate applicability within the current operational environment.

In the ADS-B framework, aircrafts continuously broadcast signals at a frequency of 1090 MHz using the extended squitter mode of the Mode-S transponder. These transmissions employ Pulse Position Modulation (PPM) at a rate of 1 Mbps. The term “extended” refers to the increased message capacity compared to the standard short squitter sequence used in the traditional Mode-S interrogation process via Secondary Surveillance Radar. Each ADS-B signal comprises 112 bits, of which 56 bits correspond to the basic ICAO message structure, while the remaining 56 bits follow the Downlink Format 17 (DF-17), a format reserved specifically for ADS-B data traffic. Each message is preceded by an 8 μs preamble, which indicates the start of the transmission and enables the receiver to unambiguously identify the positions of the high and low bits within the message [59]. The type of ADS-B data frame is determined by a type code that precedes the frame, with the contents of each type summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Overview of the ADS-B data frame content [60].

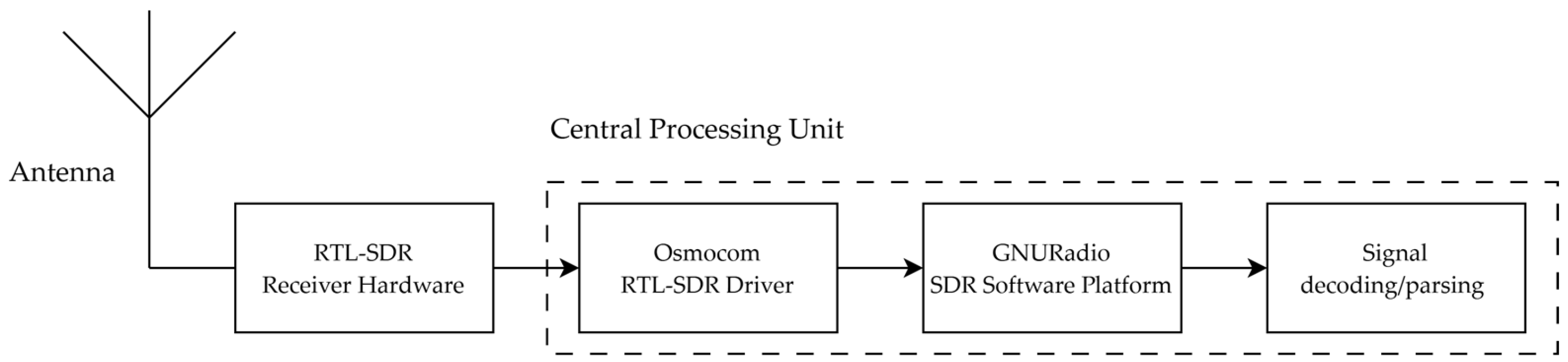

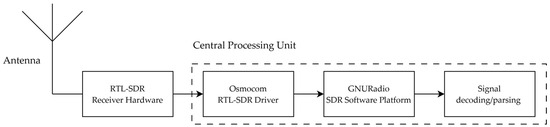

ADS-B signal and messages may be received by vast reception modules. Figure 3 illustrates the conceptual architecture of the ADS-B receiver acting as a core component of the prototype payload.

Figure 3.

Architecture of the ADS-B receiver.

The framework of the ADS-B signal reception module uses Software Defined Radio (SDR) technology to receive ADS-B signals to monitor aircraft in the area. After the signal is demodulated into a standard digital signal by the SDR hardware platform, the monitoring node computer uses the SDR platform and software code to correct and decode the digital signal and finally obtains the real-time flight parameters of the aircraft in the monitoring area. Thereby, for a distance between the transmitter and receiver (dtr) and wavelength (λw), the ratio of received power (PGR) to transmitted power (Pt) under ideal conditions (without additional losses) can be expressed by the Friis transmission equation as:

where Gt and GGR are the transmitter and receiver antenna gains, respectively. The corresponding theoretical path loss across the Free-Space Path Loss (FSPL), i.e., without any obstacles, reflections or absorption, can be quantified as follows:

where K marks a constant of 32.5 dB, which is derived from the Friis transmission equation and accounts for the speed of light and unit conversions when distance is expressed in kilometers, while f denotes a 1090 MHz frequency. In the context of ADS-B, this provides a baseline for estimating received signal levels from airborne payload.

Apart from the ADS-B signal reception module, the prototype payload consists of the several other components, including an onboard computer acting as a Central Processing Unit (CPU), which consists of a signal processing and encoding unit which performs demodulation, decoding and optional packet integrity validation; a micro-SD card for data storage; a telemetry and downlink communication unit; thermal regulation and environmental monitoring sensors; one omnidirectional antenna; a portable battery; and a set of wirings. All the components were housed together in a single payload for protection against the conditions and effects addressed in continuation.

Ultimately, the prototype payload was conceptualized to perform three essential functions, including reception of 1090 MHz ADS-B signals from aircraft within line-of-sight range, retransmission of the received signals to a dedicated prototype auxiliary support platform and storage of messages on onboard hardware. This multifunctional architecture enables the prototype to operate as a pseudo-satellite receiver, effectively bridging the line-of-sight limitations inherent in terrestrial surveillance networks.

Geometric and Physical Conditions and Effects

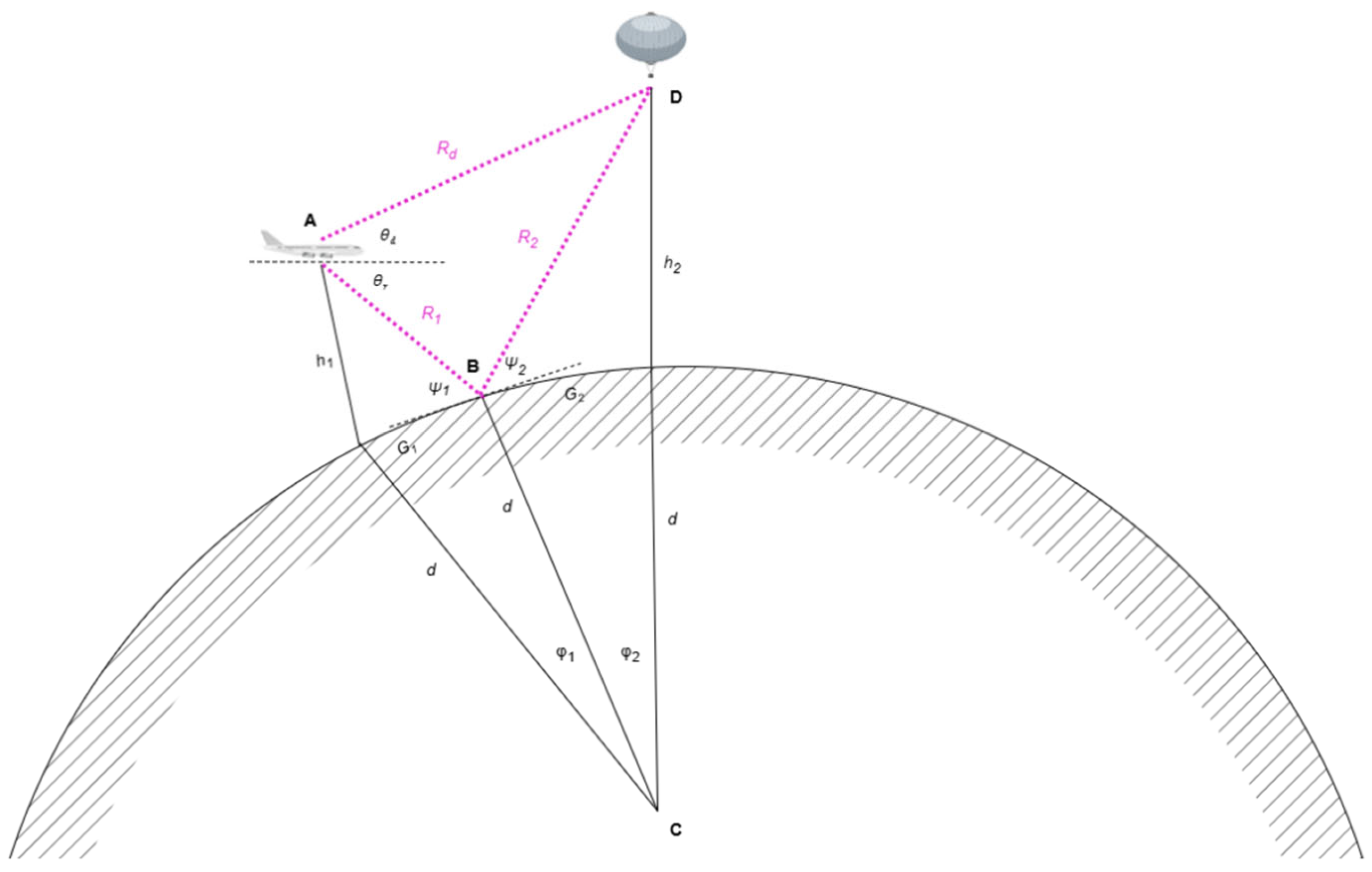

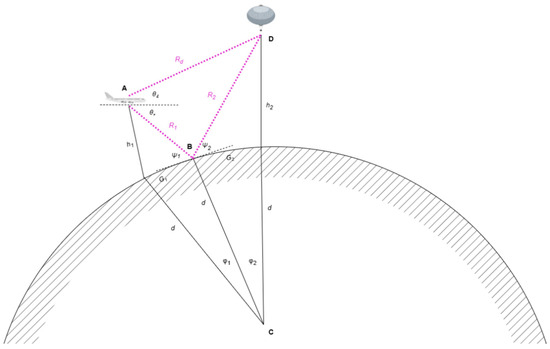

While ground-based ADS-B receivers operate under site-specific conditions, such as dense atmospheric influence or limited geometric visibility due to terrain masking and horizon constraints, these effects may not be attributed to space-based observations. In addition, there are other geometric and physical conditions and effects which may be attributed to ground-based observations, including distortion due to atmospheric moisture and tropospheric scintillation, while line-of-sight (LOS) limitations restrict the effective detection radius depending on receiver altitude and antenna gain. In contrast, space-based observations experience vastly different geometric and physical conditions. For instance, the signal arriving at high altitudes suffers from reduced power density and background noise from both cosmic and terrestrial sources, necessitating high-sensitivity front-end design. In that respect, Figure 4 illustrates the conceptualization of ADS-B signal transmission from aircraft to space-based receiver, i.e., the prototype and its payload with respect to the operating environment.

Figure 4.

Conceptualization of geometric and physical effects on ADS-B signal propagation.

Although ADS-B signals primarily propagate along a direct line-of-sight path, a secondary reflected component can occur when the transmitted signal interacts with the Earth’s surface or lower atmosphere before reaching an ADS-B receiver. Denoting these reflected paths is essential to evaluate multipath interference, signal fading and geometric delay effects in the ADS-B communication link. To account for Earth’s curvature and refractive bending, an effective Earth radius (d) is introduced as follows:

where Re represents Earth’s actual mean radius, while kr marks the radius coefficient that corrects for atmospheric refraction. Under standard atmospheric conditions, it equals 4/3, and under neutral conditions, it is approximately 1. It may be estimated as a function of elevation angle (θd), as follows:

The total reflected signal path is divided into two components, distance from the ADS-B transmitter onboard aircraft to the specular reflection point on the surface (G1) and distance from the reflection point to the payload of the prototype airborne (G2), as follows:

The reflected path geometry, considering the effective Earth radius, may be approximated as:

where h1 and h2 are the altitudes of the aircraft equipped with an ADS-B transmitter and a prototype equipped with an ADS-B receiver, while G denotes their horizontal ground separation. Solving this relationship yields the location of the specular reflection point on the Earth’s surface. The corresponding path lengths of the reflected signal, R1 and R2, can then be derived from the law of cosines to triangles ΔABC and ΔBCD as:

where φi represents the central angle subtended by each propagation segment, and it equals:

The depression angle of the reflected ray (θr), which determines the downward deviation from the local horizontal, can be quantified as follows:

while the grazing angle (Ψ), denoting the angle between the signal and the Earth’s surface at the reflection point, can be quantified as follows:

These relationships describe the geometry of multipath propagation, in which the ADS-B signal can reach the prototype payload both directly and via reflection from the ground or sea surface. Thereby, although the reflected component is generally weaker, it can introduce interference, leading to amplitude fading and phase distortion. Such effects are most significant when the phase difference between direct and reflected signals approaches 180°, producing destructive interference. From an operational perspective, these phenomena may affect the reliability and continuity of ADS-B signal reception under certain geometric and physical conditions, particularly at low elevation angles or over highly reflective surfaces. However, their operational significance cannot be conclusively assessed without experimental validation. The present analysis therefore highlights potential performance sensitivities rather than definitive limitations.

Environmental Conditions and Effects

Environmental conditions and effects considered within payload conceptualization refer to those effects which can affect ADS-B signal propagation. In that respect, the main contributors to ADS-B signal attenuation are raindrops, clouds, and fog, i.e., meteorological phenomena which generate oxygen and water vapor absorption, and sand and dust. Since ADS-B operates at a frequency of 1.9 GHz, i.e., since the size of the particle is significantly smaller than the radio wavelength, with an average diameter of 0.1–5 mm, Rayleigh scattering may be applied. According to ITU-R [61], it is possible to approximate the effects of scattering and absorption of rain using an empirical power–law relationship for rain-specific attenuation (ΓR), which contributes both effects as follows:

where k equals 0.000308 and q equals 0.8592 for vertical polarization at ≈1 GHz, while for a heavy rainfall rate, such as 100 mm/h, rain-specific attenuation equals 0.00161 dB/km. ADS-B signal attenuation due to clouds and fog, which generates signal attenuation lower than 0.01 dB/km at 1.09 GHz, may not be perceived as a significant contributor. This is similar for humidity, which at 1.09 GHz has attenuation of 0.001 dB/km, even at 100% relative humidity. This, in turn, may result in only small range fluctuations in the range from 1 to 2 km in ADS-B reception. Apart from these (direct), wet ground and sea surfaces (indirect) effects increase scattering, i.e., reflection, producing multipath delays that garble the pulse sequence in ADS-B messages. In terms of sand and dust effects, these conditions, although they have an effect on propagation, are negligible, as confirmed by ITU-R and atmospheric propagation models [62], as attenuation at the L-band is less than 0.05 dB/km even in dense storms with a 1000 µg/m3 dust density. Last but not least, environmental conditions and effects that also affect ADS-B signal propagation include space weather events. For instance, events like intense solar radio bursts at a radio frequency of approximately 1 GHz can disrupt radar systems, as was recorded on 4 November 2015 in multiple countries, including Belgium, Greenland, Norway and Sweden, leading to limited air traffic for a short period [63]. However, quantification of these effects was out of scope for the process of prototype payload conceptualization.

Thermal Conditions and Effects

Thermal conditions influence radio wave propagation primarily through temperature-dependent variations in air refractivity, equipment performance, and material responses within transmitting and receiving systems. Although ambient temperature does not directly attenuate the ADS-B signal at 1090 MHz, it indirectly modifies the propagation environment and the electrical characteristics of system components. Empirical observations from European and Middle Eastern ADS-B monitoring networks [64,65] show reception distances extending up to 600 km during strong inversion events compared to nominal ranges of 250–300 km. These anomalous propagation events correlate with high-pressure systems and elevated ground-level temperatures, typically occurring in late afternoon or early evening when the inversion gradient is most pronounced.

Thermal conditions also affect electronic and structural components. Receiver noise power increases linearly with temperature. However, a 10 °C rise increases the noise floor by ~0.04 dB, which is negligible for ADS-B signal propagation, following the total thermal noise power (kTB) theory [66]. In addition, thermal conditions generate cable and connector losses, where resistive losses in coaxial cables increase with ambient temperature, adding another ~0.1–0.2 dB over long feeder lines. Most importantly, low ambient temperature and low pressure strongly affect electronic components’ electrical and mechanical behavior. These thermal effects represent the primary risk to ADS-B performance on a HAPS. For instance, some oscillators stop oscillating transiently in extreme cold, while cable jackets and dielectric materials become brittle and can crack. Also, coaxial cable loss in metal conductors tends to decrease at cold temperatures, but mechanical failures and connector sealing represent the most serious risks. In addition, batteries may suffer capacity and discharge-rate degradation at low temperatures. Ultimately, differential thermal contraction between the materials used (metal and plastic) can lead to mechanical stress or micro-cracks. Thereby, to identify events as such, a thermocouple was also included within a payload to sense internal payload temperature during the flight missions. This information enables later technical analysis and potential fault diagnosis within the post-ops phase, allowing for benchmarking among internal payload temperature profiles against pre-flight defined ambient temperature profiles derived from LEO satellite observations.

Atmospheric Conditions and Effects

Although quantitatively minor, the influence of atmospheric conditions on the propagation of the 1090 MHz ADS-B signal must be determined to better understand its operational significance. Particularly, physical properties of the atmosphere affect propagation delay and signal attenuation. Therefore, within the payload conceptualization, it was necessary to formulate and quantify the effects of time delay, time dispersion, phase angle dispersion and natural atmosphere effects.

Charged particles in the atmosphere undoubtedly slow the signal propagation. However, with a frequency of 1090 MHz, the time delay may be perceived as relatively insignificant. Primary, as it is in the order of tens of nanoseconds, corresponding to a path error of only a few meters. Moreover, since the preamble of ADS-B messages contains synchronization bits, and ADS-B uses a narrow-band 1 MHz pulse-position modulation, the effect of dispersion is minimal [67]. Therefore, the overall effect on signal propagation is negligible, except in terms of diurnal variations in ADS-B signal behavior associated with solar activity. In this context, time delay (td) is referenced to propagation in a vacuum, as follows:

where denotes signal frequency [Hz], TEC marks total electron content along the transmission path [electrons·m−2], and where time delay dispersion (Δtd) corresponds to the rate of change in time delay with frequency, which can be expressed as follows:

Similar to time, phase angle dispersion also does not pose a problem since it may only introduce a small but measurable bias. Phase delay (pd) represents the phase change caused by the phase shift:

where c represents the speed of light in a vacuum [m/s], and where phase dispersion (Δpd) denotes the rate of change in the phase angle with frequency, which, with signal pulse length (sL), has the following relationship:

In terms of natural atmosphere effects, the effects of refraction and gaseous absorption have also been considered. The refraction represents the change in direction of an electromagnetic wave as it passes through media where the wave velocity varies. The ratio of the velocity in the medium compared to the velocity of an electromagnetic wave in s vacuum is referred to as the refractive index (nr). It determines the bending of the signal path and is defined as:

where TA denotes the absolute temperature [K], PA is the total atmospheric pressure [hPa], and εp marks the pressure of water vapor [hPa]. Consequently, although refraction exhibits negligible frequency dependence for the ADS-B signal, as L-band refractivity is primarily determined by atmospheric composition and geometry rather than frequency [68], it induces bending of low-elevation signals, effectively extending the line-of-sight range and slightly modifying the geometric propagation delay.

While other nonsymmetric molecules have neglected effect [69], gaseous absorption arises primarily from water vapor and oxygen molecules, which interact with the electromagnetic field. This absorption of electromagnetic radiation is quantified based on the specific attenuation coefficient (Γ) for a given frequency [GHz] along the path length, where the attenuation coefficient for oxygen (ΓO2) equals:

while the attenuation coefficient for water vapor (ΓH2O) equals:

where the ADS-B signal ΓO2 equals 5.169 × 10−3 [dB/km], while ΓH2O equals 6.462 × 10−3 [dB/km]. Accordingly, with a frequency of 1.09 GHz, both contributions are negligible, implying minimal energy loss over the distance between the aircraft and the ADS-B receiver on the prototype. Ultimately, the received signal power (PGR) at the airborne ADS-B receiver is determined by considering path losses and atmospheric absorption as:

where Pt denotes transmitter power [W], which is fixed by ADS-B standards; Gt and Gr are aircraft-based ADS-B Out transmitter and receiver-based ADS-B In gains, including line losses; λw represents the wavelength of the 1090 MHz transmission [m], which equals 0.275 m; Rd marks the direct path length from aircraft-based transmitter to ADS-B receiver on the prototype [m]; while La denotes the total atmospheric loss. Last but not least, it may be noted that the cumulative impact of the atmospheric conditions and effects on the signal strength, propagation and timing remains within acceptable ICAO limits for ADS-B surveillance. It was necessary to quantify these factors as part of the prototype payload conceptualization, particularly to better understand the overall performance of the payload onboard.

3.2. Development Phase Review

From the conceptual aspect, the prototype consists of three principal components, including the platform, the payload and the prototype auxiliary support unit, the latter being essential for enabling Beyond Visual Line of Sight (BVLOS) operations and operational control in general as well as for performance monitoring. The prototype development, reflecting its platform and payload configuration, was designed with minimal ground-based requirements. Owing to its buoyant configuration, it does not necessitate conventional runway infrastructure for take-off or landing, where launch and recovery sites are only desirable to be obstacle-free, with no trees or power lines in the vicinity. Upon its validation, the developed prototype is foreseen to operate within a constellation of multiple equal platforms, with the formation and density of the constellation determined by the spatial coverage required for a specific mission. Operational control and performance monitoring will be managed by the platform operator, remotely and on-site, depending on mission duration and operational complexity.

The prototype platform was developed so that it consists of five principal components, including a high-altitude balloon, a recovery parachute, a radiosonde, a set of ropes and a payload. In terms of mass distribution, the platform accounts for 36.01% of the total prototype mass, while the remaining share goes to the payload. The high-altitude balloon HY-350 applied is made of natural latex, and it was produced by Hwoyee (China). It has a neck length of 120 mm, a neck diameter of 440 mm, a bursting diameter of more than 4800 mm, and average bursting altitude of approximately 85,300 feet (26 km). A recovery parachute, which automatically deploys after balloon burst, was included to ensure safe and controlled descent of the payload. It was made of plastic with a top string of 1200 mm, canopy diameter of 1070 mm and spreader hoop diameter of 230 mm. A radiosonde RS41-SGE, produced by Vaisala (Finland), was added for atmospheric measurement, and it acts as a GPS receiver for altitude profiling by transmitting data via telemetry. It has a measurement range from the surface of up to 40 km and a maximum transmitting range up to 350 km, powered by 2 AA-size Lithium cells, enabling an operating time of approximately 240 min. Ultimately, the platform components and payload are attached using high-tensile nylon ropes of 1150 kg/m3 density that are 1.00 mm in diameter. Table 2 presents the technical specifications of the prototype elements per component.

Table 2.

Overview of the technical specifications of the prototype elements per component.

These technical specifications condition flight performance, which can be used to address flight motion and dynamics, which can be expressed as follows:

where the three forces that act upon the prototype include weight (FW), buoyancy (FY) and drag (FD). The overall weight may be quantified as follows:

where ms marks the total prototype mass, including balloon, payload, ballast and lift gas, while g is the gravitational acceleration, which is considered to be a vertical vector that points from the balloon’s center of mass to the center of the Earth. The buoyancy (FY) and drag (FD) can be formulated as follows:

where ż denotes the balloon’s vertical velocity, vwz marks the vertical geometric component of the wind velocity, while Cd represents the drag coefficient, which can be quantified as follows:

where Re denotes the Reynolds number, which can be formulated as follows:

where rb denotes the radius of the balloon, while μair, which corresponds to the air viscosity (64) and the air conductivity (65), can be quantified using Sutherland’s Law as follows:

Thereby, all of these forces are applicable along the altitude axis. In terms of horizontal velocity, it is equal to that of the wind itself, and therefore, transversal drag is not considered. Last but not least, considering the applied conceptual framework and prototype development, prior to reaching the altitude of 80,000 feet AMSL, with the all the mass except the mass of the air ballon, which totals 1080.00 g, and considering other platform and payload specification, the prototype may be airborne up to approximately 89 min, i.e., up to 1 h and 55 min with assumption of an average vertical climb rate of the balloon of 4.56 m/s. To achieve this ascent rate and burst altitude, the initial volume of helium needed at launch equals 1989 liters.

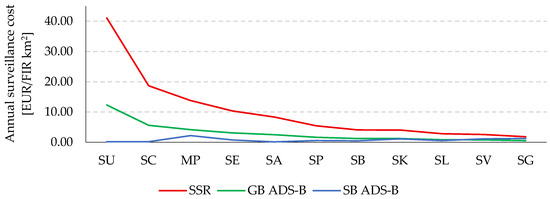

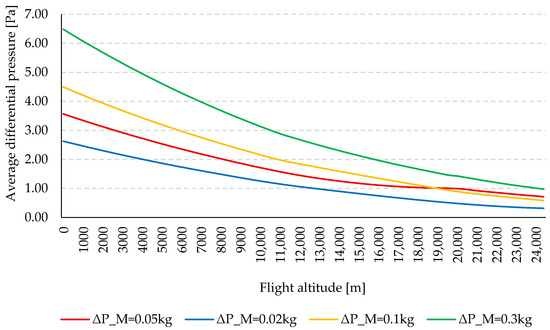

3.2.1. Platform Specifications Review

The platform is conceptually designed to operate without consuming power available on board for climb, maneuvering or descent operations. Given that the ATM system operates continuously (H24), the prototype was developed to reflect this requirement by relying solely on stored on-board energy. The power supply system is therefore time-conditioned. This design ensures operational resilience and consistency, as the platform maintains stable performance characteristics regardless of whether the prototype operates during daytime or nighttime conditions. This also allows for a better understanding of how identical components and designs operate differently under altitude change, daytime and nighttime conditions, various environments, and thermal and atmospheric conditions. Figure 5 illustrates the distribution of the average differential pressure as a function of variations in standard atmospheric pressure, highlighting the influence of different helium masses on the observed changes in average differential pressure. However, unlike some existing HAPS solutions, the current prototype does not incorporate photovoltaic cells for in-flight battery recharging. As a result, this represents a limitation in terms of energy sustainability. Following initial prototype validation, this segment will become the focus of future R&D efforts, as it is a key milestone in transforming the platform into a self-sustaining solution.

Figure 5.

Distribution of average differential pressure under standard atmospheric conditions.

3.2.2. Payload Specifications Review

The literature review indicates that the operating environment is highly demanding in terms of payload performance. Mainly, the material and products are not generally tested for extreme temperatures. This primarily refers to electronic components, whose performance is greatly affected by temperatures. In general, the conductivity of metals at low temperatures decreases significantly, as the electrical resistance rises with air temperature. For instance, the lowest possible temperature for the power unit within the payload to operate while discharged is −20 °C and 0 °C when charging. As a result, thermal stress on electronic components occurs and can lead to failure of the components.

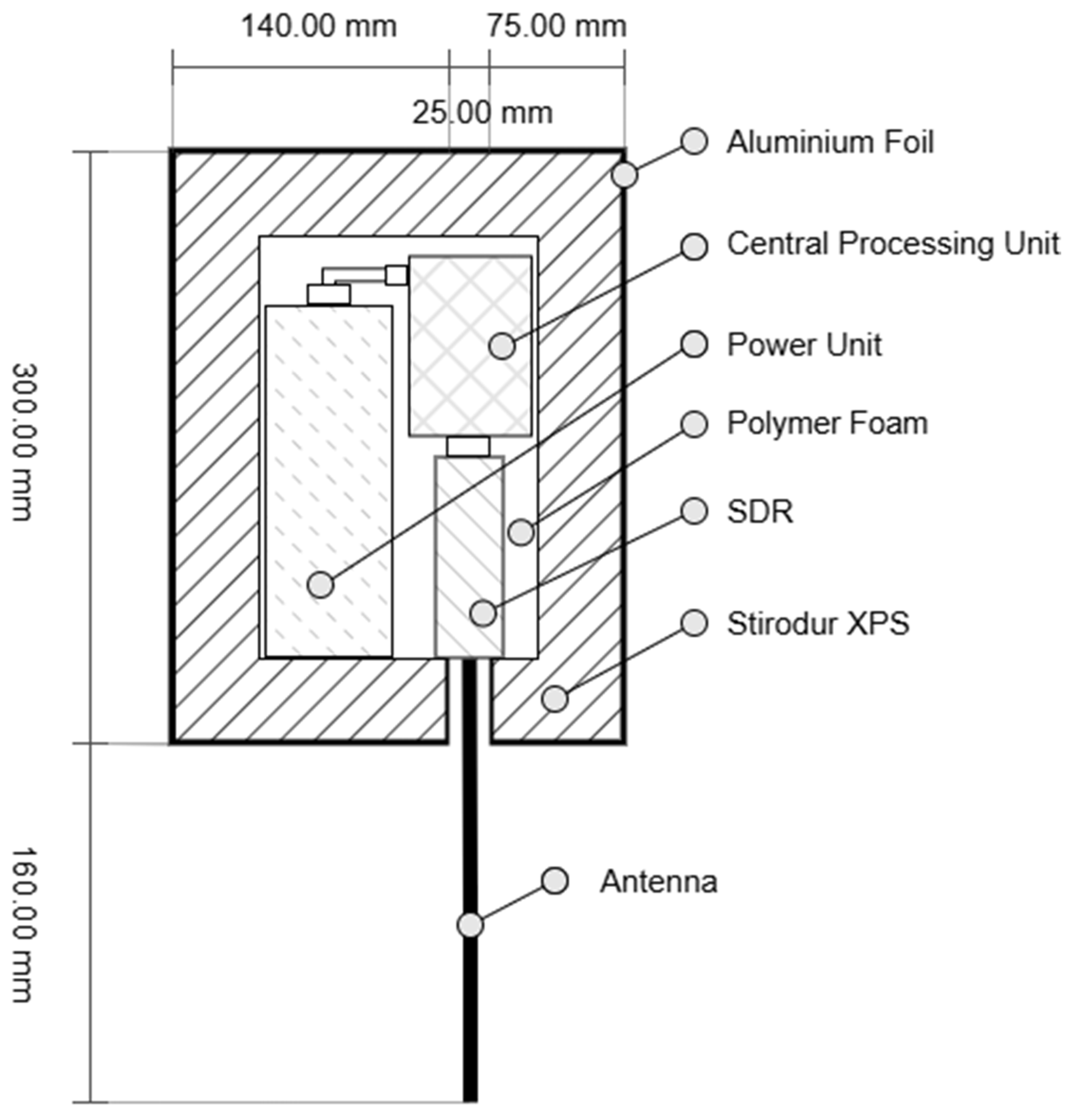

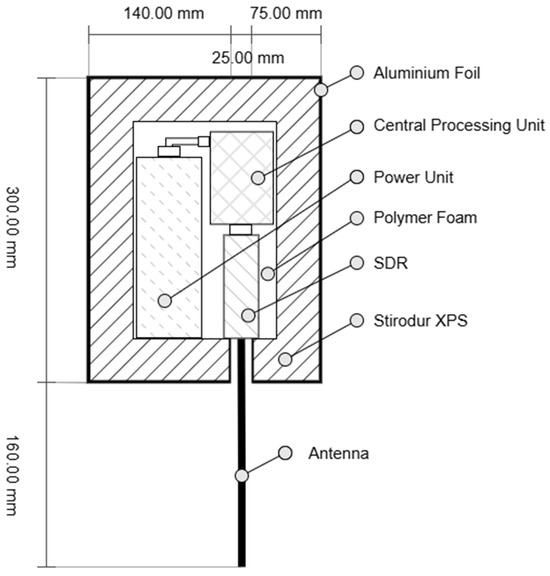

Considering the above, the prototype payload with a dimension of 240 × 460 × 180 mm is developed as a lightweight, low-power, thermally stable and electromagnetically optimized component, capable of persistent ADS-B data collection and relay operations within a harsh operational environment. Limited payload mass does not provide room for extra redundancy. The total payload mass, which denotes the mass of everything suspended below the balloon, equals 915.00 g. The payload is coated by Styrofoam extruded polystyrene with a density of 35 kg/m3 as it has good insulating properties, solid strength and impact resistance due to its closed cell structure that also prevents the passage of air and moisture. Also, from the internal side, it has been faced by polymer foam with a density of 30 kg/m3, while from the outside, payload was lined with 0.04-millimeter-thick aluminum foil of 2700 kg/m3 density and sealed with aluminum tape. It was designed to insulate the payload components from potential stratospheric temperatures of −56 °C, to protect the internal components from the force of impact during landing, and to be buoyant and leak-resistant in case of a water landing. The payload also has markings identifying the payload and its launching authority. Eventually, this contributes to the recovery of the payload by third parties in the event that the retrieval team is unable to locate it. Figure 6 shows a schematic of the prototype payload housing. It also illustrates internal component placement and materials used for thermal and structural protection.

Figure 6.

Schematic of the prototype payload housing and internal component layout.

3.2.3. Prototype Auxiliary Support Platform

To ensure the successful completion of prototype missions, it is essential to predict the flight trajectory in advance. This prevents the prototype from drifting outside the designated airspace due to wind effects [70,71]. Primarily, as the developed prototype does not contain any propulsion mechanisms or actuators, it cannot be directly controlled during flight. Consequently, its motion is entirely governed by physical, environmental, thermal, and atmospheric factors. Therefore, to maintain operational safety and ensure that each mission remains within the planned limits, a decision-support system based on initial trajectory prediction is required to assess mission feasibility before launch.

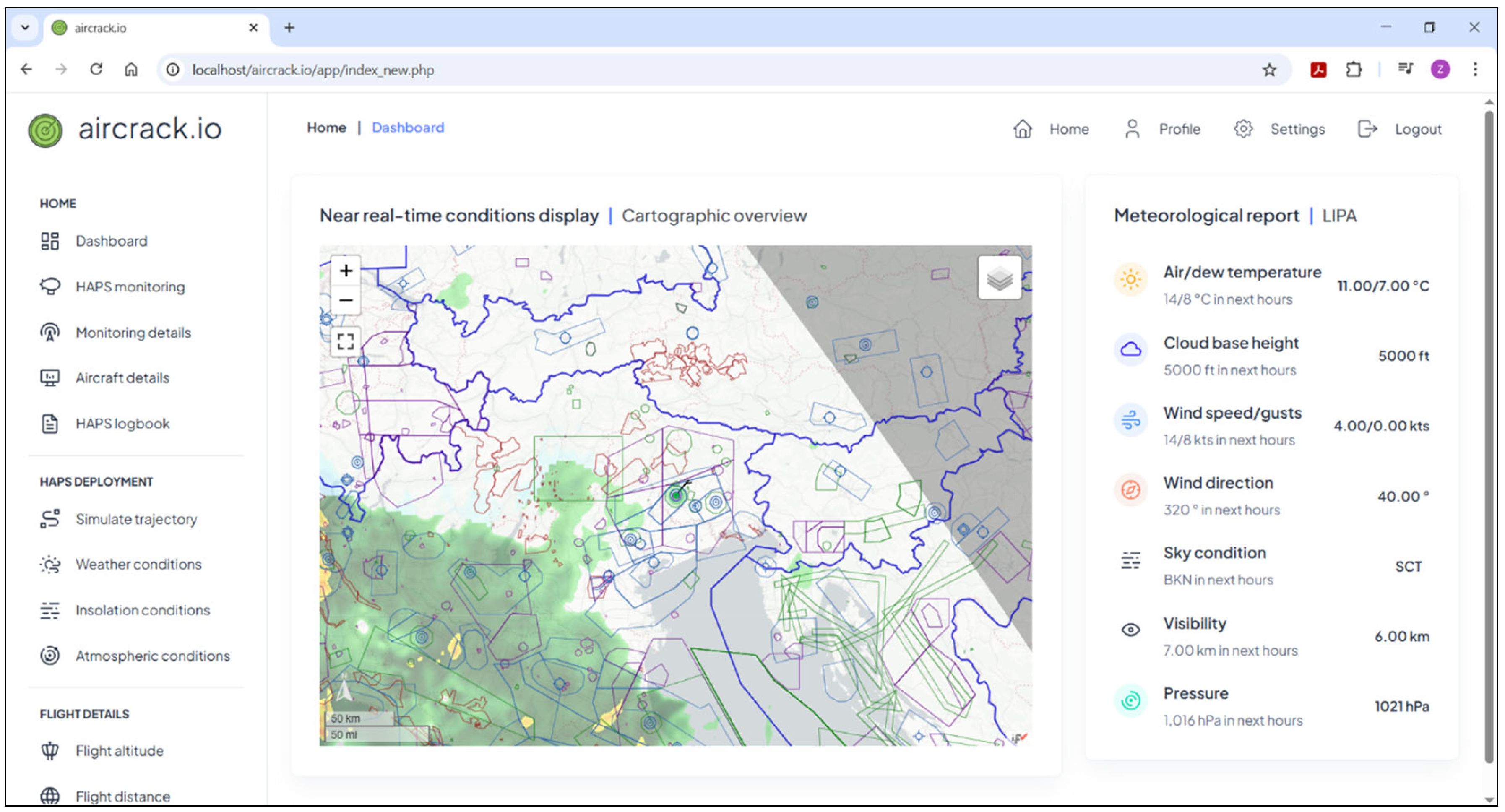

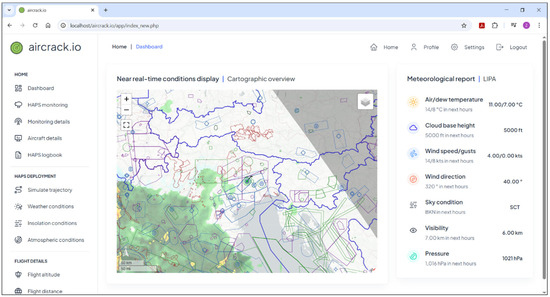

To support HAPS operations, a web-based application named aircrack.io has been developed as its auxiliary support platform for mission management. The application integrates a comprehensive set of performance indicators that describe the various conditions and effects influencing both the platform and its payload. The application incorporates two primary categories of data—static data, including polygonal definitions of airspace boundaries and designated operational zones, and dynamic data, encompassing meteorological and atmospheric information such as SIGMET reports—as well as real-time indicators of environmental, thermal and physical conditions. In addition to these, aircrack.io provides data on ADS-B signal reception performance, offering insights into surveillance quality metrics such as received signal power, coverage range, noise levels and message rates. The application is designed to support BVLOS operations and enables both tactical monitoring during flight and strategic post-mission analysis. Within the platform’s Graphical User Interface (GUI), the estimated HAPS flight profile is displayed on an interactive map. To initiate a simulation or mission assessment, the user inputs only essential information, including the planned timestamp (date and time of the intended flight) and the launch site coordinates (latitude and longitude). The altitude of the launch site is automatically derived through an embedded algorithm, while the technical specifications of the HAPS and its payload are treated as fixed parameters that remain constant regardless of launch location. Figure 7 shows the main dashboard of the aircrack.io platform, illustrating the integration of HAPS deployment condition, flight and other details within a unified web-based operational interface.

Figure 7.

Main dashboard of the web-based HAPS operational support platform aircrack.io.

4. Known Limitations and Issues

The stratosphere represents a relatively new operating environment for the aviation industry. Primarily, operational conditions encountered by HAPS differ significantly from those experienced by conventional aircraft. These differences introduce several limitations, including operational and technical limitations, both of which are a result of environmental and atmospheric conditions and effects. Wind speed and direction, solar radiation and temperature gradients may affect the prototype’s performance. Operations during winter or in higher-latitude regions may experience greater variability (seasonal changes), while equatorial or summer missions generally provide more optimal operational conditions. Consequently, the HAPS prototype logs altitude data with spatial and temporal timestamps, enabling post-mission evaluation of performance relative to operational conditions.

In terms of prototype limitations, it should be noted that the prototype’s relatively large size increases aerodynamic drag, particularly during the climb phase, limiting its maneuverability. As a result, precise knowledge of current and forecasted weather conditions at operational altitude is critical for safe deployment and trajectory prediction. In that respect, structural components, such as gas envelopes, foils, films, etc., could not be fully tested under laboratory conditions at representative scales or environmental loads. Degradation due to ambient temperature, solar radiation, pressure and other parameter variations remains a potential source of operational uncertainty.

Surveillance data latency is another known limitation. External telecommunications networks delivering ADS-B data can further increase latency (the reception time). For instance, the AIREON system is designed with a 1.5 s processing time, with an additional 0.5 s possible at client facilities. Although this meets the EUROCONTROL SPEC-0147 requirement of a 2 s maximum [72], monitoring of network performance is critical to ensure real-time operational reliability. Also, HAPS operations involve large numbers of signals, especially when using space-based receivers with satellite constellations. Signal overlap can occur, leading to packet collisions, errors or conflicts with intact packets [73]. Techniques such as signal separation algorithms [73] can mitigate these issues, but they remain a source of operational uncertainty.

This research represents a continuation of previous R&D efforts and builds upon known outcomes. The paper presents insights on HAPS conceptualization, with a clear focus on the interpretation of the coexistence of integrated hardware and software components, i.e., conceptual and development frameworks. However, it should be noted that not all hardware components of the prototype have been developed specifically for this study. Some of the components may be categorized as grey boxes, as their technical functionality is discrete information. As such, full documentation or functional testing of these elements was outside the scope of this research.

At this R&D phase, no real-world flight tests have been conducted. The developed prototype, comprising integrated components validated in a laboratory environment, is currently assessed at Solution Readiness Level (SRL) 4. Future work aims to advance the prototype toward SRL 6 through preliminary flight testing and operationally relevant demonstrations, rather than immediate large-scale deployment at SRL 9. Consequently, the integration of the proposed HAPS-based surveillance concept into existing ATM systems has not yet been demonstrated or validated through system-level simulations or operational trials.

Last but not least, when it comes to HAPS utilization and operationalization, the literature review provides no publicly available scientific evidence detailing the performance of HAPS platforms. One of the reasons is that their performance varies with differences in their configuration. Although several Key Performance Indicators (KPIs), such as deployment time, vertical and horizontal velocity, and signal reception power, are identified as relevant for assessing operational suitability and ATM integration, these KPIs are not quantitatively evaluated or discussed in detail within the present study. In that respect, and considering the developed prototype, future research should address the formal definition, quantification and validation of such KPIs, as well as their role in ATM interoperability, surveillance performance and system-level impact assessment, addressing also how seasonal variations affect the prototype and its platform performance. Additionally, future studies will include preliminary ADS-B performance assessments during flight testing to validate the surveillance capabilities of the system.

5. Conclusions

The developed HAPS prototype serves as a proof of concept for near-space ADS-B surveillance enhancement, establishing a scalable foundation for integration into future multi-platform HAPS constellations envisioned within next-generation ATM systems. Despite numerous challenges associated with HAPS operations, particularly those arising from the unique stratospheric environment, the potential applications remain highly promising. Beyond their commercial value, HAPS platforms offer significant opportunities for institutional stakeholders and the broader academic community.

The primary outcome of this R&D effort is the conceptualization and development of a HAPS prototype capable of maintaining stable flight within near-space altitudes, thereby enabling extended surveillance missions. In the long term, the developed HAPS prototype may serve as a complementary surveillance and communication layer to the existing ATM infrastructure. Its capability for ad-hoc deployment provides valuable redundancy and resilience, particularly during disaster response operations, such as floods, earthquakes or conflicts, where conventional radar systems or communication networks may be compromised.

To sum up, achieving industry-wide concept validation, alongside continuous prototype testing, represents the essential step towards ensuring the safe, efficient and reliable integration of the developed HAPS prototype into the future aviation ecosystem. Hence, within forthcoming R&D activities, emphasis will be placed on the transition from theoretical to experimental and applied research to validate the prototype’s functionality and its performance under real-world operational conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.R.; methodology, Z.R.; software, Z.R.; validation, T.B. and Z.R.; formal analysis, Z.R.; resources, S.S.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.R.; writing—review and editing, T.B.; visualization, Z.R.; supervision, S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ADS-B | Automatic Dependent Surveillance–Broadcast |

| AMSL | Above Mean Sea Level |

| APAC | Asia/Pacific |

| ATC | Air Traffic Control |

| ATM | Air Traffic Management |

| BVLOS | Beyond Visual Line of Sight |

| CNS | Communication, Navigation and Surveillance |

| CONOPS | Concepts of Operations |

| DF-17 | Downlink Format 17 |

| EASA | European Union Aviation Safety Agency |

| ECHO | European Concept for Higher Altitude Operations |

| FAA | Federal Aviation Administration |

| FIR | Flight Information Region |

| FL | Flight Level |

| GB ADS-B | Ground-Based Automatic Dependent Surveillance–Broadcast |

| GEO | Geostationary Earth Orbit |

| GUI | Graphical User Interface |

| HAO | Higher Airspace Operations |

| HAPS | High-Altitude Pseudo-Satellite |

| ICAO | International Civil Aviation Organization |

| KPI | Key Performance Indicator |

| LEO | Low Earth Orbit |

| LOS | Line-Of-Sight |

| NASA | National Aeronautics and Space Administration |

| NM | Nautical Mile |

| PPM | Pulse Position Modulation |

| PSR | Primary Surveillance Radar |

| R&D | Research and Development |

| SAM | South American Region |

| SB ADS-B | Space-Based Automatic Dependent Surveillance–Broadcast |

| SDR | Software Defined Radio |

| SIGMET | Significant Meteorological Information |

| SRL | Solution Readiness Level |

| SSR | Secondary Surveillance Radar |

| USAF | United States Air Force |

References

- Flight Safety Foundation. Benefit Analysis of Space-Based ADS-B; Flight Safety Foundation: Alexandria, VA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, B.S.; Schuster, W.; Ochieng, W.Y. Evaluation of the capability of automatic dependent surveillance broadcast to meet the requirements of future airborne surveillance applications. J. Navig. 2017, 70, 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blomenhofer, H.; Pawlitzki, A.; Rosenthal, P.; Escudero, L. Space-Based Automatic Dependent Surveillance Broadcast (ADS-B) Payload for In-Orbit Demonstration. In Proceedings of the 6th Advanced Satellite Multimedia Systems Conference and 12th Signal Processing for Space Communications Workshop, Vigo, Spain, 5–7 September 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen, B.G.; Jensen, M.; Birklykke, A.; Koch, P.; Christiansen, J.; Laursen, K.; Alminde, L.; Le Moullec, Y. ADS-B in Space: Decoder Implementation and First Results from the GATOSS Mission. In Proceedings of the 14th Biennial Baltic Electronic Conference, Tallinn, Estonia, 6–8 October 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, K. Space-Based ADS-B: Performance, Architecture and Market. In Proceedings of the 2019 Integrated Communications, Navigation and Surveillance Conference, Herndon, VA, USA, 9–11 April 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tozer, T.C.; Grace, D. High-altitude platforms for wireless communications. Electron. Commun. Eng. J. 2001, 13, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tozer, T.C. Broadband communications from a high-altitude platform: The European HeliNet programme. Electron. Commun. Eng. J. 2001, 13, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dovis, F.; Lo Presti, L.; Magli, E.; Mulassano, P.; Olmo, G. Stratospheric platforms: A novel technological support for Earth observation and remote sensing applications. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Remote Sensing, International Society for Optics and Photonics, Toulouse, France, 17–21 September 2001; pp. 402–411. [Google Scholar]

- Everaerts, J.; Biesemans, J.; Claessens, M.; Lewyckyj, N. A stratospheric platform for remote sensing and photogrammetry. Orbit 2005, 450, 681–709. [Google Scholar]

- Knapek, M.; Horwath, J.; Moll, F.; Epple, B.; Courville, N.; Bischl, H.; Giggenbach, D. Optical high-capacity satellite downlinks via high-altitude platform relays. In Optical Engineering + Applications, International Society for Optics and Photonics; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2007; pp. 107–118. [Google Scholar]

- Civil Air Navigation Services Organisation. ANSP Guidelines for Implementing ATS Surveillance Services Using Space-Based ADS-B; Civil Air Navigation Services Organisation: Soesterberg, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bagarić, T.; Rezo, Z.; Radišić, T.; Steiner, S. Countering ADS-B Signal Spoofing by Time Difference of Arrival Multilateration Method. Transp. Res. Procedia 2025, 91, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbraak, T.; Ellerbroek, J.; Sun, J.; Hoekstra, J. Large-Scale ADS-B Data and Signal Quality Analysis. In Proceedings of the 12th USA/Europe Air Traffic Management Research and Development Seminar; FAA/EUROCONTROL: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Pryt, R.; Vincent, R. A simulation of the reception of automatic dependent surveillance—Broadcast (ADS-B) signals in low Earth orbit. Int. J. Navig. Obs. 2015, 2015, 567604. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S.; Chen, W.; Chao, C. The STU-2 CubeSat mission and in-orbit test results. In Proceedings of the 30th Annual AIAA/USU Conference on Small Satellites, Logan, UT, USA, 6–11 August 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Yu, S.; Chen, Q.; Zhao, Y. Data reception analysis of ADS-B on board the Tiantuo-3 satellite. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1438, 012030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, R.; Freitag, K. The CanX-7 ADS-B mission: Signal propagation assessment. Positioning 2019, 10, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nies, G.; Stenger, M.; Krčál, J.; Hermanns, H.; Bisgaard, M.; Gerhardt, D.; Haverkort, B.; Jongerden, M.; Larsen, K.G.; Wognsen, E.R. Mastering operational limitations of LEO satellites—The GOMX-3 approach. Acta Astronaut. 2018, 151, 726–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, K.; Bredemeyer, J.; Delovski, T. ADS-B over satellite: Global air traffic surveillance from space. In Proceedings of the 2014 Tyrrhenian International Workshop on Digital Communications—Enhanced Surveillance of Aircraft and Vehicles, Rome, Italy, 15–16 September 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Jaya, T.; Hartono, L.; Fatonah, F.; Mukti, I.; Aritama, D.P. Feasibility Study Aireon Space Based ADS-B in Indonesia. J. Ilm. Wahana Pendidik. 2024, 10, 766–775. [Google Scholar]

- International Civil Aviation Organization. Report of the Thirteenth Meeting of the Common Aeronautical Virtual Private Network Operations Group (CRV OG/13), 5–8 March 2025, Wellington, New Zealand; ICAO Asia and Pacific Office: Bangkok, Thailand, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- International Civil Aviation Organization. Asia/Pacific Seamless ANS Plan Version 4.0; ICAO Asia and Pacific Office: Bangkok, Thailand, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO). Study on the Convenience and Feasibility of Space-Based ADS-B for Regional Implementation; ICAO: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Di Vito, P.; Fischer, D.; Rinaldo, R. HAPs Operations and Service Provision in Critical Scenarios. In Proceedings of the SpaceOps Conferences, Marseille, France, 28 May–1 June 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budroweit, J.; Eichstaedt, F.; Delovski, T. Aircraft Surveillance From Space: The Future of Air Traffic Control?: Space-Based ADS-B, Status, Challenges and Opportunities. IEEE Microw. Mag. 2024, 25, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabulut Kurt, G.; Al-Hourani, A.; Yanikomeroglu, H.; Alouini, M.-S.; Zhang, J.; Dang, S.; Liu, Y.; Yuan, J. A Vision and Framework for the High Altitude Platform Station (HAPS) Networks of the Future. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2021, 23, 729–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Telecommunication Union. Preferred Characteristics of Systems in the Fixed Service Using High Altitude Platforms Operating in the Bands 47.2–47.5 GHz and 47.9–48.2 GHz; Recommendation ITU-R F.1500; ITU: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, M.S.; Kurt, G.K.; Yanikomeroglu, H.; Zhu, P.; Đào, N.D. High Altitude Platform Station Based Super Macro Base Station Constellations. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2021, 59, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, C.T.U.S. Tracking High-Altitude Surveillance Balloon. U.S. Department of War. Available online: https://www.war.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/3287177/us-tracking-high-altitude-surveillance-balloon/ (accessed on 8 January 2026).

- Horváth, A. Possible Applications of High Altitude Platform Systems for the Security of South America and South Europe. Acad. Appl. Res. Mil. Public Manag. Sci. 2021, 20, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuse, Y.; Tran, G.K. Localization of Radio Sources Using High Altitude Platform Station (HAPS). Sensors 2025, 25, 1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Federal Aviation Administration. Fact Sheet—ETM Concept of Operations; FAA: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.faa.gov/sites/faa.gov/files/FactSheet-ETM-Concept-of-Operations.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Yoo, H.-S.; Li, J.; Homola, J.; Jung, J. Cooperative Upper Class E Airspace: Concept of Operations and Simulation Development for Operational Feasibility Assessment. In Proceedings of the AIAA AVIATION Forum, Virtual Event, 2–6 August 2021; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics: Reston, VA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- European Union Aviation Safety Agency. Proposal for Roadmap on Higher Airspace Operations: Exploring the Challenges of Future Operations in the Airspace Above FL550; EASA: Cologne, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- European Union Aviation Safety Agency. Roadmap on Higher Airspace Operations (HAO) Proposed by EASA. 2023. Available online: https://www.easa.europa.eu/en/newsroom-and-events/news/roadmap-higher-airspace-operations-hao-proposed-easa (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- European Union Aviation Safety Agency. Update of Higher Airspace Demand Analysis and Market Developments—Final Report; EASA Research Project on Higher Airspace Operations (HAO), Sub-task 2.2 Final Report; EASA: Cologne, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- European Union Aviation Safety Agency. Regulatory Framework for Higher Airspace Operations (HAO)—Research Project Documentation; EASA: Cologne, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Horváth, A. New Types of Higher Airspace Flight Operations and Their Legal Challenges. Eur. Integr. Stud. 2024, 20, 87–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SESAR Joint Undertaking. European Concept for Higher Altitude Operations; SESAR 3 JU/EUROCONTROL: Brussels, Belgium, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- SESAR Joint Undertaking. European Concept of Operations for Higher Airspace Operations (ConOps); ECHO Project Deliverable D4.3; SESAR 3 JU/EUROCONTROL: Brussels, Belgium, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Vilaplana, M. HAPS Operations. In Proceedings of the ECHO Workshop 3, Brussels, Belgium, 6 December 2022. [Google Scholar]