Abstract

The 2-segment even-split layout in various stator asymmetry layouts effectively mitigates the amplitude of the high-engine-order (HEO) forced response induced by the vane passing frequency (VPF). However, it may increase the level of the low-engine-order (LEO) forced response. A 2-segment non-even-split layout has been proposed in a previous study to reduce the amplitude of LEO aerodynamic excitation arising from the 2-segment even-split layout. This paper presents a full-annular unsteady forced response analysis of a single-stage turbine conducted using an in-house code to compare the aerodynamic excitations on the rotor blades across different 2-segment non-even-split layouts. The analysis reveals that an inappropriate circumferential angle assignment of the 2-segment non-even-split layout is ineffective in simultaneously suppressing the high amplitudes of both HEO and LEO aerodynamic excitations. Determining the optimal layout by calculating various circumferential angle assignments individually incurs significantly high computational costs. To address this issue, a fast and accurate simplified model for stator asymmetry is proposed in this study. The accuracy of the simplified model is validated by comparing its results with the suppression effects of aerodynamic excitation obtained from numerical simulations. The optimal stator asymmetry layout for a single-stage turbine is identified through this simplified model. The results indicate that the selected optimal layout can reduce VPF aerodynamic excitation of the symmetric layout by 45.14% and the 3-engine-order (3EO) aerodynamic excitation introduced by the 2-segment even-split layout by 43.56%, while the negative impact on the aerodynamic performance is significantly smaller than that of the 2-segment even-split layout. This study provides a robust theoretical foundation for enhancing the application of stator asymmetry in engineering, which demonstrates its practical engineering value.

1. Introduction

Forced response on turbomachinery blades may cause blade high-cycle fatigue (HCF) failure, which severely endangers the operational safety of the aero-engine [1,2,3,4]. Stator asymmetry has been demonstrated as an effective engineering strategy to mitigate the amplitude of the high-engine-order (HEO) blade forced response induced by the vane passing frequency (VPF) [5,6,7]. Previous studies have explored various stator asymmetry layouts, The N-segment even-split layout is more commonly employed in engineering applications. In this layout, the full-annulus stator can be divided into N segments; each segment occupies an equal circumferential angle, but the stator pitch counts are different within each segment [8,9]. Kaneko [10] examined the N-segment even-split layout for N values of 2 and 4, and concluded that the 4-segment layout effectively reduces vibration stresses on rotor blades, but recommends the 2-segment layout for cost-effectiveness. Meng [11] noted that increasing segment numbers may introduce additional frequency components. Niu [12] further corroborated that the 2-segment even-split layout optimally reduces vibration stresses on rotor blades across N values of 2, 4, and 6.

However, some studies have found that the 2-segment even-split layout introduces multiple LEO excitation components with high amplitudes, and its induced LEO blade forced response is more than 10 times the HEO forced response in terms of maximum vibration amplitude. The authors identified, for the first time in a previous study [13], that the differences in potential field between two segments are the main source of LEO aerodynamic excitation. A 2-segment non-even-split layout proposed in the previous study can effectively control the difference in the potential field. In this layout, the full-annulus stator can be divided into 2 segments; each segment occupies unequal circumferential angles, but the stator pitch counts within each segment are equal [5,14]. In a 2-segment non-even-split layout, the difference in potential field is controlled by adjusting the circumferential angle occupied by each segment, thus effectively reducing the LEO aerodynamic excitation introduced by the 2-segment even-split layout. The effect of choosing different circumferential angles on the suppression effect of LEO aerodynamic excitation is still unknown. The question that arises is whether there exists an optimal circumferential angle distribution for the two segments that best suppresses LEO forced response on the rotor blade. Identifying the optimal 2-segment non-even-split layout may require extensive computational comparisons with the circumferential angle as the independent variable, which incurs high computational costs. Thus, developing a fast and accurate stator asymmetry design model is critical.

Predicting aerodynamic excitation amplitudes on rotor blades is essential for developing a stator asymmetry design model. Kemp [5] first proposed a predictive model for aerodynamic excitation on the rotor blade due to stator asymmetry. Subsequent modifications by Kurz [15], Sun [14], Leng [16], and Zhang [17] achieved good validation accuracy against numerical and experimental results. However, most of the research only focuses on predicting HEO aerodynamic excitation and often neglects LEO aerodynamic excitation introduced by a certain stator asymmetry layout. This results in existing models being inadequate for designing stator asymmetry to control LEO blade forced response.

Based on the premise that pitch differences between two segments govern potential field differences and thereby suppress LEO aerodynamic excitation amplitudes [17], this study investigates aerodynamic excitations on rotor blades across various 2-segment non-even-split layouts. A pioneering simplified model effectively suppressing both HEO and LEO aerodynamic excitations is introduced. The accuracy of the simplified model is verified through full-annulus unsteady numerical simulations of various 2-segment non-even-split layouts. This model can be employed to design stator asymmetry configurations for turbomachinery components with varying stator vane counts. It also provides theoretical support for the enhanced application of stator asymmetry in mitigating forced response on rotor blades in engineering applications.

2. Numerical Methods

The in-house computational fluid dynamics (CFD) code Hybrid Grid Aeroelasticity Environment (HGAE) was used to carry out the numerical simulation on forced response in this paper. HGAE is a three-dimensional, unsteady, time-accurate, Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes (RANS) solver. It has been widely used for aerodynamic and aeroelastic analyses of turbomachinery and has been well-validated in various typical cases [18,19,20,21]. More specific information about the software and validation cases can be found in Zheng [22,23].

A. Aerodynamic Models

The integral form of the unsteady compressible Navier–Stokes equation is expressed as follows:

where is the control volume, is its boundary, and the surface area of the element is denoted using . Equation (1) also contains the vector of conservative variables (), the convective () and viscous flux vectors (), and the source term vector (). They can be expressed in the following equations:

The governing equations for the multi-block grid are discretized using the finite volume method. Roe’s approximate Riemann solver and the Monotone Upwind Scheme for Conservation Law extrapolation are employed to calculate convective terms and central differences for the diffusion fluxes [24,25]. The unsteady flow computations are conducted using Jameson’s dual time-stepping method for an implicit scheme with 15 sub-iterations [26]. The well-proven Menter Shear Stress Transport (SST) Turbulence Model is used for the calculation. More details can be found in Menter [27].

B. Structural Models

The structural dynamics equations of the linear aeroelastic model are employed:

where the mass matrix , stiffness matrix , damping matrix and displacement vector are on the left side of the equation, which can be obtained by finite element calculations. The right side of the equation, , presents the aerodynamic force vector on the blade surface. The modalized structural dynamics equations can be obtained by coordinate transformation :

where is the mode shape vector and represents the modal deflection. The modal damping and natural frequency of mode are denoted by and , respectively. is the modal projection of the aerodynamic force vector on the mode shape . represents the number of mode shapes to be analyzed.

The in-house code HGAE integrates the flow solver and the structural solver described above and adopts an uncoupled approach that does not consider the blade motion when performing the numerical simulation of the forced response. In the uncoupled solver, the unsteady pressures on the blades are all converted to modal forces (Equation (8)) by HGAE:

where are the pressure vector , application area () and normal unit vector () for mode at node index , respectively. The strength of the modal force for a particular mode is determined by the pressure perturbation and the correlation between the pressure perturbation and the structural mode shape. Since this study focuses on comparing the relative trends in response levels between different stator asymmetric layouts, the maximum blade vibration amplitude based on the modal force is used to carry out the subsequent study. is also widely recognized and accepted in previous studies on forced response [28,29,30], and can be obtained by further processing of the modal force (Equation (9)):

where the value of the maximum modal shape obtained from the modal analysis is denoted as , and the aerodynamic damping ratio ζ is calculated by the coupling method.

3. Geometrical Model and Computational Grid

3.1. Single-Stage Turbine

For the single-stage turbine chosen in this study, there are 16 stator vanes, each with a height of 75 mm and an aspect ratio of 0.77. The rotor row comprises 47 blades, featuring a height of 74 mm and an aspect ratio of 2.24. Additional design parameters for the geometric model are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Geometry parameters and operating conditions.

3.2. Grid Independence and Code Validation

3.2.1. Grid Independence

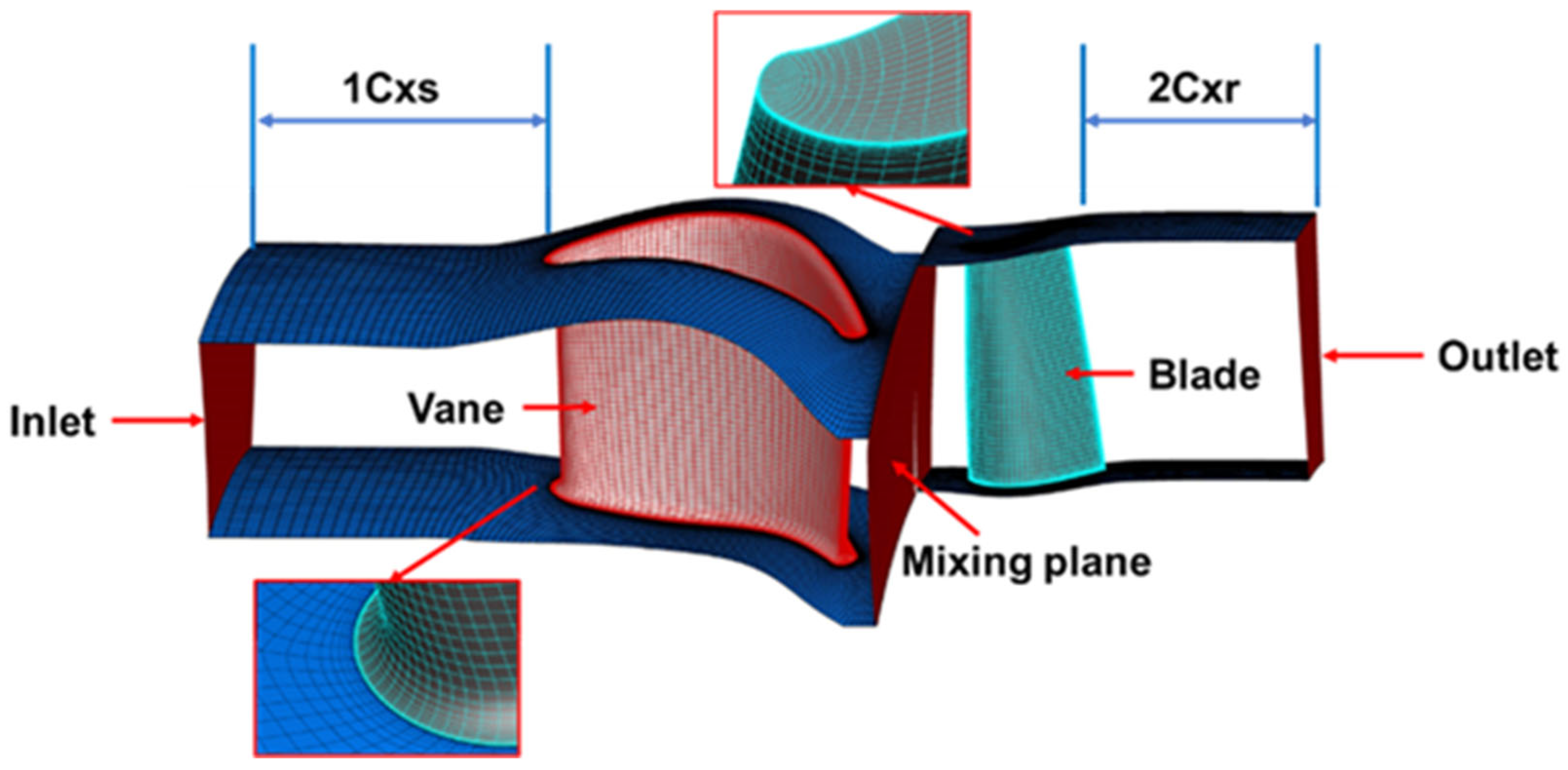

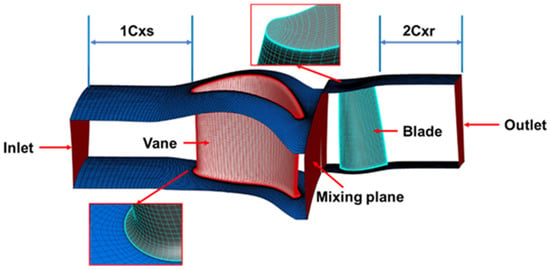

The computational domain for the turbine stage is illustrated in Figure 1. The inlet is located at 1 Cxs (stator chord) from the leading edge of the stator vanes. Conversely, the outlet is situated 2 Cxr (rotor chord) downstream from the trailing edge of the rotor blades. Additionally, static pressure is applied to the hub (radial pressure equilibrium).

Figure 1.

Computational domain of the turbine stage.

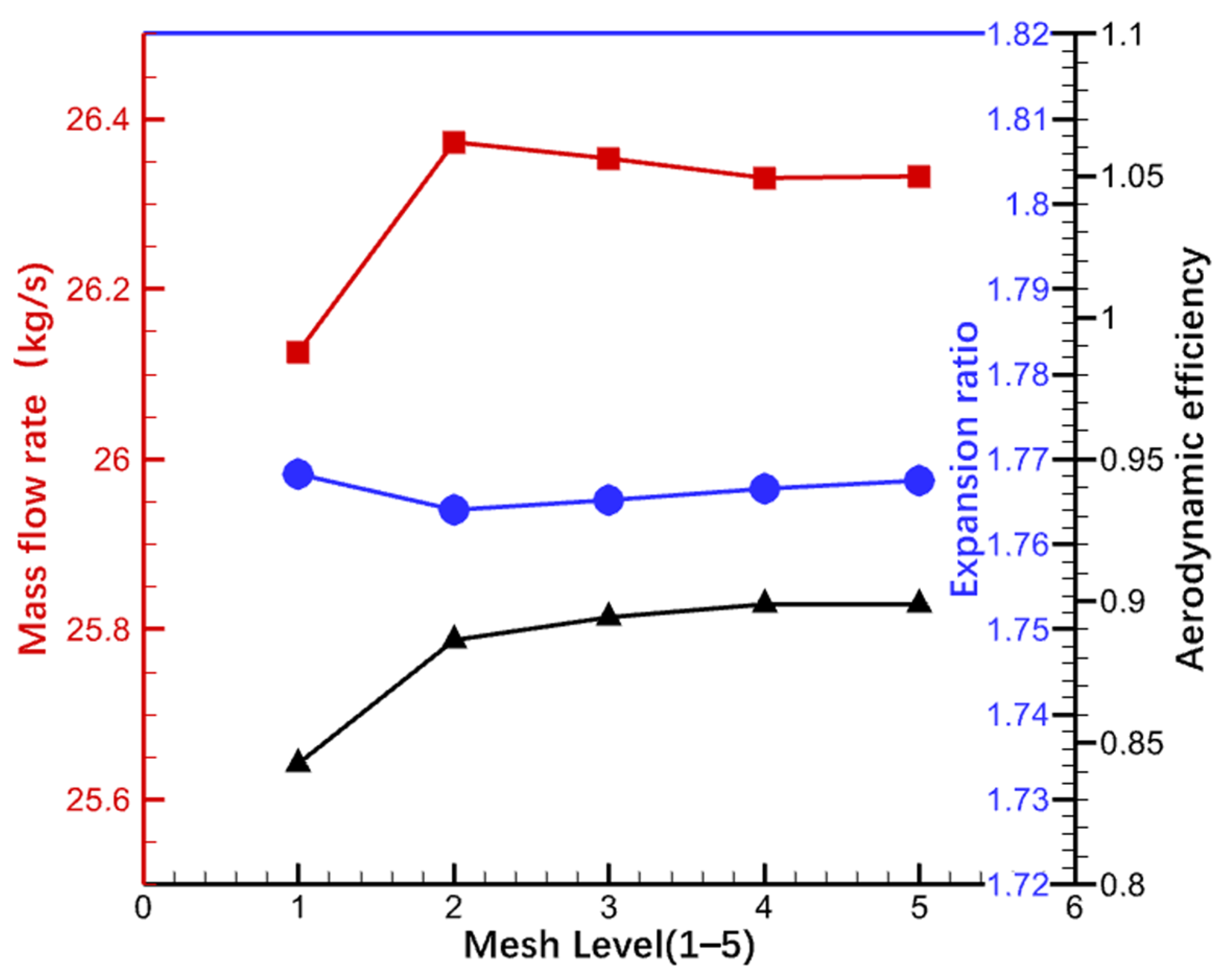

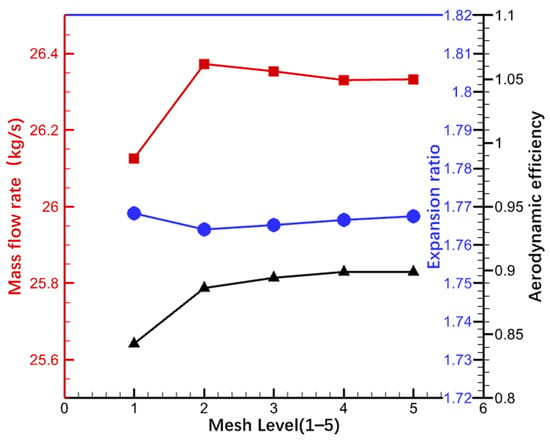

The computational domain of the turbine stage was discretized using structured hexahedral elements, achieving grid independence through the evaluation of five distinct grid configurations. All solutions examined in the grid independence study were single-passage steady solutions at the design operating conditions, as outlined in Table 1. The interfaces between the stator and rotor rows were defined as mixing planes, while periodic boundary conditions were established for both the stator and rotor rows. The computational results across various grid configurations were assessed based on several criteria: static pressure distribution on the blade surface, exit flow angle, expansion ratio, aerodynamic efficiency, and mass flow rate. This paper presents only the results for aerodynamic efficiency and mass flow rate, which are illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Grid independence analysis.

Considering the accuracy and computational cost, the Level 3 grid configuration was chosen for subsequent analyses in this study. This configuration has a total of 1,084,020 nodes in the single-passage turbine stage, with 69 × 85 × 37 and 61 × 101 × 25 grid distributions in the streamwise, spanwise, and pitchwise directions in the stator and rotor rows, respectively. The numbers of nodes for the two blade rows are 590,835 and 493,185, respectively. The near-wall grid resolution with y+ < 1 satisfies the requirements of the Menter SST Turbulence Model.

3.2.2. CFD Code Validation

The validation of the CFD code was conducted by comparing the simulation results from the in-house code (HGAE) with those obtained from the commercial software (NUMECA 14.5). Since this paper emphasizes aerodynamic excitation and performance, the accuracy of the in-house code was verified based on several factors: the static pressure distribution on the blade surface, the exit secondary flow, the pressure field at the S1 flow surface, and the aerodynamic performance of the turbine stage. The computational results from both CFD codes show strong agreement. In this section, only the results of aerodynamic efficiency and expansion ratio are given (Table 2), where the aerodynamic efficiency is defined through the total inlet enthalpy and total outlet enthalpy as shown in Equation (10):

where is the isentropic total enthalpy at the outlet.

Table 2.

The simulation results of different CFD codes.

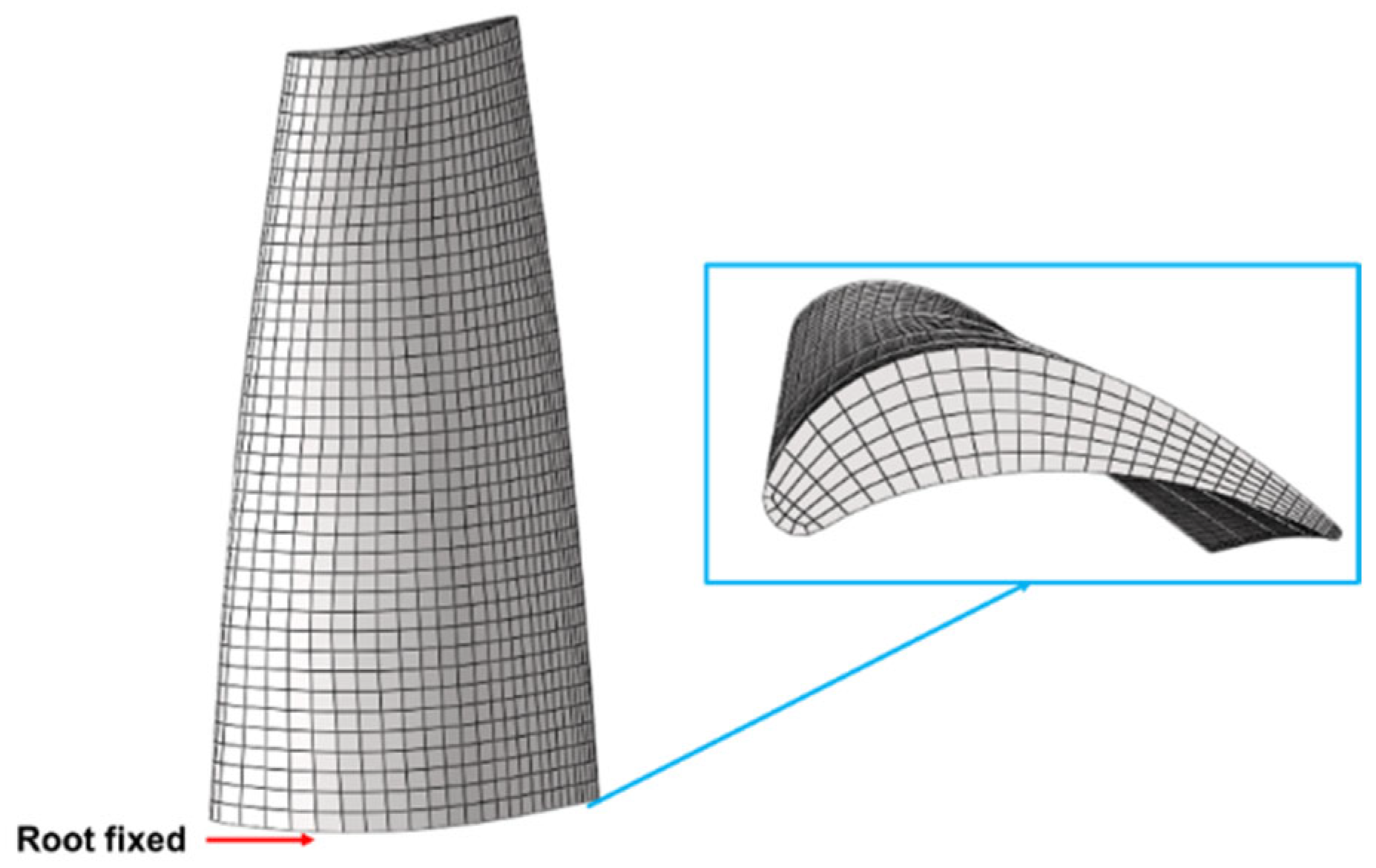

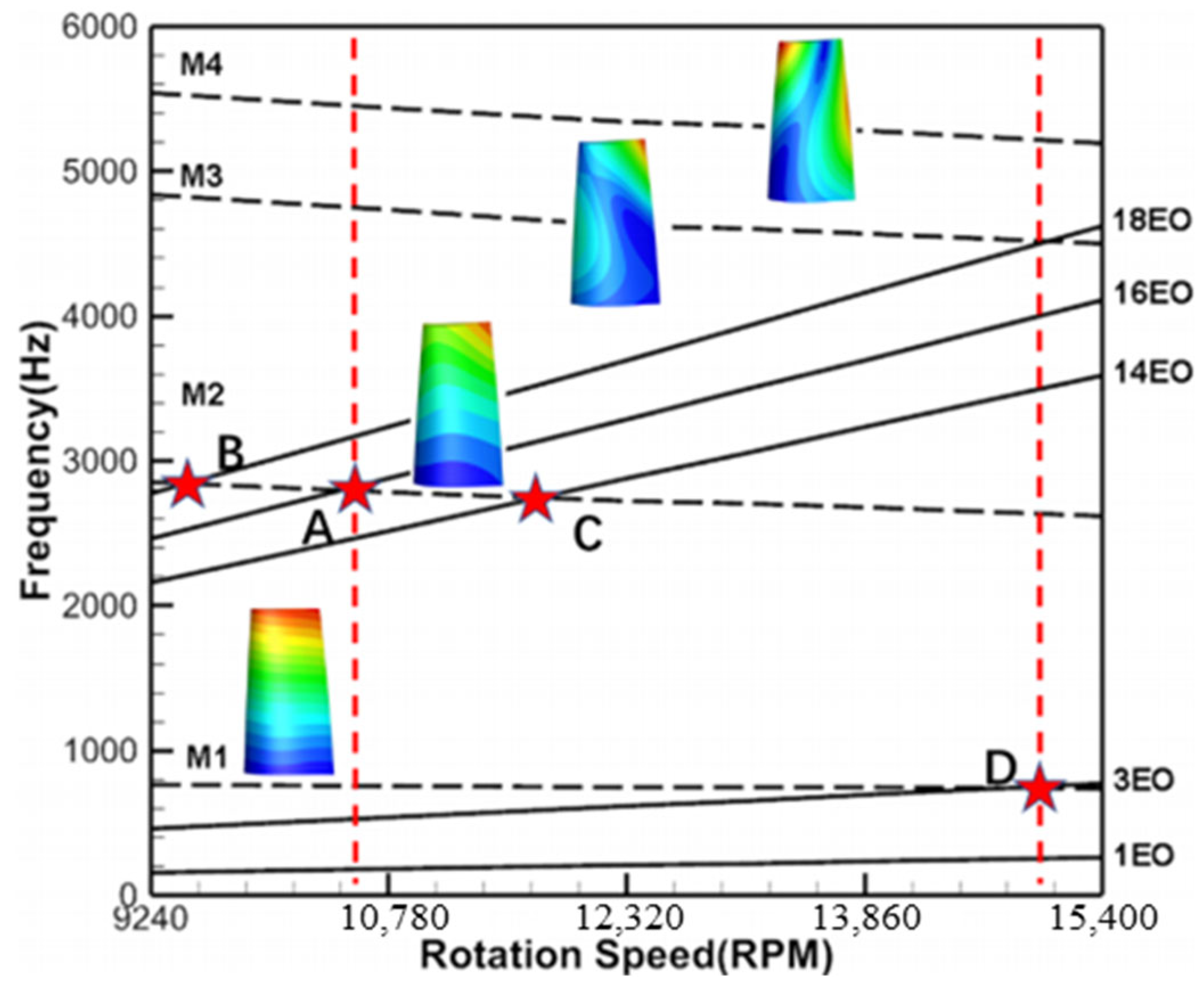

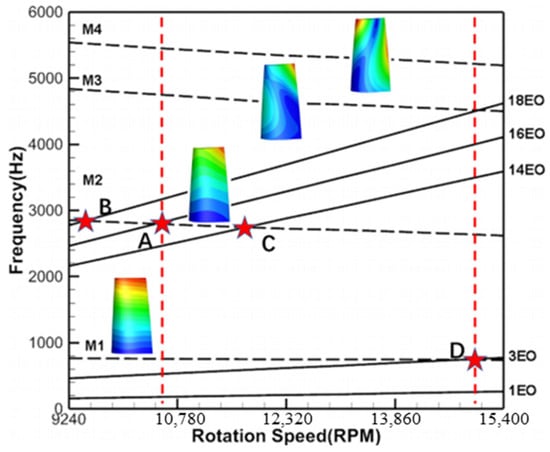

3.3. Rotor Campbell Diagram

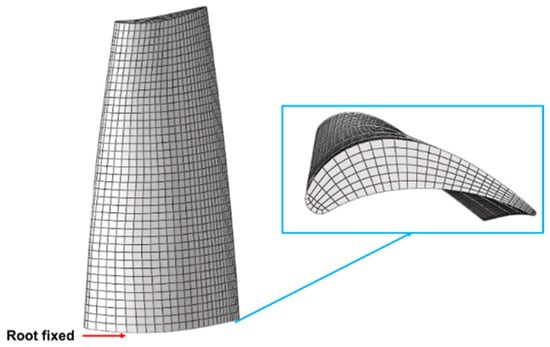

The finite element model of the rotor blade was discretized employing a hexahedral mesh (Figure 3). The selected material for the blade was a high-temperature alloy, characterized by an elastic modulus of 155 GPa, a Poisson’s ratio of 0.31, and a density of 8.44 g/cm3. For the modal analysis, fixed constraints were applied at the blade root to determine the frequencies and modes of the rotor blades at various rotational speeds. The Campbell diagram for the rotor blade is presented in Figure 4, illustrating the first four orders of the natural frequency lines associated with the rotor blade.

Figure 3.

Finite element model of the rotor.

Figure 4.

The Campbell diagram of the rotor blade.

The possible resonance points are marked with red pentagrams in Figure 4, where the 14EO, 16EO, and 18EO external excitations cross the second-order natural modes (M2) of the rotor blades, and the 3EO crosses the first-order modes of the rotor blades, denoted as 3EO_M1 (Point D). For this single-stage turbine, the VPF corresponding to the 16 vanes of the upstream stator row will excite the M2 resonance response of the rotor blades at 68% design rotation speed, denoted as 16EO_M2 (Point A).

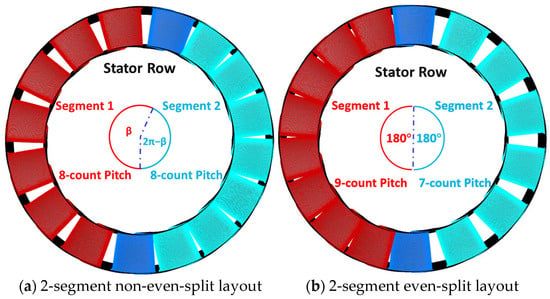

4. Stator Asymmetric Layouts

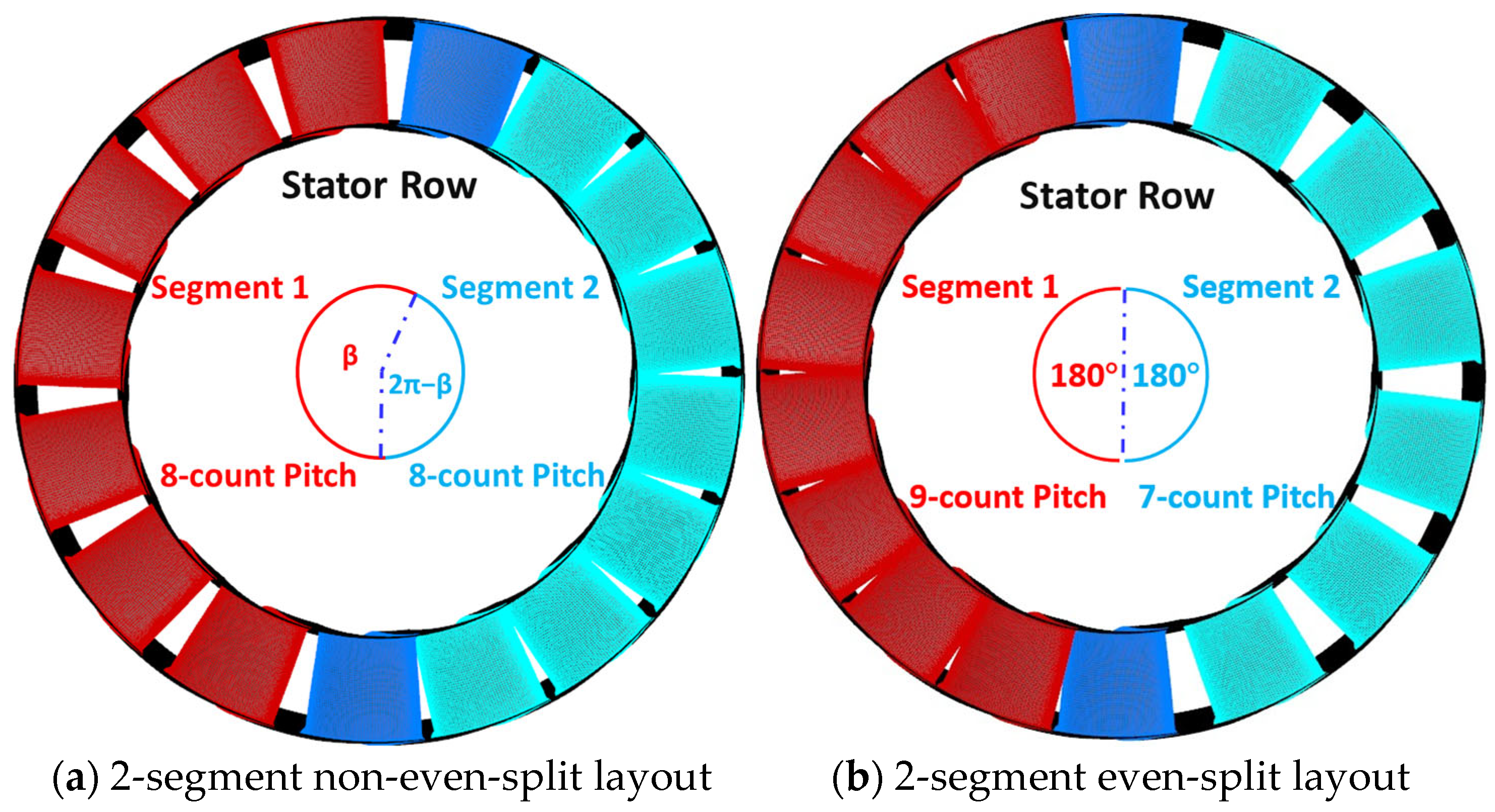

The previous study proposed a 2-segment non-even-split layout (Figure 5a) that effectively reduces LEO aerodynamic excitation introduced by the 2-segment even-split layout [13]. For the 2-segment non-even-split layout illustrated in Figure 5a, each segment occupies unequal circumferential angles, while the number of stator pitches in each segment remains equal. The circumferential angle occupied by segment 1 is denoted as β, while the angle occupied by segment 2 is represented as 2π − β. Given that both the HEO and LEO amplitudes are influenced by the circumferential angle, the suppression effects of various circumferential angles β on different engine order (EO) aerodynamic excitations remain unknown. To address this, two cases of the 2-segment non-even-split layout (Table 3) are designed for a preliminary analysis of the impact of circumferential angle β.

Figure 5.

Schematic of stator asymmetric layouts.

Table 3.

The circumferential angles occupied by two segments.

The layout with uniform pitch in the full annulus (Baseline_Case0) is used as a comparison to test the suppression effects of different stator asymmetric layouts on the HEO aerodynamic excitation. To better evaluate the suppression effect of the 2-segment non-even-split layout on the LEO aerodynamic excitation, a 2-segment even-split layout is also designed as another comparison case, identified as Asy_Case1 (Figure 5b).

The in-house CFD code was used to carry out full-annulus unsteady calculations for each case at multiple resonance rotational speeds. To examine the strength of the LEO forced response induced by each asymmetric layout, the 2-segment non-even-split layout (Table 3) and 2-segment even-split layout (Asy_Case1) were selected to be calculated at the 3EO_M1 resonance speed (point D). The Baseline_Case0 was calculated at 16EO_M2 resonance speed (point A) as a reference to measure the suppression effect of the HEO aerodynamic excitation.

The full-annulus mesh was obtained by rotationally duplicating the single-passage mesh, and the number of full-annulus mesh points for the turbine stage is about 32 million. The aerodynamic disturbances of the stator row are propagated to the rotor row through the sliding plane. The steady converged solution of the full-annular flow field was used as the initial flow field for the unsteady flow calculation. Considering the calculation accuracy and time cost, the time step of unsteady calculation for resonance point A was set to 3.787 , and the time step for resonance point D was set to 2.672 . It takes 32 time steps for the rotor blades to turn through 1 rotor pitch and about 94 steps to turn through 1 stator pitch. When selecting the initial iteration steps, two primary criteria must be considered. The first criterion is that the dominant aerodynamic parameters—such as inlet and outlet mass flow, aerodynamic efficiency, and axial force—should exhibit significant periodic behavior as the time step iterations progress. The second criterion requires that the dominant aerodynamic parameter decrease by at least over the course of 15 sub-iteration steps. Given that the unsteady flow field in the turbine stage typically necessitates post-processing of the computational data for the entire cycle, the total number of iteration steps will be one rotation cycle greater than the initial iteration steps.

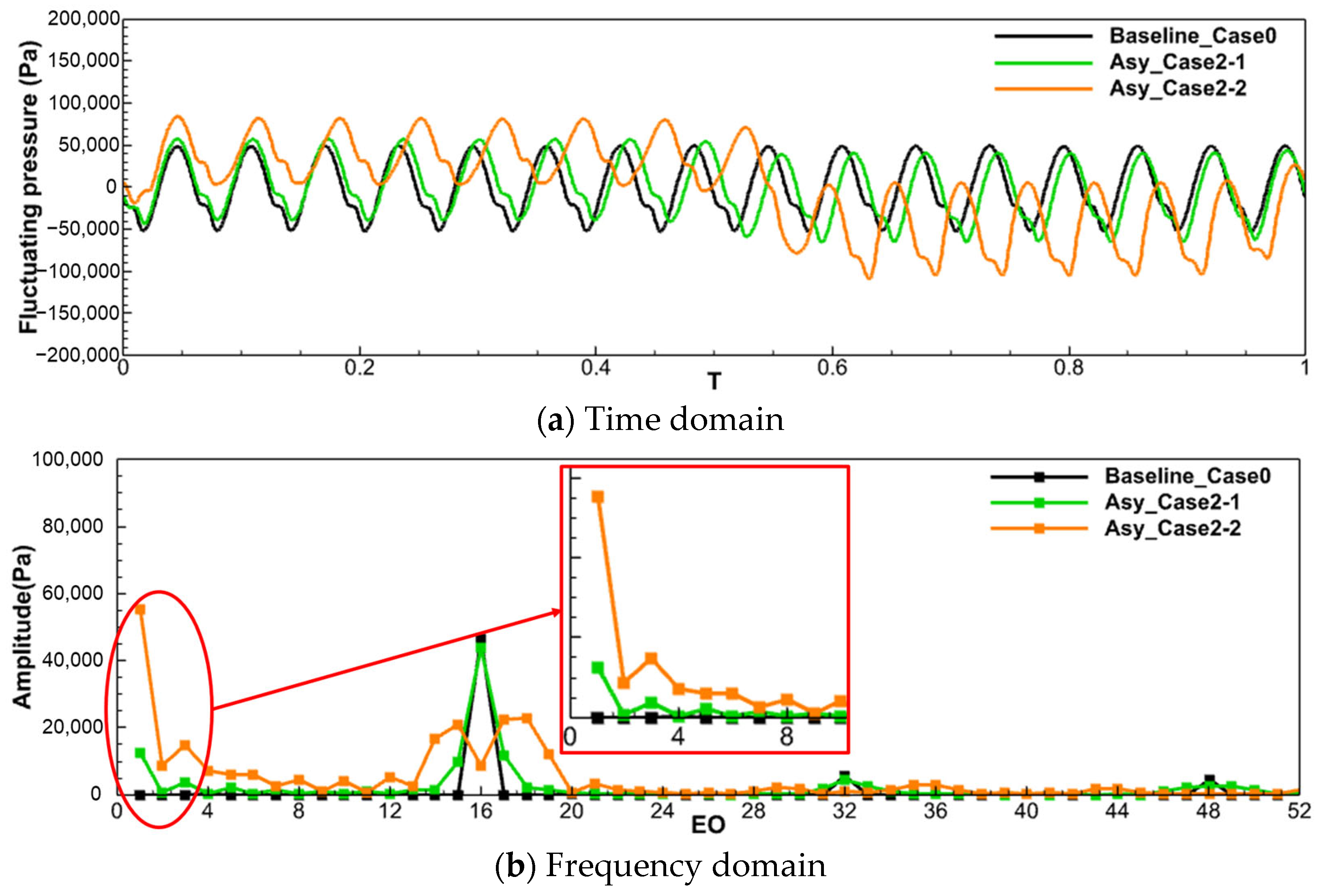

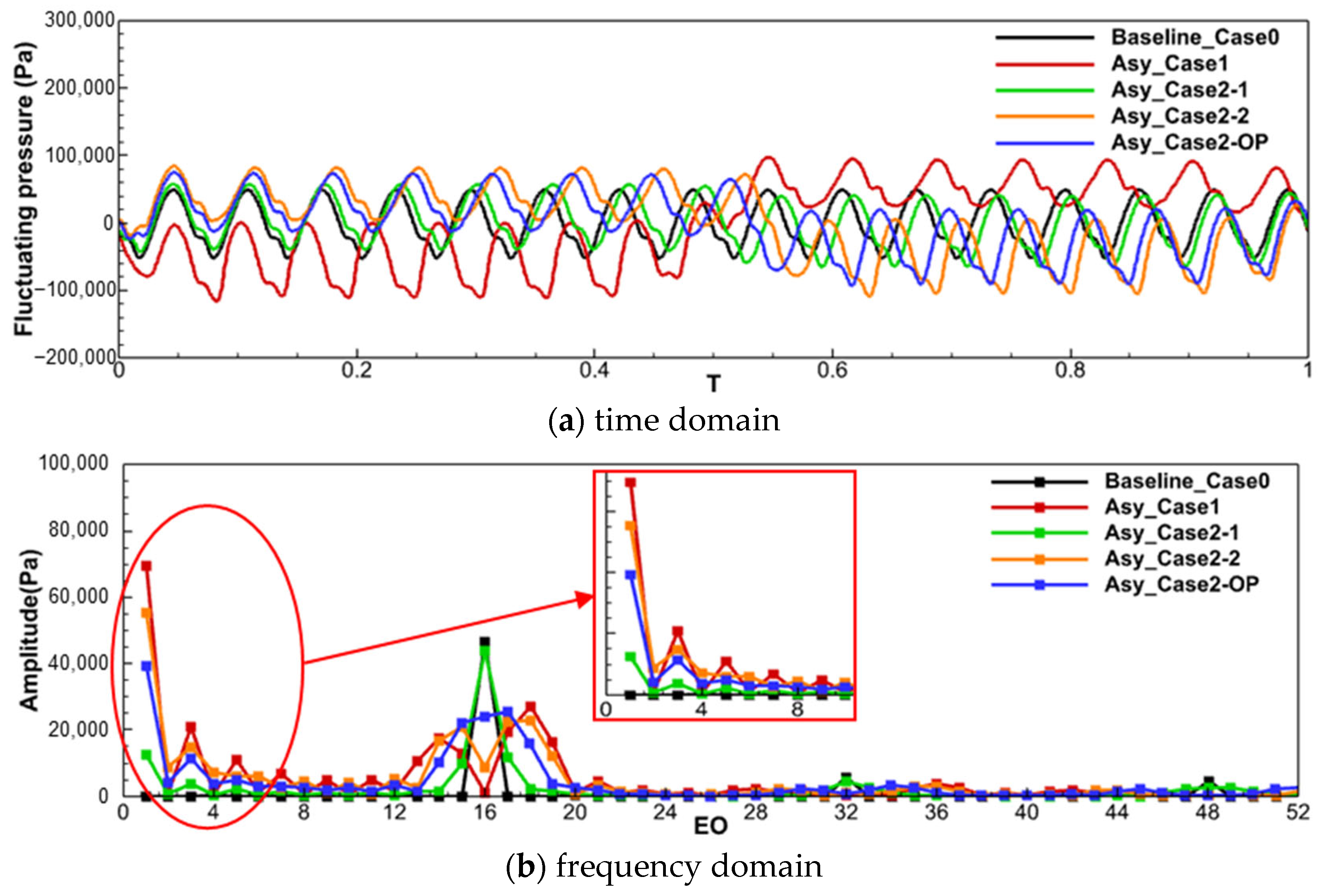

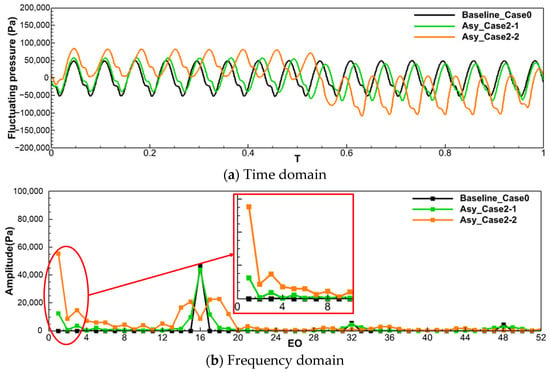

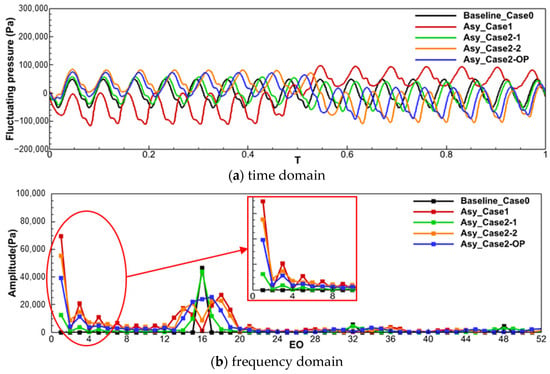

5. Aerodynamic Excitation on Rotor Blades

To investigate the suppression effects of different 2-segment non-even-split layouts (refer to Table 3) on aerodynamic excitations at different engine orders (EOs), the fluctuating pressure—defined as the transient pressure minus the time-averaged pressure for the last rotation cycle (T = 0–1)—is monitored at the leading edge of the rotor blade. The fluctuating pressure values in the time and frequency domains for Baseline_Case0 and the 2-segment non-even-split layout are presented in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

The fluctuating pressure in the time and frequency domains for different layouts.

In the time domain (Figure 6a), the fluctuating pressure for Baseline_Case0 exhibits 16 small cycles, corresponding to the 16 vanes. The excitation components in the frequency domain (illustrated by the black line) predominantly feature the 16EO (dominant frequency) along with its harmonics. The fluctuating pressure curve for the 2-segment non-even-split layout is distinctly divided into two segments within a single rotation cycle, and the number of small cycles in each segment aligns with the blade pitch counts in each segment. The stator asymmetry facilitates the transfer of energy from the VPF (16EO) to adjacent frequencies, and thus reduces the VPF amplitude, as evidenced in the frequency domain (Figure 6b). Notably, the amplitudes of the added neighboring frequencies are significantly lower than that of the VPF (16EO) in Baseline_Case0.

Importantly, the two 2-segment non-even-split layouts exhibit diametrically opposite effects on the suppression of the VPF and LEO aerodynamic excitations. In the frequency domain, although the amplitudes of the LEO aerodynamic excitations in Asy_Case2-1 (represented by the green line) are lower, the amplitude of the 3EO aerodynamic excitation is only 8% that of the 16EO aerodynamic excitation observed in Baseline_Case0 (depicted by the black line). However, the amplitude of the 16EO aerodynamic excitation in Asy_Case2-1 is not significantly reduced compared to Baseline_Case0 (5.7% decrease), which is insufficient to effectively diminish the VPF amplitude.

Conversely, the results for Asy_Case2-2 (illustrated by the orange line) demonstrate a stark contrast. The amplitude of the 16EO aerodynamic excitation is significantly reduced by 81% compared to Baseline_Case0 (black line). However, the amplitude of the LEO aerodynamic excitation remains elevated. Specifically, the amplitude of the 1EO aerodynamic excitation is 118% of that of the 16EO in Baseline_Case0, while the amplitude of the 3EO aerodynamic excitation is 32% of that of the 16EO in Baseline_Case0.

Since the 2-segment non-even-split layout is contingent upon the angle that the two segments occupy within the full annulus, the results indicate that an inappropriate circumferential angle assignment cannot effectively suppress both high-amplitude HEO and LEO aerodynamic excitations simultaneously. Consequently, there may exist an optimal circumferential angle assignment for the 2-segment non-even-split layout. Identifying this optimal layout may necessitate the computation of various cases individually, treating the circumferential angle as the independent variable, and analyzing the suppression effect of each configuration. However, the substantial computational cost associated with this approach complicates the attainment of a truly ideal stator asymmetry layout. Therefore, establishing a fast and accurate simplified model for stator asymmetry design is crucial for addressing this challenge.

6. Simplified Model for Stator Asymmetry Design

The primary objective of stator asymmetry design is to mitigate the amplitude of potentially harmful aerodynamic excitations on rotor blades. Accurately predicting the frequency components and amplitudes of these aerodynamic excitations is essential for developing a simplified model for selecting the optimal stator asymmetry layout. In the symmetric case for a single-stage turbine, the downstream rotor blades are subjected to impulsive aerodynamic excitation from the wake and potential field of the stator as they rotate and sweep through the upstream stator passages. This aerodynamic excitation acting on rotor blades can be expressed as

where represents a constant term associated with the average value of the aerodynamic excitation on the rotor blade, is the rotation frequency, and and correspond to the amplitude and phase of the aerodynamic excitation at the nth rotation frequency. When n is equal to the number of stator passages, is the excitation level that corresponds to the stator VPF.

For the 2-segment stator asymmetry, although the transitional regions between each segment may create complex flow physics, their contribution to aerodynamic excitation could be rather small. Therefore, two assumptions are introduced to simplify the modeling, and their impact on the model accuracy is assessed later:

(1) The rotor blades are subjected to the same intensity of aerodynamic excitation as they rotate through each stator passage within the same segment.

(2) The effect of each stator segment on the rotor blades is independent.

Then, the aerodynamic excitation to which the rotor blades are subjected during the whole rotation period can be regarded as a combination of the fluctuating pressures in the two symmetrical cases. Therefore, the piecewise function is used to model the aerodynamic excitation, which can be expressed as

where and represent the vane counts of segments 1 and 2 expanding to the full annulus, respectively. and are the constants associated with the vane loads of the two segments of the stator rows. and denote the amplitude and phase of , while and correspond to the amplitude and phase of . The variable indicates the circumferential angle occupied by segment 1. This piecewise function contains many unknown quantities, and its simplification is advantageous for rapidly solving this excitation model.

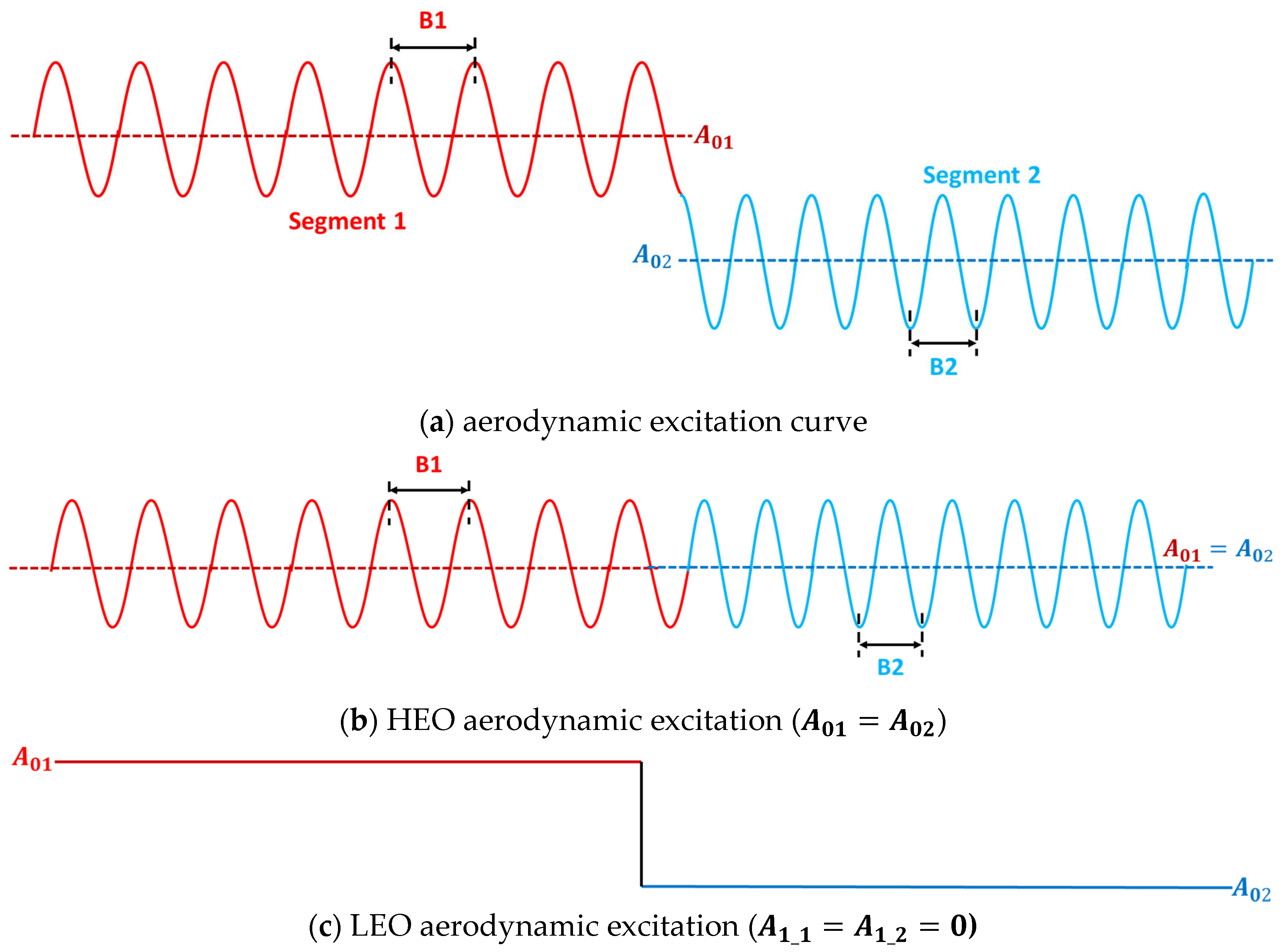

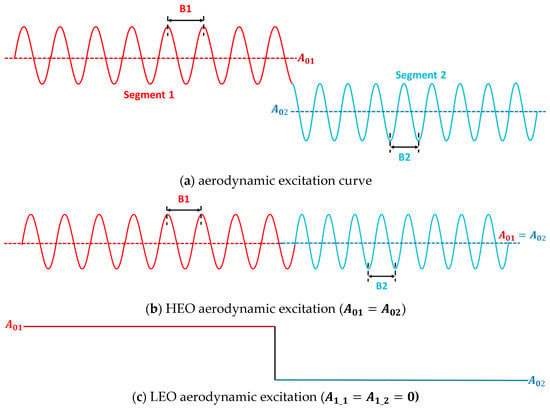

By setting = , the aerodynamic excitation curves can be plotted for rotor blade rotation through the asymmetric layout of the 2-segment stator (Figure 7a), where the red and blue lines correspond to those induced by segments 1 and 2 of the stator rows, respectively. This setup can greatly reduce the difficulty of modeling, although it may have an impact on the prediction accuracy of high-order aerodynamic excitation. The prediction accuracy of the model, considering the above assumptions, will be verified later.

Figure 7.

Schematic of the aerodynamic excitation model and sub-models.

An increase in stator pitch (B1) within segment 1 resulted in a rise in load, and a decrease in stator pitch (B2) within segment 2 resulted in a fall in load. The average amplitudes ( and ) referred to in Equation (12) in relation to the blade loads are identified in Figure 7a. Previous studies have demonstrated [17] that the LEO aerodynamic excitation resulting from stator asymmetry primarily arises from the disparity in the average amplitude of the potential field across different segments. The effect of the average amplitude is separated from the aerodynamic excitation to analyze the LEO aerodynamic excitation. Therefore, the transient pressure variations on the rotor blade during one rotation cycle (Figure 7a) are decomposed into a superposition of two aerodynamic excitation curves (Figure 7b,c).

In Figure 7b, the average amplitudes of segments 1 and 2 are equal (), when only the HEO aerodynamic excitation is considered. The aerodynamic excitation curves in Figure 7c contain only the average amplitude of the two segments, and the fluctuation amplitude ( and ) associated with HEO is 0, which can be used to analyze the LEO aerodynamic excitation. In this paper, two sub-models are established to predict the HEO and LEO aerodynamic excitations corresponding to Figure 7b and c, respectively. A detailed description of both sub-models is provided in the following section.

6.1. Sub-Model for HEO Aerodynamic Excitation

When only the HEO aerodynamic excitation is considered, as illustrated in Figure 7b, both the average amplitude and the fluctuation amplitude of each sine wave are identical. The aerodynamic excitation comprises solely the HEO components introduced by the upstream stator asymmetry, excluding any contribution from LEO aerodynamic excitation. As the rotor blades rotate, the circumferential non-uniformity of the flow field induced by the upstream stator vanes behaves like several pulse signals equal to the number of stator blades. The aerodynamic excitation acting at a specific point on the rotor blades can be represented as a linear superposition of multiple sinusoidal functions by means of the Fourier series [5,14]:

Each of these sinusoidal functions possesses distinct amplitude components and frequency . From the perspective of fluid physics, the flow field at the outlet of the upstream stator row is a circumferential non-uniform flow field corresponding to different orders of circumferential spatial harmonics. As the rotor blades rotate and sweep over the upstream flow field, they receive the sum of the different orders of aerodynamic excitation.

Since the circumferential non-uniform flow field at the outlet of the upstream stator row serves as the source of aerodynamic excitation for the downstream rotor row, analyzing the circumferential distribution of the flow field at the stator row’s outlet at a specific moment proves to be an effective method for predicting the aerodynamic excitation on the rotor blades. Let the circumference of the circumferential flow field at an axial position at the outlet of the stator row be defined as , where K represents the number of stator passages (equivalent to the number of stator vanes), and denotes the pitch of the j-th stator passage. The transition from analyzing aerodynamic excitation for rotor blades to analyzing the source of aerodynamic excitation at the outlet of the stator row is made by converting the time-based Fourier transform of Equation (13) to a spatial Fourier transform. This requires the Fourier series expansion along the circumferential length; then, the aerodynamic excitation at a particular point in space at a given time can be expressed as

Additionally, it follows that

Thus, Equation (14) can be reformulated as

Moreover, the coefficients and can be defined as

The term represents the average value of the function F(x) over the perimeter 2 L. Given that the current model assumes the average and fluctuating amplitudes of the aerodynamic excitation are consistent across all small periods, remains constant. Additionally, the aerodynamic excitation experienced by the rotor blades during one revolution can also be defined as the sum of the aerodynamic forces acting on the rotor blades as they traverse through the i-th stator passage:

where represents the stator chord and is the solidity of the i-th stator passage. Substituting Equation (19) into Equations (17) and (18) yields and . When , the expressions for and are given by

In the case where , the coefficients are defined as

Here, and represent the circumferential positions of the i-th and i+1-th stator, respectively. Equations (14) and (20)–(23) serve as predictive models for determining the amplitude of the HEO aerodynamic excitation. When analyzing a specific stator asymmetry layout, the values for the stator chord and the pitch of each stator passage in the circumferential direction are predetermined. Initially, the length period 2 L and solidity are calculated. Subsequently, these results are substituted into Equations (20)–(23) to obtain and . Finally, the amplitude of each EO aerodynamic excitation is computed using Equation (14). This process can be repeated to determine the amplitude of each HEO aerodynamic excitation for any stator asymmetry layout.

6.2. Sub-Model for LEO Aerodynamic Excitation

When only the LEO aerodynamic excitation is considered (Figure 7c), since the LEO aerodynamic excitation resulting from stator asymmetry primarily arises from the disparity in the average amplitude of different segments, the aerodynamic excitation F(x) is simplified to a square wave:

Here, and are constants associated with the blade loads in the two segments of the stator row, respectively. Given that the blade pitch varies in the 2-segment asymmetric layout, and the solidity is a function of the pitch and the chord length C (), can be expressed as a function of solidity (:

The above equation can be expanded based on the Fourier series representation of a square wave:

Equation (26) indicates that the amplitude of LEO aerodynamic excitation is closely related to the difference in solidity between the two segments of the stator asymmetry layout. The 2-segment non-even-split layouts, characterized by different circumferential angle distributions, exhibit varying solidity differences. To better characterize these asymmetric layouts, the ratio of change in solidity between the asymmetric and symmetric cases is defined, as well as the difference in the ratio of change in solidity between the two segments in the asymmetric case:

where S denotes the solidity value, with the subscript i_asy representing the solidity in segment i (1 or 2) for asymmetric layouts, and subscript uni representing the solidity for symmetric layouts.

The subscripts 1 and 2 correspond to segments 1 and 2, respectively. It will be demonstrated later that there may be critical values of ΔD due to limitations in solidity change and maximum vibration amplitude. To effectively measure the suppression effect of HEO and LEO aerodynamic excitations across different layouts, the suppression effect parameter η is defined. When the subscript is H, represents the suppression effect on HEO aerodynamic excitation:

where is the amplitude of VPF aerodynamic excitation at any position on the rotor blade for the stator symmetric layout (Baseline_Case0), and denotes the amplitude of the nth-order HEO aerodynamic excitation at any position on the rotor blade for a specific asymmetric layout, obtained by calculating in Equation (14).

Similarly, for LEO aerodynamic excitation:

where is the amplitude of the nth-order LEO aerodynamic excitation for the 2-segment even-split layout, and represents the amplitude of the nth-order LEO aerodynamic excitation for the 2-segment non-even-split layout. Both values can be calculated using from Equation (26).

In summary, Equations (19)–(23), (25) and (26) establish sub-models for predicting HEO and LEO aerodynamic excitations on rotor blades, respectively, which together form the predictive model of aerodynamic excitation on rotor blades. Given that this predictive model is solely dependent on geometric parameters, such as the number of stator vanes (K), chord length (C), and solidity (S), it can theoretically predict the relative magnitudes of aerodynamic excitations on turbomachinery components with an arbitrary number of stators. However, as the current simplified model treats HEO and LEO aerodynamic excitations separately based on their excitation sources, it neglects the coupling effects between HEO and LEO aerodynamic excitations. Whether neglecting the coupling effects and the two aforementioned assumptions when establishing the prediction model would affect the accuracy will be assessed through several stator asymmetry cases in the subsequent sections.

6.3. Predictive Model Accuracy Verification

In this section, the suppression effects of two 2-segment non-even-split layouts (Table 3) on HEO and LEO aerodynamic excitations (Table 4) are compared, including the results obtained from the predictive model and numerical simulations.

Table 4.

Comparison of suppression effects of different layouts.

The findings indicate that the suppression effects predicted by the predictive model align closely with those obtained from numerical simulations. Define δ to measure the degree of deviation, which is the ratio of the deviation between the prediction model and the numerical simulation to the maximum suppression effect. For both HEO and LEO aerodynamic excitations, the maximum deviation between the predictive model and numerical simulations does not exceed 10% of the maximum suppression effect. This suggests that the assumptions (given in Section 6) underlying the predictive model have minimal impact on the results, thereby affirming the reliability of the proposed model for predicting aerodynamic excitation.

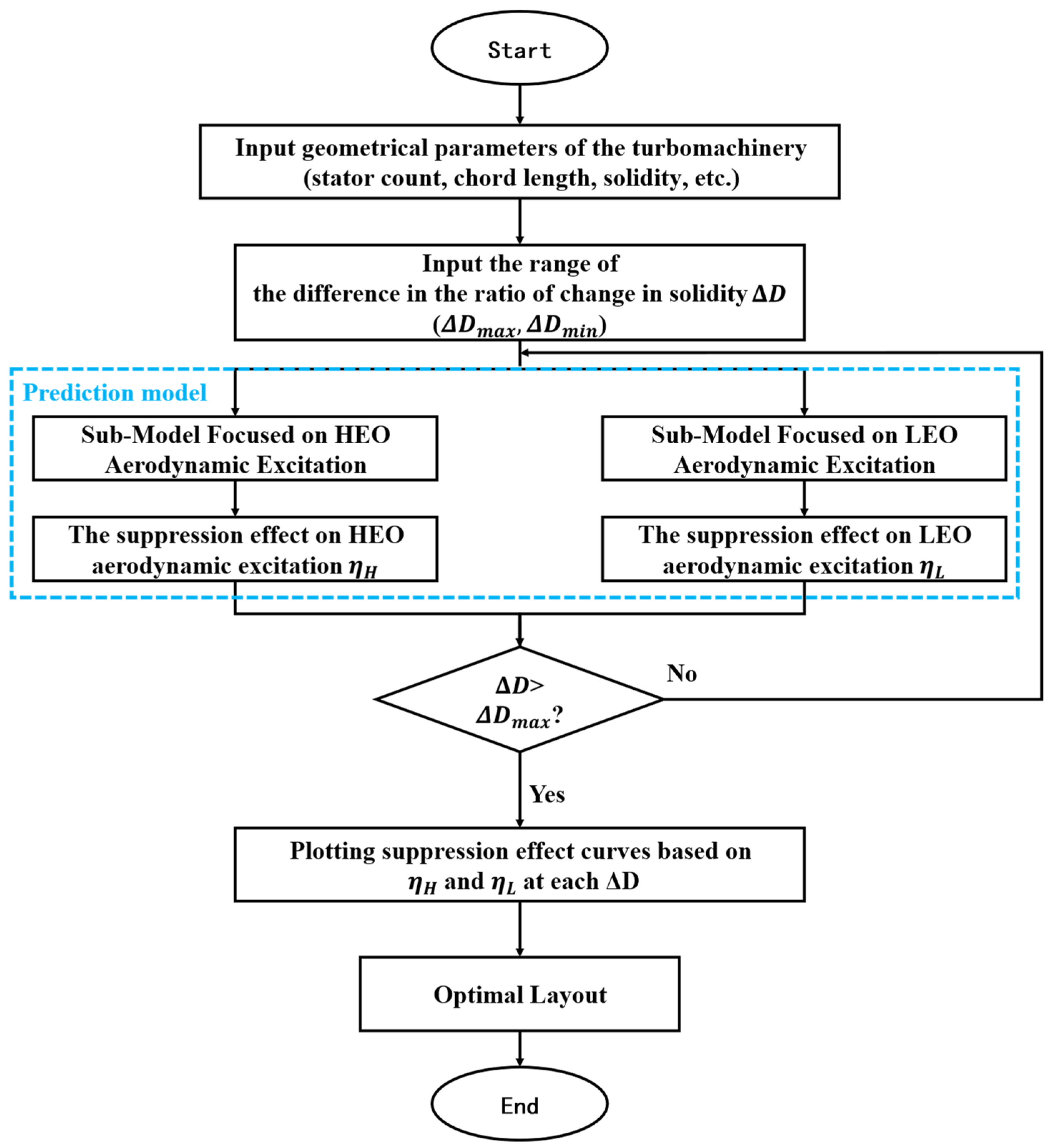

6.4. Simplified Model for Selecting the Optimal Layout

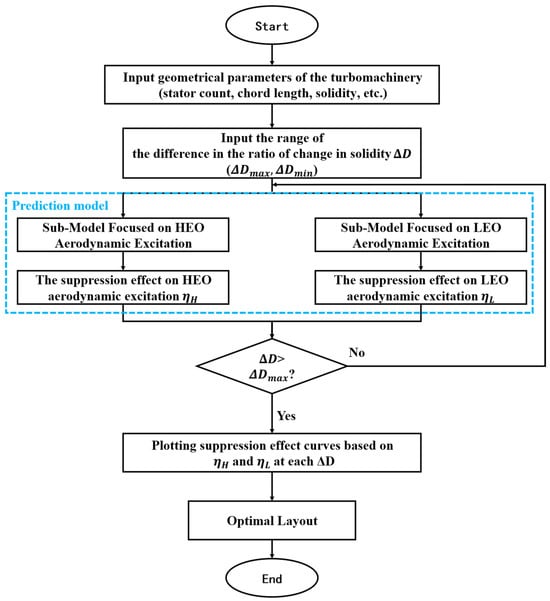

A simplified model for searching the optimal layout is proposed based on the established prediction model of aerodynamic excitation on rotor blades, and the implementation process is shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Simplified model for solving the optimal layout.

- (1).

- First, the geometrical parameters of the turbomachinery components (stator count, chord length, solidity, etc.) are input as required.

- (2).

- Then, the EO range of the aerodynamic excitation to be considered is calculated, and the range corresponding to asymmetric layouts to be considered is also determined. The EO range is related to the Campbell diagram of the rotor under study, and can generally be chosen to be the EOs where resonance is likely to occur. The range can generally be chosen to be slightly larger as required, which avoids the optimal layout being missed. The upper and lower limits of the range are denoted as and , respectively.

- (3).

- Next, the amplitudes of HEO and LEO aerodynamic excitations for different asymmetric layouts (with increasing ) are computed one by one by the prediction model, starting from the until the .

- (4).

- Finally, the suppression effect curves of multiple EO aerodynamic excitations are plotted. Combining the suppression effects and , the intersection of the suppression effect lines of HEO and LEO, for the order of greatest concern, is selected as the optimal stator asymmetry layout of the turbomachinery component under investigation.

7. Optimal Stator Asymmetry Layout

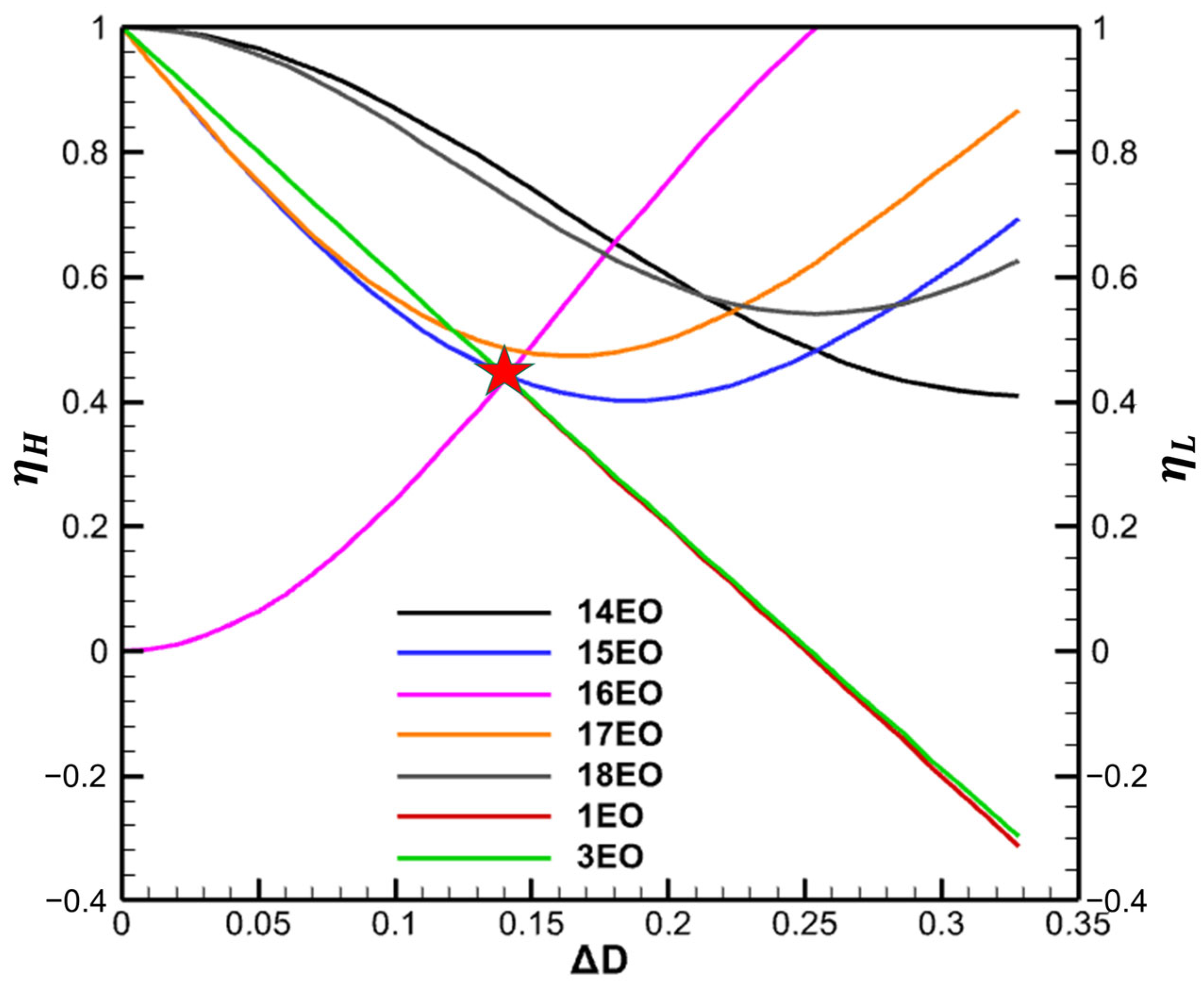

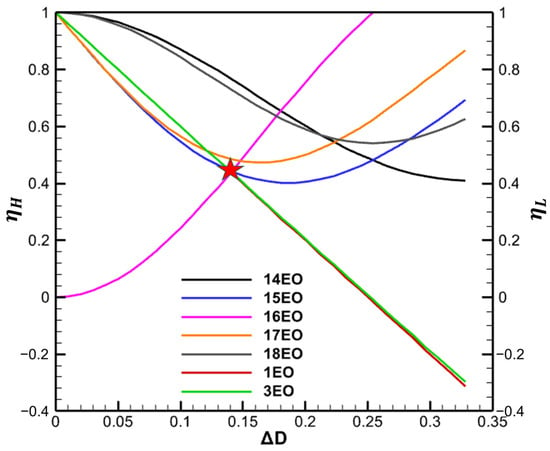

For the single-stage turbine in this paper, the stator count is 16, and the EO range of the aerodynamic excitation concerned is 14–18EO, 1–3EO. The range is then set to 0–0.35. Figure 9 shows the suppression effect curves obtained from the simplified model (Figure 8). The horizontal coordinate is , the left vertical coordinate is the HEO suppression effect , and the right vertical coordinate is the LEO suppression effect .

Figure 9.

Suppression effect curves.

It can be concluded from Equation (28) that as ΔD increases, the difference in solidity between the two segments also increases. Since the solidity and blade load are closely related, the load is closely linked to the exit potential field [13]. As the loads in both segments change, the difference in the potential field caused by the two segments will increase as well. The larger the difference in potential field, the greater the LEO aerodynamic excitation acting on the rotor blades. Then, the suppression effects of LEO (1EO, 3EO) exhibit an approximately linear decrease with increasing , a trend attributed to the growing disparity in potential field between different segments. In contrast, the energy of the excitation force is transferred from the VPF (16EO) to adjacent frequencies (14–15EO, 17–18EO). Consequently, the suppression effect of the VPF (16EO) gradually increases, while the suppression effects of its neighboring frequencies initially decrease before rising again.

Considering the suppression effects of both HEO and LEO aerodynamic excitations, the asymmetric layout corresponding to the intersection of the suppression effects for the VPF (16EO) and LEO aerodynamic excitation indicated by the red star is selected as the optimal layout for the current turbine. It is designated as Asy_Case2-OP, with set at 0.14 and the circumferential angles of the two segments measuring 192.6 degrees and 167.4 degrees, respectively.

7.1. Aerodynamic Excitation on Rotor Blades

To verify the suppression effect of the optimal 2-segment non-uniform layout (Asy_Case2-OP) obtained from the simplified model, the in-house code HGAE was used to carry out the full-annulus unsteady calculations of the Asy_Case2-OP at the 3EO_M1 resonance speed (point D). The fluctuating pressure at the leading edge of the rotor was monitored, and the results from the optimal 2-segment non-uniform layout are compared to other cases presented above (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

The fluctuating pressure in the time and frequency domains for different layouts.

Compared to Baseline_Case0 (black line), the amplitude of the VPF aerodynamic excitation in the 2-segment even-split layout (red line in Figure 10b) is significantly reduced, by 97.87%. Although the amplitudes of the adjacent frequencies (13–15EO, 17–19EO) increase, the highest amplitude (18EO) is only 57.86% of the VPF amplitude in Baseline_Case0. However, more concerning frequency components emerge in the LEO, where the amplitudes of 1EO and 3EO aerodynamic excitations can reach 149.3% and 45% of the VPF amplitude in Baseline_Case0, respectively, leading to a substantial increase in LEO resonance response. The 2-segment non-even-split layout effectively reduces the LEO aerodynamic excitation amplitude associated with the 2-segment even-split layout. Nonetheless, an inappropriate circumferential angle distribution of the two segments can elevate the amplitude of HEO or LEO aerodynamic excitations on the rotor blades, as previously analyzed (Figure 6).

In comparison with the arbitrary two-segment non-even-split layouts (Asy_Case2-1 and Asy_Case2-2), the Asy_Case2-OP selected by the simplified model demonstrates a superior effect in mitigating both HEO and LEO aerodynamic excitations. For HEO aerodynamic excitation, the vane counts of two segments after expanding the full annulus are 15 and 17, respectively. The neighboring frequencies dispersed by the VPFs are calculated as 14, 16, and 18EO using Equations N1 ± 1 or N2 ± 1, thus identifying the primary HEO excitations as 14EO, 15EO, 16EO, 17EO, and 18EO. These excitation components are consistent with the results illustrated in Figure 10b. The highest amplitude among the HEO aerodynamic excitations is only 54.86% of the VPF amplitude in Baseline_Case0, indicating that Asy_Case2-OP effectively suppresses HEO aerodynamic excitation compared to Asy_Case2-1.

Furthermore, Asy_Case2-OP not only exhibits a strong suppression effect on HEO aerodynamic excitation but also significantly reduces the amplitude of LEO aerodynamic excitations. In comparison to Asy_Case2-2, Asy_Case2-OP effectively controls LEO aerodynamic excitations by managing the solidity difference between the two segments, resulting in decreases of 29.13% and 24.62% in the amplitudes of 1EO and 3EO aerodynamic excitations, respectively. This evaluation of the suppression effects of the optimal 2-segment non-even-split layout (Asy_Case2-OP) from the perspective of aerodynamic excitation prompts further investigation into whether the intensity of forced response on the rotor blade is genuinely mitigated, e.g., by comparing the maximum vibration amplitude.

7.2. Maximum Vibration Amplitude

The previous section verified that the simplified model can effectively address the excitation amplitude issue. For a given damping coefficient, it is inferred that the maximum blade vibration amplitude will also be suppressed. This section examines the suppression effect by analyzing the maximum vibration amplitude in each case calculated using Equation (9) with constant aerodynamic damping. The ζ for each operating condition needs to be calculated strictly through the coupling method. Though they all occurred under the 3EO_M1 excitation, and the differences in aerodynamic damping under the same order excitation might be relatively small, a constant aerodynamic damping value can be adopted as an approximation. The maximum vibration amplitude is subsequently normalized by the maximum vibration amplitude at 3EO_M1 resonance speed (point D) of Asy_Case1 as follows:

The normalized maximum vibration amplitudes calculated for both the 2-segment even-split layout and the optimal 2-segment non-even-split layout at the 3EO resonance point are presented in Table 5. Previous research by the authors [13] indicated that the intensity of the LEO forced response induced by the 2-segment even-split layout is significantly high, reaching 10.55 times that of the HEO forced response induced by the VPF. In the current study, the optimal 2-segment non-even-split layout effectively reduces the maximum vibration amplitude of 3EO by 45.5% compared to the two-segment even-split layout. Thus, the optimal 2-segment non-even-split layout not only effectively suppresses the amplitude of HEO aerodynamic excitation but also demonstrates superior suppression of the LEO forced response in comparison to the 2-segment even-split layout.

Table 5.

Normalized maximum vibration amplitudes.

7.3. Aerodynamic Performance

The above studies have demonstrated that the optimal 2-segment non-even-split layout can effectively mitigate the intensity of the LEO aerodynamic excitation introduced by the 2-segment even-split layout. However, active measures to reduce aerodynamic excitation must not compromise aerodynamic performance [5,13,31]. Table 6 provides a comparison of the aerodynamic performance of the turbine stage across different cases.

Table 6.

Comparison of aerodynamic performance.

The aerodynamic performance (expansion ratio and stage aerodynamic efficiency) of the 2-segment even-split layout (Asy_Case1) has decreased by more than 0.2% compared to the symmetric layout (Baseline_Case0). In contrast, for the optimal 2-segment non-even-split layout (Asy_Case2-OP) identified by the simplified model, the changes in aerodynamic performance relative to the symmetric layout are all less than 0.1%. Therefore, the optimal 2-segment non-even-split layout not only exhibits a more effective suppression of resonance response but also significantly mitigates the adverse impact of the 2-segment even-split layout on the aerodynamic performance.

8. Conclusions

In this paper, a pioneering simplified model of stator asymmetry design considering LEO forced response is proposed. Firstly, the full-annular unsteady numerical simulation is carried out by using an in-house CFD code to analyze the suppression effects on HEO and LEO aerodynamic excitations of different 2-segment non-even-split layouts. Then, the simplified model of stator asymmetry considering both HEO and LEO aerodynamic excitations is proposed for the first time, and the accuracy of the simplified model is verified. Finally, the optimal 2-segment non-even-split layout for the studied single-stage turbine is proposed based on the simplified model, and its suppression effect on resonance response and aerodynamic performance is also investigated.

- (1).

- The 2-segment non-even-split layout can effectively reduce the LEO aerodynamic excitation introduced by the 2-segment even-split layout. However, not all 2-segment non-even-split layouts outperform the 2-segment even-split layout. The suppression of VPF or LEO aerodynamic excitation may be compromised if the ratio of change in solidity is either excessively large or too small. There exists an optimal 2-segment non-even-split layout that can suppress both HEO and LEO aerodynamic excitations for the geometrical model under study.

- (2).

- The simplified model of stator asymmetry proposed in this study allows for rapid predictions of suppression effects across any specified range of the ratio of change in solidity () for the turbine model under investigation. The accuracy of the simplified model is verified by comparing the numerical simulations of several stator asymmetric layouts with the predictions generated by the simplified model. The results indicate that the maximum error between the predicted and numerical results for the aerodynamic excitation force does not exceed 10%, and most errors are confined within a smaller range. The simplified model demonstrates robustness, yielding highly accurate predictions.

- (3).

- The suppression characteristics for the current single-stage turbine are illustrated according to the simplified model. The characteristic line facilitates the quick selection of the optimal 2-segment non-even-split layout that effectively suppresses both HEO and LEO aerodynamic excitations. The results reveal that the selected optimal layout reduces the VPF aerodynamic excitation in the symmetric layout by 45.14% and the 3EO aerodynamic excitation introduced by the 2-segment even-split layout by 43.56%, while the negative impact on aerodynamic performance is significantly less than that associated with the 2-segment even-split layout.

In this study, a simplified model for finding the optimal stator asymmetry is proposed that considers the HEO, LEO aerodynamic excitations, and aerodynamic performance. The accuracy of the simplified model is verified with a given single-stage turbine. This paper provides a solid theoretical foundation for the enhanced application of stator asymmetry in engineering, thereby demonstrating substantial engineering value. However, as the current simplified model treats HEO and LEO aerodynamic excitations separately based on their excitation sources, it neglects the coupling effects between HEO and LEO aerodynamic excitations. This omission may result in deviations in the amplitude of certain EO aerodynamic excitations. Some of them may also have resonant intersections in the Campbell diagram, and it is not clear how high the excitation level is. Further work will be carried out to analyze this and further improve the simplified model.

Author Contributions

Y.Z.: Conceptualization (lead); Software (lead); Resources (equal); Project administration (lead); Funding acquisition (lead). X.J.: Conceptualization (supporting); Methodology (supporting); Validation (lead); Formal analysis (lead); Writing—original draft preparation (lead); Writing—review and editing (equal); Visualization (lead). H.Y.: Conceptualization (supporting); Methodology (lead); Data curation (lead); Resources (lead); Supervision (lead). J.H.: Writing—review and editing (equal). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Nomenclature

| A | amplitude |

| C | stator chord |

| ∆D | difference in the ratio of change in solidity between two segments |

| F | aerodynamic excitation |

| f | rotation frequency |

| h | enthalpy |

| L | semiperimeter of the circumferential flow field |

| N | vane count |

| n | wave number of the circumferential flow field |

| p | blade pitch |

| S | solidity of the stator passage |

| T | rotation cycle |

| t | time |

| X | vibration amplitude |

| β | circumferential angle occupied by segment 1 |

| δ | degree of deviation |

| η | aerodynamic efficiency |

| ζ | aerodynamic damping ratio |

| φ | phase |

| ω | blade natural frequency |

| Subscripts | |

| asy | asymmetric layout |

| H, HEO | high-engine-order aerodynamic excitation |

| i, j | index of the stator passage |

| in | inlet |

| is | isentropic |

| L, LEO | low-engine-order aerodynamic excitation |

| max | the maximum value |

| min | the minimum value |

| n | Fourier order |

| nor | normalized value |

| out | outlet |

| uni | symmetric layout |

| VPF | vane passing frequency |

| t | total parameters |

References

- Danforth, C.E. Designing to avoid fatigue in long life engines. SAE Trans. 1967, 75, 248–262. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan, A.V. Flutter and resonant vibration characteristics of engine blades. J. Eng. Gas Turbines Power 1997, 119, 742–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kielb, R.; Chiang, H.W. Recent advancements in turbomachinery forced response analyses. In Proceedings of the 30th Aerospace Sciences Meeting and Exhibit, Reno, NV, USA, 6–9 January 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Chiang, H.W.D.; Kielb, R.E. An analysis system for blade forced response. J. Turbomach. 1993, 115, 762–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, R.H.; Hirschberg, M.H.; Morgan, W.C. Theoretical and Experimental Analysis of the Reduction of Rotor Blade Vibration in Turbomachinery Through the Use of Modified Stator Vane Spacing; NACA-TN-4373; National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics: Washington, DC, USA, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, J.P.; Aggarwala, A.S.; Velonis, M.A.; Gacek, R.E.; Magge, S.S.; Price, F.R. Using cfd to reduce resonant stresses on a single-stage, high-pressure turbine blade. In Proceedings of the Turbo Expo: Power for Land, Sea, and Air, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 3–6 June 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Senn, S.M. Nozzle Ring with Non-Uniformly Distributed Airfoils and Uniform Throat Area. U.S. Patent 14/190,814, 25 September 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, A.J. Gas Turbine Engine Stator Vane Asymmetry. U.S. Patent 10,443,391, 15 October 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, J.P.; Anthony, R.J.; Ooten, M.K.; Finnegan, J.M.; Dean Johnson, P.; Ni, R.H. Effects of downstream vane bowing and asymmetry on unsteadiness in a transonic turbine. J. Turbomach 2018, 140, 101006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, Y.; Mori, K.; Okui, H. Study on the effect of asymmetric vane spacing on vibratory stress of blade. In Proceedings of the Turbo Expo: Power for Land, Sea, and Air, Vienna, Austria, 14–17 June 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, Y.; Li, L.; Li, Q. Asymmetry stator mistuned blade design and research. J. Aerosp. Power 2007, 22, 2083–2088. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, Y.; Hou, A.; Zhang, M.; Sun, T.; Wang, R.; Guo, H. Investigation on the effect of asymmetric vane spacing on the reduction of rotor blade vibration. In Proceedings of the Turbo Expo: Power for Land, Sea, and Air, Düsseldorf, Germany, 16–20 June 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y.; Jin, X.; Yang, H. Effects of asymmetric vane pitch on reducing low-engine-order forced response of a turbine stage. Aerospace 2022, 9, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Hou, A.; Zhang, M.; Niu, Y.; Gao, J.; Guo, H. Analysis on the reduction of rotor blade vibration using asymmetric vane spacing. In Proceedings of the Turbo Expo: Power for Land, Sea, and Air, Montreal, QC, Canada, 15–19 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kurz, R. Transonic flow through turbine cascades with nonuniform pitch. In Proceedings of the ASME 1992 International Gas Turbine and Aeroengine Congress and Exposition, Cologne, Germany, 1–4 June 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Leng, Y.; Key, N.L. Effects of nonuniform blade spacing on compressor rotor forced response and aeroacoustics. J. Propul. Power 2020, 36, 721–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Liao, X.; Fan, W.; Wang, Y.; Mu, Y.; Xin, J. Modeling of the unsteady aerodynamic force of turbine blades considering nonuniform vane pitch. Phys. Fluids 2024, 36, 017141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y. Computational aeroelasticity with an unstructured grid method. J. Aerosp. Power 2009, 24, 2069–2077. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y.; Yang, H. Full assembly fluid/structured flutter analysis of a transonic fan. J. Beijing Univ. Aeronaut. Astronaut. 2013, 39, 626. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y.; Jin, X.; Yang, H.; Gao, Q.; Xu, K. Effects of circumferential nonuniform tip clearance on flow field and performance of a transonic turbine. In Proceedings of the ASME Turbo Expo 2020: Turbomachinery Technical Conference and Exposition, Volume2B: Turbomachinery, Virtual, 21–25 September 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y.; Jin, X.B.; Yang, H. Fast-moving mesh method and its application to circumferential non-uniform tip clearance in a single-stage turbine. J. Appl. Fluid Mech. 2024, 17, 1759–1773. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y. Computational Aerodynamics on Unstructed Meshes. Ph.D. Thesis, Durham University, Durham, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y.; Hui, Y. Coupled fluid-structure flutter analysis of a transonic fan. Chin. J. Aeronaut 2011, 24, 258–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roe, P.L. Approximate Riemann solvers, parameter vectors, and difference schemes. J. Comput. Phys. 1981, 43, 357–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Leer, B. Towards the ultimate conservative difference scheme. J. Comput. Phys. 1997, 135, 229–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jameson, A. Time dependent calculations using multigrid, with applications to unsteady flows past airfoil sand wings. In Proceedings of the 10th Computational Fluid Dynamics Conference, Honolulu, HI, USA, 24–27 June 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Menter, F.R. Two-equation eddy-viscosity turbulence models for engineering applications. AIAA J. 1994, 32, 1598–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahdati, M.; Sayma, A.I.; Imregun, M. An integrated nonlinear approach for turbomachinery forced response prediction part ii: Case studies. J. Fluids Struct. 2000, 14, 103–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahdati, M.; Sayma, A.I.; Imregun, M.; Simpson, G. Multi blade row forced response modeling in axial-flow core compressors. J. Turbomach. 2007, 129, 412–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wang, P.Y. Evaluation of high-order resonance of blade under wake excitation. In Proceedings of the ASME Turbo Expo 2010: Power for Land, Sea, and Air, Volume 6: Structures and Dynamics, Parts A and B, Glasgow, UK, 14–18 June 2010; pp. 995–1001. [Google Scholar]

- Monk, D.J.; Key, N.L.; Fulayter, R.D. Reduction of aerodynamic forcing through introduction of stator asymmetry in axial compressors. J. Propuls. Power 2016, 32, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.