1. Introduction

The aviation industry is committed to achieving net-zero carbon emissions by 2050 [

1]. A potential pathway to achieve this goal is propulsion architectures using hydrogen (H

2) [

2]. Typically, two types of H

2 architectures are investigated: direct combustion of H

2 in a gas turbine engine or electric propulsion using Fuel Cells (FC) [

3]. Examples of both are depicted in

Figure 1.

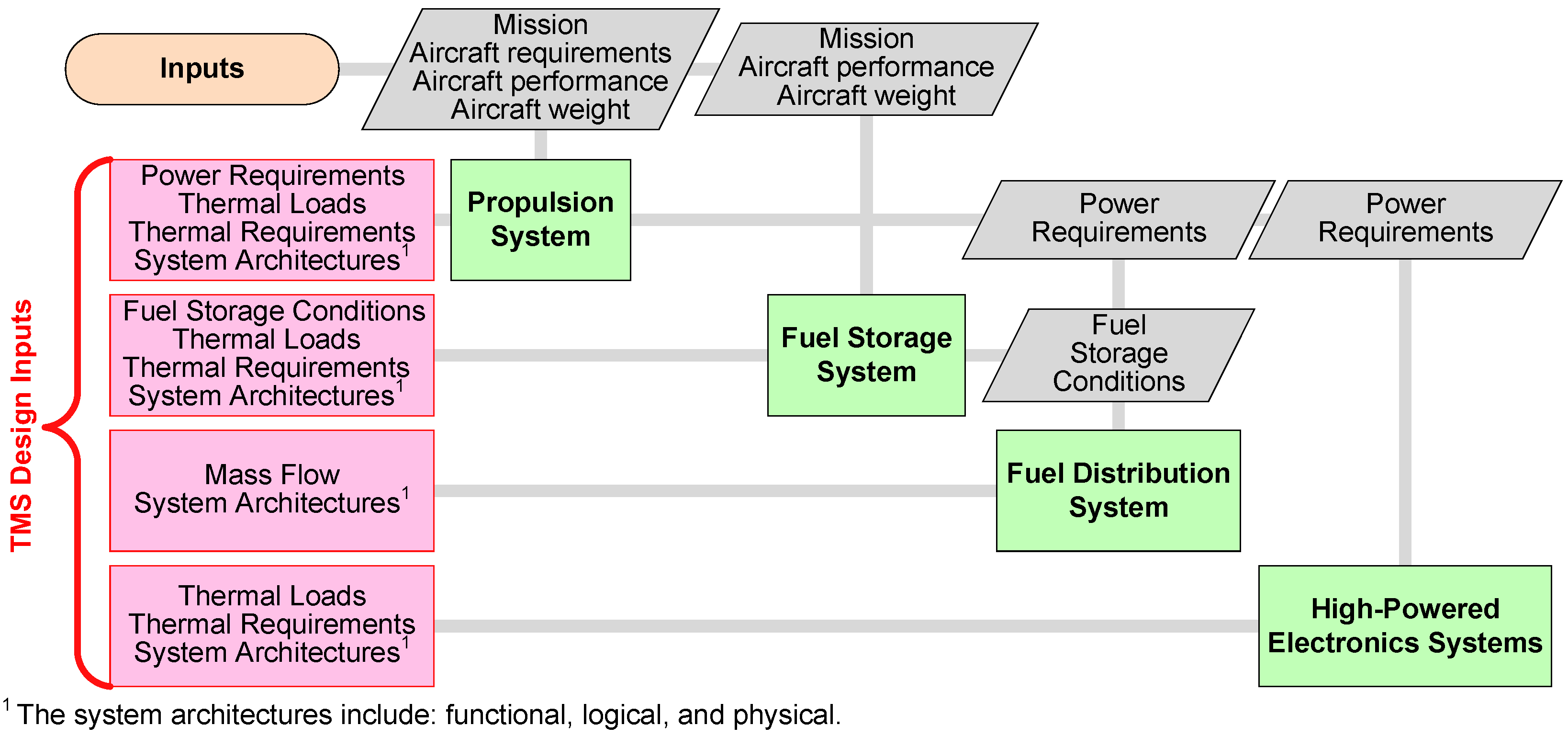

All of these architectures pose new thermal management challenges for aircraft design. The hydrogen must be stored at cryogenic temperatures as liquid hydrogen (LH2) to maximize the volumetric efficiency of the tank. Fuel cells require gaseous H2 and reject significant heat. Finally, power electronics and high-power electric machines require active cooling.

To address these thermal challenges and to develop feasible aircraft concepts, novel, integrated approaches are required for the Thermal Management System (TMS). Jansen et al. [

4] highlighted that ongoing investments to improve the technology readiness level of lightweight, high-efficiency, and high-powered electrical systems for electrified aircraft propulsion require that TMSassessment be integrated at every stage of aircraft conceptualization to ensure solutions are achievable, cost-effective, and satisfy both volume and weight constraints. This integrated solution requirement is becoming a key driver for investigating new design and development methods [

5], as conventional design methods are proving inadequate for electric architectures. Ouyang et al. [

6] examined current integrated power and TMS designs and suggest these systems could address existing challenges. In all-electric aircraft and hybrid-electric propulsion aircraft architectures, the power management system and TMS are interdependent. Managing these domains separately reduces optimization potential, as power management must account for TMS consumption to achieve efficient battery use during flight. A key conclusion from their research is that integrated power and TMS, when paired with appropriate modeling methods, facilitate modular designs that result in a more optimized aircraft.

Another example of an integrated TMS architecture is proposed by Hartmann et al. [

7]; however, in this study, system sizing methodologies remain limited, typically relying on either scaling existing technologies or conducting aircraft-level energy or exergy analyses that may not fully account for the non-linear thermophysical behaviors at cryogenic temperatures. Sarr et al. [

8] investigated hydrogen powertrain design through a systems engineering approach, focusing on fuel distribution and propulsion models. Their research identified a data gap in the development of hydrogen system models. Component models exist for sizing tanks, fuel lines, venting lines, Heat Exchanger (HX), valves, and hydrogen-burning engines [

9]. However, Multidisciplinary Design Analysis and Optimization (MDAO) models of complete hydrogen distribution systems remain unexplored. Their paper proposed design models for distribution and propulsion systems, including HXs that utilized conventional methods and relationships from [

10,

11,

12], which do not account for variations in hydrogen properties at cryogenic temperatures.

Cryogenic fluids have lower thermodynamic critical pressures than conventional fluids, leading to more frequent near-critical and supercritical convective heat transfer. At the critical point, the specific heat capacity and thermal expansion coefficient approach infinity, while other properties change dramatically with temperature and pressure fluctuations, complicating heat transfer and pressure drop correlations. Additionally, at temperatures below 123 K (−150 °C), materials exhibit complex thermophysical behaviors that deviate from the assumptions made at ambient temperatures [

13]. Nonlinear variations in transport properties invalidate the constant-property analysis typically used in heat transfer calculations, thereby affecting thermal conductivity, specific heat capacity, and viscosity.

HXs are the most critical component within the TMS, requiring a suitable modeling approach; several HXs are typically required and may require significant volume for installation. In addition, phase change might occur within the HX. Although conventional empirical relationships for HX design remain valid at cryogenic temperatures and can be used for rapid design evaluation during concept exploration, they can only be applied while accounting for four key challenges [

13]: variable material properties, thermal insulation requirements, near-critical-point convection, and radiation heat transfer.

To address these challenges, a different approach is required: either analyzing the HX in discrete segments, each with locally valid thermophysical properties, or carefully selecting representative mean physical properties. A segmented approach can enable designers to account for nonlinear variations in properties while maintaining computational efficiency, resulting in more accurate performance predictions and optimized designs for cryogenic heat-exchange applications. This paper presents a discretized parametric HX sizing method for aircraft distribution and propulsion systems utilizing LH

2 as fuel, such as those illustrated in

Figure 1, to address the non-linear thermophysical behaviors at cryogenic temperatures. The method accounts for the complexities of cryogenic systems and is specifically designed for implementation within a MDAO framework.

This paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 describes the methodology followed to parametrically size cryogenic HXs and outlines the design models employed.

Section 3 discusses the methodology validation by comparing it with existing conventional HX data and cryogenic HX literature.

Section 4 examines a cryogenic FC propulsion system case study, concurrently sizing and optimizing 4 HXs.

Section 5 concludes and outlines future work.

2. Methodology

This section presents the HX design methodology developed to incorporate the nuances of designing for cryogenic applications. This research aims to identify the key requirements for cryogenic TMS design and establish effective methods for sizing HXs within such systems. The desired outputs are the weight, physical dimensions, system losses, and energy requirements.

The governing equations for HX design are derived from fluid dynamics and heat transfer principles applicable to both conventional and cryogenic systems, as documented by Barron et al. [

13], Hesselgreaves et al. [

14], Ranganayakulu et al. [

15], and Kays and London [

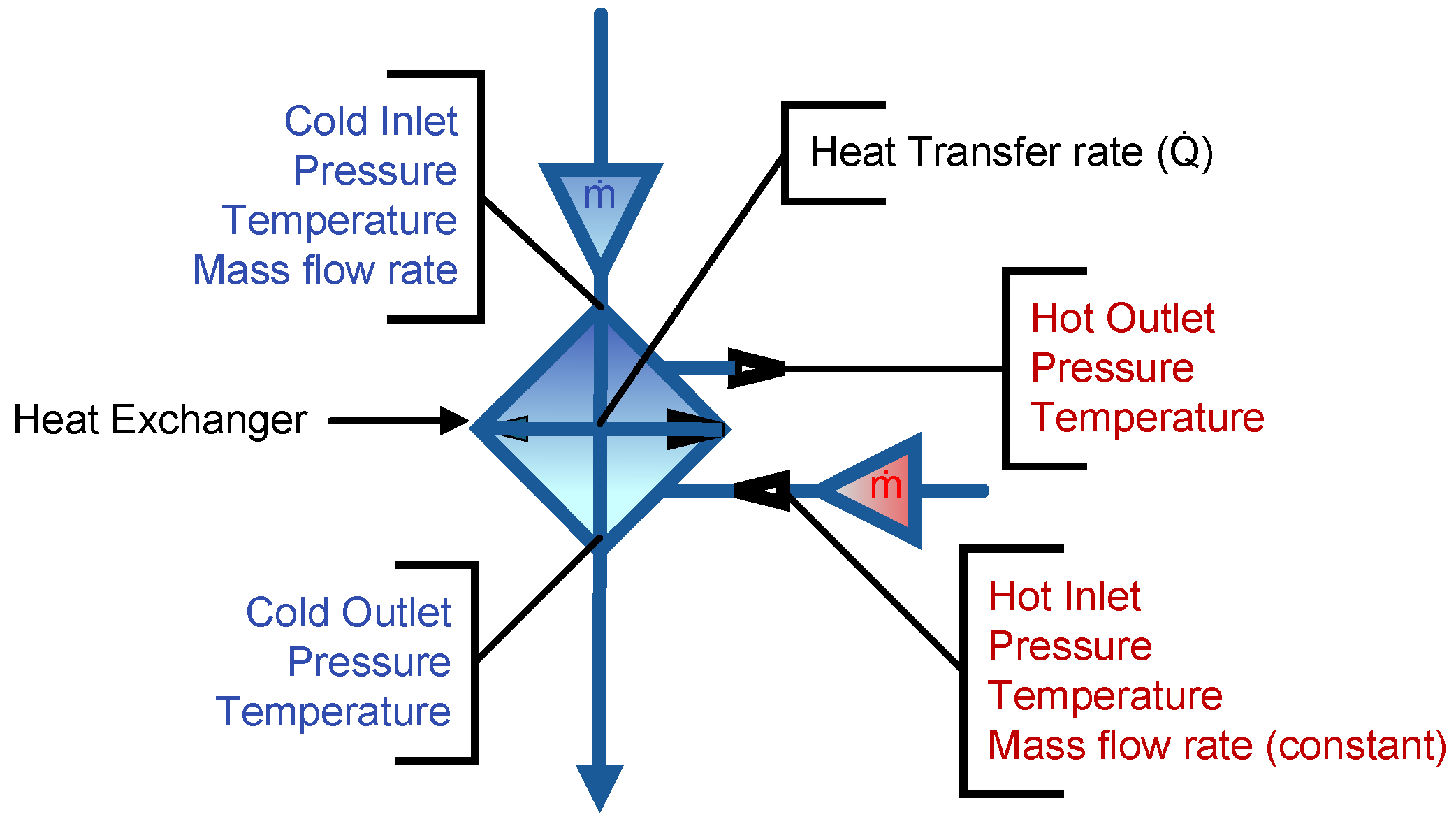

16]. These equations require input parameters, including heat transfer capacity (

Q) or heat transfer rate (

), mass flow rates (

), and inlet and outlet fluid properties.

To obtain a final design, specifications such as weight, size, system pressure limitations, and an overview of the proposed process’s different steps are required.

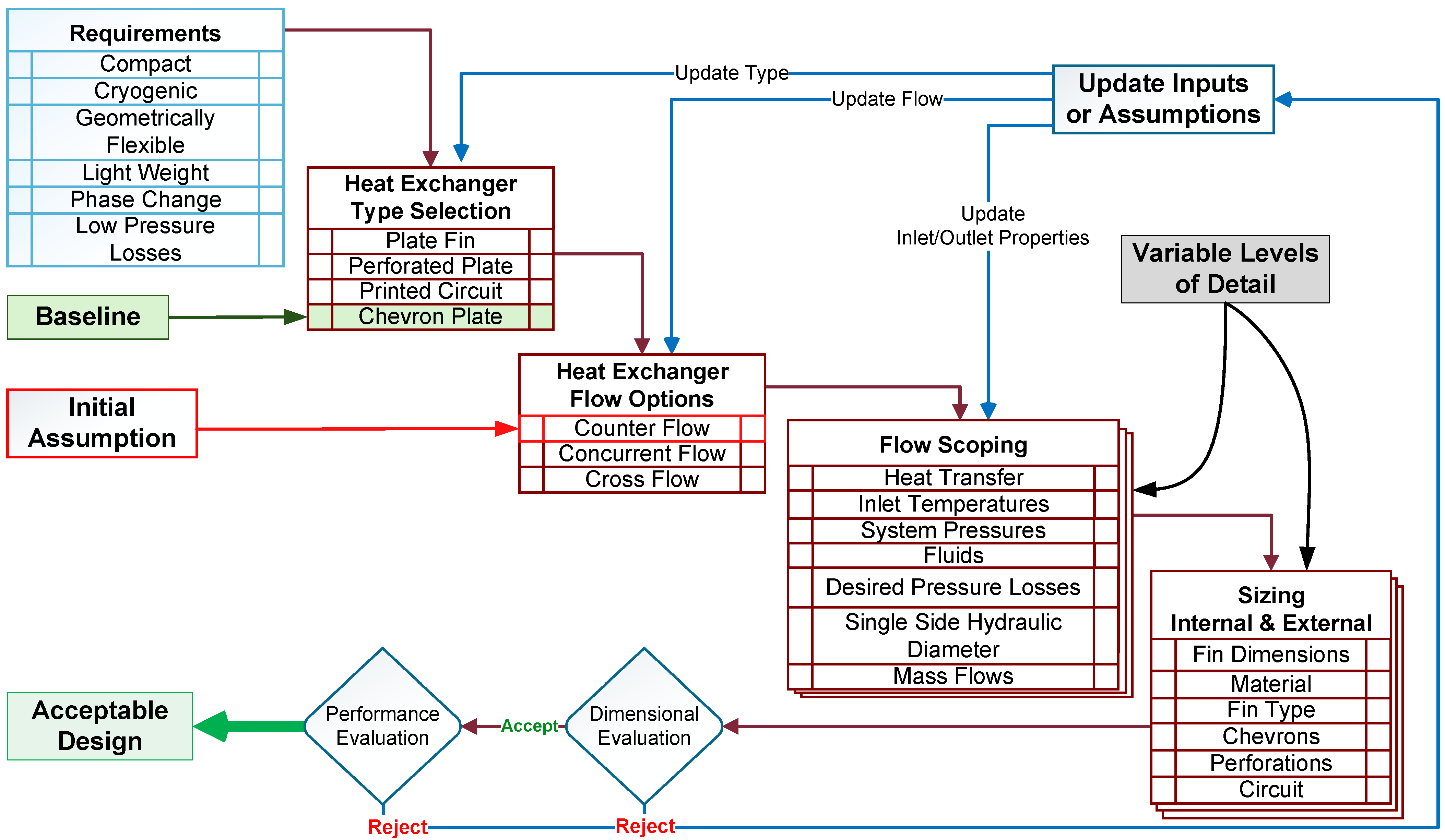

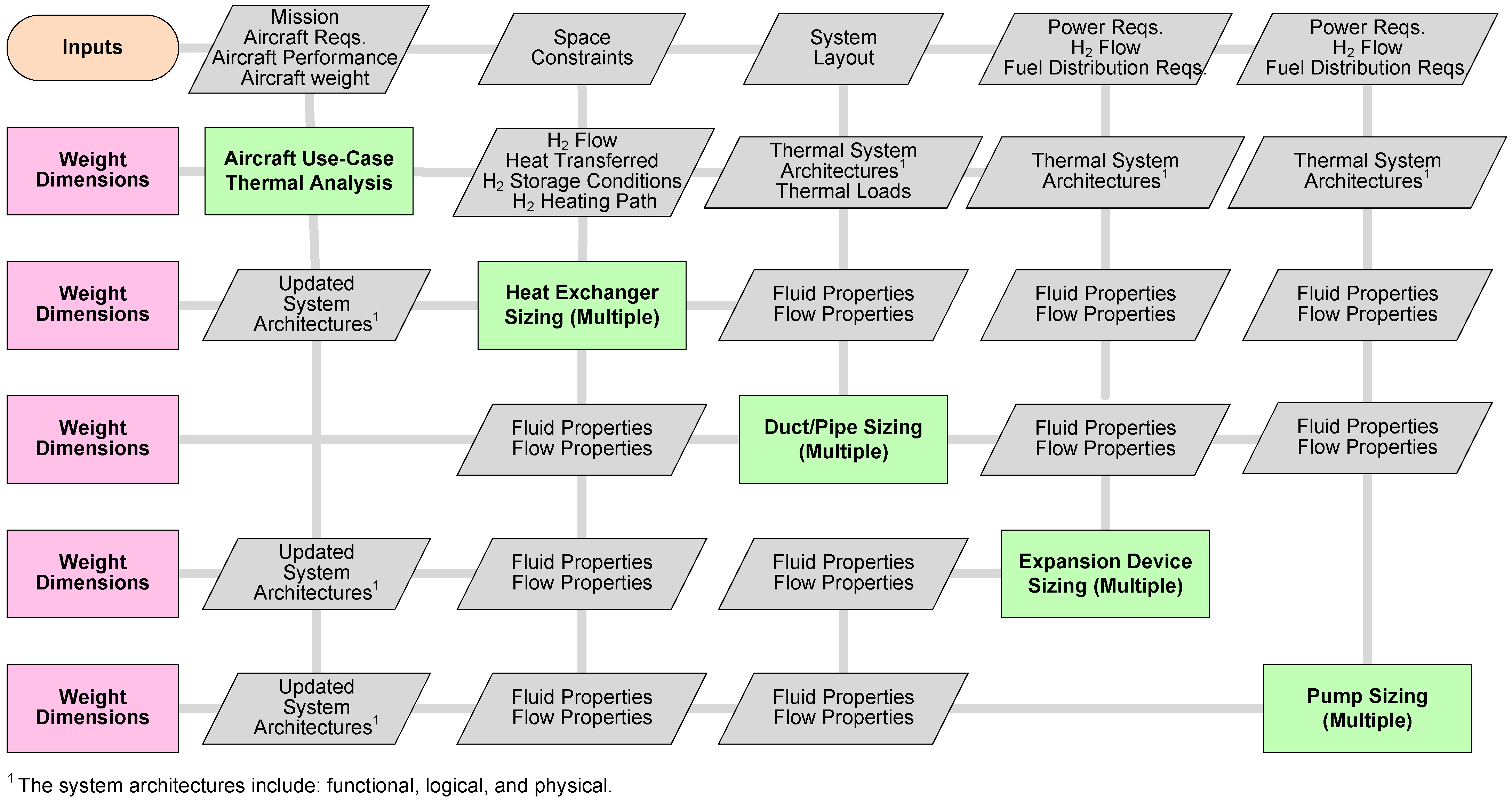

Figure 2 presents a flowchart that outlines the steps of the proposed process.

The methodology accommodates varying numbers of input parameters by applying different analytical approaches. Hence, conventional log-mean temperature difference or -NTU HX design methods are employed, although modified to account for fluid property variations. The selection between these approaches depends on the available inputs and computational efficiency, as the design is formulated as an optimization problem. This flexibility enables design-space exploration, allowing the identification of configurations that meet the interface conditions of the TMS architecture.

The iterative design process consists of six steps: requirements capture, type selection, flow selection, flow scoping, sizing and dimensional evaluation, and performance evaluation. This paper examines HX sizing for alternative propulsion systems, with particular attention to superconducting architectures.

The Corrugated Plate Heat Exchanger (CPHE) is selected as the baseline configuration due to its conservative design, reduced input parameter requirements, which facilitate computational efficiency in sizing plate HX systems, and its fewer parameters, which allow for quicker debugging during code development. The Plate-Fin Heat Exchanger (PFHE) is also a good solution for more viscous liquid-to-liquid fluids or when fouling might be a concern. A counterflow arrangement is initially assumed, as this configuration typically yields the most economical design [

14].

2.1. Parametric Specifications, Assumptions, and Constraints

Parametric specifications, assumptions, and constraints are classified into two distinct categories: framework-based and problem-based. In this context, “framework” refers to the systematic approach through which the methodology addresses a specific problem; for this paper’s case study, it is illustrated using the eXtended Design Structure Matrix (XDSM) diagram standard (as defined by Lambe and Martins [

17]) and shown in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4. Meanwhile, “problem” refers to the actual sizing task and its various inputs, as shown in

Figure 5.

Framework-based specifications are computational tool-related elements that enable the HX sizing process to communicate with other sizing tools. For instance, a MDAO framework might utilize the Common Parametric Aircraft Configuration Schema (CPACS) data definition to facilitate information exchange between tools [

18]. These specifications, assumptions, and constraints also define how the HX sizing process addresses a given problem, since multiple solution approaches exist depending on available parametric inputs. They also establish initial conditions for the iterative design process, incorporating standardized engineering parameters from established design tables and relationships.

For the HX design, it is necessary to define the system-level framework-based specifications and assumptions based on the system architecture, as shown in

Figure 4.

Similarly,

Figure 5 illustrates the various parametric problem-based inputs, outputs, specifications, assumptions, and constraints. The problem-based specifications, assumptions, and constraints define key operational parameters, such as temperature gradients between fluid streams, system operating pressures, maximum allowable pressure drops, heat transfer coefficients, and geometric constraints governing HX configurations. Once again, standard engineering design references such as Kays and London [

16] and Hesselgreaves [

14] provide validated baseline values for designer-specified assumptions.

Finally, the assumptions must encompass the entire feasibility range to explore the design space, while constraints maintain solution viability. When solutions prove infeasible or fail to meet specified requirements, two remediation approaches are available: (1) constraint relaxation or (2) assumption boundary expansion. These methodological modifications facilitate iterative refinement of the solution space until viable designs emerge. Initial broad input spaces typically yield feasible solutions; however, when no solution exists, analysis of the obtained solution space relative to the objective space guides the designer toward necessary trade-offs to achieve acceptable, though non-optimal, solutions.

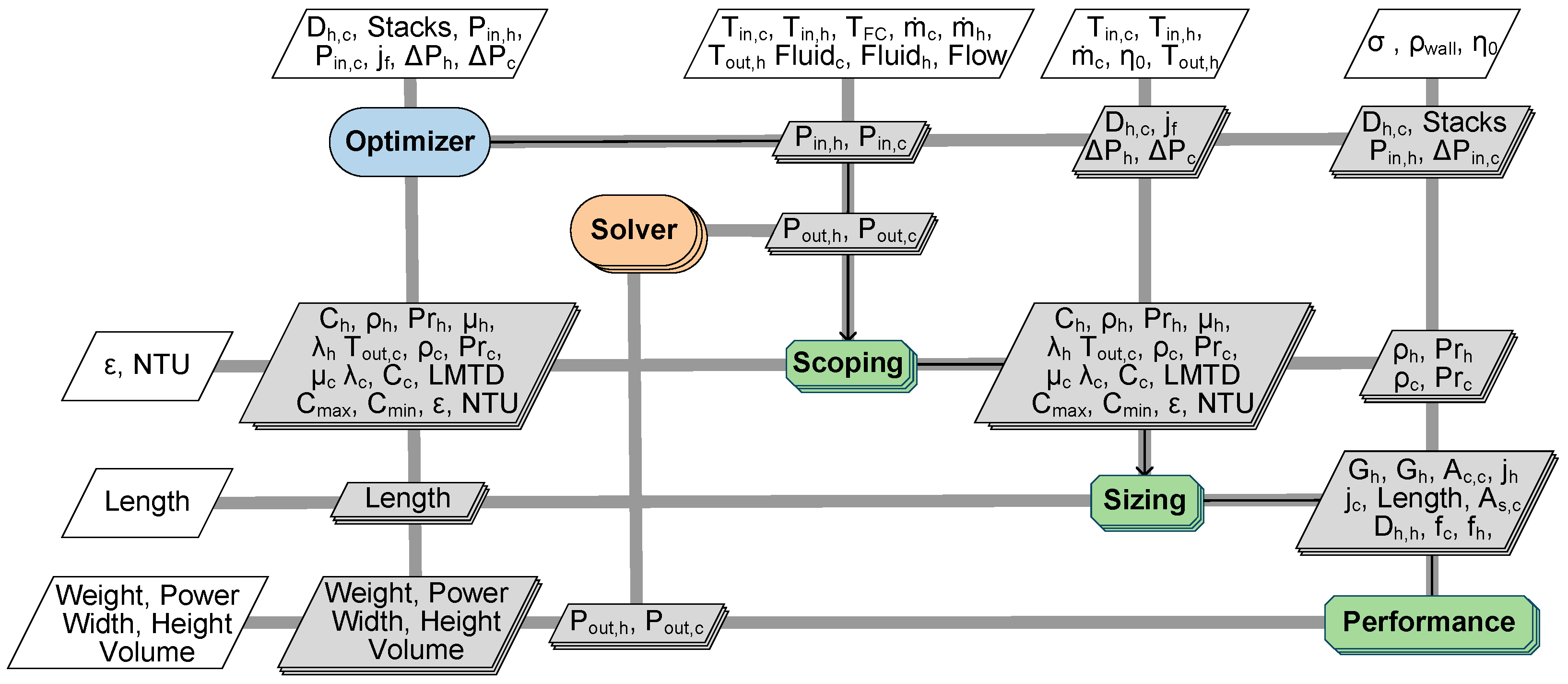

2.2. Scoping Process

The flow scoping analysis assumes the use of a thermophysical property library, such as CoolProp [

19], or the National Institute for Standards and Technology (NIST) database to evaluate the thermodynamic and transport properties of pure, pseudo-pure, and multi-component fluid mixtures. The process is illustrated in a XDSM diagram in

Figure 6, which shows that the system receives inputs from three distinct sources: system design specifications, optimizer variables, and solver feedback variables.

The scoping process applies the First Law of Thermodynamics to analyze each working fluid stream. It applies to both hot and cold sides of the HX, with Equation (

1) describing the energy balance for the cold stream. In this equation, the heat transfer rate (

) is calculated using the mass flow (

), the specific heat (

), and the inlet and outlet temperature values (

and

). The same equation can also be used with heat capacity rates (

C) instead of mass flow and specific heat, which can be calculated using Equation (

2).

For the hot side of the HX, an analogous equation applies with inverted temperature differentials, as presented in Equation (

3), and the heat capacity rate is calculated the same way as shown in Equation (

4).

The

-NTU method requires determining the minimum heat capacity rate

, which is set equal to the minimum between the hot- and cold-side rates. Then, using it to find the maximum heat transfer rate (

) and applying it to Equation (

6), the HX effectiveness can be calculated. This definition is the same as defined by the Society of Automotive Engineers in their Aerospace Recommended Practices [

20].

Then, the number of transfer units (

) is determined based on the selected flow configuration and the ratio of stream capacity rates as shown in Equation (

7). This ratio, denoted as

or

, is calculated according to Equation (

8). The number of transfer units is also related to the HX’s heat transfer conductance, which is the product of the overall heat transfer coefficient (

) and surface area (

A), and

, allowing for the sizing of the HX as shown in Equation (

9). This relationship is derived from the heat exchange Equation (

10), where

is the heat transfer coefficient and

is the surface effectiveness.

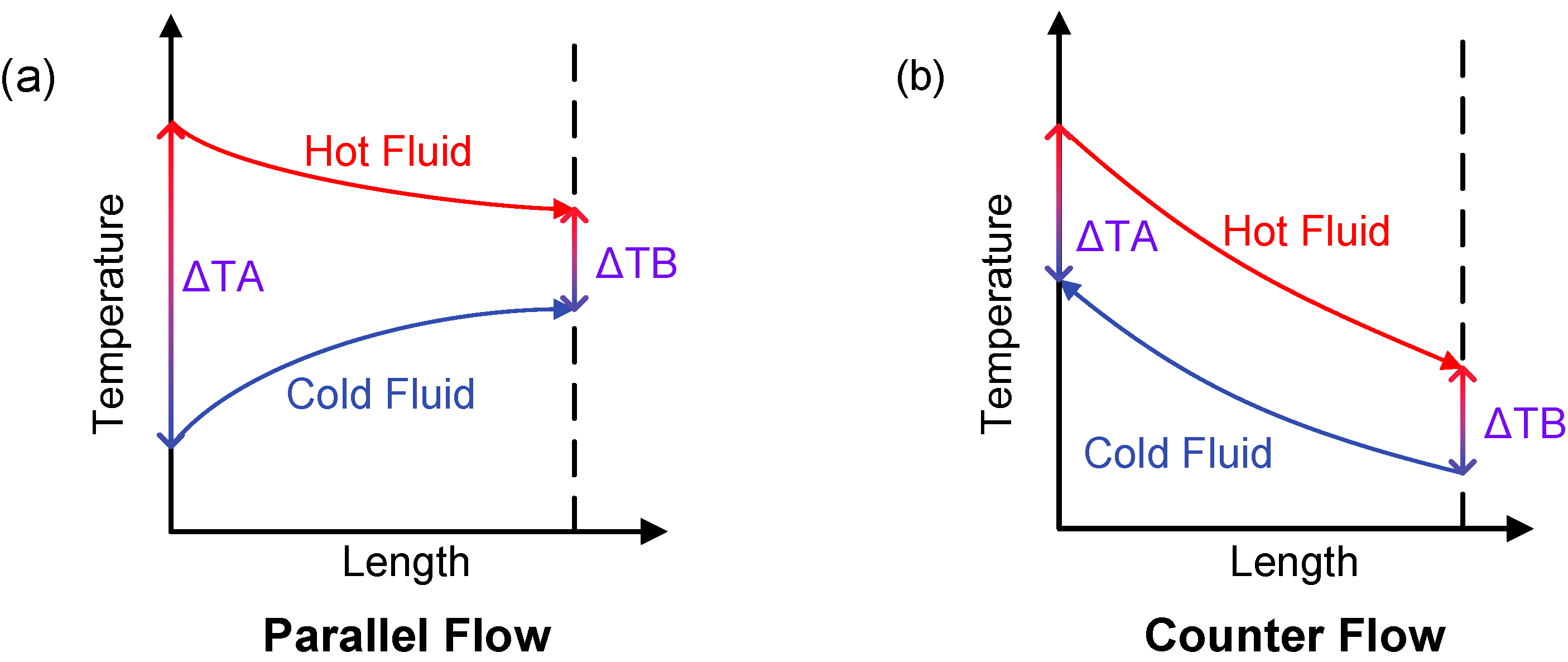

Alternatively, the log-mean temperature difference method can also be used. It assumes that heat transfer coefficients remain constant along both sides of the HX, which may not always be the case, depending on the design. However, for conceptual evaluation purposes, this simplification is adequate. The relationship for calculating it is shown in Equation (

11), where

and

are flow-dependent and are calculated according to

Figure 7.

Both methods rely on the inlet and outlet temperatures of the HX and conventionally use average fluid properties between these points, assuming near-constant or near-linear variation in fluid properties. This assumption does not hold for materials at cryogenic temperatures or when fluids operate near their critical point. Specific heat () is one such property, as it depends on the material state (solid, liquid, or gaseous). Different heat transfer mechanisms dominate the heat transfer process depending on the state.

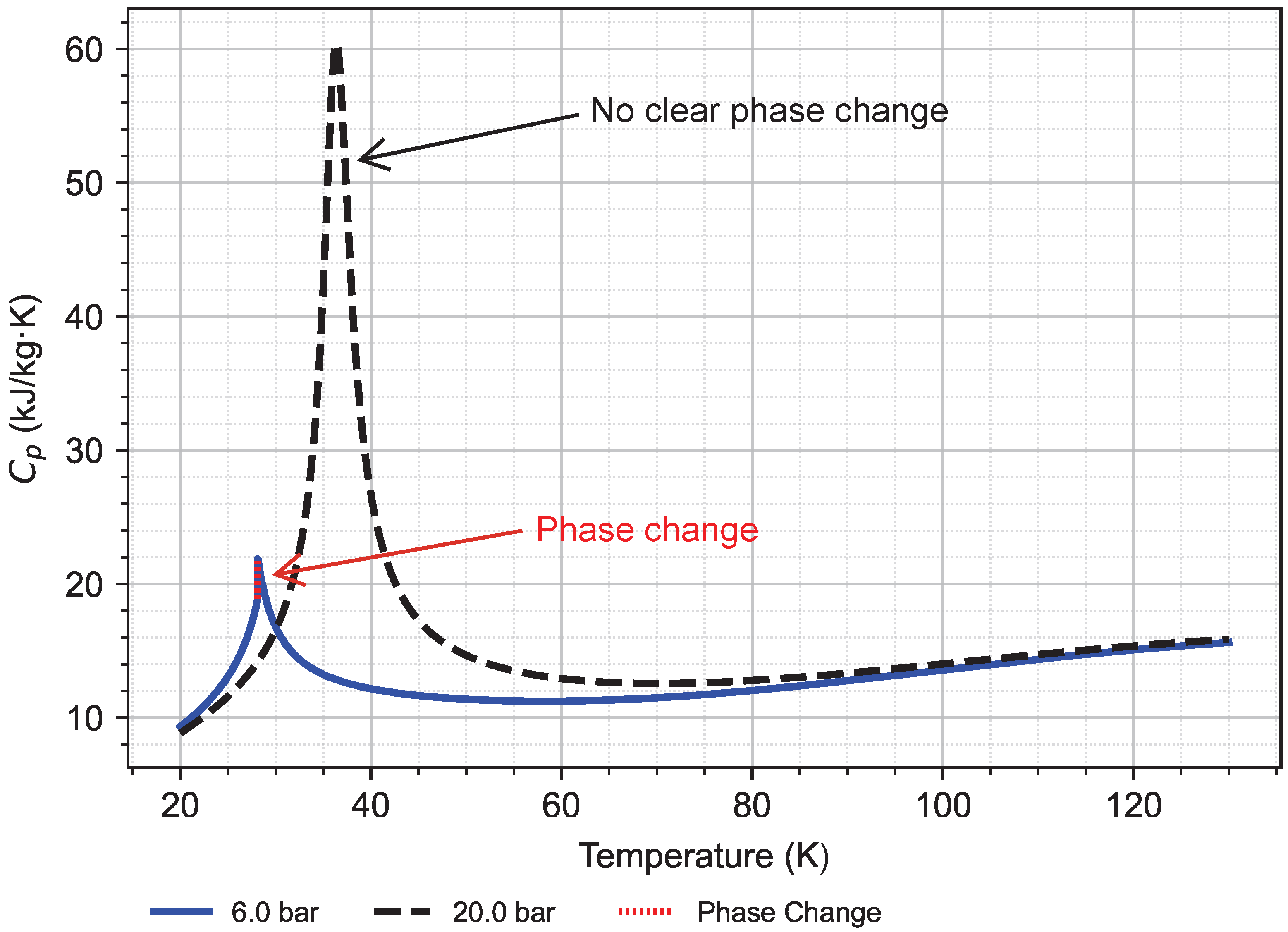

For example, comparing the properties of LH

2 at 6 and 20 bar yields the graph shown in

Figure 8, which illustrates significant variations in specific heat across the cryogenic temperature range at constant pressure. This demonstrates that conventional assumptions cannot be applied universally, as their validity depends on the particular temperature range being examined.

This non-linear behavior necessitates a different approach: either analyzing the HX in discrete segments, each with locally valid thermophysical properties, or carefully selecting representative mean physical properties. These approaches can enable designers to account for the non-linear property variations while maintaining computational efficiency, resulting in more accurate performance predictions and optimized designs for cryogenic HX applications.

2.2.1. Temperature Calculation

A key function in sizing plate-type HXs is calculating a fluid’s outlet temperature based on mass flow and energy transfer using the convection equation, as shown in Equations (

1) and (

3), or, more generally, in Equation (

12).

With a known mass flow and heat transfer rate, we can calculate the outlet temperature by rearranging Equation (

12) to solve for the outlet temperature, as shown in Equation (

13).

This calculation is straightforward and requires only a few parameters. However, as discussed in

Section 1, cryogenic applications cannot use simple average specific heat values for these calculations. Therefore, the chosen implementation employs a discrete numerical method instead, as illustrated in Algorithm 1 for heating without phase change. Since specific heat values vary with temperature at each calculation step, a “while” loop continues until the desired heat transfer is achieved using increments that ensure accurate application of Equation (

12). The precision can be adjusted based on both the region of interest and the desired accuracy level by modifying the parameter

n.

The described method offers an advantage over Equation (

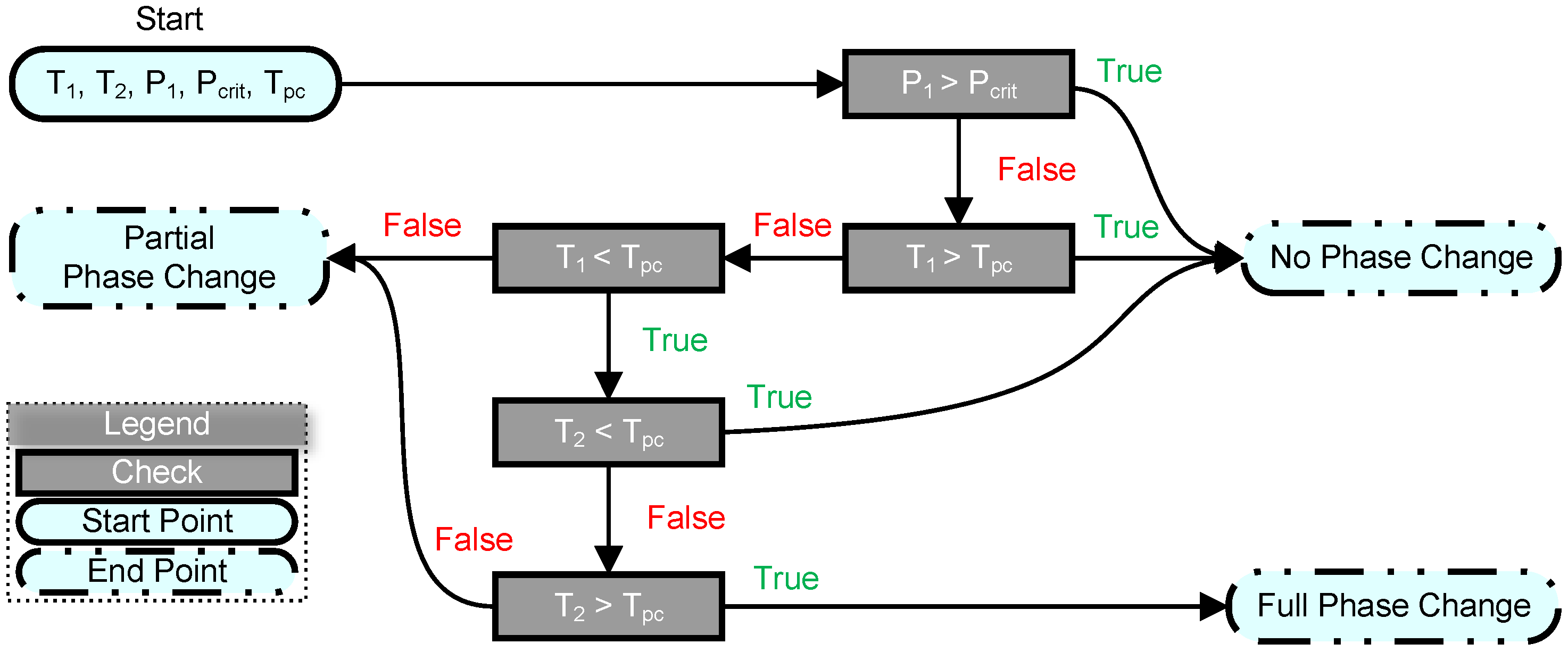

13) by enabling a simple conditional check before calculations begin. In contrast, the alternative approach would require verifying phase changes after calculations are complete, which would increase computational time for a single sizing process and even more so for an optimization process, where the code runs multiple times.

Figure 9 illustrates the logical process for phase change verification. Two scenarios are possible: full phase change or partial phase change. For partial phase changes, conventional linearization methods are applied, and an additional parameter, the exit quality (

), is determined. This parameter is defined as the ratio of the mass flow rate of vapor (

) to the total mass flow rate (

) and calculated according to Equation (

14).

![Aerospace 13 00142 i001 Aerospace 13 00142 i001]()

For cooling, the principles remain the same, with only minor changes to the code needed to account for the sign difference when calculating the temperature variation (

) in Equation (

12).

Figure 9.

Logical process to verify whether there is a phase change during heating.

Figure 9.

Logical process to verify whether there is a phase change during heating.

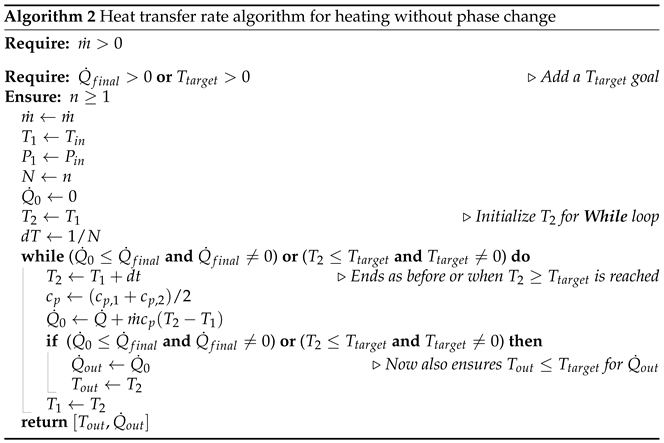

2.2.2. Heat Transfer Rate

Another key function calculates the heat transfer rate based on mass flow and temperature change when these parameters are fixed. Advantageously, the logic and implementation from the temperature calculation can be repurposed, as the heat transfer rate () is already produced as an output parameter of that function, as evidenced in the returned array from Algorithm 1. The updated implementation primarily adds new conditions to the “while” and “if” statements, as shown in Algorithm 2, which highlights only the modifications.

![Aerospace 13 00142 i002 Aerospace 13 00142 i002]()

This enhancement provides several advantages:

Minimizes code duplication;

Allows the algorithm to work with both the desired heat transfer rate and temperature limit; and

Ensures the sizing process prevents solidification in cooling applications.

In cases of phase change, either boiling or condensation, Lee [

21] states that within an evaporator or condenser, the heat transfer rate is the product of the mass flow rate (

) and the latent heat of vaporization or condensation (

), as shown in Equation (

15). In the event of partial phase change during boiling, the result from Equation (

15) can be multiplied by the quality at the outlet (

). As for condensation, the result must be multiplied by one minus the outlet quality (

).

2.2.3. Mass Flow

The mass flow calculation function employs a similar approach to the heat transfer calculation, incorporating new conditions into existing algorithms to enhance computational efficiency. It should be noted that for any sizing problem, as long as two of the three parameters (outlet temperature, heat transfer rate, and mass flow) are known and the initial conditions are established, this method can scope the flow based on the discretization approach used.

2.3. Sizing Process

The sizing method is the same as outlined in [

14], which uses the dimensionless thermal length (

N) to determine the core mass velocity (

G) for each side, as given by Equation (

16).

This equation demonstrates that fluid density (

) and the Prandtl number (

) are required to determine the HX size for a given flow regime. The pressure drop (

) is defined as a design parameter, and the j factor (

) can be initially assumed to be

(according to [

14]) and iteratively updated based on the Colburn factor (

j) and Fanning friction factor (

) later on.

As discussed, conventional assumptions for fluid properties do not adequately represent H

2 systems at cryogenic temperatures. However, conventional relationships remain valid [

13], and their application is feasible when the fluid properties used for calculations accurately represent the given fluids and flows.

The suggested approach is to discretize fluid properties over the relevant temperature and pressure ranges to ensure accurate sizing. An alternative approach is to specify a particular geometry, as suggested by [

22,

23], in which a distributed-parameter method is used instead.

The methodology presented herein explores the design space without directly specifying a geometry; instead, geometrical relationships are employed. This approach is adopted because geometrical information remains limited during the conceptual and early preliminary stages of aircraft design, and the design process at these stages focuses on feasibility assessment rather than detailed design.

The relationships used for the calculation of the Colburn factor (

j) and the Fanning friction factor (

) (not to be mistaken with the Darcy–Weisbach friction factor (

), which is 4 times larger than the Fanning friction factor) are shown in

Table 1 for CPHE and

Table 2 for PFHE.

Table 1.

Relationships for the calculation of the Colburn and Fanning friction factors for CPHE.

Table 1.

Relationships for the calculation of the Colburn and Fanning friction factors for CPHE.

| Corrugated Plate Heat Exchanger Relationships |

|---|

| Variable | Equation |

| Colburn factor (j) | |

| Fanning friction factor () | |

For PFHE, the preferred relationships use the non-dimensional parameters

,

, and

as described by Equations (

21) and (

23). For cases where a more geometric approach is desired, Equations (

22) and (

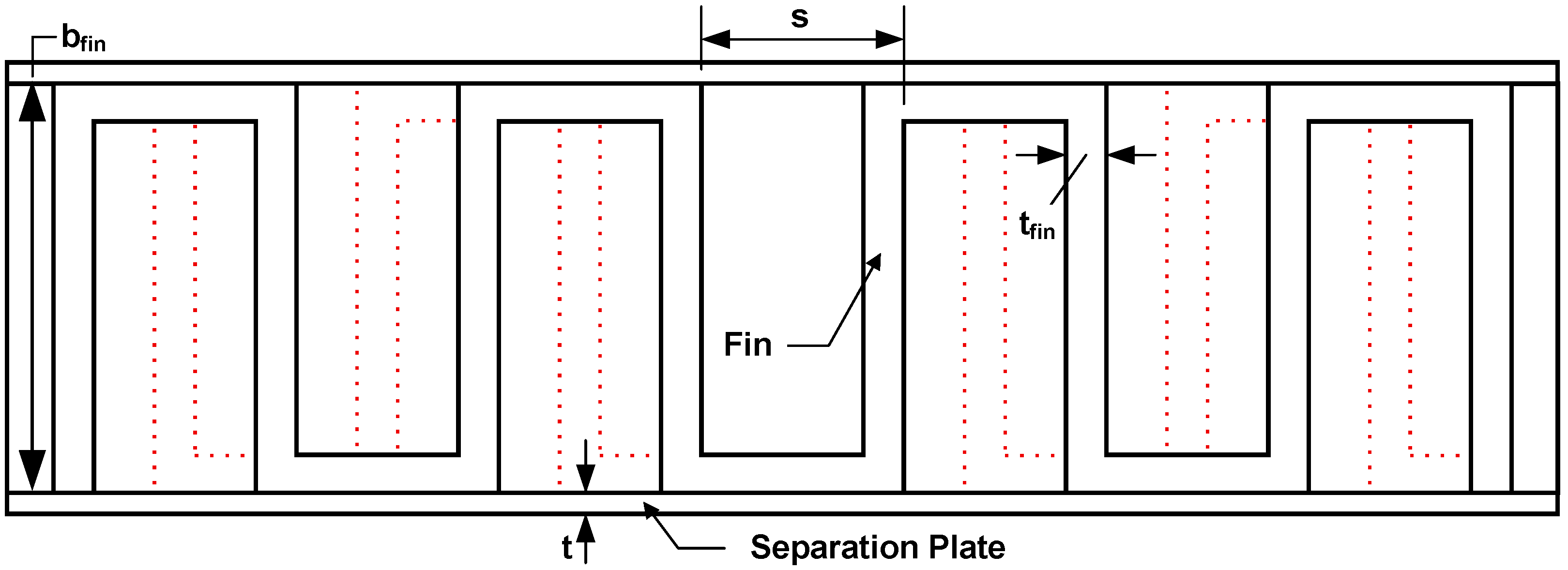

24) can be used instead. This allows for design space exploration based on the Offset-Strip Fin (OSF) parameters described in

Table 3 and shown in

Figure 10. These relationships are also valid for plain fins by setting the fin strip length equal to the HX’s length.

Table 2.

Relationships for the calculation of the Colburn and Fanning friction factors for PFHE.

Table 2.

Relationships for the calculation of the Colburn and Fanning friction factors for PFHE.

| Plate-Fin Heat Exchanger Relationships |

|---|

| Variable | Equation |

| Colburn factor (j) | |

| Fanning friction factor () | |

Finally, the process is iterated upon, starting from Equation (

16) until convergence or a set number of iterations. For the first sizing process, since the fluid properties do not account for pressure losses that can impact results, it is possible to use a looser initial convergence tolerance or fewer iterations to reduce processing time.

2.4. Performance Evaluation

The HX design process concludes with a performance evaluation based on dimensional properties, weight, and pressure losses. While pressure losses are typically inputs, the non-critical side requires calculation. The evaluation sequence begins with the calculation of the Nusselt number. For CPHE, the experimental correlations by Sekulic and Shah [

24] are used, as shown in Equation (

25).

For PFHEs, the Nusselt number calculation is flow-dependent, and therefore Equation (

26) must be used with the help of the geometric relationship shown in

Figure 11 for the value of

.

The calculation proceeds with determining actual thermal lengths using flow properties, superseding previous temperature-based estimations from Equation (

16) solved for

N. The non-critical side’s thermal length is expected to vary from previous estimates, as the exchanger is optimized for the critical side’s flow. Pressure drop calculations validate input parameters or provide values when unspecified, following Equation (

27). The final geometric dimensions for volume and weight proceed using Equations (

28) and (

29), which account for the estimated exchanger porosity (

) usually in the range of 0.7–0.85 for compact HXs [

14]. For PFHEs, the porosity can be calculated using Equation (

30) based on the dimensions from

Table 3.

System pressures represent an important design parameter subject to optimization. These pressures determine the mean thermophysical fluid properties based on the inlet and outlet temperatures during heat transfer processes. Although pressure losses occur within HXs, the constant pressure assumption for fluid properties can provide acceptable accuracy for low heat transfer rates. For high-heat-transfer-rate applications, such as those in aircraft propulsion systems, an iterative analytical approach is necessary. Additionally, for future hydrogen-fueled aircraft, cryogenic hydrogen exhibits high compressibility in both gaseous and liquid states, resulting in large variations in thermophysical properties between the HX inlet and outlet conditions. The described methodology employs an iterative approach that begins with a constant-pressure analysis and progressively incorporates estimated pressure losses in subsequent iterations until computational convergence is achieved.

2.5. Thermodynamic Transfer Properties

The determination of thermodynamic transfer properties constitutes a critical function that enables the aforementioned calculations. Various libraries are available for this purpose, including prominent commercial solutions such as the Reference Fluid Thermodynamic and Transport Properties Database developed by NIST, which must be used with a calculation software. While these commercial options provide comprehensive databases, an open-source alternative was selected for this implementation. The methodology therefore uses the CoolProp thermophysical property library [

19]. Nearly all fluids in CoolProp use the explicit Helmholtz-energy equation of state to calculate thermodynamic properties. In selecting the library, two fluids were a deciding factor in choosing CoolProp: parahydrogen and helium.

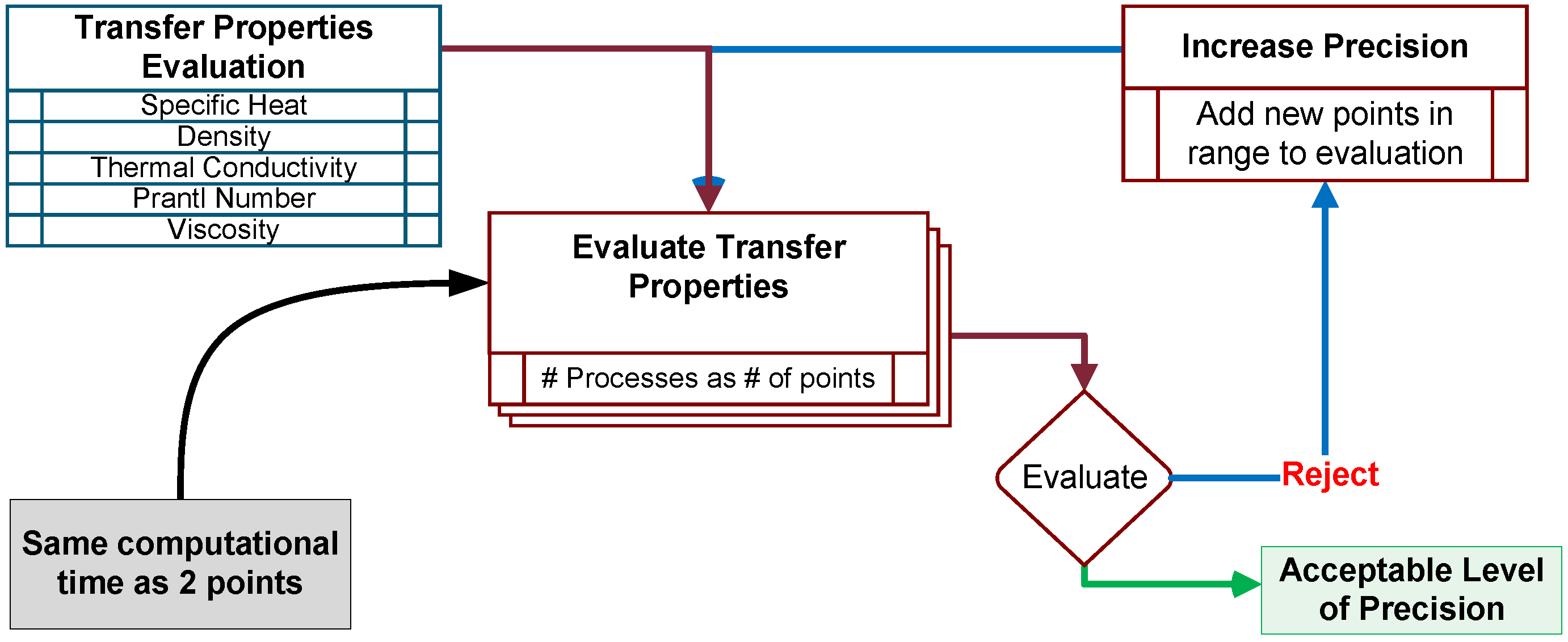

Accurate calculation of fluid transport properties is essential for the methodology; however, determining appropriate discretization presents a challenge. The process illustrated in

Figure 12 functions as a structured approach to establishing optimal problem discretization by quantifying the number of discrete points required to achieve the specified precision threshold. Error tolerances can be established at multiple levels: property calculations, temperature determination, heat transfer rates, and mass flow rates. Additionally, the implementation leverages modern computational capabilities through multiprocessing techniques, enabling researchers and designers alike to optimize computational efficiency based on available hardware resources.

2.6. Solver Selection and Optimization Set-Up

The selection of solvers and optimization algorithms represents a critical consideration in developing an automated sizing methodology. As discussed previously, the sizing process involves an equation system containing linear, non-linear, and discrete equations that require appropriate solving techniques. The implementation developed employs the Python 3.10.14 programming language, which provides access to numerous solvers and optimization packages. Open-source packages such as OpenMDAO [

25] and Pymoo [

26] are selected specifically for their robust computational frameworks and optimization algorithms.

A direct solver utilizing Jacobian LU factorization with back substitution addresses linear equations, while a nonlinear block Gauss–Seidel solver handles nonlinear equations through hierarchical iteration. Thus, when Newtonian direct solvers prove inadequate, an iterative approach is implemented for its

Capacity to efficiently balance computational resources and precision for large systems, thereby enabling appropriate precision levels for each computational task;

Superior convergence rate compared to Jacobi methods through utilization of the most recently calculated values within each iteration, whereas Jacobi methods rely solely on values from previous iterations;

Reduced memory requirements for large systems compared to Newton’s method, which necessitates storage of Jacobian matrices, particularly valuable when working with discretized HX models that may have thousands of variables; and

Enhanced convergence performance over Newton’s method for systems demonstrating strong diagonal dominance, where each variable’s update is predominantly influenced by its corresponding equation with minimal impact from other equations.

The optimization process employs a genetic algorithm, which explores complex multi-modal design spaces without requiring gradient information, making it suitable for HX. These types of problems typically involve multiple competing objectives, for example, minimizing pressure drop while maximizing heat transfer, numerous constraints, and discrete variables, including fin configurations or tube arrangements.

Genetic algorithms can efficiently navigate these complex design spaces by working with populations of potential solutions that evolve through selection, crossover, and mutation operations. They are particularly valuable when the design space contains discontinuities, as is the current case, or when analytical derivatives are unavailable.

The implementation provides a modular framework specifically designed for multi-objective optimization that natively handles mixed variables (continuous, integer, binary, and categorical) and features specialized algorithms for many-objective problems (with more than three objectives). Furthermore, an advanced diversity-preservation method using M-Nearest Neighbors (MNN) rank and a crowding-survival strategy is employed [

27] to enhance computational efficiency.

3. Validation

This section presents a validation of the HX sizing methodology through a comparative analysis against two distinct reference cases, for both conventional (at standard operating temperatures) and cryogenic applications. The first validation case examines an industrial HX from Bell & Gossett (a brazed plate HX) [

28] operating under standard conditions, while the second investigates a 2 K helium HX designed for extreme cryogenic environments, with data taken from a study by Zhu et al. [

22]. These cases establish the robustness of the methodology across diverse operating regimes and provide a quantitative assessment of the algorithm’s accuracy in predicting HX performance. The validation process incorporates both dimensional analysis and performance metrics to verify the computational approach against established industry standards and published research.

3.1. Validation Case 1: Conventional Hydronic System Brazed Plate Heat Exchanger

The specifications obtained from the manufacturer’s documentation are presented in

Table 4. The Bell & Gossetc (made by Xylem Inc., IL, USA) BP400-40 [

28] is selected as a validation example due to its industry-standard design parameters and the availability of documentation.

Although the HX is well documented, certain critical parameters, such as the chevron specifications, porosity, surface effectiveness, and hydraulic diameter, are not available in the manufacturer’s documentation. However, by analyzing multiple photographic references of the HX, it was possible to estimate the angle to be around 70°; however, assumptions were made based on the literature and estimations for the other parameters.

The parameters, serving as input variables for validation, along with all the assumptions, are summarized in

Table 5.

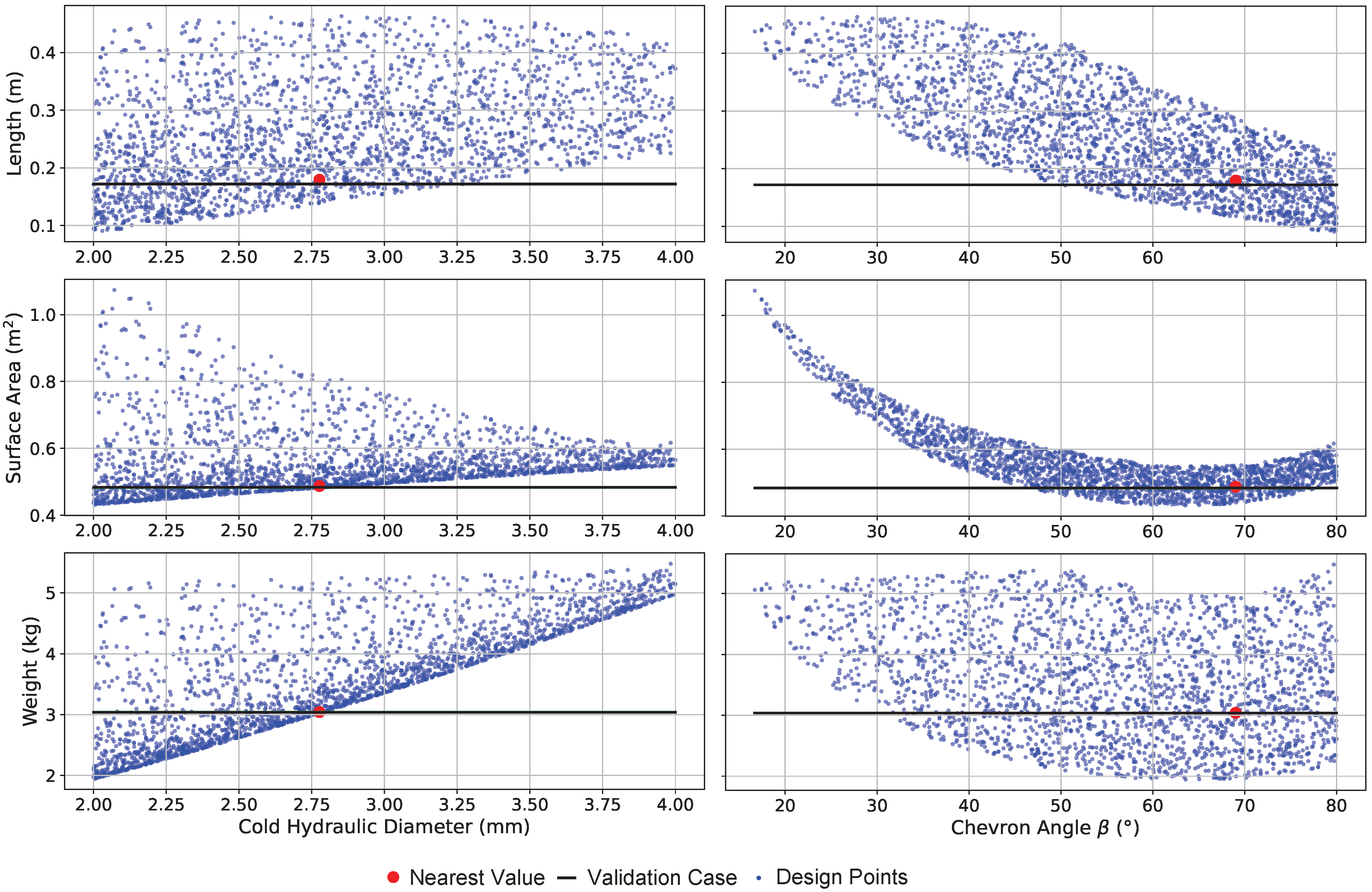

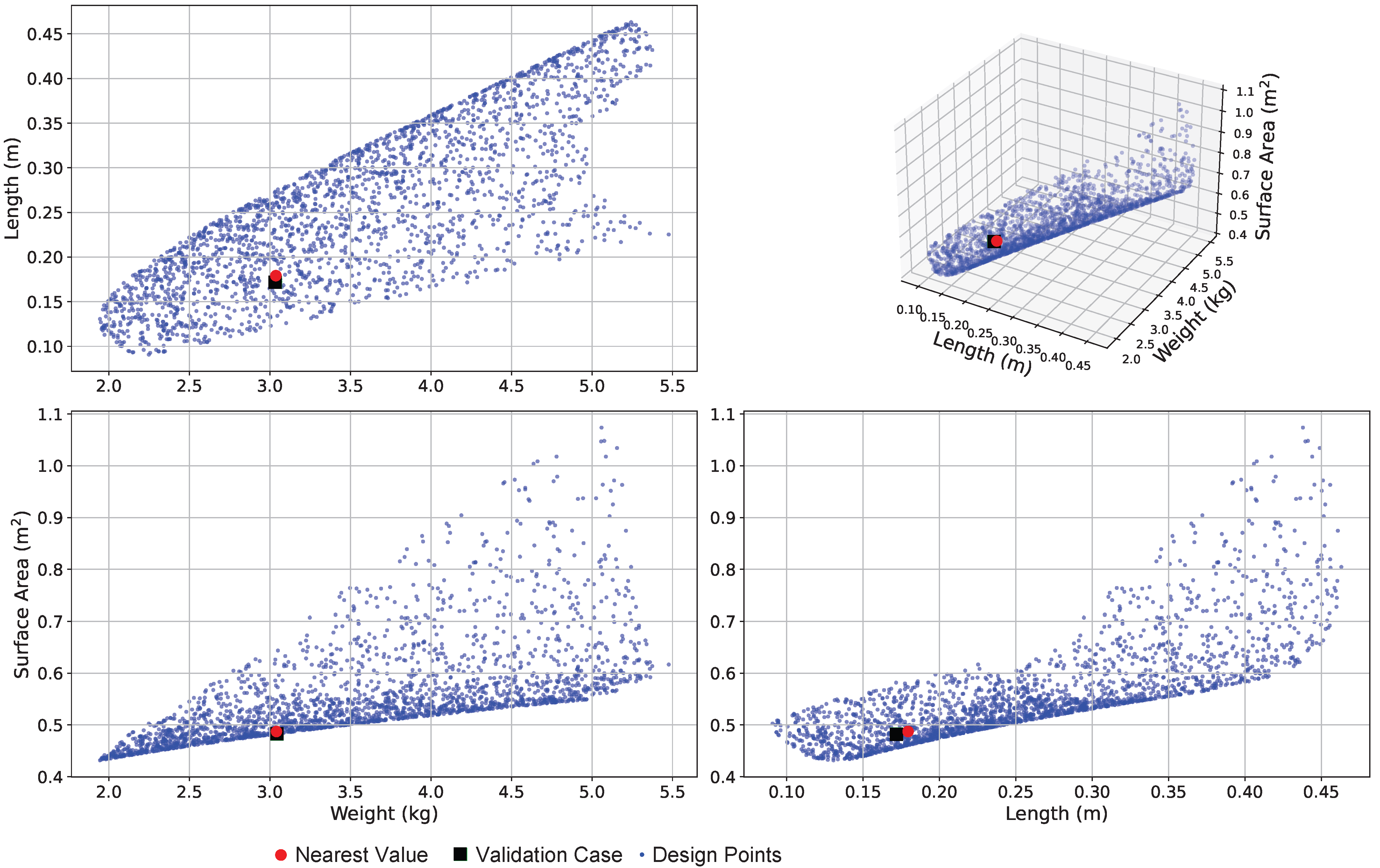

Figure 13 demonstrates the successful positioning of the Bell & Gossett BP400-40 within the design space, denoted by a green indicator line and a red dot marking the closest found result. The chevron angle parameter varies from 10° to 80° in the analysis. This methodological approach addresses the inherent challenges in precisely determining critical HX properties, particularly the chevron angle and hydraulic diameter.

The cold-side hydraulic diameter is a primary input parameter and has a significant influence on the three validation metrics: length, heat transfer surface area, and weight. Operating conditions include a design pressure of 30 bar, with pressure losses conforming to domestic heating specifications. As mentioned previously, the chevron angle was estimated to be 70°, which aligns with the results shown in

Figure 13. In the same vein,

Figure 14 shows the objective space, with the actual validation case dimensions displayed in green and the nearest computed value shown in red (the two nearly overlap). Although exact replication of the reference case was not the primary goal of this design-of-experiments study, the results confirm that the solution falls within the defined objective space, thereby validating the methodology.

3.2. Validation Case 2: Cryogenic Helium Plate-Fin Heat Exchanger

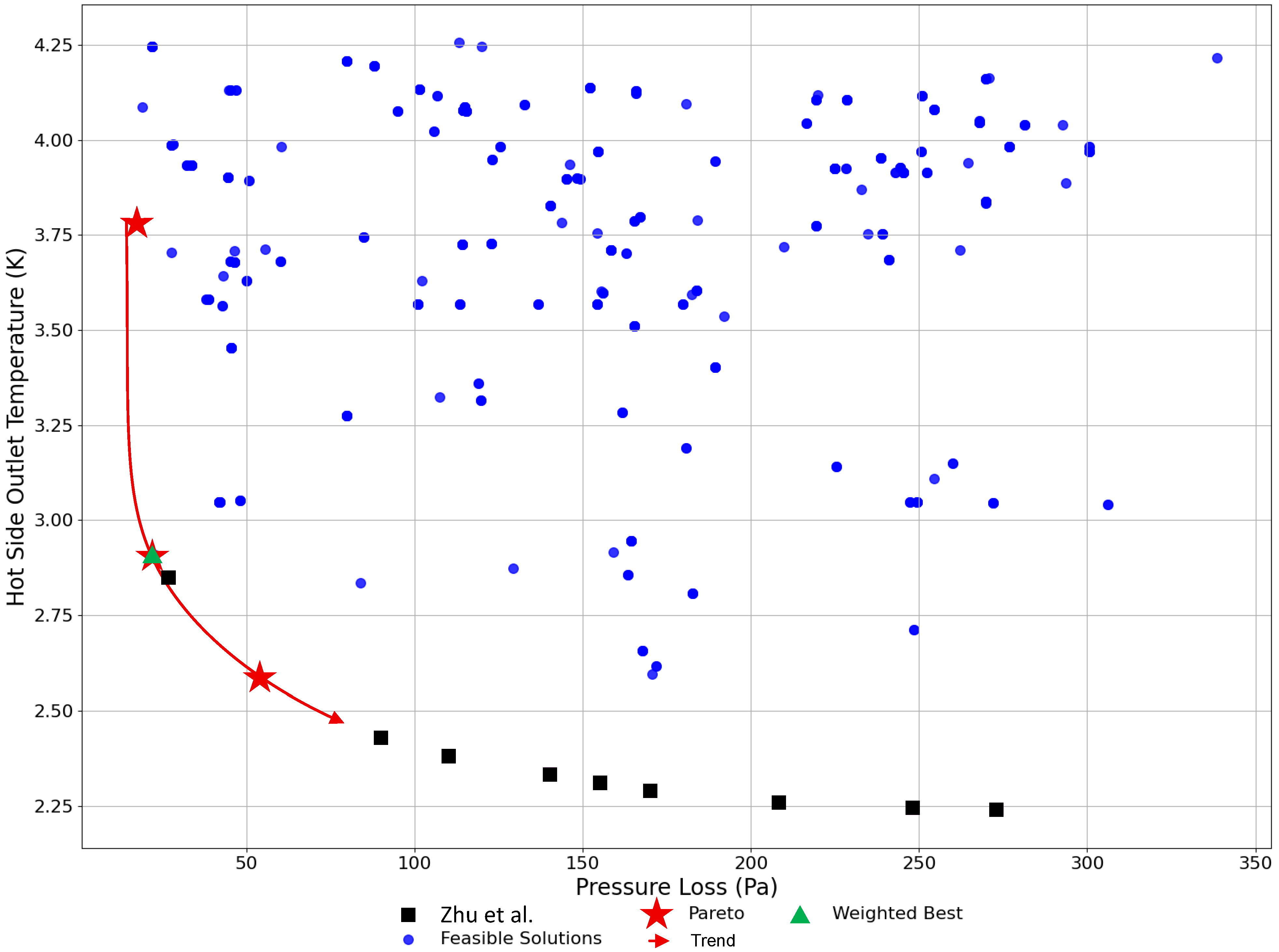

The second validation case addresses cryogenic applications by examining an advanced superconducting accelerator component operating with a helium flow rate of 5–12.5 g/s. The reference study employed a distributed-parameter method for design calculations, dividing the HX into small segments to accurately model temperature and pressure variations at cryogenic conditions. The researchers employed the Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II to generate Pareto-front solutions that optimize outlet temperature and pressure drop.

Their experimental results validated the computational approach, showing outlet temperatures within 6% of design calculations and achieving 82.4% heat transfer efficiency. This case study provides an excellent validation benchmark for cryogenic applications where helium’s large property variations near absolute zero pose unique thermal management design challenges.

As adjustments were necessary due to methodological differences, the search parameters highlighted in

Table 6 are slightly different from those presented in [

22]. As discussed in

Section 2.3, the implementation primarily uses the non-dimensional parameters

,

, and

, which are defined in

Table 3. Consequently, the given parameters were first converted into their non-dimensional equivalents, shown in

Table 7, and then applied as constraints.

For the properties of helium at extremely low temperatures, specialized functions were required. Missing CoolProp data points were interpolated from graphs provided in [

22], as the original data were not publicly available. Aluminum material properties were obtained from NIST standardized equations [

29].

In reality, the design space for the discussed implementation is broader, as it aims to identify the optimal design rather than working with a specific PFHE cross-section. This approach aligns with the aerospace industry’s philosophy of custom-designing for specific aircraft requirements, necessitating a unique design for each application [

30,

31].

For validation, the implementation requires 10 distinct constraints on the parameters highlighted in

Table 6. The identification of an exact solution with a 0.4 mm fin thickness requires preliminary calculations based on the dimensionless parameters. To initialize the algorithm, the fin thickness (

) and HX length (

L) are used. Since there is a single set of fins, the length of the HX is the strip fin length (

l) in Equation (

31). Fin height (

h) and fin spacing (

s) parameters are calculated according to the equations in

Table 7, and subsequently utilized to determine the hydraulic diameter (

) according to Equation (

31).

Figure 15 displays the validation results. The slight difference in Pareto front trends may be attributed to the fact that their results were extracted from a Figure rather than from raw data, and to the unknown baseline surface effectiveness (

). Additionally, the thesis methodology employs correlations specific to plain rectangular fins, whereas the validation case utilizes perforated rectangular fins; therefore, Equation (

24) from

Section 2.4 has an added 20% penalty applied to the calculation of the friction factors as suggested by [

14].

To truly compare the results, a second sizing was performed using constraints based on the selected HX from the case study, and the same sizing tool was used to calculate the results. The results showed that for the same HX size, a pressure drop of 28.7 Pa was observed, compared to 26.7 Pa in the validation case, resulting in an error of 7.5%.

It is necessary to acknowledge that the divergence between the two methodologies stems partially from the absence of banking factors and layering effects in the current methodology, which is due to differences in their intended applications. While the validation methodology aims to closely approximate exact results for a specific design, the implemented approach focuses on preliminary design assessment. Also, the use of the advanced diversity-preservation method using MNN rank and a crowding-survival strategy changes the convergence path when compared to the validation case, which used standard Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II (NSGA-II) strategies. This is why

Figure 15 does not explore the lower-right portion of the graph as extensively.

The methodology suggested is designed for aircraft scoping applications, prioritizing early design feasibility assessment over detailed engineering specifications. Consequently, the algorithm generates conservative results that provide a reliable foundation for subsequent detailed engineering analysis.

3.3. Validation Summary

The validation results demonstrate the efficacy of the developed methodology, validating its capacity to model and optimize HX performance across diverse operating conditions. The computational approach successfully predicts thermal–hydraulic behavior in both conventional and cryogenic applications. With the 2 K helium HX validation, the methodology demonstrates convergence to solutions comparable to those reported in the literature, with performance metrics having less than 6.7% error.

4. Fuel Cell Propulsion System Case Studies

This section applies the HX sizing methodology and computational tool developed in previous sections to conceptual case studies relevant to novel aircraft propulsion systems.

The section examines multiple applications with varying thermal loads, fluid properties, and design constraints. Each case study follows a structured approach, as follows: first, defining the specific thermal management challenge; second, applying the parametric sizing methodology to develop potential solutions; and finally, analyzing the results to extract design insights.

The analysis begins with an overview of design parameters, assumptions, and the cryogenic propulsion thermal management architecture derived from the Hartmann et al. [

7] case, along with established component temperature requirements. This is followed by an evaluation of the H

2 fuel heating pathway. Subsequently, the analysis concludes with HX sizing calculations that conform to the dimensional constraints of business jet aircraft.

4.1. Overview

The TMS sizing investigation considers a business jet aircraft with a maximum power requirement specification of 7.6 MW [

32], corresponding to performance characteristics similar to those of the Bombardier Challenger 300 aircraft [

33], as shown in

Table 8.

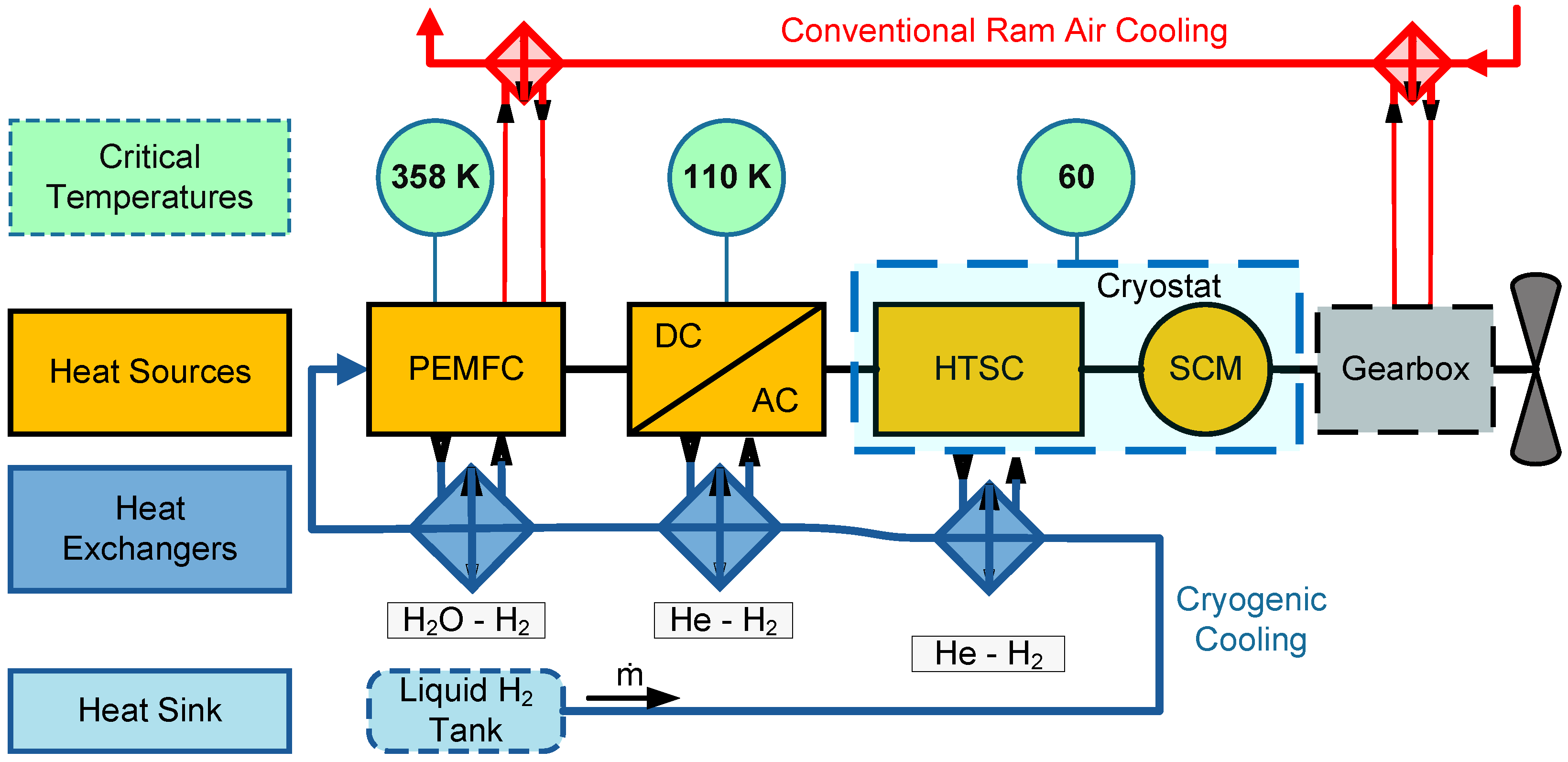

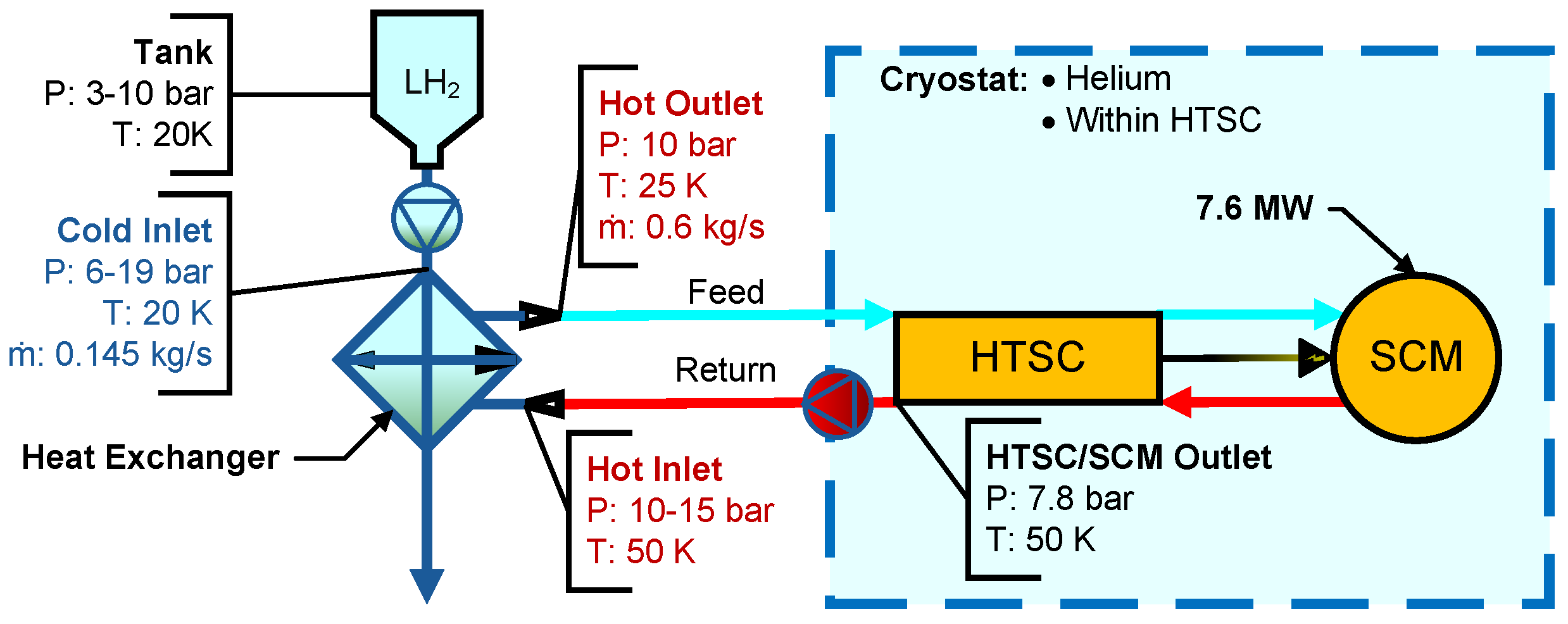

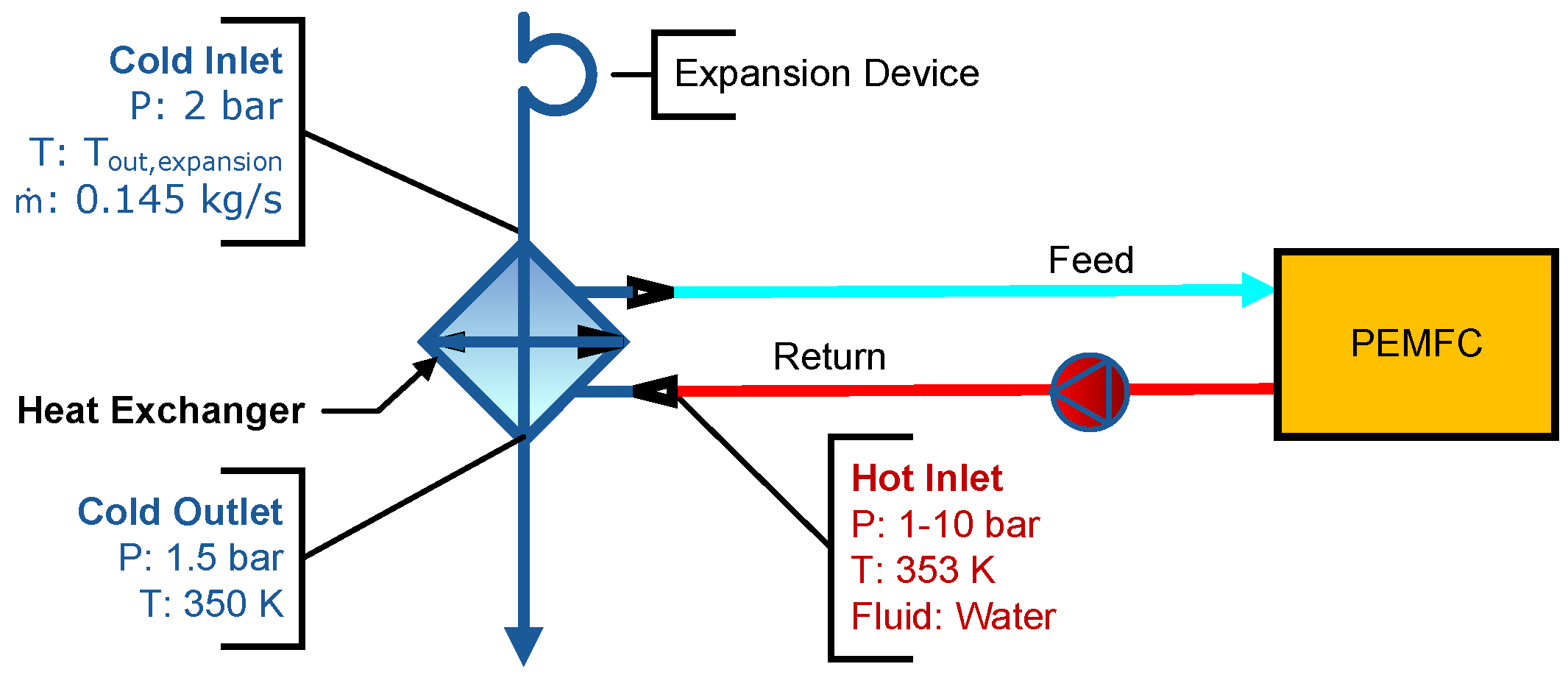

The architecture under investigation, shown in

Figure 16 and highlighted earlier in

Figure 1, consists of a Proton-Exchange Membrane Fuel Cell (PEMFC), High-Temperature

Superconducting Cables (HTSC), a DC/AC converter, a Superconducting Motor (SCM), a gearbox, and a propeller. Component losses are treated as heat losses and are calculated using Equation (

32), where

represents the power required downstream from each component and

denotes the component efficiency.

The propulsion system efficiencies derive from established ranges as documented by Hartmann et al. [

7] and presented in

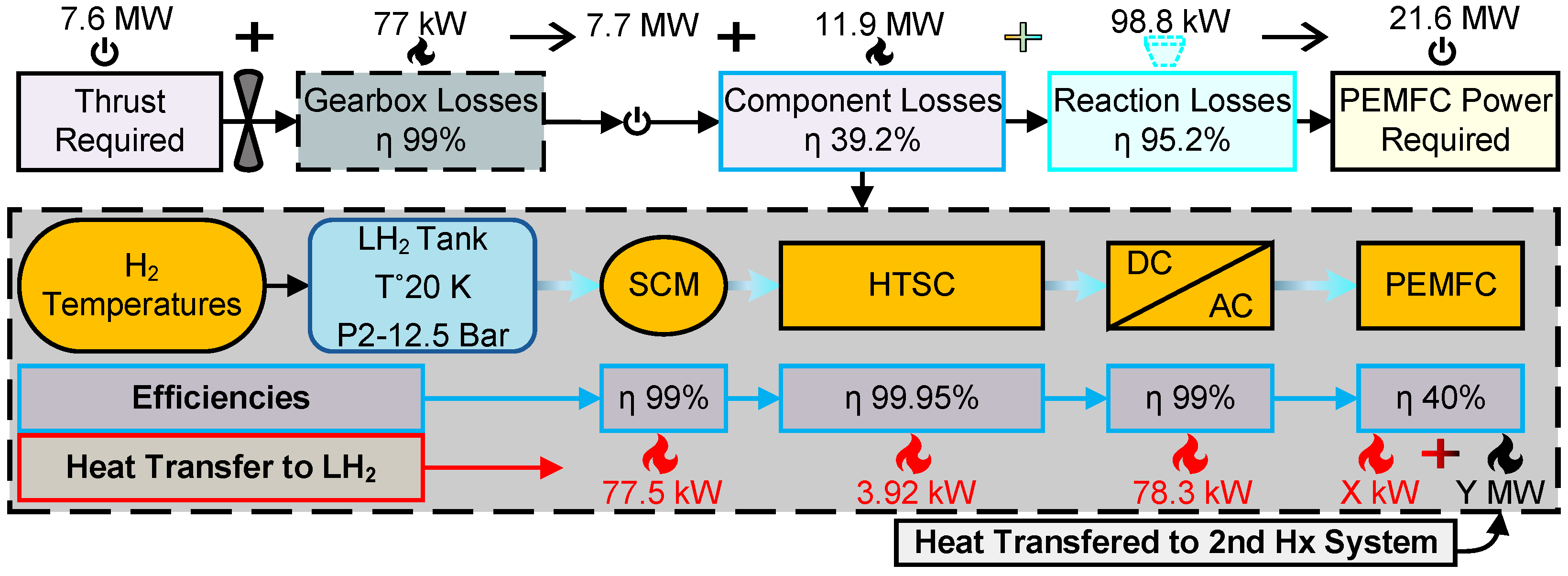

Table 9. A significant architectural modification in the case study involves eliminating the DC/DC converter in favor of a single DC/AC converter implementation. This modification enhances system efficiency by reducing weight, decreasing complexity, and optimizing component spacing. Quantitative analysis of the system, considering the maximum power requirement of 7.6 MW, the established component efficiencies, and reaction losses, indicates that the total required H

2 energy is 21.6 MW. Therefore, the mass flow calculations for H

2 are based on this number.

Figure 17 shows the distribution of heat losses across components, grouped by component efficiency. As the FC’s cooling requirements exceed the H

2’s cooling capacity, and the H

2 cooling potential is dependent on fluid properties and operating conditions, it is necessary to specify the initial H

2 storage conditions before determining the total H

2 heating required. The system requires thermal energy to elevate the H

2 temperature to the FC inlet condition of 358 K, while excess thermal energy transfers to a conventional ram air HX along with the gearbox heat losses.

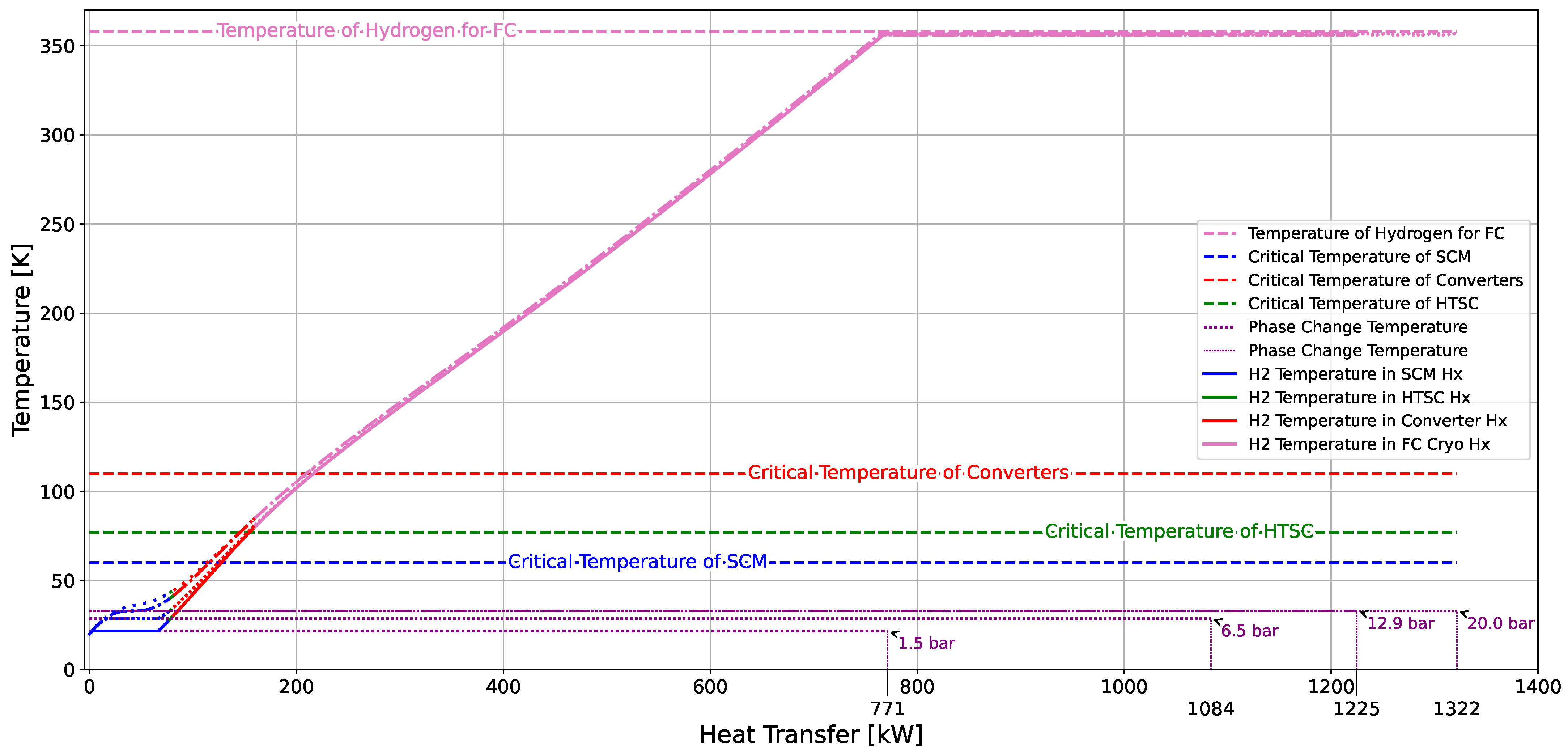

4.2. Hydrogen Heating Path

The utilization of H

2 fuel as a cryogenic coolant requires careful consideration of the fluid’s thermal pathway in relation to the critical temperature thresholds of each propulsion system component, as illustrated in

Figure 16. The heat transfer sequence starts at the SCM and HTSC cryostat, then at the DC/AC converter, and concludes at the PEMFC, thereby achieving the requisite reaction temperature and pressure for optimal system performance. Given the high variability of H

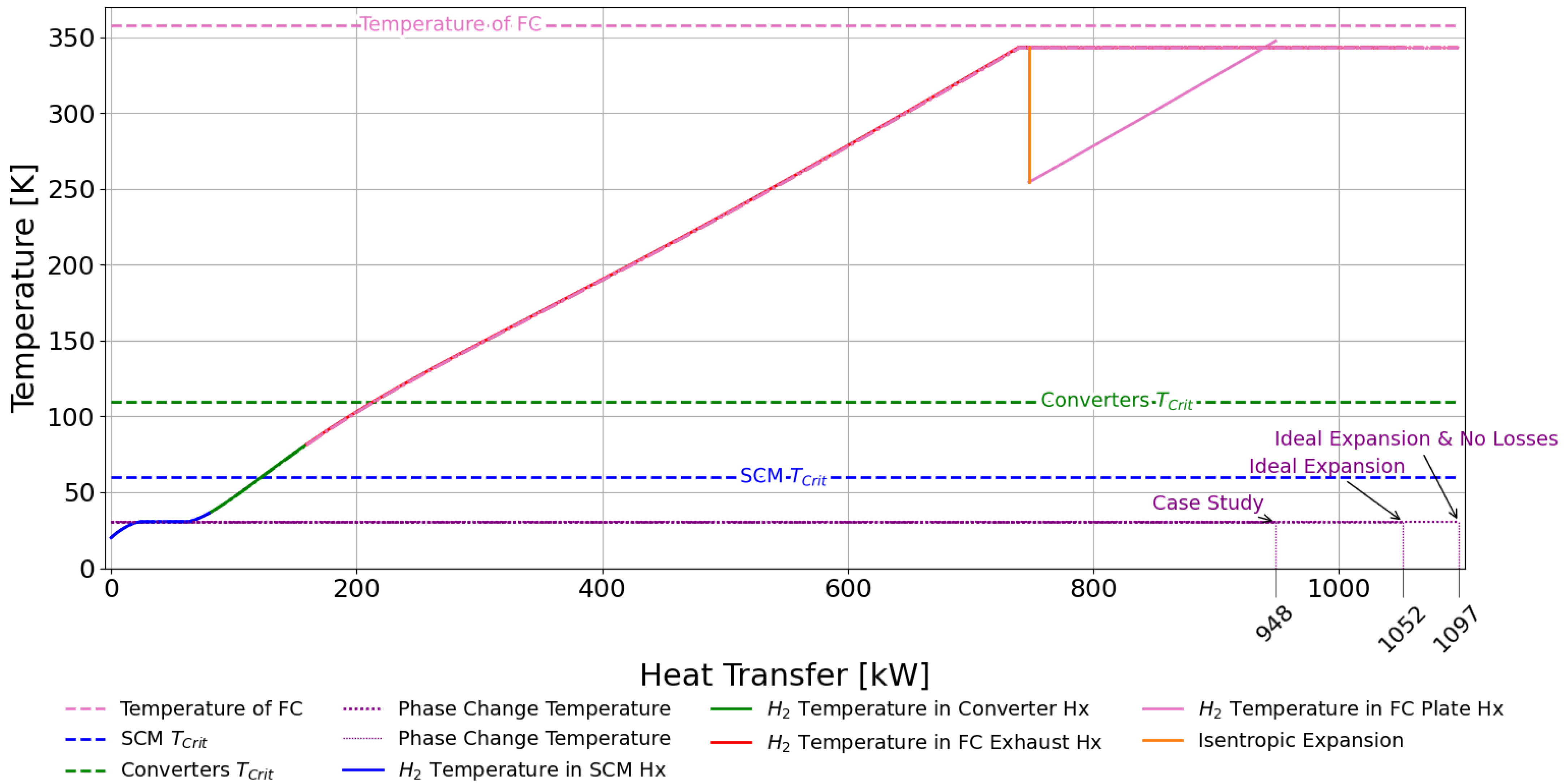

2 properties at cryogenic temperatures in both the liquid and gaseous states, a fuel heating curve must be calculated for each set of conditions inside the tank.

Figure 18 presents four cases examining tank temperatures of 20 K across pressures ranging from 1.5 to 20 bar. The analysis demonstrates that latent heat decreases at higher pressures due to proximity to H

2’s critical pressure point of 12.9 bar. While the constant-temperature characteristic of latent heat during phase change offers advantages in HX size reduction through two-phase fluid behavior, system-level benefits may favor higher pressures to utilize expansion cooling potential. This study implements an isothermal expansion device to demonstrate the need for parametric sizing models for TMS rather than expansion device optimization.

The H

2 heating curve analysis presented in

Figure 18 neglects pressure losses across HXs. This simplified analysis demonstrates the critical importance of heating path characterization and validates the need for parametric sizing tools to accurately model these TMS. While this idealization facilitates initial system characterization, practical applications necessitate incorporating these losses to achieve sufficiently accurate performance predictions.

4.3. Heat Exchanger Sizing

The investigation employs a multi-objective optimization framework across the HX network to simultaneously minimize system mass, Helium (He)-side inlet pressure, and H

2-side pressure losses.

Table 10 presents the common initial assumptions employed in this analysis. Additionally, to maintain focus on the HXs, all pumps, lines, and expansion devices are modeled with no losses.

4.3.1. Powertrain Interfacing Heat Exchanger

The first sizing process addresses specific requirements for the SCM and HTSC cryostat environment.

Figure 19 presents the interfacing components and corresponding sizing specifications. The hot side operates on a dependent cryogenic loop, with specifications provided by the electric motor design team from the Electric Propulsion Aircraft Project. The hot-side working fluid, mass flow rate, outlet conditions, and inlet temperature are fixed parameters, while the inlet pressure is a design variable. The cold-side operating conditions are governed by the initial storage conditions for fluid temperature, with an ideal pump facilitating the required pressure increase. The H

2 mass flow rate is fixed according to the PEMFC’s maximum power demand. The design space encompasses six more design variables: H

2 inlet pressure, hydraulic diameter, number of plates, pressure loss ratios for both fluid streams, and chevron angle.

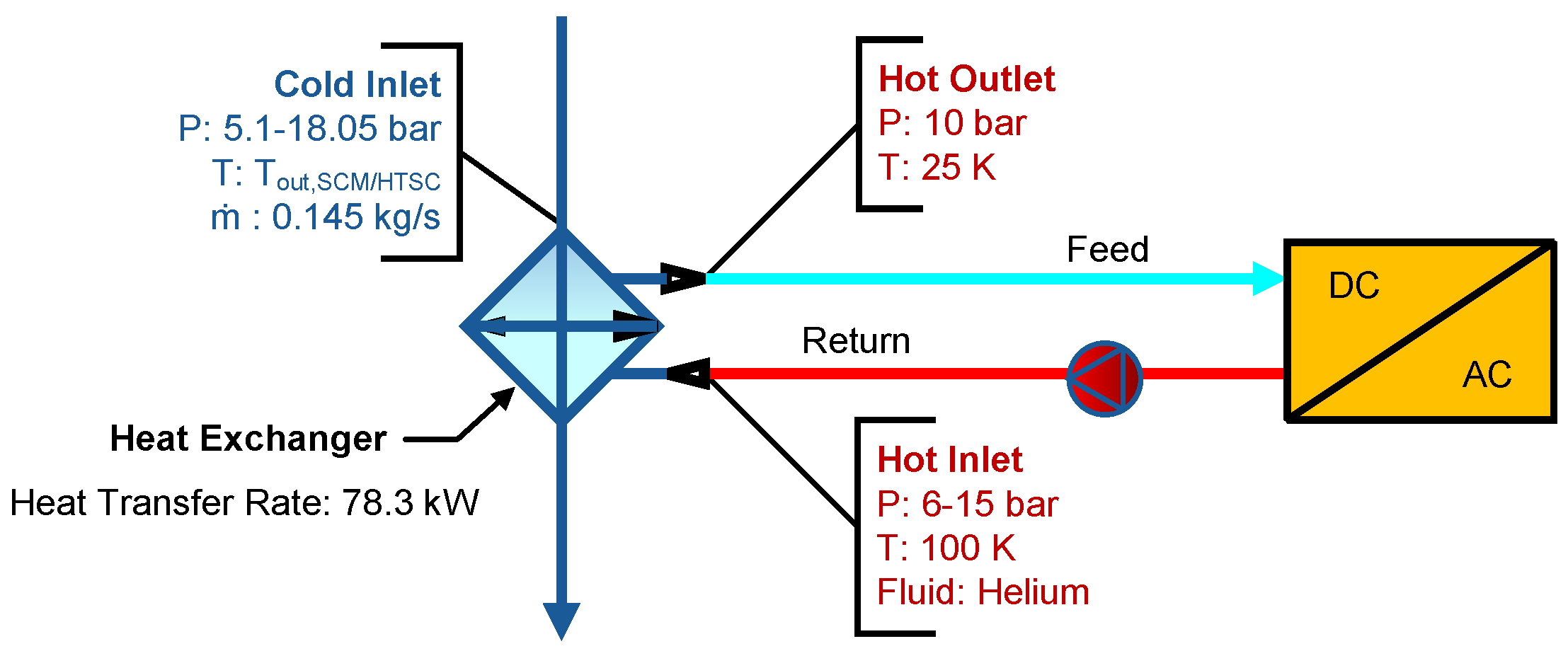

4.3.2. Electric Converter Heat Exchanger

The second sizing process, as shown in

Figure 20, focuses on the cryogenic electric converter. In the absence of a dedicated design team to provide hot-side flow requirements, the component’s critical temperature is used to determine the hot inlet temperature. Additionally, the same working fluid and a similar inlet pressure range are used, given the similarity in heat transfer rates between the first and second HXs. The cold side fluid properties are determined by the outlet conditions of the previous HX, while the mass flow rate remains constant. Likewise, the model employs the hydraulic diameter, number of plates, pressure loss ratios for both fluid streams, and chevron angle as design variables.

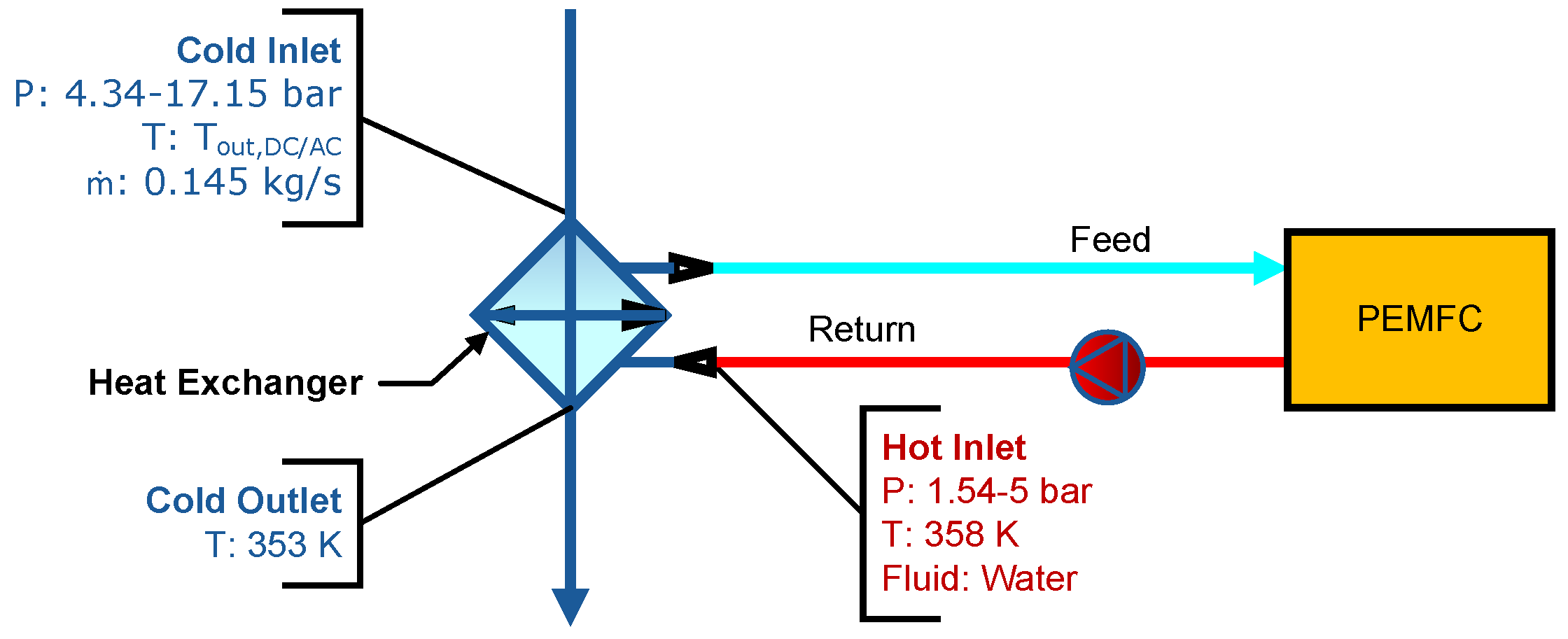

4.3.3. Fuel Cell Heat Exchangers

The third sizing process, depicted in

Figure 21, analyzes H

2 heating requirements to achieve PEMFC inlet specifications. The HX employs the FC coolant stream, in this case water, as the hot-side working fluid to demonstrate the methodology’s constraints. Hot-side inlet properties are governed by FC operating parameters. The cold-side thermal analysis adheres to previous HX methodologies while incorporating an additional outlet-temperature constraint.

Recalling the conclusions from

Figure 18 and running some sensitivity analyses, it was found that the H

2 inlet pressure exceeds the FC operating requirements when initial pressures are sufficiently above the FC working pressure, necessitating an expansion process, which, for simplicity, is assumed to be under ideal conditions (a reversible and adiabatic process). Therefore, the system architecture requires both an expansion device and a supplementary FC HX to achieve optimal operating conditions.

The H

2 undergoes cooling during an isentropic expansion, a process characteristic of various expansion devices (which can function as power generators). A fourth HX sizing process, operating under conditions similar to the first FC exchanger, incorporates two modifications: (1) the expansion device reduces gas pressure to 2 bars, which will be take as the inlet pressure; and (2) the HX pressure loss accounts for the differential at the specified sizing point bringing the final pressure to the desired value.

Figure 22 graphically shows the assumptions, while

Table 11 presents a comprehensive summary of these assumptions.

4.4. Discussion and Results

As demonstrated in

Section 4.3, the analysis requires three distinct input sets to determine a solution for the fuel distribution system TMS design problem. The framework development necessitated at least one of the following variables for HX sizing: heat transfer rate (

), cold-side outlet temperature (

), or hot-side outlet temperature (

). The analysis reveals that using only

yields the largest design space, offering both advantages and challenges for optimization potential but increasing computational requirements.

The optimization configuration was initialized with a population size of 480 individuals using the Latin hypercube sampling method. Each subsequent generation was of a smaller population size of 120 individuals, and a period of five generations was used to calculate and compare the following tolerances: , , .

Figure 23 presents the Pareto-optimal solutions, highlighted by blue dots circled in red, as the blue dots alone represent the feasible solutions. The final design point selection employs a pseudo-weight vector approach from [

34], prioritizing the minimization of system weight, followed by starting pressure, and finally system pressure losses. The selected point is located in the bottom left quadrant and represented by a green dot over a red Pareto-optimal point. In this case, the solution has a total weight of 6.6 kg, a total pressure loss of 338.9 kPa, and a starting pressure of 13.7 bar. It is also important to note that the results shown have been truncated to the area of interest by weight (≤50 kg), with all values outside the region not displayed.

Despite using high-performance computing resources, the computational analysis requires approximately 20 min of processing time due to its iterative nature, the potential absence of solutions within given constraints, and convergence challenges near boundary conditions. While designers can mitigate these computational demands by constraining the design space prior to analysis, the framework implementation prioritizes accessibility by enabling comprehensive design feasibility evaluation, particularly beneficial for designers with varying levels of expertise.

Analysis of the fuel heating path reveals comparative results across three scenarios presented in

Figure 24: ideal HXs without pressure losses and ideal expansion, non-ideal HXs incorporating pressure losses with ideal expansion, and HXs with pressure losses and single-stage expansion. The experimental data demonstrate that pressure losses diminish the LH

2’s cooling potential by 60 kW, while the implementation of single-stage expansion further reduces this capacity by 38 kW, resulting in a cumulative reduction of approximately 100 kW. These findings suggest that idealized assumptions may overestimate the system’s cooling potential by up to 10%.

The analysis reveals that actual heat availability, while lower than theoretical predictions, remains sufficient for H

2 heating requirements. Furthermore, the analysis demonstrates that HX sizing is primarily constrained by volumetric rather than mass considerations, aligning with previous research on plate-fin HXs and microchannel HXs [

35].

The computational implementation strikes a balance between solution accuracy and processing time requirements, enabling designers to evaluate design feasibility across a broad parameter space. This approach facilitates optimization at both component and system levels, providing a foundation for TMS design in advanced propulsion architectures. The methodology established here can be applied to various aerospace thermal management applications, where parametric exploration of design spaces offers advantages over conventional sizing methods.

5. Conclusions

This paper presents a HX sizing methodology that addresses the challenges at the intersection of aerospace constraints and cryogenic environments. The methodology incorporates a discretization scheme to model the thermophysical properties of cryogenic fluids, particularly hydrogen, and establishes relationships among fluid properties, heat transfer dynamics, and pressure losses. It targets the following gaps: developing a discretized sizing method for early aircraft design, enabling approaches for conventional and cryogenic applications, providing a framework that accommodates varying input design parameters, and ensuring compatibility with MDAO frameworks for TMS design.

The methodology demonstrates its versatility and accuracy through case studies, including the sizing of HX networks for hydrogen fuel cell propulsion systems and for cryogenic and conventional HX. A finding revealed that neglecting pressure losses in cryogenic HX networks leads to an overestimation of cooling potential, potentially allowing infeasible aircraft thermal management system architectures to progress to later design phases. The implementation uses constrained optimization algorithms to enable HXs to be sized to the requirements of the interfacing system and is designed for integration with MDAO frameworks to facilitate system-level analysis and optimization as part of aircraft-level design processes.