Abstract

Pintle injectors offer variable thrust capability and combustion stability advantages for liquid rocket engines. This study presents experimental and numerical investigation of spray characteristics for a liquid–liquid pintle injector using water as simulant. Ten cold flow tests covering total momentum ratio (TMR) from 0.36 to 2.76 captured spray angle variations from 26° to 80°. Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations using Ansys Fluent 2025 R1 with the Volume of Fluid method and dispersed interface modeling showed good agreement with experimental spray angles for TMR > 0.74 (error < 8%), but demonstrated increasing discrepancy at lower TMR values (up to 62% error at TMR = 0.36). This deviation indicates limitations of steady-state RANS models in capturing unsteady, fuel-dominated flow regimes. The experimental dataset provides validation benchmarks for CFD modeling and contributes to injector design optimization for sounding rocket applications.

1. Introduction

Pintle injectors have garnered significant attention in liquid rocket propulsion due to their unique operational characteristics, including wide throttling range, combustion stability, and relative design simplicity compared to conventional injector elements. Originally developed by TRW for the Apollo Lunar Module descent engine [1,2], pintle technology continues to be investigated for next-generation reusable launch vehicles.

The fundamental principle involves an axial fuel stream impinging on a radial oxidizer sheet, creating a spray cone whose characteristics directly influence combustion efficiency. The total momentum ratio (TMR), defined as the ratio of oxidizer to fuel momentum flux, governs spray pattern geometry. Previous studies established that spray angle correlates strongly with TMR [3,4,5], with higher oxidizer momentum producing wider spray cones [6].

Despite extensive research, several knowledge gaps persist. First, most published studies focus on gas–liquid configurations [7,8,9] or limited TMR ranges, leaving liquid–liquid behavior across wide operating conditions insufficiently characterized. Second, CFD validation datasets for liquid–liquid pintle injectors remain scarce [10,11,12,13], particularly for off-design conditions. Third, the applicability of RANS turbulence models to highly unsteady flow regimes requires systematic experimental verification [14,15,16].

Table 1 summarizes prior liquid–liquid pintle injector studies, demonstrating that experimental data at low TMR (<1.0) and comprehensive CFD validation datasets remain limited.

Table 1.

Summary of prior liquid–liquid pintle injector studies.

This study addresses these gaps through comprehensive cold flow experiments covering TMR from 0.36 to 2.76, coupled with steady-state RANS CFD simulations. The pintle injector investigated is being developed for a sounding rocket application. Preliminary hot fire testing demonstrated successful ignition and stable combustion, validating the fundamental design approach. The specific objectives are as follows: experimentally characterize spray angle variation across wide TMR range; validate RANS CFD predictions; identify operating regime boundaries where steady-state models remain applicable; and provide benchmark data for injector optimization.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Pintle Injector Geometry

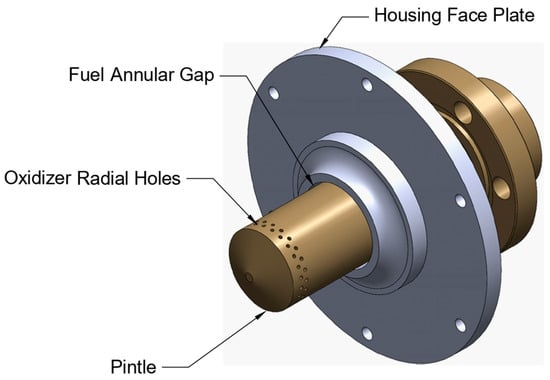

The pintle injector features a cylindrical bronze pintle element (8 mm radius) protruding 40 mm from the steel housing face plate (Figure 1). This configuration was designed for a sounding rocket engine with ethanol/LOX propellants, with water used as simulant to enable optical diagnostics while maintaining Reynolds number similarity [17,18].

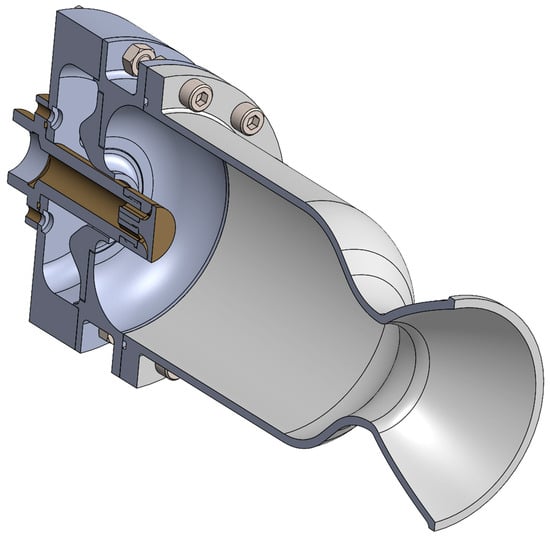

Figure 1.

Pintle injector geometry isometric view.

The injector configuration resulted from design-for-reliability considerations. Two geometries were evaluated: 48 radial holes (selected) and a continuous disk gap. The hole-based design was chosen because it provides mechanical reliability under injection pressure: the threaded disk gap exhibited gradual loosening during pressurized testing, whereas the drilled-hole configuration maintained structural integrity. Geometric parameters (8 mm pintle radius, 1.1 mm hole diameter, 0.8 mm annular clearance) were constrained by the following: (a) available manufacturing capabilities, (b) target pressure drop range (0.5–2.0 MPa), and (c) flow area ratio near unity (A_fuel/A_ox = 1.05) for balanced momentum at TMR ≈ 1.0.

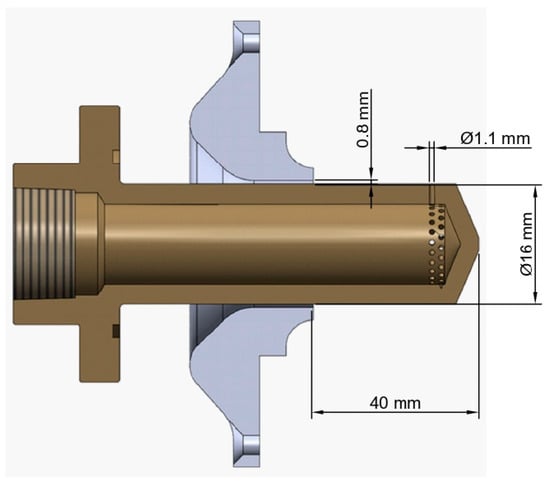

The fuel flows through an annular gap with 0.8 mm radial clearance, yielding a flow area of 40.21 mm2. Oxidizer injection occurs through 48 radial holes of 1.1 mm diameter distributed circumferentially around the pintle shaft, providing an effective flow area of 42.23 mm2 (Figure 2). For the 2D axisymmetric CFD model, these discrete holes were simplified to an equivalent continuous radial slot (0.8 mm height) to facilitate high-quality mesh generation while preserving mass flow rate through boundary conditions.

Figure 2.

Pintle injector geometry cut view with dimensions.

2.2. Experimental Setup and Instrumentation

Cold flow tests were conducted using deionized water at ambient temperature as simulant in an open-air configuration. The injector head was mounted horizontally without combustion chamber or nozzle. The test stand comprised separate pressurized feed systems equipped with calibrated turbine flowmeters (±3% accuracy; Model LWS-25, Sinomeasure Automation Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China), pressure transducers (±0.5% full scale; Model PT124B-25, Micro Sensor Co., Ltd., Xi’an, China), and pneumatically actuated ball valves (Model Q641F-16C, Wenzhou Xusheng Machinery Industry Co., Ltd., Wenzhou, China). Pressure transducers: 0–2.5 MPa full scale. Turbine flowmeters: fuel 0–3.0 L/s, oxidizer 0–2.5 L/s full-scale data acquisition sampled all channels at 10 Hz. Water testing is well-established practice in rocket injector development [18,19].

Flowmeter calibration was performed using the gravimetric method [18,19], yielding the following: Fuel: Q [L/s] = 0.001894 × RPM + 0.00579 (R2 = 0.999); Oxidizer: Q [L/s] = 0.001813 × Hz + 0.01029 (R2 = 0.998). The intercept terms account for residual flow and discharge coefficient effects [18].

High-speed imaging was conducted using a digital camera (1920 × 1080 resolution, 240 fps; Model i-SPEED 3, iX Cameras Ltd., Shanghai, China) positioned 1 m from the injector with 120° field of view, perpendicular to the spray axis [20,21]. Natural ambient lighting with light-colored background provided contrast. Spray half-angles were measured visually using on-screen ruler tools, defined as the angle between injector axis and outer spray boundary at 50 mm downstream from pintle tip. Measurement repeatability was ±2°. Steady-state conditions were identified as periods of stable spray pattern for minimum 4 s, with data extracted as time-averaged values.

2.3. Test Matrix and Operating Conditions

Ten cold flow tests spanning TMR from 0.36 to 2.76 were executed by systematically varying fuel and oxidizer flow rates, covering fuel-rich (TMR < 1.0), balanced (TMR ≈ 1.0), and oxidizer-rich (TMR > 0.82) regimes for the sounding rocket application [19,22].

Total momentum ratio (TMR) was calculated as the ratio of oxidizer to fuel momentum flux:

For water simulant at 20 °C ( = = 998 kg/m3), this simplifies to the following:

where Q is volumetric flow rate (L/s) and A is flow area (mm2). Flow areas are A_ox = 42.23 mm2 (48 holes × 1.1 mm diameter) and A_fuel = 40.21 mm2 (annular gap, 8 mm radius, 0.8 mm clearance).

Test durations ranged from 10 to 40 s. Table 2 summarizes all operating conditions including flow rates, pressures, calculated TMR values, Reynolds numbers (1.7 × 105 to 3.5 × 105, confirming fully turbulent flow), and observed spray angles.

Table 2.

Experimental data for all 10 tests.

2.4. Computational Fluid Dynamics Methodology

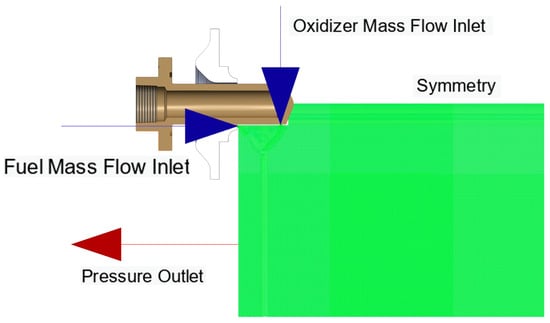

Computational fluid dynamics simulations were performed using Ansys Fluent 2025 R1 with pressure-based, steady-state solver. The multiphase flow was modeled using the Volume of Fluid (VOF) method [23,24] with dispersed interface modeling [11,12] to capture droplet formation. A 2D axisymmetric computational domain reduced computational cost while maintaining physical accuracy. The 48 discrete fuel injection holes were simplified to an equivalent continuous radial slot (0.8 mm height) to facilitate mesh generation while preserving mass flow rate through velocity-inlet boundary conditions [10,13,16,17].

The axisymmetric simplification preserves total mass flow rate and integrated momentum flux while reducing computational cost by >95%. However, this approach has inherent limitations: discrete droplets cannot be individually resolved in 2D axisymmetric geometry, as they would appear as toroidal rings rather than spherical particles. Therefore, the model prioritizes circumferentially averaged spray behavior over localized droplet dynamics. The simplification maintains equivalent total flow area (42.23 mm2), mass flow rates, and momentum flux matching experimental Q·V products, while sacrificing local three-dimensional flow structure details.

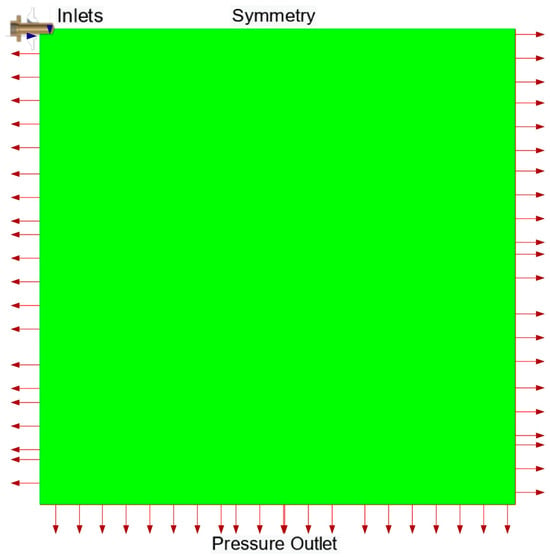

The computational mesh (Figure 3 and Figure 4) consisted of 6,251,610 cells with minimum cell size of 0.25 mm near the injector and liquid–gas interface. Dynamic adaptive mesh refinement was applied at the phase interface based on volume fraction gradients [11,24]. A domain size convergence study tested 0.2 × 0.2 m, 0.4 × 0.4 m, and 1.0 × 1.0 m domains. The 1.0 × 1.0 m domain showed less than 1° variation in spray angle, confirming domain independence.

Figure 3.

CFD domain inlet boundary conditions.

Figure 4.

Overall CFD domain with 1 × 1 m size.

Boundary conditions: mass flow-inlet for fuel and oxidizer (calculated from measured flow rates in Table 1), pressure-outlet at atmospheric conditions (101,325 Pa), no-slip wall on pintle surface, and axis boundary condition along centerline. The k-ω SST turbulence model captured turbulent mixing in the shear layer [13]. Physical properties for water at 20 °C: density 998 kg/m3, viscosity 0.001 Pa·s, surface tension 0.0728 N/m. Volume fraction formulation was implicit with cutoff of 1 × 10−6.

Simulations ran on AMD Threadripper (AMD Inc., Shenzhen, China) workstation using 16 cores, with approximately 3 h per operating condition (total: 30 CPU-hours for 10 cases). Convergence was achieved when residuals dropped below 1 × 10−4 and spray angle remained constant (<1° variation) over iterations. Spray angles were extracted from the 0.1 volume fraction.

3. Results

3.1. Experimental Flow Characterization

Ten cold flow tests were successfully conducted with TMR ranging from 0.36 to 2.76. Flow rates varied from 0.82 to 1.73 L/s for fuel and 1.07 to 1.61 L/s for oxidizer. All tests achieved fully turbulent conditions (Re > 1.7 × 105). Visual observations revealed distinct flow regime transitions: at low TMR, there were narrow asymmetric sprays with periodic oscillations; at balanced TMR ≈ 1.0, there were symmetric moderate spray patterns; at high TMR, there were wide symmetric spray cones with minimal unsteadiness.

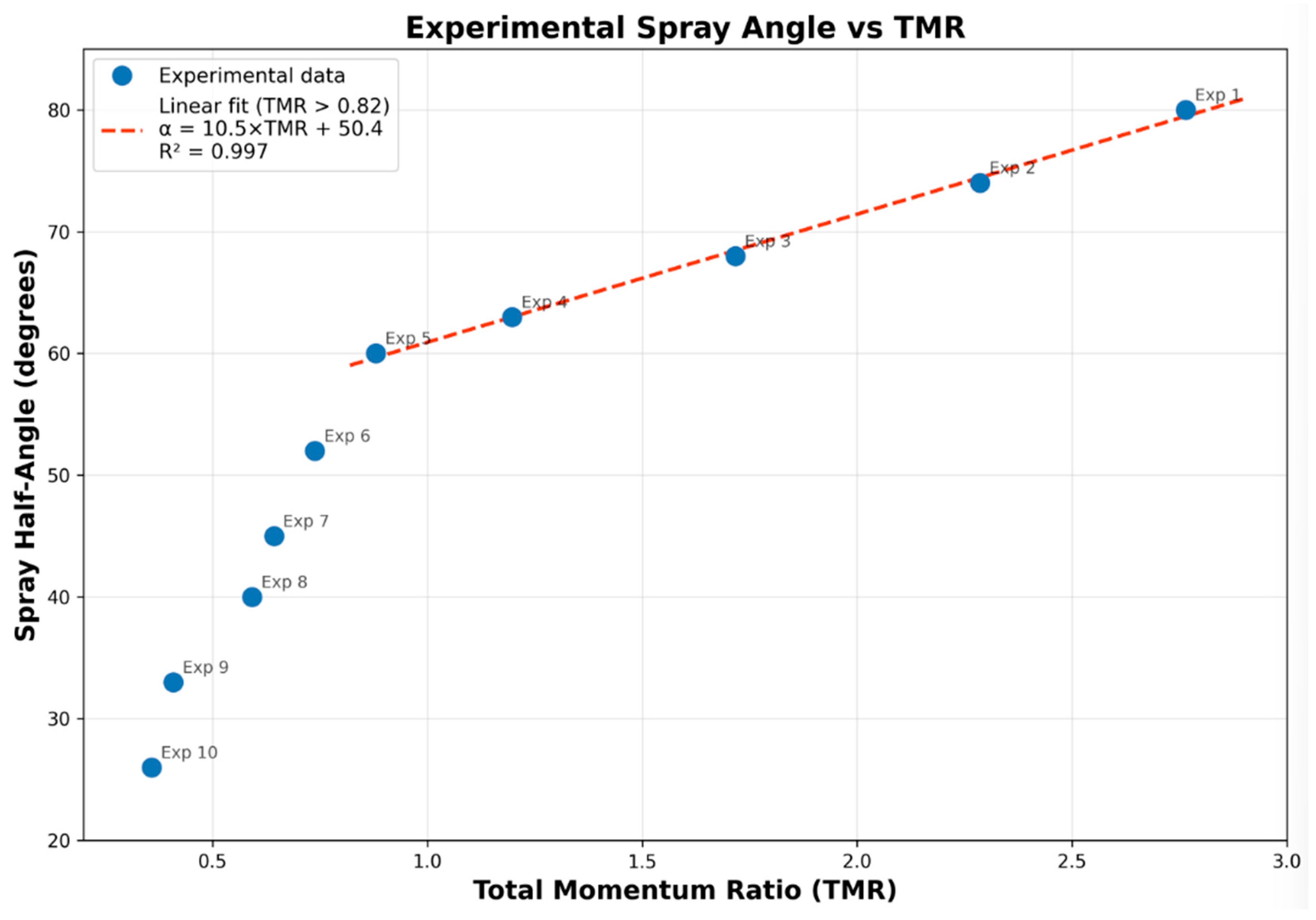

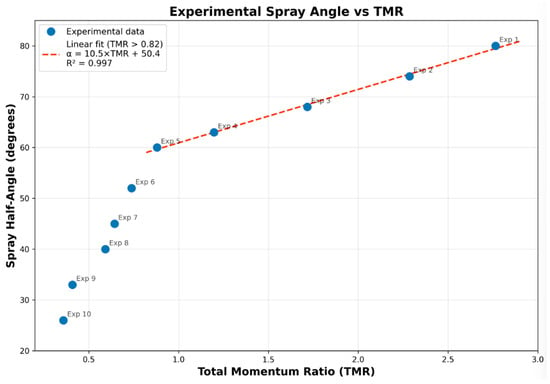

3.2. Spray Angle Dependence on TMR

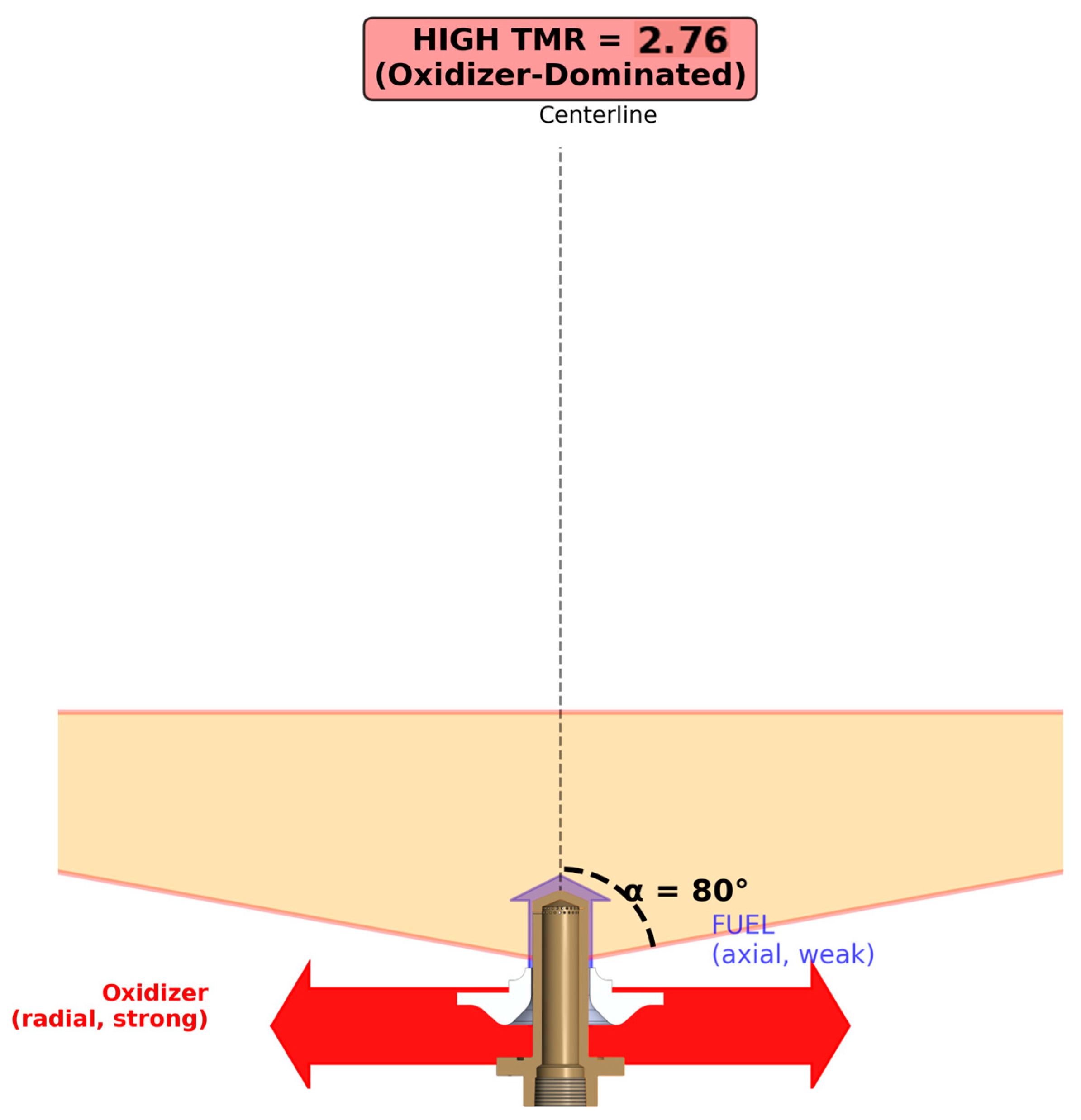

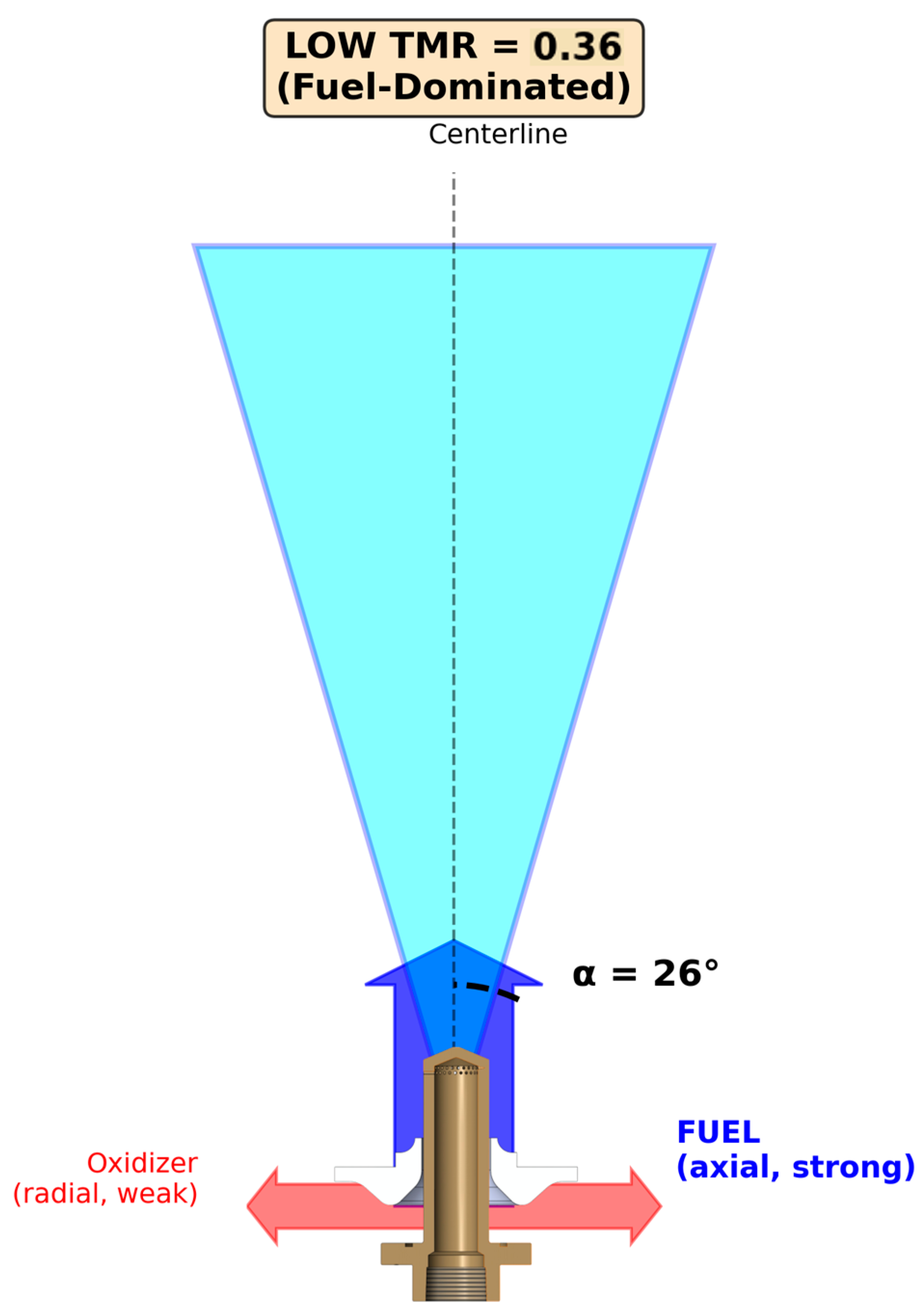

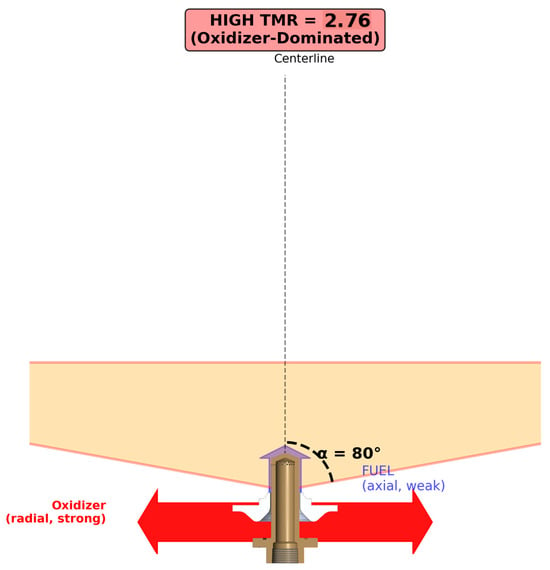

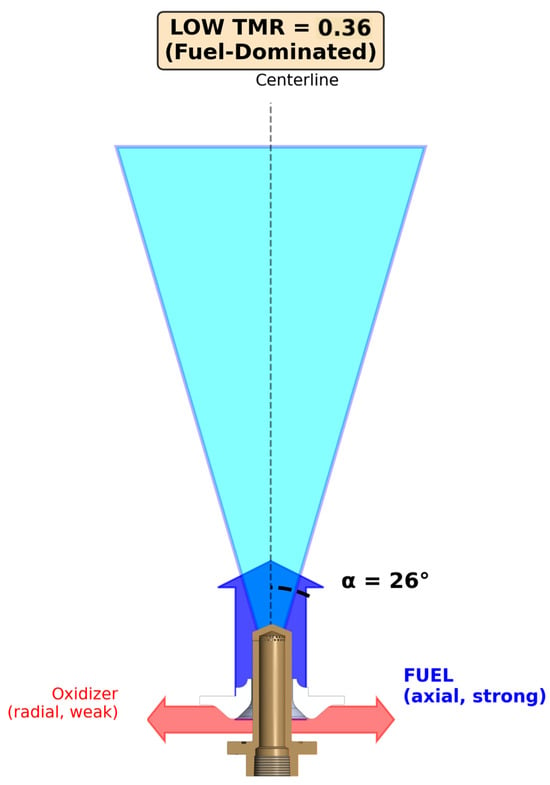

Spray angle exhibited strong positive correlation with TMR, ranging from 26° at TMR = 0.36 to 80° at TMR = 2.76. For TMR > 0.82, the relationship was approximately linear: α = 10.5 × TMR + 50.4 (R2 = 0.997). For TMR < 1.0, steeper nonlinear behavior was observed. The physical mechanism is momentum balance at the liquid–liquid interface [4,5,6]: at high TMR, dominant radial oxidizer momentum deflects the axial fuel stream outward (Figure 5); as TMR decreases, axial fuel momentum resists deflection, producing narrower sprays (Figure 6). Figure 7 shows the quantitative relationship.

Figure 5.

Spray mechanism at high TMR with wide cone geometry.

Figure 6.

Spray mechanism at low TMR with narrow cone geometry.

Figure 7.

Experimental spray angle vs. TMR with trendlines.

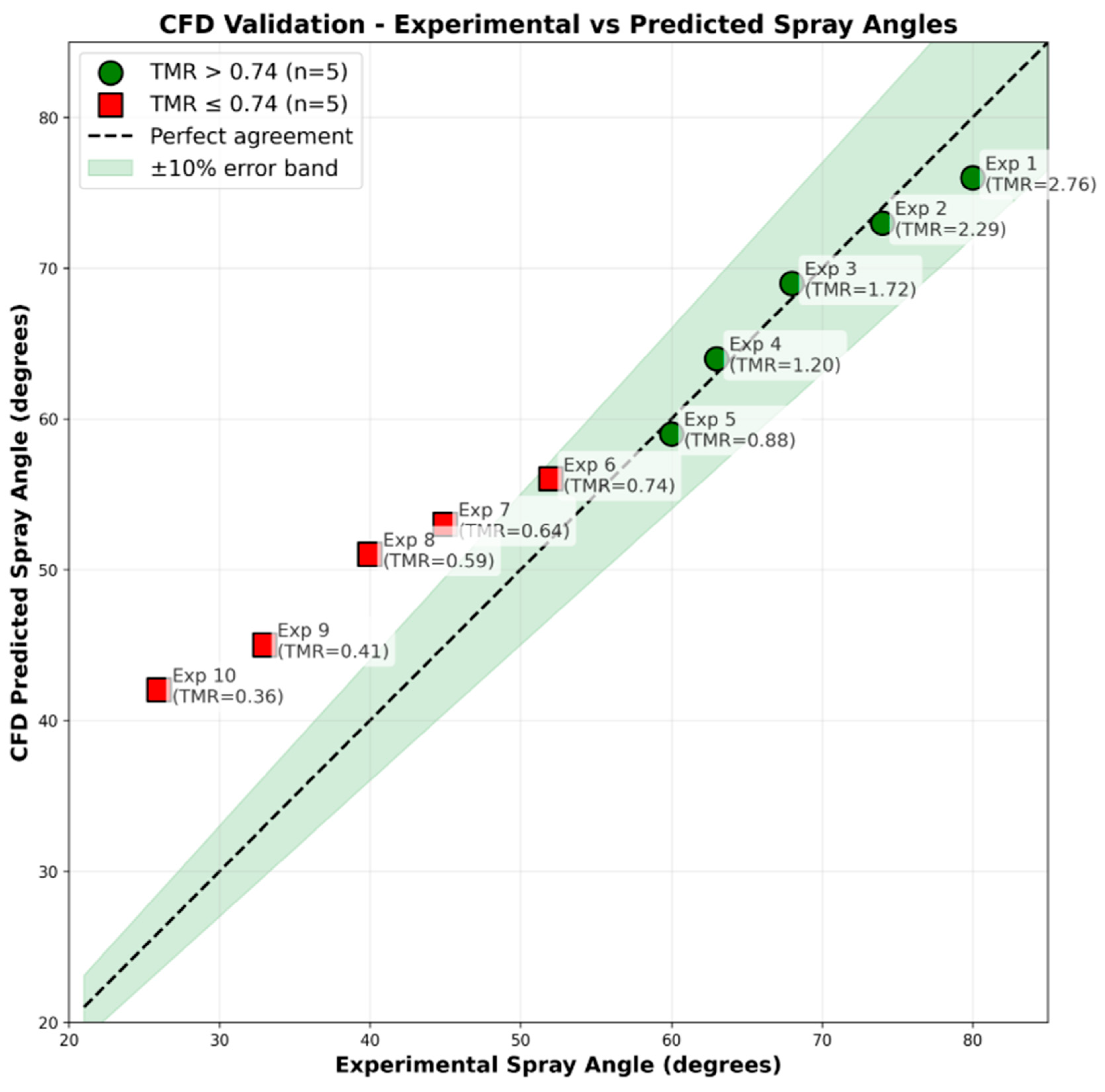

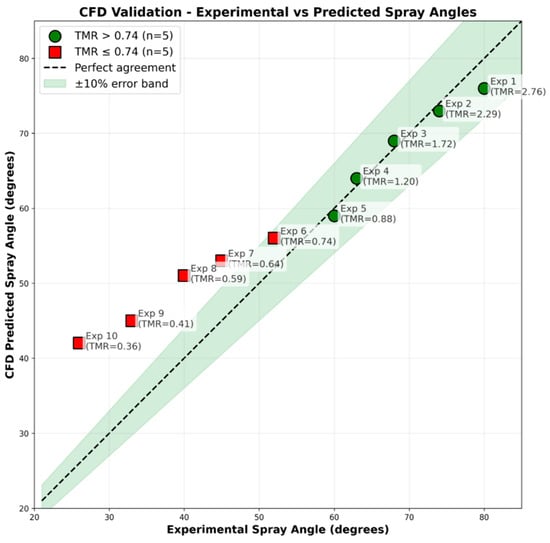

3.3. CFD Validation

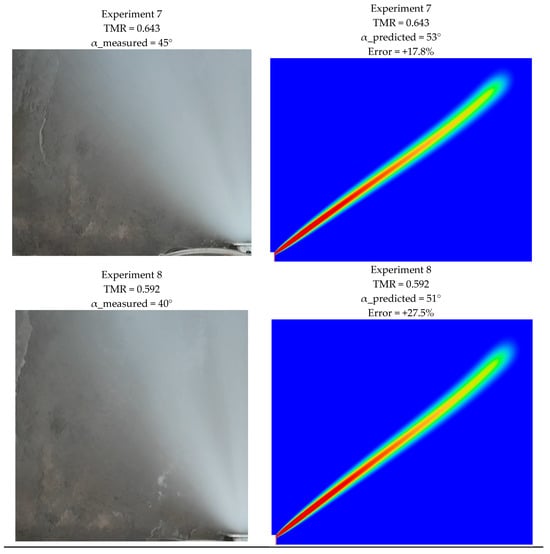

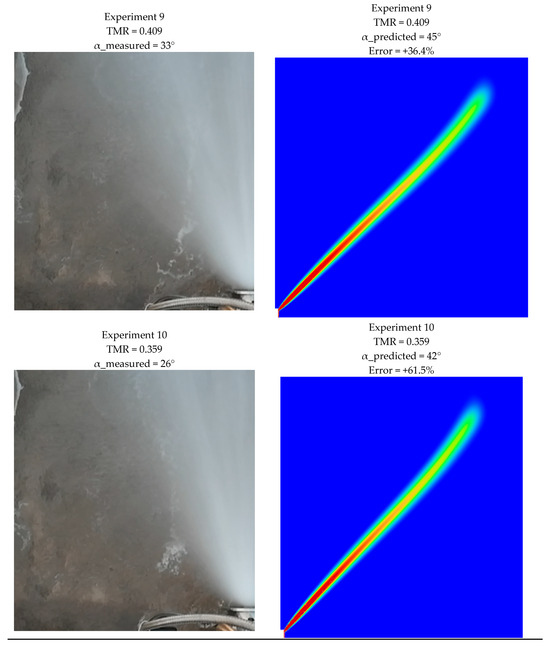

Steady-state RANS CFD predictions showed clear regime-dependent accuracy. For TMR ≥ 0.74, excellent agreement with experiments achieved mean absolute percentage error of 3.8% and maximum error of 7.7%. However, for TMR < 0.74, systematic overprediction occurred, with errors increasing progressively (up to 62% at TMR = 0.36). This transition indicates breakdown of steady-state modeling assumptions when flow becomes dominated by unsteady phenomena including vortex shedding, large-scale oscillations, and intermittent fuel jet penetration (Figure 8). Additionally, the 2D axisymmetric simplification cannot capture discrete-hole effects and individual droplet trajectories at low TMR, where fuel jets penetrate as distinct streams rather than continuous sheets. For TMR > 0.74, the spray structure is more uniform and circumferentially symmetric, making the axisymmetric approximation reasonable.

Figure 8.

CFD validation—experimental vs. predicted spray angles.

3.4. Flow Field Structure

CFD visualization revealed distinct flow structures across the TMR range [6,7]. At high TMR = 2.76 (oxidizer-rich), there was a wide symmetric spray pattern with smooth interfaces dominated by radial oxidizer momentum (80° spray cone). At balanced TMR = 0.88, there was a moderate spray width (60°) with efficient mixing and small recirculation zones. At low TMR = 0.36 (fuel-rich), fuel axial momentum penetrated deeply into oxidizer stream, creating a narrow 26° spray cone with pronounced asymmetry and large recirculation zones. The side-by-side comparison confirms regime-dependent accuracy, with CFD closely matching experiments at high and balanced TMR (Table 3 and Figure 9) but overpredicting spray width at low TMR. These flow structures are consistent with liquid jet breakup phenomena in crossflow conditions [25,26]. The results visualization for all 10 experiments is provided in Appendix A (Figure A1).

Table 3.

Detailed validation metrics.

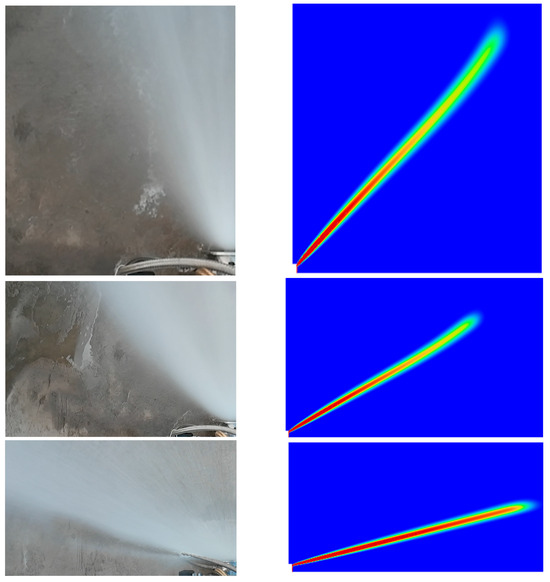

Figure 9.

Flow field visualization—3 × 2 grid showing experimental images (left column) and CFD predictions (right column) for three representative TMR conditions: Experiment 10, Experiment 5, Experiment 1.

3.5. Preliminary Hot Fire Validation

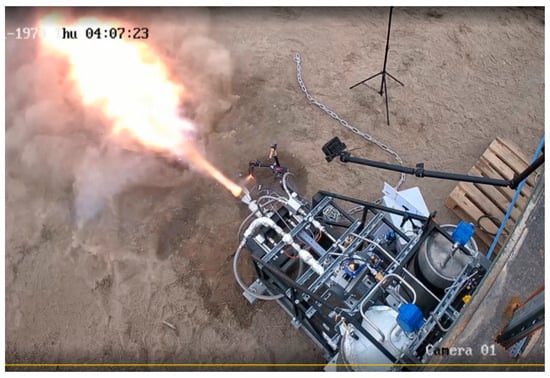

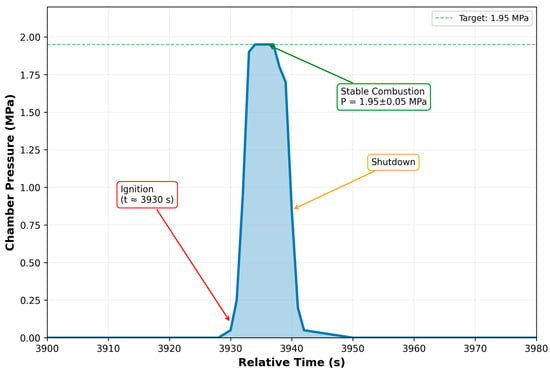

The pintle injector was integrated into complete engine assembly with a combustion chamber, a convergent–divergent nozzle, and an instrumented ethanol/LOX feed system (Figure 10). Hot fire testing demonstrated successful ignition with chamber pressure rapidly rising to operational level within 2 s. Visual observation confirmed symmetric flame structure (Figure 11) throughout the burn. Steady-state combustion was maintained for approximately 10 s at a peak pressure of 1.95 ± 0.05 MPa (Figure 12). The pressure profile showed <3% variation during the stable combustion period, confirming the absence of flow instabilities.

Figure 10.

CAD model of complete engine assembly showing injector, combustion chamber, and nozzle.

Figure 11.

Photograph during hot fire test operation showing exhaust plume.

Figure 12.

Chamber pressure during hot fire test.

The test operated at design-point propellant flow rates corresponding to TMR ≈ 1.1, where cold flow experiments indicated symmetric spray patterns. The observed flame symmetry and stable combustion suggest that water simulant cold flow characterization provides useful guidance for injector design, though additional hot fire testing and performance characterization will be reported in future work.

4. Discussion

4.1. Physical Mechanisms Governing Spray Behavior

The spray angle mechanism operates as follows: fuel flows axially through the annular gap while oxidizer injects radially through 48 holes. The spray angle α is measured from the injector centerline (axial direction).

At low TMR (fuel-dominated regime, TMR < 1.0), the strong axial fuel momentum overcomes the weak radial oxidizer injection, producing a narrow spray cone aligned with the injector axis. At TMR = 0.36, α = 26° indicates the spray flows predominantly along the axis with minimal radial deflection.

At high TMR (oxidizer-dominated regime, TMR > 1.0), the strong radial oxidizer momentum deflects the axial fuel stream outward, creating a wide spray cone nearly perpendicular to the axis. At TMR = 2.76, α = 80° indicates substantial radial deflection, with the spray forming a wide conical sheet.

The relationship cos(α) ≈ 1/(1 + TMR) derived in [4] quantifies this momentum balance, predicting α ≈ 70° at TMR = 2.76, consistent with the observed 80°. The linear correlation for TMR > 0.82 (R2 = 0.997, Figure 7) suggests flow physics dominated by simple momentum exchange, with secondary effects (viscosity, surface tension, turbulence [27,28]) playing minor roles.

As TMR decreases toward unity, axial fuel momentum becomes comparable to radial oxidizer momentum, producing balanced spray patterns (α ≈ 60° at TMR = 1.0). Below TMR ≈ 0.74, strong axial fuel enables penetration through the oxidizer stream [26,29], creating recirculation zones and flow asymmetries. The flow becomes inherently unsteady with coherent structures evolving on timescales comparable to mean flow residence time.

4.2. Limitations of Steady-State RANS Modeling

The systematic CFD overprediction at TMR < 0.74 indicates fundamental limitations of steady-state RANS modeling for fuel-dominated regimes. At low TMR, coherent unsteady structures dominate: vortex shedding, large-scale oscillations, and intermittent fuel penetration occur on timescales not separable from mean flow. Time-averaging produces a solution that does not represent any instantaneous flow state—the computed spray angle reflects a statistical average differing substantially from actual time-varying patterns. For accurate prediction, time-resolved approaches are required. Large Eddy Simulation (LES) resolves large-scale structures explicitly [12,13,14], while hybrid RANS-LES methods [15] offer computational compromise. These advanced methods require 10–100× more resources than steady RANS but can capture unsteady dynamics. The present study quantifies the TMR threshold (≈0.74) where such methods become necessary, providing practical guidance for simulation approach selection.

4.3. Design Implications and Literature Comparison

For sounding rocket applications, operating near TMR ≈ 1.0 provides optimal spray symmetry and predictable CFD behavior. The TMR ≈ 0.74 threshold delineates predictable (high-TMR) from unpredictable (low-TMR) behavior [3,4,30]. From a steady-state CFD modeling perspective, operation below TMR ≈ 0.74 requires advanced unsteady methods (LES or hybrid RANS-LES) for accurate prediction. The injector is physically capable of stable operation at low TMR, as demonstrated experimentally, but steady-state RANS cannot reliably predict spray behavior in this regime. For throttling applications, preferential reduction in fuel flow (maintaining high TMR) preserves CFD reliability over oxidizer reduction. The strong spray angle variation (54° across range) requires combustion chamber geometry to accommodate varying spray footprint or variable-geometry features.

The observed trends are consistent with previous pintle injector studies [1,2], though the present work extends characterization to lower TMR values. Published data from TRW heritage engines generally focus on near-unity or oxidizer-rich TMR ranges. The quantified CFD accuracy threshold provides practical guidance not clearly established in the prior literature [3,5,6,27,28]. The spray angle falls within ranges reported for similar liquid–liquid configurations. The successful application of VOF with dispersed interface modeling demonstrates appropriateness for pintle injector CFD [10,11,12,13].

5. Conclusions

This study systematically characterized liquid–liquid pintle injector spray behavior across TMRs from 0.36 to 2.76 through combined experimental testing and computational simulation. Key findings include the following:

- (1)

- Spray angle varies from 26° to 80° across the TMR range, with approximately linear dependence for TMR > 0.82 (α = 10.5 × TMR + 50.4, R2 = 0.997). For TMR < 0.82, a steeper nonlinear trend indicates transition to fuel-dominated physics.

- (2)

- Steady-state RANS CFD accurately predicts spray patterns for TMR > 0.74 (MAPE 3.2%, maximum error 7.7%), demonstrating the validity of the steady-state assumption for oxidizer-rich and balanced regimes.

- (3)

- For TMR < 0.74, steady-state RANS systematically overpredicts spray angles (up to 62% error at TMR = 0.36), indicating breakdown when fuel-dominated regimes exhibit strong unsteady behavior. The critical threshold TMR ≈ 0.74 delineates where advanced unsteady simulation methods become necessary.

- (4)

- For sounding rocket design, operation near TMR ≈ 0.88 provides optimal spray characteristics with predictable CFD behavior. Throttling should preferentially occur on the high-TMR side to preserve modeling reliability.

- (5)

- Water cold flow testing provides cost-effective spray characterization, correlating well with hot fire behavior. Preliminary hot fire testing demonstrated successful ignition and stable combustion, validating the fundamental design approach. The cold flow dataset and validated CFD methodology provide a foundation for predicting injector behavior across the engine’s throttling envelope.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.J.; methodology, I.J. and D.K.; software, I.J. and S.S.; validation, I.J., D.K. and S.S.; formal analysis, A.B. and Y.T.; investigation, A.B. and R.Z.; resources, Y.T. and R.Z.; data curation, M.N.; writing—original draft preparation, I.J.; writing—review and editing, M.N. and M.O.; visualization, Y.T. and A.B.; supervision, M.N.; project administration, M.O.; funding acquisition, M.N. and M.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Committee of Science of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan, grant number BR249008/0224.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Sergei Stepanov and Denis Khamzatov were employed by the company LLC Thrust. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

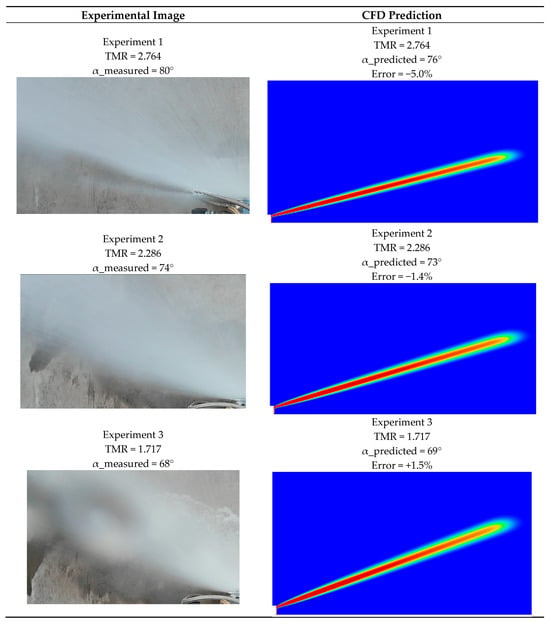

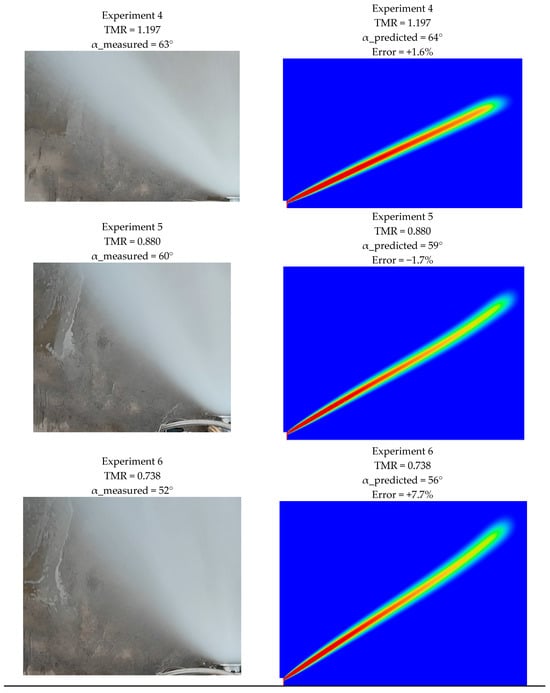

Appendix A

Figure A1 presents side-by-side comparison of experimental high-speed images (left column) and CFD-predicted water volume fraction contours (right column) for all ten test cases, arranged in order of increasing total momentum ratio. Each panel is annotated with experiment number, TMR value, measured spray angle, predicted spray angle, and relative error.

Figure A1.

Complete experimental and CFD spray pattern comparison.

Figure A1.

Complete experimental and CFD spray pattern comparison.

References

- Dressler, G.; Bauer, J. TRW Pintle Engine Heritage and Performance Characteristics. In 36th AIAA/ASME/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference and Exhibit; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics: Reston, VA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Elverum, G.W.; Staudhammer, P. The Effect of Rapid Liquid-Phase Reactions on Injector Design and Combustion in Rocket Motors; NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 1959.

- Chen, H.; Li, Q.; Cheng, P. Experimental Research on the Spray Characteristics of Pintle Injector. Acta Astronaut. 2019, 162, 424–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, P.; Li, Q.; Xu, S.; Kang, Z. On the Prediction of Spray Angle of Liquid-Liquid Pintle Injectors. Acta Astronaut. 2017, 138, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Zhou, R. Experimental Study on the Combustion Characteristics of LOX/LCH4 Pintle Injectors. Fuel 2023, 339, 126909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninish, S.; Vaidyanathan, A.; Nandakumar, K. Spray Characteristics of Liquid-Liquid Pintle Injector. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 2018, 97, 324–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Xu, X.; Yang, Q.; Zhao, R.; Jin, Y. Experimental and Numerical Investigations on the Spray Characteristics of Liquid-Gas Pintle Injector. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2022, 121, 107354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhakaran, R.; Basavanahalli, R. Gas-on-Liquid Impinging Injectors: Some New Results. In Proceedings of the 49th AIAA/ASME/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference, San Jose, CA, USA, 14–17 July 2013; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics: Reston, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, R.W.; Martin, D.J.; Wunderlin, N.; Pitot, J.; Brooks, M.J. Facility Design and Cold Flow Testing Operations for an 18kN LOX/Kerosene Liquid Rocket Engine. In Proceedings of the AIAA SCITECH 2024 Forum, Orlando, FL, USA, 8–12 January 2024; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics: Reston, VA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Son, M.; Yu, K.; Radhakrishnan, K.; Shin, B.; Koo, J. Verification on Spray Simulation of a Pintle Injector for Liquid Rocket Engine. J. Therm. Sci. 2016, 25, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, M.; Schwarze, R. 3D-Coupling of Volume-of-Fluid and Lagrangian Particle Tracking for Spray Atomization Simulation in OpenFOAM. SoftwareX 2020, 11, 100483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, R.; Cheng, G.; Chen, Y.-S.; Garcia, R. CFD Simulation of Liquid Rocket Engine Injectors; NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 2001.

- Tucker, K.; West, J.; Williams, R.; Lin, J.; Rocker, M.; Canabal, F.; Robles, B.; Garcia, R.; Chenoweth, J. Using CFD as Rocket Injector Design Tool: Recent Progress at Marshall Space Flight Center; NASA: Washington, DC, USA, 2003.

- Cheng, G.; Farmer, R. CFD Spray Combustion Model for Liquid Rocket Engine Injector Analyses. In Proceedings of the 40th AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting & Exhibit, Reno, NV, USA, 14–17 January 2002; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics: Reston, VA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Cha, J.; Andersson, E.; Bohlin, A. A Numerical Approach to Optimize the Design of a Pintle Injector for LOX/GCH4 Liquid-Propellant Rocket Engine. Aerospace 2023, 10, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.; Han, S.; Ryu, C.; Ko, Y. Design of Pintle Injector Using Kerosene-LOx as Propellant and Solving the Problem of Pintle Tip Thermal Damage in Hot Firing Test. Acta Astronaut. 2022, 201, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, R.; Moser, M.; Hulka, J.; Jones, G. Cold Flow Testing for Liquid Propellant Rocket Injector Scaling and Throttling. In Proceedings of the 42nd AIAA/ASME/SAE/ASEE Joint Propulsion Conference & Exhibit, Sacramento, CA, USA, 9–12 July 2006; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics: Reston, VA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Tharakan, T.J.; Rafeeque, T.A. The Role of Backpressure on Discharge Coefficient of Sharp Edged Injection Orifices. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2016, 49, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.-J.; Rho, B.-J.; Oh, J.-H.; Kwon, K.-C. Atomization Characteristics of a Double Impinging F-O-O-F Type Injector with Four Streams for Liquid Rockets. KSME Int. J. 2000, 14, 466–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebriaee, A.; Akbari, M.J.; Zarrin, F.A. Droplet Shadow Velocimetry Based on Monoframe Technique. At. Sprays 2018, 28, 581–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castanet, G.; Dunand, P.; Caballina, O.; Lemoine, F. High-Speed Shadow Imagery to Characterize the Size and Velocity of the Secondary Droplets Produced by Drop Impacts onto a Heated Surface. Exp. Fluids 2013, 54, 1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brackbill, J.U.; Kothe, D.B.; Zemach, C. A Continuum Method for Modeling Surface Tension. J. Comput. Phys. 1992, 100, 335–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirjalili, B.; Jain, S.; Dodd, M. Interface-Capturing Methods for Two-Phase Flows: An Overview and Recent Developments. 2017. Available online: https://web.stanford.edu/~sjsuresh/mirjalili2017.pdf (accessed on 31 December 2025).

- Popinet, S. Numerical Models of Surface Tension. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 2018, 50, 49–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.-K.; Kirkendall, K.A.; Fuller, R.P.; Nejad, A.S. Breakup Processes of Liquid Jets in Subsonic Crossflows. J. Propuls. Power 1997, 13, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazallon, J.; Dai, Z.; Faeth, G.M. Primary Breakup of Nonturbulent Round Liquid Jets in Gas Crossflows. At. Sprays 1999, 9, 291–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashgriz, N. (Ed.) Handbook of Atomization and Sprays: Theory and Applications; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, S.P.; Reitz, R.D. Drop and Spray Formation from a Liquid Jet. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 1998, 30, 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, K.A.; Aalburg, C.; Faeth, G.M. Breakup of Round Nonturbulent Liquid Jets in Gaseous Crossflow. AIAA J. 2004, 42, 2529–2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkal, B.; Sümer, B.; Aksel, M.H. Design Procedure and Cold Flow Experiments of a Pintle Injector. In Proceedings of the AIAA Propulsion and Energy 2019 Forum, Indianapolis, IN, USA, 19–22 August 2019; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics: Reston, VA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.