Abstract

Research into Remotely Piloted Aircraft Systems (RPASs) has expanded rapidly, yet the competencies, knowledge, skills, and other attributes (KSaOs) required of RPAS pilots remain comparatively underexamined. This review consolidates existing studies addressing human performance, subject matter expertise, training practices, and accident causation to provide a comprehensive account of the KSaOs underpinning safe civilian and commercial drone operations. Prior research demonstrates that early work drew heavily on military contexts, which may not generalize to contemporary civilian operations characterized by smaller platforms, single-pilot tasks, and diverse industry applications. Studies employing subject matter experts highlight cognitive demands in areas such as situational awareness, workload management, planning, fatigue recognition, perceptual acuity, and decision-making. Accident analyses, predominantly using the human factors accident classification system and related taxonomies, show that skill errors and preconditions for unsafe acts are the most frequent contributors to RPAS occurrences, with limited evidence of higher-level latent organizational factors in civilian contexts. Emerging research emphasizes that RPAS pilots increasingly perform data-collection tasks integral to professional workflows, requiring competencies beyond aircraft handling alone. The review identifies significant gaps in training specificity, selection processes, and taxonomy suitability, indicating opportunities for future research to refine RPAS competency frameworks and support improved operational safety.

1. Introduction

Popular culture continues to frame drones as detached instruments of remote warfare, often emphasizing autonomy and precision over human control [1]. From Good Kill and Eye in the Sky to more recent portrayals in Angel Has Fallen and 6 Underground, uncrewed aircraft are depicted as self-directed machines rather than as systems operated through complex human–machine partnerships [2]. This portrayal mirrors a broader misunderstanding found in parts of the academic and industrial discourse [3], where attention remains weighted towards technical development rather than the competencies and decision-making of the human pilot [4]. Yet, the human operator remains integral to all remotely piloted aviation activity [5]; technological sophistication has not removed, but rather transformed, the cognitive and procedural demands placed upon the pilot [6].

As indicated in Table 1, academic attention to uncrewed aviation has grown in parallel with technological capability [7], producing a rapidly expanding and increasingly specialized literature. However, this expansion has been uneven: the technical dimensions of remotely piloted operations have received sustained focus, while the human–system component has remained comparatively underexplored. The resulting corpus provides extensive detail on platforms [8], autonomy [9], and sensing [10], yet offers only fragmentary insight into the cognitive, procedural, and experiential competencies that underpin safe and effective RPAS operation. Section 2, therefore, outlines this developmental trajectory in greater detail, situating the present review within the broader evolution of remotely piloted aircraft system (RPAS) research (as well as UAV, uncrewed air vehicles, and UAS, uncrewed aerial systems).

The purpose of this review is to consolidate and critically examine existing research on the competencies, knowledge, skills, and other attributes (KSaOs) required of RPAS pilots, with particular attention to civilian and commercial operations. Knowledge is defined as the information gained through both formal and informal teaching. Skill is that required to do a task and may be gained through teaching, practice, or a combination of both. Abilities and attributes are seen as innate, not learned, and required for the successful completion of tasks [11]. An understanding of these factors in RPAS operations can inform and lead to best practice, as well as the development of standards for the training and licensing of RPAS pilots.

Identifying RPAS pilot KSaOs cannot be achieved through a single body of literature. Unlike conventionally crewed aviation, where competencies have been refined over decades of harmonized regulation and operational experience, RPAS operations span diverse aircraft types, operational contexts, and levels of automation. As a result, this review synthesizes evidence from complementary research traditions, including studies drawing on subject matter experts, research into human performance and training, and analyses of accidents and incidents. Together, these perspectives provide converging insight into what constitutes competent RPAS pilot performance, how such competence is developed and maintained, and how deficiencies manifest in operational failures.

Table 1.

Prior reviews covering human factors for UAV/UAS/RPAS.

Table 1.

Prior reviews covering human factors for UAV/UAS/RPAS.

| Ref | Year | Title | Perspective |

|---|---|---|---|

| [12] | 2025 | Research progress on key technologies for human factors design of unmanned aircraft systems | HMI |

| [13] | 2025 | Key Technology for Human–System Integration of Unmanned Aircraft Systems in Urban Air Transportation | HMI |

| [14] | 2024 | Progress and prospect of forest fire monitoring based on the multi-source remote sensing data | Applications |

| [15] | 2023 | Application of drones in the architecture, engineering, and construction (AEC) industry | Applications |

| [16] | 2022 | The black hole illusion: A neglected source of aviation accidents | Perception |

| [17] | 2018 | Feasibility study for drone-based masonry construction of real-scale structures | Applications |

| [18] | 2018 | Avionics Human-Machine Interfaces and Interactions for Manned and Unmanned Aircraft | HMI |

| [19] | 2017 | A meta-analysis of human–system interfaces in unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) swarm management | HMI |

| [20] | 2016 | Remote pilot aircraft system (RPAS): Just culture, human factors and learnt lessons | Just culture |

| [21] | 2006 | Human Factors in U.S. Military Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Accidents | Accidents |

| [22] | 2006 | Guiding the Design of a Deployable UAV Operations Cell | Operations |

| [23] | 2006 | Modeling and Operator Simulations for Early Development of Army Unmanned Vehicles: Methods and Results | Operations |

| [24] | 2006 | UAV Human Factors: Operator Perspectives | Operations |

| [25] | 2003 | Human-centered design of unmanned aerial vehicles | HMI |

| [26] | 2002 | UAVs and the human factor | General |

While the focus is on civilian pilots, studies from military settings are also accessed owing to the greater number of studies from this domain. In conventional crewed aviation, findings from military studies have been successfully used in civilian aviation. Although a number of empirical investigations have explored aspects of human performance, ranging from human–machine interfaces (HMIs) and situational awareness to accident causation, design, and automation, these studies remain focused across technical and operational domains. No prior review has attempted to synthesize this work, and notably, few studies have addressed the educational and training dimensions of RPAS pilot development. To provide a foundation for this analysis, Table 1 collates fifteen studies published between 2002 and 2025, grouped by their primary perspective and methodological approach. This represents all reviews from Scopus with the two search terms “human factors” and (UAV or UAS or RPAS), restricted to reviews, with no date filtering (completed on 1 November 2025). This collection reveals a concentration of research in design, safety, and human factors, but an evident gap in the literature addressing how competencies are taught, assessed, and maintained in educational settings.

2. Background

In examining the competencies required for safe RPAS operations, this review adopts a working distinction between knowledge, skills, and other attributes. Knowledge is defined as the information gained through both formal and informal teaching, including an understanding of rules, procedures, systems, and operational constraints relevant to RPAS operations. Skills are defined as the capability required to perform tasks and may be developed through instruction, practice, or a combination of both. Skills, therefore, encompass the cognitive, perceptual, and motor abilities necessary to execute RPAS operations reliably under operational conditions. Other attributes, including abilities, are considered to be innate or not directly learned and are required for the successful completion of tasks.

These distinctions are consistent with established approaches to analyzing human performance and competency requirements across aviation and other safety-critical domains. However, it is recognized that the literature relating to RPAS pilots does not always apply these terms consistently. Concepts such as situational awareness, workload management, decision-making, and judgement are variously described as knowledge, skills, attributes, or performance outcomes, depending on disciplinary perspective and study design. In synthesizing the literature, this review preserves the terminology used by original authors while mapping reported findings onto the above working definitions to provide a consistent analytical framework.

This pragmatic approach does not seek to impose a rigid theoretical taxonomy on diverse literature, but rather to enable comparison across studies drawing on different methodologies and perspectives. Using these working definitions, the review integrates findings from subject matter expert studies, training and human performance research, and accident and incident analyses to examine how variations in KSaOs contribute to unsafe RPAS outcomes.

The requirement to identify RPAS pilot knowledge, skills, and other attributes arises from the manner in which uncrewed aircraft have entered existing aviation systems. While aircraft without a human pilot onboard have a long history, the widespread civilian use of RPAS has occurred largely within pre-existing regulatory and operational structures developed for conventionally crewed aviation [27]. The question is, then, should RPAS be treated as another form of aircraft operation, subject to existing rules and competency expectations, or whether they represent a distinct mode of aviation activity requiring specific and differentiated competencies [28].

If RPAS are treated as equivalent to conventionally crewed aircraft, training, licensing, and competency frameworks tend to be adapted from existing pilot syllabi. However, this approach risks overlooking the specific operational conditions faced by RPAS pilots, including remote aircraft control, reliance on mediated sensory information, and task-specific mission demands. As a result, determining whether existing aviation competencies are sufficient or whether additional or modified KSaOs are required becomes a critical question for safe RPAS operations. Addressing this question necessitates examination of multiple sources of evidence, including expert practice, training and performance research, and analyses of operational failures.

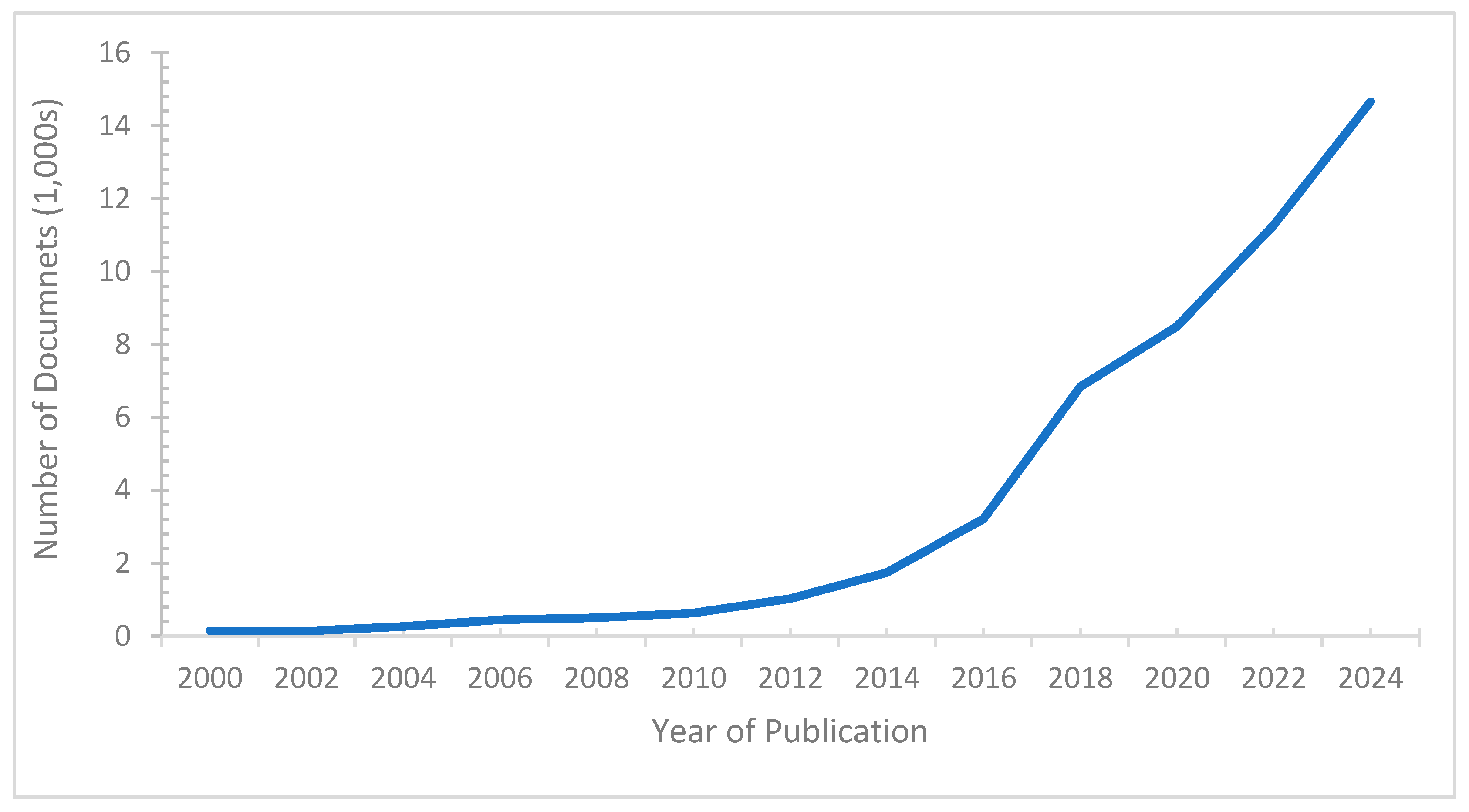

As technology integral to remotely piloted operations has developed, becoming cheaper and more accessible, so has the diverse range of tasks that uncrewed flying is used for [29]. The continued development of the corresponding technology is seeing an ever-growing evolution in remotely piloted operations. This growth in usage is reflected in the literature devoted to uncrewed flight. Research work and subsequent publications began to develop in the second half of the twentieth century. A rapid increase in research into uncrewed flights occurred in the twenty-first century. The number of publications for uncrewed flights and related subjects has continued to surge decade by decade. A Boolean search in Web of Science of “Remotely Piloted Aircraft or UAV or RPAS or drone” indicated over 97,186 documents had been published in the twenty-first century (Figure 1). There has been year-on-year growth in published documents since the start of this period. The publication of the research has primarily been through articles (59.8%) and proceedings (36.7%).

Figure 1.

Publication of uncrewed flight research documents.

Befitting a new sector in aviation, many of the documents (39%) are found in the new sector of publishing, open-access journals.

The subjects of most of the publications are centered on technological subjects. A refined search of “Human Factors* and Remotely Piloted Aircraft or UAV or RPAS or drone” in Web of Science identified only 959 documents, less than 1% of the output since 2000. This overwhelming preponderance of publications focusing on the technology of drones is supported by a comprehensive review conducted by Telli et al. [30]. In reviewing the previous three years of research into drones, the authors identified 11 topics that had received most of the attention, all dealing with technical issues.

There are four components to UAS: the actual vehicle (the UAV), the ground control station (GCS), and the link between the previous two components (C2). Overarching these components is the human, providing control and management of the mission and analyzing the collected data. Humans are an integral component of the operating system. With most of the attention being given to the technical development of UAS in research publications, there has not been the same level of attention given to the human component. Despite the lack of research interest, the human element remains in UAS operations. The human component cannot be diminished. The emphasis afforded to technical developments in UAS can enhance the idea that uncrewed flight does not have a human involved in its operation. This is resulting in little effort being devoted to understanding what is required to operate a remotely piloted flight safely. However, the skills and abilities of humans remain an important component of RPAS [31]. This includes how to operate RPAS and the KSaOs required of the human pilot in this new form of aviation activity. Crew qualifications have been identified as an important consideration when integrating UAS into existing aviation structures, even as solutions to integration issues are sought via technology [32].

The use of knowledge, skills, and other attributes as an organizing construct is consistent with established approaches to analyzing human performance and competency requirements in aviation and other safety-critical domains. Human factors research has long emphasized that operational performance emerges from the interaction between individual capabilities, task demands, and system design, rather than from technical capability alone. Within aviation, competency-based models have been widely used to structure training, assessment, and licensing by linking observable performance to underlying cognitive, perceptual, and procedural capabilities.

Rather than adopting a single prescriptive human factors framework, this review draws selectively on concepts that are common across established approaches, including situational awareness, workload management, decision-making, and human–system interaction. This allows findings from diverse methodological traditions to be integrated while maintaining a consistent analytical lens for examining RPAS pilot knowledge, skills, and other attributes in civilian and commercial operations.

The autonomous capabilities of UAS can have the consequence of having the human not always be present for the flying operation. Liu et al. [33] identify the partnership or cooperation required between the different systems of UAS to achieve the desired outcomes of an uncrewed mission. Neither part of the system excludes the other. Unverricht et al. [34] listed the role of automation as control of the aircraft, collision avoidance, and maintaining the flight plan, including staying away from the geo fence. The role of the human is to conduct planning and authorizing of the operation, risk analysis and decision-making, inspection, and monitoring. The two components were seen to be jointly responsible for the recovery of the aircraft.

Along with the lower numbers of research outputs devoted to the human side of RPAS, a further problem is identified when reviewing the literature on RPAS competencies. Most of the research has arisen in military settings [35], with little understanding of the extrapolation or otherwise of the findings to civilian flight. Military operations involve large aircraft of fixed-wing design with teams of personnel to operate the drone [36]. Within civilian operations, the aircraft are often the much smaller rotary wing type of drone operated by a single pilot in Visual Line of Sight (VLOS) of the aircraft, who may or may not have an accompanying observer.

Howse [37] traces the earliest attempt to create a taxonomy of the requisite knowledge and skills required for remote flight, which arose in 1979 and was undertaken by the U.S. Army Research Institute for Behavioral and Social Sciences. From this beginning, further work was undertaken on the topic, although Howse identified methodological issues with most of the studies and highlighted only three as being “rigorous and systematic” (p. 41). Pavlas et al. [38], using the methodology of a review of the literature from the findings of these early studies, built a taxonomy of knowledge and skills for UAV operators. Their purpose was to inform the training of UAV pilots. They identified the knowledge for remote flight focused on two components of the remote system: the human operating the system and the equipment used for the operation. The former was broken down into knowledge of the individual and knowledge of team dynamics. The individual knowledge included fatigue recognition, workload, situational awareness and distractions. The identified skills for operating UAVs centered around monitoring both the aircraft, its flight path and the mission. As most of the early work that was drawn upon by these authors arose from military operations, the skill required to work within a team was also identified. There was one final component of their taxonomy, which was acuity and perception of the participants.

Selection processes, when successful in choosing competent RPAS pilots, can provide an indication of the KSaOs that are likely to be used in UAS operations. Different disciplines have contributed to the devising of varied tests for the selection of candidates to pilot aircraft, especially for the selection of candidates for airline positions and military flying. As an example of the continued interest in selection tests, the International Journal of Aviation Psychology published two special editions devoted to pilot selection, the first in 1996 and the second in 2014. The transferability of existing selection tests to RPAS operations is unknown and clearly worth future investigation.

Lercel and Hupy [39] examined online job descriptions for RPAS pilots and identified six core competencies that were being sought in applicants. Along with the results of a survey of UAS pilots, six competencies were identified: “Leadership, Technical Excellence, Safety and Ethics, Analytical Thinking, Teamwork, and Entrepreneurship” (p. 21). Johnsen et al. [40] explored the cognitive tests that were being devised and used by the Norwegian Police to select RPAS pilots. Current serving police officers who wanted to train to become a certified police RPAS pilot participated in a performance test on a DJI simulator, followed by a selection test. The content of the latter included spatial ability, cognitive capabilities, attention, vigilance, and short-term memory performance. There was a correlation between the performance of the participants and spatial orientation, logical reasoning, and choosing what to pay attention to. Being able to use the selection test to predict the performance of a drone pilot was strongest with spatial and attentional abilities. Apart from this Norwegian example, it has been identified that there are few, if any, UAS-specific selection tests for civilian RPAS pilots [31].

The benefit of playing computer games to enhance the training of conventional crewed flight has long been understood [41,42]. With the operation of a drone appearing to be like video gaming [43], studies have been conducted into understanding the transferability of gaming skills to drone operations. Positive transferability between video gaming and RPA operations could see the recruitment of video game players, shortening training times and alleviating future shortages of skilled drone operators. One of the stereotypes that may need to be overcome to use gaming experience is that of video games being played by social misfits [44].

Different methodologies and subjects have been used in understanding the effect of video game experience on the ability to fly a drone. Triplett [45] used structured interviews with experienced gamers, while Lin et al. [44] used enrolled college students with no flight experience as subjects using a UAV control station. McKinley et al. [43] directly compared experienced pilots and video gamers. The study was aimed at identifying people who could be selected by military operators of UAVs. The 30 participants were divided into three groups of equal numbers. One group consisted of experienced pilots, the second group was of experienced gamers, and the third cohort was the control group. The study found that the experienced pilots were no better than the experienced video game players at simulated landings of a sophisticated drone. On a war game task based on quick response to multiple incoming threats, the gamers performed at a higher standard than the pilots and the control group. The researchers concluded that gaming experience provided an advantage in some of the tasks required to fly an RPA, especially motor control and coordination skills.

Supervising the automation elements of drone in flight and who was suited to this important part of RPA operations was explored by Wheatcroft et al. [46]. The comparison groups were professional pilots, experienced private pilots and experienced video gamers, along with a control group. The participants were tasked with making decisions across different levels of danger. There were similar outcomes between professional pilots and video gamers who were more confident in their decision-making than the other groups. The researchers concluded that potentially suitable candidates for supervising RPA flight might be found in video gamers.

Using the FAA UAS A&I database, Joslin [47] identified situational awareness (SA) as the cause of 13 of the 274 (4.7%) incidents and accidents examined. Navigation issues were the largest contributor to SA occurrences. McCarthy and Teo [48] cite the absence of stimuli as an important consideration in SA not being exhibited by RPA pilots. Wheatcroft et al. [46] identify SA as being of significance because of the lack of shared fate, whereby the non-co-located drone pilot does suffer the consequences of the drone. The pilot may therefore “maneuver the UAV in a more aggressive manner that may increase the likelihood of accidents” (p. 8). McCarthy and Teo [48] further note that SA is not only required for the operation of the drone but also for the design of the components of the UAS. The authors suggested that this finding needed to be considered when planning training for UAS operators. Goldberg [49] recognized the importance of simulation technology in the training of SA for RPAS pilots.

3. Subject Matter Experts

One approach to identifying RPAS pilot KSaOs has been to draw on the expertise of experienced operators and those closely involved in uncrewed operations. Subject matter experts are able to articulate the cognitive, perceptual, and procedural demands of RPAS operations based on direct operational experience, providing insight into how competent performance is understood and enacted in practice.

The number of studies adopting this approach remains relatively small, reflecting both the nascent nature of civilian RPAS operations and the limited pool of operators with extensive experience across diverse operational contexts. As a result, the studies reviewed in this section represent the majority of available empirical work explicitly examining RPAS pilot competencies through expert elicitation. While methodologically diverse, these studies collectively provide the most comprehensive insight currently available into how RPAS pilot KSaOs have been conceptualized and investigated within the literature.

Using subject matter experts, Chappelle et al. [50] sought to cover the gap in knowledge of what the “right stuff” in the areas of cognitive, personality and motivation was for pilots of the military MQ-1 Predator and MQ-9 Reaper drones. Their results identified cognitive factors, including speedy and accurate information processing, ability to divide attention, visual skills, including acuity and perception, spatial skills, memory, reasoning, and fine motor skills. Personal attributes included traits that allowed adaptation to changing environments and the ability to operate within team settings. The motivational domain involved the moral dimension of the person and the ability to fulfill duties as a military officer.

Paullin et al. [51] used a mixed methods approach to identify skills, abilities, and other characteristics (SAOCs) that were required for remote pilot operations. Material from earlier efforts to work out the SAOCs was accessed along with interviews of SMEs. The latter included not only existing UAV pilots in the defense forces of the USA but also staff from the RAF of Great Britain. The purpose was to formulate predictors of who would be a suitable candidate for remote flying, what they called a “best bet” approach to the selection of personnel. The findings of the process were 21 SAOCs grouped around three headings: non-cognitive, abilities, and skills.

After reviewing literature and attending workshops, Lercel and Hupy [39] developed a questionnaire that was sent to 2856 UAS professionals. They were asked to select and rank the top three competencies required by professional UAS pilots. “The four most selected competencies are to be Safety and Quality Focus (81%), Technically and Mechanically Proficient (64%), Operations Acumen (54%), and Data Collection/Processing Acumen (43%)” (p. 19). The authors noted what they describe as a competency gap between what the responding professionals identified as important and what the regulatory body saw as important for RPAS pilots.

In looking to inform research into human–drone interactions, Ljungblad et al. [52] interviewed via video link ten operational professional RPAS pilots from five different countries. A semi-structured format was used for the interviews. This methodology was chosen with the belief that it would generate more qualitative data than survey forms or ethnographic observational studies. Their results identified a divergence between drone usage and drone research. In practice, drones are primarily used for data gathering, while researchers want drones to be seen as actuators. The data-gathering tasks, being industry-specific, highlight that RPAS pilots are not primarily pilots. The RPA is a tool of the trade/profession, and being a pilot is second. As the RPA is used in this manner, Ljungblad et al.’s [52] collation of responses from the ten drone pilots identified pre-flight planning as a large part of operating the RPA. This involved accurate liaison with clients to understand what data they wanted captured. Associated tasks included checking airspace and weather, examining the projected flight path for physical obstacles and potential electronic interference, as well as checking the equipment to be used. These tasks needed to be repeated at the site of the flight. Safety was an important consideration, taking care with by standers and ensuring the link between the ground control station and the drone is maintained. An indication of the RPAS sector being a developing one is evidenced by the respondents, while believing that ongoing training is an important part of flying drones, viewing the resources being accessed for this training as informal. This informal training included online resources such as YouTube as well as accessing more experienced drone operators. A connection with formal training opportunities from sources such as national regulators would appear to be lacking.

Lercel and Andrews [53] used experienced U.S. Army RPA pilots with more than 250 h of flight experience to understand the cognitive task requirements for successful remote operations. A combination of methods was used to undertake an Applied Cognitive Task Analysis (ACTA). Interviews were conducted with the pilots to develop task diagrams. A knowledge audit was conducted to better understand what cognitive skills were being utilized in flight missions. During this process, the pilots were able to describe what expertise they had used when completing their flights. Finally, the expert pilots were presented with simulated missions for them to fly on a simulator. The ACTA identified three major cognitive themes that were important for RPAS operations: “situational awareness, problem solving, and crew resource management” (p. 329).

In Sweden, five working RPAS pilots were chosen as subject matter experts and interviewed by Albihn [54]. Two attributes were identified as being of importance in the flying activities of the interviewees, workload management allied with situational awareness and pre-flight preparation. The former referred to the management of resources and the ability to anticipate when they would need to be used for maintaining safe outcomes. This would entail the development of contingency plans, which the author likened to naturalistic decision-making.

Using a two-step approach, Schmidt et al. [36] sought to identify the key competencies of RPAS using experienced German RPAS pilots. First, focus groups of 19 subject matter experts, pilots, and staff from uncrewed aviation departments of public authorities were established for a list of 38 remote pilot competencies that were either generic to aviation operations or specific to uncrewed operations. These were grouped into five categories: flight skills, theory knowledge, cognitive abilities, personality, and interpersonal skills.

The second step was the formation of a questionnaire based on the 38 competencies. The questionnaire was sent to professional drone pilots, with recreational flyers excluded. Data was analyzed from 88 respondents who had experience in drone flying, ranging from 10 h to over 4000 h (median = 122.5 h). All respondents believed that all 38 competencies were of critical importance, and most were difficult to perform.

According to responses, the competencies were classified as being required to be taught in either initial training or recurrent/refresher training. The competencies identified as belonging to initial training were primarily theoretical knowledge (6 out of 10) and cognitive abilities (5 out of 6). Most of the remaining competencies were seen to belong to recurrent/refresher training. The researchers identified that those competencies dealing with emergency situations were likely to be coded to recurrent/refresher training as they required constant training.

Nwaogu et al. [55] focused on the training needs and competencies of RPAS pilots flying for a specific industry, that of the building industry. The methodology used was a mix of a desk-top investigation of training requirements methods from different regulators, along with interviewing experienced pilots. The online search used Google Chrome. The interviewing process utilized semi-structured interviews with 22 selected interviewees from Hong Kong. Over two-thirds (68.2%) of the interviewees had up to 10 years of drone flying experience in a variety of roles.

The analysis of the interview data indicated that a large majority (85.7%) indicated that the training they had received as a drone pilot had been inadequate. Two problems were identified in the responses provided to the researchers. The first was the lack of specific training for the flying conditions the pilots were going to face in Hong Kong. A large proportion of the training originated in other countries and would often refer to conditions in those countries. The second problem was that it was seen to be operation-specific. The respondents indicated that most of the training concentrated on photography, not on the skills required for operations on building sites. The respondents felt it did not prepare them for the day-to-day challenges they were going to face. The offering of a generic training course was felt to be insufficient. The findings identified the need to also have specialized training in the tasks (e.g., inspection) that the drone pilots were going to have to perform in the construction industry.

The researchers identified that their research had limitations in the range of training courses undertaken by the selected interviewees. However, they could not identify other training courses during the first (desk-top) stage of the research. The research identified the need for the KSaOs to be more than generic and to have specific training for the specific tasks the pilots were going to complete [55]. Generalized competencies are a requirement for all high-reliability operations (HROs) and are found in use across many industries [56], including RPAS operations. However, with the ever-burgeoning number of roles that UAS are used for, there is also the need to identify task-specific KSaOs that can be built upon the foundation of the generic competencies.

4. Accident Taxonomies

While studies drawing on subject matter experts and training research provide insight into required competencies, they do not demonstrate how deficiencies in those competencies manifest during real operations. Analyses of accidents and incidents provide an additional perspective by identifying recurrent failure modes and the human and system factors associated with unintended outcomes. Understanding these failures can therefore inform the identification of RPAS pilot KSaOs required to support safe operations.

The number of studies analyzing RPAS accident and incident data remains limited, particularly in civilian and commercial contexts, reflecting both the relative novelty of widespread RPAS operations and the lack of comprehensive reporting and investigation frameworks. Consequently, the studies reviewed in this section comprise much of the available literature explicitly examining RPAS occurrences from a human factors and competency perspective. Despite variability in data quality and analytical depth, this body of work provides the best available empirical evidence on how deficiencies in RPAS pilot knowledge, skills, and other attributes contribute to unsafe outcomes.

In operational terms, accidents in any form of aviation are expensive, and remote operations are not immune. In a simulation exercise, 10 drone pilots flew 100 missions. The accidents that occurred during these missions led to 6 injuries and 14 instances of damage being done to property, causing over USD 9 million worth of damage [57].

Understanding the cause of accidents can provide insight into the competencies required for safe operation. As researchers have attempted to understand the influence of human failings on the safety of RPAS operations, the use of post-accident data has become more prevalent. While it can be seen as a reactive approach to safe outcomes, what is learnt from previous occurrences can be used to improve future performance. Within aviation, using accident investigation data to understand mistakes and errors has long been used as an approach to improving safe outcomes [58].

Earliest attempts at using an accident taxonomy for learning about RPAS operations applied Wiegmann and Shappell’s [59] now ubiquitous taxonomy, the Human Factors Analysis Classification System (HFACS). This was based on the work of Reason [60] on human error and the Swiss Cheese Model (SCM) of understanding accident causation. The SCM highlighted that causes of accidents were to be found in both front-line operators causing active errors and decision makers who created conditions that contributed to the accident occurrence, i.e., latent conditions; importantly, decision-makers were distant in time and place from the actual accident. The HFACS has four layers. The bottom two are unsafe acts of the operator and the preconditions that lead to unsafe acts, which arise from the domain of active errors. The upper two layers examine the role the management of the organization had in the accident sequence and latent conditions. The HFACS taxonomy has been widely used to identify failings amongst not just aviation operations but other safety-focused industries.

Manning et al. [61] examined U.S. Army RPA accidents up until 2003 using the HFACS taxonomy and the Department of the Army “Army Accident Investigation and Reporting” Methodology. This has causal human factors being categorized as a breakdown in individual, leader, training, support, or standards. Of the 58 accidents studied, 32% of them were categorized according to the different layers of the HFACS. Their analyses found these RPA accidents arose from both individual failings found in the unsafe acts level of the taxonomy and organization issues found in the upper levels, such as unsafe supervision and organizational factors. The Army investigation and reporting taxonomy also found individual errors to be the most common cause of accidents and incidents. The outcome the authors hoped would arise from their study was the establishment of “training programs … to address all of the major causal factor categories, with special attention on the prevention of individual errors or failures” (p. 21).

Using the Department of Defense HFACS, an amended taxonomy, Tvaryanas et al. [62] examined the USA military’s RPAS over a period of 10 years, from 1994–2003. Their findings demonstrated that RPAS mishaps had causation factors in both the actions of the individual pilot and the decisions of the organization. For the United States Air Force (USAF), skill errors and decision-making errors were the largest unsafe acts. While for the Army operators, violations were much larger than they were for both the Air Force and the Navy. Many of the accidents had their antecedents in the organizational and management layers of the HFACS. The decisions being made by the relevant organizations, such as acquisition policies and processes, and including unsafe supervision, contributed to accidents occurring. Further, for the researchers, a “major finding of the study was the predominance of latent failures relatively distant from the mishap at the organizational level” (p. 729).

The finding of aligned pathways between active failures and latent conditions that contributed to RPA occurrences was also identified in another study [61]. This study examined safety occurrences with one RPA type from the USA military, the MQ-1 Predator, from 1996–2005. The DoD HFACS was used for the analysis. Four factors of active errors were linked to one or more latent conditions. Two of these active errors were at the individual level of skill error, perceptual error, and attentional failures. These factors shared common pathways to associated latent conditions. The other two factors arose from errors by individuals when performing in a team environment, e.g., crew resource management failures. The identified associated latent failures with pathways to these four factors were seen by the authors to create two adverse effects. One was “error-provoking conditions” and the second was “the creation of long-lasting holes or weaknesses in mishap defenses” (p. 529).

Taranto [63] examined the differences in accidents of two remotely controlled aircraft in the U.S. military fleet (USAF MQ-1 and USAF MQ-9), which were operated whilst using the same Ground Control Station (GCS). The tool used for the analysis of the accidents was the Department of Defense HFACS. There were 88 accidents between 2006 and 2011 analyzed. The results indicated no difference between the two fleets, and the researcher posited that the human factors that led to accidents were more likely to be caused by the GCS than the aircraft type.

German military RPAS accidents (n = 33) between 2004 and 2014 were analyzed with the use of HFACS [64]. In comparison to an HFACS analysis of conventionally crewed military aircraft conducted at the same time, uncrewed accidents had more technical failures and fewer human factors incidents involved in the accident causation. Of the human factors that led to accidents, all four levels of the taxonomy were represented in the analysis. The preconditions for unsafe acts had the largest number of coded occurrences, followed by unsafe acts. Skill errors and adverse mental states were the two biggest contributors to accidents occurring. Unsafe supervision had the least number of coded accidents.

Wild et al. [65] and Wild et al. [66] used data from several databases from around the world, including the FAA Aviation Safety Information Analysis and Sharing System, the NASA Aviation Safety Reporting System, and the Civil Aviation Authority. Civil occurrences from 2006 to 2015 were selected for analysis. The occurrence reports (n = 152) were analyzed using the ICAO Aviation Occurrence Categories. The largest cause of accidents identified in both studies was equipment failure, with the cruise phase of flight being the setting for most of these failures. The authors identified the difference in accident causation between the uncrewed sector and the traditional crewed sector. The latter sector attributes most accidents to human factors considerations, while human considerations in accidents and incidents of remote operations were not as significant. Wild et al. [65] note the findings lend themselves to the need to improve the technical aspects of RPAS operations. That is, airworthiness of aircraft and the integrity of the communication links, rather than hunting for Human Factors (HFs) failures to improve safety in uncrewed operations. A more recent survey of commercial drone users found that HF was the largest contributor to drone accidents in the workplace [67].

Neff [68] used the HFACS to examine four incidents of large RPA mishap amongst civilian contractors operating for the U.S. Border Patrol or the USAF. A Pareto analysis was conducted to ascertain the top 20% of accident causes. The analysis highlighted that the top four causes of skill error, decision errors, technology environment, and communication, as described by the taxonomy, accounted for 50% of the causes of the accidents. Supervisory influences, i.e., from the upper two levels of the HAFCS, were also found to contribute to the accidents but at lower rates. The researcher’s response to these highest occurring causes was to propose training strategies to mitigate against the most commonly occurring causes of mishaps.

A modified version of the HFACS was applied to RPAS accident data from investigatory bodies across the world, Grindley et al. [69]. This version of the HFACS had a fifth layer added as part of the taxonomy, that of external regulatory factors. This modified version was applied to 77 reports of RPAS accidents. The HFACS analysis found that 26 of the reports had the accident directly caused by or contributed to by a human. Eleven of the reports had the operator reacting incorrectly to a hazardous situation, and the remaining 15 reports were caused by a human who also reacted incorrectly. Decision errors were the most represented item in the first level (unsafe acts) of the HFACS, followed by skill errors. Two actions that were often observed in decisional errors were the pilot disabling automation control of the flight and taking manual control, and task prioritization over following checklists. A relationship was found between the Level 2 (preconditions for unsafe acts) item, the technological environment, and decision errors. Adverse mental state was also a factor contributing to unsafe acts occurring. As with other similar studies in using HFACS to understand civilian RPAS accidents, Grindley et al. [69] did not find a link—described as a “golden thread” (p. 7)—between higher Levels 3 and 4 of the taxonomy and the lower levels of unsafe acts and preconditions for unsafe acts.

While the HFACS taxonomy has been used for post-performance analyses with positive benefits to understanding the skills and abilities required of RPAS pilots, it is a reactive approach. To get ahead of the accident sequence, the HFACS has also been used for predictive risk analysis and the provision of early warning of unsafe acts [70]. A total of 74 occurrences of incidents and accidents from the official Civil Aviation Administration of China and other sites that collected accident data were analyzed. By applying a modified form of HFACS, the authors identified 33 risk factors. Although the research was focused on the actions of the RPAS pilot, risk factors were found at all levels of the HFACS. At the lower levels, risks included unqualified knowledge and skills, and a lack of training and experience. In the upper level of the taxonomy, risks included a lack of an industry safety culture and a lack of supervisory systems.

While HFACS has been the predominant taxonomy used for analyzing RPAS accidents and mishaps due to its ubiquity, it has not been the sole taxonomy used. AcciMap is a tool used in accident causation analysis to identify the actions and decision-making of all participants within sociotechnical systems that lead to accidents. The search for contributory factors can lead to and include government and regulatory levels [70]. The authors contend that the use of HFACS does not allow for depiction of interactions between contributory factors and does not allow for consideration of factors outside the organization.

Using AcciMap, Jackson et al. [71] examined 14 ATSB investigated RPAS accident and incident reports to identify the contributory factors and how their relationships lead to RPAS accidents. The most dominant factor was the failure of equipment. This was central and affected most other parts of the system. The second most influential factor was Activity Work and Operations, which the authors noted provided an emphasis on the effect normal operations play in the safe operation of a system. This is similar to the findings of skill error within HFACS studies. A third factor was compliance with procedures, violations, and unsafe acts. This included “errors (e.g., missing technical safety indicators during set-up) and non-compliance with policy, procedures, and operating limitations” (p. 8). While there were identified links between these contributory factors, the authors believe further work is required to identify links with the highest levels of regulatory authorities.

The use of AcciMaps for accident analyses by Jackson et al. [71] has a somewhat different aim than HFCS, but the outcomes are similar. In AcciMaps, the high preponderance of technical/equipment failure can be highlighted (as previously [65,66]), although overlooked in the HFACS studies, as they lack a direct or immediate human cause at play in RPAS accidents.

All the accident analysis studies identify skill error as a major contributor to those RPAS accidents that had a human-led cause (Table 2). While some studies found links between different levels or contributory factors, further work needs to be undertaken to fully understand the influence of higher levels on accident causation, the “golden thread” of Grindley et al. [69]. Those links between different layers of taxonomies may not yet exist in this fledgling sector of the aviation industry. The search for links may be driven by the expectations raised by accident investigation and analysis in the more established conventionally crewed sector.

Table 2.

Accident analysis studies in the literature indicate the associated methodologies and conclusions.

Table 2.

Accident analysis studies in the literature indicate the associated methodologies and conclusions.

| Ref | Year | Methodology/Taxonomy Used | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|

| [61] | 2004 | HFACS and Army accident investigation and reporting | No single factor was identified. Individual failures are the largest causal factor. |

| [62] | 2006 | DoD HFACS | Latent failures arising from the organization and supervisory levels were the most identified cause of occurrences. |

| [72] | 2008 | Principal Component Analysis (PCA) | Pathways between unsafe acts of the individual and latent conditions are identified. Situation awareness arising from perception issues is identified with more than 50% of occurrences. |

| [63] | 2013 | DoD HFACS | No difference in human failings between aircraft types. |

| [68] | 2016 | HFACS | Skill error, decision errors, technology environment and communication errors contributed to 50% of the analyzed accidents. |

| [65] | 2016 | ICAO Aviation Occurrence Categories | Technology issues are a greater contributor to RPAS occurrences than HF |

| [66] | 2017 | ICAO System Component Failure/Malfunction (SCF) Categories and Contributing Factors | Equipment problems were the largest cause of occurrences, with Human Factors the largest contributor to loss of control during flight. |

| [64] | 2019 | HFACS | Preconditions followed by unsafe acts were the predominant causes of occurrences. |

| [69] | 2024 | Modified HFACS with a fifth layer added | Decision errors, along with associated technological environment and adverse mental state preconditions, contributed to a large proportion of occurrences. Evidence was also found of contributions to occurrences at the remaining higher three levels of taxonomy, but no direct connection between the individual causes and the organization’s causes. |

| [71] | 2025 | AcciMap | Equipment failures were the single largest factor in occurrences, followed by activity work and operations issues. |

5. Data Collection

Civilian RPAS operations are frequently conducted in support of broader professional activities, where successful data collection is often the primary operational objective. Despite the centrality of data acquisition to many RPAS missions, relatively few studies have examined how these task demands shape RPAS pilot knowledge, skills, and other attributes. As a result, the literature discussed in this section represents much of the available work addressing how data-centric mission requirements influence RPAS pilot competencies. In these contexts, effective RPAS operation depends not only on aviation-specific skills but on integrating piloting tasks within broader professional workflows and mission objectives.

Flying safely, following the requisite rules and procedures, is a requirement for RPAS KSaOs, but the collection of data is also an important consideration in understanding RPAS competencies. Being solely a pilot controlling the remote aircraft does not fully encapsulate the role of an RPAS pilot. Respondents to Ljungblad et al. [52] identified in their operational experiences that data collection was of prime importance. Flying a drone was not just about being a pilot, but using the drone to assist in professional tasks. The researchers concluded, “that professional pilots are foremost experts of a specific business and its values—piloting is second” (p. 7). Ensuring the client received the appropriate data was seen by the respondents to Ljungblad et al.’s [52] interviews as the final but still very important requirement of a drone pilot. The cognitive demands on RPA pilots are increased beyond the act of flying. Having to fly and complete the task of the flight (e.g., photography, etc.) calls upon multitasking skills [73].

Understanding the multiple roles required to be filled by an RPAS pilot is a different approach to understanding RPAS error [73]. Within this approach, the error was not in the handling of the aircraft or procedural mistakes but in the lack of accurate and complete data collection required by the purpose of the flight. Early approaches to RPAS safety investigated human error as a safety issue, while this different approach views error as the failure to successfully complete the mission. This perspective on RPAS safety calls attention to the fact that flying an RPA is not just for the sake of flying, as also identified by Ljungblad et al. [52]. There is a reason for the flight being undertaken, e.g., the collection of specific data. Flying an RPAS can be an enjoyable exercise, but for the professional pilot, there is a commercial reason for the flight. Failure to collect meaningful and accurate data is a valid part of RPAS human error. As Murphy et al. [74] summarize, “The use of sUAS should be treated as a data-to-decision system, not a drone control problem or an autonomy problem” (p. 69).

Murphy et al. [74] examined the returned data from 34 flights assessing damage wrought by Hurricane Ian. All but three of the flights had errors in the captured data returned by the pilots. Overall, 51 errors in data collection were identified across these flights. This included data being presented in the wrong format, a required file not being provided, attempting to collect mapping data despite the pilots not having been appropriately trained, and one mission conducted by the RPA pilot was unauthorized. The errors were identified as arising from procedural error—following (or not) protocols for the collection of data, and skill error—flying the drone. The latter were more observed during manual flight. The skill errors were more likely to occur during the initiation phase of the flight when the pilot was required to prepare and configure software. The procedure errors were more often observed in the termination phase, the control, formatting and processing of the collected data. Of the 34 flights with errors, 5 flights had data so badly collected that satisfactory data output could not be achieved. These errors are described as “terminal” [73]. The incidence of flights with errors was split almost equally between manual flights and autonomous flights.

Borowik et al. [75] observed television drone pilots. The purpose of the flight was to obtain video footage while keeping the aircraft clear of obstacles as they recorded footage. The researchers identified that all the subjects spent more time viewing the screen than they did the RPA and the immediate surroundings. The most efficient split in viewing time was 70–80%, not viewing the aircraft. However, as the viewing of the screen increased to 90%, the risk of collision increased.

6. Discussion

6.1. Interpretation of Findings

This review has synthesized evidence from subject matter expert studies, human performance and training research, and accident and incident analyses to identify the knowledge, skills, and other attributes required for safe RPAS operations. Across these different evidence sources, a consistent pattern emerges in which deficiencies in skills and decision-making, often in interaction with technological and operational factors, are associated with unsafe outcomes.

The predominance of skill-based errors and decision errors in accident analyses aligns with findings from subject matter expert studies, which emphasize cognitive workload management, situational awareness, planning, and monitoring as central to competent RPAS performance. At the same time, studies examining training and operational practice highlight variability in how these competencies are developed, assessed, and maintained, particularly in civilian and commercial contexts. Together, these findings suggest that RPAS safety is less constrained by the absence of technical capability than by the alignment between operator competencies, task demands, and system design.

Research into the required competencies of an RPAS pilot has been overshadowed by research into technical subjects. However, from the start of the origins of remotely operated aircraft, there have been efforts to research and understand the KSaOs required of RPAS pilots for safe operations. In the search for these competencies, there have been different approaches undertaken. The benefits of playing video games for producing the skills required to operate RPAS have been one approach. The successful collection of data during a UAS operation has been explored as one of the requirements for successful RPAS operation. Two methodologies that have often been employed have been the analysis of expertise arising from the experience of RPAS pilots, as well as other subject matter experts and the analysis of accident and incident reports.

The use of subject matter experts in experienced pilots has focused on two approaches. The first is interviewing the pilots, and the second goes further by developing surveys which are then promulgated to a wider cohort of RPAS pilots. Despite the secondary use of surveys, the studies using this methodology have often only accessed small numbers of pilots. Accessing small numbers of pilots in a limited range of operations may produce skewed results that are not generalizable across all UAS operations. The experienced pilots used in the research have been both military and civilian pilots. As mentioned earlier, it is not known if military results can be extrapolated to civilian operations.

The results arising from this approach have yet to produce a consistent and common enumeration of KSaOs for RPAS pilots. There has, however, been a realization that the required KSaOs are twofold. The first are foundational KSaOs that are generic for all RPAS pilots, no matter what operations they are conducting. The second set of KSaOs is operation specific. Within these limitations, there remains room for further investigations using this methodology to contribute to the knowledge and understanding of the KSaOs required of RPAS pilots.

The use of accident and incident reports has long been used in aviation to not only understand the causation factors but also to learn what needs to be done in future operations to prevent repeated occurrences.

One of the issues facing the methodology of analyzing accident and incident reports for safety improvements amongst RPAS pilots is the lack of quality, fully investigated reports into civilian RPAS occurrences. The in-depth analysis into RPA mishaps conducted by military researchers and the ability to identify latent failures were made possible by the detail contained in the investigation reports. This is not always available to researchers wanting to analyze non-military RPAS occurrences. The databases of civilian incidents and accidents contain few fully investigated accidents and often rely on pilot reports. That is, if the RPAS pilots do actually report occurrences. The inadequacy of regulations—which were designed for investigation into traditional crewed aviation—for UAS operations and the lack of harmonization across different regulatory regimes have been identified as leading to the lack of adequate reports [75]. A second issue is the lack of reporting culture amongst RPAS operators [76]. These factors hinder the development of reports that allow for the identification of causes of accidents, which in turn impedes the understanding of what knowledge and skills need to be improved amongst RPAS pilots.

The most used taxonomy to analyze the occurrence reports was the HFACS and associated derivations. The SCM underpins HFACS understanding that accidents are caused by a combination of active error from the front-line operator and latent conditions arising from people not proximally in distance and/or time. Studies analyzing RPAS occurrences using HFACS suggest that while this combination of active and latent can be found in the highly structured sectors of RPAS operations (military [62,72]), it has yet to develop in civilian RPAS operations. The studies analyzing non-military occurrences identified the occurrence causal factors as coming from the bottom two levels of the taxonomy. These levels identify accidents and incidents arising from the performance of the individual operating the aircraft and the preconditions that contribute to the skill errors. The skill levels of the RPAS pilot have been identified as the most common causal factor. A link between the organization and the individual being causal in the accident sequence has not been found in the analysis of the occurrence reports. The new sector of uncrewed operations in the aviation industry is staffed by newcomers to aviation who are yet to fully enter current aviation cultures. One jurisdiction viewed drones as a parallel subindustry [54]. The nascent nature of commercial RPAS reflects their frequent use as tools by non-aviation professionals to support broader professional activities. As a result, the organizational structures that have developed around commercial and general aviation have yet to form around RPAS operations. Searching beyond active errors for latent conditions that contribute to RPAS accident causation may be fruitless, as it is searching for something that does not yet exist.

An important theme emerging from the review is that many civilian RPAS pilots are professionals first and pilots second, with uncrewed aircraft operating as tools in support of broader occupational activities such as inspection, surveying, emergency response, or media production. This operational reality has implications for how RPAS pilot competencies are conceptualized, developed, and assessed. In such contexts, aviation-related knowledge and skills represent only one component of overall task performance and may be subordinated to mission objectives associated with the pilot’s primary professional role.

This dual-role structure challenges traditional aviation competency models, which assume that flight safety is the primary organizing principle of training and operational decision-making. For RPAS operations, errors may arise not only from deficiencies in aviation knowledge or skills, but from interactions between mission-driven decision-making and safety-critical constraints. Distinguishing between mission errors and safety errors, therefore, becomes less clear-cut, particularly where commercial or professional pressures influence risk perception, workload allocation, and task prioritization. These findings suggest that RPAS training and competency frameworks must account for the integration of aviation skills within broader professional workflows, rather than treating RPAS piloting as an isolated aviation task.

6.2. Future Research Directions

The current taxonomies being used for the analyses have been developed for conventionally crewed operations. As more data becomes available, there may be the opportunity to develop unique, specific RPAS taxonomies that are more applicable for UAS operations. Despite these limitations, as accident report databases grow, the option to contribute to the knowledge of RPAS KSaOs using an analysis of these reports increases.

Building on these observations, several targeted directions for future research are identified:

- Further development and validation of RPAS-specific accident and incident taxonomies that reflect the operational realities of uncrewed aviation, rather than relying solely on frameworks developed for conventionally crewed aircraft.

- Empirical studies examining whether the foundational and operation-specific KSaOs identified through subject matter expert research are predictive of accident and incident involvement in civilian RPAS operations.

- Investigation of the transferability of KSaOs identified in military RPAS research to civilian and commercial contexts, particularly given differences in organizational structure, training regimes, and operational oversight.

- Expansion of research examining task-specific competencies associated with civilian RPAS operations, including data acquisition, mission planning, and post-flight data handling, recognizing that RPAS are frequently operated as tools supporting non-aviation professional activities.

- Improved reporting and investigation practices for civilian RPAS occurrences, including regulatory harmonization and the development of reporting cultures that support learning rather than attribution of blame.

- Longitudinal studies tracking the development and degradation of RPAS pilot knowledge and skills over time, particularly as levels of automation and system autonomy increase.

Addressing these research directions would support the development of more robust competency frameworks and training standards for RPAS pilots. This would enable closer alignment between regulatory requirements, operational practice, and the knowledge, skills, and other attributes required for safe RPAS operations.

6.3. Practical Implications and Mitigation Measures

The findings of this review also have practical implications for RPAS operators, training organizations, and regulatory authorities. Across the studies reviewed, unsafe outcomes in RPAS operations are most frequently associated with deficiencies in operator skills and decision-making, often in interaction with technological, organizational, and task-specific factors. These findings suggest that improvements in RPAS safety are likely to be achieved not solely through advances in platform capability, but through closer alignment between operator competencies, training practices, and the operational environments in which RPAS are employed.

Based on the synthesis presented in this review, several practical mitigation measures are identified:

- Greater emphasis on competency-based training frameworks that explicitly target cognitive and decision-making skills, rather than focusing predominantly on platform operation and regulatory knowledge.

- Increased use of scenario-based and recurrent training addressing abnormal and emergency situations, reflecting the predominance of skill-based and decision errors identified in accident and incident analyses.

- Incorporation of task-specific training modules aligned with the operational contexts in which RPAS are employed, particularly for inspection, surveillance, and data-collection roles where mission success depends on more than aircraft handling alone.

- Consideration of human–system interaction factors, including automation supervision, interface design, and workload management, as integral components of both training design and operational approval processes.

- Use of accident and incident data to inform the continuous refinement of training syllabi and competency standards, supporting a learning-oriented approach to RPAS safety rather than treating occurrences as isolated events.

Together, these measures highlight the importance of viewing RPAS safety as an emergent property of the interaction between operator competencies, system design, and operational context. Addressing these factors in an integrated manner offers a practical pathway to reducing accident risk and supporting the safe expansion of civilian and commercial RPAS operations.

7. Conclusions

This review has consolidated research addressing RPAS pilot knowledge, skills, and other attributes across multiple evidence sources. By synthesizing findings from expert practice, human performance research, and accident analyses, the review highlights the central role of cognitive and decision-making competencies in supporting safe RPAS operations. The findings underscore the need for competency frameworks, training practices, and regulatory approaches that reflect the operational realities of contemporary civilian and commercial RPAS use.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.M.; formal analysis, J.M.; investigation, J.M.; resources, J.M.; data curation, G.W.; writing—original draft preparation, J.M. and G.W.; writing—review and editing, G.W.; visualization, G.W.; supervision, G.W.; project administration, G.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program (RTP) Scholarship.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Müller, O. “An Eye Turned into a Weapon”: A Philosophical Investigation of Remote Controlled, Automated, and Autonomous Drone Warfare. Philos. Technol. 2021, 34, 875–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bareis, J.; Bächle, T.C. The Realities of Autonomous Weapons: Hedging a Hybrid Space of Fact and Fiction. In The Realities of Autonomous Weapons; Bächle, T.C., Bareis, J., Eds.; Bristol University Press: Bristol, UK, 2025; pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Truog, S.; Maxim, L.; Matemba, C.; Blauvelt, C.; Ngwira, H.; Makaya, A.; Moreira, S.; Lawrence, E.; Ailstock, G.; Weitz, A.; et al. Insights Before Flights: How Community Perceptions Can Make or Break Medical Drone Deliveries. Drones 2020, 4, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wild, G. Urban Aviation: The Future Aerospace Transportation System for Intercity and Intracity Mobility. Urban Sci. 2024, 8, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Y.; Pongsakornsathien, N.; Gardi, A.; Sabatini, R.; Kistan, T.; Ezer, N.; Bursch, D.J. Adaptive Human-Robot Interactions for Multiple Unmanned Aerial Vehicles. Robotics 2021, 10, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wild, G.; Nanyonga, A.; Iqbal, A.; Bano, S.; Somerville, A.; Pollock, L. Lightweight and mobile artificial intelligence and immersive technologies in aviation. Vis. Comput. Ind. Biomed. Art 2025, 8, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmeseiry, N.; Alshaer, N.; Ismail, T. A Detailed Survey and Future Directions of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) with Potential Applications. Aerospace 2021, 8, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiets, I.; Kuo, Y.-W.; La, J.; Yeun, R.C.K.; Verhagen, W. Future Trends in UAV Applications in the Australian Market. Aerospace 2023, 10, 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panov, I.; Ul Haq, A. A Critical Review of Information Provision for U-Space Traffic Autonomous Guidance. Aerospace 2024, 11, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.-C.; Lin, C.-L.; Chen, Y.-Y.; Cheng, H.-H. Quadcopter Drone for Vision-Based Autonomous Target Following. Aerospace 2023, 10, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrence, B.S.; Nelson, B.; Thomas, G.F.; Nesmith, B.L.; Williams, K.W. Annotated Bibliography (1990–2019): Knowledge, Skills, and Tests for Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS) Air Carrier Operations; FAA: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; p. 57233. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, C.; Liu, S.; Wanyan, X.; Ding, M.; Li, D.; Zhou, Y. Research progress on key technologies for human factors design of unmanned aircraft systems. Hangkong Xuebao/Acta Aeronaut. Astronaut. Sin. 2025, 46, 531213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Hou, J.; Liu, S.; Wanyan, X.; Ding, M.; Li, H.; Yan, D.; Bie, D. Key Technology for Human-System Integration of Unmanned Aircraft Systems in Urban Air Transportation. Drones 2025, 9, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Lei, R. Progress and prospect of forest fire monitoring based on the multi-source remote sensing data. Natl. Remote Sens. Bull. 2024, 28, 1854–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwaogu, J.M.; Yang, Y.; Chan, A.P.C.; Chi, H.L. Application of drones in the architecture, engineering, and construction (AEC) industry. Autom. Constr. 2023, 150, 104827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.; Huang, L.; You, X.; Wang, P.; Francis, G.; Proctor, R.W. The black hole illusion: A neglected source of aviation accidents. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2022, 87, 103235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goessens, S.; Mueller, C.; Latteur, P. Feasibility study for drone-based masonry construction of real-scale structures. Autom. Constr. 2018, 94, 458–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Y.; Gardi, A.; Sabatini, R.; Ramasamy, S.; Kistan, T.; Ezer, N.; Vince, J.; Bolia, R. Avionics Human-Machine Interfaces and Interactions for Manned and Unmanned Aircraft. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2018, 102, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hocraffer, A.; Nam, C.S. A meta-analysis of human-system interfaces in unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) swarm management. Appl. Ergon. 2017, 58, 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontaine, O.; Martinetti, A.; Michaelides-Mateou, S. Remote pilot aircraft system (RPAS): Just culture, human factors and learnt lessons. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2016, 53, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rash, C.E.; LeDuc, P.A.; Manning, S.D. Human Factors in U.S. Military Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Accidents. In Advances in Human Performance and Cognitive Engineering Research; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2006; Volume 7, pp. 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeJoode, J.A.; Cooke, N.J.; Shope, S.M.; Pedersen, H.K. Guiding the Design of a Deployable UAV Operations Cell. In Advances in Human Performance and Cognitive Engineering Research; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2006; Volume 7, pp. 311–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, M.J.; Hunn, B.P.; Pomranky, R.A. Modeling and Operator Simulations for Early Development of Army Unmanned Vehicles: Methods and Results. In Advances in Human Performance and Cognitive Engineering Research; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2006; Volume 7, pp. 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, H.K.; Cooke, N.J.; Pringle, H.; Connor, O. UAV Human Factors: Operator Perspectives. In Advances in Human Performance and Cognitive Engineering Research; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2006; Volume 7, pp. 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouloua, M.; Gilson, R.; Hancock, P. Human-centered design of unmanned aerial vehicles. Ergon. Des. 2003, 11, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J.R. UAVs and the human factor. Aerosp. Am. 2002, 40, 54–57. [Google Scholar]

- Bartsch, R.; Coyne, J.; Gray, K. Drones in Society: Exploring the Strange New World of Unmanned Aircraft; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Macpherson, E. Is the World Ready for Drones? Air Space Law 2018, 43, 149–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariante, G.; Del Core, G. Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UASs): Current State, Emerging Technologies, and Future Trends. Drones 2025, 9, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telli, K.; Kraa, O.; Himeur, Y.; Ouamane, A.; Boumehraz, M.; Atalla, S.; Mansoor, W. A Comprehensive Review of Recent Research Trends on Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs). Systems 2023, 11, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramallo-Luna, M.A.; Gonzalez-Torre, S.; Rodríguez-Mora, Á.; de la Torre, G.G. Neurocognitive factors of new drone Pilots: Identifying candidates with expert potential. Comput. Hum. Behav. Rep. 2025, 19, 100705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirot, A. The future of unmanned aircraft systems pilot qualification. J. Aviat. Aerosp. Educ. Res. 2013, 22, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Liu, J.; Chen, Z.; Brümmer, M. A Monument Digital Reconstruction Experiment Based on the Human UAV Cooperation. In Proceedings of the AIAA SCITECH 2023 Forum, National Harbor, MD, USA, 23–27 January 2023; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics: Reston, VA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Unverricht, J.; Chancey, E.T.; Politowicz, M.S.; Buck, B.K.; Geuther, S.; Ballard, K. Where is the Human-in-the-Loop? Human Factors Analysis of Extended Visual Line of Sight Unmanned Aerial System Operations within a Remote Operations Environment. In Proceedings of the AIAA SCITECH 2023 Forum, National Harbor, MD, USA, 23–27 January 2023; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics: Reston, VA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- De la Torre, G.G.; Ramallo, M.A.; Cervantes, E. Workload perception in drone flight training simulators. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 64, 449–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, R.; Schadow, J.; Eißfeldt, H.; Pecena, Y. Insights on Remote Pilot Competences and Training Needs of Civil Drone Pilots. Transp. Res. Procedia 2022, 66, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howse, W.R. Knowledge, Skills, Abilities, and Other Characteristics for Remotely Piloted Aircraft Pilots and Operators; Air Force Personnel Center: Randolph AFB, TX, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Pavlas, D.; Burke, C.S.; Fiore, S.M.; Salas, E.; Jensen, R.; Fu, D. Enhancing Unmanned Aerial System Training: A Taxonomy of Knowledge, Skills, Attitudes, and Methods. Proc. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. Annu. Meet. 2009, 53, 1903–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lercel, D.J.; Hupy, J.P. Developing a competency learning model for students of unmanned aerial systems. Coll. Aviat. Rev. Int. 2020, 38, 12–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnsen, B.H.; Nilsen, A.A.; Hystad, S.W.; Grytting, E.; Ronge, J.L.; Rostad, S.; Öhman, P.H.; Overland, A.J. Selection of Norwegian police drone operators: An evaluation of selected cognitive tests from “The Vienna Test System”. Police Pract. Res. 2024, 25, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopher, D.; Well, M.; Bareket, T. Transfer of Skill from a Computer Game Trainer to Flight. Hum. Factors 1994, 36, 387–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopher, D.; Weil, M.; Bareket, T. Transfer of skill from a computer game trainer to flight. In Simulation in Aviation Training; Jentsch, F., Curtis, M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 97–115. [Google Scholar]

- McKinley, R.A.; McIntire, L.K.; Funke, M.A. Operator Selection for Unmanned Aerial Systems: Comparing Video Game Players and Pilots. Aviat. Space Environ. Med. 2011, 82, 635–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.; Wohleber, R.; Matthews, G.; Chiu, P.; Calhoun, G.; Ruff, H.; Funke, G. Video Game Experience and Gender as Predictors of Performance and Stress During Supervisory Control of Multiple Unmanned Aerial Vehicles. Proc. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. Annu. Meet. 2015, 59, 746–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triplett, J.E. The Effects of Commercial Video Game Playing: A Comparison of Skills and Abilities for the Predator UAV. Master’s Dissertation, Department of Systems and Engineering Management, AFIT, Dayton, OH, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wheatcroft, J.M.; Jump, M.; Breckell, A.L.; Adams-White, J. Unmanned aerial systems (UAS) operators’ accuracy and confidence of decisions: Professional pilots or video game players? Cogent Psych. 2017, 4, 1327628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]