Abstract

This study systematically investigates the effects of manufacturing errors on the drag reduction performance of micro-grooves fabricated using roll-to-roll hot embossing technology. Numerical simulations were conducted to analyze the drag reduction characteristics of spanwise micro-grooves under a 0.4 Ma incoming flow, with a focus on the influence mechanisms of groove array straightness error (δ) and bottom corner rounding error (σ) on aerodynamic performance. The results indicate that straightness errors induce periodic pressure pulsations, which disrupt large-scale turbulent structures and lead to a linear degradation in drag reduction performance. In contrast, bottom corner rounding errors modulate small-scale turbulence by altering the local curvature at the groove bottom. Positive deviations in particular cause an upward shift of the vortex core and enhanced energy dissipation, significantly impairing drag reduction. Based on these findings, an optimized processing window is proposed, recommending that the straightness error δ and bottom corner rounding error σ be controlled within −4% to 2% and −20% to 4%, respectively. Under these conditions, the fluctuation in the drag reduction rate can be confined within 20%. This study provides important theoretical insights and practical guidance for the precision manufacturing of drag-reducing micro-groove surfaces on aircraft.

1. Introduction

The aviation field stands as one of the pioneering domains in aerodynamic drag research, where reducing aerodynamic resistance plays a crucial role in enhancing aircraft endurance and flight speed [1]. Surface microstructure design and fabrication on components such as wings and fuselages represents one of the primary approaches for drag reduction, demonstrating potential fuel efficiency improvements of 10–20%. This advancement significantly extends flight range and operational capabilities, thereby promoting greener and more efficient development in aviation [2]. The roll-to-roll hot embossing process represents a micro-manufacturing technique that is straightforward to implement and relatively low-cost, offering favorable replication fidelity [3,4]. This technique functions by transferring the structural features of a master mold onto a polymer substrate [5]. This method proves particularly well-suited for large-scale production of polymer components with microstructure arrays in aerospace applications [6,7]. However, during continuous fabrication of large-area micro-groove structures, manufacturing deviations are practically inevitable, resulting in actual groove morphology that diverges from designed parameters.

The actual forming quality of micro-grooves in roll-to-roll hot embossing processes critically depends on the precise control of process parameters. Studies have shown that the thermal properties of the film material, embossing temperature, feed rate, and roller pressure collectively govern the flow and cavity-filling behavior of the polymer within the mold, thereby determining the final geometric fidelity of the grooves. For instance, when the embossing temperature exceeds the glass transition temperature of the polymer, excessive softening may occur, leading to pattern adhesion or even structural collapse; conversely, insufficient temperature can result in incomplete filling, significantly increasing geometric deviations. Similarly, an excessively high feed rate restricts the flow time of the polymer within the grooves, thereby inducing forming defects, while an overly low rate—although favorable for morphological replication—substantially reduces production efficiency. Relevant studies further confirm the decisive influence of process parameters on film forming quality. For example, Yun et al. [8] computationally elucidated the work hardening and strain softening effects induced by processing speed, providing guidance to avoid dimensional errors and incomplete filling caused by improper temperature settings; Altuncu et al. [9] demonstrated that increased line speed reduces the thickness, tensile strength, and elongation at break of polyethylene films; Jacobo-Martín et al. [10] established a correlation between feed speed and the optical-mechanical properties of PMMA films. Consequently, during large-area continuous forming, micro-groove geometries inevitably deviate from their ideal designs.

Current aerodynamic drag reduction research is predominantly based on idealized groove geometries, forming a comprehensive research framework spanning from bio-inspired design to mechanistic interpretation. In terms of bio-inspired structures, shark skin riblets demonstrate significant advantages: Guo et al. [11] arranged shark skin denticle structures on a NACA0012 airfoil to investigate their drag reduction effects; Bixler et al. [12] systematically studied the geometric configuration, distribution patterns, and interaction mechanisms of riblet structures with flow fields; Domel et al. [13] notably improved airfoil aerodynamic performance through shark skin-inspired surface structures. Other bio-inspired designs include flexible grooves based on dolphin skin [14,15] and studies on the differential performance of regular triangular and rectangular grooves in turbulence modulation. For instance, Selvanose et al. [16] achieved drag reduction using triangular riblets on a NACA2412 airfoil; Song et al. [17] designed drag-reducing triangular grooves inspired by dune morphology; Li et al. [18] significantly enhanced the lift-to-drag ratio of an airfoil through triangular grooves. In parametric optimization, researchers have conducted in-depth investigations focusing on groove depth. Wong et al. [19] proposed a viscous vortex model to predict the optimal drag reduction for triangular and rectangular grooves at different heights; Li et al. [20] described the relationship between dimensionless depth and drag reduction rate, solving for optimal depths across various Reynolds numbers; Tirandazi et al. [21] identified the aspect ratio as a critical parameter in optimizing the drag reduction effectiveness of rectangular grooves. Additionally, other geometric parameters such as width [22], inclination angle [23], and spacing [24,25] have been extensively studied to achieve optimal drag reduction under varying Reynolds number conditions. At the mechanistic level, several theoretical models have been proposed to explain the drag reduction mechanisms of micro-grooves, including the protrusion height-based regulation theory [26,27], the secondary vortex restructuring theory emphasizing the reorganization of near-wall vortical structures [28,29], and the conceptual framework treating grooves as “micro-scale air bearings” [30,31]. These theories provide an important foundation for understanding the turbulence modulation mechanisms of idealized groove structures. However, most existing studies rely on strictly idealized geometric assumptions, with limited attention paid to the inevitable morphological errors introduced during actual manufacturing processes. Only a few studies indicate that manufacturing defects, such as groove tip rounding, can degrade drag reduction performance [32,33]. In practice, process-induced geometric deviations may significantly alter near-wall flow structures, thereby weakening or even negating the intended drag reduction mechanisms. This gap between theoretical models and practical implementation represents a critical bottleneck hindering the engineering application of micro-groove drag reduction technologies.

To address this research gap, the present study employs numerical simulations using ANSYS software(v2022 R1) to systematically investigate the effects of two types of geometric errors—array straightness and bottom corner rounding of spanwise micro-grooves—on drag reduction performance under flow conditions of Mach 0.4 and 0° angle of attack. Through comparative analysis of flow field parameters including pressure distribution, velocity fields, turbulence characteristics, and vortex structures, the underlying mechanisms by which different geometric errors influence the groove flow field are elucidated. Furthermore, the study establishes allowable tolerance ranges for manufacturing errors in different regions of micro-grooves fabricated via roll-to-roll hot embossing technology.

2. Numerical Simulation Methodology

2.1. Geometric Model and Error Definition

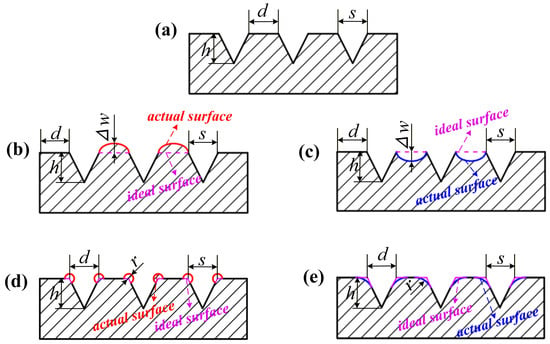

Based on previous studies, a depth-to-width ratio of h/s ≈ 1 has been identified as optimal for micro-groove drag reduction. Accordingly, within the context of aircraft surface drag reduction, this study adopts a groove configuration with height h = 100 μm, width s = 100 μm, straight segment length d = 100 μm, and inclination angle θ = 53.14° as the standard geometry, which has been widely recognized as a typical reference configuration [34]. A schematic diagram of the specific geometric morphology is shown in Figure 1a.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagrams of typical geometric errors: (a) Standard geometry; (b) Positive deviation of array straightness; (c) Negative deviation of array straightness; (d) Positive deviation of bottom corner fillet; (e) Negative deviation of bottom corner rounding deviation.

During the fabrication of micro-grooves via roll-to-roll hot embossing, two types of processing deviations-array straightness error and bottom corner rounding error-typically occur due to limitations in process precision and forming conditions. This study systematically defines these characteristic errors as follows:

Typical Error 1: As shown in Figure 1b,c, the array straightness error rate δ is defined as the ratio of the maximum deviation Δw from the ideal straight line to the straight segment length d, expressed as

;

Typical Error 2: As shown in Figure 1d,e, the bottom corner rounding error rate σ is defined as the ratio of the fillet radius r formed at the groove bottom to the groove height h, expressed as

.

In the above definitions, positive and negative values correspond to upper and lower deviations, respectively. Existing studies indicate that the manufacturing error of small-area micro-grooves fabricated by hot embossing is approximately 3% [35]. However, for the large-area micro-groove structures investigated in this study, the processing errors are expected to increase to approximately 20% due to influences from factors such as tension, temperature, and mold conditions. This study is dedicated to quantifying the direct impact of manufacturing geometric errors on drag reduction performance, with all error parameters defined directly in physical dimensions. Although fundamental turbulence research often employs viscous scaling based on friction velocity to normalize roughness parameters for universal comparison, the present work adopts a different analytical framework oriented toward engineering applications. Quality control in manufacturing relies on physically measurable dimensions, and using the same scale facilitates engineering translation. Furthermore, as friction velocity is a flow response variable, its use in normalizing input parameters introduces a circular dependency in causal logic, obscuring the independent engineering significance of the errors. Therefore, this study aims to establish a direct mapping relationship between manufacturing geometric deviations and drag reduction performance. The resulting error thresholds are presented in the form of manufacturable and measurable physical parameters, providing direct guidelines for the design and process specifications of micro-grooves.

2.2. Computational Model and Boundary Conditions

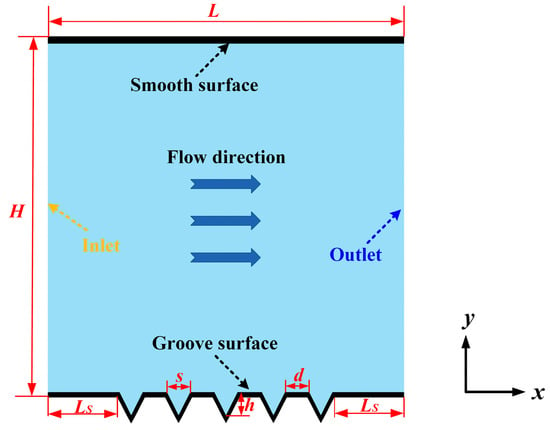

As shown in Figure 2, a two-dimensional model is employed for numerical simulation in this study. To better approximate real-world conditions, the overall length L and height H of the computational domain are both set to 1500 μm. The upper and lower boundaries represent a smooth surface and a surface with periodic V-shaped grooves, respectively. Five spanwise groove periods are arranged perpendicular to the main flow direction along the lower surface. The left and right boundaries are designated as velocity inlet and pressure outlet, respectively, to simulate unidirectional flow within the domain, with air serving as the working fluid. To ensure that the airflow reaches a fully developed turbulent state before encountering the micro-grooves, the distances from the inlet and outlet boundaries to the groove region, denoted as Ls are set to 300 μm. The specific boundary conditions are configured as follows:

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the computational domain.

- (a)

- The computational domain employed symmetry boundary conditions, with both the top and bottom walls set as no-slip walls. The inlet was prescribed as a velocity inlet, while the outlet was defined as a pressure outlet. The initial turbulence intensity and turbulence viscosity ratio were set to 5% and 10, respectively, utilizing default settings for all other parameters.

- (b)

- The top and bottom walls were designated as the “Smooth surface” and “Groove surface,”, respectively. A roughness model was applied to the Groove surface to account for microscopic roughness effects, with a specified roughness height kS of 0.0032 mm, satisfying the applicability condition kS < h. To mitigate boundary effects and approximate real flow conditions more closely, both walls were configured with surface resistance coefficients and drag force options, thereby facilitating subsequent calculation of the groove drag reduction rate.

- (c)

- In this study, air is adopted as the working fluid within the computational domain and treated as incompressible for the simulation. All simulations are conducted under standard atmospheric pressure. The physical properties of air, including density and kinematic viscosity, are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Fluid medium parameters.

Table 1. Fluid medium parameters.

2.3. Mesh Generation

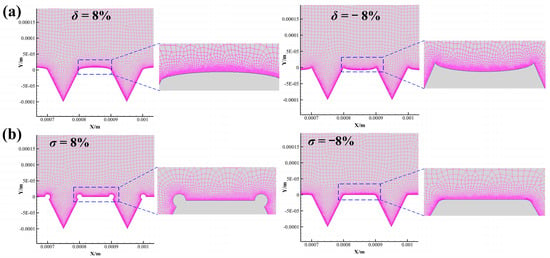

Taking two typical error types with an error rate of ±8% as examples, the mesh configurations for each computational model are illustrated in Figure 3. An unstructured mesh generation approach was adopted in this study to better capture the flow characteristics within the turbulent boundary layer and to facilitate the comparison of drag forces and drag coefficients between the upper and lower surfaces. To evaluate the differences in drag reduction performance of micro-grooves under each typical error type, mesh refinement was applied to both the grooved and smooth surfaces, resulting in the generation of boundary layer grids. The boundary layer mesh cell size was set to 5.0 × 10−7 m. In regions farther away from the micro-groove near-wall area, a coarser mesh was employed to reduce computational cost, with a mesh size of 10−5 m applied in other areas. The overall boundary layer consisted of 2 layers with a growth rate of 1.2, and the physics preference was configured for CFD (Computational Fluid Dynamics).

Figure 3.

Grid division of each model with an error rate of ±8%: (a) Array straightness deviation; (b) Bottom corner rounding deviation.

2.4. Turbulence Model and Solution Method

The Reynolds number for the computational model of the micro-grooves is calculated according to the following formula [17]:

In this equation,

represents the fluid velocity (m/s),

denotes the characteristic length (m), and

stands for the kinematic viscosity coefficient (m2/s). This parameter is employed to characterize the turbulence regime of the flow and serves as an operational identifier in the current study.

In this study, the working fluid is air, which is treated as incompressible. Although flows at a Mach number of 0.4 exhibit slight compressibility, the associated density variation is negligible. Therefore, the incompressible Navier–Stokes equations were solved using ANSYS Fluent(v2022 R1) to simplify the computations [30]. The Reynolds number (Re) was calculated using Equation (1). For engineering applications, the critical Reynolds number (Rec) is typically taken as 2300. Since Re>>Rec, the SST k-ω turbulence model was ultimately selected. Here, SST denotes Shear Stress Transport, while k and ω represent the turbulent kinetic energy and specific dissipation rate, respectively. The SST k-ω turbulence model adopted in this study has been successfully employed by numerous researchers for the numerical simulation of drag reduction by V-shaped grooves [36]. This demonstrates its capability to capture near-wall turbulence anisotropy and vortex structures induced by grooves. The drag reduction trends and flow-field characteristics presented in this work are consistent with those reported in these previous studies. The SST k-ω turbulence model primarily comprises the following two transport equations:

Transport Equation for Turbulent Kinetic Energy (k):

Transport Equation for the Specific Dissipation Rate (ω):

In these equations,

is the fluid density;

is the dynamic viscosity;

is the turbulent viscosity;

denotes the production term of turbulent kinetic energy; and

is the blending function, used for transitioning between regions. The model constants are assigned the following values:

,

,

,

, and

.

To resolve detailed flow field characteristics, the governing equations were discretized using the finite volume method in this study. For spatial discretization, the pressure term was handled with the PRESTO! scheme, while the governing equations for momentum, turbulent kinetic energy, and specific dissipation rate were discretized using the Second Order Upwind scheme. The pressure-velocity coupling was resolved via the SIMPLEC algorithm, with the convergence criterion set to 10−5. The SIMPLEC algorithm is effective in accounting for slight compressibility effects and maintains computational stability and accuracy, particularly at relatively low flow velocities. During the calculation, the drag coefficients and drag forces on both the smooth and grooved surfaces were monitored to assess whether the flow field had reached a converged state.

2.5. Grid Independence and Flow Development Verification

To ensure that the near-wall grid resolution meets the requirements of the selected turbulence model, the target height of the first mesh layer was estimated theoretically prior to grid generation. The simulations employ the SST k-ω turbulence model in conjunction with enhanced wall treatment, with the aim of keeping the dimensionless wall distance

below 1 in order to accurately resolve the viscous sublayer.

Based on turbulent flat-plate boundary layer theory, the target height of the first grid layer

is determined by the following expression:

where

is the dimensionless wall distance;

is the kinematic viscosity of the fluid (m2/s); and

is the friction velocity (m/s).

The friction velocity is related to both the incoming flow conditions and wall friction, and its expression is given by:

In the equation,

denotes the characteristic freestream velocity (m/s), and

represents the local skin friction coefficient.

For the flow conditions considered in this simulation, the Reynolds number based on the characteristic length

falls within the turbulent regime. The local skin friction coefficient

is preliminarily estimated using the Schlichting empirical correlation applicable to smooth flat plates [20]:

where

is the Reynolds number based on the characteristic length

, and

denotes the representative length scale (m) governing boundary layer development within the flow domain.

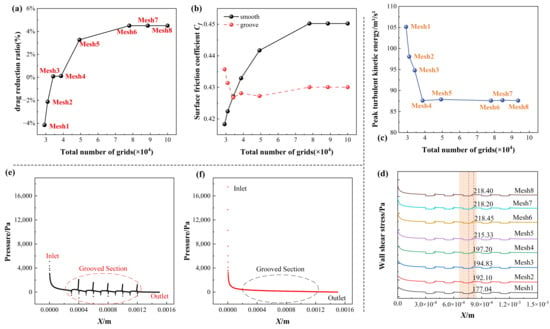

Taking the baseline operating condition (flow velocity of 0.4 Ma) as an example, the drag reduction rate of the grooved surface (Figure 4a) and the drag coefficient (Figure 4b) were selected as evaluation metrics to compare computational results obtained from eight different grid resolutions. The specific grid schemes and corresponding convergence analysis results are presented in Table 2. From Mesh1 to Mesh8, as the grid is progressively refined, the total number of computational cells increases accordingly, while the variation in the drag reduction rate gradually decreases. Specifically, the rate of change in the drag reduction rate for Mesh6 is only 4.50%, indicating that this physical quantity has essentially achieved convergence. To further validate the grid convergence of key flow parameters, the grid dependence of both the streamwise distribution of wall shear stress and the peak turbulent kinetic energy (TKE) was analyzed. Figure 4c shows that the wall shear stress distributions tend to align as the grid is refined. For Mesh6 and finer grids, the variation in the peak wall shear stress along the grooves falls below 1%, demonstrating that the current grid resolution is sufficiently fine to capture near-wall flow characteristics. Figure 4d reveals a similar convergence trend for the peak TKE with grid refinement, with its value remaining essentially stable from Mesh6 onward, further confirming the convergence of key flow-field parameters. In summary, all subsequent numerical simulations in this study were performed using Mesh6, which contains a total of 7.80 × 104 cells, incorporates three layers of boundary-layer mesh, and maintains an average dimensionless wall distance (

) of 0.21.

Figure 4.

Grid partitioning independence verification: (a) Drag reduction ratio; (b) Surface resistance coefficient; (c) Wall shear stress distribution along the flow direction; (d) Peak turbulent kinetic energy; (e) Pressure distribution along the groove surface; (f) Pressure distribution along the smooth surface.

Table 2.

Parameters for each mesh configuration.

The numerical simulations in this study employ velocity inlet and pressure outlet boundary conditions. Through comparative analysis of the pressure distributions on both smooth and micro-grooved surfaces, it has been confirmed that the flow within the computational domain has reached a fully developed state. As shown in Figure 4e, under the micro-grooved surface condition, the pressure near the outlet exhibits certain variations but overall maintains a decreasing trend along the flow direction. Moreover, the pressure distribution within the grooved region remains relatively uniform, indicating that the flow in this region is fully developed. Figure 4f shows that, under the smooth surface condition, the pressure rapidly decreases near the inlet and then stabilizes, with significantly reduced pressure fluctuations in the grooved region, further demonstrating that the flow has achieved a steady and fully developed state. In summary, the aforementioned pressure distribution characteristics confirm that, under the selected boundary conditions, the flow within the computational domain has achieved full development and exhibits statistically stationary behavior. All subsequent analyses and discussions are conducted based on this fully developed flow condition, thereby ensuring the reliability of the numerical simulation results and the accuracy of the conclusions drawn.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Drag Reduction Rate Results

The drag reduction rate of the micro-grooves for each error type was calculated, and it is defined as follows:

where

denotes the total drag coefficient of the smooth surface, and

represents the total drag coefficient of the grooved surface.

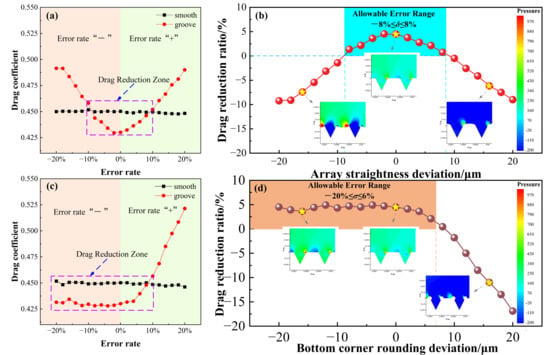

Figure 5 illustrates the drag reduction performance under two typical error types at 0.4 Ma. Specifically, Figure 5a,c depict the influence of array straightness error and bottom corner rounding error on the drag coefficient, respectively, while Figure 5b,d present the corresponding effects on the drag reduction rate. As observed in Figure 5a, as the array straightness error rate (δ) increases, the drag coefficient of the grooved surface gradually rises, with Cf increasing from 0.43 to 0.50, indicating a significant growth in frictional drag. In contrast, Figure 5c reveals that when the bottom corner rounding error rate (σ) lies within the negative deviation range (−20% ≤ σ ≤ 0%), Cf remains relatively stable at approximately 0.43. However, once σ enters the positive deviation range (0% ≤ σ ≤ 20%), Cf increases rapidly to 0.52, demonstrating a pronounced detrimental effect of this error on the drag reduction performance.

Figure 5.

Effect of different geometric errors on drag reduction: (a,b) Array straightness deviation; (c,d) Bottom corner rounding deviation.

A further analysis of the drag reduction rate trends in Figure 5b,d reveals that as the array straightness error increases, the drag reduction rate continuously decreases from 4.5% to −9.2%. Within the range of −20% to 0%, the rate of change is approximately −0.24%/%, indicating a systematic degradation of drag reduction performance due to this error. For the bottom corner rounding error, the drag reduction rate remains relatively stable at around 0.45% under positive deviation conditions (σ > 0). In contrast, under negative deviation conditions (σ < 0), it drops sharply from 4.5% to −16.9%, with a rate of change as high as −1.07%/%. This demonstrates that the bottom corner rounding error has a particularly pronounced impact on drag reduction performance within the negative deviation range, and its detrimental effect is significantly more severe than that of the array straightness error. Analysis based on the pressure contour plots shows that the array straightness error induces local flow separation and intensifies the adverse pressure gradient. The bottom corner rounding error, by altering the groove bottom curvature, leads to an imbalance in pressure distribution and enhances turbulent mixing, ultimately resulting in the degradation of the drag reduction rate.

In summary, to ensure that micro-groove structures fabricated via roll-to-roll hot embossing maintain stable and effective drag reduction performance, their geometric accuracy must be strictly controlled. Based on numerical simulations under different error levels, and using the maintenance of a positive drag reduction rate as the criterion, the allowable ranges for the array straightness error δ and the bottom corner radius error σ are determined as −8% ≤ δ ≤ 8% and −20% ≤ σ ≤ 6%, respectively. When manufacturing errors exceed these threshold intervals, the flow field structure near the grooves will undergo significant degradation, resulting in destabilization or attenuation of the vortex structures, thereby substantially diminishing the aerodynamic drag reduction effect.

3.2. Analysis of Flow Field Characteristics

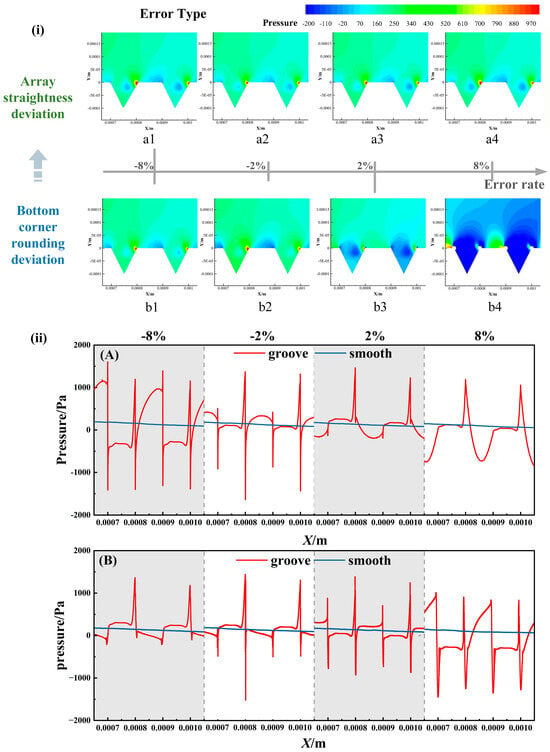

3.2.1. Pressure Distribution Characteristics

Based on the pressure contour plots and streamwise pressure distribution curves shown in Figure 6, an in-depth analysis of the flow mechanisms by which array straightness deviation and bottom corner rounding deviation affect the drag reduction performance of the grooves can be conducted. In pressure contour plot (i), the array straightness deviation leads to the formation of alternating high and low-pressure zones between the straight segments and valleys of the groove array. This pressure oscillates with large amplitude and high spatial frequency, reflecting a strong modulation effect of this error on the phase evolution of large-scale streamwise vortices. Specifically, the pressure variations corresponding to error rates of ±8% at locations a1 and a4 are associated with strong local adverse pressure gradients. This finding is consistent with the multiple pressure extrema observed in the streamwise pressure distribution curve (A). This indicates that the array straightness error not only triggers flow separation and reattachment but also, by generating unsteady secondary vortex pairs, enhances the extraction of energy from the mainstream flow. Consequently, this disrupts the originally stable low-speed streaks and increases the wall shear stress. In contrast, the smaller pressure variations at a2 and a3 for an error rate of ±2% suggest a relatively weaker influence of the error in these localized regions. Nevertheless, it still interferes with the self-sustaining mechanism of coherent structures by modulating the transverse velocity distribution. For the bottom corner rounding deviation, the pressure contour plot reveals the formation of more concentrated pressure extrema within the transition region at the groove bottom. Locations b1 and b4 similarly exhibit pressure variations corresponding to the ±8% error rate. This phenomenon is highly consistent with the observed flattened pressure recovery characteristic in the streamwise pressure distribution curve (B), which is primarily attributed to the concentration and expanded extent of high pressure in the fillet region, coupled with the shrinkage or even disappearance of low-pressure areas. This indicates that the rounded fillet delays flow separation, causing the separation point to move upstream and the reattachment region to shift downstream, thereby weakening the groove’s ability to spatially constrain turbulent coherent structures. The resultant effects include enhanced local turbulence intensity, reduced stability of near-wall coherent structures, and decreased convective transport efficiency of turbulent kinetic energy, ultimately leading to diminished drag reduction effectiveness.

Figure 6.

Pressure distribution under different error types. (i) Pressure cloud maps for: (a1–a4) array straightness deviation; (b1–b4) bottom corner rounding deviation. (ii) Streamwise pressure distribution profiles for: (A) array straightness deviation; (B) bottom corner rounding deviation.

Using the amplitude difference between high-pressure peaks and low-pressure valleys as a metric, the relationship between this pressure differential and the degradation in drag reduction can be observed, which is expressed as:

where

is the high-pressure peak (Pa),

is the low-pressure valley (Pa), and

denotes the amplitude difference between the high-pressure peak and low-pressure valley (Pa).

Based on the correlation curve between the amplitude difference of high-pressure peaks and low-pressure valleys and the degradation of drag reduction shown in Figure 7, the flow mechanisms by which the two types of geometric errors affect the drag reduction performance of the grooves can be quantitatively interpreted. For the array straightness deviation (a), a significant positive correlation is observed between the pressure amplitude difference and the drag reduction degradation: in the positive deviation range, the drag reduction rate decreases by 0.0067% for every 1 Pa increase in the amplitude difference; in the negative deviation range, it decreases by 0.0093% per 1 Pa. This indicates that the degradation of drag reduction performance induced by positive deviations is less sensitive to pressure fluctuations than that caused by negative deviations, reflecting distinct action pathways in their interference with near-wall turbulent structures. This quantitative relationship reveals that positive straightness errors relatively weakly perturb the evolution of large-scale streamwise vortex structures. Although the induced asymmetric pressure fluctuations enhance the large-scale vortex structures, they also reduce the energy transfer efficiency between these structures and the mainstream flow, thereby partially mitigating the rate of drag reduction degradation. In contrast, the bottom corner rounding deviation (b) exhibits a more pronounced unit effect: under the same 1 Pa increase in amplitude difference, the drag reduction rate decreases by 0.036% for positive deviations, while the decrease is only 0.0006% for negative deviations. This order-of-magnitude difference clearly demonstrates that the positive deviation range is the primary region responsible for the deterioration of drag reduction, with its impact intensity being approximately 5~10 times greater than that of the array straightness deviation. This is primarily because positive bottom corner rounding errors significantly alter the local geometry at the groove bottom, inducing flow separation in the corner region and triggering pressure fluctuations dominated by local energy dissipation.

Figure 7.

Relationship between the amplitude difference of high-pressure peak to low-pressure valley and the degradation of drag reduction for various error types: (a) array straightness deviation; (b) bottom corner rounding deviation.

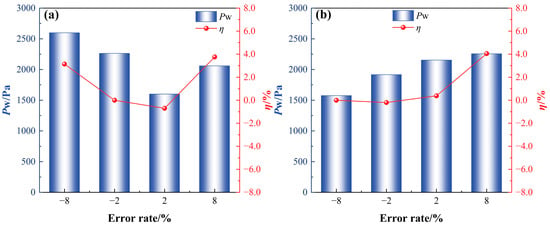

3.2.2. Velocity Distribution Characteristics

Based on the velocity streamlines and velocity distribution profiles provided in Figure 8, the effects of array straightness deviation and bottom corner rounding deviation on the drag reduction performance of the grooves can be thoroughly elucidated. In the velocity streamline plot (i), the array straightness deviation (a1–a4) significantly alters the near-wall flow structure, disrupting the ideal symmetry of the grooves and forming distinctly asymmetric flow patterns. This geometric error introduces an additional transverse velocity component as the fluid passes over the grooves, thereby disrupting the originally organized secondary flow system. Particularly at error rates of ±8% (a1, a4), evident flow separation and reattachment occur within the grooves, generating unsteady vortex structures. These transient vortices markedly enhance turbulence intensity and augment momentum exchange in the near-wall region, consequently increasing the wall friction drag. The corresponding velocity distributions along the y-direction at the groove bottom, middle, top, and over the smooth surface (ii-A) reveal distinctly asymmetric velocity profiles. Typically, the flow velocity is lower in the groove valleys, and manufacturing errors cause a further reduction in velocity. Specifically, at a bottom corner rounding error rate of −8%, the velocity variation amplitude in the valley reaches 12.90 m/s, indicating disturbed vortex generation. In contrast, the bottom corner rounding deviation (b1–b4) influences drag reduction performance by modifying the flow separation characteristics in the corner region. When the bottom corner rounding error rate (b4) reaches +8%, the separation point moves upstream, forming an expanded low-velocity zone that significantly impairs the groove’s ability to maintain stable secondary flows. The streamline patterns show that increased bottom corner rounding deviation reduces streamline curvature, restricting the development of effective vortical structures. This phenomenon is corroborated in the velocity profiles (ii-B), where positive bottom corner rounding deviations induce notable velocity deficits in the near-wall region and increase the boundary layer thickness. This altered flow structure demonstrates that the bottom corner rounding deviation reduces the efficiency of kinetic energy transfer by enhancing local energy dissipation.

Figure 8.

Flow fields under different error types. (i) Velocity streamlines for: (a1–a4) array straightness deviation; (b1–b4) bottom corner rounding deviation. (ii) Velocity distribution profiles for: (A) array straightness deviation; (B) bottom corner rounding deviation.

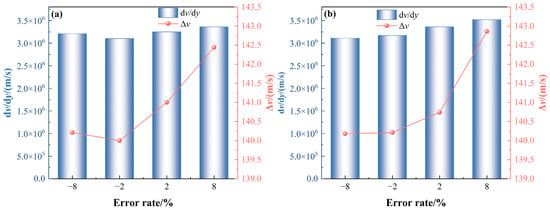

The non-uniformity of the velocity gradient and flow velocity distribution within the grooves is shown in Figure 9. The velocity gradient, represented by the slope of the bottom velocity curve, was quantified using the velocity profile in the region of y = 0~3.0 × 10−5 m to assess the flow acceleration effect. The non-uniformity of the velocity distribution was evaluated by the peak-to-valley difference of the bottom curve. Under array straightness deviation conditions (a), the velocity gradient (dv/dy) exhibits a significant non-linear variation with increasing error rate. When the error rate reaches 8%, the velocity gradient attains a value of 3.36 × 106 s−1. This phenomenon indicates that the array straightness error introduces streamwise asymmetry to the grooves, enhancing the interaction of large-scale vortex structures in the near-wall region and consequently amplifying the high-frequency components in the flow energy spectrum. Simultaneously, the velocity peak-to-valley difference (Δv) shows greater fluctuation amplitude in the positive deviation region, with a maximum difference of 142.44 m/s, directly reflecting the detrimental impact of straightness deviation on the uniformity of the streamwise velocity distribution. In contrast, the bottom corner rounding deviation (b) also demonstrates a more sensitive variation in the velocity gradient under positive deviations, reaching 3.52 × 106 s−1 at an error rate of 8%, while exhibiting a relatively moderate trend in the negative deviation region. This characteristic is closely related to the movement of the flow separation point induced by the bottom corner rounding error: positive deviations cause the separation point to move downstream, enhancing the flow acceleration effect within the corner region; whereas negative deviations shift the separation point upstream, weakening the groove’s ability to constrain the near-wall flow. It is noteworthy that the velocity peak-to-valley difference remains relatively stable across the entire error range, with a maximum fluctuation of only 2.86 m/s. This suggests that the bottom corner rounding deviation primarily influences the drag reduction performance by altering the local velocity gradient distribution rather than the overall flow velocity uniformity.

Figure 9.

Relationship between the velocity gradient and the peak-to-valley difference at the groove bottom for typical error types: (a) array straightness deviation; (b) bottom corner rounding deviation.

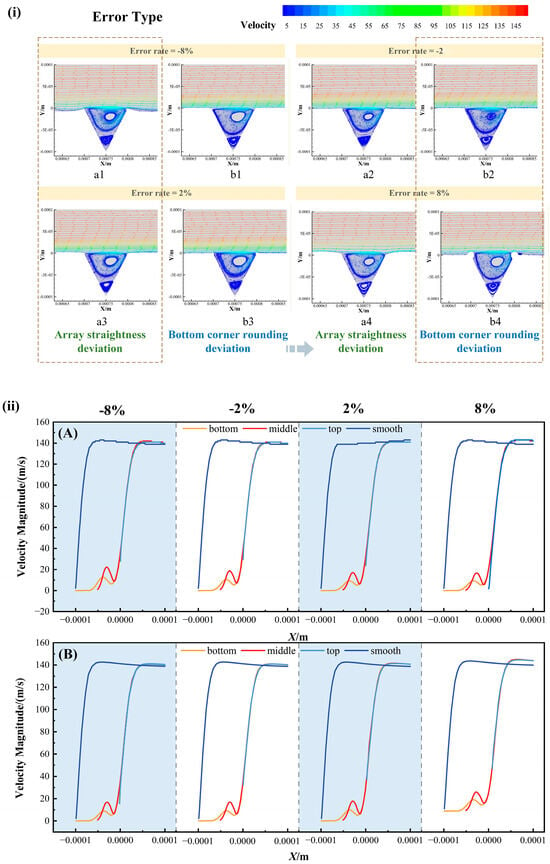

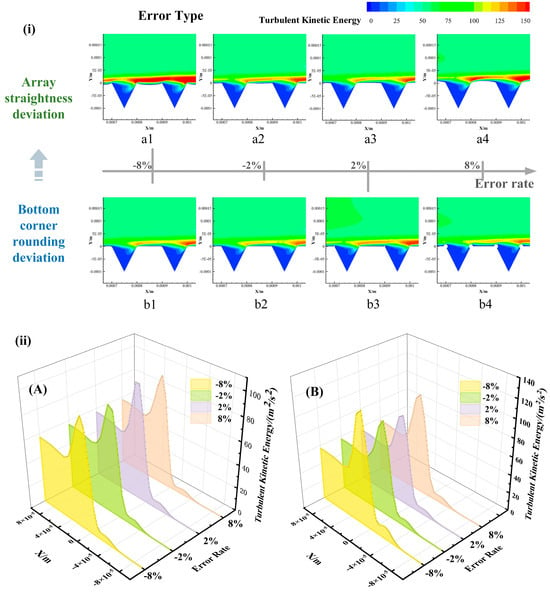

3.2.3. Turbulence Characteristics

Based on the turbulent kinetic energy (TKE) contours and distribution profiles presented in Figure 10, the turbulent mechanisms by which array straightness deviation and bottom corner rounding deviation affect the drag reduction performance of micro-grooves can be thoroughly interpreted. For the array straightness deviation (a1–a4), the TKE distribution exhibits a clear dependence on the error magnitude. At error rates of ±2% (a2, a3), the TKE within the grooves remains at a relatively low level (peak value of approximately 96.35 m2/s2), with high-TKE regions primarily confined to a narrow zone near the groove ridges. As the error rate increases to ±8% (a1, a4), the TKE distribution undergoes a qualitative transformation, forming not only a continuous high-TKE band along the groove ridges but also a significantly enhanced TKE region inside the grooves (peak value reaching 121.72 m2/s2). This indicates that the array straightness deviation primarily disrupts the spatial organization of large-scale turbulent structures and intensifies low-frequency fluctuating energy, thereby leading to stronger momentum transport. In contrast, the influence mechanism of the bottom corner rounding deviation (b1–b4) on turbulence characteristics follows a different pattern. At error rates of ±2% (b2, b3), the TKE shows a distinct local concentration in the bottom corner regions of the grooves. This suggests that while small bottom corner rounding deviations help maintain the stability of secondary vortex structures, the sharp geometric corners still induce local flow separation, subsequently generating small-scale turbulent structures via shear layer instability. As the error rate increases to −8% (b4), the TKE distribution demonstrates significant spatial reorganization, with a peak value as high as 93.17 m2/s2. Furthermore, the spatial extent of high-TKE regions within the grooves expands markedly, particularly forming a continuous TKE-enhanced band in the middle-upper groove regions. The increased bottom corner rounding deviation causes an upward shift of the vortex core, weakening the lifting effect of secondary vortices on the near-wall low-speed fluid. Simultaneously, the forward movement of the flow separation point in the fillet region extends the turbulence production zone from the groove corners toward the mainstream flow.

Figure 10.

Turbulent kinetic energy (TKE) distribution for various error types. (i) TKE contours for: (a1–a4) array straightness deviation; (b1–b4) bottom corner rounding deviation. (ii) TKE distribution profiles for: (A) array straightness deviation; (B) bottom corner rounding deviation.

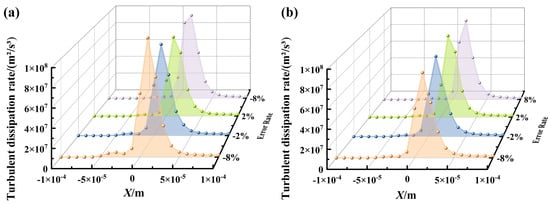

Based on the turbulent dissipation rate profiles along the normal direction at the groove valley under various error types, as shown in Figure 11, the spatial distribution characteristics directly reflect the differential impacts of distinct geometric errors on the near-wall turbulent structures. Under the array straightness deviation condition (Figure 11a), the turbulent dissipation rate distribution exhibits significant sensitivity to the error. At an error rate of −8%, the peak dissipation rate reaches 1.21 × 108 m2/s3, with a distinct dissipation concentration zone observed near the normal position y = 1.0 × 10−5 m. This occurs because the geometric irregularity induced by the array straightness deviation disrupts the spatial coherence of the coherent structures within the boundary layer, leading to local flow separation and enhancing the vortex stretching effect within the shear layer. It is particularly noteworthy that the streamwise curvature variation caused by the error significantly strengthens the correlation between the turbulence production and dissipation terms. This enhanced correlation causes violent deformation and breakup of vortex structures as they pass through geometrically discontinuous regions, substantially increasing the turbulent energy dissipation rate. In contrast, the bottom corner rounding deviation (Figure 11b) demonstrates different turbulent dissipation rate characteristics. Under error rates ranging from −2% to −8%, the peak dissipation rates remain relatively stable at 8.61 × 107 m2/s3 and 8.73 × 107 m2/s3, respectively, and the distribution profile shapes are largely consistent. However, at a positive error rate of +8%, the peak dissipation rate rises to 9.25 × 107 m2/s3, and the dissipation region exhibits a broader distribution within the groove. This is attributed to the increased bottom corner rounding deviation causing a spatial reorganization of the secondary vortex structures in the near-wall region, manifested specifically by an upward shift of the vortex core and an alteration of the vortex topology. This reorganization effect transforms the energy dissipation pattern from a concentrated mode in the groove bottom corner region to a spatially dispersed mode, while simultaneously intensifying the interactions among small-scale vortex structures.

Figure 11.

Turbulent dissipation rate curves for different error types: (a) Array straightness deviation; (b) Bottom corner rounding deviation.

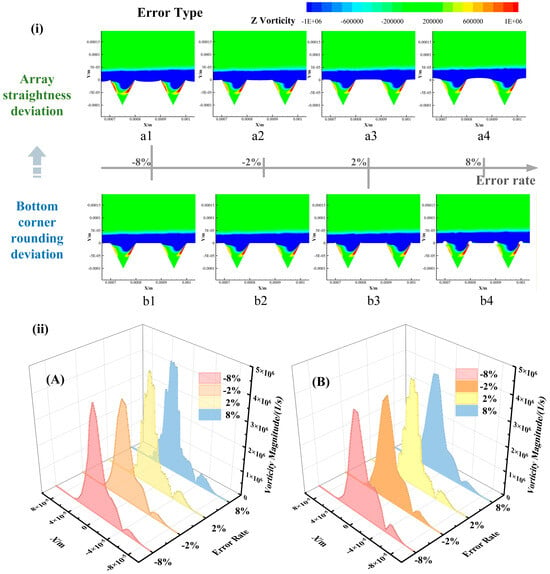

3.2.4. Vorticity Structure Evolution

Based on the vorticity distribution contours and profiles presented in Figure 12, this study systematically elucidates the differential influence mechanisms of two geometric error types-array straightness and bottom corner rounding-on the drag reduction performance of micro-grooves from a vorticity dynamics perspective. According to the vorticity transport equation:

where the terms on the right-hand side represent the vorticity convection term, vorticity diffusion term, and baroclinic torque term, respectively.

Figure 12.

Vorticity distribution for different error types. (i) Z-component vorticity contour for two error types: (a1–a4) array straightness deviation; (b1–b4) bottom corner rounding deviation. (ii) Vorticity magnitude profiles: (A) array straightness deviation; (B) bottom corner rounding deviation.

Under the condition of array straightness deviation (i-a1–a4, ii-A), the vorticity distribution exhibits systematic variation patterns. At an error rate of −8%, the peak vorticity measures 4.08 × 106 s−1, with a relatively organized vorticity structure forming within the grooves. According to the vorticity transport equation discussed earlier, moderate geometric variations at this stage do not disrupt the stability of the vortex stretching term. As the error decreases to −2%, the peak vorticity slightly increases to 4.15 × 106 s−1, indicating that minor geometric adjustments optimize the convective transport of vorticity. Under a positive deviation of +2%, the peak vorticity rises significantly to 4.26 × 106 s−1; however, localized inhomogeneities emerge in its distribution, suggesting that error-induced pressure gradient variations begin to influence the spatial organization of vorticity. At an error rate of +8%, the peak vorticity decreases to 3.96 × 106 s−1, accompanied by noticeable fragmentation of high-vorticity regions, confirming that pronounced geometric irregularity enhances the vortex stretching term and triggers instability in large-scale turbulent structures. In contrast, the bottom corner rounding deviation (i-b1–b4, ii-B) demonstrates a distinct nonlinear response. As the error rate increases from −8% to −2%, the peak vorticity declines from 4.35 × 106 s−1 to 3.98 × 106 s−1, representing a minimal variation of only 0.85%, while the drag reduction rate remains relatively stable. This behavior stems from the strong curvature effects at sharp corners, which sustain an effective vorticity generation mechanism via the baroclinic torque term, thereby preserving the fundamental topology of the vortex structures. However, a qualitative transition in flow characteristics occurs within the positive deviation range. At an error rate of +2%, the peak vorticity sharply increases to 4.56 × 106 s−1, reflecting how increased rounding error shifts the separation point and optimizes the

vector relationship in the baroclinic torque term, although excessive vorticity generation intensifies turbulent mixing. At +8% error, the peak vorticity decreases to 4.43 × 106 s−1, and a notable reduction in vorticity concentration is observed near the groove bottom. This confirms that excessively large fillet radii weaken the spatial confinement of secondary vortices, leading to a progressive deterioration in drag reduction performance with increasing positive deviation.

To quantitatively elucidate the underlying physical mechanism of drag reduction via micro-grooves, this study introduces a pivotal parameter-the Omega (Ω) criterion-to characterize the modification of turbulent coherent structures. This criterion is mathematically defined as the relative energy ratio of streamwise vortices to the total vortical energy, expressed as follows:

Here,

and

denote the energy intensity-represented by the squared Frobenius norm-of the velocity gradient tensor components associated with streamwise vortices (B) and spanwise vortices (A), respectively. The

value, bounded between 0 and 1, functions as a spatial indicator: values approaching 1 signify regions dominated by stabilizing, drag-reducing streamwise vortices, whereas values close to 0 correspond to regions governed by momentum-intensive, high-drag spanwise vortices.

An adaptive regularization term,

, is employed to ensure numerical robustness throughout the entire flow field.

This design ensures stability in regions with weak vortical activity without compromising the physical interpretation in critical areas. Furthermore, the auxiliary metric

provides a direct measure of the absolute energy surplus associated with the drag-reducing structures.

In summary, this framework provides insight into how micro-grooves suppress spanwise vortices and foster streamwise structures, clearly revealing the spatial effectiveness of drag reduction.

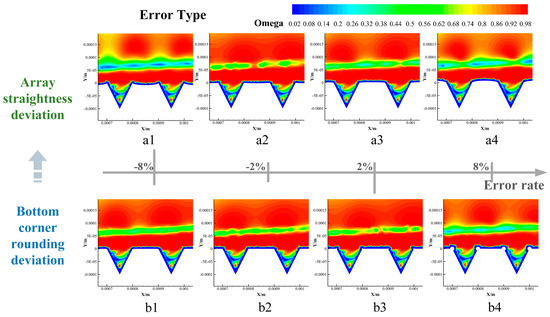

Figure 13 presents the effects of two types of geometric deviations-array straightness error and bottom corner rounding error-on the spatial distribution of the Omega (Ω) criterion. As a key metric for characterizing turbulent flow structures, the Ω criterion employs a threshold of Ω = 0.52 to visually indicate the relative dominance of streamwise versus spanwise vortical structures in the flow. From panels a1–a4, it can be observed that at a deviation level of ±2%, the area satisfying Ω > 0.52 expands, indicating the dominance of streamwise vortices and a more stable flow state, which corresponds to improved drag reduction performance. When the error increases to 8%, regions with Ω > 0.52 are significantly reduced, particularly along the groove edges and the leading-edge areas. This suggests an enhanced role of spanwise vortices, accompanied by intensified flow disturbances and a sharp deterioration in drag reduction. Panels b1–b4 reveal that at ±2% error, streamwise vortices remain dominant, leading to favorable drag reduction. However, as the error increases, especially at +8%, regions with Ω < 0.52 are substantially reduced, particularly in the groove bottom and peripheral regions. This indicates a notable weakening of streamwise vortices and a transition to spanwise-vortex-dominated flow, thereby increasing the fluid dynamic resistance.

Figure 13.

Omega criterion cloud images of various error types: (a1–a4) Array straightness deviation; (b1–b4) Bottom corner rounding deviation.

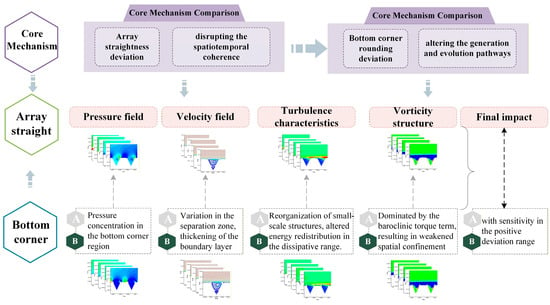

3.2.5. Summary of Flow Field Characteristics

Based on the comprehensive flow field analysis summarized in Figure 14, the influence of array straightness deviation on the drag reduction performance of the grooves primarily manifests as a systematic disruption of large-scale turbulent structures. The geometric irregularity induced by this error creates a periodic alternating distribution of high and low pressure in the near-wall region. A significant positive correlation (0.0067%/Pa) exists between the pressure amplitude difference and the degradation of the drag reduction rate, revealing a strong modulation effect on the phase of streamwise vortices. Analysis of the velocity field indicates that the error leads to distinctly asymmetric flow patterns, with the velocity gradient reaching 3.36 × 106 s−1 at ±8% error rates and a maximum velocity peak-to-valley difference of 142.44 m/s, severely compromising flow uniformity. In terms of turbulence characteristics, the error increases the low-frequency fluctuating energy, raising the peak turbulent kinetic energy to 121.72 m2/s3, while the dissipation rate reaches 1.21 × 108 m2/s3 at a −8% error rate. This indicates an intensification of momentum transport via an altered energy transfer path within the inertial subrange. The non-monotonic response observed in the vorticity field further confirms that the geometric irregularity disrupts the spatial stability of large-scale vortex structures through the vortex stretching term, ultimately resulting in a linear degradation of drag reduction performance.

Figure 14.

Summary of Flow Field Characteristics.

In contrast, the bottom corner rounding deviation affects drag reduction performance primarily by modulating small-scale turbulent structures. This error induces concentrated pressure extrema at the groove bottom, resulting in a flattened pressure recovery characteristic. A significantly high drag reduction decay of 0.036%/Pa is observed per unit pressure amplitude difference, indicating a sensitive response to local flow separation. The velocity field exhibits boundary layer thickening due to separation point movement, with the velocity gradient reaching 3.52 × 106 s−1 at the +8% error rate, while the velocity distribution remains relatively stable (with peak-to-valley difference fluctuations of only 2.86 m/s). Turbulence analysis reveals that the error mainly influences drag reduction performance by altering the energy distribution in the dissipation region. The turbulent kinetic energy remains relatively stable within the negative deviation range (peak value 93.17 m2/s3), whereas under positive deviations, the dissipation rate increases to 9.25 × 107 m2/s3 with an expanded distribution range. The unique nonlinear response of the vorticity field (showing only 0.85% variation in the negative deviation range) demonstrates that sharp corners maintain vorticity generation through the baroclinic torque term. Conversely, the upward shift of the vortex core induced by positive deviations weakens the spatial confinement capability of secondary vortices, ultimately leading to continuous deterioration of drag reduction performance in the positive deviation range.

4. Conclusions and Future Work

This study systematically investigates the variation in drag reduction performance of spanwise micro-grooves under different geometric error conditions at a flow velocity of 0.4 Ma and 0° angle of attack. The underlying mechanisms by which these errors influence the aerodynamic characteristics are elucidated from a flow field perspective. The findings provide theoretical support for optimizing the roll-to-roll hot embossing process used in fabricating drag-reducing micro-groove structures for aircraft applications.

- (1)

- As the array straightness error rate (δ) increases, the drag coefficient shows a continuous rise, with the drag reduction rate decreasing from 4.5% to −9.2%, exhibiting a systematic degradation trend. In contrast, the bottom corner rounding error demonstrates higher sensitivity within the positive deviation range (σ > 0), where the drag reduction rate drops sharply from 4.5% to −16.9%, indicating a significantly more severe deterioration than the former. Therefore, to ensure effective drag reduction performance of the micro-grooves, strict control over their morphological accuracy is essential. It is recommended to maintain the permissible error ranges for array straightness error (δ) and bottom corner rounding error (σ) within −8% ≤ δ ≤ 8% and −20% ≤ σ ≤ 6%, respectively, thereby avoiding degradation of drag reduction performance caused by deterioration of the flow field structure.

- (2)

- Based on flow field analysis, the intrinsic mechanism by which array straightness deviation leads to degraded drag reduction performance was identified as the disruption of large-scale turbulent structures. This geometric error induces periodic pressure fluctuations in the near-wall region, where a positive correlation between the pressure amplitude difference and the degradation of the drag reduction rate confirms its strong modulating effect on the phase of streamwise vortices. Furthermore, the velocity field exhibits asymmetric structures with compromised velocity gradients and uniformity. Turbulence characteristics demonstrate destabilization of large-scale structures and enhanced energy transfer within the inertial subrange. Additionally, vorticity field analysis validates that the geometric irregularity disrupts the spatial stability of large-scale vortex structures through the vortex stretching mechanism.

- (3)

- Multi-field coupling mechanism of how bottom corner rounding deviation affects drag reduction performance. Pressure field analysis indicates that the concentrated pressure extrema at the groove bottom leads to high sensitivity of the drag reduction rate to pressure variations. Velocity field characteristics reveal significant boundary layer thickening induced by separation point movement (with the velocity gradient reaching 3.52 × 106 s−1 at +8% error rate). Turbulence characteristics confirm a sharp increase in dissipation rate to 9.25 × 107 m2/s3 under positive deviation conditions, accompanied by an expanded distribution range. Vorticity structure analysis further reveals a unique nonlinear response mechanism: sharp corners maintain vorticity generation through the baroclinic torque term, whereas the upward shift of the vortex core caused by positive deviations weakens the spatial confinement capacity of secondary vortices.

- (4)

- During the roll-to-roll hot embossing process for fabricating micro-grooves, strict control of geometric precision should be implemented to ensure performance stability in complex aerodynamic environments. Based on this study, an optimized process window is proposed: the array straightness error δ should be controlled within −4% to 2%, and the bottom corner rounding error σ should be limited to −20% to 4%. Under these precision criteria, the fluctuation in the drag reduction rate of micro-grooves can be effectively constrained within 20%, significantly enhancing their reliability in practical applications. This precision control standard provides key technical guidance for the large-scale manufacturing of high-performance micro-grooves and holds substantial practical value for the engineering application of drag-reducing surfaces in aviation.

This paper focuses on two fundamental and critical types of geometric manufacturing errors: groove spanwise straightness and bottom corner radius. However, more complex geometric deviations are inevitably introduced in actual fabrication processes, such as systematic or random fluctuations in groove depth and width, asymmetry in cross-sectional profiles, and variations in sidewall inclination. These deviations may independently or synergistically alter the near-wall flow structures, effective volume, and secondary flow intensity, thereby inducing nonlinear effects on drag reduction performance. Therefore, future research should systematically evaluate the sensitivity to each of these independent geometric errors. More critically, it is essential to investigate the coupling effects and interaction mechanisms among multiple error parameters, with the aim of establishing a comprehensive quantitative mapping model that links geometric tolerances to aerodynamic performance responses. Such a model will provide a solid theoretical basis and design guidelines for the engineering tolerance design of micro-grooved surfaces, thereby enhancing the robustness and reliability of this technology under realistic manufacturing conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.D. and F.L.; Methodology, Y.D.; Investigation, Y.D.; Data curation, Y.D.; Writing—original draft, Y.D.; Writing—review and editing, Z.D. and F.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TKE | Turbulent kinetic energy |

| N-S | Navier–Stokes |

| SST | Shear Stress Transport |

| CFD | Computational Fluid Dynamics |

References

- Wang, Y.Q. Research on Surface Microstructures Induced Aerodynamic Drag Reduction. Ph.D. Thesis, Tsinghua University, Beijing, China, September 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, F.L.; Zeng, Z.X.; Gao, Y.M.; Liu, E.Y.; Xue, Q.J. Research status and progress of bionic surface drag reduction. China Surf. Eng. 2016, 29, 7–15. [Google Scholar]

- Deshmukh, S.S.; Goswami, A. Current innovations in roller embossing—A comprehensive review. Microsyst. Technol. 2022, 28, 1077–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, W.; Chiu, C.; He, J.; Ke, K.; Yang, S. Replication of large-area microstructures by combining movable induction heating and roller hot embossing. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2024, 64, 2191–2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-Y. Nonuniform heating method for hot embossing of polymers with multiscale microstructures. Polymers 2021, 13, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Wu, H.; Shu, Y.; Yi, P.; Deng, Y.; Lai, X. Roll-to-roll hot embossing system with shape preserving mechanism for the large-area fabrication of microstructures. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2016, 87, 105120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.Q.; Lan, H.B.; Xu, Q.; Lang, S.; Liu, H.Z. Modeling of flexible composite mold for nanoimprint lithography. JMechE 2018, 54, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, D.; Kim, J.-B. Material modeling of PMMA film for hot embossing process. Polymers 2021, 13, 3398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altuncu, E.; Tuccar Kilic, N. Investigating the thickness of patterned polyethylene layers by changing the line speed and temperature in the embossing machine. Iran. Polym. J. 2024, 33, 891–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobo-Martín, A.; Rueda, M.; Hernández, J.J.; Navarro-Baena, I.; Monclús, M.A.; Molina-Aldareguia, J.M.; Rodríguez, I. Bioinspired antireflective flexible films with optimized mechanical resistance fabricated by roll-to-roll thermal nanoimprint. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.Y.; Wu, Y.Y.; Han, Y.; LingHu, K.Q. Experimental study on influence of sharkskin denticles structure on the hydrodynamic performance of airfoil. Ocean Eng. 2023, 271, 113756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bixler, G.D.; Bhushan, B. Fluid drag reduction with shark-skin riblet inspired microstructured surfaces. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2013, 23, 4507–4528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domel, A.G.; Mehdi, S.; James, C.W.; Hossein, H.H.; Katia, B.; George, V.L. Shark skin-inspired designs that improve aerodynamic performance. J. R. Soc. Interface 2018, 15, 20170828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.M.; Liu, M.F.; Zhang, C.H.; Yan, H.; Zhang, M.H.; Wu, Q.S.; Liu, M.S.; Jiang, L. Bio-inspired drag reduction: From nature organisms to artificial functional surfaces. Giant 2020, 2, 100017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, T.F.; Liu, J.B.; Qin, L.G.; Lu, S.; Fagla, J.M.; Ma, Z.Y.; Hao, L.X.; Wu, Y.H.; An, D.; Dong, G.N. Effect of dolphin-inspired transverse wave microgrooves on drag reduction in turbulence. Phys. Fluids 2024, 36, 015157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvanose, S.M.; Marimuthu, S.; Awan, A.W.; Daniel, K. NACA 2412 Drag Reduction Using V-Shaped Riblets. Eng 2024, 5, 944–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.W.; Zhang, M.X.; Lin, P.Z. Skin Friction Reduction Characteristics of Nonsmooth Surfaces Inspired by the Shapes of Barchan Dunes. Math. Probl. Eng. 2017, 2017, 6212605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zuo, Y.; Zhang, H.; He, L.; Sun, E.; Long, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, P. A numerical study on the influence of transverse grooves on the aerodynamic performance of micro air vehicles airfoils. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 12371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.; Camobreco, C.J.; García-Mayoral, R.; Hutchins, N.; Chung, D. A viscous vortex model for predicting the drag reduction of riblet surfaces. J. Fluid Mech. 2024, 978, A18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; He, L.; Zheng, Y. Quasi-analytical solution of optimum and maximum depth of transverse V-groove for drag reduction at different reynolds numbers. Symmetry 2022, 4, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirandazi, P.; Hidrovo, C.H. Study of drag reduction using periodic spanwise grooves on incompressible viscous laminar flows. Phys. Rev. Fluids 2020, 5, 064102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inasawa, A.; Taniguchi, R.; Asai, M.; Sasamori, M.; Kurita, M. Experimental investigation of yaw-angle effects on drag reduction rate for trapezoidal riblets. Exp. Fluids 2024, 65, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, B.B.; Chen, D.R.; Liu, Z.Y.; Jiang, S.Y. Effect of riblet geometry on drag reduction of bionic riblet film. Funct. Mater. 2016, 47, 173–175. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, B.B.; Wang, J.D.; Chen, D.R.; Liu, Z.Y.; Jiang, S.Y. Drag reduction mechanism of feather-like riblet film. Funct. Mater. 2016, 47, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, L.; Kevin; Skvortsov, A.; Ooi, A. Effect of straight riblets of the underlying surface on wall bounded flow drag. Int. J. Heat Fluid Flow 2023, 102, 109160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gun, E.X. Study on the Influence of V-Shaped Groove on the Airfoil of Blunt Trailing Edge Wind Turbine. Ph.D. Thesis, Lanzhou University of Technology, Lanzhou, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, P.; Li, X.; Luo, Z.; Jia, Z.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, X. Research on drag reduction for flexible skin inspired by bionics. Coatings 2024, 14, 1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.J.; Huang, C.H.; Yu, B. Study of collaborative drag-reducing effect of surfactant solution and longitudinal microgroove channel. CIESC J. 2018, 69, 472–482. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.Q.; Ba, L.; Wang, G.F. Two typical rib shapes large eddy simulation. J. Liaoning Petrochem. Univ. 2019, 39, 58–63. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, Y.; Weng, D.; Wang, J. Drag reduction through air-trapping discrete grooves in underwater applications. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W. Research of Drag Reduction Performance of Roll Forming Microgrooves on Flat Sheet Metal. Ph.D. Thesis, Jilin University, Changchun, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.H.; Dong, W.C.; Xia, F. The effects of the tip shape of V groove on drag reduction and flow field characteristics by numerical analysis. J. Hydrodyn. 2006, 21, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Mayoral, R.; Jiménez, J. Hydrodynamic stability and breakdown of the viscous regime over riblets. J. Fluid Mech. 2011, 678, 317–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.R.; Li, S.G.; Liu, M.; Wang, S.L.; Yang, H.Y.; Liang, X.J. Numerical research on the turbulent drag reduction mechanism of A transverse groove structure on an airfoil blade. Eng. Appl. Comput. Fluid Mech. 2019, 13, 1024–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velthen, T.; Schuck, H.; Haberer, W.; Bauerfeld, F. Investigations on reel-to-reel hot embossing. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2010, 47, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.Q.; Zhang, X.; Yuan, C.Q. Numerical Analysis of Drag Reduction Performance of Different Shaped Riblet Surfaces. Mar. Technol. Soc. J. 2016, 50, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.