Abstract

Suspended-payload UAVs face a core dilemma in outdoor transportation: their stability is severely compromised by payload swing, yet conventional anti-swing controllers depend on real-time state feedback that is difficult to obtain without external sensors. To resolve this, we propose a fully integrated self-sensing anti-swing control strategy. Its key contribution lies in the seamless co-design of an external-sensor-free autonomous state estimation scheme and a coupled compensation control architecture: it eliminates the dependency on external sensors through an onboard estimation solution, actively suppresses swing via a coupled compensation framework, and rigorously guarantees stability through Lyapunov analysis. Specifically, an inertial measurement unit (IMU) at the suspension point fuses data with a Kalman filter for real-time payload state estimation. A sliding mode anti-swing controller is then integrated into the position control loop through dynamic coupling compensation. Strict Lyapunov-based analysis proves the bounded-error stability of this coupled system. High-fidelity simulations in CoppeliaSim under various scenarios validate the strategy’s engineering feasibility and synergistic performance. Results demonstrate that our method achieves high-precision state estimation and effective swing suppression, offering a practical and reliable solution for outdoor UAV transportation.

1. Introduction

With the rapid development of the low-altitude economy, drone technology [1,2], as one of its core drivers, is progressively penetrating various fields such as logistics transportation [3], emergency response [4], intelligent transportation [5], and agricultural crop protection [6]. Particularly in complex environments—such as urban dense areas, mountainous regions, and disaster sites—traditional transportation methods are often constrained by terrain, traffic, or infrastructure conditions, making it difficult to perform tasks efficiently and safely. Thanks to their flexibility, maneuverability, and strong environmental adaptability, suspended-payload UAV systems have emerged as a key technology in the low-altitude economy for addressing the “last-mile” delivery challenge [7]. However, for outdoor suspended-payload UAV flight, suppressing payload swing remains the most critical challenge. Moreover, most anti-swing control strategies still rely on real-time feedback of the payload state. These two challenges represent urgent and fundamental problems to be addressed in the field.

First and foremost, ensuring the safety and stability of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) during suspended-payload operations is the most critical and fundamental challenge. As underactuated, strongly coupled nonlinear systems, UAVs present inherent control difficulties. These challenges are significantly amplified when a payload is connected via a cable, which intensifies their underactuation and strong coupling characteristics. Payload swing severely compromises flight safety and poses substantial challenges for operators. In recent years, numerous research teams and scholars have conducted extensive studies on minimizing payload swing while ensuring trajectory tracking for UAV suspended-payload systems. Two primary technical approaches are commonly employed for swing suppression: (1) generating swing-free flight trajectories without payload swing angle feedback, and (2) implementing an anti-swing controller on the vehicle that utilizes payload swing angle feedback [8]. Sadr et al. utilized a feedforward control method based on input shaping technology to suppress residual load vibrations. Experimental results demonstrated that while input shaping can mitigate payload swing to some extent, it alone cannot adequately resolve the oscillation problem [9,10]. Wang et al. combined feedforward control with feedback control, proposing a controller design methodology that integrates feedforward trajectory planning with feedback-based sliding mode control. Their approach involved designing an S-curve function from an acceleration perspective to generate ideal trajectories for payload swing suppression, supplemented by feedback-based sliding mode control for further oscillation reduction [11]. Similarly, Wang et al. addressed the anti-swing control problem for a UAV with an elastically suspended-payload system by proposing a comprehensive method combining an elastic cable dynamic model with a nonlinear energy coupling controller [12]. Reinforcement learning has been employed in several studies for trajectory tracking and swing regulation, or for generating swing-minimizing trajectories through multiple iterations of simulated flight learning [13]. Hua et al. proposed a multi-rotor suspended-payload control strategy combining nonlinear control with reinforcement learning (RL), where RL adaptively adjusts control parameters to significantly enhance system robustness and positioning accuracy under model uncertainties and external disturbances while ensuring Lyapunov stability [14]. Similarly, Prajapati et al. developed a reinforcement learning (RL)-based control method for manually operating a UAV with a cable-suspended-payload, which generates desired attitude commands through training to effectively suppress load swing while tracking operator inputs [15]. However, reinforcement learning requires extensive flight trials to learn control policies and demands close matching between the simulated dynamics and the actual experimental platform dynamics, presenting substantial implementation challenges.

The design of controllers based on payload state feedback has also attracted increasing research attention. To address position tracking and swing suppression for systems with elastically suspended-payloads of unknown mass, Ru et al. developed an adaptive non-singular fast terminal sliding mode control method utilizing real-time feedback of both payload swing angle and cable deformation, significantly enhancing anti-disturbance performance under unknown load conditions [16]. Zhu et al. proposed a high-precision payload swing model incorporating a SPAD term and an improved UDE-based controller for UAV suspended-load systems. Through frequency-domain parameter tuning and time-domain anti-saturation design, the system achieved precise trajectory tracking even under strong wind disturbances [17]. Several researchers have further designed observers to mitigate the impact of disturbances or system failures [18,19,20].

However, obtaining accurate payload state information remains a critical challenge for such methods. Since UAVs operate outdoors and cannot rely on indoor motion capture systems (e.g., Vicon), alternative sensors or estimation methods must be employed. To address payload state acquisition, Gao et al. designed a swing angle measurement system using a potentiometer. Although simple to install, this approach is prone to environmental interference and long-term wear, leading to reduced accuracy [21]. Other researchers have utilized rotary encoders to measure swing angle [22,23]. Li et al. proposed a swing angle estimation method based on a six-axis force sensor, which calculates the direction vector of the cable tension in real time, enabling swing angle estimation without external equipment. Experimental results validated the effectiveness of this method under various payload conditions [24]. Lv et al. designed a novel suspension structure with a gyroscope mounted on a rigid carbon rod connecting the UAV and the payload, enabling direct measurement of the payload swing angle. Experiments demonstrated the effectiveness of this approach even under rotor downwash disturbances [25]. Mukras et al. used Hall sensors for measurement and introduced a novel six-degree-of-freedom test platform for safe performance testing of multi-rotor aircraft, including those with suspended loads [26]. Monocular vision-based detection systems have also been employed for swing angle detection [27,28], though this technology still faces bottlenecks due to environmental factors and other limitations. For example, the detection performance of vision-based methods is highly dependent on environmental lighting, visibility, and target features. In outdoor transportation scenarios, extreme weather conditions or obstructions can significantly degrade or even completely disrupt the functionality of visual sensors.

In summary, a review of existing research shows that while significant progress has been made in control and perception for suspended-load UAVs, two key challenges remain when operating in infrastructure-free outdoor environments. These challenges define the research gap addressed in this study: (1) Outdoor State Perception: High-performance anti-swing control methods typically require accurate real-time payload state measurements. However, outdoor environments prevent the use of motion capture systems, vision systems are affected by lighting and occlusion, and physical sensors face installation complexity, mechanical wear, and environmental interference. Moreover, single-sensor solutions such as gyroscopes suffer from limited accuracy. Thus, developing a robust self-sensing approach that relies only on onboard sensors, without external devices, remains a critical and unresolved research gap. (2) Theoretical Guarantees for Integrated Control: Open-loop strategies like input shaping offer limited anti-swing effectiveness, while most feedback-based methods depend on payload state measurements. Furthermore, when designing coordinated controllers that combine trajectory tracking and swing suppression—such as by coupling anti-swing actions into the position loop—rigorous and provable stability analysis is often lacking for the resulting nonlinear coupled system. This gap undermines the reliability of such systems in safety-critical outdoor applications [29,30,31].

This study addresses two major challenges in outdoor flight operations: the difficulty in detecting payload state and the significant impact of payload swing on flight safety. A self-sensing anti-swing control strategy is proposed to tackle these issues. The main contributions of this work are as follows:

- To address the challenge of measuring payload states in outdoor environments, this study proposes an external sensor-free autonomous state estimation scheme. An inertial measurement unit (IMU) is installed at the suspension point, and a Kalman filter algorithm is applied to fuse sensor data for accurate real-time estimation of the payload state. This method effectively leverages the advantages of both types of sensors while mitigating their individual limitations, operates without dependence on any external measurement systems (e.g., Vicon), and overcomes the constraints associated with single-sensor solutions such as monocular cameras or gyroscopes.

- To mitigate the adverse effects of payload swing on UAV stability and safety, a coupling compensation control architecture was designed. An anti-swing controller was developed based on feedback from swing angle estimation and integrated into the position control loop through compensation. This method overcomes the limitations of traditional control structures and significantly improves flight stability and safety.

- This study provides a rigorous Lyapunov-based stability proof for the coupled compensation control architecture that directly integrates anti-swing control with trajectory tracking. The analysis explicitly accounts for the nonlinear interactions between the two control loops and guarantees bounded error stability—a critical assurance for safe deployment that has often only been empirically validated in previous work.

- Proposed and implemented an engineering-oriented system integration framework that seamlessly incorporates self-sensing and anti-swing control modules. This solution was validated through a high-fidelity virtual simulation platform (CoppeliaSim), demonstrating its reliability and practicality as a unified system in tackling complex outdoor environmental challenges. It provides critical support for advancing UAV suspended-payload transportation from algorithmic research to practical deployment.

2. Dynamic Modeling of a Suspended-Payload UAV

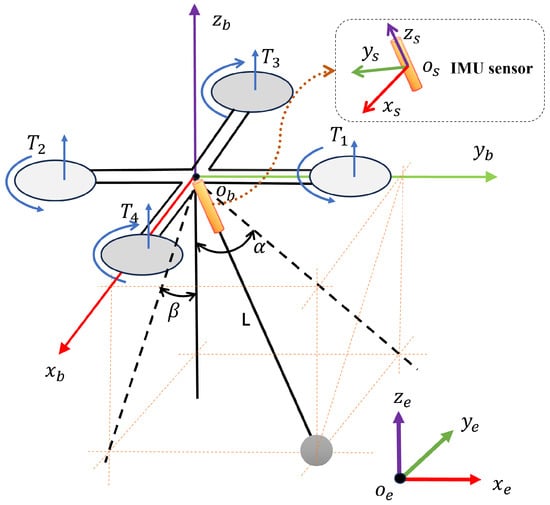

A UAV with a suspended-payload constitutes a highly coupled, underactuated, and nonlinear dynamic system, characterized by four control inputs and eight system outputs. If the payload is treated merely as an external disturbance, its swing during transportation can severely compromise flight safety. It is therefore essential to explicitly account for the coupling between the payload and the UAV by developing an integrated dynamic model of the suspended-load UAV system. A schematic diagram of the system is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the structure of a suspended-payload UAV.

To facilitate modeling and controller design, the following assumptions are adopted [32]:

Assumption 1.

The multi-rotor UAV is a symmetric rigid body.

Assumption 2.

The cable is attached at the center of mass of the UAV.

Assumption 3.

The cable remains taut and is treated as a massless rigid link capable of transmitting force only along its longitudinal direction.

Assumption 4.

The payload is modeled as a point mass.

First, define the world frame and the body frame , with the origin of both coordinate systems coinciding with the center of mass of the UAV. Let represent the coordinate system of the IMU (Inertial Measurement Unit) sensor. When the UAV is in a hovering state with the cable hanging vertically downward, the axes , , are parallel to , , , respectively, and the -axis always aligns with the cable. The forward direction of the UAV (nose direction) is defined as the positive -axis; the rightward direction of the UAV is defined as the positive -axis; and the upward direction perpendicular to the UAV body (opposite to gravity) is defined as the positive -axis. The swing angles , denote the angular displacements of the cable relative to the and planes, respectively. A positive swing angle corresponds to leftward motion of the UAV (negative direction), causing the payload to swing left; a positive swing angle corresponds to forward motion of the UAV (positive direction), causing the payload to swing backward. All variables used in this paper are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Table of UAV variables used in this study.

The rotation matrix from the body-fixed frame to the world frame can be expressed as:

where and .

The position of the payload is related to the position of the UAV as follows:

Differentiating Equation (2) twice with respect to time yields the relationship between the acceleration of the payload and that of the UAV as:

where , .

According to Newton’s second law, the following relation holds:

where and

is the acceleration of gravity, and the following holds:

Combining the above equations yields:

where . It is worth emphasizing that and are acceleration control commands, representing the proportional coefficients of the components of the total lift acting on the x and y axes.

The attitude kinematics can be expressed as:

where,

However, during actual suspended-payload transportation by UAVs, excessive attitude angles can lead to severe payload oscillations, significantly compromising flight safety. Therefore, operations are typically conducted with small attitude angles (i.e., attitude angles less than 15°). Under small-angle flight conditions, the following approximation holds:

The attitude dynamics can be derived from Euler’s equations as follows:

Among these, represents the gyroscopic moment, which primarily arises from the coupling between the high-speed rotating propellers and the motion of the UAV body. For small-scale UAVs, the gyroscopic moment is negligible during low-speed maneuvers and small-angle flight conditions. To simplify the controller design, it is treated as an uncertain disturbance and omitted in the model. Such disturbances can be robustly handled in the subsequent controller design using sliding mode control. Therefore, the attitude dynamics can be simplified as:

Let T denote the total kinetic energy of the system and P represent the total potential energy. Then

The swing dynamics of the payload can be derived using the Lagrange equation. The system dynamics are formulated as follows:

where denotes the generalized coordinates of the system and represents the generalized forces. Based on the assumption that the connecting cable is a rigid link, the force exerted by the UAV on the payload aligns with the direction of the cable. When the payload swings, the tension force of the cable remains perpendicular to the direction of the payload’s motion. As a result, the cable tension does no work and acts as a conservative force, which does not change the total energy of the system. By setting , and , , the equations of motion for the swing angles can be obtained [29]. Combining Equations (6) and (11) yields the dynamic model of a UAV with a suspended payload:

where .

3. Design of the Self-Sensing Anti-Swing Control Strategy

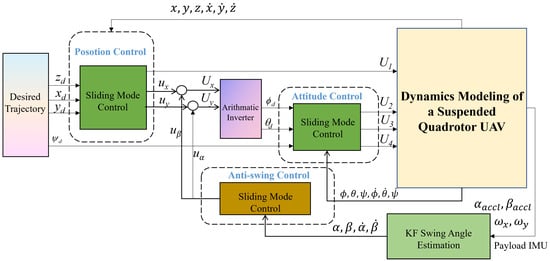

This chapter details the design of a self-sensing anti-swing control strategy for outdoor suspended-payload UAV flight. The content is divided into two main parts: payload state detection, and controller design with stability analysis. First, an external sensor-free autonomous state estimation scheme is proposed based on an IMU and Kalman filtering. Then, sliding mode control was employed to develop position, anti-swing, and attitude controllers for the UAV, along with a coupling compensation control architecture, followed by a comprehensive stability analysis. The overall control architecture is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

System overall design framework diagram.

3.1. Payload State Detection

An inertial measurement unit (IMU) typically consists of a gyroscope and an accelerometer, both of which can be used to estimate orientation. The gyroscope measures angular velocity, which can be integrated to obtain the three-axis rotation angles. The accelerometer, by comparing its measurements with the gravitational acceleration, can estimate the tilt angles along the X-axes and Y-axes, but cannot determine the rotation around the Z-axis. However, each sensor has inherent limitations, making neither sufficient alone for accurate attitude estimation. The gyroscope suffers from integration drift over time, leading to accumulating errors, though it performs well under dynamic conditions. The accelerometer, while free from drift, are highly sensitive to noise and susceptible to motion acceleration, which can significantly reduce their accuracy.

The Kalman filter is an efficient recursive state estimation algorithm whose core advantage lies in its ability to provide optimal minimum mean square error estimates in linear Gaussian systems. The algorithm operates recursively in real time, requiring only the previous state estimate and the current measurement to update the state, eliminating the need for historical data storage and ensuring high computational efficiency. Using the Kalman filter to fuse data from the accelerometer and gyroscope within an IMU, swing angles can be estimated accurately and efficiently, thereby providing reliable feedback for the control system.

Let the swing angles derived from the accelerometer be denoted as , , and the angular velocities provided by the gyroscope as . The state vector is defined as follows:

where represent the two-dimensional swing angles, and denote the two-dimensional angular velocities.

The state-space equation is defined as follows:

where the state transition matrix describes how the system state evolves naturally over time and is defined as:

where represents the sampling time, which corresponds to the simulation step size in the simulation setup. The control input matrix maps external control inputs to state updates. In this study, the angular velocity measurements from the gyroscope are treated as external control inputs, directly driving the angular velocity states. The matrix is defined as:

The process noise follows a Gaussian distribution , where the covariance matrix represents the gyroscope noise characteristics and is typically diagonal. A larger value of indicates lower confidence in the gyroscope measurements, leading the filter to rely more heavily on the accelerometer data.

The observation vector is defined as:

where and denote the swing angles measured by the accelerometer. The observation equation is defined as:

where

The observation noise follows a Gaussian distribution , where the covariance matrix represents the accelerometer noise characteristics and is typically diagonal. A larger value of RR indicates lower confidence in the accelerometer measurements, causing the filter to rely more heavily on the estimated state values.

To ensure that the IMU-based state estimator can effectively and uniquely determine the swing state of the payload, an observability analysis of the described system is conducted below. For such linear systems, their observability can be directly verified by checking whether the observability matrix is full rank (i.e., its rank equals the state dimension). The observability matrix is defined as:

Substituting matrices and into the calculation yields:

After performing elementary transformations, it can be observed that the submatrix formed by the first four rows:

Its determinant is . Since the sampling interval , the determinant of this submatrix is nonzero, indicating that it is full rank (rank = 4). Therefore, the observability matrix has a rank equal to the system state dimension of 4, proving that the linearized system model is fully observable. Following the observability analysis, which confirms that the system states are observable, we now proceed to the design of the Kalman filter-based state estimator.

The implementation of the Kalman filter primarily consists of two stages: the prediction phase (gyroscope-driven) and the update phase (accelerometer correction).

- 1.

- Prediction Phase:

Step 1: State Prediction

where the superscript denotes an estimated value, and the subscript indicates the prediction of the state at time based on all available information up to and including time .

Step 2: Covariance Prediction

- 2.

- Update Phase:

Step 1: Kalman Gain Calculation

Step 2: State Update

Step 3: Covariance Update

where is the identity matrix.

Through the design process described above, the swing angles estimated by the Kalman filter can be utilized as feedback variables for the controller.

3.2. Controller Design and Stability Analysis

As can be seen from Equation (15), the suspended-payload UAV can be divided into eight control channels. The control inputs for each channel are denoted as , , , , , , , . It is important to emphasize that the actual physical inputs to the system are , , , , while , represent virtual control inputs for position tracking, and , are virtual control inputs for swing angle suppression. These virtual control inputs must be converted into actual attitude commands to achieve their intended control objectives. Therefore, the control structure of the suspended-payload UAV can be organized into three parts: position control, anti-swing control, and attitude control.

3.2.1. Position Controller Design

The position subsystem of the suspended-payload UAV can be represented as:

Remark 1.

Readers should note the distinction between , and , in this paper: , represents the total position control law with integrated anti-swing compensation, while , refers solely to the position tracking control law without such compensation. The relationship between and , will be elaborated in later sections.

Assuming the expected position is , , . Define the position tracking error as

Sliding mode control (SMC), as a variable-structure robust control algorithm, offers significant advantages such as insensitivity to disturbances and strong robustness, making it highly suitable for complex systems like suspended-payload UAVs, which are highly underactuated and nonlinear.

To simplify the derivation process, the sliding mode controller design for the altitude channel is taken as an example, while the design procedures for the remaining channels follow the same approach. Let the sliding surface be defined as:

where represent the slopes of the sliding surface, which determine the convergence rate of the system error after reaching the sliding surface. When , the system enters the sliding mode, and its dynamic behavior is entirely governed by the equation of the sliding surface, independent of the system’s internal parameters and external disturbances—this embodies the robustness of sliding mode control. However, excessively large slope values, while accelerating convergence, may exacerbate chattering effects.

Differentiating the above expression yields:

Substituting Equations (32) and (33) yields:

The exponential reaching law accelerates the approach process through its “exponential term” when the state is far from the sliding surface, while employing a “constant-rate term” to ensure reaching the surface within a finite time. This approach effectively balances rapid convergence with finite-time stability. It enhances the dynamic response speed of the system while mitigating the chattering problem associated with traditional switching control. The exponential reaching law can thus be expressed as:

where . The parameter acts as a regulator of the reaching speed. Its primary role is to drive the system state rapidly toward the sliding surface when it is far away. In the context of UAV control, this means that when the UAV’s position is still distant from the desired position, generates a larger control input to accelerate convergence. However, excessively large values of may lead to overshoot. The term enhances robustness: when the system state deviates from the sliding surface, it pulls the state back toward the surface. A larger results in stronger disturbance rejection capability but also amplifies chattering effects.

Combining Equations (36) and (37) yields:

The control law is derived as:

Similarly, we obtain:

where .

Proof.

The Lyapunov candidate function is chosen as:

Differentiating it yields:

When , it follows that: . According to Lyapunov stability theory, the system is asymptotically stable. □

3.2.2. Anti-Swing Controller Design

Equations (40) and (41) provide the virtual position control laws for the UAV to track the desired position. These laws represent the desired acceleration required to reach a specified target position, which must ultimately be converted into desired attitude commands to actually control the UAV. However, payload swing significantly compromises the stability and safety of the UAV during flight. Therefore, an anti-swing controller—denoted as is designed to suppress oscillations of the suspended load. This controller can be interpreted as generating a desired acceleration that counteracts the payload swing, thereby stabilizing the UAV’s flight. Similar to the position control commands, the outputs of the anti-swing controller also need to be transformed into appropriate attitude commands for execution by the UAV.

The virtual control inputs for the anti-swing control channels are defined as:

The anti-swing control subsystem can then be expressed as:

The design process and stability analysis follow the same methodology as presented earlier, yielding the anti-swing control law:

where,

where . They represent the slopes of the sliding surface, determining the convergence rate of the error when the system state reaches the sliding surface. That is, they govern how quickly the swing angle approaches the desired swing angle (typically zero).

Proof.

The Lyapunov candidate function is chosen as:

Differentiating it yields:

When , it follows that: . According to Lyapunov stability theory, the system is asymptotically stable. □

In the previous sections, we derived the control law for trajectory tracking and the control law for suppressing payload swing. However, both controllers must be converted into desired attitude commands for implementation. During actual flight, the goal is for the UAV to accurately track the trajectory while maintaining the payload as stationary as possible, i.e., with minimal swing angle. As Equation (44) indicates, the virtual anti-swing control inputs are also related to the position control variables . This allows the swing suppression control inputs to be indirectly transformed into position control adjustments. Therefore, the total control input for trajectory tracking can be considered as compensating for an anti-swing control term , expressed as:

Under the small-angle assumption, the following approximations can be made:

In practical applications, to facilitate controller implementation, it can be assumed that , leading to:

Therefore, the position control input consists of two components: the first is the control input for tracking the desired trajectory, and the second is the anti-swing control input , which is derived from the sliding mode control algorithm as given in Equations (46) and (47) (denoted as ). Qualitatively, while drive the UAV to follow the trajectory, requires the UAV to adjust its position to suppress payload swing. Although each individual controller has been proven to be closed-loop stable, the stability of the coupled and compensated system must be further analyzed and verified. To assess stability, we substitute the coupled position control input (after compensation) into the Lyapunov function originally defined for the uncompensated control input , and examine whether it still satisfies the conditions of Lyapunov stability theory.

Taking the proof for the x-channel as an example, the same logic applies to the y-channel. Substituting the compensated position control input into the derivative of the sliding surface yields the actual derivative of the sliding surface after coupling compensation:

Combining with Equation (46) yields:

Let the control error be denoted as , which represents the discrepancy between the original control input for tracking the desired trajectory and the control input after incorporating anti-swing coupling compensation. This error metric is used to evaluate the impact of coupled compensation on system stability.

In practice,

It can be observed from the above expression that the actual control error corresponds to the compensated anti-swing control law.

Differentiating the Lyapunov function again yields:

Theorem 1.

Young’s inequality states that for any two real numbers , and any positive number , the following relation holds:

Therefore, the following holds:

Among them, is an auxiliary parameter that does not require manual adjustment; it serves only as a theoretical analysis tool. Theoretically, the existence of such a parameter is guaranteed, and we can achieve the desired control behavior by appropriately tuning the controller parameters.

Substituting into Equation (58) yields:

Let . Since the altitude controller and the anti-swing controller have been proven to be asymptotically stable in the previous analysis, both are bounded. This can be expressed as: .

Define a constant . Then:

Therefore, to ensure , the gains of the position controller must satisfy:

Since is an arbitrary positive number, this condition can always be satisfied by choosing a sufficiently large value of .

The inequality indicates that when the magnitude of is large, the negative term dominates, leading to and a decrease in system energy. When enters a small region near the origin, the positive term D may cause to become positive, but the system state will not grow indefinitely and will ultimately stabilize within a bounded region. This demonstrates that the is uniformly ultimately bounded.

By Equation (63), we can obtain:

By Equation (42), we can obtain:

Therefore,

As time approaches infinity, the following holds:

Therefore, the boundary of can be obtained as:

From Equation (70), it can be observed that after compensation, the system will operate near the sliding surface without exceeding this boundary. On the sliding surface , the sliding mode control ensures that the error converges to zero. We now discuss the actual behavior of the error within this region.

The solution for the error is obtained as:

Therefore, there is

As time approaches infinity, the following holds:

Therefore, after compensation, the error remains bounded. The system error is ultimately bounded by a fixed constant and is independent of the initial error . Although some precision is sacrificed, the loss is within an acceptable range, while payload swing is significantly suppressed. Stability analysis of the closed-loop coupled system is presented below.

Considering the extended system state composed of position tracking error and swing angle error, the following composite Lyapunov function candidate is defined:

From the above equation, it can be concluded that:

where , , and is a positive constant. For detailed derivation, please refer to Appendix A.

Based on the above inequality proof, it can be concluded that all signals of the coupled closed-loop system are uniformly ultimately bounded, ultimately converging to the region . Therefore, both the position tracking error and the payload swing angle will eventually stabilize within a bounded range around the origin. Furthermore, the error bounds can be derived as:

Through Lyapunov stability analysis, it can be concluded that the coupled compensation system is uniformly ultimately bounded stable. The error bounds derived above are explicitly dependent on the controller parameters. In practical engineering applications, these bounds can be adjusted by tuning the controller parameters.

Position control requires conversion into desired attitude commands for the UAV. Based on , the desired attitude can be derived as:

3.2.3. Attitude Controller Design

The attitude subsystem can be expressed as:

The controller design process is similar to that described in the previous section and will not be repeated here. The attitude control law is derived as:

where

As discussed earlier, the sliding mode control law based on the sign function sgn(s), while theoretically guaranteeing strict stability and robustness, tends to generate high-frequency chattering in practical digital systems due to its discontinuous switching. To improve control signal smoothness and engineering practicality, all sign functions sgn(s) in the control laws have been replaced with the continuous saturation function sat(s) in the subsequent simulations. The saturation function is defined as follows:

It is particularly important to note that the Lyapunov stability analysis and boundedness conclusions established earlier based on the sgn(s) function remain valid and provide critical theoretical guidance and guarantees for the system using the sat(s) saturation function.

4. Simulation Experiment

4.1. Simulation Scenario Overview

CoppeliaSim (formerly V-REP) is a versatile robotics simulation software developed by Coppelia Robotics, widely used in academic research, industrial automation, and education. It supports simulations ranging from simple manipulators to complex multi-robot systems, offering cross-platform compatibility with Windows, Linux, and macOS. The software integrates multiple physics engines—including Bullet, ODE, Newton, and Vortex—to accommodate diverse simulation requirements. Its modular architecture enables flexible functional extensions by users.

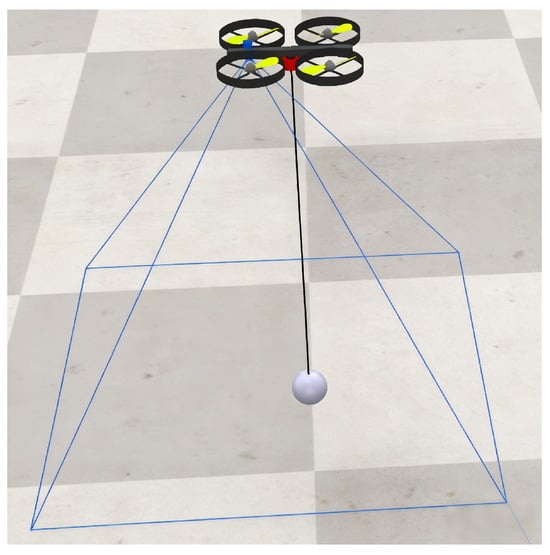

The simulation experiments in this study were conducted on the CoppeliaSim 4.9.0 virtual simulation platform, with data interaction handled through the ZMQ API using MATLAB 2021b. The simulation time step was set to 50 ms, and dynamics were computed using the Bullet 2.78 engine. A model of a UAV with a suspended payload was constructed in CoppeliaSim, with its schematic shown in Figure 3. The UAV utilized the built-in “Quadcopter” model, while the cable and payload were represented by a “Cylinder” and a “Sphere”, respectively. The connection between the UAV and the cable was implemented through a “Spherical joint”, which provides three rotational degrees of freedom defined by Euler angles and essentially consists of three orthogonal revolute joints in series, allowing direct reading of rotational angles in CoppeliaSim. It serves as the ground truth for the swing angle in the simulation experiments. An IMU sensor, comprising an “Accelerometer” and a “GyroSensor”, was mounted at the suspension point to measure three-axis acceleration and angular velocity, enabling the calculation of swing angles for use as feedback variables in the controller.

Figure 3.

Physical model of a suspended-payload UAV in CoppeliaSim.

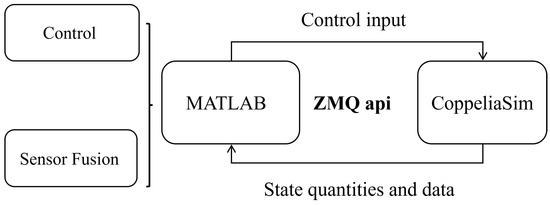

However, due to limitations in handling matrix operations and large-scale computations within CoppeliaSim, such tasks are offloaded to MATLAB. Communication between MATLAB and CoppeliaSim is established via the ZeroMQ (ZMQ) protocol, which offers high performance, low latency, and cross-platform flexibility—making it particularly suitable for real-time applications such as robotic simulation and control. Compared to CoppeliaSim’s native Remote API or ROS integration, ZMQ provides a lighter-weight communication solution that operates directly over TCP/IP without complex middleware configuration, significantly reducing communication overhead. The process of data exchange between MATLAB and CoppeliaSim is illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Communication between MATLAB and CoppeliaSim.

To validate the reliability of the proposed approach, this chapter designs two simulation experimental scenarios based on the CoppeliaSim simulation platform:

- (1)

- Point-to-Point Flight Scenario: The UAV initially hovers and then follows a straight-line trajectory to evaluate its dynamic response and swing suppression capability under static or steady-flight conditions. Simulation experiments are conducted in two distinct environments: ideal conditions and challenging scenarios with strong wind disturbances and sensor noise.

- (2)

- Outdoor Suspended-Payload Transportation Scenario: This scenario simulates UAV-based payload transportation in an urban environment, including planning an optimal trajectory based on the city layout, followed by trajectory tracking to test the applicability of the self-sensing anti-swing control strategy in complex environments.

The parameters of the suspended-payload UAV system are listed in Table 2, and the controller and Kalman Filter parameters are provided in Table 3 and Table 4.

Table 2.

Parameters of the suspended-payload UAV.

Table 3.

Controller Parameters.

Table 4.

Kalman Filter parameters.

4.2. Simulation Experiment Results

4.2.1. Point-to-Point Flight Simulation Experiment

The UAV starts from an initial position of with all other states zero, including desired swing angles rad, rad, and is commanded to reach a target position . Four control strategies were compared in the simulation: a traditional cascaded PD controller, a sliding mode controller implemented on the same conventional structure, a combined sliding mode controller with integrated swing suppression and position coupling compensation (the proposed method), and a sliding mode controller enhanced with feedforward input shaping.

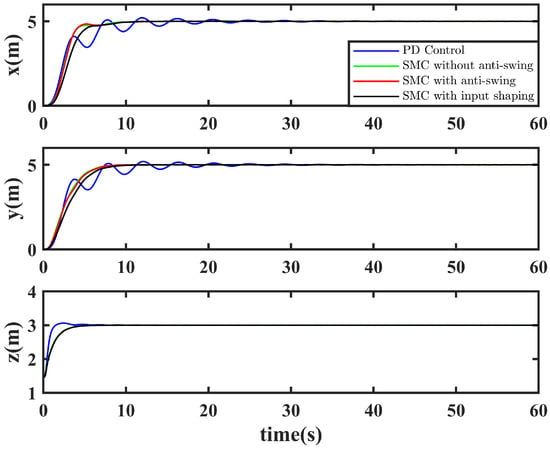

The simulation results are shown in Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11 and Figure 12, with detailed quantitative metrics provided in the Appendix B. Figure 5 demonstrates the position tracking performance: while all four algorithms successfully guide the UAV to the target position, the PD controller, as a linear control method, exhibits poor disturbance rejection. Its maximum overshoot (4.13%, 3.80%, 2.10%) is significantly higher than that of the three robust sliding mode control variants, and it produces noticeable oscillations. In contrast, the sliding mode control algorithms provide fast response and low sensitivity to disturbances, effectively suppressing their impact on the UAV. As a result, payload swing severely affects flight stability, and linear controllers such as PD struggle to reject such disturbances, failing to maintain smooth operation in complex environments.

Figure 5.

Position tracking control under ideal conditions. Among the methods, PD control exhibits weak robustness, while the remaining controllers based on sliding mode control algorithms demonstrate strong robustness.

Figure 6.

Attitude tracking control under ideal conditions. Among the methods, PD control requires large attitude adjustments, the other two methods need continuous small attitude corrections, while the proposed approach rapidly stabilizes the payload with nearly constant attitude maintenance.

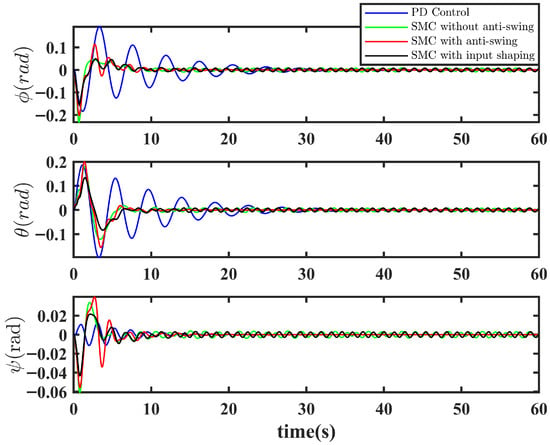

Figure 7.

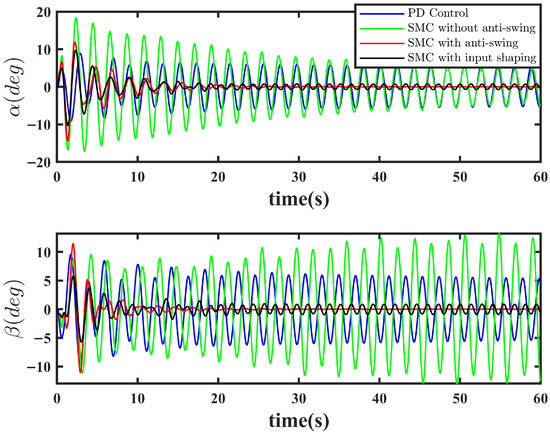

Payload swing angle under ideal conditions. Without anti-swing strategies, the payload exhibits severe oscillation. The open-loop input shaping method can partially suppress swing but has limited effectiveness. In contrast, the anti-swing approach proposed in this study achieves significant swing suppression.

Figure 8.

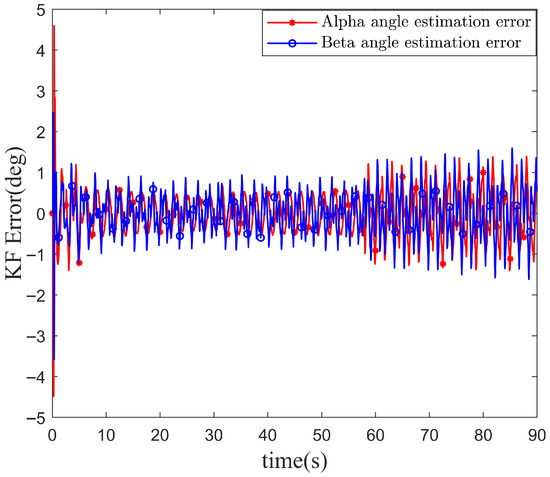

Payload state estimation error under ideal conditions. The Kalman filter-based fusion of IMU data proposed in this study outperforms single gyroscope measurements. Single-sensor approaches have inherent limitations.

Figure 9.

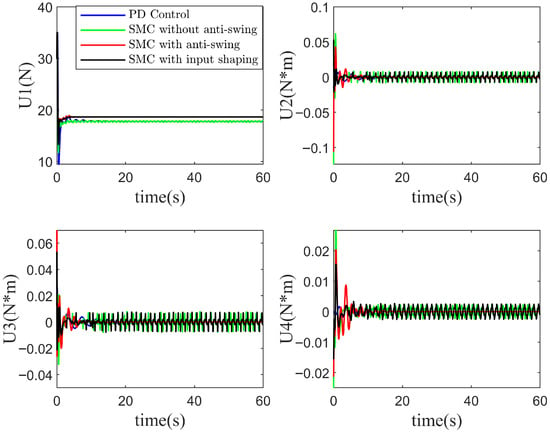

Control input under ideal conditions. The anti-swing control strategy proposed in this study demonstrates effective and targeted payload swing suppression. By incorporating a saturation function into the sliding mode control, the control signals exhibit improved smoothness with significantly reduced chattering.

Figure 10.

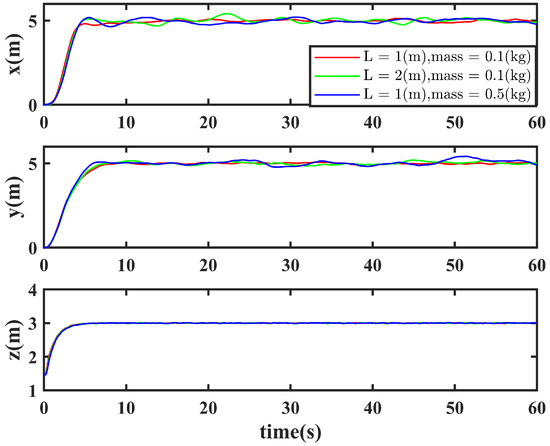

The anti-swing strategy proposed in this paper maintains strong robustness in position tracking control under challenging conditions including strong wind disturbances and sensor noise, across different cable lengths and payload masses. Even in such demanding scenarios, the method demonstrates consistent performance adaptability.

Figure 11.

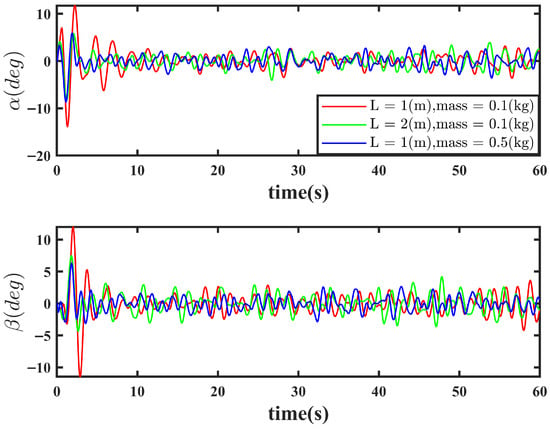

The anti-swing strategy proposed in this paper maintains effective swing suppression under challenging conditions—including strong wind disturbances and sensor noise—across varying cable lengths and payload masses. Even in such demanding scenarios, the method consistently restricts payload swing within a small range.

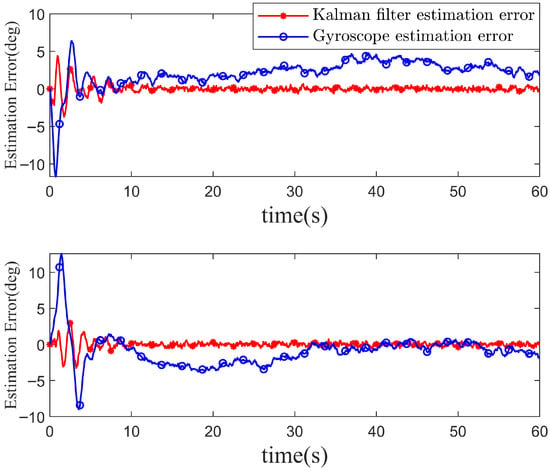

Figure 12.

State estimation error under strong wind disturbances and sensor noise ( m, kg). Under these challenging conditions, the self-sensing method proposed in this paper demonstrates stronger robustness and higher estimation accuracy compared to single-sensor measurement approaches.

Figure 6 shows the attitude tracking performance of the UAV, where all Euler angles remain within 15°, satisfying the small-angle flight condition. Due to disturbances from payload swing, the PD controller employs relatively large attitude adjustments and exhibits prolonged oscillations. In contrast, the sliding mode control algorithm responds more flexibly and is less sensitive to disturbances, thus avoiding sustained large-amplitude attitude oscillations. When the UAV nearly enters a hover state, both “PD Control” and “SMC without anti-swing” lack dedicated swing suppression, leading to continuous payload swing that requires constant attitude adjustments. “SMC with input shaping” incorporates an open-loop feedforward input shaping strategy, which partially mitigates swing but remains limited by its open-loop nature, preventing full suppression and still necessitating attitude corrections in later stages. The anti-swing strategy proposed in this study significantly eliminates payload swing. As mathematically demonstrated, the error stabilizes within an extremely small bound. Consequently, the attitude remains almost constant in the final stage, reflecting the UAV’s stability and safety.

Figure 7 illustrates the payload swing angle response. As shown, “PD Control” and “SMC without anti-swing” fail to eliminate payload oscillation. Taking as an example, their root mean square errors are 4.28° and 6.96°, respectively. The “SMC with input shaping” strategy, which incorporates feedforward input shaping, effectively suppresses swing with an RMSE of 2.14°, demonstrating significant improvement over the former two. However, due to the inherent limitations of open-loop methods, the design of the input shaping relies on oversimplified models, leading to residual small-angle oscillations. This aligns with the earlier discussion that methods like input shaping and reinforcement learning are highly sensitive to model inaccuracies and environmental variations. In contrast, feedback-based anti-swing control using payload state estimation offers stronger robustness, achieving an RMSE of 1.78° and outperforming the other three algorithms. Furthermore, through rigorous stability analysis and proof, this study ensures that the compensated error remains within a minimal and adjustable range, forming a critical foundation for safe operation.

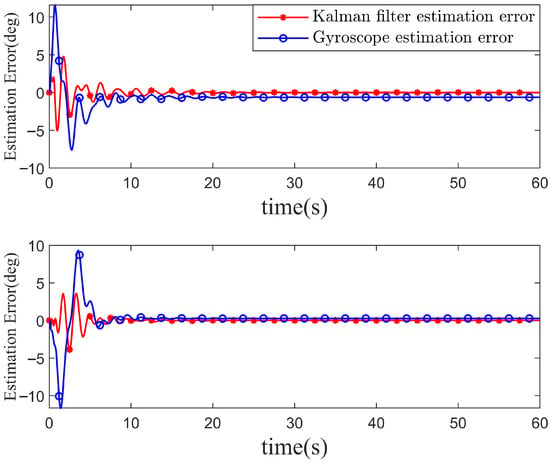

Figure 8 shows the payload swing angle estimation error. This study compares the proposed self-sensing payload state estimation scheme with a single-gyroscope measurement approach. The IMU and Kalman filter-based estimation method proposed in this study demonstrates strong reliability, with root mean square errors of 0.68° and 0.57°, and maximum deviations of 5.07° and 3.86°. In comparison, it outperforms the single-gyroscope measurement method, which exhibits root mean square errors of 1.60° and 1.71°, and maximum deviations of 11.58° and 11.68°. Single-sensor measurement methods are limited by their inherent constraints. For example, gyroscopes and force sensors suffer from significant accuracy issues, while vision-based methods, though offering high precision and scalability, are susceptible to lighting conditions, occlusions, and field-of-view limitations in outdoor environments. Moreover, if cameras are mounted away from the center of mass, additional torques may be introduced, posing potential risks to UAV safety. The external sensor-free payload state estimation method proposed in this study overcomes the limitations of single-sensor approaches by leveraging the complementary advantages of two sensors and remaining unaffected by environmental factors such as lighting. Thus, the autonomous state estimation scheme proposed in this study serves as a feasible and reliable solution for outdoor UAV transportation.

Figure 9 illustrates the control inputs. To quantitatively describe the control effort, the total variation metric is introduced. In the proposed method, “SMC with anti-swing”, the sign function is replaced by a saturation function to suppress sliding mode chattering, while the other two sliding mode controllers still use the sign function. The total variation of the attitude control input (0.39, 0.35, 0.16) is significantly better than the other two groups. As can be seen in the figure, the control input remains almost constant after the UAV hovers and suppresses the payload swing, whereas the other two sliding mode controllers exhibit severe chattering. This is due to both the dynamic attitude adjustments to counteract swing and the chattering induced by the sign function.

To make the simulation environment more closely approximate real-world conditions, this study introduces strong wind disturbances and sensor noise. First, considering Level 6 strong winds with an average speed of 10.8–13.9 m/s, the force limit on the UAV was estimated at 1.8 N based on its frontal area and rotor span. Accordingly, forces randomly ranging from 0.3 N to 1.8 N in random directions were generated in the simulation. Random noise with an amplitude of 0.05 m/s2 was added to the accelerometer measurement channel, and noise with an amplitude of 0.02 rad/s was introduced into the gyroscope measurement channel. The noise levels considered in this study exceed those of typical IMUs, simulating a highly challenging operational scenario.

Figure 10 and Figure 11 illustrate the position tracking performance and swing angle response of the proposed method under challenging conditions (strong wind and sensor noise) with varying payload masses and cable lengths. The self-sensing anti-swing control strategy proposed in this study maintains strong robustness even under strong wind disturbances and sensor noise. Although slight oscillations occur near the target position, the controller consistently actively compensates for disturbances, ensuring the UAV remains in the vicinity of the target. Furthermore, swing suppression remains effective, with the swing angle regulated within 5° after adjustment, thereby ensuring transportation safety. The study also compares scenarios with different cable lengths and payload masses, demonstrating the method’s consistent applicability across various suspended-payload transportation tasks. Future work will further investigate the specific effects of cable length and payload mass on control performance and swing suppression.

Figure 12 shows the estimation errors of the autonomous state estimation scheme and the gyroscope-only measurements under challenging conditions. After introducing disturbances and noise, both methods exhibit some level of chattering. However, the Kalman filter-based IMU fusion approach demonstrates stronger robustness, with root mean square errors of 0.72° and 0.64°, and maximum deviations of 4.81° and 3.82°. These results are notably superior to those of the single-gyroscope measurements, which show root mean square errors of 2.84° and 2.40°, and maximum deviations of 11.68° and 12.56°. Furthermore, compared to the performance under ideal conditions, the proposed autonomous state estimation scheme shows little sensitivity to environmental changes, with minimal variation in estimation error. Thus, this method offers stronger robustness and remains suitable for outdoor applications, even under challenging operating conditions.

4.2.2. Suspended-Payload Transportation Simulation Experiment

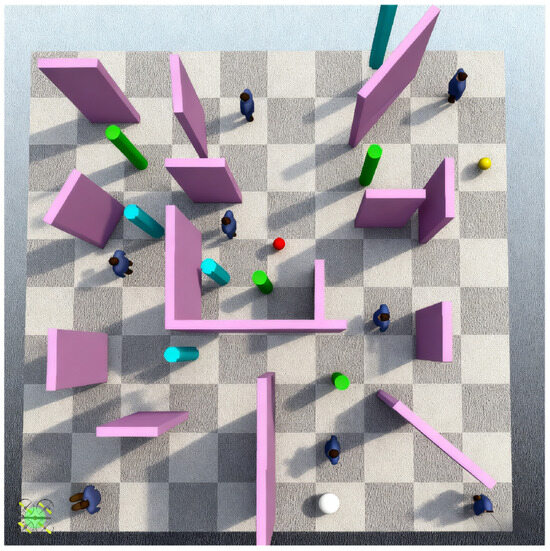

To effectively validate the cooperative performance and overall robustness of the integrated self-sensing anti-swing control system in complex environments, this study utilizes sampling-based path planning algorithms [33,34,35,36,37,38] to generate highly dynamic and challenging trajectories. The planner first generates a collision-free path, which is then converted into a smooth and dynamically feasible time-domain trajectory using the Minimum Snap optimization method. To more closely approximate real engineering conditions, a simulated urban transportation scenario (also applicable to mountainous or similar terrains) was built in CoppeliaSim, as shown in Figure 13. Pink obstacles in the scene represent buildings, while green and blue obstacles represent urban elements such as utility poles and trees. The UAV in the lower left corner of the figure represents the starting position, while the yellow sphere on the right indicates the goal point. The simulation experiment was conducted in a 10 m × 10 m simulated urban environment, where each grid cell in the diagram measures 1 m × 1 m. Path planning and trajectory generation are performed first, followed by validation of the proposed self-sensing anti-swing control strategy. The simulation experiments in this section further verify the stability and robustness of the proposed method in complex environments and under challenging task requirements.

Figure 13.

Simulation experiment 2: CoppeliaSim scenario for urban transportation simulation.

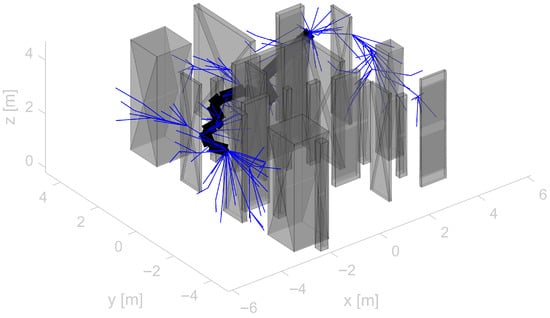

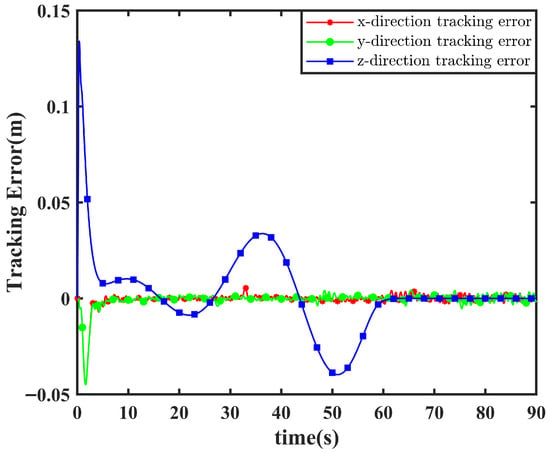

Figure 14 shows the path planning results using the improved Bi-RRT* algorithm in a simulated urban map built in CoppeliaSim. The improved Bi-RRT* algorithm found a path in 24 iterations, taking 2.06 s. The Minimum Snap algorithm was then used to generate a trajectory, specifying the target position, velocity, and acceleration of the UAV at each time step. This trajectory planning method was employed to validate the performance and robustness of the proposed self-sensing anti-swing control strategy for outdoor suspended-payload flight under complex command conditions, rather than merely testing point-to-point navigation. Figure 15 demonstrates the trajectory tracking capability of the suspended-payload UAV. It is clearly observed that the UAV accurately follows the planned trajectory, with errors consistently remaining within a very small range. However, increased tracking error occurs during turns, though it remains within acceptable limits. This may be attributed to abrupt changes in the planned trajectory, where the controller may not respond rapidly enough to sharp turns, leading to temporarily elevated errors. After 60 s, the UAV reaches the target position and enters a hover mode with active swing suppression. The altitude error remains nearly zero throughout, while oscillations persist in the x and y directions. As demonstrated earlier in this study, the position controller with integrated anti-swing compensation ensures bounded error. Thus, the system stabilizes within a bounded error range without divergence, which aligns with the observations from simulation experiment 1.

Figure 14.

Improved Bi-RRT* path planning. This trajectory is used as the desired trajectory for the UAV to test the feasibility and reliability of the proposed algorithm under complex commands and environmental conditions.

Figure 15.

Trajectory tracking error. After applying anti-swing compensation, the errors in both the x and y directions are confined within bounded ranges.

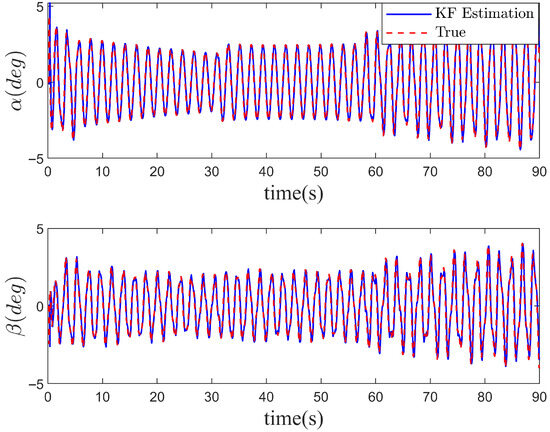

Figure 16 illustrates the actual swing angle and its estimation performance. As shown, after incorporating coupling compensation, the system maintains the swing angle within a small range during both static anti-swing operations and dynamic flight, significantly enhancing the stability and safety of outdoor suspended-payload UAV operations. This enables the UAV to accurately track the desired trajectory while effectively suppressing payload oscillation. The IMU-based estimation method with Kalman filtering, as proposed in this study, also demonstrates excellent performance in simulation. As further supported by Figure 17, although the initial error is around 5°, it rapidly converges and remains within 2° thereafter. Although IMU measurements are susceptible to motion acceleration during flight, the resulting errors remain acceptable for most practical applications. The sliding mode control algorithm used in this study—known for its strong robustness and low sensitivity to disturbances—can also compensate for sensor inaccuracies. Therefore, the external sensor-free autonomous state estimation scheme proposed in this paper effectively addresses the challenge of detecting payload states in outdoor suspended-payload UAV flights. However, in scenarios requiring extremely precise swing angle estimation, additional sensors such as vision systems or encoders could be integrated to further improve accuracy through multi-sensor fusion. Nevertheless, the proposed method remains highly applicable in most commercial and industrial settings, demonstrating considerable practical value.

Figure 16.

Swing angle response and estimation. It maintains the payload swing within a small angular range even under complex commands and challenging environmental conditions.

Figure 17.

Kalman filter estimation error. The autonomous state estimation remains accurate within a defined range, even under complex commands and challenging environmental conditions.

5. Conclusions

This study addresses the core challenge in outdoor UAV suspended-payload transportation—the reliance of anti-swing methods on real-time state feedback that is difficult to reliably obtain in outdoor environments—by proposing an integrated swing suppression control solution that combines perception, control, and stability assurance. The solution breaks traditional barriers between perception and control through co-design: first, an external sensor-free autonomous state estimation scheme is established, using an IMU at the suspension point and Kalman filtering to achieve accurate real-time estimation of the payload state, resolving the reliability issue in outdoor perception. Subsequently, a coupled compensation control architecture is designed, dynamically embedding a sliding mode anti-swing controller into the position loop to achieve coordinated optimization of trajectory tracking and swing suppression. Crucially, this study provides a rigorous uniformly ultimately bounded stability proof for the coupled system via Lyapunov stability theory, mathematically ensuring overall robustness and safety boundaries of the integrated system. High-fidelity simulation experiments validate the engineering feasibility of the integrated strategy, achieving accurate estimation, smooth tracking, and effective swing suppression at the system level. Ultimately, this study delivers a complete technical pathway encompassing perception, control, and stability verification, offering a solid and reliable system-level solution for the practical deployment of outdoor UAV suspended-payload transportation.

6. Limitations and Future Work

Although the self-sensing anti-swing control strategy proposed in this study for outdoor suspended-payload UAV flight has demonstrated excellent performance in simulation, certain limitations and areas for improvement remain. Translating these promising results into real-world deployment requires addressing several key challenges and conducting further work.

- (1)

- Limitations of IMU-based swing angle estimation.

The proposed method, while effective in simulation, is subject to several practical limitations. Firstly, the core limitation of the IMU-based estimator is its susceptibility to motion acceleration, which corrupts the gravity vector measurement during aggressive maneuvers. Although sensor fusion mitigates this, estimation fidelity degrades when control is most critical. Secondly, the practical deployment relies on a high-performance wireless link between the remote IMU and the UAV, introducing potential latency and reliability issues not considered in this simulation study.

Future work will therefore focus on: (a) developing adaptive filtering strategies that can detect and compensate for periods of high kinematic acceleration; (b) exploring the use of ultra-wideband (UWB) ranging as a complementary, acceleration-invariant sensing modality for swing angle estimation; and (c) implementing and testing the complete system on a physical platform to address the practical challenges of communication, integration, and calibration.

- (2)

- Limitations of model simplifications.

The dynamic model and controller design proposed in this study are based on two fundamental simplifying assumptions: the connecting cable is massless and can be treated as a rigid link. Although these assumptions are commonly adopted in preliminary research to reduce model complexity and facilitate controller design, their validity in real-world scenarios and their impact on system performance require rigorous examination.

While the massless cable assumption adopted in this study effectively validates the performance of the self-sensing and anti-swing control framework, this idealized model neglects the compound pendulum effects and higher-order oscillation modes introduced by actual cable mass. This simplification may lead to degraded performance of the designed controller when confronting the complex dynamics of real-world systems. To bridge this gap between simulation and reality, future work will focus on incorporating a more accurate distributed-mass cable model and exploring strategies such as adaptive control compensation to enhance the controller’s robustness against unmodeled dynamics. These efforts aim to achieve reliable deployment in complex physical environments.

In this study, the cable is simplified as a rigid link to facilitate controller design, but this approach neglects its essential elasticity and potential slackness. In reality, cables possess finite stiffness. This elasticity introduces additional degrees of freedom and new oscillation modes, such as longitudinal bounce (vibration along the cable axis). Under certain excitation frequencies—for example, during rapid vertical acceleration of the UAV—resonance may occur, causing the payload to oscillate along the stretched cable. Future work will incorporate a spring-damper-based flexible cable model and develop a state-machine switching strategy to handle both tensioned and slack dynamic modes, thereby comprehensively improving system safety and robustness.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.L.; methodology, H.L.; software, H.L. and Z.S.; validation, H.L.; formal analysis, H.L.; investigation, H.L. and H.Z.; resources, C.L.; data curation, C.L. and S.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, H.L.; writing—review and editing, H.L. and S.Q.; visualization, H.L. and Z.S.; supervision, S.Y.; project administration, C.L. and S.Y.; funding acquisition, C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The project is funded in part by the Guizhou Provincial Basic Research Program (Natural Science), under Grant No. ZK[2023]yiban139.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon approved request from the first author, due to institutional ethical research and data management processes.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

This appendix provides a detailed derivation of the stability analysis for the coupled closed-loop system.

Differentiating Equation (74) yields:

Substituting the exponential reaching laws and coupling relationships from each channel, the following inequality is obtained:

where .

Since the controllers are independently stable, the control laws are bounded. Therefore, there exists a positive constant such that:

Applying Young’s inequality to handle the coupling terms yields:

where can be ensured through design, and is a positive constant.

Let , then:

Appendix B

Table A1.

Quantitative metrics of simulation experimental results. This table clearly lists the quantitative metrics of Simulation Experiment 1 under ideal conditions. It compares four algorithms in Simulation Experiment 1, presenting results such as overshoot, root mean square error, and maximum deviation.

Table A1.

Quantitative metrics of simulation experimental results. This table clearly lists the quantitative metrics of Simulation Experiment 1 under ideal conditions. It compares four algorithms in Simulation Experiment 1, presenting results such as overshoot, root mean square error, and maximum deviation.

| PD Control | SM Control | The Proposed Method | Input Shaping | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| x-maximum overshoot | 4.13% | 0.34% | 0.01% | 0.12% |

| y-maximum overshoot | 3.80% | 0.14% | 0.13% | 0.11% |

| z-maximum overshoot | 2.10% | 0.09% | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| -Total Variation | 38.89 | 64.91 | 36.11 | 35.22 |

| -Total Variation | 0.13 | 1.61 | 0.39 | 1.59 |

| -Total Variation | 0.14 | 1.41 | 0.35 | 1.47 |

| -Total Variation | 0.02 | 0.47 | 0.16 | 0.48 |

| -RMSE | 4.28 | 6.96 | 1.78 | 2.17 |

| -Maximum Deviation (°) | 9.14 | 18.44 | 14.37 | 10.35 |

| -RMSE | 4.42 | 7.26 | 1.12 | 1.53 |

| -Maximum Deviation (°) | 9.59 | 13.22 | 11.44 | 5.80 |

Table A2.

Payload state estimation metrics under two simulation experimental environments. A comparative evaluation between the self-sensing strategy proposed in this study and single-gyroscope measurements is presented under both ideal and challenging conditions.

Table A2.

Payload state estimation metrics under two simulation experimental environments. A comparative evaluation between the self-sensing strategy proposed in this study and single-gyroscope measurements is presented under both ideal and challenging conditions.

| Simulation Conditions | Indicator | Kalman Filter | Gyroscope |

|---|---|---|---|

| Under Ideal Conditions | -RMSE | 0.68, 0.57 | 1.60, 1.71 |

| -Maximum Deviation | 5.07, 3.86 | 11.58, 11.68 | |

| Under Challenging Conditions | -RMSE | 0.72, 0.64 | 2.84, 2.40 |

| -Maximum Deviation | 4.81, 3.82 | 11.68, 12.56 |

References

- Sun, H.; Yan, H.; Hassanalian, M.; Zhang, J.; Abdelkefi, A. UAV Platforms for Data Acquisition and Intervention Practices in Forestry: Towards More Intelligent Applications. Aerospace 2023, 10, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmeseiry, N.; Alshaer, N.; Ismail, T. A Detailed Survey and Future Directions of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) with Potential Applications. Aerospace 2021, 8, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, M.; Jiang, D. Application of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles in Logistics: A Literature Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lammers, D.T.; Williams, J.M.; Conner, J.R.; Baird, E.; Rokayak, O.; McClellan, J.M.; Bingham, J.R.; Betzold, R.; Eckert, M.J. Airborne! UAV Delivery of Blood Products and Medical Logistics for Combat zones. Transfusion 2023, 63, S96–S104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Ullah, I.; Alkhalifah, A.; Rehman, S.U.; Shah, J.A.; Uddin, I.; Alsharif, M.H.; Algarni, F. A Provable and Privacy-Preserving Authentication Scheme for UAV-Enabled Intelligent Transportation Systems. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2022, 18, 3416–3425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, S.; Bokani, A.; Hassan, J. UAV-based Smart Agriculture: A Review of UAV Sensing and Applications. In Proceedings of the 2022 32nd International Telecommunication Networks and Applications Conference (ITNAC), Wellington, New Zealand, 30 November–2 December 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Shuaibu, A.S.; Mahmoud, A.S.; Sheltami, T.R. A Review of Last-Mile Delivery Optimization: Strategies, Technologies, Drone Integration, and Future Trends. Drones 2025, 9, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, H.M.; Akram, R.; Mukras, S.M.; Mahvouz, A.A. Recent Advances and Challenges in Controlling Quadrotors with Suspended Loads. Alex. Eng. J. 2023, 63, 253–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadr, S.; Moosavian, S.A.A.; Zarafshan, P. Dynamics Modeling and Control of a Quadrotor with Swing Load. J. Robot. 2014, 2014, 265897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Shan, J. Cooperative Transportation of Cable-suspended Slender Payload Using Two Quadrotors. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Unmanned Systems (ICUS), Beijing, China, 17–19 October 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Lu, J.; Huang, J. S Trajectory Based on Sliding Mode Control for Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Slung-load System. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2023, 2674, 012022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Shi, H.; Zhao, J.; Hu, Y. Research on Anti-swing Control Method of a Quadrotor System with Suspended Load under Elastic Rope Conditions. Control Eng. China 2024. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Yang, F.; Xu, Y.; Yuan, W.; Lu, Q. Deep Reinforcement Learning-based Swing-Free Trajectories Planning Algorithm for UAV with a Suspended Load. In Proceedings of the 2022 China Automation Congress (CAC), Xiamen, China, 25–27 November 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hua, H.; Fang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Qian, C. A New Nonlinear Control Strategy Embedded with Reinforcement Learning for a Multirotor Transporting a Suspended Payload. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2022, 27, 1174–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajapati, P.; Patidar, A.; Vashista, V. A Study on Reinforcement Learning based Control of Quadcopter with a Cable-suspended Payload. In Proceedings of the 2023 6th International Conference on Advances in Robotics, Ropar, India, 5–8 July 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ru, L.; Liu, J.; Chen, B.; Chen, D.; Fan, Z. Adaptive Sliding Mode Control of Quadrotor System with Elastic Load Connection of Unknown Mass. Drones 2024, 8, 708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Shao, J.; Huang, H.; Zheng, W.X. Modeling, Robust Control Design, and Experimental Verification for Quadrotor Carrying Cable-suspended Payload. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2024, 22, 6061–6075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, K.; Jia, J.; Yu, X.; Guo, L.; Xie, L. Multiple Observers based Anti-disturbance Control for a Quadrotor UAV Against Payload and Wind Disturbances. Control Eng. Pract. 2020, 102, 104560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Li, Y.; Yin, G.; Patton, R.J. Interval Observer-based Fault Detection and Isolation for Quadrotor UAV with Cable-Suspended Load. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2024, 54, 5876–5888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chu, J.; Liu, X. Anti-Swing Control for Quadrotor with Slung Load Using Integral Backstepping Sliding Mode Controller and Extended State Observer. In Proceedings of the 2024 China Automation Congress (CAC), Qingdao, China, 1–3 November 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, B.; Chen, H.; Zhang, X.; Qi, H. A Practical Optimal Controller for Underactuated Gantry Crane Systems. In Proceedings of the 2006 1st International Symposium on Systems and Control in Aerospace and Astronautics, Harbin, China, 19–21 January 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Aksjonov, A.; Vodovozov, V.; Petlenkov, E. Three-dimensional Crane Modelling and Control Using Euler-Lagrange State-space Approach and Anti-swing Fuzzy Logic. Electr. Control Commun. Eng. 2015, 9, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, L.A.; Kim, J.-J.; Lee, S.-G.; Lim, T.-G.; Nho, L.C. Second-order Sliding Mode Control of a 3D Overhead Crane with Uncertain System Parameters. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. 2014, 15, 811–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhong, H.; Gao, J.; Lv, Y.; Sha, J.; Liang, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y. A Nonlinear Trajectory Tracking Control Strategy for Quadrotor with Suspended Payload based on Force Sensor. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2023, 9, 704–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Z.-Y.; Li, S.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Q.-G. Adaptive Control for a Quadrotor Transporting a Cable-suspended Payload with Unknown Mass in the Presence of Rotor Downwash. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2021, 70, 8505–8518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukras, S.M.S.; Omar, H.M. Development of a 6-DOF Testing Platform for Multirotor Flying Vehicles with Suspended Loads. Aerospace 2021, 8, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B.; Fang, Y.; Sun, N. A Practical Visual Positioning Method for Industrial Overhead Crane Systems. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computer Vision Systems, Shenzhen, China, 10–11 September 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kajkouj, M.; Shaer, S.A.; Hatamleh, K. SURF and Image Processing Techniques Applied to an Autonomous Overhead Crane. In Proceedings of the 2016 24th Mediterranean Conference on Control and Automation (MED), Athens, Greece, 21–24 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhao, Y.; Song, B. Nonlinear Control of Quadrotor Suspension System Based on Extended State Observer. Acta Autom. Sin. 2023, 49, 1758–1770. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z. Flight Control and Realization of Quadrotor UAV with Suspended Payload. Master’s Thesis, Harbin Institute of Technology, Harbin, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, N. Research on Control Methods for Multi-Rotor UAV with Suspended Load. Master’s Thesis, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, Chengdu, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, X.; Liu, B.; Ye, H.; Pei, T.; Yu, H.; Fang, Y. A Review of Research on Cable-suspended Payload Transportation Systems by Rotorcraft Unmanned Aerial Vehicles. Control Decis. 2025, 40, 1079–1097. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Duan, Y.; Mao, P.; Lou, X.; Niu, X. 3D Path Planning for UAVs Based on Improved Bidirectional RRT Algorithm. Electron. Opt. Control 2024, 31, 13–19. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, H.; Lv, W. An Improved Bidirectional RRT* Algorithm for UAV Path Planning Based on Energy Consumption Constraints. In Proceedings of the 2024 6th International Conference on Robotics, Intelligent Control and Artificial Intelligence (RICAI), Nanjing, China, 6–8 December 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, K.; Jia, H. An Improved Bi-Directional RRT* Based Path Planning Algorithm for Mine UAV Inspection. In Proceedings of the 2023 China Automation Congress (CAC), Chongqing, China, 17–19 November 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, B. UAV Trajectory Generation Based on Integration of RRT and Minimum Snap Algorithms. In Proceedings of the 2020 China Automation Congress (CAC), Shanghai, China, 6–8 November 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Jiang, W.; Chen, Y.; Guan, W. UAV 3D Path Planning based on Improved Spider Wasp Optimization Algorithm. Electron. Meas. Technol. 2024, 47, 101–111. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Du, J.; Huang, B.; Jia, B. An Efficient UAV Coverage Path Planning Method for 3-D Structures. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 31869–31880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).