Unveiling the Hidden Cascade: Secondary Particle Generation in Hybrid Halide Perovskites Under Space-Relevant Ionizing Radiation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Calculation Details

3. Results

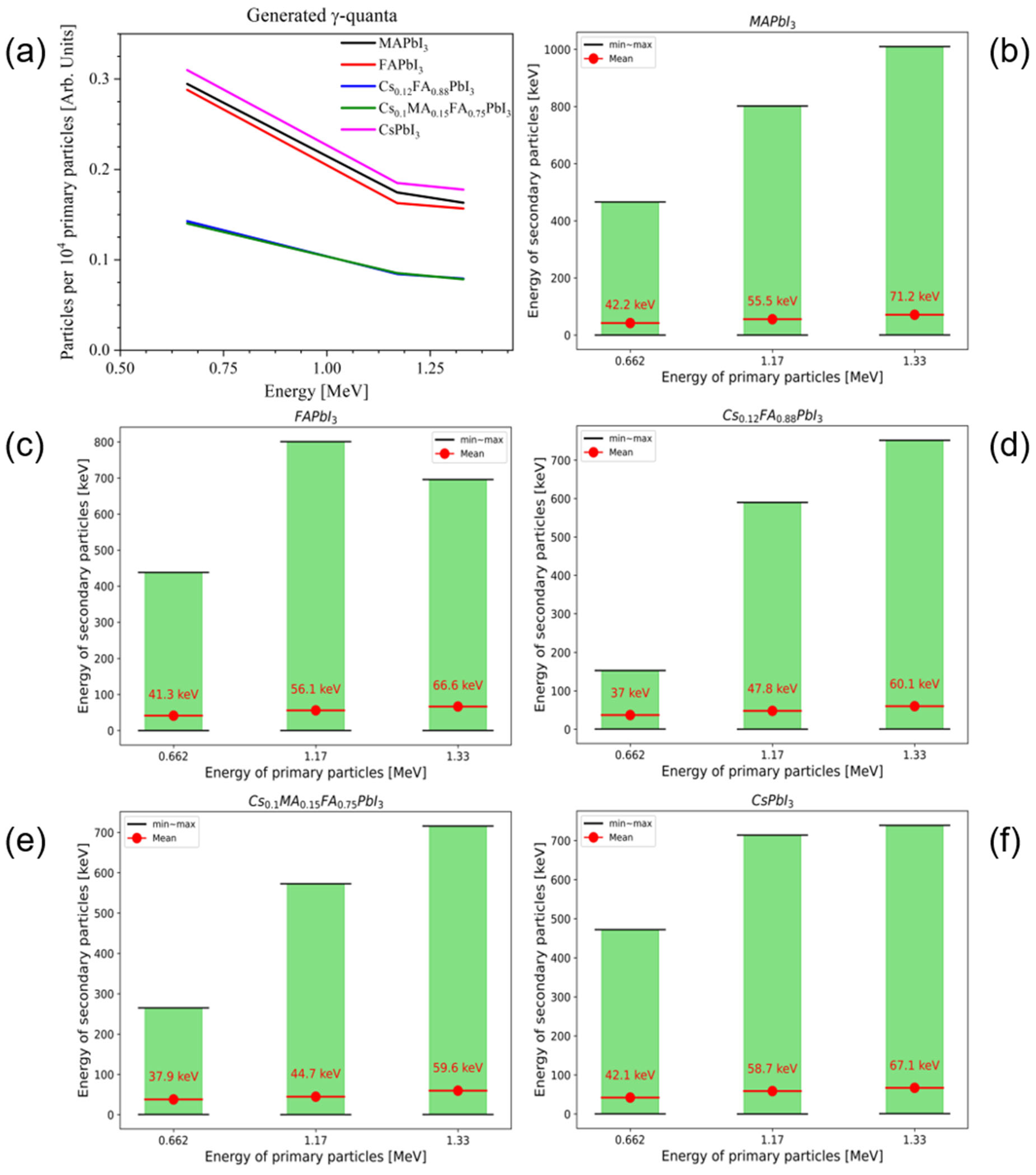

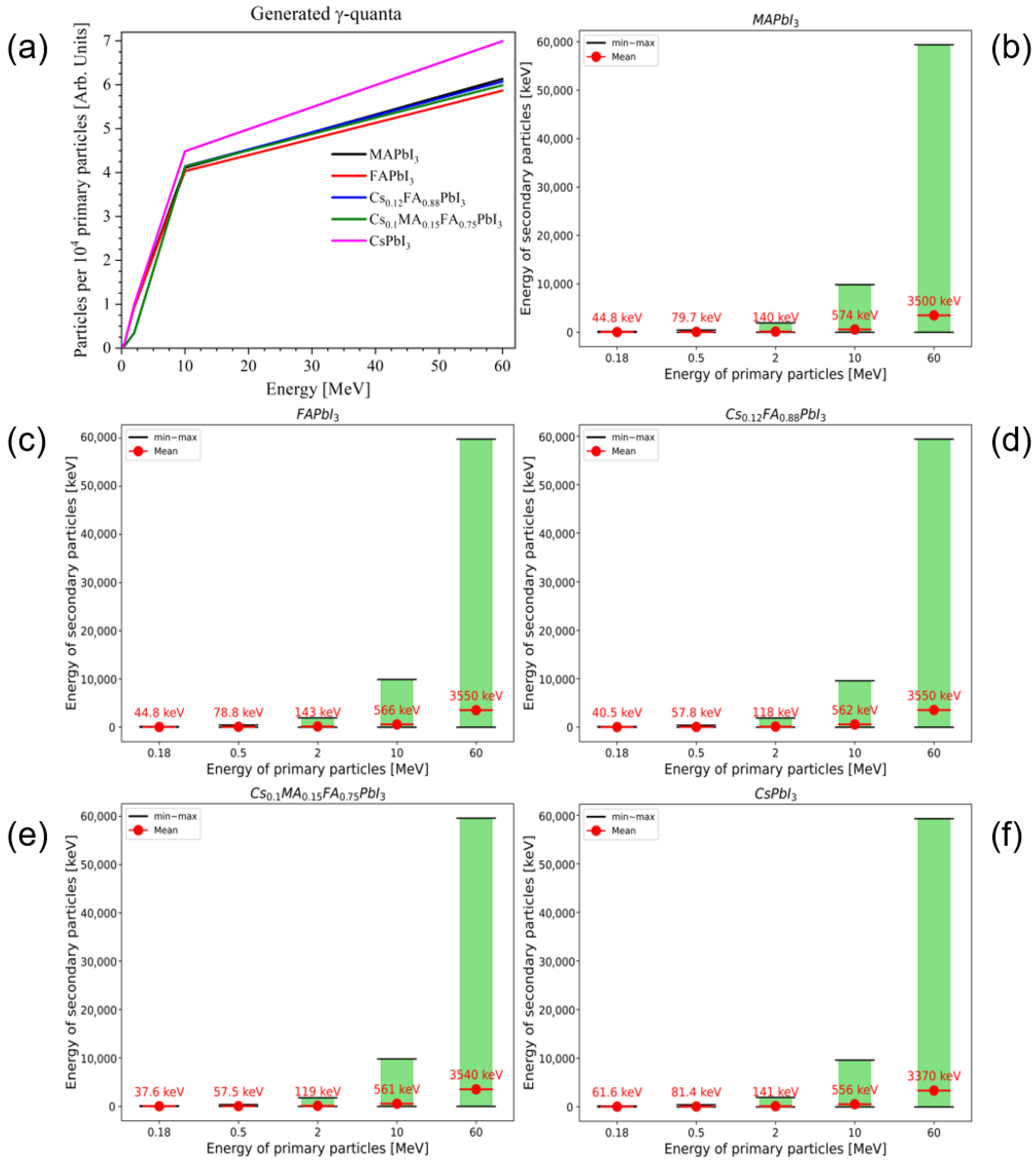

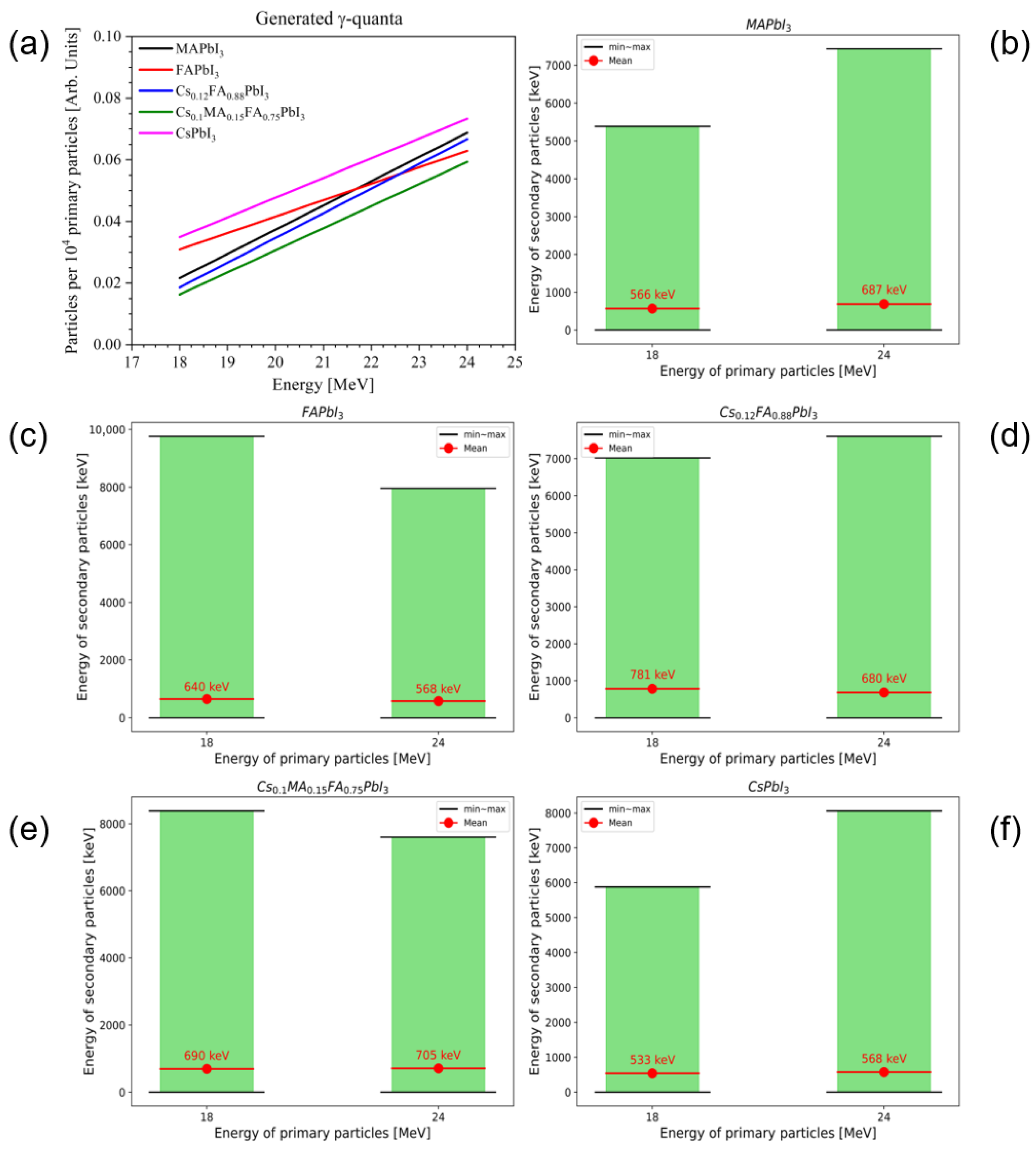

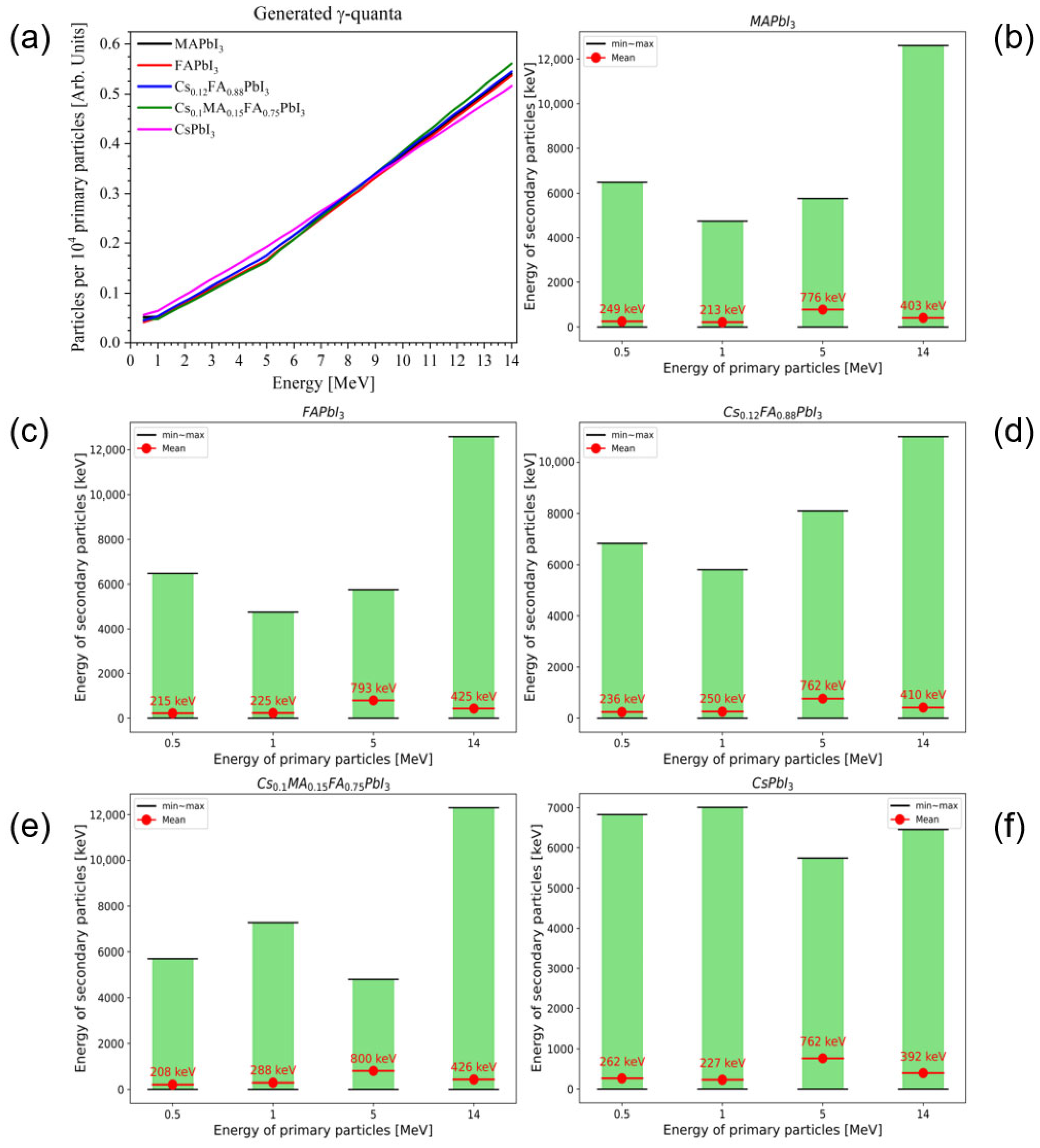

3.1. Secondary Photons

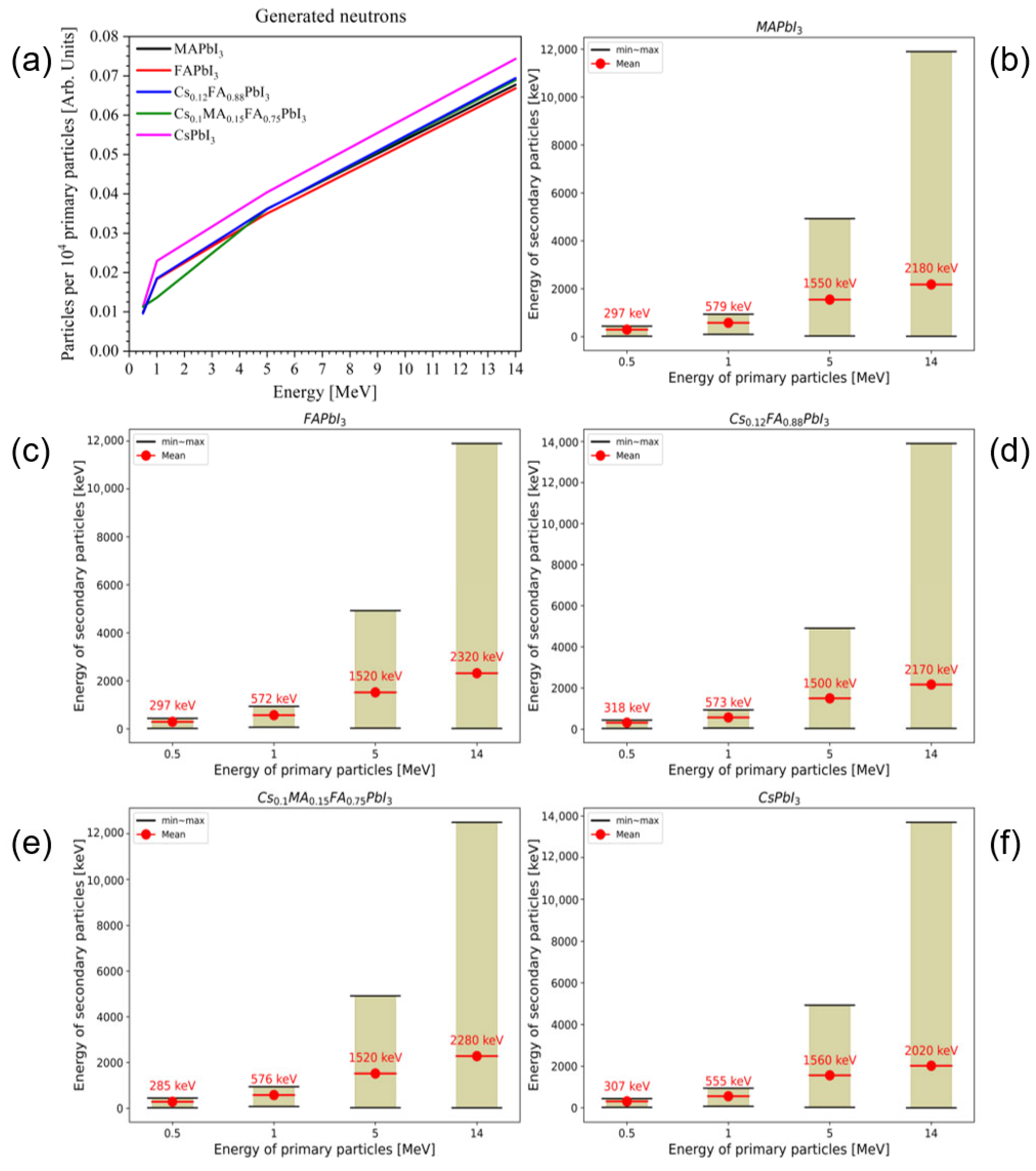

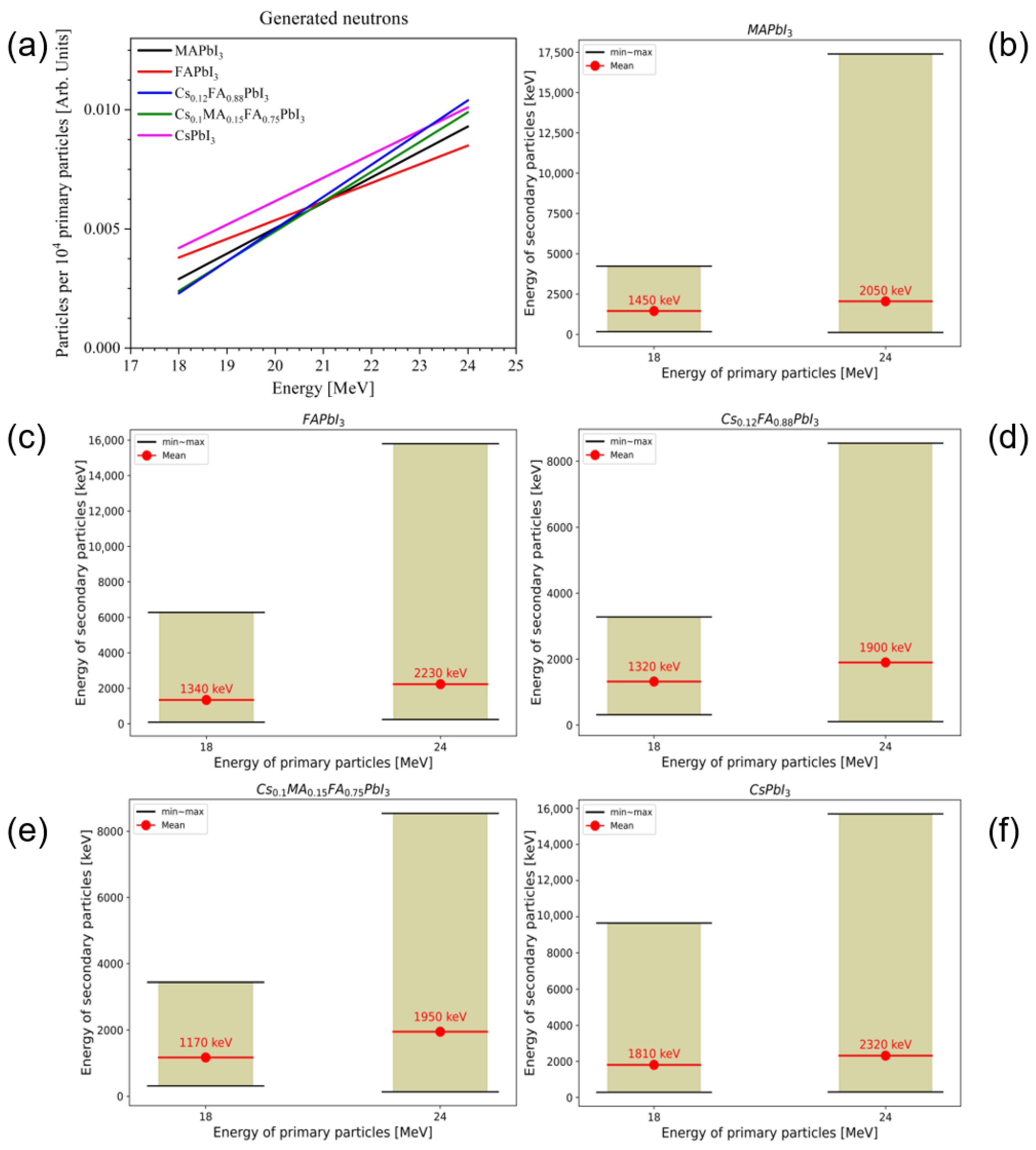

3.2. Secondary Neutrons

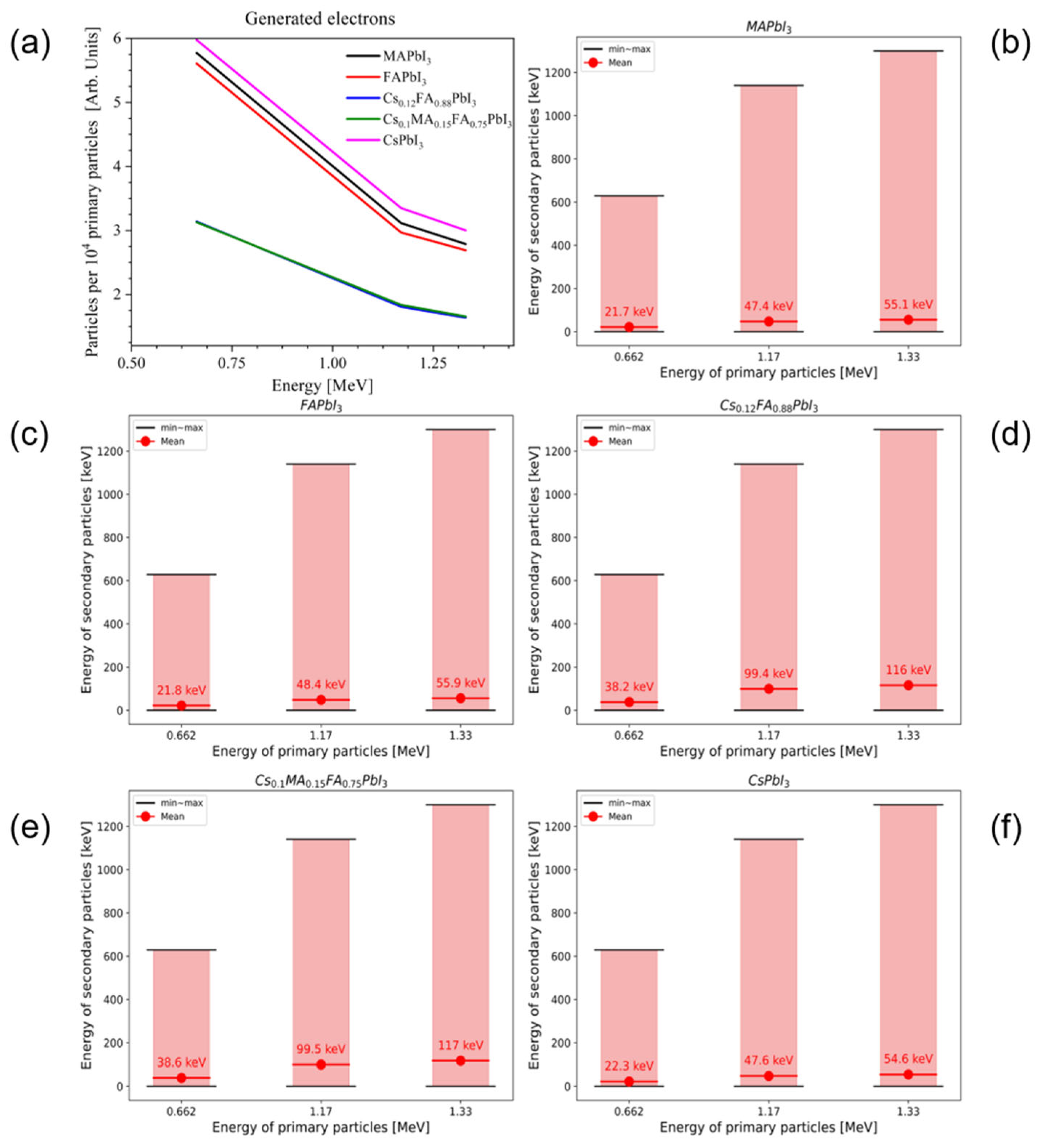

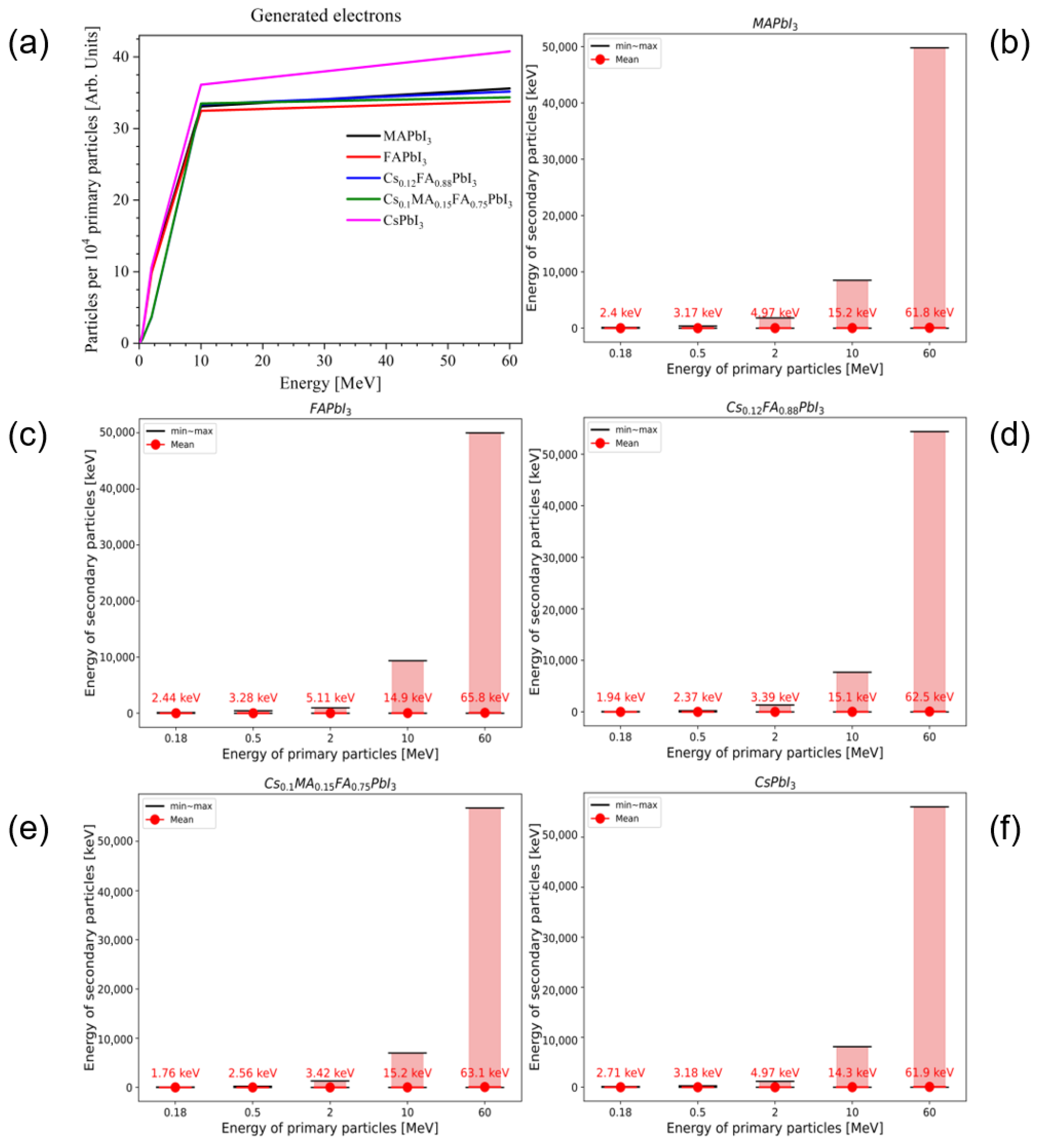

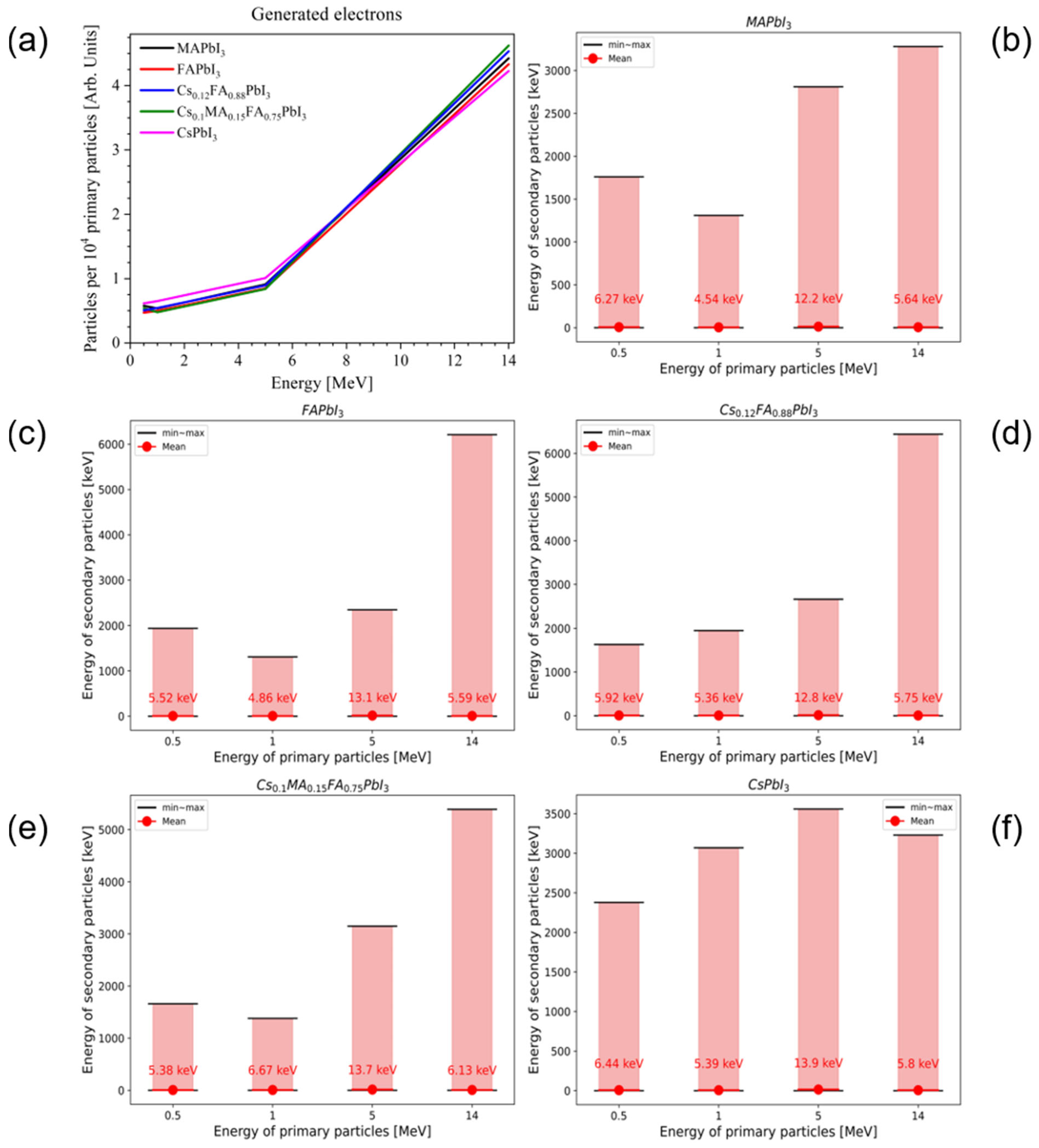

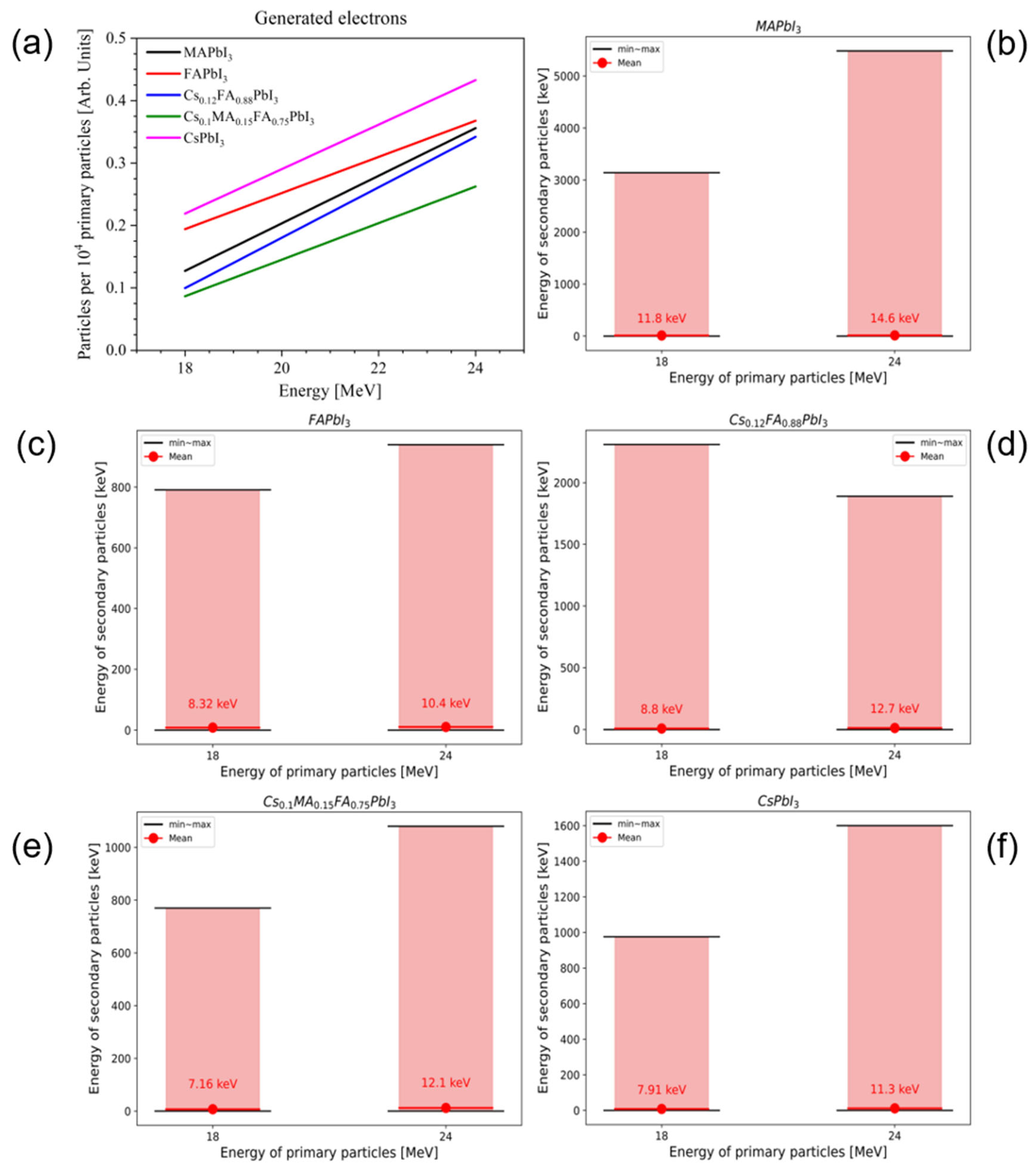

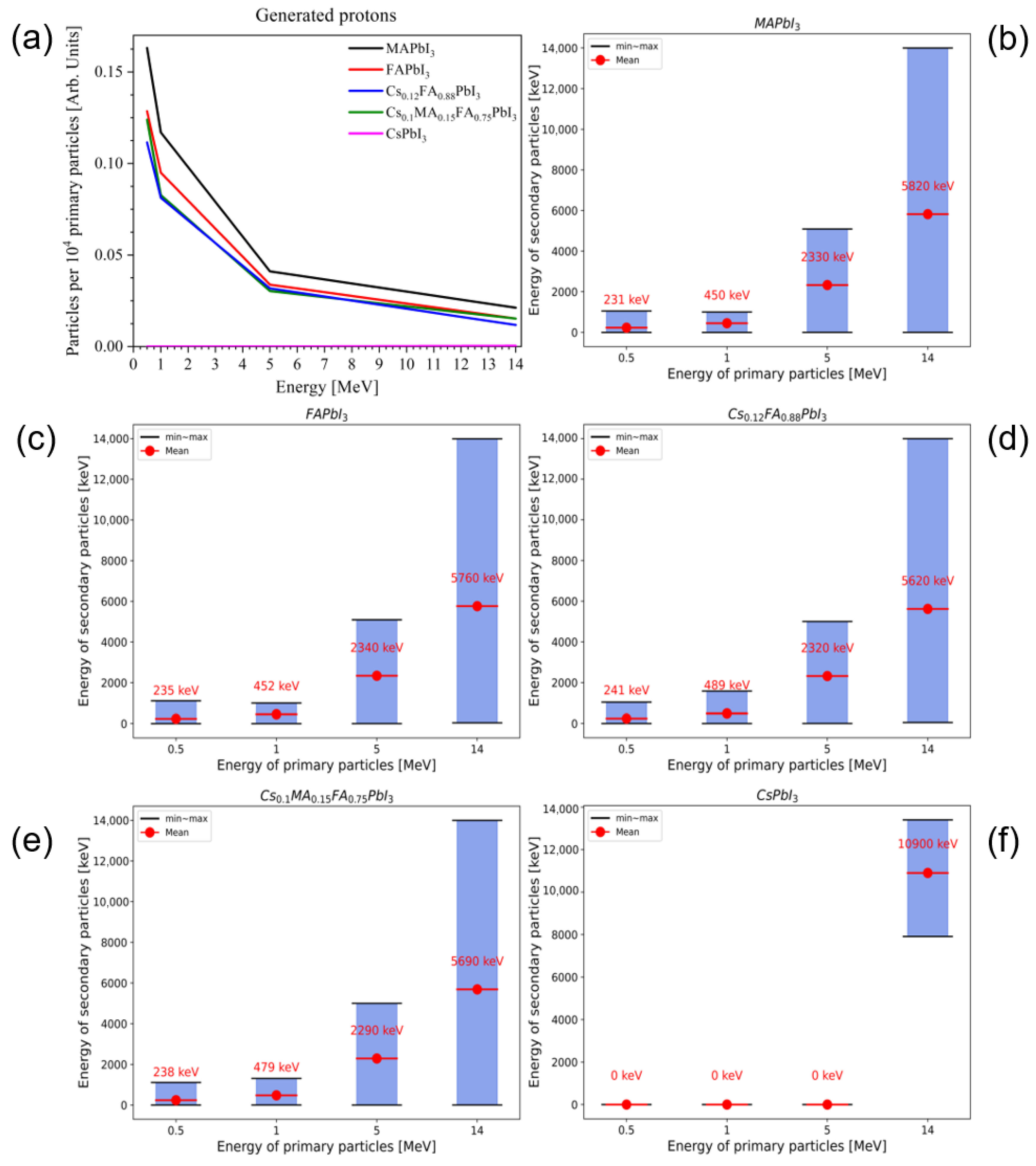

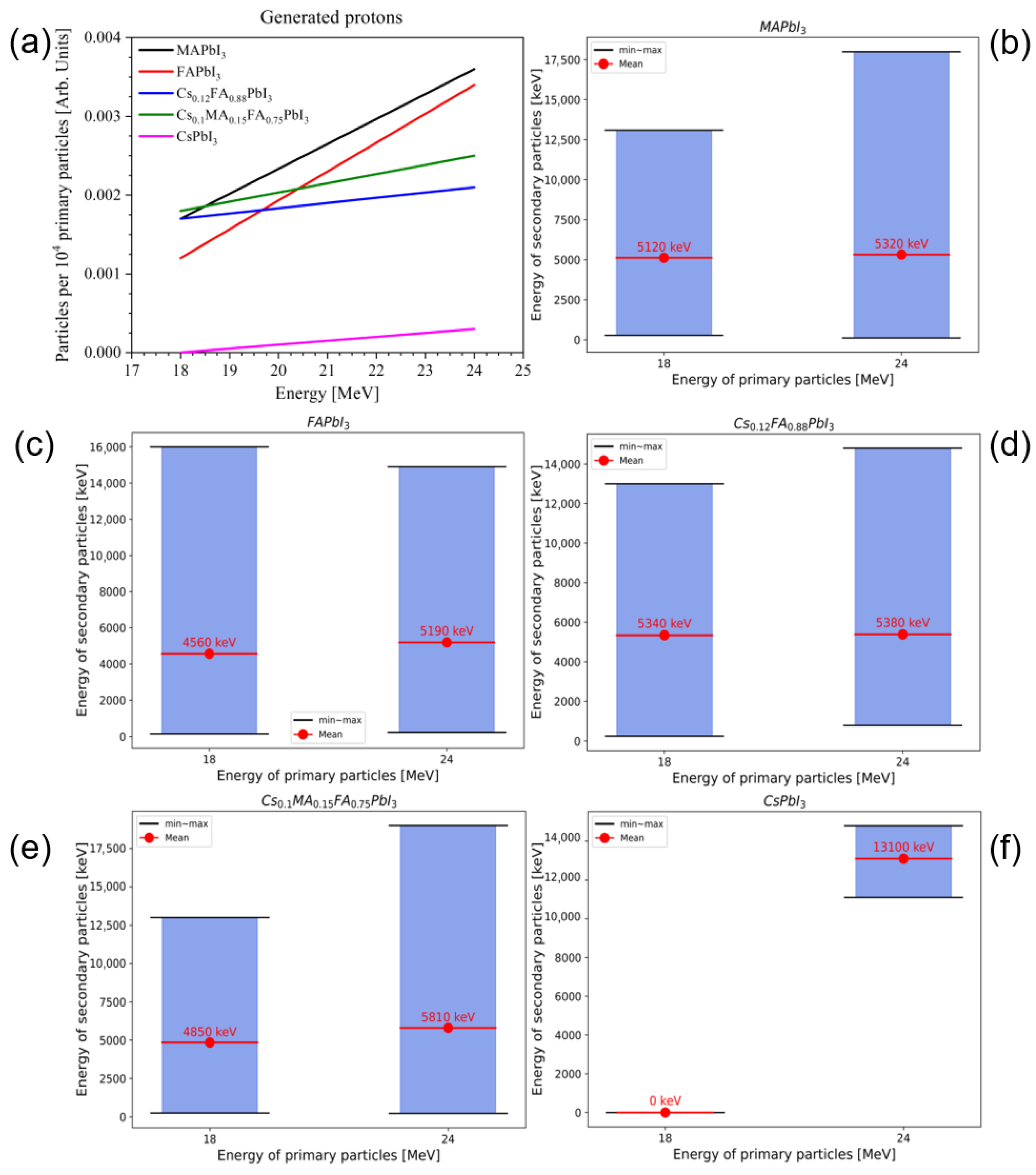

3.3. Secondary Charged Particles

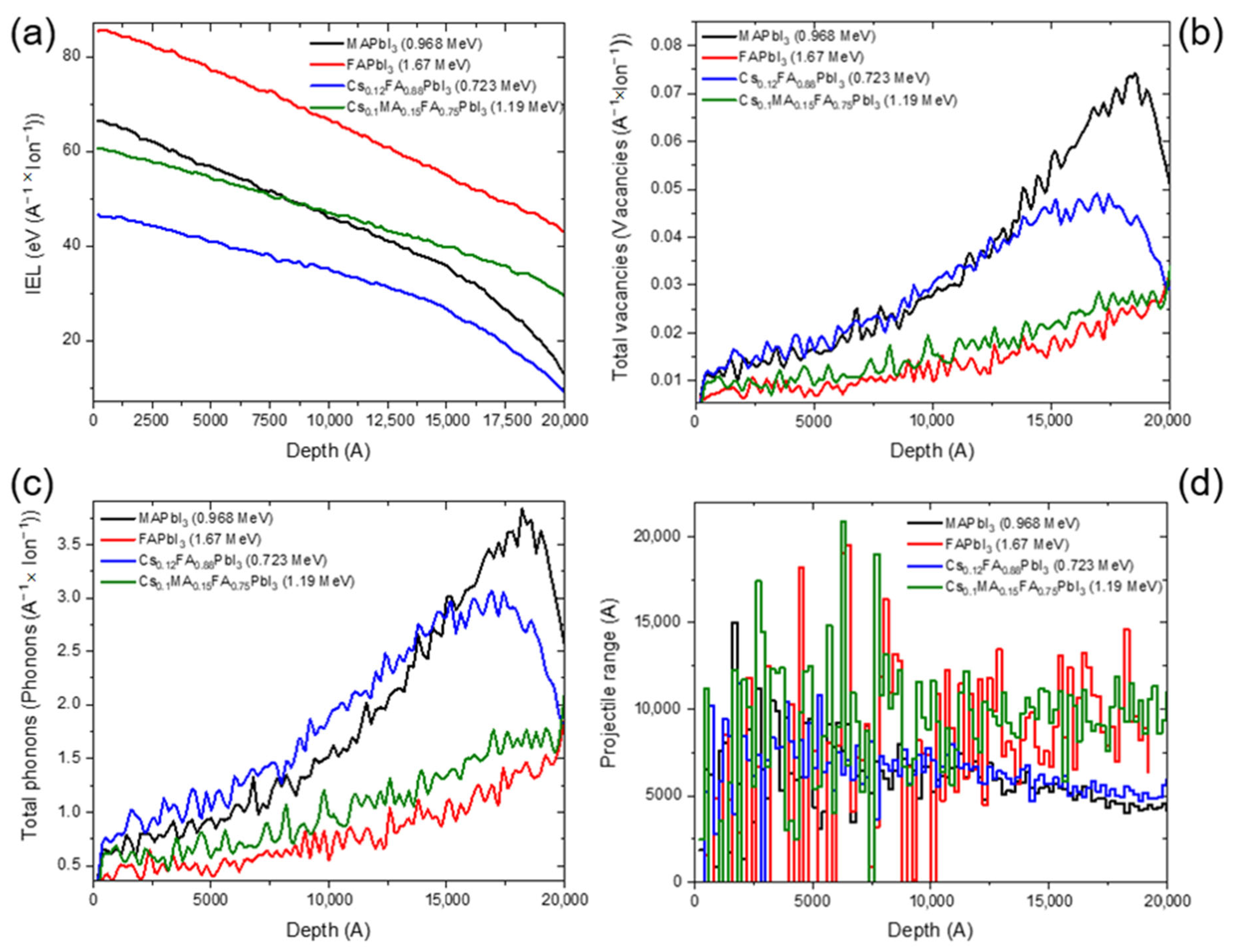

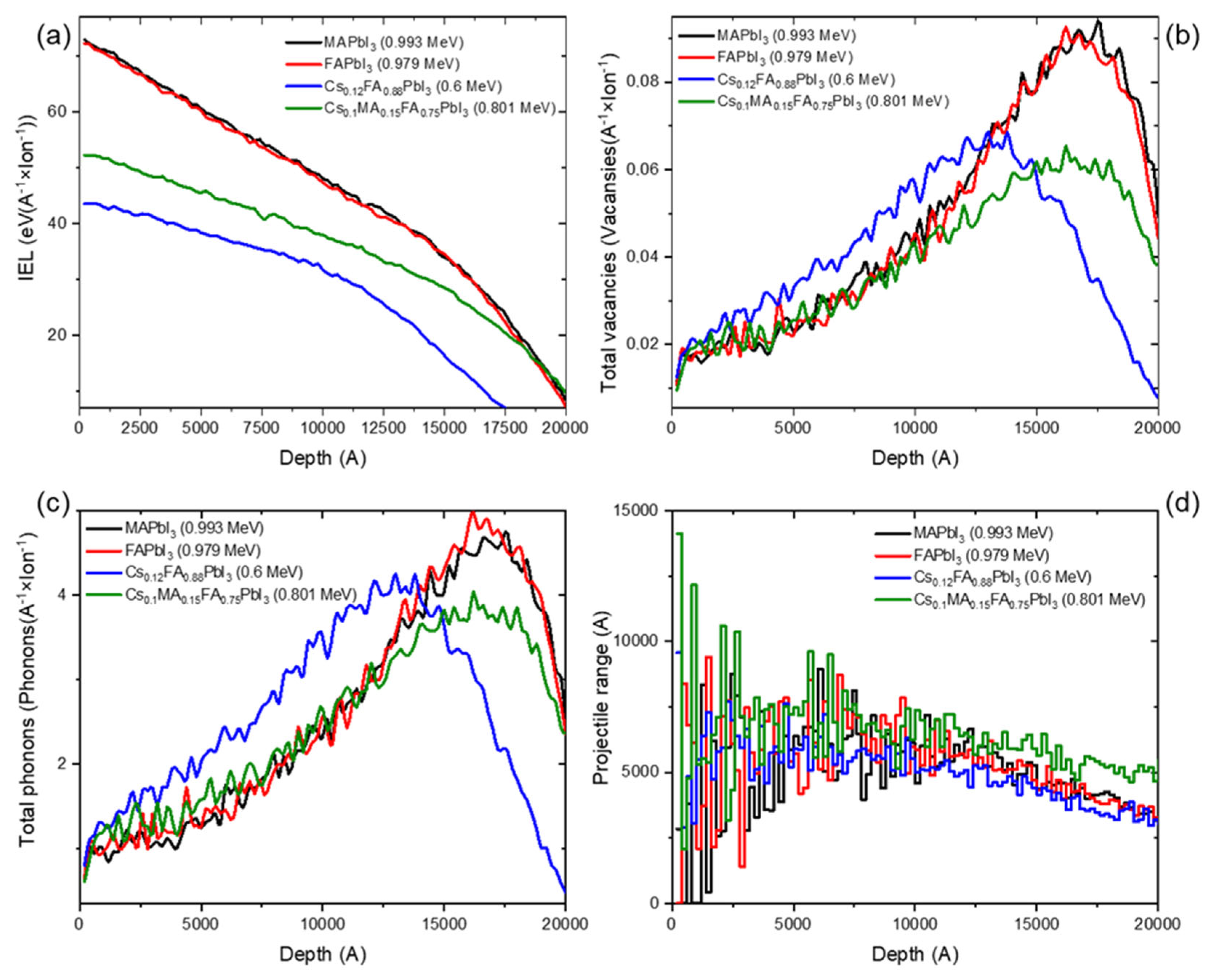

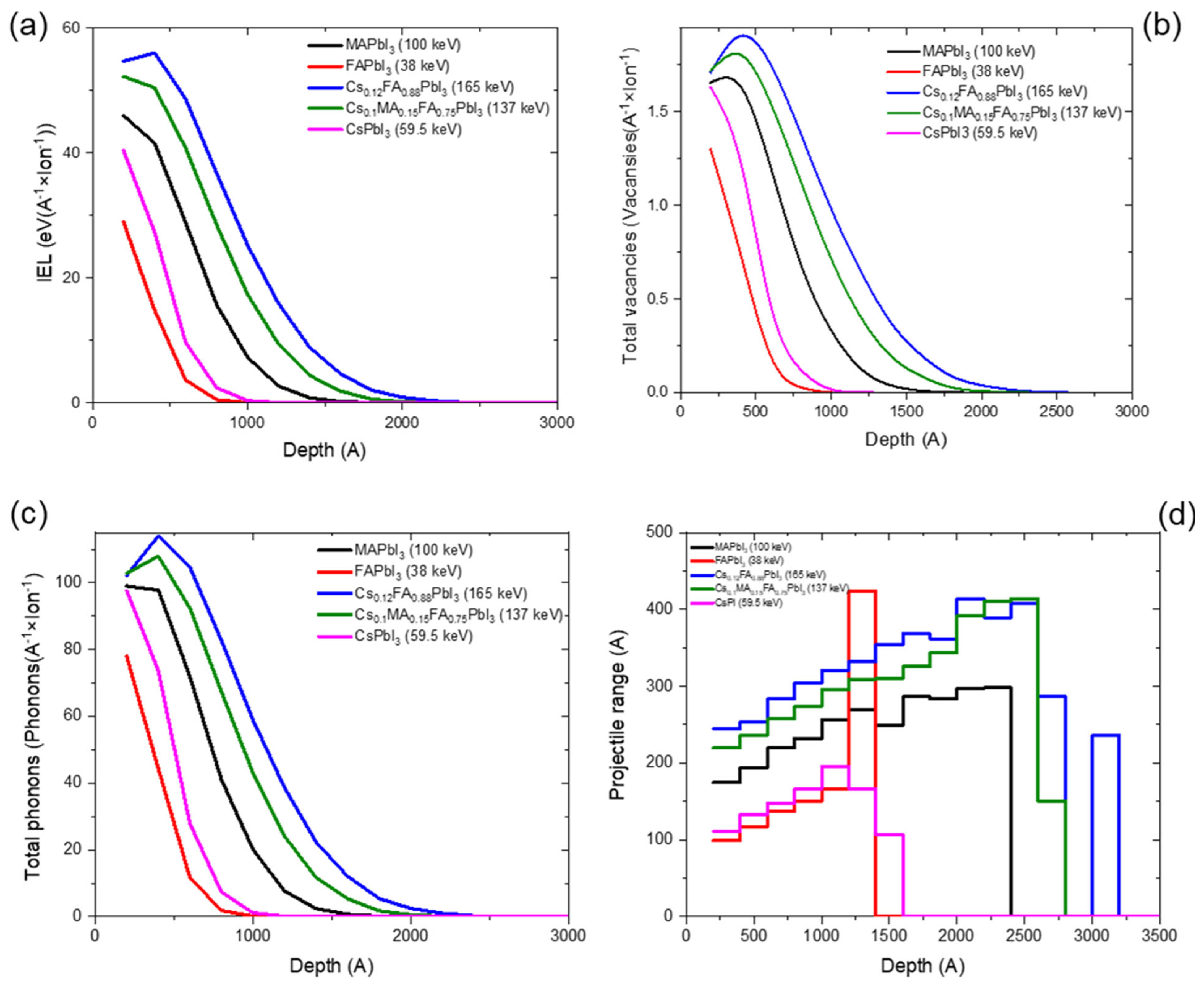

3.4. Secondary Heavy Particles

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, L.; Mei, L.; Wang, K.; Lv, Y.; Zhang, S.; Lian, Y.; Liu, X.; Ma, Z.; Xiao, G.; Liu, Q.; et al. Advances in the Application of Perovskite Materials. Nanomicro. Lett. 2023, 15, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bati, A.S.R.; Zhong, Y.L.; Burn, P.L.; Nazeeruddin, M.K.; Shaw, P.E.; Batmunkh, M. Next-Generation Applications for Integrated Perovskite Solar Cells. Commun. Mater. 2023, 4, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kim, J.; Kim, H.; Kim, C.; Kim, S.; Kim, C.; Lee, H.; Choi, B.; Muthu, C.; Kim, T.; et al. Brightening Deep-Blue Perovskite Light-Emitting Diodes: A Path to Rec. 2020. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadn8465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; Chen, C.; Wang, Y.; Yu, M.; Yang, J.; Ni, I.; Lin, B.; Zhidkov, I.S.; Kurmaev, E.Z.; Lu, Y.; et al. Realizing High Brightness Quasi-2D Perovskite Light-Emitting Diodes with Reduced Efficiency Roll-Off via Multifunctional Interface Engineering. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, e2302232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Wang, Y.; Huang, L.; Sun, W. Research Progress of High-Sensitivity Perovskite Photodetectors: A Review of Photodetectors: Noise, Structure, and Materials. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2022, 4, 1485–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Y.; Cheng, Q.; Song, Y.; Li, M. Micro-Nano Structure Functionalized Perovskite Optoelectronics: From Structure Functionalities to Device Applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2200385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best Research-Cell Efficiency Chart. Available online: https://www.nrel.gov/pv/cell-efficiency.html (accessed on 25 December 2024).

- Zhang, X.; Wu, S.; Zhang, H.; Jen, A.K.Y.; Zhan, Y.; Chu, J. Advances in Inverted Perovskite Solar Cells. Nat. Photonics 2024, 18, 1243–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Shen, Y.; Wang, F.; He, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Miao, Z.; Wu, Z. MAPbX3 Perovskite Single Crystals for Advanced Optoelectronic Applications: Progress, Challenges, and Perspective. Small 2025, 21, 2412809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, N.-G. Towards Stable, 30% Efficient Perovskite Solar Cells. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2024, 41, 3657–3668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, B.; Zhang, L.; Liu, N.; Zhang, T.; Liang, Y. Radiation Resistance Comparison of MAPbI3 and MAPbBr3 Perovskite Thin Films Under 100 KeV Proton Irradiation. Vacuum 2025, 243, 114832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huan, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, K.; Shen, Z.; Ni, W.; Zu, J.; Shao, Y. Advancements in Radiation Resistance and Reinforcement Strategies of Perovskite Solar Cells in Space Applications. J. Mater. Chem. A Mater. 2024, 12, 1910–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haris, M.P.U.; Xia, J.; Kazim, S.; Molenda, Z.; Hirsch, L.; Buffeteau, T.; Bassani, D.M.; Nazeeruddin, M.K.; Ahmad, S. Probing Proton Diffusion as a Guide to Environmental Stability in Powder-Engineered FAPbI3 and CsFAPbI3 Perovskites. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2023, 4, 101304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, T.; Liu, X.; Wang, X.; Zhao, Y. Advances to High-Performance Black-Phase FAPbI3 Perovskite for Efficient and Stable Photovoltaics. Small Struct. 2021, 2, 2000130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Shao, Z.; Li, C.; Pang, S.; Yan, Y.; Cui, G. Structural Properties and Stability of Inorganic CsPbI3 Perovskites. Small Struct. 2021, 2, 2000089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, N.; Angmo, D. Powering the Future: Opportunities and Obstacles in Lead-Halide Inorganic Perovskite Solar Cells. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, 2412666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klipfel, N.; Haris, M.P.U.; Kazim, S.; Sutanto, A.A.; Shibayama, N.; Kanda, H.; Asiri, A.M.; Momblona, C.; Ahmad, S.; Nazeeruddin, M.K. Structural and Photophysical Investigation of Single-Source Evaporation of CsFAPbI3 and FAPbI3 Perovskite Thin Films. J. Mater. Chem. C Mater. 2022, 10, 10075–10082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Pan, T.; Ning, Z. Strategies for Enhancing the Stability of Metal Halide Perovskite Towards Robust Solar Cells. Sci. China Mater. 2022, 65, 3190–3201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Zhang, L.; Liang, Y.; Xue, B.; Wang, D. Effects of Carrier Transport Layers on Performance Degradation in Perovskite Solar Cells Under Proton Irradiation. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2023, 6, 6673–6680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers. Photovoltaic Specialist Conference (PVSC); IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2015; ISBN 9781479979448. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, H.S.; Chiu, W.-H.; Chen, S.-H.; Wu, M.-C.; Lee, K.-M. Impact of Proton Radiation on the Performance of Single-Junction Perovskite Solar Cells for Space Applications. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2026, 295, 114015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, V.; Agresti, A.; Verduci, R.; D’Angelo, G. Advances in Perovskites for Photovoltaic Applications in Space. ACS Energy Lett. 2022, 7, 2490–2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y.; Wu, J.; Xu, G.; Yang, X.; Cai, R.; Gong, Q.; Zhu, R.; Huang, W. Perovskite Solar Cells for Space Applications: Progress and Challenges. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2006545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar, Y.Q.; Wrobel, F.; Autran, J.L.; García Alía, R. Radiation Environment and Their Effects on Electronics. In Single-Event Effects, from Space to Accelerator Environments; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.; Xue, B.; Xiao, S.; Wang, X. Chemical Stability of Metal Halide Perovskite Detectors. Inorganics 2024, 12, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinkiewicz, O.; Imaizumi, M.; Sapkota, S.B.; Ohshima, T.; Öz, S. Radiation Effects on the Performance of Flexible Perovskite Solar Cells for Space Applications. Emergent Mater. 2020, 3, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazawa, Y.; Kim, G.M.; Ishii, A.; Ikegami, M.; Miyasaka, T.; Suzuki, Y.; Yamamoto, T.; Ohshima, T.; Kanaya, S.; Toyota, H.; et al. Evaluation of Damage Coefficient for Minority-Carrier Diffusion Length of Triple-Cation Perovskite Solar Cells Under 1 MeV Electron Irradiation for Space Applications. J. Phys. Chem. C 2021, 125, 13131–13137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirmani, A.R.; Durant, B.K.; Grandidier, J.; Haegel, N.M.; Kelzenberg, M.D.; Lao, Y.M.; McGehee, M.D.; McMillon-Brown, L.; Ostrowski, D.P.; Peshek, T.J.; et al. Countdown to Perovskite Space Launch: Guidelines to Performing Relevant Radiation-Hardness Experiments. Joule 2022, 6, 1015–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmetyeva, A.V.; Zyryanov, S.S.; Novoselov, I.E.; Kukharenko, A.I.; Makarov, E.V.; Cholakh, S.O.; Kurmaev, E.Z.; Zhidkov, I.S. Proton Irradiation on Halide Perovskites: Numerical Calculations. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andričević, P.; Náfrádi, G.; Kollár, M.; Náfrádi, B.; Lilley, S.; Kinane, C.; Frajtag, P.; Sienkiewicz, A.; Pautz, A.; Horváth, E.; et al. Hybrid Halide Perovskite Neutron Detectors. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 17159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirmani, A.R.; Byers, T.A.; Ni, Z.; VanSant, K.; Saini, D.K.; Scheidt, R.; Zheng, X.; Kum, T.B.; Sellers, I.R.; McMillon-Brown, L.; et al. Unraveling Radiation Damage and Healing Mechanisms in Halide Perovskites Using Energy-Tuned Dual Irradiation Dosing. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwenzer, J.A.; Hellmann, T.; Nejand, B.A.; Hu, H.; Abzieher, T.; Schackmar, F.; Hossain, I.M.; Fassl, P.; Mayer, T.; Jaegermann, W.; et al. Thermal Stability and Cation Composition of Hybrid Organic–Inorganic Perovskites. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 15292–15304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, K.; Brabec, C.J.; Feng, Y. Phase Diagram and Stability of Mixed-Cation Lead Iodide Perovskites: A Theory and Experiment Combined Study. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2020, 4, 095401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, J.; Amako, K.; Apostolakis, J.; Arce, P.; Asai, M.; Aso, T.; Bagli, E.; Bagulya, A.; Banerjee, S.; Barrand, G.; et al. Recent Developments in Geant4. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 2016, 835, 186–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostinelli, S.; Allison, J.; Amako, K.; Apostolakis, J.; Araujo, H.; Arce, P.; Asai, M.; Axen, D.; Banerjee, S.; Barrand, G.; et al. Geant4—A Simulation Toolkit. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 2003, 506, 250–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, J.; Amako, K.; Apostolakis, J.; Araujo, H.; Arce Dubois, P.; Asai, M.; Barrand, G.; Capra, R.; Chauvie, S.; Chytracek, R.; et al. Geant4 Developments and Applications. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2006, 53, 270–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benton, E.R.; Benton, E. V Space Radiation Dosimetry in Low-Earth Orbit and Beyond. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 2001, 184, 255–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, J.W.; Badavi, F.F.; Kim, M.-H.Y.; Clowdsley, M.S.; Heinbockel, J.H.; Cucinotta, F.A.; Badhwar, G.D.; Huston, S.L. Natural and Induced Environment in Low Earth Orbit; National Aeronautics and Space Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2002.

- Morris, D.J.; Aarts, H.; Bennett, K.; Lockwood, J.A.; McConnell, M.L.; Ryan, J.M.; Schönfelder, V.; Steinle, H.; Peng, X. Neutron Measurements in Near-Earth Orbit with COMPTEL. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 1995, 100, 12243–12249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claret, A.; Brugger, M.; Combier, N.; Ferrari, A.; Laurent, P. FLUKA Calculation of the Neutron Albedo Encountered at Low Earth Orbits. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2014, 61, 3363–3370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gutiérrez, O.; Prieto, M.; Perales-Eceiza, A.; Ravanbakhsh, A.; Basile, M.; Guzmán, D. Toward the Use of Electronic Commercial Off-the-Shelf Devices in Space: Assessment of the True Radiation Environment in Low Earth Orbit (LEO). Electronics 2023, 12, 4058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahedi, Z.; Ezzati, A.O.; Sabri, H. Design of a Space Radiation Shield for Electronic Components of LEO Satellites Regarding Displacement Damage. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2024, 139, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, J.V.; Short, M.P.; Webster, P.T.; Morath, C.P. Orbital Equivalence of Terrestrial Radiation Tolerance Experiments. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2020, 67, 2382–2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ustinova, M.I.; Rasmetyeva, A.V.; Kukharenko, A.I.; Lobanov, M.V.; Kushch, P.P.; Emelianov, N.A.; Korchagin, D.V.; Kichigina, G.A.; Sarychev, M.N.; Kiryukhin, D.P.; et al. Exploring the Effects of the Alkaline Earth Metal Cations on the Electronic Structure, Photostability and Radiation Hardness of Lead Halide Perovskites. Mater. Today Energy 2024, 45, 101687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yudin, V.I.; Lozhkin, M.S.; Shurukhina, A.V.; Emeline, A.V.; Kapitonov, Y.V. Photoluminescence Manipulation by Ion Beam Irradiation in CsPbBr3 Halide Perovskite Single Crystals. J. Phys. Chem. C 2019, 123, 21130–21134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seid, B.A.; Sarisozen, S.; Peña-Camargo, F.; Ozen, S.; Gutierrez-Partida, E.; Solano, E.; Steele, J.A.; Stolterfoht, M.; Neher, D.; Lang, F. Understanding and Mitigating Atomic Oxygen-Induced Degradation of Perovskite Solar Cells for Near-Earth Space Applications. Small 2024, 20, e2311097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boldyreva, A.G.; Akbulatov, A.F.; Tsarev, S.A.; Luchkin, S.Y.; Zhidkov, I.S.; Kurmaev, E.Z.; Stevenson, K.J.; Petrov, V.G.; Troshin, P.A. γ-Ray-Induced Degradation in the Triple-Cation Perovskite Solar Cells. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2019, 10, 813–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, S.A.; Stash, A.I. Influence of Neutron Irradiation on the Characteristics of Phase Transitions in Multifunctional Materials with a Perovskite Structure (A Review). Russ. J. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 65, 1789–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ustinova, M.I.; Frolova, L.A.; Rasmetyeva, A.V.; Emelianov, N.A.; Sarychev, M.N.; Kushch, P.P.; Dremova, N.N.; Kichigina, G.A.; Kukharenko, A.I.; Kiryukhin, D.P.; et al. Enhanced Radiation Hardness of Lead Halide Perovskite Absorber Materials via Incorporation of Dy2+ Cations. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 493, 152522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ustinova, M.I.; Frolova, L.A.; Rasmetyeva, A.V.; Emelianov, N.A.; Sarychev, M.N.; Shilov, G.V.; Kushch, P.P.; Dremova, N.N.; Kichigina, G.A.; Kukharenko, A.I.; et al. A Europium Shuttle for Launching Perovskites to Space: Using Eu2+/Eu3+ Redox Chemistry to Boost Photostability and Radiation Hardness of Complex Lead Halides. J. Mater. Chem. A Mater. 2024, 12, 13219–13230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boldyreva, A.G.; Frolova, L.A.; Zhidkov, I.S.; Gutsev, L.G.; Kurmaev, E.Z.; Ramachandran, B.R.; Petrov, V.G.; Stevenson, K.J.; Aldoshin, S.M.; Troshin, P.A. Unravelling the Material Composition Effects on the Gamma Ray Stability of Lead Halide Perovskite Solar Cells: MAPbI3 Breaks the Records. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2020, 11, 2630–2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Tan, Q.; Hao, J. Analysis of Displacement Damage Mechanism and Simulation Proton Irradiation on GaAs. AIP Adv. 2022, 12, 95304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erickson, S.; Lum, C.; Stephens, K.; Parashar, M.; Saini, D.K.; Rout, B.; Park, C.; Peshek, T.J.; McMillon-Brown, L.; Ghosh, S. Elucidating Early Proton Irradiation Effects in Metal Halide Perovskites via Photoluminescence Spectroscopy. iScience 2025, 28, 111586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozerova, V.V.; Emelianov, N.A.; Kiryukhin, D.P.; Kushch, P.P.; Shilov, G.V.; Kichigina, G.A.; Aldoshin, S.M.; Frolova, L.A.; Troshin, P.A. Exploring the Limits: Degradation Behavior of Lead Halide Perovskite Films under Exposure to Ultrahigh Doses of γ Rays of Up to 10 MGy. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2023, 14, 743–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zykov, V.M.; Evdokimov, K.E.; Neyman, D.A.; Vladimirov, A.M.; Voronova, G.A. Mechanism of Local Damage to Photovoltaic Cells by Geomagnetic Plasma Electrons. Zhurnal Tekhnicheskoi Fiz. 2025, 95, 1392–1403. [Google Scholar]

- Svanström, S.; García Fernández, A.; Sloboda, T.; Jacobsson, T.J.; Rensmo, H.; Cappel, U.B. X-Ray Stability and Degradation Mechanism of Lead Halide Perovskites and Lead Halides. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2021, 23, 12479–12489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ustinova, M.I.; Sarychev, M.N.; Emelianov, N.A.; Li, Y.; Zhuo, Y.; Zheng, T.; Babenko, S.D.; Tarasov, E.D.; Kushch, P.P.; Dremova, N.N.; et al. Towards Better Perovskite Absorber Materials: Cu+ Doping Improves Photostability and Radiation Hardness of Complex Lead Halides. EcoMat 2025, 7, e12512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itoh, Y.; Peng, Z.L.; Lee, K.H.; Ishii, M.; Goto, A.; Nakanishi, N.; Kase, M.; Ito, Y. Slow Positron Beam Production by Irradiation of p+, d+, and He2+ on Various Targets. Appl. Surf. Sci. 1997, 116, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, J.M.; Hulett, L.D.; Pendyala, S. Low Energy Positrons from Metal Surfaces. Surf. Interface Anal. 1980, 2, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Link, A.; Canning, D.; Fooks, J.A.; Kempler, P.A.; Kerr, S.; Kim, J.; Krieger, M.; Lewis, N.S.; Wallace, R.; et al. Enhancing Positron Production Using Front Surface Target Structures. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2021, 118, 94101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prelas, M. Radiation Interaction with Matter. In Nuclear-Pumped Lasers; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 63–100. [Google Scholar]

- Mrówczyński, S. Interaction of Elementary Atoms with Matter. Phys. Rev. A (Coll Park) 1986, 33, 1549–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percival, I.C.; Richards, D. The Theory of Collisions between Charged Particles and Highly Excited Atoms. In Advances in Atomic and Molecular Physics; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1976; pp. 1–82. [Google Scholar]

- Bethe, H.A. Nuclear Physics B. Nuclear Dynamics, Theoretical. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1937, 9, 69–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podgoršak, E.B. Interaction of Neutrons with Matter. In Compendium to Radiation Physics for Medical Physicists; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 581–635. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Novoselov, I.E.; Cholakh, S.O.; Zhidkov, I.S. Unveiling the Hidden Cascade: Secondary Particle Generation in Hybrid Halide Perovskites Under Space-Relevant Ionizing Radiation. Aerospace 2025, 12, 1015. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace12111015

Novoselov IE, Cholakh SO, Zhidkov IS. Unveiling the Hidden Cascade: Secondary Particle Generation in Hybrid Halide Perovskites Under Space-Relevant Ionizing Radiation. Aerospace. 2025; 12(11):1015. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace12111015

Chicago/Turabian StyleNovoselov, Ivan E., Seif O. Cholakh, and Ivan S. Zhidkov. 2025. "Unveiling the Hidden Cascade: Secondary Particle Generation in Hybrid Halide Perovskites Under Space-Relevant Ionizing Radiation" Aerospace 12, no. 11: 1015. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace12111015

APA StyleNovoselov, I. E., Cholakh, S. O., & Zhidkov, I. S. (2025). Unveiling the Hidden Cascade: Secondary Particle Generation in Hybrid Halide Perovskites Under Space-Relevant Ionizing Radiation. Aerospace, 12(11), 1015. https://doi.org/10.3390/aerospace12111015