Wither Adaptation Action

Abstract

1. Introduction

“Adaptation: in human systems, the process of adjustment to actual or expected climate and its effects, in order to moderate harm or exploit beneficial opportunities. In natural systems, adaptation is the process of adjustment to the actual climate and its effects; human intervention may facilitate adjustment to the expected climate and its effects”.[15] (p. 4)

2. Literature Review

2.1. Overview of Australian Adaptation

- To drive investment and action through collaboration;

- To improve climate information and services;

- To assess progress and improve over time.

2.2. Facilitators and Barriers to Action on Adaptation

2.2.1. Early Perspectives

2.2.2. More Recent Literature on Barriers

3. Material and Methods

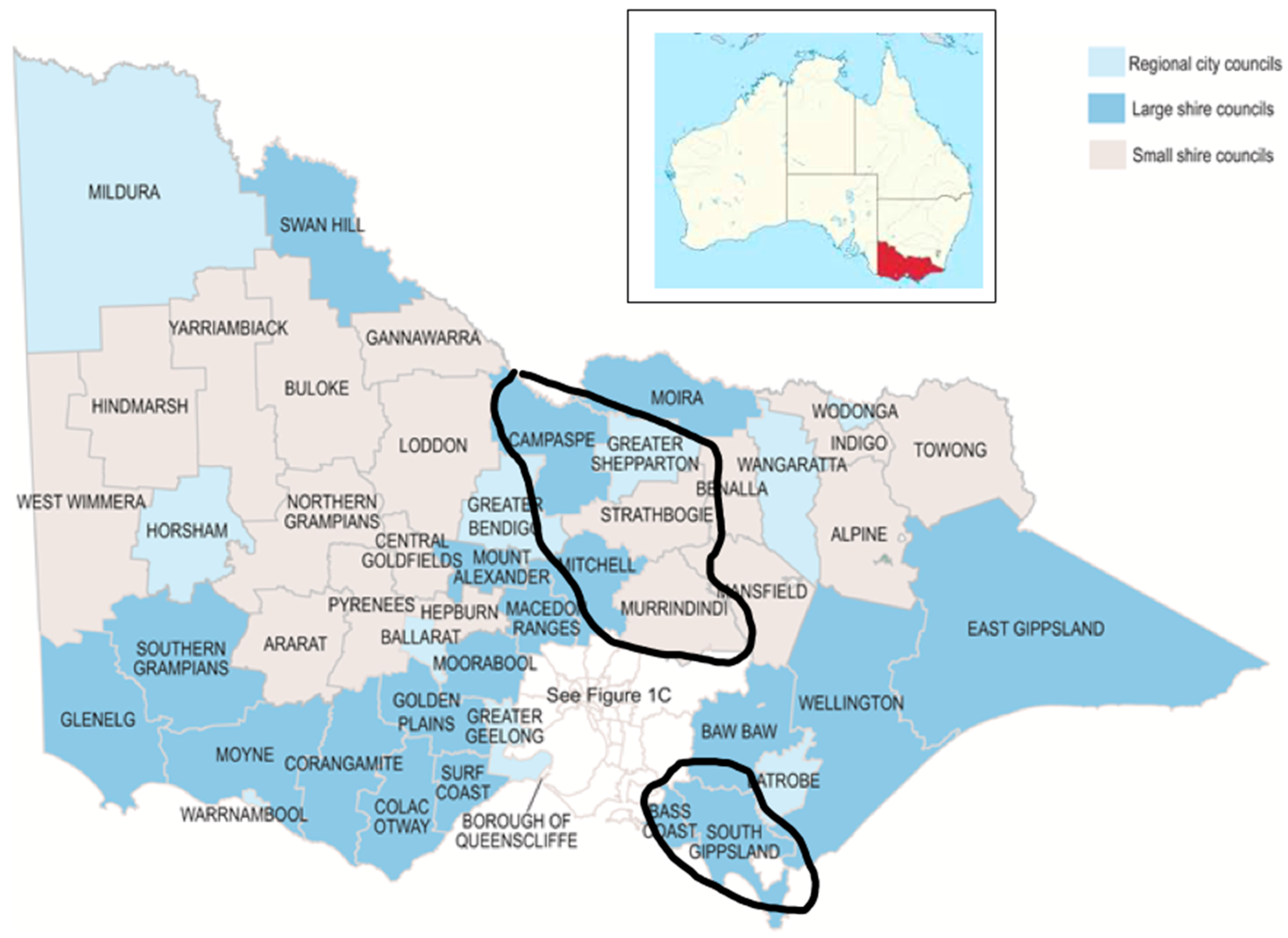

- The 2012 workshops in the Bass Coast and South Gippsland region in southern Victoria, an area of 4155 square kilometres;

- The 2022 workshops in north central Victoria, known as the Goulburn Broken Catchment region, 24,317 square kilometres, covering five local government areas, most participants coming from Greater Shepparton and Strathbogie.

4. Results

4.1. Overview

4.2. Collaborations and Relationships

4.2.1. 2012

4.2.2. 2022

4.3. Priorities for Adaptation Action

4.3.1. 2012

4.3.2. 2022

4.4. Forces Working Against Adaptation Action

4.4.1. 2012

4.4.2. 2022

4.5. Forces Facilitating Adaptation Action

4.5.1. 2012

4.5.2. 2022

4.6. Steps That Could Be Taken to Strengthen Adaptation Action

4.6.1. 2012

- Adaptation should be strategic and planned, and include both the government and community;

- The community needs to be empowered (sanctioned/galvanised) to act;

- Local decision-making should include all parties;

- A specified local group should be established to organise and coordinate adaptation;

- Funding should be provided to local government for adaptation.

4.6.2. 2022

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ives, M. Wildfire Smoke: Millions in North America Face Hazardous Air Quality, Driven by Fires in Canada. New York Times. 2023. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/live/2023/06/06/us/canada-wildfires-smoke-air-quality?name=styln-wildfiressmoke®ion=TOP_BANNER&block=storyline_menu_recirc&action=click&pgtype=Article&variant=undefined (accessed on 7 June 2024).

- Milman, O. After a Record Year of Wildfires, Will Canada Ever Be the Same Again? The Guardian. 2023. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/nov/09/canada-wildfire-record-climate-crisis (accessed on 9 November 2024).

- Natural Resources Canada. National Wildland Fire Situation Report. 2024. Available online: https://cwfis.cfs.nrcan.gc.ca/report (accessed on 28 June 2024).

- Bruyère, C.; Holland, G.; Prein, A.; Done, J.; Buckley, B.; Chan, P.; Leplastrier, M.; Dyer, A. Severe Weather in a Changing Climate; Insurance Australia Group (IAG): Sydney, Australia, 2019; Available online: https://www.iag.com.au/sites/default/files/Documents/Reports/Severe-weather-in-a-changing-climate-report-151119.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Evans, S. Why Coal Use Must Plummet This Decade to Keep Global Warming Below 1.5C. CarbonBrief. 2020. Available online: https://www.carbonbrief.org/analysis-why-coal-use-must-plummet-this-decade-to-keep-global-warming-below-1-5c/ (accessed on 18 July 2024).

- Armstrong McKay, D.I.; Staal, A.; Abrams, J.F.; Winkelmann, R.; Sakschewski, B.; Loriani, S.; Fetzer, I.; Cornell, S.E.; Rockström, J.; Lenton, T.M. Exceeding 1.5 °C global warming could trigger multiple climate tipping points. Science 2022, 377, 6611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tollefson, J. Catastrophic change looms as earth nears climate ‘tipping points’. Nature 2023, 624, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrington, D. World on Brink of Five ‘Disastrous’ Climate Tipping Points, Study Finds. The Guardian. 2022. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/sep/08/world-on-brink-five-climate-tipping-points-study-finds (accessed on 9 September 2022).

- Bu, M.; Comfort, L.K.; Guttman, D.; He, C.; Jing, Y.; Kihslinger, R.; Knopman, D.; Li, W.; Lu, B.; Losos, E.; et al. Adapting to the Impacts of Climate Change: A Comparative Study of Governance Processes in Australia, China, and the United States; National Academy of Public Administration: Washington, DC, USA, April 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Berrang-Ford, L.; Siders, A.; Lesnikowski, A.; Fischer, A. A systematic global stocktake of evidence on human adaptation to climate change. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2021, 11, 989–1000. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41558-021-01170-y (accessed on 1 October 2024). [CrossRef]

- The White House. State of the Union: President Biden’s State of the Union Address; The White House: Washington, DC, USA, 2024.

- Spencer, M.; Stanley, J.; Wohlgezogen, F.; Zhu-Maguire, I. Report on the Goulburn Broken Catchment Workshop on Adaptation to Climate Change; Melbourne University: Melbourne, Australia, 2022. Available online: https://www.strathbogieranges.org.au/wp-content/uploads/Spencer-et-al.-2022-Strathbogie-Ranges-Adaptation-to-Climate-Change-Report-V.5.4-.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2024).

- Stanley, J.; Birrell, B.; Brain, P.; Varey, M.; Duffy, M.; Ferraro, S.; Fisher, S.; Griggs, D.; Hall, A.; Kestin, T.; et al. What Would a Climate-Adapted Settlement Look like in 2030? A Case Study of Inverloch and Sandy Point; National Climate Change Adaptation Research Facility: Gold Coast, Australia, 2013; Available online: https://apo.org.au/node/34644 (accessed on 22 July 2024).

- Gergis, J. An Intergenerational Crime Against Humanity: What Will It Take for Political Leaders to Start Taking Climate Change Seriously? The Conversation. 2023. Available online: https://theconversation.com/an-intergenerational-crime-against-humanity-what-will-it-take-for-political-leaders-to-start-taking-climate-change-seriously (accessed on 4 June 2024).

- IPCC. How to Adapt to a Changing Climate: Summary for All. 2022. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/downloads/outreach/IPCC_AR6_WGII_SummaryForAll_Adaptation.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- Brooke, C.; Hennessy, K. Climate change impacts in Gippsland. Appendix 1. In Climate Change Impacts and Adaptation in Gippsland; Fisher, S., Ed.; CSIRO: Marsfield, Australia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, S. Climate Change Impacts and Adaptation in Gippsland Project: A Regional Pilot Project Initiating Gippsland’s Response to Climate Change; Greenhouse Policy Unit. December, Victorian Department of Sustainability & Environment: East Melbourne, Australia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Doherty, B. As the waves break, so does the heart of one man’s dream. The Age Newspaper, 28 June 2008; 1. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler, S. State and municipal climate change plans: The First Generation. JAPA 2008, 74, 481–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayers, J.; Forsyth, T. Community-based adaptation to climate change. JESSD 2009, 51, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsden, J.; Pickering, P. Securing Australia’s Urban Water Supplies: Opportunities and Impediments; Marsden Jacob Associates Pty Ltd.: Sydney, Australia, November 2006; Available online: http://media.theaustralian.news.com.au/water.pdf (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- Commonwealth of Australia. Adapting to Climate Change in Australia. 2010. Available online: https://catalogue.nla.gov.au/catalog/4832464 (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- Pradhan, A.; Shrestha, K. Rethinking environmental decision-making practice: Environmental and climate change decisions in Australian Governments. IJSD 2012, 3, 11–26. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Climate Change and Energy Efficiency. Adapting to Climate Change in Australia: An Australian Government Position Paper. Department of Climate Change and Energy Efficiency: Canberra, Australia, 2010. Available online: http://www.ag.gov.au/cca (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- New South Wales Parliament Legislative Council. Select Committee on the Response to Major Flooding Across New South Wales; Report No. 1; New South Wales Parliament Legislative Council: Sydney, Australia, August 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Binskin, M.; Bennett, A.; Macintosh, A. Royal Commission into National Natural Disaster Arrangements. 2020. Available online: https://naturaldisaster.royalcommission.gov.au/system/files/202011/Royal%20Commission%20into%20National%20Natural%20Disaster%20Arrangements%20-%20Report%20%20%5Baccessible%5D.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2024).

- DCCEEW (Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action). Adaptation Action Plans: Climate Change; Federal Government Australia: Canberra, Australian, 2022. Available online: https://www.climatechange.vic.gov.au/building-victorias-climate-resilience/our-commitment-to-adapt-to-climate-change/adaptation-action-plans-a-major-step-forward-for-climate-resilience-in-victoria (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- DCCEEW. National Climate Risk Assessment and National Adaptation Plan; Australian Government: Canberra, Australian, 2023. Available online: https://www.dcceew.gov.au/climate-change/policy/adaptation/ncra (accessed on 11 October 2024).

- Victorian Government. Adaptation Action Plans. 2022. Available online: https://www.climatechange.vic.gov.au/building-victorias-climate-resilience/our-commitment-to-adapt-to-climate-change/adaptation-action-plans-a-major-step-forward-for-climate-resilience-in-victoria (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Foerster, A.; Spencer, M. Corporate net zero pledges: A triumph of private climate regulation or more greenwash? Griffith Law Rev. 2023, 32, 110–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemming, P. Greenwash Monster. The Saturday Paper, 29 October 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Moritz, B.; Neo, G. Accelerating Business Action on Climate Change Adaptation: White Paper; World Economic Forum, PwC: Davos, Switzerland, January 2023; Available online: https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/services/sustainability/assets/cop27/accelerating-business-action-on-climate-change-adaptation.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Victoria ‘Failing’ to Offset Damage Caused by Disproportionate Level of Land Clearing. The Guardian. 11 May 2022. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2022/may/11/victoria-failing-to-offset-damage-caused-by-disproportionate-level-of-land-clearing (accessed on 11 May 2022).

- Nalau, J. Adapting to Climate Change: The Priority for Australia. 2023. Available online: https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/adapting-climate-change-priority-australia (accessed on 11 October 2024).

- Biesbroeck, G.; Klostermann, J.; Termeer, C.; Kabat, P. On the nature of barriers to climate change adaptation. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2013, 13, 1119–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, J.; Waters, E.; Pendergast, S.; Puleston, A. Barriers to Adaptation to Sea Level Rise: The Legal, Institutional and Cultural Barriers to Adaptation to Sea Level Rise in Australia; National Climate Change Adaptation Research Facility: Gold Coast, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Thom, B.; Cane, J.; Cox, R.; Farrell, C.; Hayes, P.; Kay, R.; Kearns, A.; Low Choy, D.; McAneney, J.; McDonald, J.; et al. National Climate Change Adaptation Research Plan for Settlements and Infrastructure National Climate Change; Adaptation Research Facility: Gold Coast, Australia, 2010; Available online: https://researchprofiles.canberra.edu.au/en/publications/national-climate-change-adaption-research-plan-settlements-and-in (accessed on 24 July 2024).

- Amundsen, H.; Berglund, F.; Westskog, H. Overcoming barriers to climate change adaptation—A question of multi-level governance? Environ. Plann. C 2010, 28, 276–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paschen, J.; Ison, R. Framing Multi-Level and Multi-Actor Adaptation Responses in the Victorian Context; A Report from the VCCCAR Project; VCCCAR: Melbourne, Australia, September 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenack, K.; Stecker, R. A framework for analyzing climate change adaptations as actions. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Chang. 2012, 17, 243–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Summary for Policymakers. In Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014; pp. 1–32. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/03/ar5_wgII_spm_en-1.pdf (accessed on 11 October 2024).

- Fünfgeld, H.; Fila, D.; Dahlmann, H. Upscaling Climate Change Adaptation in Small and Medium-Sized Municipalities: Current Barriers and Future Potentials. COSUST 2023, 61, 101263. Available online: www.sciencedirect.com (accessed on 11 October 2024). [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Paavola, J.; Dessai, S. Towards a deeper understanding of barriers to national climate change adaptation policy: A systematic review. Clim. Risk Manag. 2022, 35, 100414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonet, G.; Leseur, A. Barriers and drivers to adaptation to climate change—A field study of ten French local authorities. Clim. Chang. 2019, 155, 621–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ison, R.; Straw, E. The Hidden Power of Systems Thinking: Governance in a Climate Emergency; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Howath, C.; Lane, M.; Slevin, A. (Eds.) Effective Communication on Local Adaptation: Considerations for Providers of Climate Change Advice and Support. In Addressing the Climate Crisis; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2021; pp. 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whetton, P.; McInnes, K.; Jones, R.; Hennessy, K.; Suppiah, R.; Page, C.; Bathols, J.; Durack, P. Australian Climate Change Projections for Impact Assessment and Policy Application: A Review; CSIRO (Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation): Canberra, Australia, 2005. Available online: http://vises.org.au/documents/2005-Whetton-et-al-Aust-climate-change-projections.pdf (accessed on 11 July 2024).

- AECOM (Architecture, Engineering, Construction, Operations, and Management). Climate Adaptation Plan; Greater Shepparton Council: Shepparton, VIC, Australia, 14 December 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Strathbogie Shire Council. Climate Change Action Plan: 2022–2027. 2022. Available online: https://share.strathbogie.vic.gov.au/climate-change-action-plan (accessed on 22 July 2024).

- Emery, M.; Purser, R. The Search Conference: A Powerful Method for Planning Organizational Change and Community Action; Wiley: Hoboken, NY, USA, June 1996; ISBN 978-0-787-90192-9. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, R.; Fischer, C.; Rennie, D. Evolving guidelines for publication of qualitative research studies in psychology and related fields. Brit. J. Clin. Psychol. 1999, 38, 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gergis, J. Highway to hell: Climate change and Australia’s future. In Quarterly Essay; Schwartz Publishing: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2024; Volume 95, pp. 1–72. [Google Scholar]

- Sevoyan, A.; Hugo, G.; Feist, H.; Tan, G.; McDougall, K.; Tan, Y.; Spoehr, J. Impact of Climate Change on Disadvantaged Groups: Issues and Interventions; National Climate Change Adaptation Research Facility: Gold Coast, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Stanley, J.; March, A.; Ogloff, J.; Thompson, J. Feeling the Heat: International Perspectives on the Prevention of Wildfire Ignition; Vernon Press: Wilmington, DE, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- DELWP. Local Government Climate Change Adaptation Roles and Responsibilities Under Victorian Legislation: Guidance for Local Government Decision-Makers; DELWP: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2020. Available online: https://www.climatechange.vic.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0030/490476/Local-Government-Roles-and-Responsibilities-for-Adaptation-under-Victorian-Legislation_Guidance-Brief.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2024).

- Nalau, J.; Preston, B.; Maloney, M. Is adaptation a local responsibility? Environ. Sci. Policy 2015, 48, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, M.; Busbridge, R.; Rutledge-Prior, S. The Changing Role of Local Government in Australia: National Survey Findings; ACU Research Centre for Social and Political Change: Melbourne, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, N. The Economics of Climate Change: The Stern Review. 2006. Available online: https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/publication/the-economics-of-climate-change-the-stern-review/ (accessed on 30 October 2024).

- Shi, L.; Moser, S. Transformative climate adaptation in the United States: Trends and Prospects. Science 2021, 372, 6549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Government. National Urban Policy: Consultation Draft. 2024. Available online: https://www.infrastructure.gov.au/department/media/publications/draft-national-urban-policy (accessed on 16 January 2025).

- Nalau, J.; Verral, B. Mapping the evolution and current trends in climate change adaptation science. Clim. Risk Manag. 2021, 32, 100290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Productivity Commission. Inquiry Report: Natural Disaster Funding Arrangements Australian Government; Productivity Commission: Melbourne, Australia, 17 December 2014; 1, p. 74. Available online: https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/disaster-funding/report (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Australian Government. Intergenerational Report 2023: Australia’s Future to 2063; Treasury: Canberra, Australia, 2023. Available online: https://treasury.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023-08/p2023-435150.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Dilling, L.; Prakash, A.; Zommers, Z.; Ahmad, F.; Singh, N.; de Wit, S.; Nalau, J.; Daly, M.; Bowman, K. Is adaptation success a flawed concept? Nat. Clim. Chang. 2019, 9, 570–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Themes | 2012 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|

| Little federal and state government leadership seen as a barrier | √ | √ |

| Poor listening to community seen as a problem | √ | √ |

| Increased local government and local decision-making support needed | √ | √ |

| Under-rating of community ability, empowerment needed | √ | √ |

| Improved integrated governance required | √ | √ |

| A local adaptation leadership group needed | √ | √ |

| Reluctance to face change by some people seen as a problem | √ | √ |

| Feeling of powerlessness, fear of failure and/or dissolution a problem | √ | √ |

| Funding restricted, not available, and/or poor distribution | √ | √ |

| Unclear who should be making adaptation decisions | √ | √ |

| Complexity and competing values present that create difficulties for action | √ | √ |

| Concerns about the natural environment | √ | √ |

| Small positives were achieved | √ | √ |

| Planning needs to be linked to adaptation | √ | √ |

| Want clarity on who is responsible for maintenance of adapted infrastructure | √ | |

| Want more clarity on legal and insurance concerns for community decision-making | √ | |

| Adaptation task was mainly confined to water and fire in discussions | √ | |

| Lack of urgency seen as a problem | √ | |

| Prevention and adaptation prior to extreme event important | √ | |

| Short-termism is a problem | √ | |

| Concern about equity issues and capacity to adapt (people and business) | √ | |

| Wide involvement of groups of people required for adaptation | √ | |

| Wider perspectives and avoidance of preconceived ideas seen as required | √ |

| Phase Responsible Bodies | Prevention | Preparation | Emergency Response | Rehabilitation | On-Going Human and Animal Needs | Result (Possible High of 30) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Federal Govt. | 5 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 17:30 57% |

| State/Territory Govts. | 6 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 20–30 67% |

| Municipal (Local Govt.) | 6 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 21:30 70% |

| Qangos | 5 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 12:30 40% |

| Business | 5 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 11:30 37% |

| Civil society | 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 14:30 47% |

| Total responses from 36 people | 31:36 (86%) | 17:36 (42%) | 14:36 (39%) | 12:36 (33%) | 21:36 (58%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stanley, J.; Spencer, M. Wither Adaptation Action. Climate 2025, 13, 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli13030052

Stanley J, Spencer M. Wither Adaptation Action. Climate. 2025; 13(3):52. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli13030052

Chicago/Turabian StyleStanley, Janet, and Michael Spencer. 2025. "Wither Adaptation Action" Climate 13, no. 3: 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli13030052

APA StyleStanley, J., & Spencer, M. (2025). Wither Adaptation Action. Climate, 13(3), 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli13030052