Abstract

Five species of the genus Equisetum distributed in Bulgaria were studied: four species from the subgenus Equisetum (Equisetum arvense, E. telmateia, E. sylvaticum, and E. palustre) and one from the subgenus Hippochaete (E. ramosissimum). The anatomical, taxonomic, and phylogenetic characteristics of the selected species were established. In species belonging to the subgenus Equisetum, the endodermis was arranged in the form of a continuous ring, while in the representatives of the subgenus Hippochaete, a two-layered endodermis surrounding each vascular bundle was observed. The results from the DNA barcoding supported the taxonomic treatment of the studied species. The chemical and lipid compositions of the plants were also investigated. The Equisetum species had a similar chemical composition and a high content of sterols and phospholipids. In the glyceride oils, palmitic acid predominated, ranging from 69.5% to 78.7%. β-sitosterol was the main component in the sterol fraction, while the tocopherol content was found to be remarkably low in two of the samples (37.6–82.8 mg/kg), with α-tocopherol being predominant. In the phospholipid fraction, the major classes were phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylcholine, phosphatidylinositol, and phosphatidic acids. The chemical composition of the studied species and their high biologically active lipid constituents suggested that they were suitable for application in various directions.

1. Introduction

The genus Equisetum L. is the only extant genus in the family Equisetaceae, class Equisetopsida. According to Tutin et al. [1], in Flora Europaea, the genus comprises 10 species. These species are distributed in several subgenera, of which Equisetum contains eight species and Hippochaete eight species [2,3,4,5].

Subgenus Equisetum is one of the most known categories of horsetails and includes many representatives such as E. arvense L., E. palustre L., E. sylvaticum L., E. telmateia, E. fluviatile, and E. hyemale, while the subgenus Hippochaete is characterized by E. ramoosissimum as the main representative.

The habitat of horsetails covers regions from Greenland and Siberia to the temperate zones of tropical America, the Cape of South Africa, as well as South and South-East Asia [6]. Some representatives of horsetails have been found in Bulgaria: E. hyemale L., E. ramosissimum Desf., E. fluviatile L., E. palustre L., E. sylvaticum L., E. arvense L., and E. telmateia Ehrh. In addition, data about the following species were reported by Jordanov [7]: E. sylvaticum L.; E. maximum Lam. (syn. E. majus, E. telmateia); E. arvense L. (syn. E. arcticum); E. palustre L.; E. limosum L. (syn. E. heleocharis); E. ramosissimum Desf. (syn. E. elongatum); and E. hyemale L.

The following species have been listed in the Flora of Bulgaria [8]: E. arvense L., E. telmateia Ehrh. (syn. E. maximum Lam.), E. limosum L. (syn. E. fluviatile L., E. heleocharis Ehrh.), E. palustre L., E. sylvaticum L., E. ramosissimum Desf., and E. hyemale L. In the Field Guide to the Vascular Plants of Bulgaria [9], the following species were recorded: E. sylvaticum L., E. arvense L., E. telmateia Ehrh. (syn. E. maximum), E. hyemale L., E. ramosissimum Desf., E. palustre L., and E. fluviatile L. (syn. E. limosum). According to Delipavlov and Cheshmedzhiev [10], the recorded species are E. telmateia Ehrh., E. sylvaticum L., E. arvense L., E. ramosissimum Desf., E. fluviatile L., E. palustre L., and E. hyemale L. In the latest edition of the Determinant of Local and Foreign Higher Plants in Bulgaria [11], in addition to the previously mentioned species, E. × moorei Newman is also included.

The plants can reproduce by spores [12]. Subgenus Equisetum is marked by species with numerous lateral branches, and in contrast to Equisetum, Hippochaete plants exhibit no lateral branching [13]. Moreover, compared to other plants, species of the genus Equisetum possess appreciated anatomical and morphological features that allow them to sustain mechanical damage when the amount of water in the cells changes during the growing season [14]. There are many studies on the anatomical features of horsetails, showing their value in solving taxonomic problems [15,16,17].

One of the most important features in the anatomical structure of horsetail stems is the mechanical tissue. Some authors classify it as collenchyma [18,19], while others refer to it as sclerenchyma [20,21]. To avoid confusion in the literature, several researchers have proposed neutral terms such as hypodermis [19], hypodermal steroma [22], and reinforcing tissue [23]. The vascular system of horsetails is represented by a siphonostele [16]. The vascular bundles are closed, collateral, positioned opposite the stem ridges, and arranged around a prominent central cavity.

One of the most recent studies on the anatomical characteristics of horsetails is that of Feoktistov and Goreeva [24]. In their publication, the authors present data on the anatomical structures of nine species and five interspecific hybrids, emphasizing key diagnostic features—specifically, the size and position of mechanical tissue within the stem, as well as the location and number of endodermal layers. Investigating the phylogenetic characteristics of horsetails, Christenhusz et al. [25] measured genome sizes across 28 populations representing 18 species. By comparing their findings with previous studies [26,27,28,29], the authors constructed a phylogenetic framework that reflects the evolutionary dynamics of the genome size within the genus Equisetum. Based on DNA sequences from two chloroplast markers (rbcL and the trnL-F region), Des Marais et al. [30] re-evaluated the taxonomy and morphological evolution of horsetails (Equisetum spp.). Their study provided new insights into the phylogenetic relationships within the genus and contributed to a more refined understanding of species differentiation and evolutionary patterns.

Horsetail species have been integrated into traditional medicine, serving diverse therapeutic purposes [12]. Building upon their widespread distribution and traditional applications, the phytochemical composition of various Equisetum species has garnered increasing scientific interest. Data about the chemical composition of Equisetum species are limited. Among all types of horsetails, E. arvense predominates, due to its medicinal use [31]. Despite the limited data on the overall chemical composition (ash content—22.0% and water content—15.0%) of the species E. arvense declared by Sandhu et al. [32] several studies have highlighted the presence of diverse bioactive compounds across different Equisetum species. E. arvense contains alkaloids, flavonoids, polyphenols, carbohydrates, tannin, proteins and amino acids, phytosterols, saponins, sterols, ascorbic acid, etc. [33]. E. telmateia contains kaempferol and quercetin derivatives as well as phenolic acids [34]. Alkaloids, including nicotine and palustrine, have been detected in several species, particularly E. palustre [35]. Given the abundance of polyphenols and other bioactive compounds across Equisetum species, their physiological relevance has been increasingly explored in cellular and molecular contexts. Experimental evidence indicates that polyphenols may provide indirect protection by activating antioxidant transcription via antioxidant-responsive elements [36]. Furthermore, polyphenols can influence cellular signaling pathways involved in cell proliferation [37] and cell cycle progression [38]. Equisetum species also display antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antiseptic, and anticancer activities [39].

In addition to their antioxidant properties, horsetail species also exhibit a diverse lipid profile. The fatty acid composition of the leaves of four horsetail species was determined by Kokten et al. [40], and the predominant ones identified were linolenic, palmitic, linoleic, hexadecatrienoic, and oleic acids. Minor constituents included palmitoleic, stearic, trienoic, and juniperonic acids, detected at lower concentrations. Other fatty acids—including lauric, myristic, pentadecanoic, hexadecadienoic, margaric, arachidic, gadoleic, and behenic acids—were also detected at concentrations below 1%. Similar trace amounts of these fatty acids have also been reported in other Equisetum species by previous studies [41].

Other biologically active substances, such as sterols, were also examined. According to Takatsuto and Abe [42], in the strobilus of E. arvense, campesterol (33.8%) and sitosterol (56.5%) were identified as the major ones, while 24-methylenecholesterol (2.0%), 22-dihydrobrassicasterol, and stigmasterol were minor components.

Despite the presence of these previous studies, there has been no extensive research on the anatomical, molecular–genetic, and phytochemical study of species from the genus Equisetum from Bulgaria.

For that reason, the aim of this study was to investigate the anatomical, taxonomic, phylogenetic, and phytochemical characteristics of selected Equisetum species. Due to the limited data on the chemical and lipid composition of Equisetum species in Bulgaria—specifically E. arvense, E. telmateia, E. sylvaticum, E. palustre, and E. ramosissimum—this research seeks to enhance understanding of the genus Equisetum. For the first time, the present study provides a comparative anatomical, molecular–genetic, and phytochemical investigation of Equisetum species distributed in Bulgaria. The results obtained may serve as a solid foundation for future research within the genus. This study presents a detailed analysis of the phytochemical constituents and highlights their physiological relevance and potential medicinal applications. Through comparative analysis, the study will identify both shared and unique metabolites among the five species, offering valuable insights into their chemical diversity.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Anatomical Features and Molecular Taxonomic Analyses

The anatomical study of the specified species from the genus Equisetum presented in this article is the first of its kind in the country. It provides data that could be used in future taxonomic research within the genus.

- Subgenus Equisetum

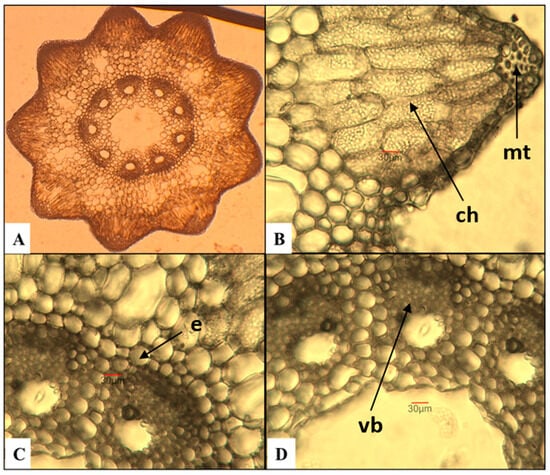

E. arvense—field horsetail (Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Anatomical features of the stem in E. arvense. (A)—Cross section of the stem; (B)—mechanical tissue (mt) and chlorenchyma (ch); (C)—vascular bundles with endodermis (e); (D)—vascular bundles (vb) with part of the central cavity of the stem.

The number of ridges on the stem varies between 9 and 10, and they are well-defined. These results contrast with a study by Feoktistov and Gureeva [24], in which the authors report a minimum of 5 ridges, rarely reaching 18. Having analyzed the same species, Pallag et al. [43] established a range of 6 to 18 ridges. The mechanical tissue is well-developed and is located in the region of the ridges beneath the epidermis. The chlorenchyma, composed of three to five layers of cells, is situated beneath it. The endodermis is uniseriate. The number of vascular bundles corresponds to the number of ridges on the stem. The central cavity has an average measurement of approximately 400 µm, which represents about 1/5 of the stem’s diameter. Although it was examined by Feoktistov and Gureeva [24], the authors conclude that it cannot be used as a diagnostic feature for species of the genus Equisetum.

E. telmateia—great horsetail (Figure 2)

Figure 2.

Anatomical features of the stem in E. telmateia. (A)—Cross section of the stem; (B)—mechanical tissue (mt) and chlorenchyma (ch); (C,D)—vascular bundles (vb) with endodermis (e).

The cross section of the E. telmateia stem reveals a poorly defined multi-ridged structure. The mechanical tissue is poorly developed, consisting of several layers of cells located in the ridged areas. The chlorenchyma tissue is composed of several rows of cells arranged in the form of arc-shaped layers beneath the stem ridges. The endodermis consists of a single layer of cells. The stele comprises vascular bundles surrounded by parenchymatous cells and a central zone characterized by a well-defined cavity.

E. sylvaticum—wood horsetail (Figure 3)

Figure 3.

Anatomical features of the stem in E. sylvaticum. (A)—Cross section of the stem; (B)—mechanical tissue (mt) and chlorenchyma (ch); (C)—vascular bundles with endodermis (e); (D)—vascular bundles (vb) with the central cavity of the stem.

The ridges on the stem are well-defined, trapezoidal when viewed in a cross section, and 10–14 in number with faintly noticeable spines. The obtained results differ from those of Feoktistov and Gureeva [24], according to whom the number of ridges is 8–16 with clearly visible spines arranged in two rows. The mechanical tissue is multiseriate. Following it, the chlorenchyma can be observed in two–three rows of cells, transitioning into parenchymatous tissue, which encircles cavities equal to the number of ridges. Marin et al. [44] report that the chlorenchyma in E. sylvaticum consists of three–four rows of cells in the ridged area, and in one–two layers in the space between them. The endodermis is in the form of a compact ring, surrounding the central part of the stem with the vascular bundles located within it. At the center is the central cavity, which occupies 1/3 of the stem’s diameter.

E. palustre—marsh horsetail (Figure 4)

Figure 4.

Anatomical features of the stem in E. palustre. (A)—Cross section of the stem; (B)—mechanical tissue (mt) and chlorenchyma (ch); (C,D)—vascular bundles (vb) with endodermis (e).

The stem has well-defined ridges, they are 9–10 in number, triangular when viewed in cross section, and rounded at the apex. The chlorenchyma consists of several rows of cells, located beneath the mechanical tissue in the area of the ridges. The endodermis is arranged as a compact ring around the vascular bundles. Similar to the results published by Feoktistov and Gureeva [24], the central cavity is quite narrow, occupying about 1/4 of the stem’s diameter.

- Subgenus Hippochaete

E. ramosissimum—branched horsetail (Figure 5)

Figure 5.

Anatomical features of the stem in E. ramosissimum. (A)—Cross section of the stem; (B)—mechanical tissue (mt) and chlorenchyma (ch); (C,D)—vascular bundles (vb) with endodermis (e).

The cross section of the stem shows 15 broadly triangular ridges. In contrast, Feoktistov and Gureeva [24] report that their number varied between 5 and 21, depending on the stem diameter. The arrangement of the mechanical tissue follows the contour of the ridges; it is multiseriate and does not reach the vascular bundles. The cells of the chlorenchyma tissue are arranged in several rows. The endodermis consists of two layers of cells surrounding the vascular bundles. The central cavity occupies 2/3 of the stem’s diameter.

In addition to the endodermis, the anatomical features presented in Table 1 can also be used to distinguish the two subgenera.

Table 1.

Additional anatomical traits for distinguishing the two subgenera.

For conducting the molecular–taxonomic analyses of the studied species, a single region encoded in the chloroplast genome—tRNAleu—was selected. This molecular marker provides a good basis for assessing molecular–taxonomic links and relationships within the genus and species.

The Bayesian phylogenetic tree reconstructed from the tRNAleu sequences (Figure 6) reveals two major clades with high posterior probability support (>0.95), corresponding to the subgenera Equisetum and Hippochaete. Samples of E. arvense, E. telmateia, E. sylvaticum, and E. palustre cluster within the Equisetum clade alongside conspecific NCBI sequences (e.g., JN968380 E. arvense, MH750085 E. telmateia), while E. ramosissimum groups in the Hippochaete clade with E. hyemale and related taxa (e.g., MH750061, AY226115). This topology confirms the infrageneric delimitation and placement of Bulgarian populations.

Figure 6.

Bayesian phylogenetic tree reconstructed from tRNALeu sequences.

The molecular clustering in Figure 6 aligns with the anatomical distinctions between subgenera. Species in the Equisetum clade (E. arvense, E. telmateia, E. sylvaticum, E. palustre) share a uniseriate endodermis forming a continuous ring around vascular bundles, well-defined ridges (9–14), and multiseriate mechanical tissue beneath the epidermis. In contrast, E. ramosissimum in the Hippochaete clade exhibits a two-layered endodermis per vascular bundle, broader triangular ridges (15), and mechanical tissue not reaching bundles—features consistent across both datasets and supporting subgeneric separation without notable homoplasy. This congruence validates an integrative taxonomy for Equisetum in Bulgaria.

2.2. Chemical Composition of Different Species of Equisetum

The main compounds of the chemical composition of the studied species of Equisetum (protein, carbohydrates, glyceride oil, insoluble fibers, mineral content and moisture) are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Chemical composition of the studied Equisetum species *.

The protein content in the examined samples ranged from 9.3% (E. telmateia) to 15.9% (E. sylvaticum). The studied species had a high carbohydrate content, ranging from 49.8% (E. ramosissimum) to 59.6% (E. sylvaticum). The fiber content in the samples ranged from 20.1% (E. telmateia) to 31.4% (E. arvense). The analyzed aerial stems of the species exhibited low lipid content: 1.9% (E. sylvaticum), 2.7% (E. telmateia and E. ramosissimum), 3.5% (E. palustre), and 3.7% (E. arvense). The studied Equisetum species had a high mineral content—from 12.3% (E. sylvaticum) to 24.0% (E. ramosissimum). The moisture content ranged from 10.3% (E. sylvaticum) to 15.0% (E. arvense), and these values were close to those determined by Sandhu et al. at 15% [32] and Gua et al. at 8.85% [45] for E. arvense.

Similar results for the crude protein content (15.32%) were reported in studies on the chemical composition of E. arvense [45]. The content of carbohydrates in E. arvense was within the content reported by Gua et al. (53.2%) [45]. The glyceride oil content obtained for E. arvense was higher than the 2.21% reported by Goa et al. for the same species prevalent in Korea [45]. However, there were also reports of significantly higher fat content (5.4%, 4.1%, and 4.6%) in the aerial parts of E. fluviatile grown in James Bay Lowland, Canada, during early spring, summer, and autumn [46]. Paine et al. [47] studied Himalayan horsetails species E. diffusum, grown at different altitudes in the Eastern Himalayas, and found lipid contents ranging from 44.58 mg/g dry weight (dw) (4.46%) to 120.83 mg/g dw (12.08%); these values were also higher than the present data. The values for the ash content corresponded with the data on the total ash content of E. arvense (15.3%, 16.8%, 17.2%, 20.42%, and 22.0%) [32,45,46]. Thomas and Prevett [46] studied the chemical composition of the aerial parts of E. fluviatile during early spring, summer, and fall. During the study period, the protein content decreased from 14.0% to 7.3%, and a reduction in the water content from 87.6% to 84.9% was observed. While the lipid content decreased from 5.4% to 4.1% in the first period, it later increased to 4.6%. A similar trend was noted in the ash content: 15.3% (spring), 17.2% (summer), and 16.8% (autumn).

The caloric value of the examined samples ranged from 273.9 kcal/100 g (E. ramosissimum) to 319.1 kcal/100 g (E. sylvaticum). Compared to wheat (334 kcal/100 g), sorghum (343 kcal/100 g), dry beans (341 kcal/100 g), soyabeans (335 kcal/100 g), and quinoa (342 kcal/100 g), the studied species had a lower energy value, though it was similar to that of dried mushrooms (296 kcal/100 g), walnuts (289 kcal/100 g), and hazelnuts (291 kcal/100 g) [48].

2.3. Free Sugar Composition

Plants contain different types of sugars, which are a source of energy and play a role in growth and defense. Significant variations have been observed in the quantity of these components in different organs as well as in different species. The specific types and amounts of sugar vary depending on the plant species, and environmental factors, such as drought or salinity can also affect the sugar content, as plants use sugars to cope with stress [49,50].

The results for the free sugar composition of the studied species are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Content and composition of sugars (g/100 g dw) *.

The total free sugar content in the studied species was relatively high (4.32–17.09 g/100 g dw). In general, the maximum content of total sugars was observed in E. palustre (17.09 g/100 g dw), followed by E. ramosissimum (14.36 g/100 g dw), and minimum sugars were recorded in E. sylvaticum (4.32 g/100 g dw), followed by E. telmateia (6.10 g/100 g dw) and E. arvense (6.14 g/100 g dw). The results indicated the presence of mannose and fructose in all Equisetum species studied. The amount of mannose (2.52–8.20 g/100 g dw) was higher than that of fructose (0.85–3.23 g/100 g dw). The species E. ramosissimum had the highest content of these sugars, respectively, 8.20 g/100 g mannose and 3.23 g/100 g fructose. Rhamnose content was found in the sugars of the species E. sylvaticum (0.95 g/100 g dw) and E. palustre (3.28 g/100 g dw), while galactose was found in the species E. palustre (3.78 g/100 g dw) and E. ramosissimum (2.93 g/100 g dw). Sucrose content was found only in the composition of the sugars of E. telmateia (1.04 g/100 g dw). Studies by Paine et al. [47] on Himalayan horsetails show a soluble sugar content of 145 to 175 mg/g (14.5–17.5%), values close to those obtained in the present study for the species E. palustre and E. ramosissimum. Results that differ from ours were obtained by Gua et al. [45], who found mannose and glucose in the monosaccharide composition of E. arvanse, in amounts of 1616.31 mg/100 g (1.62 g/100 g) and 13,351.88 mg/100 g (13.35 g/100 g), respectively.

2.4. Lipid Composition

Lipids are both products and functional components of living cells. They are primarily composed of triacylglycerols, accompanied by substances such as sterols, tocopherols, and phospholipids. The latter are bioactive compounds that can exert pharmacological effects on humans and animals. Data on the content of biologically active substances in glyceride oils and in the five species of Equisetum are provided in Table 4.

Table 4.

Biologically active substances in the oil and the studied Equisetum species *.

The amount of unsaponifiable matter in the studied Equisetum species oils ranged from 16.1% (E. ramosissimum) to 31.1% (E. sylvaticum). The results were in good agreement with the amount generally reported in crude vegetable oils, according to the Codex Alimentarius (≤9.0–28.0%) [51]. The sterol content in the oils varied between 1.3% (E. telmateia) and 3.0% (E. arvense), while quantities of sterols in the plant were significantly lower—between 0.04 and 0.11%. Tocopherols (vitamin E) were found only in oils isolated from two species of horsetail E. palustre and E. ramosissimum, with the tocopherol content found to be remarkably low, ranging from 37.6 to 82.8 mg/kg (in the plants—2.90 and 1.02 mg/kg, respectively). These values were comparable to those reported for coconut oil (0–50 mg/kg) and palm kernel olein and stearin (0–90 mg/kg and 0–89 mg/kg, respectively) [51]. The dominant tocopherol isomer in the studied oils from two species (E. palustre and E. ramosissimum) was α-tocopherol (100%). The individual tocopherol composition of these oils was similar to the tocopherol profile of the most common vegetable oils—such as sunflower and safflower, where α-tocopherol predominated (89–2468 mg/kg) [51].

The highest phospholipid content was observed in the oils of species E. sylvaticum (11.1%) and E. palustre (15.3%), and 0.21% and 0.54% in the plants, respectively. In comparison, the phospholipid content in the oils of species E. telmateia and E. ramosissimum was 6.3% and 6.7%, and in the plants—0.17% and 0.18%, respectively. The minimum phospholipid content was noted in E. arvense (1.6% in the oil and 0.06% in the plants). The total phospholipid content was higher than that found in vegetable oils, where it typically ranged between 1.0% and 1.5% [51,52]. The studied species had low oil content (1.9–3.7%) but were rich in biologically active compounds as well as sterols and phospholipids. This sparked scientific interest in exploring the fatty acid, sterol, and phospholipid composition of aerial parts of these five Equisetum species.

2.4.1. Fatty Acid Composition

Table 5 shows the fatty acid composition of the glyceride oils from the studied Equisetum species.

Table 5.

Fatty acid composition of glyceride oils from the studied Equisetum species (%) *.

In the oils of the four species (E. arvense, E. telmateia, E. sylvaticum, and E. palustre) palmitic acid predominated, ranging from 69.5% (E. sylvaticum) to 78.7% (E. arvense), followed by myristic acid, which varied from 5.2% (E. telmateia) to 11.5% (E. palustre). These were followed by oleic acid (1.4% in E. arvense to 7.2% in E. sylvaticum), gadoleic acid (2.1% in E. sylvaticum to 3.2% in E. palustre), and lignoceric acid (1.5% in E. arvense to 5.1% in E. sylvaticum). Linoleic acid was present in amounts from 0.8% (E. telmateia) to 4.5% (E. palustre), and erucic acid was from 1.0% (E. arvense and E. palustre) to 3.3% (E. sylvaticum). In the fatty acid profile of species E. ramosissimum, palmitic acid was dominant (70.0%), followed by linolenic (10.6%), gadoleic (9.0%), and oleic acid (4.5%). The oils of the studied Equisetum species also contained a trans isomer of oleic acid—elaidic acid, which was present in amounts of 0.9–1.5% in the oils of three Equisetum species (E. arvense, E. telmateia, E. sylvaticum), while in the oils from the other two types (E. palustre and E. ramosissimum), the trans acid content was very low—0.1%. The lipids of the studied Equisetum species were not rich in essential n-6 and n-3 fatty acids.

The highest content of essential linoleic acid (n-6) was found in the species E. ramosissimum (10.6%), followed by the species E. palustre (4.5%). In the remaining three species, its content varied from 0.8 to 1.6%. Linolenic acid (n-3) was present in minimal amounts (0.1%) in the oils of only two of the studied Equisetum species (E. palustre and E. ramosissimum).

Similar results to ours were obtained by Paine et al. [47] in their study of the fatty acid composition of neutral lipids isolated from Himalayan horsetail species E. diffusum, grown at different altitudes. In neutral lipids, the total saturated fatty acid content was noticeably high (74.36–95.65%), which was primarily due to the predominance of palmitic acid (C16:0)—65.78–84.57%. The palmitic acid content was found to be the highest in the sample from altitude 1980 m (84.57%), which was significantly higher than the samples of higher altitudes (2510 m)—65.78%, while for a sample from the lowest altitude (1390 m), it is 68.07%. In contrast, the linolenic acid (C18:3 n-3) content was much lower—1.39% (1980 m), 13.47% (1390 m), and 18.58% (2510 m).

The data obtained in the current study differed from those of other authors who had studied the fatty acid composition of glyceride oils from different Equisetum species. Authors from Turkey studied the fatty acid composition of various types of horsetails (E. arvense, E. palustre, E. ramosissimum, and E. telmateia) and found that the predominant acid was linolenic acid (41.57–42.57%), followed by palmitic acid (25.93–26.22%) and linoleic acid (8.35–8.92%) [40]. Nokhsorov and Protopopov [53] also found that the main components of total lipids from E. arvense growing in the Yakutia are omega-3 (n-3) and omega-6 (n-6) polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA), such as linoleic (C18:2(n-6)—6.64%) and α-linolenic (C18:3(n-3)—44.53%), the contents of which reached 51.17% of the total sum of FA, and saturated fatty acids (SFA) were mainly represented by palmitic acid (C16:1–29.21%). Dudareva et al. [41], when studying the fatty acid composition of oils from aerial parts of three horsetail species growing in Central and Northern Yakutia (E. arvense, E. variegatum and E. scirpoides), also found that linolenic (25.2–42.3%), linoleic (8.2–23.4%), and palmitic (22.1–26.8%) acids predominated in their composition. Gua et al. [45] studied the fatty acid composition of E. arvense oil and found that α-linolenic (42.83%), linoleic (23.60%), and oleic (7.60%) acids predominated among the unsaturated fatty acids (UFA), and palmitic (19.0%) and stearic (2.47%) acids predominated among the saturated fatty acids. Nokhsorov et al. [54] studied the seasonal changes in the lipid composition of two species of horsetail, E. variegatum and E. scirpoide, growing in the permafrost zone (Northeastern Yakutia, the Pole of Cold of the Northern Hemisphere), with average daily air temperatures in summer of +17.8 °C, in autumn of +0.6 °C, and in winter of −46.7 °C. It was found that the content of linolenic acid in the autumn period decreased compared to the summer season from 39.5% to 25.7%, and in the winter, it increased to 31.5%, respectively, while the amount of saturated palmitic acid increased from 24.7% (summer period) to 30.6% (winter period). The differences in the fatty acid composition of the glyceride oil from different Equisetum species are probably due to several factors: their origin, species, biological and ecological conditions, and the altitude of growing, which may affect the synthesis and accumulation of fatty acids in the plants. According to Kokten et al. [40], the predominance of certain fatty acids is not constant even for the same species, because it is influenced by the specific differences in their varieties, as well as the particular climate and especially the temperature of the habitat.

Figure 7 shows that the amount of saturated fatty acids exceeds 73.0%. The lowest amount of saturated fatty acids was in the oil from the species E. ramosissimum (73.8%), and the highest was in oil isolated from the species E. arvense (91.1%). The oils from the species E. telmateia, E. sylvaticum and E. palustre contained saturated fatty acids in the following amounts: 88.8%, 83.4%, and 86.6% respectively.

Figure 7.

Saturated (SFA), unsaturated (UFA), monounsaturated (MUFA), and polyunsaturated (PUFA) fatty acids in oils from the studies Equisetum species.

The content of monounsaturated fatty acids (7.3–15.5%) was higher than that of polyunsaturated ones (0.8–10.7%). The amount of mono- and polyunsaturated fatty acids was the highest in the oil from the E. ramosissimum species (15.5 and 10.7%) and the lowest in the oil isolated from the E. arvense species (7.3 and 1.6%). In the glyceride oils of the E. sylvaticum and E. telmateia species, the amount of monounsaturated fatty acids (15.4% and 10.4%) was significantly higher than that of polyunsaturated fatty acids (1.2% and 0.8%), while in the E. palustre species, the amounts of monounsaturated ones (8.8%) were about twice as high as the polyunsaturated (4.6%). Our results were consistent with the literature data on the fatty acid composition of the neutral lipids of the horsetails samples collected from three altitude zones of Eastern Himalayan region, where the quantity of saturated fatty acids ranged from 74.36% to 95.65%. The primary saturated fatty acid was palmitic acid (C16:0)—65.78–84.57%. The content of monounsaturated fatty acids was relatively low—between 1.78% and 4.49%. The authors found that the content of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) was the highest in the sample from an altitude of 1390 m (21.52%), which was significantly higher than that from an average altitude of 1980 m (2.57%), while for the sample from the higher altitude (2510 m), it was 21.16%. They demonstrated that variation in the MUFA content based on altitude was not visible, whereas variation in the SFA and PUFA content was quite apparent [47].

2.4.2. Sterol Composition

The main components of sterols were β-sitosterol (from 51.1% in E. arvense to 69.0% in E. sylvaticum) and campesterol (from 24.1% in E. sylvaticum to 37.8% in E. ramosissimum species) (Table 6).

Table 6.

Individual sterol composition of oils from studied Equisetum species (%) *.

The lipids of four of the studied species did not contain cholesterol, except for those of the species E. arvense, which contained a minimal amount—0.2%. According to the literature data, the cholesterol content in the sterol fraction of vegetable oils varied from trace amounts up to 6.7% [51]. The lipids of E. arvense contained a high amount of Δ7-stigmasterol—10.4% compared to lipids from other studied species (from 0.7 to 2.2%). In the studied samples, the stigmasterol content was from 0.3 to 3.8%, which was close to its content in sterols of almond (0.4–4.0%) and hazelnut (0–2%) oil. The Δ5-avenasterol content (0.2–1.8%) in the studied Equisetum species was comparable to its content in sterols of high oleic palm oil (0–1.9%) [51]. The remaining types of sterols ranged from 0.1% to 1.5%. The sterol composition of the Equisetum species oils analyzed in this study was consistent with the data reported by Takatsuto and Abe [42] on the sterol profile of lipids isolated from strobilus of E. arvense, where β-sitosterol was the predominant component (56.5%), followed by campesterol (33.8%).

2.4.3. Phospholipid Composition of Lipids

The individual composition of the phospholipids in the studied Equisetum species was also investigated. In the phospholipid fraction of oils from different samples, major classes of phospholipids were identified (Table 7), particularly phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylcholine, phosphatidylinositol, and phosphatidic acids.

Table 7.

Individual composition of phospholipids fraction of oils from the studied Equisetum species (%) *.

The highest content of phosphatidylethanolamine was found in the lipids of the species E. arvense (35.9%) and E. palustre (24.3%), and a lower content was observed in the lipids from E. telmateia and E. sylvaticum (11.7 and 11.6%). The lipids of the species E. telmateia, E. sylvaticum, E. palustre, and E. ramosissimum showed a higher content of phosphatidic acids (26.6, 46.0, 42.4, and 30.7%, respectively), while in species E. arvense it was 13.2%. Phosphatidylcholine was present in higher amounts in the lipids of E. sylvaticum (21.8%) and of E. palustre (19.6%), and in other species its amount varied from 12.4% (E. arvense) to 15.8% (E. ramosissimum). A higher content of phosphatidylinositol was also noted in lipids from E. telmateia (23.1%), and a lower content was observed in the lipids from E. palustre (5.3%). Monophosphatidylglycerol in the lipids of all the studied samples ranged between 2.6 and 9.4%. The highest levels of lysophosphatidylethanolamine were observed in the lipids from E. arvense (17.2%), E. telmateia (15.3%), and E. ramosissimum (12.3%), while in species E. sylvaticum and E. palustre, it was 5.5% and 3.6%, respectively. The data indicated that the phospholipids in the different species had a similar qualitative but different quantitative composition. Similar to our results were those of Nokhsorov et al. [54], who studied the seasonal variability of phospholipid composition in the aerial parts of two species of horsetail E. variegatum and E. scirpoides, growing in the Northeastern Yakutia. They found that phosphatidic acids (PA) predominated in the phospholipid fraction isolated from E. variegatum during the summer, autumn, and winter periods. In the phospholipids of E. scirpoides during the summer and autumn periods, phosphatidylcholine predominated, while during the winter period, phosphatidic acids were highest. Both plants accumulated PA in response to the decrease in temperature and light in the autumn–winter period. Other phospholipid classes demonstrated different seasonal trends in the studied samples. Phosphatidylcholine was accumulated in E. variegatum in the winter period, whereas, in E. scirpoides, the content of this phospholipid increased in autumn but sharply decreased in the winter. The content of phosphatidylethanolamine decreased in both plants in winter as compared to the autumn values, but the summer values of this phospholipid were different for two species—in E. variegatum, very low values, while in E. scirpoides, relatively high values. The differences in phospholipid composition between Equisetum species most likely can be explained by their different habitats, different soil and climatic conditions, genetic variability, physiological needs, etc. [54].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

For the present study, use was made of plant material of five Equisetum species distributed in Bulgaria (Table 8, Figure 8). The materials were collected and processed during the growing seasons of 2023 from the Rhodope Mountains (Western) region.

Table 8.

List of taxons studied and locality of their collection.

Figure 8.

Authors’ photo examples of the examined species. (A)—E. arvense, (B)—E. telmateia, (C)—E. sylvaticum, (D)—E. palustre, (E)—E. ramosissimum.

3.2. Anatomical and Molecular Taxonomic Analyses

For the anatomical analysis of the stems of the studied Equisetum species, the classical method was applied [55]. The anatomical analyses were conducted on cross sections from the middle part of the stem in the region of the internodes. For the anatomical studies, the plant parts were preliminarily fixed in 70% ethanol. The following anatomical characteristics were examined, some of which, according to Minarchenko et al. [56], can be used as diagnostic features for distinguishing between species: number of stem ridges; location of the mechanical tissue; location and number of chlorenchyma layers; number of endodermal layers; and dimensions of the central cavity.

The molecular–genetic analysis was performed on fresh plant material. For the molecular analyses, total plant DNA extraction was performed using a kit DNeasy Plant Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Hamburg, Germany), following the procedure specified by the manufacturer. The concentration and quality of the isolated DNAs were determined fluorometrically (Qubit 4 Fluorometer, Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) and by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. To perform the phylogenetic analysis, the target DNA sequence was amplified using PCR. The tRNAleu amplification was performed using forward primer trnL-c (5′-CGAAATCGGTAGACGCTACG-3′; Code B49317) and reverse primer trnL-f (5′-ATTTGAACTGGTGACACGAG-3′; Code A50272). Conventional PCR was performed in 20 µL reactions containing 1 µL template DNA, 0.2 µM of each primer, 1 U Taq DNA polymerase, 0.2 mM of each dNTP, and standard buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 9.0, 50 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2) using a Biosystems 2720 Thermal Cycler. The cycling conditions were 94 °C for 4 min; 30 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 56 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 40 s; and a final extension at 72 °C for 7 min. The resulting products were separated on a 1% agarose gel solution. Staining of the gels was carried out using ethidium bromide. All gels were visualized and recorded using a BIO-VISION+3026.WL gel documentation system. The size of the amplified fragments was determined relative to a standard DNA marker —Fermentas GeneRuler SM#0331. For the extraction of PCR products from the gel, a kit from Qiagen, Germany (QIAquick PCR & Gel Cleanup) was used, following the protocol recommended by the manufacturer. After purification, the products were subjected to Sanger sequencing in both directions to ensure the accuracy of the obtained sequences. The quality of the DNA sequences was verified using the Chromas v.2.6.6 software (Technelysium Pty Ltd., Brisbane, Australia). In parallel, questionable nucleotides were reviewed and corrected based on the available chromatograms. In the next stage of the analysis, the resulting consensus sequences were subjected to a BLAST analysis (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool, version 2.15.0), and the sequences most closely related to them were organized into a local database of tRNAleu sequences. Subsequently, the respective sets of sequences underwent multiple comparative analysis using the Megalign package from the Lasergene 10 suite. The Tamura–Nei algorithm, integrated into the program, was used for statistical processing. The absence of nucleotides in certain sequences was integrated into the analysis using the global gap removal model. The results obtained were visualized in the form of a cladogram.

Light microscope images of the examined anatomical features of the stems were taken with a Magnum T microscope(Medline Scientific c/o Calibre Scientific, Rotherham, UK), equipped with a Si5000 photo documentation system, at magnifications of ×100 to ×400, at the Department of Botany and Biological Education, Faculty of Biology, University of Plovdiv “Paisii Hilendarski”. The cross sections were prepared using razor blades.

3.3. Chemical Composition

The aerial parts of the plants were used for the phytochemical investigations. All of the analyses were carried out with air-dried material.

The lipids were isolated from 50 g of samples with n-hexane in a Soxhlet extractor [57]. The Kjeldahl method was used for the determination of the total protein content in accordance with the AOAC [58]. The total carbohydrate content was calculated: 100 − (weight in grams [protein + lipids + moisture + ash] in 100 g of dry seeds) [59]. The content of insoluble fibers, ash, and moisture were determined according to the AOAC [58]. The energy value (EV, kcal/100 g) was calculated using the following formula [59]:

EV, kcal/100 g (kJ/100 g) = % proteins × 4.0 (17) + % carbohydrates × 4.0 (17) + % lipids × 9.0 (38).

3.4. Soluble Sugars

The composition of the water-soluble carbohydrates was determined through high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). The sample preparation was described by Georgiev et al. [60]. In brief, 5 g of the ground material was extracted with 100 mL of 60 % ethanol in a shaking water bath at 83 °C for 20 min. The solution was cooled and filtered through Whatman N4 paper, and additional filtration was carried out through a Sep-Pak C18 cartridge (Waters, Milford, MA, USA) and a 0.22 μm membrane filter (Sterivex™-GS Millipore®). The determination of the individual sugars was performed on an Agilent® LC 1220 instrument (USA) with a Zorbax Carbohydrate column (150 mm × 4.6 mm, pore size: 70 Å, particle size: 5.0 µm, Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA), a Zorbax Reliance Cartridge guard-column (Agilent), and a refractive index detector (RID 1260). The mobile phase (flow rate of 1.0 mL/min) was acetonitrile/water (AcN/H2O) (80/20). The temperature of the column and detector was 30 °C. All sugars were identified by comparing the retention times of the analytes with analytical grade standards (glucose, fructose, galactose, rhamnose, xylose, arabinose, sucrose, and maltose (Sigma-Aldrich (Steinheim, Germany)).

3.5. Lipid Composition

3.5.1. Fatty Acids

The composition of the fatty acids was determined by gas chromatography (GC) [61]. Fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs) were obtained by trans-esterification of the glyceride oil with methanol in the presence of sulfuric acid [62]. The determination was carried out on an HP 5890 gas chromatograph (Hewlett–Packard GesmbH, Vienna, Austria) equipped with a capillary column Supelco (Supelco, Bellefonte, PA, USA) of 30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.2 µm (film thickness) and a flame ionization detector (FID). The conditions were as follows: the starting column temperature was 70 °C (for 1 min), increasing at 6 °C/min to 190 °C (3 min), followed by an increase at 10 °C/min to 240 °C. The temperature of the injector and detector was 250 °C. Identification was performed by comparison of the retention times of the unknown peaks with the retention time of a standard mixture of FAMEs (Supelco, 37 comp. FAME mix., Bellefonte, PA, USA). The software used was Data Apex Clarity TM 2.4.1.93/2005 (DataApex, Prague, Czech Republic).

3.5.2. Sterols

The isolated glyceride oils (3–5 g) from the samples were subjected to saponification with 2 N KOH, and the unsaponifiable matter was extracted with hexane [63]. The total sterols were isolated from the unsaponifiable matter through thin-layer chromatography, and their content was determined spectrophotometrically at 597 nm [64]. The sterol composition was determined on an HP 5890 gas chromatograph (Hewlett–Packard GesmbH, Vienna, Austria) with a capillary column DB 5 (25 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 µm (film thickness), Agilent Technologies, J&W Scientific products Proudly, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and FID. The operating conditions were as follows: temperature starting from 90 °C (3 min) up to 290 °C at a rate of 15 °C/min, and then, the temperature increased up to 310 °C at a rate of 4 °C/min (hold for 10 min). The detector temperature was 320 °C, and the injector temperature was set at 300 °C. The carrier gas was hydrogen. The individual sterol composition was determined by a comparison of the retention times with a standard mixture of sterols [65]. The software used was Data Apex Clarity TM 2.4.1.93/2005 (DataApex, Prague, Czech Republic).

3.5.3. Tocopherols

High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was used for the determination of the tocopherol composition. The equipment was a Merck–Hitachi (Burladingen, Germany) with a florescence detector F-1050 (Merck-Hitachi, Burladingen, Germany) and a D-2500 Merck–Hitachi chromato-integrator (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). The experimental conditions were fluorescent detection at 295 nm excitement and 330 nm emission, and the column used was Nucleosil Si 50-5 column (250 mm × 4 mm, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). The mobile phase was hexane: dioxane, 96:4 (v/v), at a flow rate of 1 mL/min [66]. The individual tocopherols were identified by comparing the retention times with those of the standard reference materials.

3.5.4. Phospholipids

The phospholipid classes were isolated by two-dimensional thin-layer chromatography [67]. The spots of the individual phospholipids were scraped and mineralized with perchloric and sulfuric acid (1:1, v/v), and their content was determined spectrophotometrically at 700 nm [68].

3.6. Statistical Analysis

The results are expressed as the mean values of three parallel determinations ± standard deviations (n = 3). Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Duncan’s test for multiple comparisons (p < 0.05).

4. Conclusions

The anatomical analysis of stems identified the endodermis as the most important characteristic distinguishing the two subgenera. In the species belonging to the subgenus Equisetum (E. arvense, E. palustre, E. sylvaticum, and E. telmateia), the endodermis is arranged in the form of a continuous ring. In representatives of the subgenus Hippochaete (E. ramosissimum), one can observe a two-layered endodermis surrounding each vascular bundle. Other important anatomical features that can be differentiated between the two subgenera include the number and shape of the stem ridges in cross section and the location of the mechanical tissue. When comparing the obtained results with those of major previous studies by Pallag et al. [42] and Feoktistov and Gureeva [24], differences were observed regarding the number of stem ridges. As for the diameter of the central cavity, our findings support the conclusion of Feoktistov and Gureeva [24] that this feature cannot be used as a diagnostic feature for distinguishing species within the genus Equisetum.

The results from the applied DNA barcoding support the taxonomic treatment of the studied Equisetum species. The analyzed samples cluster together with several other representatives of the genus Equisetum and show the highest degree of homology with sequences of the same species annotated in the NCBI bio-database.

The studied species of Equisetum (E. arvense, E. telmateia, E. sylvaticum, E. palustre, E. ramosissimum) had a similar chemical composition—proteins (9.3–15.9%), carbohydrates (49.8–59.6%), fiber (20.1–31.4%), oils (1.9–3.7%), and mineral substances (12.3–24.0%). Equisetum species were high in protein and carbohydrate content, with low glyceride oil, which determined their relatively high nutritional and caloric value (273.9–319.1 kcal/100 g). The studied species had a high content of sterols and phospholipids, and the palmitic acid predominated, ranging from 69.5% (E. sylvaticum) to 78.7% (E. arvense). On the other hand, low amounts of tocopherols were identified only in E. palustre and E. ramosissimum with α-tocopherol being predominant. The chemical composition of the studied Equisetum species and their biologically active lipid constituents may suggest their suitability for application in the chemical and pharmaceutical industry, in phytotherapy and cosmetics, as well as in organic agriculture as a soil improver.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.S. and R.M.; methodology, K.T., G.A., Z.P., O.T., M.A.-R., and S.N.; validation, Z.P., G.A., and E.A.; formal analysis, K.T., G.A., Z.P., O.T., M.A.-R., E.A., S.N., D.G., T.M., and H.P.; investigation, G.A., R.M., and P.S.; resources, K.T., P.S., and R.M.; data curation, Z.P., G.A., O.T., E.A., and K.T.; writing—original draft preparation, G.A., O.T., Z.P., P.S., and K.T.; writing—review and editing, M.A.-R., R.M., S.N., E.A., D.G., T.M., and H.P.; visualization, P.S., R.M., and K.T.; supervision, G.A., P.S., and R.M.; project administration, P.S.; funding acquisition, P.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was financed by the European Union-NextGenerationEU, through the National Recovery and Resilience Plan of the Republic of Bulgaria, project № BG-RRP-2.004-0001-C01.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| dw | Dry weight |

| FA | Fatty acids |

| SFA | Saturated fatty acids |

| UFA | Unsaturated fatty acids |

| MUFA | Monounsaturated fatty acids |

| PUFA | Polyunsaturated fatty acids |

| PA | Phosphatidic acids |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

| AOAC | Association of Official Analytical Chemists |

| HPLC | High performance liquid chromatography |

| GC | Gas chromatography |

| FID | Flame ionization detector |

| FAMEs | Fatty acid methyl esters |

| POWO | Plants of the World Online |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations |

References

- Tutin, T.G.; Burges, N.A.; Chater, A.O.; Edmondson, J.R.; Heywood, V.H.; Moore, D.M.; Valentine, D.H.; Walters, S.M.; Webb, D.A. Flora Europaea, 2nd ed.; Psilotaceae to Platanaceae; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1993; Volume 1, pp. 7–9. [Google Scholar]

- Hauke, R.L. A Taxonomic Monograph of Equisetum, Subgenus Equisetum. Nova Hedwig. 1978, 30, 385–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauke, R. Horsetails (Equisetum) in North America. Fiddlehead Forum 1983, 10, 39–42. [Google Scholar]

- Hauke, R. Equisetaceae (Horsetail Family). In Flora of North America North of Mexico; Flora of North America Editorial Committee, Ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 76–84. [Google Scholar]

- Christenhusz, M.J.M.; Chase, M.W. Trends and concepts in fern classification. Ann. Bot. 2014, 113, 571–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christenhusz, M.J.M.; Bangiolo, L.; Chase, M.W.; Fay, M.F.; Husby, C.; Witkus, M.; Viruel, J. Phylogenetics, classification and typification of extant horsetails (Equisetum, Equisetaceae). Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2019, 189, 311–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordanov, D. (Ed.) Flora of the Republic of Bulgaria; Bulgarian Academy of Sciences Press: Sofia, Bulgaria, 1963; Volume 1, p. 508. [Google Scholar]

- Stoyanov, N.; Popov, B.; Kitanov, B. Flora of Bulgaria (Parts 1–2); Nauka i Izkustvo: Sofia, Bulgaria, 1967; p. 1367. [Google Scholar]

- Andreev, N.; Anchev, M.; Kozhuharov, S.; Markova, M.; Peev, D.; Petrova, A. Field Guide to the Vascular Plants in Bulgaria; Nauka i Izkustvo: Sofia, Bulgaria, 1992; p. 787. [Google Scholar]

- Delipavlov, D.; Cheshmedzhiev, I. (Eds.) Key to the Plants of Bulgaria; Academic Press Agricultural University: Plovdiv, Bulgaria, 2003. (In Bulgarian) [Google Scholar]

- Stoyanov, K.; Raycheva, T.; Cheshmedzhiev, I. Determinant of Local and Foreign Higher Plants in Bulgaria, Interactive Expanded and Supplemented Edition; Academic Publishing House of the Agricultural University—Plovdiv: Plovdiv, Bulgaria, 2022; Available online: https://botanica.gallery/plantkeybg/app.htm (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- Nosrati Gazafroudi, K.; Mailänder, L.K.; Daniels, R.; Kammerer, D.R.; Stintzing, F.C. From Stem to Spectrum: Phytochemical Characterization of Five Equisetum Species and Evaluation of Their Antioxidant Potential. Molecules 2024, 29, 2821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- POWO. Plants of the World Online. Facilitated by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Available online: https://powo.science.kew.org (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Zajaczkowska, U.; Kucharski, S.; Nowak, Z.; Grabowska, K. Morphometric and Mechanical Characteristics of Equisetum hyemale Stem Enhance Its Vibration. Planta 2017, 245, 835–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, C.N. Two Hybrids in Equisetum New to the British Flora. Watsonia 1973, 9, 229–237. [Google Scholar]

- Filin, V.R. Division Equisetophyta. In Life of Plants; Prosvyaschenie: Moscow, Russia, 1978; Volume 4, pp. 131–136. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Brune, T.; Thiv, M.; Haas, K. Equisetum (Equisetaceae) Species or Hybrids? ISSR Fingerprinting Profiles Help Improve Diagnoses Based on Morphology and Anatomy. Plant Syst. Evol. 2008, 274, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauke, R.L. A Taxonomic Monograph of the Genus Equisetum, Subgenus Hippochaete. Beih. Zur Nova Hedwig. 1963, 8, 123. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, J.T. Observations on the Hypodermis of Equisetum. S. Afr. J. Sci. 1976, 72, 303–305. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, M.A. Hydathodes in the Genus Equisetum. Bot. Gaz. 1937, 98, 598–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogura, Y. Comparative Anatomy of Vegetative Organs of the Pteridophytes, 2nd ed.; Encyclopedia of Plant Anatomy; Borntraeger: Berlin, Germany, 1972; p. 502. [Google Scholar]

- Gierlinger, N.; Sapei, L.; Paris, O. Insights into the Chemical Composition of Equisetum hyemale by High Resolution Raman Imaging. Planta 2008, 227, 969–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spatz, H.; Köhler, L.; Speck, T. Biomechanics and Functional Anatomy of Hollow-Stemmed Sphenopsids. I. Equisetum giganteum (Equisetaceae). Am. J. Bot. 1998, 85, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feoktistov, D.S.; Gureeva, I.I. Anatomical Features of Cross-Sections of the Genus Equisetum Members. Ukr. J. Ecol. 2018, 8, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christenhusz, M.J.M.; Chase, M.W.; Fay, M.F.; Hidalgo, O.; Leitch, I.J.; Pellicer, J.; Viruel, J. Biogeography and Genome Size Evolution of the Oldest Extant Vascular Plant Genus, Equisetum (Equisetaceae). Ann. Bot. 2021, 127, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennert, W.; Lubienski, M.; Körner, S.; Steinberg, M. Triploidy in Equisetum Subgenus Hippochaete (Equisetaceae, Pteridophyta). Ann. Bot. 2005, 95, 807–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bainard, J.; Henry, T.; Bainard, L.; Newmaster, S. DNA Content Variation in Monilophytes and Lycophytes: Large Genomes That Are Not Endopolyploid. Chromosome Res. 2011, 19, 763–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, C.; Alverson, W.S.; Follansbee, A.; Waller, D.M. New Reports of Nuclear DNA Content for 407 Vascular Plant Taxa from the United States. Ann. Bot. 2012, 110, 1623–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, J.; Hidalgo, O.; Pellicer, J.; Liu, H.; Marquardt, J.; Robert, Y.; Christenhusz, M.; Zhang, S.; Gibby, M.; Leitch, I.J.; et al. Genome Evolution of Ferns: Evidence for Relative Stasis of Genome Size Across the Fern Phylogeny. New Phytol. 2016, 210, 1072–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Des Marais, D.L.; Smith, A.R.; Britton, D.M.; Pryer, K.M. Phylogenetic Relationships and Evolution of Extant Horsetails, Equisetum, Based on Chloroplast DNA Sequence Data (rbcL and trnL-F). Int. J. Plant Sci. 2003, 164, 737–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Committee on Herbal Medicinal Products. European Union Herbal Monograph on Equisetum arvense L.; European Medicines Agency: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sandhu, N.S.; Kaur, S.; Chopra, D. Pharmacognostic evaluation of Equisetum arvense Linn. Int. J. PharmTech Res. 2010, 2, 1460–1464. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Snafi, A.E. The pharmacology of Equisetum arvense—A review. IOSR J. Pharm. 2017, 7, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sureshkumar, J.; Jenipher, C.; Sriramavaratharajan, V.; Gurav, S.S.; Gandhi, G.R.; Ravichandran, K.; Ayyanar, M. Genus Equisetum L: Taxonomy, toxicology, phytochemistry and pharmacology. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2023, 314, 116630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, L.; Ernst, L.; Lubienski, M.; Papke, U.; Schiebel, H.-M.; Jerz, G.; Beuerle, T. Structural and quantitative analysis of Equisetum alkaloids. Phytochemistry 2015, 116, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masella, R.; Di Benedetto, R.; Vari, R.; Filesi, C.; Giovannini, C. Novel mechanisms of natural antioxidant compounds in biological systems: Involvement of glutathione and glutathione-related enzymes. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2005, 16, 577–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corona, G.; Deiana, M.; Incani, A.; Vauzour, D.; Dessi, M.A.; Spencer, J.P. Inhibition of p38/CREB phosphorylation and COX-2 expression by olive oil polyphenols underlies their anti-proliferative effects. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007, 362, 606–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Heideman, L.; Chung, C.S.; Pelling, J.C.; Koehler, K.J.; Birt, D.F. Cell-cycle arrest at G2/M and growth inhibition by apigenin in human colon carcinoma cell lines. Mol. Carcinog. 2000, 28, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takuli, P.; Khulbe, K.; Kumar, P.; Pant, C. Chemical composition of essential oil of Equisetum diffusum: A noble source of phytol. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 2020, 11, 5572–5578. [Google Scholar]

- Kokten, K.; Ozel, H.B.; Yazici, H.; Iskil, R.; Kaya, Z. Fatty acid compositions of different Equisetum species. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2020, 56, 1117–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudareva, L.V.; Nokhsorov, V.V.; Rudikovskaya, E.G.; Petrov, K.A. Fatty-acid profiles of aerial parts of three horsetail species growing in Central and Northern Yakutia. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2015, 51, 220–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takatsuto, S.; Abe, H. Sterol Composition of the Strobilus of Equisetum arvense L. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 1992, 56, 834–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pallag, A.; Paşca, B.; Jurca, T.; Suciu, R.; Nemeth, S.; Vicaş, L. Comparative Histo-anatomical researches on the vegetative organs and assessment of antioxidant capacity of two species from Equisetum Genus. Farmacia 2016, 64, 372–377. [Google Scholar]

- Marin, D.; Boz, I.; Mardari, C.; Cioancă, O.; Robu, S.; Tănase, C.; Toma, C.; Hăncianu, M. Contributions to the Histo-Anatomy of Three Equisetum Species. Analele Stiintifice Ale Univ. "Al. I. Cuza" Din Iasi 2019, 65, 5–12. Available online: http://www.bio.uaic.ro/publicatii/anale_vegetala/anale_veg_index.html (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Gua, J.; Jin, Y.S.; Han, W.; Shim, T.H.; Sa, J.H.; Wang, M.H. Studies for component analysis, antioxidative activity and α-glucosidase inhibitory activity from Equisetum arvense. J. Korean Soc. Appl. Biol. Chem. 2006, 49, 77–81. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, V.G.; Prevett, J.P. The role of horsetails (Equisetaceae) in the nutrition of northern-breeding geese. Oecologia 1982, 53, 359–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paine, A.K.; Mitra, S.; Bera, R.; Paul, I.; Sarkar, M.P. Metabolic insights into high-altitude adaptation of Himalayan ‘horsetails’ [Equisetum diffusum D. Don] with special reference to the fatty acid dynamicity. South Afr. J. Bot. 2024, 171, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food Balance Sheets, a Handbook, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, 2001, Annex I, Food COMPOSITION Tables. 2001. Available online: https://www.fao.org/4/x9892e/X9892e05.htm (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Jeandet, P.; Formela-Luboińska, M.; Labudda, M.; Morkunas, I. The Role of Sugars in Plant Responses to Stress and Their Regulatory Function during Development. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhaka, V.; Shahdab, H. Determination of total soluble sugar content in some selected species of family Euphorbiaceae of Sikar District of Rajasthan, India. Plant Arch. 2020, 20, 7226–7228. Available online: https://www.plantarchives.org/20-2/7226-7228%20(6529).pdf (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- CODEX STAN 210-1999; Codex Standard for Named Vegetable Oils. Revisions 2001, 2003, 2009; Amendments 2005, 2011; Codex Alimentarius Commission. FAO/WHO: Rome, Italy, 1999.

- Popov, A.; Ilinov, P. Chemistry of Lipids; Science and Art: Sofia, Bulgaria, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Nokhsorov, V.V.; Protopopov, F.F. Composition of fatty acids, essential oils and morphological characteristics of some medial plants growing in permafrost ecosystems. Acta Biol. Sib. 2025, 11, 91–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nokhsorov, V.V.; Dudareva, L.V.; Senik, S.V.; Chirikova, N.K.; Petrov, K.A. Influence of extremely low temperatures of the pole of cold on the lipid and fatty-acid composition of aerial parts of the horsetail family (Equisetaceae). Plants 2021, 10, 996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metcalfe, C.R.; Chalk, L. Anatomy of the Dicotyledons: Leaves, Stem and Wood in Relation to Taxonomy with Notes on Economic Uses; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1950; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Minarchenko, V.; Tymchenko, I.; Pidchenko, V.; Dvirna, T.; Makhynia, L.; Karpiuk, U.; Kovalska, N. Diagnostic Features of Raw Materials of Related Equisetum Species of Ukrainian Flora. J. Res. Pharm. 2022, 26, 1780–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 659:2009; Oilseeds—Determination of Oil Content (Reference Method). ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- AOAC—Association of Official Analytical Chemists. Official Methods of Analysis, 20th ed.; AOAC: Arlington, VA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Food Energy—Methods of Analysis and Conversion Factors; Report of a Technical Workshop, FAO Food and Nutrition Paper 77; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Georgiev, Y.; Ognyanov, M.; Yanakieva, I.; Kussovski, V.; Kratchanova, M. Isolation, characterization and modification of citrus pectins. J. Biosci. Biotechnol. 2012, 1, 223–233. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 12966-1:2014; Animal and Vegetable Fats and Oils. Gas Chromatography of Fatty Acid Methyl Esters—Part 1: Guidelines on Modern Gas Chromatography of Fatty Acid Methyl Esters. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- ISO 12966-2:2017; Animal and Vegetable Fat and Oils. Gas Chromatography of Fatty Acid Methyl Esters—Part 2: Preparation of Methyl Esters of Fatty Acids. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- ISO 18609:2000; Animal and Vegetable Fats and Oils. Determination of Unsaponifiable Matter. Method Using Hexane Extraction. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000.

- Ivanov, S.; Bitcheva, P.; Konova, B. Méthode de détermination chromatographyque et colorimétrique des phytosterols dans les huiles végétales et les concentres steroliques. Rev. Fr. Corps Gras 1972, 19, 177–180. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 12228-1:2014; Animal and Vegetable Fats and Oils. Determination of Individual and Total Sterols Contents. Gas Chromatographic Method. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- ISO 9936:2016; Animal and Vegetable Fats and Oils. Determination of Tocopherol and Tocotrienol Contents by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- Schneiter, R.; Daum, G. Analysis of yeast lipids. In Methods in Molecular Biology, 2nd ed.; Xiao, W., Ed.; Humana Press Inc.: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2006; pp. 75–84. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 10540-1:2014; Animal and Vegetable Fats and Oils. Determination of Phosphorus Content. Part 1: Colorimetric Method. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.