Abstract

Vegetation in residential areas plays a crucial role in biodiverse and sustainable cities as it enhances biological diversity, environmental quality, and the human well-being of city residents. However, the distribution of vegetation among these areas is often unequal, leading to disparities in access to its benefits. To promote a more biodiverse and environmentally just city, we investigated how woody plants (trees, shrubs and vines) vary with socioeconomic level in residential streetscapes of Santiago de Chile. Across the city, we sampled woody plants in 120 plots (11 m radius) located in residential streetscapes of three socioeconomic levels: low, medium, and high. A total of 557 woody plants were identified and measured. Of these, only 9.7% corresponded to native species, whereas 90.3% were introduced species. Wealthier residential areas had higher species richness and abundance of woody plants, as well as plants with greater structural size (revealed by height and crown area). In addition, we found that the composition of woody plants differed among socioeconomic levels: Liquidambar styraciflua, Platanus x hispanica, and Pittosporum tobira were more abundant in high socioeconomic areas; Prunus cerasifera, Citrus limon, and Ailanthus altissima were more abundant in medium socioeconomic areas; Robinia pseudoacacia, Acer negundo, and Schinus areira were more abundant in low socioeconomic areas. Our research highlights that woody plant diversity, abundance, structure, and composition vary with socioeconomic level in residential streetscapes. Key insights for reducing these inequalities and achieve a more environmentally just city include: (a) governance and equity-based investment; (b) prioritizing local native species; (c) promoting the use of non-tree woody plants; and (d) empowering communities through capacity building and stewardship.

1. Introduction

The relevance of vegetation in urban areas is increasing due to its contribution to human well-being, the environment and biodiversity [1]. Urban vegetation has been identified as an important component of cities that encourages recreational activities, leisure, and sports, helping to improve the physical and mental health of citizens [2,3]. Urban vegetation also contributes to reducing environmental pollution, noise, flooding, and heat islands in highly urbanized cities [4,5,6]. Furthermore, biodiversity in cities is closely related to the presence and diversity of vegetation, which also provides food, rest and refuge for various invertebrate and vertebrate animals [7,8,9].

Vegetation in residential areas is a crucial source of biodiversity in cities, playing a significant role in connecting people with nature [10,11]. Although residential vegetation can produce some disservices such as building damage or even death due to tree or branch fall, the ecosystem services associated with their presence are more valuable and often prevail [2,12]. Therefore, sustainable urban development promotes greener cities, not only considering plant abundance but also plant diversity. The diversity of plants provides urban green spaces with significant resilience to face various threats, such as pests or meteorological events, as some species can resist while others cannot [13,14,15].

In addition to the richness and abundance of trees as “quality” indicators of green spaces, the structural condition of vegetation is an important complementary variable [16,17]. Structural complexity of vegetation in natural ecosystems is associated with resilience and high biodiversity [18]. This complexity is given by several factors. Some of these factors include growth habits, the age of individuals, the vertical and horizontal coverage of plants, and management. In urban ecosystems, vertical cover is also important in cities [19]. For instance, shrubs contribute to noise reduction [20]. Nevertheless, urban vegetation literature commonly focuses on urban trees [21,22,23].

Thus, plants provide a multitude of benefits to urban ecosystems. While climate is typically a primary factor influencing which species thrive in a given natural ecosystem [24], urban environments often feature the same or related ornamental plant species across vastly different global climates [13,25,26]. The introduction of non-native species implies that many are not locally adapted to the climates where they reside, making their survival contingent upon specific human management interventions. For example, sensitive species that require supplemental irrigation to survive after establishment depend heavily on consistent access to water, especially during dry seasons. This management significantly increases the care costs in arid, semi-arid, and Mediterranean climates [27,28].

Therefore, socioeconomic realities can have a close relationship with urban vegetation. In arid regions and those with dry seasons (such as Mediterranean climates), the financial capacity to provide irrigation is not uniform across a city. The income of specific neighborhoods can directly limit the viability and growth of certain sensitive species within urban ecosystems [29,30]. Similarly, the overall abundance of trees and green cover within a neighborhood requires ongoing resources for maintenance (e.g., watering, pruning, pest control). This commonly results in wealthier neighborhoods exhibiting greater plant cover and a higher abundance of trees in residential areas, squares, and parks [31,32].

Despite the importance of vegetation in cities, urban plants and their benefits are not always equally distributed [33,34]. Several countries worldwide have experienced the phenomenon known as the “luxury effect”, where vegetation cover, abundance, and/or tree diversity are greater in zones with higher socioeconomic status [10,35,36]. This effect has been observed in cities of countries with different economic development, but it is more frequent in arid or semi-arid zones and older neighborhoods [36]. However, there are many cases where the luxury effect is not that evident, even in countries with arid climates or dry seasons.

In this research, we aimed to determine whether woody plant diversity, abundance, structure and composition vary with socioeconomic status in residential streetscapes of Santiago de Chile, a city located in a Mediterranean climate. We focused on woody vegetation present in the residential streetscape, which includes trees, shrubs and vines in public spaces (streets, verges, and medians) and in private front yards visible from the street, representing the vegetation that shapes the residential streetscape. Plants in these areas reflect both municipal and resident management, and thus could be closely linked to resident socioeconomic status [37,38]. In particular, we: (1) tested whether the richness and abundance of total, native and introduced woody plants in residential streetscapes vary with neighborhoods’ socioeconomic level; (2) evaluated differences in height and crown area of woody plants, as a structural measure of vegetation, among zones with different socioeconomic levels; and (3) investigated woody plant composition and the species that differed among streetscapes in different socioeconomic areas. Overall, this research provides novel insights into understanding socioeconomic disparities in woody vegetation among residential streetscapes and seeks strategies to promote a biodiverse and environmentally just city.

2. Results

2.1. Richness and Abundance

We evaluated woody plants in 120 plots located in residential streetscapes of varying socioeconomic levels in Santiago, Chile. Only two of these plots did not contain any woody plants. A total of 108 species were recorded (including morphospecies, Appendix A). We found 45 families and 78 genera (Appendix A), among these, 94 (87%) species were introduced and only 14 (13%) were native (Table 1). The most represented families in terms of number of species were Rosaceae and Fabaceae (12 species each). At the genus level, Prunus (6 species) was the most diverse, with all species introduced in Chile (Appendix A). Five introduced species were the most abundant plants, comprising 31.1% of the total: Robinia pseudoacacia L. exhibited a relative abundance of 9.0%, Ligustrum lucidum W. T. Aiton had a relative abundance of 6.8%, Liquidambar styraciflua L. sp. Pl. had a relative abundance of 6.1%, Acer negundo had a relative abundance of 4.8%, and Platanus x hispanica had a relative abundance of 4.3%. The total species richness recorded in residential streetscapes of low, medium, and high socioeconomic levels were 48, 67, and 60 species, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of the number of woody plants and their origin recorded in residential streetscapes of different socioeconomic levels in Santiago de Chile.

A total of 557 woody plants were identified and measured. Of the total, 503 individuals (90.3%) corresponded to introduced species and 54 individuals (9.7%) to native species. The mean woody plants per plot were highest in streetscapes of high socioeconomic level with (mean ± EE) 5.58 (±0.50) woody plants per plot, followed by medium and low socioeconomic levels with 4.56 (±0.44) and 3.9 (±0.39) woody plants per plot, respectively (Table 1).

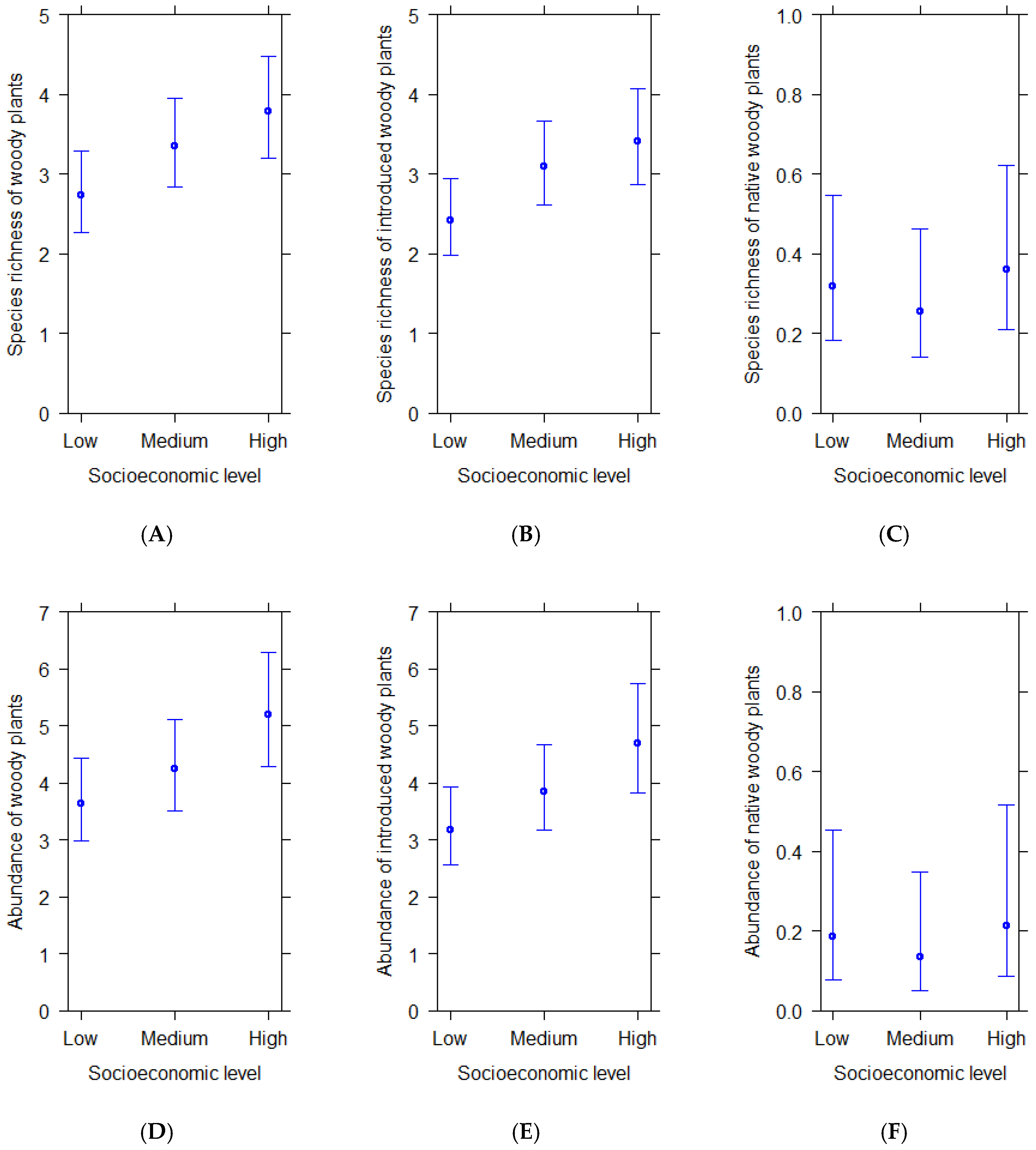

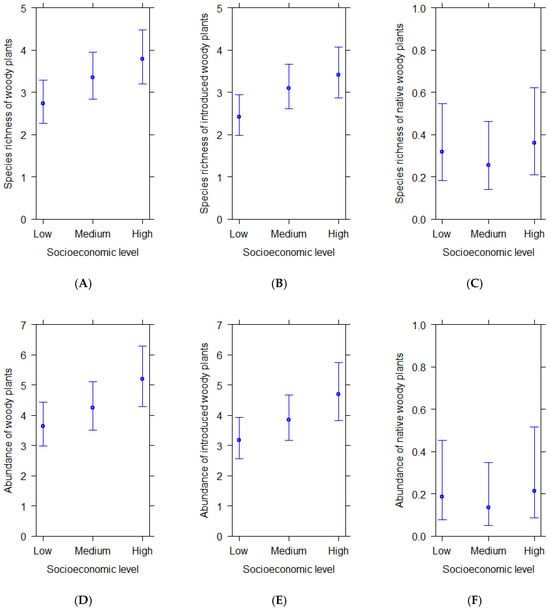

Species richness and abundance of total (Figure 1A,D) and introduced woody plants per plot (Figure 1B,E) increased from zones of low to high socioeconomic level. Significant statistical differences were found between plots from high and low socioeconomic levels in total species richness and total abundance, i.e., streetscapes located in wealthier residential zones had significantly richer and more abundant woody plants than streetscapes located in poorer residential zones (Table 2). Introduced woody plants were also significantly more abundant and richer in streetscapes located in wealthier residential areas than in poor residential areas (Table 2). Native woody plants exhibited similar species richness and abundance in plots across socioeconomic streetscapes (Figure 1C,F; Table 2).

Figure 1.

(A–F) Predicted average species richness and abundance of woody plants per plot in residential areas of different socioeconomic levels according to statistical models. Bars show 95% confidence intervals.

Table 2.

Results from generalized linear models (log-link) predicting species richness and generalized linear mixed models (log-link) predicting the abundance of total, native and introduced woody plants per plot according to socioeconomic level in residential areas of Santiago de Chile. Significance levels: *** p < 0.001; ** p < 0.01; * p < 0.05.

2.2. Structure

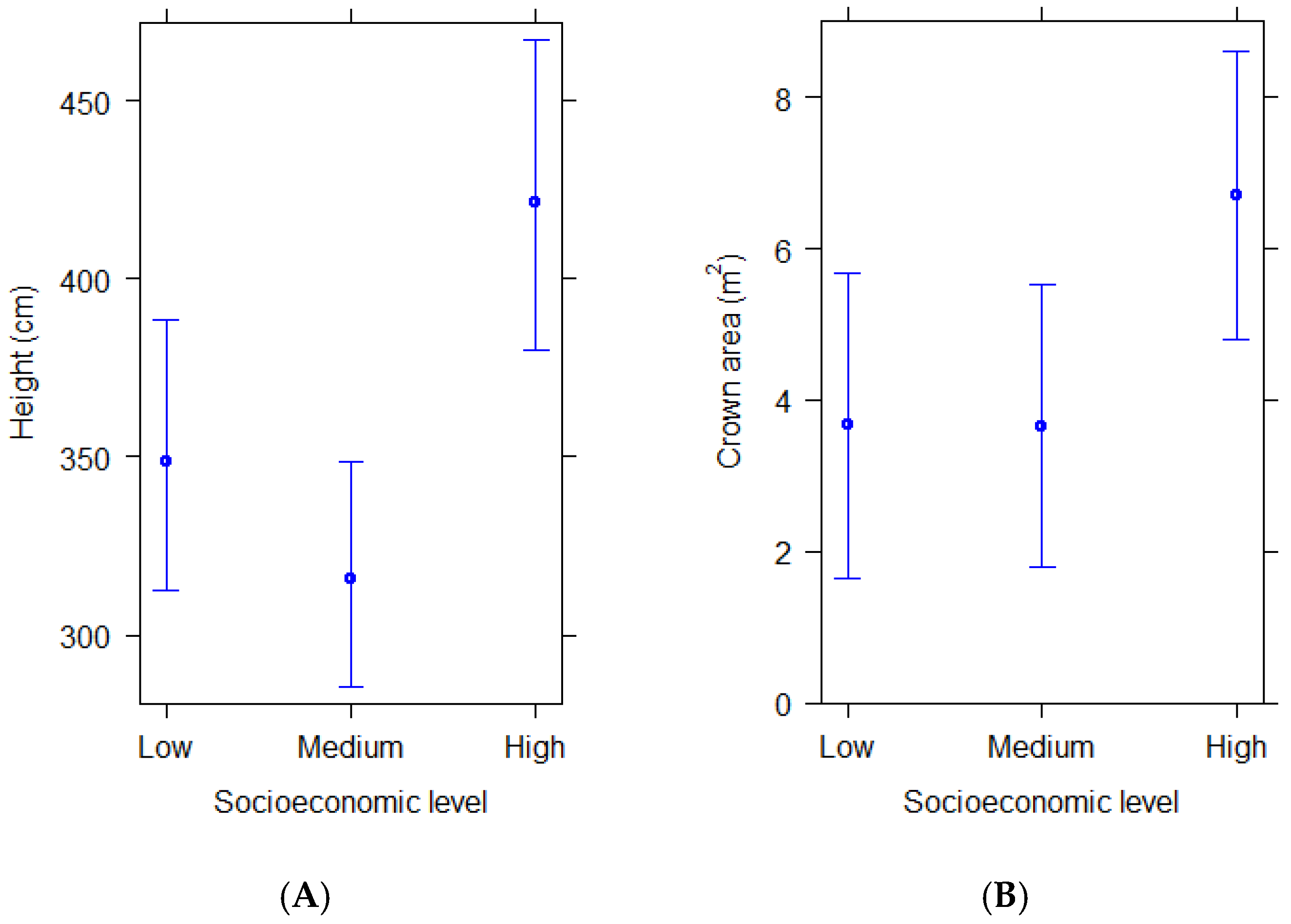

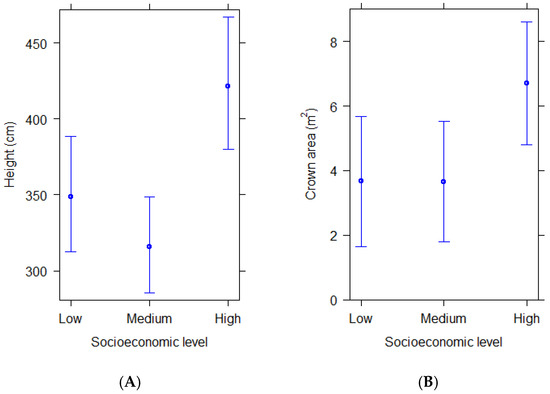

Structural differences of woody plants also varied with socioeconomics, as revealed by their height and crown horizontal area. Woody plants in residential streetscapes of high socioeconomic level were taller and had larger crown areas than those in residential streetscapes of medium and low socioeconomic level (Figure 2A,B). These differences were significant when comparing both height and crown area between high and medium, and high and low socioeconomic levels (Table 3).

Figure 2.

(A,B) Predicted average height and crown area of woody plants in residential areas of different socioeconomic levels according to statistical models. Bars show 95% confidence intervals.

Table 3.

Results from linear mixed effects models predicting crown area and height of woody plants according to socioeconomic level in residential areas of Santiago de Chile. Significance levels: *** p < 0.001; * p < 0.05.

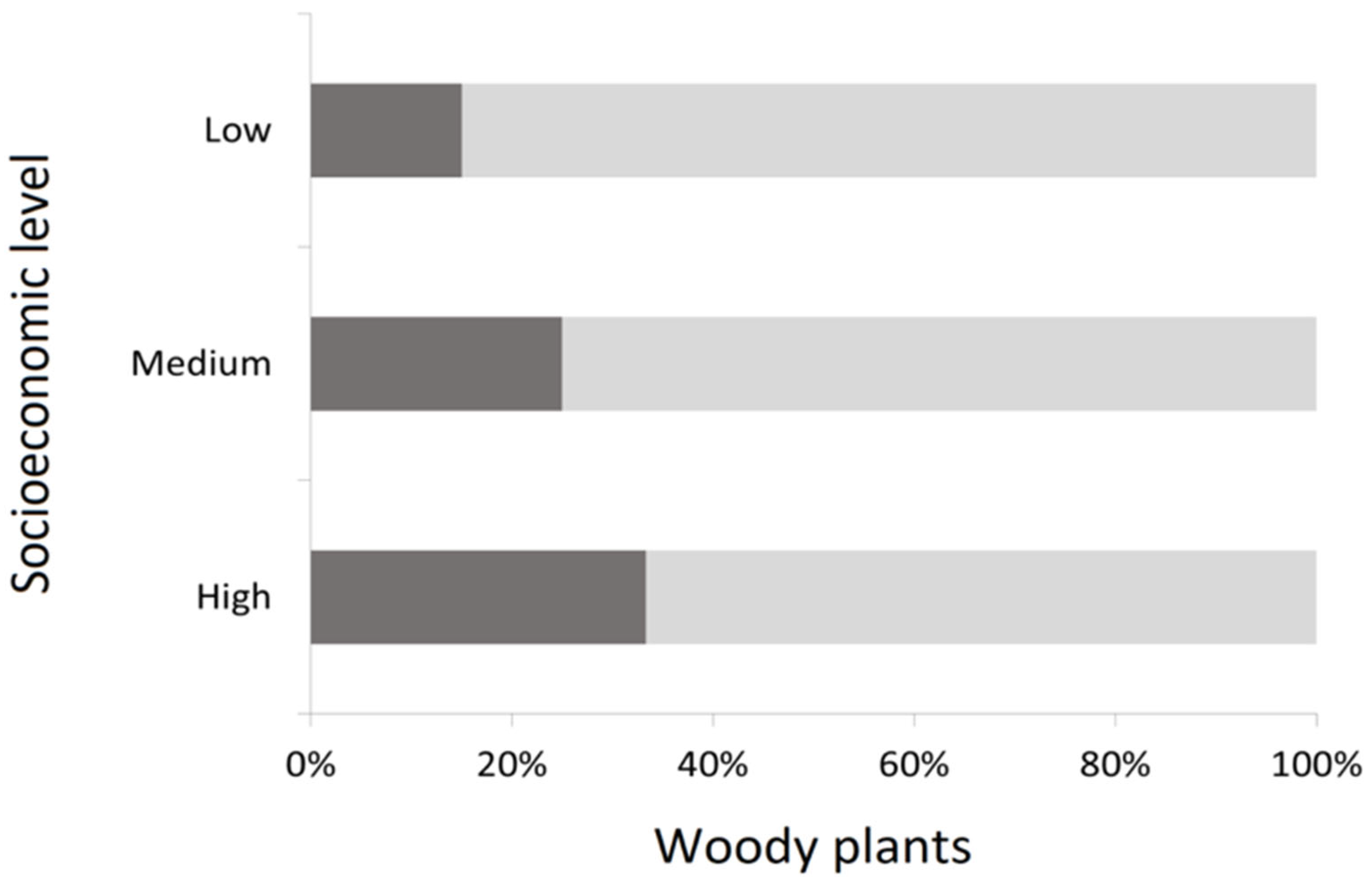

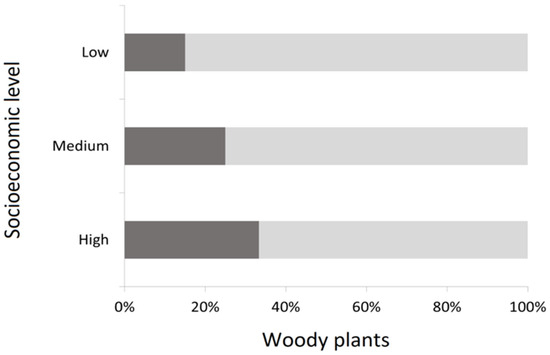

Total species of woody plants are mainly represented by trees (74.9%), with only 25.1% of species represented by other kinds of woody plants such as shrubs Pyracantha coccinea M. Roem, Ligustrum sinense Lour., and Pittosporum tobira (Thunb.) W. Aiton, which are frequently used as hedges. Also, low socioeconomic level zones tend to have a lower proportion of non-tree woody plants than wealthier zones (χ2 = 18.51; p < 0.05) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Representativeness of trees (light gray) and non-tree (dark gray) woody plants in streetscapes according to socioeconomic level.

2.3. Composition

When comparing common woody species (those present in more than 5% of total plots), permutational multivariate analysis of variance indicated a statistically significant difference in woody plant species composition among residential streetscapes of different socioeconomic levels (p = 0.015). SIMPER analysis evidenced different woody species explaining differences among socioeconomic groups (Table 4). Robinia pseudoacacia and L. styraciflua significantly contributed to the dissimilarity between high versus low socioeconomic areas. Robinia pseudoacacia contributed 15% to the total dissimilarity and was more abundant in residential streetscapes of low socioeconomic level than in high socioeconomic level (p-value = 0.02). L. styraciflua explained 12% of the dissimilarity and was more abundant in residential streetscapes of high socioeconomic level than in the low socioeconomic level (p = 0.04). The native species Schinus areira L. was more frequent in residential streetscapes of low socioeconomic level than in the high socioeconomic level, although its contribution to dissimilarities was only close to significant (p = 0.07, Table 4).

Table 4.

Results from SIMPER analysis showing species contributions to dissimilarities between socioeconomic groups. Significance levels: *** p < 0.001; * p < 0.05; p < 0.1.

Dissimilarity between high versus medium socioeconomic areas was highly influenced by L. styraciflua, which was more abundant in residential streetscapes of high socioeconomic level and emerged as the most significant species, accounting for 13% of the dissimilarity (p = 0.001). Platanus x hispanica Mill. Ex Münchh. and P. tobira also contributed to dissimilarities, being more abundant in residential streetscapes of high socioeconomic level (p = 0.03 and p = 0.04, respectively).

When comparing plots in residential streetscapes of medium and low socioeconomic level, Prunus cerasifera Ehrh., Citrus limon (Chritm.) Swingle, and Ailanthus altissima (Mill.) Swingle were more abundant in residential streetscapes of medium socioeconomic level than in the low socioeconomic level, significantly contributing to dissimilarity (p-value = 0.03, p-value = 0.007, and p-value = 0.03). Acer negundo L. was more abundant in low socioeconomic areas, although it was close to significant (p = 0.05).

3. Discussion

Vegetation in residential areas is central to urban biodiversity, ecosystem services, and residents’ daily contact with nature. In Santiago de Chile, a highly segregated city located in a Mediterranean climate, residential streetscapes exhibited socioeconomic disparities in woody species richness, abundance, structure, and composition. These differences have implications for the well-being of citizens, adding another barrier for poorer people to access services, specifically ecosystem services and the benefits derived from urban vegetation.

3.1. Richness and Abundance of Woody Plants

Woody plant richness and abundance in residential streetscapes increased with the neighborhood socioeconomic level, making evident the occurrence of the “luxury effect” on residential woody plants. This result differed from a previous investigation focused on trees in public parks and squares in Santiago city, where the authors found similar tree abundance and species richness among socioeconomic level zones [39]. In the case of Santiago city, the care of woody plants in residential streetscapes correspond mainly to neighbors as well as 34 different municipalities, whose incomes are highly correlated with their neighbors’ wealth [40], which explains the differences observed in our study. In contrast, vegetation management in parks and squares is commonly managed by municipalities as well as centralized institutions, such as Parquemet [39,41], which has a budget established by the central government that can contribute to reducing disparities in vegetation cover. In addition, the inclusion of non-tree woody plants (shrubs and vines) along with trees in our work could also explain the difference with this previous study, which only evaluated trees in parks and squares [39]. In fact, a recent study found a lack of socioeconomic effects on urban flora sampled in sidewalks, parks, and vacant lots of Santiago, although shrub richness exhibited a luxury effect [42]. Given that different variables can influence the richness and abundance of urban woody plants (e.g., [42]), future studies should explore multiple factors to better understand plant patterns.

The lower species richness and abundance found in streetscapes of low socioeconomic level compared to wealthier zones demonstrate that inequities are far more than purchasing power; it is also a disadvantage in the possibility of enjoying urban plants and their ecosystem services, including a more biodiverse and healthier environment that improves mental and physical health [2,33]. Housing in low socioeconomic zones is characterized by its small size, and then, scarce space to have gardens [43,44]. In some cases, urban planning is so deficient that neither of the streets has land available to plant, and thus, residential streetscapes are dominated by grey structures, including impervious surfaces and buildings. On the other hand, high socioeconomic areas have a larger proportion of green spaces, and residential streetscapes often feature green cover with a greater variety of plants, even though urbanization intensity is high [45].

3.2. Structure of Woody Plants

Residential streetscapes in high socioeconomic zones had woody plants with greater height and crown horizontal area than in medium and low socioeconomic zones. This finding can be explained by the varying quality of vegetation management within Santiago city. A recent study showed a substantial inequity in the quality of vegetation pruning across different socioeconomic levels [38]. These authors determined that trees located in residential zones of high socioeconomic level exhibit better pruning quality than trees located in medium and low socioeconomic zones. In this sense, although the objective of corrective pruning—the dominant technique in the management of woody vegetation in the city of Santiago [38]—is to maintain or improve its structure and health, the indiscriminate cutting of branches can heavily reduce tree size through crown reduction [46].

Alternatively, the greater height and crown horizontal area of woody plants found in residential streetscapes of high socioeconomic level could be due to older individuals, since woody vegetation size is a good proxy for woody vegetation age [47]. While the oldest plants can be found in older neighborhoods regardless of socioeconomic status [48], we found that in Santiago, higher socioeconomic areas often invest greater resources to save and prolong tree life. For example, during road infrastructure remodeling in high socioeconomic zones in Santiago city, trees are commonly rescued, maintained and replanted once construction works end (e.g., [49]). Meanwhile, in areas of lower socioeconomic status, vegetation is typically removed and replaced with younger plants after the completion of road infrastructure remodeling or real estate projects.

Although trees are highly represented in streetscapes, shrubs and other non-woody plants play an important role in cities, contributing to heterogeneity and increasing biodiversity and resilience [50]. Nevertheless, in our study, we found that the proportion of non-tree woody plants decreased as the socioeconomic level decreased, adding a new inequity variable to consider in the city. Next, the ecosystem services given by non-tree woody plants, such as noise reduction [20], were more limited in lower socioeconomic conditions. Ecosystem services such as carbon sequestration, thermal regulation or scenic beauty in urban spaces are frequently associated with the presence of trees [51,52,53]. Nevertheless, shrubs and other woody plants, as climbers, can also accomplish these roles, making the mix of different vertical strata complementary and beneficial for urban ecosystems [17,54,55].

3.3. Composition of Woody Plants

Our study revealed the predominance of introduced woody plants in residential streetscapes, accounting for 87% of the recorded species, while native species comprise only 13%. These values coincide with the results of [56], who found 88.3% and 11.7% for introduced and native woody species, respectively, on the streets of Santiago city. The reasons for the dominance of introduced woody plant species in residential areas may be diverse. On the one hand, they could be reflecting the European influence on the use of ornamental flora species in urban spaces, which has been present in Chile since the nineteenth century [57]. It could also be due to urban foresters, landscape architects, and residents commonly selecting introduced plants with ornamental value or fast growth for afforestation [41]. On the other hand, the low use of native woody species in residential areas could be due to the lack of knowledge about their use as ornamental plants and the small number of native species commercially cultivated, as well as the misconception that all native Chilean plants grow slowly [56].

Although introduced woody species represent almost 90% of the total plant species, we found differences in woody plant communities in residential streetscapes of different socioeconomic status. In the case of high vs. low socioeconomic levels, the dissimilarity is explained by the high abundance of R. pseudoacacia in the low level and of L. styraciflua in the high level. Although both species are widely used as ornamental species [58], this difference could be explained by the different budgets available to municipalities for street vegetation management [59]. For example, the commercial value of a L. styraciflua seedling is 10 to 15 times higher than a R. pseudoacacia seedling. We also found a greater abundance of the native species S. areira in residential streetscapes of low socioeconomic level. The greater abundance of this species could be explained by its low commercial value (similar to that of R. pseudoacacia) and high drought resistance [58], an attractive condition for municipalities with limited budgets, as it involves less irrigation costs for its maintenance.

L. styraciflua, Platanus x hispanica, and Pittosporum tobira are more abundant in residential streetscapes of high than medium socioeconomic zones. In the case of L. styraciflua, its high commercial value limits its use in residential areas of low socioeconomic level. However, P. x hispanica and P. tobira could be related to their growth characteristics. Although P. x hispanica has been widely used for ornamental purposes in the city of Santiago since the beginning of the last century [60], its extensive growth in height and leafy canopy makes it common on sidewalks of large avenues or wide streets [58]. This implies a need for space for its growth, a limited resource in residential areas of lower socioeconomic levels due to the planning of narrow streets to accommodate higher density of buildings and housing construction [61]. Similarly, the bushy growth of P. tobira would also require space to grow, a condition that restricts its use only to wide streetscapes common in higher-income areas.

P. cerasifera, C. limon, and A. altissima are more abundant in residential streetscapes of middle than low socioeconomic levels. In Chile, in the late 1970s and early 1980s, a process of suburban expansion of the city intensified, linked to the residential aspirations of the middle class [62]. Thus, residential areas were influenced by North American design with single-story houses and some innovative features for the time, such as the presence of front yards [63] that added aesthetic value to the streetscape. Thus, householders began to plant fruit trees in their front gardens, including P. cerasifera and C. limon, contributing to the self-sufficiency of these fruits in cities [64]. Additionally, the compact growth dimensions of P. cerasifera make it a common species within the vegetation of streets and passages within villas or condominiums [58].

Acer negundo was more abundant in low-income areas. The low commercial value of this species (25 to 30 times less than L. styraciflua and a third of the value of R. pseudoacacia and S. areira) has probably encouraged its use in street vegetation by low-income municipalities and by real estate developers of social housing. Acer negundo is the fourth most abundant species found in our survey, which could explain the rapid expansion of the introduced maple bug (Boisea trivittata) in the city of Santiago since its first record in 2020 [65], helped by the massive use of A. negundo in low socioeconomic level municipalities that dominate the urban landscape.

The massive use of the same introduced species in cities with very different climatic and edaphic conditions is a phenomenon that causes biotic homogenization worldwide. Therefore, to conserve biodiversity, we need to promote the use of a variety of native plant species [25,66]. The importance of plant origins in urban ecosystems is currently increasing due to climate change. The requirements of plants to survive in a city must adjust to the new conditions that the climate imposes [67]. In this context, native species better address this challenge [68], especially in our Mediterranean-climate region. Nevertheless, introduced woody plants from temperate climates dominate the current urban forest, and native species represent a very low percentage of residential woody plants in Santiago. In fact, compared to [32], who found 14.0% of native trees at the city-level, our study showed that the percentage of native woody plants was even lower (9.7%) in residential streetscapes. In parks and squares, the proportion of native trees reached 30% [39], still a very low value that raises concerns given the irrigation cost of introduced plants from temperate climates. Given the expected reductions in rainfall in our region due to climate change [69], the challenge is to develop strategies that enhance vegetation resilience to new and future climate conditions. This means that in the future, residential plants must be capable of resisting less or no irrigation. Several Mediterranean native woody plants exhibit this adaptation and possess ornamental potential [70], underscoring the need to incorporate them more extensively into the urban forest.

3.4. Recommendations

Our analysis revealed significant disparities in the diversity, abundance, structure, and composition of woody plants across residential streetscapes of varying socioeconomic status in Santiago de Chile. These inequalities contribute to an uneven distribution of the ecological and social benefits provided by urban greenery. To address this environmental injustice and improve the resilience and performance of the city’s urban forest, we propose the following integrated recommendations:

- 1.

- Governance and equity-based investment: A centralized, city-wide authority for public vegetation management should be established. This body would be responsible for allocating resources to correct budgetary inequalities between municipalities, ensuring that low-income neighborhoods receive equitable investment. It would also develop and enforce standardized guidelines for woody plant planting, maintenance, and conservation as a matter of state policy. A key function would be to institutionalize a proactive, city-wide tree protection and compensation policy. This policy must prioritize preventing damage to significant trees—such as heritage, large-canopy, or ecologically and socially valuable specimens—during planning and construction. For trees that cannot be preserved in situ, their rescue and replanting should be analyzed, considering prioritizing greening projects in historically underserved areas.

- 2.

- Prioritize local native species: To future-proof Santiago’s urban forest against escalating climatic pressures like drought, heat waves, and novel pests, a strategic shift toward native and drought-adapted woody species is imperative. A local native species pool should be promoted for both public and private plantings. These species are evolutionarily suited to local conditions, typically require less irrigation water, and support native biodiversity, thereby enhancing the long-term sustainability and adaptive capacity of the urban ecosystem.

- 3.

- Promote the use of non-tree woody plants: Urban planners and managers must recognize that shrubs and vines are critical components of the green infrastructure. These woody plant forms provide essential ecosystem services—such as thermal regulation, habitat, and aesthetic value—while enhancing structural heterogeneity, biodiversity, and overall ecological resilience. Actively incorporating them into planting schemes, particularly in low-income areas where canopy cover is low and there are scarce shrubs and vines, can rapidly augment green cover and its associated benefits.

- 4.

- Empower communities through capacity building and stewardship: In low-income neighborhoods, resident engagement is a powerful tool for expanding and sustaining green cover on private and eligible communal land. We recommend establishing community-based training and certification programs, overseen by local municipalities. These programs would equip interested residents with the skills to select appropriate species for the site, plant, and care for woody vegetation in their own private spaces (e.g., front yards, interior gardens) and in authorized communal areas. By focusing on private stewardship and providing official recognition, these initiatives can foster a culture of care, legally amplify greening efforts beyond public rights-of-way, and build social resilience alongside ecological benefits.

Together, these recommendations should be considered as part of a strategy to transform Santiago’s streetscapes into more equitable, biodiverse, and climate-resilient urban forests.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Area

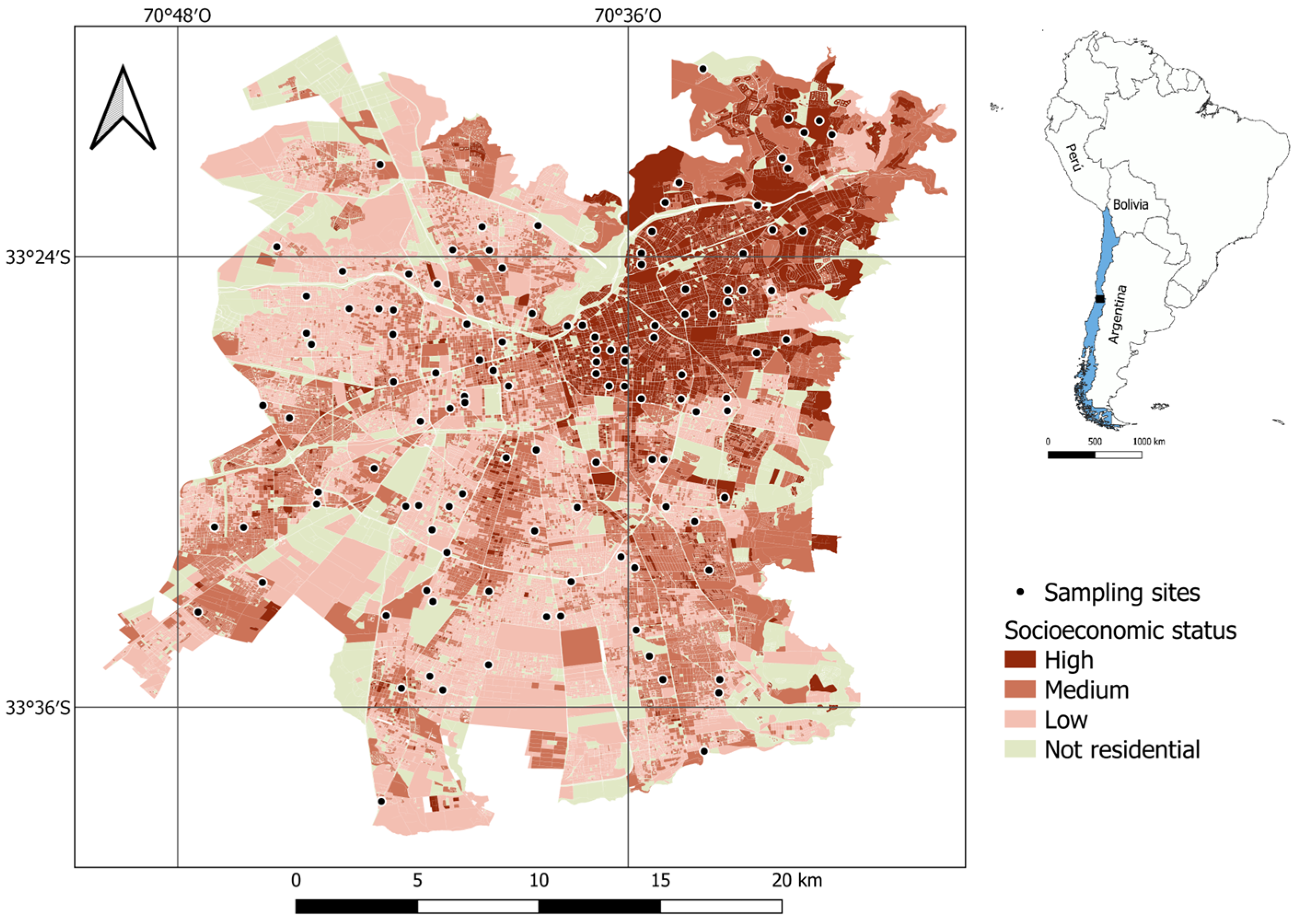

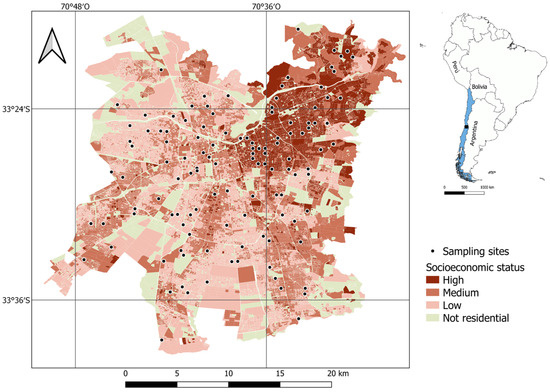

The research was conducted in Santiago, the capital of Chile, located at coordinates 33°26′ S and 70°39′ W, in central Chile (Figure 4). This city spans more than 650 km2 and is home to over 7 million residents (40% of the national population), making it Chile’s most populous city [71]. Santiago has a Mediterranean climate characterized by hot, dry summers (December to March) and cool, rainy winters (June to August) [72]. The warmest average temperature in the period 1991–2024 was around 23.3 °C, while the coldest temperature in winter exhibited an average of approximately 8.8 °C. The annual precipitation in the period 1991–2020 averaged about 286.2 mm [73].

Figure 4.

Sampling sites and socioeconomic levels in Santiago de Chile.

Santiago is a city characterized by significant social segregation and an uneven distribution of green spaces. Higher-income residents predominantly inhabit the northeastern section of the city, which also boasts the most extensive vegetation coverage. Indeed, neighborhoods populated by individuals with greater financial means tend to feature larger green spaces, a higher density of trees, and a broader diversity of plant species compared to those inhabited by lower-income communities [32,74].

Santiago’s urban forest is diverse but exhibits a widespread use of introduced ornamental species for landscaping. At the city level, previous research has found that introduced species dominate the urban forest, with more than 80% of vascular flora and trees being non-native species [32,75]. In urban parks, introduced plant species are also widespread [75], accounting for approximately 70% of the park’s trees [39]. Several of these introduced plants originate from temperate regions with higher precipitation than central Chile, which entails high irrigation costs, especially during the dry seasons (spring and summer) [41].

4.2. Selection of Sampling Sites

In our research, we sampled 120 sites located in residential areas of varying socioeconomic statuses. These sites were identified by Villaseñor & Escobar [76], who used a stratified random selection design based on neighborhood socioeconomic level (obtained from https://observatoriodeciudades.com/ (accessed on 2021)) and distance to the city’s limit to select sampling sites. Neighborhood socioeconomic status was a categorical variable with three levels: high, medium, and low. High socioeconomic neighborhoods were mainly comprised by affluent individuals, typically university-educated, with an average annual household income exceeding USD 28,800. Medium socioeconomic neighborhoods were mainly comprised by households with technical or secondary education and a mean annual income surpassing USD 13,200. Conversely, low socioeconomic neighborhoods were dominated by households with less formal education, averaging an annual income below USD 8400 [77]. Stratifying by distance to the city’s limit ensured that all socioeconomic levels had a similar proportion of sample sites at the city’s edge (less than 5 km from the city limit) and in its interior (more than 5 km from the city limit) [76].

4.3. Woody Plants Surveys

Sampling took place between September and October 2022, the reproductive season of most plants in the Southern Hemisphere. Our surveys focused on the woody plants (trees, shrubs and vines) present in the residential streetscape, including public areas (e.g., streets, verges and medians) and street-visible private areas (e.g., front gardens). Thus, in each selected site, we established an 11 m radius circular plot (380 m2) where all visible woody species were identified. These plots have been successfully used to investigate urban forest composition and structure in our city (e.g., [32,39,74]). Trees with a diameter at breast height (DBH) greater than 2.5 cm were measured for height (using an altimeter Haga©, Gothenburg, Germany), diameter at breast high (DBH using a tree caliper Haglof©, Stockholm, Sweden), and crown diameter in two directions (N–S and W–E, using a forestry measuring tape Richter©, Düren, Germany). Other woody plants taller than 1.5 m were also measured. Crown size was used to calculate the crown area (in m2, using the formula for the area of an ellipse: Area = π × diameterN-S/2 × diameterW-E/2) [39]. The origin of plants (introduced or native) was determined based on the literature [78,79] and the web page World Flora Online [80].

4.4. Statistical Analysis

Initially, we calculated six response variables for each plot: species richness of woody plants, species richness of native woody plants, species richness of non-native woody plants, abundance of woody plants, abundance of native woody plants, and abundance of non-native woody plants. To assess differences in abundance and diversity across socioeconomic groups, we employed Generalized Linear Models (GLMs) with a Poisson distribution in R software version 4.1.2 [81]. Six distinct models were developed, each focusing on one of the six response variables calculated per plot. All models included socioeconomic status as a fixed effect (categorical variable with three levels: high, medium, low). We assessed models for overdispersion by calculating the sum of the squares of the Pearson residuals and comparing it to the model’s residual degrees of freedom through chi-square tests. Given that all abundance models were overdispersed, we included sampling plots as a random effect (n = 120) using Generalized Linear Mixed Models (GLMMs) in the “lme4” package [82].

Subsequently, we compared the height (cm) and crown area (m2) of woody plants across socioeconomic groups using a Linear Mixed Effects Model (LMM). Each model included socioeconomic level as a fixed effect and sampling plot as a random effect (n = 120). Height was fitted with a log-normal distribution, whereas crown area was fitted with a normal distribution. Then, we interpreted the effect of socioeconomic level in each model and visualized the results using the “effects” package [83]. Additionally, we calculated the proportion of woody vegetation type between trees and non-trees (shrubs, vines) by socioeconomic level and applied a chi-square test to establish significant differences.

To test the hypothesis that species composition differs significantly across different socioeconomic classes, we employed a permutational multivariate analysis of variance using the adonis function within the “vegan” package [84]. The analysis was based on a community dissimilarity matrix calculated using the Bray–Curtis distance measure. We used 200 free permutations to calculate the statistical significance of the F-statistic for the main effect of socioeconomics on the species matrix. To identify species that significantly drive compositional differences between socioeconomic groups, we used the SIMPER (Similarity Percentage) analysis using the “vegan” package [84]. This analysis shows species contributions to dissimilarity between residential streetscapes of different socioeconomic levels. SIMPER performs pairwise comparisons of groups of sampling units and finds the average contributions of each species to the average overall Bray–Curtis dissimilarity [85]. It also tests the probability of getting a larger or equal average contribution in a random permutation of the group factor (999 permutations). For both adonis and SIMPER analysis, we included species with more than five individuals. None of the undetermined taxa had more than five individuals (so they were excluded from analyses). These tests were performed in R software [81].

5. Conclusions

We found evident disparities in woody plant diversity, abundance, structure, and composition in residential streetscapes of different socioeconomic levels in Santiago de Chile, a Mediterranean-climate city located in Latin America. Residential streetscapes in wealthier zones exhibit greater woody plant diversity, abundance, and size than those in poorer zones, resulting in disparities in ecosystem services for citizens living in the same city. In addition, our study showed that the percentage of native woody plants in residential streetscapes (9.7%) was even lower than that reported at the city level and in urban parks, and raises concerns given the irrigation needed to sustain the massive use of introduced plants from climates with higher precipitation. The low proportion of woody native species compared to introduced species highlights the importance of promoting the use of native plants from the local region, which is currently experiencing drier conditions due to climate change.

The inclusion of non-tree woody plants in our analysis helped to verify that the luxury effect encompasses more than just urban trees. This phenomenon also affects smaller plants, which are less prevalent in areas with low socioeconomic levels. This disparity increases the lack of access to the ecosystem services these plants can provide. The challenge for the future greening of streetscapes is to include native (or to a lesser extent, introduced) shrubs and vines in the streets and front gardens of Santiago.

To reduce these inequalities and achieve a more environmentally just city, we suggest improving governance and equity-based investment, prioritizing local native species, promoting the use of non-tree woody plants, and empowering communities through capacity building and stewardship.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.R.V.; Methodology, S.V.U., Á.V.-M. and N.R.V.; Formal analysis S.V.U., M.A.H.E. and N.R.V.; Investigation, Á.V.-M. and S.V.U.; Resources, N.R.V.; Writing—original draft preparation, S.V.U.; Writing—review and editing, Á.V.-M., M.A.H.E. and N.R.V.; Visualization, S.V.U., M.A.H.E. and N.R.V.; Supervision, N.R.V.; Project administration, S.V.U., Á.V.-M. and N.R.V.; Funding acquisition, N.R.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Data for this research were funded by ANID-FONDECYT Iniciación No. 11201045 (granted to N.R.V.) (Government of Chile). N.R.V. thanks funding ANID-FONDECYT regular No. 1252219 (granted to N.R.V.).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available because they have not yet been curated for deposition in a public repository.

Acknowledgments

Authors thank Brian Guevara and Víctor Valdivia for their assistance during fieldwork, and to three anonymous reviewers whose exhaustive review helped improve this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Woody plants from Santiago. Nomenclature followed The Plant List (2013), and the taxonomical information according to the APG IV system, origin in Chile (N: native species; I: introduced species).

Table A1.

Woody plants from Santiago. Nomenclature followed The Plant List (2013), and the taxonomical information according to the APG IV system, origin in Chile (N: native species; I: introduced species).

| Order | Family | Genus | Species | Origin |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pinopsida | Araucariaceae | Araucaria | araucana | N |

| Pinopsida | Cupressaceae | Cupressus | macrocarpa | I |

| Pinopsida | Cupressaceae | Cupressus | sp. | I |

| Pinopsida | Cupressaceae | Thuja | sp. | I |

| Pinopsida | Pinaceae | Cedrus | sp. | I |

| Pinopsida | Pinaceae | Pinus | pinaster | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Adoxaceae | Viburnum | odoratissimum | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Adoxaceae | Viburnum | tinus | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Adoxaceae | Viburnum | sp. | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Altingiaceae | Liquidambar | styraciflua | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Anacardiaceae | Schinus | areira | N |

| Magnoliopsida | Apocynaceae | Nerium | oleander | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Araliaceae | Hedera | sp. | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Araliaceae | Schefflera | arboricola | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Bignoniaceae | Catalpa | bignonioides | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Bignoniaceae | Jacaranda | mimosifolia | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Bignoniaceae | Tecoma | stans | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Cannabaceae | Celtis | australis | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Caprifoliaceae | Abelia | grandiflora | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Caprifoliaceae | Abelia | sp. | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Celastraceae | Euonymus | japonicus | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Celastraceae | Maytenus | boaria | N |

| Magnoliopsida | Elaeocarpaceae | Aristotelia | chilensis | N |

| Magnoliopsida | Elaeagnaceae | Elaeagnus | angustifolia | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Ericaceae | Arbutus | unedo | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Euphorbiaceae | Euphorbia | sp. | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Fabaceae | Acacia | dealbata | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Fabaceae | Acacia | karroo | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Fabaceae | Acacia | sp. | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Fabaceae | Bauhinia | forficata | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Fabaceae | Erythrina | crista-galli | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Fabaceae | Erythrostemon | gilliesii | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Fabaceae | Parkinsonia | aculeata | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Fabaceae | Prosopis | chilensis | N |

| Magnoliopsida | Fabaceae | Robinia | pseudoacacia | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Fabaceae | Styphnolobium | japonicum | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Fabaceae | Tara | spinosa | N |

| Magnoliopsida | Fabaceae | Vachellia | caven | N |

| Magnoliopsida | Fagaceae | Quercus | falcata | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Fagaceae | Quercus | robur | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Juglandaceae | Juglans | regia | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Lamiaceae | Salvia | rosmarinus | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Lauraceae | Cryptocarya | alba | N |

| Magnoliopsida | Lauraceae | Laurus | nobilis | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Lauraceae | Persea | americana | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Lauraceae | Persea | sp. | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Loranthaceae | Tristerix | sp. | N |

| Magnoliopsida | Lythraceae | Lagerstroemia | indica | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Lythraceae | Punica | granatum | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Magnoliaceae | Liriodendron | tulipifera | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Magnoliaceae | Magnolia | soulangeana | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Magnoliaceae | Magnolia | grandiflora | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Malvaceae | Brachychiton | acerifolius | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Malvaceae | Brachychiton | populneus | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Malvaceae | Hibiscus | boryanus | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Malvaceae | Tilia | americana | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Meliaceae | Melia | azedarach | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Moraceae | Ficus | benjamina | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Moraceae | Ficus | elastica | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Moraceae | Morus | alba | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Myrtaceae | Eucalyptus | sp. | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Myrtaceae | Myrtus | communis | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Nyctaginaceae | Bougainvillea | sp. | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Oleaceae | Fraxinus | excelsior | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Oleaceae | Jasminum | mesnyi | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Oleaceae | Ligustrum | lucidum | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Oleaceae | Ligustrum | sinense | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Oleaceae | Olea | europaea | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Pittosporaceae | Pittosporum | tenuifolium | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Pittosporaceae | Pittosporum | tobira | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Pittosporaceae | Pittosporum | undulatum | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Platanaceae | Platanus | hispanica | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Proteaceae | Grevillea | robusta | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Quillajaceae | Quillaja | saponaria | N |

| Magnoliopsida | Rosaceae | Cotoneaster | coriaceus | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Rosaceae | Cotoneaster | sp. | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Rosaceae | Eriobotrya | japonica | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Rosaceae | Malus | purpurea | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Rosaceae | Prunus | armeniaca | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Rosaceae | Prunus | cerasifera | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Rosaceae | Prunus | cerasifera f. nigra | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Rosaceae | Prunus | dulcis | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Rosaceae | Prunus | persica | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Rosaceae | Prunus | sp. | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Rosaceae | Pyracantha | coccinea | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Rosaceae | Rosa | sp. | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Rubiaceae | Coprosma | baueri | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Rutaceae | Citrus | sinensis | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Rutaceae | Citrus | reticulata | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Rutaceae | Citrus | limon | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Salicaceae | Populus | alba | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Salicaceae | Populus | deltoides | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Salicaceae | Populus | sp. | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Sapindaceae | Acer | japonicum | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Sapindaceae | Acer | negundo | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Sapindaceae | Acer | pseudoplatanus | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Scrophulariaceae | Buddleja | globosa | N |

| Magnoliopsida | Scrophulariaceae | Myoporum | laetum | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Simaroubaceae | Ailanthus | altissima | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Solanaceae | Brugmansia | arborea | N |

| Magnoliopsida | Solanaceae | Brunfelsia | pauciflora | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Solanaceae | Cestrum | parqui | N |

| Magnoliopsida | Theaceae | Camellia | sp. | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Ulmaceae | Ulmus | minor | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Winteraceae | Drimys | winteri | N |

| Magnoliopsida | Unidentified | - | Morphotype-tree-01 | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Unidentified | - | Morphotype-shrub-01 | I |

| Magnoliopsida | Unidentified | - | Morphotype-climbing-01 | I |

References

- Shao, Q.; Peng, L.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y. A Bibliometric Analysis of Urban Ecosystem Services: Structure, Evolution, and Prospects. Land 2023, 12, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmond, J.A.; Tadaki, M.; Vardoulakis, S.; Arbuthnott, K.; Coutts, A.; Demuzere, M.; Dirks, K.N.; Heaviside, C.; Lim, S.; MacIntyre, H.; et al. Health and climate related ecosystem services provided by street trees in the urban environment. Sci. J. Environ. Health A Glob. Access Sci. Source 2016, 15, S36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hidalgo, A.K. Mental health in winter cities: The effect of vegetation on streets. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 63, 127226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papafotiou, M.; Chatzijiannaki, Z.; Stilianaki, G. The effect of design of an urban park on traffic noise abatement. Acta Hortic. 2010, 881, 331–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, N.R.; Han, S.W.; Kim, J.H. Evaluation of Vegetation Configuration Models for Managing Particulate Matter along the Urban Street Environment. Forests 2022, 13, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, A.; Lou, J. Pedestrians’ and Cyclists’ Preferences for Street Greenscape Designs. Promet—Traffic Transp. 2022, 34, 367–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buriánek, V.; Novotný, R.; Hellebrandová, K.; Šrámek, V. Ground vegetation as an important factor in the biodiversity of forest ecosystems and its evaluation in regard to nitrogen deposition. J. For. Sci. 2013, 59, 238–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natsukawa, H. Raptor breeding sites indicate high taxonomic and functional diversities of wintering birds in urban ecosystems. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 60, 127066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhao, J.; Yao, M. Urban landscape-level biodiversity assessments of aquatic and terrestrial vertebrates by environmental DNA metabarcoding. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 340, 117971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, L.W.; Jenerette, G.D.; Davila, A. The luxury of vegetation and the legacy of tree biodiversity in Los Angeles, CA. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013, 116, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, M.C.; Galbraith, J.A. Connecting people with place-specific nature in cities reduces unintentional harm. Environ. Res. Ecol. 2024, 3, 023001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, L.A.; Conway, T.M.; Eisenman, T.S.; Koeser, A.K.; Barona, C.O.; Locke, D.H.; Jenerette, G.D.; Östberg, J.; Vogt, J. Beyond ‘trees are good’: Disservices, management costs, and tradeoffs in urban forestry. Ambio 2021, 50, 615–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohr, V.I.; Kendal, D.; Dobbs, C. Urban trees worldwide have low species and genetic diversity, posing high risks of tree loss as stresses from climate change increase. Acta Hortic. 2016, 1108, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amazonas, N.T.; Forrester, D.I.; Silva, C.C.; Almeida, D.R.A.; Rodrigues, R.R.; Brancalion, P.H. High diversity mixed plantations of Eucalyptus and native trees: An interface between production and restoration for the tropics. For. Ecol. Manag. 2018, 417, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüscher, A.; Barkaoui, K.; Finn, J.A.; Suter, D.; Suter, M.; Volaire, F. Using plant diversity to reduce vulnerability and increase drought resilience of permanent and sown productive grasslands. Grass Forage Sci. 2022, 77, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobedo, F.J.; Palmas-Perez, S.; Dobbs, C.; Gezan, S.; Hernandez, J. Spatio-temporal changes in structure for a mediterranean urban forest: Santiago, Chile 2002 to 2014. Forests 2016, 7, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da, C.; Li, Y.; Gao, X.; Zhang, X.; Yang, Y.; Ma, H.; Zhao, B.; Hu, T.; Ma, Y.; Liu, J.; et al. Seasonal variations in psychophysiological stress recovery from street greenery: A virtual reality study on vegetation structures and configurations. Build Environ. 2024, 266, 112058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coverdale, T.C.; Davies, A.B. Unravelling the relationship between plant diversity and vegetation structural complexity: A review and theoretical framework. J. Ecol. 2023, 111, 1378–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beninde, J.; Veith, M.; Hochkirch, A. Biodiversity in cities needs space: A meta-analysis of factors determining intra-urban biodiversity variation. Ecol. Lett. 2015, 18, 581–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Evgrafova, O.; Li, M. A predictive model for traffic noise reduction effects of street green spaces with variable widths of coniferous vegetation. Forests 2025, 16, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brune, M. Urban Trees Under Climate Change; Climate Service Center Germany: Hamburg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ponce-Donoso, M.; Vallejos-Barra, Ó.; Escobedo, F.J. Appraisal of urban trees using twelve valuation formulas and two appraiser groups. Arboric. Urban For. 2017, 43, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngao, J.; Cárdenas, M.L.; Améglio, T.; Colin, J.; Saudreau, M. Implications of urban land management on the cooling properties of urban trees: Citizen science and laboratory analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luebert, F.; Pliscoff, P. Sinopsis Bioclimática y Vegetacional de Chile, 2nd ed.; Editorial Universitaria: Santiago, Chile, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ossola, A.; Hoeppner, M.J.; Burley, H.M.; Gallagher, R.V.; Beaumont, L.J.; Leishman, M.R. The Global Urban Tree Inventory: A database of the diverse tree flora that inhabits the world’s cities. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2020, 29, 1907–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galle, N.J.; Halpern, D.; Nitoslawski, S.; Duarte, F.; Ratti, C.; Pilla, F. Mapping the diversity of street tree inventories across eight cities internationally using open data. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 61, 127099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberlain, D.; Reynolds, C.; Amar, A.; Henry, D.; Caprio, E.; Batáry, P. Wealth, water and wildlife: Landscape aridity intensifies the urban luxury effect. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2020, 29, 1595–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinfort, U.; Contreras, A.; Albornoz, F.; Reyes-Paecke, S.; Guilleminot, P. Vegetation survival and condition in public green spaces after their establishment: Evidence from a semi-arid metropolis. Int. J. Agric. Nat. Resour. 2020, 47, 90–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falfán, I.; Macgregor-fors, I. Vegetación lenosa en un paisaje urbano: A case study of tree and composition in Xalapa. Madera y Bosque 2016, 22, 95–110. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, D.S.; Wood, E.M.; Katz, N.D.; Superfisky, K.; Osborn, F.M.; Novoselov, A.; Tarczynski, J.; Bacasen, L.K. Large Cities Fall Behind in “Neighborhood Biodiversity”. Front. Conserv. Sci. 2021, 2, 734931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fratini, R.; Marone, E. Repository istituzionale dell’Università degli Studi di Firenze Green-space in Urban Areas: Evaluation of Ficiency of Public Spending for Management of Green Urban Areas. Int. J. E-Bus. Dev. 2011, 1, 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández, H.J.; Villaseñor, N.R. Twelve-year change in tree diversity and spatial segregation in the Mediterranean city of Santiago, Chile. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 29, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aznarez, C.; Svenning, J.-C.; Pacheco, J.P.; Kallesøe, F.H.; Baró, F.; Pascual, U. Luxury and legacy effects on urban biodiversity, vegetation cover and ecosystem services. NPJ Urban Sustain. 2023, 3, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewthwaite, J.M.M.; Baiotto, T.M.; Brown, B.V.; Cheung, Y.Y.; Baker, A.J.; Lehnen, C.; McGlynn, T.P.; Shirey, V.; Gonzalez, L.; Hartop, E.; et al. Drivers of arthropod biodiversity in an urban ecosystem. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 7731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hope, D.; Gries, C.; Zhu, W.; Fagan, W.F.; Redman, C.L.; Grimm, N.B.; Nelson, A.L.; Martin, C.; Kinzig, A. Socioeconomics drive urban plant diversity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 8788–8792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leong, M.; Dunn, R.R.; Trautwein, M.D. Biodiversity and socioeconomics in the city: A review of the luxury effect. Biol. Lett. 2018, 14, 20180082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgenroth, J.; O’Neil-Dunne, J.; Apiolaza, L.A. Redevelopment and the urban forest: A study of tree removal and retention during demolition activities. Appl. Geogr. 2017, 82, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uribe, S.V.; Villaseñor, N.R. Inequities in urban tree care based on socioeconomic status. Urban For. Urban Green. 2024, 96, 128363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guevara, B.; Uribe, S.V.; de la Maza, C.L.; Villaseñor, N.R. Socioeconomic Disparities in Urban Forest Diversity and Structure in Green Areas of Santiago de Chile. Plants 2024, 13, 1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henríquez, M.; Fuenzalida, J. Compensando la desigualdad de ingresos locales: El Fondo Común Municipal (FCM) en Chile. Rev. Iberoam. Estud. Munic. 2011, 4, 73–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, M.P.; Vargas, M.A.; Allamand, N. Arbolado Urbano: Desafíos y Propuestas Para la Región Metropolitana; Enel Chile: Santiago, Chile, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Castro, S.A.; Ray, C.; Figueroa, J.A.; Alfaro, M.; Orrego, F.; Vergara, P.M. Effects of the Center-Edge Gradient and Habitat Type on the Spatial Distribution of Plant Species Richness in Santiago, Chile. Plants 2025, 14, 3433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Paecke, S.; Meza, L. Jardines residenciales en Santiago de Chile: Extensión, distribución y cobertura vegetal. Rev. Chil. Hist. Nat. 2011, 84, 581–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasse Figueroa, A.; Sarella Robles, M.; Sabatini Downey, F.; Cáceres Quiero, G.; Trebilcock, M.P. Desde la segregación a la exclusión residencial ¿Dónde están los nuevos hogares pobres (2000–2017) de la ciudad de Santiago, Chile? Revista de Urbanismo 2021, 44, 39–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, H.J.; Gutiérrez, M.A.; Acuña, M.P. Urban morphological dynamics in Santiago (Chile): Proposing sustainable indicators from remote sensing. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci.—ISPRS Arch. 2016, 41, 873–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, H. Tree Pruning: A Modern Approach; International Dendrology Society: Herefordshire, UK, 2013; 209p. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J.; Wang, Q.; Li, X. Socioeconomic and spatial inequalities of street tree abundance, species diversity, and size structure in New York City. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 206, 103992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceballos, S.J.; Saravia, A.N.; Foguet, J.; Jimenez, Y.; González, M.V.; Coria, G.; Gibilisco, S.; Quiroga, P.; Aráoz, E. The legacy of neighborhood age: How the past shapes the current diversity, composition, and cover of urban trees. Urban Ecosyst. 2025, 28, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resolución de Calificación Ambiental (RCA). In Concesión Américo Vespucio Oriente. Tramo Avenida El Salto—Príncipe de Gales; Servicio de Evaluación Ambiental, Región Metropolitana de Santiago, República de Chile: Santiago, Chile, 2017.

- Threlfall, C.G.; Mata, L.; Mackie, J.A.; Hahs, A.K.; Stork, N.E.; Williams, N.S.G.; Livesley, S.J. Increasing biodiversity in urban green spaces through simple vegetation interventions. J. Appl. Ecol. 2017, 54, 1874–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Lau, K.; Yuan, C.; Chen, Y.; Xu, Y.; Ren, C.; Ng, E. Regulation of outdoor thermal comfort by trees in Hong Kong. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2017, 31, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solano-López, D.; Mora-Delgado, J.; Duque, G. Árboles notables: Un aporte a la belleza escénica de la ciudad de Cali (Colombia). Agroforestería Neotropical. 2022, 12, 17–29. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, S.; Hussain, S.; Kumar, P.; Singh, A.N. Urban trees’ potential for regulatory services in the urban environment: An exploration of carbon sequestration. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2024, 196, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgioni, M.; Quitadamo, L. Ornamental shrub capacity for absorption and accumulation of heavy metals from urban polluted soil. Acta Hortic. 2013, 990, 501–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strashok, O.; Bidolakh, D.; Zemiańska, M. Ecosystem benefits of urban woody plants for sustainable green space planning: A case study from Wroclaw. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 10999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santilli, L.; Castro, S.A.; Figueroa, J.A.; Guerrero, N.; Ray, C.; Romero-Mieres, M.; Rojas, G.; Lavandero, N. Exotic species predominates in the urban woody flora of central Chile. Gayana Bot. 2018, 75, 568–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano-Diéguez, A.M.L.; Teillier, S. Frecuencia y abundancia de especies leñosas utilizadas en espacios públicos de la ciudad de Curicó-Región del Maule Chile. Chloris Chil. 2014, 17, 2. Available online: http://www.chlorischile.cl (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Alvarado Ojeda, A.; Baldini Urrutia, A.; Guajardo Becchi, F. Árboles Urbanos de Chile: Guía de Reconocimiento. Programa de Arborización: Un Chileno, un Árbol; Corporación Nacional Foresta: Santiago, Chile, 2012; 368p. [Google Scholar]

- Escobedo, F.; Nowak, D.; Wagner, J.; De la Maza, C.; Rodríguez, M.; Crane, D.; Hernández, J. The socio-economics and management of Santiago de Chile’s public urban forests. Urban For. Urban Green. 2006, 4, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, A. El Árbol Urbano en Chile; Cuarta Edición Revisada; Ediciones Fundación Claudio Gay: Santiago, Chile, 2010; 253p. [Google Scholar]

- Link, F.; Valenzuela, F. La Estructura de la Densidad Socio–Residencial en el Área Metropolitana de Santiago; Documentos de Trabajo del IEUT; Instituto de Estudios Urbanos y Territoriales UC: Santiago, Chile, 2018; N°3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela, P. El habitar residencial de la clase media en el suburbio metropolitano: El caso de la ciudad de Santiago de Chile. In Proceedings of the III Simposio Internacional de Doctorandos en Desarrollo Urbano Sustentable en Latinoamérica y el Caribe, Santiago, Chile, 17, 24–31 March 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Grijalba, J.P. El Antejardín (Des)programado: Transformaciones y Negociaciones de un Recinto Difuso. Master’s Thesis, Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago, Chile, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Aparicio-Rengifo, R.; Figueroa-Pereira, E.A.; Ospina-Tascón, J.J. El antejardín en la ciudad: Una aproximación histórico-evolutiva. Ciudad Y Territ. Estud. Territ. 2024, 56, 1113–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faúndez, E.I. Actualización de la distribución de Boisea trivittata (Say, 1825) (Heteroptera: Rhopalidae) en Chile. Rev. Chil. De Entomol. 2023, 49, 495–498. [Google Scholar]

- De Carvalho, C.A.; Raposo, M.; Pinto-Gomes, C.; Matos, R. Native or exotic: A bibliographical review of the debate on ecological science methodologies: Valuable lessons for urban green design. Land 2022, 11, 1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leotta, L.; Toscano, S.; Ferrante, A.; Romano, D.; Francini, A. New strategies to increase the abiotic stress tolerance in woody ornamental plants in Mediterranean climate. Plants 2023, 12, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, P.; Yu, F.; Ren, Y.; Liu, D.; Li, J.; Ouyang, Z.; Wang, X. Response of ruderal diversity to an urban environment: Implications for conservation and management. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garreaud, R.D.; Boisier, J.P.; Rondanelli, R.; Montecinos, A.; Sepúlveda, H.H.; Veloso-Águila, D. The central Chile megadrought (2010–2018): A climate dynamics perspective. Int. J. Climatol. 2019, 40, 421–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, J.A.; Chandía-Jaure, R.; Cataldo-Cunich, A.; Cárdenas Muñoz, S.; Fernández Cano, F. Native Plants Can Strengthen Urban Green Infrastructure: An Experimental Case Study in the Mediterranean-Type Region of Central Chile. Plants 2025, 14, 3025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INE. Resultados Nacionales Censo 2024. 2025. Available online: https://censo2024.ine.gob.cl/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/sintesis_resultados_censo2024.pdf (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Peel, M.C.; Finlayson, B.L.; McMahon, T.A. Updated world map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2007, 11, 1633–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirección Meteorológica de Chile. Reporte Anual de la Evolución del Clima en Chile; Oficina Cambio Climático; Dirección General de Aeronáutica Civil: Santiago, Chile, 2025; 70p. [Google Scholar]

- De la Maza, C.L.; Hernández, J.; Bown, H.; Rodríguez, M.; Escobedo, F. Vegetation diversity in the Santiago de Chile urban ecosystem. Arboric. J. 2002, 26, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, J.A.; Teillier, S.; Guerrero-Leiva, N.; Ray-Bobadilla, C.; Rivano, S.; Saavedra, D.; Castro, S.A. Vascular flora in public spaces of Santiago, Chile. Gayana Botánica 2016, 73, 85–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villaseñor, N.R.; Escobar, M.A.H. Linking Socioeconomics to Biodiversity in the City: The Case of a Migrant Keystone Bird Species. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 10, 850065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gfk Chile. Estilo de Vida de los Nuevos Grupos Socioeconómicos de Chile; Gfk Chile: Santiago, Chile, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Baldini, A.; Alvarado, A.; Guajardo, F. Programa de arborización: Un chileno, un árbol. In Árboles Urbanos de Chile: Guía de Reconocimiento, 1st ed.; Colegio de Ingenieros Forestales de Chile: Santiago, Chile, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, R.; Marticorena, C.; Alarcon, D.; Baeza, C.; Cavieres, L.A.; Finot, V.L.; Fuentes, N.; Kiessling, A.; Mihoc, M.; Pauchard, A. Catalogue of the vascular plants of Chile. Gayana Bot. 2018, 75, 1–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WFO. World Flora Online. Published on the Internet. Available online: https://www.worldfloraonline.org (accessed on 15 December 2022).

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Core Team: Vienna, Austria, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bates, D.; Mächler, M.; Bolker, B.M.; Walker, S.C. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 2015, 67, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, J.; Weisberg, S. An R Companion to Applied Regression, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Oksanen, J.; Blanchet, F.G.; Friendly, M.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; McGlinn, D.; Minchin, P.R.; O’Hara, R.B.; Simpson, G.L.; Solymos, P.; et al. Vegan: Community Ecology Package. R Package Version 2.5-7. 2020. Available online: http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan (accessed on 1 March 2021).

- Clarke, K.R. Non-parametric multivariate analyses of changes in community structure. Aust. J. Ecol. 1993, 18, 117–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).