Glucose-6-Phosphate 1-Epimerase Responds to Phosphate Starvation by Regulating Carbohydrate Homeostasis in Rice and Arabidopsis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Subcellular Localization of OsG6PE and AtG6PE in the Nucleus and Plasma Membrane

2.2. Generation and Characterization of osg6pe and atg6pe Mutants

2.3. Growth Inhibition of osg6pe and atg6pe Mutants Under NP

2.4. OsG6PE Is Involved in Modulating Root Architecture Under Phosphate Stress

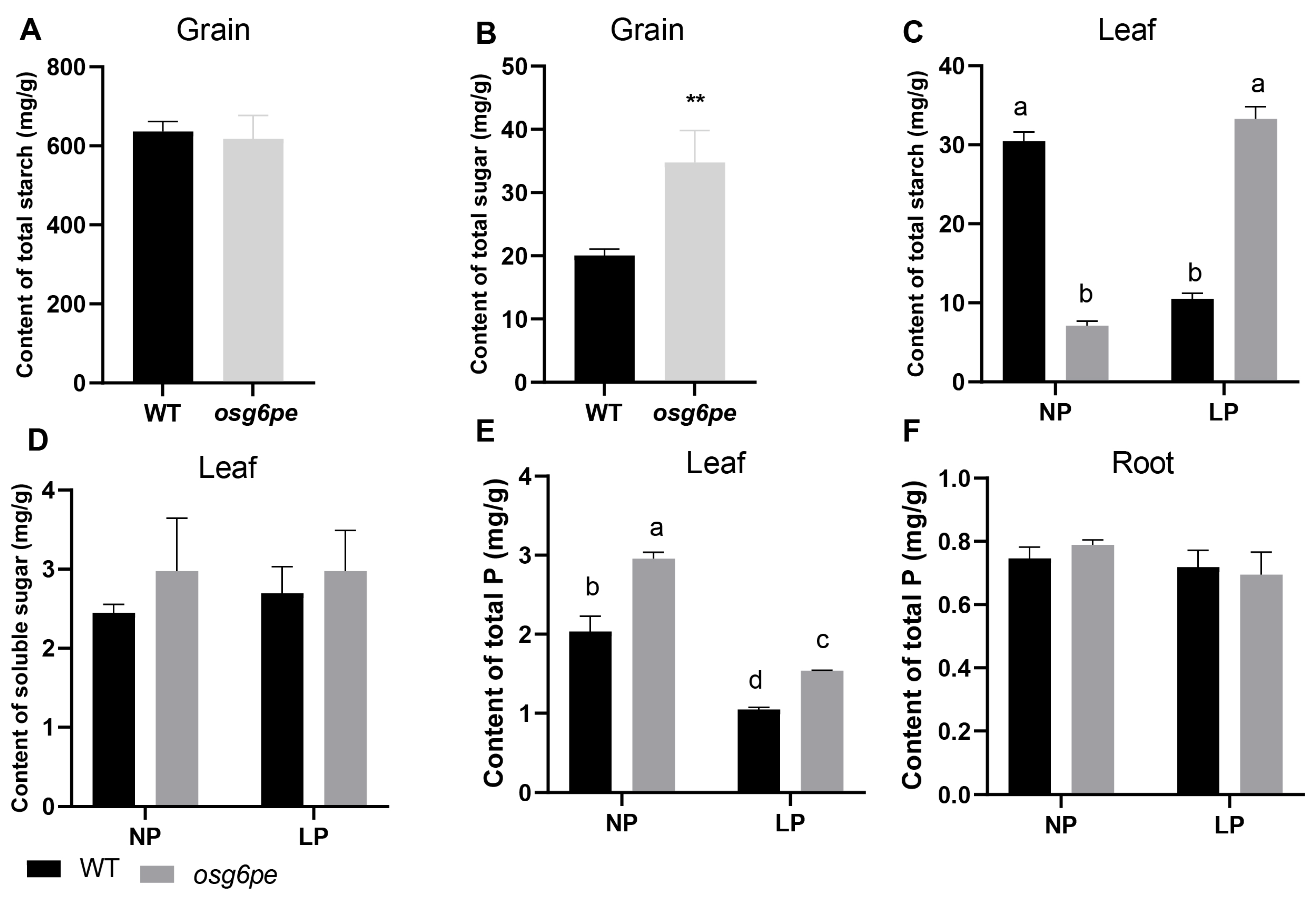

2.5. OsG6PE Regulates Carbohydrate Metabolism in Response to LP Stress

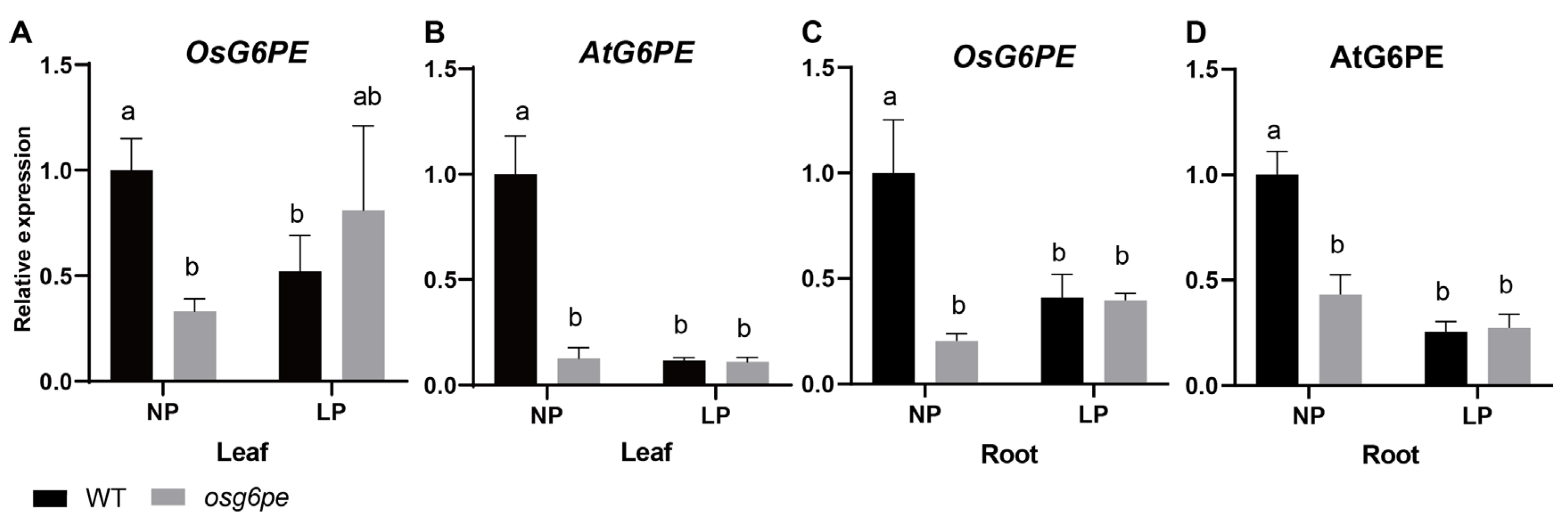

2.6. NP Conditions Suppress the Expression of OsG6PE and AtG6PE Genes in the Mutants

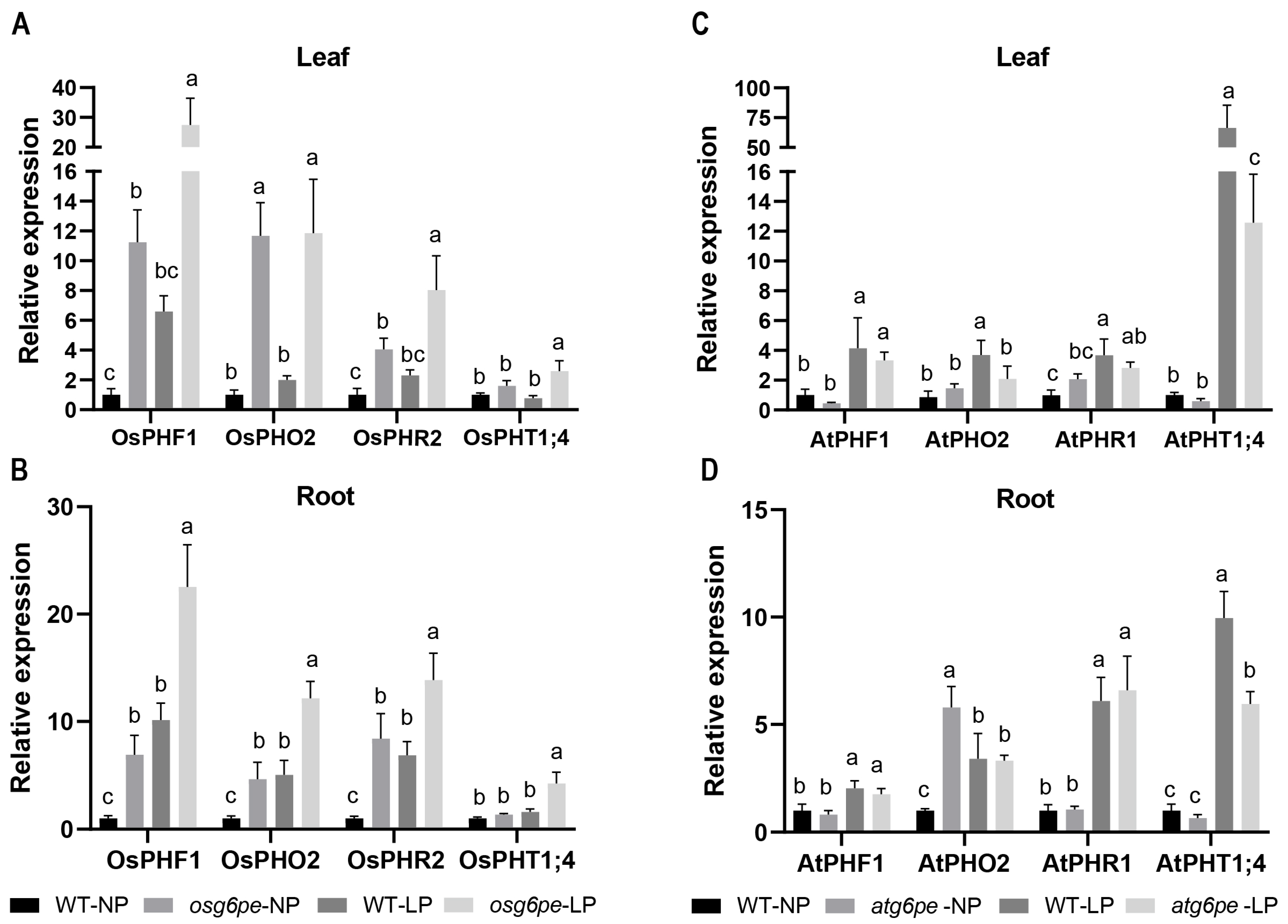

2.7. LP Conditions Promote the Expression of PSI Genes

3. Discussion

3.1. G6PE Regulates Carbon Metabolic Balance in Response to Phosphate Starvation

3.2. Phosphate Deficiency Induced Remodeling of Root System Architecture

3.3. The Role of PSI Genes Responded to LP Stress

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

4.2. Reverse Transcription–Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-qPCR) Analysis

4.3. Starch and Soluble Sugar Content Determination

4.4. Determination of Phosphorus Content

4.5. Subcellular Localization Analysis

4.6. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shen, J.; Yuan, L.; Zhang, J.; Li, H.; Bai, Z.; Chen, X.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, F. Phosphorus dynamics: From soil to plant. Plant Physiol. 2011, 156, 997–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, F.; Siddique, A.B.; Shabala, S.; Zhou, M.; Zhao, C. Phosphorus plays key roles in regulating plants’ physiological responses to abiotic stresses. Plants 2023, 12, 2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Yang, G.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, G.; Yang, G.; Wang, X.; Hu, Y. Effects of nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizer on the eating quality of indica rice with different amylose content. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2023, 118, 105167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindraban, P.S.; Dimkpa, C.O.; Pandey, R. Exploring phosphorus fertilizers and fertilization strategies for improved human and environmental health. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2020, 56, 299–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zheng, X.; Wei, X.; Kai, Z.; Xu, Y. Excessive application of chemical fertilizer and organophosphorus pesticides induced total phosphorus loss from planting causing surface water eutrophication. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 23015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penn, C.; Camberato, J. A critical review on soil chemical processes that control how soil pH affects phosphorus availability to plants. Agriculture 2019, 9, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayoumu, M.; Iqbal, A.; Muhammad, N.; Li, X.; Li, L.; Wang, X.; Gui, H.; Qi, Q.; Ruan, S.; Guo, R.; et al. Phosphorus availability affects the photosynthesis and antioxidant system of contrasting low-P-tolerant cotton genotypes. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flexas, J.; Bota, J.; Loreto, F.; Cornic, G.; Sharkey, T.D. Diffusive and metabolic limitations to photosynthesis under drought and salinity in C3 plants. Plant Biol. 2004, 6, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, S.; Li, H.; Zhang, X.; Yu, K.; Chao, M.; Han, S.; Zhang, D. Physiological and proteomics analyses reveal low-phosphorus stress affected the regulation of photosynthesis in soybean. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carstensen, A.; Herdean, A.; Schmidt, S.B.; Sharma, A.; Spetea, C.; Pribil, M.; Husted, S. The impacts of phosphorus deficiency on the photosynthetic electron transport chain. Plant Physiol. 2018, 177, 271–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, J.P.; White, P.J. Sugar signaling in root responses to low phosphorus availability. Plant Physiol. 2011, 156, 1033–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.D.; Chen, Z.Y.; Lin, Y.H.; Liang, X.G.; Wang, X.; Huang, S.B.; Munz, S.; Graeff-Hönninger, S.; Shen, S.; Zhou, S.L. Phosphorus deficiency promotes root: Shoot ratio and carbon accumulation via modulating sucrose utilization in maize. J. Plant Physiol. 2024, 303, 154349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Luo, B.; Liu, J.; Jin, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhong, H.; Li, B.; Hu, H.; Wang, Y.; Ali, A.; et al. Functional analysis of ZmG6PE reveals its role in responses to low-phosphorus stress and regulation of grain yield in maize. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1286699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Zhang, W.; Hu, X.; Shi, X.; Chen, L.; Dai, X.; Qu, H.; Xia, Y.; Liu, W.; Gu, M.; et al. Two ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase subunits, OsAGPL1 and OsAGPS1, modulate phosphorus homeostasis in rice. Plant J. 2020, 104, 1269–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bates, T.R.; Lynch, J.P. Plant growth and phosphorus accumulation of wild type and two root hair mutants of Arabidopsis thaliana (Brassicaceae). Am. J. Bot. 2000, 87, 958–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, W.; Suriyagoda, L.D.B.; Lambers, H. Tightening the phosphorus cycle through phosphorus-efficient crop genotypes. Trends Plant Sci. 2020, 25, 967–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, S.; Levengood, H.; Fan, J.; Zhang, C. Plants under stress: Exploring physiological and molecular responses to nitrogen and phosphorus deficiency. Plants 2024, 13, 3144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.; Chen, Y.; Li, R.; Yu, M.; Fu, L.; Li, S.; Su, J.; Zhu, B. Root phosphatase activity aligns with the collaboration gradient of the root economics space. New Phytol. 2022, 234, 837–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambers, H.; Shane, M.W.; Cramer, M.D.; Pearse, S.J.; Veneklaas, E.J. Root structure and functioning for efficient acquisition of phosphorus: Matching morphological and physiological traits. Ann. Bot. 2006, 98, 693–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etesami, H.; Jeong, B.R.; Glick, B.R. Contribution of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, phosphate-solubilizing bacteria, and silicon to P uptake by plant. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 699618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Guo, H.; Zhang, Q.; Guo, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, C.; Gou, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wei, J.; Chen, A.; et al. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) enhanced the growth, yield, fiber quality and phosphorus regulation in upland cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.). Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, W.; Guo, M.; Xu, L.; Wang, X.; Zhao, H.; Wang, J.; Yi, K. An SPX-RLI1 module regulates leaf inclination in response to phosphate availability in rice. Plant Cell 2018, 30, 853–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Ruan, W.; Shi, J.; Zhang, L.; Xiang, D.; Yang, C.; Li, C.; Wu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Yu, Y.; et al. Rice SPX1 and SPX2 inhibit phosphate starvation responses through interacting with PHR2 in a phosphate-dependent manner. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 14953–14958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aung, K.; Lin, S.I.; Wu, C.C.; Huang, Y.T.; Su, C.L.; Chiou, T.J. pho2, a phosphate over accumulator, is caused by a nonsense mutation in a microRNA399 target gene. Plant Physiol. 2006, 141, 1000–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, W.; Huang, T.; Chiou, T. Nitrogen limitation adaptation, a target of microRNA827, mediates degradation of plasma membrane-localized phosphate transporters to maintain phosphate homeostasis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2013, 25, 4061–4074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, E.; Solano, R.; Rubio, V.; Leyva, A.; Paz-Ares, J. Phosphate transporter traffic facilitator1 is a plant-specific SEC12-related protein that enables the endoplasmic reticulum exit of a high-affinity phosphate transporter in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2005, 17, 3500–3512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wurster, B.; Hess, B. Glucose-6-phosphate-1-epimerase from baker’s yeast. A new enzyme. FEBS Lett. 1972, 23, 341–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baune, M.C.; Lansing, H.; Fischer, K.; Meyer, T.; Charton, L.; Linka, N.; von Schaewen, A. The Arabidopsis plastidial glucose-6-phosphate transporter GPT1 is dually targeted to peroxisomes via the endoplasmic reticulum. Plant Cell 2020, 32, 1703–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graille, M.; Baltaze, J.P.; Leulliot, N.; Liger, D.; Quevillon-Cheruel, S.; van Tilbeurgh, H. Structure-based functional annotation: Yeast ymr099c codes for a D-hexose-6-phosphate mutarotase. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 30175–30185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeeman, S.C.; Smith, S.M.; Smith, A.M. The diurnal metabolism of leaf starch. Biochem. J. 2007, 401, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geigenberger, P.; Stitt, M.; Fernie, A.R. Metabolic control analysis and regulation of the conversion of sucrose to starch in growing potato tubers. Plant Cell Environ. 2004, 27, 655–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efferth, T.; Schwarzl, S.M.; Smith, J.; Osieka, R. Role of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase for oxidative stress and apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2006, 13, 527–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamani, S.; Moinier, D.; Denis, Y.; Soulere, L.; Queneau, Y.; Talla, E.; Bonnefoy, V.; Guiliani, N. Insights into the quorum sensing regulon of the acidophilic Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans revealed by transcriptomic in the presence of an acyl homoserine lactone superagonist analog. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xu, L.; Li, J.; Lyu, X.; Li, S.; Wang, C.; Wang, X.; Ma, C.; Yan, C. Multi-omics analysis of the regulatory effects of low-phosphorus stress on phosphorus transport in soybean roots. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 992036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.D.; Tang, W.; Chen, Z.Y.; Lin, Y.H.; Liang, X.G.; Wang, X.; Huang, S.B.; Munz, S.; Graeff-Hönninger, S.; Shen, S.; et al. Spatiotemporal sucrose accumulation drives tissue-specific anthocyanin biosynthesis under low phosphorus in maize. J. Integr. Agric. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Bucio, J.; Cruz-Ramírez, A.; Herrera-Estrella, L. The role of nutrient availability in regulating root architecture. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2003, 6, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puga, M.I.; Poza-Carrión, C.; Martinez-Hevia, I.; Perez-Liens, L.; Paz-Ares, J. Recent advances in research on phosphate starvation signaling in plants. J. Plant Res. 2024, 137, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chien, P.S.; Chiang, C.P.; Leong, S.J.; Chiou, T.J. Sensing and signaling of phosphate starvation: From local to long distance. Plant Cell Physiol. 2018, 59, 1714–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajmera, L.; Hodgman, T.C.; Lu, C. An integrative systems perspective on plant phosphate research. Genes. 2019, 10, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asif, I.; Dong, Q.; Wang, X.; Gui, H.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, X.; Song, M. Phosphorus and carbohydrate metabolism contributes to low phosphorus tolerance in cotton. BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 4100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermans, C.; Hammond, J.P.; White, P.J.; Verbruggen, N. How do plants respond to nutrient shortage by biomass allocation? Trends Plant Sci. 2006, 11, 610–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, J.P.; White, P.J. Sucrose transport in the phloem: Integrating root responses to phosphorus starvation. J. Exp. Bot. 2008, 59, 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaxton, W.C.; Tran, H.T. Metabolic adaptations of phosphate-starved plants. Plant Physiol. 2011, 156, 1006–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Liang, C.; Tian, J.; Xue, Y. Advances in plant lipid metabolism responses to phosphate scarcity. Plants 2022, 11, 2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales-Herrera, S.; Jourquin, J.; Coppé, F.; Lopez-Galvis, L.; De Smet, T.; Safi, A.; Njo, M.; Griffiths, C.A.; Sidda, J.D.; Mccullagh, J.S.; et al. Trehalose-6-phosphate signaling regulates lateral root formation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e1991971176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, M.; Tian, Q.; Liu, L.; Wang, H.; Song, X.; Sun, W.; Han, X. The role of sucrose in phosphate starvation response: Transcriptomic and physiological insights in Arabidopsis Thaliana. BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Liu, Y.; Ni, J.; Wang, Y.; Bai, Y.; Shi, J.; Gan, J.; Wu, Z.; Wu, P. OsPHF1 regulates the plasma membrane localization of low- and high-affinity inorganic phosphate transporters and determines inorganic phosphate uptake and translocation in rice. Plant Physiol. 2011, 157, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamburger, D.; Rezzonico, E.; MacDonald-Comber Petétot, J.; Somerville, C.; Poirier, Y. Identification and characterization of the Arabidopsis PHO1 gene involved in phosphate loading to the xylem. Plant Cell 2002, 14, 889–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bari, R.; Datt Pant, B.; Stitt, M.; Scheible, W.R. PHO2, microRNA399, and PHR1 define a phosphate-signaling pathway in plants. Plant Physiol. 2006, 141, 988–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saenchai, C.; Bouain, N.; Kisko, M.; Prom-U-Thai, C.; Doumas, P.; Rouached, H. The involvement of OsPHO1;1 in iron transport regulation occurs through the integration of phosphate and zinc deficiency signaling. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, B.; Zhang, L.; Gao, Q.; Wang, J.; Li, X.; Wang, H.; Liu, Y.; Lin, H.; Liu, J.; Wang, X.; et al. A plasma membrane transporter coordinates phosphate reallocation and grain filling in cereals. Nat. Genet. 2021, 53, 906–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secco, D.; Baumann, A.; Poirier, Y. Characterization of the rice PHO1 gene family reveals a key role for OsPHO1;2 in phosphate homeostasis and the evolution of a distinct clade in dicotyledons. Plant Physiol. 2010, 152, 1693–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Jiao, F.; Wu, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; He, X.; Zhong, W.; Wu, P. OsPHR2 is involved in phosphate-starvation signaling and excessive phosphate accumulation in shoots of plants. Plant Physiol. 2008, 146, 1673–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Wang, X.M. Role of OsPHR2 on phosphorus homeostasis and root hairs development in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant Signal Behav. 2008, 3, 674–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madison, I.; Gillan, L.; Peace, J.; Gabrieli, F.; Van den Broeck, L.; Jones, J.L.; Sozzani, R. Phosphate starvation: Response mechanisms and solutions. J. Exp. Bot. 2023, 74, 6417–6430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Zheng, Z.; Song, L.; Liu, D. Functional characterization of Arabidopsis PHL4 in plant response to phosphate starvation. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, M.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, B.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Raghothama, K.G.; Liu, D. Genetic and genomic evidence that sucrose is a global regulator of plant responses to phosphate starvation in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2011, 156, 1116–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nussaume, L.; Kanno, S.; Javot, H.; Marin, E.; Pochon, N.; Ayadi, A.; Nakanishi, T.M.; Thibaud, M.C. Phosphate import in plants: Focus on the PHT1 transporters. Front. Plant Sci. 2011, 2, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Fan, H.; Gu, M.; Qu, H.; Xu, G. Phosphate transporter OsPht1;8 in rice plays an important role in phosphorus redistribution from source to sink organs and allocation between embryo and endosperm of seeds. Plant Sci. 2015, 230, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Sun, Y.; Pei, W.; Jain, A.; Sun, R.; Cao, Y.; Wu, X.; Jiang, T.; Zhang, L.; Fan, X.; et al. Involvement of OsPht1;4 in phosphate acquisition and mobilization facilitates embryo development in rice. Plant J. 2015, 82, 556–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, H.; Zhang, S.; Guo, Y.; You, L.; Ma, H.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Luo, B.; Zhang, X.; Liu, D.; et al. Glucose-6-Phosphate 1-Epimerase Responds to Phosphate Starvation by Regulating Carbohydrate Homeostasis in Rice and Arabidopsis. Plants 2025, 14, 3869. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243869

Zhang H, Zhang S, Guo Y, You L, Ma H, Cao Y, Zhang H, Luo B, Zhang X, Liu D, et al. Glucose-6-Phosphate 1-Epimerase Responds to Phosphate Starvation by Regulating Carbohydrate Homeostasis in Rice and Arabidopsis. Plants. 2025; 14(24):3869. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243869

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Hongkai, Shuhao Zhang, Youming Guo, Luyao You, Hongqian Ma, Yubao Cao, Haiying Zhang, Bowen Luo, Xiao Zhang, Dan Liu, and et al. 2025. "Glucose-6-Phosphate 1-Epimerase Responds to Phosphate Starvation by Regulating Carbohydrate Homeostasis in Rice and Arabidopsis" Plants 14, no. 24: 3869. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243869

APA StyleZhang, H., Zhang, S., Guo, Y., You, L., Ma, H., Cao, Y., Zhang, H., Luo, B., Zhang, X., Liu, D., Wu, L., Gao, D., Gao, S., Han, B., Zhang, G., Li, J., Feng, Z., Li, D., Ma, Y., ... Gao, S. (2025). Glucose-6-Phosphate 1-Epimerase Responds to Phosphate Starvation by Regulating Carbohydrate Homeostasis in Rice and Arabidopsis. Plants, 14(24), 3869. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14243869