Abstract

Reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) is a powerful and widely used technique for quantifying alterations in gene expression. Cassava bacterial blight caused by Xanthomonas phaseoli pv. manihotis severely constraints cassava growth and yield. Accurate evaluation of the expression levels of genes following infection by X. phaseoli pv. manihotis is crucial for the identification of potential cassava resistance genes. In this study, thirty-two novel potential reference genes were screened from the cassava–X. phaseoli pv. manihotis transcriptome. Their expression, along with that of seven literature-reported cassava reference genes, was evaluated in two susceptible and two resistant cassava varieties at six time points post-inoculation by X. phaseoli pv. manihotis through RT-qPCR analysis. The stability of thirty-nine candidate reference genes was assessed by four algorithms: geNorm, NormFinder, Delta Ct, and RefFinder. The results demonstrated that serving as new reference genes, MehnRNPR and MePRPF38B consistently exhibited superior expression stability over seven established reference genes under X. phaseoli pv. manihotis infection, regardless of the susceptible or resistant cassava varieties. The reliability of the reference genes was validated by assessing the expression pattern of MeNAC35 and MeSWEET10a under X. phaseoli pv. manihotis infection. The findings of this study provide valuable insights for advancing the precision of the quantification of cassava candidate genes associated with disease resistance.

1. Introduction

Cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz) is a perennial vegetatively propagated shrub widely grown in tropical and subtropical regions for starchy tuberous roots. Cassava is a vital crop for food security, serving as a dietary staple food for over one billion people worldwide [1,2]. Additionally, cassava starch is used as livestock feed and as an important raw material for various industrial applications including bioethanol production, textile processing, and pharmaceutical manufacturing [3]. However, cassava bacterial blight (CBB), caused by Xanthomonas phaseoli pv. manihotis, is considered as the most devastating bacterial disease of cassava, resulting in yield losses of up to 100% under favorable climatic conditions [4]. CBB has been reported in all regions where cassava is cultivated, posing a critical threat to food security and economic viability of cassava production. As effective chemical control methods for CBB are still unavailable, the priority approach for CBB management is to breed cultivars with high levels of resistance [5]. Therefore, the analysis of gene expressions responsive to X. phaseoli pv. manihotis infection and the identification of cassava resistance genes at the molecular level are of crucial importance, as they provide valuable genetic resources for developing cassava cultivars with enhanced CBB resistance.

Techniques for gene expression analysis in biological research mainly include semiquantitative reverse transcription, Northern blot, in situ hybridization, gene chips, RNA sequencing, and reverse-transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR). Among these, RT-qPCR is widely regarded as the favored technique for the detection of gene expression due to its high sensitivity, specificity, reproducibility, and high throughput. However, the accuracy and reliability of RT-qPCR can be profoundly impacted by various factors, such as RNA integrity and amount, reverse transcription efficiency, initial template input, qPCR amplification efficiency, and inherent technical variations [6]. To correct for these variables and ensure accurate measurements, the use of stably expressed reference genes as an internal control is a prerequisite. Ideal reference genes should maintain stable expression across the samples to be compared. Using inappropriate reference genes can compromise RT-qPCR precision or even result in incorrect conclusions [7,8].

In the pre-genomic era, reference genes were selected as internal controls mainly involved in basic cellular processes, such as actin (ACT), tubulin (TUB), 18s rRNA, elongation factor 1-α (EF1α), and polyubiquitin (UBQ), and these genes were assumed to be constantly expressed. Unfortunately, numerous studies have shown that the traditional reference genes varied largely in diverse plant species under various experimental conditions. Recent advancements in high-throughput sequencing technologies, particularly in microarray gene chips and transcriptome profiling, have offered invaluable resources for screening novel reference genes. The novel reference genes selected from transcriptome sequencing data have shown superior stability compared to those traditionally used ones in a range of plant species, including Arabidopsis [9], barley [10], wheat [11,12], rice [13,14], buckwheat [15], grape [16], maize [17], soybean [18], tomato [19,20], cotton [21], polygonaceae [22], dayflower [23], taro [24], and bamboo [25]. However, in contrast to extensive studies on reference gene validation in plant cultivars, tissues, developmental stages, and abiotic conditions, only limited research has been conducted under plant biotic stress conditions. In plant pathosystems, diverse pathogenic microbes including viruses, fungi, and bacteria can induce metabolic alterations and gene-expression reprograming in host plants [26,27,28,29]. Thus, identifying reliable reference genes from transcriptomic profiling under pathogen infection is critical for the investigation of molecular mechanisms related to disease and discovery of host disease-resistant genes. For example, in grape infected by leafroll-associated virus 3, the stable reference genes were selected as CYSP, NDUFS8, and YSL8 [30]; when infected with gray mold, VIT-17s0000g02750 and VIT-06s0004g04280 exhibited the most stable expression [31]. Similar results were obtained in tomato leaves infected with Begomovirus [32], Pseudomonas [33], Ralstonia [34], and Xanthomonas [35], respectively.

However, to date, no studies have used genome-wide screening to identify reference genes with stable expression in cassava–X. phaseoli pv. manihotis pathosystem. X. phaseoli pv. manihotis HN01, a highly virulent strain of X. phaseoli pv. manihotis, has emerged as a predominant pathogenic bacterium constraining cassava yield across all cassava growing regions in China [36]. In this study, based on the transcriptomic sequencing data in cassava, thirty-two genes were screened as prospective candidate reference genes, in response to X. phaseoli pv. manihotis CHN01 infection. Their expression stability, along with that of seven literature-reported reference genes, was assessed in two susceptible and two resistant cassava varieties at six time points post-inoculation by X. phaseoli pv. manihotis using RT-qPCR. Subsequently, four statistical algorithms, geNorm [37], NormFinder [38], Delta Ct [39], and RefFinder [40], were employed to evaluate the expression consistency of the candidate genes. In addition, MeNAC35 and MeSWEET10a, involved in cassava responses under X. phaseoli pv. manihotis infection [41,42], were tested for validation. The findings of this study contribute appropriate reference genes for future studies on excavating disease-resistant genes and exploration of disease-resistant mechanisms on the molecular level in cassava–X. phaseoli pv. manihotis pathosystem.

2. Results

2.1. Confirmation of X. phaseoli pv. manihotis Infection and Sample Conditions

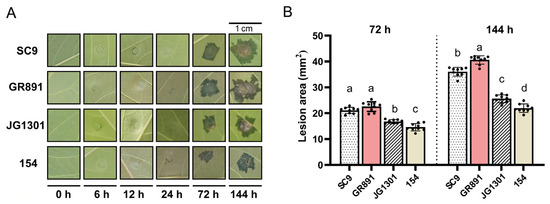

Fully expanded mature leaves of susceptible and resistant cassava varieties were inoculated with X. phaseoli pv. manihotis CHN01, respectively. As shown in Figure 1, typical water-soaking symptoms in X. phaseoli pv. manihotis-infected leaves were observed at 72 h post-inoculation (hpi), and progressed at 144 hpi. The lesion areas in two susceptible cassava varieties, GR891 and SC9, were significantly bigger than those in the resistant cassava varieties, JG1301 and 154 (an offspring of GR891-selfing progeny), both at 72 and 144 hpi. Among the four tested varieties, GR891 exhibited the largest lesion areas, followed by SC9, JG131, and 154 at 144 hpi. Between the two susceptible cassava varieties, GR891 exhibits more susceptibility than SC9, whereas between the two resistant varieties, 154 shows stronger resistance than JG1301 at 144 hpi. Leaves from four cassava varieties at six time points post X. phaseoli pv. manihotis inoculation were collected for RNA isolation and subsequent RT-qPCR analysis.

Figure 1.

Symptoms of four cassava varieties induced by X. phaseoli pv. manihotis CHN01 infection (A) and lesion areas of four cassava varieties (B) at different time points post-inoculation. Different letters a, b, c, d above the bars indicate lesion areas that are significantly different (p < 0.05) from each other as determined by one-way ANOVA (SPSS V20.0) using the Tukey–HSD method. Error bars represent standard deviation.

2.2. Reference Gene Selection, Primer Specificity, and PCR Efficiency

Based on the selection criteria derived from cassava–X. phaseoli pv. manihotis RNA-seq data, thirty-two reference genes were chosen as potential reference genes. Additionally, seven reference genes obtained from published literature were included. In total, thirty-nine genes were selected for further analysis to access their stability profiles following X. phaseoli pv. manihotis CHN01 infection, as described above. The gene name, identifier, product size, correlation coefficient (R2), amplification efficiency, and description are shown in Table 1. The primer sequences of all genes are provided in Table S1. The specificity of the primers was determined by RT-qPCR melting curve analysis. All primers for the candidate reference genes displayed a single peak, indicating that the primers had satisfactory specificity (Figure S1). The amplification product lengths ranged from 106 to 210 bp (Table 1). The amplification efficiency (E) of all 39 reference gene reactions varied from 90.7% for MePLAC8 to 109% for MeTIA1, which were all within the acceptable range of 90–110% (Table 1). Furthermore, correlation coefficients (R2) ranged from 0.982 to 0.999 (Table 1). The above results indicated that the primer pairs of these 39 candidate reference genes were suitable for subsequent RT-qPCR experiments.

Table 1.

Gene information, amplification length, efficiency, and R2 values.

2.3. Expression Analysis of the 39 Reference Genes Under X. phaseoli pv. manihotis Infection by RT-qPCR

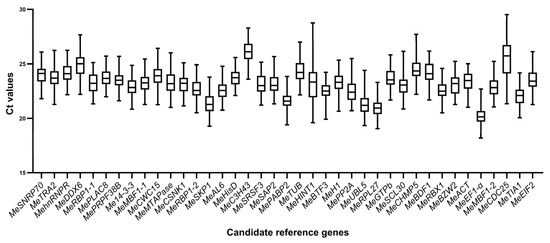

The expression levels of the 39 candidate reference genes were evaluated in 72 samples collected from leaves of four cassava varieties infected with X. phaseoli pv. manihotis CHN01 at six time points (three biological replicates per each time point), as mentioned above. The transcriptional abundances were measured by calculating the RT-qPCR Ct value (Table S2). Ct values directly reflect the abundance of gene expression, with smaller Ct values indicating higher levels of gene expression. The Ct values for all 39 potential reference genes in all samples are plotted in Figure 2. Across all samples, the Ct values of the genes exhibited a distribution between 18.19 and 29.52 for MeEF1α and MeCDC25, respectively. MeEF1α exhibited the highest expression level among 39 reference genes, characterized by the lowest mean Ct value (20.20), followed by MeRPL27 (20.94). In contrast, MeC3H43 had the highest average Ct values with the lowest expression levels (26.07). The standard deviation (SD) of the Ct values represented the variation in gene expression across the samples. MeCDC25 and MeHINT1 displayed the largest variation in expression levels, with SD values of 2.01 and 1.80, respectively, whereas MeHisD and MePRPF38B exhibited the lowest variability, with SD values of 0.73 and 0.77. Nevertheless, to guarantee the accuracy of reference gene evaluation, their stability was assessed using the following four algorithms.

Figure 2.

Ct values of the 39 candidate reference genes in cassava–X. phaseoli pv. manihotis interaction. The line across the box displays the median values. Lower and upper boxes represent the 25th percentile to the 75th percentile. Whiskers indicate the maximum and minimum Ct values.

2.4. Stability Analysis of the 39 Selected Reference Genes Using Different Algorithms

To further evaluate the consistency in expression of the 39 candidate reference genes, four different algorithms (geNorm, NormFinder, Delta CT, and RefFinder) were used to assess their stability under X. phaseoli pv. manihotis CHN01 infection at six time points. The samples were categorized into five groups: susceptible variety SC9, susceptible variety GR891, resistant variety GR891, resistant line 154, and the overall dataset (all samples).

2.4.1. GeNorm Analysis

The GeNorm algorithm assessed the stability of reference genes by calculating the gene-stability measure value (M). A smaller M value indicates a higher stability in gene expression. Additionally, a gene possessing an M value below 1.5 is considered suitable as a reference gene [37]. Across the six time points assessed (0, 12, 24, 48, 72, and 144 h post-inoculation with X. phaseoli pv. manihotis), all candidate genes showed expression stability lower than 0.9 in all five groups, indicating that all reference genes were suitable, as shown in Table 2. The stability of the candidate reference genes varied among the five groups. Under X. phaseoli pv. manihotis inoculation, in cassava susceptible variety SC9 and resistant variety JG1301, MehnRNPR had the lowest M value and was regarded as the most stable reference gene. However, in cassava susceptible variety GR891 and resistant line 154, MeSKP1 and MeEIF2 emerged as the most consistent reference genes. For all samples, MehnRNPR and MeRBP1-2 ranked as the most stable pair of reference genes, followed by MeAL6, whereas MeCDC25 was the least stable gene. Interestingly, MePP2A and MeTUB, two literature-reported reference genes, were identified as the second unstable reference genes among the 39 reference genes in susceptible varieties SC9 and GR891 under X. phaseoli pv. manihotis infection, respectively. In addition, the geNorm algorithm determines the optical number of reference genes by calculating pairwise variation (Vn/n + 1). When Vn/n + 1 is below the cutoff of 0.15, the optimal number of reference genes is n. In this study, calculated pairwise variations of all five groups were less than 0.15, which suggested the two reference genes were adequate for normalizing RT-qPCR results (Table S3).

Table 2.

Stability of expression of 39 reference genes in X. phaseoli pv. manihotis-infected cassava leaves calculated by geNorm.

2.4.2. NormFinder Analysis

The NormFinder algorithm evaluated the expression stability of candidate reference genes based on intra- and inter-group expression variations, and ranked them according to their stability value (S) [38]. A lower stability value indicates more stable gene expression. According to the stability value calculated by the NormFinder algorithm across the six time points post-inoculation by X. phaseoli pv. manihotis, MehnRNPR was identified as the most reliable reference gene across all five groups, with the exception of the SC9 variety. In contrast, MeCDC25 showed the lowest stability (Table 3). Meanwhile, MePRPF38B emerged as the most consistent gene in SC9 and ranked second and third in GR891 and JG1301, respectively, following X. phaseoli pv. manihotis infection (Table 2). Again, MePP2A and MeTUB were identified as the second-most unstable reference genes in susceptible varieties SC9 and GR891 under X. phaseoli pv. manihotis infection, respectively.

Table 3.

Stability of expression of 39 reference genes in X. phaseoli pv. manihotis-infected cassava leaves calculated by NormFinder.

2.4.3. Delta Ct Analysis

The Delta Ct algorithm analyzed the stability of the candidate reference genes by comparing the relative expression of gene pairs within each sample, using the mean standard deviation (mSD) value. A lower mSD value suggested high stability. In susceptible cassava varieties SC9 and GR891, MePRPF38B was shown to be the most stable reference gene, whereas in resistant cassava variety JG1301 and line 154, the most stable reference gene was MehnRNPR. The second stable reference gene analyzed by the Delta Ct algorithm varied among the four cassava varieties, as shown by MehnRNPR in SC9 and GR891, MeRBX1 in JG1301, and MePRPF38B in 154, respectively. MehnRNPR and MePRPF38B were shown to be the most stable genes in all samples, followed by MeRBP1-2, MeRBX1, and MeAL6, whereas MeCDC25 was the least stable (Table 4). In line with the results of geNorm and NormFinder, MePP2A and MeTUB ranked as the second-most unstable reference genes in susceptible varieties SC9 and GR891 under X. phaseoli pv. manihotis infection, respectively (Table 4).

Table 4.

Stability of expression of 39 reference genes in X. phaseoli pv. manihotis-infected cassava leaves calculated by Delta Ct.

2.4.4. RefFinder Analysis

To avoid the discrepancies evaluated by a single algorithm for stability, we utilized the online RefFinder tool to comprehensively assess the stability of the candidate reference genes by calculating the geomean of ranking values [40]. A lower geometric mean (GeoM) indicates a higher gene expression stability. As shown in Table 5, MeAL6 and MePRPF38B were the most stable reference genes in susceptible cassava varieties SC9 and GR891, respectively, whereas MehnRNPR ranked at the top in the resistant cassava variety JG1301 and line 154 across all X. phaseoli pv. manihotis inoculation stages. For all samples, MehnRNPR was the optimal candidate reference gene, followed by MePRPF38B and MeRBP1-2. MeCDC25 was the most unstable reference gene in all groups except in susceptible cassava susceptible variety SC9. In addition, MePP2A and MeHINT1 were suggested to be the most unsuitable reference genes in SC9 variety. MeTUB ranked as the second- and third-most unstable reference gene in cassava varieties GR891 and JG1301, respectively. In general, among four algorithms, MehnRNPR, MePRPF38B, MeRBP1-2, MeRBX1, and MeAL6 appeared more times at the front of the ranking, indicating these five genes are more stable. In contrast, MeCDC25 and MeHINT1 were the least stable reference genes.

Table 5.

Stability of expression of 39 reference genes in X. phaseoli pv. manihotis-infected cassava leaves calculated by RefFinder.

2.5. Validation of Candidate Reference Genes

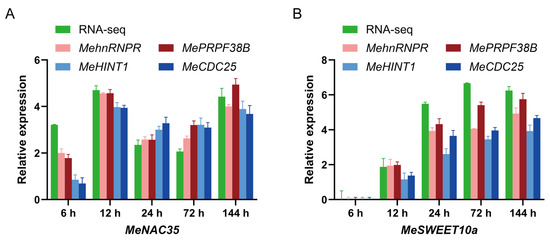

Based on the transcriptomic data of cassava–X. phaseoli pv. manihotis interaction (PRJNA881631), it was identified that MeNAC35 (Manes.03G114200) and MeSWEET10a (Manes.06G123400) were significantly differentially expressed in response to X. phaseoli pv. manihotis infection at six time points post-inoculation [41,42]. To validate the reliability of the chosen stable reference genes, the relative expression pattern of MeNAC35 and MeSWEET10a was assessed using the top-two and bottom-two performing reference genes in cassava SC8 variety under X. phaseoli pv. manihotis infection. The top-two performing reference genes, MehnRNPR and MePRPF38B, together with the bottom-two reference genes, MeHINT1 and MeCDC25, were employed for RT-qPCR evaluation and then compared with the transcriptome data. When the most stable genes of MehnRNPR and MePRPF38B were used for normalization, the relative expression trends of MeNAC35 and MeSWEET10a were similar to the transcriptome data (Figure 3A). In contrast, when the two least stable reference genes were used as the reference gene, the expression trends of MeNAC35 and MeSWEET10a varied greatly compared to the transcriptome data (Figure 3B). These findings demonstrated that the chosen reference genes were validated as accurate and reliable.

Figure 3.

The relative expression of MeNAC35 (A) and MeSWEET10a (B) were determined in cassava leaves at different time points upon Xpm infection by the use of select reference genes, including the most or least stable reference genes for normalization. The units of RNA-seq data are multiples of log2 (fold change). Error bar represents standard deviation.

3. Discussion

Cassava bacterial blight is a serious bacterial disease caused by X. phaseoli pv. manihotis, which dramatically dampened the growth and production of cassava [4]. Breeding disease-resistant cassava varieties is the most effective approach to managing CBB [5]. Expression profiling of gene changes in cassava–X. phaseoli pv. manihotis interaction provides a valuable resource for excavating the cassava resistance genes and elucidating the resistance mechanism at the molecular level [47]. Transcriptome analysis has become a powerful technology used for gene expression studies in various organisms and different treatments [48]. The data generated by RNA-seq have been extensively used in the plant research field for the selection of novel candidate reference genes [14,23,24].

In the previous studies, Hu et al. identified twenty-six cassava reference genes through analyzing their thirty-two cassava transcriptome data, and verified that MeBTF3, MeHisD, and MeC3H43 were the best reference genes in six cassava varieties (Arg7, KU50, W14, SC124, SC5, and Rongyong9) under different developmental and environmental conditions [43]. Moreno et al. found MePP2A and MeGTPb were the most stable reference genes in three CBSV-infected cassava varieties [45]. In addition, MePP2A, MeGTPb, MeTUB, and MeEF1α were used as reference genes for the normalization of gene expression in cassava upon X. phaseoli pv. manihotis infection [41,44,46]. However, there are no reports on the identification of stable reference genes for normalizing gene expression in cassava upon X. phaseoli pv. manihotis infection of susceptible and resistant genotypes. In this study, based on the cassava–X. phaseoli pv. manihotis transcriptome datasets, we identified and validated thirty-two novel candidate cassava reference genes with superior expression stability challenged by the bacterial pathogen X. phaseoli pv. manihotis, and compared them with seven literature-reported reference genes. The screening method was similar to the approach demonstrated in previous studies [24,31,43,49]. With the specific screening criteria, our novelly selected thirty-two candidate reference genes mainly function in fundamental cellular processes including RNA binding, RNA processing, RNA transcription, cell cycle control, chromatin modification, protein synthesis, and protein degradation.

Four different algorithms, geNorm, NormFinder, Delta-CT, and RefFinder, were adopted to evaluate the stability of gene expression in cassava under X. phaseoli pv. manihotis infection. In the analysis using the geNorm algorithm, the stability value of all thirty-nine genes was below the threshold of 1.5, indicating that all selected reference genes were suitable. Relatively, MeCDC25 and MeHINT1 had the worst stability among the 39 candidate reference genes analyzed by the four algorithms. This indicates that MeCDC25 and MeHINT1 are not suitable as an internal reference gene for cassava infection by X. phaseoli pv. manihotis. Additionally, in the geNorm analysis, all pairwise-variation values were below 0.15, suggesting no need to introduce a third reference gene for normalization. GeNorm analysis showed that MehnRNPR performed best in SC9, JG1301, and the entire dataset (all samples), whereas MeSKP1 and MeEIF2 ranked first in GR891 and 154. Conversely, MePRPF38B displayed higher stability in SC9 by NormFinder and Delta CT analyses. GeNorm, NormFinder, and Delta CT algorithms showed some discrepancies in the ranking of the 39 candidate reference genes, which was also observed in the previous studies and is probably due to differences in these mathematical models [25,31]. RefFinder was therefore used to comprehensively assess the expression stability of 39 candidate reference genes. Based on the results of RefFinder, MehnRNPR and MePRPF38B were recommended as the most stable reference genes in all groups except in SC9. Interestingly, MeAL6 ranked first in SC9 by RefFinder, followed by MePRPF38B and MehnRNPR.

MehnRNPR and MePRPF38B are involved in RNA processing, and MeAL6 is a PHD finger protein, which participates in chromatin modification. In line with these results, based on microarray analyses, tomato PHD and RNA-processing LSM7 genes were identified and validated as the most stably expressed reference genes in Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria-infected tomato leaves [35]. MeBTF3, MeHisD, and MeC3H43, which showed stable expression in the cassava developmental stage, were not the optimal reference genes upon X. phaseoli pv. manihotis infection in this study. Interestingly, the commonly used five reference genes in the cassava–X. phaseoli pv. manihotis pathosystem, MeACT, MeEF1a, MeTUB, MeGTPb, and MePP2A, all turned out to be unstably expressed. Similarly, in the X. campestris pv. vesicatoria–tomato pathosystem, tomato ACT, TUB, and EF-1α were identified as unstable reference genes [35]. In tomato leaf interactions with Pseudomonas fluorescens 55, EF1α was included within the least stable expression group [33]. In Nicotiana benthamiana leaves infiltrated with P.fluorescens 55, NbPP2a and NbEF1α exhibited variable gene expression [50]. In addition, in kiwifruit leaves infected with Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae, ACT, TUB, and EF-1α were marked as the unstable reference genes, whereas PP2A was the most stable gene [51]. In cucumber infected with Pectobacterium brasiliens, CsACT, CsEF-1α, and CsPP2A were not the optimal reference genes [52]. Contrastingly, in potato infected by Pectobacterium atrosepticum, ACT and EF1α exhibited the highest stability [53]. GTPb was the most appropriate reference genes in wheat and cassava infected with different viruses [41,54]. These findings highlight that suitable reference genes need to be identified and tested for each pathogenic Gram-negative bacterium–host pathosystem.

To confirm the reliability of the proposed reference genes, two genes (MeNAC35 and MeSWEET10a) from the cassava–X. phaseoli pv. manihotis transcriptome data were selected and assessed for their relative expression pattern using the two most and two least stable reference genes identified under X. phaseoli pv. manihotis infection. When MeHINT1 and MeCDC35 were used as reference genes, the expression patten of these two genes varied compared to the transcriptome data. However, when employing MehnRNPR and MePRPF38B for normalization, the expression patterns of these two genes closely paralleled the expression pattern observed in the transcriptome data. These results highlight the critical role of using stable reference genes for investigating the expression of pivotal genes in the cassava–X. phaseoli pv. manihotis pathosystem.

In summary, in this study, the expression stability of 39 candidate reference genes was investigated using four statistical algorithms across two resistant and two susceptible cassava varieties inoculated with X. phaseoli pv. manihotis, with sampling conducted at six distinct time points post-inoculation. In addition, the relative expression patterns of MeNAC35 and MeSWEET10a in cassava leaves infected by X. phaseoli pv. manihotis were analyzed to validate the reliability of the identified stable reference genes. Through screening and validation, the MehnRNPR and MePRPF38B genes were identified as the stable reference genes in the cassava–Xpm pathosystem. This is the first comprehensive study to identify and validate reference genes with RT-qPCR analysis in cassava during X. phaseoli pv. manihotis infection, encompassing both susceptible and resistant genotypes. The results will facilitate understanding the regulatory networks of host–pathogen interactions and further contribute to the identification of genes related to CBB resistance and prioritize the most promising genes for functional validation and marker-assisted cassava breeding selection.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material and X. phaseoli pv. manihotis CHN01 Inoculation

The cassava susceptible varieties SC9, GR891, and SC8 (for validation) and resistant varieties JG1301 and line 154 (an offspring of GR891-selfing progeny) were used in this study [55]. Stems of four cassava varieties, approximately 15 cm in length with two to three buds, were sub-cultured in plastic pots containing an equal mix of vermiculite and nutrient soil in a greenhouse with a 12 h/12 h photoperiod at 28 °C, 60–70% relative humidity, and with a light intensity of 130–150 µmol/m−2 s−1. The pathogenic bacterium X. phaseoli pv. manihotis CHN01 strain was cultured in solid LPGA medium at 28 °C and diluted to OD600 ≈ 0.1, approximately 108 CFU ml−1 using 10 mM MgCl2. Three expanded leaves from uniformly growing plants were infiltrated with X. phaseoli pv. manihotis CHN01 using a 1 mL sterile needleless syringe. Disease symptoms of infected cassava leaves were photographed at the six time points post-inoculation, and nine lesion areas were calculated by Image J software (V1.8.0) and analyzed by SPSS software (V20.0). Infected leaves were collected at six time points post-inoculation: 0 h post-inoculation (hpi), 6 hpi, 12 hpi, 24 hpi, 72 hpi, and 144 hpi. Leaves collected at time 0 h, immediately after infiltration, served as the control. All harvested leaves were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C for subsequent RNA isolation. All experiments were performed in triplicate and repeated at least three times.

4.2. Total RNA Extraction and cDNA Synthesis

Total RNA was extracted from cassava leaves using an RNAprep Pure Plant Plus Kit (TIANGEN, Beijing, China), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA concentration and purity were analyzed using a Nanodrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo, Wilmington, DE, USA). RNA integrity was determined by 1.0% agarose gel electrophoresis. Only RNA samples exhibiting an A260/A280 ratio ranging from 1.8 to 2.1 and an A260/A230 ratio above 1.8 were selected for subsequent cDNA synthesis. For each sample, 1 ug of total RNA was reverse-transcribed to cDNA using SPARKscript II All-In-One RT Super Mix (with gDNA eraser) (Spark, Shandong, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Three biological replicates were included for each time point of infected leaves for RNA isolation and cDNA synthesis. The synthesized cDNAs were stored at −20 °C until further use.

4.3. Selection of Candidate Reference Genes and Primer Design

The transcriptome data of cassava SC9 leaves infected with X. phaseoli pv. manihotis were obtained from the NCBI database under accession number PRJNA881631 [56]. Additionally, novel transcriptome sequencing of leaves from different cassava genotypes infected with X. phaseoli pv. manihotis at different time points post-inoculation were performed using the Illumina NovoSeq 6000 platform, and the raw sequencing data were deposited in the China National Center for Bioinformation database under accession number PRJCA049847. Briefly, total RNA was extracted from X. phaseoli pv. manihotis-infected cassava leaves harvested at different time points post-inoculation using an RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). RNA quality was assessed on an Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA), and only samples with RNA integrity numbers (RIN) greater than 7 were used for library construction. Strand-specific RNA-seq libraries were constructed using a NEBNext® Ultra™ II Directional RNA Library Prep Kit (NEB, Ipswich, MA, USA), following the manufacture’s protocol. After passing quality control (quantified by a Qubit® 2.0 Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), size distribution of approximately 400 bp on the Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100), the libraries were subjected to paired-end sequencing (2 × 150 bp) on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform. Three biological replicates were sequenced for each time point. Based on the sixty-six cassava–X. phaseoli pv. manihotis transcriptome datasets, the mean value (MV) of TPM (Transcripts Per Million) and standard deviation (SD) of TPM for each gene in each series were calculated. Furthermore, the coefficient of variation (CV, SD of TPM/mean TPM) was calculated. The genes were sorted from the smallest CV to highest CV. Genes with an average mean value (MV) greater than 50 and an average CV value less than 20% were defined as high expression levels and stable expression. Thirty-two candidate reference genes were selected (Table S4). Another seven reference genes were obtained from published literature. The gene-specific primers for all genes used for RT-qPCR were designed using the online tool Primer3plus (https://www.primer3plus.com/, accessed on 20 August 2025) with the given criteria: melting temperatures (Tm) between 55 and 65 °C, GC percentage between 45 and 60%, primer sequences spanning 18–25 base pairs, with amplicon sizes between 100 and 230 base pairs. The specificity of the primer pair sequences was further checked in Phytozome using the BLAST tool (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi accessed on 20 August 2025) All primer sets were synthesized at Sangon Biotechnology Co. (Shanghai, China). Primer sequences are shown in Table S1.

4.4. RT-qPCR Analyses

RT-qPCR was conducted on a qTOWER3 Real-Time Thermal Cycler (Analytikjena, Jena, Germany) with 384-well PCR plates. Reaction mixtures consisted of 10 µL Hieff UNICON® Universal Blue qPCR SYBR Green Master Mix (Yeasen, Shanghai, China), 0.4 µL of each 10 mM primer, ~100 ng cDNA template, with the remaining volume adjusted to 20 µL with sterile water. The thermal cycling conditions were as follows: 95 °C for 2 min, then 40 cycles of 15 s at 95 °C, and 34 s at 60 °C. After each amplification, a melting curve analysis was conducted between 60 °C and 95 °C to confirm product specificity. The RT-qPCR experiment was carried out with three biological replicates for each condition, and three technical replicates were set for each biological replicate. No template controls were included for each primer pair. A series of five-fold dilutions of the cDNA template was applied to establish the standard curves for calculating the amplification efficiency and correlation coefficients (R2) for every candidate reference gene [57].

4.5. Stability Assessment of Candidate Reference Genes

Box-plots of cycle threshold (Ct) values of the 39 candidate reference genes were plotted using GraphPad Prism 10 software (V10.4.0). Four statistical algorithms, geNorm v3.5. [37], NormFinder v20. [38], Delta Ct [39], and RefFinder [40] (http://blooge.cn/RefFinder/, accessed on 20 August 2025), were used to assess the reference gene expression stability across all five groups. Briefly, geNorm calculates a gene stability measure (M) based on the average pairwise variation between all candidate genes, NormFinder employs a model-based variance estimation approach, and the Delta-Ct method is a correlation-based approach that compares the relative pairwise expression levels between all pairs of candidate genes within each sample. For geNorm and NormFinder analysis, the original Ct value needs to be transformed into relative quantification data using the Delta Ct method. The GeNorm algorithm gives the stability value (M) and the pairwise variation value (V). The NormFinder algorithm calculates the stability value and standard error. The Delta CT method produces the mean standard deviation (mSD) value. Finally, the RefFinder website was used to comprehensively assess the stability of candidate reference genes by calculating the geomean of ranking values. BestKeeper software (V1.0) can only compare up to ten candidate reference genes together with ten target genes; therefore, BestKeeper was excluded from this study [58].

4.6. Validation of Reference Genes

The reliability of the screened reference genes was validated by examining the relative expression patterns of MeNAC35 and MeSWEET10a genes in response to Xpm infection. Both the top-two stable and the bottom-two unstable reference genes calculated by the RefFinder algorithm were chosen for normalization. The relative expression level was determined by the 2−∆∆CT approach using the raw data [57]. Three independent repetitions were performed on each sample.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/plants14233655/s1, Figure S1: The melting curves of 39 candidate reference genes; Table S1: Primer sequence of all reference genes; Table S2: Ct values of the 39 candidate reference genes in four cassava varieties at six time points post-inoculation by Xpm; Table S3: Pairwise variation analysis of 39 candidate in five groups; Table S4: The TPM values of each candidate reference gene in different cassava genotypes under Xpm infection.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.N. and Y.C.; methodology, J.Y., C.L., J.C., D.L., Q.Y., R.L. and L.Y.; validation, J.Y., D.L., Q.Y., R.L., L.Y. and S.Z.; formal analysis, J.Y., C.L. and J.C.; investigation, J.Y., C.L., J.C. and D.L.; data curation, S.Z. and X.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, X.N.; writing—review and editing, X.N.; visualization, X.N.; software, S.Z., supervision, X.N.; funding acquisition, X.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the International Science and Technology Cooperation Program of Hainan Province (GHYF2022005, GHYF2024008), the Project of Sanya Yazhou Bay Science and Technology City (SKJC-JYRC-2025-22), the Hainan Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (2019RC013), the Hainan Provincial Department of Education (Hnjg2019ZD-2), and the China Agriculture Research System (CARS-11-hncyh).

Data Availability Statement

All data are contained within the article and Supplementary Materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kistler, L.; de Oliveira Freitas, F.; Gutaker, R.M.; Maezumi, S.Y.; Ramos-Madrigal, J.; Simon, M.F.; Mendoza, F.J.M.; Drovetski, S.V.; Loiselle, H.; de Oliveira, E.J.; et al. Historic manioc genomes illuminate maintenance of diversity under long-lived clonal cultivation. Science 2025, 387, eadq0018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleadow, R.; Maher, K.; Cliff, J. Cassava. Curr. Biol. 2023, 33, R384–R386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaria, S.S.; Balasubramanian, B.; Meyyazhagan, A.; Gangwar, J.; Jaison, J.P.; Kurian, J.T.; Pushparaj, K.; Pappuswamy, M.; Park, S.; Joseph, K.S. Cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz)—A potential source of phytochemicals, food, and nutrition—An updated review. eFood 2024, 5, e127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zárate-Chaves, C.A.; Gómez de la Cruz, D.; Verdier, V.; López, C.E.; Bernal, A.; Szurek, B. Cassava diseases caused by Xanthomonas phaseoli pv. manihotis and Xanthomonas cassavae. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2021, 22, 1520–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCallum, E.J.; Anjanappa, R.B.; Gruissem, W. Tackling agriculturally relevant diseases in the staple crop cassava (Manihot esculenta). Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2017, 38, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustin, S.A.; Nolan, T. Pitfalls of quantitative real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction. J. Biomol. Tech. 2004, 15, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [PubMed Central]

- Bustin, S.A.; Benes, V.; Garson, J.A.; Hellemans, J.; Huggett, J.; Kubista, M.; Mueller, R.; Nolan, T.; Pfaffl, M.W.; Shipley, G.L.; et al. The MIQE guidelines: Minimum information for publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments. Clin. Chem. 2009, 55, 611–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, J.; Xian, K.; Fu, C.; He, J.; Liu, B.; Huang, N. Selection of suitable reference genes in Paulownia fortunei (Seem.) Hemsl. under different tissues and abiotic stresses for qPCR normalization. Czech J. Genet. Plant Breed. 2023, 59, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czechowski, T.; Stitt, M.; Altmann, T.; Udvardi, M.K.; Scheible, W.R. Genome-wide identification and testing of superior reference genes for transcript normalization in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2005, 139, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faccioli, P.; Ciceri, G.P.; Provero, P.; Stanca, A.M.; Morcia, C.; Terzi, V. A combined strategy of “in silico” transcriptome analysis and web search engine optimization allows an agile identification of reference genes suitable for normalization in gene expression studies. Plant Mol. Biol. 2006, 63, 679–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paolacci, A.R.; Tanzarella, O.A.; Porceddu, E.; Ciaffi, M. Identification and validation of reference genes for quantitative RT-PCR normalization in wheat. BMC Mol. Biol. 2009, 10, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, J.; Chen, L.; Gu, Y.; Duan, L.; Han, S.; Li, Y.; Yan, Y.; Li, X. Genome-wide identification of internal reference genes for normalization of gene expression values during endosperm development in wheat. J. Appl. Genet. 2019, 60, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narsai, R.; Ivanova, A.; Ng, S.; Whelan, J. Defining reference genes in Oryza sativausing organ, development, biotic and abiotic transcriptome datasets. BMC Plant Biol. 2010, 10, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Tang, S.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Dong, G.; Zhou, J.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, Z.; Huang, J.; Yao, Y. Rice Reference Genes: Redefining reference genes in rice by mining RNA-seq datasets. Plant Cell Physiol. 2025, 66, 120–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariño-Ramírez, L.; Demidenko, N.V.; Logacheva, M.D.; Penin, A.A. Selection and Validation of reference genes for quantitative real-time PCR in buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum) based on transcriptome sequence data. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e19434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Agüero, M.; García-Rojas, M.; Di Genova, A.; Correa, J.; Maass, A.; Orellana, A.; Hinrichsen, P. Identification of two putative reference genes from grapevine suitable for gene expression analysis in berry and related tissues derived from RNA-seq data. BMC Genom. 2013, 14, 878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, F.; Jiang, L.; Liu, Y.; Lv, Y.; Dai, H.; Zhao, H. Genome-wide identification of housekeeping genes in maize. Plant Mol. Biol. 2014, 86, 543–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amancio, S.; Yim, A.K.-Y.; Wong, J.W.-H.; Ku, Y.-S.; Qin, H.; Chan, T.-F.; Lam, H.-M. Using RNA-seq data to evaluate reference genes suitable for gene expression studies in soybean. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0136343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.-w.; Hoshikawa, K.; Fujita, S.; Thi, D.P.; Mizoguchi, T.; Ezura, H.; Ito, E. Evaluation of internal control genes for quantitative realtime PCR analyses for studying fruit development of dwarf tomato cultivar ‘Micro-Tom’. Plant Biotechnol. 2018, 35, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, Y.-k.; Han, R.; Su, Y.; Wang, A.-y.; Li, S.; Sun, H.; Gong, H.-j. Transcriptional search to identify and assess reference genes for expression analysis in Solanumlycopersicum under stress and hormone treatment conditions. J. Integr. Agric. 2022, 21, 3216–3229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smitha, P.K.; Vishnupriyan, K.; Kar, A.S.; Anil Kumar, M.; Bathula, C.; Chandrashekara, K.N.; Dhar, S.K.; Das, M. Genome wide search to identify reference genes candidates for gene expression analysis in Gossypium hirsutum. BMC Plant Biol. 2019, 19, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wu, Z.; Bao, W.; Hu, H.; Chen, M.; Chai, T.; Wang, H. Identification and evaluation of reference genes for quantitative real-time PCR analysis in Polygonum cuspidatum based on transcriptome data. BMC Plant Biol. 2019, 19, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Cao, G.; Tang, L. Selection and validation of reference genes for qRT-PCR normalization in dayflower (Commelina communis) based on the transcriptome profiling. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Chen, Q.; He, F. Transcriptome-based identification and validation of reference genes for corm growth stages, different tissues, and drought stress in taro (Colocasia esculenta). BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Mu, C.; Bai, Y.; Cheng, W.; Geng, R.; Xu, J.; Dou, Y.; Cheng, Z.; Gao, J. Selection and validation of reference genes in Dendrocalamus brandisii for quantitative real-time PCR. Plants 2024, 13, 2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfenas-Zerbini, P.; Maia, I.G.; Fávaro, R.D.; Cascardo, J.C.M.; Brommonschenkel, S.H.; Zerbini, F.M. Genome-wide analysis of differentially expressed genes during the early stages of tomato infection by a potyvirus. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact.® 2009, 22, 352–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Abarca, F.; Gervasi, F.; Ferrante, P.; Dettori, M.T.; Scortichini, M.; Verde, I. Transcriptome reprogramming of resistant and susceptible peach genotypes during Xanthomonas arboricola pv. pruni early leaf infection. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0196590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alessandra, L.; Luca, P.; Adriano, M. Differential gene expression in kernels and silks of maize lines with contrasting levels of ear rot resistance after Fusarium verticillioides infection. J. Plant Physiol. 2010, 167, 1398–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, R.K.; Gupta, S.; Das, S. Xanthomonas oryzae pv oryzae triggers immediate transcriptomic modulations in rice. BMC Genom. 2012, 13, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.; Hanner, R.H.; Meng, B. Genome-wide screening of novel RT-qPCR reference genes for study of GLRaV-3 infection in wine grapes and refinement of an RNA isolation protocol for grape berries. Plant Methods 2021, 17, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.; Lu, L.; Sun, W.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Xiang, Y.; Yan, H. Identification and validation of qRT-PCR reference genes for analyzing grape infection with gray mold. BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balestrini, R.; Lacerda, A.L.M.; Fonseca, L.N.; Blawid, R.; Boiteux, L.S.; Ribeiro, S.G.; Brasileiro, A.C.M. Reference gene selection for qPCR analysis in tomato-bipartite begomovirus interaction and validation in additional tomato-virus pathosystems. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0136820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pombo, M.A.; Zheng, Y.; Fei, Z.; Martin, G.B.; Rosli, H.G. Use of RNA-seq data to identify and validate RT-qPCR reference genes for studying the tomato-Pseudomonas pathosystem. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 44905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albuquerque, G.M.R.; Fonseca, F.C.A.; Boiteux, L.S.; Borges, R.C.F.; Miller, R.N.G.; Lopes, C.A.; Souza, E.B.; Fonseca, M.E.N. Stability analysis of reference genes for RT-qPCR assays involving compatible and incompatible Ralstonia solanacearum-tomato ‘Hawaii 7996’ interactions. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 18719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, O.A.; Grau, J.; Thieme, S.; Prochaska, H.; Adlung, N.; Sorgatz, A.; Bonas, U. Genome-wide identification and validation of reference genes in infected tomato leaves for quantitative RT-PCR analyses. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0136499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, S.; Pan, Y.; Li, K.; Fan, R.; Xiang, L.; Huang, S.; Jia, S.; Niu, X.; Li, C.; Chen, Y. Complete genome sequence of Xanthomonas phaseoli pv. manihotis strain CHN01, the causal agent of cassava bacterial blight. Plant Dis. 2022, 106, 1039–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandesompele, J.; De Preter, K.; Pattyn, F.; Poppe, B.; Van Roy, N.; De Paepe, A.; Speleman, F. Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biol. 2002, 3, research0034.1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, C.L.; Jensen, J.L.; Orntoft, T.F. Normalization of real-time quantitative reverse transcription-PCR data: A model-based variance estimation approach to identify genes suited for normalization, applied to bladder and colon cancer data sets. Cancer Res. 2004, 64, 5245–5250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silver, N.; Best, S.; Jiang, J.; Thein, S.L. Selection of housekeeping genes for gene expression studies in human reticulocytes using real-time PCR. BMC Mol. Biol. 2006, 7, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, F.; Wang, J.; Zhang, B. RefFinder: A web-based tool for comprehensively analyzing and identifying reference genes. Funct. Integr. Genom. 2023, 23, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veley, K.M.; Elliott, K.; Jensen, G.; Zhong, Z.; Feng, S.; Yoder, M.; Gilbert, K.B.; Berry, J.C.; Lin, Z.-J.D.; Ghoshal, B.; et al. Improving cassava bacterial blight resistance by editing the epigenome. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdoulaye, A.H.; Yuhua, C.; Xiaoyan, Z.; Yiwei, Y.; Wang, H.; Yinhua, C. Computational analysis and expression profiling of NAC transcription factor family involved in biotic stress response in Manihot esculenta. Plant Biol. 2024, 26, 1247–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, M.; Hu, W.; Xia, Z.; Zhou, X.; Wang, W. Validation of reference genes for relative quantitative gene expression studies in cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz) by using quantitative real-time PCR. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zárate-Chaves, C.A.; Osorio-Rodríguez, D.; Mora, R.E.; Pérez-Quintero, Á.L.; Dereeper, A.; Restrepo, S.; López, C.E.; Szurek, B.; Bernal, A. TAL effector repertoires of strains of Xanthomonas phaseoli pv. manihotis in commercial cassava crops reveal high diversity at the country scale. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, I.; Gruissem, W.; Vanderschuren, H. Reference genes for reliable potyvirus quantitation in cassava and analysis of Cassava brown streak virus load in host varieties. J. Virol. Methods 2011, 177, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Wang, P.; He, J.; Shi, H. KIN10-mediated HB16 protein phosphorylation and self-association improve cassava disease resistance by transcriptional activation of lignin biosynthesis genes. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2024, 22, 2709–2723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.J.D.; Taylor, N.J.; Bart, R. Engineering disease-resistant cassava. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2019, 11, a034595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Gerstein, M.; Snyder, M. RNA-Seq: A revolutionary tool for transcriptomics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009, 10, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Yang, F.; Feng, J.; Wang, Y.; Lachenbruch, B.; Wang, J.; Wan, X. Genome-wide constitutively expressed gene analysis and new reference gene selection based on transcriptome data: A case study from poplar/canker disease interaction. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pombo, M.A.; Ramos, R.N.; Zheng, Y.; Fei, Z.; Martin, G.B.; Rosli, H.G. Transcriptome-based identification and validation of reference genes for plant-bacteria interaction studies using Nicotiana benthamiana. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petriccione, M.; Mastrobuoni, F.; Zampella, L.; Scortichini, M. Reference gene selection for normalization of RT-qPCR gene expression data from Actinidia deliciosa leaves infected with Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 16961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Zhao, Y.; Xie, H.; Shi, Y.; Xie, X.; Chai, A.; Li, L.; Li, B. Selection and evaluation of suitable reference genes for quantitative gene expression analysis during infection of Cucumis sativus with Pectobacterium brasiliense. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 132, 3717–3734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, L.; Zhu, H.; Xian, W.; Ma, Y. Selection and validation of stable reference genes in potato infected by Pectobacterium atrosepticum using real-time quantitative PCR. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 14205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Niu, S.; Di, D.; Shi, L.; Liu, D.; Cao, X.; Miao, H.; Wang, X.; Han, C.; Yu, J.; et al. Selection of reference genes for gene expression studies in virus-infected monocots using quantitative real-time PCR. J. Biotechnol. 2013, 168, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, W.; Ji, C.; Liang, Z.; Ye, J.; Ou, W.; Ding, Z.; Zhou, G.; Tie, W.; Yan, Y.; Yang, J.; et al. Resequencing of 388 cassava accessions identifies valuable loci and selection for variation in heterozygosity. Genome Biol. 2021, 22, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Ouyang, Z.; Guo, C.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Abdoulaye, A.H.; Tang, L.; Xia, W.; Chen, Y. Identification of two cassava receptor-like cytoplasmic kinase genes related to disease resistance via genome-wide and functional analysis. Genomics 2023, 115, 110626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfaffl, M.W.; Tichopad, A.; Prgomet, C.; Neuvians, T.P. Determination of stable housekeeping genes, differentially regulated target genes and sample integrity: BestKeeper—Excel-based tool using pair-wise correlations. Biotechnol. Lett. 2004, 26, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).