Zea Maize Calmodulin (ZmCaM2) Regulates Drought Tolerance in Corn Plants Through an Abscisic Acid-Dependent Signaling Pathway

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

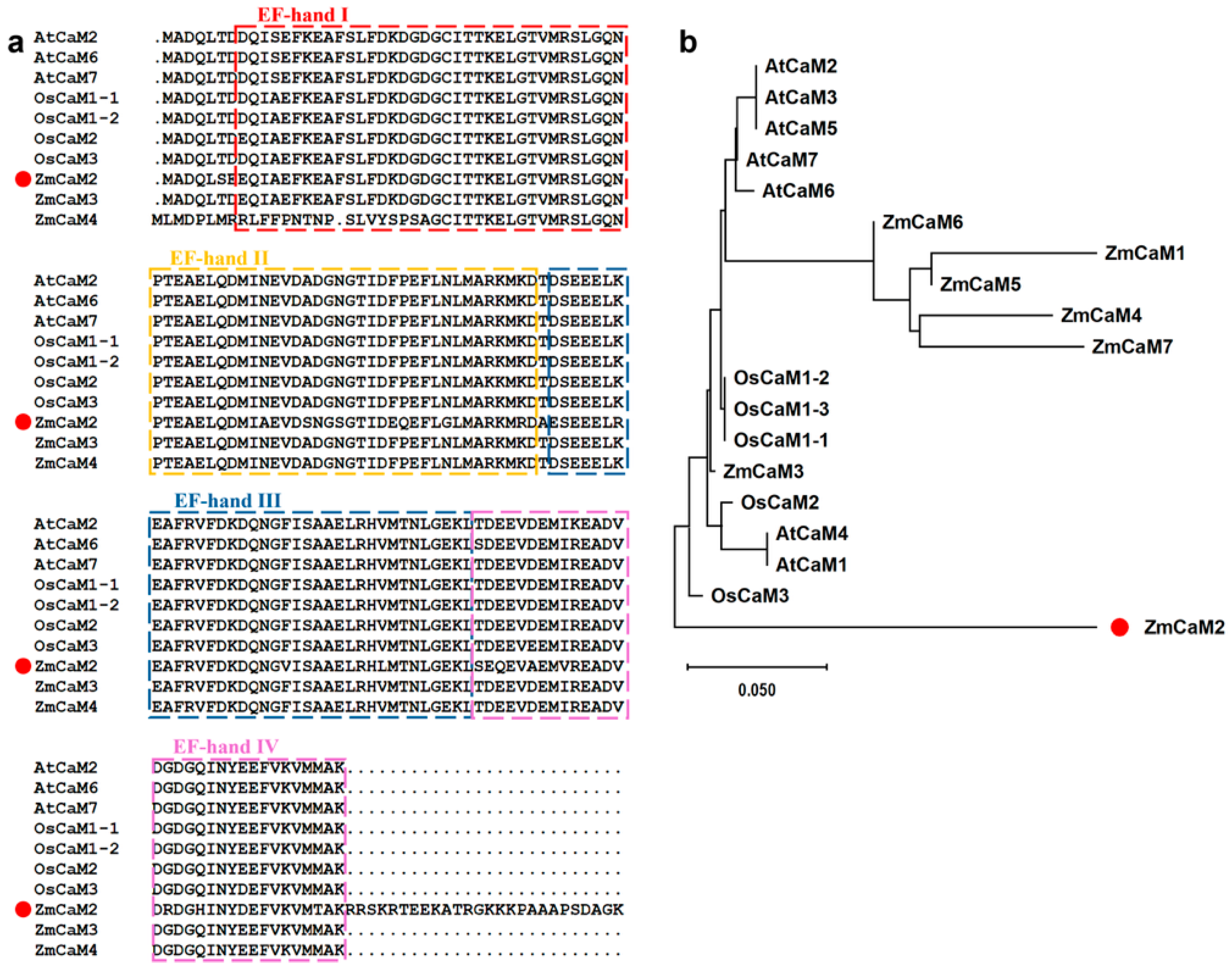

2.1. Cloning and Analysis of the ZmCaM2 Gene

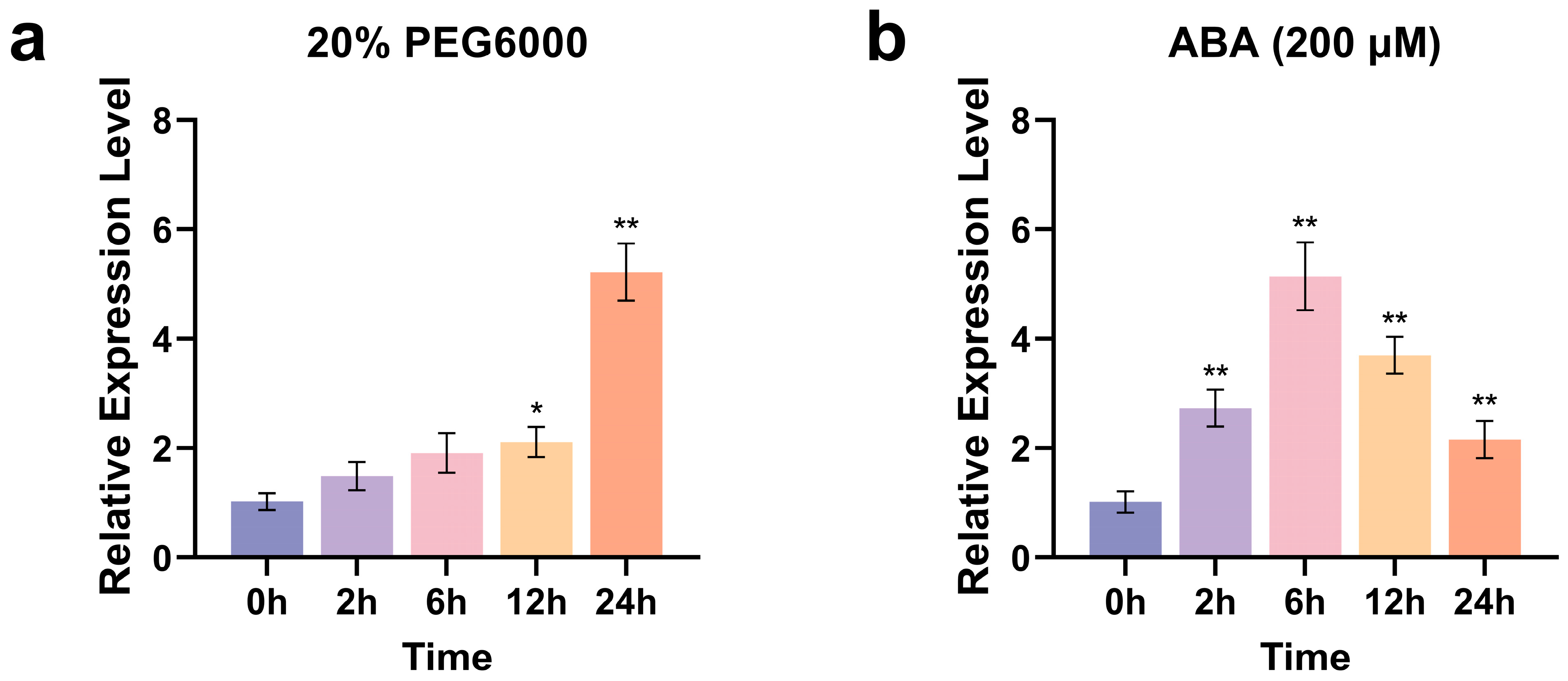

2.2. ZmCaM2 Is Involved in the Response to PEG and ABA Induced Stress

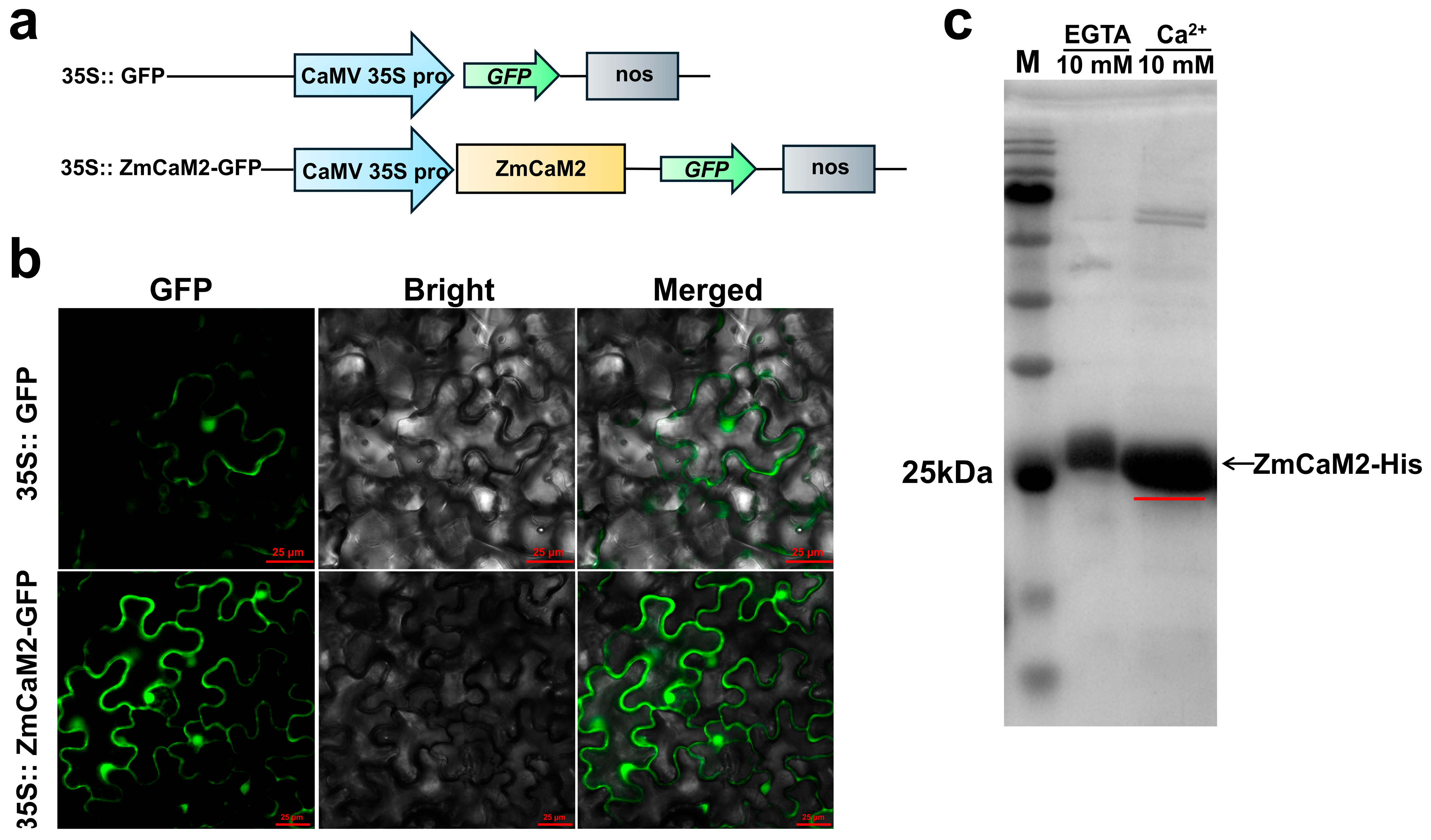

2.3. ZmCaM2 Is Localized to the Nucleus and Plasma Membrane and Can Bind Ca2+

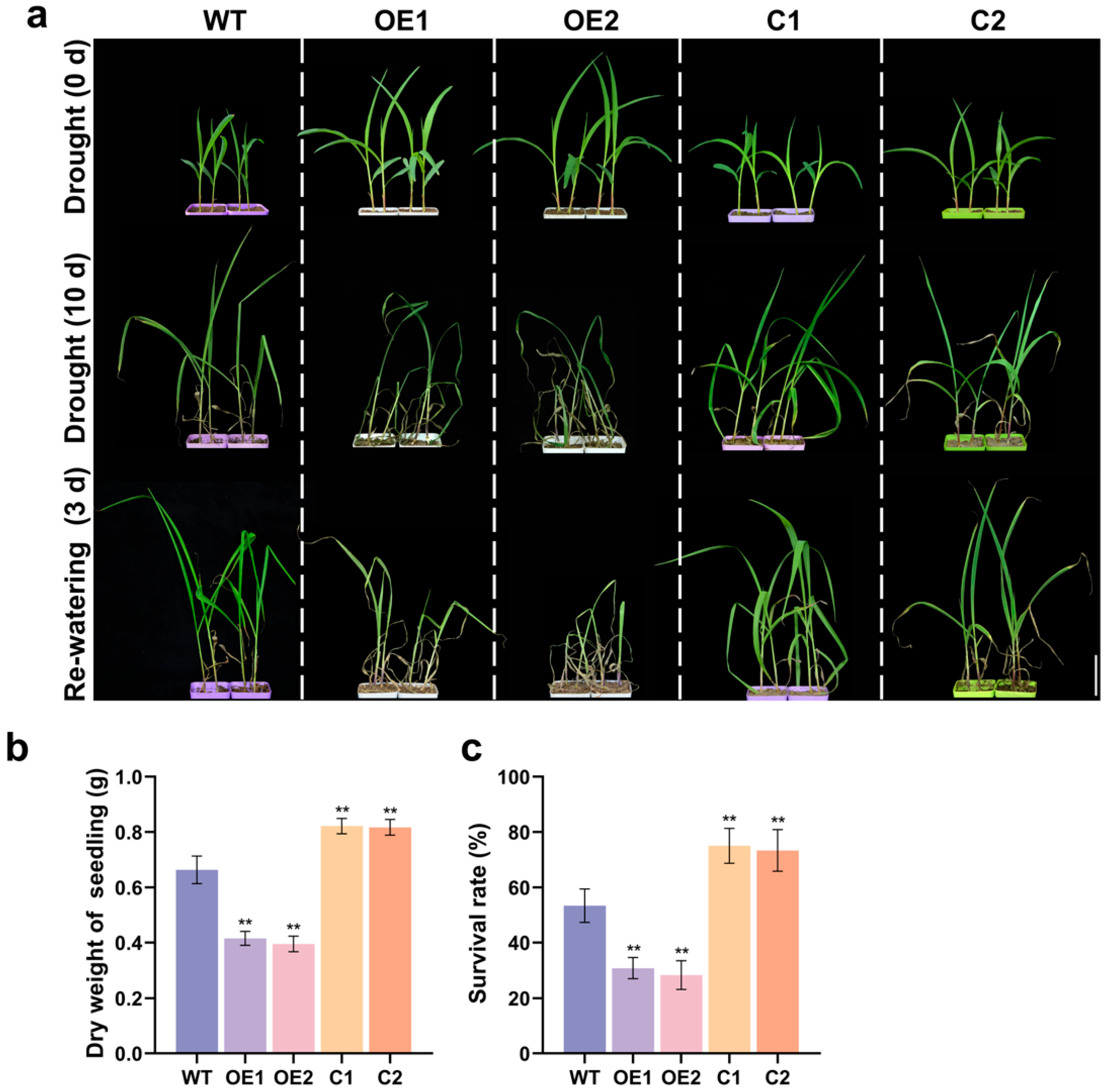

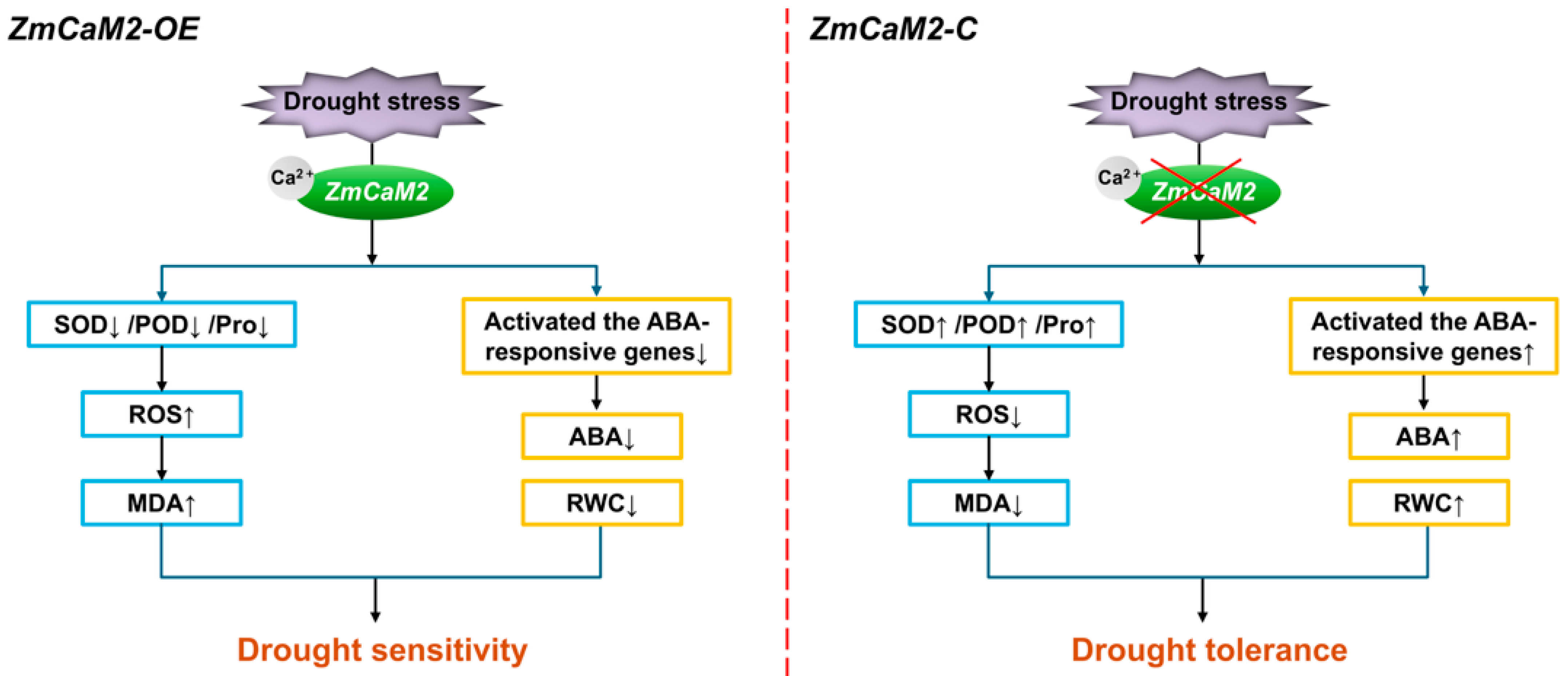

2.4. ZmCaM2 Negatively Regulates Drought Tolerance in Maize

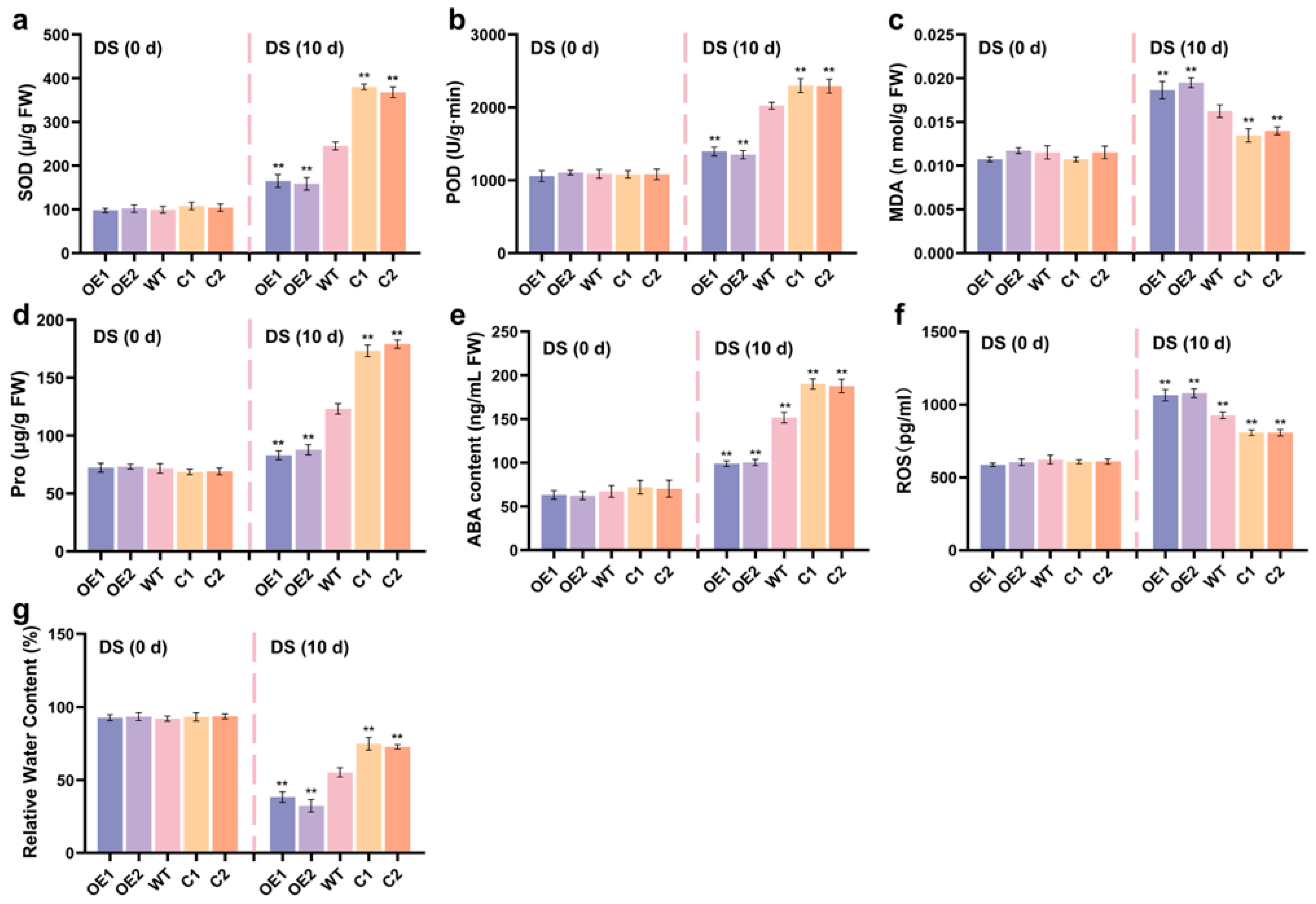

2.5. ZmCaM2 Decreases Maize Drought Tolerance by Affecting Antioxidant Enzyme Activity

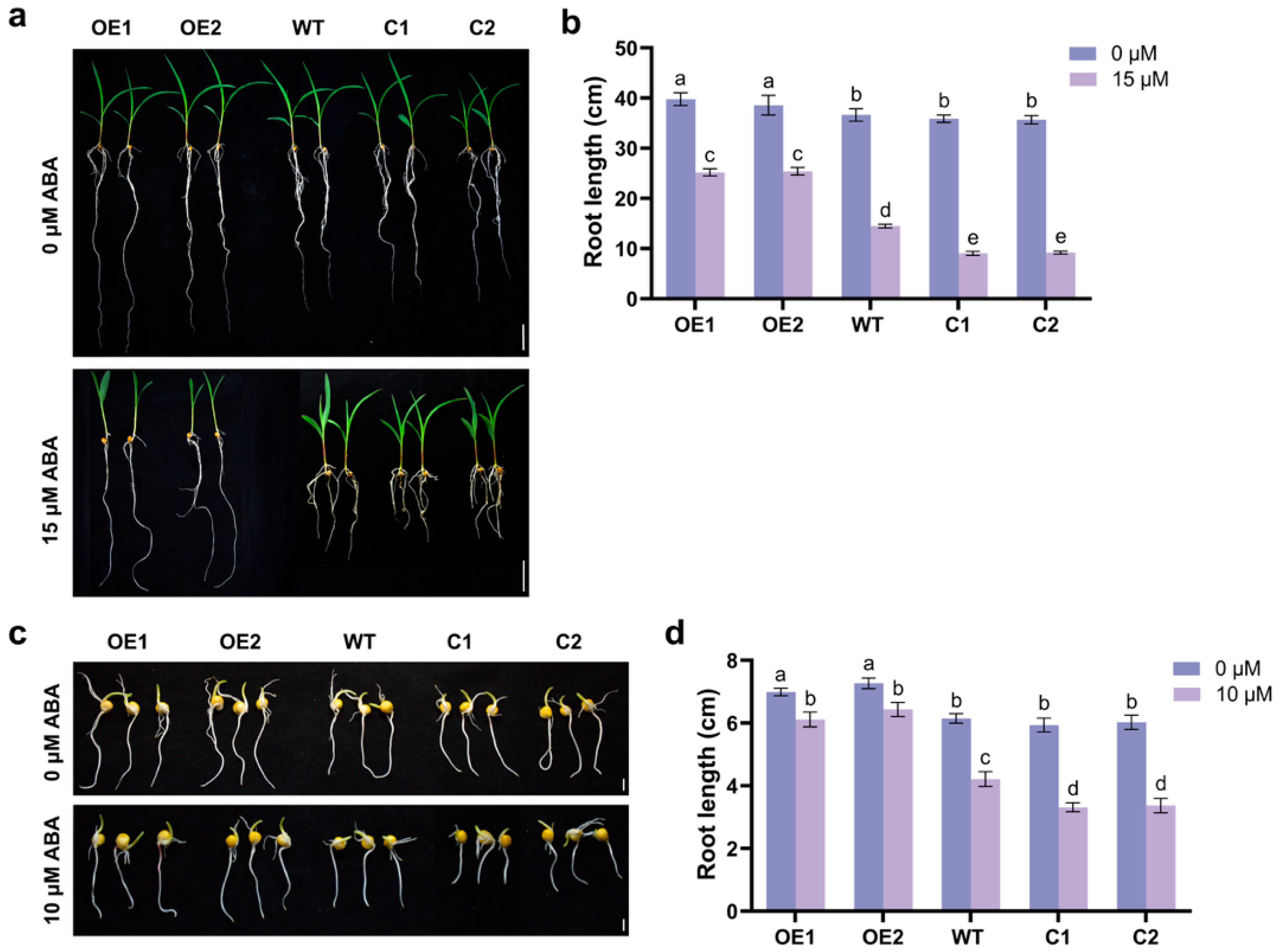

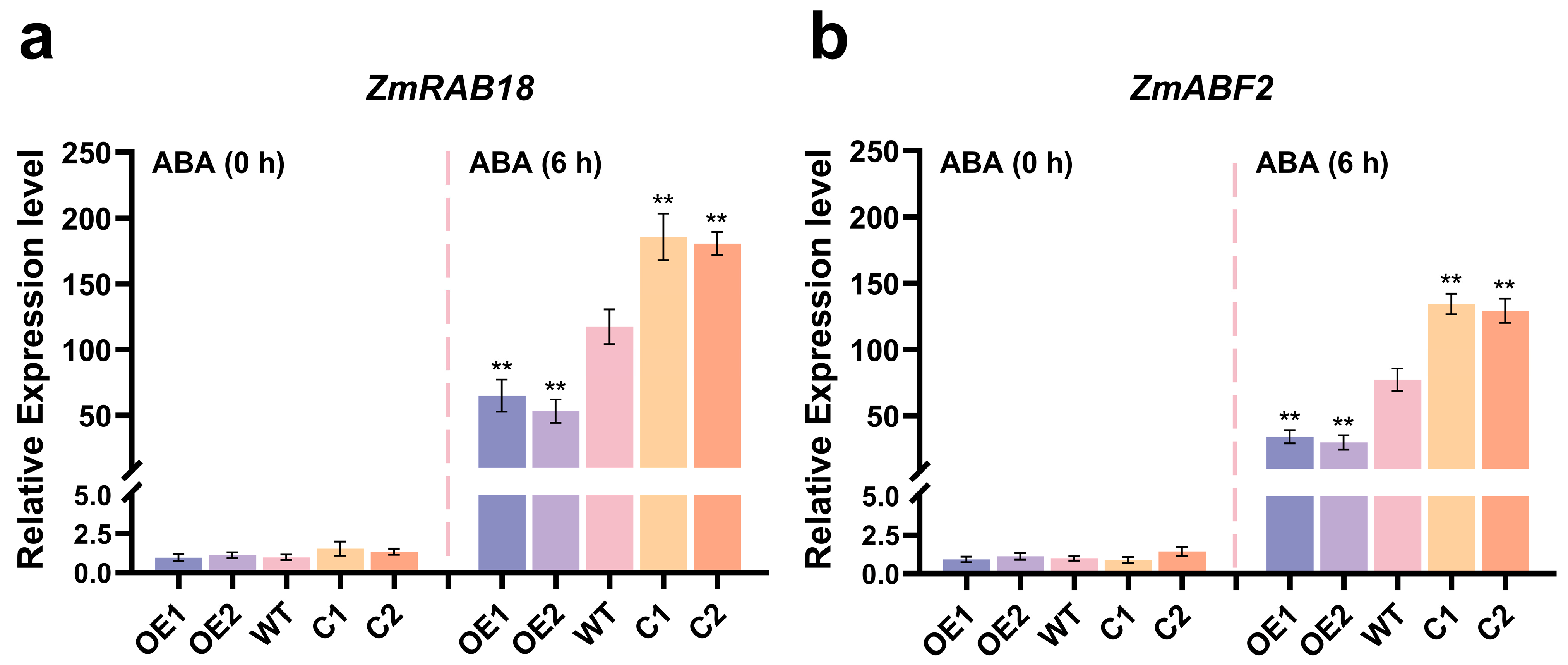

2.6. ZmCaM2 Negatively Regulates ABA Signal Transduction Pathway

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials, Growing Conditions, and Treatments

4.2. RNA Extraction and qRT-PCR

4.3. ZmCaM2 Cloning and Sequence Analysis

4.4. Subcellular Localization

4.5. Prokaryotic Expression Analysis of ZmCaM2 and Ca2+ Binding Assay

4.6. Transgenic Plant Generation and Drought Tolerance Identification

4.7. Physiological Indicators Measurement

4.8. ABA Stress Treatment

4.9. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| qRT-PCR | Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction |

| ABA | Abscisic acid |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| Ca2+ | Calcium ions |

| CaM | Calmodulin |

| CMLs | Calmodulin-like proteins |

| CDPKs | Calcium-dependent protein kinases |

| CBLs | Calcineurin B-like proteins |

| CCaMKs | Calcium and calmodulin -dependent protein kinases |

| GFP | Green fluorescent protein |

| WT | Wild type |

| h | Hour |

| d | Day |

| V3 | Third-leaf stage |

| CDS | Coding sequence |

| RWC | Relative water content |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| POD | Peroxidase |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| Pro | Proline |

| PI | Isoelectric point |

| GRAVY | Grand Average of Hy-dropathicity |

| MW | Molecular weight |

| RT-PCR | Reverse transcription PCR |

References

- Zia, R.; Nawaz, M.S.; Siddique, M.J.; Hakim, S.; Imran, A. Plant survival under drought stress: Implications, adaptive responses, and integrated rhizosphere management strategy for stress mitigation. Microbiol. Res. 2021, 242, 126626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Qin, F. The battle of crops against drought: Genetic dissection and improvement. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2023, 65, 496–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daryanto, S.; Wang, L.; Jacinthe, P.A. Global Synthesis of Drought Effects on Maize and Wheat Production. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0156362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadava, P.; Abhishek, A.; Singh, R.; Singh, I.; Kaul, T.; Pattanayak, A.; Agrawal, P.K. Advances in Maize Transformation Technologies and Development of Transgenic Maize. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 7, 1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheoran, S.; Kaur, Y.; Kumar, S.; Shukla, S.; Rakshit, S.; Kumar, R. Recent Advances for Drought Stress Tolerance in Maize (Zea mays L.): Present Status and Future Prospects. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 872566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, P.; Du, L.; Poovaiah, B.W. Ca2+/Calmodulin-Dependent AtSR1/CAMTA3 Plays Critical Roles in Balancing Plant Growth and Immunity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldon, D.; Mbengue, M.; Mazars, C.; Galaud, J.P. Calcium signalling in plant biotic interactions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iqbal, Z.; Shariq Iqbal, M.; Singh, S.P.; Buaboocha, T. Ca2+/Calmodulin Complex Triggers CAMTA Transcriptional Machinery Under Stress in Plants: Signaling Cascade and Molecular Regulation. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 598327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamel, L.P.; Sheen, J.; Séguin, A. Ancient signals: Comparative genomics of green plant CDPKs. Trends Plant Sci. 2014, 19, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.P.; Munyampundu, J.P.; Xu, Y.P.; Cai, X.Z. Phylogeny of Plant Calcium and Calmodulin-Dependent Protein Kinases (CCaMKs) and Functional Analyses of Tomato CCaMK in Disease Resistance. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanyal, S.K.; Mahiwal, S.; Nambiar, D.M.; Pandey, G.K. CBL-CIPK module-mediated phosphoregulation: Facts and hypothesis. Biochem. J. 2020, 477, 853–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, A.S.; Ali, G.S.; Celesnik, H.; Day, I.S. Coping with stresses: Roles of calcium- and calcium/calmodulin-regulated gene expression. Plant Cell 2011, 23, 2010–2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranty, B.; Aldon, D.; Cotelle, V.; Galaud, J.P.; Thuleau, P.; Mazars, C. Calcium Sensors as Key Hubs in Plant Responses to Biotic and Abiotic Stresses. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCormack, E.; Tsai, Y.C.; Braam, J. Handling calcium signaling: Arabidopsis CaMs and CMLs. Trends Plant Sci. 2005, 10, 383–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Dunand, C.; Snedden, W.; Galaud, J.P. CaM and CML emergence in the green lineage. Trends. Plant Sci. 2015, 20, 483–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonburapong, B.; Buaboocha, T. Genome-wide identification and analyses of the rice calmodulin and related potential calcium sensor proteins. BMC Plant Biol. 2007, 7, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- He, X.; Liu, W.; Li, W.; Liu, Y.; Wang, W.; Xie, P.; Kang, Y.; Liao, L.; Qian, L.; Liu, Z.; et al. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of CaM/CML genes in Brassica napus under abiotic stress. J. Plant Physiol. 2020, 255, 153251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, M.; Wu, C.; Li, X.; Ding, X.; Guo, F. Genome-Wide Identification and Expression Analysis of CsCaM/CML Gene Family in Response to Low-Temperature and Salt Stresses in Chrysanthemum seticuspe. Plants 2022, 11, 1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, K.; Kuang, L.; Yue, W.; Xie, S.; Xia, X.; Zhang, G.; Wang, J. Calmodulin and calmodulin-like gene family in barley: Identification, characterization and expression analyses. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 964888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, W.; Liu, L.; Su, Y.; Li, Y.; Jia, W.; Jiao, B.; Wang, J.; Yang, F.; Dong, F.; et al. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of calmodulin and calmodulin-like genes in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Plant Signal Behav. 2022, 17, 2013646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandelle, E.; Vannozzi, A.; Wong, D.; Danzi, D.; Digby, A.M.; Dal Santo, S.; Astegno, A. Identification, characterization, and expression analysis of calmodulin and calmodulin-like genes in grapevine (Vitis vinifera) reveal likely roles in stress responses. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 129, 221–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.C.; Chung, W.S.; Yun, D.J.; Cho, M.J. Calcium and calmodulin-mediated regulation of gene expression in plants. Mol. Plant 2009, 2, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, J.H.; Park, C.Y.; Kim, J.C.; Heo, W.D.; Cheong, M.S.; Park, H.C.; Kim, M.C.; Moon, B.C.; Choi, M.S.; Kang, Y.H.; et al. Direct interaction of a divergent CaM isoform and the transcription factor, MYB2, enhances salt tolerance in arabidopsis. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 3697–3706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, S.S.; El-Habbak, M.H.; Havens, W.M.; Singh, A.; Zheng, D.; Vaughn, L.; Haudenshield, J.S.; Hartman, G.L.; Korban, S.S.; Ghabrial, S.A. Overexpression of GmCaM4 in soybean enhances resistance to pathogens and tolerance to salt stress. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2014, 15, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saeng-ngam, S.; Takpirom, W.; Buaboocha, T.; Chadchawan, S. The role of the OsCam1-1 salt stress sensor in ABA accumulation and salt tolerance in rice. J. Plant Biol. 2012, 55, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.C.; Luo, D.L.; Vignols, F.; Jinn, T.L. Heat shock-induced biphasic Ca(2+) signature and OsCaM1-1 nuclear localization mediate downstream signalling in acquisition of thermotolerance in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant Cell Environ. 2012, 35, 1543–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Ji, L.; Liu, S.; Jing, P.; Hu, J.; Jin, D.; Wang, L.; Xie, G. The CaM1-associated CCaMK-MKK1/6 cascade positively affects lateral root growth via auxin signaling under salt stress in rice. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 6611–6627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Jia, L.; Chu, H.; Wu, D.; Peng, X.; Liu, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, J.; Chen, K.; Zhao, L. Arabidopsis CaM1 and CaM4 Promote Nitric Oxide Production and Salt Resistance by Inhibiting S-Nitrosoglutathione Reductase via Direct Binding. PLoS Genet. 2016, 12, e1006255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, C.; Lee, Y.; Lee, I.C.; Nam, H.G.; Kwak, J.M. Calmodulin 1 Regulates Senescence and ABA Response in Arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, F.; Mizoguchi, T.; Yoshida, R.; Ichimura, K.; Shinozaki, K. Calmodulin-dependent activation of MAP kinase for ROS homeostasis in Arabidopsis. Mol. Cell 2011, 41, 649–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, M.; Li, J.; Zhang, J.; Shen, S.; Li, C.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, S. AtCaM4 interacts with a Sec14-like protein, PATL1, to regulate freezing tolerance in Arabidopsis in a CBF-independent manner. J. Exp. Bot. 2018, 69, 5241–5253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xuan, Y.; Zhou, S.; Wang, L.; Cheng, Y.; Zhao, L. Nitric oxide functions as a signal and acts upstream of AtCaM3 in thermotolerance in Arabidopsis seedlings. Plant Physiol. 2010, 153, 1895–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; Peng, C.; Cheng, D.; Huang, Q.; Xu, G.; Gao, F.; Chen, L. The over-expression of calmodulin from Antarctic notothenioid fish increases cold tolerance in tobacco. Gene 2013, 521, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Cerro, P.; Cook, N.M.; Huisman, R.; Dangeville, P.; Grubb, L.E.; Marchal, C.; Ho Ching Lam, A.; Charpentier, M. Engineered CaM2 modulates nuclear calcium oscillation and enhances legume root nodule symbiosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2200099119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Yan, S.; Zhou, H.; Dong, R.; Lei, J.; Chen, C.; Cao, B. Overexpression of CsCaM3 improves high temperature tolerance in cucumber. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raina, M.; Kumar, A.; Yadav, N.; Kumari, S.; Yusuf, M.A.; Mustafiz, A.; Kumar, D. StCaM2, a calcium binding protein, alleviates negative effects of salinity and drought stress in tobacco. Plant Mol. Biol. 2021, 106, 85–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Q.; Fu, L.; Su, T.; Ye, L.; Huang, L.; Kuang, L.; Wu, L.; Wu, D.; Zhang, G. Calmodulin HvCaM1 negatively regulates salt tolerance via modulation of HvHKT1s and HvCAMTA4. Plant Physiol. 2020, 183, 1650–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Jia, W.; Yang, J.; Ismail, A.M. Role of ABA in integrating plant responses to drought and salt stresses. Field Crops Res. 2006, 97, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgher, M.; Khan, M.I.R.; Anjum, N.A.; Khan, N.A. Minimising toxicity of cadmium in plants—Role of plant growth regulators. Protoplasma 2015, 252, 399–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, Z.; Xiong, L.; Shi, H.; Yang, S.; Herrera-Estrella, L.R.; Xu, G.; Chao, D.Y.; Li, J.; Wang, P.Y.; Qin, F.; et al. Plant abiotic stress response and nutrient use efficiency. Sci. China Life Sci. 2020, 63, 635–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanderbeld, B.; Snedden, W.A. Developmental and stimulus-induced expression patterns of Arabidopsis calmodulin-like genes CML37, CML38 and CML39. Plant Mol. Biol. 2007, 64, 683–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnan, F.; Ranty, B.; Charpenteau, M.; Sotta, B.; Galaud, J.P.; Aldon, D. Mutations in AtCML9, a calmodulin-like protein from Arabidopsis thaliana, alter plant responses to abiotic stress and abscisic acid. Plant J. 2008, 56, 575–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Qiao, Z.; Liu, H.; Acharya, B.R.; Li, C.; Zhang, W. CML20, an Arabidopsis Calmodulin-like Protein, Negatively Regulates Guard Cell ABA Signaling and Drought Stress Tolerance. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamra, G.; Agarwal, A.; Singh, N.; Sanyal, S.K.; Kumar, A.; Pandey, G.K. Ectopic expression of finger millet calmodulin confers drought and salinity tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Rep. 2021, 40, 2205–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, L.; Li, J.; Yang, W.; Ci, J.; Ren, X.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, L.; Yang, W. Identification and expression analysis revealed drought stress-responsive Calmodulin and Calmodulin-like genes in maize. J. Plant Interact. 2022, 17, 450–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrigos, M.; Deschamps, S.; Viel, A.; Lund, S.; Champeil, P.; Møller, J.V.; le Maire, M. Detection of Ca(2+)-binding proteins by electrophoretic migration in the presence of Ca2+ combined with 45Ca2+ overlay of protein blots. Anal. Biochem. 1991, 194, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Zhang, F.; Mu, C.; Ma, C.; Yao, G.; Sun, Y.; Hou, J.; Leng, B.; Liu, X. The ZmbHLH47-ZmSnRK2.9 Module Promotes Drought Tolerance in Maize. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batistič, O.; Kudla, J. Analysis of calcium signaling pathways in plants. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2012, 1820, 1283–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seleiman, M.F.; Al-Suhaibani, N.; Ali, N.; Akmal, M.; Alotaibi, M.; Refay, Y.; Dindaroglu, T.; Abdul-Wajid, H.H.; Battaglia, M.L. Drought Stress Impacts on Plants and Different Approaches to Alleviate Its Adverse Effects. Plants 2021, 10, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perochon, A.; Aldon, D.; Galaud, J.P.; Ranty, B. Calmodulin and calmodulin-like proteins in plant calcium signaling. Biochimie 2011, 93, 2048–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.Y.; Rocha, P.S.; Wang, M.L.; Xu, M.L.; Cui, Y.C.; Li, L.Y.; Zhu, Y.X.; Xia, X. A novel rice calmodulin-like gene, OsMSR2, enhances drought and salt tolerance and increases ABA sensitivity in Arabidopsis. Planta 2011, 234, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Dong, F.; Zou, J.; Gao, C.; Zhu, Z.; Liu, Y. Multiple roles of wheat calmodulin genes during stress treatment and TaCAM2-D as a positive regulator in response to drought and salt tolerance. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 220, 985–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.Z.; Zhang, J.L.; Tian, Q.Y.; Zhao, M.G.; Zhang, W.H. A Medicago truncatula EF-hand family gene, MtCaMP1, is involved in drought and salt stress tolerance. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e58952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, A.; Mittler, R.; Suzuki, N. ROS as key players in plant stress signalling. J. Exp. Bot. 2014, 65, 1229–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Q.; Cui, M.; Zhao, M.; Li, N.; Wang, S.; Wu, R.; Zhang, L.; Cao, Y.; et al. The interaction of ABA and ROS in plant growth and stress resistances. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1050132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierla, M.; Waszczak, C.; Vahisalu, T.; Kangasjärvi, J. Reactive oxygen species in the regulation of stomatal movements. Plant Physiol. 2016, 171, 1569–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, B.; Chen, N.; Song, L.; Wang, D.; Cai, H.; Yao, L.; Li, X.; Guo, C. Alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) MsCML46 gene encoding calmodulin-like protein confers tolerance to abiotic stress in tobacco. Plant Cell Rep. 2021, 40, 1907–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munir, S.; Liu, H.; Xing, Y.; Hussain, S.; Ouyang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Ye, Z. Overexpression of calmodulin-like (ShCML44) stress-responsive gene from Solanum habrochaites enhances tolerance to multiple abiotic stresses. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 31772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cutler, S.R.; Rodriguez, P.L.; Finkelstein, R.R.; Abrams, S.R. Abscisic acid: Emergence of a core signaling network. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2010, 61, 651–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delk, N.A.; Johnson, K.A.; Chowdhury, N.I.; Braam, J. CML24, regulated in expression by diverse stimuli, encodes a potential Ca2+ sensor that functions in responses to abscisic acid, daylength, and ion stress. Plant Physiol. 2005, 139, 240–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vadassery, J.; Reichelt, M.; Hause, B.; Gershenzon, J.; Boland, W.; Mithöfer, A. CML42-mediated calcium signaling coordinates responses to Spodoptera herbivory and abiotic stresses in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2012, 159, 1159–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Qian, Y.; Fang, Y.; Ji, Y.; Sheng, J.; Ge, C. Characteristics of SlCML39, a Tomato Calmodulin-like Gene, and Its Negative Role in High Temperature Tolerance of Arabidopsis thaliana during Germination and Seedling Growth. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Liu, M.; Wang, H.; Li, M.; Liu, X.; Zang, Z.; Jiang, L. ZmCaM2-1, a Calmodulin Gene, Negatively Regulates Drought Tolerance in Transgenic Arabidopsis Through the ABA-Independent Pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smart, R.E. Rapid estimates of relative water content. Plant Physiol. 1974, 53, 258–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draper, H.H.; Hadley, M. Malondialdehyde determination as index of lipid peroxidation. Methods Enzymol. 1990, 186, 421–431. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bates, L.S.; Waldren, R.P.; Teare, I.D. Rapid determination of free proline for water-stress studies. Plant Soil 1973, 39, 205–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannopolitis, C.N.; Ries, S.K. Superoxide dismutases: I. Occurrence in higher plants. Plant Physiol. 1977, 59, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maehly, A.C.; Chance, B. The assay of catalases and peroxidases. Methods Biochem. Anal. 1954, 1, 357–424. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, M.; Bao, P.; Wang, H.; Wu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Xing, X.; Yang, W.; Ren, X.; Ci, J.; Jiang, L.; et al. Zea Maize Calmodulin (ZmCaM2) Regulates Drought Tolerance in Corn Plants Through an Abscisic Acid-Dependent Signaling Pathway. Plants 2025, 14, 3656. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233656

Liu M, Bao P, Wang H, Wu Z, Wang Z, Xing X, Yang W, Ren X, Ci J, Jiang L, et al. Zea Maize Calmodulin (ZmCaM2) Regulates Drought Tolerance in Corn Plants Through an Abscisic Acid-Dependent Signaling Pathway. Plants. 2025; 14(23):3656. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233656

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Meiyi, Pengxiang Bao, Hanqiao Wang, Zhiqiang Wu, Zhen Wang, Xiangyu Xing, Wei Yang, Xuejiao Ren, Jiabin Ci, Liangyu Jiang, and et al. 2025. "Zea Maize Calmodulin (ZmCaM2) Regulates Drought Tolerance in Corn Plants Through an Abscisic Acid-Dependent Signaling Pathway" Plants 14, no. 23: 3656. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233656

APA StyleLiu, M., Bao, P., Wang, H., Wu, Z., Wang, Z., Xing, X., Yang, W., Ren, X., Ci, J., Jiang, L., & Zang, Z. (2025). Zea Maize Calmodulin (ZmCaM2) Regulates Drought Tolerance in Corn Plants Through an Abscisic Acid-Dependent Signaling Pathway. Plants, 14(23), 3656. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233656