The Effect of Sowing Date on the Biomass Production of Non-Traditional and Commonly Used Intercrops from the Brassicaceae Family

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Iivonen, S.; Kivijärvi, P.; Suojala-Ahlfors, T. Characteristics of Various Catch Crops in the Organic Vegetable Production in Northern Climate Conditions: Results from an On-Farm Study; Reports 165; University of Helsinki, Ruralia Institute: Helsinki, Finland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Bergkvist, G.; Ulén, B. Biomass production and phosphorus retention by catch crops on clayey soils in southern and central Sweden. Field Crops Res. 2015, 171, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talgre, L.; Lauringson, E.; Marke, A.; Lauk, R. Biomass production and nutrient binding of catch crops. Žemdirbystė 2011, 98, 251–258. [Google Scholar]

- Raiola, A.; Errico, A.; Petruk, G.; Monti, D.M.; Barone, A.; Rigano, M.M. Bioactive compounds in Brassicaceae vegetables with a role in the prevention of chronic diseases. Molecules 2018, 23, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Zamora, L.; Castillejo, N.; Artés-Hernández, F. Postharvest UV-B and UV-C radiation enhanced the biosynthesis of glucosinolates and isothiocyanates in Brassicaceae sprouts. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2021, 181, 111650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haramoto, E.R.; Gallandt, E.R. Brassica cover cropping for weed management: A review. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2004, 19, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojtahedi, H.; Santo, G.; Wilson, J.; Hang, A.N. Managing Meloidogyne chitwoodi on potato with rapeseed as green manure. Plant Dis. 1993, 77, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.; Morra, M.; Brown, P.; McCaffrey, J. Toxicity of allyl isothiocyanate-amended soil to Limonius californicus (Mann.) (Coleoptera: Elateridae) wireworms. J. Chem. Ecol. 1993, 19, 1033–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sukovata, L.; Jaworski, T.; Kolk, A. Efficacy of Brassica juncea granulated seed meal against Melolontha grubs. Ind. Crops Prod. 2015, 70, 260–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Niu, J.; Wang, W.; Huo, H.; Li, J.; Luo, L.; Cao, Y. p-Aromatic isothiocyanates: Synthesis and anti-plant pathogen activity. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2018, 88, 1252–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brant, V.; Pivec, J.; Fuksa, P.; Neckář, K.; Kocourková, D.; Venclová, V. Biomass and energy production of catch crops in areas with deficiency of precipitation during summer period in central Bohemia. Biomass Bioenergy 2011, 35, 1286–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peu, P.; Picard, S.; Diara, A.; Girault, R.; Béline, F.; Bridoux, G.; Dabert, P. Prediction of hydrogen sulphide production during anaerobic digestion of organic substrates. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 121, 419–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinuevo-Salces, B.; Fernández-Varela, R.; Uellendahl, H. Key factors influencing the potential of catch crops for methane production. Environ. Technol. 2014, 35, 1685–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Słomka, A.; Wójcik-Oliveira, K. Assessment of the biogas yield of white mustard (Sinapis alba) cultivated as intercrops. J. Ecol. Eng. 2021, 22, 67–72. [Google Scholar]

- Heuermann, D.; Gentsch, N.; Boy, J.; Schweneker, D.; Feuerstein, U.; Groß, J.; Bauer, B.; Guggenberger, G.; von Wirén, N. Interspecific competition among catch crops modifies vertical root biomass distribution and nitrate scavenging in soils. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 11531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gentsch, N.; Boy, J.; Kennedy Batalla, J.D.; Heuermann, D.; von Wirén, N.; Schweneker, D.; Feuerstein, U.; Groß, J.; Bauer, B.; Reinhold-Hurek, B.; et al. Catch crop diversity increases rhizosphere carbon input and soil microbial biomass. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2020, 56, 943–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samarappuli, D.; Zanetti, F.; Berzuini, S.; Berti, M.T. Crambe (Crambe abyssinica Hochst): A non-food oilseed crop with great potential—A review. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanders, M.J.; Berendonk, C.; Fritz, C.; Watson, C.; Wichern, F. Catch crops store more nitrogen below-ground when considering rhizodeposits. Plant Soil 2017, 417, 287–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawłowski, L.; Pawłowska, M.; Kwiatkowski, C.A.; Harasim, E. The role of agriculture in climate change mitigation—A Polish example. Energies 2021, 14, 3657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwiatkowski, C.A.; Pawłowska, M.; Harasim, E.; Pawłowski, L. Strategies of climate change mitigation in agriculture plant production—A critical review. Energies 2023, 16, 4225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brant, V.; Rychlá, A.; Holec, J.; Hamouz, P.; Jursík, M.; Fuksa, P.; Kazda, J.; Procházka, P.; Tyšer, L.; Zábranský, P.; et al. Brassica Intercrops; AK ČR: Prague, Czech Republic, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kolbe, H.; Meyer, D.; Dittrich, B.; Köhler, B.; Schmidtke, K.; Wunderlich, B.; Lux, G. Berichte aus dem Ökolandbau; Schriftenreihe, Heft 6; Sächsisches Landesamt für Umwelt, Landwirtschaft und Geologie: Dresden, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Brant, V.; Bečka, D.; Cihlář, P.; Fuksa, P.; Hakl, J.; Holec, J.; Chyba, J.; Jursík, M.; Kobzová, D.; Krček, V.; et al. Strip Tillage—Classical, Intensive and Modified, 1st ed.; Profi Press s.r.o.: Prague, Czech Republic, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gaweda, D. Yield and yield structure of spring barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) grown in monoculture after different stubble crops. Acta Agrobot. 2011, 64, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Smit, B.; Janssens, B.; Haagsma, W.; Hennen, W.; Adrados, J.; Kathage, J. Adoption of cover crops for climate change mitigation in the EU. In Publications Office of the European Union; Kathage, J., Perez Dominguez, I., Eds.; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2019; p. 77. [Google Scholar]

- Pawłowska, M.; Pawłowski, L.; Pawłowski, A.; Kwiatkowski, C.A.; Harasim, E. Role of intercrops in the absorption of CO2 emitted from the combustion of fossil fuels. Environ. Prot. Eng. 2021, 47, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björkman, T.; Lowry, C.; Shail, J.W., Jr.; Brainard, D.C.; Anderson, D.S.; Masiunas, J.B. Mustard cover crops for biomass production and weed suppression in the Great Lakes Region. Agron. J. 2015, 107, 1235–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawłowska, M.; Pawłowski, A.; Pawłowski, L.; Cel, W.; Wójcik-Oliveira, K.; Kwiatkowski, C.; Harasim, E.; Wang, L. Possibility of carbon dioxide sequestration by catch crops. Ecol. Chem. Eng. 2019, 26, 641–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entrup, L.N.; Oehmichen, J. Lehrbuch des Pflanzenbaues; Volume 2: Kulturpflanzen; Th. Mann: Gelsenkirchen, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Walter, H. Einführung in die Phytologie; Band II: Grundlagen des Pflanzenlebens; Eugen Ulmer: Stuttgart, Germany, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- De Baets, S.; Poesen, J.; Meersmans, J.; Serlet, L. Cover crops and their erosion-reducing effects during concentrated flow erosion. Catena 2011, 85, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vos, J.; van der Putten, P.E.L.; Hussein, M.H.; van Dam, A.M.; Leffelaar, A.P. Field observations on nitrogen catch crops II. Root length and root length distribution in relation to species and nitrogen supply. Plant Soil 1998, 201, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorup-Kristensen, K. Are differences in root growth of nitrogen catch crops important for their ability to reduce soil nitrate-N content, and how can this be measured? Plant Soil 2001, 228, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munkholm, L.J.; Hansen, E.M. Catch crop biomass production, nitrogen uptake and root development under different tillage systems. Soil Use Manag. 2012, 28, 517–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warembourg, F.R.; Paul, E.A. Seasonal transfers of assimilated 14C in grassland: Plant production and turnover, soil and plant respiration. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1977, 9, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kätterer, T.; Bolinder, M.A.; Andrén, O.; Kirchmann, H.; Menichetti, L. Roots contribute more to refractory soil organic matter than above-ground crop residues, as revealed by a long-term field experiment. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2011, 141, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smucker, A.J.M. Carbon utilization and losses by plant root systems. ASA Spec. Publ. 1984, 49, 27–46. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, H.M. Methods of studying root systems in the field. HortScience 1986, 21, 952–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

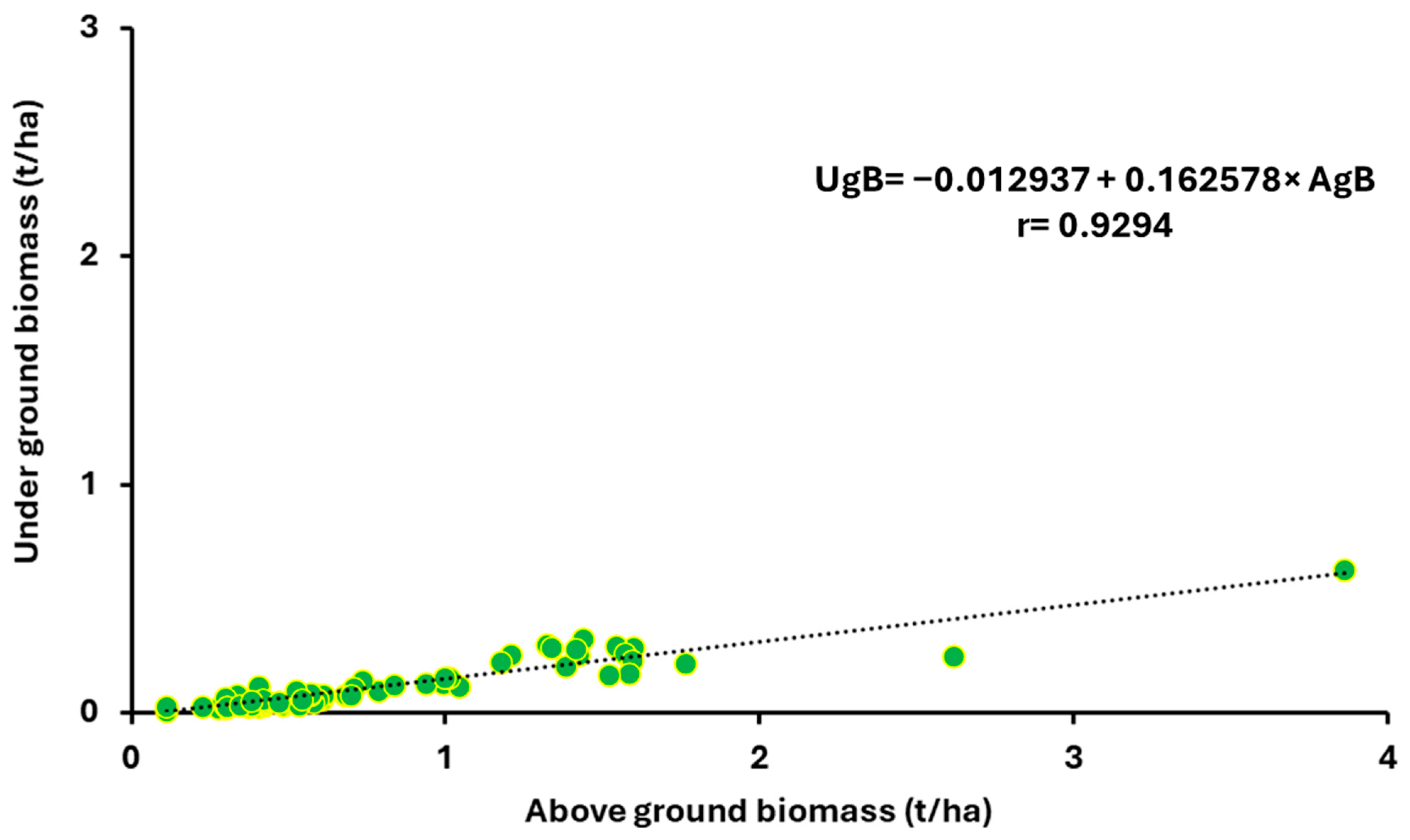

- Hu, T.; Sørensen, P.; Wahlström, E.M.; Chirinda, N.; Sharif, B.; Li, X.; Olesen, J.E. Root biomass in cereals, catch crops and weeds can be reliably estimated without considering aboveground biomass. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2018, 251, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MESAM. Measures Against Erosion and Sensibilisation of Farmers for the Protection of the Environment. Project Report on Cover Crops; European Interreg III Project; 2007; p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Kutschera, L.; Lichtenegger, E.; Sobotik, M. Wurzelatlas der Kulturpflanzen Gemäßigter Gebiete mit Arten des Feldgemüsebaues: 7. Band der Wurzelatlas Reihe; DLG-Verlag GmbH: Frankfurt, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, R.P.C. Soil Erosion and Conservation, 3rd ed.; Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

| 1. Sowing Date | 2. Sowing Date | 3. Sowing Date | 4. Sowing Date | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | Variety/New Breeding | UgB (t/ha) | AgB (t/ha) | UgB (t/ha) | AgB (t/ha) | UgB (t/ha) | AgB (t/ha) | UgB (t/ha) | AgB (t/ha) | ||||||||

| B. napus | Orion | 0.044 | abc | 0.374 | ab | 0.079 | a | 0.337 | a | 0.040 | ab | 0.289 | abcd | 0.057 | ab | 0.498 | ab |

| B. napus | Esexska | 0.055 | abcd | 0.503 | abc | 0.118 | a | 0.405 | a | 0.025 | a | 0.211 | ab | 0.078 | abc | 0.568 | ab |

| B. rapa | Saturn | 0.058 | abcd | 0.573 | bc | 0.258 | a | 1.208 | ab | 0.030 | a | 0.265 | abc | 0.084 | abc | 0.571 | ab |

| B. rapa | Kova | 0.047 | abc | 0.445 | ab | 0.290 | a | 1.595 | ab | 0.038 | a | 0.278 | abcd | 0.084 | abc | 0.707 | ab |

| S. alba | Paliisse | 0.129 | f | 0.977 | d | 0.294 | a | 1.544 | ab | 0.064 | ab | 0.506 | bcde | 0.131 | bc | 0.865 | b |

| S. alba | BGRC 34555 | 0.110 | ef | 1.006 | d | 0.329 | a | 1.437 | ab | 0.078 | ab | 0.591 | de | 0.144 | c | 0.733 | ab |

| B. nigra | Sizaja | 0.077 | cde | 0.591 | bc | 0.301 | a | 1.322 | ab | 0.067 | ab | 0.270 | abcd | 0.096 | abc | 0.522 | ab |

| B. nigra | N 2A94 | 0.057 | abcd | 0.596 | bc | 0.256 | a | 1.424 | ab | 0.028 | a | 0.204 | ab | 0.059 | abc | 0.419 | a |

| B. juncea | VNIIMK 12 | 0.076 | bcde | 0.602 | bc | 0.228 | a | 1.177 | ab | 0.039 | ab | 0.345 | abcd | 0.109 | abc | 0.707 | ab |

| C. sativa | Sortadinskij | 0.031 | a | 0.386 | ab | 0.266 | a | 1.570 | ab | 0.013 | a | 0.097 | a | 0.045 | ab | 0.406 | a |

| C. sativa | PRFGL. 59 | 0.035 | ab | 0.426 | ab | 0.154 | a | 1.012 | ab | 0.041 | ab | 0.106 | a | 0.039 | a | 0.613 | ab |

| R. sativus | Lucas | 0.129 | f | 0.924 | d | 0.631 | b | 3.861 | c | 0.135 | b | 1.122 | f | 0.284 | d | 1.412 | c |

| R. sativus | Siletta | 0.097 | def | 0.756 | cd | 0.230 | a | 1.591 | ab | 0.137 | b | 0.717 | e | 0.290 | d | 1.334 | c |

| C. abyssinica | Voronezhskii | 0.023 | a | 0.266 | a | 0.253 | a | 2.616 | bc | 0.060 | ab | 0.547 | cde | 0.055 | ab | 0.383 | a |

| C. abyssinica | BGRC 32855 | 0.041 | abc | 0.419 | ab | 0.176 | a | 1.583 | ab | 0.061 | ab | 0.510 | bcde | 0.062 | abc | 0.540 | ab |

| E. sativa | ERU 21/84 | 0.044 | abc | 0.400 | ab | 0.221 | a | 1.763 | ab | 0.041 | ab | 0.421 | abcde | 0.048 | ab | 0.470 | ab |

| E. sativa | BGRC 33984 | 0.030 | a | 0.366 | ab | 0.207 | a | 1.381 | ab | 0.030 | a | 0.296 | abcd | 0.079 | abc | 0.699 | ab |

| p-Value | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | |||||||||

| 1. Sowing Date | 2. Sowing Date | 3. Sowing Date | 4. Sowing Date | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | Variety/New Breeding | UgB (t/ha) | AgB (t/ha) | UgB (t/ha) | AgB (t/ha) | UgB (t/ha) | AgB (t/ha) | UgB (t/ha) | AgB (t/ha) | ||||||||

| B. napus | Orion | 1.956 | de | 8.129 | bcde | 0.595 | ab | 2.431 | a | * | * | 0.424 | a | 2.648 | a | ||

| B. napus | Esexska | 1.992 | de | 7.559 | abcde | 0.934 | abc | 3.044 | abc | 0.548 | abc | 3.552 | a | 0.863 | ab | 3.473 | ab |

| B. rapa | Saturn | 1.257 | abcd | 6.458 | abcd | 0.574 | ab | 2.594 | ab | 0.265 | a | 2.407 | a | 0.653 | a | 2.551 | a |

| B. rapa | Kova | 0.977 | abc | 4.834 | abc | 0.626 | ab | 2.957 | abc | 0.331 | ab | 2.261 | a | 0.922 | ab | 4.601 | ab |

| S. alba | Paliisse | 1.692 | cde | 10.308 | de | 1.148 | bc | 7.080 | cd | 0.587 | abc | 5.330 | abc | 1.251 | abc | 6.042 | b |

| S. alba | BGRC 34555 | 1.249 | abcd | 7.926 | bcde | 1.023 | abc | 6.857 | bcd | 0.451 | ab | 4.669 | ab | 0.685 | a | 3.255 | ab |

| B. nigra | Sizaja | 1.161 | abcd | 7.799 | bcde | 0.819 | ab | 4.865 | abcd | 0.722 | abcd | 6.054 | abc | 1.097 | ab | 4.795 | ab |

| B. nigra | N 2A94 | 1.486 | bcde | 8.535 | bcde | 0.918 | ab | 6.061 | abcd | 0.483 | abc | 4.841 | abc | 0.483 | a | 2.731 | a |

| B. juncea | VNIIMK 12 | 2.310 | e | 11.853 | e | 0.989 | abc | 6.830 | bcd | 0.304 | ab | 3.136 | a | 1.010 | ab | 3.961 | ab |

| C. sativa | Sortadinskij | 0.463 | a | 3.040 | a | 0.813 | ab | 5.390 | abcd | 0.184 | a | 0.932 | a | 0.357 | a | 2.364 | a |

| C. sativa | PRFGL. 59 | 0.745 | ab | 4.133 | abc | 0.438 | a | 3.427 | abc | 0.278 | ab | 2.436 | a | 1.060 | ab | 3.581 | ab |

| R. sativus | Lucas | 1.751 | cde | 8.866 | cde | 1.562 | c | 8.928 | d | 1.246 | d | 9.614 | bc | 2.100 | c | 3.189 | ab |

| R. sativus | Siletta | 1.510 | bcde | 8.253 | bcde | 0.782 | ab | 5.805 | abcd | 0.562 | abc | 5.859 | abc | 1.685 | bc | 4.248 | ab |

| C. abyssinica | Voronezhskii | 0.898 | abc | 5.288 | abc | 0.651 | ab | 5.988 | abcd | 1.063 | cd | 9.601 | bc | 0.535 | a | 4.420 | ab |

| C. abyssinica | BGRC 32855 | 0.911 | abc | 7.026 | abcd | 0.526 | a | 5.373 | abcd | 0.940 | bcd | 10.089 | c | 0.358 | a | 2.647 | a |

| E. sativa | ERU 21/84 | 0.783 | ab | 5.056 | abc | 0.747 | ab | 6.015 | abcd | 0.494 | abc | 4.361 | a | 0.565 | a | 4.270 | ab |

| E. sativa | BGRC 33984 | 0.665 | ab | 4.510 | abc | 0.583 | ab | 5.196 | abcd | 0.454 | ab | 5.936 | abc | 0.454 | a | 2.783 | a |

| p-Value | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0001 | |||||||||

| Ratio of Aboveground and Underground Biomass (AgB/UgB) | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | Variety/New Breeding | BBCH 17–19 | BBCH 63–67 | ||||||||||||||

| 1. Sowing Date | 2. Sowing Date | 3. Sowing Date | 4. Sowing Date | 1. Sowing Date | 2. Sowing Date | 3. Sowing Date | 4. Sowing Date | ||||||||||

| B. napus | Orion | 9.5 | a | 4.8 | ab | 8.7 | ab | 8.9 | abcd | 4.3 | ab | 5.6 | abc | 6.0 | abcde | ||

| B. napus | Esexska | 10.3 | ab | 3.7 | a | 8.2 | a | 8.1 | abc | 3.8 | a | 5.7 | abc | 10.8 | ab | 4.1 | ab |

| B. rapa | Saturn | 11.6 | ab | 4.6 | ab | 12.9 | ab | 8.5 | abcd | 5.5 | abc | 4.6 | a | 9.3 | ab | 4.4 | ab |

| B. rapa | Kova | 10.3 | ab | 6.3 | abcd | 10.1 | ab | 10.3 | bcd | 5.5 | abc | 5.3 | ab | 8.4 | a | 5.0 | abc |

| S. alba | Paliisse | 8.8 | a | 5.2 | abc | 8.5 | a | 7.3 | abc | 6.2 | bc | 6.1 | abc | 10.8 | ab | 5.1 | abc |

| S. alba | BGRC 34555 | 10.1 | ab | 5.6 | abc | 8.3 | a | 5.8 | a | 7.1 | cd | 6.6 | abcd | 11.5 | ab | 5.6 | abcd |

| B. nigra | Sizaja | 8.5 | a | 5.1 | ab | 8.8 | ab | 8.7 | abcd | 7.2 | cd | 6.4 | abc | 8.1 | a | 4.8 | abc |

| B. nigra | N 2A94 | 15.0 | b | 5.6 | abc | 8.9 | ab | 8.9 | abcd | 6.1 | abc | 6.8 | abcd | 10.1 | ab | 5.8 | abcde |

| B. juncea | VNIIMK 12 | 8.9 | a | 5.2 | abc | 10.2 | ab | 9.4 | abcd | 6.0 | abc | 6.9 | bcd | 14.0 | ab | 4.2 | ab |

| C. sativa | Sortadinskij | 15.2 | b | 7.2 | bcde | 8.7 | ab | 11.3 | cd | 6.7 | cd | 6.0 | abc | 8.0 | a | 6.7 | bcde |

| C. sativa | PRFGL. 59 | 14.9 | b | 7.9 | cde | 13.8 | ab | 20.1 | e | 5.9 | abc | 7.0 | bcd | 9.5 | ab | 6.0 | abcde |

| R. sativus | Lucas | 8.0 | a | 6.0 | abc | 12.4 | ab | 6.0 | a | 5.3 | abc | 5.8 | abc | 12.6 | ab | 3.7 | a |

| R. sativus | Siletta | 8.6 | a | 7.1 | bcde | 15.2 | b | 6.2 | ab | 5.7 | abc | 7.3 | bcd | 14.8 | b | 5.0 | abc |

| C. abyssinica | Voronezhskii | 11.5 | ab | 9.2 | d | 11.0 | ab | 9.3 | abcd | 6.8 | cd | 9.7 | e | 9.1 | ab | 8.2 | de |

| C. abyssinica | BGRC 32855 | 11.0 | ab | 8.8 | cde | 11.3 | ab | 12.4 | d | 9.0 | d | 10.1 | e | 13.3 | ab | 8.7 | e |

| E. sativa | ERU 21/84 | 10.2 | ab | 7.0 | bcde | 10.8 | ab | 10.6 | cd | 6.8 | cd | 7.9 | cde | 10.3 | ab | 7.6 | cde |

| E. sativa | BGRC 33984 | 12.9 | ab | 6.1 | abc | 10.8 | ab | 8.6 | abcd | 7.5 | cd | 8.9 | de | 13.7 | ab | 6.0 | abcde |

| p-Value | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0041 | 0.000 | |||||||||

| Species | Variety/New Breeding | 1. Sowing Date | 2. Sowing Date | 3. Sowing Date | 4. Sowing Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of Leaf Biomass (%) in the Total Aboveground Biomass of the Crop | |||||

| B. napus | Orion | 41.6 | 81.8 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| B. napus | Esexska | 46.2 | 84.7 | 94.9 | 100.0 |

| B. rapa | Saturn | 24.4 | 20.7 | 51.8 | 68.9 |

| B. rapa | Kova | 33.8 | 22.5 | 55.0 | 88.2 |

| S. alba | Paliisse | 30.1 | 30.7 | 51.9 | 53.3 |

| S. alba | BGRC 34555 | 23.4 | 28.8 | 45.2 | 64.5 |

| B. nigra | Sizaja | 29.0 | 29.4 | 42.1 | 75.0 |

| B. nigra | N 2A94 | 32.1 | 36.0 | 46.4 | 81.0 |

| B. juncea | VNIIMK 12 | 31.5 | 28.9 | 55.5 | 86.6 |

| C. sativa | Sortadinskij | 36.0 | 38.1 | 47.1 | 67.9 |

| C. sativa | PRFGL. 59 | 41.3 | 47.1 | 38.4 | 85.8 |

| R. sativus | Lucas | 44.8 | 44.5 | 52.2 | 100.0 |

| R. sativus | Siletta | 45.2 | 40.9 | 26.8 | 98.1 |

| C. abyssinica | Voronezhskii | 43.5 | 59.0 | 60.3 | 90.4 |

| C. abyssinica | BGRC 32855 | 43.0 | 62.5 | 60.3 | 89.1 |

| E. sativa | ERU 21/84 | 37.6 | 50.0 | 76.2 | 83.6 |

| E. sativa | BGRC 33984 | 37.1 | 38.3 | 67.9 | 78.5 |

| Species | Variety/New Breeding | 1. Sowing Date | 2. Sowing Date | 3. Sowing Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B. napus | Orion | 113 | * | * |

| B. napus | Esexska | 113 | * | * |

| B. rapa | Saturn | 91 | 52 | 84 |

| B. rapa | Kova | 91 | 52 | 84 |

| S. alba | Paliisse | 94 | 54 | 87 |

| S. alba | BGRC 34555 | 94 | 54 | 87 |

| B. nigra | Sizaja | 94 | 54 | 85 |

| B. nigra | N 2A94 | 94 | 54 | 85 |

| B. juncea | VNIIMK 12 | 94 | 54 | 85 |

| C. sativa | Sortadinskij | 94 | 56 | 84 |

| C. sativa | PRFGL. 59 | 91 | 56 | 84 |

| R. sativus | Lucas | 100 | 66 | 84 |

| R. sativus | Siletta | 100 | 58 | 84 |

| C. abyssinica | Voronezhskii | 100 | 62 | 84 |

| C. abyssinica | BGRC 32855 | 100 | 62 | 84 |

| E. sativa | ERU 21/84 | 95 | 59 | 87 |

| E. sativa | BGRC 33984 | 95 | 59 | 87 |

| Species | Variety/New Breeding * | Sowing Rate (Seeds pre m2) |

|---|---|---|

| B. napus L. subsp. napus | Orion, Esexska | 89 |

| B. rapa L. subsp. oleifera (DC.) Mentzger | Saturn, Kova | 178 |

| S. alba L. | Paliisse, BGRC 34555 * | 89 |

| B. nigra (L.) Koch | Sizaja, N 2A94 * | 148 |

| B. juncea (L.) Czern. et Cosson | VNIIMK 12 * | 148 |

| C. sativa (L.) Crantz | Sortadinskij, PRFGL. 59 * | 178 |

| R. sativus L. oleiformis | Lucas, Siletta | 89 |

| C. abyssinica Hochst. ex R.E.Fries | Voronezhskii, BGRC 32855 * | 148 |

| E. sativa (L.) Mill. | ERU 21/84 *, BGRC 33984 * | 178 |

| No. | Date in 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sowing Date | Biomass Assessment Date | Sowing Date | Biomass Assessment Date | Sowing Date | Biomass Assessment Date | ||||

| BBCH * 17–19/No of Days After Sowing | BBCH 63–67/No of Days After Sowing | BBCH 17–19/No of Days After Sowing | BBCH 63–67/No of Days After Sowing | BBCH 17–19/No of Days After Sowing | BBCH 63–67/No of Days After Sowing | ||||

| 1. | 29.3. | 20.5./52 | 4.6./67 | 23.9. | 10.5./48 | 6.6./78 | 27.3. | 9.5./43 | 29.5./63 |

| 2. | 26.5. | 28.6./31 | 8.7./43 | 18.5. | 13.6./29 | 27.6./43 | 11.5. | 12.6./32 | 4.7./54 |

| 3. | 28.6. | 27.7./31 | 2.9./68 | 27.6. | 20.7./23 | 30.8./64 | 4.7. | 20.7./16 | 10.8./37 |

| 4. | 6.9. | 4.10./25 | 9.11/59 | 3.9. | 17.10./44 | 8.11./66 | 5.9. | 17.10./42 | 8.11./64 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brant, V.; Rychlá, A.; Hamouzová, K.; Vrbovský, V.; Procházka, P.; Chára, J.; Holejšovský, J.; Piskáčková, T.; Bhattacharya, S.; Dreksler, J. The Effect of Sowing Date on the Biomass Production of Non-Traditional and Commonly Used Intercrops from the Brassicaceae Family. Plants 2025, 14, 3654. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233654

Brant V, Rychlá A, Hamouzová K, Vrbovský V, Procházka P, Chára J, Holejšovský J, Piskáčková T, Bhattacharya S, Dreksler J. The Effect of Sowing Date on the Biomass Production of Non-Traditional and Commonly Used Intercrops from the Brassicaceae Family. Plants. 2025; 14(23):3654. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233654

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrant, Václav, Andrea Rychlá, Kateřina Hamouzová, Viktor Vrbovský, Pavel Procházka, Josef Chára, Jiří Holejšovský, Theresa Piskáčková, Soham Bhattacharya, and Jiří Dreksler. 2025. "The Effect of Sowing Date on the Biomass Production of Non-Traditional and Commonly Used Intercrops from the Brassicaceae Family" Plants 14, no. 23: 3654. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233654

APA StyleBrant, V., Rychlá, A., Hamouzová, K., Vrbovský, V., Procházka, P., Chára, J., Holejšovský, J., Piskáčková, T., Bhattacharya, S., & Dreksler, J. (2025). The Effect of Sowing Date on the Biomass Production of Non-Traditional and Commonly Used Intercrops from the Brassicaceae Family. Plants, 14(23), 3654. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233654