Trends in Inhibitors, Structural Modifications, and Structure–Function Relationships of Phosphodiesterase 4: A Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

“Unlike previous reviews, this work provides a comprehensive and focused analysis of natural PDE4 inhibitors, a particularly relevant and emerging area in the search for safer and more selective PDE4-targeted therapies. In addition, it systematically integrates the structural differences among PDE4 isoforms, which represent one of the most promising strategies for achieving isoform selectivity. This analysis is presented within a complete overview of PDE4 biology, including its enzymatic function, structural organization, and involvement in inflammatory diseases, thereby offering a unified perspective that bridges natural product chemistry and structure-guided isoform-selective inhibitor design.”

2. Inflammation

2.1. Basic Principles

2.2. Anti-Inflammatory Agents

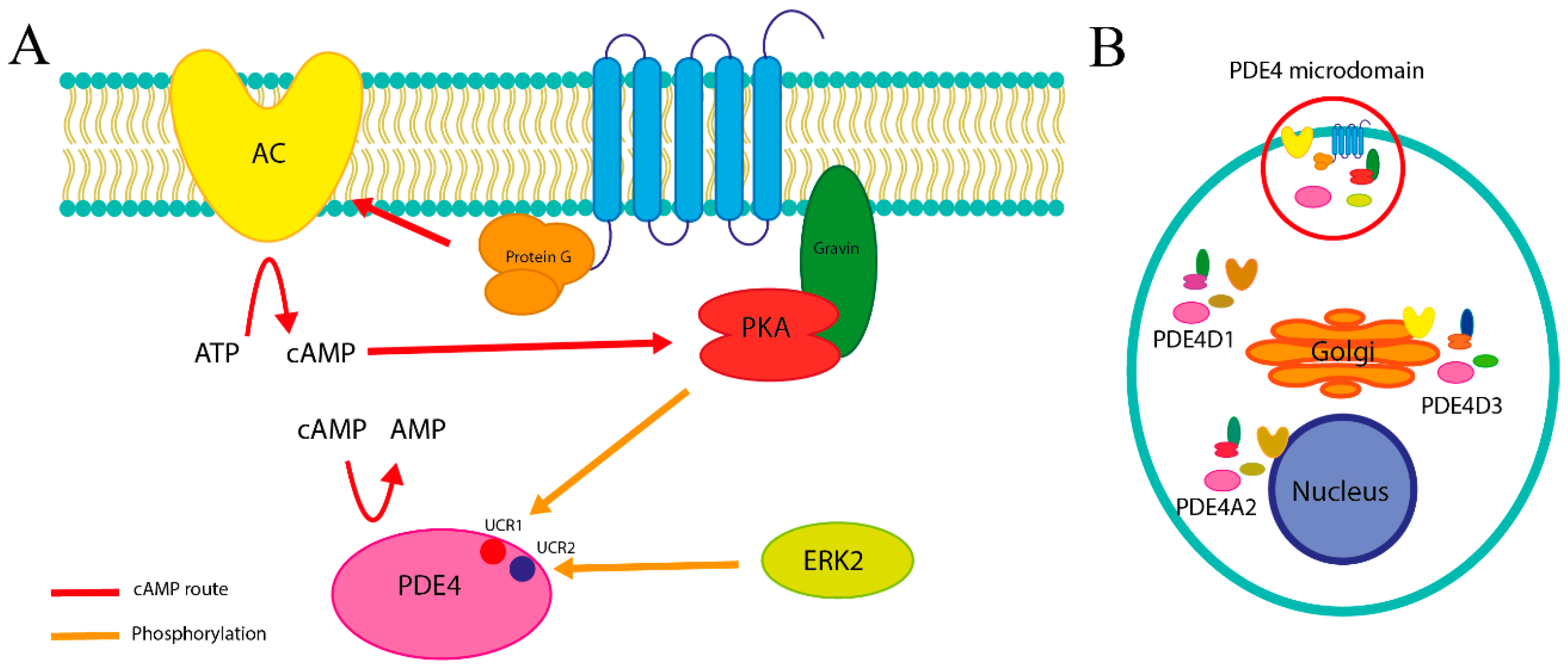

3. Phosphodiesterase 4

3.1. Enzymatic Role

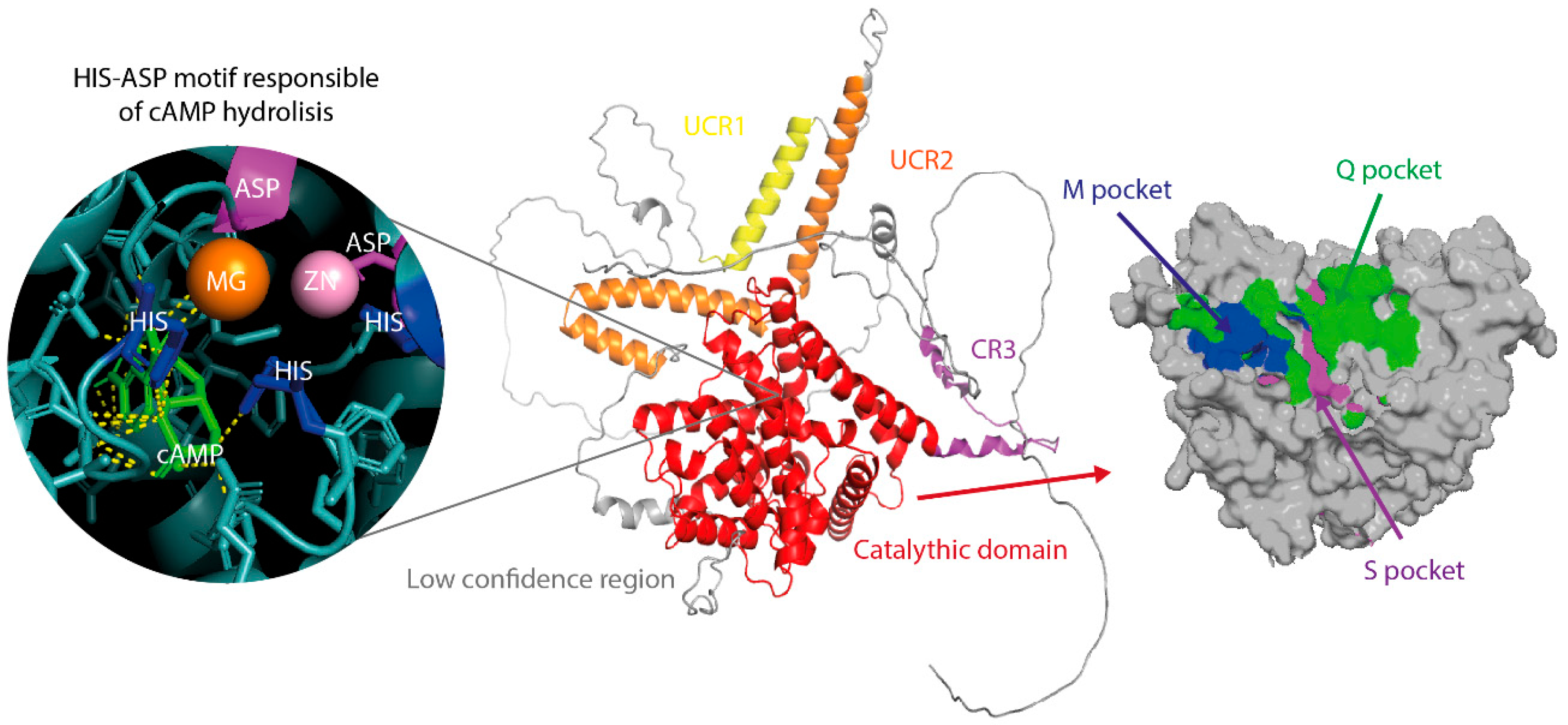

3.2. Structure of Pde4

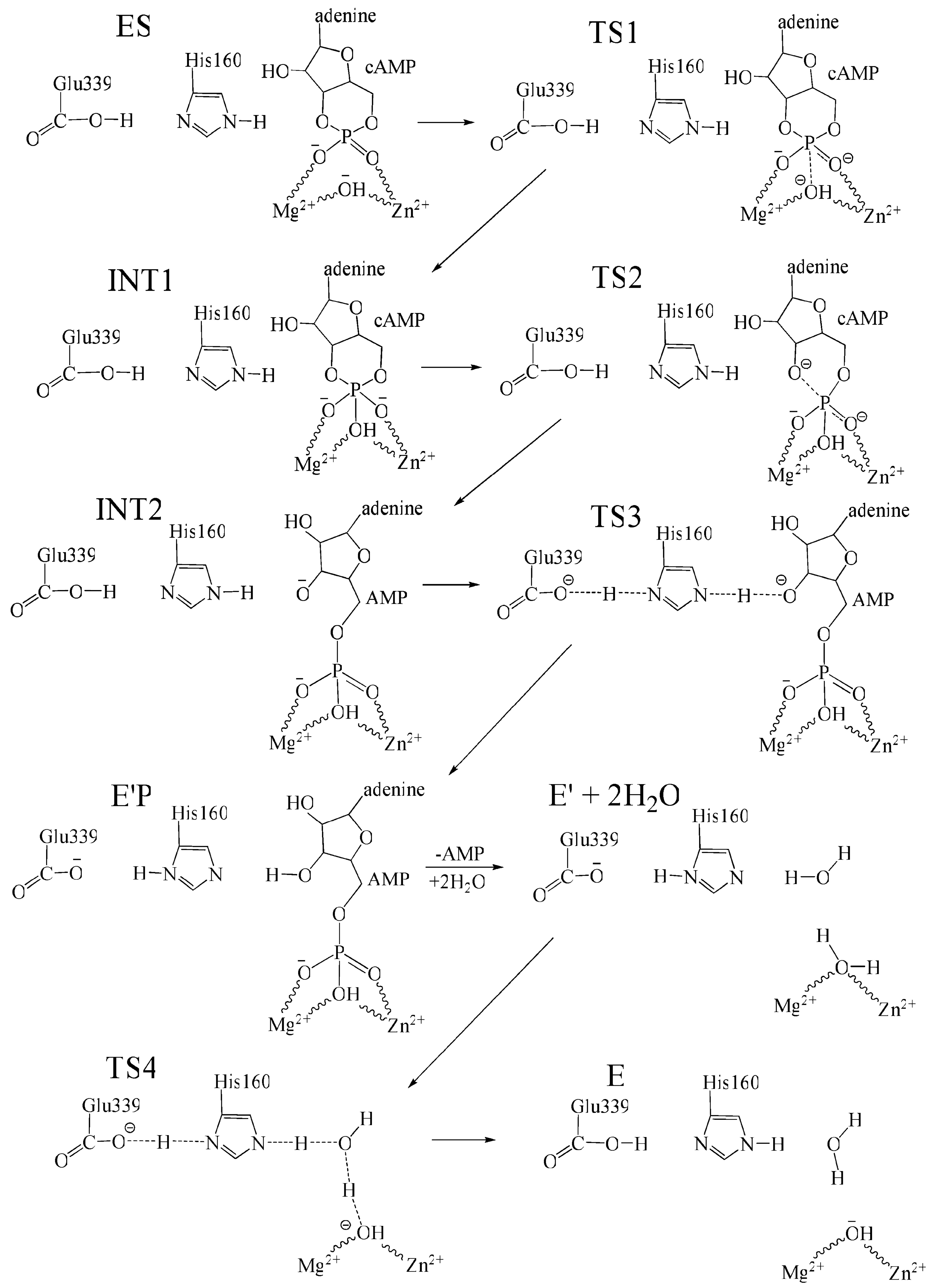

3.3. Catalytic Function

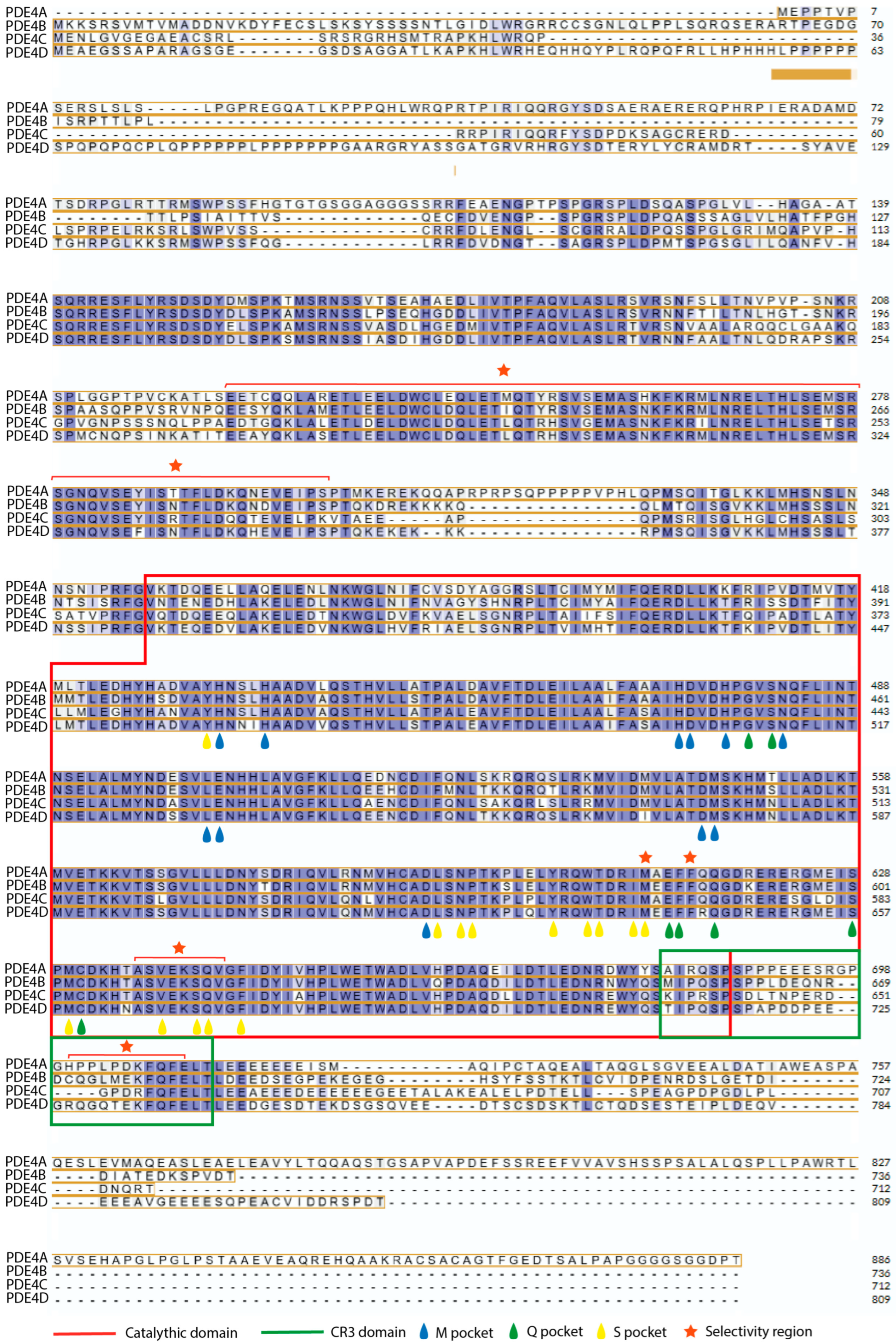

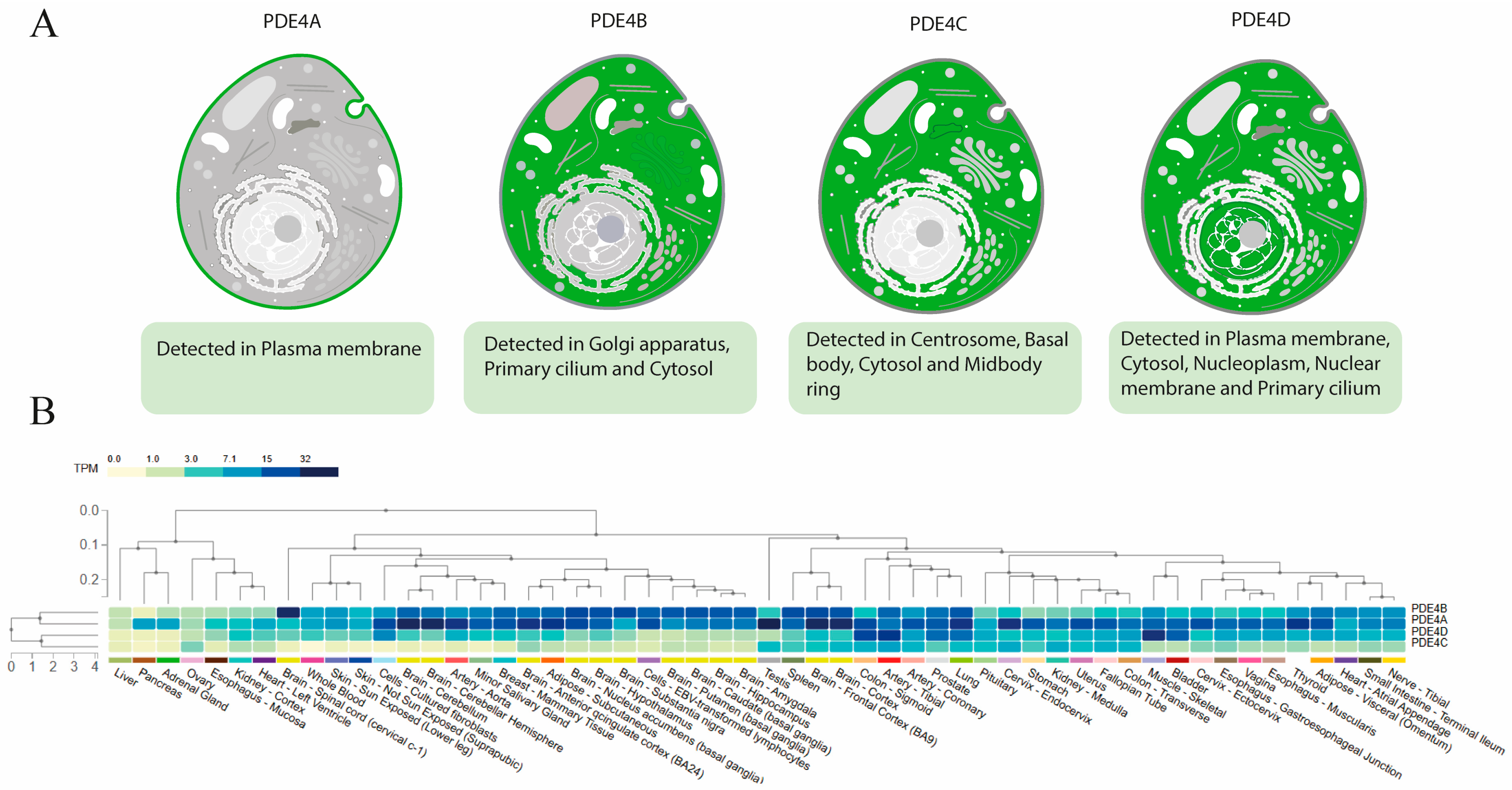

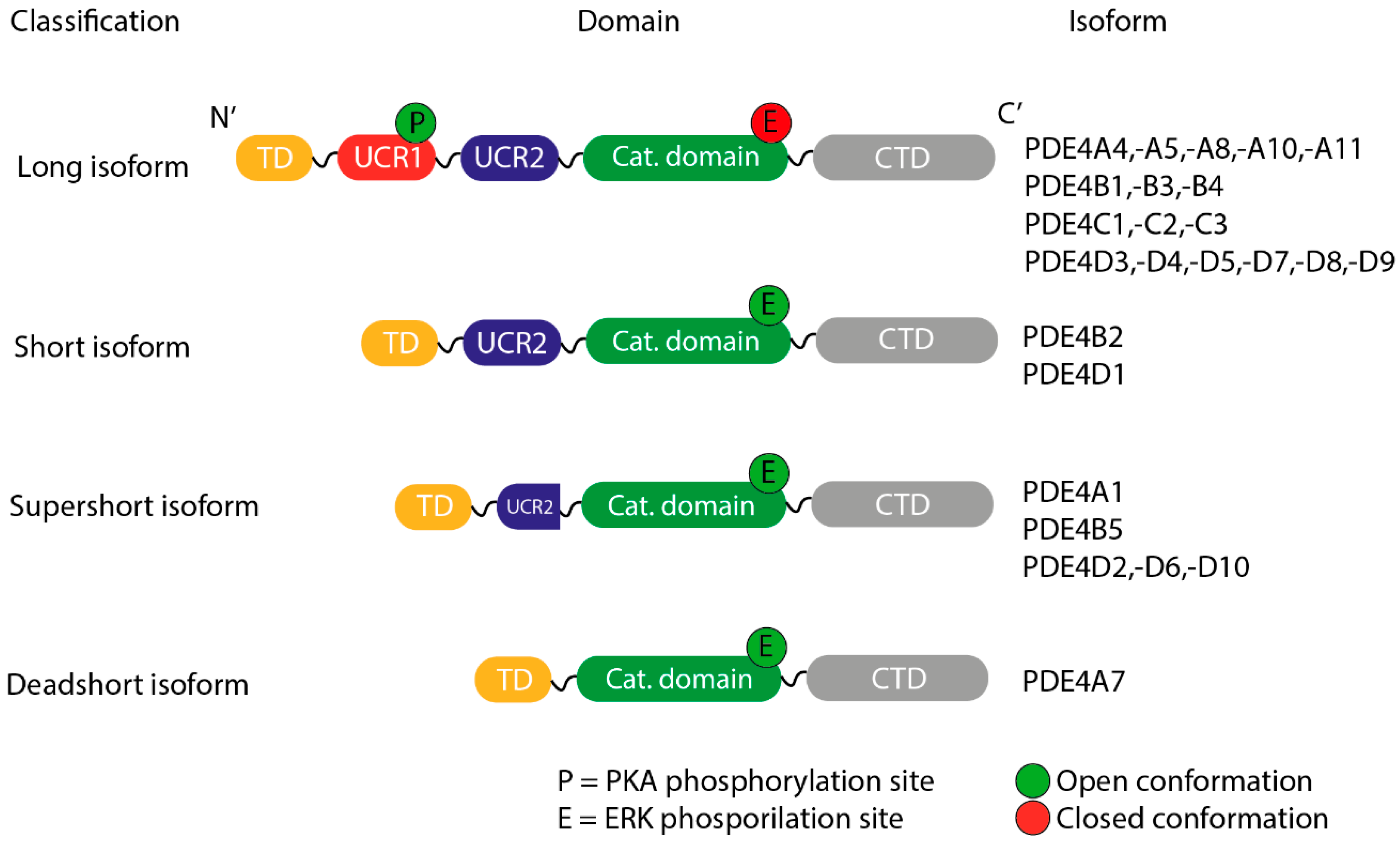

3.4. Differences Between Isoforms

- Long, containing both UCR1 and UCR2.

- Short, containing only UCR2.

- Super-short, featuring a truncated version of UCR2.

- Ultra-short (dead-short), which completely lacks these regions.

4. Natural Bioactives as Pde4 Inhibitors

4.1. Approved Inhibitors

4.2. Natural Compounds with Inhibition

| Name | Structure | Taxonomy | Plant | IC50 | Conditions | Isoform | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

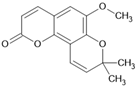

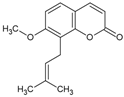

| Braylin |  | Coumarin | Hypericum sampsonii | 1.27 μM | Radiometric assay | PDE4D | [91] |

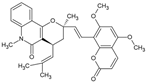

| Toddacoumalone |  | Coumarin | Toddalia asiatica | 0.14 μM | Radiometric assay | PDE4D | [92,93] |

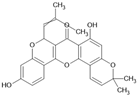

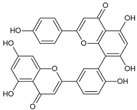

| Cyclomorusin |  | Flavonoid | Morus alba | 0.0054 μM | Radiometric assay | PDE4D | [94] |

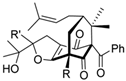

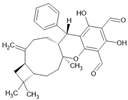

| Polycyclic polyprenylated acylphloroglucinols |  | Terpenoid | Hypericum sampsonii | 0.64 μM | Radiometric assay | PDE4D | [95] |

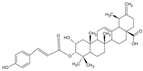

| Pentacyclic triterpene G1 |  | Terpenoid | Gaultheria yunnanensis | 0.245 μM | Radiometric assay | PDE4D | [85] |

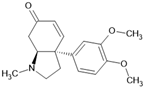

| Alkaloid mesembrenone |  | Alkaloid | Sceletium tortuosum | 0.47 μM | Radiometric assay | PDE4B | [89] |

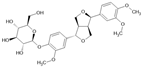

| Forsythin |  | Lignan | Forsythia suspensa | 1.8 μM | Fluorescence-based KIT | PDE4D | [96] |

| Psidial A |  | Terpenoid | Psidium guajava | 1.6 μM | Radiometric assay | PDE4D | [97] |

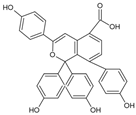

| Selagintamarlin A |  | Phenolic compound | Selaginella tamariscina | 0.049 μM | TR-FRET | PDE4D | [98] |

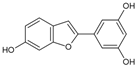

| Moracin M |  | Phenolic compound | Morus alba | 2.9 μM | Radiometric assay | PDE4D | [88] |

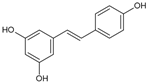

| Resveratrol |  | Phenolic compound | Vitis vinifera | 18.8 μM | Radiometric assay | PDE4D | [99,100] |

| Amentoflavone |  | Flavonoid | Platycladus orientalis | * 74.2% at 0.2 µg/mL | Radiometric assay | PDE4D | [101] |

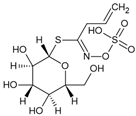

| Sinigrin |  | Glucosinolatos | Brassica | Nd | Nd | Nd | [102] |

| Osthol |  | Coumarin | Angelica hirsutiflora | 7.81 nM | Oxidative stress in activated neutrophils | Nd | [103] |

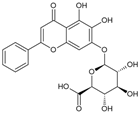

| Baicalin |  | Flavonoid | Pourthiaea villosa | 4.8 μM | TR-FRET | PDE4B | [87] |

| Curcumin |  | Polifenol | Curcuma longa | 19.82 μM | Radiometric assay | Nd | [104] |

| Dioclein |  | Flavonoid | Dioclea grandiflora | 16.8 μM | Radiometric assay | Nd | [105] |

| Millesianins |  | Flavonoid | Millettia dielsiana | 6.56 μM | Fluorescence-based KIT | PDE4B | [90] |

4.3. Rational Design Based on Natural Inhibitors

4.4. Future Perspectives

5. Conclusions and Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Gregersen, P.K.; Behrens, T.W. Genetics of Autoimmune Diseases—Disorders of Immune Homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2006, 7, 917–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucia Appleton, S.; Navarro-Orcajada, S.; Martínez-Navarro, F.J.; Caldera, F.; López-Nicolás, J.M.; Trotta, F.; Matencio, A. Cyclodextrins as Anti-Inflammatory Agents: Basis, Drugs and Perspectives. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulkhaleq, L.A.; Assi, M.A.; Abdullah, R.; Zamri-Saad, M.; Taufiq-Yap, Y.H.; Hezmee, M.N.M. The Crucial Roles of Inflammatory Mediators in Inflammation: A Review. Vet. World 2018, 11, 627–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Hong, Y.; Huang, H. Triptolide Attenuates Inflammatory Response in Membranous Glomerulo-Nephritis Rat via Downregulation of NF-κB Signaling Pathway. Kidney Blood Press. Res. 2016, 41, 901–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ks, V.; Akkewar, A.S.; Murtikumar, M.N.; Sethi, K.K. PDE4B Inhibition: Exploring the Landscape of Chemistry Behind Specific PDE4B Inhibitors, Drug Design, and Discovery. Arch. Pharm. 2025, 358, e70030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schick, M.A.; Schlegel, N. Clinical Implication of Phosphodiesterase-4-Inhibition. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatzelmann, A.; Schudt, C. Anti-Inflammatory and Immunomodulatory Potential of the Novel PDE4 Inhibitor Roflumilast in Vitro. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2001, 297, 267–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, Y.; Lu, H.-T.; Li, Y.; Yang, G.-F.; Zhan, C.-G. Characterization of a Catalytic Ligand Bridging Metal Ions in Phosphodiesterases 4 and 5 by Molecular Dynamics Simulations and Hybrid Quantum Mechanical/Molecular Mechanical Calculations. Biophys. J. 2006, 91, 1858–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, P.W.; Vaidya, S.A.; Cheng, G. The Art of War: Innate and Adaptive Immune Responses. CMLS Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2003, 60, 2604–2621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid-Schönbein, G.W. Analysis of inflammation. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2006, 8, 93–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medzhitov, R. Origin and Physiological Roles of Inflammation. Nature 2008, 454, 428–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Gómez, A.; Perretti, M.; Soehnlein, O. Resolution of Inflammation: An Integrated View. EMBO Mol. Med. 2013, 5, 661–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chovatiya, R.; Medzhitov, R. Stress, Inflammation, and Defense of Homeostasis. Mol. Cell 2014, 54, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.T. When Two Is Better than One: Macrophages and Neutrophils Work in Concert in Innate Immunity as Complementary and Cooperative Partners of a Myeloid Phagocyte System. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2010, 87, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Xu, J.; Lazarovici, P.; Quirion, R.; Zheng, W. cAMP Response Element-Binding Protein (CREB): A Possible Signaling Molecule Link in the Pathophysiology of Schizophrenia. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2018, 11, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, O.; Rajagopal, L. Phosphodiesterase Inhibitors for Alzheimer’s Disease: A Systematic Review of Clinical Trials and Epidemiology with a Mechanistic Rationale. J. Alzheimers Dis. Rep. 2020, 4, 185–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Shi, F. Phosphodiesterase 4 and Compartmentalization of Cyclic AMP Signaling. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2007, 52, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schafer, P.H.; Truzzi, F.; Parton, A.; Wu, L.; Kosek, J.; Zhang, L.-H.; Horan, G.; Saltari, A.; Quadri, M.; Lotti, R.; et al. Phosphodiesterase 4 in Inflammatory Diseases: Effects of Apremilast in Psoriatic Blood and in Dermal Myofibroblasts through the PDE4/CD271 Complex. Cell. Signal. 2016, 28, 753–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgazzar, A.H.; Elmonayeri, M. Inflammation. In The Pathophysiologic Basis of Nuclear Medicine; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 69–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serhan, C.N.; Levy, B.D. Resolvins in Inflammation: Emergence of the pro-Resolving Superfamily of Mediators. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 128, 2657–2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serhan, C.N. Pro-Resolving Lipid Mediators Are Leads for Resolution Physiology. Nature 2014, 510, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abudukelimu, A.; Barberis, M.; Redegeld, F.A.; Sahin, N.; Westerhoff, H.V. Predictable Irreversible Switching Between Acute and Chronic Inflammation. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, J.B.; White, A.G.; Scarpati, L.M.; Wan, G.; Nelson, W.W. Long-Term Systemic Corticosteroid Exposure: A Systematic Literature Review. Clin. Ther. 2017, 39, 2216–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claman, H.N. Corticosteroids as Immunomodulators. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1993, 685, 288–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakkas, L.I.; Mavropoulos, A.; Bogdanos, D.P. Phosphodiesterase 4 Inhibitors in Immune-Mediated Diseases: Mode of Action, Clinical Applications, Current and Future Perspectives. Curr. Med. Chem. 2017, 24, 3054–3067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamatawong, T. Roles of Roflumilast, a Selective Phosphodiesterase 4 Inhibitor, in Airway Diseases. J. Thorac. Dis. 2017, 9, 1144–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Zhai, J.; Liu, H.; Liu, H.; Sun, B.; Gao, J.; Sang, F. Phosphodiesterase 4B (PDE4B) Inhibitors and Their Applications in Recent Years (2014 to Early 2025). Mol. Divers. 2025, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, D.M.F. Compartmentalization of Adenylate Cyclase and cAMP Signalling. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2005, 33, 1319–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willoughby, D.; Wong, W.; Schaack, J.; Scott, J.D.; Cooper, D.M.F. An Anchored PKA and PDE4 Complex Regulates Subplasmalemmal cAMP Dynamics. EMBO J. 2006, 25, 2051–2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, W.; Scott, J.D. AKAP Signalling Complexes: Focal Points in Space and Time. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004, 5, 959–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taskén, K.; Aandahl, E.M. Localized Effects of cAMP Mediated by Distinct Routes of Protein Kinase A. Physiol. Rev. 2004, 84, 137–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, M.; Richter, W.; Mehats, C.; Livera, G.; Park, J.-Y.; Jin, C. Cyclic AMP-Specific PDE4 Phosphodiesterases as Critical Components of Cyclic AMP Signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 5493–5496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houslay, M.D.; Milligan, G. Tailoring cAMP-Signalling Responses through Isoform Multiplicity. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1997, 22, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, R.; Wilkinson, I.R.; McCallum, J.F.; Engels, P.; Houslay, M.D. cAMP-Specific Phosphodiesterase HSPDE4D3 Mutants Which Mimic Activation and Changes in Rolipram Inhibition Triggered by Protein Kinase A Phosphorylation of Ser-54: Generation of a Molecular Model. Biochem. J. 1998, 333, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; Pahlke, G.; Conti, M. Activation of the cAMP-Specific Phosphodiesterase PDE4D3 by Phosphorylation. Identification and Function of an Inhibitory Domain. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 19677–19685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oki, N.; Takahashi, S.I.; Hidaka, H.; Conti, M. Short Term Feedback Regulation of cAMP in FRTL-5 Thyroid Cells. Role of PDE4D3 Phosphodiesterase Activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 10831–10837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, S.L.; Richard, F.J.; Kuo, W.P.; D’Ercole, A.J.; Conti, M. Impaired Growth and Fertility of cAMP-Specific Phosphodiesterase PDE4D-Deficient Mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 11998–12003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, D.; Burgin, A.B.; Gurney, M.E. Structural Basis for the Design of Selective Phosphodiesterase 4B Inhibitors. Cell. Signal. 2014, 26, 657–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, H. Implications of PDE4 Structure on Inhibitor Selectivity across PDE Families. Int. J. Impot. Res. 2004, 16, S24–S27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paes, D.; Schepers, M.; Rombaut, B.; van den Hove, D.; Vanmierlo, T.; Prickaerts, J. The Molecular Biology of Phosphodiesterase 4 Enzymes as Pharmacological Targets: An Interplay of Isoforms, Conformational States, and Inhibitors. Pharmacol. Rev. 2021, 73, 1016–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houslay, M.D.; Adams, D.R. Putting the Lid on Phosphodiesterase 4. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010, 28, 38–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houslay, M.D.; Baillie, G.S.; Maurice, D.H. cAMP-Specific Phosphodiesterase-4 Enzymes in the Cardiovascular System: A Molecular Toolbox for Generating Compartmentalized cAMP Signaling. Circ. Res. 2007, 100, 950–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.X.; Hassell, A.M.; Vanderwall, D.; Lambert, M.H.; Holmes, W.D.; Luther, M.A.; Rocque, W.J.; Milburn, M.V.; Zhao, Y.D.; Ke, H.M.; et al. Atomic Structure of PDE4: Insights into Phosphodiesterase Mechanism and Specificity. Science 2000, 288, 1822–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwak, H.J.; Nam, K.H. Molecular Properties of Phosphodiesterase 4 and Its Inhibition by Roflumilast and Cilomilast. Molecules 2025, 30, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Card, G.L.; England, B.P.; Suzuki, Y.; Fong, D.; Powell, B.; Lee, B.; Luu, C.; Tabrizizad, M.; Gillette, S.; Ibrahim, P.N.; et al. Structural Basis for the Activity of Drugs That Inhibit Phosphodiesterases. Structure 2004, 12, 2233–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.Y.J.; Card, G.L.; Suzuki, Y.; Artis, D.R.; Fong, D.; Gillette, S.; Hsieh, D.; Neiman, J.; West, B.L.; Zhang, C.; et al. A Glutamine Switch Mechanism for Nucleotide Selectivity by Phosphodiesterases. Mol. Cell 2004, 15, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhao, X.; Xiong, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhan, C.-G. Fundamental Reaction Pathway and Free Energy Profile for Hydrolysis of Intracellular Second Messenger Adenosine 3′,5′-Cyclic Monophosphate (cAMP) Catalyzed by Phosphodiesterase-4. J. Phys. Chem. B 2011, 115, 12208–12219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, N.S.; Chae, C.H.; Yoo, S.-E. Study on the Hydrolysis Mechanism of Phosphodiesterase 4 Using Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Mol. Simul. 2006, 32, 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paes, D.; Hermans, S.; van den Hove, D.; Vanmierlo, T.; Prickaerts, J.; Carlier, A. Computational Investigation of the Dynamic Control of cAMP Signaling by PDE4 Isoform Types. Biophys. J. 2022, 121, 2693–2711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamontagne, S.; Meadows, E.; Luk, P.; Normandin, D.; Muise, E.; Boulet, L.; Pon, D.J.; Robichaud, A.; Robertson, G.S.; Metters, K.M.; et al. Localization of Phosphodiesterase-4 Isoforms in the Medulla and Nodose Ganglion of the Squirrel monkey. Brain Res. 2001, 920, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thul, P.J.; Åkesson, L.; Wiking, M.; Mahdessian, D.; Geladaki, A.; Ait Blal, H.; Alm, T.; Asplund, A.; Björk, L.; Breckels, L.M.; et al. A Subcellular Map of the Human Proteome. Science 2017, 356, eaal3321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguet, F.; Barbeira, A.N.; Bonazzola, R.; Jo, B.; Kasela, S.; Liang, Y.; Parsana, P.; Aguet, F.; Battle, A.; Brown, A.; et al. GTEx Consortium the GTEx Consortium Atlas of Genetic Regulatory Effects across Human Tissues. Science 2020, 369, 1318–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.-L.C.; Lan, L.; Zoudilova, M.; Conti, M. Specific Role of Phosphodiesterase 4B in Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Signaling in Mouse Macrophages1. J. Immunol. 2005, 175, 1523–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Peng, M.-S.; Chen, Y.; Geng, J.; Robinson, H.; Houslay, M.D.; Cai, J.; Ke, H. Structures of the Four Subfamilies of Phosphodiesterase-4 Provide Insight into the Selectivity of Their Inhibitors. Biochem. J. 2007, 408, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RICHTER, W.; JIN, S.-L.C.; CONTI, M. Splice Variants of the Cyclic Nucleotide Phosphodiesterase PDE4D Are Differentially Expressed and Regulated in Rat Tissue. Biochem. J. 2005, 388, 803–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsien Lai, S.; Zervoudakis, G.; Chou, J.; Gurney, M.E.; Quesnelle, K.M. PDE4 Subtypes in Cancer. Oncogene 2020, 39, 3791–3802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Torres, S.; Miró, X.; Palacios, J.M.; Cortés, R.; Puigdoménech, P.; Mengod, G. Phosphodiesterase Type 4 Isozymes Expression in Human Brain Examined by in Situ Hybridization Histochemistry and [3H]Rolipram Binding Autoradiography. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 2000, 20, 349–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Wu, P.; Ohleth, K.M.; Egan, R.W.; Billah, M.M. Phosphodiesterase 4B2 Is the Predominant Phosphodiesterase Species and Undergoes Differential Regulation of Gene Expression in Human Monocytes and Neutrophils. Mol. Pharmacol. 1999, 56, 170–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyurkchieva, E.; Baillie, G.S. Short PDE4 Isoforms as Drug Targets in Disease. Front. Biosci. 2023, 28, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Némoz, G.; Zhang, R.; Sette, C.; Conti, M. Identification of Cyclic AMP-Phosphodiesterase Variants from the PDE4D Gene Expressed in Human Peripheral Mononuclear Cells. FEBS Lett. 1996, 384, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beard, M.B.; Olsen, A.E.; Jones, R.E.; Erdogan, S.; Houslay, M.D.; Bolger, G.B. UCR1 and UCR2 Domains Unique to the cAMP-Specific Phosphodiesterase Family Form a Discrete Module via Electrostatic Interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 10349–10358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houslay, M.D. Underpinning Compartmentalised cAMP Signalling through Targeted cAMP Breakdown. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2010, 35, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, S.J.; Baillie, G.S.; McPhee, I.; Bolger, G.B.; Houslay, M.D. ERK2 Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Binding, Phosphorylation, and Regulation of the PDE4D cAMP-Specific Phosphodiesterases. The Involvement of COOH-Terminal Docking Sites and NH2-Terminal UCR Regions. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 16609–16617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolger, G.B.; Dunlop, A.J.; Meng, D.; Day, J.P.; Klussmann, E.; Baillie, G.S.; Adams, D.R.; Houslay, M.D. Dimerization of cAMP Phosphodiesterase-4 (PDE4) in Living Cells Requires Interfaces Located in Both the UCR1 and Catalytic Unit Domains. Cell. Signal. 2015, 27, 756–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, R.; Baillie, G.S.; MacKenzie, S.J.; Yarwood, S.J.; Houslay, M.D. The MAP Kinase ERK2 Inhibits the Cyclic AMP-Specific Phosphodiesterase HSPDE4D3 by Phosphorylating It at Ser579. EMBO J. 1999, 18, 893–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranz, M.; Wall, M.; Evans, B.; Miah, A.; Ballantine, S.; Delves, C.; Dombroski, B.; Gross, J.; Schneck, J.; Villa, J.P.; et al. Identification of PDE4B Over 4D Subtype-Selective Inhibitors Revealing an Unprecedented Binding Mode. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2009, 17, 5336–5341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgin, A.B.; Magnusson, O.T.; Singh, J.; Witte, P.; Staker, B.L.; Bjornsson, J.M.; Thorsteinsdottir, M.; Hrafnsdottir, S.; Hagen, T.; Kiselyov, A.S.; et al. Design of Phosphodiesterase 4D (PDE4D) Allosteric Modulators for Enhancing Cognition with Improved Safety. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010, 28, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutcliffe, J.S.; Beaumont, V.; Watson, J.M.; Chew, C.S.; Beconi, M.; Hutcheson, D.M.; Dominguez, C.; Munoz-Sanjuan, I. Efficacy of Selective PDE4D Negative Allosteric Modulators in the Object Retrieval Task in Female Cynomolgus Monkeys (Macaca Fascicularis). PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e102449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madeira, F.; Madhusoodanan, N.; Lee, J.; Eusebi, A.; Niewielska, A.; Tivey, A.R.N.; Lopez, R.; Butcher, S. The EMBL-EBI Job Dispatcher Sequence Analysis Tools Framework in 2024. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, W521–W525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spina, D. PDE4 Inhibitors: Current Status. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2008, 155, 308–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matera, M.G.; Page, C.; Cazzola, M. PDE Inhibitors Currently in Early Clinical Trials for the Treatment of Asthma. Expert. Opin. Investig. Drugs 2014, 23, 1267–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urbanova, A.; Medvedova, I.; Kertys, M.; Mikolka, P.; Kosutova, P.; Mokra, D.; Mokrý, J. Dose Dependent Effects of Tadalafil and Roflumilast on Ovalbumin-Induced Airway Hyperresponsiveness in Guinea Pigs. Exp. Lung Res. 2017, 43, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocetti, L.; Floresta, G.; Cilibrizzi, A.; Giovannoni, M.P. An Overview of PDE4 Inhibitors in Clinical Trials: 2010 to Early 2022. Molecules 2022, 27, 4964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asfaw, A.A. Use and Comparative Safety of Roflumilast in Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Illinois Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, P.; Patel, S.; Patel, Y.; Chudasama, P.; Soni, S.; Patel, S.; Raval, M. Roflumilast Mitigates Cisplatin-Induced Nephrotoxicity by Regulating TNF-α/TNFR1/TNFR2/Fas/Caspase Mediated Apoptosis and Inflammatory Signals. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2025, 77, 308–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, H.J.; Song, J.S.; No, Z.S.; Song, J.H.; Yang, S.D.; Cheon, H.G. The Inhibitory Effects of Roflumilast on Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Nitric Oxide Production in RAW264.7 Cells Are Mediated by Heme Oxygenase-1 and Its Product Carbon Monoxide. Inflamm. Res. 2005, 54, 508–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martina, S.D.; Ismail, M.S.; Vesta, K.S. Cilomilast: Orally Active Selective Phosphodiesterase-4 Inhibitor for Treatment of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Ann. Pharmacother. 2006, 40, 1822–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gooderham, M.; Papp, K. Selective Phosphodiesterase Inhibitors for Psoriasis: Focus on Apremilast. BioDrugs 2015, 29, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paller, A.S.; Hong, Y.; Becker, E.M.; de Lucas, R.; Paris, M.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Z.; Barcellona, C.; Maes, P.; Fiorillo, L. Pharmacokinetics and Safety of Apremilast in Pediatric Patients with Moderate to Severe Plaque Psoriasis: Results from a Phase 2 Open-Label Study. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2020, 82, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honma, M.; Hayashi, K. Psoriasis: Recent Progress in Molecular-Targeted Therapies. J. Dermatol. 2021, 48, 761–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kailas, A. Crisaborole: A New and Effective Nonsteroidal Topical Drug for Atopic Dermatitis. Dermatol. Ther. 2017, 30, e12533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zane, L.; Chanda, S.; Jarnagin, K.; Nelson, D.; Spelman, L.; Gold, L.S. Crisaborole and Its Potential Role in Treating Atopic Dermatitis: Overview of Early Clinical Studies. Immunotherapy 2016, 8, 853–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, S.; Mehta, G. Natural Products as Modulators of the Cyclic-AMP Pathway: Evaluation and Synthesis of Lead Compounds. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2018, 16, 6372–6390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Chen, S.-K.; Cai, Y.-H.; Lu, X.; Li, Z.; Cheng, Y.-K.; Zhang, C.; Hu, X.; He, X.; Luo, H.-B. The Molecular Basis for the Inhibition of Phosphodiesterase-4D by Three Natural Resveratrol Analogs. Isolation, Molecular Docking, Molecular Dynamics Simulations, Binding Free Energy, and Bioassay. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Proteins Proteom. 2013, 1834, 2089–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Y.-H.; Guo, Y.; Li, Z.; Wu, D.; Li, X.; Zhang, H.; Yang, J.; Lu, H.; Sun, Z.; Luo, H.-B.; et al. Discovery and Modelling Studies of Natural Ingredients from Gaultheria yunnanensis (FRANCH.) against Phosphodiesterase-4. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 114, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gangwal, R.P.; Damre, M.V.; Das, N.R.; Dhoke, G.V.; Bhadauriya, A.; Varikoti, R.A.; Sharma, S.S.; Sangamwar, A.T. Structure Based Virtual Screening to Identify Selective Phosphodiesterase 4B Inhibitors. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2015, 57, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.; Lee, J.S.; Choi, J.S.; Nam, Y.-J.; Han, J.-H.; Byun, H.-D.; Song, M.-J.; Oh, J.-S.; Kim, S.G.; Choi, Y. Identification and Characterization of Baicalin as a Phosphodiesterase 4 Inhibitor. Phytother. Res. 2016, 30, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-K.; Zhao, P.; Shao, Y.-X.; Li, Z.; Zhang, C.; Liu, P.; He, X.; Luo, H.-B.; Hu, X. Moracin M from Morus alba L. Is a Natural Phosphodiesterase-4 Inhibitor. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 22, 3261–3264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harvey, A.L.; Young, L.C.; Viljoen, A.M.; Gericke, N.P. Pharmacological Actions of the South African Medicinal and Functional Food Plant Sceletium tortuosum and Its Principal Alkaloids. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011, 137, 1124–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, V.T.T.; Hung, H.V.; Ha, N.X.; Le, C.H.; Minh, P.T.H.; Lam, D.T. Natural Phosphodiesterase-4 Inhibitors with Potential Anti-Inflammatory Activities from Millettia Dielsiana. Molecules 2023, 28, 7253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Tang, G.-H.; Guo, F.-L.; Li, W.; Zhang, J.-S.; Liu, B.; Yin, S. (P)/(M)-Corinepalensin A, a Pair of Axially Chiral Prenylated Bicoumarin Enantiomers with a Rare C-5 C-5′ Linkage from the Twigs of Coriaria Nepalensis. Phytochemistry 2018, 149, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, K.-Q.; Chen, X.-P.; Huang, Y.; Chan, A.S.C.; Luo, H.-B.; Xiong, X.-F. Asymmetric Total Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of the Natural PDE4 Inhibitor Toddacoumalone. Org. Lett. 2020, 22, 584–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhang, J.-S.; Huang, J.-L.; Jiang, M.-H.; Xu, Y.-K.; Ahmed, A.; Yin, S.; Tang, G.-H. New Prenylated Coumarins from the Stems of Toddalia Asiatica. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 31061–31068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.-Q.; Tang, G.-H.; Lou, L.-L.; Li, W.; Zhang, B.; Liu, B.; Yin, S. Prenylated Flavonoids as Potent Phosphodiesterase-4 Inhibitors from Morus alba: Isolation, Modification, and Structure-Activity Relationship Study. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 144, 758–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.-S.; Zou, Y.-H.; Guo, Y.-Q.; Li, Z.-Z.; Tang, G.-H.; Yin, S. Polycyclic Polyprenylated Acylphloroglucinols: Natural Phosphodiesterase-4 Inhibitors from Hypericum Sampsonii. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 53469–53476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coon, T.A.; McKelvey, A.C.; Weathington, N.M.; Birru, R.L.; Lear, T.; Leikauf, G.D.; Chen, B.B. Novel PDE4 Inhibitors Derived from Chinese Medicine Forsythia. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e115937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G.-H.; Dong, Z.; Guo, Y.-Q.; Cheng, Z.-B.; Zhou, C.-J.; Yin, S. Psiguajadials A-K: Unusual Psidium Meroterpenoids as Phosphodiesterase-4 Inhibitors from the Leaves of Psidium Guajava. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, W.-N.; Huang, R.-Z.; Hua, J.; Zhang, B.; Wang, C.-G.; Liang, D.; Wang, H.-S. Selagintamarlin A: A Selaginellin Analogue Possessing a 1H-2-Benzopyran Core from Selaginella tamariscina. ACS Omega 2017, 2, 2178–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Li, W.; Li, Y.; Xu, W.; Yuan, Y.; Zheng, V.; Zhang, H.; O’Donnell, J.M.; Xu, Y.; Yin, X. The Antidepressant- and Anxiolytic-like Effects of Resveratrol: Involvement of Phosphodiesterase-4D Inhibition. Neuropharmacology 2019, 153, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Wang, J.; Huang, X. The Anti-Depressant Effects of a Novel PDE4 Inhibitor Derived from Resveratrol. Pharm. Biol. 2021, 59, 416–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Sun, L.; Wu, L.; Wang, X.; Chen, L.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Gu, W.; Shi, D.; Liu, W.; et al. Platycladus orientalis (L.) Franco Demonstrates Effective Anti-Psoriasis Effects by Inhibiting PDE4 with Favorable Safety Profiles. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2025, 36, 110795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, S.; Liu, W.; Lu, Y.; Yan, M.; Guo, Y.; Chang, N.; Jiang, M.; Bai, G. Sinigrin Enhanced Antiasthmatic Effects of Beta Adrenergic Receptors Agonists by Regulating cAMP-Mediated Pathways. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, Y.-F.; Yu, H.-P.; Chung, P.-J.; Leu, Y.-L.; Kuo, L.-M.; Chen, C.-Y.; Hwang, T.-L. Osthol Attenuates Neutrophilic Oxidative Stress and Hemorrhagic Shock-Induced Lung Injury via Inhibition of Phosphodiesterase 4. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015, 89, 387–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Zhu, Y.; Huang, X. Design and Synthesis of Novel Curcumin Derivatives as Potent PDE4 Inhibitors for the Treatment of Depression. J. Chem. Res. 2024, 48, 17475198241304588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guabiraba, R.; Campanha-Rodrigues, A.L.; Souza, A.L.S.; Santiago, H.C.; Lugnier, C.; Alvarez-Leite, J.; Lemos, V.S.; Teixeira, M.M. The Flavonoid Dioclein Reduces the Production of Pro-Inflammatory Mediators in Vitro by Inhibiting PDE4 Activity and Scavenging Reactive Oxygen Species. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2010, 633, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Huang, Y.-Y.; Zhou, Q.; Gao, Y.; Li, Z.; Wu, D.; Yu, S.; Guo, L.; Chen, Z.; Huang, L.; et al. Discovery and Optimization of α-Mangostin Derivatives as Novel PDE4 Inhibitors for the Treatment of Vascular Dementia. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 3370–3380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurney, M.E.; Burgin, A.B.; Magnusson, O.T.; Stewart, L.J. Small Molecule Allosteric Modulators of Phosphodiesterase 4. In Phosphodiesterases as Drug Targets; Francis, S.H., Conti, M., Houslay, M.D., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 167–192. ISBN 978-3-642-17969-3. [Google Scholar]

- Sin, Y.Y.; Giblin, A.; Judina, A.; Rujirachaivej, P.; Corral, L.G.; Glennon, E.; Tai, Z.X.; Feng, T.; Torres, E.; Zorn, A.; et al. Targeted Protein Degradation of PDE4 Shortforms by a Novel Proteolysis Targeting Chimera. FEBS J. 2025, 292, 3360–3377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansen, C.; Kooistra, A.J.; Kanev, G.K.; Leurs, R.; de Esch, I.J.P.; de Graaf, C. PDEStrIAn: A Phosphodiesterase Structure and Ligand Interaction Annotated Database as a Tool for Structure-Based Drug Design. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 7029–7065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sánchez-Belmonte, A.; Matencio, A.; Conesa, I.; Vidal-Sánchez, F.J.; Trotta, F.; López-Nicolás, J.M. Trends in Inhibitors, Structural Modifications, and Structure–Function Relationships of Phosphodiesterase 4: A Review. Biomolecules 2026, 16, 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010079

Sánchez-Belmonte A, Matencio A, Conesa I, Vidal-Sánchez FJ, Trotta F, López-Nicolás JM. Trends in Inhibitors, Structural Modifications, and Structure–Function Relationships of Phosphodiesterase 4: A Review. Biomolecules. 2026; 16(1):79. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010079

Chicago/Turabian StyleSánchez-Belmonte, Antonio, Adrián Matencio, Irene Conesa, Francisco José Vidal-Sánchez, Francesco Trotta, and José Manuel López-Nicolás. 2026. "Trends in Inhibitors, Structural Modifications, and Structure–Function Relationships of Phosphodiesterase 4: A Review" Biomolecules 16, no. 1: 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010079

APA StyleSánchez-Belmonte, A., Matencio, A., Conesa, I., Vidal-Sánchez, F. J., Trotta, F., & López-Nicolás, J. M. (2026). Trends in Inhibitors, Structural Modifications, and Structure–Function Relationships of Phosphodiesterase 4: A Review. Biomolecules, 16(1), 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010079