Effect of Sulfated Polysaccharides and Laponite in Composite Porous Scaffolds on Osteogenesis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Fabrication of the 3D Scaffolds

2.3. Physicochemical Characterization of the Scaffolds

2.3.1. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

2.3.2. X-Ray Diffraction Analysis (XRD)

2.3.3. Surface Morphology and Elemental Composition of the Scaffolds

2.3.4. Water Uptake Measurements

2.3.5. In Vitro Degradation Testing

2.3.6. Ion Release Study

2.3.7. Density and Porosity

2.3.8. Mechanical Characterization of the Scaffolds

2.4. In Vitro Biological Characterization of the Scaffolds

2.4.1. Cell Culture and Cell Viability Evaluation

2.4.2. SEM Imaging

2.4.3. Measurement of the Alkaline Phosphatase Activity

2.4.4. Assessment of Calcium Concentration Levels

2.4.5. Determination of Secreted Collagen

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

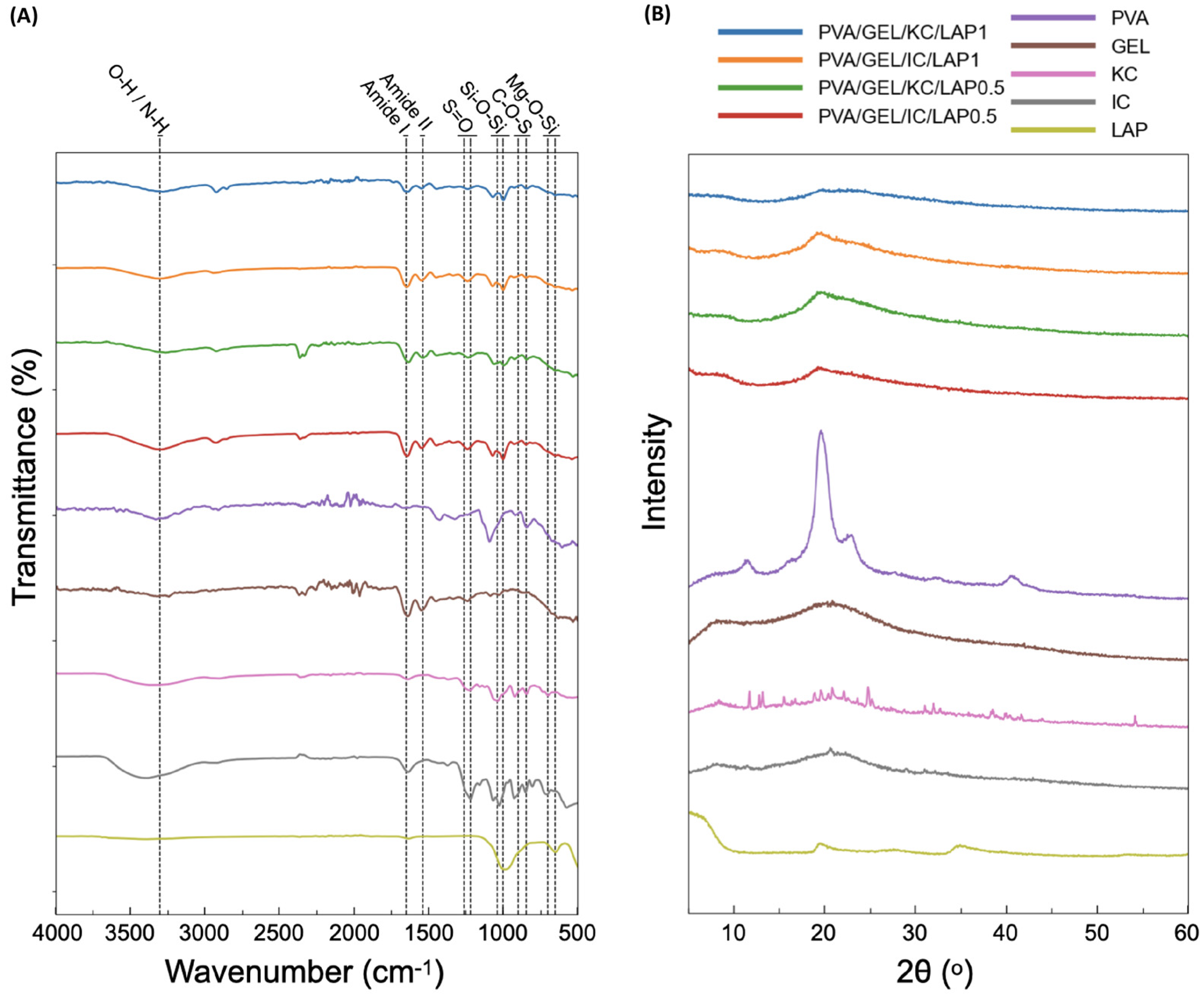

3.1. FTIR Characterization

3.2. X-Ray Diffraction Analysis

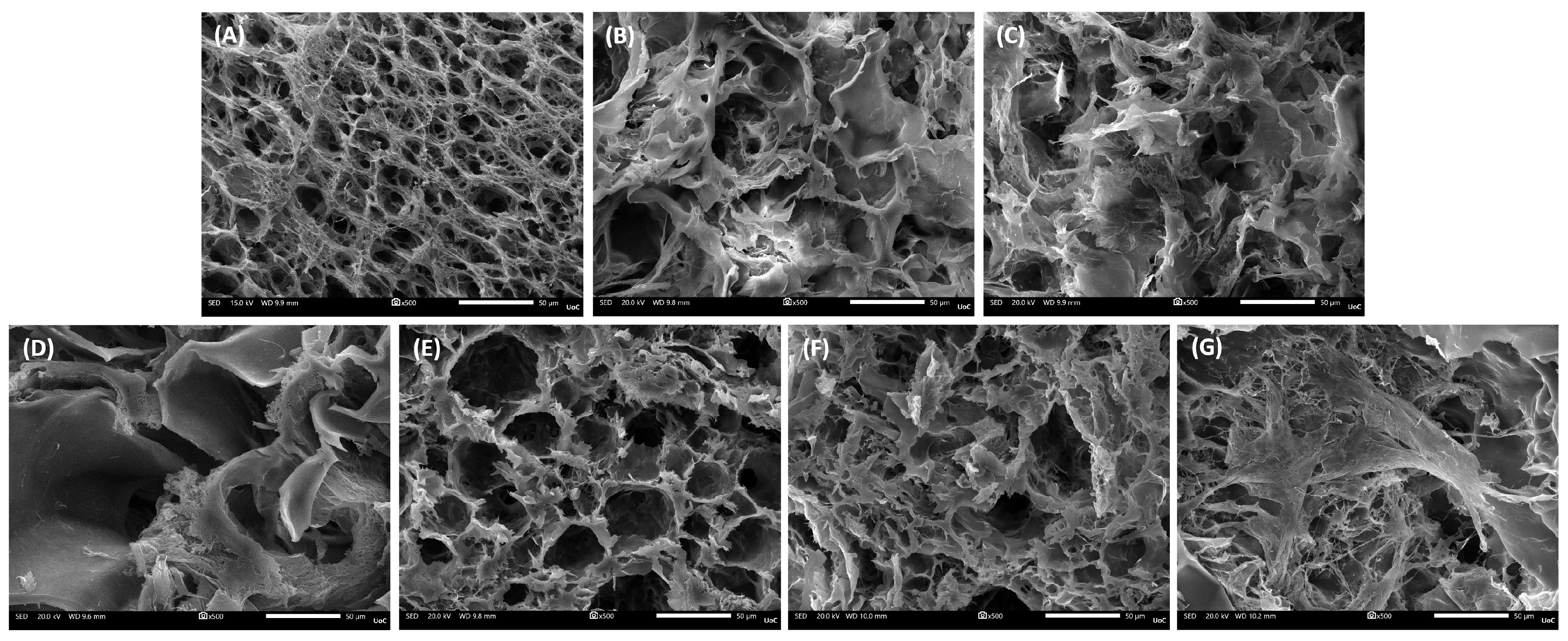

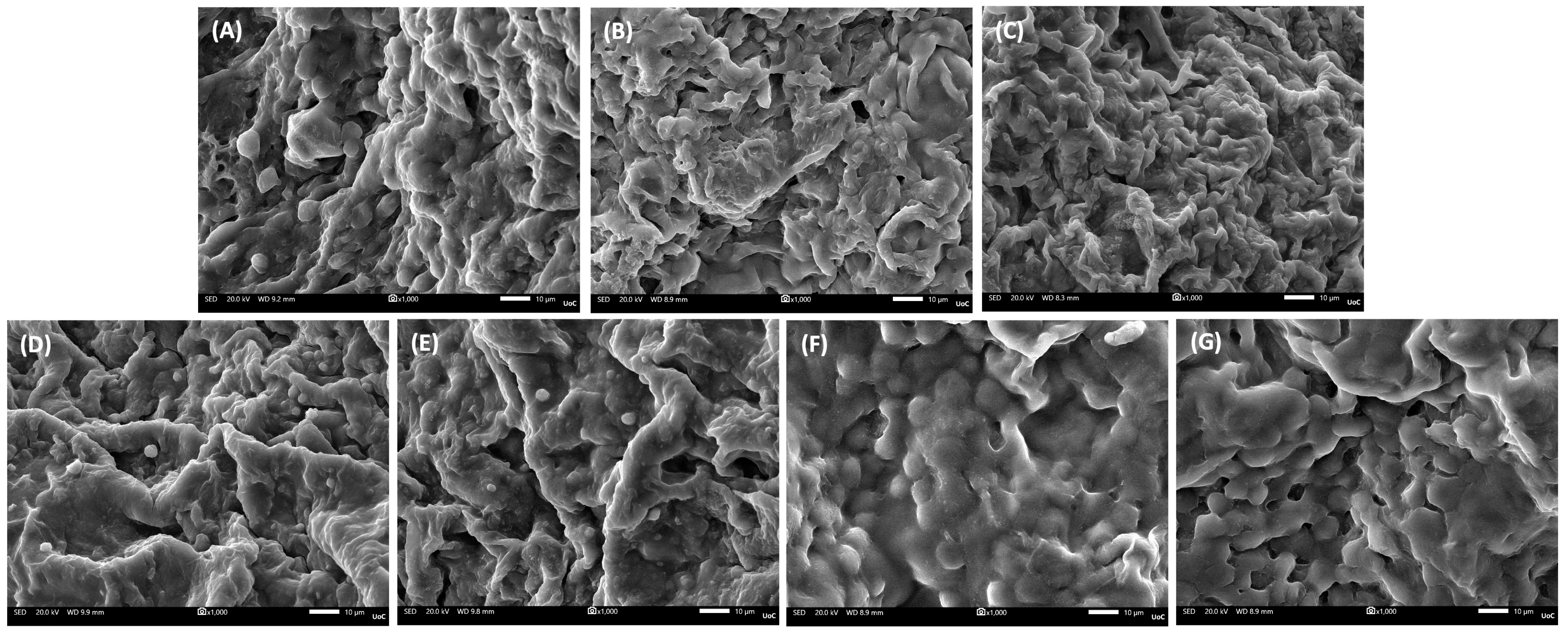

3.3. Scaffolds’ Morphology

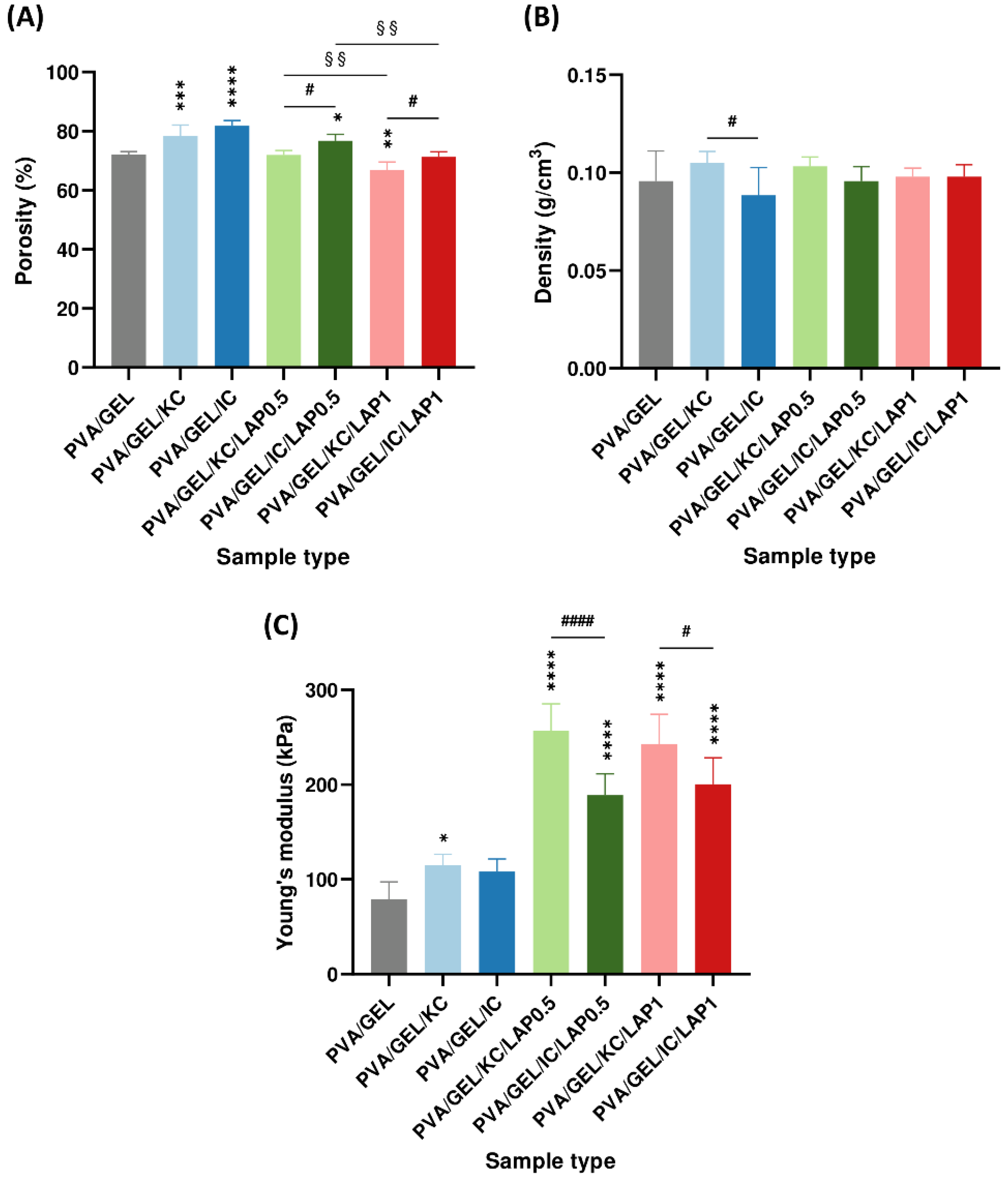

3.4. Structural and Mechanical Properties

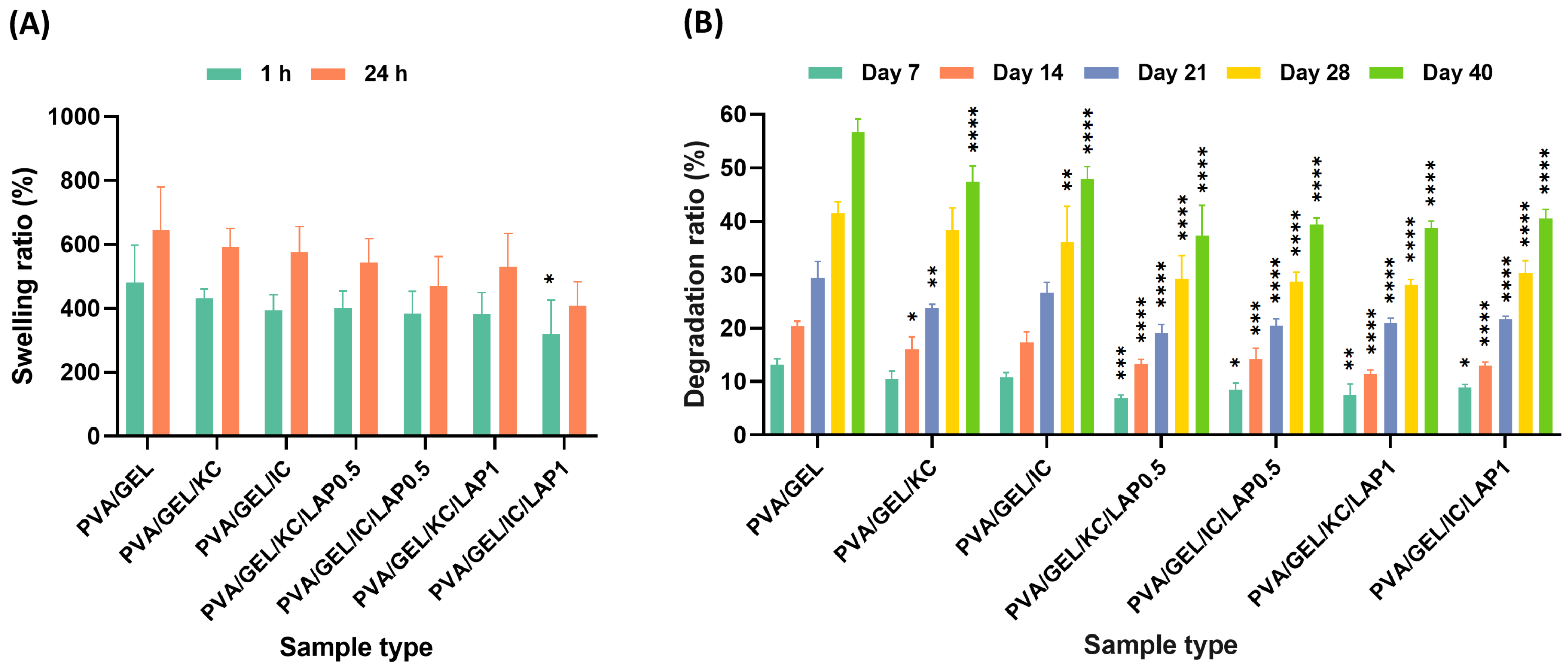

3.5. Swelling and Degradation Analysis

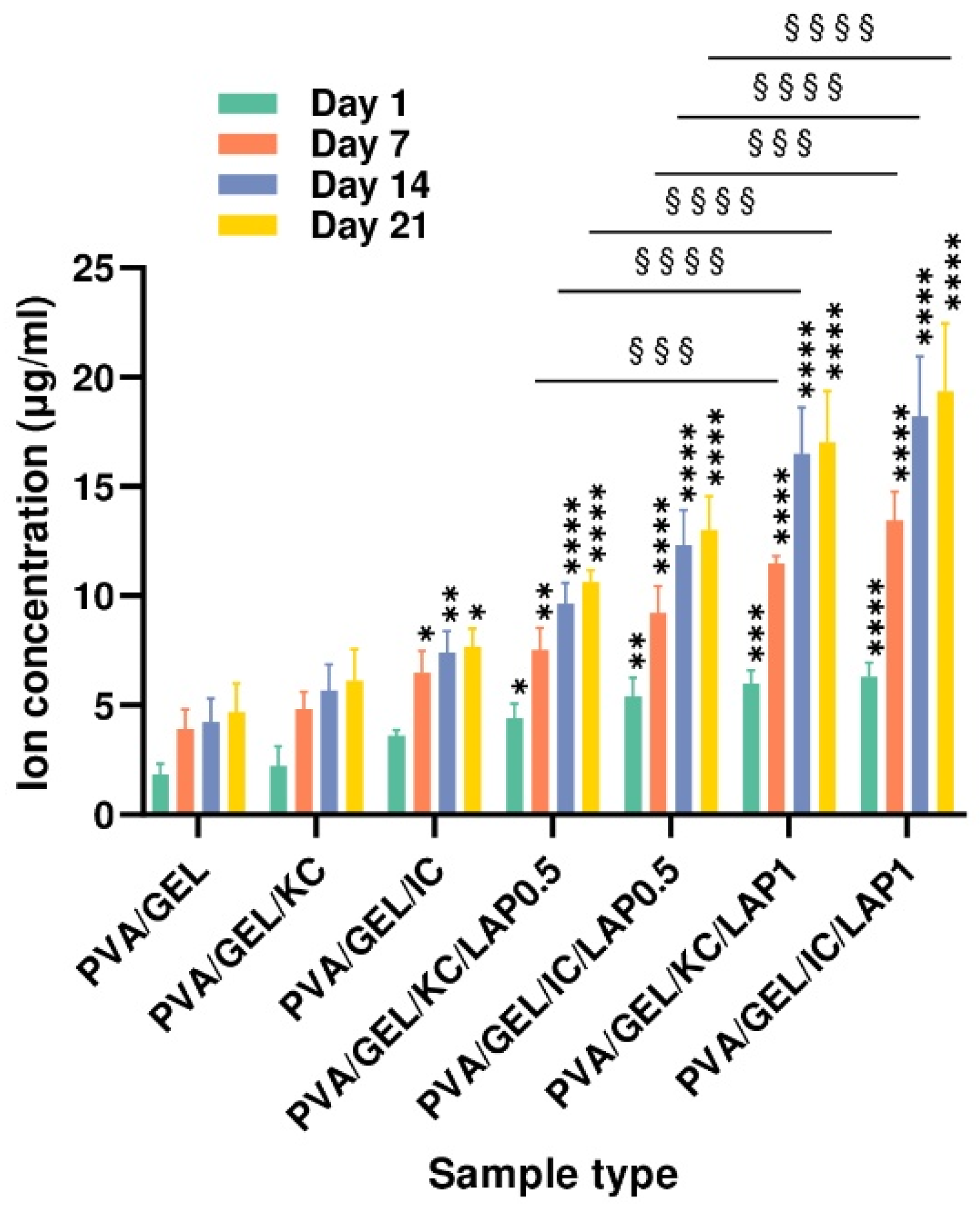

3.6. Ion Release

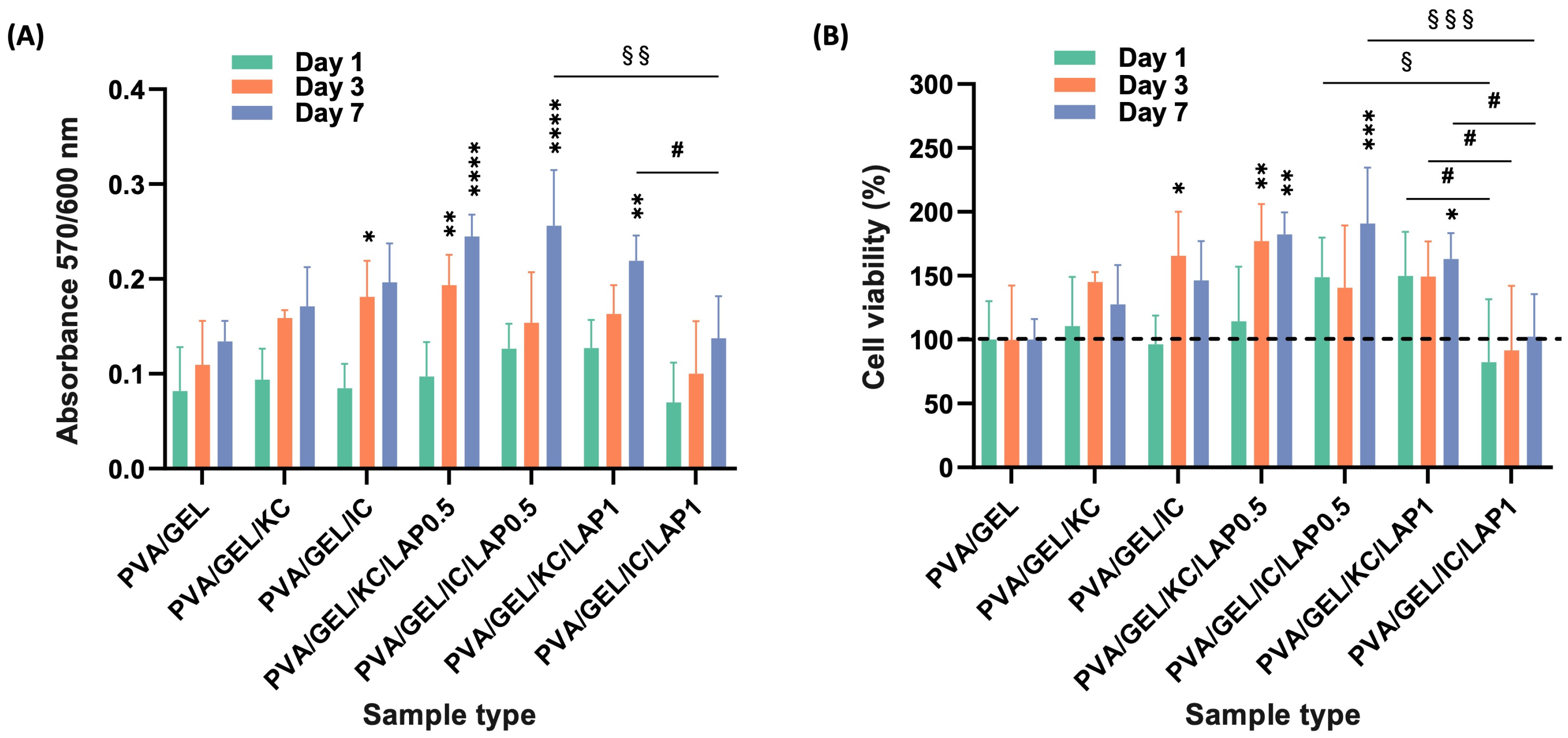

3.7. Adhesion, Morphology, Viability, and Proliferation of Pre-Osteoblasts Inside the Scaffolds

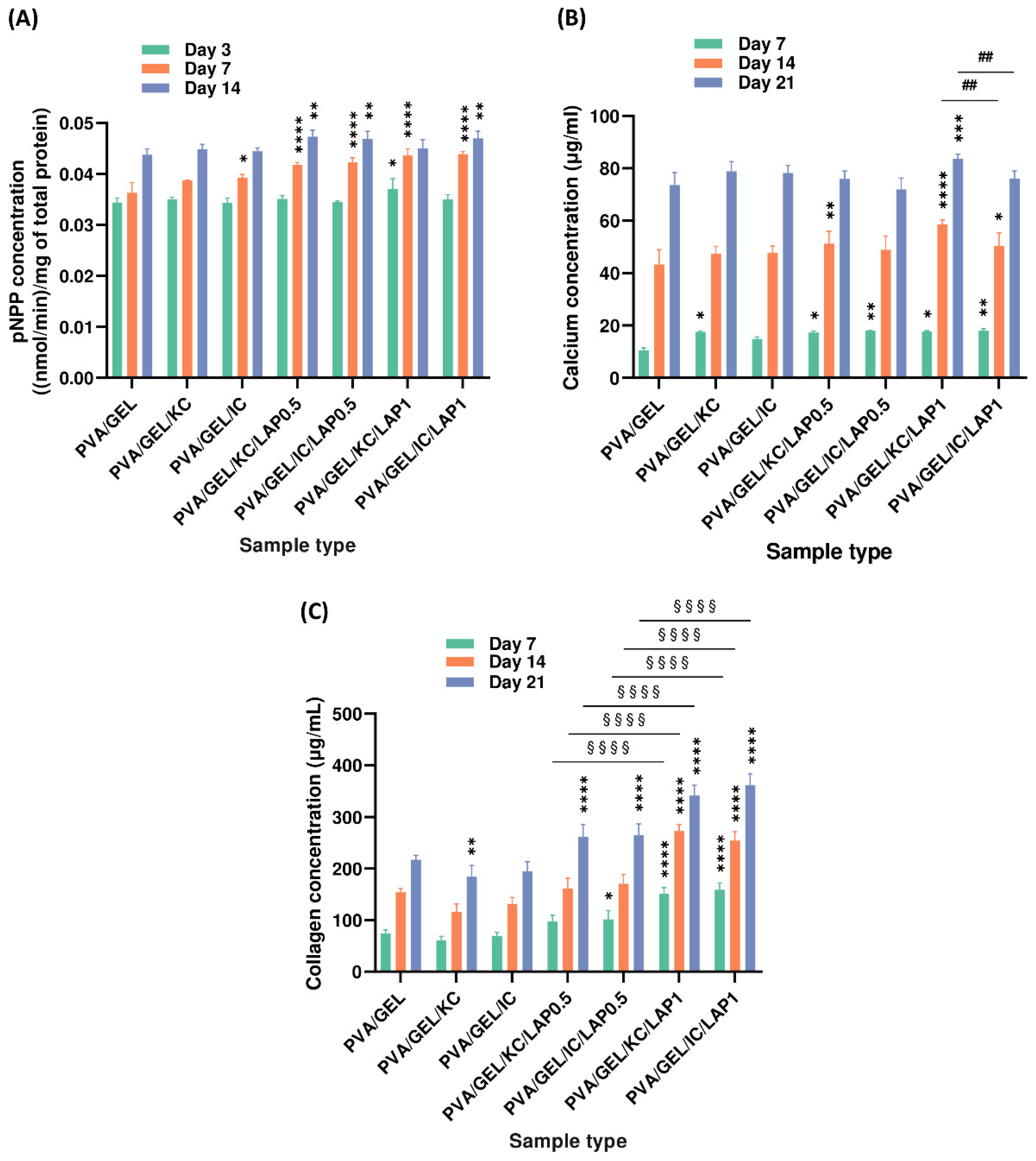

3.8. Osteogenic Differentiation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Skalak, R. Tissue engineering. In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, San Diego, CA, USA, 28–30 October 1993; pp. 1112–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’brien, F.J. Biomaterials & scaffolds for tissue engineering. Mater. Today 2011, 14, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.Z.; Thompson, I.D.; Boccaccini, A.R. 45S5 Bioglass®-derived glass–ceramic scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials 2006, 27, 2414–2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgopoulou, A.; Papadogiannis, F.; Batsali, A.; Marakis, J.; Alpantaki, K.; Eliopoulos, A.G.; Pontikoglou, C.; Chatzinikolaidou, M. Chitosan/gelatin scaffolds support bone regeneration. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2018, 29, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santoro, M.; Tatara, A.M.; Mikos, A.G. Gelatin carriers for drug and cell delivery in tissue engineering. J. Control. Release 2014, 190, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Smith, L.A.; Hu, J.; Ma, P.X. Biomimetic nanofibrous gelatin/apatite composite scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 2252–2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campo, V.L.; Kawano, D.F.; da Silva, D.B., Jr.; Carvalho, I. Carrageenans: Biological properties, chemical modifications and structural analysis–A review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2009, 77, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yegappan, R.; Selvaprithiviraj, V.; Amirthalingam, S.; Jayakumar, R. Carrageenan based hydrogels for drug delivery, tissue engineering and wound healing. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 198, 385–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akram, A.; Iqbal, M.; Yasin, A.; Zhang, K.; Li, J. Sulfonated molecules and their latest applications in the field of biomaterials: A review. Coatings 2024, 14, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loukelis, K.; Papadogianni, D.; Chatzinikolaidou, M. Kappa-carrageenan/chitosan/gelatin scaffolds enriched with potassium chloride for bone tissue engineering. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 209, 1720–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rode, M.P.; Batti Angulski, A.B.; Gomes, F.A.; da Silva, M.M.; Jeremias, T.d.S.; de Carvalho, R.G.; Iucif Vieira, D.G.; Oliveira, L.F.C.; Fernandes Maia, L.; Trentin, A.G. Carrageenan hydrogel as a scaffold for skin-derived multipotent stromal cells delivery. J. Biomater. Appl. 2018, 33, 422–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gashti, M.P.; Stir, M.; Hulliger, J. Synthesis of bone-like micro-porous calcium phosphate/iota-carrageenan composites by gel diffusion. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2013, 110, 426–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neamtu, B.; Barbu, A.; Negrea, M.O.; Berghea-Neamțu, C.Ș.; Popescu, D.; Zăhan, M.; Mireșan, V. Carrageenan-based compounds as wound healing materials. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermansson, A.-M.; Eriksson, E.; Jordansson, E. Effects of potassium, sodium and calcium on the microstructure and rheological behaviour of kappa-carrageenan gels. Carbohydr. Polym. 1991, 16, 297–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, C.M.; Peppas, N.A. Structure and applications of poly (vinyl alcohol) hydrogels produced by conventional crosslinking or by freezing/thawing methods. In Biopolymers PVA Hydrogels, Anionic Polymerisation Nanocomposites; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2000; pp. 37–65. [Google Scholar]

- Loukelis, K.; Kontogianni, G.I.; Vlassopoulos, D.; Chatzinikolaidou, M. Extrusion-Based 3D Bioprinted Gellan Gum/Poly (vinyl alcohol)/Nano-Hydroxyapatite Composite Bioinks Promote Bone Regeneration. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2025, 14, 2500365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, G.; Ma, P.X. Structure and properties of nano-hydroxyapatite/polymer composite scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials 2004, 25, 4749–4757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knaack, D.; Goad, M.; Aiolova, M.; Rey, C.; Tofighi, A.; Chakravarthy, P.; Lee, D.D. Resorbable calcium phosphate bone substitute. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1998, 43, 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loukelis, K.; Helal, Z.A.; Mikos, A.G.; Chatzinikolaidou, M. Nanocomposite bioprinting for tissue engineering applications. Gels 2023, 9, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, J.I.; Oreffo, R.O. Clay: New opportunities for tissue regeneration and biomaterial design. Adv. Mater. 2013, 25, 4069–4086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomás, H.; Alves, C.S.; Rodrigues, J. Laponite®: A key nanoplatform for biomedical applications? Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2018, 14, 2407–2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaharwar, A.K.; Mihaila, S.M.; Swami, A.; Patel, A.; Sant, S.; Reis, R.L.; Marques, A.P.; Gomes, M.E.; Khademhosseini, A. Bioactive silicate nanoplatelets for osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, 2300774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Liu, Z.L.; Xiao, M.; Yang, Z.Z.; Peng, M.Z.; Li, C.D.; Zhou, X.J.; Wang, J.W. Impact of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell immunomodulation on the osteogenic effects of laponite. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2018, 9, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yang, B.; Qian, Y.; Wang, Q.; Han, R.; Hao, T.; Shu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yao, F.; Wang, C. Iota-carrageenan/chitosan/gelatin scaffold for the osteogenic differentiation of adipose-derived MSCs in vitro. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B Appl. Biomater. 2015, 103, 1498–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettinelli, N.; Rodriguez-Llamazares, S.; Bouza, R.; Barral, L.; Feijoo-Bandin, S.; Lago, F. Carrageenan-based physically crosslinked injectable hydrogel for wound healing and tissue repairing applications. Int. J. Pharm. 2020, 589, 119828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, V.T.; Nguyen, B.T.; Nicolai, T.; Renou, F. Mobility of carrageenan chains in iota-and kappa carrageenan gels. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2019, 562, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geonzon, L.C.; Descallar, F.B.A.; Du, L.; Bacabac, R.G.; Matsukawa, S. Gelation mechanism and network structure in gels of carrageenans and their mixtures viewed at different length scales–A review. Food Hydrocoll. 2020, 108, 106039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhim, J.-W.; Wang, L.-F. Preparation and characterization of carrageenan-based nanocomposite films reinforced with clay mineral and silver nanoparticles. Appl. Clay Sci. 2014, 97, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papagiannopoulos, A.; Nikolakis, S.-P.; Pamvouxoglou, A.; Koutsopoulou, E. Physicochemical properties of electrostatically crosslinked carrageenan/chitosan hydrogels and carrageenan/chitosan/Laponite nanocomposite hydrogels. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 225, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sears, C.; Mondragon, E.; Richards, Z.I.; Sears, N.; Chimene, D.; McNeill, E.P.; Gregory, C.A.; Gaharwar, A.K.; Kaunas, R. Conditioning of 3D printed nanoengineered ionic–covalent entanglement scaffolds with iP-hMSCs derived matrix. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2020, 9, 1901580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkar, B.R.; Chauhan, U. A new method for determining micro quantities of calcium in biological materials. Anal. Biochem. 1967, 20, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.-J.; Wei, C.-K.; Lai, M.-H. Bio-inspired calcium silicate–gelatin bone grafts for load-bearing applications. J. Mater. Chem. 2011, 21, 12793–12802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Ma, P.X. Poly (α-hydroxyl acids)/hydroxyapatite porous composites for bone-tissue engineering. I. Preparation and morphology. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Off. J. Soc. Biomater. Jpn. Soc. Biomater. Aust. Soc. Biomater. 1999, 44, 446–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vimalraj, S. Alkaline phosphatase: Structure, expression and its function in bone mineralization. Gene 2020, 754, 144855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjicharalambous, C.; Kozlova, D.; Sokolova, V.; Epple, M.; Chatzinikolaidou, M. Calcium phosphate nanoparticles carrying BMP-7 plasmid DNA induce an osteogenic response in MC3T3-E1 pre-osteoblasts. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2015, 103, 3834–3842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjicharalambous, C.; Mygdali, E.; Prymak, O.; Buyakov, A.; Kulkov, S.; Chatzinikolaidou, M. Proliferation and osteogenic response of MC 3 T 3-E1 pre-osteoblastic cells on porous zirconia ceramics stabilized with magnesia or yttria. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2015, 103, 3612–3624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Ordóñez, E.; Rupérez, P. FTIR-ATR spectroscopy as a tool for polysaccharide identification in edible brown and red seaweeds. Food Hydrocoll. 2011, 25, 1514–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webber, V.; Carvalho, S.M.d.; Ogliari, P.J.; Hayashi, L.; Barreto, P.L.M. Optimization of the extraction of carrageenan from Kappaphycus alvarezii using response surface methodology. Food Sci. Technol. 2012, 32, 812–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihaila, S.M.; Gaharwar, A.K.; Reis, R.L.; Marques, A.P.; Gomes, M.E.; Khademhosseini, A. Photocrosslinkable kappa-carrageenan hydrogels for tissue engineering applications. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2013, 2, 895–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skelton, S.; Bostwick, M.; O’Connor, K.; Konst, S.; Casey, S.; Lee, B.P. Biomimetic adhesive containing nanocomposite hydrogel with enhanced materials properties. Soft Matter 2013, 9, 3825–3833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, M.L.; Oliveira, L.M.d.; Paiva, R.; Dametto, A.C.; Dias, D.d.S.; Ribeiro, C.A.; Wrona, M.; Nerín, C.; Barud, H.d.S.; Cruz, S.A. Evaluation the potential of onion/laponite composites films for sustainable food packaging with enhanced UV protection and antioxidant capacity. Molecules 2023, 28, 6829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vashisth, P.; Nikhil, K.; Roy, P.; Pruthi, P.A.; Singh, R.P.; Pruthi, V. A novel gellan–PVA nanofibrous scaffold for skin tissue regeneration: Fabrication and characterization. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 136, 851–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, M.P.; Suguna, P.; Prasad, K.; Vijaylakshmi, J.; Renuka, M. Extraction and characterization of gelatin: A functional biopolymer. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci 2017, 9, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croitoru, C.; Pop, M.A.; Bedo, T.; Cosnita, M.; Roata, I.C.; Hulka, I. Physically crosslinked poly (vinyl alcohol)/kappa-carrageenan hydrogels: Structure and applications. Polymers 2020, 12, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghani, N.A.A.; Othaman, R.; Ahmad, A.; Anuar, F.H.; Hassan, N.H. Impact of purification on iota carrageenan as solid polymer electrolyte. Arab. J. Chem. 2019, 12, 370–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Jin, X.; Wang, L.-M.; Liu, Y.D. Preparation of cellulose/laponite composite particles and their enhanced electrorheological responses. Molecules 2021, 26, 1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, L.M.; Frost, R.L.; Zhu, H.Y. Edge-modification of laponite with dimethyl-octylmethoxysilane. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2008, 321, 302–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, A.; Vahid Niknezhad, S.; Kaviani, M.; Saleh, W.; Wong, N.; Van Vliet, P.P.; Moraes, C.; Ajji, A.; Kadem, L.; Azarpira, N. Formulation and Evaluation of PVA/Gelatin/Carrageenan Inks for 3D Printing and Development of Tissue-Engineered Heart Valves. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2305188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.S.; Zhao, L.G.; Yin, Y.J.; De Yao, K. Structure and properties of bilayer chitosan–gelatin scaffolds. Biomaterials 2003, 24, 1067–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Onyeri, S.; Siewe, M.; Moshfeghian, A.; Madihally, S.V. In vitro characterization of chitosan–gelatin scaffolds for tissue engineering. Biomaterials 2005, 26, 7616–7627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Dou, X.; Meng, L.; Feng, X.; Gao, C.; Chen, F.; Tang, X. Structure, rheological properties, and biocompatibility of Laponite® cross-linked starch/polyvinyl alcohol hydrogels. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 253, 127618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadiri, M.; Chrzanowski, W.; Lee, W.; Fathi, A.; Dehghani, F.; Rohanizadeh, R. Physico-chemical, mechanical and cytotoxicity characterizations of Laponite®/alginate nanocomposite. Appl. Clay Sci. 2013, 85, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karageorgiou, V.; Kaplan, D. Porosity of 3D biomaterial scaffolds and osteogenesis. Biomaterials 2005, 26, 5474–5491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geonzon, L.C.; Bacabac, R.G.; Matsukawa, S. Network structure and gelation mechanism of kappa and iota carrageenan elucidated by multiple particle tracking. Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 92, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawde, S.; Deshmukh, K. Characterization of polyvinyl alcohol/gelatin blend hydrogel films for biomedical applications. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2008, 109, 3431–3437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasini, C.; Re, F.; Trenta, F.; Russo, D.; Sartore, L. Gelatin-Based Scaffolds with Carrageenan and Chitosan for Soft Tissue Regeneration. Gels 2024, 10, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanungo, B.P.; Gibson, L.J. Density–property relationships in collagen–glycosaminoglycan scaffolds. Acta Biomater. 2010, 6, 344–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerhardt, L.-C.; Boccaccini, A.R. Bioactive glass and glass-ceramic scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Materials 2010, 3, 3867–3910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, H.S.; Lee, C.-S. Nanoclay-composite hydrogels for bone tissue engineering. Gels 2024, 10, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilliou, L. Structure–elastic properties relationships in gelling carrageenans. Polymers 2021, 13, 4120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraguchi, K.; Takehisa, T. Nanocomposite hydrogels: A unique organic–inorganic network structure with extraordinary mechanical, optical, and swelling/de-swelling properties. Adv. Mater. 2002, 14, 1120–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivakumar, P.M.; Yetisgin, A.A.; Sahin, S.B.; Demir, E.; Cetinel, S. Bone tissue engineering: Anionic polysaccharides as promising scaffolds. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 283, 119142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zu, H.; Zhao, D.; Yang, K.; Tian, S.; Yu, X.; Lu, F.; Liu, B.; Yu, X.; Wang, B. Ion channel functional protein kinase TRPM7 regulates Mg ions to promote the osteoinduction of human osteoblast via PI3K pathway: In vitro simulation of the bone-repairing effect of Mg-based alloy implant. Acta Biomater. 2017, 63, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mignon, A.; Pezzoli, D.; Prouvé, E.; Lévesque, L.; Arslan, A.; Pien, N.; Schaubroeck, D.; Van Hoorick, J.; Mantovani, D.; Van Vlierberghe, S. Combined effect of Laponite and polymer molecular weight on the cell-interactive properties of synthetic PEO-based hydrogels. React. Funct. Polym. 2019, 136, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nourmohammadi, J.; Roshanfar, F.; Farokhi, M.; Nazarpak, M.H. Silk fibroin/kappa-carrageenan composite scaffolds with enhanced biomimetic mineralization for bone regeneration applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2017, 76, 951–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadogiannis, F.; Batsali, A.; Klontzas, M.E.; Karabela, M.; Georgopoulou, A.; Mantalaris, A.; Zafeiropoulos, N.E.; Chatzinikolaidou, M.; Pontikoglou, C. Osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells on chitosan/gelatin scaffolds: Gene expression profile and mechanical analysis. Biomed. Mater. 2020, 15, 064101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salifu, A.A.; Lekakou, C.; Labeed, F.H. Electrospun oriented gelatin-hydroxyapatite fiber scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2017, 105, 1911–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahdavinia, G.R.; Massoudi, A.; Baghban, A.; Massoumi, B. Novel carrageenan-based hydrogel nanocomposites containing laponite RD and their application to remove cationic dye. Iran. Polym. J. 2012, 21, 609–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppe, A.; Güldal, N.S.; Boccaccini, A.R. A review of the biological response to ionic dissolution products from bioactive glasses and glass-ceramics. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 2757–2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Scaffold Acronyms | Composition |

|---|---|

| PVA/GEL | 3% w/v PVA, 3% w/v gelatin, crosslinked with 0.25% w/v glutaraldehyde. |

| PVA/GEL/KC | 3% w/v PVA, 3% w/v gelatin, 1% w/v kappa-carrageenan, crosslinked with 0.25% w/v glutaraldehyde and 0.2 M KCl. |

| PVA/GEL/IC | 3% w/v PVA, 3% w/v gelatin, 1% w/v iota-carrageenan, crosslinked with 0.25% w/v glutaraldehyde and 0.2 M KCl. |

| PVA/GEL/KC/LAP0.5 | 3% w/v PVA, 3% w/v gelatin, 1% w/v kappa-carrageenan, 0.5% w/v laponite, crosslinked with 0.25% w/v glutaraldehyde and 0.2 M KCl. |

| PVA/GEL/IC/LAP0.5 | 3% w/v PVA, 3% w/v gelatin, 1% w/v iota-carrageenan, 0.5% w/v laponite, crosslinked with 0.25% w/v glutaraldehyde and 0.2 M KCl. |

| PVA/GEL/KC/LAP1 | 3% w/v PVA, 3% w/v gelatin, 1% w/v kappa-carrageenan, 1% w/v laponite, crosslinked with 0.25% w/v glutaraldehyde and 0.2 M KCl. |

| PVA/GEL/IC/LAP1 | 3% w/v PVA, 3% w/v gelatin, 1% w/v iota-carrageenan, 1% w/v laponite, crosslinked with 0.25% w/v glutaraldehyde and 0.2 M KCl. |

| Scaffold Acronyms | C | O | Cl | K | Mg | Si | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PVA/GEL | 58% | 40% | 1% | 1% | |||

| PVA/GEL/KC | 55% | 40% | 2% | 3% | |||

| PVA/GEL/IC | 55% | 42% | 1% | 2% | |||

| PVA/GEL/KC/LAP0.5 | 53% | 40% | 1% | 2% | 1% | 2% | |

| PVA/GEL/IC/LAP0.5 | 51% | 42% | 1% | 2% | 1% | 2% | 1% |

| PVA/GEL/KC/LAP1 | 53% | 39% | 1% | 2% | 2% | 2% | 1% |

| PVA/GEL/IC/LAP1 | 49% | 42% | 1% | 2% | 2% | 3% | 1% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Karamesouti, A.; Chatzinikolaidou, M. Effect of Sulfated Polysaccharides and Laponite in Composite Porous Scaffolds on Osteogenesis. Biomolecules 2026, 16, 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010080

Karamesouti A, Chatzinikolaidou M. Effect of Sulfated Polysaccharides and Laponite in Composite Porous Scaffolds on Osteogenesis. Biomolecules. 2026; 16(1):80. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010080

Chicago/Turabian StyleKaramesouti, Angelina, and Maria Chatzinikolaidou. 2026. "Effect of Sulfated Polysaccharides and Laponite in Composite Porous Scaffolds on Osteogenesis" Biomolecules 16, no. 1: 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010080

APA StyleKaramesouti, A., & Chatzinikolaidou, M. (2026). Effect of Sulfated Polysaccharides and Laponite in Composite Porous Scaffolds on Osteogenesis. Biomolecules, 16(1), 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010080