Mechanism of T7 Primase Selecting Active Priming Sites Among Genome

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protein Expression and Purification

2.2. Binding Affinity Evaluation by Agarose Gel Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA)

2.3. Primer Synthesis Activity Analysis

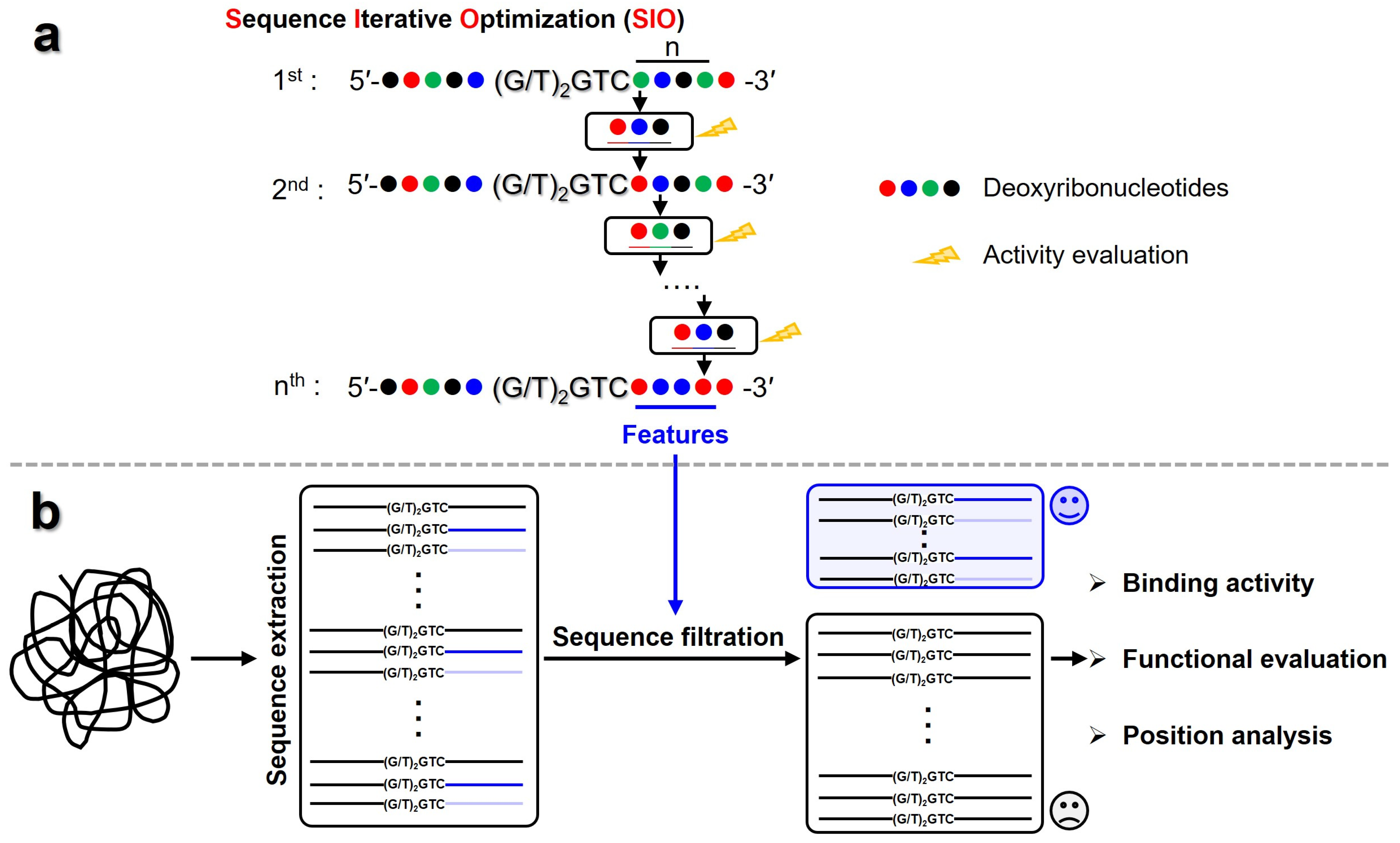

2.4. Sequence Iterative Optimization (SIO) Strategy

2.5. Screening of Potential Priming Sites in the T7 Phage Genome

2.6. Protein–ssDNA Docking and Interaction Analysis

2.7. Site-Directed Mutagenesis

2.8. Data Analysis

3. Results

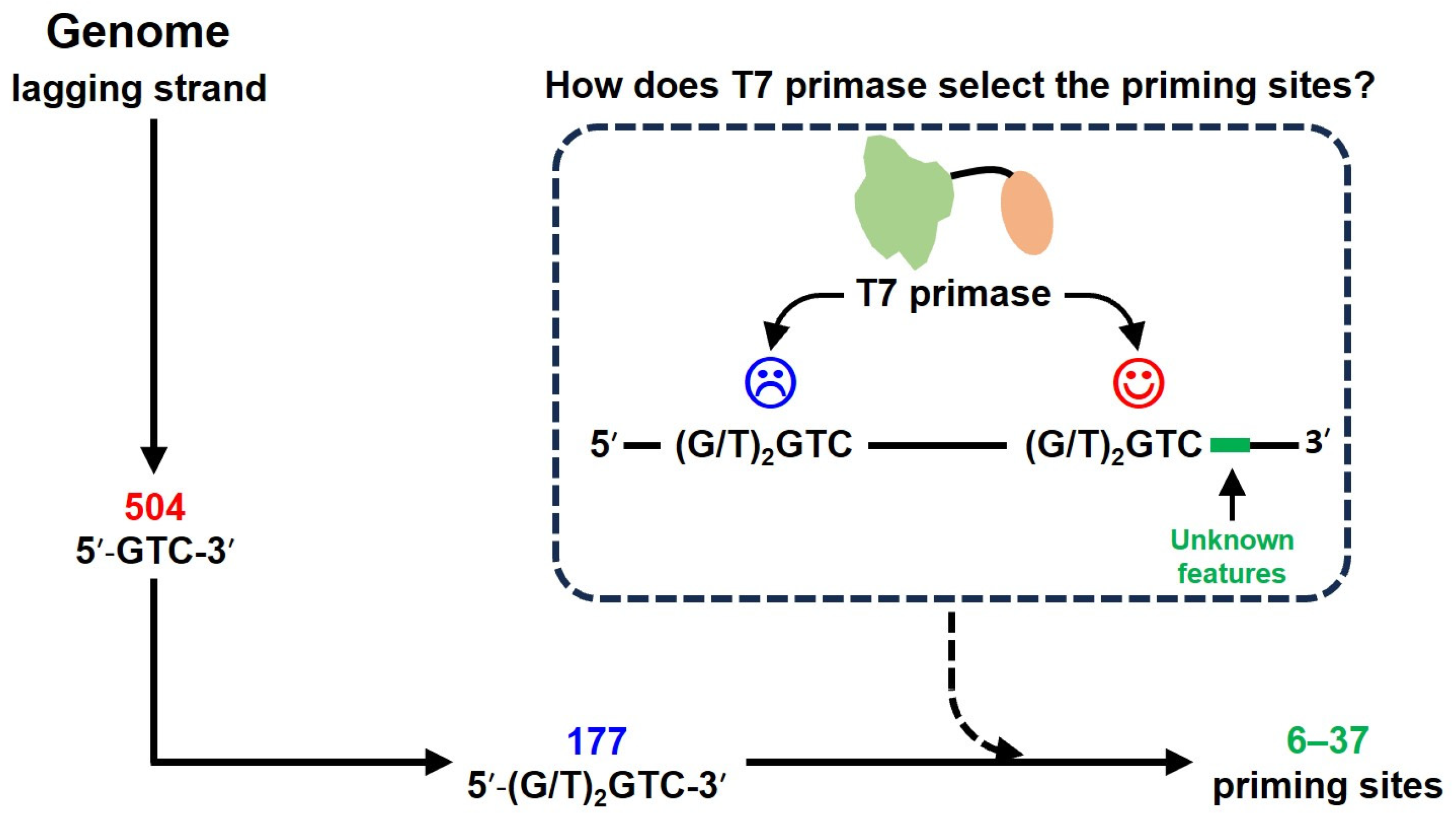

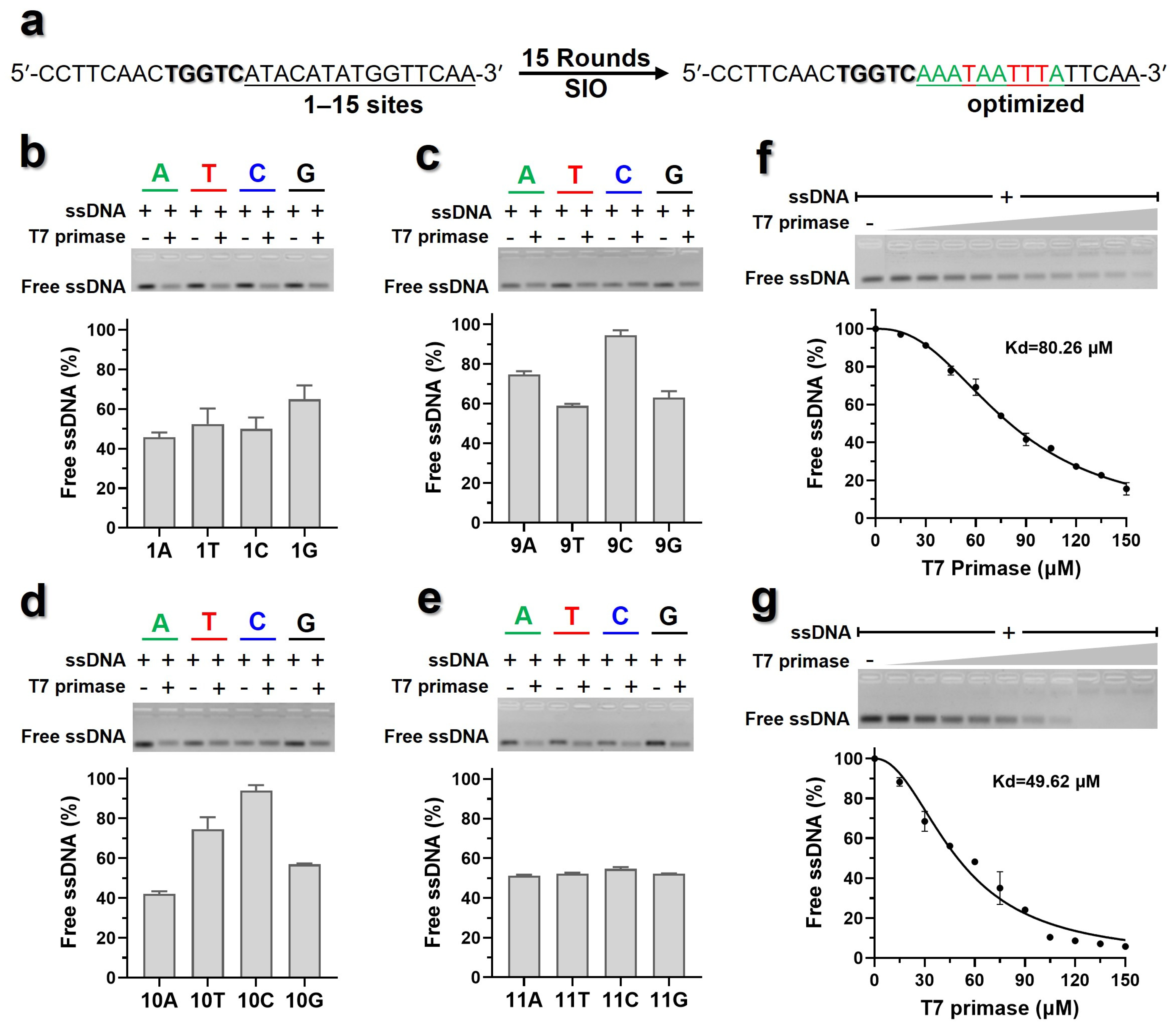

3.1. 3′ Flanks of 5′-(G/T)2GTC-3′ Contributes to the Binding Affinities of T7 Primase to ssDNA

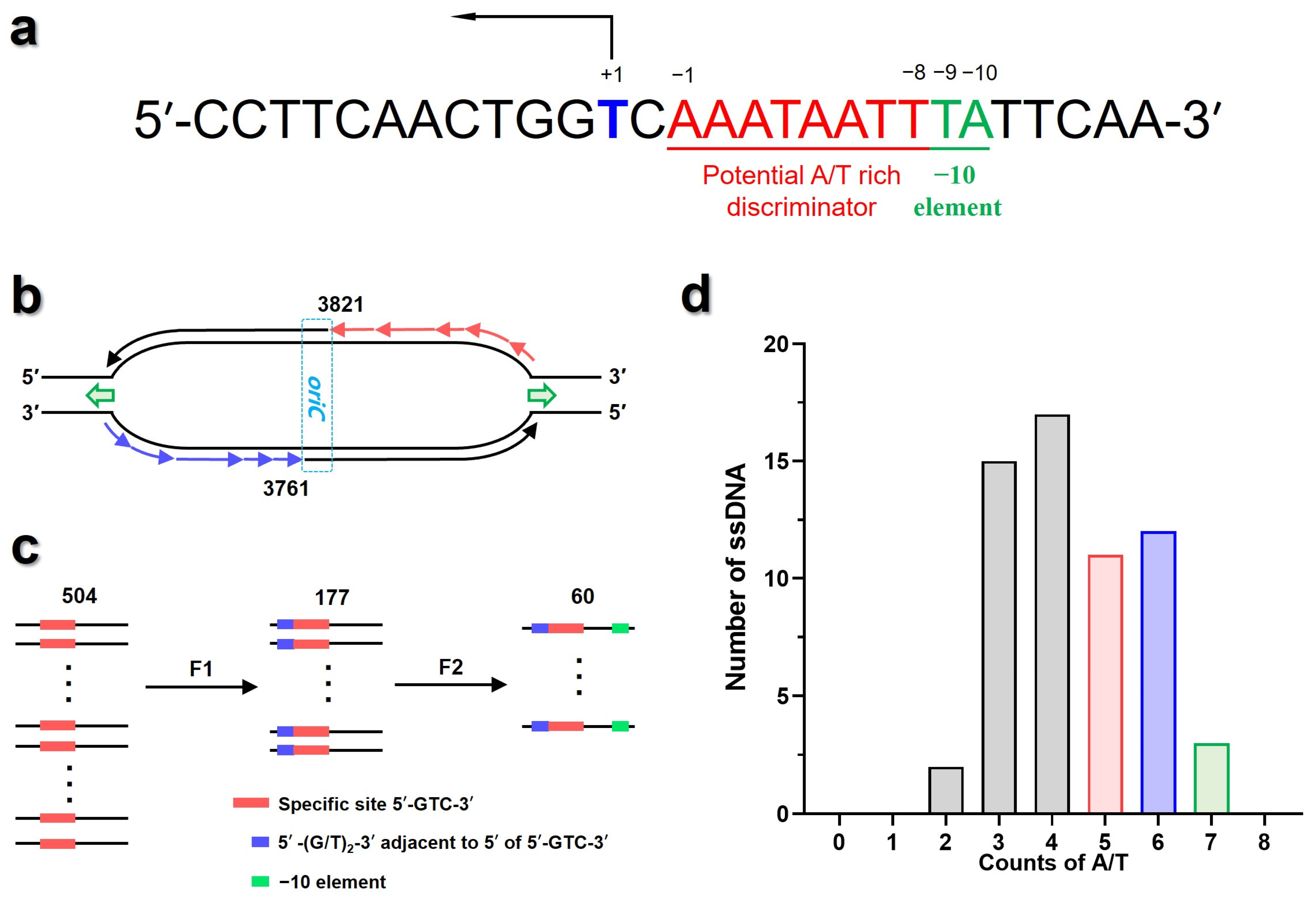

3.2. Screening the Potential Initiation Sites from T7 Phage Genome

3.3. Binding Affinity of Candidate ssDNA to T7 Primase

3.4. Primer Synthesis Activity of T7 Primase with Candidate ssDNA as Template

3.5. Mapping the Active Priming Sites onto the Genome of T7 Phage

3.6. The ZBD Might Interact with the −10 Element in 3′ Flanks of the Pentanucleotide Site

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bramhill, D.; Kornberg, A. Duplex opening by dnaA protein at novel sequences in initiation of replication at the origin of the E. coli chromosome. Cell 1988, 52, 743–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinks, R.R.; Spenkelink, L.M.; Stratmann, S.A.; Xu, Z.Q.; Stamford, N.P.J.; Brown, S.E.; Dixon, N.E.; Jergic, S.; van Oijen, A.M. DnaB helicase dynamics in bacterial DNA replication resolved by single-molecule studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, 6804–6816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antony, E.; Lohman, T.M. Dynamics of E. coli single stranded DNA binding (SSB) protein-DNA complexes. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2019, 86, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fijalkowska, I.J.; Schaaper, R.M.; Jonczyk, P. DNA replication fidelity in Escherichia coli: A multi-DNA polymerase affair. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2012, 36, 1105–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J.S.; Jergic, S.; Dixon, N.E. The E. coli DNA Replication Fork. Enzymes 2016, 39, 31–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frick, D.N.; Richardson, C.C. DNA primases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2001, 70, 39–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oakley, A.J. A structural view of bacterial DNA replication. Protein Sci. 2019, 28, 990–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoda, K.; Okazaki, T. Specificity of recognition sequence for Escherichia coli primase. Mol. Gen. Genet. MGG 1991, 227, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, M.A.; Bressani, R.; Sayood, K.; Corn, J.E.; Berger, J.M.; Griep, M.A.; Hinrichs, S.H. Hyperthermophilic Aquifex aeolicus initiates primer synthesis on a limited set of trinucleotides comprised of cytosines and guanines. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008, 36, 5260–5269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rannou, O.; Le Chatelier, E.; Larson, M.A.; Nouri, H.; Dalmais, B.; Laughton, C.; Jannière, L.; Soultanas, P. Functional interplay of DnaE polymerase, DnaG primase and DnaC helicase within a ternary complex, and primase to polymerase hand-off during lagging strand DNA replication in Bacillus subtilis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, 5303–5320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kusakabe, T.; Richardson, C.C. Template recognition and ribonucleotide specificity of the DNA primase of bacteriophage T7. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 5943–5951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soffer, A.; Eisdorfer, S.A.; Ifrach, M.; Ilic, S.; Afek, A.; Schussheim, H.; Vilenchik, D.; Akabayov, B. Inferring primase-DNA specific recognition using a data driven approach. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, 11447–11458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Chastain, P.D., 2nd; Griffith, J.D.; Richardson, C.C. Lagging strand synthesis in coordinated DNA synthesis by bacteriophage T7 replication proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 2002, 316, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afek, A.; Ilic, S.; Horton, J.; Lukatsky, D.B.; Gordan, R.; Akabayov, B. DNA Sequence Context Controls the Binding and Processivity of the T7 DNA Primase. iScience 2018, 2, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, M.; Ito, T.; Wagner, G.; Ellenberger, T. A molecular handoff between bacteriophage T7 DNA primase and T7 DNA polymerase initiates DNA synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 30554–30562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J.; Zhu, B.; Hamdan, S.M.; Richardson, C.C. Mechanism of sequence-specific template binding by the DNA primase of bacteriophage T7. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, 4372–4383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zechner, E.L.; Wu, C.A.; Marians, K.J. Coordinated leading- and lagging-strand synthesis at the Escherichia coli DNA replication fork. III. A polymerase-primase interaction governs primer size. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 4054–4063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.; Debyser, Z.; Tabor, S.; Richardson, C.C.; Griffith, J.D. Formation of a DNA loop at the replication fork generated by bacteriophage T7 replication proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 5260–5270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdan, S.M.; Loparo, J.J.; Takahashi, M.; Richardson, C.C.; van Oijen, A.M. Dynamics of DNA replication loops reveal temporal control of lagging-strand synthesis. Nature 2009, 457, 336–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabor, S.; Richardson, C.C. Template recognition sequence for RNA primer synthesis by gene 4 protein of bacteriophage T7. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1981, 78, 205–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frick, D.N.; Richardson, C.C. Interaction of bacteriophage T7 gene 4 primase with its template recognition site. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 35889–35898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Luo, H.; Zhang, Z.-M.; Song, X.; Wang, G.-G. Studies on The Interaction Between DnaG Primase and ssDNA Template in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Prog. Biochem. Biophys. 2024, 51, 1920–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, M.; Lei, L.; Egli, M. Label-Free Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA) for Measuring Dissociation Constants of Protein-RNA Complexes. Curr. Protoc. Nucleic Acid Chem. 2019, 76, e70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kricka, L.J. Stains, labels and detection strategies for nucleic acids assays. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 2002, 39, 114–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.R. Staining nucleic acids and proteins in electrophoresis gels. Biotech. Histochem. 2001, 76, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, T.; Resto-Roldán, E.; Sawyer, S.K.; Artsimovitch, I.; Tsodikov, O.V. A novel non-radioactive primase-pyrophosphatase activity assay and its application to the discovery of inhibitors of Mycobacterium tuberculosis primase DnaG. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, e56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, M.; Ito, T.; Wagner, G.; Richardson, C.C.; Ellenberger, T. Modular architecture of the bacteriophage T7 primase couples RNA primer synthesis to DNA synthesis. Mol. Cell 2003, 11, 1349–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abramson, J.; Adler, J.; Dunger, J.; Evans, R.; Green, T.; Pritzel, A.; Ronneberger, O.; Willmore, L.; Ballard, A.J.; Bambrick, J.; et al. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 2024, 630, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, W.; Qin, L.; Li, M.; Pu, X.; Guo, Y. A structural dissection of protein-RNA interactions based on different RNA base areas of interfaces. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 10582–10592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shazman, S.; Celniker, G.; Haber, O.; Glaser, F.; Mandel-Gutfreund, Y. Patch Finder Plus (PFplus): A web server for extracting and displaying positive electrostatic patches on protein surfaces. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, W526–W530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munteanu, B.; Braun, M.; Boonrod, K. Improvement of PCR reaction conditions for site-directed mutagenesis of big plasmids. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B 2012, 13, 244–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, H.; Tabor, S.; Tamanoi, F.; Richardson, C.C. Nucleotide sequence of the primary origin of bacteriophage T7 DNA replication: Relationship to adjacent genes and regulatory elements. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1980, 77, 3917–3921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulczyk, A.W.; Richardson, C.C. The Replication System of Bacteriophage T7. Enzymes 2016, 39, 89–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipps, G. Definition of the binding specificity of the T7 bacteriophage primase by analysis of a protein binding microarray using a thermodynamic model. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, 4818–4829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, C.; Biswas, T.; Tsodikov, O.V. Structures of the Catalytic Domain of Bacterial Primase DnaG in Complexes with DNA Provide Insight into Key Priming Events. Biochemistry 2018, 57, 2084–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Lee, S.J.; Richardson, C.C. Direct role for the RNA polymerase domain of T7 primase in primer delivery. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 9099–9104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, R.; Mukherjee, S. T7 RNA polymerase. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 2003, 73, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, A.J.; Lee, S.J.; Thompson, N.J.; Griffith, J.D.; Richardson, C.C. Residues located in the primase domain of the bacteriophage T7 primase-helicase are essential for loading the hexameric complex onto DNA. J. Biol. Chem. 2022, 298, 101996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rymer, R.U.; Solorio, F.A.; Tehranchi, A.K.; Chu, C.; Corn, J.E.; Keck, J.L.; Wang, J.D.; Berger, J.M. Binding mechanism of metal⋅NTP substrates and stringent-response alarmones to bacterial DnaG-type primases. Structure 2012, 20, 1478–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corn, J.E.; Pelton, J.G.; Berger, J.M. Identification of a DNA primase template tracking site redefines the geometry of primer synthesis. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2008, 15, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.J.; Richardson, C.C. Essential lysine residues in the RNA polymerase domain of the gene 4 primase-helicase of bacteriophage T7. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 49419–49426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Fang, X.; Du, R.; Wang, J.; Liu, M.; Xu, P.; Li, S.; Zhang, K.; Ye, S.; You, Q.; et al. Principles of Amino-Acid-Nucleotide Interactions Revealed by Binding Affinities between Homogeneous Oligopeptides and Single-Stranded DNA Molecules. Chembiochem 2022, 23, e202200048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaeffer, P.M.; Headlam, M.J.; Dixon, N.E. Protein--protein interactions in the eubacterial replisome. IUBMB Life 2005, 57, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, A.J.; Lee, S.J.; Richardson, C.C. Primer release is the rate-limiting event in lagging-strand synthesis mediated by the T7 replisome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 5916–5921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, A.J.; Richardson, C.C. Gp2.5, the multifunctional bacteriophage T7 single-stranded DNA binding protein. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2019, 86, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borkotoky, S.; Murali, A. The highly efficient T7 RNA polymerase: A wonder macromolecule in biological realm. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 118, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passalacqua, L.F.M.; Dingilian, A.I.; Lupták, A. Single-pass transcription by T7 RNA polymerase. RNA 2020, 26, 2062–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turecka, K.; Firczuk, M.; Werel, W. Alteration of the −35 and −10 sequences and deletion the upstream sequence of the −35 region of the promoter A1 of the phage T7 in dsDNA confirm the contribution of non-specific interactions with E. coli RNA polymerase to the transcription initiation process. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2024, 10, 1335409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusakabe, T.; Hine, A.V.; Hyberts, S.G.; Richardson, C.C. The Cys4 zinc finger of bacteriophage T7 primase in sequence-specific single-stranded DNA recognition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 4295–4300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hine, A.V.; Richardson, C.C. A functional chimeric DNA primase: The Cys4 zinc-binding domain of bacteriophage T3 primase fused to the helicase of bacteriophage T7. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1994, 91, 12327–12331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, R.R.; Laine, P.S. The single-stranded DNA-binding protein of Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Rev. 1990, 54, 342–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feklistov, A.; Bae, B.; Hauver, J.; Lass-Napiorkowska, A.; Kalesse, M.; Glaus, F.; Altmann, K.H.; Heyduk, T.; Landick, R.; Darst, S.A. RNA polymerase motions during promoter melting. Science 2017, 356, 863–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Cui, Y.; Fox, T.; Lin, S.; Wang, H.; de Val, N.; Zhou, Z.H.; Yang, W. Structures and operating principles of the replisome. Science 2019, 363, eaav7003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, X.; Spiering, M.M.; de Luna Almeida Santos, R.; Benkovic, S.J.; Li, H. Structural basis of the T4 bacteriophage primosome assembly and primer synthesis. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 4396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| No. | Chain | Central T | Sequence (5′ to 3′) | Regions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | Negative | 246 | GACTTGATGGGTCTTTAGGTGTAGGCTT | 230–257 |

| S2 | Negative | 287 | TTTAGGTCTGGTCTTTATGTTTAAACTT | 271–298 |

| S3 | Negative | 300 | TTTAGGTCTGGTCTTTAGGTCTGGTCTT | 284–311 |

| S4 | Negative | 313 | TTTATGTAGTGTCTTTAGGTCTGGTCTT | 297–324 |

| S5 | Negative | 412 | TCTTTAAGTTGTCTCTCCTTATAGTGAG | 396–423 |

| S6 | Negative | 1363 | AGCCAGAGTGGTCTTAATGGTGATGTAC | 1347–1374 |

| S7 | Negative | 3860 | AGAACGTTTGGTCATCTTTTCGAAGTTA | 3844–3871 |

| S8 | Positive | 3961 | AGCTGGGAGGGTCAGTAAGATGGGACGT | 3950–3977 |

| S9 | Positive | 5287 | GGCTGGGCGTGTCAAATTAGCTACATGG | 5276–5303 |

| S10 | Positive | 5700 | ATGCCAGATGGTCACGCTTAATACGACT | 5689–5716 |

| S11 | Positive | 7096 | CCCTCGTGGTGTCTATAAAGTTGACCTG | 7085–7112 |

| S12 | Positive | 9763 | GCAAACGAGTGTCACCTAAATGGTCACG | 9752–9779 |

| S13 | Positive | 15,893 | GCGTATATTGGTCTGGATCTTTGTGTTC | 15,882–15,909 |

| S14 | Positive | 16,862 | AACGTCCGTTGTCATTAATCCTGAGGCA | 16,851–16,878 |

| S15 | Positive | 18,205 | TGTACCGATTGTCTTCTTATGTGGTCCA | 18,194–18,221 |

| S16 | Positive | 18,485 | GATTCGGATGGTCAGACTAGATGGTGAA | 18,474–18,501 |

| S17 | Positive | 22,896 | GCACCTAGTGGTCAACAGATTGACTCCT | 22,885–22,912 |

| S18 | Positive | 29,011 | TATGGTCGGTGTCACTGGTAAGGGCTTT | 29,000–29,027 |

| S19 | Positive | 29,356 | ACATAATGGTGTCCCTTATGAGGACTTA | 29,345–29,372 |

| S20 | Positive | 32,365 | TACTATCGGTGTCAATAACGATGGTCAC | 32,354–32,381 |

| S21 | Positive | 34,015 | ACAGATAGTGGTCTTTATGGATGTCATT | 34,004–34,031 |

| S22 | Positive | 34,157 | GGCATCTAGGGTCAGACTCAATGGACGC | 34,146–34,173 |

| S23 | Positive | 34,757 | TCGTTGTGTGGTCCTTATGGAGAGACCC | 34,746–34,773 |

| S24 | Positive | 34,975 | GGTATCACTGGTCAGTTAACTGGTAGCC | 34,964–34,991 |

| S25 | Positive | 36,818 | GCCTCTAATGGTCTATCCTAAGGTCTAT | 36,807–36,834 |

| S26 | Positive | 36,908 | TTCCTATAGGGTCCTTTAAAATATACCA | 36,897–36,924 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, Z.; Chen, J.; Liu, W.; Wang, Y.; Cai, H.; Wang, G. Mechanism of T7 Primase Selecting Active Priming Sites Among Genome. Biomolecules 2026, 16, 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010078

Zhang Z, Chen J, Liu W, Wang Y, Cai H, Wang G. Mechanism of T7 Primase Selecting Active Priming Sites Among Genome. Biomolecules. 2026; 16(1):78. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010078

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Zhiming, Jiang Chen, Wenyue Liu, Yu Wang, Haoyang Cai, and Ganggang Wang. 2026. "Mechanism of T7 Primase Selecting Active Priming Sites Among Genome" Biomolecules 16, no. 1: 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010078

APA StyleZhang, Z., Chen, J., Liu, W., Wang, Y., Cai, H., & Wang, G. (2026). Mechanism of T7 Primase Selecting Active Priming Sites Among Genome. Biomolecules, 16(1), 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010078