Abstract

Rhododendron tomentosum is an aromatic plant belonging to the Ericaceae family, widely used for different applications, but still lacking in its molecular signature. This work provides a complete chemical and biological characterization of the hydroalcoholic extract of R. tomentosum tips of twigs. Combining untargeted metabolomic analysis with bioassays, a correlation between chemical composition and biological activity was defined. To this regard, liquid chromatography high-resolution tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) revealed a heterogeneous chemical composition, including flavonoids, such as quercetin, catechin, and their derivatives, as well as a first tentative identification of novel aesculin derivatives. Cell-based model experiments on stressed immortalized human keratinocytes demonstrated the antioxidant activity of the extract. Moreover, it exhibited significant antifungal and antibacterial effects against Trichoderma atroviride AGR2, Botrytis cinerea, and Clavibacter michiganensis, while promoting the growth of the beneficial bacterium Bacillus amyloliquefaciens. These findings highlight the rich diversity of bioactive molecules present in R. tomentosum hydroalcoholic extract, bridging its chemical composition to its functional properties. Overall, these results suggest its promising potential for applications in improving plant health, as well as in pharmaceutical, cosmetic, and agricultural industries.

1. Introduction

Plants are the primary source of bioactive metabolites with potential industrial application as sustainable alternatives to chemically synthetized products, as bioprotectants and biostimulants in agricultural systems, as well as a source of active molecules for pharmaceutical and cosmetic applications [1,2,3,4]. Phytometabolites have largely been investigated for their role in the plant defense system against herbivores, insects, and environmental stresses in agricultural systems [1,5]. Among them, essential oils have been largely investigated for their insecticidal, virucidal, fungicidal, bactericidal, and antiparasitic properties [6,7]. Despite the possible economic relevance, the large use of plant extracts to replace synthetic products is still poorly exploited.

Rhododendron tomentosum, formerly Ledum palustre, is an aromatic plant belonging to the Ericaceae family. It is widely spread in boreal forests, mires, and damp heaths of the Northern Hemisphere, such as Scandinavia, Ireland, and Canada. R. tomentosum is also known as wild rosemary, marsh tea or marsh rosemary, and Labrador tea [8]. To date, R. tomentosum extracts are normally obtained from the aerial parts of the plant and used in different forms, such as decoctions, purified essential oils, aqueous or oil infusion preparations, or hydroalcoholic extracts, with applications in the medical and insecticidal fields [9]. The anti-inflammatory and antiseptic properties of these preparations have been attributed to polyphenols and sesquiterpenes [10,11], whereas the insecticidal activity has been related to the composition of the essential oil [12,13], which has recently been proven to be toxic for humans depending on the dose [9].

To date, the literature on R. tomentosum chemical characterization relies on specific classes of compounds, such as coumarins and flavonoids [14,15,16,17], but a comprehensive metabolomic identification, along with a broad evaluation of its biological activities, is still lacking. Filling this gap could be particularly relevant, as phytochemicals hold significant potential for different industrial applications, including cosmetic formulations, natural antimicrobials, and environmentally friendly plant protection products. By integrating multiple analytical and biological approaches, the present study established the interconnection between chemical composition and functional activity of R. tomentosum extract.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

All reagents, liquid chromatography mass spectrometry solvents, and the library of phytochemical standards were purchased from Merck-Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), unless differently specified. The R. tomentosum hydroalcoholic extract was purchased by HERBAMED AG (Bühler, Switzerland). According to the manufacturer, plants were cultivated through wild harvesting in Ukraine, and tips of twigs were manually collected in June 2020. The extraction process was standardized according to German Homeopathic Pharmacopoeia (GHP). Briefly, the extract was prepared by percolating for 12 days dried tips of twigs with 70% ethanol and 30% H2O (v/v) in a ratio between biomass and solvent of 1:10 (w/w). Three hydroalcoholic extract batches were used.

2.2. Liquid Chromatography High-Resolution Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) Analysis

Aliquots of 1 mL of R. tomentosum extract were evaporated using N2, then dissolved in 1 mL of a methanol/water (70:30, v/v). The suspension was vortexed for 10 min and then centrifuged (18,000× g, 10 min, 4 °C). The supernatants were diluted ten times in a methanol/water mixture (70:30, v/v) and analyzed with a Vanquish Core liquid chromatographic system paired to an Exploris 120 quadrupole Orbitrap high-resolution mass spectrometer (both from Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany). Compounds were separated at 35 °C using a reversed-phase mode biphenyl Core–Shell column (Kinetex biphenyl, 100 × 2.1, 2.6 µm, Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA), eluted with 0.1% (v/v) formic acid in water (solvent A) and acetonitrile (solvent B), with the following gradient of solvent B: min 0–0.5, 5%; min 1.5, 15%; min 10, 40%; min 15, 70%; and min 16–19, 95%. The flow rate was 0.3 mL/min, and the injection volume was 1 µL. The use of reversed phase separation combined with the stationary phase biphenyl substituents promoted the appropriate separation of polar, mildly hydrophobic compounds with a focus on polyphenols and other functional phytometabolites part of specific families. Chromatographic stream was ionized via heated electrospray ionization (H-ESI) with a static spray voltage of −3.2 kV for negative and 3.5 kV for positive ions, while ion transfer tube and vaporizer temperature were set at 300 and 320 °C, respectively. Sheath gas flow and auxiliary gas flow were 50 and 10 arbitrary units, respectively. Analytes were scanned in polarity switching mode in the m/z range 120–1500 in full scan (FS) and data-dependent scanning mode (ddMS2), with mild trapping configuration and an expected chromatographic peak width of 7 s. The analyzer resolution was set at 120,000 (FWHM at m/z 200) for FS and data acquired in profile mode with a normalized AGC target of 100%. Separate methods for tandem MS experiments in ddMS2 were scheduled at the end of the batch through four overlapping acquisition segments (m/z 120–450, m/z 440–750, m/z 740–1050, and m/z 1040–1500). Within each experiment, a fragmentation spectrum was added to the chromatographic profile, isotopic pattern, and molecular formulas by combining positive (or negative) FS with ddMS2. For tandem MS acquisition, the settings were as follows: resolution of 60,000 (FWHM at m/z 200), isolation window of m/z 1.5 and 20, 45 and 60% normalized collision energy. Data profiles were acquired with an intensity threshold fixed at 50,000 (area counts); the dynamic exclusion was customized by considering a time window of 3.5 s and a mass tolerance within 5 ppm. A targeted mass exclusion list was manually annotated within the full scan range by injecting blank procedural samples and LC solvents. EASY-IC®, employing fluoranthene in both positive ion mode (m/z 202.0777 [M]+) and negative ion mode (m/z 202.0788 [M]−), was used to enhance mass centering and accuracy throughout the scan-to-scan acquisition. Profile data were collected using Xcalibur 4.5 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA); resolving power, response, and reproducibility of fragmentation spectra were checked by using Free Style software (v. 1.8, Thermo Fisher Scientific) during batch acquisition.

2.3. Bioinformatic Analysis of Untargeted Metabolomics Data

Raw files including procedural blank samples were loaded in Compound Discoverer v.3.3.1 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and analyzed using an untargeted metabolomic workflow suitable for the annotation and identification of the compounds even at low abundance, with a minimum number of scan points of 8 and a mass tolerance within 3 ppm. Before matching pure analytical standards in the form of a mzVault library and publicly available database spectral matching (flavonoid database, Arita lab) [18], signals were detected and grouped according to their analytical behavior. Spectral features, i.e., putative molecular formula assignment through isotopic pattern and exact masses, formulas, and fragmentation patterns were matched with free databases, including mzCloud (https://www.mzcloud.org), ChemSpider (https://www.chemspider.com), Phenol-Explorer (https://phenol-explorer.eu), and Natural Products Atlas (https://www.npatlas.org). Signals were filtered upon removal of the background, compounds without MS2 fragments, as well as a number of scans below 8 [19]. Molecular network was built according to the chemical nature of each compound, focusing on similar biotransformation and common fragmentation spectrum. Compounds were grouped into a neural network, in which each node represented a molecule, the size was linked to compound area, whereas the node color indicated the spectral library (light green for mzCloud or mzVault, dark green for other databases such as ChemSpider). Finally, the identified compounds were quantified by using calibration curves built with authentic reference standards in the range 0 (solvent blank) to 10 mg/L according to Table S1.

2.4. Eukaryotic Cell Assays

2.4.1. MTT Assay: Effect of R. tomentosum on Cell Viability

To evaluate R. tomentosum extract toxicity on eukaryotic cell lines, the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay was performed on two immortalized and two cancer cell lines. HaCaT (immortalized human keratinocytes) were from Innoprot (Biscay, Derio, Spain); HeLa (human cervical cancer cells), Balb/c-3T3 (immortalized murine fibroblasts), and SVT2 (virus 40-transformed murine fibroblasts) were obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA). Cells were cultured as previously described [20]. The MTT assay was performed by plating cells in 96-well plates at the following density: 2 × 103 cell/well for HaCaT and HeLa; 3 × 103 cell/well for Balb/c-3T3; and 1.5 × 103 cell/well for SVT2. Twenty-four hours after seeding, increasing concentrations of R. tomentosum extract (0.5–2%, v/v) were added to the cells for 48 h. At the end of the experiment, the MTT assay was performed [21]. Cell survival was expressed as the percentage of viable cells in the presence of the extract compared to the controls. Two groups of cells were used as controls, i.e., untreated cells and cells supplemented with the highest volume of hydroalcoholic buffer used (70% ethanol and 30% H2O, v/v).

2.4.2. DCDFA Assay: Protective Effect of R. tomentosum Extract on HaCaT Cells

For the DCFDA assay, HaCaT cells were plated and incubated as described previously [20]. The extract concentration used was 0.5% (v/v).

2.5. Bacterial Cells Assay

2.5.1. Antibacterial Activity of the R. tomentosum Extract

A broth microdilution assay was used to evaluate minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC). The following five plant-beneficial bacterial strains were used: Pseudomonas fluorescens, Paenibacillus sp., Bacillus amyloliquefaciens, Rhodococcus qingshengii, and Bacillus velenzensis; the following eight phytopathogens bacterial strains were tested: Pseudomonas cichorii, Pseudomonas syringae, Curtobacterium flaccumfaciens, Agrobacterium tumefaciens, Clavibacter michiganensis IPSP-001, Clavibacter michiganensis IPSP-002, Xanthomonas vesicatoria, and Xanthomonas campestris. All bacterial strains were obtained from the CNR-IPSP collection. A single colony of each bacterial strain was inoculated overnight at 28 °C in 5 mL of LB medium. Fifty µL of cultures of exponentially growing bacteria and increasing concentrations of R. tomentosum extract (up to 10%, v/v) were combined in a 96-well plate, with a final volume of 100 µL. Different antibiotics were used as positive controls as follows: ampicillin for R. qingshengii, B. velenzensis, and X. vesicatoria; streptomycin for B. amyloliquefaciens, P. syringae, X. campestris, and A. tumefaciens; kanamycin for P. cichorii; gentamycin for P. fluorescens, Paenibacillus sp.; tetracycline for C. flaccumfaciens, C. michiganensis IPSP-001, and C. michiganensis IPSP-002. After an overnight incubation at 28 °C, the optical density at 600 nm (O.D. 600 nm) of each mixture was measured using a multiplate reader GloMax Explorer (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Samples were then plated on LB-agar and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) was evaluated after an overnight incubation at 28 °C.

2.5.2. Effect of the R. tomentosum Extract on Bacterial Cell Proliferation

To evaluate bacterial cell proliferation, R. tomentosum extract was tested (0.5%, v/v) on the above-reported beneficial bacterial strains after incubation at 28 °C, for 24 h. O.D. at 600 nm was measured using a multiplate reader GloMax Explorer (Promega, Madison, WI, USA).

2.5.3. Fungal Spore Germination Assay

Two phytopathogenic fungi, Botrytis cinerea and Fusarium oxysporum and one biocontrol agent, Trichoderma atroviride AGR2, were tested. All fungal strains were obtained from the CNR-IPSP collection. For each fungus, 10 μL of 1 × 104 spore/mL spore suspension and 30 μL of potato dextrose broth (PDB) (Difco) were added in a 96 well-plate. R. tomentosum extract was tested up to 2.5% (v/v). In parallel, a hydroalcoholic solution (70%, v/v) was used as a buffer control. Volumes were adjusted (100 μL total volume) by adding distilled sterile water. Spore germination was analyzed after 20 h incubation using an Axiovert 5 digital inverted microscope (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). The percentage of well coverage was quantified using Zeiss software (Labscope 4.2.1). Each well was divided into three regions, and the germination values obtained from the three regions were averaged. This procedure was repeated for each technical replicate.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

For all the experiments, each batch was tested in at least three independent analyses, each carried out in triplicate. Results are presented as the mean value of three independent experiments (mean ± S.D.) and were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni (post hoc) test, using GraphPad Prism for Windows, version 6.01 (Dotmatics, CA, USA).

3. Results

3.1. LC-MS/MS Analysis of the R. tomentosum Hydroalcoholic Extract

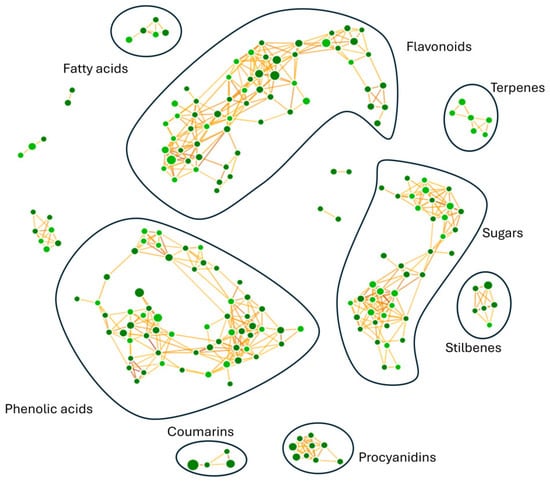

Untargeted metabolomic analysis provided a biochemical fingerprint of phytochemicals present in R. tomentosum hydroalcoholic extract. The optimization of the analytical workflow was the prerequisite for the annotation of chemical compounds of interest. Compound detection was carried out in negative polarity mode because of the chemical nature of the target analytes in the hydroalcoholic extract. Along with chromatographic separation and mass spectrometry configuration, the untargeted metabolomics workflow led to the annotation of 1526 compounds. Upon further processing, the number of metabolites was reduced to approximately 230 molecular species, as reported in Table S1, in which different levels of identification, accurate masses, chemical formulas, retention times, and spectra (diagnostic ions and reference fragments) are reported, in line with the metabolomics standard initiative [19]. Identified molecules were grouped based on their fragmentation patterns and predicted by biochemical transformations (glycosylation, methylation, hydration, dehydration, saturation, and oxidation) through a dedicated molecular network (Figure 1), highlighting compounds with a similarity score higher than 50%. Neural networks yielded several distinct clusters, with most of the molecules falling into flavonols, flavanols, hydroxybenzoic acid derivatives, sugars, hydroxycinnamic acid derivatives, terpenes, fatty acids, stilbenes, chalcones, and coumarins.

Figure 1.

Molecular network obtained for R. tomentosum hydroalcoholic extract. Phenolic acids, coumarins, sugars, terpenes, stilbenes, flavonoids, procyanidins, and fatty acids were identified as molecular classes of interest. Phenolic acids and flavonoids were the most represented classes. Compounds were grouped into a neural network, in which each node represents a distinct molecule; the size is linked to compound area, whereas the node color indicates the spectral library used (light green for mzCloud or mzVault, dark green for other databases such as ChemSpider).

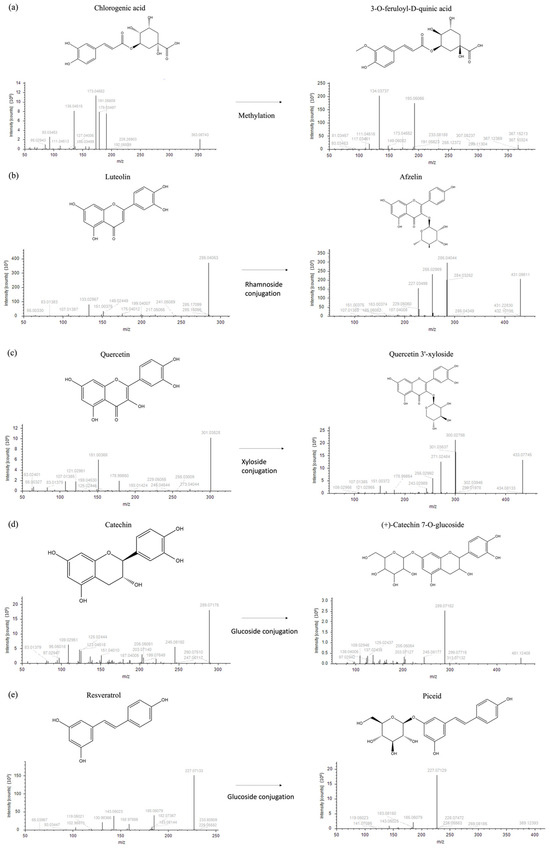

Each node is interjoined by different links, as a result of multiple iterative processes connecting compound fragmentation spectra and biochemical transformations typical of the chemical classes spotted in Figure 2. Such biochemical reactions represented the paradigm for the construction of the molecular network and provided the bases for compound grouping and their further characterization. Moving through phenolic acids, the methylation reaction linking fragmentation spectra of chlorogenic acid and 3-feruloyl-D-quinic was outlined (Figure 2a). Chlorogenic acid was characterized by the presence of the diagnostic fragment ions at m/z 173.045, 191.056, and 135.045, while 3-feruloyl-D-quinic acid exhibited the key ions at m/z 193.050 and 134.037. In Figure 2b–d, luteolin to afzelin, quercetin to quercetin 3′-xyloside, and catechin to catechin 7-O-glucoside, respectively, were described by the mean of enzymatic glycosylation reaction. Glycosylated compound spectra were characterized by an intense signal of fragment ions of the aglycone (m/z 285.040 for luteolin, 301.035 for quercetin, and 289.071 for catechin). In Figure 2e, glucoside conjunction of resveratrol into piceid was described. Both fragmentation spectra contained diagnostic fragment ions of resveratrol (m/z 227.071, 185.0607, and 143.0502), only differing for the presence of a hexose moiety (m/z 389.12393 and 227.071, respectively). In coumarin chemical classes, two examples of biotransformation were used to track molecular grouping. In Figure 2f,g, spectra reported the main fragment ions of aesculetin (m/z 177.019 and 133.029), which is the skeleton of all identified compounds. For triterpenoids, the oxidation of ursolic acid to corosolic acid was detailed (Figure 2h), emphasizing how compounds can be interconnected through oxidation reaction. Reduction in procyanidin A-type into procyanidin B-type was shown in Figure 2i. Procyanidin A type was characterized by typical fragment ions as m/z 285.040, 289.071, 125.024, 449.087, and 575.119, whereas procyanidin B type contained the following typical fragment ions: m/z 125.024, 289.071, 407.077, and 161.024.

Figure 2.

Fragmentation spectra and biochemical transformation of different compounds. (a) Methylation of chlorogenic acid to form 3-O-feruloyl-D-quinic acid; (b) conjugation of rhamnoside and luteolin to obtain afzelin; (c) conjugation of xyloside and quercetin to form quercetin 3′-xyloside; (d) conjugation of glucoside and catechin to obtain catechin 7-O-glucoside; (e) conjugation of glucoside and resveratrol to form piceid; (f) conjugation of glucoside and aesculetin to obtain aesculin; (g) oxidation and methylation of coumaroyl aesculin to form feruloyl aesculin; (h) oxidation of ursolic acid to obtain corosolic acid; and (i) procyanidin B type formation upon reduction of procyanidin A.

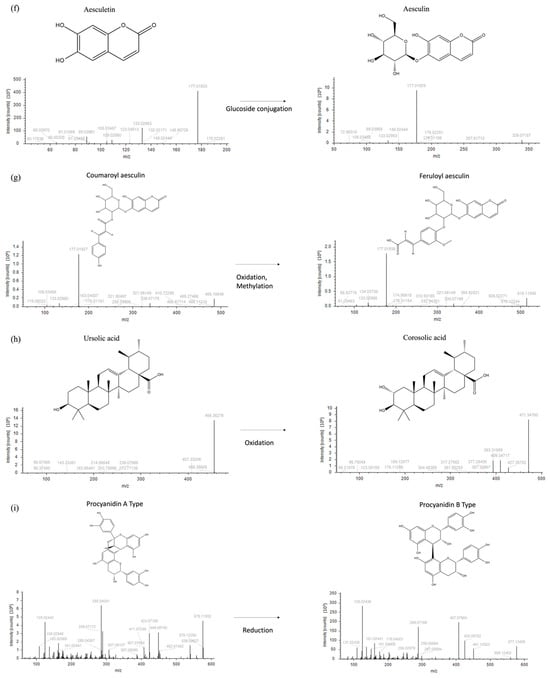

Besides the intrinsic number of annotated compounds within each chemical class, the molecular network provided information for compound assignment and identification through pure analytical standards. Table 1 reports the mass spectral identification of compounds based on their relative abundance (only compounds with a relative abundance > 0.5% are reported). Interestingly, coumarins were the most represented class of molecules identified in the extract (24%), followed by flavonols (20%), flavanols (11%), hydroxybenzoic acid derivatives and sugars (9%), hydroxycinnamic acid derivatives and terpenes (6%), fatty acids (5%), stilbenes (3%), and chalcones (1%). Focusing on coumarins as the most representative chemical class, several compounds were annotated, and their identity was tentatively confirmed through fragmentation spectra and accurate masses. Different derivatives (coumaroyl aesculin, feruloyl aesculin, and caffeoyl aesculin) were tentatively identified here for the first time based on typical aesculin fragments ions (m/z 177.01929, 176.01155, and 339.07190). These molecules were characterized by a hydroxycinnamic acid derivative (p-coumaric acid, ferulic acid, and caffeic acid, respectively) O-linked to aesculin through the glycoside moiety, as shown in Figure 3 and Figure S1, with the latter ones reporting the corresponding tandem mass spectra. As reported in Table S1, two additional unknown aesculin derivatives were detected in the hydroalcoholic extract; their tentative molecular assignment was based on the observation of fragment ions that were identical to those of aesculin and its aglycone form.

Table 1.

LC-MS/MS spectral analysis of phytochemicals present in R. tomentosum hydroalcoholic extract. Tentatively identified species are reported, together with their formula, calculated M.W., m/z ratio, retention time, abundance, and relative concentration. The relative abundance for each class of molecules refers to the samples reported in Table S1.

Figure 3.

Aesculin derivatives. Aesculin derivatives (coumaroyl aesculin, feruloyl aesculin, and caffeoyl aesculin) and tentative assignments according to fragmentation spectra and molecular network with biotransformation and candidates screening. See Figure S1 for details on fragmentation spectra.

The relative concentration (mg/L) of the identified compounds in the hydroalcoholic extract was obtained using pure chemical standards for different chemical classes (Table 1 and Table S1). Catechin, luteolin, and naringenin were used as standards for flavonoids, whereas 3,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid, caffeic acid, and chlorogenic acid were utilized for phenolic acids; 3,3′,4′,5-tetrahydroxystilbene was used as a standard compound for stilbenes, while asiatic acid, agnuside, and abscisic acid were utilized for terpenes and derivatives.

3.2. Biological Activity

3.2.1. Effect of R. tomentosum Hydroalcoholic Extract on Eukaryotic Cell Viability

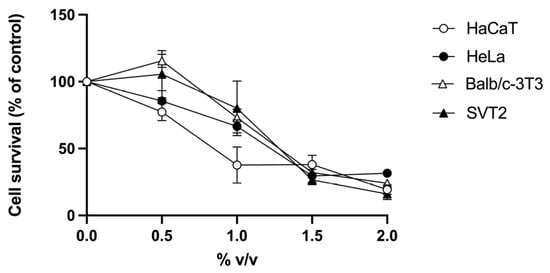

R. tomentosum hydroalcoholic extract was tested on two immortalized (human HaCaT keratinocytes and murine embryonic Balb/c-3T3 fibroblasts) and two cancer (human cervical HeLa cancer cells and virus 40-transformed murine SVT2 embryonic fibroblasts) cell lines. Cells were incubated with increasing concentrations of R. tomentosum extract (0.5–2%, v/v), and cell viability was evaluated by the MTT assay. As shown in Figure 4, a similar trend was observed for all the cell lines tested, with HaCaT being the most sensitive cells. From the MTT assay results, IC50 values were calculated (% v/v, Table 2). This parameter indicates the concentration of the extract causing 50% cell death and is related to the sensitivity of cells to the extract.

Figure 4.

Effect of R. tomentosum extract on cell viability. HaCaT (white circles), HeLa (black circles), Balb/c-3T3 (white triangles), and SVT2 (black triangles) cells were incubated with increasing concentrations of the extract (0.5–2%, v/v) for 48 h. Cell survival is reported as a function of the extract tested. Data shown are means ± S.D. of three independent experiments.

Table 2.

IC50 values (% v/v) of R. tomentosum hydroalcoholic extract on eukaryotic cells. Data shown are mean values ± S.D. of three independent experiments.

3.2.2. Protective Effect of R. tomentosum Hydroalcoholic Extract on UVA-Stressed HaCaT Cells

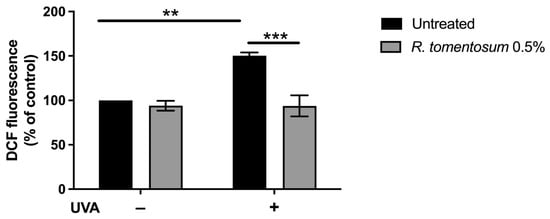

Hydroalcoholic plant extracts contain antioxidant molecules that can find application in different fields [22,23,24]. Thus, the possible protective effect of R. tomentosum extract against oxidative stress was tested using HaCaT cells, as keratinocytes are normally exposed to external stimuli, such as sun UVA radiation. To this purpose, 0.5% (v/v) hydroalcoholic extract was chosen for the analysis, as it represents the highest concentration without toxic effect on HaCaT cells (MTT assay). Cells were incubated with the extract for 2 h, and then stressed by an UVA lamp, typically used in the nail industry [25]. H2-DCFDA probe was added, and intracellular ROS levels were measured. As shown in Figure 5, upon UVA stress, control cells showed a significant increase in ROS levels with respect to non-stressed cells (150%, black bars, p < 0.01). When cells were incubated with R. tomentosum extract and then exposed to UVA radiations, a significant inhibition in ROS production was observed (93%, p < 0.001). No alteration in ROS levels was observed when HaCaT cells were incubated in the presence of the extract but in the absence of irradiation.

Figure 5.

Antioxidant activity of R. tomentosum hydroalcoholic extract determined by DCFDA assay. HaCaT cells were incubated in the presence of 0.5% (v/v) of the extract for 2 h, stressed with a UVA lamp (100 J/cm2), and intracellular ROS level was measured. ROS production was expressed as a percentage of the intensity of DCF fluorescence compared to untreated cells. Black bars refer to control cells, and gray bars refer to cells incubated with the extract, in the absence (−) or presence (+) of UVA stress. Data shown are mean values ± S.D. of three independent experiments. ** indicates p < 0.01, and *** indicates p < 0.001. The lines above the bars indicate the two samples compared for statistical analysis.

3.2.3. Evaluation of the Antibacterial Activity of R. tomentosum Hydroalcoholic Extract

Many of the molecules tentatively identified in R. tomentosum extract are related to antibacterial activity often associated with the activity of these compounds against human pathogenic bacteria and not on phytopathogens [26,27,28]. Thus, to further explore the biological activity of the extract, its potential antibacterial properties towards different beneficial and pathogenic phytobacteria were tested via broth microdilution assay. After an overnight bacterial inoculum, cells were plated in a 96-well plate in the presence of increasing concentrations of the hydroalcoholic extract (1–10%, v/v), and MIC values were evaluated by spectrophotometric measurements. As shown in Table 3, R. tomentosum extract inhibited the growth of two phytopathogens, i.e., C. michiganensis IPSP-001 and C. michiganensis IPSP-002, and of the beneficial B. velenzensis strain. The same MIC values (10%, v/v) were measured for C. michiganensis IPSP-002 and B. velenzensis, whereas an MIC value of 2.5% (v/v) was obtained for C. michiganensis IPSP-001. The MBC values of the R. tomentosum extract were determined by transferring samples from the broths utilized for MIC determination onto solid medium. The measured MBC values were higher than the maximum concentration tested (10%, v/v) for all bacterial strains analyzed (Table 3), suggesting a bacteriostatic but not bactericidal effect on C. michiganensis IPSP-001, C. michiganensis IPSP-002, and B. velenzensis.

Table 3.

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC, % v/v) and minimal bactericide concentration (MBC, % v/v). Values were determined for R. tomentosum hydroalcoholic extract tested on a panel of beneficial and phytopathogen bacterial strains. The following different antibiotics were used as positive control: ampicillin (a), streptomycin (s), kanamycin (k), gentamycin (g), and tetracycline (t). Values were obtained from a minimum of three independent experiments.

3.2.4. Effect of the R. tomentosum Hydroalcoholic Extract on Bacterial Cell Proliferation

Once proved that the extract did not show any inhibitory effect on beneficial bacterial strains, with the exception of B. velenzensis, other beneficial bacterial strains were incubated with 0.5% (v/v) R. tomentosum extract to evaluate its possible use as a bacterial growth stimulant. This concentration was selected because of its biocompatibility (Figure 4) and its antioxidant activity (Figure 5) on eukaryotic cells. Results showed that the R. tomentosum extract notably stimulated B. amyloliquefaciens growth by 42% after 24 h incubation, whereas it had no effect on the other tested bacterial strains.

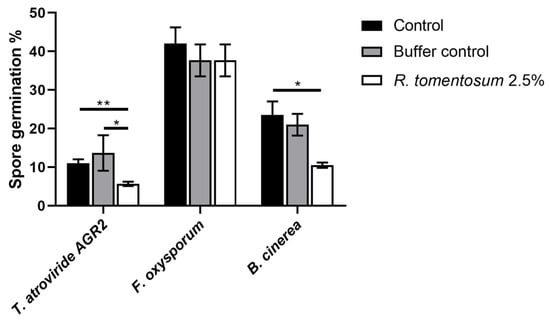

3.2.5. Effect of R. tomentosum Hydroalcoholic Extract on Fungal Spore Germination

The R. tomentosum extract was tested on the spores of the following three fungi: Trichoderma atroviride AGR2, Fusarium oxysporum, and Botrytis cinerea. T. atroviride AGR2 is a beneficial fungus, whereas F. oxysporum and B. cinerea are phytopathogens. Spore germination was measured after 20 h of incubation in the presence or absence of the extract (up to 2.5%, v/v), as described in Section 2. The antifungal effect was observed when spores were incubated with 2.5% (v/v) of the extract, as reported in Figure 6. The hydroalcoholic buffer (without the extract) was tested at the same concentration (2.5%, v/v) and did not show any significant toxicity on the three analyzed fungi. Surprisingly, T. atroviride AGR2 and B. cinerea spore germination was significantly affected by R. tomentosum extract (about 50% inhibition), whereas no effect on F. oxysporum spore germination was observed in the presence of the extract.

Figure 6.

Effect of R. tomentosum hydroalcoholic extract on spore germination. T. atroviride AGR2, F. oxysporum, and B. cinerea spore germination after 20 h of incubation in presence of the R. tomentosum hydroalcoholic extract. A total of 2.5% (v/v) of the extract and the hydroalcoholic buffer were used. Microscopic analyses were performed using an inverted microscope Zeiss Axiovert 5 digital. Data shown are mean values ± S.D. of three independent experiments. * indicates p < 0.05; ** indicates p < 0.01.

4. Discussion

The aromatic plant R. tomentosum represents a sustainable source of bioactive compounds with several applications in multiple fields. In this study, a mass spectrometry characterization of a commercially available R. tomentosum hydroalcoholic extract tackled its chemical composition, providing a molecular fingerprinting of the extract. According to the main results reported for other Rhododendron species, flavanols, flavonols, hydroxybenzoic acids, hydroxycinnamic acids, coumarins, stillbenes, fatty acids, sugars, organic acids, and terpens represented the main constituents. In line with the chemical profile here summarized, afzelin, luteolin, phloretin (flavonoids), dihydromyricetin (flavanonols), 1-O-vanilloyl-beta-D-glucose (glucosides), sinapinate (alkaloids), 3-p-coumaroylquinic acid (hydroxynnamic acids), scopoline (coumarins), (10E)-9,13-dihydroxy-10-octadecenoic acid (fatty acids), and asiatic acid (terpenoids) were outlined as key biomarkers in R. adamsii, R. lapponicum, and R. burjaticum [29]. Other flavonoids, such as quercetin 3-(6″-p-hydroxybenzoylgalactoside), naringenin, and gallocatechin were detected in R. dauricum (leaves), R. hainanense (aerial parts), R. molle (fruits) [16], whereas in quercetin 3′-xyloside response paralleled the one reported in R. sichotense leaves and stems [30]. Similarly, the concentrations of quercetin and its derivatives, catechin, procyanidins, and chlorogenic acid, were at the same order of magnitude as reported in R. groenlandicum and tomentosum [31]. In R. tomentosum leaves and twigs, diosmetin, procyanidins (flavonoids), and ellagic acid (catechols) were identified as the main compounds upon supercritical CO2 extraction [32]. In the present study, several phytochemicals belonging to flavonoids, such as luteolin, 3-methoxyluteolin, and newly reported aesculin derivatives (coumarins), were identified, for the first time in R. tomentosum tips of twigs, thus expanding its annotated chemical profile. To the best of our knowledge, luteolin has been detected only in R. luteum sweet leaf extracts, at low concentration [33]. Of note, coumaroyl-, feruloyl-, and caffeoyl aesculin (aesculin-hydroxycinnamic acid derivatives) were identified for the first time in this study, highlighting the possibility that the glycoside moiety of aesculin might be the target for biochemical processes leading to the formation of coumaroyl aesculin, feruloyl aesculin, and caffeoyl aesculin as part of the metabolites arising from the interplay between p-coumaroyl-coenzyme A and UDP-glucose-dependent glucosyltransferases [34].

Flavonoids and coumarins are well-known antioxidants, which act by different mechanisms of action [35]. Noteworthy, this is the first report on the protective effect of R. tomentosum hydroalcoholic extract against UVA-induced oxidative stress on a cell-based model. Previously, R. tomentosum and R. przewalskii extracts were successfully tested only by in vitro analyses, with R. przewalskii extract effective also on RAW 264.7 cells, and the antioxidant activity mainly attributed to the presence of flavonoids [17,36]. Additionally, quercetin and luteolin exhibit anti-inflammatory and cytoprotective activities through modulation of NF-κB, MAPK, and COX/LOX pathways, as well as activation of the Nrf-2/Keap1 pathway [37], mechanisms involved in different cell-defense response. In R. tomentosum hydroalcoholic extract, coumarins are the most represented metabolites, and their abundance likely contributes to several of the biological effects described in this study. Molecules belonging to coumarins, such as scopoletin, aesculin, and fraxetin, are widely recognized for their antioxidant, antimicrobial, and immunomodulatory properties [38]. Beyond direct biological activity, coumarins have emerged as key mediators of plant–microbe interactions. Recent studies have demonstrated that they shape the rhizosphere microbiome by selectively inhibiting pathogens while promoting beneficial taxa, including Pseudomonas and Bacillus species, due to their redox chemistry and metal-mobilizing capacity [39,40]. Recent work expanded their ecological role, showing that coumarins produced by pepper roots can restructure the soil microbiome to enhance pesticide-degrading bacteria, and simultaneously improve fruit nutritional quality [41]. This evidence reinforces the idea that coumarins are key modulators of microbial chemical signals, promoting plant protection and detoxification, in line with our results. Indeed, coumarins impair microbial quorum sensing, inhibit essential enzymes, and destabilize fungal cell walls [38]. These mechanistic insights provide a plausible explanation for the moderate bacteriostatic effects observed against C. michiganensis and the suppression of spore germination in B. cinerea and T. atroviride AGR2. Moreover, R. tomentosum extract stimulated the growth of the beneficial B. amyloliquefaciens, in agreement with Wang and coworkers, who ascribed the dual behavior to the presence of coumarins in R. tomentosum extract [41]. Such activities are particularly relevant for agricultural applications, where the ability to favor plant-beneficial bacteria while inhibiting pathogens is highly desirable. Moreover, these findings suggest a potential role for such extracts as supportive tools for modern agriculture.

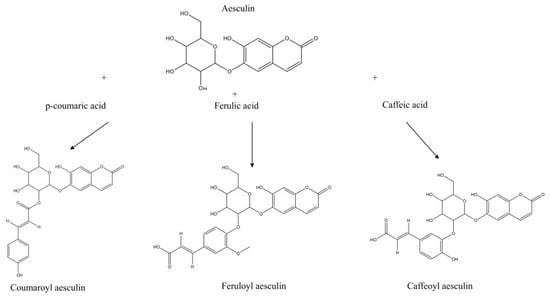

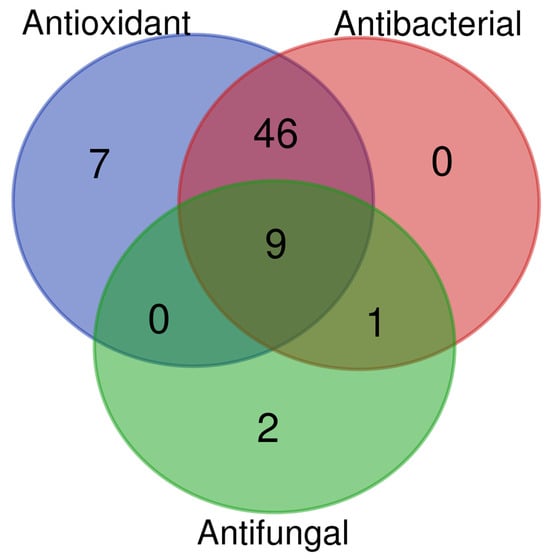

In Figure 7, the identified metabolites were clustered according to their antioxidant, antibacterial, and antifungal properties, based on functional data available in the literature (https://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/Venn/, accessed on 3 November 2025). Most of the metabolites showed antioxidant and antibacterial activities, while a small subset of the identified metabolites (nine), including caffeic acid [42], gallic acid [43], quercetin [28,44], catechin, and scopoletin [26], exhibited all three activities.

Figure 7.

Venn diagram generated from the literature data analysis. Metabolites were classified based on their antioxidant, antibacterial, and antifungal activities.

5. Conclusions

This study recognizes R. tomentosum as a source of bioactive compounds, emphasizing the critical need to connect chemical composition to functional properties in phytochemical research. Reporting the first-ever tentative identification of novel aesculin derivatives, this paper extends the phytochemical profile previously attributed to this species, presenting new insights into R. tomentosum biochemical signature. By integrating metabolomic profile with assays evaluating the antioxidant, antibacterial, and antifungal potential, this work provides a framework for bridging the chemical composition of the plant extract to its functional properties. The proposed approach highlights chemical and biological information and establishes a foundation for their potential application in sustainable agriculture.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/biom16010110/s1, Table S1: Tentatively identified species in the R. tomentosum hydroalcoholic extract determined by LC-MS/MS and bioinformatic analysis; Figure S1: Tandem mass spectra of caffeoyl aesculin, coumaroyl aesculin, and feruloyl aesculin.

Author Contributions

G.S.: Investigation, Formal Analysis, Data Curation, Writing—Original Draft, and Writing—Review and Editing; P.I.: Investigation, Data Curation, Formal Snalysis, Methodology, Writing—Original Draft, and Writing—Review and Editing; S.D.P.: Investigation, Methodology, and Software; R.F.: Software, Validation; S.C.: Resources, Software; A.S.: Funding Acquisition, Writing—Review and Editing; A.D.T.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data Curation, Supervision, Writing—Original Draft, and Writing—Review and Editing; D.M.M.: Conceptualization, Supervision, Project Administration, Writing—Original Draft, and Writing—Review and Editing; V.R.: Funding Acquisition, Writing—Review and Editing; D.D.: Methodology, Writing—Review and Editing; M.M.M.: Conceptualization, Project Administration, Supervision, Writing—Original Draft, and Writing—Review and Editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Recovery and Resilience Plan of Italian Ministry of University and Research (NRRP) funded by the European Union-Next Generation EU: Mission 4, Component 2, Investment 1.3, project “Research and innovation network on food and nutrition Sustainability, Safety and Security-Working ON Foods (ON-FOODS)”, PE00000003 and project “One Health Basic and Translational Research Actions addressing Unmet Needs on Emerging Infectious Diseases (IN-FACT)”, PE00000007; Mission 4, Component 2, Investment 1.4, project “National Research Centre for Agricultural Technologies (AGRITECH), CN00000022; Mission 4 Component 2 Investment 3.1 project “Italian Integrated Environmental Research Infrastructures System (ITINERIS)”, IR0000032, CUP n. B53C22002150006. This work was developed during the PhD program in Biotechnology at the University of Naples Federico II, 38th cycle, with the support of a scholarship co-funded by Ministerial Decree No. 352 of 9 April 2022, by NRRP Mission 4, Component 2, Investment 3.3, and by the company Ce.M.O.N. S.r.l.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated during this study are included in this published article and its Supplementary information file.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Vincenzo Rocco was employed by the company Ce.M.O.N. S.r.l. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LC-MS/MS | Liquid Chromatography high-resolution Tandem Mass Spectrometry |

| MTT | 3-(4,5- dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide |

| DCFDA | DiChlorodihydroFluorescein DiAcetate |

| M.W. | Molecular Weight |

| IC50 | Half-maximal Inhibitory Concentration |

| UVA | UltraViolet A |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| DCF | 2′,7′-Dichlorofluorescein |

| MIC | Minimum Inhibitory Concentration |

| MBC | Minimum Bactericidal Concentration |

| ATCC | American Type Culture Collection |

| O.D. | Optical Density |

| CNR-IPSP | National Research Council-Institute for Sustainable Plant Protection |

References

- Khursheed, A.; Rather, M.A.; Jain, V.; Wani, A.R.; Rasool, S.; Nazir, R.; Malik, N.A.; Majid, S.A. Plant Based Natural Products as Potential Ecofriendly and Safer Biopesticides: A Comprehensive Overview of Their Advantages over Conventional Pesticides, Limitations and Regulatory Aspects. Microb. Pathog. 2022, 173, 105854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godlewska, K.; Ronga, D.; Michalak, I. Plant Extracts-Importance in Sustainable Agriculture. Ital. J. Agron. 2021, 16, 1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergonzi, M.C.; Heard, C.M. Bioactive Molecules from Plants: Discovery and Pharmaceutical Applications. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Hyun, C. Natural Products for Cosmetic Applications. Molecules 2023, 28, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Wen, K.S.; Ruan, X.; Zhao, Y.X.; Wei, F.; Wang, Q. Response of Plant Secondary Metabolites to Environmental Factors. Molecules 2018, 23, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichling, J. Antiviral and Virucidal Properties of Essential Oils and Isolated Compounds—A Scientific Approach. Planta Med. 2021, 88, 587–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawood, M.A.O.; El Basuini, M.F.; Zaineldin, A.I.; Yilmaz, S.; Hasan, M.T.; Ahmadifar, E.; El Asely, A.M.; Abdel-Latif, H.M.R.; Alagawany, M.; Abu-Elala, N.M.; et al. Antiparasitic and Antibacterial Functionality of Essential Oils: An Alternative Approach for Sustainable Aquaculture. Pathogens 2021, 10, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dampc, A.; Luczkiewicz, M. Rhododendron tomentosum (Ledum palustre). A Review of Traditional Use Based on Current Research. Fitoterapia 2013, 85, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judzentiene, A.; Budiene, J.; Svediene, J.; Garjonyte, R. Toxic, Radical Scavenging, and Antifungal Activity of Rhododendron tomentosum H. Essential Oils. Molecules 2020, 25, 1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Liu, W.; Yuan, T. Sesquiterpenes from Rhododendron nivale and Their Anti-Inflammatory Activity. Chem. Biodivers. 2022, 19, e202200856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.; Yang, M.; Li, T.; Sun, Y.; Dong, Z.; Zhan, H.; Chen, M.; Chen, M. Research Progress on Heteroterpene and Meroterpenoid Compounds from the Rhododendron Genus and Their NMR Characterization and Biological Activity. Front. Pharma 2025, 16, 1584962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raal, A.; Orav, A.; Gretchushnikova, T. Composition of the Essential Oil of the Rhododendron tomentosum Harmaja from Estonia. Nat. Prod. Res. 2014, 28, 1091–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gretšušnikova, T.; Järvan, K.; Orav, A.; Koel, M. Comparative Analysis of the Composition of the Essential Oil from the Shoots, Leaves and Stems the Wild Ledum palustre L. from Estonia. Procedia Chem. 2010, 2, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhu, W.; Liu, H.; Wu, G.; Song, M.; Yang, B.; Yang, D.; Wang, Q.; Kuang, H. Simultaneous Determination of Aesculin, Aesculetin, Fraxetin, Fraxin and Polydatin in Beagle Dog Plasma by UPLC-ESI-MS/MS and Its Application in a Pharmacokinetic Study after Oral Administration Extracts of Ledum palustre L. Molecules 2018, 23, 2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, P.; Saleem, A.; Dunford, A.; Guerrero-Analco, J.; Walshe-Roussel, B.; Haddad, P.; Cuerrier, A.; Arnason, J.T. Seasonal Variation of Phenolic Constituents and Medicinal Activities of Northern Labrador Tea, Rhododendron Tomentosum Ssp Subarcticum, an Inuit and Cree First Nations Traditional Medicine. Planta Med. 2011, 77, 1655–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Su, H.; Peng, X.; Bi, H.; Qiu, M. An Updated Review of the Genus Rhododendron since 2010: Traditional Uses, Phytochemistry, and Pharmacology. Phytochemistry 2024, 217, 113899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukhtenko, H.; Bevz, N.; Konechnyi, Y.; Kukhtenko, O.; Jasicka-Misiak, I. Spectrophotometric and Chromatographic Assessment of Total Polyphenol and Flavonoid Content in Rhododendron Tomentosum Extracts and Their Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activity. Molecules 2024, 29, 1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukushima, A.; Takahashi, M.; Nagasaki, H.; Aono, Y.; Kobayashi, M.; Kusano, M.; Saito, K.; Kobayashi, N.; Arita, M. Development of RIKEN Plant Metabolome MetaDatabase. Plant Cell Physiol. 2022, 63, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumner, L.W.; Amberg, A.; Barrett, D.; Beale, M.H.; Beger, R.; Daykin, C.A.; Fan, T.W.-M.; Fiehn, O.; Goodacre, R.; Griffin, J.L.; et al. Proposed Minimum Reporting Standards for Chemical Analysis. Metabolomics 2007, 3, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imbimbo, P.; Romanucci, V.; Pollio, A.; Fontanarosa, C.; Amoresano, A.; Zarrelli, A.; Olivieri, G.; Monti, D.M. A Cascade Extraction of Active Phycocyanin and Fatty Acids from Galdieria phlegrea. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 103, 9455–9464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arciello, A.; De Marco, N.; Del Giudice, R.; Guglielmi, F.; Pucci, P.; Relini, A.; Monti, D.M.; Piccoli, R. Insights into the Fate of the N-Terminal Amyloidogenic Polypeptide of ApoA-I in Cultured Target Cells. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2011, 15, 2652–2663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalvand, H.; Hamdi, S.M.M.; Kotanaee, F.N.; Ahmadvand, H. Phytochemicals Analysis and Antioxidant Potential of Hydroalcoholic Extracts of Fresh Fruits of Pistacia atlantica and Pistacia khinjuk. Plant Sci. Today 2024, 11, 513–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumaiya, S.; Siddiqui, A.; Chaudhary, S.S.; Aslam, M.; Ahmad, S.; Ansari, M.A. Isolation and Characterization of Bioactive Components from Hydroalcoholic Extract of Cymbopogon Jwarancusa (Jones) Schult. to Evaluate Its Hepatoprotective Activity. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2024, 319, 117185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, N.C.; Cabeça, C.L.S.; Siciliano, P.L.M.; Pereira, B.C.; Zorzenon, M.R.T.; Dacome, A.S.; Souza, F.d.O.; Pilau, E.J.; Enokida, M.K.; de Oliveira, A.R.; et al. Methanolic and Hydroalcoholic Extract of Stevia Stems Have Antihyperglycemic and Antilipid Activity. Food Biosci. 2024, 58, 103690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petruk, G.; Raiola, A.; Del Giudice, R.; Barone, A.; Frusciante, L.; Rigano, M.M.; Monti, D.M. An Ascorbic Acid-Enriched Tomato Genotype to Fight UVA-Induced Oxidative Stress in Normal Human Keratinocytes. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2016, 163, 284–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antika, L.D.; Tasfiyati, A.N.; Hikmat, H.; Septama, A.W. Scopoletin: A Review of Its Source, Biosynthesis, Methods of Extraction, and Pharmacological Activities. Z. Naturforsch. Sect. C J. Biosci. 2022, 77, 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, K.; Ou, J.; Huang, J.; Ou, S. P-Coumaric Acid and Its Conjugates: Dietary Sources, Pharmacokinetic Properties and Biological Activities. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2016, 96, 2952–2962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, W.; Qi, W.; Xiong, D.; Long, M. Quercetin: Its Antioxidant Mechanism, Antibacterial Properties and Potential Application in Prevention and Control of Toxipathy. Molecules 2022, 27, 6545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chernonosov, A.A.; Karpova, E.A.; Karakulov, A.V. Metabolomic Profiling of Three Rhododendron Species from Eastern Siberia by Liquid Chromatography with High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2023, 157, 622–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razgonova, M.; Zakharenko, A.; Ercisli, S.; Grudev, V.; Golokhvast, K. Comparative Analysis of Far East Sikhotinsky Rhododendron (Rh. sichotense) and East Siberian Rhododendron (Rh. adamsii) Using Supercritical CO2-Extraction and HPLC-ESI-MS/MS Spectrometry. Molecules 2020, 25, 3774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vengrytė, M.; Raudonė, L. Phytochemical Profiling and Biological Activities of Rhododendron Subsect. Ledum: Discovering the Medicinal Potential of Labrador Tea Species in the Northern Hemisphere. Plants 2024, 13, 901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razgonova, M.P.; Zakharenko, A.M.; Golokhvast, K.S. Investigation of the Supercritical CO2 Extracts of Wild Ledum palustre L. (Rhododendron tomentosum Harmaja) and Identification of Its Metabolites by Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Russ. J. Bioorganic Chem. 2023, 49, 1645–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łyko, L.; Olech, M.; Nowak, R. LC-ESI-MS/MS Characterization of Concentrated Polyphenolic Fractions from Rhododendron luteum and Their Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidant Activities. Molecules 2022, 27, 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, T. Phenylpropanoid Biosynthesis. Mol. Plant 2010, 3, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heim, K.E.; Tagliaferro, A.R.; Bobilya, D.J. Flavonoid Antioxidants: Chemistry, Metabolism and Structure-Activity Relationships. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2002, 13, 572–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.; He, J.; Miao, X.; Guo, X.; Shang, X.; Wang, W.; Li, B.; Wang, Y.; Pan, H.; Zhang, J. Multiple Biological Activities of Rhododendron przewalskii Maxim. Extracts and UPLC-ESI-Q-TOF/MS Characterization of Their Phytochemical Composition. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 599778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aggarwal, D.; Chaudhary, M.; Mandotra, S.K.; Tuli, H.S.; Chauhan, R.; Joshi, N.C.; Kaur, D.; Dufossé, L.; Chauhan, A. Anti-Inflammatory Potential of Quercetin: From Chemistry and Mechanistic Insight to Nanoformulations. Curr. Res. Pharmacol. Drug Discov. 2025, 8, 100217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadati, F.; Modarresi Chahardehi, A.; Jamshidi, N.; Jamshidi, N.; Ghasemi, D. Coumarin: A Natural Solution for Alleviating Inflammatory Disorders. Curr. Res. Pharmacol. Drug Discov. 2024, 7, 100202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stringlis, I.A.; de Jonge, R.; Pieterse, C.M.J. The Age of Coumarins in Plant–Microbe Interactions. Plant Cell Physiol. 2019, 60, 1405–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Xu, J.; Li, Y.; He, Y.; Yang, Y.; Liu, D.; Wu, C. Effects of Coumarin on Rhizosphere Microbiome and Metabolome of Lolium multiflorum. Plants 2023, 12, 1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, Z.; Hu, Z.; Sun, R.; Li, D. Plant Coumarin Metabolism—Microbe Interactions: An Effective Strategy for Reducing Imidacloprid Residues and Enhancing the Nutritional Quality of Pepper. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 354–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aijaz, M.; Keserwani, N.; Yusuf, M.; Ansari, N.H.; Ushal, R.; Kalia, P. Chemical, Biological, and Pharmacological Prospects of Caffeic Acid. Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem. 2023, 13, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wianowska, D.; Olszowy-Tomczyk, M. A Concise Profile of Gallic Acid—From Its Natural Sources through Biological Properties and Chemical Methods of Determination. Molecules 2023, 28, 1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, D.; Wang, T.; Long, M.; Li, P. Quercetin: Its Main Pharmacological Activity and Potential Application in Clinical Medicine. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 2020, 8825387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.