1. Introduction

Lipid metabolism includes the synthesis, storage, transport, and breakdown of lipids within cells—processes that are vital for maintaining human health [

1]. The degradation of lipids, a key part of this system, occurs mainly through lipolysis, lipophagy, and β-oxidation. Central to this process are lipid droplets (LDs), which serve as the main intracellular storage organelles for neutral lipids such as cholesteryl esters and triglycerides. They fulfill essential cellular metabolic requirements including lipid storage, energy metabolism, fatty acid transport, and signal transduction [

2]. Dysregulated lipid metabolism contributes to various metabolic disorders including obesity, type 2 diabetes, fatty liver disease, and cardiovascular diseases [

3,

4,

5], which pose serious threats to human health. Therefore, investigating the different pathways of intracellular lipid droplet degradation is of great importance.

Photo-biomodulation therapy (PBMT) is a technique that uses light radiation from visible to near-infrared wavelengths to influence biological tissues. Due to its non-invasive nature, safety, portability, ease of use, and low cost, PBMT is being increasingly adopted in clinical practice. Compared to traditional red light therapy, blue light is gaining attention for its potential in photo-biomodulation. Research showed that blue light in the 400–470 nm range has demonstrated intrinsic antibacterial properties [

6], which can disrupt bacterial cell membranes and is utilized in treating acne. In human dermal fibroblasts, blue light exposure has been observed to reduce cell proliferation and metabolic activity [

7], and high doses can also decrease fibroblast migration [

8], suggesting potential benefits for managing psoriasis [

9]. Additionally, Bauer J found that blue light serves as a primary treatment for neonatal jaundice, where it breaks down bilirubin through a photochemical reaction to alleviate symptoms [

10]. Furthermore, low-dose 465 nm blue light has been shown to suppress the proliferation and migration of papillary thyroid carcinoma cells [

11]. Importantly, the biological effects of blue light are not isolated events; rather, they are closely associated with cellular photoreceptors, such as opsin 3 (Opn3).

Opn3 is a light-sensitive protein located on the cell membrane. It acts as a non-visual photoreceptor by detecting light in tissues beyond the eyes [

12]. This protein is highly expressed in the brain and testes [

13] and is also found in other organs including the liver, heart, kidneys, and pancreas [

14]. Meanwhile, Opn3 exhibits sensitivity to blue light around 480 nm [

15]. Upon light stimulation, it activates intracellular signaling pathways, enabling it to mediate a range of non-visual, light-induced physiological processes. For instance, one study reported that accelerated wound healing following blue light exposure may be linked to a corresponding increase in Opn3 expression [

16]. In another context, blue light activation of Opn3 triggers a calcium-dependent signaling cascade. This leads to MITF phosphorylation, which in turn increases the levels of tyrosinase and dopachrome tautomerase, thereby promoting melanin synthesis [

17]. Interestingly, Opn3 also appears to play a regulatory role in adipose tissue. Research by Nayak et al. demonstrated that in mouse fat cells, Opn3 activation by blue light promotes lipolysis, a process that involves the accelerated phosphorylation of hormone-sensitive lipase. Furthermore, mice lacking the Opn3 gene showed a reduction in thermogenesis, indicating its importance in heat production [

15].

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (Pparα) is a nuclear receptor that plays a central role in fatty acid metabolism. It is predominantly expressed in tissues like the liver and kidneys. Studies have shown that Pparα plays a significant role in numerous physiological processes, such as improving metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) [

18], enhancing immune responses in immune cells [

19,

20].

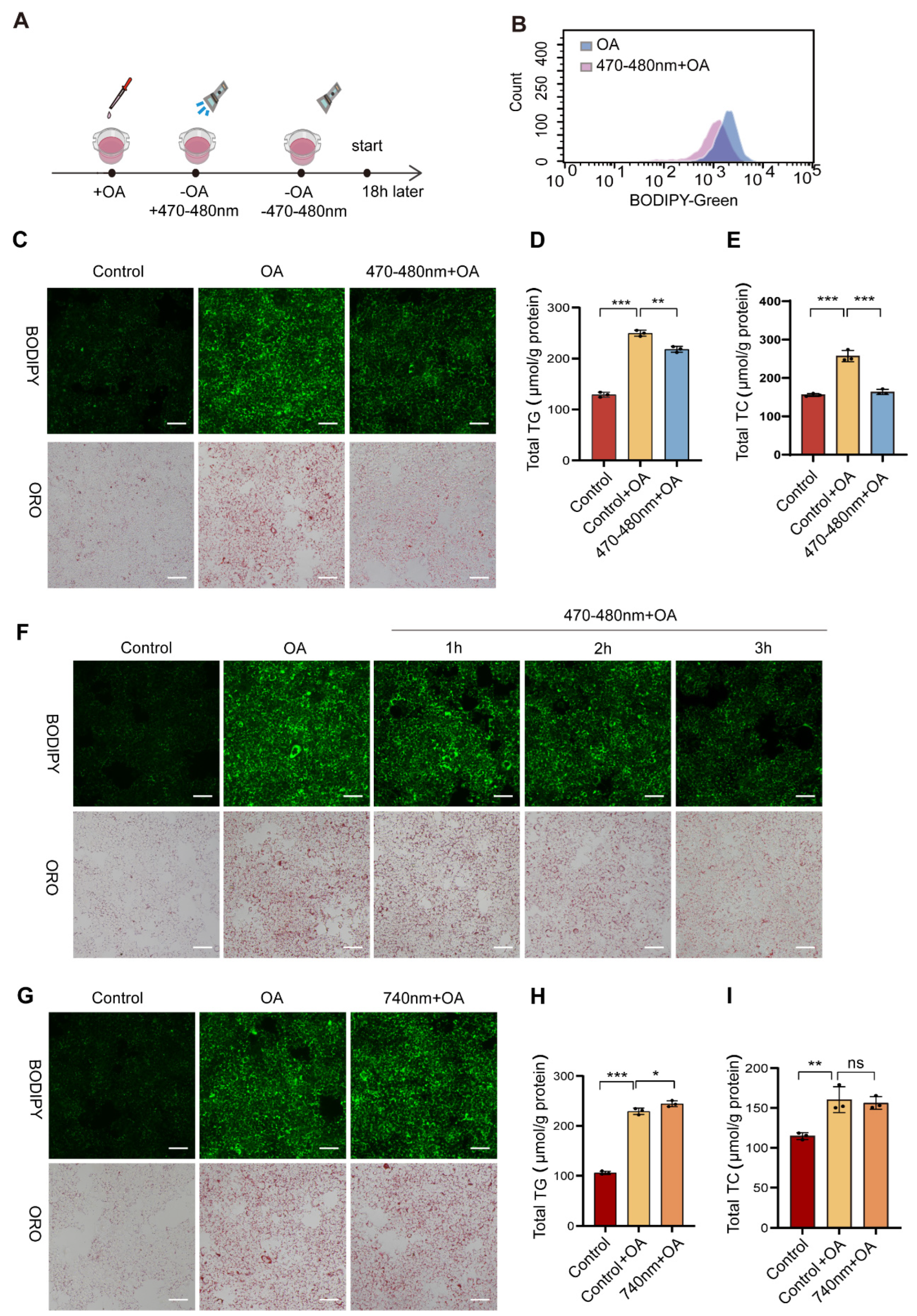

However, the mechanism by which blue light and Opn3 regulate lipolysis remains poorly understood. It is unclear whether they participate in lipid droplet degradation and how their action relates to classical lipid metabolic pathways. Using AML12 mouse hepatocytes, this study examined the impact of 470–480 nm blue light on the degradation of lipid droplets that had been accumulated through oleic acid (OA) treatment. Blue light exposure significantly reduced lipid droplet content and decreased triglyceride (TG) and total cholesterol (TC) levels in an Opn3-dependent manner. Opn3 KO cells confirmed that Opn3 is required for blue light-induced lipid droplet degradation. Furthermore, we identified critical roles for Pparα and p62 in this pathway: Pparα KO markedly inhibited blue light-mediated lipid droplet degradation, while p62 deletion blocked both Lc3b conversion and lipid droplet clearance. Given the significant impact of lipids on viral infection [

21,

22], we unexpectedly found that blue light exposure reduced replication of VSV, H1N1, and EMCV viruses, an effect abolished in Opn3 KO cells.

These results indicate that blue light promotes lipid droplet degradation through the Opn3- Pparα signaling axis, with the autophagy protein p62 playing an essential role. Additionally, Blue light combined with Opn3 reduces viral replication. This study advances our understanding of the relationship between light exposure and lipid droplet metabolism, offering new perspectives for treating related metabolic disorders and providing a foundation for antiviral research.

2. Methods

2.1. Antibodies and Reagents

Sodium oleate (S104196) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), and Oil Red O (O0625) was purchased from Sigma (Shanghai, China). BODIPY 493/503 (C2053S) and BSA (ST025) was purchased from Beyotime (Shanghai, China). Propidium Iodide (40710ES03) was purchased from Yeasen (Shanghai, China). Propidium iodide was purchased from Kunchuang Biotechnology (Xi’an, China).

The antibodies used in our experiments included: β-Actin (GB15001, Servicebio, WuHan, China), OPN3 (DF4877, Affinity, Cincinnati, OH, USA), PPARα (GB11163, Servicebio), LC3B (18725-1-AP, Proteintech, Chicago, IL, USA), P62 (18420-1-AP, Proteintech), H1N1 (11675-T62, Sino Biological, Beijing, China).

2.2. Cell Culture and Exposure Conditions

Mouse normal liver cells (AML12) and Human Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Cells (A549) were cultured in high-glucose DMEM medium (G4515, Servicebio) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (F101-01, Vazyme, Nanjing, China), 1% penicillin/streptomycin (PB180120, Pricella, Wuhan, China), and 10% insulin-transferrin-selenium medium supplement (ITSS-10201, OriCell, Guangzhou, China). The cells were cultured at 37 °C with 5% CO2 until 70–80% confluence was reached, then the experiment was initiated. Subsequently, the cells were exposed to 0.4 mM Oleic acid for 6 h before undergoing light exposure.

The blue LED light (470–480 nm) was purchased from Boxing Technology Co., Ltd. (Shenzhen, China). Cells were exposed to blue light with 0.2 mW/cm2 power density. The total energy dose after three hours of exposure is 2.16 J/cm2. The total energy received by cells per well in the 12-well plate is 7.56 J. The temperature is maintained at around 37 °C.

2.3. Western Blotting

Proteins were extracted from cells using LSB buffer containing a mixture of protease inhibitors (excluding EDTA) and phosphatase inhibitors. Perform BCA (ZJ102, Omni, Shanghai, China) quantification in accordance with the instructions of the kit. Equal amounts of proteins were separated by 10–12% SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis and transferred onto PVDF membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). The membrane was immersed in the blocking solution prepared with 5% milk for 2 h, washed with Tris Buffered Saline with Tween (TBST) three times for 5 min each time, and then incubated overnight at 4 °C. Primary antibodies: Opn3 (1:1000), p62 (1:2000), LC3B (1:3000), Pparα (1:1000), β-actin (1:5000), H1N1(1:2000). Subsequently, the membrane and the secondary antibody were incubated at room temperature for 1 h. Then wash three times with TBST, each time for 5 min. All bands were imaged using the ECL chemiluminescence system. Western blot original images can be found in

Supplementary Materials.

2.4. Oil Red O Staining

After treating the cells with OA and light exposure, wash them twice with PBS, then fix them with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min, and wash them twice again with PBS to remove the excess paraformaldehyde. Subsequently, each well was treated with 60% isopropyl alcohol for 5 min and then discarded. Add the filtered oil red O working solution to the cells and stain them in the dark for 30 min, then wash them twice with distilled water. Finally, images were captured using an inverted microscope.

2.5. Real-Time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from cells using VeZol Reagent (R441-02-AA, Vazyme). The purity and concentration of RNA were measured using a Nanodrop-2000. Subsequently, the RNA was reverse-transcribed into an equal amount of cDNA using the SweScript All-in-One RT SuperMix for qPCR (G3337, Servicebio). Quantitative real-time PCR (RT-qPCR) was performed on a StepOne Real-Time PCR System using the 2× Universal Blue SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix (G3328-15, Servicebio). All procedures were conducted according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The primers were synthesized by Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Gapdh was utilized as a normalization control. The primer sequences for the qPCR are provided in

Supplementary Table S1.

2.6. Transfection and Establishment of Stable Cell Lines

The construction of lentiviral CRISPR-Cas9 vectors targeting genes was performed according to a standard experimental protocol. The detailed steps are as follows: Guide RNA (gRNA) was designed and synthesized, annealed, and then ligated into the vector via the BsmBI restriction sites. The gRNA sequences targeting Opn3 and p62 genes were obtained using an online design tool (e.g., CRISPR Design-

http://chopchop.cbu.uib.no/, accessed on 26 November 2025) and are provided in

Supplementary Table S2. For transient transfection and initial viral collection, HEK293T cells were seeded in 6-well plates and transfected with the plasmids required for lentivirus packaging using Lipofectamine 3000 (L3000015, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. To establish stable cell lines, the medium was changed 6 h after transfection and 3 mL of medium was added for continued culture. After 24 h, 2 mL of medium was added and the cells were cultured for one day. Subsequently, the lentiviral supernatant collected from the transfected HEK293T cells was centrifuged. Target cells were then infected in the presence of 5 μg/mL polybrene (107689, Sigma) and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 1.5 h. Forty-eight hours post-transduction, the lentivirus-transduced Target cells were cultured in the presence of 2 μg/mL puromycin (ant-pr, Invivogen, Toulouse, France) for 2 weeks. Puromycin-resistant colonies were subsequently collected and subjected to further validation by Western blotting.

2.7. BODIPY 493/503 Staining

Discard the culture medium from the cells, wash once with PBS, then add diluted BODIPY solution (1 μg/mL) for 15 min incubation protected from light. After removing the staining solution, add fresh PBS and observe under a fluorescence microscope using a 20× objective lens.

2.8. Triglyceride Assay

The triglyceride levels were measured using a Tissue/Cell Triglyceride Assay Kit (E1013, Applygen, Beijing, China), and the experimental procedures were strictly performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Experimental cells were treated with a specific volume of lysis buffer, followed by centrifugation. An appropriate volume of supernatant was then mixed with the working solution in a 96-well plate. After incubation at 37 °C for 15 min, absorbance was measured at a wavelength of 550 nm. The results were quantified by using a standard curve and the protein BCA quantitative method for extrapolation.

2.9. Cholesterol Assay

Total cholesterol levels were determined using a Total Cholesterol Assay Kit (E1015, Applygen), and the experimental procedures were strictly performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Experimental cells were lysed with a defined volume of lysis buffer and centrifuged. A precise volume of supernatant was combined with the working solution in a 96-well plate. Following a 15 min reaction at 37 °C, absorbance was recorded at 550 nm. The results were quantified by using a standard curve and the protein BCA quantitative method for extrapolation.

2.10. Viral Infection Assay

Vesicular stomatitis virus labeled with enhanced green fluorescent protein (VSV-GFP), EMCV, human influenza virus A/Puerto Rico/8/34 (H1N1) (PR8) were stored from our laboratory. Cells were seeded in culture plates and allowed to reach 60–70% confluence prior to experimentation. Wild-type AML12 cells were infected with diluted viral suspensions at the following multiplicities of infection: GFP-VSV (1:500), EMCV (1:10,000), and H1N1 (1:10,000). Similarly, Opn3-knockout AML12 cells were infected with VSV (1:500), EMCV (1:10,000), and H1N1 (1:10,000). After 6 h of incubation in a cell culture incubator, the cells were exposed to 470–480 nm blue light for 3 h, followed by an additional 4 h of culture before subsequent analyses were performed.

2.11. PI Staining

After the designated treatments, cells were incubated with propidium iodide (PI) at a final concentration of 5 µg/mL in the appropriate binding buffer. After gentle mixing, the sample is incubated at room temperature for 30 min in the dark to prevent photobleaching, followed by image acquisition under a microscope.

2.12. Statistical Analyses

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 9.0. All data were expressed as mean ± SD. Data were tested for a normal (Gaussian) distribution using Shapiro–Wilk normality test. For comparisons involving multiple groups, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s or Dunnett’s multiple comparison test was used for multiple group comparisons. Comparisons between two groups were conducted using an unpaired t-test. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4. Discussion

This study combined light exposure with lipid droplet metabolism. The results show that 470–480 nm blue light effectively reduced OA-induced lipid droplets in cells. A comparison of different exposure times (1 h, 2 h, 3 h) revealed a time-dependent degradation rate, with a marked increase in degradation efficiency observed in the 3 h group. Notably, the 740 nm red light control caused no lipid droplet reduction, ruling out non-specific effects like heat or phototoxicity. Subsequent experiments using Opn3 KO cells showed strong resistance to the blue light effect, confirming that Opn3 is necessary for the light signal. To investigate the mechanism by which Opn3 mediates lipid droplet degradation, we analyzed the mRNA expression of key genes involved in lipid synthesis and breakdown pathways through transcriptomic analysis. Following blue light exposure (470–480 nm), the expression of lipid catabolism genes was significantly upregulated. Conversely, this effect was reversed in Opn3 KO groups under identical conditions. In contrast, the expression of lipid synthesis factors decreased after light exposure, but increased upon Opn3 KO. Among the changes, Pparα was particularly prominent. As a central transcription factor regulating lipid oxidative metabolism, it promotes fatty acid β-oxidation by activating the expression of key enzymes involved in fatty acid breakdown [

23]. The study identified Pparα as a key downstream effector in blue light-induced lipid droplet degradation, whose absence blocked the photolytic effect on lipids. As evidenced by the results in

Figure 2, Pparα knockdown produced a phenotype similar to Opn3 KO, effectively resisting the blue light effect. Specifically, Pparα knockdown prevented the degradation of lipid droplets mediated by blue light through Opn3. This indicates that both molecules operate within the same pathway, with Pparα functioning as a component in the downstream of Opn3. Beyond conventional lipolysis, lipid droplets can also be degraded via autophagy. We therefore investigated whether this pathway contributes to the light-induced effect. OA treatment alone increased the LC3B-II/I ratio and P62 levels, suggesting autophagic initiation with subsequent flux blockade. Blue light irradiation following OA treatment elevated the LC3B-II/I ratio and significantly reduced p62, indicating that blue light reduces lipid droplets through autophagy. In Opn3 KO cells, blue light irradiation increased the LC3B-II/I ratio and again elevated p62 levels. The downstream of autophagy was blocked, while lipid droplet autophagy was inhibited. The Western blot analysis was consistent with the other experimental results, and further demonstrated that blue light and Opn3 facilitate lipid degradation through the pathway of lipophagy.

VSV and EMCV, as well as the H1N1 virus, are well-known model viruses that have made significant contributions in academic research and the medical field. This study reveals a central role for Opn3 in light-induced antiviral defense. Blue light, acting through an Opn3-dependent mechanism, significantly suppressed the replication of diverse viruses including VSV, EMCV, and H1N1, while also reducing virus-induced cell death and inflammation. Conversely, Opn3 deficiency enhanced viral replication. This study found that blue light significantly inhibits the replication of multiple viruses through Opn3. It is noteworthy that a substantial body of research has demonstrated a correlation between lipids and viral replication, where the presence of lipids can accelerate infection by certain viruses and promote inflammatory responses. Lipid droplets can serve as platforms facilitating viral assembly and replication, including for viruses such as Zika virus [

22], Junín virus [

24], and Rabies virus [

25]. Cholesterol has also been shown to promote the replication of Influenza A virus (IAV) and accelerate infection [

26]. Therefore, we propose a possible mechanism for the observed blue light-mediated inhibition of viral replication via Opn3: blue light-driven lipid droplet breakdown and fatty acid oxidation may rapidly deplete the lipid resources essential for viral assembly, thereby restricting viral replication.

Pparα is a key transcriptional regulator of fatty acid metabolism. It can be activated not only by endogenous ligands, including fatty acids and eicosanoids, but also by synthetic compounds like fibrates and thiazolidinediones, as well as indirectly through energy stress [

27]. We propose three potential mechanisms for Opn3-mediated Pparα regulation. Firstly, as a nuclear receptor, Pparα operates within the cell nucleus. It acts as a transcription factor to promote the expression of fatty acid enzymes. Therefore, Pparα requires the regulation of nuclear export proteins and import proteins to achieve stable expression in the nucleus. Li’s research team has found that hyodeoxycholic acid can block the interaction between RAN and the nuclear export receptor CRM1, leading to increased accumulation of Pparα in the nucleus [

28]. Therefore, it is possible that Opn3 may promote Pparα activation—and thereby enhance lipid droplet breakdown under blue light—by directly or indirectly influencing CRM1 or other nuclear transport receptors. Secondly, Pparα must form a heterodimer with the retinoid X receptor (RXR) to regulate gene expression. It is possible that light activation of Opn3 could strengthen this dimerization process. Finally, transcriptome data from study shows significant differences in AMPK pathway activity between Opn3 KO cells and normal cells after blue light exposure. AMPK is a central regulator of cellular energy metabolism and lipid homeostasis, functioning by sensing changes in the AMP/ATP ratio. Therefore, another reasonable explanation is that Opn3 influences lipid metabolism through certain steps in the AMPK pathway. Supporting this view, Liu et al. have demonstrated that the AMPK/Pparα signaling pathway can regulate lipid metabolism in hepatocytes and ameliorate MAFLD [

29]. Meanwhile, based on the re-analysis of transcriptomic data from the Control + OA and 470–480 nm + OA groups, we found that the expression of

Fads1 and

Fads2, key genes catalyzing the biosynthesis of polyunsaturated fatty acids, was significantly upregulated upon blue light irradiation, suggesting that blue light may promote the synthesis of unsaturated fatty acids in cells. As polyunsaturated fatty acid metabolism is regulated by Pparα, this finding is highly consistent with the role of the “blue light-Opn3-Pparα” signaling axis identified in this study. At the same time, the expression of several key genes involved in saturated fatty acid synthesis, such as

Fas and

Acc1, was downregulated after blue light exposure, indicating inhibition of saturated fatty acid synthesis. This “up-down” pattern of gene expression collectively suggests that blue light may promote the formation of polyunsaturated fatty acids, thereby reducing oleic acid-induced lipid droplet accumulation. However, the specific pathways involved in this regulatory mechanism remain unclear. In the future, further research on the mechanism is needed to clarify the role of unsaturated fatty acids in lipid reduction under blue light.

As another major pathway for eliminating excess lipids, lipophagy also plays a vital role in the body [

30,

31]. One study found that blue light exposure increased the levels of LC3 and Beclin-1 in colon cancer cells. This light-triggered autophagy, which is mediated by the Opn3 photoreceptor pathway, resulted in the suppression of cancer cell growth [

32]. Our study also indicates a correlation between Opn3-mediated lipid droplet breakdown and lipophagy under blue light. We observed an increase in LC3B protein levels and a reduction in p62degradation following light exposure. Since the absence of p62 impaired lipid droplet clearance after blue light, we propose that Opn3 may also reduce lipid accumulation through the lipophagy pathway.