Abstract

Necroptosis is an inflammatory form of lytic programmed cell death that is thought to have evolved to defend against pathogens. Genetic deletion of the terminal effector protein—MLKL—shows no overt phenotype in the C57BL/6 mouse strain under conventional laboratory housing conditions. Small molecules that inhibit necroptosis by targeting the kinase activity of RIPK1, one of the main upstream conduits to MLKL activation, have shown promise in several murine models of non-infectious disease and in phase II human clinical trials. This has triggered in excess of one billion dollars (USD) in investment into the emerging class of necroptosis blocking drugs, and the potential utility of targeting the terminal effector is being closely scrutinised. Here we review murine models of disease, both genetic deletion and mutation, that investigate the role of MLKL. We summarize a series of examples from several broad disease categories including ischemia reperfusion injury, sterile inflammation, pathogen infection and hematological stress. Elucidating MLKL’s contribution to mouse models of disease is an important first step to identify human indications that stand to benefit most from MLKL-targeted drug therapies.

1. Introduction

Necroptosis and Disease

Mixed Lineage Kinase Domain-Like (MLKL) was shown to be the essential effector of a pro-inflammatory, lytic form of programmed cell death called necroptosis in 2012 [1,2]. Like other forms of lytic cell death (e.g., pyroptosis), necroptosis is characterised by the release of Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns (DAMPs) and IL-33, IL-1α and IL-1β production, as recently reviewed by [3]. Unlike apoptosis, necroptosis and the canonical signalling pathway RIPK1-RIPK3-MLKL are not essential to the development and homeostasis of multicellular organisms [4]. The two most downstream effectors of necroptosis, MLKL and its obligate activating kinase RIPK3, can be deleted at the genetic level in laboratory mice without any overt developmental consequences in the absence of challenge [5,6,7]. Thus, it is widely held that MLKL and necroptosis have evolved primarily to defend against pathogenic insult to cells and tissues. This important role of necroptosis in pathogen defence is written in the DNA of many bacteria and viruses alike, which together encode several genes that disarm different facets of the necroptotic signalling pathway [8,9,10]. In evolution, genetic deletion of MLKL and/or RIPK3 in the ancestors of modern day carnivora, metatheria (marsupials) and aves (birds) show that complex vertebrates can survive without necroptosis when faced with infectious challenges of the ‘real world’ [11]. This adds to the precedent for the well-honed flexibility, redundancy and co-operation of different programmed cell death pathways in the defence against pathogens [12] and offers some biological guide that inhibiting MLKL pharmacologically in humans would not compromise pathogenic defence. Interestingly, recent studies suggest that the suppression of necroptosis may even reduce the resulting inflammatory response that is often more dangerous than the infection itself [13]. Mlkl gene knockout (abbreviated to both Mlkl−/− and Mlkl KO) mice are distinguishable from wild-type mice in numerous models of disease, a broad sampling of which are presented (Table 1) and illustrated (Figure 1) here.

Table 1.

Understanding the role of necroptosis in the aetiology of disease using Mlkl−/− and mutant mice.

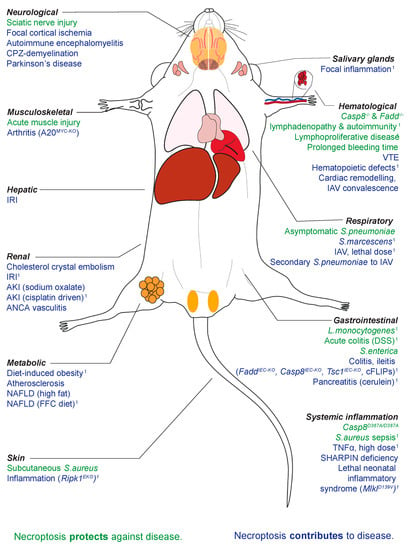

Figure 1.

The role of necroptosis in infective and non-infective challenges spanning a wide array of physiological systems. 1 Littermate controls utilised.

The therapeutic potential for necroptosis-targeted drugs lies largely in non-infectious indications. The first human clinical trials of RIPK1-targetted small molecule compounds were conducted in cohorts of rheumatoid arthritis, ulcerative colitis and psoriasis patients [14]. While these showed some promise in phase II, these were returned to the research phase in late 2019 by their licensee GlaxoSmithKline [15]. At the time of writing, there are only three active clinical trials in progress: a phase I trial assessing the safety of a new RIPK1 inhibitor (GFH312), a phase II study utilising RIPK1-binding compound, SAR443122, in cutaneous lupus erythematosus patients and a phase I/II study utilising RIPK1 inhibitor GSK2982772 in psoriasis [16]. There are currently no ‘first in human’ trials of RIPK3- or MLKL-binding compounds listed on http://clinicaltrials.gov (accessed on 28 May 2021).

2. Mlkl Knock-Out (KO) and Constitutively Active (CA) Mice at Steady State

Following the discovery of its essential role in necroptosis [1,2], two Mlkl knockout mouse strains were independently generated by traditional homologous recombination [5] and TALEN technology [7]. More recently, CRISPR-Cas9 engineered Mlkl−/− [17,33,73], constitutively active point mutant MlklD139V [40], affinity tagged Mlkl [67], conditional Mlkl−/− strains [29,67] and antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) in vivo Mlkl knockdown [60] mouse models have also been used in the study of necroptosis. Mlkl−/− mice are born at expected Mendelian ratios and are overtly indistinguishable from wild-type littermates at birth and through to early adulthood [5,7]. Full body histological examination of 2 day old Mlkl−/− pups did not reveal any obvious morphological differences, including lesions or evidence of inflammation, relative to wild-type C57BL/6 mice of the same age [40]. Furthermore, no histological differences have been reported for the major organs of young adult Mlkl−/− mice [5,7]. Hematopoietic stem cell populations in the bone marrow [5] and CD4/CD8 T cell, B cell, macrophage and neutrophil mature cell populations in secondary lymphoid organs display no observable differences in adult mice [7]. At steady state, serum cytokines and chemokines are indistinguishable from age-matched wild-type littermates [65]. The genetic absence of Mlkl and thus necroptosis is generally considered to be innocuous at steady state in the C57BL/6 strain of laboratory mice at a typical experimental age (up to 16 weeks) when housed under conventional clean, pathogen free conditions.

3. Mlkl−/− Mice in Ischemia and Reperfusion Injury (IRI)

While grouped here for simplicity, MLKL and cell death in general has the potential to influence many facets of the physiological response to blood vessel occlusion/recanalisation and resultant end-organ damage. These facets include the aetiology of the infarction itself, the cellular damage incurred due to the deprivation of oxygen and ATP, the generation of reactive oxygen species that occurs following tissue reperfusion and the inflammation that ensues and convalescence after injury [77]. As summarized in Table 1 (see ‘ischemia and reperfusion injury’), Mlkl−/− mice appear partially protected from the initial embolic insult [18,21]. For example, Mlkl−/− mice were reported to exhibit reduced infarct size and have better locomotive recovery day 7 post stroke [18]. This protective effect may in part be due to the role of MLKL and RIPK3 in regulating platelet function and homeostasis [72,78]. Mlkl knockout is also protective in models of hepatic and renal IRI [20,79]. Neutrophil activation and inflammation are significant contributors to hepatic IR injury [80]. Despite equivalent levels at steady state, the Mlkl−/− mice liver parenchyma shows significantly lower numbers of neutrophils 24 h post infarct [17]. This reinforces that the absence of MLKL can play a protective role at the initial ischemic stage and/or at later reperfusion stages, depending on the context.

4. Sterile Inflammation

The contribution of MLKL to mouse models of inflammation, which are not borne of pathogenic insult, termed sterile inflammation, is complex and varies according to the initiator, severity, and location within the body. This point is nicely illustrated by systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS). Unlike catalytically inactive RIPK1 or RIPK3 deficiency in mice, Mlkl−/− mice are not protected against SIRS driven by low dose TNFα [20] or A20 deficiency [20]. When wild-type mice are pre-treated with compound 2, a potent inhibitor of necroptosis that binds to RIPK1, RIPK3 and MLKL, hypothermia is delayed [81]. Together these findings suggest protection against SIRS is necroptosis-independent and occurs upstream of MLKL. Mlkl−/− mice, however, are significantly protected against SIRS caused by high dose TNF [19,20,81]. Ripk3−/− mice are similarly protected against high dose TNFα. Remarkably, in contrast to single knockouts, Ripk3−/−Mlkl−/− double knockouts resemble wild-type mice and develop severe hypothermia in response to high dose TNFα [19]. This paradoxical reaction is yet to be fully explained by the field. Furthermore, the ablation of MLKL is seen to worsen inflammation induced by non-cleavable caspase-8 (seen in Casp8D387A/D387A mice) [39] and A20 deficiency [20]. This indicates that necroptosis may serve to limit systemic inflammation in certain scenarios in vivo, a phenomenon also supported by examples of pathogen induced inflammation (see ‘Infection’, Table 1).

One major area of contention is the role of MLKL in mouse models of inflammatory bowel disease [31,32,34,35] and inflammatory arthritis [28,30]; however, key differences in experimental approach may explain these disparities (See Table 1, ‘Mlkl−/− mice and wild-type control’ details). Similarly, there have been conflicting reports investigating the role of MLKL-driven necroptosis in liver injury [24,25]. Whilst whole body knock-out of Mlkl confers protection, independent of immune cells [24], hepatocyte specific ablation of Mlkl reveals that necroptosis in parenchymal liver cells is, in fact, dispensable in immune-mediated hepatitis [25]. It would therefore be of interest to know the cell type in which Mlkl−/− confers protection now that hepatocytes [25] and immune cells [24] have been ruled out. MLKL-deficiency mediates protective effects in models of more localised sterile inflammatory disease: dermatitis [36], cerulein-induced pancreatitis [7], ANCA-driven vasculitis [27], necrotising crescent glomerulonephritis [27] and oxalate nephropathy [22]. Consistent with these findings, mice expressing a constitutively active form of MLKL develop a lethal perinatal syndrome, characterised by acute multifocal inflammation of the head, neck and mediastinum [40].

5. Infection: Bacterial

MLKL-dependent necroptosis is thought to have evolved as a pathogen-clearing form of cell death. In support of this theory, 7 of the 10 murine models of bacterial infection examined here led to poorer outcomes in mice lacking MLKL. In response to both acute and chronic infection with Staphylococcus aureus and methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA), Mlkl−/− mice suffer a greater bacterial burden and subsequent mortality [41,42]. This was observed across intravenous, subcutaneous, intraperitoneal, and retro-orbital methods of inoculation [41,42]. Interestingly, despite necroptosis being an inflammatory form of cell death, Mlkl−/− mice were found to have greater numbers of circulating neutrophils and raised inflammatory markers (caspase-1 and IL-1β) [41,42]. This is exemplified in models of skin infection where Mlkl−/− mice suffer severe skin lesions characterised by excessive inflammation [41]. This suggests that necroptosis is important for limiting bacterial dissemination and modulating the inflammatory response [41]. As an example, MLKL-dependent neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) formation was reported to restrict bacterial replication [42] and contribute to the pathogenesis of inflammatory disease, such as rheumatoid arthritis [82]. In addition to the important infection-busting role of MLKL in neutrophils, non-hematopoietic MLKL is also important for protection against gut-borne infections. MLKL-mediated enterocyte turnover and inflammasome activation were shown to limit early mucosal colonisation by Salmonella [49]. MLKL was even shown to bind and inhibit the intracellular replication of Listeria, presaging exploration into a more direct, cell-death independent mode of MLKL-mediated pathogen defence [48].

Through co-evolution, bacteria have developed ways to evade, and in some cases, weaponise MLKL and necroptosis for their own ends. Certain bacteria, such as Serratia marcescens and Streptococcus pneumoniae, produce pore-forming toxins (PFTs) to induce necroptosis in macrophages and lung epithelial cells [47,53]. Mlkl−/− mice are consequently resistant to these infections and survive longer than wild-type controls [47,53]. Although PFT-induced necroptosis was reported to exacerbate pulmonary injury in acute infection, it does promote adaptive immunity against colonising pneumococci [46]. Mlkl−/− mice demonstrate a diminished immune response, producing less anti-spn IgG antibody and thus succumb more readily to secondary lethal S. pneumoniae infection [46]. This suggests necroptosis is instrumental in the natural development of immunity to opportunistic PFT-producing bacteria [46]. Interestingly, Mlkl−/− has been described to be both protective against [44] and dispensable in [7] the pathogenesis of CLP-induced polymicrobial shock. Results derived from the CLP model of shock can be difficult to replicate, given the inter-facility and even intra-facility heterogeneity of the caecal microbiota in mice [7]. Cell death pathways occur simultaneously during the progression of sepsis, and there is no conclusive evidence of which pathway plays the most deleterious role [7]. Similarly, MLKL appears dispensable for granulomatous inflammation and restriction of Mycobacterium tuberculosis colonisation [43].

6. Infection: Viral

MLKL can either protect against viral infection or contribute to viral propagation and/morbidity, depending on the type of virus. In initial studies, Mlkl−/− mice were indistinguishable from wild-type littermates in response to influenza A (IAV) [13,50,51] and West Nile virus infection [54]. Recent findings, however, suggest that Mlkl knockout confers protection against lung damage from lethal doses of influenza A [13]. Despite equivalent pulmonary viral titres to wild-type littermates, Mlkl−/− mice had a considerable attenuation in the degree of neutrophil infiltration (~50%) and subsequent NET formation and thus were protected from the exaggerated inflammatory response that occurs later in the infection [13]. In line with this finding, Mlkl−/− mice are protected against bacterial infection secondary to IAV [53]. A recent study also finds that MLKL-deficiency mediates protection against cardiac remodelling during convalescence following IAV infection by upregulating antioxidant activity and mitochondrial function [52], indicating the potential utility of MLKL-targeted therapies for both the acute and long term effects of viral infection.

7. Metabolic Disease

MLKL deficiency has shown diverse effects in at least four separate studies of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). After 18 hours of a choline-deficient methionine-supplemented diet [55] or 8 weeks of a Western diet [17], Mlkl−/− mice are indistinguishable from wild-type controls. Following 12 weeks of a high fat diet (HFD) [56], however, Mlkl−/− mice appear resistant to steatohepatitis given that MLKL-deficiency promotes reduced de novo fat synthesis and chemokine ligand expression [56]. A similar effect is seen following 12 weeks of a high fat, fructose, and cholesterol diet, where Mlkl−/− mice are markedly protected against liver injury, hepatic inflammation and apoptosis attributed to inhibition of hepatic autophagy [57]. In line with these findings, mice treated with RIPA-56 (an inhibitor of RIPK1) downregulate MLKL expression and were found to be protected against HFD-induced steatosis [83]. These findings offer a tantalising clue that necroptosis may contribute to this disease, depending on the trigger. In contrast to NAFLD, MLKL does not appear to play a statistically significant role in acute or chronic alcoholic liver disease [58].

MLKL deficiency provides variable protection against the metabolic syndrome, depending on the challenge. MLKL deficiency appears to protect against dyslipidaemia with reduced serum triglyceride and cholesterol levels following a high fat diet [56] and Western diet [60], respectively. Whilst Mlkl−/− mice appear to have significantly improved fasting blood glucose levels given improved insulin sensitivity following 16 weeks of a high fat diet [59], there is conflicting evidence on the effect at steady state [56,59]. There is also conflicting evidence on the role of MLKL deficiency in adipose tissue deposition and weight gain [56,59]. Whilst comparable at baseline, after 16 weeks of HFD, Mlkl−/− mice gained significantly less body weight, notably visceral adipose tissue, than their wild-type littermates [59]. Blocking upstream RIPK1, has a similar effect [84]. Yet, in another study, after 12 weeks of HFD there were no significant differences found in body weight between Mlkl−/− and wild-type [56]. Finally, MLKL has been shown to play a role in atherogenesis; MLKL facilitates lipid handling in macrophages, and upon inhibition, the size of the necrotic core in the plaque is reduced [60]. Of the eight broad disease classes covered in this review, the role of MLKL in metabolic disease is arguably the most disputed, owing to the long-term nature of the experiments and the propensity for confounding variables, including genetic background and inter-facility variation in microbiome composition. The field may benefit from a more standardised approach to metabolic challenge and the prioritization of data generated using congenic littermate controls.

8. Neuromuscular

Evidence is rapidly accumulating for the role of MLKL in mouse models of neurological disease. Mlkl−/− mice were reported to be protected in one model of chemically-induced Parkinson’s disease, with a significantly attenuated neurotoxic inflammatory response contributing to higher dopamine levels [69]. Strikingly, recent evidence suggests that MLKL may be important for tissue regeneration following acute neuromuscular injury [67,70]. In a model of cardiotoxin-induced muscle injury, muscle regeneration is driven by necroptotic muscle fibres releasing factors into the muscle stem cell microenvironment [70]. Mlkl−/− mice accumulate massive death-resistant myofibrils at the injury site [70]. Furthermore, in a model of sciatic nerve injury, MLKL was reported as highly expressed by myelin sheath cells to promote breakdown and subsequent nerve regeneration [67]. Overexpression of MLKL in this model is found to accelerate nerve regeneration [67] speaking to the potential of MLKL enhancing rather than blocking drugs in this area. However, contraindicating the use of MLKL activating drugs to mitigate neurological disease is the observation that MLKL accelerates demyelination in a necroptosis-independent fashion and thereby worsens multiple sclerosis pathology [68]. Finally, the role of necroptosis in murine amyotrophic lateral sclerosis remains contentious in the field. Wang et al. (2020) reported that MLKL-dependent necroptosis appears dispensable in the onset, progression, and survival of SOD1G93A mice. Yet, there have been robust studies suggesting RIPK1-RIPK3-MLKL drives axonal pathology in both SOD1G93A and Optn−/− mice [85,86]. While opinions in the field remain split on the relative contribution of MLKL in hematological (which express high levels of MLKL) vs. non-hematological (i.e., neurons express low levels of MLKL at baseline) cells in many of these models, disorders of the neuromuscular system have clearly come to the fore in commercial necroptosis drug development efforts.

9. Hematological

Mlkl−/− mice are hematologically indistinguishable from wild-type at steady state [5,79,87]. This trend continues as the mice age to 100 days [65]. Properly regulated necroptosis, however, is indispensable for hematological homeostasis. MlklD139V/D139V mice (which encode a constitutively active form of MLKL that functions independently of upstream activation from RIPK3) have severe deficits in platelet, lymphocyte, and hematopoietic stem cell counts [40]. Mice expressing even one copy of this MlklD139V allele are unable to effectively reconstitute the hematopoietic system following sub-lethal irradiation or in competitive reconstitution studies [40]. Like Ripk3−/− mice, Mlkl−/− mice display a prolonged bleeding time and thus unstable thrombus formation [72,78]. MLKL, however, appears to play an additional, RIPK3-independent, role in platelet formation/clearance. In a model of lymphoproliferative disorder, Casp8−/−Mlkl−/− double knockout mice develop a severe thrombocytopaenia that worsens with age (measured at 50 and 100 days) [65]. This phenotype is not observed in age-matched Casp8−/−Ripk3−/− mice [65]. Finally, MLKL has also been shown to function in neutrophil NET-formation at the cellular level [42], and Mlkl−/− mice are seen to be protected from diseases that implicate NET-formation, for example ANCA associated vasculitis [27] and deep vein thrombosis [71].

10. Cancer and Cancer Treatment

Cisplatin is a common chemotherapy that treats solid cancers, although its utility is limited by its nephrotoxic effects [23]. Strikingly, Mlkl−/− mice are reported to be largely resistant to cisplatin-induced tubular necrosis compared to wild-type controls [23]. However, mechanistically it is still not understood how systemic delivery of a DNA-damaging agent such as cisplatin could induce renal necroptosis and whether it is particular to kidney tissue. Hematopoietic stem cells derived from Mlkl−/− mice play a key role in studies showing that apoptosis-resistant acute myeloid leukemia (AML) could be forced to die via necroptosis [61]. By adding the caspase inhibitor IDN-6556/emricasan, AML cells are sensitised to undergo necroptosis in response to the known clinical inducer of apoptosis SMAC mimetic, birinapant [61]. IDN-6556/emricasan is well-tolerated in humans [88] and is an excellent example of a therapeutic approach designed to enhance rather than block MLKL activity in vivo. Finally, the role of MLKL in intestinal tumorigenesis remains unclear, with studies reporting that MLKL is dispensable in both sporadic intestinal or colitis-associated cancer [35], and yet MLKL has been reported to have a protective effect in Apcmin/+ mice [62] by suppressing IL-6/JAK2/STAT3 signals [63].

11. Reproductive System

There are two studies that assess the role of MLKL in age-induced male infertility. Mlkl−/− mice aged to 15 months demonstrate significantly reduced body, testicular and seminal vesicle weight alongside increased testosterone levels and fertility [73] when compared to age matched wild-type mice. A recent follow up study suggests that CSNK1G2, a member of the casein kinase family, is co-expressed in the testes and inhibits necroptosis-mediated aging [89]. This phenomenon is also seen in human testes [89]. Another study that uses congenic littermate controls, however, finds that male mice aged to 18 months are indistinguishable from wild-type littermates with regards to total body, testicular and seminal vesicle weight [74].

12. Important Experimental Determinants in MLKL-Related Mouse Research

There are several high profile examples of genetic drift [90], passenger mutations [90], facility-dependent variation in the microbiomes of mice [91], sex [92] and age [93] acting as important modifiers of the innate immune response. One notable example is the significant differences between commonly used wild-type control C567BL/6J and C57BL/6NJ (also known as C57BL/6N) sub-strains (separated by 60+ years of independent breeding) in morbidity and survival following LPS- and TNFα-induced lethal shock [20,90]. Of similar interest, male mice are reported to be more susceptible than females to invasive pneumonia and sepsis [94]. Generously powered cohorts of sex-segregated, co-housed, congenic littermates (mice derived from a heterozygous cross) are the gold standard for controlling these confounding variables when comparing wild-type and Mlkl KO/mutant mice (or any other mutant) [91]. All scientists that work with mice will attest that while this approach is certainly time, resource, and mouse-number intensive, it should nonetheless be prioritised by experimenters and peer reviewers alike wherever possible. We congratulate the efforts of scientists who proceed one step further by restoring the wild-type phenotype through ectopic expression of MLKL [67]. When the use of littermate controls is not feasible, clear, and detailed descriptions of mouse age, sex and provenance provided in publications act as important caveats for discerning reviewers and readers to consider. In Table 1, we summarize the outcomes of these comparisons in 80+ contexts and have included a column that provides details of caveats where available.

13. Concluding Remarks

Genetic and experimental models of disease provide a strong rationale that MLKL and necroptosis are important mediators and modifiers of infectious and non-infectious disease. The study of MLKL in mouse models has indicated a bidirectional role of necroptosis in disease. Inhibiting the function of MLKL may confer protection in diseases characterised by hematopoietic dysfunction and uncontrolled inflammation borne of (and/or perpetuating) the failure of epithelial barriers throughout the body. Enhancing MLKL-induced cell death may prove beneficial in the treatment of malignancies and nerve injury. The therapeutic potential of MLKL as a druggable target in infectious disease is highly nuanced and will require careful tailoring to the pathogen and infection site/stage in question. Importantly, any extrapolation of these observations in Mlkl knockout and mutant mice to human disease must be tempered by our knowledge of key differences in both the structure and regulation of mouse and human MLKL [95,96,97]. This point is particularly poignant considering withdrawals of certain RIPK1 inhibitor drugs from phase I (pancreatic cancer) and II (chronic inflammatory diseases) clinical trials due to lack of efficacy [98,99]. Rapid advances in the ‘humanisation’ of mouse models of disease and the use of large human clinico-genetic databases will further enrich the extensive body of murine data supporting the role of MLKL in human disease.

Author Contributions

E.C.T.C., S.E.G. and J.M.H. contributed to the conceptualization, writing and funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

J.M.H. is the recipient of an Australian NHMRC Career Development Fellowship 1142669. S.E.G. is the recipient of The Wendy Dowsett Scholarship. ETC is the recipient of the Attracting and Retaining Clinician-Scientists (ARCS) scholarship.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank James Murphy, Cheree Fitzgibbon and André Samson for their careful reading of this manuscript and helpful suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

J.M.H. contributes to a protect developing necroptosis inhibitors in collaboration with Anaxis Pty Ltd.

References

- Sun, L.; Wang, H.; Wang, Z.; He, S.; Chen, S.; Liao, D.; Wang, L.; Yan, J.; Liu, W.; Lei, X.; et al. Mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein mediates necrosis signaling downstream of RIP3 kinase. Cell 2012, 148, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Jitkaew, S.; Cai, Z.; Choksi, S.; Li, Q.; Luo, J.; Liu, Z.-G. Mixed lineage kinase domain-like is a key receptor interacting protein 3 downstream component of TNF-induced necrosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 5322–5327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weir, A.; Hughes, S.; Rashidi, M.; Hildebrand, J.M.; E Vince, J. Necroptotic movers and shakers: Cell types, inflammatory drivers and diseases. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2021, 68, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samson, A.L.; Garnish, S.E.; Hildebrand, J.M.; Murphy, J.M. Location, location, location: A compartmentalized view of TNF-induced necroptotic signaling. Sci. Signal. 2021, 14, eabc6178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, J.M.; Czabotar, P.E.; Hildebrand, J.M.; Lucet, I.S.; Zhang, J.-G.; Alvarez-Diaz, S.; Lewis, R.; Lalaoui, N.; Metcalf, D.; Webb, A.I.; et al. The pseudokinase MLKL mediates necroptosis via a molecular switch mechanism. Immunity 2013, 39, 443–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, K.; Sun, X.; Dixit, V.M. Kinase RIP3 is dispensable for normal NF-kappa Bs, signaling by the B-cell and T-cell receptors, tumor necrosis factor receptor 1, and Toll-like receptors 2 and 4. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004, 24, 1464–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Huang, Z.; Ren, J.; Zhang, Z.; He, P.; Li, Y.; Ma, J.; Chen, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, X.; et al. Mlkl knockout mice demonstrate the indispensable role of Mlkl in necroptosis. Cell Res. 2013, 23, 994–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearson, J.S.; Murphy, J.M. Down the rabbit hole: Is necroptosis truly an innate response to infection? Cell. Microbiol. 2017, 19, e12750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrie, E.J.; Sandow, J.J.; Lehmann, W.I.; Liang, L.-Y.; Coursier, D.; Young, S.N.; Kersten, W.J.; Fitzgibbon, C.; Samson, A.L.; Jacobsen, A.V.; et al. Viral MLKL Homologs Subvert Necroptotic Cell Death by Sequestering Cellular RIPK3. Cell Rep. 2019, 28, 3309–3319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silke, J.; Hartland, E.L. Masters, marionettes and modulators: Intersection of pathogen virulence factors and mammalian death receptor signaling. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2013, 25, 436–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dondelinger, Y.; Hulpiau, P.; Saeys, Y.; Bertrand, M.J.; Vandenabeele, P. An evolutionary perspective on the necroptotic pathway. Trends Cell Biol. 2016, 26, 721–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doerflinger, M.; Deng, Y.; Whitney, P.; Salvamoser, R.; Engel, S.; Kueh, A.J.; Tai, L.; Bachem, A.; Gressier, E.; Geoghegan, N.D.; et al. Flexible Usage and Interconnectivity of Diverse Cell Death Pathways Protect against Intracellular Infection. Immunity 2020, 53, 533–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Yin, C.; Boyd, D.F.; Quarato, G.; Ingram, J.P.; Shubina, M.; Ragan, K.B.; Ishizuka, T.; Crawford, J.C.; Tummers, B.; et al. Influenza Virus Z-RNAs Induce ZBP1-Mediated Necroptosis. Cell 2020, 180, 1115–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheridan, C. Death by inflammation: Drug makers chase the master controller. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 111–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GSK. Q3 2019 Results; GlaxoSmithKline: Brentford, UK, 2019; p. 28. [Google Scholar]

- Weisel, K.; Berger, S.; Papp, K.; Maari, C.; Krueger, J.G.; Scott, N.; Tompson, D.; Wang, S.; Simeoni, M.; Bertin, J.; et al. Response to Inhibition of Receptor-Interacting Protein Kinase 1 (RIPK1) in Active Plaque Psoriasis: A Randomized Placebo-Controlled Study. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 108, 808–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, H.-M.; Chao, X.; Kaseff, J.; Deng, F.; Wang, S.; Shi, Y.-H.; Li, T.; Ding, W.-X.; Jaeschke, H. Receptor-Interacting Serine/Threonine-Protein Kinase 3 (RIPK3)-Mixed Lineage Kinase Domain-Like Protein (MLKL)-Mediated Necroptosis Contributes to Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury of Steatotic Livers. Am. J. Pathol. 2019, 189, 1363–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Kim, T.; Steiger, S.; Mulay, S.R.; Klinkhammer, B.M.; Baeuerle, T.; Melica, M.E.; Romagnani, P.; Möckel, D.; Baues, M.; et al. Crystal Clots as Therapeutic Target in Cholesterol Crystal Embolism. Circ. Res. 2020, 126, e37–e52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moerke, C.; Bleibaum, F.; Kunzendorf, U.; Krautwald, S. Combined Knockout of RIPK3 and MLKL Reveals Unexpected Outcome in Tissue Injury and Inflammation. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2019, 7, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newton, K.; Dugger, D.L.; Maltzman, A.; Greve, J.M.; Hedehus, M.; Martin-McNulty, B.; Carano, R.A.D.; Cao, T.C.; Van Bruggen, N.; Bernstein, L.; et al. RIPK3 deficiency or catalytically inactive RIPK1 provides greater benefit than MLKL deficiency in mouse models of inflammation and tissue injury. Cell Death Differ. 2016, 23, 1565–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Fan, H.; Qi, C.; Zhang, K.; Liu, X.; Fei, L.; Chen, S.; Wang, M.; et al. RIPK3/MLKL-Mediated Neuronal Necroptosis Modulates the M1/M2 Polarization of Microglia/Macrophages in the Ischemic Cortex. Cereb Cortex 2018, 28, 2622–2635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulay, S.R.; Desai, J.; Kumar, S.V.; Eberhard, J.N.; Thomasova, D.; Romoli, S.; Grigorescu, M.; Kulkarni, O.P.; Popper, B.; Vielhauer, V.; et al. Cytotoxicity of crystals involves RIPK3-MLKL-mediated necroptosis. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Ma, H.; Shao, J.; Wu, J.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Huang, Z.; Ren, J.; Liu, S.; et al. A Role for Tubular Necroptosis in Cisplatin-Induced AKI. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2015, 26, 2647–2658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günther, C.; Christopher, P.; Kremer, A.E.; Murphy, J.M.; Petrie, E.J.; Amann, K.; Vandenabeele, P.; Linkermann, A.; Poremba, C.; Schleicher, U.; et al. The pseudokinase MLKL mediates programmed hepatocellular necrosis independently of RIPK3 during hepatitis. J. Clin. Investig. 2016, 126, 4346–4360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamon, A.; Piquet-Pellorce, C.; Dimanche-Boitrel, M.-T.; Samson, M.; Le Seyec, J. Intrahepatocytic necroptosis is dispensable for hepatocyte death in murine immune-mediated hepatitis. J. Hepatol. 2020, 73, 699–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dara, L.; Johnson, H.; Suda, J.; Win, S.; Gaarde, W.; Han, D.; Kaplowitz, N. Receptor interacting protein kinase 1 mediates murine acetaminophen toxicity independent of the necrosome and not through necroptosis. Hepatology 2015, 62, 1847–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, A.; Rousselle, A.; Becker, J.U.; von Mässenhausen, A.; Linkermann, A.; Kettritz, R. Necroptosis controls NET generation and mediates complement activation, endothelial damage, and autoimmune vasculitis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E9618–E9625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawlor, K.E.; Khan, N.; Mildenhall, A.; Gerlic, M.; Croker, B.A.; D’Cruz, A.A.; Hall, C.; Spall, S.K.; Anderton, H.; Masters, S.L.; et al. RIPK3 promotes cell death and NLRP3 inflammasome activation in the absence of MLKL. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.; Kumari, S.; Kim, C.; Van, T.-M.; Wachsmuth, L.; Polykratis, A.; Pasparakis, M. RIPK1 counteracts ZBP1-mediated necroptosis to inhibit inflammation. Nature 2016, 540, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polykratis, A.; Martens, A.; Eren, R.O.; Shirasaki, Y.; Yamagishi, M.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Uemura, S.; Miura, M.; Holzmann, B.; Kollias, G.; et al. A20 prevents inflammasome-dependent arthritis by inhibiting macrophage necroptosis through its ZnF7 ubiquitin-binding domain. Nat. Cell Biol. 2019, 21, 731–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzer, R.; Jiao, H.; Wachsmuth, L.; Tresch, A.; Pasparakis, M. FADD and Caspase-8 Regulate Gut Homeostasis and Inflammation by Controlling MLKL- and GSDMD-Mediated Death of Intestinal Epithelial Cells. Immunity 2020, 52, 978–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Shi, L.; Li, W.; Chen, K.; Li, M.; Chen, X.; Zhang, H.; Li, T.; Matsuzawa-Ishimoto, Y.; et al. Gut epithelial TSC1/mTOR controls RIPK3-dependent necroptosis in intestinal inflammation and cancer. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 130, 2111–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dannappel, M.; Vlantis, K.; Kumari, S.; Polykratis, A.; Kim, C.; Wachsmuth, L.; Eftychi, C.; Lin, J.; Corona, T.; Hermance, N.; et al. RIPK1 maintains epithelial homeostasis by inhibiting apoptosis and necroptosis. Nature 2014, 513, 90–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shindo, R.; Ohmuraya, M.; Komazawa-Sakon, S.; Miyake, S.; Deguchi, Y.; Yamazaki, S.; Nishina, T.; Yoshimoto, T.; Kakuta, S.; Koike, M.; et al. Necroptosis of Intestinal Epithelial Cells Induces Type 3 Innate Lymphoid Cell-Dependent Lethal Ileitis. iScience 2019, 15, 536–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez-Diaz, S.; Preaudet, A.; Samson, A.L.; Nguyen, P.M.; Fung, K.Y.; Garnham, A.L.; Alexander, W.S.; Strasser, A.; Ernst, M.; Putoczki, T.L.; et al. Necroptosis is dispensable for the development of inflammation-associated or sporadic colon cancer in mice. Cell Death Differ. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devos, M.; Tanghe, G.; Gilbert, B.; Dierick, E.; Verheirstraeten, M.; Nemegeer, J.; De Reuver, R.; Lefebvre, S.; De Munck, J.; Rehwinkel, J.; et al. Sensing of endogenous nucleic acids by ZBP1 induces keratinocyte necroptosis and skin inflammation. J. Exp. Med. 2020, 217, e20191913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najjar, M.; Saleh, D.; Zelic, M.; Nogusa, S.; Shah, S.; Tai, A.; Finger, J.N.; Polykratis, A.; Gough, P.J.; Bertin, J.; et al. RIPK1 and RIPK3 Kinases Promote Cell-Death-Independent Inflammation by Toll-like Receptor 4. Immunity 2016, 45, 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rickard, J.A.; Anderton, H.; Etemadi, N.; Nachbur, U.; Darding, M.; Peltzer, N.; Lalaoui, N.; E Lawlor, K.; Vanyai, H.; Hall, C.; et al. TNFR1-dependent cell death drives inflammation in Sharpin-deficient mice. eLife 2014, 3, e03464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tummers, B.; Mari, L.; Guy, C.S.; Heckmann, B.L.; Rodriguez, D.; Rühl, S.; Moretti, J.; Crawford, J.C.; Fitzgerald, P.; Kanneganti, T.-D.; et al. Caspase-8-Dependent Inflammatory Responses Are Controlled by Its Adaptor, FADD, and Necroptosis. Immunity 2020, 52, 994–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildebrand, J.M.; Kauppi, M.; Majewski, I.J.; Liu, Z.; Cox, A.J.; Miyake, S.; Petrie, E.J.; Silk, M.A.; Li, Z.; Tanzer, M.C.; et al. A missense mutation in the MLKL brace region promotes lethal neonatal inflammation and hematopoietic dysfunction. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitur, K.; Wachtel, S.; Brown, A.; Wickersham, M.; Paulino, F.; Peñaloza, H.F.; Soong, G.; Bueno, S.M.; Parker, D.; Prince, A. Necroptosis Promotes Staphylococcus aureus Clearance by Inhibiting Excessive Inflammatory Signaling. Cell Rep. 2016, 16, 2219–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Cruz, A.A.; Speir, M.; Bliss-Moreau, M.; Dietrich, S.; Wang, S.; Chen, A.A.; Gavillet, M.; Al-Obeidi, A.; Lawlor, K.E.; Vince, J.E.; et al. The pseudokinase MLKL activates PAD4-dependent NET formation in necroptotic neutrophils. Sci. Signal. 2018, 11, eaao1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stutz, M.D.; Ojaimi, S.; Allison, C.; Preston, S.; Arandjelovic, P.; Hildebrand, J.M.; Sandow, J.J.; Webb, A.I.; Silke, J.; Alexander, W.S.; et al. Necroptotic signaling is primed in Mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected macrophages, but its pathophysiological consequence in disease is restricted. Cell Death Differ. 2018, 25, 951–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Li, Y.; Wu, J.; Li, G.; Tao, X.; Lai, K.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zou, Z.; Xu, Y. RIPK3 collaborates with GSDMD to drive tissue injury in lethal polymicrobial sepsis. Cell Death Differ. 2020, 27, 2568–2585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sureshbabu, A.; Patino, E.; Ma, K.C.; Laursen, K.; Finkelsztein, E.J.; Akchurin, O.; Muthukumar, T.; Ryter, S.W.; Gudas, L.; Choi, A.M.K.; et al. RIPK3 promotes sepsis-induced acute kidney injury via mitochondrial dysfunction. JCI Insight 2018, 3, e98411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riegler, A.N.; Brissac, T.; Gonzalez-Juarbe, N.; Orihuela, C.J. Necroptotic Cell Death Promotes Adaptive Immunity Against Colonizing Pneumococci. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Juarbe, N.; Gilley, R.P.; Hinojosa, C.A.; Bradley, K.M.; Kamei, A.; Gao, G.; Dube, P.H.; Bergman, M.A.; Orihuela, C.J. Pore-Forming Toxins Induce Macrophage Necroptosis during Acute Bacterial Pneumonia. PLoS Pathog. 2015, 11, e1005337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sai, K.; Parsons, C.; House, J.S.; Kathariou, S.; Ninomiya-Tsuji, J. Necroptosis mediators RIPK3 and MLKL suppress intracellular Listeria replication independently of host cell killing. J. Cell Biol. 2019, 218, 1994–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.-X.; Chen, W.; Liu, Z.-Z.; Zhou, F.-H.; Yan, S.-Q.; Hu, G.-Q.; Qin, X.-X.; Zhang, J.; Ma, K.; Du, C.-T.; et al. Non-Hematopoietic MLKL Protects Against Salmonella Mucosal Infection by Enhancing Inflammasome Activation. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogusa, S.; Thapa, R.J.; Dillon, C.P.; Liedmann, S.; Oguin, T.H.; Ingram, J.P.; Rodriguez, D.; Kosoff, R.; Sharma, S.; Sturm, O.; et al. RIPK3 Activates Parallel Pathways of MLKL-Driven Necroptosis and FADD-Mediated Apoptosis to Protect against Influenza A Virus. Cell Host Microbe 2016, 20, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shubina, M.; Tummers, B.; Boyd, D.F.; Zhang, T.; Yin, C.; Gautam, A.; Guo, X.-Z.J.; Rodriguez, D.A.; Kaiser, W.J.; Vogel, P.; et al. Necroptosis restricts influenza A virus as a stand-alone cell death mechanism. J. Exp. Med. 2020, 217, e20191259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-H.; Platt, M.P.; Gilley, R.P.; Brown, D.; Dube, P.H.; Yu, Y.; Gonzalez-Juarbe, N. Influenza Causes MLKL-Driven Cardiac Proteome Remodeling During Convalescence. Circ. Res. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Juarbe, N.; Riegler, A.N.; Jureka, A.S.; Gilley, R.P.; Brand, J.D.; Trombley, J.E.; Scott, N.R.; Platt, M.P.; Dube, P.H.; Petit, C.M.; et al. Influenza-Induced Oxidative Stress Sensitizes Lung Cells to Bacterial-Toxin-Mediated Necroptosis. Cell Rep. 2020, 32, 108062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, B.P.; Snyder, A.G.; Olsen, T.M.; Orozco, S.L.; Oguin, T.H.; Tait, S.; Martinez, J.; Gale, M.; Loo, Y.-M.; Oberst, A. RIPK3 Restricts Viral Pathogenesis via Cell Death-Independent Neuroinflammation. Cell 2017, 169, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsurusaki, S.; Tsuchiya, Y.; Koumura, T.; Nakasone, M.; Sakamoto, T.; Matsuoka, M.; Imai, H.; Kok, C.Y.-Y.; Okochi, H.; Nakano, H.; et al. Hepatic ferroptosis plays an important role as the trigger for initiating inflammation in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, W.K.; Jun, D.W.; Jang, K.; Oh, J.H.; Chae, Y.J.; Lee, J.S.; Koh, D.H.; Kang, H.T. Decrease in fat de novo synthesis and chemokine ligand expression in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease caused by inhibition of mixed lineage kinase domain-like pseudokinase. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 34, 2206–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Poulsen, K.L.; Sanz-Garcia, C.; Huang, E.; McMullen, M.R.; Roychowdhury, S.; Dasarathy, S.; Nagy, L.E. MLKL-dependent signaling regulates autophagic flux in a murine model of non-alcohol-associated fatty liver and steatohepatitis. J. Hepatol. 2020, 73, 616–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyata, T.; Wu, X.; Fan, X.; Huang, E.; Sanz-Garcia, C.; Ross, C.K.C.-D.; Roychowdhury, S.; Bellar, A.; McMullen, M.R.; Dasarathy, J.; et al. Differential role of MLKL in alcohol-associated and non-alcohol-associated fatty liver diseases in mice and humans. JCI Insight 2021, 6, e140180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Du, X.; Liu, G.; Huang, S.; Du, W.; Zou, S.; Tang, D.; Fan, C.; Xie, Y.; Wei, Y.; et al. The pseudokinase MLKL regulates hepatic insulin sensitivity independently of inflammation. Mol. Metab. 2019, 23, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasheed, A.; Robichaud, S.; Nguyen, M.-A.; Geoffrion, M.; Wyatt, H.; Cottee, M.L.; Dennison, T.; Pietrangelo, A.; Lee, R.; Lagace, T.A.; et al. Loss of MLKL (Mixed Lineage Kinase Domain-Like Protein) Decreases Necrotic Core but Increases Macrophage Lipid Accumulation in Atherosclerosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2020, 40, 1155–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brumatti, G.; Ma, C.; Lalaoui, N.; Nguyen, N.-Y.; Navarro, M.; Tanzer, M.C.; Richmond, J.; Ghisi, M.; Salmon, J.M.; Silke, N.; et al. The caspase-8 inhibitor emricasan combines with the SMAC mimetic birinapant to induce necroptosis and treat acute myeloid leukemia. Sci. Transl. Med. 2016, 8, 339ra69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Yu, X.; Li, M.; Liu, Y.; Han, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, X.M.; Wu, X.; Qin, J.; Fang, J.; et al. MLKL attenuates colon inflammation and colitis-tumorigenesis via suppression of inflammatory responses. Cancer Lett. 2019, 459, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Cheng, X.; Guo, J.; Bi, Y.; Kuang, L.; Ren, J.; Zhong, J.; Pan, L.; Zhang, X.; Guo, Y.; et al. MLKL inhibits intestinal tumorigenesis by suppressing STAT3 signaling pathway. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 17, 869–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Fan, C.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, Q.; Liu, Y.; Xu, C.; Xie, Q.; Wu, X.; Yu, X.; Zhang, J.; et al. MLKL and FADD Are Critical for Suppressing Progressive Lymphoproliferative Disease and Activating the NLRP3 Inflammasome. Cell Rep. 2016, 16, 3247–3259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Diaz, S.; Dillon, C.P.; Lalaoui, N.; Tanzer, M.C.; Rodriguez, D.; Lin, A.; Lebois, M.; Hakem, R.; Josefsson, E.; O’Reilly, L.A.; et al. The Pseudokinase MLKL and the Kinase RIPK3 Have Distinct Roles in Autoimmune Disease Caused by Loss of Death-Receptor-Induced Apoptosis. Immunity 2016, 45, 513–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Perera, N.D.; Chiam, M.D.F.; Cuic, B.; Wanniarachchillage, N.; Tomas, D.; Samson, A.L.; Cawthorne, W.; Valor, E.N.; Murphy, J.M.; et al. Necroptosis is dispensable for motor neuron degeneration in a mouse model of ALS. Cell Death Differ. 2020, 27, 1728–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, Z.; Pan, C.; Shao, T.; Liu, L.; Li, L.; Guo, D.; Zhang, S.; Yuan, T.; Cao, R.; Jiang, Z.; et al. Mixed Lineage Kinase Domain-like Protein MLKL Breaks Down Myelin following Nerve Injury. Mol. Cell 2018, 72, 457–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Su, Y.; Ying, Z.; Guo, D.; Pan, C.; Guo, J.; Zou, Z.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, Z.; et al. RIP1 kinase inhibitor halts the progression of an immune-induced demyelination disease at the stage of monocyte elevation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 5675–5680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Q.-S.; Chen, P.; Wang, W.-X.; Lin, C.-C.; Zhou, Y.; Yu, L.-H.; Lin, Y.-X.; Xu, Y.-F.; Kang, D.-Z. RIP1/RIP3/MLKL mediates dopaminergic neuron necroptosis in a mouse model of Parkinson disease. Lab. Investig. 2020, 100, 503–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, S.; Zhang, W.; Cai, G.; Ding, Y.; Wei, C.; Li, S.; Yang, Y.; Qin, J.; Liu, D.; Zhang, H.; et al. Myofiber necroptosis promotes muscle stem cell proliferation via releasing Tenascin-C during regeneration. Cell Res. 2020, 30, 1063–1077. [Google Scholar]

- Nakazawa, D.; Desai, J.; Steiger, S.; Müller, S.; Devarapu, S.K.; Mulay, S.R.; Iwakura, T.; Anders, H.-J. Activated platelets induce MLKL-driven neutrophil necroptosis and release of neutrophil extracellular traps in venous thrombosis. Cell Death Discov. 2018, 4, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moujalled, D.; Gangatirkar, P.; Kauppi, M.; Corbin, J.; Lebois, M.; Murphy, J.M.; Lalaoui, N.; Hildebrand, J.M.; Silke, J.; Alexander, W.S.; et al. The necroptotic cell death pathway operates in megakaryocytes, but not in platelet synthesis. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Meng, L.; Xu, T.; Su, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, X. RIPK1-RIPK3-MLKL-dependent necrosis promotes the aging of mouse male reproductive system. eLife 2017, 6, e27692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webster, J.D.; Kwon, Y.C.; Park, S.; Zhang, H.; Corr, N.; Ljumanovic, N.; Adedeji, A.O.; Varfolomeev, E.; Goncharov, T.; Preston, J.; et al. RIP1 kinase activity is critical for skin inflammation but not for viral propagation. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2020, 107, 941–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siempos, I.I.; Ma, K.C.; Imamura, M.; Baron, R.M.; Fredenburgh, L.E.; Huh, J.-W.; Moon, J.-S.; Finkelsztein, E.J.; Jones, D.S.; Lizardi, M.T.; et al. RIPK3 mediates pathogenesis of experimental ventilator-induced lung injury. JCI Insight 2018, 3, e97102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imamura, M.; Moon, J.-S.; Chung, K.-P.; Nakahira, K.; Muthukumar, T.; Shingarev, R.; Ryter, S.W.; Choi, A.M.; Choi, M.E. RIPK3 promotes kidney fibrosis via AKT-dependent ATP citrate lyase. JCI Insight 2018, 3, e94979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luedde, T.; Kaplowitz, N.; Schwabe, R.F. Cell death and cell death responses in liver disease: Mechanisms and clinical relevance. Gastroenterology 2014, 147, 765–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yan, R.; Tian, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, M.; Cui, Q.; Zhao, L.; Hu, R.; et al. Receptor-interacting protein kinase 3 promotes platelet activation and thrombosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 2964–2969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, T.; Dewitz, C.; Schmitz, J.; Schröder, A.S.; Bräsen, J.H.; Stockwell, B.R.; Murphy, J.M.; Kunzendorf, U.; Krautwald, S. Necroptosis and ferroptosis are alternative cell death pathways that operate in acute kidney failure. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2017, 74, 3631–3645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasegawa, T.; Ito, Y.; Wijeweera, J.; Liu, J.; Malle, E.; Farhood, A.; McCuskey, R.S.; Jaeschke, H. Reduced inflammatory response and increased microcirculatory disturbances during hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury in steatotic livers of ob/ob mice. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2007, 292, G1385–G1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierotti, C.L.; Tanzer, M.C.; Jacobsen, A.V.; Hildebrand, J.M.; Garnier, J.-M.; Sharma, P.; Lucet, I.S.; Cowan, A.D.; Kersten, W.J.A.; Luo, M.-X.; et al. Potent Inhibition of Necroptosis by Simultaneously Targeting Multiple Effectors of the Pathway. ACS Chem. Biol. 2020, 15, 2702–2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandpur, R.; Carmona-Rivera, C.; Vivekanandan-Giri, A.; Gizinski, A.; Yalavarthi, S.; Knight, J.S.; Friday, S.; Li, S.; Patel, R.M.; Subramanian, V.; et al. NETs are a source of citrullinated autoantigens and stimulate inflammatory responses in rheumatoid arthritis. Sci. Transl. Med. 2013, 5, 178ra40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majdi, A.; Aoudjehane, L.; Ratziu, V.; Islam, T.; Afonso, M.B.; Conti, F.; Mestiri, T.; Lagouge, M.; Foufelle, F.; Ballenghien, F.; et al. Inhibition of receptor-interacting protein kinase 1 improves experimental non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Hepatol. 2020, 72, 627–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karunakaran, D.; Turner, A.W.; Duchez, A.-C.; Soubeyrand, S.; Rasheed, A.; Smyth, D.; Cook, D.P.; Nikpay, M.; Kandiah, J.W.; Pan, C.; et al. RIPK1 gene variants associate with obesity in humans and can be therapeutically silenced to reduce obesity in mice. Nat. Metab. 2020, 2, 1113–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, Y.; Ofengeim, D.; Najafov, A.; Das, S.; Saberi, S.; Li, Y.; Hitomi, J.; Zhu, H.; Chen, H.; Mayo, L.; et al. RIPK1 mediates axonal degeneration by promoting inflammation and necroptosis in ALS. Science 2016, 353, 603–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chevin, M.; Sébire, G. Necroptosis in ALS: A hot topic in-progress. Cell Death Discov. 2021, 7, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanzer, M.C.; Tripaydonis, A.; Webb, A.I.; Young, S.N.; Varghese, L.N.; Hall, C.; Alexander, W.S.; Hildebrand, J.M.; Silke, J.; Murphy, J.M. Necroptosis signalling is tuned by phosphorylation of MLKL residues outside the pseudokinase domain activation loop. Biochem. J. 2015, 471, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoglen, N.C.; Chen, L.-S.; Fisher, C.D.; Hirakawa, B.P.; Groessl, T.; Contreras, P.C. Characterization of IDN-6556 (3-[2-(2-tert-butyl-phenylaminooxalyl)-amino]-propionylamino]-4-oxo-5-(2,3,5,6-tetrafluoro-phenoxy)-pentanoic acid): A liver-targeted caspase inhibitor. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2004, 309, 634–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Ai, Y.; Guo, J.; Dong, B.; Li, L.; Cai, G.; Chen, S.; Xu, D.; Wang, F.; Wang, X. Casein kinase 1G2 suppresses necroptosis-promoted testis aging by inhibiting receptor-interacting kinase 3. eLife 2020, 9, e61564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berghe, T.V.; Kaiser, W.J.; Bertrand, M.J.; Vandenabeele, P. Molecular crosstalk between apoptosis, necroptosis, and survival signaling. Mol. Cell. Oncol. 2015, 2, e975093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, S.J.; Lemire, P.; Maughan, H.; Goethel, A.; Turpin, W.; Bedrani, L.; Guttman, D.S.; Croitoru, K.; Girardin, S.E.; Philpott, D.J. Comparison of Co-housing and Littermate Methods for Microbiota Standardization in Mouse Models. Cell Rep. 2019, 27, 1910–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, S.L.; Flanagan, K.L. Sex differences in immune responses. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 16, 626–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, A.C.; Goldstein, D.R.; Montgomery, R.R. Age-dependent dysregulation of innate immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2013, 13, 875–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadioglu, A.; Cuppone, A.M.; Trappetti, C.; List, T.; Spreafico, A.; Pozzi, G.; Andrew, P.W.; Oggioni, M.R. Sex-based differences in susceptibility to respiratory and systemic pneumococcal disease in mice. J. Infect. Dis. 2011, 204, 1971–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrie, E.J.; Sandow, J.J.; Jacobsen, A.V.; Smith, B.J.; Griffin, M.D.W.; Lucet, I.S.; Dai, W.; Young, S.N.; Tanzer, M.C.; Wardak, A.; et al. Conformational switching of the pseudokinase domain promotes human MLKL tetramerization and cell death by necroptosis. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, K.A.; FitzGibbon, C.; Young, S.N.; Garnish, S.E.; Yeung, W.; Coursier, D.; Birkinshaw, R.W.; Sandow, J.J.; Lehmann, W.I.L.; Liang, L.-Y.; et al. Distinct pseudokinase domain conformations underlie divergent activation mechanisms among vertebrate MLKL orthologues. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanzer, M.C.; Matti, I.; Hildebrand, J.M.; Young, S.N.; Wardak, A.; Tripaydonis, A.; Petrie, E.J.; Mildenhall, A.L.; Vaux, D.L.; E Vince, J.; et al. Evolutionary divergence of the necroptosis effector MLKL. Cell Death Differ. 2016, 23, 1185–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martens, S.; Hofmans, S.; Declercq, W.; Augustyns, K.; Vandenabeele, P. Inhibitors Targeting RIPK1/RIPK3: Old and New Drugs. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2020, 41, 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weisel, K.; Berger, S.; Thorn, K.; Taylor, P.C.; Peterfy, C.; Siddall, H.; Tompson, D.; Wang, S.; Quattrocchi, E.; Burriss, S.W.; et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled experimental medicine study of RIPK1 inhibitor GSK2982772 in patients with moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2021, 23, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).