Jet X-Ray Properties of EXO 1846-031 During Its 2019 Outburst

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Disk–Jet Connection and Spectral States

3. Estimation of Jet X-Ray Flux

TCAF with an Additional Power-Law Model

4. Observation and Results

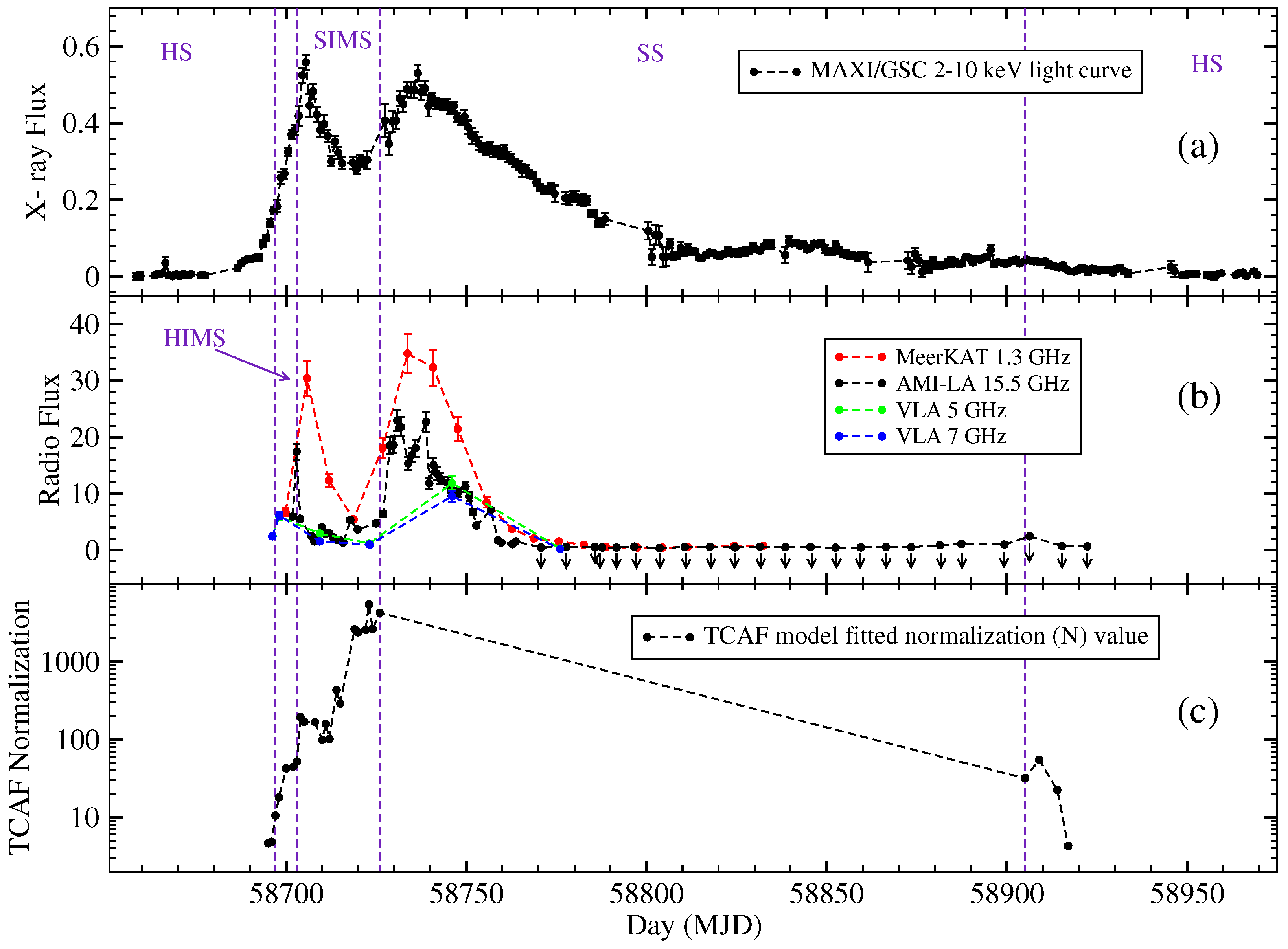

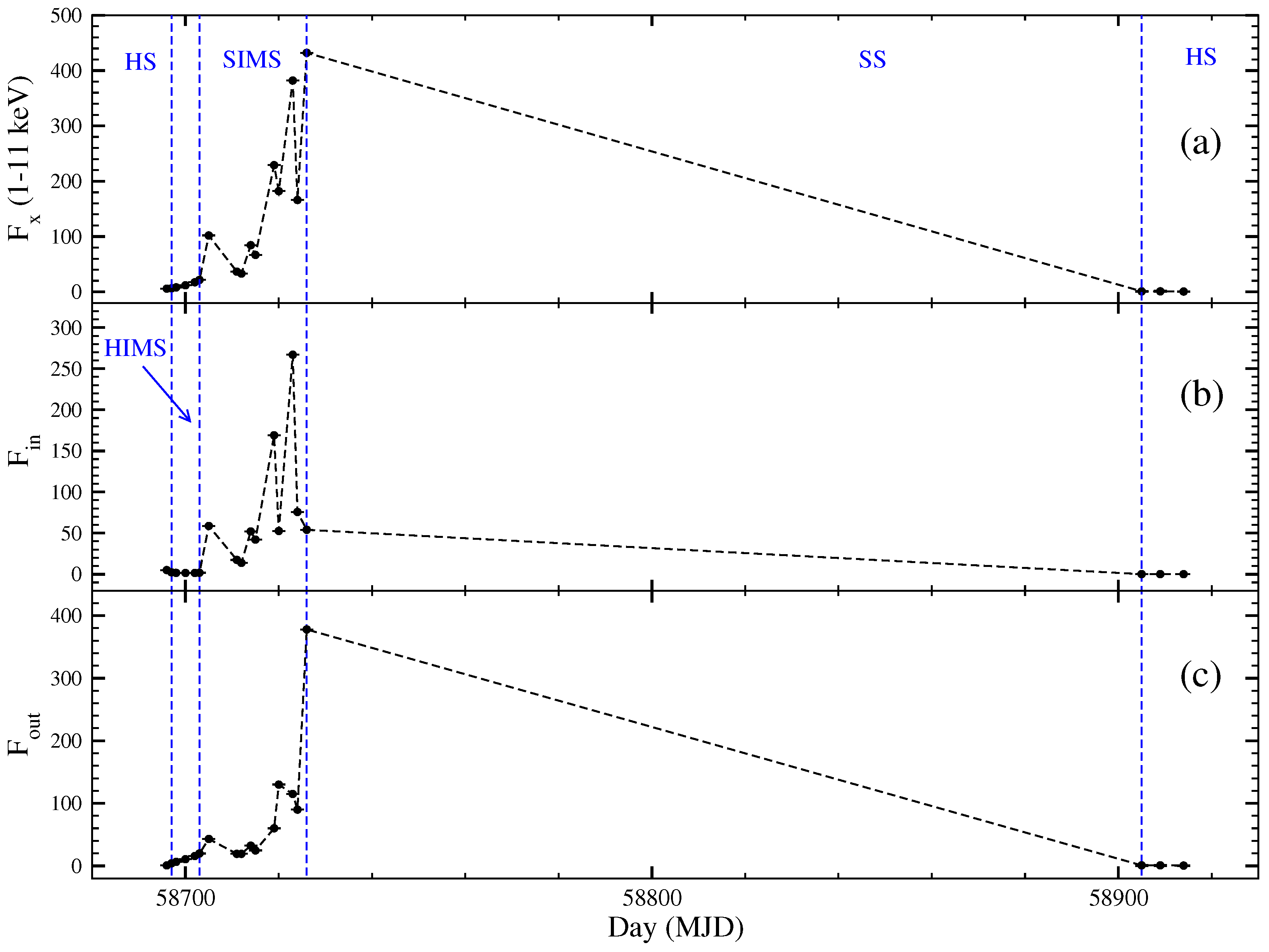

4.1. Evolution of Jet X-Rays

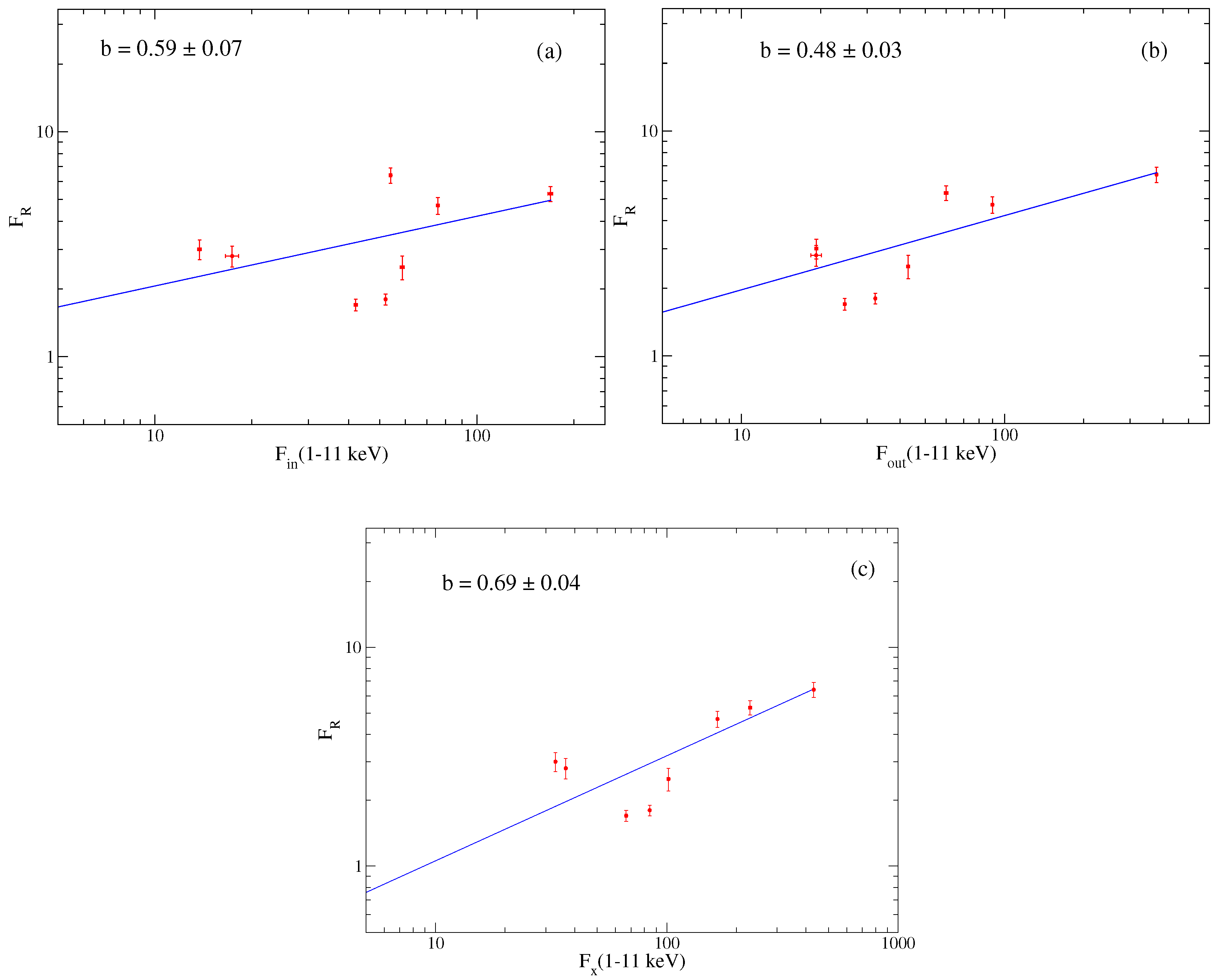

4.2. Correlation Between the X-Ray and Radio

| Obs. ID (1) | Satellite/ Instrument (2) | Date a of Obs. (3) | Day (MJD) (4) | N b (5) |

c (6) | c (7) |

c (8) |

c (9) | R c (10) | c (11) | c (12) | d (13) | d (14) | d (15) | Percentage (16) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2200760102 | Nicer | 2019-08-01 | 58696 | 4.82±0.04 | 0.294±0.007 | 0.995±0.008 | 9.90±0.08 | 386.27±1.50 | 1.46±0.02 | 5.97±0.34 | 844/879 | 5.84±0.47 | 5.04±0.41 | 0.80±0.06 | 13.70 |

| 00011500002 | XRT+GSC | 2019-08-02 | 58697 | 10.52±0.06 | 0.346±0.008 | 0.710±0.015 | 8.29±0.11 | 325.42±1.70 | 1.52±0.06 | 6.18±0.90 | 611/590 | 6.25±0.33 | 2.31±0.12 | 3.94±0.21 | 63.00 |

| 2200760104 | Nicer | 2019-08-03 | 58698 | 18.01±0.03 | 0.396±0.010 | 0.523±0.007 | 8.02±0.04 | 272.39±1.80 | 1.50±0.01 | 5.81±0.48 | 932/916 | 8.05±0.11 | 1.65±0.23 | 6.40±0.10 | 79.49 |

| 00011500003 | XRT+GSC | 2019-08-05 | 58700 | 42.53±0.16 | 0.577±0.012 | 0.358±0.011 | 6.95±0.08 | 182.27±2.44 | 1.22±0.03 | 6.89±1.00 | 743/634 | 12.04±0.46 | 1.46±0.56 | 10.58±0.41 | 87.85 |

| 2200760108 | Nicer+GSC | 2019-08-07 | 58702 | 44.65±0.06 | 0.766±0.015 | 0.236±0.013 | 10.22±0.08 | 91.69±1.80 | 1.08±0.02 | 6.55±0.39 | 990/907 | 17.36±0.20 | 1.56±0.20 | 15.81±0.21 | 91.04 |

| 00011500006 | XRT+GSC | 2019-08-08 | 58703 | 51.92±0.06 | 0.769±0.024 | 0.237±0.011 | 9.18±0.07 | 87.33±2.05 | 1.09±0.04 | 8.00±0.33 | 665/583 | 21.56±0.30 | 1.75±0.21 | 19.81±0.24 | 91.88 |

| 00011500008 | XRT+GSC | 2019-08-10 | 58705 | 168.42±0.22 | 0.610±0.015 | 0.092±0.009 | 7.44±0.04 | 25.29±1.50 | 1.05±0.05 | 10.14±1.10 | 694/615 | 101.71±1.50 | 58.66±0.78 | 43.05±0.57 | 42.33 |

| 2200760117 | Nicer | 2019-08-16 | 58711 | 158.32±0.07 | 0.350±0.014 | 0.117±0.019 | 11.54±0.10 | 23.37±2.10 | 1.05±0.04 | 7.74±0.09 | 894/983 | 36.61±0.40 | 17.38±0.80 | 19.23±0.89 | 52.52 |

| 2200760118 | Nicer | 2019-08-17 | 58712 | 101.21±0.13 | 0.400±0.012 | 0.111±0.007 | 11.10±0.09 | 26.82±1.90 | 1.10±0.06 | 7.66±2.02 | 884/965 | 33.02±0.40 | 13.77±0.18 | 19.25±0.25 | 58.29 |

| 2200760120 | Nicer | 2019-08-19 | 58714 | 434.09±0.29 | 0.360±0.011 | 0.060±0.018 | 11.90±0.16 | 20.10±2.20 | 1.10±0.05 | 8.94±1.02 | 1041/941 | 84.34±0.57 | 52.08±0.35 | 32.26±0.22 | 38.25 |

| 00011500016 | XRT+GSC | 2019-08-20 | 58715 | 289.29±0.35 | 0.454±0.013 | 0.074±0.009 | 7.88±0.07 | 23.26±1.90 | 1.05±0.03 | 9.59±0.78 | 622/574 | 66.76±0.82 | 42.07±0.52 | 24.69±0.30 | 36.99 |

| 00011500017 | XRT+GSC | 2019-08-23 | 58719 | 2601.40±0.44 | 0.342±0.016 | 0.050±0.011 | 11.59±0.19 | 16.23±2.50 | 1.05±0.03 | 7.89±0.64 | 571/499 | 229.31±3.86 | 169.31±2.85 | 60.00±1.00 | 26.17 |

| 2200760126 | Nicer | 2019-08-25 | 58720 | 2376.86±0.36 | 0.410±0.030 | 0.052±0.012 | 11.95±0.18 | 27.44±2.30 | 1.05±0.02 | 9.83±0.24 | 864/756 | 182.18±3.00 | 52.62±0.80 | 129.56±1.97 | 71.12 |

| 00088981001 | XRT+GSC | 2019-08-27 | 58723 | 5433.06±0.39 | 0.376±0.005 | 0.050±0.011 | 12.00±0.07 | 15.89±1.40 | 1.10±0.05 | 7.86±1.21 | 548/500 | 382.29±2.72 | 267.43±1.9 | 114.86±5.16 | 30.05 |

| 2200760130 | Nicer | 2019-08-29 | 58724 | 2613.99±0.26 | 0.350±0.025 | 0.044±0.017 | 11.50±0.30 | 20.00±3.100 | 1.05±0.03 | 7.04±1.02 | 655/473 | 165.62±1.67 | 75.72±0.76 | 89.90±0.91 | 54.28 |

| 2200760132 | Nicer | 2019-08-31 | 58726 | 4243.69±0.37 | 0.380±0.018 | 0.050±0.011 | 8.51±0.14 | 27.47±2.90 | 1.05±0.05 | 7.27±0.53 | 815/638 | 432.13±3.75 | 53.97±0.47 | 378.17±3.28 | 87.51 |

| 00011500030 | XRT+GSC | 2020-02-26 | 58905 | 31.75±0.23 | 0.058±0.005 | 0.220±0.004 | 7.31±0.15 | 272.47±5.40 | 2.31±0.04 | 4.79±0.42 | 195/175 | 0.91±0.09 | 0.13±0.01 | 0.78±0.01 | 85.75 |

| 00011500031 | XRT+GSC | 2020-03-01 | 58909 | 55.86±0.13 | 0.075±0.002 | 0.200±0.003 | 9.57±0.25 | 263.36±8.50 | 1.89±0.05 | 5.73±2.30 | 140/158 | 0.94±0.09 | 0.09±0.01 | 0.85±0.09 | 90.29 |

| 00011500032 | XRT+GSC | 2020-03-05 | 58914 | 22.48±0.06 | 0.031±0.002 | 0.230±0.006 | 11.47±0.13 | 241.26±9.50 | 2.78±0.07 | 5.06±2.12 | 103/123 | 0.53±0.05 | 0.10±0.01 | 0.43±0.02 | 81.32 |

| 00011500033 * | XRT+GSC | 2020-03-09 | 58917 | 4.31±0.05 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chakrabarti, S.K.; Debnath, D.; Nagarkoti, S. Delayed outburst of H 1743-322 in 2003 and relation with its other outbursts. Adv. Space Res. 2019, 63, 3749–3759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhowmick, R.; Debnath, D.; Chatterjee, K.; Nagarkoti, S.; Chakrabarti, S.K.; Sarkar, R.; Chatterjee, D.; Jana, A. Relation Between Quiescence and Outbursting Properties of GX 339-4. Astrophys. J. 2021, 910, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakura, N.I.; Sunyaev, R.A. Black holes in binary systems. Observational appearance. Astron. Astrophys. 1973, 24, 337–355. [Google Scholar]

- Chakrabarti, S.K.; Titarchuk, L.G. Spectral Properties of Accretion Disks around Galactic and Extragalactic Black Holes. Astrophys. J. 1995, 455, 623–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarti, S.K. Spectral Properties of Accretion Disks around Black Holes. II. Sub-Keplerian Flows with and without Shocks. Astrophys. J. 1997, 484, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Debnath, D.; Mondal, S.; Chakrabarti, S.K. Characterization of GX 339-4 outburst of 2010–11: Analysis by xspec using two component advective flow model. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2015, 447, 1984–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Debnath, D.; Jana, A.; Chakrabarti, S.K.; Chatterjee, D.; Mondal, S. Accretion Flow Properties of Swift J1753.5-0127 during Its 2005 Outburst. Astrophys. J. 2017, 850, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homan, J.; Belloni, T. The Evolution of Black Hole States. Astrophys. Space Sci. 2005, 300, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandi, A.; Debnath, D.; Mandal, S.; Chakrabarti, S.K. Accretion Flow Dynamics during the Evolution of Timing and Spectral Properties of GX 339-4 during its 2010–11 Outburst. Astron. Astrophys. 2012, 542, A56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motta, S.; Belloni, T.; Homan, J. The Evolution of the High-Energy Cut-Off in the X-ray Spectrum of GX 339-4 across a Hard-to-Soft Transition. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2009, 400, 1603–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fender, R.P.; Gallo, E. An Overview of Jets and Outflows in Stellar Mass Black Holes. Space Sci. Rev. 2014, 183, 323–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarti, S.K. Estimation and effects of the mass outflow from shock compressed flow around compact objects. Astron. Astrophys. 1999, 351, 185. [Google Scholar]

- Debnath, D.; Chatterjee, K.; Chatterjee, D.; Jana, A.; Chakrabarti, S.K. Jet properties of XTE J1752-223 during its 2009–2010 outburst. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2021, 504, 4242–4251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merloni, A.; Heinz, S.; Di Matteo, T. A Fundamental Plane of black hole activity. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2003, 345, 1057–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Körding, E.; Jester, S.; Fender, R. Accretion states and radio loudness in active galactic nuclei: Analogies with X-ray binaries. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2006, 372, 1366–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbel, S.; Coriat, M.; Brocksopp, C.; Tzioumis, A.K.; Fender, R.P.; Tomsick, J.A.; Buxton, M.M.; Bailyn, C.D. Formation of the Compact Jets in the Black Hole GX 339-4. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. Lett. 2013, 431, L107–L111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjellming, R.M.; Gibson, D.M.; Owen, F.N. Another Major Change in the Radio Source Associated with Cyg X-1. Nature 1975, 256, 111–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirabel, I.F.; Rodriguez, L.F.; Cordier, B.; Paul, J.; Lebrun, F. A Double-Sided Radio Jet from the Compact Galactic Centre Annihilator 1E1740.7-2942. Nature 1992, 358, 215–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurent, P.; Rodriguez, J.; Wilms, J.; Cadolle Bel, M.; Pottschmidt, K.; Grinberg, V. Polarized Gamma-Ray Emission from the Galactic Black Hole Cygnus X-1. Science 2011, 332, 438–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbel, S.; Dubus, G.; Tomsick, J.A.; Szostek, A.; Coriat, M.; Fender, R.P.; Tzioumis, A.K.; Brocksopp, C.; Sivakoff, G.R.; Smith, R.J.; et al. A Giant Radio Flare from Cygnus X-3 with Associated γ-Ray Emission. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2012, 421, 2947–2955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stirling, A.M.; Spencer, R.E.; De La Force, C.J.; Garrett, M.A.; Fender, R.P.; Ogley, R.N. A relativistic jet from Cygnus X-1 in the low/hard X-ray state. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2001, 327, 1273–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhawan, V.; Mirabel, I.F.; Rodriguez, L.F. AU-Scale Synchrotron Jets and Superluminal Ejecta in GRS 1915+105. Astrophys. J. 2000, 543, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jourdain, E.; Roques, J.P.; Chauvin, M.; Clark, D.J. Separation of Two Contributions to the High Energy Emission of Cygnus X-1: Polarization Measurements with INTEGRAL SPI. Astrophys. J. 2012, 761, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, A.; Corbel, S.; Dubus, G.; Rodriguez, J.; Grenier, I.; Hovatta, T.; Pearson, T.; Readhead, A.; Fender, R.; Mooley, K. High-energy gamma-ray observations of the accreting black hole V404 Cygni during its 2015 June outburst. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2016, 462, L111–L115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blandford, R.D.; Rees, M.J. A ‘Twin-Exhaust’ Model for Double Radio Sources. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 1974, 169, 395–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blandford, R.D.; Znajek, R.L. Electromagnetic extraction of energy from Kerr black holes. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 1977, 179, 433–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Znajek, R.L. The electric and magnetic conductivity of a Kerr hole. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 1978, 185, 833–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blandford, R.D.; Payne, D.G. Hydromagnetic flows from accretion discs and the production of radio jets. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 1982, 199, 883–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, T.; Chakrabarti, S.K. Mass outflow rate from accretion discs around compact objects. Class. Quantum Gravity 1999, 16, 3879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chakrabarti, S.K.; Nandi, A. Fundamental States of Accretion/Jet Configuration and the Black Hole Candidate GRS1915+105. Indian J. Phys. 2000, 75, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Chakrabarti, S.K. Jets, Disks and Spectral States of Black Holes. AIP Conf. Proc. 2001, 558, 831–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarti, S.K. Latest trends in the study of accretion and outflows around compact objects. Indian J. Phys. 1999, 73B, 931. [Google Scholar]

- Fender, R.P.; Belloni, T.M.; Gallo, E. Towards a Unified Model for Black Hole X-ray Binary Jets. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2004, 355, 1105–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannikainen, D.C.; Hunstead, R.W.; Campbell-Wilson, D.; Sood, R.K. MOST Radio Monitoring of GX 339-4. Astron. Astrophys. 1998, 337, 460. [Google Scholar]

- Corbel, S.; Nowak, M.A.; Fender, R.P.; Fender, R.P.; Tzioumis, A.K.; Markoff, S. Radio/X-ray correlation in the low/hard state of GX 339-4. Astron. Astrophys. 2003, 400, 1007–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbel, S.; Coriat, M.; Brocksopp, C.; Brocksopp, C.; Tzioumis, A.K.; Fender, R.P.; Tomsick, J.A.; Buxton, M.M.; Bailyn, C.D. The ‘universal’ radio/X-ray flux correlation: The case study of the black hole GX 339-4. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2013, 428, 2500–2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, E.; Fender, R.; Pooley, G. A Universal Radio-X-ray Correlation in Low/Hard State Black Hole Binaries. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2003, 344, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, A.N.; White, N.E. EXO 1846-031. IAU Circ. 1985, 4051, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Parmar, A.N.; Angelini, L.; Roche, P.; White, N.E. The discovery and properties of the ultra-soft X-ray transient EXO 1846-031. Astron. Astrophys. 1993, 279, 179–187. [Google Scholar]

- Negoro, H.; Nakajima, M.; Sugita, S.; Sasaki, R.; Mihara, W.I.T.; Maruyama, W.; Aoki, M.; Kobayashi, K.; Tamagawa, T.; Matsuoka, M.; et al. MAXI/GSC detection of renewed activity of the black hole candidate EXO 1846-031 after 34 years. Astron. Telegr. 2019, 12968, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Draghis, P.A.; Miller, J.M.; Cackett, E.M.; Kammoun, E.S.; Reynolds, M.T.; Tomsick, J.A.; Zoghbi, A. A New Spin on an Old Black Hole: NuSTAR Spectroscopy of EXO 1846-031. Astrophys. J. 2020, 900, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ji, L.; García, J.A.; Dauser, T.; Mendez, M.; Mao, J.; Tao, L.; Altamirano, D.; Maggi, P.; Zhang, S.N.; et al. A Variable Ionized Disk Wind in the Black Hole Candidate EXO 1846-031. Astrophys. J. 2021, 906, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strohmayer, T.E.; NICER Observatory Science Working Group. Evidence for High Frequency QPOs in the Black Hole Candidate EXO 1846-031. Am. Astron. Soc. Meet. Abstr. 2020, 235, 159.02. [Google Scholar]

- Nath, S.K.; Debnath, D.; Chatterjee, K.; Bhowmick, R.; Chang, H.K.; Chakrabarti, S.K. (Paper I) Accretion Flow Properties of EXO 1846-031 During its Multi-Peaked Outburst After Long Quiescence. Astrophys. J. 2024, 960, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.R.A.; Motta, S.E.; Fender, R.; Miller-Jones, J.C.A.; Neilsen, J.; Allison, J.R.; Bright, J.; Heywood, I.; Jacob, P.F.L.; Rhodes, L.; et al. Radio observations of the Black Hole X-ray Binary EXO 1846-031 re-awakening from a 34-year slumber. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2022, 517, 2801–2817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jana, A.; Chakrabarti, S.K.; Debnath, D. Properties of X-Ray Flux of Jets during the 2005 Outburst of Swift J1753.5-0127 Using the TCAF Solution. Astrophys. J. 2017, 850, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarti, S.K. Spectral softening due to winds in accretion disks. Indian J. Phys. B 1998, 72, 565. [Google Scholar]

- Markoff, S.; Nowak, M.A.; Wilms, J. Going with the flow: Can the base of jets subsume the role of compact accretion disk coronae? Astrophys. J. 2005, 635, 1203–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, D.M.; Maitra, D.; Dunn, R.J.H.; Markoff, S. Evidence for a compact jet dominating the broad-band spectrum of the black hole accretor XTE J1550-564. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2010, 402, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarti, S.K. Generalized Accretion Flow Configuration: Rationale and Observational Evidences. AIP Conf. Proc. 2010, 1206, 244–262. [Google Scholar]

- Dihingia, I.K.; Vaidya, B. Properties of the Accretion Disc, Jet and Disc-Wind around Kerr Black Hole. J. Astrophys. Astron. 2022, 43, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandi, A.; Chakrabarti, S.K.; Vadawale, S.V.; Rao, A.R. Ejection of the inner accretion disk in GRS 1915+105: The magnetic rubber-band effect. Astron. Astrophys. 2001, 380, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bhowmick, R.; Nath, S.K.; Debnath, D.; Chang, H.-K. Jet X-Ray Properties of EXO 1846-031 During Its 2019 Outburst. Universe 2025, 11, 398. https://doi.org/10.3390/universe11120398

Bhowmick R, Nath SK, Debnath D, Chang H-K. Jet X-Ray Properties of EXO 1846-031 During Its 2019 Outburst. Universe. 2025; 11(12):398. https://doi.org/10.3390/universe11120398

Chicago/Turabian StyleBhowmick, Riya, Sujoy Kumar Nath, Dipak Debnath, and Hsiang-Kuang Chang. 2025. "Jet X-Ray Properties of EXO 1846-031 During Its 2019 Outburst" Universe 11, no. 12: 398. https://doi.org/10.3390/universe11120398

APA StyleBhowmick, R., Nath, S. K., Debnath, D., & Chang, H.-K. (2025). Jet X-Ray Properties of EXO 1846-031 During Its 2019 Outburst. Universe, 11(12), 398. https://doi.org/10.3390/universe11120398