Benchtop NMR in Biomedicine: An Updated Literature Overview

Abstract

1. Introduction

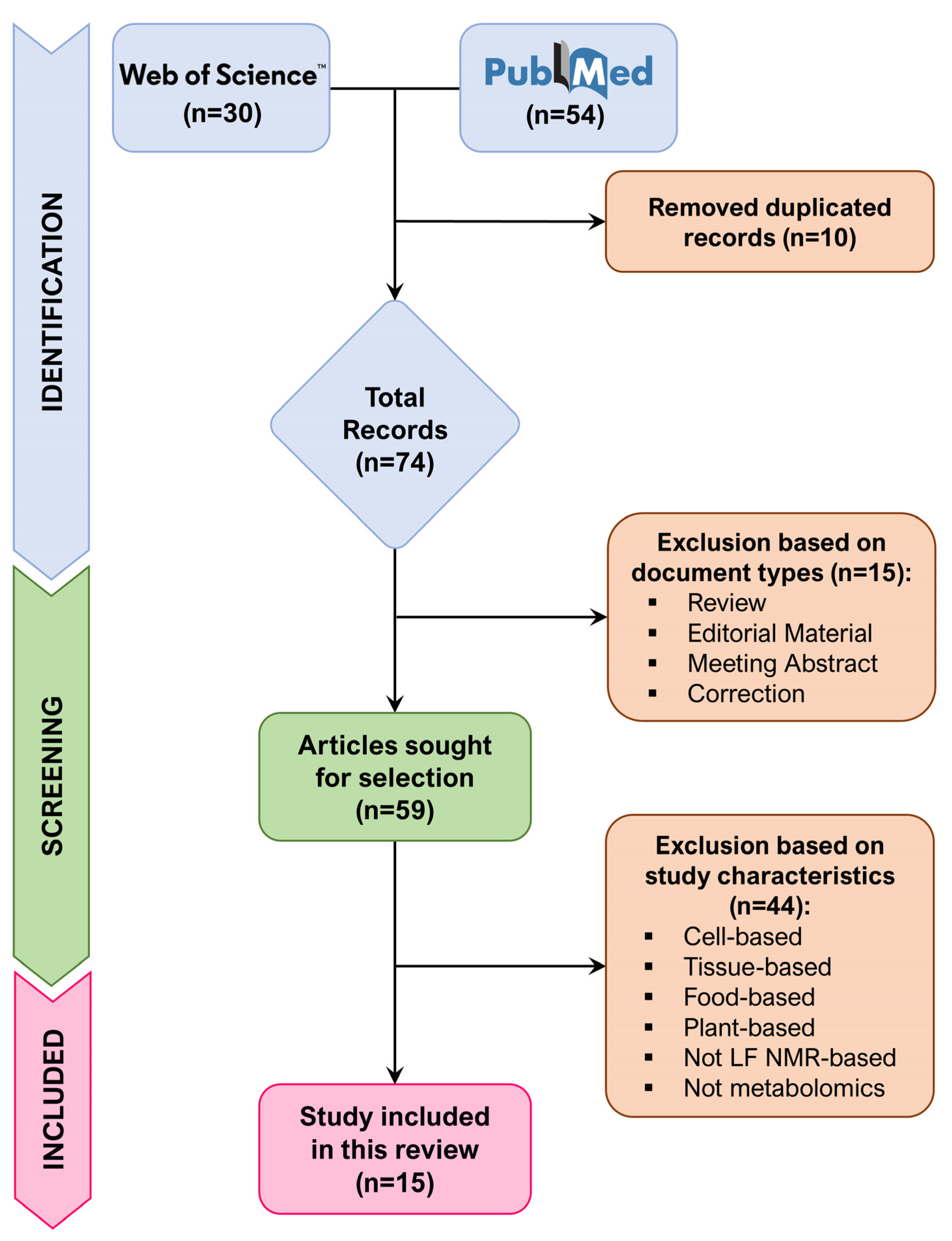

2. Methods

- ▪

- Studies that performed metabolomics via low-field NMR on human and animal biofluids.

- ▪

- Studies oriented to clinical applications of low-field NMR.

- ▪

- Scientific articles included in the Web of Science electronic database and/or in the PubMed database.

- ▪

- Not full-length articles, such as case reports, conference proceedings, letters to editor, reviews, and meta-analysis.

- ▪

- Metabolomics performed only using analytical platforms other than low-field NMR (e.g., mass spectrometry and high-field NMR).

- ▪

- Studies analyzing cell models, tissues, or plant- and food-derived samples.

- ▪

- Studies published after 1 September 2025.

3. Results

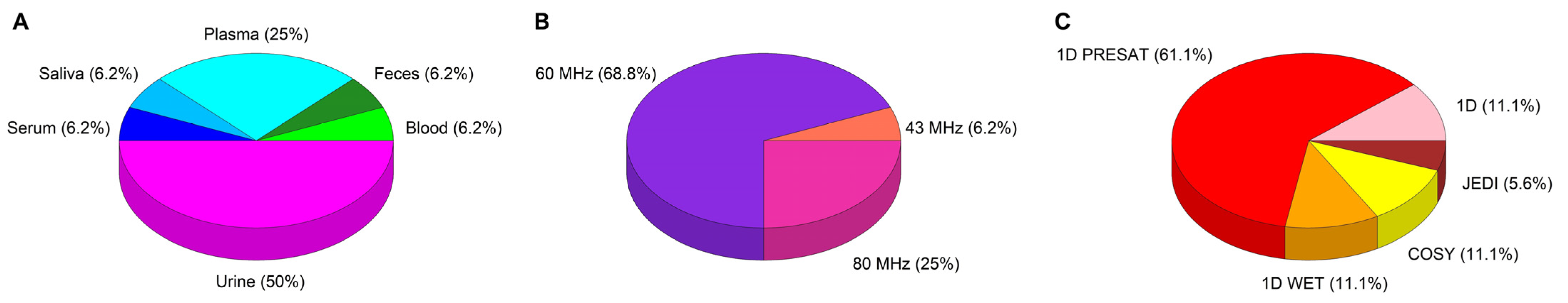

3.1. Sample Preparation, NMR Acquisition, and Data Analysis Procedures

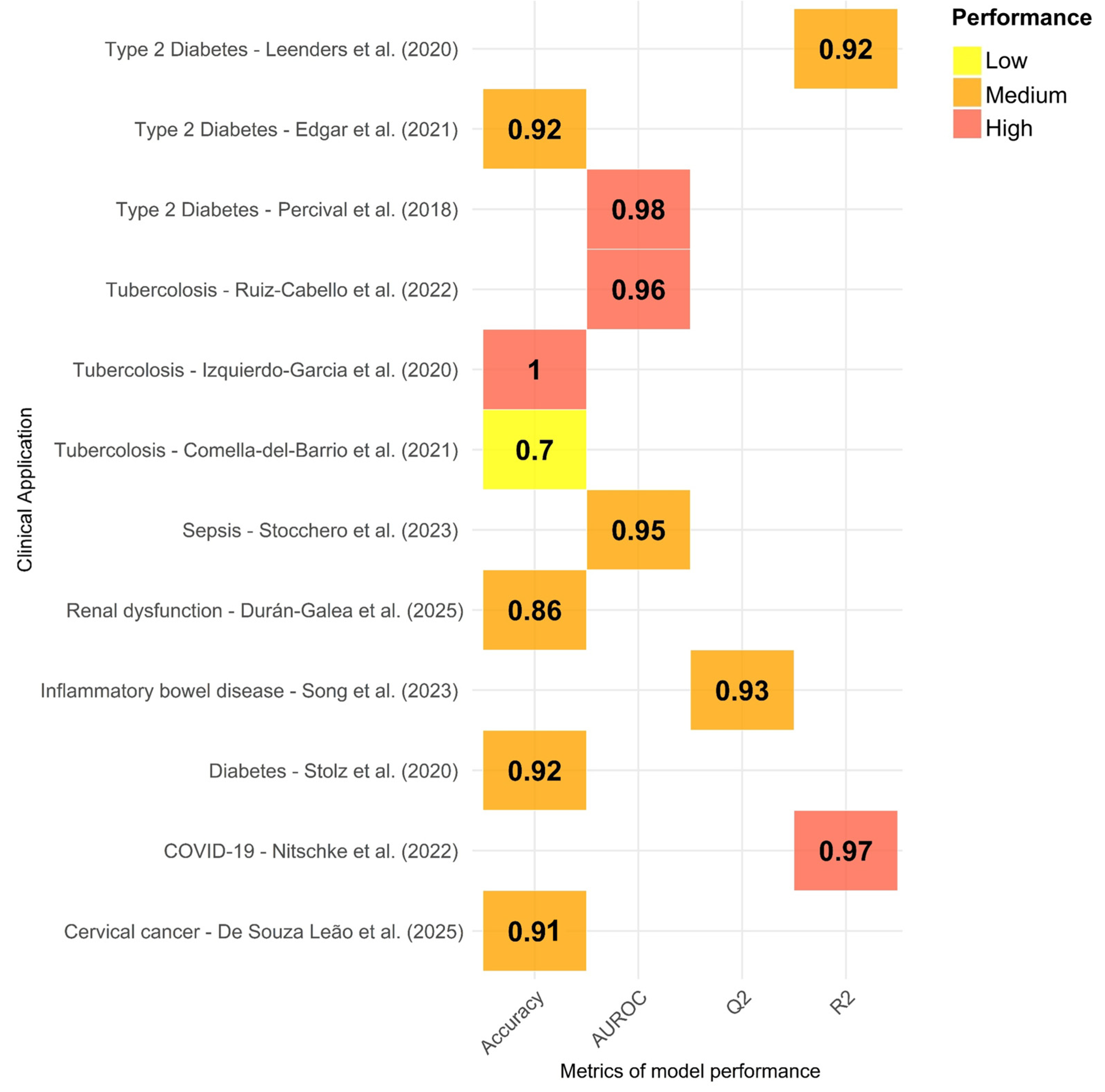

3.2. Results Described in the Reviewed Studies

3.2.1. Human Urine

3.2.2. Human Saliva

3.2.3. Human Whole Blood

3.2.4. Human Serum and Plasma

3.2.5. Bovine Plasma

3.2.6. Mice Feces

3.2.7. Animal Urine

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NMR | Nuclear Magnetic Resonance |

| 1D | One-Dimensional |

| 2D | Two-Dimensional |

| ANPC | Australian National Phenome Center |

| Apo-A1 | Apolipoprotein A1 |

| Apo-B100 | Apolipoprotein B100 |

| AUROC | Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve |

| CC | Cervical Cancer |

| CDEC | Carbon Decoupling |

| CIC bioGUNE | Center for Cooperative Research in Biosciences |

| CKD | Chronic Kidney Disease |

| Cn | Urinary Creatinine |

| COSY | Correlated Spectroscopy |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus Disease of 2019 |

| CTR | Control |

| DSS | Dextran Sodium Sulfate |

| EOS | Early Onset Sepsis |

| HDL-C | High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol |

| HF | High Field |

| HMDB | Human Metabolome Database |

| IBD | Inflammatory Bowel Diseases |

| IRIS | International Renal Interest Society |

| JEDI | J-edited diffusion and relaxation |

| LDL-C | Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol |

| LF | Low Field |

| LTBI | Latent Tuberculosis Infection |

| MS | Mass Spectrometry |

| NA | Not Available |

| NOE | Nuclear Overhauser Effect |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| PLS-DA | Partial Least Squares–Discriminant Analysis |

| PnP | Pneumococcal Pneumonia |

| PRESAT | Presaturation |

| PTB | Paratuberculosis |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 |

| SPC | Supramolecular Phospholipid Composite |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| T2D | Type 2 Diabetes |

| TB | Tuberculosis |

| TMSP | 3-(Trimethylsilyl) propionic-2,2,3,3-d4 acid |

| VLDL | Very Low-Density Lipoprotein |

| WET | Water Suppression Enhanced Through T1 Effects |

References

- Wishart, D.S.; Tzur, D.; Knox, C.; Eisner, R.; Guo, A.C.; Young, N.; Cheng, D.; Jewell, K.; Arndt, D.; Sawhney, S.; et al. HMDB: The Human Metabolome Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, D521–D526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leenders, J.; Grootveld, M.; Percival, B.; Gibson, M.; Casanova, F.; Wilson, P.B. Benchtop Low-Frequency 60 MHz NMR Analysis of Urine: A Comparative Metabolomics Investigation. Metabolites 2020, 10, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buergel, T.; Steinfeldt, J.; Ruyoga, G.; Pietzner, M.; Bizzarri, D.; Vojinovic, D.; Upmeier zu Belzen, J.; Loock, L.; Kittner, P.; Christmann, L.; et al. Metabolomic Profiles Predict Individual Multidisease Outcomes. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 2309–2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, M.V.; Millwood, I.Y.; Kartsonaki, C.; Hill, M.R.; Bennett, D.A.; Boxall, R.; Guo, Y.; Xu, X.; Bian, Z.; Hu, R.; et al. Lipids, Lipoproteins, and Metabolites and Risk of Myocardial Infarction and Stroke. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 71, 620–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Donato, S.; Vignoli, A.; Biagioni, C.; Malorni, L.; Mori, E.; Tenori, L.; Calamai, V.; Parnofiello, A.; Di Pierro, G.; Migliaccio, I.; et al. A Serum Metabolomics Classifier Derived from Elderly Patients with Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Predicts Relapse in the Adjuvant Setting. Cancers 2021, 13, 2762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jobard, E.; Dossus, L.; Baglietto, L.; Fornili, M.; Lécuyer, L.; Mancini, F.R.; Gunter, M.J.; Trédan, O.; Boutron-Ruault, M.-C.; Elena-Herrmann, B.; et al. Investigation of Circulating Metabolites Associated with Breast Cancer Risk by Untargeted Metabolomics: A Case–Control Study Nested within the French E3N Cohort. Br. J. Cancer 2021, 124, 1734–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCartney, A.; Vignoli, A.; Tenori, L.; Fornier, M.; Rossi, L.; Risi, E.; Luchinat, C.; Biganzoli, L.; Di Leo, A. Metabolomic Analysis of Serum May Refine 21-Gene Expression Assay Risk Recurrence Stratification. NPJ Breast Cancer 2019, 5, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wishart, D.S. Emerging Applications of Metabolomics in Drug Discovery and Precision Medicine. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2016, 15, 473–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vignoli, A.; Meoni, G.; Ghini, V.; Di Cesare, F.; Tenori, L.; Luchinat, C.; Turano, P. NMR-Based Metabolomics to Evaluate Individual Response to Treatments. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2022, 277, 209–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikoff, W.R.; Anfora, A.T.; Liu, J.; Schultz, P.G.; Lesley, S.A.; Peters, E.C.; Siuzdak, G. Metabolomics Analysis Reveals Large Effects of Gut Microflora on Mammalian Blood Metabolites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 3698–3703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joice, R.; Yasuda, K.; Shafquat, A.; Morgan, X.C.; Huttenhower, C. Determining Microbial Products and Identifying Molecular Targets in the Human Microbiome. Cell Metab. 2014, 20, 731–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Raftery, D. Comparing and Combining NMR Spectroscopy and Mass Spectrometry in Metabolomics. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2007, 387, 525–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindon, J.C.; Nicholson, J.K. Spectroscopic and Statistical Techniques for Information Recovery in Metabonomics and Metabolomics. Annu. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2008, 1, 45–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markley, J.L.; Brüschweiler, R.; Edison, A.S.; Eghbalnia, H.R.; Powers, R.; Raftery, D.; Wishart, D.S. The Future of NMR-Based Metabolomics. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2017, 43, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignoli, A.; Tenori, L. NMR-Based Metabolomics in Alzheimer’s Disease Research: A Review. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2023, 10, 1308500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignoli, A.; Ghini, V.; Meoni, G.; Licari, C.; Takis, P.G.; Tenori, L.; Turano, P.; Luchinat, C. High-Throughput Metabolomics by 1D NMR. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2019, 58, 968–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emwas, A.-H.; Roy, R.; McKay, R.T.; Tenori, L.; Saccenti, E.; Gowda, G.A.N.; Raftery, D.; Alahmari, F.; Jaremko, L.; Jaremko, M.; et al. NMR Spectroscopy for Metabolomics Research. Metabolites 2019, 9, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giberson, J.; Scicluna, J.; Legge, N.; Longstaffe, J. Chapter Three—Developments in Benchtop NMR Spectroscopy 2015–2020. In Annual Reports on NMR Spectroscopy; Webb, G.A., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2021; Volume 102, pp. 153–246. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percival, B.C.; Grootveld, M.; Gibson, M.; Osman, Y.; Molinari, M.; Jafari, F.; Sahota, T.; Martin, M.; Casanova, F.; Mather, M.L.; et al. Low-Field, Benchtop NMR Spectroscopy as a Potential Tool for Point-of-Care Diagnostics of Metabolic Conditions: Validation, Protocols and Computational Models. High-Throughput 2018, 8, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izquierdo-Garcia, J.L.; Comella-del-Barrio, P.; Campos-Olivas, R.; Villar-Hernández, R.; Prat-Aymerich, C.; De Souza-Galvão, M.L.; Jiménez-Fuentes, M.A.; Ruiz-Manzano, J.; Stojanovic, Z.; González, A.; et al. Discovery and Validation of an NMR-Based Metabolomic Profile in Urine as TB Biomarker. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 22317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edgar, M.; Percival, B.C.; Gibson, M.; Jafari, F.; Grootveld, M. Low-Field Benchtop NMR Spectroscopy as a Potential Non-Stationary Tool for Point-of-Care Urinary Metabolite Tracking in Diabetic Conditions. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2021, 171, 108554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stocchero, M.; Cannet, C.; Napoli, C.; Demetrio, E.; Baraldi, E.; Giordano, G. Low-Field Benchtop NMR to Discover Early-Onset Sepsis: A Proof of Concept. Metabolites 2023, 13, 1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, M.; Kuhn, S.; Page, G.; Grootveld, M. Computational Simulation of 1H NMR Profiles of Complex Biofluid Analyte Mixtures at Differential Operating Frequencies: Applications to Low-field Benchtop Spectra. Magn. Reson. Chem. 2022, 60, 1097–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolz, M.; Schlawne, C.; Hoffmann, J.; Hartmann, V.; Marini, I.; Fritsche, A.; Peter, A.; Bakchoul, T.; Schick, F. Feasibility of Precise and Reliable Glucose Quantification in Human Whole Blood Samples by 1 Tesla Benchtop NMR. NMR Biomed. 2020, 33, e4358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitschke, P.; Lodge, S.; Hall, D.; Schaefer, H.; Spraul, M.; Embade, N.; Millet, O.; Holmes, E.; Wist, J.; Nicholson, J.K. Direct Low Field J-Edited Diffusional Proton NMR Spectroscopic Measurement of COVID-19 Inflammatory Biomarkers in Human Serum. Analyst 2022, 147, 4213–4221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wist, J.; Nitschke, P.; Conde, R.; De Diego, A.; Bizkarguenaga, M.; Lodge, S.; Hall, D.; Chai, Z.; Wang, W.; Kowlessur, S.; et al. Benchtop Proton NMR Spectroscopy for High-Throughput Lipoprotein Quantification in Human Serum and Plasma. Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 6399–6409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza Leão, L.Q.; de Andrade, J.C.; Marques, G.M.; Guimarães, C.C.; de Albuquerque, R.d.F.V.; e Silva, A.S.; de Araujo, K.P.; de Oliveira, M.P.; Gonçalves, A.F.; Figueiredo, H.F.; et al. Rapid Prediction of Cervical Cancer and High-Grade Precursor Lesions: An Integrated Approach Using Low-Field 1H NMR and Chemometric Analysis. Clin. Chim. Acta 2025, 574, 120346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Cabello, J.; Sevilla, I.A.; Olaizola, E.; Bezos, J.; Miguel-Coello, A.B.; Muñoz-Mendoza, M.; Beraza, M.; Garrido, J.M.; Izquierdo-García, J.L. Benchtop Nuclear Magnetic Resonance-based Metabolomic Approach for the Diagnosis of Bovine Tuberculosis. Transbounding Emerg. Dis. 2022, 69, e859–e870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Z.; Ohnishi, Y.; Osada, S.; Gan, L.; Jiang, J.; Hu, Z.; Kumeta, H.; Kumaki, Y.; Yokoi, Y.; Nakamura, K.; et al. Application of Benchtop NMR for Metabolomics Study Using Feces of Mice with DSS-Induced Colitis. Metabolites 2023, 13, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finch, N.; Percival, B.; Hunter, E.; Blagg, R.J.; Blackwell, E.; Sagar, J.; Ahmad, Z.; Chang, M.-W.; Hunt, J.A.; Mather, M.L.; et al. Preliminary Demonstration of Benchtop NMR Metabolic Profiling of Feline Urine: Chronic Kidney Disease as a Case Study. BMC Res. Notes 2021, 14, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durán-Galea, Á.; Ramiro-Alcobendas, J.-L.; Duque-Carrasco, F.; Nicolás-Barceló, P.; Cristóbal-Verdejo, J.-I.; Ruíz-Tapia, P.; Barrera-Chacón, R.; Marcos, C.F. A Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy Metabolomic Approach to Renal Dysfunction in Canine Leishmaniasis. Vet. Anim. Sci. 2025, 28, 100440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comella-del-Barrio, P.; Izquierdo-Garcia, J.L.; Gautier, J.; Doresca, M.J.C.; Campos-Olivas, R.; Santiveri, C.M.; Muriel-Moreno, B.; Prat-Aymerich, C.; Abellana, R.; Pérez-Porcuna, T.M.; et al. Urine NMR-Based TB Metabolic Fingerprinting for the Diagnosis of TB in Children. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 12006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso-Moreno, P.; Rodriguez, I.; Izquierdo-Garcia, J.L. Benchtop NMR-Based Metabolomics: First Steps for Biomedical Application. Metabolites 2023, 13, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author/Year | Cohort Allocation | Cases/Controls | Age Mean (yrs) | Sex | Disease or Condition | Aim of the Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percival et al. (2018) [20] | United Kingdom | T2D (n = 10) and CTR (n = 14). | T2D: 45 CTR: 27 | T2D: females (n = 7), males (n = 1), NA (n = 2). CTR: females (n = 9), males (n = 5). | Type 2 diabetes | To present an updated protocol for the analysis of biofluids through compact, benchtop NMR measurements. |

| Izquierdo-Garcia et al. (2020) [21] | Spain, Germany | Active TB patients (n = 189), pneumococcal pneumonia patients (n = 42), LTBI individuals (n = 61), and uninfected individuals (n = 40). TB patients vs. CTR groups (pneumococcal pneumonia, LTBI, and uninfected). TB, tuberculosis; PnP, pneumococcal pneumonia; LTBI, latent TB infection; Uninfected, individuals without infection. | Entire population: 45.9 | males (n = 215), females (n = 117). | Tuberculosis | To identify and characterize a metabolic profile of TB in urine by high-field NMR spectrometry and assess whether the tuberculosis (TB) metabolic profile is also detected by a low-field benchtop NMR spectrometer. |

| Leenders et al. (2020) [2] | United Kingdom | T2D patients (n = 10) and CTR (n = 15). | NA | NA | Type 2 diabetes | Comparing the accuracies and precision of statistical tools via the acquisition of urinary spectra at both high and low operating frequencies. |

| Edgar et al. (2021) [22] | United Kingdom | T2D (n = 10) and CTR (n = 14). | T2D: 45 CTR: 27 | T2D cohort: females (n = 7), males (n = 3). CTR cohort: females (n = 9), males (n = 5). | Type 2 diabetes | To diagnose rapidly and potential prognostic monitor of T2D in human urine samples. |

| Comella-del-Barrio et al. (2021) [21] | Haiti | Presumptive TB (n = 62) and CTR (n = 55). | Presumptive TB: 7.28 CTR: 6.45 | Presumptive TB: females (n = 25), males (n = 37). CTR: females (n = 24), males (n = 31). | Tuberculosis | To describe a urine 1H NMR-based metabolic fingerprint for the diagnosis of TB in children. |

| Stocchero et al. (2023) [23] | Italy | EOS group (n = 15) and CTR (n = 15). | EOS group: 207 days CTR: 213 days | EOS group: males (n = 7). CTR: males (n = 5). | Sepsis | Urinary metabolic fingerprint generated using a benchtop NMR instrument for the early detection of sepsis in preterm newborns. |

| Edgar et al. (2022) [24] | United Kingdom | Healthy human participants (n = 12) (of whom six were non-smokers and six were regular ‘mild-to-heavy’ smokers of tobacco cigarettes). | Age range: 21–65 | Males (n = 5), females (n = 7). | Methodological | To demonstrate the valuable applications of software options available for the prediction of chemical shift values, coupling patterns, and coupling constants in the 1H NMR profiles of analyte molecules. |

| Stolz et al. (2020) [25] | Germany | Healthy blood donors and diabetic patients. (tot. n = 122). | NA | NA | Diabetes | To explore the capabilities of low-field NMR for measuring glucose concentrations in whole blood. |

| Nitschke et al. (2022) [26] | Spain | SARS-CoV-2-positive patients (n = 29) CTR (n = 28) | NA | NA | COVID-19 | To propose adapted versions of JEDI experiments that could provide comparable diagnostic capabilities. |

| Wist et al. (2025) [27] | Australia, Mauritius, Spain, Unites States of America, Germany | Healthy/free-living population cohort (N3 = 127) from Bruker Biospin GmbH & Co. KG, Germany, a free-living population cohort (N2 = 127) from CIC bioGUNE, and a diabetic/obese cohort (N1 = 119) from the ANPC Australia which was collected in the Republic of Mauritius. | ANPC Cohort: 52 BioGUNE Cohort: 45 Bruker Cohort: 52 | ANPC cohort: males (n = 63); BioGUNE cohort: males (n = 92); Bruker cohort: males (n = 92). | Methodological | To translate NMR lipoprotein analysis from high- to low-field systems. |

| De Souza Leão et al. (2025) [28] | Brazil | CTR (n = 40); pre-cancer patients (n = 40); and patients with CC (n = 25). | CTR: 38.92 Pre-cancer patients: 40.32 CC patients: 43.56 | Only women | Cervical cancer | To evaluate the efficiency of benchtop 1H NMR spectral data, combined with chemometric analyses in predicting CC and its high-grade precursor lesions. |

| Ruiz-Cabello et al. (2022) [29] | Spain | TB (derivation set, n = 11), diagnosed with PTB (n = 10), PTB-vaccinated healthy control (n = 10), and healthy PTB-unvaccinated control (n = 10). | NA | NA | Bovine tuberculosis | Plasma fingerprinting using LF-NMR to differentiate TB subjects from uninfected animals, and paratuberculosis-vaccinated subjects. |

| Song et al. (2023) [30] | Japan | Six C57BL/6JJcl mice were randomly divided into two groups: the control group and the DSS-induced group (n = 3 per group). | 11 weeks | All males (n = 6). | Inflammatory bowel disease | To characterize the alterations in the metabolic profile of fecal extracts obtained from dextran sodium sulfate-induced ulcerative colitis model mice and compared them with the data acquired from high-field NMR (800 MHz). |

| Finch et al. (2021) [31] | United Kingdom | CTR (n = 2) and CKD (n = 2) IRIS stage 2 cases. | NA | Males (n = 2), females (n = 2). | Chronic kidney disease | Benchtop metabolic profiling technology based on NMR to discriminate between chronic kidney disease case and control samples in a pilot feline cohort. |

| Durán-Galea et al. (2025) [32] | Spain | CTR dogs (n = 14), dogs with CKD due to leishmaniasis (n = 33), and dogs with CKD without leishmaniasis (n = 8). | Entire population: 4.98 | Males (n = 9), females (n = 5). | Chronic kidney disease | To identify distinct patterns in the NMR spectra of urine samples from dogs with chronic kidney disease in canine leishmaniasis, reflecting the underlying metabolic profiles. |

| Author/Year | Biofluids | Sample Storage | Sample Preparation | Benchtop NMR | NMR Experiments | Significant Metabolites § |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percival et al. (2018) [20] | Human urine | −80 °C |

| Magritek Spinsolve 60 Ultra spectrometer (60 MHz) | 1D 1H with PRESAT: 64 scans, acquisition time 6.4 s, repetition time 10 s, pulse angle 90°, relaxation delay 1 s. | ↑ Citrate, ↑ creatinine, ↑ acetate, ↑ acetone, ↑ 3-D-hydroxybutyrate, ↑ glucose, ↓ indoxyl sulphate, ↓ hippurate, N-acetyl storage compounds, lactate. Key discriminatory biomarkers identified by multivariate analysis in order of effectiveness: citrate, 3-D- hydroxybutyrate, hippurate, N-acetyl storage compounds, alanine, total bulk glucose, lactate, α-glucose, 3-(3-hydroxyphenyl)-3-hydroxypropanoate, indoxyl sulphate, urea in that order of effectiveness. |

| Izquierdo-Garcia et al. (2020) [21] | Human urine | −20 °C |

| Magritek Spinsolve 60 Ultra spectrometer (60 MHz) | 1D 1H with PRESAT: 64 scans, acquisition time 6.4 s, repetition time 10 s, pulse angle 90°, relaxation delay 1 s. | ↑ Aminoadipic acid, ↑ creatine, ↑ mannitol, ↑ phenylalanine, ↓ hippurate ↓ citrate, ↓ creatinine, ↓ glucose. |

| Leenders et al. (2020) [2] | Human urine | −80 °C |

| Magritek Spinsolve 60 Ultra spectrometer (60 MHz) | 1D 1H with PRESAT: 64 scans, acquisition time 6.4 s, repetition time 10 s, pulse angle 90°, relaxation delay 1 s. 2D COSY: 8192 datapoints in F2, 256 points in F1, sweep widths of14 and 46 ppm, respectively; 8 scans for F2, acquisition time 0.16 s (F1) and 1.63 s (F2). | T2D patients presenting higher levels of glucose: ↑ glucose, ↓ citrate, ↓ creatinine, ↓ indoxyl sulfate, ↓ urea, ↓ hippurate. T2D patients presenting lower levels of glucose: ↓ glucose, ↑ citrate, ↑ lactate, ↑ indoxyl sulfate, ↑ hippurate. |

| Edgar et al. (2021) [22] | Human urine | −80 °C |

| Magritek Spinsolve 60 spectrometer (60 MHz) | 1D 1H with PRESAT: 64 or 128 scans, acquisition time 6.4 s, repetition time 10 s, and pulse angle 90°. | ↑ Citrate, ↑ N-acetylated metabolites, ↑ creatine/creatinine, ↓ lactate, ↓ hippurate, ↓ indoxyl sulfate, ↓ 3-(3-hydroxyphenyl)-3-hydroxypropanoate. |

| Comella-del-Barrio et al. (2021) [21] | Human urine | −20 °C |

| Magritek Spinsolve 60 Ultra spectrometer (60 MHz) | 1D 1H with PRESAT, 64 scans, acquisition time 6.4 s. | NA |

| Stocchero et al. (2023) [23] | Human urine | −80 °C |

| Bruker Fourier 80 spectrometer (80 MHz) | Noesypr1d 1H with PRESAT: recovery delay 4 s, acquisition time 5 s, 64 scans, 25 °C. | ↑ 2,3,4-trihydroxybutyric acid, ↑ 3,4-dihydroxybutanoic acid, ↑ d-glucose, ↑ d-serine,↑ hippuric acid, ↑ lactate, ↑ L-threonine, ↑ N-glycine, ↑ pseudo uridine, ↑ ribitol, ↑ kynurenic acid, ↑ myo-inositol, ↑ taurine, ↑ phenylalanine, ↑ gluconate. |

| Edgar et al. (2022) [24] | Human saliva | −80 °C |

| Magritek Spinsolve 60 Ultra spectrometer (60 MHz) | 1D 1H with PRESAT: 64/384 scans, acquisition time 6.4 s, repetition time 10/15 s, pulse angle 90°, total experiment time around 15 min. | Acetate, formate, methanol, propionate, and glycine. |

| Stolz et al. (2020) [25] | Human whole blood | NA |

| Magritek Spinsolve Carbon spectrometer (43 MHz) and Magritek Spinsolve Carbon Ultra spectrometer (60 MHz) | 1D 1H: repetition time 4.5 s, pulse angle 90°, dwell time 500 μ, 8192 points, 128 averages, and total experiment duration roughly 10 min). | Glucose |

| Nitschke et al. (2022) [26] | Human plasma | −80 °C |

| Bruker Fourier 80 spectrometer (80 MHz) | 1D 1H zg: 1 scan, 16,384 data points, relaxation delay 300.0 s, spectral width 40 ppm, and total experiment time 5 min 2 s. Noesygppr1d with PRESAT: 32 scans, 17646 data points, relaxation delay 4 s, spectral width 40 ppm, tot experiment time 4 min 4 s. JEDI: 256 scans, 3224 data points, relaxation delay 2.5 s, spectral width 20 ppm, tot experiment time 15 min. | ↑ Glyc, ↓ SPC |

| Wist et al. (2025) [27] | Human serum and plasma | NA |

| Bruker Fourier 80 spectrometer (80 MHz) | 1D experiment with PRESAT (noesypr1d): 96 scans (+4 dummy scans), 23,808 data points, relaxation delay of 4.0 s, mixing time of 50 ms, presaturation of 15 Hz and a spectral width of 30 ppm. For the lipoprotein main fractions, a standard 1D experiment with solvent suppression was acquired with 512 scans and a relaxation delay of 2.0 s. All other parameters were equal to 1D experiments of the serum samples. | A total of 25 out of 28 major lipoprotein-related parameters were successfully predicted with a benchtop NMR spectrometer, including the main parameters that are commonly used (LDL-C, HDL-C, total cholesterol, Apo-A1, Apo-B100, and Apo-B100/Apo-A1) as cardiometabolic risk markers. |

| De Souza Leão et al. (2025) [28] | Human plasma | −80 °C |

| Magritek Spinsolve MultiX spectrometer (60 MHz) | 1H NMR spectra were acquired in the “1D PROTON CDEC” mode using a 90° radiofrequency pulse with: 64 scans, an acquisition time of 3.2 s per scan and a repetition time of 15 s. Both 13C decoupling and Nuclear Overhauser Effect (NOE) enhancement were enabled. | ↑ Lipids (LDL and VLDL), ↑ lactate, ↑ N-acetylated glycoproteins, ↑ citrate, ↑ choline, ↑ glycine, ↑ α-glucose, ↑ uridine. |

| Ruiz-Cabello et al. (2022) [29] | Bovine plasma | NA |

| Magritek Spinsolve 60 Ultra spectrometer (60 MHz) | 1D 1H with PRESAT: 64 scans, acquisition time 6.4 s, repetition time 10 s, pulse angle 90°, and relaxation delay 1 s. | ↓ 3-Hydroxybutyrate, ↓ alanine, ↓ creatine, ↓ formate,↓ glutamine, ↓ isobutyrate, ↓ isoleucine, ↓ leucine, ↓ O-phosphocholine, ↓ phenylalanine, ↓ tyrosine, ↓ valine, ↓ τ-Methylhistidine, ↑ glucose. |

| Song et al. (2023) [30] | Mice feces | fecal samples −80 °C, lyophilized and pulverized samples −30 °C |

| Magritek Spinsolve 60 Ultra spectrometer (60 MHz) | 1D 1H with PRESAT: 128 scans, sweep width of 81 ppm, time-domain size of 32,768, acquisition time of 3.2 s, and a repetition time of 7 s (acquisition + relaxation) 299.65 K. | ↓ Butyrate, ↓ propionate, ↓ isoleucine, ↓ valine, ↓ leucine, ↓ alanine, ↓ aspartate, ↓ glycerol, ↓ threonine, ↑ acetate, ↑ succinate, ↑ glucose. |

| Finch et al. (2021) [31] | Feline urine | −80 °C |

| Oxford Instruments X-Pulse spectrometer (60 MHz) | Acquisition temperature 40 °C. 1D 1H with WET: 64/128 scans, 6 s acquisition time, 5 s relaxation delay. 2D COSY: 8 scans of 256 slices. | ↓ Acetate, ↓ glycine, ↓ serine, ↓ threonine, ↓ citrate, ↓ taurine, ↑ hippuric acid, ↑ creatinine, ↑ phenylacetylglycine |

| Durán-Galea et al. (2025) [32] | Canine urine | −80 °C |

| Magritek Spinsolve 80 Ultra spectrometer (80 MHz) | 1D 1H NMR with a WET. Data acquisition parameters included a spectral width of 2500 Hz, 65,536 data points and 128 scans. | NA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Fantato, L.; Salobehaj, M.; Patrussi, J.; Meoni, G.; Vignoli, A.; Tenori, L. Benchtop NMR in Biomedicine: An Updated Literature Overview. Metabolites 2026, 16, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010003

Fantato L, Salobehaj M, Patrussi J, Meoni G, Vignoli A, Tenori L. Benchtop NMR in Biomedicine: An Updated Literature Overview. Metabolites. 2026; 16(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleFantato, Linda, Maria Salobehaj, Jacopo Patrussi, Gaia Meoni, Alessia Vignoli, and Leonardo Tenori. 2026. "Benchtop NMR in Biomedicine: An Updated Literature Overview" Metabolites 16, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010003

APA StyleFantato, L., Salobehaj, M., Patrussi, J., Meoni, G., Vignoli, A., & Tenori, L. (2026). Benchtop NMR in Biomedicine: An Updated Literature Overview. Metabolites, 16(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo16010003