Abstract

Healthcare collaborative processes still encounter major challenges, particularly regarding the interoperability of heterogeneous information systems, the traceability of medical interventions, and the secure sharing of patient data under strict privacy regulations such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). This paper presents a patient-centric, blockchain-based framework designed to overcome these limitations. The proposed solution integrates smart contracts and non-fungible tokens (NFTs) within the Ethereum blockchain to ensure data integrity, traceability, and privacy preservation. Furthermore, a compliance-by-design mechanism is embedded into the smart contracts to enable self-supervision of collaborative workflows without third-party intervention. A Proof-of-Authority (PoA) consensus protocol is also adopted to optimize validation efficiency and significantly reduce computational and energy costs.

Keywords:

blockchain; smart contract; compliance by design; NFT; privacy-preserving; traceability; PoA 1. Introduction

Complex pathological cases requiring close collaboration among multiple healthcare stakeholders face numerous persistent challenges. At the professional level, physicians and specialists often operate within heterogeneous and incompatible Health Information Systems (HIS), which hinders seamless coordination when managing the same pathological case in real time. This fragmentation leads to difficulties in ensuring the traceability of medical interventions, maintaining the continuity of care, and securely sharing sensitive patient data while preserving privacy. These challenges are further aggravated by the absence of effective mechanisms that simultaneously ensure the traceability and transparency of medical activities, while safeguarding the security and confidentiality of patient data.

This article explores an innovative blockchain solution relying on a set of recent, robust, and flexible technologies to effectively address these challenges. On one hand, the adoption of a PoA consensus mechanism on the Ethereum blockchain is particularly well suited for healthcare environments, where the validating entities (hospitals, ministries, health agencies, etc.) are already recognized, regulated, and authenticated. This mechanism thus allows for guaranteeing a high level of trust while significantly reducing operational costs and latency.

On the other hand, the integration of smart contracts constitutes the foundation of our approach by enabling the explicit encapsulation of compliance rules (compliance by design) and the secure, supervised automation of healthcare workflows. These workflows will be reinforced by a tokenization mechanism based on NFTs, coupled with off-chain decentralized storage via the Interplanetary File System (IPFS). This combination simultaneously resolves issues related to massive on-chain storage, patient data privacy, and alignment with the strict regulatory requirements imposed by GDPR and HIPAA.

So, the proposed framework provides a solid foundation for the deployment of secure, traceable, and interoperable Decentralized Applications (DApps), enabling the integration of a collaborative and self-supervised workflow among distributed healthcare systems, while eliminating the need for trusted third parties. Consequently, the main objectives of this work are threefold:

- Confidentiality and consent management: To design a blockchain-based framework that guarantees patient data confidentiality and consent control through a tokenization mechanism.

- Traceability and self-supervision: To ensure the traceability of medical interventions by embedding compliance rules directly into smart contracts, enabling automated supervision of collaborative workflows.

- Scalability and interoperability: To propose a scalable architecture that integrates seamlessly with existing healthcare information systems while ensuring interoperability.

This paper is organized as follows:

After this introduction, Section 2 presents the related works and provides a benchmarking analysis of existing blockchain-based healthcare solutions within the same context. Section 3 details the materials and methods, describing the key modeling concepts and architectural design of the proposed framework. Section 4 outlines the deployment and experimentation phases, demonstrating the implementation of the system prototype through a real-world use case and evaluating its non-functional aspects. Section 5 reports the results, focusing on the performance analysis and key findings. Next, Section 6 analyzes and discusses the overall contributions. Finally, Section 7 draws conclusions, and outlines directions for future research.

2. Related Works

In the medical domain, the pursuit of high-quality care within heterogeneous hardware and software infrastructures has motivated numerous research efforts toward achieving interoperability and integration among distributed healthcare systems. Several recent studies [,,] have proposed frameworks enabling seamless communication between such infrastructures. However, within legal and regulatory contexts, these solutions still fall short in ensuring traceability and auditable accountability of medical interventions in collaborative environments. This limitation has consequently redirected research attention toward blockchain technology as a promising enabler of secure, transparent, and verifiable data management.

Originally introduced by Nakamoto as the core component of Bitcoin [] to solve the double-spending problem in digital currency systems, blockchain has since evolved far beyond its financial origins. It is now recognized as a versatile technology serving as a secure data repository, a computational framework, a communication protocol, an asset management tool, and a decentralized control mechanism. With the continuous advancement of the technology, various blockchain platforms have emerged, each designed with distinct objectives. Among the most prominent are Ethereum [] and Hyperledger Fabric []. Initially, traceability and auditability emerged as essential aspects beyond interoperability. Hence, in recent years the blockchain-based solution has gained attention due to its immutability and decentralized trust model. MedRec [] was among the first initiatives to leverage blockchain for Electronic Health Record (EHR) management, focusing on auditability and patient-centric control. Subsequently, FHIRChain [] extended this effort by incorporating the HL7 FHIR standard [] to enhance interoperability between healthcare systems. Similarly, the framework proposed in [] implemented blockchain to ensure secure and scalable storage of electronic medical records.

While blockchain provides immutable and transparent data storage, it still faces limitations concerning data privacy and regulatory compliance, especially under frameworks such as GDPR []. The immutability of blockchain makes it difficult to delete or modify sensitive records, potentially compromising patient privacy []. To overcome these challenges, Blockchain 2.0 [] was introduced, incorporating advanced smart contract capabilities and enhanced adaptability across diverse application domains. Meanwhile, several studies have investigated privacy-preserving mechanisms. The authors in [] emphasized the need to classify healthcare blockchain architectures and select appropriate secure and private models before large-scale deployment. For instance, approaches based on Zero-Knowledge Proofs (ZKPs) have gained popularity as they allow validation of data without revealing sensitive information. A blockchain-based privacy-preserving scheme in [] was proposed to ensuring data availability and consistency between patients and research institutions. In this scheme, ZKPs are used to verify whether a patient’s medical data satisfies research criteria without exposing the data itself. Likewise, the authors in [] proposed a Hyperledger Fabric-based access control system granting patients full authority over their data.

On the other hand, healthcare transactions generate large datasets, leading to high on-chain storage costs, performance bottlenecks, and increased latency. So, scalability has become a critical concern for massive medical data storage on the blockchain []. To overcome these limitations, several works [,,] have proposed hybrid blockchain architectures combining on-chain and off-chain storage, often leveraging IPFS or similar distributed file systems. For instance, MedChain [] employs time-based smart contracts to govern transactions and manage access to encrypted Personal Health Records (PHRs) stored via decentralized networks.

The Medical Internet of Things (MedIoT) systems play a crucial role today in collecting and transmitting large volumes of clinical data generated by connected devices such as biomedical sensors and diagnostic equipment. However, these infrastructures introduce new vulnerabilities related to data security, integrity, and confidentiality. To enhance the security of such environments, several artificial intelligence-based approaches, particularly hybrid deep learning techniques for anomaly detection, have been proposed. Among these approaches, the method presented in [] highlights that these systems remain highly exposed to attacks due to the limited computational capabilities of IoT devices, the lack of robust authentication mechanisms, and the difficulty of maintaining continuous and reliable access control.

Although effective in identifying malicious or anormal behaviors, these AI-based solutions still require robust mechanisms for auditing, traceability, and trust management among stakeholders to be fully operational in clinical settings. In this context, BlockMedCare [] integrates IoT technologies with the Ethereum blockchain and re-encryption techniques to enable secure remote patient monitoring. The scalability of this system is ensured through off-chain storage using IPFS, while transaction throughput is optimized via a PoA consensus mechanism. The integration of blockchain within a medical IoT ecosystem therefore simultaneously addresses confidentiality, resilience, and interoperability challenges, while providing a solid technological foundation for the framework proposed in this work.

Finally, regarding conditional privacy-preserving authentication, the authors of [] propose a blockchain-assisted anonymous authentication and a tree-based group key agreement. Their approach relies on principles such as tree-based group key agreement, conditional anonymity, and mutual authentication, all of which remain highly relevant for collaborative workflows in the healthcare sector. These concepts can inspire the integration of simultaneous authorizations, such as the validation of multiple consent tokens or parallel transactions among geographically distributed professionals. The adoption of such mechanisms in the future work perspectives of this research could further enhance privacy protection within highly collaborative medical environments.

In summary, it is important to clarify that the comparison presented in Table 1 is not the result of direct experimentation or parallel implementation of the systems mentioned. Rather, it is a comparison based on a thorough conceptual and qualitative analysis of existing approaches, based on official publications in the scientific literature. So, in the context of this table, although the reviewed studies demonstrate significant progress in terms of privacy, traceability, and interoperability, several non-functional challenges remain unresolved, particularly those related to extensibility, data governance, and integration across heterogeneous healthcare infrastructures for effective collaborative work.

Table 1.

Comparison of this work with some blockchain-based related works.

The framework proposed in this paper aims to address these limitations through a hybrid blockchain architecture that integrates on-chain traceability with off-chain encrypted storage, enhanced by tokenization mechanisms and DApps. This unified approach combines:

- Compliance by design and self-supervision, embedded directly within smart contracts to enforce process rules and automate workflow execution without third-party intervention.

- NFT-based consent tokens, securely linking access rights to encrypted off-chain medical data.

- A modular design pattern that supports interoperability (via standardized data formats and off-chain references), integration (through a unified abstraction layer for heterogeneous HIS), and extensibility for future system evolution.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Use Case and Medical Activity Design

To illustrate the practical context of this research, a motivating use case focused on a complex medical activity named Cancer Diagnostic Analysis (CDA) is adopted. The CDA activity involves four sub-activities: clinical exam, bronchoscopy, chest radiography, and chest CT scan. The successful completion of the whole activity requires the coordinated participation of various specialists mostly belong to geographically distributed units: an attending physician, a pneumologist, and a radiologist. In real-world healthcare settings, the execution of such interdependent sub-activities exposes several challenges to coordinate first between actors of heterogeneous HIS, and second to ensure traceability and accountability of actors’ interventions, maintaining patient data confidentiality.

The Model-Driven Architecture (MDA) approach [] is adopted in this work not only to automate code generation but also to serve as a structuring mechanism in the design of flexible and interoperable HIS. It thus ensures consistency, semantic compatibility, and interoperability of the models used within the framework.

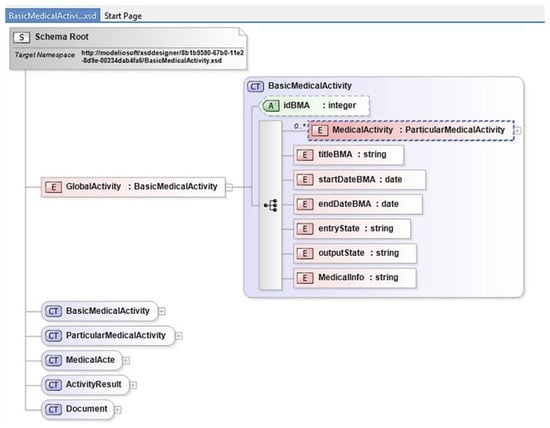

In this context, and in accordance with [], the most suitable structure for modeling a complex medical process is a hierarchical tree structure, referred to as the Medical Activity Pattern (MAP) (Figure 1). Instantiating this metamodel enables the automatic generation of:

Figure 1.

XSD Medical Activity Pattern (MAP).

- Standardized XML/JSON structures, used as interoperable exchange units between heterogeneous systems.

- Solidity artifacts integrated into the smart contract to ensure supervision, traceability, and access control of medical activities.

For instance, taking the CDA activity—which allows us to determine the presence, type, and location of lung cancer—the attending physician initiates the diagnostic workflow with a clinical exam. Based on the examination results, he requests a bronchoscopy from a pneumologist, as well as two additional imaging sub-activities: a chest radiography and a chest CT scan from a radiologist.

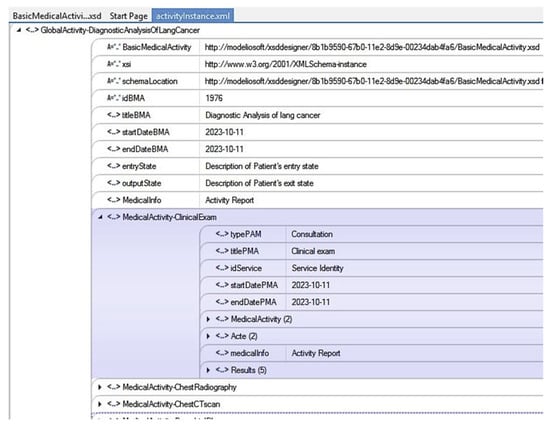

Applying the MDA approach to the CDA use case, we first generated the XML model named Reference Medical Activity (RMA), saved as activityInstance.xml (Figure 2), deriving from the MAP metamodel (Figure 1). Each node of this RMA represents a sub-activity linked to a specific medical specialty and is capable of capturing and storing trace information generated by the corresponding physician during the execution of associated medical acts. This standardized XML representation—or its equivalent JSON standard—is designed to be stored in an IPFS off-chain storage unit and used as a communication, parsing, and querying interface among distributed healthcare systems.

Figure 2.

Graphic XML format of a Reference Medical Activity (RMA).

Furthermore, within the same MDA approach, the details of an extended medical-oriented smart contract metamodel inheriting from the ERC-721 standard [] are presented in Section 3.3. This MDA-driven generativity plays a central role in aligning the business model, data interoperability, and the logic embedded in smart contracts, thereby ensuring coherent modeling and controlled execution of the medical workflow.

3.2. Smart Contract and Hybrid On-Chain/Off-Chain Storage

Since their introduction in 1994, smart contracts have enabled the secure and reliable automation of business processes through blockchain technology. They support the deployment of complex DApps by autonomously executing transactions without requiring oversight from external authorities such as banks, courts, or healthcare institutions []. In the medical domain, where data are generally voluminous, heterogeneous, and highly sensitive, the adoption of a hybrid storage model combining on-chain and off-chain mechanisms becomes essential. In this regard, the proposed framework introduces a hybrid on-chain/off-chain architecture [,] that not only mitigates the scalability limitations inherent to blockchain systems but also ensures compliance with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) [] and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) regulations [].

In this work, by leveraging the capabilities of smart contracts in consent governance, we achieve a strict separation of responsibilities between blockchain-based processing (on-chain) and the storage of medical data (off-chain).

3.2.1. On-Chain Storage (Blockchain Layer)

The blockchain is used exclusively to record events and metadata associated with inter-professional interactions. Elements such as task creation, assignment, and validation within the collaborative workflow are lightweight but essential for ensuring full traceability and auditability. Storing these items on-chain guarantees immutability, tamper-resistant logs, and transparent supervision of medical activities.

Crucially, no personal or clinical information is ever stored on-chain. Only pseudonymized identifiers, token references like tokenURI, and cryptographic IPFS hashes pointing to off-chain medical content are maintained in the ledger. This design preserves patient privacy while maintaining verifiable links between on-chain transactions and off-chain medical data.

3.2.2. Off-Chain Storage (IPFS Layer)

Sensitive patient data, such as imaging files, examination results, and detailed medical reports, are encrypted and stored exclusively off-chain using IPFS. Through the smart contract logic, IPFS operates as a distributed, content-addressable peer-to-peer storage protocol [], enabling reliable verification of data integrity and consistent identification of identical content across the network.

In this model, all patient-related information (e.g., RMA documents, imaging files) is stored and later retrieved directly from IPFS nodes using the unique Content Identifier (CID) associated with each file. This mechanism ensures that only authorized healthcare professionals can access and share medical data securely, as access rights are controlled through on-chain consent tokens.

To guarantee long-term availability while optimizing storage capacity, each IPFS node performs periodic garbage collection to remove unpinned blocks. Consequently, any data object that must remain persistently available must be explicitly pinned and may be delegated to specialized pinning services, which maintain the content in exchange for periodic maintenance fees [].

3.2.3. Compliance with GDPR Requirements

The adoption of such a hybrid architecture ensures full alignment with the GDPR obligations, including the right to erasure andright to be forgotten. In practice, effective data deletion is achieved by

- first removing the sensitive off-chain content from pinned IPFS nodes,

- followed by destruction of the corresponding decryption key, with on-chain invalidation of its associated NFT/tokenURI pointer via an update of the token status (revoked/expired), which prevents any future use or dissemination.

This approach renders any residual fragments permanently unusable and conforms to the European Data Protection Board (EDPB) recommendations on distributed systems. Since no personal information resides on-chain, immutability does not conflict with GDPR requirements.

3.2.4. Compliance with HIPAA Requirements

The key requirements of HIPAA have been incorporated in this work, with a particular focus on the following three essential rules:

- Privacy Rule: The hybrid storage model ensures that no Protected Health Information (PHI) is ever stored directly on the blockchain. Only metadata and pseudonymized identifiers are recorded on-chain, enforcing a strict separation between sensitive patient data and immutable ledger entries. All medical content remains encrypted and stored off-chain.

- Security Rule: Compliance is achieved through a compliance-by-design approach embedded directly into the smart contracts. So, all off-chain medical content is systematically encrypted before storage. And the authentication is enforced through digital wallets, and access control is strictly limited to authorized actors via a PoA-based permission mechanism. Finally, smart contracts provide tamper-proof logging of access events and transactions, ensuring the auditability required by HIPAA.

- Integrity Rule: Data integrity is guaranteed through a tokenization mechanism that cryptographically links off-chain data to on-chain records. Thereby, the integrity of patient data stored in IPFS is ensured by its CID. This CID is consistently cross-checked with the NFT-based tokenURI stored on-chain. Any unauthorized modification of the off-chain content would immediately invalidate the CID, making tampering easily detectable.

3.3. Smart Contract and Token Modeling

Within the smart contract paradigm, the notions of token, consent, and transaction have traditionally been linked to financial activities or multi-party contractual exchanges. Within complex medical workflows, a fundamental challenge emerges in ensuring and securing transactions in a decentralized environment. In this study, each transaction is explicitly linked to either an interaction between healthcare participants or an on-chain/off-chain data exchange operation, ensuring both traceability and auditability. Therefore, every transaction must be initiated through permissions embedded within the corresponding smart contract and authorized via an explicit consent mechanism. In this context, consent refers to a participant’s formal authorization to perform a specific action or share medical data []. So, to manage consents efficiently, the proposed framework employs a tokenization mechanism that leverages tokens, digital units of value or rights within the blockchain ecosystem, for unique representation of entities or permissions. While tokens are commonly used to symbolize financial assets, ownership, or voting rights [], here they are designed to uniquely and securely represent patient data in a non-fungible manner. Specifically, we adopt and extend the ERC-721 standard commonly used for NFTs, which defines unique, indivisible, and non-interchangeable digital assets []. These NFTs are adapted here to fulfill system requirements that ensure fine-grained control over patient data access and consent management while addressing potential compatibility and privacy constraints inherent to medical applications.

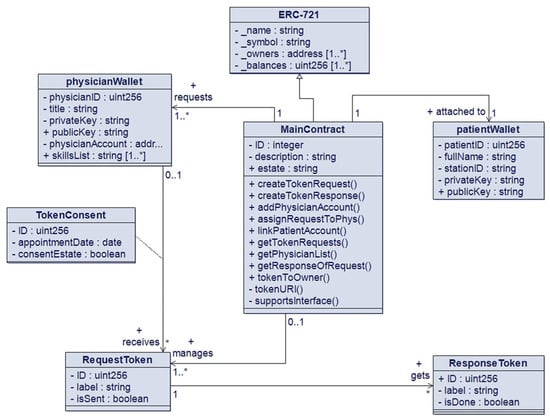

The ERC-721 standard defines the essential functionalities for managing non-fungible tokens (NFTs), primarily designed for finance-oriented transactions []. However, several of its native operations are not directly compatible with the requirements of information management, particularly when handling non-fungible medical entities such as patient identities or unique medical records. To address these limitations and following the MDA approach, we propose an extended smart contract model that inherits from ERC-721 while redefining and enriching specific features to accommodate healthcare-specific needs. Consequently, the ERC-721 specification is adopted as the foundational token model for designing a medical-oriented smart contract pattern, derived from the metamodel illustrated in Figure 3. The central component, referred to as MainContract, constitutes the core module deployed and executed on-chain, incorporating customized functions such as the following:

Figure 3.

Pattern diagram.

- addPhysicianAccount(): Registers a new blockchain address of a physician within the contract. During a patient’s treatment process, the attending doctor can add each specialist physician (e.g., pneumologist, radiologist) required to perform assigned medical activities.

- createTokenRequest(): Generates a request token that enables secure access to the diagnostic or procedural requests issued by the attending physician and directed to a specific specialist.

- The MainContract module is designed to interact with three complementary components: PhysicianWallet, RequestToken, and PatientWallet.

As illustrated in Figure 3, MainContract enables the dynamic registration of medical professionals by specialty, defining thereby a collaborative team that will be responsible for performing a patient’s treatment in a workflow system. Each physician is represented by a dedicated PhysicianWallet module, which facilitates authenticated interactions through a DApp interface. Likewise, the patient, modeled as a unique entity within the blockchain, is assigned a PatientWallet that serves both as a secure digital identity anchor and as a personal interface for monitoring medical activities within the system. Once the patient’s profile is registered through DApp, a PatientWallet is automatically generated, ensuring traceability, authenticity, and integrity of all subsequent healthcare interactions.

In summary, the resulting model constitutes a medicalized version of ERC-721, in which several native behaviors of the standard that are unsuitable for the constraints of the healthcare sector are redefined. The tokens introduced in this model, namely RequestToken and ResponseToken, therefore do not merely represent digital assets; they become genuine medical access tokens, enabling fine-grained access control and self-supervising of the collaborative workflow. Specifically, they allow the following:

- Encoding dynamic consent rules, executed and validated through the PoA mechanism.

- Defining role-based access rights (physician, specialist, radiologist, patient).

- Prohibiting unrestricted token transfers, contrary to the standard ERC-721 behavior, to comply with regulatory frameworks and medical confidentiality principles.

- Associating each NFT with a specific segment of the medical record, ensuring strictly limited access to the necessary scope.

- Attaching structured metadata (XML/JSON) describing activity models and corresponding medical artifacts.

- Introducing additional states, transitions, and permissions absent from the ERC-721 standard (e.g., issued, consumed, revoked, delegated), which are essential for modeling supervised clinical workflows.

Thanks to these extensions, the NFT is transformed into a genuine by-design compliant medical access token, playing a central role in the governance of sensitive information. It not only ensures the traceability and auditability of operations but also provides rigorous and dynamic consent control, while guaranteeing secure interactions within distributed collaborative workflows. The structural adaptation of the ERC-721 standard constitutes a central contribution of this work. The specifics of its implementation in the Solidity language are further discussed in Section 3.5.

3.4. Smart Contract and Tokenization Mechanism

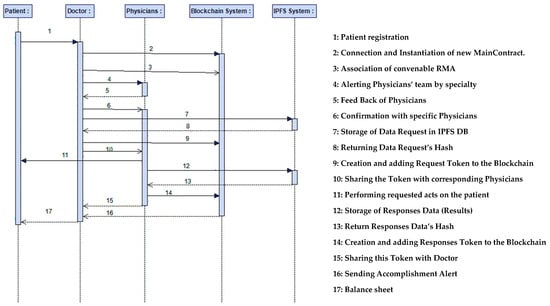

The RequestToken and ResponseToken modules in the proposed design pattern, shown in Figure 3, play a pivotal role in implementing the consent management mechanism. They govern and secure access to each component of patient’s RMA, the data of which is stored off-chain within the IPFS distributed storage system. To preserve both the integrity and confidentiality of medical information while ensuring logical and auditable interactions among healthcare actors, a tokenization-based workflow is designed. This workflow models the creation, exchange, and validation of consent tokens through smart contract operations. The complete interaction process is illustrated in the sequence diagram shown in Figure 4, which depicts the chronological execution of transactions and the communication between the participating entities (doctor, specialist, patient, IPFS storage, and smart contract).

Figure 4.

Sequence diagram of tokenization workflow.

As illustrated in Figure 4, once the blockchain environment is deployed and operational, the attending physician initiates the medical process by accessing the dedicated DApp. Following the patient registration phase, the MainContract is instantiated and executed on the blockchain, embedding the patient’s information retrieved from the hospital’s reception service. The physician then selects and associates the appropriate RMA, illustrated in Figure 2, which is automatically stored as a Data Request in the distributed IPFS network after confirmation with the physician’s team. Upon successful storage, IPFS generates a CID hash, which is subsequently recorded on the blockchain within a RequestToken as a tokenURI. This token establishes a secure and traceable linkage between the on-chain transaction and the off-chain medical data. Finally, the RequestToken is transmitted to the designated specialist physicians, granting them authorized and auditable access to perform their respective examinations on the patient.

3.5. Smart Contract Implementation

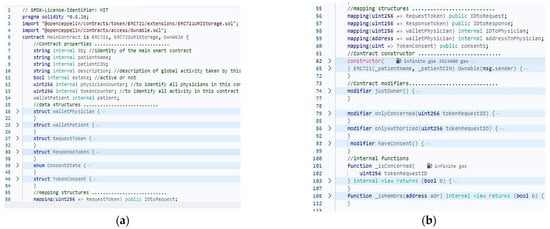

Solidity [] is currently the most mature and widely adopted programming language for smart contract development, supported by a robust community and a comprehensive set of development tools. Unlike traditional object-oriented languages such as Java or C++, Solidity does not implement the Factory Contract pattern in the same way; instead, equivalent functionality is achieved through its contract deployment mechanisms, as reflected in the proposed design pattern. The implementation began with the development, compilation, and local testing of the main contract using Remix IDE, resulting in the deployment-ready MainContract. As illustrated in Figure 5, each contract instance encapsulates the following components:

Figure 5.

Smart contract Solidity code: properties and structures (a), modifiers and functions (b).

- Patient information: including patientName, patientID, a description of the associated global medical activity, and the PatientWallet.

- Contract information: encompassing the unique contract identifier (ID) and its operational state.

- Additional properties: such as counters for registered physicians and generated tokens, as well as wallet structures that enable self-managed consensus for validating transactions.

In a blockchain environment, a consensus mechanism ensures that the outcomes of smart contract executions are collectively validated and accepted by all network nodes. In the context of healthcare collaboration, ensuring process compliance is critical. Two main approaches [,] can be adopted:

- The first approach: Compliance through monitoring, which employs adapters to record and verify all transactions generated by a process on the blockchain.

- The second approach: Compliance by design, in which each step of the medical process is explicitly encoded and executed through blockchain transactions. In this, a transaction is validated only if it adheres to the predefined collaborative process model. For example, a surgical intervention cannot be executed until the corresponding preparatory steps have been validated by the appropriate medical actors.

To achieve efficient and reliable validation, a PoA consensus mechanism is implemented on the personalized smart contract under a compliance-by-design approach. In this model, only pre-approved authorities, belonging to one or more trusted entities, are authorized to validate transactions and append blocks to the chain. And as presented in Figure 5, several modifiers have been implemented into the smart contract, as compliance constraints, to restrict the execution of critical functions to authorized participants, ensuring that only predefined authorities or validated actors can initiate or approve transactions.

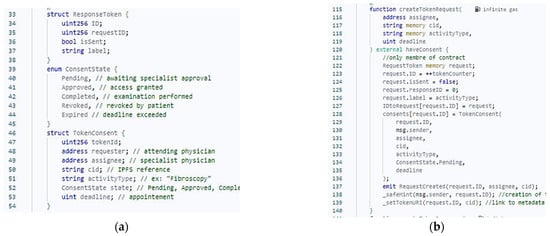

In addition, multiple functions have been developed to operationalize the previously described tokenization workflow (seen in Figure 4), managing the interactions and data exchanges between the system’s actors. As previously mentioned, unlike traditional NFTs, which typically represent static digital assets, the TokenConsent model here, as illustrated in Figure 6, encapsulates:

Figure 6.

Smart contract Solidity code: consent and structured medical metadata (a), createTokenRequest function (b).

- Structured medical metadata (e.g., examination type, professional identity, deadlines, validation state) as shown in Figure 6a.

- Consent State and CID referencing encrypted medical data stored on IPFS.

These extensions transform the NFT into an operational token that can represent, for example, a medical request through the createTokenRequest function (Figure 6b), or a medical result via createTokenResponse, among others. Based on the configuration of the TokenConsent structure, the smart contract automatically infers access authorizations and monitors workflow progression.

In summary, smart contracts are employed effectively to automate medical services, adopting DApps that extend beyond conventional integration mechanisms by enabling a decentralized form of system coordination, eliminating the need for a central authority. This coordination is achieved through the synergistic use of blockchain technology, smart contracts, and distributed storage. Consequently, this research emphasizes decentralized interoperability among heterogeneous HIS by introducing a standardized abstraction layer based on DApps. This layer leverages XML/JSON data formats and IPFS off-chain storage to ensure secure, traceable, and privacy-preserving data exchange across interconnected healthcare environments.

4. Framework Deployment and Experimentation

4.1. System Architecture

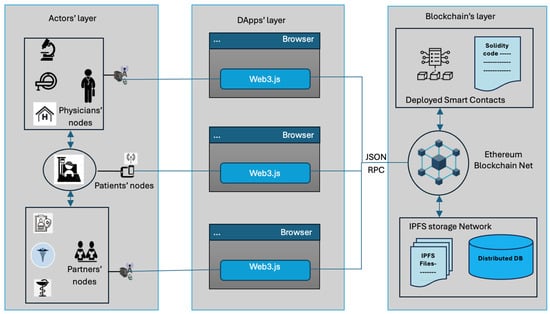

The Cancer Diagnostic Analysis (CDA) case study, previously introduced in Section 3.1, is revisited here with a focus on implementation details and prototype evaluation. A patient suffering from a complex pathological case such as CDA typically requires the intervention of multiple specialized physicians. These specialists, such as radiologists, pulmonologists, and cardiologists, often belong to geographically distributed medical units operating through heterogeneous and independent HIS. Moreover, patients and physicians frequently interact with external stakeholders, including insurance companies, health ministries, research institutions, and pharmacies. To achieve the objectives outlined in the introduction section and to facilitate the implementation of the proposed framework, this subsection first presents the system architecture, followed by the progressive development and experimentation of the case study. The proposed system architecture is structured into three following principal layers as shown in Figure 7:

Figure 7.

Architecture of system actors.

- Actors Layer: This layer encompasses all entities interacting within the system and is composed of three categories of nodes:

- Patient Nodes: Represented by patients’ smartphones, these nodes enable individuals to monitor their medical processes and communicate securely with their corresponding medical teams through DApps.

- Physician Nodes: Allow healthcare professionals to connect to the blockchain-based healthcare network using their computers or mobile devices. These nodes act as validators and process supervisors, ensuring the integrity and compliance of medical workflows.

- Partner Nodes: Extend the network to include external stakeholders such as health ministries, insurance organizations, and pharmacies. Their integration promotes cross-institutional collaboration and service interoperability within the broader healthcare ecosystem.

- Application Layer: This layer hosts DApps, developed using Web3 technologies, which serve as the interaction interface between system actors (patients, physicians, and partners) and the underlying blockchain. It manages user authentication, contract deployment, signature operations, and transaction handling, ensuring seamless communication across heterogeneous platforms using JSON/RPC standards.

- Blockchain and Storage Layer: The core layer of the system consists of the blockchain network, where Medical Smart Contracts are deployed, instantiated, and executed. These contracts automate the medical workflow according to the compliance model integrated within them. Complementing the blockchain, IPFS is employed as an off-chain distributed storage system to ensure consistent, scalable, and secure storage of patients’ medical data.

4.2. System Deployment

Based on the proposed architecture given in Figure 7, a development and simulation environment has been established across the three layers described above. Each layer has been configured to reproduce real-world operating conditions and also to deploy and validate the proposed framework under controlled experimental settings.

4.2.1. Blockchain Layer Configuration

Remix Ethereum IDE, used as a Solidity development environment, was selected as the primary emulator for simulating a local Ethereum blockchain. This tool provides an efficient and interactive interface for deploying and testing smart contracts prior to live deployment. After successful implementation and validation, the smart contract can be deployed to a public or consortium blockchain network for extended testing and scalability assessment.

The MetaMask browser extension was employed to manage user wallets and transaction signing. For off-chain data management, the IPFS network was accessed through the “http://nft.storage” platform using the Brave browser. This platform provides encrypted off-chain storage, enabling the upload of medical data and the retrieval of corresponding CID that uniquely represents the stored content. CID is then embedded in the associated NFT on the blockchain, forming a verifiable reference (ipfs://CID) to the convenable medical data. Thus, data access is granted only to holders of the authorized NFT, ensuring both traceability and privacy.

4.2.2. DApps Layer Configuration

An intermediate communication layer was developed to enable secure interaction between the system actors (patients, physicians, and partners) and the blockchain network. The corresponding DApps user interfaces were implemented using the Node.js runtime environment. The setup included the installation of essential packages such as npm, Web3.js, Bootstrap framework, and Solc (Solidity Compiler) to facilitate the development, integration, and testing of smart contracts. DApps allow each actor to seamlessly interact with the blockchain, execute transactions, and access the IPFS-stored data through a unified and user-friendly web interface.

4.2.3. Actors Layer Configuration

To simulate a realistic healthcare environment, individual accounts were created for each physician and patient using MetaMask wallets, representing their respective identities and permissions within the blockchain network. Three computing nodes were configured to emulate the operational roles of the system’s main actors:

- Node 1 (Specialist Physician Node): A laptop equipped with an Intel® Core™ i5-6300U CPU (2.40 GHz, 4 cores) and 8 GB RAM, configured with the DApp environment to simulate the workstation of a specialist physician.

- Node 2 (Attending Physician Node): A laptop powered by an Intel® Core™ i7-1100U CPU (2.60 GHz, 8 cores) and 16 GB RAM, serving as the attending physician’s main environment for initiating and supervising diagnostic workflows.

- Node 3 (Patient Node): A smartphone with a Qualcomm® Snapdragon™ 665 processor and 8 GB RAM, running the DApp interface to allow the patient to track and follow their medical process in real time.

This distributed configuration enables the simulation of multi-actor interactions, ensuring realistic validation of workflow execution, data sharing, and tokenized consent mechanisms across heterogeneous platforms.

4.3. Experimentation and Evaluation

4.3.1. Collaborative Aspect with Self-Supervision

One of the major strengths of the proposed framework lies in its ability to achieve distributed integration among heterogeneous healthcare systems without the need for centralized control by leveraging DApps and smart contracts. This subsection demonstrates how the proposed system effectively addresses key non-functional challenges, particularly those related to process automation, traceability, and self-supervision in collaborative healthcare workflows.

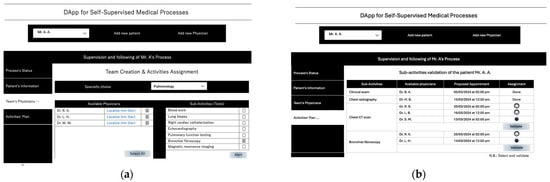

Through the CDA use case prototype, it became clear that each attending physician can create, manage, monitor, and supervise the progression of a patient’s CDA adopting DApps using the web3 User Interface (UI). As an indicator of the system extensibility, the attending physician can dynamically create a medical team in real time for each patient by finding and inviting specialists according to the required sub-activities. Via the DApps interfaces, all stakeholders can securely interact with the deployed smart contract corresponding to the given pathological case. To illustrate this behavior, Figure 8a presents the status of the global medical activity for the started CDA use case that corresponds to the patient in Figure 8b. Once the attending physician specifies the patient’s pathological case, the system automatically associates the corresponding RMA. On the process status page, each sub-activity is displayed along with its assigned physician, scheduled appointment, and corresponding interaction buttons (e.g., Get response if completed, or Remind Physician otherwise).

Figure 8.

UI of process status (a); UI of patient’s information (b).

To ensure the scalability of the system and to support the dynamic constitution of the medical team responsible for carrying out this CDA, the framework provides an interactive mechanism to the attending physician. As shown in Figure 9a, the interface allows the doctor to select, for each required specialty, available physicians based on their geographical localization and professional profiles. In the next step, the attending physician specifies the medical tests or sub-activities to be performed and sends invitations (alerts) to the selected specialists. Each sub-activity displays a list of available physicians, along with their proposed appointment time. The attending physician then selects the most suitable specialist, considering time, location, and estimated cost. By clicking the “validate” button, a RequestToken is automatically generated and transmitted to the selected physician, granting them authorized access to the attending doctor’s request through the smart contract. Upon receiving all required confirmations, the medical team composition is finalized, marking the completion of the CDA’s workflow.

Figure 9.

UI for dynamic constitution of team (a), validation stage of team by sub-activities (b).

Simultaneously, the integration of off-chain IPFS storage ensures secure and scalable handling of large medical datasets (including requests and results) in standardized JSON/XML formats. Access to these files is controlled through personalized non-fungible tokens (NFTs) that act as digital authorization keys, linking each participant’s identity to specific medical data items (see Figure 4). After the team’s validation and confirmation, the attending physician can monitor and supervise the workflow progress directly via the process status interface, as given in Figure 8a. So, clicking on the “Get response” button, the physician retrieves the results submitted by each specialist from the IPFS storage, enabling real-time tracking of the diagnostic process and transparent coordination across all involved actors.

The patient can also monitor the progress of their diagnostic process through the DApp. This interface allows the patient to visualize the status of each medical sub-activity and locate the involved healthcare professionals according to the previously scheduled appointments. All interactions are securely managed through the corresponding MainContract instance on the blockchain, thereby ensuring complete traceability, data integrity, and transparent coordination throughout the entire medical workflow.

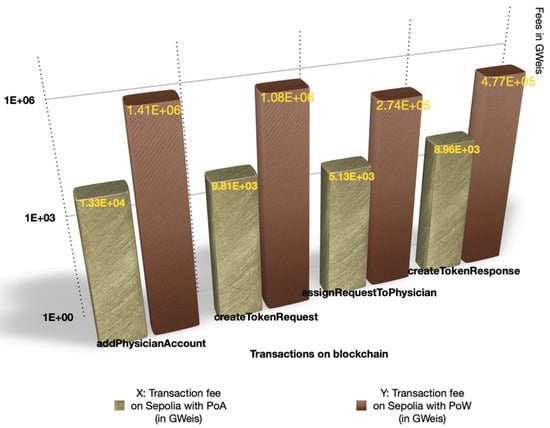

4.3.2. Transaction Time and Gas Measures

In evaluating the performance of the proposed framework, a key objective is to demonstrate its ability to achieve a reduction of more than 90% in energy consumption compared to traditional blockchain configurations. Most of the incurred costs are associated with the deployment of the smart contract governing the DApp and the invocation of contract functions (transactions) executed on the blockchain. Accordingly, all performance metrics were measured directly on the blockchain environment during the evaluation phase.

To compute the transaction fees, three main parameters—gasConsumed, baseFee, and priorityFee—were collected for each executed transaction. These parameters were obtained from the wallet of the actor performing the operation immediately after transaction validation. It is important to note that transaction fees are deducted regardless of whether the transaction succeeds or fails. Therefore, estimating the required gas costs in advance is essential to prevent transaction failure due to insufficient funds. To mitigate this issue, a preventive mechanism was integrated into the smart contract logic to ensure that sufficient gas is allocated before each execution. The total transaction fee is calculated using the following equations:

(expressed in units such as ETH, wei, gwei = 10−9 ETH) []

transactionFee = gasConsumed × gasPrice

During the experimental phase, two blockchain configurations were employed to evaluate transaction performance and cost efficiency:

- The Sepolia testnet that is operating under the PoA consensus mechanism.

- The Sepolia testnet that is configured with the PoW consensus mechanism.

To illustrate the measurement procedure, five representative transactions were selected, as detailed in Table 2, along with their corresponding execution fees and gas consumption metrics:

Table 2.

Results of total cost of transactions in the presented case study.

- Constructor (Deployment): Deployment of a new patient instance through a single transaction.

- addPhysicianAccount(): Addition of four physician accounts (one attending physician and three specialists) through four distinct transactions.

- createTokenRequest(): Creation of a tokenized request initiated by the attending physician.

- assignRequestToPhy(): Assignment of the TokenRequest to three specialist physicians via three separate transactions.

- createTokenResponse(): Generation of response tokens by the specialists in three corresponding transactions.

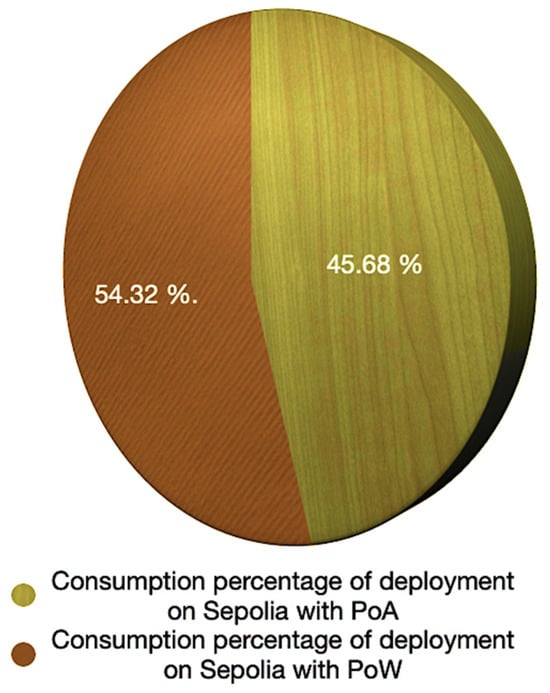

5. Results

The operations presented above collectively represent the core workflow of the proposed healthcare framework, providing a concrete basis for analyzing gas efficiency and energy savings across both consensus mechanisms.

Table 2 summarizes the obtained results, presenting the transaction costs (expressed in Gwei) for both experimental configurations (X and Y) as well as the cost difference (Δ = Y − X) between them. And as illustrated in Figure 10 and Figure 11, the overall transaction fees, including both smart contract deployment and function execution, are significantly lower under the PoA consensus mechanism. In contrast, the Proof-of-Work (PoW) configuration exhibits substantially higher gas consumption and transaction costs due to its computationally intensive validation process. These results clearly demonstrate that adopting the PoA mechanism enables the proposed framework to operate with minimal transaction overhead, achieving a notable reduction in energy consumption and operational costs while maintaining the required level of security and traceability for medical workflows.

Figure 10.

Transactions fee variation between PoA Net and PoW Net.

Figure 11.

Consumption percentage of deployment gas between PoA Net and PoW Net.

On the other hand, adopting a compliance-by-design approach integrated into the smart contract and operating under the PoA mechanism also reduces transaction times compared with PoW. In this context, the validation time for a given transaction becomes negligible compared with the validation time across multiple network nodes [].

6. Analysis and Discussion

Following the implementation of the proposed prototype, the evaluation results demonstrate the extent to which the framework meets the research objectives defined in Section 1. Beyond traceability and transparency, the design of an ERC-721-based medical NFT pattern enables rigorous and dynamic self-supervision of consent, while securing interactions within distributed collaborative workflows. All transactions are transparently recorded on the blockchain, ensuring immutable traceability of medical processes.

Regarding data integrity and confidentiality, a tokenization-based workflow was designed to model the creation, exchange, and validation of consent tokens through smart contract operations, while maintaining coherent and auditable interactions among healthcare stakeholders. In this context, the adoption of a hybrid on-chain/off-chain storage architecture plays a crucial role in ensuring compliance with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA).

Furthermore, the integration of a compliance-by-design approach within smart contracts enables effective automation of medical services through Decentralized Applications (DApps), which go beyond traditional integration mechanisms. These applications support decentralized coordination of distributed systems without relying on a central authority. Consequently, this work emphasizes decentralized interoperability between heterogeneous Hospital Information Systems (HIS) by introducing a standardized abstraction layer based on DApps. This layer leverages XML/JSON data formats and off-chain IPFS storage to ensure system extensibility, interoperability with existing HIS, and secure, traceable, privacy-preserving data exchange within interconnected healthcare environments.

In terms of performance, the cost analysis confirms that adopting a Proof-of-Authority (PoA) consensus mechanism significantly reduces deployment and transaction costs and latency compared to Proof-of-Work (PoW). Experimental results show a reduction of more than 90% in transaction fees and energy consumption, making the proposed approach particularly suitable for real healthcare environments where large numbers of daily transactions occur.

However, despite the effectiveness demonstrated by the prototype in satisfying key inter-hospital system requirements, such as traceability, confidentiality, and workflow coordination, several limitations remain. First, the experimentation was conducted in a simulated environment with a limited number of nodes, which does not yet allow accurate evaluation under real conditions, particularly in distributed multi-institution infrastructures involving large data volumes and high transactional loads. In a real deployment, network latency could significantly affect transaction validation times, DApp synchronization, and off-chain access to IPFS storage.

A second challenge concerns integration with existing HIS infrastructures. Although the proposed approach provides an abstraction mechanism based on standardized formats (XML/JSON) and a DApp layer, the diversity of protocols, proprietary APIs, and heterogeneous infrastructures represents an additional barrier. Ensuring full interoperability with standards such as HL7-FHIR or IHE XDS will require further efforts.

Finally, despite the use of a PoA consensus and a hybrid on-chain/off-chain architecture, the overall scalability of the system could be further improved, particularly when handling multiple complex workflows simultaneously. These limitations open promising avenues for future research.

7. Conclusions and Future Works

This work introduces an innovative blockchain-based architecture enabling the self-supervision of collaborative medical workflows, relying on smart contracts, healthcare-oriented NFTs, and decentralized storage through IPFS. The evaluation results demonstrate that the proposed approach strengthens confidentiality, traceability, and coordination among healthcare professionals, while significantly reducing operational costs through the adoption of a Proof-of-Authority (PoA) consensus mechanism. The framework therefore proves effective as a decentralized integration solution for heterogeneous healthcare systems, establishing a sustainable, auditable, and compliance-by-design collaboration model within distributed medical environments.

However, real-world deployment remains essential to provide deeper insights into critical aspects such as network latency, scalability under realistic data and transaction loads, and integration challenges with existing healthcare infrastructures. These aspects must be further explored to fully assess the practical benefits and limitations of the proposed framework.

To validate large-scale integration and enhance system performance, several research perspectives are envisioned:

- Conducting distributed multi-site experiments to quantify network latency, transaction throughput, and system resilience.

- Extending the platform toward multi-blockchain environments (Ethereum, Hyperledger Fabric, consortium chains) to improve cross-chain interoperability.

- Developing standardized HIS connectors based on HL7-FHIR, DICOM, or IHE to facilitate adoption and seamless integration.

In this context, deploying and evaluating the framework on Hyperledger Fabric and other permissioned blockchain platforms is expected to address the current heterogeneity of blockchain technologies and to strengthen interoperability and integration across multiple decentralized healthcare ecosystems. This direction is also anticipated to enhance system extensibility and promote adoption in real clinical environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, investigation, software, experimentation, writing—original draft, and writing—review and editing: A.K.; supervision, investigation, and writing—review and editing: H.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| CDA | Cancer Diagnostic Analysis |

| CID | Content Identifier |

| DApp | Distributed Application |

| IPFS | InterPlanetary File System |

| MDA | Model-Driven Architecture |

| NFT | Non-Fungible Token |

| PoA | Proof-of-Authority |

| PoW | Proof-of-Work |

| RMA | Reference Medical Activity |

| HIPAA | Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act |

| GDPR | General Data Protection Regulation |

| EDPB | European Data Protection Board |

| ZKP | Zero-Knowledge Proofs |

References

- Eid, J.; Brattebø, G.; Jacobsen, J.K.; Espevik, R.; Johnsen, B.H. Distributed Team Processes in Healthcare Services: A Scoping Review. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1291877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaddari, A.; Malki, M.O.C.; Elmdeghri, S.B. A Pattern-Based Workflow to an Automatic Planning and Monitoring of Medical Activities’ Processes. Int. J. Innov. Comput. Inf. Control. 2016, 12, 1209–1225. [Google Scholar]

- Reisman, M. EHRs: The Challenge of Making Electronic Data Usable and Interoperable. Pharm. Ther. 2017, 42, 572–575. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, C.S. Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System. SSRN J. 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, G. Ethereum: A Secure Decentralised Generalised Transaction Ledger. Ethereum Proj. Yellow Pap. 2014, 151, 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Androulaki, E.; Barger, A.; Bortnikov, V.; Cachin, C.; Christidis, K.; Caro, A.; Enyeart, D.; Ferris, C.; Manevich, Y.; Laventman, G. Hyperledger Fabric: A Distributed Operating System for Permissioned Blockchains. In Proceedings of the thirteenth EuroSys conference, Porto, Portugal, 23–26 April 2018; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Ekblaw, A.; Asaf, A. MedRec: Medical Data Management on the Blockchain. Viral Communications. 2016. Available online: https://viral.media.mit.edu/pub/medrec (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Zhang, P.; White, J.; Schmidt, D.C.; Lenz, G.; Rosenbloom, S.T. FHIRChain: Applying Blockchain to Securely and Scalably Share Clinical Data. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2018, 16, 267–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saripalle, R.; Runyan, C.; Russell, M. Using HL7 FHIR to Achieve Interoperability in Patient Health Record. J. Biomed. Inform. 2019, 94, 103188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahnaz, A.; Qamar, U.; Khalid, A. Using Blockchain for Electronic Health Records. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 147782–147795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, P.; Beinke, J.H.; Fitte, C.; Schulte To Brinke, J.; Teuteberg, F. Generating Design Knowledge for Blockchain-Based Access Control to Personal Health Records. Inf. Syst. E-Bus. Manag. 2021, 19, 13–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Xiong, Z.; Zhu, J.; Gao, S.; Yang, W. A Privacy-Preserving Auction Mechanism for Learning Model as an NFT in Blockchain-Driven Metaverse. ACM Trans. Multimed. Comput. Commun. Appl. 2024, 20, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, S.; Kumar, N. Blockchain 2.0: Smart Contracts. In Advances in Computers; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; Volume 121, pp. 301–322. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R.; Xue, R.; Liu, L. Security and Privacy for Healthcare Blockchains. IEEE Trans. Serv. Comput. 2022, 15, 3668–3686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Zhu, P.; Xiao, F.; Sun, X.; Huang, Q. A Blockchain-Based Scheme for Privacy-Preserving and Secure Sharing of Medical Data. Comput. Secur. 2020, 99, 102010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakhar, A.K.; Singh, M.; Sharma, R.; Viriyasitavat, W.; Dhiman, G.; Goel, S. A Blockchain-Based Privacy-Preserving and Access-Control Framework for Electronic Health Records Management. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2024, 83, 84195–84229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, L.; Materwala, H. BlockHR: A Blockchain-Based Framework for Health Records Management. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Computer Modeling and Simulation, Brisbane, QLD, Australia, 22–24 June 2020; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 164–168. [Google Scholar]

- Guidi, B.; Michienzi, A.; Ricci, L. Data Persistence in Decentralized Social Applications: The IPFS Approach. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 18th Annual Consumer Communications & Networking Conference (CCNC), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 9–12 January 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Q.; Song, Z.; Mong Goh, R.S.; Li, Y. Building an Ethereum and IPFS-Based Decentralized Social Network System. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 24th International Conference on Parallel and Distributed Systems (ICPADS), Singapore, 11–13 December 2018; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, A.; Tian, H. Secure Sharing of Electronic Medical Records Based on Blockchain and Searchable Encryption. Electronics 2025, 14, 2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daraghmi, E.-Y.; Daraghmi, Y.-A.; Yuan, S.-M. MedChain: A Design of Blockchain-Based System for Medical Records Access and Permissions Management. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 164595–164613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Pawar, P.P.; Addula, S.R.; Meesala, M.K.; Oni, O.; Cheema, Q.N.; Haq, A.U.; Sajja, G.S. AI-Powered Security for IoT Ecosystems: A Hybrid Deep Learning Approach to Anomaly Detection. J. Cybersecur. Priv. 2025, 5, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azbeg, K.; Ouchetto, O.; Jai Andaloussi, S. BlockMedCare: A Healthcare System Based on IoT, Blockchain and IPFS for Data Management Security. Egypt. Inform. J. 2022, 23, 329–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.; Wang, M.; Shen, J.; Vijayakumar, P.; Moh, S.; Wu, Q.M.J. Blockchain-Assisted Conditional Anonymous Authentication and Adaptive Tree-Based Group Key Agreement for VANETs. IEEE Trans. Dependable Secur. Comput. 2025, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiomekong, A.; Camara, G. Model-Driven Architecture Based Software Development for Epidemiological Surveillance Systems. In Studies in Health Technology and Informatics; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, D.P. ERC-721 Nonfungible Tokens. In Getting Started with Ethereum; Apress: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2022; pp. 55–74. ISBN 978-1-4842-8044-7. [Google Scholar]

- Chirtoaca, D.; Ellul, J.; Azzopardi, G. A Framework for Creating Deployable Smart Contracts for Non-Fungible Tokens on the Ethereum Blockchain. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Decentralized Applications and Infrastructures (DAPPS), Oxford, UK, 3–6 August 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 100–105. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, W.; Frye, S. Review of HIPAA, Part 1: History, Protected Health Information, and Privacy and Security Rules. J. Nucl. Med. Technol. 2019, 47, 269–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benchoufi, M.; Porcher, R.; Ravaud, P. Blockchain Protocols in Clinical Trials: Transparency and Traceability of Consent. F1000Research 2017, 6, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Angelo, M.; Salzer, G. Tokens, Types, and Standards: Identification and Utilization in Ethereum. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Decentralized Applications and Infrastructures (DAPPS), Oxford, UK, 3–6 August 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Bank of International Settlements; Auer, R. Embedded Supervision: How to Build Regulation into Blockchain Finance. gwp 2019, 2019, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dannen, C. Introducing Ethereum and Solidity: Foundations of Cryptocurrency and Blockchain Programming for Beginners; Apress: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-1-4842-2534-9. [Google Scholar]

- Charles, W.; Marler, N.; Long, L.; Manion, S. Blockchain Compliance by Design: Regulatory Considerations for Blockchain in Clinical Research. Front. Blockchain 2019, 2, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, W.-T. Optimizing Transaction Fee for Different Decentralized Applications in Ethereum. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Consumer Electronics-Taiwan (ICCE-Taiwan), PingTung, Taiwan, 17–19 July 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 763–764. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Nguyen, K.; Sekiya, H. On the Latency Performance in Private Blockchain Networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 19246–19259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).