Abstract

Global data consumption is experiencing exponential growth, driving the demand for wireless links with higher transmission speeds, lower latency, and support for emerging applications such as 6G. A promising approach to address these requirements is the use of higher-frequency bands, which in turn necessitates the development of advanced antenna systems. This work presents the design and experimental validation of a reconfigurable, low-cost leaky-wave antenna capable of controlling the propagation direction of single-, dual-, and triple-beam configurations in the FR3 frequency band. The antenna employs slotted periodic patterns to enable directional electromagnetic field leakage, and it is based on a cost-effective and simple 3D-printing fabrication process. Laboratory testing confirms the theoretical and simulated predictions, demonstrating the feasibility of the proposed antenna solution.

1. Introduction

In the context of modern communications, the increasing demand of low latency and the unavoidable increment in the data traffic pushes communication systems to explore higher-frequency regions [1,2]. This is why current 5G and specially future 6G standards are particularly interested in the FR3-band and beyond [3,4]. This fact leads to the redefinition of the communication architectures, where antennas play a crucial role [5,6].

The new role to be played by the antennas shall consider the following points: on one hand, the rise in the operation frequency has an inmediate effect on the propagation losses, manifesting non-negligible power losses [7]; on the other hand, more directive beams are now preferred in order to offset the power losses and avoid diffractive effects [8]. More directive platforms have classically been based on parabolic surfaces, but they usually suffer from being bulky, heavy, and big [9,10]. Low-profile configurations have also been explored, highlighting reflectarrays/transmitarrays [11,12,13,14,15], or the recent discoveries in reconfigurable intelligent surfaces [16,17].

Leaky-wave antennas become another option thanks to their low-profile character, especially due to their compactness, since they include the feeding network [18,19]. Pioneering studies about leaky-wave antennas were developed in the 1960s by Prof. Oliner [20], and have continued to be a subject of study and evolution until today [21,22]. Leaky-wave antennas have also benefited from the evolution and improvement of fabrication techniques, with prototypes fabricated in PCB planar technology [23], SIW technology [24,25], and even 3D-printing technology in the last decade [26].

The use of 3D-printing techniques is especially interesting since they offer the opportunity of designing low-cost, fully compact, self-consistent, and even fully dielectric/metallic devices [27,28,29,30]. Modern 3D-printing techniques such as stereolithography (STL) or selective laser melting (SLM) enables a framework where the antenna can be fabricated in a single piece and by a single material, saving many of the typical steps for the fabrication in other technologies. In fact, there exist hybrid configurations where the piece [31] is manufactured in dielectric by STL, and subsequently coated with a metallic film [32]. Though the performance and robustness of these hybrid models are not as good as those metallic-based, they can be employed as a fast and cheap version for testing under controlled conditions [33].

This paper presents a reconfigurable leaky-wave antenna for the future 6G FR3-band based on a fixed core, inside which the feeding wave propagates, and a removable slotted layer, from which radiation escapes. Three different configurations of slotted layers are designed and fabricated, with the aim of exploring single-beam, dual-beam, and triple-beam performances. The design of each is described in the paper, and the radiation mechanism is subject to the periodicity control of the slots. The antenna is manufactured via STL and later on metalized by a commercial metallic spray. In addition to the proof-of-concept nature, the experimental results corroborate the theoretical predictions and make the leaky-wave antenna useful for communication scenarios with one, two, or three independent channels.

The paper is organized as follows: the second chapter presents the theoretical basis over which the antenna will be designed; the third chapter is devoted to the design and simulation of the antenna performance for the three configurations; the last chapter is left for experimental results and validation of the low-cost prototype.

2. Theoretical Basis for the Leaky-Wave Antenna Design

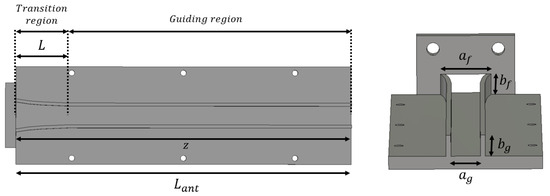

This section is devoted to describing the design process for the 3D-printed leaky-wave antenna, and the theoretical aspects on which it is based. The antenna is conceived to operate around the K-band, which has potential for future 6G applications. As will be detailed below and as can be checked in Figure 1, different regions can be identified in the proposed design: on one hand, a transition of length L that matches the feeding structure and the guiding region of the antenna is highlighted in the rightmost drawing of Figure 1. The feeding structure is a rectangular waveguide that is standarized, WR51, with dimensions mm. The operation band corresponds to the frequency range between 15 and 22 GHz; on the other hand, the guiding region has length , based on a rectangular waveguide with dimensions . This homogeneous region guides the field coming from the transition. Finally, the guiding region is enclosed in the upper part by a metallic sheet with a periodic pattern of slots, from which the radiation leaks out. An example of this upper sheet is shown in Figure 2. This third region will be removable, reconfigurable, and interchangeable, with the aim of inducing different radiation patterns and increasing the number of functionalities. A detailed description of each of these regions is given next.

Figure 1.

Fixed core of the leaky-wave antenna. The leftmost drawing shows the whole extension of the antenna, identifying the transition and guiding region. The rightmost drawing zooms in on the transition region, where the dimensions of the feeding and guiding waveguides are remarked.

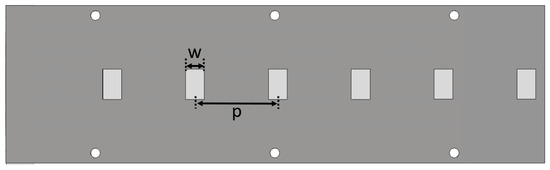

Figure 2.

Example of the upper wall of the leaky-wave antenna.

2.1. Exponential Transition Design

The first key part of the design is the transition that links the feeding waveguide and the guiding region of the antenna. The transition is necessary to ensure a good impedance matching, so that no power is reflected back to the input port. For this, an exponential taper such as that reported in [34] is employed. The admittance evolution along the transition region is described by the following expression:

where is the impedance associated with the mode propagating in the feeding waveguide, is the impedance at each point from the beginning of the transition () to the end of the transition (), and is the increasing/decay ratio of the exponential function. The length of the transition is denoted by L. This length is fixed at the beginning of the design process. Thus, once the impedance values are known, the parameter governing the matching function is

As mentioned above, the feeding and antenna waveguides are rectangular, but with different dimensions. Assuming that just the mode propagates inside each waveguide, their corresponding characteristic impedances are expressed as [34]

with being the wavenumber, and the intrinsic impedance of the vacuum (the waveguides are dielectric free). The propagation constants and are associated with the propagating TE-mode in the feeding and guiding regions, respectively. They are expressed as [34]

with being the larger dimensions of each of the feeding- and guiding-region waveguides. Though is fixed and established according to the WR51-standard, the choice of will follow some criteria described in the following section with the aim of avoiding the excitation of higher-order modes in the guiding region.

2.2. Design of the Guiding Region

The dimensions of the rectangular waveguide for the guiding region, and , are now selected to allow the propagation of the -mode inside, and simultaneously avoid the excitation of the higher-order modes , etc. The frequency region in which these conditions are satisfied must ensure that the propagation constant of the -mode, , is purely imaginary, thus denoting an evanescent mode. This condition involves

resulting in

where is the wavelength at the operation frequency. It is well-known that and are related according to . Similarly, to satisfy the requirement of the propagation of the -mode,

leading to the condition

It is therefore clear that the condition to be satisfied by is

2.3. Design of the Periodic Structure Enclosing the Guiding Region

The upper wall of the guiding region is the zone where the radiation goes out from the antenna. This upper wall includes a periodic distribution of slots from which the field leaks out. The periodicity allows for a real control of the output radiation, enabling the possibility of tailoring the corresponding beam direction as well as its shape. As previously mentioned, the proposed design is reconfigurable, in the sense that the upper wall can manually be interchanged. For this, three different periodic configurations of the upper wall are designed: a first configuration to invoke a single-beam leaky-wave antenna; a second configuration to split the radiation in two individual beams; and a third periodic configuration invoking three output beams.

To allow the field to escape from the interior, we take advantage of the Floquet principle [35], from which the periodicity of the slot distribution and the number of beams is related. Each of the allowed beams is known as an harmonic, whose associated phase constant is expressed as

where indicates the phase constant of the -mode propagating in the guiding region, n indicates the order of the excited spatial harmonic, and p corresponds to the value of spatial periodicity, that is, the distance between the centers of the periodic slots perforated on the upper wall. Figure 2 shows one of the designed configurations, including the dimensions of the design parameters w and p. Once is known, the propagation direction of the nth-order harmonic is computed according to

2.3.1. Single-Beam Leaky-Wave Antenna

To design the upper wall that allows obtaining a single radiated beam, it is necessary to select a spatial harmonic to be excited. The lowest-order harmonic is that with , for which . To prevent the propagation of the next lowest-order harmonics (orders and ), it is therefore necessary to impose the following conditions:

- Non-propagation of . According to (12) the beam-pointing angle corresponding to the spatial harmonic isThis harmonic, and subsequently the rest, are not excited if the argument of the arccos function is higher than 1. This implies after a few calculations that

- Non-propagation of . According to (12), the pointing direction is expressed asThus, now the condition must satisfy

2.3.2. Two-Beams Leaky-Wave Antenna

For the design of the upper wall that allows for the existence of two beams instead of one, the same rationale employed in the single-beam design is used. The lowest-order harmonics to be excited are those with orders and . It is therefore first necessary to obtain the conditions that prevent the propagation of following ones, given by the orders and .

- Non-propagation of . This condition has been established in (14).

- Non-propagation of . Since can be expressed asaccording to (12), the condition to avoid the propagation of the corresponding harmonic is

- Propagation of . Following the rationale in Section 2.3.1, the harmonic with order is excited ifThis condition ensures that the order propagates too.

With all the above conditions, it is concluded that the parameter p of the slotted sheet that ensures the propagation of the harmonics with orders and only needs to satisfy

2.3.3. Three-Beams Leaky-Wave Antenna

The last design of the upper wall is intended to allow the propagation of three simultaneous beams. To achieve this, the propagation of beams corresponding to the spatial harmonics , , and has been proposed. Therefore, it is necessary to obtain conditions to prevent the propagation of the spatial harmonics corresponding to and .

- Non-propagation of . This condition is identical to that in (14).

- Non-propagation of . To avoid the propagation of this harmonic, the periodicity of the structure must obey

- Propagation of . This harmonic propagates if the opposite condition to (19) is invoked. That is,This condition ensures the propagation of the orders .

The previous conditions lead us to conclude that a proper p in the upper wall to ensure the propagation of three simultaneous beams (, , and ) must satisfy

3. Theoretical and Simulated Results

To verify the validity of the theoretical aspects developed above for the design of the three configurations of the leaky-wave antenna, this section is devoted to the simulation of all the scenarios by using CST Studio software. In principle, the antenna is conceived to operate in the K-band, thus the central frequency will be set around GHz. This frequency value is the one employed for the design and optimization of the structure parameters of each of the configurations of the leaky-wave antenna. As described in Section 2.2, the width of the guiding regions must be bounded in the range [/2, ].

A proper value satisfying the requirements in (7) and (9) is mm. Notice that mm. The fact is reducing in the guiding region is advantageous in order to move the cutoff frequency of higher-order harmonics towards higher frequencies. Furthermore, smaller reduces the propagation constant , forcing the outgoing beams to approach the broadside direction instead of endfire. The height is forced to be equal to the height of the feeding waveguide . This can be performed since this value is too small to have any effect over the final antenna performance. According to the WR51-standard, mm. The impedance of the feeding waveguide and the guiding region, and , are therefore computed by using (3) and (4), respectively.

In order to choose the transition length L, it is first necessary to evaluate the length of the entire antenna . The fabrication will be carried out in a FormLab 3 [36], whose fabrication area is about . In this sense, a proper antenna length is cm. By taking into account that the guiding region must be long enough to include several slots of the upper wall, the transition length has final a value of cm. This ensures a length of cm to convert the guiding wave into a leaky wave.

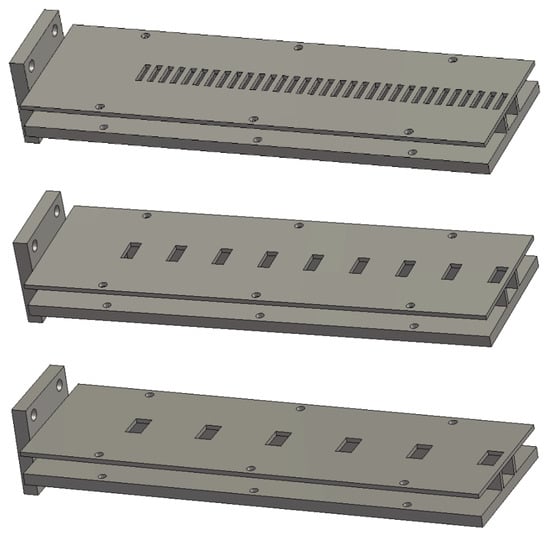

Finally, the upper wall with the slotted periodic pattern is designed as well. The periodicity p is chosen to satisfy the requirements in (17), (21), and (24) to induce single-, double-, and triple-beam emission. For each case, the width of the slots w is selected to ensure that the field propagated inside the antenna leaks out [37]. A summary of the values employed for each antenna is found in Table 1. As can be seen, the transition and guiding region shares the same structure parameters for each leaky-wave antenna. Otherwise, the periodicity and width of the slots of the upper wall varies for each of the three antenna models. Figure 3 shows a sketch of each full model of the leaky-wave antenna.

Table 1.

Values of the design parameters of the antenna.

Figure 3.

From top to bottom, leaky-wave antenna conceived for single-, double-, and triple-beam scanning.

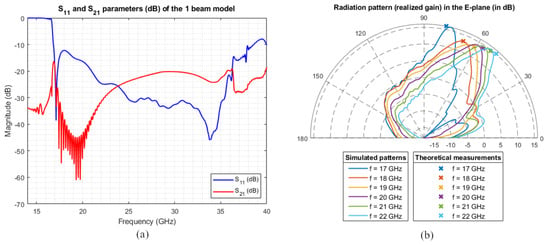

3.1. Simulation of the Single-Beam Leaky-Wave Antenna

The performance of the leaky-wave antenna for the single-beam case is shown in Figure 4. In Figure 4a, the reflection and transmission coefficients are evaluated from the feeding waveguide in terms of the scattering parameters and , respectively. The -parameter estimates the fraction of power coming back to the feeding structure, while computes the fraction of power going out from the opposite side. Figure 4b evaluates the beam direction for different frequencies from 17 to 22 GHz. As can be inferred from both figures, the performance of the antenna is quite good, having below dB, as well as showing the pointing directions of the beam in the predicted positions. This ensures that most of the power leaks out.

Figure 4.

Single-beam leaky-wave antenna. (a) Scattering parameters and . (b) Realized gain (dB): simulation versus theoretical prediction in the range [17–22] GHz.

Figure 4b shows the radiation pattern obtained in CST. The theoretical predictions of the pointing angle for each frequency (maximum gain) are included in the figure by a cross-shaped point. These predictions have been obtained by using (12). The pointing-angle error between simulation and theory barely overpasses 2° in the worst case. Notice that the theoretical results are achieved under the assumption that the periodic structure is infinite. The periodic pattern employed for this case is formed by a distribution of 32 slots, which is a good approximation. It is worth remarking that the gain value oscillates in the range 13–15 dB. A small drop is exhibited at GHz, which coincides with a small increase in the parameter. In any case, dB at this frequency is still under the dB-threshold.

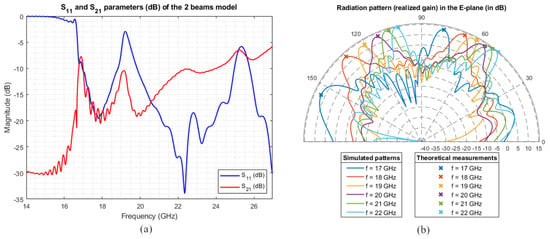

3.2. Simulation of the Two-Beam Leaky-Wave Antenna

In order to induce two-beam operation and assuming the fixed size of the antenna , the periodicity p of the slots in the upper wall is necessarily increased with respect to the single-beam case. The periodic pattern, shown in the middle drawing of Figure 3, now includes just nine slots. Of course, it is expected that the final results show wear due to the reduced number of slots; in addition, some examples found in the literature demonstrate that it can be sufficient [29]. As can be seen in Figure 5a, the scattering parameters have slightly been deteriorated, since a sudden -peak overpasses dB around GHz. The operation range of the antenna is approximately divided into two bands: [17–19] GHz and [20–22] GHz. The radiation pattern, plotted in Figure 5b, exhibits two clear and distinguishable beams for each frequency. The theoretical predictions fit well with the simulations, where the deviations are residual. It can be inferred from the figure that there are frequencies for which the radiation patterns are almost symmetrical, as it happens for GHz. Both beams approximately point towards and from the vertical line (90°). As expected, the rightmost beam is approaching the endfire direction (0°), as in the single-beam case. The leftmost beam follows this tendency as well, but it does not cross the vertical line for the cases under study.

Figure 5.

Double-beam leaky-wave antenna. (a) Scattering parameters and . (b) Realized gain (dB): simulation versus theoretical predictions in the range [17–22] GHz.

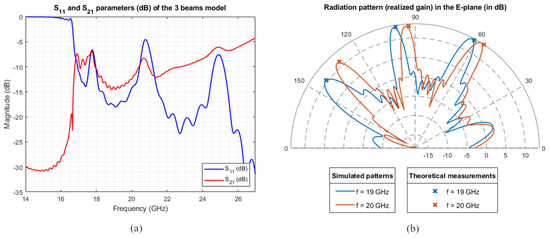

3.3. Simulation of the Three-Beams Leaky-Wave Antenna

The excitation of three-beams, or three harmonics, demands a large periodicity value p for the slot distribution of the upper wall. Concretely, mm for this case, leads to a periodic pattern formed by six slots only. This antenna configuration is sketched at the bottom of Figure 3. Again, we will check below how this small distribution may be enough to redirect the beams to the desired directions. By first analyzing the S-parameters, plotted in Figure 6a, it can be observed that the operating frequency range is now limited to [18–20] GHz. The periodicity induces additional resonances on the whole antenna; thus, the operation range is dramatically reduced. We can otherwise evaluate the performance of the antenna for GHz, where the leakage power seems to be adequate. Figure 6b shows the corresponding radiation pattern. For each frequency, the three beams are clearly distinguished. Adjacent beams have an angular separation of about 30°. Again, the theoretical predictions, obtained under the assumption that the structure is infinite, are in accordance with the direction of the maximum-gain peaks provided by CST. This fact corroborates that the design rules in Section 2 are adequate and can be employed in the future.

Figure 6.

(a) Triple-beam leaky-wave antenna. Structure parameters and . (b) Realized gain (dB): simulation versus theoretical predictions in the range [19–20] GHz.

4. Fabrication and Experimental Results

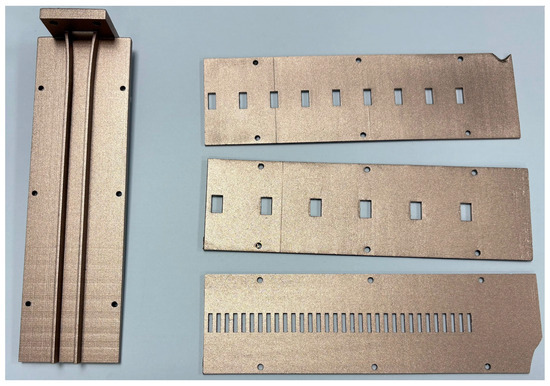

This section is devoted to the experimental verification of the results provided in the previous sections. For this, on one hand, the manufacturing process of the antenna is detailed, where the 3D-printing technique based on STL is employed. The resulting antenna is, originally, fully dielectric and thus must subsequently be metalized. On the other hand, the measurement setup will be described, on which the experimental tests of the antennas will be realized.

4.1. Manufacturing and Experimental Setup

The manufacturing process has been carried out via stereolithography by means of the 3D-printer model Formlabs Form 3+ [36]. After that, a thin metal coating was applied to all the printed pieces by using RS Pro Bronze spray [38]. Figure 7 shows the final products, where the transition region, the guiding region, and the three upper walls are exhibited. It is worth remarking that the conductivity of the spray is not as high as desired; about S/m. This constraint will have influence over the final radiation patterns expected for each antenna configuration.

Figure 7.

Core of the leaky wave and the three configurations of the upper wall.

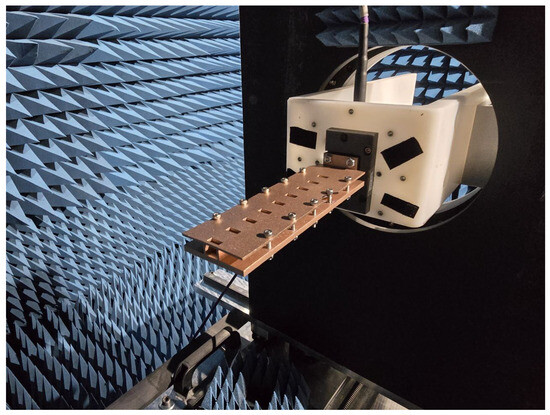

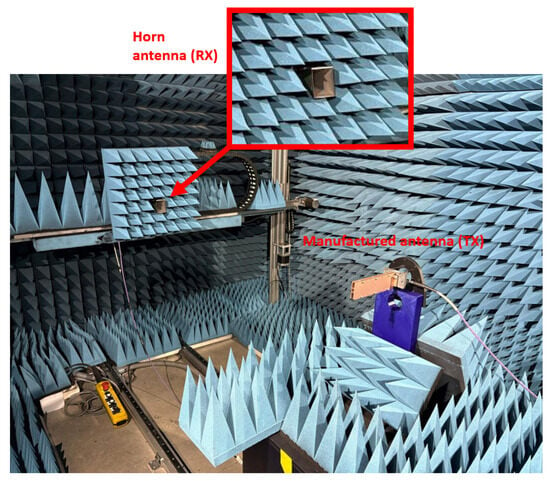

The experimental campaign took place in the anechoic chamber of the SWAT group of the University of Granada [39]. The leaky-wave antennas (Tx) were placed in a rotatory platform, which made a around a fixed horn antenna WR51 operating between 15–22 GHz. This horn antenna (Rx) collected the signals emitted from the leaky-wave antennas as they were rotating. A VNA is connected to the Tx and Rx antennas, introducing and recording the input and output signals, respectively. Figure 8 shows the leaky-wave antenna in the support, whereas Figure 9 illustrates a global vision of the whole experimental setup.

Figure 8.

Setup mounted in the anechoic chamber for obtaining the .

Figure 9.

Full view of the experimental setup.

In order to have a proper measurement process, a TRL (Thru–Reflect–Line) calibration [40] is first performed in the feeding horns. This allows for a better evaluation of the experimental -parameter. Notice that this setup is not prepared for the experimental measurement of the -parameter. For the experimental evaluation of the radiation patterns, the Tx and Rx antennas are conveniently aligned and placed at the same height. The distance between them is about m.

4.2. Experimental Results and Discussion

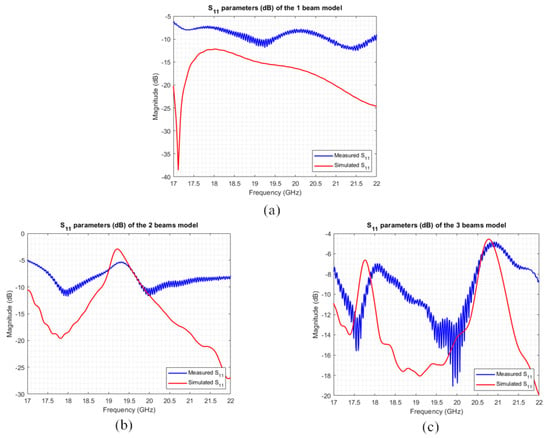

This section presents the experimental results, with the aim of testing the fully metallic, low-cost, and reconfigurable leaky-wave antenna in the laboratory. The first test consists of evaluating the scattering parameter of the leaky-wave antenna for the three different configurations. Figure 10a–c show a comparison between the simulated and experimental -parameter for the single-, double-, and triple-beam models, respectively. It is observed that although the trends of both curves are very similar in all cases and the trends are clearly followed, the experimental results are worse than expected, exhibiting values above −10 dB. This effect is mainly due to the low conductivity of the spray used for metalization of the pieces. Specifically, the low conductivity motivates the appearance of the skin-depth phenomenon, such that the field propagating inside the antenna progressively crosses the thin metal layer and may reach the dielectric part. The skin depth is evaluated according to [34]

where is the permeability of the metal layer. The parameter indicates the distance inside the metal coating from which the field has fallen by 37% approximately. At 17 GHz the value is 38.6 m. In order to avoid such a strong penetration, the metal-coating process needed several layers, achieved after several spray sessions.

Figure 10.

Comparison of measured and simulated S-parameters for the single-beam (a), dual-beam (b), and three-beam (c) leaky-wave antenna.

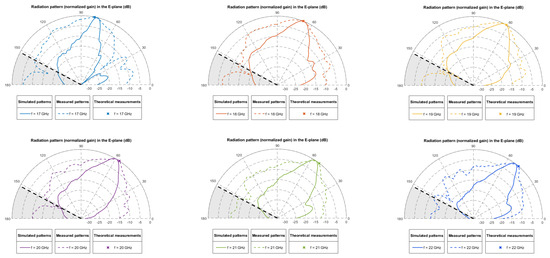

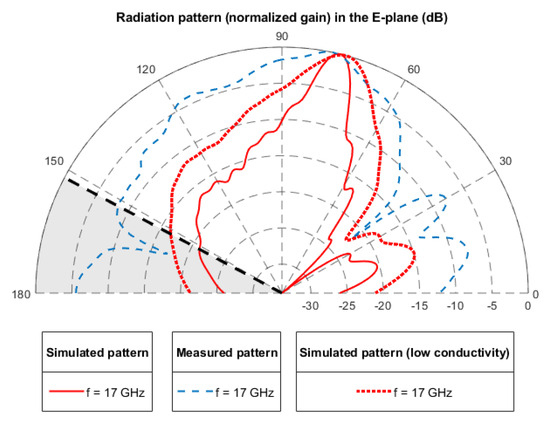

Despite the important constraints related to the metalization, the deterioration of the expected radiation diagrams was not so dramatic. Of course, the low conductivity leads to a substantial reduction in the quality factor of the antenna, manifesting as an increase in the beamwidth. But the pointing direction is respected, indicating that the main features of the leaky-wave antennas are still operative. Figure 11 shows the normalized gains obtained experimentally for the single-beam leaky-wave antenna in the range [17–22] GHz. In all cases, it has been compared with the simulated radiation patterns and the theoretical pointing angle.

Figure 11.

Normalized gain for the single-beam leaky-wave antenna: experimental measurements versus simulations and theoretical results. Frequency range from 17 to 22 GHz.

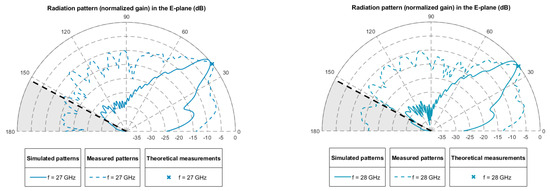

It can be seen that in the range analyzed, the pointing angles coincide (with an error of less than in the worst case) with those obtained in simulation. This demonstrates the validity of the theoretical study and the simulations carried out, as well as the correct design of the prototype that has been manufactured. This antenna has also been tested at higher frequencies, as shown in Figure 12. There, the radiation diagram obtained at 27–28 GHz is plotted. Again, the pointing directions between theoretical, simulated, and experimental results largely coincide, verifying the validity of the model even at these unexpected zone of the spectrum.

Figure 12.

Normalized gain for the single-beam leaky-wave antenna for 27–28 GHz. Experimental measurements versus simulations and theoretical results.

The widening of the beamwidth manifested in all radiation patterns is supposed to be due to the low-conductivity metallic coating. With the aim of testing this hypothesis, a simulation was performed by considering the leaky-wave antenna fabricated with a conductor having S/m. Figure 13 shows the radiation pattern at 17 GHz. Simulated results obtained in the ideal case (perfect conductor) and non-ideal case (low-conductivity conductor) are compared to those obtained experimentally. The widening of the radiation pattern is also manifested in simulations, thus reinforcing the assumption that low conductivity and wider beamwidth are correlated.

Figure 13.

Normalized gain for the single-beam leaky-wave antenna at 17 GHz, including the simulation of the ideal antenna, the simulation of the low-conductivity antenna, and the experimental results.

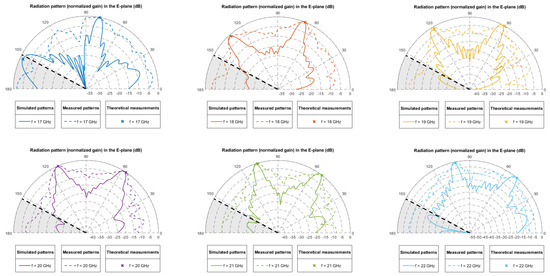

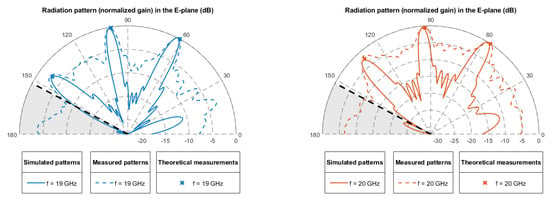

Results for the double-beam and triple-beam leaky-wave antenna are also obtained experimentally and plotted in Figure 14 and Figure 15, respectively. As can be checked, despite the low-quality factor of the antenna, the pointing directions mainly coincide in the range between 17 and 22 GHz. It is worth mentioning the case at 17 GHz. This is due to it falling into a shadow zone when performing the experimental measurement, as the measurement platform interferes with the receiving antenna. The rest of cases exhibit a good agreement.

Figure 14.

Normalized gain for the double-beam leaky-wave antenna: experimental measurements versus simulations and theoretical results. Frequency range from 17 to 22 GHz.

Figure 15.

Normalized gain for the triple-beam leaky-wave antenna: experimental measurements versus simulations and theoretical results. Frequencies between 19 and 20 GHz.

For the triple-beam leaky-wave antenna, analyzed in the 19–20 GHz frequency range, we observe how the three beams coincide with the theoretical and simulated pointing angles. Again, there exists an estimated error of less than less than between all the results included in the plot.

5. Conclusions

A low-cost, full-metal, and manually reconfigurable leaky-wave antenna is presented as a proof-of-concept intended to operate for 5G and future 6G applications. The design process is supported by the theoretical basis of waveguide and periodic-structure theory. Simple design rules are derived to easily design single-, double-, and triple-beam operation. The rules are tested by the design of the three prototypes, consisting of a fixed core formed by the transition and the guiding zone, and a reconfigurable part that allows for the interchange of the leakage sheet. Simulations in CST corroborates the theoretical predictions given by the design rules, as well as encourages the fabrication of the prototypes. The pieces were fabricated via stereolithography and subsequently metalized. In addition to the constraints related to the small conductivity of the metal, the experimental results are in agreement with the theoretical predictions, validating the proof-of-concept.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.D.-M., C.M. and M.B.-M.; Methodology, M.D.-M., C.M. and M.B.-M.; Software, M.D.-M.; Validation, M.D.-M., G.M.-G. and M.B.-M.; Formal analysis, M.D.-M.; Investigation, M.D.-M. and G.M.-G.; Data curation, G.M.-G. and M.B.-M.; Writing—original draft, M.D.-M., C.M., G.M.-G. and M.B.-M.; Visualization, G.M.-G. and M.B.-M.; Supervision, C.M.; Project administration, C.M.; Funding acquisition, C.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has been supported in part by PID2024-155167OA-I00 MI-CIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033/FEDER, UE, and in part by PID2020-112545RB-C45 funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by European Union NextGenerationEU/PTRT. It has also been supported by TED2021-131699B-I00 and PDC2023-145862-I00, funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by The European Union NextGenerationEU/PRTR. It has also been supported in part by Consejería de Universidad, Investigación e Innovación of Junta de Andalucía through grant EMERGIA 23-00235.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yang, P.; Xiao, Y.; Xiao, M.; Li, S. 6G Wireless Communications: Vision and Potential Techniques. IEEE Netw. 2019, 33, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chataut, R.; Nankya, M.; Akl, R. 6G Networks and the AI Revolution—Exploring Technologies, Applications, and Emerging Challenges. Sensors 2024, 24, 1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giordani, M.; Polese, M.; Mezzavilla, M.; Rangan, S.; Zorzi, M. Toward 6G Networks: Use Cases and Technologies. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2020, 58, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiky, M.N.A.; Rahman, M.E.; Uzzal, M.S.; Kabir, H.M.D. A Comprehensive Exploration of 6G Wireless Communication Technologies. Computers 2025, 14, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthaiou, M.; Yurduseven, O.; Ngo, H.Q.; Morales-Jimenez, D.; Cotton, S.L.; Fusco, V.F. The Road to 6G: Ten Physical Layer Challenges for Communications Engineers. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2021, 59, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanbakhsh Basherlou, H.; Ojaroudi Parchin, N.; See, C.H. Antenna Design and Optimization for 5G, 6G, and IoT. Sensors 2025, 25, 1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.J.; Guo, C.A.; Li, M.; Latva-aho, M. Antenna Technologies for 6G—Advances and Challenges. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2025. Early Access. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissanov, U.; Singh, G. 6G Broadband and High Directive Microstrip Antenna with SIW and FSSs. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2023, 5, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, D.; Malech, R.; Kennedy, W. The reflectarray antenna. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 1963, 11, 645–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javor, R.D.; Wu, X.; Chang, K. Beam steering of a microstrip flat reflectarray antenna. In Proceedings of the IEEE Antennas and Propagation Society International Symposium and URSI National Radio Science Meeting, Seattle, WA, USA, 20–24 June 1994; Volume 2, pp. 956–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomares-Caballero, Á.; Molero, C.; Padilla, P.; García-Vigueras, M.; Gillard, R. Wideband 3-D-Printed Metal-Only Reflectarray for Controlling Orthogonal Linear Polarizations. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2023, 71, 2247–2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayeri, P.; Elsherbeni, A.Z.; Yang, F. Radiation Analysis Approaches for Reflectarray Antennas [Antenna Designer’s Notebook]. IEEE Antennas Propag. Mag. 2013, 55, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mali, R.; Meshram, M.K. Design A 1Bit High Gain 21 × 21 Reconfigurable Reflectarray Antenna for X-Band Applications. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Microwaves, Antennas, and Propagation Conference (MAPCON), Bangalore, India, 12–16 December 2022; pp. 1398–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.I.; Loconsole, A.M.; Anelli, F.; Francione, V.V.; Khan, A.U.; Simone, M.; Sorbello, G.; Prudenzano, F. A Low-Profile Dual-Polarized Transmitarray with Enhanced Gain and Beam Steering at Ku Band. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 4656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Ren, W.; Li, W.; Xue, Z. A New 1 Bit Electronically Reconfigurable Transmitarray. Electronics 2024, 13, 1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worka, C.E.; Khan, F.A.; Ahmed, Q.Z.; Sureephong, P.; Alade, T. Reconfigurable Intelligent Surface (RIS)-Assisted Non-Terrestrial Network (NTN)-Based 6G Communications: A Contemporary Survey. Sensors 2024, 24, 6958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, F.; Olesen, K.; Ying, Z.; Fan, W. Experimental Over-the-Air Diagnosis of 1-Bit RIS Based on Complex Signal Measurements. IEEE Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 2024, 23, 3544–3548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, D.R.; Caloz, C.; Itoh, T. Leaky-Wave Antennas. Proc. IEEE 2012, 100, 2194–2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negri, E.; Fuscaldo, W.; Burghignoli, P.; Galli, A. An Overview of Design Techniques for Two-Dimensional Leaky-Wave Antennas. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstone, L.; Oliner, A. Leaky-wave antennas I: Rectangular waveguides. IRE Trans. Antennas Propag. 1959, 7, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Jackson, D.R.; Williams, J.T.; Yang, H.-Y.D.; Oliner, A.A. 2-D periodic leaky-wave antennas-part I: Metal patch design. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2005, 53, 3505–3514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Jackson, D.R.; Williams, J.T. 2-D periodic leaky-wave Antennas-part II: Slot design. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2005, 53, 3515–3524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, S.; Jackson, D.R.; Long, S.A. Propagation characteristics of leaky waves on a 2D periodic leaky-wave antenna. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE MTT-S International Microwave Symposium (IMS), Honololu, HI, USA, 4–9 June 2017; pp. 413–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, M.T.; Cheng, Y.J. Low-Sidelobe-Level Short Leaky-Wave Antenna Based on Single-Layer PCB-Based Substrate-Integrated Image Guide. IEEE Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 2018, 17, 1519–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Hong, W.; Tang, H.; Kuai, Z.; Wu, K. Half-Mode Substrate Integrated Waveguide (HMSIW) Leaky-Wave Antenna for Millimeter-Wave Applications. IEEE Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 2008, 7, 85–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araghi, A.; Khalily, M.; Tafazolli, R. Long Slot Dielectric-Loaded Periodic Leaky-Wave Antenna Based on 3D Printing Technology. In Proceedings of the 2024 18th European Conference on Antennas and Propagation (EuCAP), Glasgow, UK, 17–22 March 2024; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iftekar, S.F.; Aabid, A.; Amir, A.; Baig, M. Advancements and Limitations in 3D Printing Materials and Technologies: A Critical Review. Polymers 2023, 15, 2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biedma-Pérez, A.; Pérez-Escribano, M.; Parellada-Serrano, I.; Palomares-Caballero, Á.; Padilla, P.; García-Vigueras, M.; Molero, C. Metal-Only 3-D Unit Cell for Reflectarrays with Independent Dual-Band Operation. IEEE Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 2025, 24, 1824–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, C.M.; Menargues, E.; García-Vigueras, M. All-Metal 3-D Frequency-Selective Surface with Versatile Dual-Band Polarization Conversion. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2020, 68, 5431–5441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balmaseda-Márquez, M.A.; Valerio, G.; Padilla, P.; Palomares-Caballero, Á.; Valenzuela-Valdés, J.F.; Molero, C. Modeling Partially-Dielectric Unit Cells for OAM Transmitarrays. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 110840–110849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-González, L.; Rico-Fernández, J.; Vaquero, Á.F.; Arrebola, M. Millimeter-Wave Lightweight 3D-Printed 4 × 1 Aluminum Array Antenna. In Proceedings of the 2022 16th European Conference on Antennas and Propagation (EuCAP), Madrid, Spain, 27 March–1 April 2022; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco, J.; Parellada-Serrano, I.; Molero, C. Fully Metallic Reflectarray for the Ku-Band Based on a 3D Architecture. Electronics 2021, 10, 2648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Olivares, P.; Ferreras, M.; Garcia-Marin, E.; Polo-López, L.; Tamayo-Dominguez, A.; Córcoles, J.; Grajal, J. Manufacturing Guidelines for W-Band Full-Metal Waveguide Devices: Selecting the most appropriate technology. IEEE Antennas Propag. Mag. 2023, 65, 48–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozar, D.M. Microwave Engineering, 4th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bilel, H.; Taoufik, A. Floquet Spectral Almost-Periodic Modulation of Massive Finite and Infinite Strongly Coupled Arrays: Dense-Massive-MIMO, Intelligent-Surfaces, 5G, and 6G Applications. Electronics 2022, 11, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://formlabs.com/es/3d-printers/form-3 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Liu, Z.; Lu, H.; Liu, J.; Yang, S.; Liu, Y.; Lv, X. Compact Fully Metallic Millimeter-Wave Waveguide-Fed Periodic Leaky-Wave Antenna Based on Corrugated Parallel-Plate Waveguides. IEEE Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 2020, 19, 806–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://uk.rs-online.com/web/p/shielding-aerosols/2474251? (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Available online: https://swat.ugr.es/facilities-gear/ (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Palomares-Caballero, Á.; Pérez-Escribano, M.; Molero, C.; Padilla, P.; García-Vigueras, M.; Gillard, R. Broadband 1-bit Reconfigurable Intelligent Surface at Millimeter Waves: Overcoming P-I-N -Diode Degradation with Slotline Ring Topology. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2025, 73, 5433–5445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).