Abstract

In modern high-performance computing (HPC) and large-scale data processing environments, the efficient utilization and scalability of memory resources are critical determinants of overall system performance. Architectures such as non-uniform memory access (NUMA) and tiered memory systems frequently suffer performance degradation due to remote accesses stemming from shared data among multiple tasks. This paper proposes LACX, a shared data migration technique leveraging Compute Express Link (CXL), to address these challenges. LACX preserves the migration cycle of automatic NUMA balancing (AutoNUMA) while identifying shared data characteristics and migrating such data to CXL memory instead of DRAM, thereby maximizing DRAM locality. The proposed method utilizes existing kernel structures and data to efficiently identify and manage shared data without incurring additional overhead, and it effectively avoids conflicts with AutoNUMA policies. Evaluation results demonstrate that, although remote accesses to shared data can degrade performance in low-tier memory scenarios, LACX significantly improves overall memory bandwidth utilization and system performance in high-tier memory and memory-intensive workload environments by distributing DRAM bandwidth. This work presents a practical, lightweight approach to shared data management in tiered memory environments and highlights new directions for next-generation memory management policies.

1. Introduction

In modern data centers and high-performance computing (HPC) environments, memory demand continues to escalate due to memory-intensive workloads such as artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning, and large-scale data analytics. This trend not only pushes system memory capacity to its limits but also exposes critical bottlenecks in memory bandwidth utilization [1,2]. Although multi-core CPUs provide high computational throughput through parallelism, bursts of concurrent memory accesses can saturate DRAM bandwidth, leading to severe system performance degradation. These bandwidth bottlenecks are particularly detrimental in real-time analytics, transactional systems, and massively parallel computations, where predictable latency and throughput are essential.

To overcome the limitations of memory capacity and bandwidth, various techniques have been explored over the past decade. Prior research has proposed tiered memory structures such as NUMA-aware placement strategies [3,4,5,6], high-bandwidth memories (e.g., HBM [7]), and memory compression schemes [8]. These methods combine fast yet capacity-limited DRAM as high-tier memory with slower but larger-capacity devices as low-tier memory, aiming for cost-effective scalability. While these techniques have achieved partial success, they face limitations in universality and scalability due to hardware complexity, cost, and non-portable optimizations. In particular, relying solely on DRAM expansion cannot simultaneously satisfy the capacity and bandwidth demands of modern heterogeneous workloads [1].

Recently, Compute Express Link (CXL) has emerged as a promising interconnect technology to bridge this gap [9,10,11]. CXL enables high-speed, low-latency communication between CPUs and memory devices, allowing a dynamic expansion of system memory beyond the constraints of traditional architectures. Through the flexible attachment of diverse memory types, CXL facilitates the construction of software-managed tiered memory systems that can adaptively allocate resources according to workload characteristics. Importantly, CXL offers a pathway for efficiently managing shared data placement and access across nodes, a challenge that conventional NUMA and AutoNUMA approaches do not explicitly address [12,13].

Furthermore, the proposed LACX framework can also provide potential benefits in emerging computing paradigms such as in-memory computing (IMC) based on non-volatile memory (NVM) technologies. In IMC environments, computation and storage are tightly coupled, and efficient data locality management becomes essential for maintaining both performance and energy efficiency. Since shared data management remains a key challenge in IMC systems where multiple processing units may concurrently access the same NVM regions, the shared page-aware design of LACX could be extended to mitigate data contention and optimize bandwidth utilization. This alignment with NVM-based IMC directions highlights the adaptability of LACX to next-generation memory-centric architectures [14,15].

Despite advances in tiered memory and automatic page migration, a fundamental limitation remains: existing systems primarily base migration decisions on access frequency (data “hotness”) without distinguishing whether the accessed pages are shared among multiple tasks [16,17,18]. As a result, shared data—often a major contributor to remote access contention and bandwidth pressure—tends to remain fixed on a particular node or is conservatively excluded from migration. This oversight leads to suboptimal bandwidth utilization and unpredictable performance in NUMA and heterogeneous memory environments.

To address this problem, this work proposes LACX, a Linux kernel mechanism designed to identify and manage shared data pages explicitly in CXL-extended memory systems. LACX introduces a shared page-aware migration policy that relocates shared data to CXL nodes, while keeping node-local hot data in DRAM. This design mitigates bandwidth contention and improves effective memory utilization across heterogeneous tiers. By operating at the kernel level, LACX leverages intrinsic memory tracking structures to minimize overhead and maintain compatibility with the existing AutoNUMA framework.

LACX makes the following key contributions:

- 1.

- Low-overhead shared page-aware migration: It implements an efficient shared-page recognition and migration mechanism that reuses existing NUMA structures, adding minimal overhead and preserving AutoNUMA’s scanning cycle.

- 2.

- Seamless integration and stability: LACX cooperates with AutoNUMA’s placement policies to prevent migration conflicts, ensuring stability across diverse and dynamic workloads.

- 3.

- Balanced bandwidth utilization: By distributing local and shared data between DRAM and CXL memory, LACX achieves more balanced bandwidth usage, alleviating DRAM saturation and improving system throughput.

Through these contributions, LACX addresses a major gap in current memory management research—the lack of shared data-oriented optimization in heterogeneous memory systems. The proposed approach demonstrates that operating systems can efficiently coordinate DRAM and CXL tiers to achieve scalable bandwidth utilization and predictable performance in next-generation data centers and HPC platforms.

2. Background and Related Work

This section describes the theoretical background of our research, covering the principles and latest research trends in NUMA architecture, tiered memory, and next-generation memory interconnect technologies such as CXL [3,6,9,10]. Based on this discussion, we analyze how the LACX technique proposed in this paper differs from existing approaches.

2.1. NUMA and AutoNUMA

The NUMA architecture [19] divides a system into multiple nodes, each consisting of physically coupled CPUs and memory. When a CPU accesses memory within its own node (local memory), it achieves the highest speed, whereas accessing memory in other nodes (remote memory) incurs longer latency. As a result, it is crucial for the operating system to ensure that CPUs access memory as locally as possible, minimizing remote accesses and maximizing local accesses to reduce bottlenecks and latency [3,4].

Linux has officially supported the AutoNUMA feature since kernel version 3.8 for automatic optimization in NUMA systems. AutoNUMA automatically migrates pages and tasks to minimize the distance between them. Specifically, it triggers NUMA, hinting faults to intentionally induce page faults, thereby identifying the locations of CPUs that recently accessed the page and the node where the page is allocated [16,19].

Existing NUMA optimization research has primarily focused on improving page access locality. As a representative example, AutoNUMA, which was introduced earlier, is not without its limitations [5,16]. Excessive page migration can degrade performance, and the migration process itself can introduce additional overhead due to conflicts with the CPU load balancer, increased translation lookaside buffer (TLB) misses, and page table walks. In particular, frequent TLB misses can cause significant delays if the page table is located on a remote node. Furthermore, when all CPUs attempt to optimize local accesses, memory controllers on certain nodes may become overloaded, resulting in local access latencies that exceed those of remote accesses.

Notably, AutoNUMA primarily focuses on optimizing memory access locality for individual tasks and is less effective in handling shared data accessed by multiple tasks [5,6]. Since AutoNUMA performs migration based only on page-level locality, it is difficult to achieve clear locality benefits by migrating pages containing shared data to any particular node. Consequently, AutoNUMA tends to handle shared data conservatively or even avoid migrating it altogether. These limitations remain as important challenges for future NUMA optimization research.

To overcome these limitations, this paper proposes LACX, a novel mechanism that actively identifies and manages shared data across tasks. While AutoNUMA avoids migrating shared pages to prevent performance degradation, LACX leverages the same hinting-fault mechanism to detect frequently shared pages and strategically isolate them in dedicated memory nodes, thereby improving locality for private data and reducing contention around shared memory.

2.2. Tiered Memory

In tiered memory systems, DRAM serves as the high-speed, high-bandwidth high-tier memory, while non-volatile memory (NVM) or other extension memory technologies, which offer larger capacity and cost efficiency, act as low-tier memory. Low-tier memory is connected to the system via high-speed interfaces such as PCIe; NVM technologies like Optane are representative examples [20,21]. These low tiers are critical for transaction-based services requiring large capacity and data integrity.

The primary strategy in tiered memory involves analyzing workloads’ memory access patterns to place data in appropriate tiers based on access frequency (hotness). Ideally, frequently accessed (hot) data should reside in high-tier memory, while less frequently accessed (cold) data should be allocated to low-tier memory. Automated techniques that migrate data from low-tier to high-tier when frequently accessed are widely used, and ongoing research aims to improve their efficiency [12,17].

Prior work such as Transparent Page Placement (TPP) [17] focuses on identifying hot and cold pages at the OS level and proactively demotes cold pages from high to low tiers via lightweight mechanisms. These approaches improve throughput and reduce overhead in data center workloads by ensuring that high-tier memory is mainly occupied by frequently accessed pages. However, hotness-based methods can be sensitive to rapid changes in access patterns and may incur a high migration overhead.

More recent schemes like Colloid [22] aim to balance effective access latency across tiers rather than solely relying on access frequency. Despite reducing some shortcomings of hotness-based methods, they still struggle to manage pages accessed concurrently by multiple tasks, limiting their effectiveness for shared data.

Recent work [23] shows that access frequency alone does not always indicate performance-critical data. They introduce Amortized Offcore Latency (AOL), a metric capturing the true impact of memory accesses by considering both latency and memory-level parallelism. Using AOL, they propose allocation (SOAR) and migration (ALTO) policies that significantly outperform traditional hotness-based mechanisms across diverse workloads.

Building upon these insights, LACX explicitly targets shared data in tiered memory environments with CXL. By offloading shared pages to CXL nodes, LACX reduces contention on DRAM and preserves DRAM capacity for latency-sensitive private data. Unlike device-side techniques such as HeteroMem [11], which rely on hardware-managed page promotions, LACX uses a host-side NUMA fault-based mechanism to efficiently manage data placement with minimal overhead, enhancing memory bandwidth scalability in multi-threaded workloads.

2.3. CXL

CXL has emerged as an effective solution for overcoming the capacity limitations of traditional memory in server and data center environments with high memory demands [9,10]. CXL provides high bandwidth by leveraging the PCIe 5.0 interface and enables the construction of heterogeneous memory pools through the cxl.mem protocol. From the perspective of the host CPU, CXL devices are recognized as independent NUMA nodes, ensuring compatibility with existing NUMA-based memory management techniques [12,13].

However, CXL exhibits inherent performance differences compared to high-tier memory (DRAM). CXL is classified as a lower-priority, low-tier memory and shows marked differences from high-tier memory in terms of access latency and bandwidth. This performance heterogeneity makes the limitations of traditional NUMA policies evident even when CXL devices are recognized as NUMA nodes [22]. While existing NUMA policies determine memory placement based on a single distance metric between memory domains, heterogeneous memory environments such as those using CXL require consideration of multiple performance metrics, including latency, bandwidth, and capacity [21,24].

Accordingly, when conventional NUMA policies—which focus primarily on access distance—are applied directly to CXL-based systems, they fail to adequately account for performance heterogeneity, potentially leading to inefficient tiered memory. This can prevent the system from achieving the expected performance improvements or even result in performance degradation. Moreover, improper migrations may increase overhead and reduce overall system performance.

In response, LACX incorporates CXL as a strategic target for shared data placement. Rather than attempting to maintain DRAM locality for all pages, LACX isolates highly contended shared data into CXL nodes. This allows DRAM to be reserved for private pages that are latency-sensitive, while shared data benefits from increased aggregate bandwidth via off-node access. This architectural distinction enables LACX to both respect the constraints of performance heterogeneity in CXL and actively utilize it to mitigate NUMA contention.

3. Design

This section details the design of LACX, focusing on its core functionalities for identifying shared data and migrating it to CXL nodes. LACX operates at the page level, which is the fundamental unit of memory migration in the Linux kernel. Therefore, in the following discussion, shared data is referred to as a “shared page” from an implementation perspective.

3.1. Approach

In environments where system memory resources are intensively utilized, data sharing among different processes and threads becomes increasingly common. As a result, remote memory accesses between nodes frequently occur in NUMA systems, which is a major cause of overall system performance degradation [3,16]. The Linux kernel’s AutoNUMA identifies and distinguishes pages that experience shared access, known as shared fault pages. However, it employs a conservative policy that keeps these pages on the node where they were first accessed, rather than distributing or relocating them [16]. This approach induces repeated remote accesses to shared pages, further exacerbating bottlenecks in NUMA systems.

In tiered memory environments, if the system has sufficient free memory, some shared data remaining in high-tier memory does not pose a significant problem [12,17]. However, when multiple workloads run concurrently or a single workload consumes large amounts of memory, high-tier memory quickly becomes saturated. In such cases, if shared data still occupies certain portions of high-tier memory, it leads to inefficient utilization and a decline in overall memory performance [22].

To address these issues, this paper focuses on populating high-tier memory with pages that are highly likely to be accessed locally. Instead of analyzing the locality of each individual page access, our approach determines the sharing status of pages and leverages this information for placement decisions [4,5]. By focusing on whether a page is shared among multiple tasks or primarily accessed by a single local task, we ensure that high-tier memory is predominantly occupied by pages with strong locality to the local node.

Therefore, our approach designates shared data as the primary target for migration to CXL nodes, leveraging the advantages that CXL provides [9,10]. By migrating shared pages, LACX maximizes the utilization of high-tier memory for local accesses, thereby amplifying the performance benefits and enabling more efficient maintenance of overall system performance.

3.2. Shared Fault

AutoNUMA aims to reduce latency by migrating pages to appropriate NUMA nodes based on memory access patterns [16]. However, incorrect migrations can introduce overhead and degrade overall system performance. To prevent such issues, AutoNUMA interprets hinting faults in two categories.

The first category is local fault and remote fault. These are determined by whether the page resides on the same physical node as the CPU core where the current task is executing. If the page is located on the current task’s node, a local fault occurs; otherwise, a remote fault occurs [16].

The second category is private fault and shared fault. These are determined by whether the current accessing task is the same as the previous task that accessed the page. If the same task accesses the page, it is classified as a private fault; if a different task accesses the page, it is classified as a shared fault [16]. When a shared fault occurs, AutoNUMA recognizes the page as a shared page.

AutoNUMA combines these two categories to determine whether to migrate a page. For example, if a remote fault and a private fault occur together on a page primarily used by a specific task, it indicates that the task is accessing its main pages remotely. In this case, AutoNUMA migrates the task to the node where the page is located [16].

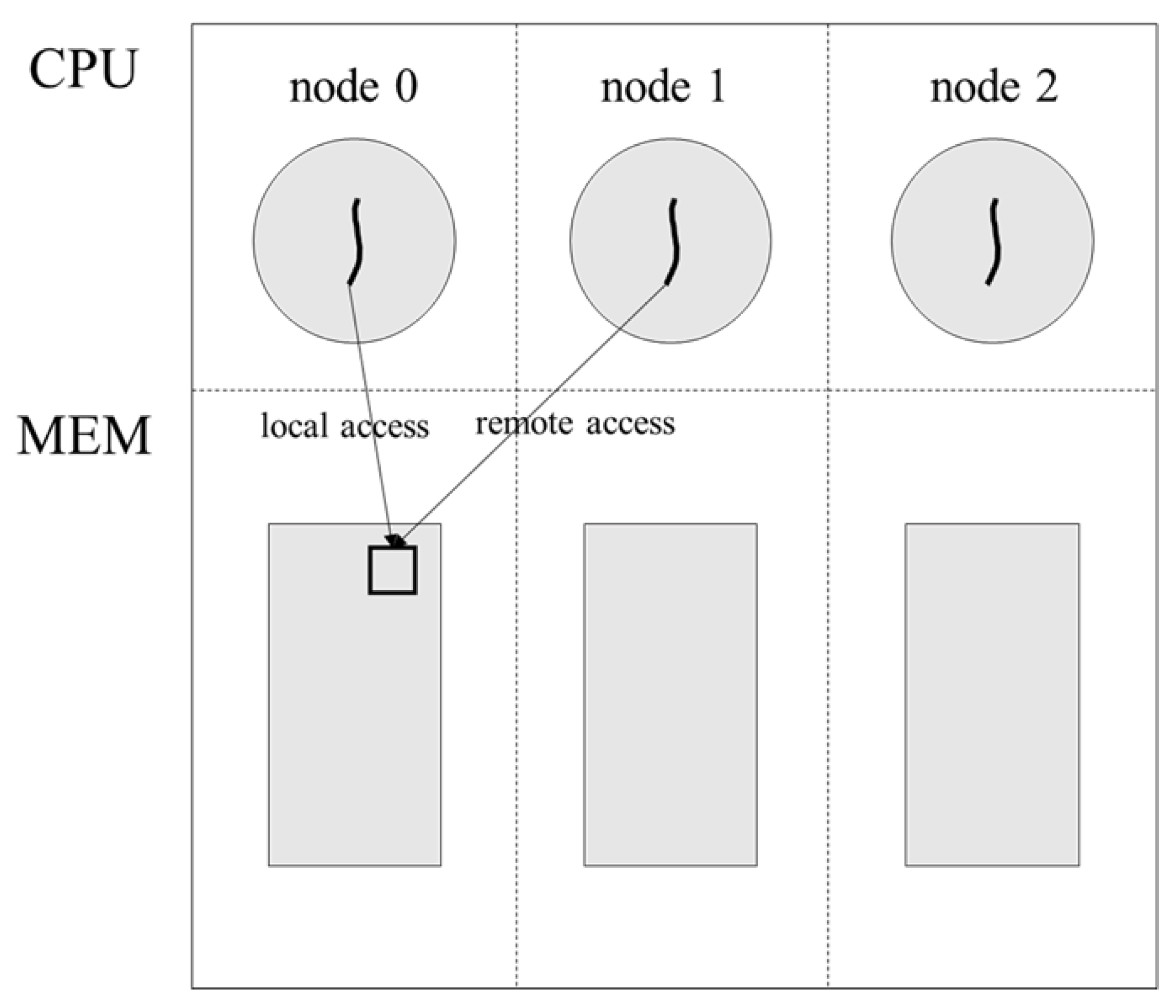

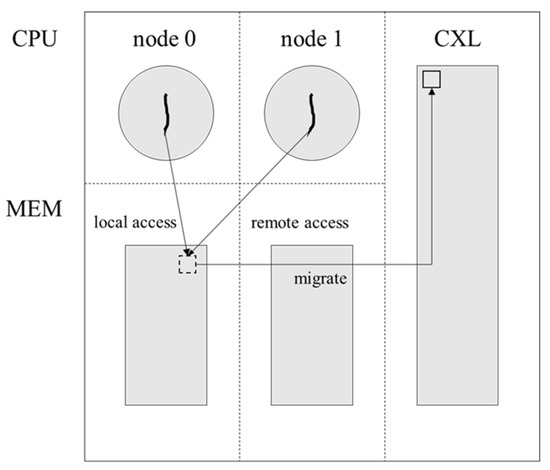

However, the situation is different when a shared fault occurs. A shared fault arises when different tasks access the same page, and in this case, migration cannot ultimately avoid remote access [16]. Figure 1 shows how page access varies depending on the page location when a shared fault occurs. Assuming there are three NUMA nodes, if two tasks are located on separate nodes and the page is located on a third node, both tasks will access the page remotely. If the page is located on one of the tasks’ nodes, the other task will still access the page remotely. In other words, if a shared fault occurs among tasks on different nodes, at least one task will always incur a remote access. As a result, AutoNUMA generally avoids migrating pages on which shared faults have occurred.

Figure 1.

Shared fault based on page location.

While AutoNUMA’s conservative policy for shared data—retaining pages that incur at least one remote access in high-tier memory—is rational given the inevitability of remote accesses, it does not constitute an efficient use of high-tier memory resources [6,16]. By keeping shared pages in high-tier memory, AutoNUMA allows these pages to occupy valuable space that could otherwise be allocated to data with high local access frequency, thereby limiting the overall efficiency of memory utilization. This can lead to performance degradation as memory usage increases, especially in workloads where multiple threads share memory.

In contrast, LACX adopts a proactive strategy that explicitly migrates shared data to low-tier memory (CXL), reserving high-tier memory for data with strong local access patterns [17,22]. This approach not only prevents the wasteful allocation of high-tier memory to shared pages but also maximizes the benefits of tiered memory improved locality for private data and expanded bandwidth for the system as a whole. As a result, LACX enables more effective utilization of high-tier memory and better accommodates the demands of memory-intensive, multi-threaded workloads.

3.3. Shared Data and Migration

The existing AutoNUMA shared fault classification mechanism is designed to minimize performance loss caused by incorrect migrations [16]. To achieve this, AutoNUMA checks for conditions that make migration unsuitable and only migrates pages that do not meet any of these exclusion criteria. As a result, AutoNUMA marks pages shared among different tasks as unsuitable for migration. For example, pages such as memory-mapped (mmap) file pages and anonymous shared memory pages are excluded from migration. However, since these pages are often accessed by tasks on multiple nodes, LACX actively identifies and considers such shared pages as migration candidates.

LACX identifies shared pages based on information already present in existing Linux kernel data structures. Specifically, it utilizes three types of information: (1) the tasks that have accessed the page, (2) the NUMA nodes where the page and tasks are located, and (3) the identifier of the most recent task to access the page. Using these, LACX determines whether a page is shared among tasks on multiple nodes. The specific pseudo code for shared page identification can be found in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1: Pseudo code for is_shared_page |

|

Shared pages identified through Algorithm 1 are subsequently considered as migration candidates. The actual migration is performed within the do_numa_page() function, which is responsible for making migration decisions in AutoNUMA [16]. During this function, LACX adopts the existing page migration mechanism of AutoNUMA but specifically identifies shared pages and permits their migration, explicitly fixing the target location to the CXL node [17]. Migration is performed only after precondition checks and resource verification to minimize bottlenecks. If migration fails, the page remains on its original node instead of being moved to the CXL node. This approach precisely identifies shared pages and promotes their migration to CXL nodes, thereby mitigating conflicts and imbalances in high-tier memory and improving the overall memory utilization efficiency of the system.

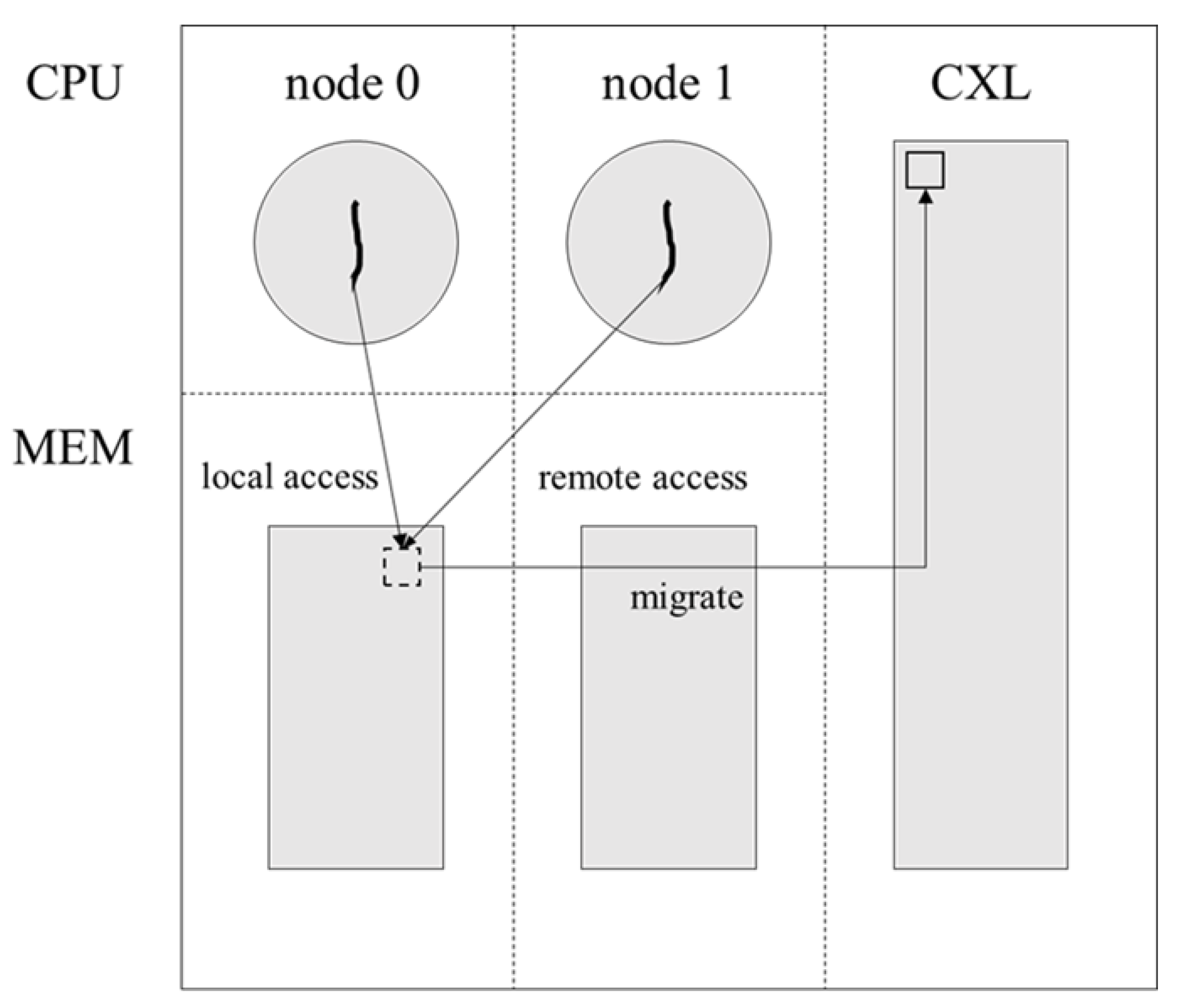

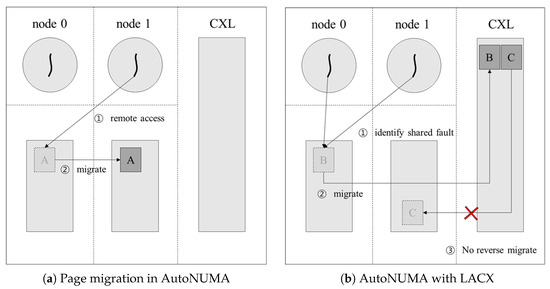

Figure 2 shows the process by which LACX identifies shared pages and migrates them to CXL. Migrating shared pages to CXL nodes may result in remote accesses, raising potential concerns about performance degradation. However, this migration increases the available space in high-tier memory so that it can be more effectively filled with pages exhibiting local access frequency [22]. This improves overall memory access efficiency and ultimately contributes to enhanced system performance.

Figure 2.

Identify shared data and migrate to CXL.

3.4. Avoiding Overhead

Although more effective identification of shared pages improves accuracy, determining the sharing status of all pages can introduce significant overhead [5,21]. Most existing tiered memory techniques employ monitoring and decision mechanisms for the precise measurement of page access frequency (hotness), which have been noted as significant sources of performance overhead. To address this, our approach identifies the sharing status of pages within the existing AutoNUMA scan cycle, rather than relying on additional sampling-based mechanisms or hardware-based performance monitoring tools [16]. This enables the detection of shared data without introducing extra overhead. Furthermore, to minimize the overhead associated with migrating shared pages to CXL nodes, our implementation maximizes the use of existing kernel functions and data structures [16]. This strategy ensures that high-tier memory remains populated primarily by pages with a high probability of local access, while avoiding additional memory consumption, thereby maintaining memory access efficiency and overall system performance.

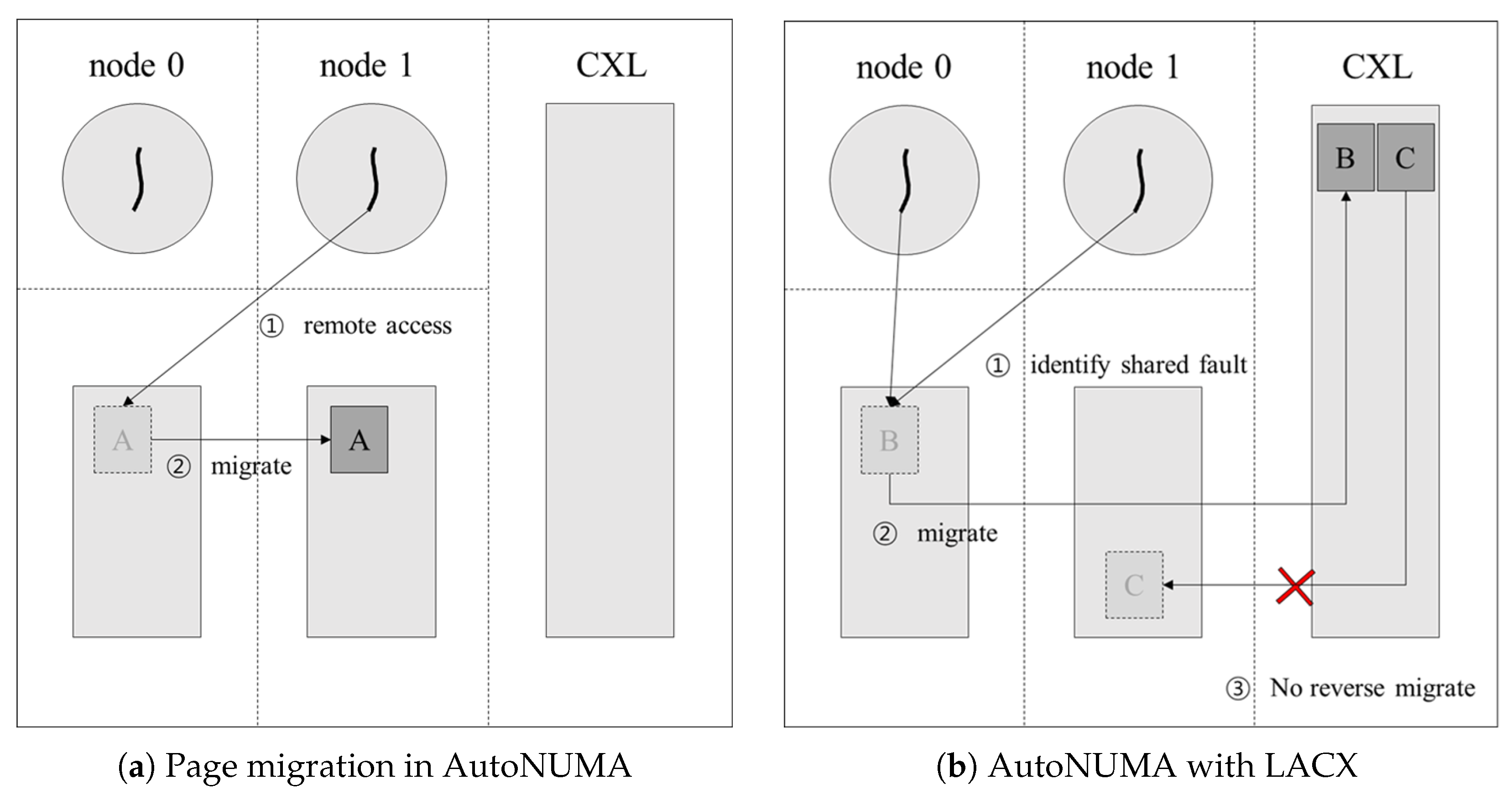

3.5. Avoiding Collision with AutoNUMA

When shared pages are migrated to CXL nodes, AutoNUMA may misinterpret these pages as being placed in incorrect locations. Figure 3a shows the default behavior of AutoNUMA [16]. By default, AutoNUMA follows a policy of preferentially placing data in high-tier memory. In contrast, Figure 3b demonstrates how LACX identifies shared pages and migrates them to CXL nodes. In this figure, page B is a shared page accessed by CPUs on both node 0 and node 1 and is identified by LACX as such and migrated to a CXL node. Page C is also migrated to a CXL node by LACX, but AutoNUMA mistakenly considers it to be in an incorrect location and attempts to migrate it back to its original node. When a shared page resides in high-tier memory, AutoNUMA generally does not migrate it, since it is considered to belong to the high-tier regardless of its specific node. However, if a shared page is located in a lower-priority node such as CXL, AutoNUMA regards it as being in an “abnormal location” and tries to migrate it back to a high-tier node. To prevent such unnecessary reverse migrations, LACX marks pages that are identified as shared and migrated to CXL nodes. This ensures that these pages are excluded from AutoNUMA’s migration priority list, effectively avoiding conflicts between the two policies [16].

Figure 3.

Overview of AutoNUMA and LACX.

4. Evaluation

This section assesses the performance of LACX by examining its approach of identifying shared data and migrating it to CXL nodes, using experimental results from both single-workload and multi-workload scenarios to analyze the impact of memory usage.

4.1. Environment

The experimental machine is equipped with eight sockets, a total of 192 cores (24 cores per socket), and 512 GB of memory (64 GB per node). To simulate a CXL environment, virtual machines were employed. Table 1 shows the system configuration. Among the eight NUMA nodes, three were utilized for experiments. Specifically, two NUMA nodes (each with 24 CPU cores and 18 GB DDR4-3200 memory) and one CPU-less 18 GB DDR4-3200 memory node were configured. To emulate the memory latency characteristics of CXL, the CPU-less memory node was assigned a higher NUMA distance [10,12]. Throughout this paper, the experimental nodes are referred to as follows: the two nodes with both CPU and memory (nodes 0 and 1) are designated as high-tier nodes, and the CPU-less memory-only node (node 2) is referred to as the CXL node.

Table 1.

System configuration.

Table 2 summarizes the per-node memory access latency according to NUMA distance. The rows represent the requesting nodes, and the columns denote the target memory nodes. The memory access latency for high-tier nodes (node 0 → node 0, node 1 → node 1) is the lowest, at 151.5 ns and 152.0 ns, respectively. In contrast, remote accesses between different high-tier nodes (node 0 → node 1, node 1 → node 0) range from 394.1 ns to 400.4 ns, approximately 2.6 times higher. Notably, accesses from high-tier nodes to the CXL node exhibit the highest latency, ranging from 454.8 ns to 456.6 ns, which exceeds even the inter-node latency between high-tier nodes. These latency characteristics closely mirror the performance differences observed in real CXL-based tiered memory environments, where CXL access latency typically falls in the range of 400–500 ns [10,12]. In this study, we configured the evaluation environment by assigning a high NUMA distance to a CPU-less node to emulate the latency behavior of a CXL tier. This approach follows the same methodology validated by previous studies [17,22] and aims not at reproducing absolute physical performance but at analyzing the relative performance trends of data migration between DRAM and CXL memory. Therefore, the results obtained under this setup effectively illustrate how the proposed policy alleviates bandwidth pressure on high-tier memory and enables balanced utilization of the entire system bandwidth, which remains valid even in real CXL-based environments.

Table 2.

Per-node memory access latency of experimental system (unit: ns). (Requesting: node in rows, target memory node in columns).

Experiments were conducted by comparing the performance of the Linux kernel 6.8.0 with LACX implemented and the standard kernel of the same version. To effectively identify shared data and validate CXL migration, we used SHM-bench [25], a microbenchmark designed for this purpose. SHM-bench accepts the shared memory size and the number of threads as arguments, and the generated threads are distributed across all nodes to perform sequential read and write operations on the shared memory, thereby inducing intentional shared faults. For real-world workloads, we employed yahoo! cloud serving benchmark (YCSB) [26], which is widely used for key-value store performance evaluation, and the mg.D workload from NASA parallel benchmarks (NPB) [27].

The evaluation aims to answer the following key questions:

- 1.

- Can shared data be accurately identified and migrated?This evaluation quantitatively assesses how accurately LACX can detect shared data and how effectively it can migrate such data to the CXL node. In particular, the precision of shared data detection and the appropriateness of migration are analyzed in detail according to workload characteristics and access patterns.

- 2.

- How does the migration policy impact system performance?To evaluate the impact of shared data migration on system performance, we measured overall performance changes under both single- and multi-workload scenarios. Specifically, we closely analyzed how migration overhead and the latency of accessing low-tier nodes affect workload execution time and resource efficiency. This allows us to verify whether LACX’s policy contributes to real-world performance improvements.

- 3.

- How does LACX affect memory tier utilization and bandwidth usage?By analyzing changes in data distribution between high-tier nodes and CXL nodes as well as bandwidth utilization patterns, we assess how LACX influences the balance and efficiency of the entire memory hierarchy. In particular, we focus on the bandwidth usage of high-tier nodes and CXL nodes according to overall system memory utilization.

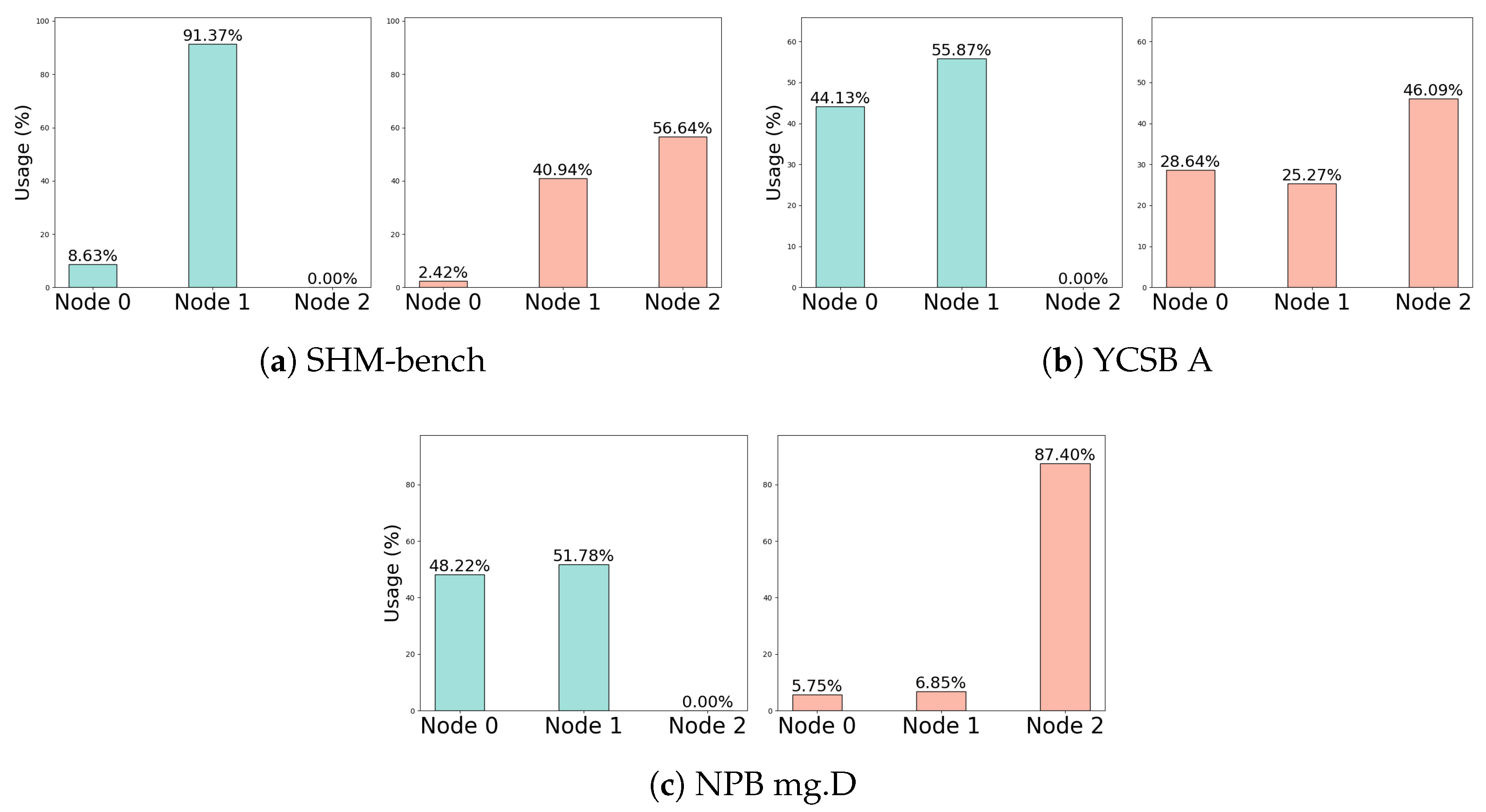

4.2. Distinction and Migration of Shared Data

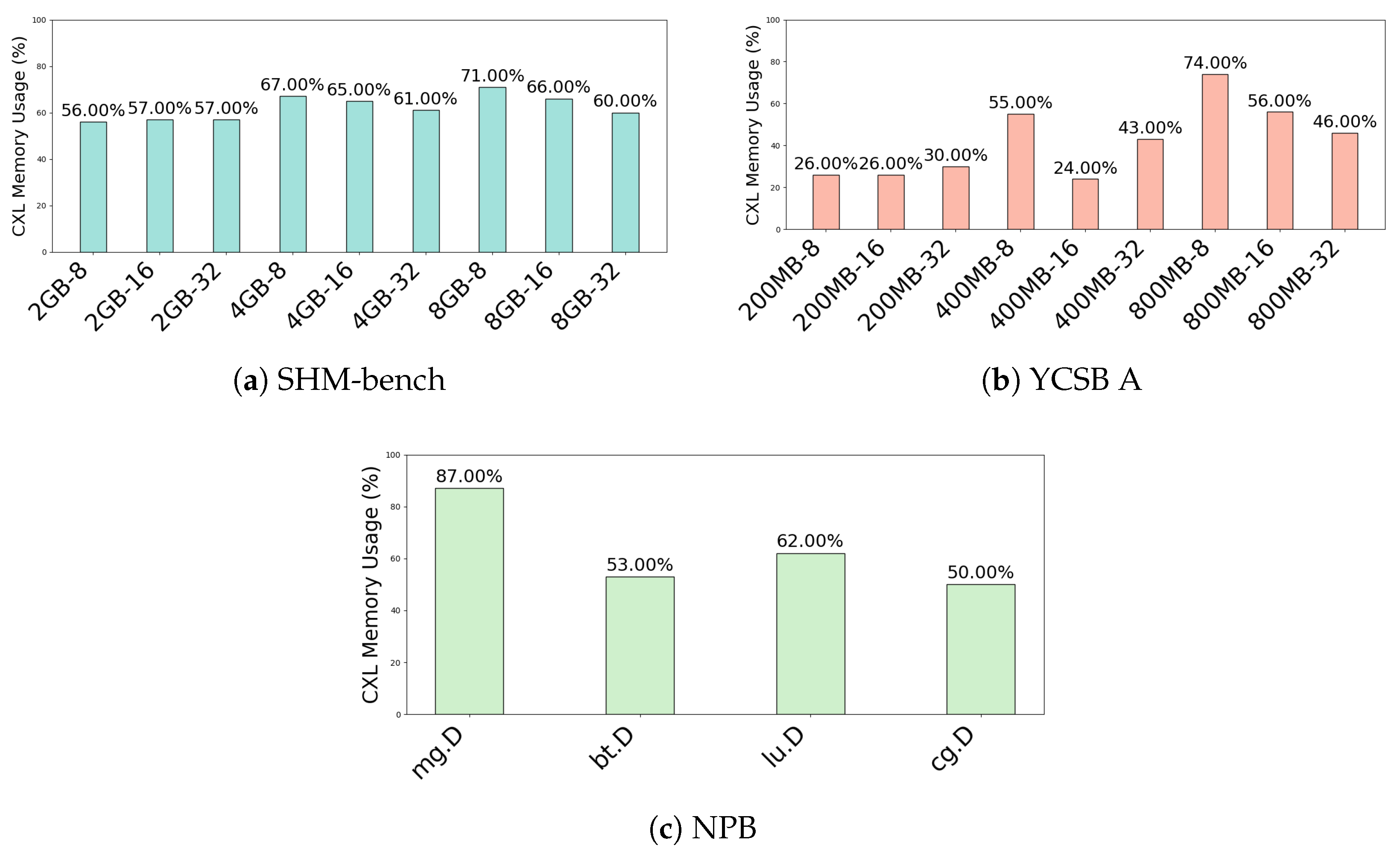

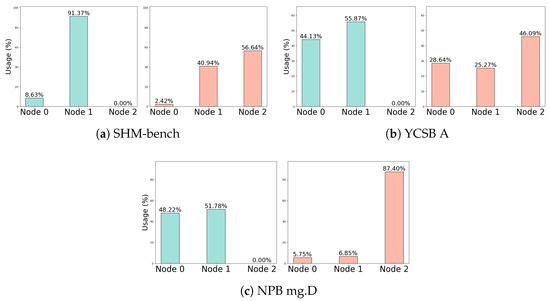

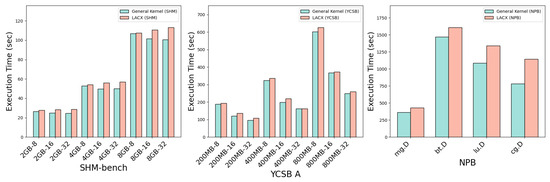

To quantitatively evaluate whether LACX can effectively identify shared data and accurately migrate it to CXL nodes, we used SHM-bench, YCSB A, and NPB workloads. Figure 4 compares the per-node memory usage ratios between the standard kernel and LACX environments for each workload. The x-axis represents the NUMA node number, and the y-axis indicates the proportion of total memory allocated to each node.

Figure 4.

Comparison of memory usage for each node in a general kernel and LACX.

Figure 4a shows the results for SHM-bench, where 32 threads operate on a 2 GB shared memory segment. Under the standard kernel, most memory is allocated to the high-tier nodes with CPUs, and no memory is allocated to the CXL node. This is because the standard kernel deprioritizes allocation to the CXL node to avoid remote accesses that could degrade performance. In contrast, LACX migrates approximately 56.64% of the total memory used by SHM-bench to the CXL node, demonstrating its ability to effectively identify and migrate pages shared by many threads. Figure 4b shows the results for the YCSB A workload, where 32 threads operate on a 800 MB record. Although YCSB A is a real-world, unstructured workload, it exhibits patterns where multiple threads reference common data during execution. Accordingly, LACX migrates about 46.09% of the total memory to the CXL node. Figure 4c shows the results for NPB mg.D, a numerically intensive parallel workload in which many processes repeatedly access a global matrix structure. As a result, LACX migrates 87% of the total memory to the CXL node, the highest migration ratio among the three workloads.

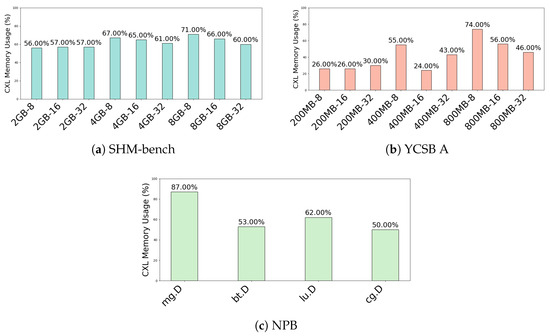

Figure 5 shows how the migration ratio to the CXL node varies with different workload configurations in the LACX environment. The x-axis represents the workload settings, combining memory usage and thread count, and the y-axis indicates the proportion of memory migrated to the CXL node for each configuration.

Figure 5.

Migration rate from LACX to CXL node by workload.

Figure 5a shows that SHM-bench, which intentionally generates shared data, maintains a high migration ratio across all settings. The migration ratio ranges from a minimum of 56% (2 GB, 8 threads) to a maximum of 71.00% (8 GB, 8 threads), with larger memory usage leading to more shared pages. Figure 5b for YCSB A shows that the migration ratio varies from 24.00% (400 MB, 16 threads) to 74% (800 MB, 8 threads), with a sharp increase as memory usage increases, even with fewer threads. Figure 5c for NPB shows different results depending on the workload type, with cg.D exhibiting about a 50% migration ratio and mg.D reaching up to 87.40%. This variation is attributed to differences in the amount of shared data within the internal parallel processing structures of each NPB workload.

These results quantitatively demonstrate that LACX can precisely identify shared data based on workload characteristics and access patterns and migrate it appropriately to CXL nodes. In particular, workloads with a larger number of threads, higher memory usage, or parallel computation structures with shared data exhibit higher migration ratios. This clearly indicates that LACX successfully implements a sharing-aware migration policy across diverse workload environments.

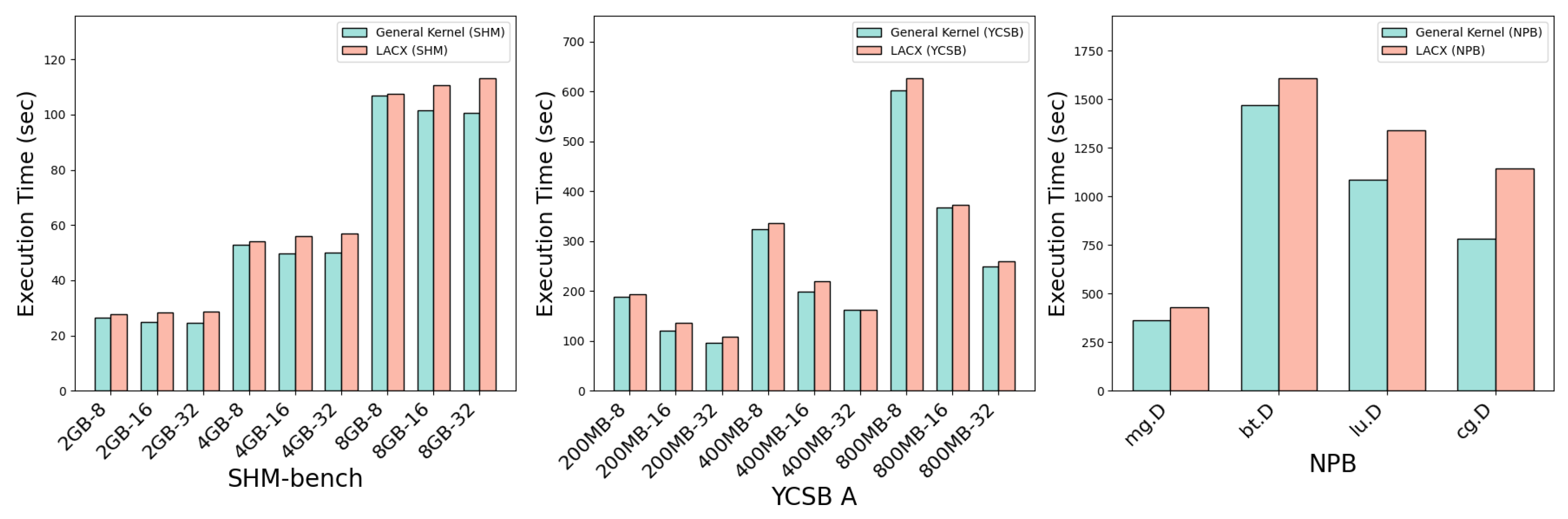

4.3. Performance Impact

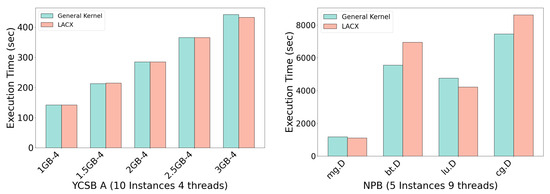

Migrating shared data to CXL nodes can lead to performance degradation in single-workload environments. This is primarily due to the overhead associated with remote memory access and the costs incurred during data migration. However, as the number of concurrent workloads increases and overall system memory utilization grows, actively leveraging the CXL node can result in system-wide performance improvements.

Figure 6 presents a comparison of execution times between the standard kernel and LACX across various memory and thread count configurations for SHM-bench, YCSB A, and NPB workloads. In SHM-bench, when 32 threads access 2 GB of shared memory, LACX exhibits approximately a 14% increase in execution time. For YCSB A, processing 200 MB of records with 32 threads results in about a 12% execution time increase under LACX. Although only YCSB A results are shown here, additional experiments with other YCSB workloads revealed similar trends, justifying the use of YCSB A as a representative example. Single-instance NPB workloads display comparable patterns, where execution times increase under LACX across mg, bt, lu, and cg workloads, with cg.D showing the highest increase of nearly 46.6%. This degradation is linked to high shared data access intensity and computational dependencies in these workloads, where remote access latency and migration overhead become critical bottlenecks.

Figure 6.

Comparison of single-instance workload execution time differences between the general kernel and LACX.

Workloads with greater thread-level parallelism and denser shared data tend to experience heightened impact from remote access latency and migration overhead, which appears to be the principal cause of performance degradation in single-workload scenarios. Conversely, in multi-workload or memory-constrained situations, LACX’s strategy of migrating shared data to the CXL node reduces saturation on high-tier nodes, thereby improving memory resource utilization and bandwidth efficiency, as supported by bandwidth and memory distribution measurements. The impact of LACX varies by workload characteristics. SHM-bench, featuring a straightforward shared memory access pattern, benefits less from increased parallelism, while migration overhead scales with shared access intensity. YCSB A leverages thread-level parallelism, leading to decreased execution times with more threads; however, this improvement is partially offset by LACX’s migration of shared data to the CXL node. For NPB workloads, the effect is strongly influenced by how shared data is structured and accessed, resulting in varying performance outcomes.

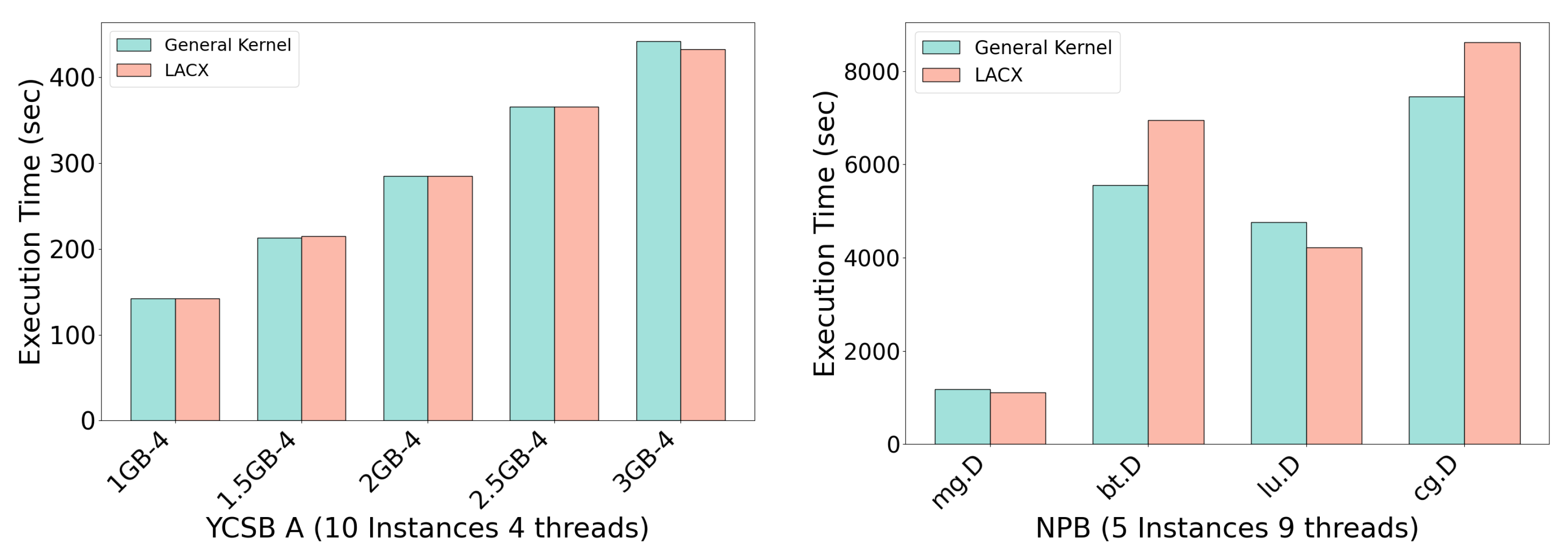

Extending this analysis, Figure 7 illustrates execution time changes when running ten sequential YCSB A workloads. In low memory pressure environments with a single workload, LACX causes up to a 14% increase in execution time; however, under multitasking conditions with higher aggregated memory demands, LACX reduces execution time by up to 3%. This gain is attributed to the retention of high-locality pages in high-tier nodes and the proactive shared data distribution to the CXL node, which alleviates pressure on high-tier resources. Consequently, memory utilization and effective bandwidth increase, leading to shorter execution times. This behavior is closely tied to NUMA memory allocation strategies. When multiple workloads run sequentially, early workloads primarily consume high-tier node memory, forcing later workloads to allocate from the CXL node as high-tier nodes saturate. LACX’s proactive migration of shared data preserves high-tier memory for private data, maximizing local access and enhancing overall system performance.

Figure 7.

Comparison of multi-instance workload execution time between general kernel and LACX.

Similar trends emerge in NPB workloads. Running five repeated executions of mg, bt, lu, and cg (size D) with nine threads each, mg and lu demonstrate execution time reductions of approximately 5% and 11%, respectively, evidencing LACX’s effectiveness in highly parallel workloads with well-distributed shared data. Conversely, bt and cg exhibit execution time increases (about 25% and 15%), likely due to concentrated shared access patterns or strong computational dependencies, where migration overhead surpasses the benefits.

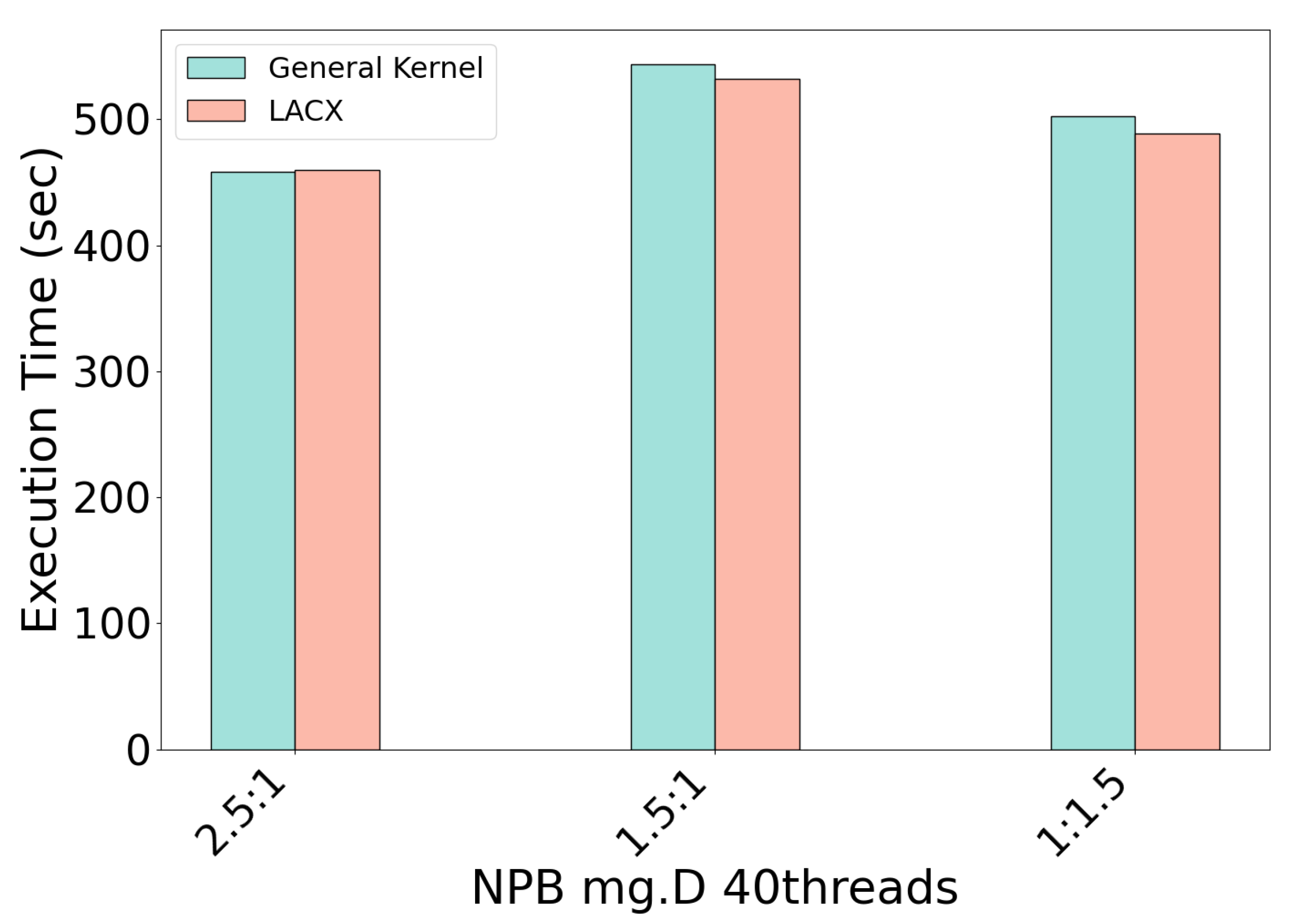

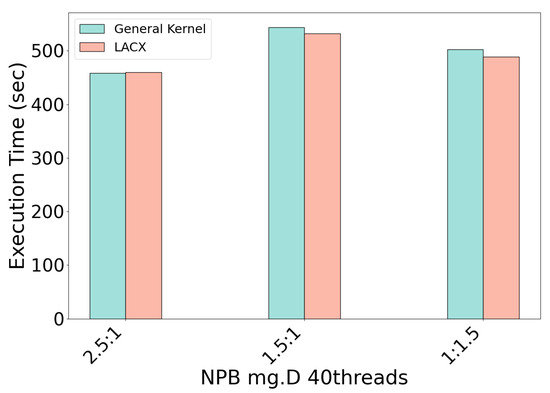

To investigate LACX’s impact under severe memory constraints, we evaluated the mg.D workload with 40 threads and a memory demand of nearly 90% of the total VM capacity. In this scenario, high-tier node memory alone cannot accommodate the workload, necessitating data allocation to the CXL node. Figure 8 compares execution times between the standard kernel and LACX across different memory capacity ratios of high-tier to CXL nodes. When high-tier nodes have 2.5 times the memory of the CXL node, performance differences are negligible. At a 1.5:1 ratio, LACX achieves a 2.1% reduction in execution time; when the CXL node’s capacity exceeds that of high-tier nodes (1:1.5), LACX attains a 6.2% performance improvement. These results highlight that in memory-constrained environments, proactive shared data migration to the CXL node is especially beneficial. Unlike the standard kernel’s arbitrary data distribution, which neglects locality, LACX selectively migrates shared data to the CXL node and reserves high-tier memory predominantly for private data. This strategy maximizes local memory access and yields increasingly significant performance advantages as reliance on the CXL node grows.

Figure 8.

Execution time of NPB mg.D under memory-constrained conditions with varying CXL usage.

4.4. Memory Usage and Bandwidth Analysis

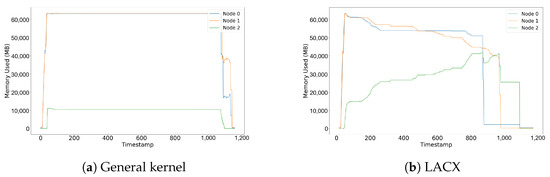

Figure 9a and Figure 9b show the changes in memory usage per node over time while running five instances of the NPB mg.D workload under the general kernel and LACX environments, respectively. Each instance uses nine threads in a similar configuration. In both figures, the x-axis represents the elapsed time from the start to the completion of the workloads, while the y-axis indicates the amount of memory allocated to each node.

Figure 9.

Memory usage over time for general and LACX under NPB mg.D workload with 5 concurrent operations.

In the general kernel environment, the memory usage of the CXL node begins to increase only after the memory of the high-tier nodes is fully exhausted. In contrast, under LACX, memory migration to the CXL node occurs in parallel with the usage of the high-tier nodes, resulting in a rapid and earlier increase in CXL memory utilization. Each workload is executed sequentially, and the total memory demand exceeds the capacity of the high-tier nodes, necessitating the use of the CXL node. In this scenario, LACX delays the point at which the DRAM limit is reached compared to the general kernel. By migrating shared data between tasks to the CXL node, LACX ensures that only non-shared data with high local access likelihood remain in the high-tier nodes, thereby improving the overall proportion of local accesses.

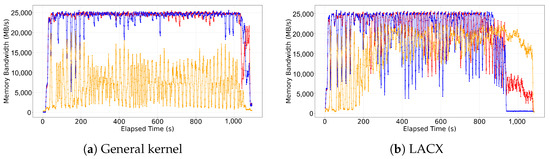

Figure 10 shows the results of measuring per-node memory bandwidth usage over time using PCM-memory during the sequential execution of five NPB mg.D workloads. The five workloads were executed sequentially, utilizing all high-tier nodes and allocating some memory pages to CXL nodes as well. In Figure 10a, which shows the general kernel environment, the bandwidth usage of the high-tier nodes (red and blue) remains consistently high, reaching nearly 25,000 MB/s for most of the execution period. In contrast, the CXL node (orange) exhibits low and unstable bandwidth throughout, indicating minimal actual utilization.

Figure 10.

Memory bandwidth usage over time for general and LACX under NPB mg.D workload with 5 concurrent operations.

In Figure 10b, which shows the LACX environment, the bandwidth usage of the high-tier nodes also starts high, similar to the general kernel. However, starting around 250–300 s into execution, the bandwidth of the CXL node increases sharply and remains mostly between 15,000 MB/s and 20,000 MB/s, occasionally surpassing 20,000 MB/s. This demonstrates that LACX effectively redistributes memory traffic by migrating shared data to CXL nodes, thereby improving overall bandwidth utilization efficiency across the memory hierarchy.

This trend is also quantitatively confirmed in Table 3, which summarizes the maximum, minimum, and average bandwidth observed for each node in Figure 9 under both the general kernel and LACX environments. Notably, the CXL node shows a +149.2% increase in average bandwidth usage, representing the largest improvement. Meanwhile, the high-tier nodes experience a slight decrease on average, but the total average bandwidth across the system increases by approximately 6.7%, indicating improved resource utilization of the entire memory tier.

Table 3.

Bandwidth comparison between two experiments.

5. Discussion and Future Research

Overall, our evaluations demonstrate that LACX effectively optimizes NUMA memory utilization in multi-workload environments with high-tier memory usage. In particular, migrating shared data to CXL nodes alleviates memory pressure on high-tier memory and improves overall memory bandwidth efficiency across the system.

In contrast, in environments that are not memory-intensive or are dominated by a single workload, migration costs become relatively higher, and performance degradation may occur in certain scenarios. This can be attributed to the increased frequency of migrations for shared data and the resulting rise in remote accesses. While CXL offers the advantages of expanded memory capacity and flexible tiering, its placement in low-tier memory means that it cannot match the performance of high-tier memory. Therefore, if there is available capacity in high-tier memory, it is preferable to use high-tier memory to maximize the system performance.

This study focuses on scenarios where memory usage exceeds the capacity of high-tier memory, and in such cases, CXL acts not merely as auxiliary storage but as an essential resource. This addresses the growing demand for large memory pools and expanded bandwidth in modern workloads that surpass the limits of DRAM. In such environments, the shared data migration mechanism proposed by LACX has been shown to alleviate bottlenecks in high-tier memory and improve bandwidth utilization across all memory tiers.

Building on the current implementation of LACX, future research will focus on dynamically adjusting the migration policy based on real-time system conditions to further optimize performance and reduce overhead. Two key metrics will guide this adaptation: page reference frequency and memory tier saturation. By analyzing page reference frequency, the system can identify pages migrated to CXL memory that are likely to be reused frequently in DRAM and promote them back to high-tier memory, minimizing unnecessary remote accesses and maintaining data locality, especially in workloads with low sharing or dominance by a single process. Additionally, monitoring memory saturation will enable LACX to activate migration policies only when the DRAM nodes surpass specified utilization thresholds, avoiding migration overhead during periods of low memory pressure. Conversely, when sufficient capacity is available in high-tier memory, the migration mechanisms can be automatically disabled to prevent performance degradation. This state-based activation and fallback framework aims to ensure consistent performance improvements across diverse workload profiles and system states, making LACX adaptable to practical deployment challenges in heterogeneous memory environments. Through these adaptive strategies, LACX aims to maintain consistent performance benefits and efficient bandwidth utilization across diverse workload patterns and dynamic operating environments.

6. Conclusions

This study proposes LACX, a novel technique for efficiently identifying and managing shared data in CXL-based resource consolidation environments. By migrating shared data to CXL nodes, LACX alleviates bandwidth pressure on high-tier memory and effectively addresses the problem of remote access to shared data in NUMA environments. We developed and implemented this low-cost policy to optimize memory bandwidth utilization without introducing significant overhead. Our evaluation results show that, in multi-workload environments with high memory usage, LACX achieves up to a 14% performance improvement over the original kernel by distributing bandwidth pressure on high-tier memory and optimizing local data access. These results demonstrate that LACX is particularly effective in large-scale workloads that exceed the capacity of high-tier memory, providing meaningful bandwidth bottleneck mitigation and improving overall system efficiency.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.J. (Hayong Jeong) and M.J.; methodology, H.J. (Hayong Jeong); software, H.J. (Hayong Jeong); validation, B.S. and H.J. (Heeseung Jo); formal analysis, H.J. (Hayong Jeong); investigation, H.J. (Hayong Jeong); writing—original draft preparation, H.J. (Hayong Jeong); writing—review and editing, M.J. and H.J. (Heeseung Jo); supervision, H.J. (Heeseung Jo). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Electronics and Telecommunications Research Institute(ETRI) grant funded by the Korean government [25ZS1100, Research on High-Performance Computing to overcome Limitations of AI] and by Chungbuk National University BK21 program(2025).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to institutional restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Farmahini-Farahani, A.; Gurumurthi, S.; Loh, G.; Ignatowski, M. Challenges of High-Capacity DRAM Stacks and Potential Directions. In Proceedings of the MCHPC’18: Workshop on Memory Centric High Performance Computing, Dallas, TX, USA, 11 November 2018; pp. 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Shahroodi, T.; Hassan, H.; Patel, M.; Yağlıkçı, A.G.; Orosa, L. CLR-DRAM: A Low-Cost DRAM Architecture Enabling Dynamic Capacity-Latency Trade-off. In Proceedings of the 2020 ACM/IEEE 47th Annual International Symposium on Computer Architecture (ISCA), Valencia, Spain, 30 May–3 June 2020; pp. 666–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepers, B.; Quéma, V.; Fedorova, A. Thread and Memory Placement on NUMA Systems: Asymmetry Matters. In Proceedings of the USENIX Annual Technical Conference (USENIX ATC), Santa Clara, CA, USA, 8–10 July 2015; pp. 277–289. Available online: https://www.usenix.org/conference/atc15/technical-session/presentation/lepers (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Dashti, M.; Fedorova, A.; Funston, J.; Gaud, F.; Lachaize, R.; Lepers, B.; Quema, V.; Roth, M. Traffic Management: A Holistic Approach to Memory Placement on NUMA Systems. In Proceedings of the ASPLOS 13: Architectural Support for Programming Languages and Operating Systems, Houston, TX, USA, 16–20 March 2013; pp. 381–394. [Google Scholar]

- Gaud, F.; Lepers, B.; Funston, J.; Dashti, M.; Fedorova, A.; Quéma, V.; Lachaize, R.; Roth, M. Challenges of Memory Management on Modern NUMA System: Optimizing NUMA Systems Applications with Carrefour. ACM Queue 2015, 13, 70. Available online: https://queue.acm.org/detail.cfm?id=2852078 (accessed on 28 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Gaud, F.; Lepers, B.; Decouchant, J.; Funston, J.; Fedorova, A.; Quéma, V. Large Pages May Be Harmful on NUMA Systems. In Proceedings of the USENIX ATC 14: 2014 USENIX conference on USENIX Annual Technical Conferen, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 19–20 June 2014; pp. 231–242. Available online: https://www.usenix.org/conference/atc14/technical-sessions/presentation/gaud (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Author, A.; Author, B.; Author, C. Shuhai: A Tool for Benchmarking High Bandwidth Memory on FPGAs. IEEE Trans. Comput. 2021, 70, 922–935. [Google Scholar]

- Choukse, E.; Erez, M.; Alameldeen, A.R. Compresso: Pragmatic Main Memory Compression. In Proceedings of the 2018 51st Annual IEEE/ACM International Symposium on Microarchitecture (MICRO), Fukuoka, Japan, 20–24 October 2018; pp. 546–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compute Express Link (CXL). Available online: https://www.computeexpresslink.org/ (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Micron Technology, Inc. CXL Memory Expansion: A Closer Look on Actual Platform. Available online: https://www.micron.com/content/dam/micron/global/public/products/white-paper/cxl-memory-expansion-a-close-look-on-actual-platform.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Chen, Y.; Dong, X.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Sun, G. FPGA-based Emulation and Device-Side Management for CXL-based Memory Tiering Systems. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.19233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Berger, D.S.; Waldspurger, C.; Wee, R.; Agarwal, I.; Agarwal, R.; Hady, F.; Kumar, K.; Hill, M.D.; Chowdhury, M.; et al. Managing Memory Tiers with CXL in Virtualized Environments. In Proceedings of the USENIX Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation (OSDI), Santa Clara, CA, USA, 10–12 July 2024; pp. 37–56. Available online: https://www.usenix.org/conference/osdi24/presentation/zhong-yuhong (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Li, H.; Berger, D.S.; Hsu, L.; Ernst, D.; Zardoshti, P.; Novakovic, S.; Shah, M.; Rajadnya, S.; Lee, S.; Agarwal, I.; et al. Pond: CXL-Based Memory Pooling Systems for Cloud Platforms. In Proceedings of the ASPLOS 23: 28th ACM International Conference on Architectural Support for Programming Languages and Operating Systems, Volume 2, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 25–29 March 2023; pp. 574–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Nalla, P.S.; Krishnan, G.; Joshi, R.V.; Cady, N.C.; Fan, D. Digital-Assisted Analog In-Memory Computing with RRAM Devices. In Proceedings of the 2023 International VLSI Symposium on Technology, Systems and Applications (VLSI-TSA/VLSI-DAT), HsinChu, Taiwan, 17–20 April 2023; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignali, R.; Zurla, R.; Pasotti, M.; Rolandi, P.L.; Singh, A.; Gallo, M.L. Designing Circuits for AiMC Based on Non-Volatile Memories: A Tutorial Brief on Trade-Off and Strategies for ADCs and DACs Co-Design. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2024, 71, 1650–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NUMA Balancing (AutoNUMA). Available online: https://mirrors.edge.kernel.org/pub/linux/kernel/people/andrea/autonuma/autonuma_bench-20120530.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Maruf, H.A.; Wang, H.; Dhanotia, A.; Weiner, J.; Agarwal, N.; Bhattacharya, P.; Petersen, C.; Chowdhury, M.; Kanaujia, S.; Chauhan, P. TPP: Transparent Page Placement for CXL-Enabled Tiered-Memory. In Proceedings of the ASPLOS 23: 28th ACM International Conference on Architectural Support for Programming Languages and Operating Systems, Volume 3, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 25–29 March 2023; pp. 742–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achermann, R.; Panwar, A.; Bhattacharjee, A.; Roscoe, T.; Gandhi, J. Mitosis: Transparently Self-Replicating Page-Tables for Large-Memory Machines. In Proceedings of the ASPLOS 20: Architectural Support for Programming Languages and Operating Systems, Lausanne, Switzerland, 16–20 March 2020; pp. 283–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entezari-Maleki, R.; Cho, Y.; Egger, B. Evaluation of memory performance in NUMA architectures using Stochastic Reward Nets. J. Parallel Distrib. Comput. 2020, 144, 172–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intel. What Is Optane Technology? Available online: https://www.intel.com/content/dam/www/public/us/en/documents/technology-briefs/what-is-optane-technology-brief.pdf (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Duraisamy, P.; Xu, W.; Hare, S.; Rajwar, R.; Culler, D.; Xu, Z.; Fan, J.; Kennelly, C.; McCloskey, B.; Mijailovic, D.; et al. Towards an Adaptable Systems Architecture for Memory Tiering at Warehouse-Scale. In Proceedings of the ASPLO 2023: 28th ACM International Conference on Architectural Support for Programming Languages and Operating Systems, Volume 3, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 25–29 March 2023; pp. 727–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuppalapati, M.; Agarwal, R. Tiered Memory Management: Access Latency Is the Key! In Proceedings of the SOSP 24: ACM SIGOPS 30th Symposium on Operating Systems Principles, Austin, TX, USA, 4–6 November 2024; pp. 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Hadian, H.; Xu, H.; Li, H. Tiered Memory Management Beyond Hotness. In Proceedings of the 19th USENIX Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation (OSDI), Boston, MA, USA, 7–9 July 2025; pp. 731–747. [Google Scholar]

- Ni, Y.; Mehra, P.; Miller, E.; Litz, H. TMC: Near-Optimal Resource Allocation for Tiered-Memory Systems. In Proceedings of the SoCC 23: ACM Symposium on Cloud Computing, Santa Cruz, CA, USA, 30 October 2023–1 November 2023; pp. 376–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- cslabcbnu. SHM-Bench. Available online: https://github.com/cslabcbnu/SHM-bench (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Cooper, B.F.; Silberstein, A.; Tam, E.; Ramakrishnan, R.; Sears, R. Benchmarking Cloud Serving Systems with YCSB. In Proceedings of the SoCC 10: 1st ACM Symposium on Cloud Computing in Conjunction with SIGMOD 2010, Indianapolis, IN, USA, 10–11 June 2010; pp. 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NASA Advanced Supercomputing Division. NAS Parallel Benchmarks. Available online: https://www.nas.nasa.gov/software/npb.html (accessed on 12 June 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).