Abstract

Intrusion detection aims to identify the unauthorized activities within computer networks or systems by classifying events into normal or abnormal categories. As modern scenarios often involve multi-source data, multi-view fusion deep learning methods are employed to leverage diverse viewpoints for enhancing security threat detection. This paper introduces a novel intrusion detection approach using multi-view fusion within a federated learning framework, proposing an integrated AE Neural SVM (AE-NSVM) model that combines auto-encoder (AE) multi-view feature extraction and Support Vector Machine (SVM) classification. This approach simultaneously learns representative features from multiple views and classifies network samples into normal or seven attack categories while employing federated learning across clients to ensure adaptability and robustness in diverse network environments. The experimental results obtained from two benchmark datasets validate its superiority: on TON_IoT, the CAE-NSVM model achieves a highest F1-measure of 0.792 (1.4% higher than traditional pipeline systems); on UNSW-NB15, it delivers an F1-score of 0.829 with a 73% reduced training time and an 89% faster inference compared to baseline models. These results demonstrate the advantages of multi-view fusion in federated learning for balancing accuracy and efficiency in distributed intrusion detection systems.

1. Introduction

The rapid development of computers and the Internet has ushered in an era of unprecedented convenience and connectivity for humankind, enabling digitalization and automation in both personal and business domains. However, this progress has also brought forth a surge in complex cybersecurity issues, encompassing large-scale data breaches [1,2], network attacks [3,4,5,6], malicious software [7,8], and vulnerabilities in Internet of Things (IoT) devices [9,10,11,12]. These issues pose significant threats to personal privacy, corporate secrets, and the security of critical infrastructure.

In recent years, the development of artificial intelligence has provided more advanced technological support for cyber attacks, posing greater challenges to cyber security. Consequently, it necessitates continual efforts to enhance cybersecurity capabilities, ensuring the secure and beneficial utilization of computers and the IoT in this digital age.

As an active defense technology, intrusion detection systems (IDSs) that can identify abnormal requests in the communication network, detect potential network threats, and generate alarms have gradually become a key technology to ensure network security. An IDS detects intrusion behavior by analyzing activities such as system logs, CPU and memory usage, system calls, file modifications, and real-time network traffic characteristics, which we will call views in this paper [13,14]. Multi-view analysis and learning can efficiently improve the accuracy and robustness of detection systems. By integrating the multiple views or perspectives of data mentioned above, multi-view learning enables a comprehensive analysis of the underlying patterns and characteristics of network intrusions. This approach leverages the diversity of information sources, allowing for a more holistic understanding of attacks and facilitating the identification of sophisticated and stealthy intrusion attempts that may be missed by single-view methods. Additionally, multi-view learning can effectively mitigate the impact of noisy or incomplete data, as information from different views can complement and cross-validate each other, leading to improved detection performance and reduced false positive rates [15,16,17]. Furthermore, the incorporation of multiple views in the learning process enhances the resilience of IDSs against evasion techniques employed by attackers, as any single-view modification or manipulation is less likely to go unnoticed. Thus, this paper utilizes a multi-view learning framework to enhance the accuracy, robustness, and adaptability of IDSs in the face of evolving cyber threats in systems. While we focus on the IT domain in this work, in the context of business-related zoning, multi-view techniques are also very applicable to combined IT/OT scenarios.

Based on the fused features, a classifier that determines if anomalies occur is another important step in intrusion detection. The classifier uses the extracted features as input and applies a predefined algorithm or model to make predictions about the nature of the traffic. There are two kinds of classifiers called rule-based classifiers and machine learning classifiers. Rule-based classifiers utilize predefined rules or signatures to match against the extracted features and determine if an intrusion is present. It is effective in detecting known attacks but may struggle with detecting new or unknown attack patterns. Machine learning algorithms, such as decision trees [18,19], SVMs [20,21,22], random forests [23,24,25], or neural networks [26,27], can be trained using labeled datasets to learn patterns and make predictions. These classifiers have the ability to detect both known and unknown attack patterns by learning from historical data.

Although neural networks dominate modern classification tasks, SVMs remain relevant in specific scenarios. Firstly, SVMs exhibit superior performance on small-scale datasets as they minimize structural risk rather than empirical risk, enabling robust generalization with limited labeled samples. Secondly, SVMs provide interpretable decision boundaries through kernel-induced feature mapping, which is critical for security-critical applications requiring transparent reasoning. Thirdly, SVMs offer computational efficiency in high-dimensional spaces, avoiding the heavy parameter tuning and computational costs associated with deep neural networks, making them suitable for resource-constrained edge devices in distributed networks.

However, the traditional IDS follows a structured workflow, where feature learning extracts relevant features from the data, and classifiers, such as SVMs, use these features to make decisions regarding the presence of an attack, which is called a pipeline system [24,28,29]. The goal of feature learning is to transform the raw data into a more informative and condensed representation that enhances the detection capabilities of the subsequent classifier. However, there is a feature–classifier mismatch problem that means the extracted features may not be optimally aligned with the requirements of the classifier. The features learned during the feature extraction step may not fully capture the discriminatory aspects relevant to the classifier, leading to sub-optimal detection accuracy. Traditional neural network-based approaches can combine the feature learning and classifier into a whole network by adding a softmax layer following feature learning layers. But they require a large amount of data for parameter learning while the traditional machine learning approaches, such as SVMs and decision trees, perform well on limited datasets. Thus, in this paper, we proposed a neural network-based SVM (NSVM) approach for intrusion detection, where an SVM layer is connected to feature learning layers. Specifically, we use an auto-encoder to fuse multiple views and extract discriminative features from the hidden layers, and an SVM layer is connected to the hidden layers for classification. In this way, the feature fusion and classification are combined into a whole neural network and optimized jointly. We call the proposed approach an auto-encoder neural network SVM (AE-NSVM).

Moreover, we propose to train the models using multi-view, fusion-based federated learning. Federated learning is a decentralized machine learning approach that addresses the challenges of distributed learning and privacy protection. Federated learning trains the model on local devices, and it then transmits the encrypted model parameters to a central server. Next, the model on the central server is updated by aggregating received parameters. First, to fuse the multiple views describing the states of various aspects of hosts and networks, we utilize an auto-encoder (AE) to learn representative features; second, the fused features are fed into an SVM to classify the samples into normal or seven other kinds of attacks. Different from the traditional pipeline system that includes two separated sequential steps of feature learning and classification, we propose an AE-NSVM model wherein an SVM layer is connected to the AE hidden layer to simultaneously perform feature learning and classification. In AE-NSVM, feature learning aims to learn representative information from multiple views, as well as improve classification results by combining the two processes together. Finally, the proposed AE-NSVM models are created on multiple clients using a federated learning strategy. We implemented four kinds of AE to compare the feature learning performances.

The contributions of this paper are as follows.

- Multi-view fusion: We propose an AE-based multi-view fusion approach for intrusion detection. To leverage heterogeneous intrusion data, we integrate multiple modalities to capture complementary intrusion patterns;

- Joint loss optimization: Integrating AE multi-view reconstruction loss and SVM’s hinge loss to align feature learning with classification objectives;

- End-to-end feature-classifier integration: Direct connection between the AE hidden layer and SVM layer eliminates information loss in pipeline-based approaches. Experimental results show a 1.4% F1-measure improvement over separate AE+SVM frameworks;

- Systematic evaluation of AE variants: Convolutional auto-encoder (CAE) is identified as optimal (F1-measure 0.781) due to its superiority in extracting local spatial correlations from high-dimensional data.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the related work on current intrusion detection technologies. Section 3 proposes an AE-NSVM approach for intrusion detection. Section 4 presents an approach to analyze the anomaly in different clients using a federated learning strategy. Section 5 is the analysis and experimental results of the proposed approaches.

2. Related Work

Feature learning, as the first important step of intrusion detection, enables the automatic extraction of relevant and discriminative patterns from network data. Multi-view feature fusion further enhances the effectiveness of intrusion detection by integrating information from multiple perspectives or data sources. This approach harnesses the complementary nature of different views, such as network traffic, system logs, or host states, to create a more comprehensive and accurate understanding of the network environment. He et al. [30] proposed a multimodal approach as a multi-view technique for intrusion detection. Different level features are extracted from the network connection, rather than the long feature vector used in the traditional approach, which can process feature information separately in a more efficient manner. The authors were able to significantly improve the detection accuracy on a variety of datasets, including outdated and novel ones. However, the authors did not take into account the network traffic behavior changes over time. On the other hand, Li et al. [31] proposed a multi-view approach for spam detection in resource-constrained environments. The authors assumed a semi-supervised setting, wherein a multi-view setting was used for the label of other events. Although the authors considered a more realistic scenario with model updates, their used dataset does not present a long data period without natural behavior changes. The authors in [32] proposed a semi-supervised co-training approach using a multi-view nature of attacks. In this approach, the attack behavior will be maintained in multiple views, and attack detection will be performed using the predictions conducted by ML models of multiple views of an attack. They used a centralized approach for implementing their research and utilized an active labeling procedure for labeling unknown attacks by experts. The researchers in [33] introduced multi-view features of MQTT data and evaluated features using centralized ML algorithms. The authors in these works proposed their methodologies as a centralized approach. Attota et al. [34] proposed a federated learning-based intrusion detection approach called multi-view federated learning intrusion detection (MV-FLID), which trains on multiple views of IoT network data in a decentralized format to detect, classify, and defend against attacks. The multi-view ensemble learning aspect helps in maximizing the learning efficiency of different classes of attacks.

The distributed nature of multiple clients often necessitates that the data within these clients comply with privacy protection requirements. Traditional centralized intrusion detection models require all data to be aggregated at a central data center for model training. This centralized network model structure conflicts with the inherently distributed nature of federated learning environments and fails to protect private data. Therefore, centralized intrusion detection models are no longer adequate to meet the security requirements of such distributed network structures. Federated learning perfectly matches the distributed nature of trusted regions and protects local data privacy by only passing model parameters. The distributed nature of the approach ensures that training data confidentiality is maintained on the devices, while the shared model gains from the pooled knowledge of all the devices. Nguyen et al. [35] introduced federated learning into an intrusion detection field for the first time and presented a self-learning distributed system in which the federated learning model performs intrusion detection by detecting device status. Zhao et al. [36] constructed a federated learning model based on Convolutional Neural Networks (FedACNN), and the experimental results proved that FedACNN can improve the detection accuracy up to 99.7%. Li [37] first proposed a federated learning method based on a real industrial environment, which achieved experimental results superior to traditional machine learning algorithms. Campos et al. [38] verified that different data distributions have a significant impact on the effectiveness of federated learning. To balance sample distribution, the authors proposed a sampling method based on Shannon entropy, which achieved good experimental results.

Despite advancements in multi-view intrusion detection, three critical limitations persist in existing approaches.

- Objective misalignment in sequential pipelines: Traditional multi-view frameworks (e.g., cascaded auto-encoder classifier designs) decouple feature extraction and classification into independent, sequential stages. This separation forces feature extractors to optimize reconstruction-oriented losses (e.g., MSE for auto-encoders) without direct guidance from downstream classification objectives, resulting in features that are suboptimally discriminative for intrusion detection tasks and prone to information loss during stage-wise transfer;

- Insufficient multi-view fusion in federated learning: Federated learning applications in intrusion detection primarily focus on single-view data, neglecting complementary insights from heterogeneous modalities. Additionally, systematic evaluations of feature fusion models (e.g., auto-encoder variants) under distributed settings remain scarce, hindering the balance between detection accuracy and computational efficiency;

- Non-end-to-end integration of hybrid models: Hybrid architectures combining neural networks (e.g., auto-encoders) and traditional classifiers (e.g., SVMs) adopt a rigid “feature extraction → classification” pipeline without cross-module joint training. Unlike end-to-end models, this design prevents the backward propagation of classification loss to the feature extractor, leaving neural network parameters optimized solely for reconstruction rather than discriminative feature learning. This disconnection of parameter updates limits the model’s ability to adapt features to intrusion detection-specific decision boundaries.

To address these limitations, this study proposes a multi-view federated learning framework integrating Auto-Encoder Neural SVM (AE-NSVM). This approach directly connects an SVM classification layer to the hidden layer of an auto-encoder (AE), enabling end-to-end joint optimization of multi-view feature fusion and intrusion classification. By unifying the reconstruction loss (for feature learning) and hinge loss (for classification) into a single objective function, the framework aligns feature representation with detection tasks, mitigating the information loss in traditional pipelines. Furthermore, the proposed method systematically evaluates four AE variants to identify optimal multi-view fusion performance, and it extends the model to federated learning, ensuring privacy preservation while enhancing detection accuracy and computational efficiency across distributed clients.

3. Proposed Approach

In this section, we will describe the architectures of the proposed approaches. Mainly, we utilize AEs to fuse five views that provide different perspectives on the host activities to take advantage of the complementary information in each view, as shown in the lower part of the architecture. Multi-view fusion techniques can also help to reduce false positives and increase the overall detection rate [39,40,41]. The fused features are used for intrusion detection using an SVM classifier. We refer to these separate processes of feature fusion and classification as pipeline systems. However, the pipeline system treats feature generation and classification as distinct processes, where specialized algorithms are employed for feature generation, with no explicit optimization for classification. This dichotomy may cause a reduction in the detection performance of the system. Thus, we use a joint training strategy that combines the two processes within a singular neural network architecture, facilitating the acquisition of features that are specifically optimized for classification purposes. This mechanism yields superior feature learning and classification. In this paper, we introduce AE Neural SVM (AE-NSVM), an architecture that uses AEs for feature fusion extraction and an SVM layer for classification to fuse the multiple views of the host. In order to effectively address the issues of data privacy and security in a distributed environment, while also enhancing the effectiveness and efficiency of machine learning, we propose to apply our AE-SVM model to multiple clients, and federated learning is utilized to train the model parameters.

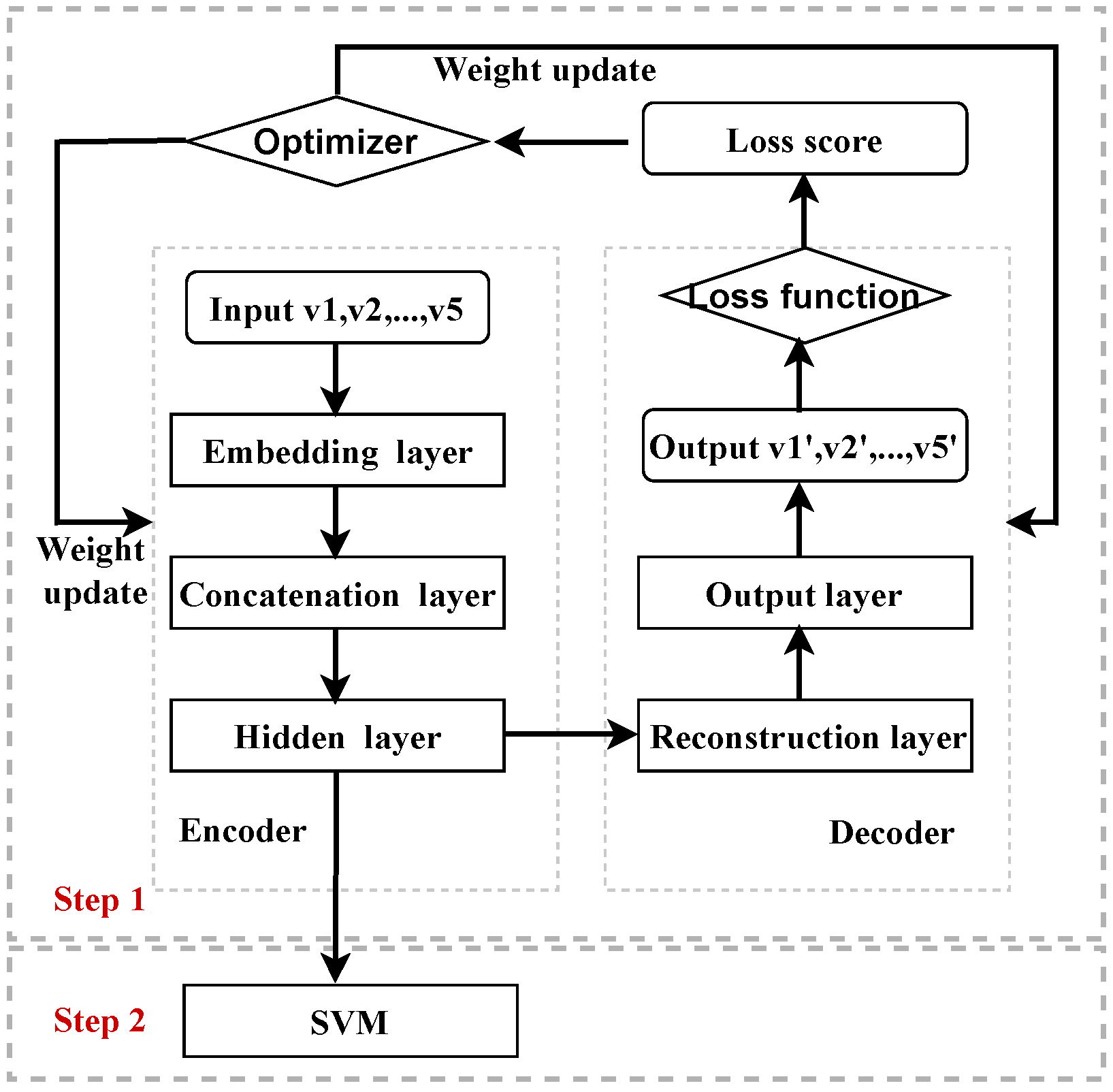

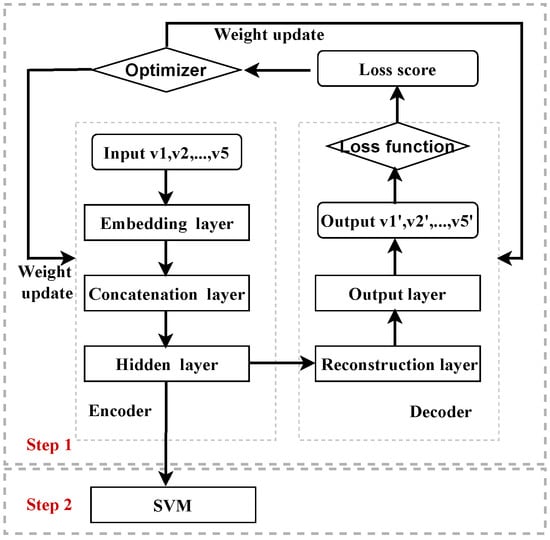

Figure 1 shows the architecture of the pipeline system of AE and SVMs. The training process includes two steps of feature fusion using an AE and SVM classification. Firstly, in the encoding part of the AE, the data from five views are embedded to vectors with fixed dimensions, and then the five vectors are concatenated together and fed into a bottleneck layer. In the decoding part, the five views are reconstructed based on the features from the hidden layer. The loss is computed by the reconstruction errors of each view and summed together. Secondly, the input data of the five views are fed into the trained AE, and the corresponding fused features are obtained from the bottleneck layer, which are then fed into the SVM for classification. The relationship between the network, layers, loss function, and the optimizer is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The relationship between the network, layers, loss function, and optimizer of the pipeline system.

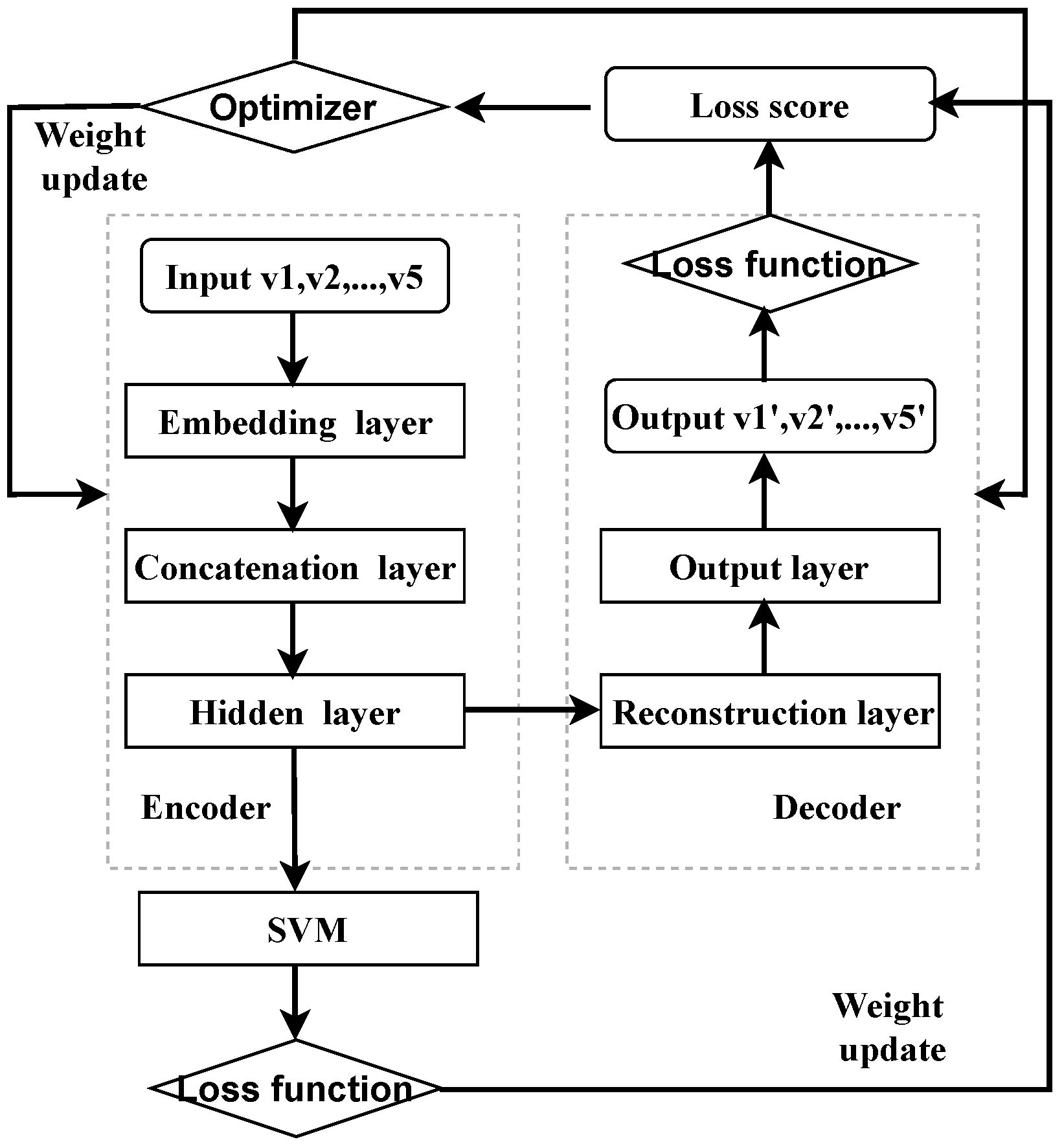

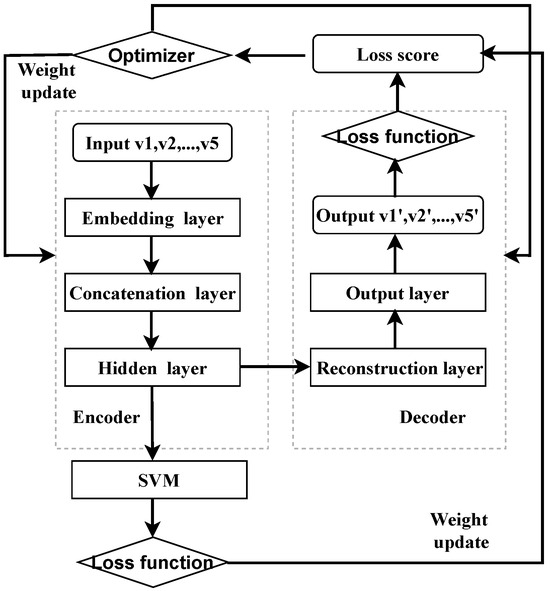

To align the objective function for the feature fusion with the final classification objective, we unify feature fusion and SVM classification in a single neural network framework by replacing the SVM classifier with a non-linear support vector output layer. During training, the margin-based loss for this support vector output layer and the reconstruction loss for the auto-encoder are simultaneously computed, and the entire network is optimized using the gradient descent algorithm. The training process of the proposed AE-NSVM is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Relationship between the network, layers, loss function, and optimizer of AE-NSVM.

The architecture of the proposed AE-NSVM-based federated learning approach involves training a shared global model on three clients while keeping the data on each client local. The federated learning process follows these steps: First, a global model is initialized and distributed to clients. Each client then trains the model locally using its own data. Next, the server aggregates the model updates from all clients. These steps are repeated for multiple rounds until the global model converges. Throughout the process, client data remains decentralized, ensuring privacy and security. By leveraging the collective knowledge learned from distributed datasets, federated learning enables collaborative model training while preserving data privacy.

3.1. Auto-Encoder-Based Multi-View Fusion

Multi-view fusion enables the incorporation of complementary information from multiple views and gains a more comprehensive and accurate understanding of potential threats and anomalies, leading to improved detection performance and a reduction in false positives.

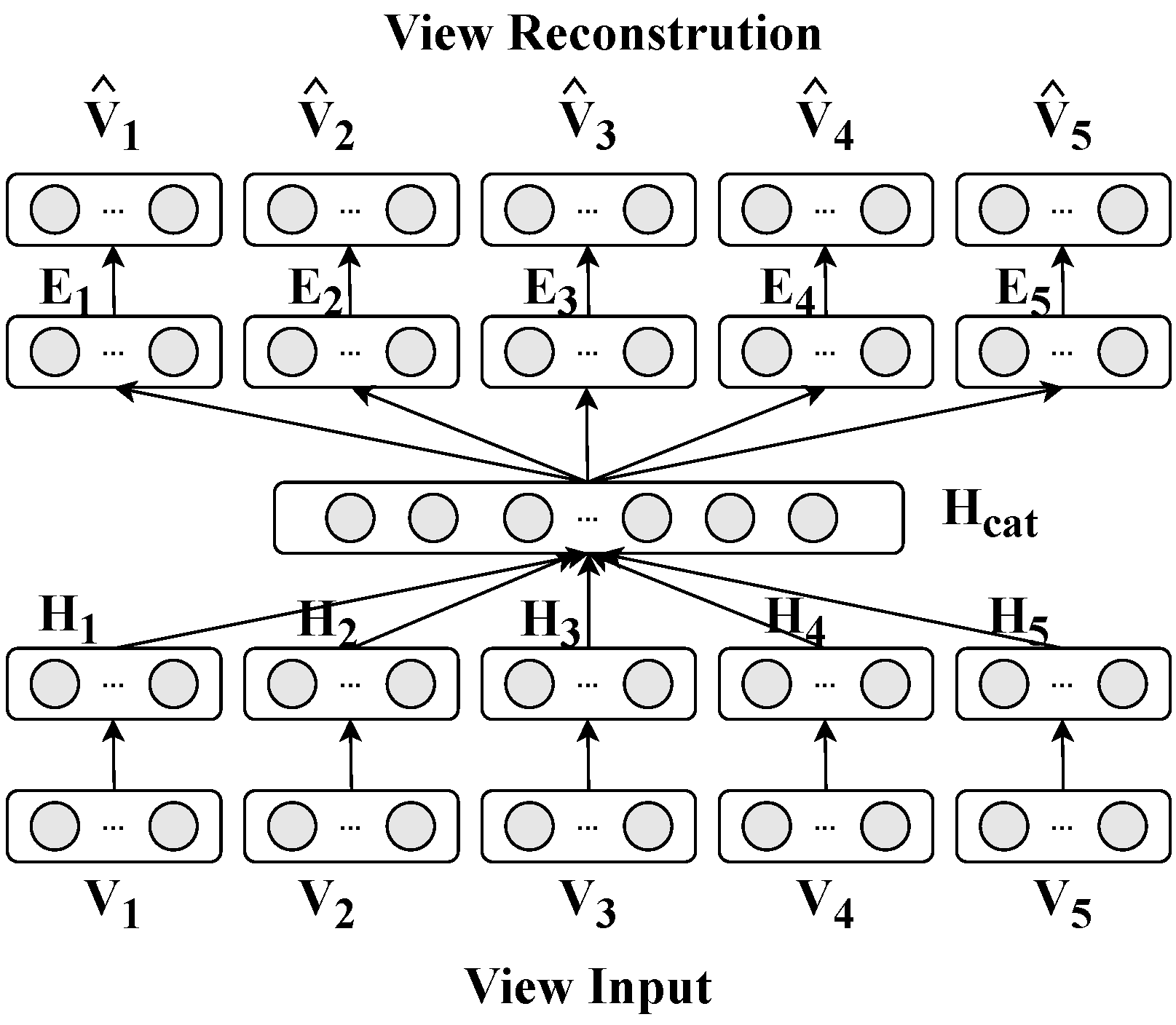

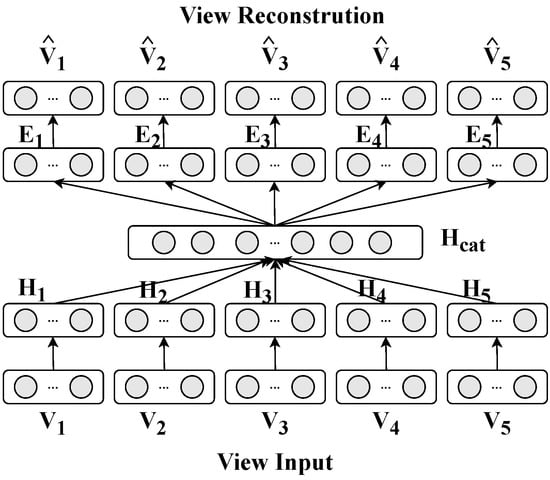

The multi-view fusion process of the proposed auto-encoder (AE) is illustrated in the accompanying diagram, which outlines the workflow from raw view input to fused feature learning and view reconstruction. As shown in Figure 3, the framework takes five heterogeneous views (denoted as to ) as input, each representing distinct aspects of the host activities (e.g., memory usage, processor metrics, disk, process behavior, and network traffic). First, each view undergoes independent encoding through view-specific encoder modules. These encoders transform raw features into compact latent representations (denoted as to ), capturing view-specific patterns. The latent vectors from all views are then concatenated into a unified feature vector , which is fed into a bottleneck layer to learn cross-view correlations and generate a fused feature representation H. To ensure the fused features retain discriminative information from all input views, the framework includes a decoder module that reconstructs each original view from the fused feature H. The reconstruction loss between input views and their decoded counterparts (e.g., ) drives the encoder to preserve critical information during feature fusion. This dual process of encoding–decoding not only integrates multi-view data, but also ensures the fused features are both representative and reconstructively accurate, laying a foundation for downstream intrusion detection tasks.

Figure 3.

The multi-view fusion architecture.

Figure 3 shows the feature fusion process. There are five views in the AE, and for each view, denoted as , they are projected into a dense vector representation, denoted as , using an encoder function . The encoding process can be represented as follows:

Then, the dense vectors of the five views, , are concatenated together into a single vector representation, denoted as :

The concatenated vector is then projected into a hidden layer, which is represented by a transformation matrix and a bias term , and this is achieved using an activation function ReLU:

In the decoding part, each view is reconstructed by an embedding layer and followed by an output layer:

Similar to the standard auto-encoder, the quality of the auto-encoder output is evaluated by comparing the reconstructed views with their corresponding original views. The reconstruction loss, typically measured using a suitable loss function such as the mean squared error (MSE), quantifies the dissimilarity between the original views and their reconstructed counterparts :

3.2. SVM-Based Intrusion Detection

Support Vector Machines (SVMs) are a powerful class of machine learning algorithms used for classification tasks. The key function of SVMs is to find an optimal hyperplane that maximally separates classes or fits the regression line with the largest margin. This margin allows SVMs to be robust to noise and generalize well to unseen data. For multi-class classification, the one-vs-rest strategy is used to train multiple binary SVM classifiers, each one distinguishing between one class and the rest of the classes.

From Equation (3), we can obtain the fused feature vector of dimension D. Additionally, you have corresponding labels for each sample, where takes values from 1 to 8, representing the eight classes. For each class k from 1 to 8, a binary SVM classifier is trained to distinguish between class k and the rest of the classes. The training set for class k is denoted as and the corresponding labels as .

For the classifier, the original labels is transformed into binary labels:

for each class k. These are then used to solve the SVM optimization problem using a quadratic programming solution:

Here, represents the weight vector, is the bias term, are the slack variables, and C is the regularization parameter that controls the trade-off between maximizing the margin and minimizing misclassifications.

To predict the class for a new input sample , first calculate the decision function for each class k from 1 to 8:

The predicted class for is the one with the highest decision value:

3.3. AE Neural SVM for Intrusion Detection

Section 3.1 and Section 3.2 describe a typical pipeline system that includes two steps of feature fusion and classification, and each step has its individual optimization function. The inconsistency of the objective function may potentially diminish the performance of classification. Based on this inspiration, we introduce an AE Neural SVM architecture that combines the benefits of both auto-encoder and SVM models for enhanced classification performance. Our approach involves incorporating an SVM layer following the hidden AE layer during joint training, as shown in Figure 2. By doing so, we can optimize both the reconstruction loss of the auto-encoder and the hinge loss of the SVM simultaneously. This joint training enables the auto-encoder to learn more informative and task-specific representations, potentially leading to enhanced classification performance.

Figure 2 shows the process of the proposed AE Neural SVM. By adding an SVM layer to the hidden layer of AE, the hinge loss is computed as follows:

where represents the output of the decision function for the given feature vector from the hidden layer of AE. The loss of AE-NSVM is computed as follows:

where is a scalar between 0 and 1, the optimal is determined by tuning on a development set, and is the reconstruction error for each view.

3.4. Theoretical Complexity Analysis

To further validate the efficiency of the proposed framework, this section theoretically compares the spatial complexity and temporal complexity of three multi-view models: the proposed AE-NSVM, the pipeline-based AE-SVM, and the baseline multi-view-DNN (MV-DNN). The AE-NSVM architecture consists of V view-specific encoders and V symmetric decoders. A hinge loss layer directly connected to the bottleneck layer performs classification, enabling joint optimization of AE reconstruction loss and SVM hinge loss. The AE-SVM contains a multi-view AE that is identical to the AE part of AE-NSVM, as well as a independent SVM classifier. The MV-DNN is a multi-view deep neural network (multiple inputs) containing a multiple inputs layer, a concatenation layer, and a softmax layer.

3.4.1. Spatial Complexity

Spatial complexity is defined as the total number of trainable parameters, and it is derived from model components, such as encoders, decoders, fusion layers, and classifiers. Equation (13) describes the spatial complexity of AE-NSVM, defined as the total number of trainable parameters:

where V denotes the number of views, represents the parameters of a one view-specific encoder, is the parameters of a one view-specific decoder, B denotes the bottleneck layer parameters, and is the parameters of the hinge loss classifier.

Equation (14) describes the spatial complexity of AE-SVM, including parameters of the multi-view AE and independent SVM:

where , and B are defined identically to AE-NSVM, and denotes the parameters of the independent SVM classifier.

Equation (15) describes the spatial complexity of MV-DNN, excluding decoder parameters as follows:

where V is the number of views, represents the parameters of a one view-specific DNN encoder, F denotes the concatenation layer parameters, and is the parameters of the softmax classifier.

From Equations (13) and (14), we can see that AE-NSVM exhibits lower spatial complexity than AE-SVM, primarily due to the end-to-end integration of classification into the AE framework. Both models share identical multi-view AE components, but their classification modules differ fundamentally. AE-NSVM replaces AE-SVM’s independent SVM with a lightweight hinge loss layer. The SVM’s large parameter count stems from its support vector coefficients, which scale with dataset size, whereas the hinge loss layer uses fixed-size linear weights achieving parameter efficiency without sacrificing discriminative power. AE-NSVM has slightly higher spatial complexity than MV-DNN, which is attributed to its multi-view decoders. MV-DNN omits decoders entirely, relying solely on encoders and softmax layers for classification.

3.4.2. Temporal Complexity

Temporal complexity is measured by floating-point operations (FLOPs) during training and inference, with N as the sample size, T as the training epochs, and B as the batch size. Equations (16–18) describe the training complexity (FLOPs) of the three models:

where T is the training epochs, N is the sample size, B is the batch size, is the encoder/decoder FLOPs, denotes the bottleneck FLOPs, and denotes the hinge loss FLOPs.

where denotes SVM quadratic programming complexity.

where is the DNN encoder FLOPs per view, is the concatenation layer FLOPs, and denotes the softmax FLOPs.

Equations (16–18) indicate that AE-NSVM balances efficiency and modularity, outperforming AE-SVM in large-scale scenarios (no bottleneck) and MV-DNN in classification layer efficiency (hinge loss < softmax). Its decoder overhead is offset by end-to-end optimization, making it the most practical choice for multi-view intrusion detection.

Inference complexity focuses on forward propagation, which is critical for real-time applications. For the three models, the inference FLOPs are derived as follows.

During inference, AE-NSVM omits decoders, retaining only encoders, the bottleneck, and hinge loss layers. Its inference complexity is given by Equation (19):

where N is the inference sample size, is the total FLOPs of a view-specific encoder, and is the FLOPs of the hinge loss inference.

AE-SVM requires AE feature extraction followed by independent SVM inference, leading to higher latency. Its inference complexity is expressed as Equation (20):

where N, , and are defined as above, and is the FLOPs of the SVM inference.

MV-DNN performs full forward passes through DNN encoders, concatenation, and FC layers during inference. Its inference complexity is given by Equation (21):

where N, , , and are defined identically to training complexity.

Compared to AE-SVM, AE-NSVM offers a critical advantage in training efficiency by eliminating the high-complexity term associated with independent SVM training (due to quadratic programming), instead integrating a lightweight end-to-end hinge loss layer that avoids such exponential complexity. In contrast to MV-DNN, AE-NSVM achieves superior inference efficiency by omitting decoders during deployment, retaining only encoders and the hinge loss layer. The hinge loss layer further accelerates inference with its linear operation, making AE-NSVM faster and more scalable for real-time intrusion detection tasks.

3.5. Federated Learning

Federated learning offers the advantage of training machine learning models with decentralized data sources while preserving data privacy. By allowing participants to collaborate and contribute their local knowledge without sharing raw data, federated learning ensures confidentiality while improving model accuracy and adaptability. This approach enables scalable and efficient training, making it ideal for intrusion detection.

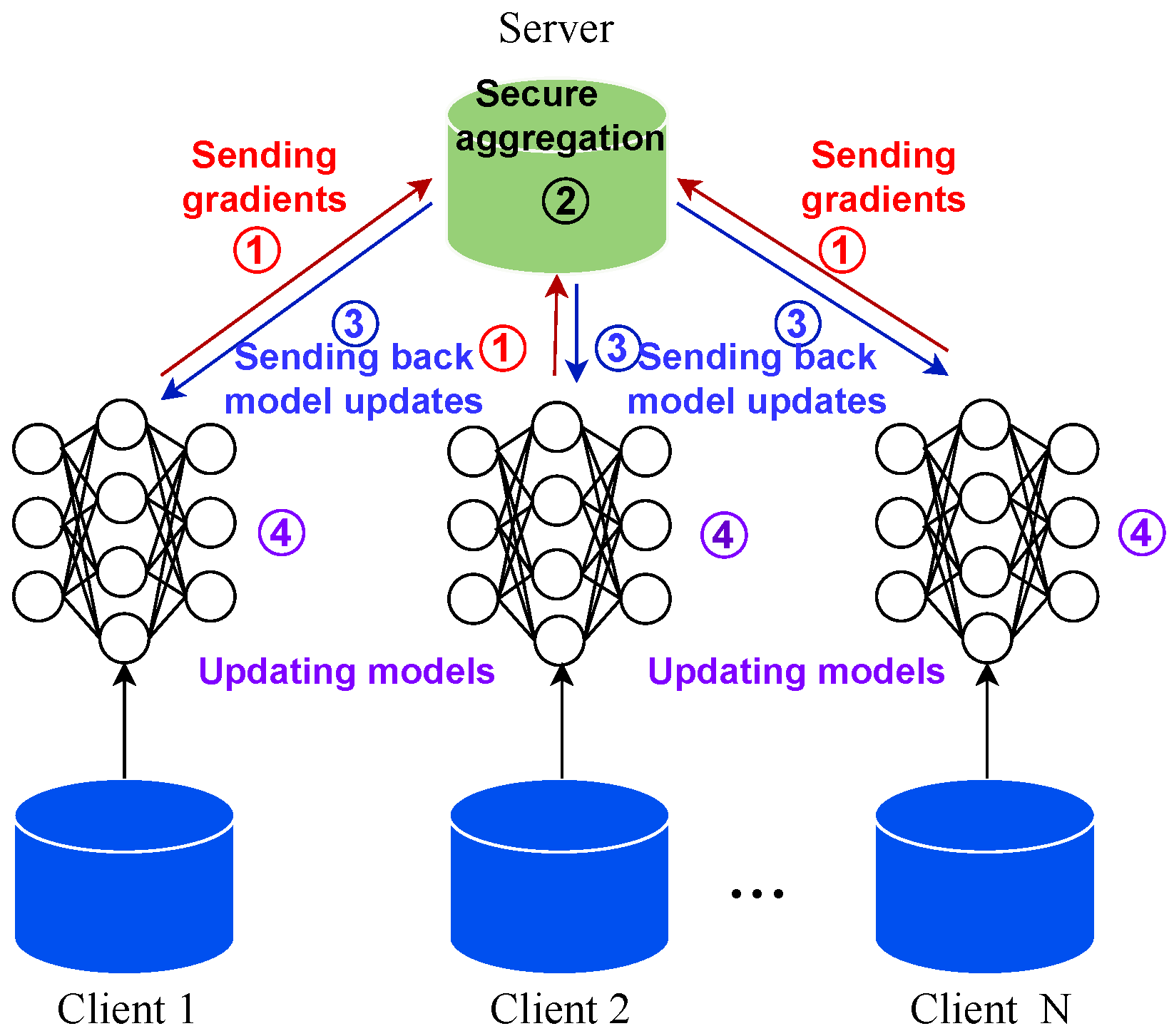

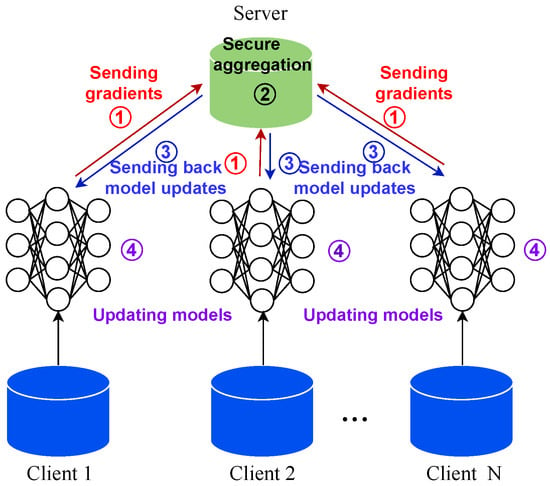

Figure 4 is the proposed architecture of AE-NSVM for federated learning. Assuming there are n clients denoted as , FL includes the following five steps:

Figure 4.

The federated learning architecture.

- A global model G is initialized on the centralized server;

- The parameters of global model G are sent to each client;

- Each client fine tunes the global model on its local data to obtain the updated model ;

- The parameters of the updated model are sent back to the server and aggregated to form a new global model;

- The process from Step 2 to Step 4 is iterated until the convergence or iteration number T is reached.

For n clients, federated learning aims to optimize the following equation:

where f is the global optimization objective, is the parameters of local model , and is the objectives defined by the local client .

To solve the federated optimization problem, model is trained on local client to find a optimized , and then is sent to the server for aggregation with algorithm (FedAvg [42] in this paper) to obtain the global parameter :

The global parameter is then distributed to clients as its new . Each client trained its corresponding local model with this new . The clients and server repeat these processes until converges to or the iteration number T is reached.

converging to means the value of approaches infinitely, which can be described by the following equation:

where is the overall difference between and their average .

Furthermore, each objective is the optimization for the loss function from Equation (12) using an algorithm such as SGD (stochastic gradient descent).

4. Experimental Set-Up

4.1. Dataset

We evaluated the proposed method on three datasets: TON_IoT, UNSW-NB15, and a simulated dataset. Below, we provide detailed descriptions of each dataset.

4.1.1. TON_IoT Windows 10 Datasets

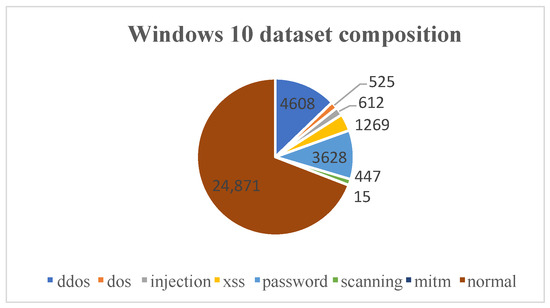

The TON_IoT dataset, introduced by the IoT Lab of UNSW Canberra Cyber, is a new generation of Internet of Things (IoT) and Industrial IoT (IIoT) datasets for AI-based anomaly detection evaluation. It integrates heterogeneous data sources, including IoT/IIoT sensors, Windows/Ubuntu operating systems, and network traffic. The datasets collect seven cyber-attack events for IoT networks, including scanning, Denial-of-Service (DoS), DDOS, password, injection, Cross-Site Scripting (XSS), Man-in-the-Middle (MITM) attacks, and normal events. Due to the authenticity and diversity of TON_IoT datasets, it has become a commonly used benchmark dataset for intrusion detection tasks in recent years. In this paper, we evaluate the proposed approach on the Windows 10 dataset in TON_IoT, containing five views that describe the host activities from various aspects.

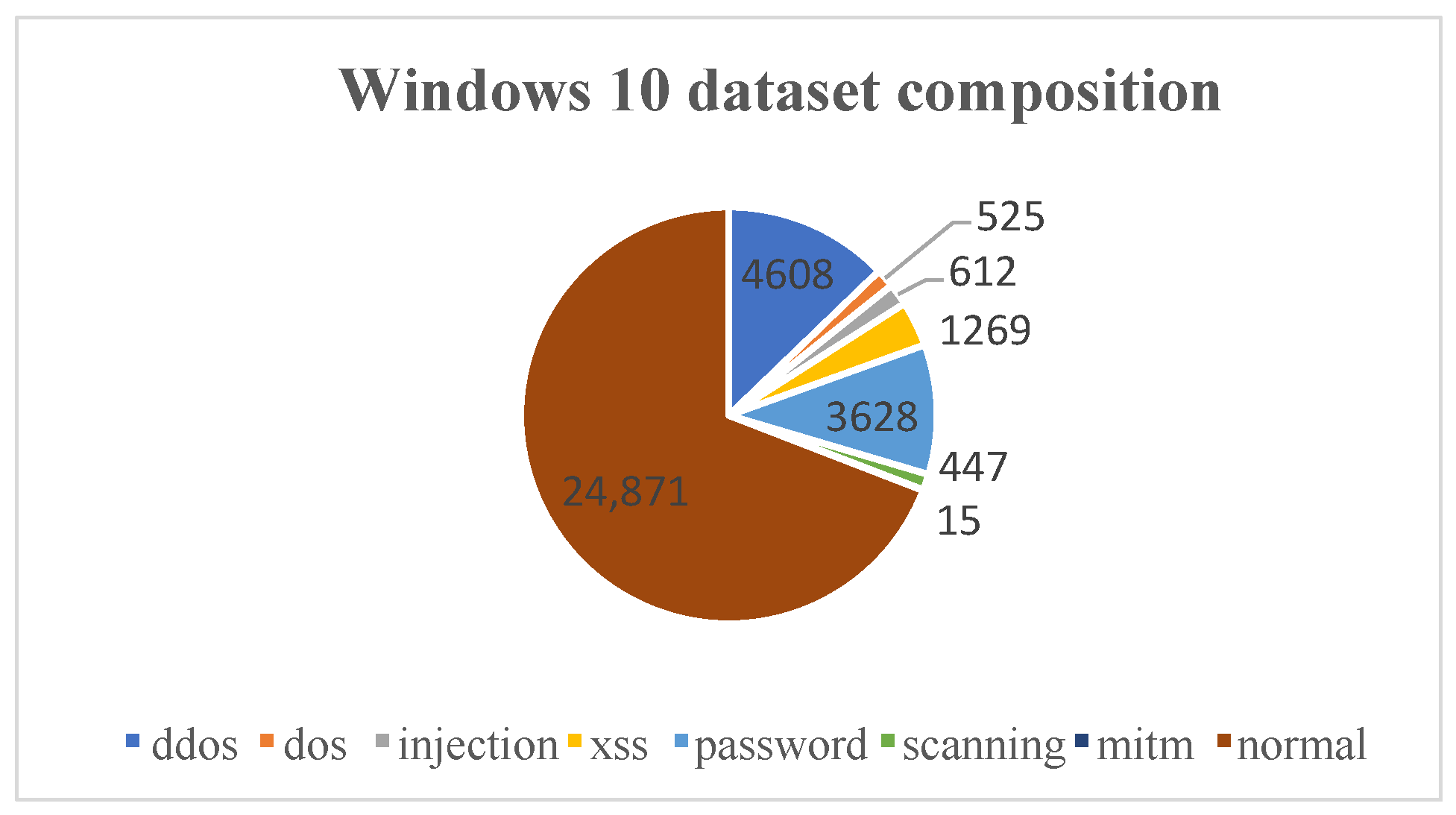

The Windows 10 dataset was collected from multiple sources, including the memory, process, processor, and hard drive of the system, using a Windows 10 virtual machine. The various sources describe the host status or events that happened from different views in a specific time, and they can be used together to improve the accuracy of the learning model. Table 1 provides an illustrative example of the various attributes pertaining to processor activity, such as time stamps, the rate at which a processor receives and services deferred procedure calls (DPCs), idle time, and the rate at which the processor enters a deep sleep state.The dataset under analysis contains a total of 35,975 records, encompassing both normal and attack observations. The attack instances have been classified into several different types, as detailed in Figure 5. Furthermore, the information between the five views can be combined and used simultaneously according to the timestamp feature, which uniquely identifies a specific time in a Windows system. In addition, Figure 5 shows the class imbalance in the dataset, particularly for underrepresented classes with limited samples, like MITM and scanning. To address this problem, we employed weighted sampling during training using WeightedRandomSampler, which assigns higher sampling probabilities to minority classes to balance their representation in mini-batches.

Table 1.

Description of processor activities.

Figure 5.

The statistics of the Windows 10 dataset.

4.1.2. UNSW-NB15 Dataset

Besides TON_IoT, we also carried out experiments on the UNSW-NB15 dataset. The UNSW-NB15 dataset [43], created in 2015, captures both normal and attack behaviors in modern real-time network traffic. UNSW-NB15 employs a hybrid generation approach: utilizing the IXIA PerfectStorm tool with two IXIA traffic generator servers—one simulating authentic modern normal network activities, while the other generates synthetic contemporary attack behaviors. These network behaviors were, subsequently, captured using the tcpdump tool to form traffic records. The UNSW-NB15 dataset comprises 43 features, which are primarily categorized into three groups (as shown in Table 2): basic features, content features, and traffic features. The basic features characterize protocol connection attributes, including service types and protocol states. The content features primarily describe the attributes of TCP/IP protocols. The temporal and additional generated features that mainly capture the traffic information of TCP connections, such as the timing characteristics of packets and TCP protocols, as well as the matched statistical metrics within specific time windows. We treat each feature group as a distinct view and validate the proposed multi-view fusion approach on this dataset.

Table 2.

Feature groups in the UNSW-NB15 dataset.

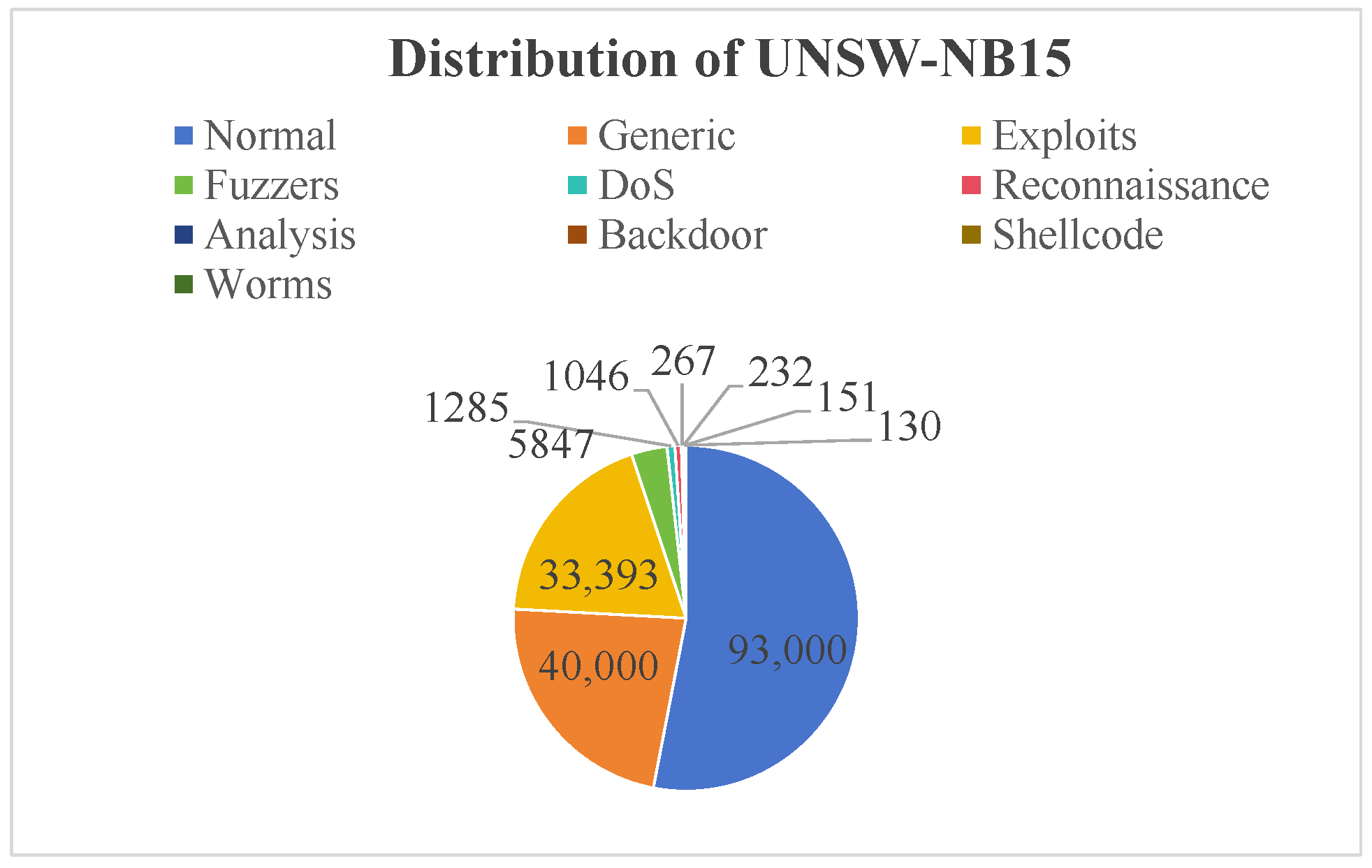

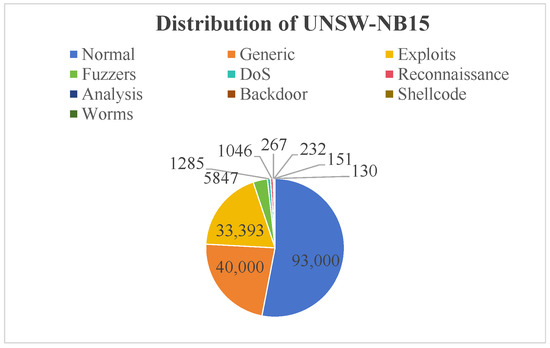

Figure 6 illustrates the class distribution in the UNSW-NB15 training set (175,341 records). Normal network traffic accounts for 53.04% (93,000 samples), while attack categories comprise 46.96% of the data. The majority of attacks are Generic (22.81%) and Exploits (19.04%), with the remaining minority attack classes collectively representing just 5.11%.

Figure 6.

The distribution of UNSW-NB15.

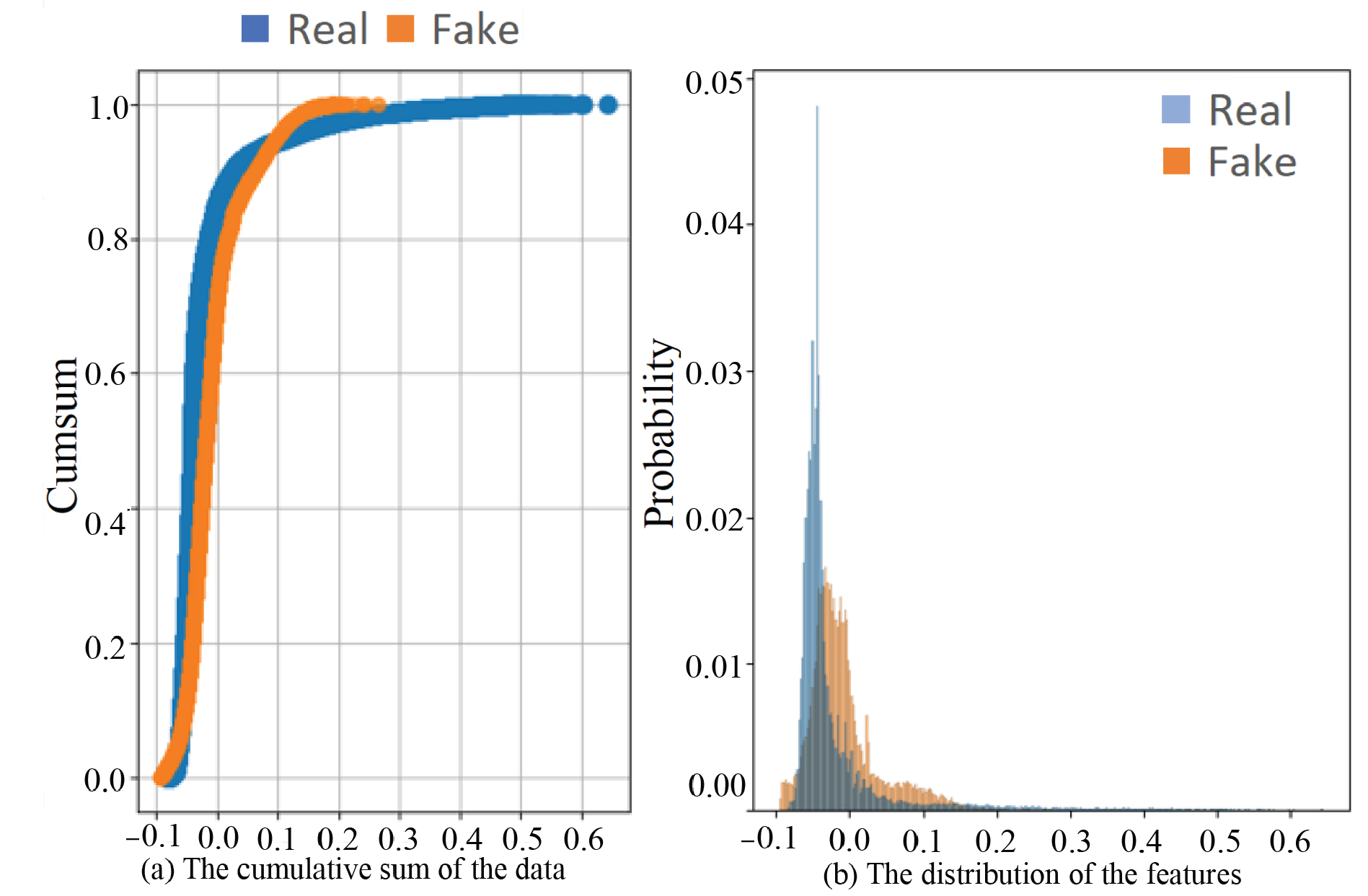

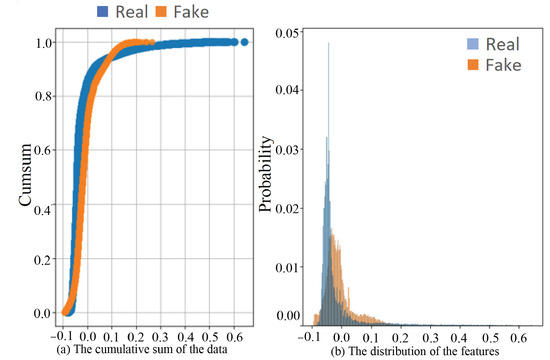

4.1.3. Synthetic Dataset

Synthetic data can increase data diversity and availability, which is a crucial factor for proving the effectiveness of the proposed approach. Furthermore, we can simulate IoT data for multiple clients to enable federated learning. Thus, we created a simulated dataset using generative adversarial networks (GANs) according to [44] based on TON_IoT. Figure 7 shows the quality of the generated data compared with TON_IoT. Figure 7a compares the trends in the real and fake data by the cumulative sum of the data in each dataset. The high consistency of the curve demonstrates the similarity between the generated data and the original data. Figure 7b shows the probability distribution of each feature in both the simulated and original dataset. The x-axis represents the index of features, and the y-axis represents the frequency of the corresponding feature. The blue and red are the TON_IoT and generated data, respectively. From Figure 7b, we can see that the trends of simulated data follow that of the real data very closely, which indicates a high similarity between the simulated and real data.

Figure 7.

The statistics of the Windows 10 dataset.

4.1.4. Feature Generation and Analysis

Feature pre-processing is an important step for machine learning tasks to improve the quality of the data, and it also improves the efficiency and accuracy of the learning model. We retrieved data from the five views of the TON_IoT dataset and conducted preprocessing operations. Specifically, we removed the columns with missing values and, subsequently, performed standardization and normalization on the data along both the rows and columns. This ensured that the different features of the data were given distinct weights and each sample followed a standard normal distribution with a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1.

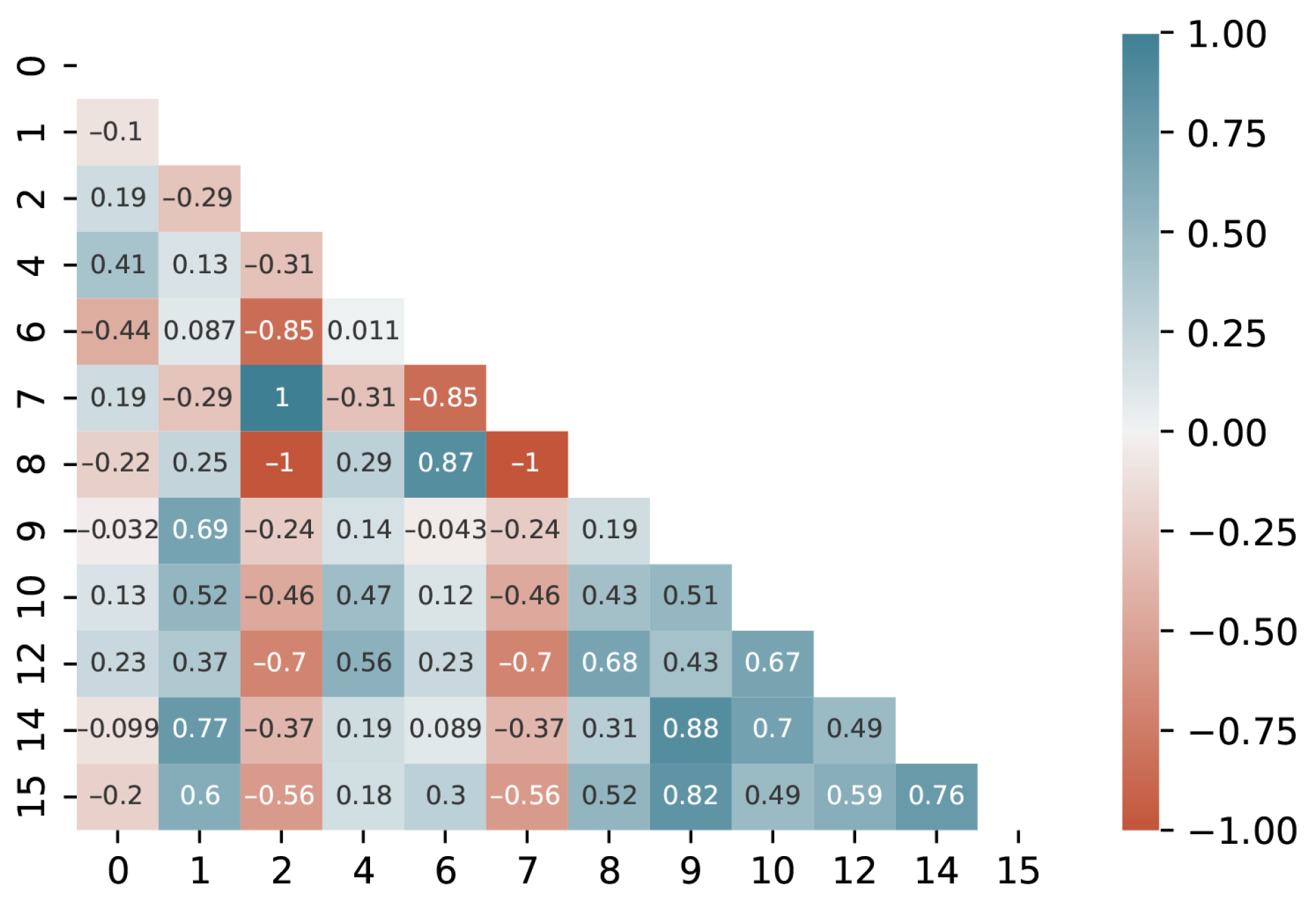

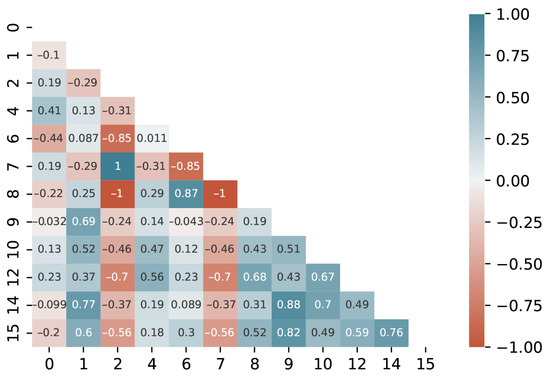

The analysis of the feature correlation helps to identify the redundancy in highly correlated features that can be removed to reduce the dimension of the data, thereby simplifying the model and improving its performance. Figure 8 shows the correlations between the features from processor activities. The x-axis and y-axis are the index of features, and the number in the figure represents the value of the correlation between two features. A higher value indicates that more redundant information was included in both features and that one of them can be abandoned. From this figure, we can see most of the values were lower than 0.8, which indicates a good discrimination of the features generated from processor activities. Using the same approach, we conducted feature analysis on the domains of memory, disk, process, and network, respectively, and we also removed redundant columns. The remaining features were used as the training database for the neural network. This process helped improve the accuracy, efficiency, and interpretability of the model.

Figure 8.

The correlations between the features generated from the processor activities.

4.2. Model Training

Our experiments consisted of three main parts.

- Pipeline: Different AEs are used to learn the feature representations of the data in a hidden semantic space, and then the SVM classification method is used to classify the extracted features.

- Joint learning: Feature generation and intrusion detection is integrated into a single neural network, allowing feature generation and classification to have the same optimization function, and it also improves the classification performance of the model;

- Federated learning: The proposed model is applied to multiple clients and the federated learning approach is utilized to enable parameter learning of the proposed model on multiple clients, testing the intrusion detection performance of the model in a distributed environment.

For the AEs, we investigated the performance of a standard auto-encoder (AE), variational auto-encoder (VAE), convolutional auto-encoder (CAE), and denoising auto-encoder (DAE) in the pipeline and proposed end-to-end approaches.

For the neural networks, we initialized the learning rate to and decreased it by a decay rate of . The value of the momentum was set to . To mitigate overfitting during model training, an early stopping strategy was employed. Specifically, the patience parameter was set to 10, allowing a maximum of 10 consecutive epochs without improvement in validation performance, and the minimum threshold for significant improvement (delta) was specified as . The dropout rate was set to . We used an L2 regularizer and set the value to 3 × . Then, 5-fold cross-validation was adopted to ensure model stability across different data splits, validating its robustness and reducing sensitivity to dataset bias. The GPU of an NVIDIA A100 with 40 GB high-speed HBM2 memory (sourced from NVIDIA Corporation, located in Santa Clara, United States of America) was used to accelerate the training process.

4.3. Evaluation Metrics

The F1-measure is a commonly used metric in machine learning and statistics, particularly in classification tasks. It strikes a balance between precision (the ability to correctly classify positive instances) and recall (the ability to find all positive instances). In imbalanced datasets, accuracy can be misleading because it can be high simply due to the dominant class, while the model may perform poorly on the minority class. The F1-measure considers both false positives and false negatives, making it a robust metric in such scenarios. Thus, in our study, we used the F1-measure to evaluate the intrusion detection performance. The predicted classes were compared to the ground truth classes. Precision was defined as the percentage of declared classes that coincide with the referenced classes. Recall was defined as the percentage of referenced classes that are retrieved. The F1-measure was defined as follows:

4.4. Results

As Section 4.2 mentioned, our experiments included three parts. First, we fused the five views and generated the cybersecurity-related features using four kinds of auto-encoders: standard AE, Denoised AE, Variational AE, and Convolutional AE. The generated features were then fed into an SVM to classify the sample into a normal or into seven other kinds of attacks. Second, we linked an SVM to the AE to jointly learn the representation of the five views, and we classified the sample based on the fused feature. Finally, we employed the proposed approach in a distributed environment, utilizing the federated learning approach to learn the model parameters and evaluate the intrusion detection performance in the distributed setting.

4.4.1. Results of the Pipeline Systems on TON_IoT

In this part, we analyze the results of pipeline systems (separated feature fusion and classification). First, we obtained the classification results on the original features and fused features using the SVM algorithm. The original features were obtained by simply concatenating the features from the five different views. The fused feature was obtained from a standard AE with two hidden layers and one bottleneck layer. After training, the fused feature was derived from the bottleneck layer and fed into an SVM. Table 3 shows the results of the SVM on original features and fused features. We obtained a of F1 for the fused feature, which is higher than the results on the original feature, indicating the effectiveness of the fusion process of the AE.

Table 3.

The precision, recall, and F1-score of AE-SVM with the original and fused features.

We also investigated the effects of the kernel function and penalty parameter (C) on the SVM classifier. In scikit-learn, we set ’gamma’ to ’scale’ to automatically determine its value based on feature variance, and ’class weight’ was set to ’balanced’ to automatically balance the class distribution. Table 4 shows the classification results of the different kernels and the penalty parameter C in terms of F1-score. For the polynomial kernel, we set the degree to 3.

Table 4.

The classification results of the different kernels and penalty parameter C on the F1-score.

We also analyzed the classification performance on eight classes, as Table 5 shows. MITM and scanning had very low F1-measures of 0 and . By observing the training data, we found that poor performance was caused by the small number of samples corresponding to the classes in the training data.

Table 5.

The precision, recall, and F1-score of the AE-SVM model under different attack types on the TON_IoT dataset.

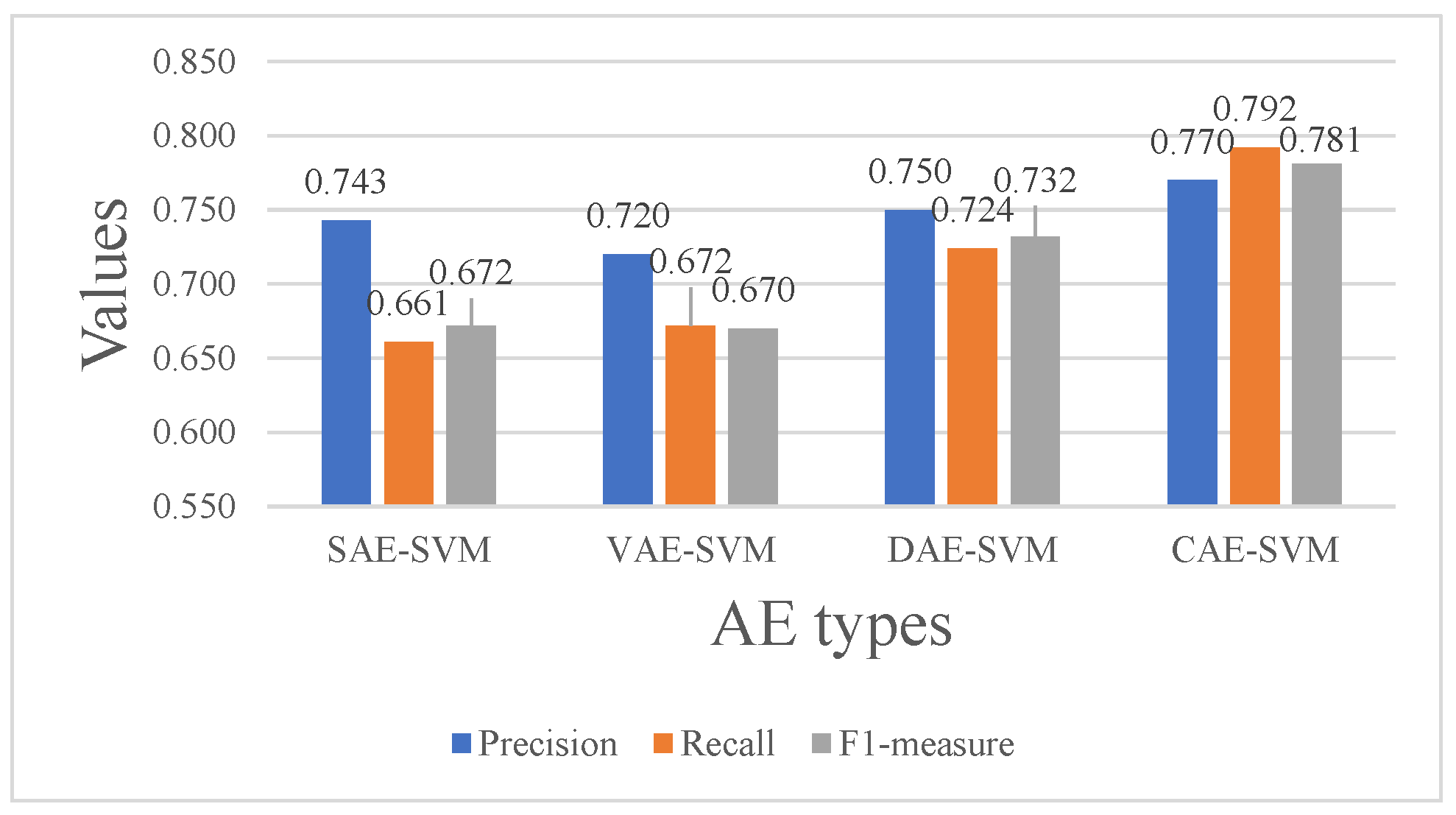

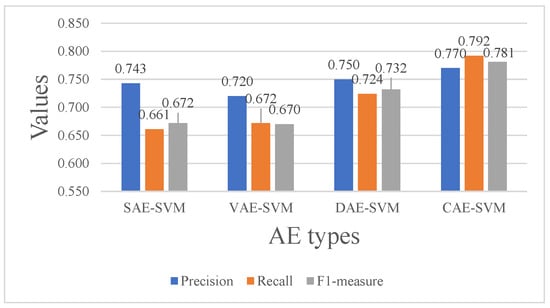

We implemented four kinds of AE, i.e., SAE, VAE, DAE, and CAE, to fuse the features from five views, and the extracted features were then fed into an SVM classifier. The dimensions of the five views were 16D (processor view), 28D (process view), 22D (network view), 36D (memory view), and 23D (disk view). View-specific encoders independently mapped raw features to 16-dimensional latent vectors, which were then concatenated to form an 80-dimensional combined vector. In the decoding phase, the fused feature is first mapped back to a 16-dimensional vector, which is subsequently decoded into the original dimensions of each input view. For VAE, we assumed the data followed a standard multivariate Gaussian distribution, which the features were sampled from. In DAE, we added two kinds of noise, Gaussian noise and Speckle noise, to the training data in the same proportion. In CAE, we used five kernels with a size of three in the convolution layer, and maxpooling was used for downsampling. From Figure 9, we can see that CAE obtained the best performance with an F1-measure of , which is 16.2% higher than that of SAE. The VAE obtained the lowest value of F1-measure, which may have been caused by the complex data distributions and the lack of spatial structure compared to the tasks in computer vision.

Figure 9.

The precision, recall, and F1-score of the different AE types combined with SVMs on the TON_IoT dataset.

4.4.2. Results of AE-NSVM on TON_IoT

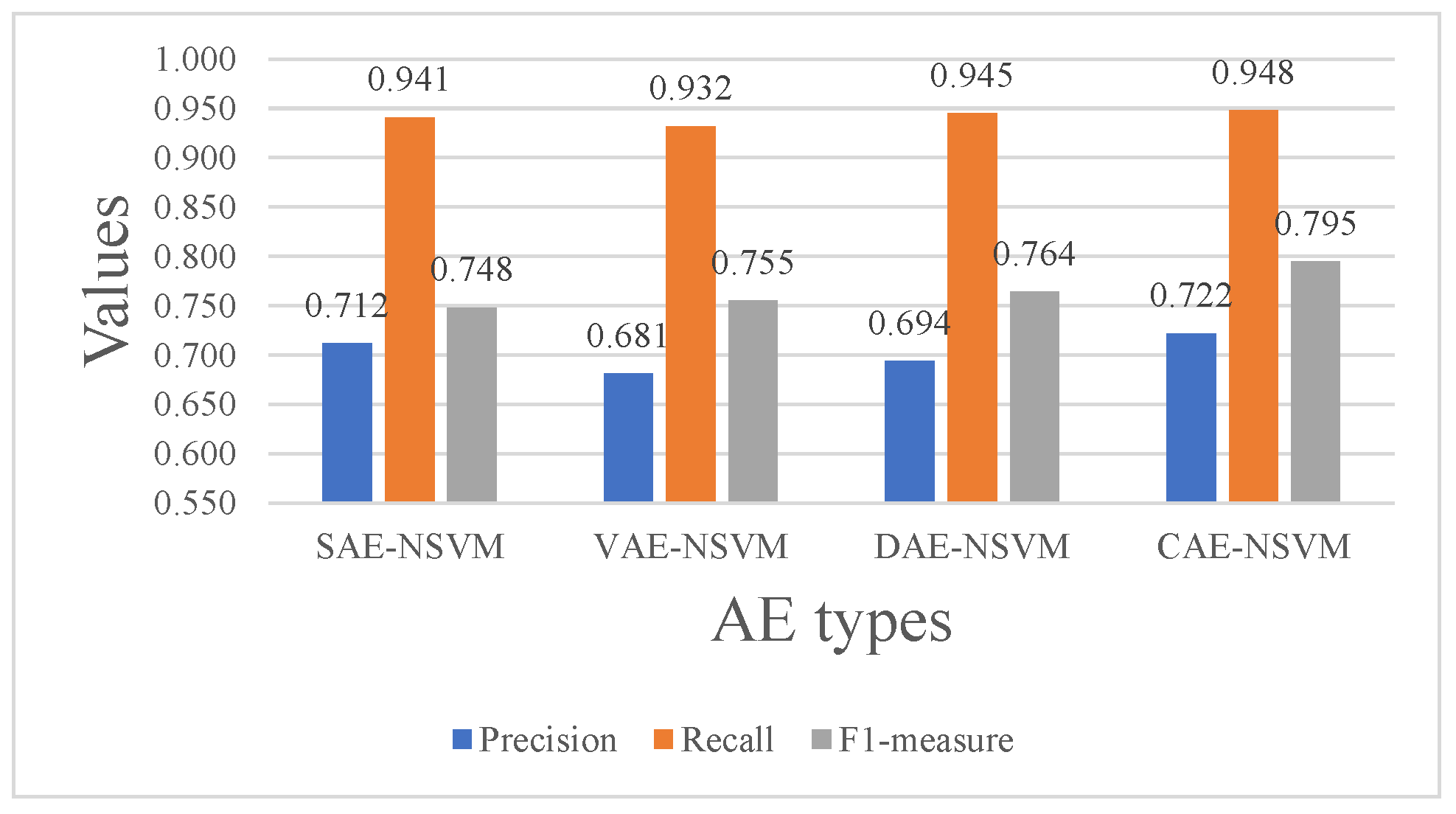

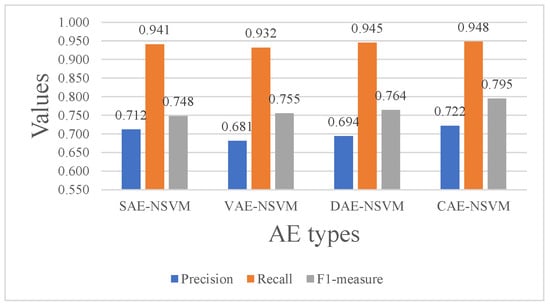

Figure 10 shows the results of AE-NSVM that were optimized by classification loss and AE reconstruction loss with a loss weight, which was tuned as a parameter. After tuning, we set the value of the loss weight of each view to , and the value of the classification loss weight was set to . Compared with Figure 9, we first found that the approach based on joint training achieved better performance than the corresponding pipeline system, and CAE-NSVM obtained the highest F1-measure of , which is higher than the results of pipeline system (). Second, approaches using joint training obtained higher recall values than the pipeline system, such as, for example, and in SAE, and in VAE, and in DAE, and and in CAE, which means the model was correctly identifying a high proportion of relevant instances within the dataset. In other words, it indicates that the model has a low false negative rate, i.e., it correctly identifies a large number of positive cases from all the actual positive cases present in the data. This demonstrates the effectiveness of the proposed joint training-based approaches.

Figure 10.

The precision, recall, and F1-score of the AE-NSVM models on the TON_IoT dataset.

To demonstrate the effectiveness of the five-view feature fusion, we conducted ablation tests to evaluate the individual views using the CAE-NSVM framework. Table 6 shows that the highest F1-score was obtained for the memory view, which contained the highest-dimensional original vector, suggesting richer information content. Notably, the fused features outperformed all individual views, validating the proposed fusion method.

Table 6.

The precision, recall, and F1-score of CAE-NSVM in the individual views.

4.4.3. Results on UNSW-NB15

We evaluate the proposed model performance on the UNSW-NB15 dataset across four metrics: model size, convergence time, inference time, and F1-score. Params (k) represents the model size, measured by the total number of trainable parameters; denotes the convergence time, defined as the total time (in seconds) required for the network model to reach a stable state during the training process; and refers to the inference time, indicating the average time (in seconds) taken by the trained model to process samples and generate an output prediction on the test dataset. These metrics collectively assess the model’s efficiency and effectiveness. The CAE-NSVM and CAE-DNN models share a common CAE architecture consisting of three main components. The encoder processes three input channels (13, 8, and 21 nodes) through parallel one-dimensional convolutional (Conv1D) layers (16 filters, kernel size = 3), and it then concatenates and compresses the outputs into a 50-node bottleneck layer via a 96-node feature vector. The decoder reconstructs the original inputs using five parallel Conv1D layers with identical specifications. For classification, a 30-node dense layer connects to the bottleneck, followed by either a hinge loss output layer for CAE-NSVM or a softmax classification layer for CAE-DNN.

The MV-DNN architecture processes its three input channels through 32-node embedding layers before concatenation into a 96-node feature vector, which is then fed through two hidden layers for classification. Its variant, MV-CNN, follows the same structure but replaces each embedding layer of the three channels with a Conv1D layer.

As shown in Table 7, the experimental results on the UNSW-NB15 dataset demonstrate that CAE-NSVM achieves a striking balance between performance and efficiency: with the same parameter count as CAE-DNN (12.3k), CAE-NSVM delivers a marginally higher F1 score (0.829 vs. 0.827) while significantly reducing training time by 73% (9.2 s vs. 34.2 s) and inference time by 89% (0.7 s vs. 6.2 s); compared to MV-DNN, which has fewer parameters (7.1k) and a slightly higher F1 score (0.830), CAE-NSVM achieves comparable performance with 59% faster training (9.2 s vs. 22.5 s) and 89% faster inference (0.7 s vs. 6.2 s); and although MV-CNN exhibits the highest F1 score (0.856) with the fewest parameters (6.5k), CAE-NSVM offers substantially faster training (9.2 s vs. 28.2 s) and inference (0.7 s vs. 5.5 s), making it a more practical choice for real-world deployment scenarios requiring efficient computation.

Table 7.

Comparison of the model parameters, latency, and F1-score on the UNSW-NB15 dataset.

4.4.4. Results of FL

In practical application scenarios, there are multiple clients in the network, and traditional machine learning algorithms face limitations, such as physical data access, high computational cost, and privacy issues. Federated learning can improve the model generalization ability and obtain better data representation while protecting data privacy. This paper extends the proposed CAE-NSVM method to a distributed environment, using federated learning algorithms to learn the model parameters. We randomly allocated the dataset to three clients and constructed a federated learning platform using the Flower toolkit [46]. We supplemented the experimental results of the individual views under the federated learning framework and further validated the superiority of the multi-view fusion by contrasting with single-view strategies.

We first employed the FedAvg method from [42] to evaluate the federated learning performance on the individual views of the TON_IoT and UNSW-NB15 datasets, with results shown in Table 8 and Table 9. Each of the results were acquired after eight rounds of federated learning processes, and for each round, the local models were trained for 30 epochs. As presented in Table 8, the memory view achieved the highest F1-score of 0.770 (Recall = 0.935), while the processor view yielded the lowest F1-score of 0.682. Notably, the network view balanced precision (0.716) and recall (0.694) with an F1-score of 0.705, but no single view exceeded 0.770. Table 9 shows that the traffic view outperformed others with an F1-score of 0.821 (precision = 0.797, recall = 0.847), followed by the basic view (F1 = 0.817) and content view (F1 = 0.802). Even the best single view (traffic) only reached 0.821, indicating limited performance gain from the isolated feature modalities.

Table 8.

The precision, recall, and F1-score of the federated learning across the individual views on the TON_IoT dataset with three clients.

Table 9.

The precision, recall, and F1-score of the federated learning across the individual views on the UNSW-NB15 dataset with three clients.

To demonstrate the advantage of the multi-view fusion, we implemented experiments on both the TON_IoT, the TON_IoT augmented dataset (TON_IoT +synthetic, abbreviated as TON_IoT+S), and UNSW-NB15 with multiple views. The reason for using the synthetic data was to increase the data volume to validate algorithm effectiveness. The first row shows the results that were obtained when onlt using the original TON_IoT dataset, while the second row details outcomes after integrating the generated data—where the synthetic samples were evenly split into three parts and mixed with each client’s original TON_IoT data. This approach directly increased the per-client data volume, enabling us to verify that the algorithm maintained stable performance when scaled to larger, more realistic federated learning scenarios. The results are shown in Table 10.

Table 10.

Comparison of the precision, recall, and F1-score for CAE-NSVM across the TON_IoT, TON_IoT + synthetic, and UNSW-NB15 datasets with three clients.

First, we compared the proposed multi-view federated learning model against the single-view federated learning results. On the TON_IoT dataset, the multi-view CAE-NSVM achieved an F1-score of 0.790, which is 2.6% higher than the best single view (memory 0.770, as shown in Table 8). This performance gain arises from integrating the complementary features across heterogeneous views: for example, the memory view contributed high recall (0.935) to capture most attack instances, while the network view provided balanced precision (0.716) to reduce false positives, collectively enhancing discriminative power. On the UNSW-NB15 dataset, the multi-view model’s F1-score of 0.826 exceeded the best single view (traffic, 0.821, as shown in Table 9) by 0.5%. This validates that fusing diverse feature modalities—basic (protocol attributes), content (payload information), and traffic (connection metrics)—enables the model to capture richer intrusion patterns that are overlooked by isolated single-view approaches.

Second, we contrasted the federated learning performance with centralized training baselines. On both the TON_IoT and UNSW-NB15 datasets, the federated multi-view model yielded marginally lower F1-scores compared to the centralized training (e.g., 0.790 vs. 0.792 on TON_IoT). However, federated learning ensures strict data privacy preservation by avoiding raw data sharing across clients, while maintaining competitive generalization ability. This balance addresses the critical privacy–accuracy trade-off in distributed intrusion detection systems, where centralized methods risk data leakage and fail to scale to real-world decentralized environments.

5. Conclusions and Future Work

This paper proposes a multi-view federated learning approach for intrusion detection. To leverage multiple data sources, we used AE with multiple inputs, learning a better feature representation to improve the performance of the intrusion detection system. Unlike the pipeline system containing separated feature learning and classification processes, we linked a neural SVM layer to AE and jointly trained them together so that the two processes have the same optimization function, which could improve the performance of the system. In addition, incorporating neural SVM into the AE training process can help in learning the hidden information of intrusion classes. The experiments were conducted on multiple clients with a federated learning strategy on the TON_IoT dataset and show the effectiveness of the proposed approach. In the future, we plan to investigate hierarchical intrusion detection approaches on client–edge–cloud frameworks.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.L. and J.Y.; methodology, J.Y., B.L. and G.W.; software, J.Y. and R.S.; validation, J.Y., N.S. and R.S.; formal analysis, J.Y. and B.L.; investigation, B.L.; resources, N.S. and G.W.; data curation, J.Y. and R.S.; writing—original draft preparation, J.Y.; writing—review and editing, B.L.; visualization, R.S. and G.W.; supervision, B.L.; project administration, B.L.; funding acquisition, B.L. and G.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This publication arose from the research conducted in the Confirm Centre for Smart Manufacturing with the financial support of Science Foundation Ireland (SFI) under Grant Number SFI/16/RC/3918. It was also co-funded by the European Regional Development Fund and the Science and Technology Breakthrough Project of Henan Science and Technology Department under Grant Number 232102210065.

Data Availability Statement

TON_IoT dataset is available at: https://research.unsw.edu.au/projects/toniot-datasets (accessed on 27 May 2025); UNSW-NB15 dataset is available at: https://research.unsw.edu.au/projects/unsw-nb15-dataset (accessed on 27 May 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Prümmer, J.; van Steen, T.; van den Berg, B. A systematic review of current cybersecurity training methods. Comput. Secur. 2024, 136, 103585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitney, A.M.; Penrod, S.; Foraker, M.; Bhunia, S. A systematic review of 2021 microsoft exchange data breach exploiting multiple vulnerabilities. In Proceedings of the 2022 7th International Conference on Smart and Sustainable Technologies (SpliTech), Split/Bol, Croatia, 5–8 July 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Saleh, A.M.S. Blockchain for secure and decentralized artificial intelligence in cybersecurity: A comprehensive review. Blockchain: Res. Appl. 2024, 5, 100193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, A.; Rawat, P.; Vats, S.; Sharma, V. Heatmap-Based Deep Learning Model for Network Attacks Classification. SN Comput. Sci. 2024, 5, 1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wei, D.; Feng, J. Network attacks detection methods based on deep learning techniques: A survey. Secur. Commun. Netw. 2020, 2020, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Bao, T.; Qi, W.; You, D.; Liu, L.; Shen, L. Poisoning QoS-aware cloud API recommender system with generative adversarial network attack. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 238, 121630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maniriho, P.; Mahmood, A.N.; Chowdhury, M.J.M. A study on malicious software behaviour analysis and detection techniques: Taxonomy, current trends and challenges. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2022, 130, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Admass, W.S.; Munaye, Y.Y.; Diro, A.A. Cyber security: State of the art, challenges and future directions. Cyber Secur. Appl. 2024, 2, 100031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaba, F.A.; Othman, M.; Hashem, I.A.T.; Alotaibi, F. Internet of Things security: A survey. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2017, 88, 10–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, A.I.; Babu, A.; Barka, E.; Shuaib, K. AI-powered biometrics for Internet of Things security: A review and future vision. J. Inf. Secur. Appl. 2024, 82, 103748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupanetti, D.; Kaabouch, N. Combining edge computing-assisted internet of things security with artificial intelligence: Applications, challenges, and opportunities. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokila, M.; Reddy, S. Authentication, access control and scalability models in Internet of Things Security–A review. Cyber Secur. Appl. 2025, 3, 100057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Chu, Y.M.; Hsieh, T.I.; Chen, H.T.; Liu, T.L. Learning diffusion models for multi-view anomaly detection. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024; pp. 328–345. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, L.; Peng, S.J.; Liu, X.; Chen, Y.; Cao, J. Multi-view anomaly detection via hybrid instance-neighborhood aligning and cross-view reasoning. Multimed. Syst. 2024, 30, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravi, V.; Alazab, M.; Selvaganapathy, S.; Chaganti, R. A Multi-View attention-based deep learning framework for malware detection in smart healthcare systems. Comput. Commun. 2022, 195, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomio, R.L.; Viegas, E.K.; Santin, A.O.; dos Santos, R.R. A multi-view intrusion detection model for reliable and autonomous model updates. In Proceedings of the ICC 2021—IEEE International Conference on Communications, Virtual, 14–23 June 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, S.T.; Busby-Earle, C. Multi-perspective machine learning a classifier ensemble method for intrusion detection. In Proceedings of the 2017 international Conference on Machine Learning and Soft Computing, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, 13–16 January 2017; pp. 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Mienye, I.D.; Jere, N. A survey of decision trees: Concepts, algorithms, and applications. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 86716–86727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Wang, G.; Li, P.; Wang, H.; Zhang, M.; Liang, X. An improved random forest based on the classification accuracy and correlation measurement of decision trees. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 237, 121549. [Google Scholar]

- Daviran, M.; Maghsoudi, A.; Ghezelbash, R. Optimized AI-MPM: Application of PSO for tuning the hyperparameters of SVM and RF algorithms. Comput. Geosci. 2025, 195, 105785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, P.; Sun, Z.; Sun, Z. An improved intrusion detection algorithm based on GA and SVM. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 13624–13631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinola, I.T.; Sun, Y.; Adebayo, I.G.; Wang, Z. Daily peak demand forecasting using pelican algorithm optimised support vector machine (POA-SVM). Energy Rep. 2024, 12, 4438–4448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farnaaz, N.; Jabbar, M. Random forest modeling for network intrusion detection system. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2016, 89, 213–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wali, S.; Farrukh, Y.A.; Khan, I. Explainable AI and random forest based reliable intrusion detection system. Comput. Secur. 2025, 157, 104542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramilarani, K.; Kumari, P.V. Cost based random forest classifier for intrusion detection system in internet of things. Appl. Soft Comput. 2024, 151, 111125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imrana, Y.; Xiang, Y.; Ali, L.; Noor, A.; Sarpong, K.; Abdullah, M.A. CNN-GRU-FF: A double-layer feature fusion-based network intrusion detection system using convolutional neural network and gated recurrent units. Complex Intell. Syst. 2024, 10, 3353–3370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Wu, G.; Wang, W.; Gao, X.; He, A.; Zhang, Z. Applying self-supervised learning to network intrusion detection for network flows with graph neural network. Comput. Netw. 2024, 248, 110495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, C.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Meng, J.; Ma, Y.; Du, S.; Li, Y. A pipeline intrusion detection method based on temporal modeling and hierarchical classification in optical fiber sensing. IEEE Sensors J. 2024, 24, 19327–19335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, F.; Zhou, B.; Xie, X.; Zhang, Z.; Han, J. Localization of underground pipeline intrusion sources using cross-correlation CNN: Application in pile-driving model test. AI Civ. Eng. 2024, 3, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Sun, X.; He, H.; Zhao, G.; He, L.; Ren, J. A novel multimodal-sequential approach based on multi-view features for network intrusion detection. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 183207–183221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Meng, W.; Tan, Z.; Xiang, Y. Design of multi-view based email classification for IoT systems via semi-supervised learning. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2019, 128, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mvula, P.K.; Branco, P.; Jourdan, G.V.; Viktor, H.L. A Survey on the Applications of Semi-supervised Learning to Cyber-security. ACM Comput. Surv. 2024, 56, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hindy, H.; Bayne, E.; Bures, M.; Atkinson, R.; Tachtatzis, C.; Bellekens, X. Machine learning based IoT intrusion detection system: An MQTT case study (MQTT-IoT-IDS2020 dataset). In Proceedings of the Selected Papers from the 12th International Networking Conference: INC 2020; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 73–84. [Google Scholar]

- Attota, D.C.; Mothukuri, V.; Parizi, R.M.; Pouriyeh, S. An ensemble multi-view federated learning intrusion detection for IoT. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 117734–117745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.D.; Marchal, S.; Miettinen, M.; Fereidooni, H.; Asokan, N.; Sadeghi, A.R. DÏoT: A federated self-learning anomaly detection system for IoT. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 39th International Conference on Distributed Computing Systems (ICDCS), Dallas, TX, USA, 7–10 July 2019; pp. 756–767. [Google Scholar]

- Song, X.; Ma, Q. Intrusion detection using federated attention neural network for edge enabled internet of things. J. Grid Comput. 2024, 22, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Wu, Y.; Song, J.; Lu, R.; Li, T.; Zhao, L. DeepFed: Federated deep learning for intrusion detection in industrial cyber–physical systems. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2020, 17, 5615–5624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, E.M.; Saura, P.F.; González-Vidal, A.; Hernández-Ramos, J.L.; Bernabé, J.B.; Baldini, G.; Skarmeta, A. Evaluating Federated Learning for intrusion detection in Internet of Things: Review and challenges. Comput. Netw. 2022, 203, 108661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhong, Y.; Liang, Y.; Ji, R.; Cang, Y. Advanced multimodal deep learning architecture for image-text matching. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 4th International Conference on Electronic Technology, Communication and Information (ICETCI), Changchun, China, 24–26 May 2024; pp. 1185–1191. [Google Scholar]

- Luvembe, A.M.; Li, W.; Li, S.; Liu, F.; Wu, X. CAF-ODNN: Complementary attention fusion with optimized deep neural network for multimodal fake news detection. Inf. Process. Manag. 2024, 61, 103653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdoll, D.; Hamdard, I.; Rößler, L.N.; Geisler, F.; Bayram, M.; Wang, F.; Imhof, J.; de Campos, M.; Tabarov, A.; Yang, Y.; et al. Anovox: A benchmark for multimodal anomaly detection in autonomous driving. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024; pp. 206–223. [Google Scholar]

- McMahan, B.; Moore, E.; Ramage, D.; Hampson, S.; y Arcas, B.A. Communication-efficient learning of deep networks from decentralized data. In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics, PMLR, Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA, 20–22 April 2017; pp. 1273–1282. [Google Scholar]

- Moustafa, N.; Slay, J. UNSW-NB15: A comprehensive data set for network intrusion detection systems (UNSW-NB15 network data set). In Proceedings of the 2015 Military Communications and Information Systems Conference (MilCIS), Canberra, ACT, Australia, 10–12 November 2015; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow, I.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; Xu, B.; Warde-Farley, D.; Ozair, S.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Generative adversarial networks. Commun. ACM 2020, 63, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Qiao, Y.; Lee, B. A Comparative Analysis of Single and Multi-view Deep Learning for Cybersecurity Anomaly Detection. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 83996–84012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseri, M.; Fernandez-Marques, J.; Gao, Y.; Pan, H. Privacy-preserving federated learning using flower framework. In Proceedings of the 30th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Barcelona, Spain, 25–29 August 2024; pp. 6422–6423. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).