Abstract

This article presents the design, implementation, and comparative evaluation of two Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAV)-based architectures for automated road data acquisition and processing. The first system uses Arduino Portenta H7 boards to perform real-time inference at the edge, reducing connectivity dependency. The second employs ESP32-CAM modules that transmit raw data for remote server-side processing. We experimentally validated and compared both systems in terms of power consumption, latency, and detection accuracy. Results show that the Portenta-based system consumes 36.2% less energy and achieves lower end-to-end latency (10,114 ms vs. 11,032 ms), making it suitable for connectivity-constrained scenarios. Conversely, the ESP32-CAM system is simpler to deploy and allows rapid model updates at the server. These findings provide a reference for Intelligent Transportation System (ITS) deployments requiring scalable, energy-efficient, and flexible road monitoring solutions.

1. Introduction

Intelligent traffic monitoring enables efficient mobility management and road safety in urban environments and automated roads. Real-time data capture, analysis, and processing allow for incident anticipation, optimization of vehicle flow, and improved decision-making in road infrastructure management. Compared to traditional methods based on fixed sensors or static video surveillance systems, mobile and embedded solutions offer advantages in flexibility, coverage, and reduced operational costs.

Key benefits of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAV)-based monitoring are: (i) dynamic coverage of large or remote areas, (ii) reduced infrastructure costs, (iii) energy efficiency with low-power hardware, (iv) low-latency edge computing, and (v) scalable modular architectures.

The development of embedded technologies and their integration with advanced data processing techniques have driven the evolution of monitoring systems. These systems address challenges such as early incident detection or emergency management, leading to the optimization of road infrastructure [1,2]. In this context, UAVs combined with embedded devices have opened up new options for traffic monitoring. They overcome the limitations of conventional systems and enable real-time data collection with high-energy-efficiency systems [2,3].

Because UAVs have computational constraints, lightweight frameworks such as TensorFlow Lite and Edge Impulse have been widely adopted. This enables Tiny Machine Learning (TinyML) deployment in embedded devices [3,4].

We present a UAV-based road data acquisition system using Arduino Portenta boards [5]. Despite limited resources, these microcontrollers can run Deep Learning models efficiently. The system processes vehicle images in real time to feed connected vehicle databases. We also compare its performance with alternative architecture.

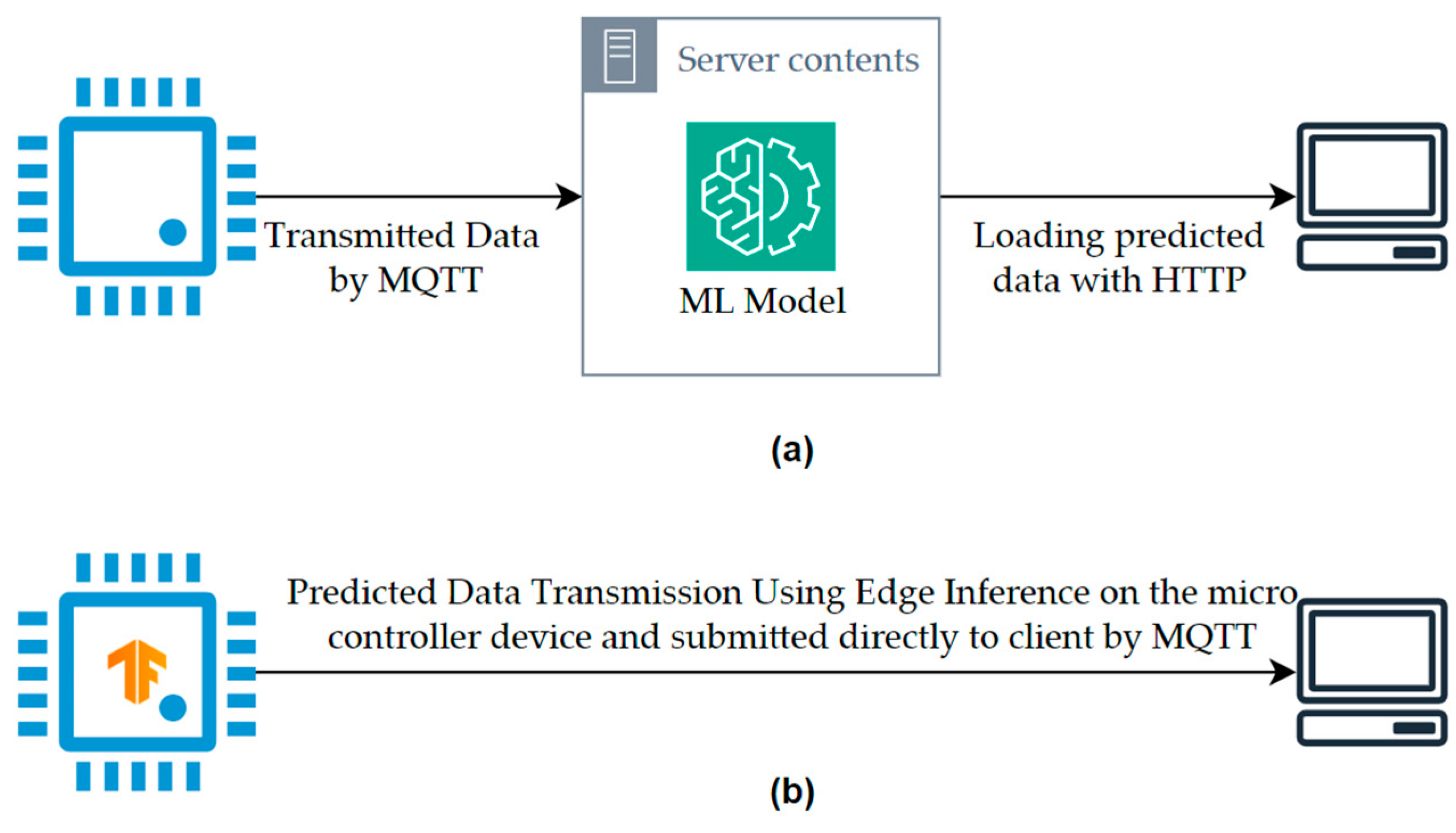

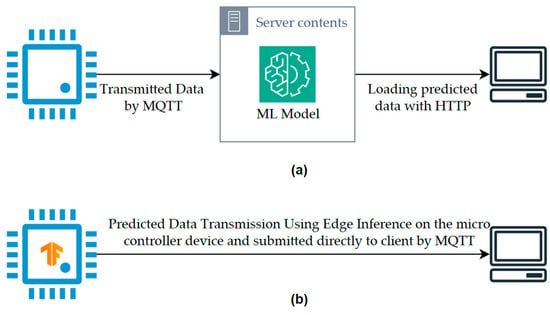

Unlike more traditional systems, these systems perform predictions on the devices themselves. Figure 1 illustrates the difference between a traditional data acquisition pipeline and our proposed edge-inference approach. In panel A, sensor data is transmitted to a remote server via standard protocols (HTTP, MQTT) for inference, introducing latency and network dependency. In panel B, inference is executed directly on the embedded device (Arduino Portenta). Only metadata or selected images are sent to the ITS infrastructure through MQTT, enabling faster decision-making and reduced bandwidth usage.

Figure 1.

(a) shows a traditional approach to sending data by Message Queuing Telemetry Transport (MQTT) protocol from a sensor to make predictions, in which the data must be sent to a processing server. (b) shows an approach using Tiny Machine Learning (TinyML) directly in the embedded system, without the need for an intermediate server to make predictions.

UAV-based traffic monitoring systems rely on aerial data acquisition, efficient processing at the edge, reliable transmission, and integration with existing Intelligent Transportation System (ITS) infrastructures. These aspects encompass lightweight deep learning frameworks, embedded hardware accelerators, communication protocols like Message Queuing Telemetry Transport (MQTT), Infrastructure-to-Everything (I2X), and big-data ingestion infrastructures.

In this work, the focus is placed on road and traffic data acquisition as a representative use case for Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSs). UAVs are employed as mobile sensing platforms capable of capturing imagery and metadata from roads and intersections to support traffic management and decision-making. While traffic monitoring is the main application presented, the proposed architectures and experimental evaluation are not limited to this domain. The same design principles (edge inference versus remote processing trade-offs under energy and latency constraints) can be applied to other UAV-based Internet of Things (IoT) scenarios, including infrastructure inspection, environmental sensing, and smart city applications.

The main contributions of this work, beyond what has been reported in previous studies, are as follows:

- We present the first real-world experimental comparison of two UAV-based architectures: edge inference with Arduino Portenta H7 and remote processing with ESP32-CAM. Previous studies focused only on one approach or relied on simulations.

- We integrate the UAV architectures with a validated big-data ingestion pipeline (Kafka + Beam + MongoDB), demonstrating end-to-end feasibility for ITS deployments, a step rarely addressed in related work.

- We provide a comprehensive trade-off analysis of energy consumption, latency, and detection accuracy, defining practical usage scenarios for each architecture.

These contributions position the proposed architectures as relevant references for the design of intelligent, low-power, and adaptable UAV-based monitoring systems in automated road environments.

Unlike prior works that test only one architecture or rely on simulations, we compare two UAV-based approaches in real-world conditions. We integrate them with a validated big-data ingestion pipeline (Kafka + Beam + MongoDB) and quantifying energy, latency, and inference performance. This positions the work as a practical reference for large-scale, real-world ITS deployments.

The following sections include: methods, describing the methodology and the developed work plan; results, presenting and describing the obtained results; a discussion section addressing relevant aspects of the implemented development; and, finally, the conclusions of the work.

2. State of the Art

Data collection systems on automated roads using UAVs (Unmanned Aerial Vehicles) and embedded devices represent a technological convergence that has experienced significant advances in recent years [6,7,8]. There has been an evolution from basic monitoring systems to integrated platforms capable of real-time analysis, using Deep Learning techniques optimized for resource-constrained platforms. To properly contextualize this evolution, it is necessary to consider four key dimensions: (i) UAV applications for traffic monitoring, (ii) edge and embedded computing systems, (iii) inference frameworks and hardware accelerators, and (iv) communication protocols and integration with large-scale Intelligent Transport Systems (ITS) infrastructures.

It is possible to implement UAV systems with frameworks like TensorFlow Lite, developing highly energy-efficient solutions capable of preprocessing traffic data, detecting anomalies in road infrastructures, or even detecting vehicle behavior metrics without constant cloud dependency [6,7,9].

2.1. UAV Applications in Traffic Monitoring

UAVs have proven to be effective tools for monitoring urban traffic, offering significant advantages over traditional detection methods. They provide a low-cost alternative compared to other tools that require higher capital investment and operational costs [10]. Therefore, route planning for UAVs intended for urban traffic monitoring is a subject of research. Some studies focus on developing algorithms that maximize monitoring coverage efficiency while minimizing energy consumption, increasing flight time [11,12]. Thanks to these advances, UAVs can systematically cover large areas, providing continuous data on traffic conditions in different urban zones [7,9].

The ability of UAVs to provide real-time traffic information has been validated by studies demonstrating the feasibility of estimating effectiveness measures using data collected by drones [13]. These systems can track individual vehicle movements within traffic lanes, enabling calculations and metrics such as maximum queue length, delays, accident rates, among others.

Specific traffic scenarios such as roundabouts have also been addressed using aerial imagery and AI techniques. In [14], authors developed a prototype for monitoring Spanish roundabouts. They use a RetinaNET model with a ResNet50 backbone to detect and classify vehicles and combining image processing techniques to calibrate the roundabout geometry. The system extracts detailed information about vehicle positions, lane usage, and entry/exit events, which is critical for capacity estimation and safety assessment. Our work complements this line of research by focusing on the data acquisition architecture itself, ensuring that such AI-based applications can be deployed efficiently and at scale using UAVs with edge inference or remote processing.

In recent years, object detection models applied to traffic scenarios have evolved towards architectures capable of maintaining high accuracy while reducing computational requirements. These advances, often focused on detecting vehicles, pedestrians, and traffic signs in complex environments, illustrate the trend towards lightweight and efficient deep learning models suitable for embedded or edge devices. Although our work does not aim to compare or optimize detection algorithms, these developments reinforce the relevance of efficient data acquisition architectures, as they enable the practical deployment of such models in UAV-based systems with limited processing and energy resources.

2.2. Embedded Systems and Edge Computing

Given the computational constraints of UAVs, edge computing has become a key enabler for local processing, allowing decisions to be made in-flight and reducing dependency on cloud infrastructure.

The implementation of edge computing systems on UAV platforms has enabled local data processing, reduced constant connectivity and improved response times. Low-power embedded systems have significantly expanded the potential uses of UAVs, facilitating real-time decision-making [10,15]. This local data processing capability enables applications requiring immediate response, such as traffic incident detection or emergency monitoring.

Comparative evaluation of TinyML platforms has provided standardized criteria for selecting a framework according to specific applications. Performance comparisons between TensorFlow Lite Micro on Arduino Nano BLE and CUBE AI on STM32-NucleoF401RE [16] establish performance parameters. These parameters guide platform selection for different application types, optimizing hardware and software solutions in resource-constrained systems.

On the other hand, the development of environments based on Mbed OS and TensorFlow Lite for general-purpose embedded systems demonstrates competitiveness compared to commercial systems, as they can integrate into Deep Learning architectures across a wide range of microcontrollers [17], representing a significant improvement over the limitations of embedded systems in terms of processing capacity, allowing lower-cost devices to run more sophisticated algorithms.

2.3. Inference Frameworks for Resource-Constrained Devices

Building on the need for efficient embedded processing, multiple inference frameworks have been proposed to simplify and standardize TinyML deployment across heterogeneous microcontrollers.

The rapid growth of the TinyML field has driven the development of multiple specialized frameworks for different platforms, standardizing the ML model deployment process [16]. The diversity of available options requires well-founded criteria considering factors such as energy efficiency, processing capacity, and compatibility with specific hardware.

Regarding frameworks for running Deep Learning models, TensorFlow (TF) Lite Micro has emerged as a leader, capable of meeting efficiency requirements imposed by resource constraints of these devices [18]. TF Micro addresses the hardware fragmentation challenges characteristic of embedded systems, where manufacturers often omit features common in main systems, such as dynamic memory allocation and virtual memory.

On the other hand, optimizing inference engines for 1-D convolutional neural networks has shown significant efficiency improvements compared to standard TFLite methods [19]. This demonstrates a 10% reduction in inference delay and halving memory usage. These optimizations are feasible on consumer devices such as AVR and ARM-based Arduino boards [19].

Beyond inference optimization, training optimization also plays a crucial role in deploying effective deep learning models for UAV-based traffic monitoring. In [20] authors propose an algorithm that partitions large image datasets and discards superfluous tiny objects. This achieves a reduction in training time by approximately 75% without degrading model accuracy. This approach is particularly relevant for sequential images from drones or surveillance cameras, as it produces a more compact and representative training set. While our work does not focus on model training, the combination of such dataset optimization techniques with our acquisition systems could accelerate model retraining cycles when new road scenarios or object classes need to be incorporated.

2.4. Hardware Accelerators for Deep Learning in Edge Computing Devices

To overcome the limitations of general-purpose Microcontrollers (MCUs), researchers have explored lightweight accelerators that deliver higher inference throughput at similar or lower power budgets, which is particularly relevant for UAVs with strict energy and weight constraints.

The development of lightweight and energy-efficient hardware accelerators for Deep Learning has addressed the limitations of traditional algorithms, which require large amounts of memory and energy consumption for calculations and data processing [21]. These accelerators are specifically designed for Internet of Things (IoT) devices, where typical hardware accelerators cannot be integrated due to resource constraints.

Therefore, optimizing accelerators for Edge Computing devices considers multiple factors, including latency, energy consumption, silicon area, and processing accuracy. The designs of these systems focus on architectures that maximize energy efficiency while maintaining the required performance for real-time applications. This approach is particularly relevant for UAV systems where weight, energy consumption, and autonomy are critical factors determining the operational viability of the entire system [22].

2.5. Platform and System Comparison

Recent literature offers exhaustive analyses of the performance of embedded platforms for computer vision tasks in IoT environments [23,24]. Although there is a lack of standardized methodology for integrating Deep Learning algorithms into embedded systems without relying on specific manufacturers, environments have been proposed to generalize this process, combining operating systems like MbedOS with libraries such as TFLite for microcontrollers [23].

In terms of inference performance on low-power devices, the Arduino Portenta stands out for its two cores (an ARM Cortex-M7 at 480 MHz and an ARM Cortex-M4 at 240 MHz) and larger memory (2MB program memory) compared to others like the Arduino Nano 33 BLE, making it an interesting board for machine learning experimentation. Conversely, the Arduino Nano 33 BLE Sense has 1 MB program memory and 256 KB RAM, with an ARM Cortex-M4 core running at 64 MHz, and has been used in federated learning projects [24]. Other boards studied include the OpenMV Cam H7, which had a latency of 155 ms with MobileNet V1 for image classification tasks, or the STM32H747i-Disco board (which shares a similar ARM Cortex M7 processor with the Portenta H7) and had a latency of 220 ms with MobileNet V2, achieving 88% accuracy in person detection tasks [23]. Parallel research on model optimization for embedded systems reveals significant advances in the field. The study “A Generalization Performance Study Using Deep Learning Networks in Embedded Systems” [17] analyzed the generalization of convolutional neural networks on microcontrollers, highlighting that quantization is an indispensable technique for reducing the size and computational cost of Deep Learning networks, identifying that 8-bit quantization reduces memory usage by 50%, although this reduction may lead to a loss of accuracy, which can be minimized with retraining techniques [17,23].

Beyond the choice of hardware, communication protocols are a crucial element in UAV-based data acquisition systems. The communication stage is responsible for providing a transmission route for information to new smart hardware devices. The communication system is based on hardware and software systems, but its importance should not be underestimated, as it is fundamental in the IoT system. The data transmission route must first be decided. According to system limitations, several options are available on the market, including WiFi, 5G, and even satellite signals, each incorporating high-level protocols such as Message Queue Telemetry Transport (MQTT) [25], HyperText Transfer Protocol (HTTP) [26], among others.

In addition, recent work has demonstrated that these communication solutions can be integrated into scalable ingestion infrastructures for real-world deployment, as shown in our group has proposed and validated a scalable big-data and I2X communication backbone specifically designed to ingest heterogeneous traffic sources (multichannel gantry cameras and high-frequency vehicle telemetry) using Apache Kafka, Apache Beam and MongoDB [27]. That study demonstrated the feasibility of large-scale ingestion (48 GB of image data and >3.4 million telemetry messages) and showed that pre-transmission optimizations (resolution reduction and transmission throttling) can reduce upload durations by up to 77%, improving ingestion throughput while preserving operational robustness. Such infrastructure complements embedded/UAV data-acquisition solutions. It provides a resilient ingestion and processing layer for either raw image streams or prefiltered metadata, and by enabling hybrid deployments where on-board TinyML preprocessing is combined with server-side reprocessing and long-term storage.

Based on these findings, this work proposes and compares two UAV-based architectures (one using edge inference on Arduino Portenta and another relying on remote processing). This evaluates the trade-offs in latency, energy consumption, and scalability. This comparative analysis directly addresses the challenges identified in the literature, such as limited UAV autonomy, bandwidth constraints, and the need for efficient data integration with large-scale ingestion infrastructures.

In summary, existing works have proposed UAV-based systems for traffic monitoring or IoT integration. However, they typically assess only one architecture, rely on simulation-based evaluation, or omit integration with large-scale data pipelines. Our work differs by experimentally comparing two alternative architectures under real deployment conditions and by validating their integration into a scalable ITS big-data framework.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. System Overview and Workflow

The proposed system for data acquisition and processing is based on two independent systems, proposed as alternatives to each other. These architectures are based on a modular structure, which allows the implementation of functionalities for automatic traffic monitoring. The main architecture is based on the use of the Arduino Portenta H7 platform, which implements image acquisition, geolocation and embedded processing capabilities through lightweight inference, enabling autonomous operation and reducing dependence on connectivity. This system is ideal for environments with network limitations, as the processed data is transmitted to a local server, which then sends the data to the central server for storage and analysis.

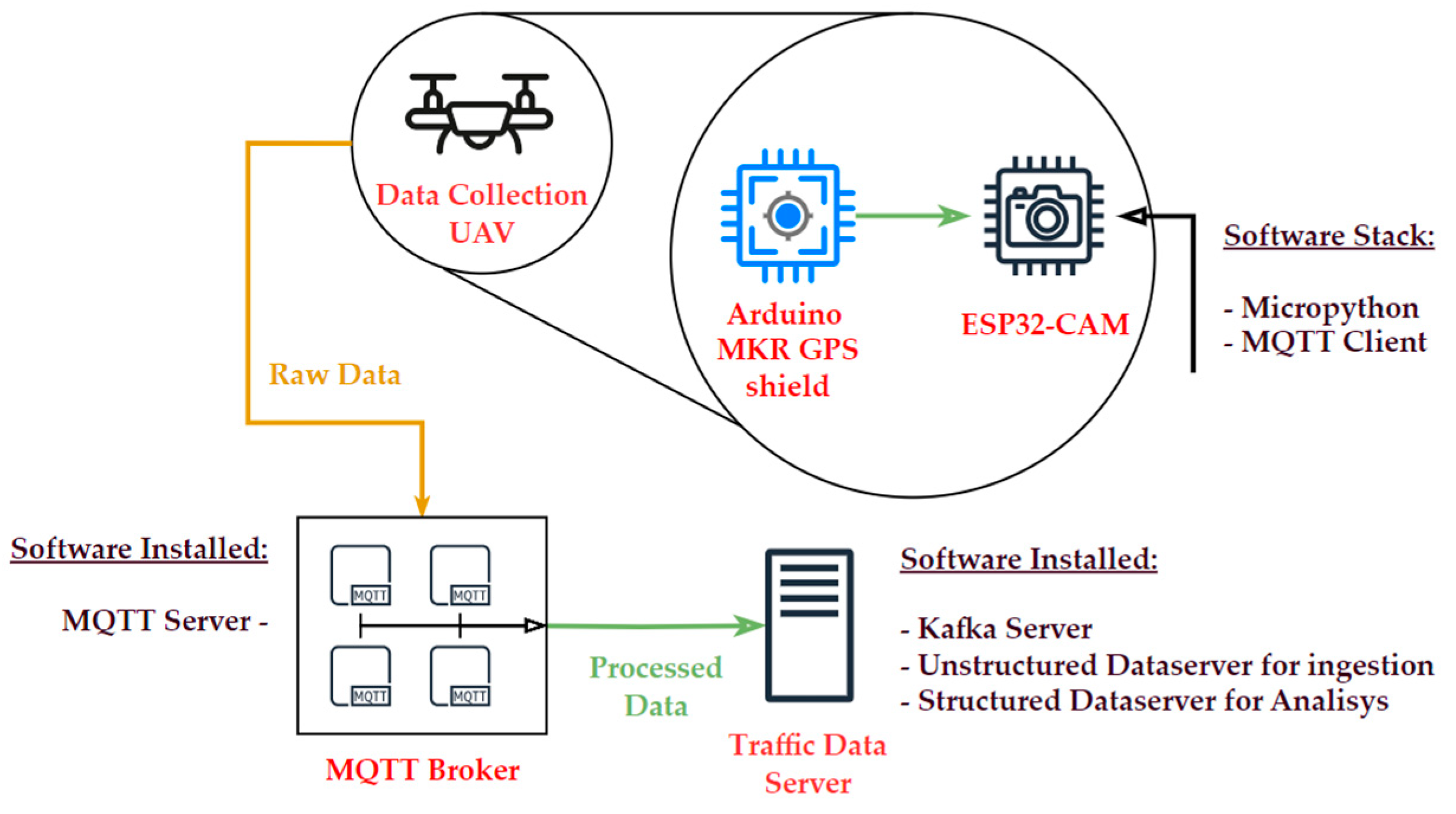

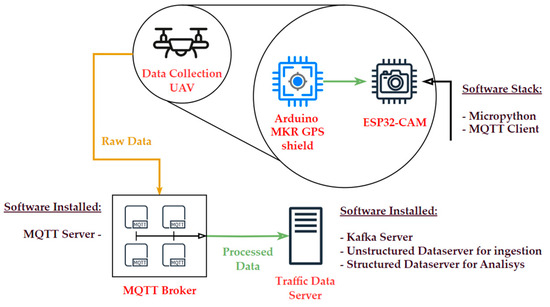

On the other hand, the alternative system uses an ESP32-CAM microcontroller for the acquisition and direct transmission of images and metadata to the central server, delegating processing to the server environment through asynchronous streams supported by MQTT. This variant minimizes the complexity of the embedded hardware but increases the need for stable connectivity and adequate bandwidth.

Both systems are characterized by their independent modular structure and the possibility of operating in continuous data acquisition scenarios, both for early incident notification and for training traffic management algorithms and databases for longitudinal analysis.

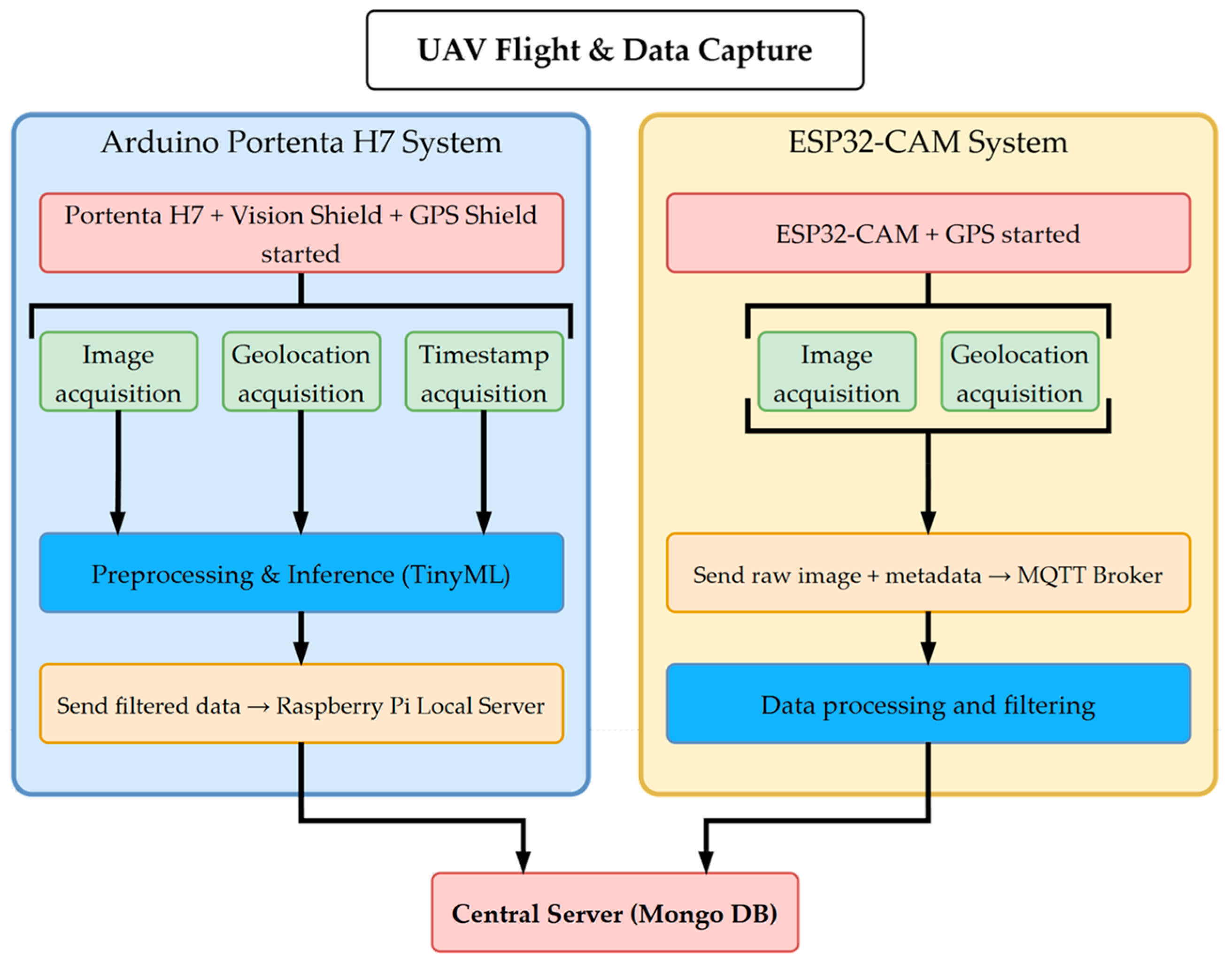

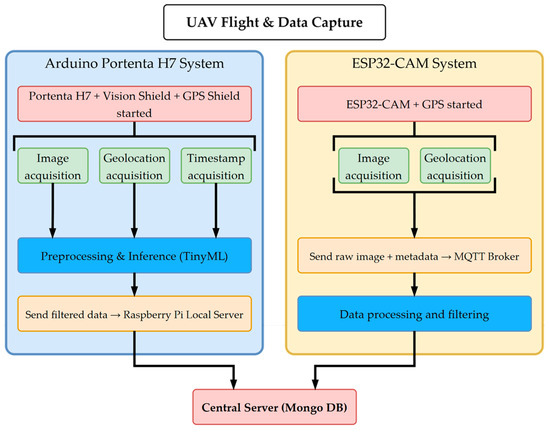

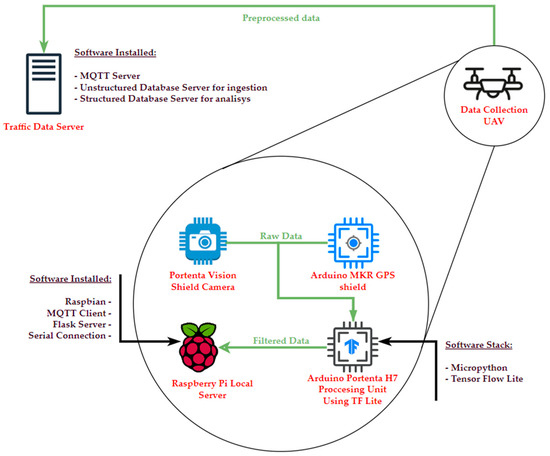

The overall workflow of both proposed architectures is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The figure shows the workflow diagram of the two systems. On the left is the main system based on Arduino Portenta H7, and on the right is the alternative system based on ESP32-CAM.

In the main system, image acquisition, geolocation, and lightweight inference are performed directly on the Arduino Portenta H7, enabling offline operation and reducing connectivity dependency. The processed results, including relevant images, are transmitted to a local Raspberry Pi server before reaching the central MongoDB server.

In the alternative system, raw images and metadata are transmitted via MQTT from the ESP32-CAM to a broker, where processing and filtering are performed. Then, the filtered and processed data are transmitted to the storage server. This approach simplifies onboard hardware but increases reliance on stable network connections.

To clarify the design goals, Table 1 summarizes the main functional and non-functional requirements considered in the system.

Table 1.

Main functional and non-functional system requirements.

3.2. Main System: Arduino Portenta H7 Architecture

The proposed system for data acquisition on automated roads using Arduino Portenta boards is structured into main modules: the detection and data acquisition module, the processing and filtering module, and the data sending and extraction module. We used an incremental development approach, ensuring each developed module was independent, allowing phased implementation, but always performing the necessary analysis milestones to verify module functionality before proceeding to the next.

We had to validate this system module by module, so a series of tests were conducted throughout development to ensure each module functioned correctly before full integration. For example, validation of the detection and data acquisition module involved verifying the correct storage of data captured by the Arduino Portenta Vision Shield camera and geolocation data from the Arduino MK1 GPS-Shield. We validated the preprocessing module (consisting of the Arduino Portenta H7 board and a TensorFlow Lite algorithm) by classifying data using an image set and returning labeled results. Subsequent integration testing ensured only images containing the filtered element were labeled and stored.

The data sending and extraction module was initially intended to send images via the integrated Ethernet cable on the Arduino Portenta board, but this was not possible due to the inability to install HTTP-capable libraries. Therefore, image transmission was preferred via a Raspberry Pi [28], generating a service that read data sent by the Arduino Portenta board and forwarded it to a central server.

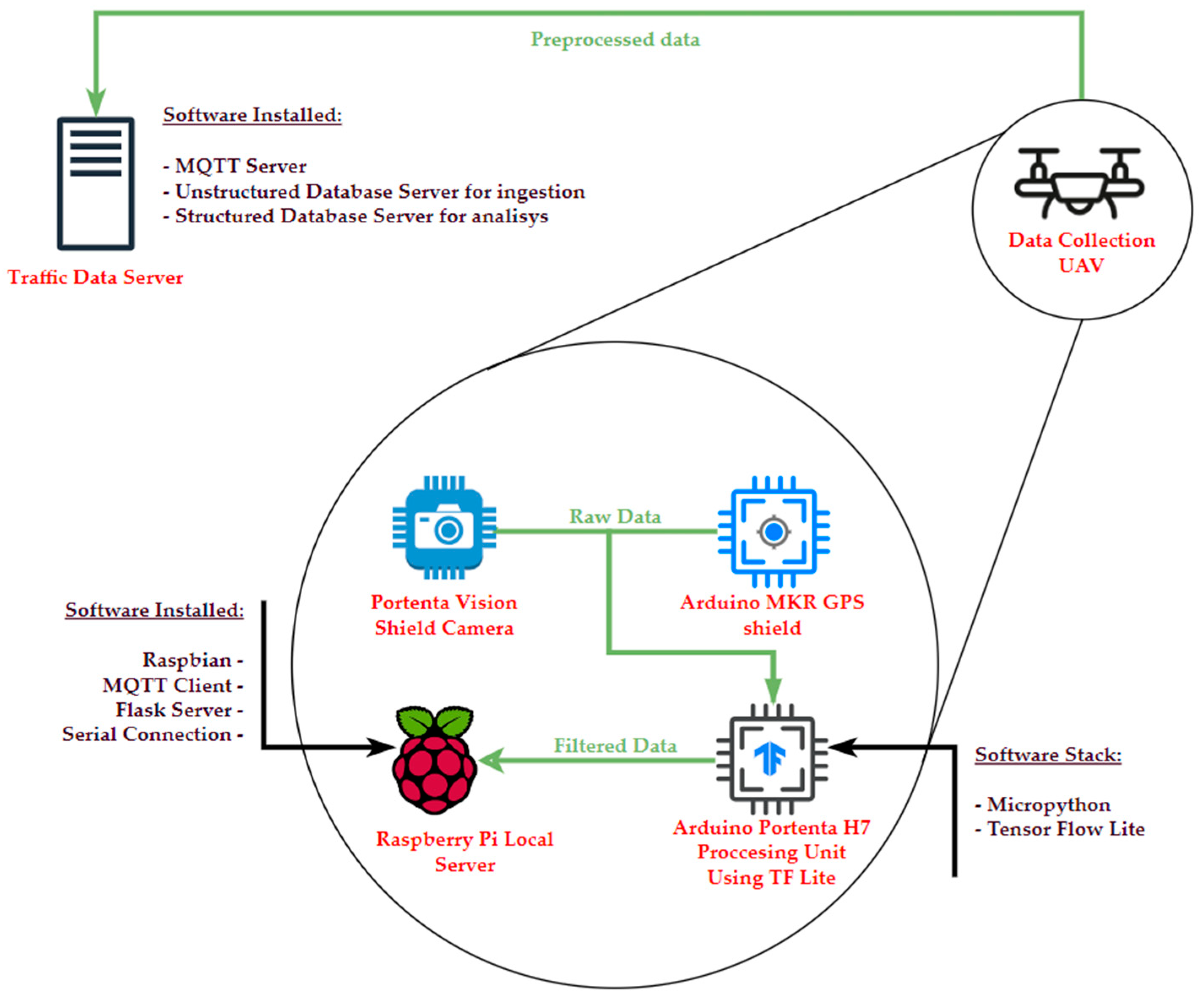

This implemented system enables the capture of relevant data, including geolocation, time, and basic object detection information using Arduino Portenta boards, as well as sending all data, including images, for storage in a central server implemented with a MongoDB database. MongoDB was chosen for its ability to efficiently manage unstructured and semi-structured data, especially useful for image environments with associated metadata, making it a suitable solution for the designed architecture. The general system architecture is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

General architecture diagram. Components of the Arduino Portenta system and the local Raspberry server responsible for sending data to the main server after collection are shown, as well as the software components installed for the correct use of the system. Compatible with Kafka/Beam ingestion pipelines for centralized storage and analytics (see García-González et al. [28] for validated server implementation and ingestion benchmarks).

3.2.1. Detection and Data Acquisition Module

This module, responsible for obtaining road environment information, is mainly implemented using Arduino Portenta boards. The Arduino Portenta H7 acts as the central controller, managing and performing the main operations of this module, coordinating signals from other components. Initially, this system was programmed in MicroPython to leverage the language’s capabilities for IoT applications.

The second component is the Arduino Portenta Vision Shield [29], enabling vision techniques through its integrated camera for subsequent processing. The Arduino MKR GPS Shield [30] provides geolocation capability, assigning geographic location and timestamp to captured images.

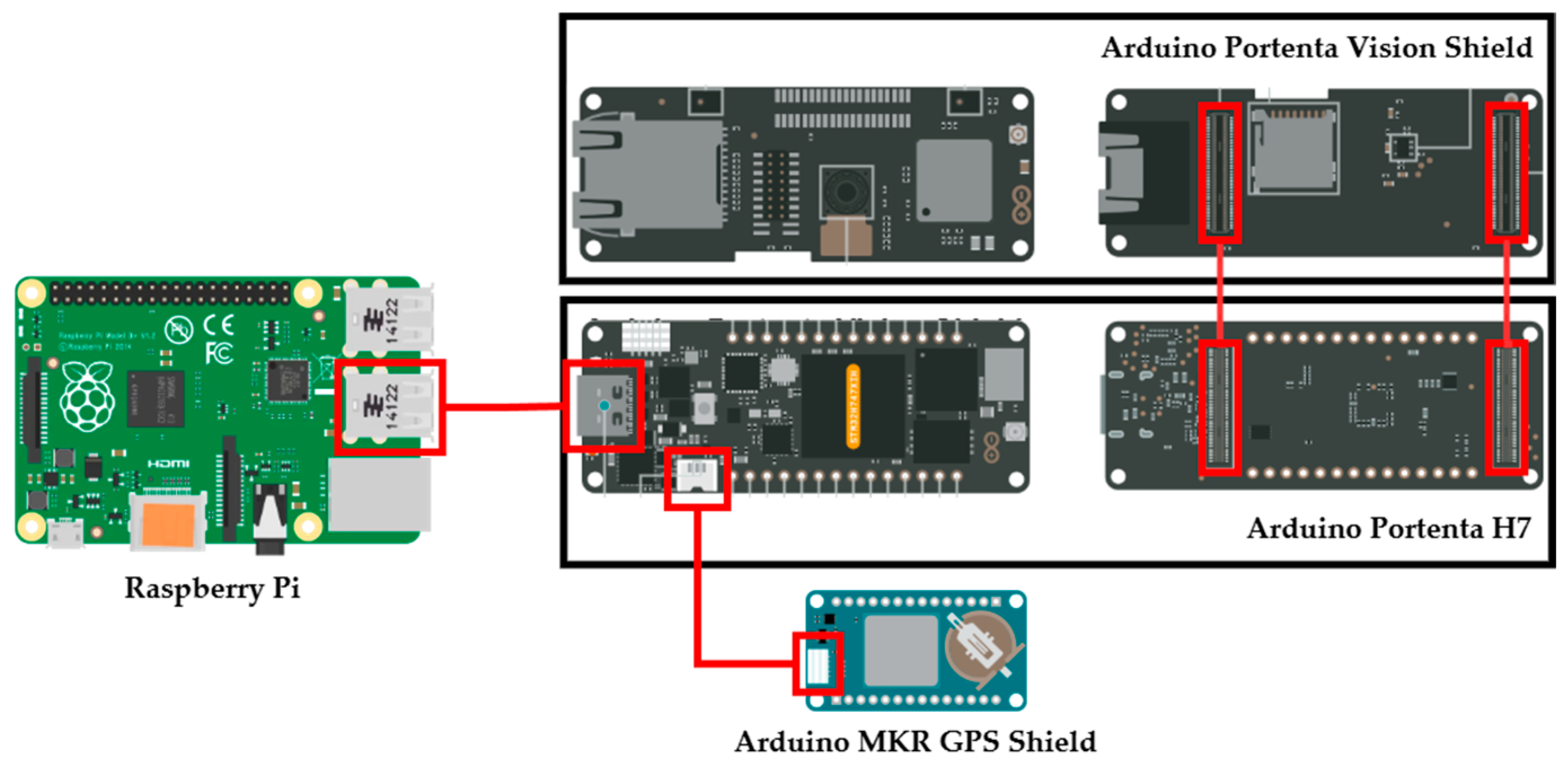

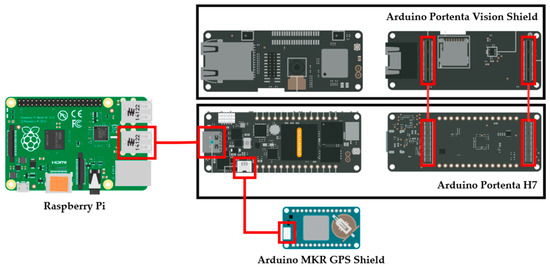

Connections between devices are made via J1 and J2 ports for communication between Portenta boards (Portenta H7 + Vision Shield) and the I2C port for connecting the Arduino MKR GPS with the Arduino Portenta H7. This connectivity is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Component connection diagram of the data acquisition system. Arduino Portenta H7 acts as the central processing unit connected to the Arduino Portenta Vision Shield and Arduino MKR GPS Shield. This system communicates with a Raspberry Pi via USB, acting as a server. Red boxes highlight the board connectors, with the lines representing the inter-board connections.

3.2.2. Data Preprocessing Module

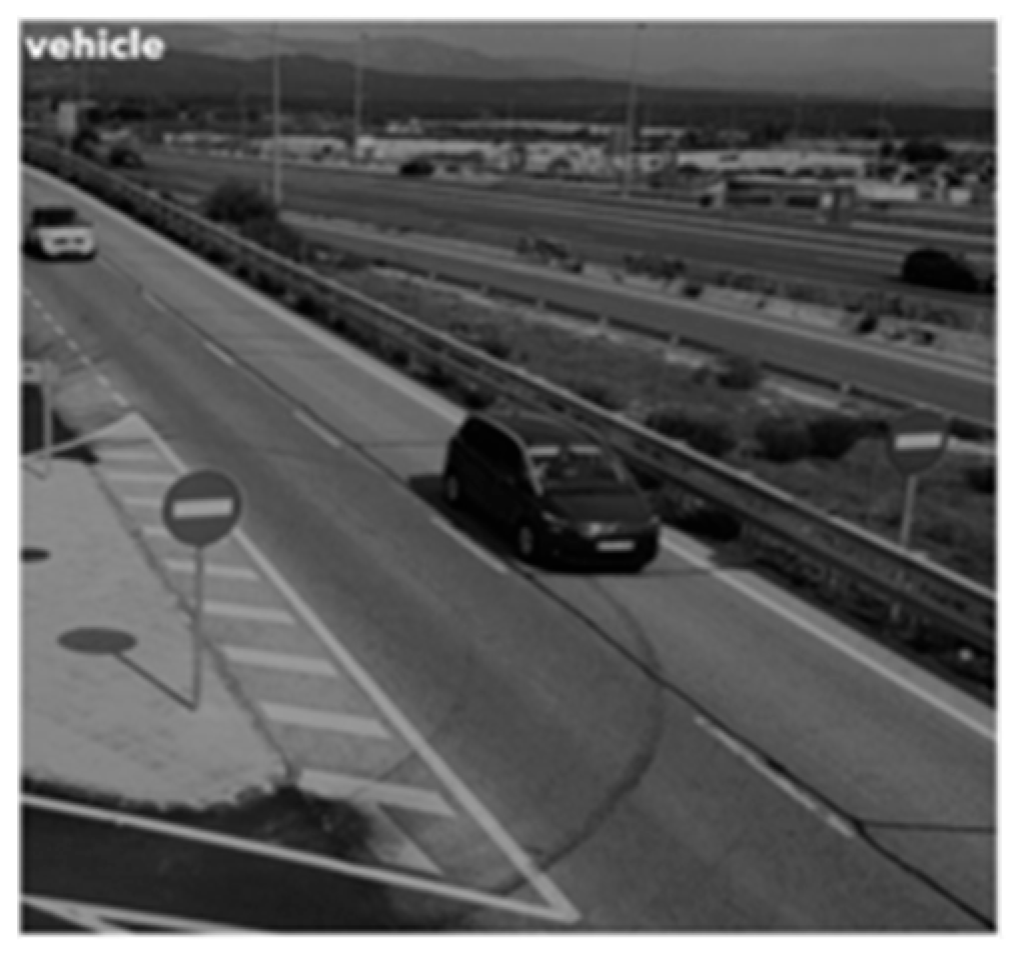

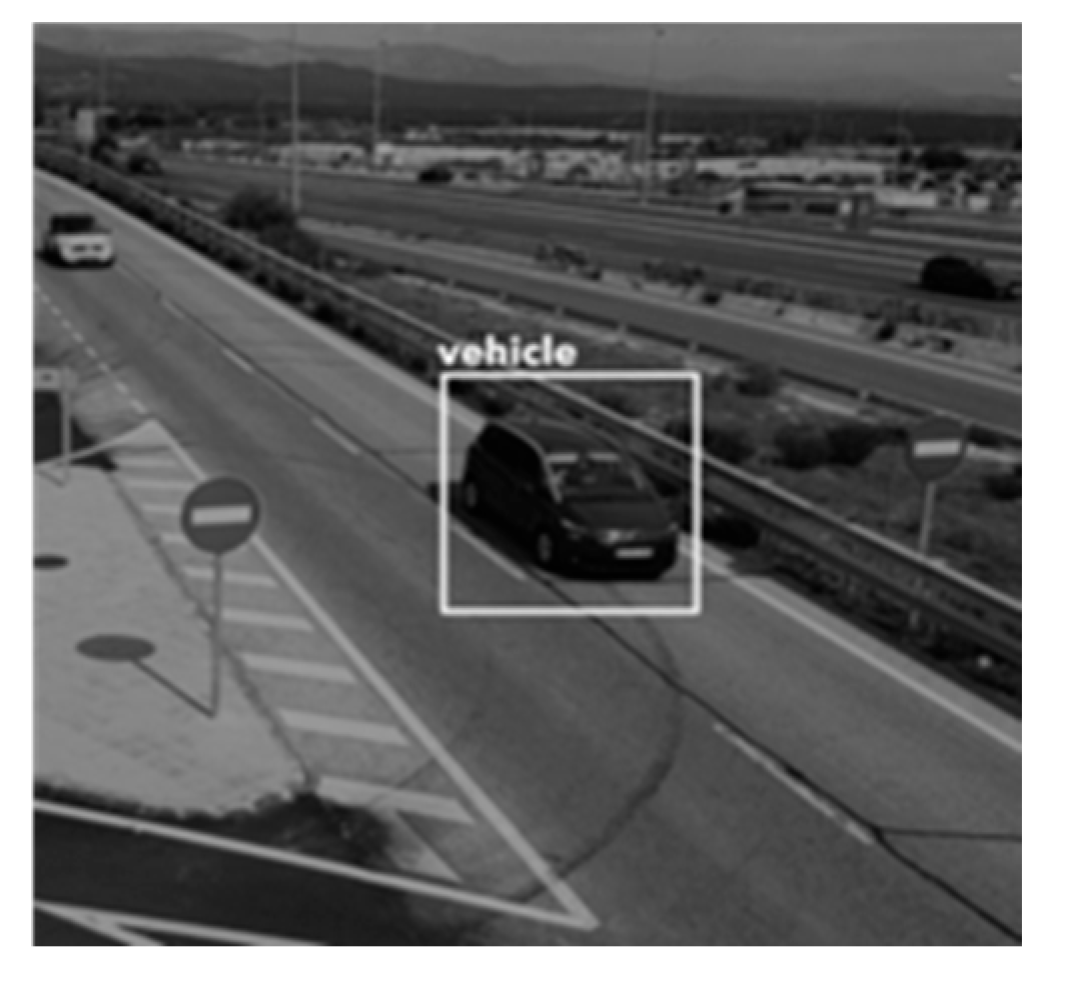

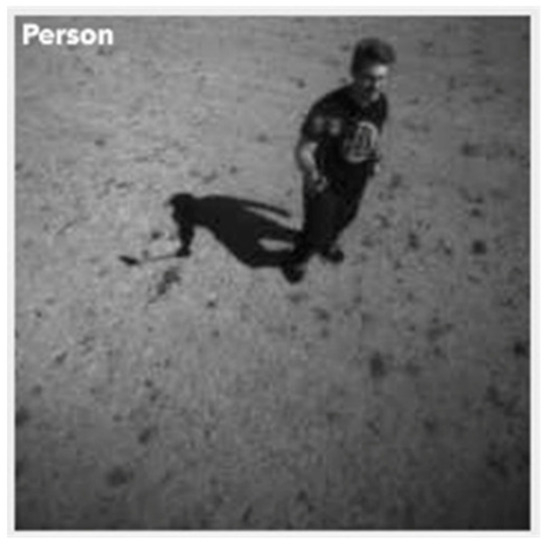

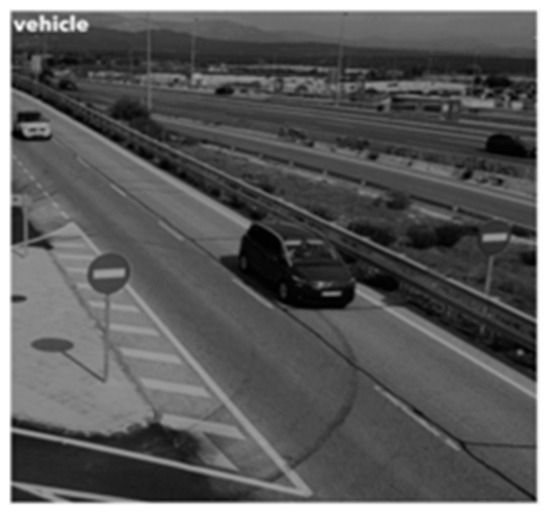

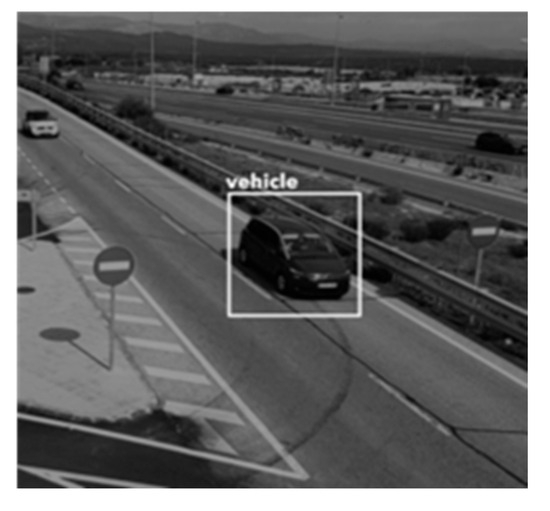

Technical limitations were encountered when implementing this module, mainly due to the board’s limited memory capacity, preventing trained models from being correctly installed and executed. The approach was redirected to perform basic detection directly on the Arduino Portenta H7, exploring the implementation of TensorFlow Lite algorithms for object detection in images captured by the Arduino Portenta Vision Shield. Two algorithms were developed: one for detecting people in images (see Figure 5 for positive identification examples), sending the detection probability to the server and, if the expected object was detected, also sending the image; and another for detecting vehicles, but due to the original model size, only a limited version could be run on the Arduino Portenta, indicating the presence or absence of vehicles. The difference in model size can be seen in Figure 6 and Figure 7.

Figure 5.

Identification of people in a frame from overhead view using the person detection model on Arduino Portenta boards.

Figure 6.

Vehicle detection using the “lightweight” model from the Arduino Portenta board.

Figure 7.

Vehicle detection using the “heavy” model from a computer, using the same image as the previous example.

For object detection in images captured by the embedded system, deep learning models optimized for execution on resource-constrained devices were selected. Specifically, a MobileNetV2-based architecture was used, recognized for computational efficiency and suitability for embedded systems. This architecture was adapted with post-training quantization techniques. It converted model weights and activations to 8-bit precision, reducing model size and memory consumption. TensorFlow Lite configuration included default optimization and specification of operations compatible with microcontroller execution, ensuring deployment environment compatibility. Hyperparameters included an initial learning rate of 1 × 10−3, batch size of 16 for person detection and 32 for vehicles, and a maximum of 50 and 75 epochs, respectively. Focal Loss was used for class imbalance in person detection and weighted cross-entropy for vehicle detection.

To ensure real-time inference viability—processing images continuously without perceptible delays—and efficient memory use, an image preprocessing pipeline adapted to hardware constraints was designed. Processing begins with image acquisition via the Vision Shield module, providing RAW captures at a native resolution of 240 × 240 pixels. Given the limited SRAM capacity of the Portenta H7, images are resized via bilinear interpolation to 124 × 124 pixels, enabling efficient execution of quantized detection models. The system’s response depends on processing capacity, memory optimization, and appropriate input resolution selection. These factors balance resource consumption and preservation of relevant visual information for classification.

We integrated the preprocessing pipeline into the Arduino Portenta board using optimized MicroPython scripts, prioritizing memory management efficiency and sequential processing. Specific routines were implemented for resource release after each inference, minimizing memory fragmentation risk and ensuring system stability during prolonged operations. Image processing was limited to fundamental operations, sending images only when identified elements (people or cars) were detected, prioritizing robustness and reproducibility in real deployment conditions. This approach validated the feasibility of running lightweight deep learning models on low-power devices, laying the groundwork for future optimizations and functional extensions.

3.2.3. Data Sending and Extraction Module

This module is responsible for transferring processed data from Arduino Portenta boards to a central server for data analysis. Initially, a local server using a Raspberry Pi 4 [28] with Raspbian Desktop was used, communicating wirelessly with Arduino Portenta boards via WiFi access point (hotspot) using RaspAP and DHCPd services. Data reception was implemented via an internal web service using Flask, allowing Arduino Portenta boards to send geolocation data, timestamp, and object detection results via GET requests, which were then stored as local files.

In a second iteration, the server acted more as an intermediate broker capable of receiving data from various sources and forwarding them to a central server. RaspAP and Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol (DHCP) services remained, but data were sent via MQTT to the central server, allowing multiple data sources to generate information.

In the final iteration, the server was updated to also receive and send images to the central processing server. RaspAP and DHCP services were disabled, and a Raspberry service reading messages sent via Serial Port was implemented, capable of receiving both images and processed information from the Arduino Portenta board and forwarding them to the central processing server.

For scalability and durability, the onboard local broker—central storage path used in our implementation is compatible with the big-data ingestion pipeline previously validated [27]. This pipeline bridges MQTT and Kafka and forwards topics to Apache Beam processing and MongoDB storage for further analytics and long-term retention. This design allows the Portenta local filtering to significantly reduce data volume arriving to the ingestion cluster while preserving the option of full-image upload when higher fidelity is required.

3.3. Alternative System: ESP32-CAM Architecture

The proposed design meets the stated objectives, implementing an innovative technology system, but proper validation requires comparison with other systems. Thus, a parallel system was designed to meet the same objectives with alternative and less innovative technology. Unlike the main system, which incorporates edge computing preprocessing using Arduino Portenta boards, this system opts for immediate transmission of captured data to the central server, where processing and storage occur.

The architecture has three components: data acquisition, transmission, and processing/storage. This configuration reduces onboard hardware complexity, delegating data analysis and filtering tasks to the server environment, especially useful when device simplicity is prioritized and a stable network is available.

The data acquisition module comprises the ESP32-CAM, capturing images at defined intervals, geolocating the device, adding a timestamp, and sending all information to the MQTT broker. A timestamp is generated locally using the ESP32 internal clock to ensure temporal consistency of the captured data. The broker acts as an intermediary between the data capture device and the storage server, enabling asynchronous communication. The server implements an MQTT message reception service, capable of extracting received images and applying filtering and classification algorithms for storage in a database. The data flow from ESP32 to the database, highlighting connection points, is shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Diagram of the alternative architecture. It shows the components of the ESP32-CAM system and the MQTT Broker responsible for filtering and sending data to the main server, as well as the software components necessary for the architecture.

The alternative Data Capture Module is implemented using an ESP32-CAM microcontroller, a compact device integrating a digital camera and WiFi connectivity, making it suitable for image acquisition. The module’s objective is to obtain road images and their spatiotemporal coordinates, sending them via IoT communication systems.

The ESP32-CAM is programmed using the Arduino IDE, implementing specific libraries for camera configuration and WiFi management. The device is set to capture images every second, encoding them in base 64 for MQTT transmission. Each image includes a timestamp generated by the microcontroller and a GPS position, contextualizing captured data.

On the other hand, we have the data transmission module, whose main function is to transmit images captured by the ESP32-CAM to a centralized processing and storage system. MQTT was chosen for its lightweight, efficiency, and ability to operate in resource-limited networks.

Upon image capture and encoding, the ESP32-CAM packages and sends it with associated data, publishing the message to a specific MQTT broker topic, allowing decoupled emitter and receiver connections. The configuration was done on a local server but can be migrated to a dedicated server depending on available resources. The broker subscribes to defined topics for image transmission. It decodes image information to apply filtering according to the implemented classification algorithm.

Finally, we have the data processing and storage module. This module constitutes the core of the alternative system for data analysis, filtering, classification, and sending data to the storage server. Unlike the Arduino Portenta-based system, analysis is performed on an external server, allowing greater processing capacity and flexibility in model updates.

The server subscribes to the MQTT broker topics, reading messages published by the data capture module. Images are decoded and subjected to filtering via object detection or image quality validation, depending on application criteria.

Python 3.11 libraries were used to create a service capable of reading topics, decoding, and managing images. Additionally, MongoDB connection was implemented for flexible document storage, allowing both images and associated data to be stored in a non-relational structure.

We store the data in a “cameras” collection, where data corresponds to different data sources, identified by camera ID. This centralized processing and storage architecture allows easy system scaling by adding new capture devices or updating analysis algorithms without hardware intervention, a significant advantage in dynamic or hard-to-access environments.

3.4. Validation Metodology

Once the system was designed, a series of tests were proposed to identify the performance of the different infrastructure modules:

- System Energy Consumption. Validation involved measuring the board’s energy consumption using a device like the USB3.0 Color Display AT34, capable of measuring the energy consumption of electronic devices connected to a power source.

- Detection Model Parameter Measurement. We adapted standard training and validation approaches for low-power hardware implementation, calculating Loss and Accuracy metrics during training and validation as key indicators of model performance.

- Comparison with Other Lightweight Data Acquisition Systems. A parallel system like the proposed architecture was implemented using components such as an ESP32 CAM [31] instead of Arduino Portenta boards, comparing results to validate which architecture is more optimal.

A server was implemented to handle data ingestion and model parameters, as well as the rest of the tests, capable of hosting sensor data and providing access to them. This infrastructure consisted of a message queue system using Apache Kafka [32] with an intermediate MQTT broker [25] acting as a data collection system capable of processing information from various sources simultaneously.

3.5. System Application

This system was conceived as a data source for training traffic monitoring and management algorithms on automated roads, aiming to generate a subsystem oriented toward improving real-time traffic supervision and control. The work focused on real-time data capture, transmission, and processing from UAVs to a processing center. Figure 9 shows an embedded prototype, identifying Arduino Portenta boards, MKR GPS Shield components, and the broker server. This configuration was designed to keep the server close to the main component, but its location can be changed as long as it can connect to the Arduino Portenta board, not necessarily being on the UAV.

Figure 9.

Complete system embedded on a hexacopter drone. (a) Bottom view showing the embedded components located near the landing gear, including the Arduino Portenta H7 board with the Portenta Vision Shield module. (b) Top view illustrating the placement of the MKR GPS Shield and the Raspberry Pi unit acting as the local broker within the UAV architecture.

Current system applications include:

- Early Traffic Incident Monitoring: If the system is alerted to possible incidents, a UAV equipped with this system can be sent to the scene, providing real-time aerial views, as geolocation and person detection data at specific locations can be collected, all with timestamps. This information can be sent to a control server, enabling preliminary assessment and resource allocation.

- Feeding Databases for Traffic and Road Safety Management: Designed to capture and preprocess data for transmission to a central server, one of its main applications is storing data in a database on road conditions. Even without an image storage system, collecting geolocated data with temporal object detection information can be useful for future analyses of event recurrence in specific areas at certain times.

- Potential for Road Infrastructure Inspection: Integrating the system into a UAV opens future applications such as infrastructure inspection (bridges, tunnels). In later versions, overcoming information capture and transmission limitations, early detection of structural damage or maintenance needs could be facilitated.

- Potential for Monitoring Systems on Complex Roads: Another future application is integration with complex traffic management systems, serving as an information source on road conditions in critical driving situations, providing a general overview to arbitration and traffic control systems. The system can initially train a model with collected data, then use it for managing traffic at these critical points.

4. Results

The proposed system was evaluated through tests aimed at quantifying detection algorithm performance and analyzing overall system behavior under real operating conditions. Results are presented in a structured manner using widely recognized quantitative metrics, visualizations, and comparisons with alternative solutions, providing a clear and reproducible view of the developed system’s capabilities and limitations. The validation methodology has been clarified to explicitly link each test with system objectives.

- Energy consumption: Evaluation of UAV endurance feasibility.

- Detection accuracy: Performance of embedded ML models under hardware constraints.

- Latency: responsiveness and impact of local vs. remote processing.

We used 249 images from [33], labeled for cars, motorcycles, and pedestrians. Tests were conducted under varied conditions (altitude, lighting, indoor/outdoor) to approximate realistic UAV deployment scenarios.

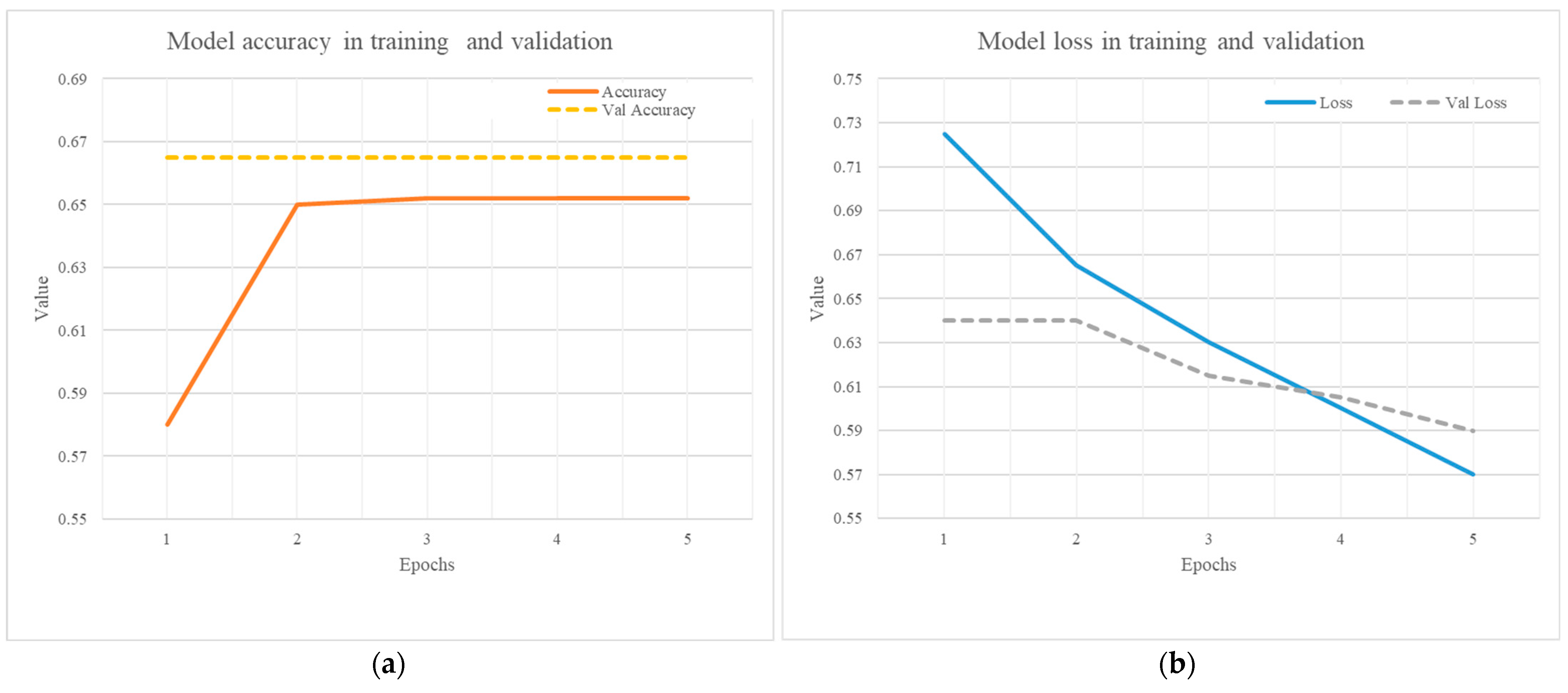

4.1. Detection Algorithm Performance Metrics

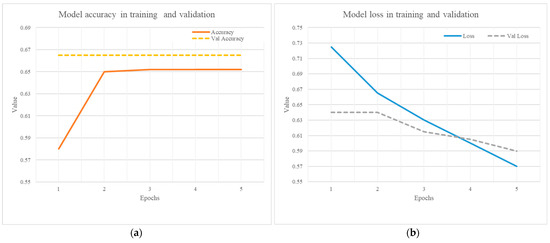

We trained two models to identify people and vehicles, but only the second model was trained for both the main and alternative systems. We evaluated detection models using standard metrics calculated on the validation set. The latter was trained for five epochs on a labeled dataset for classification with categories car, motorcycle, and non-vehicle (details in Table 2), using an architecture optimized for low-cost embedded hardware such as Arduino Portenta. Table 3 details standard loss and accuracy metrics for model training and validation.

Table 2.

The number of samples per class used for model training and validation.

Table 3.

Model loss and accuracy in training and validation.

During development, the loss function during training decreased continuously from 0.725 in the first epoch to 0.57 in the fifth, while training accuracy increased from 0.58 to 0.652. This indicates the model learned distinctive features from the training set. Validation accuracy remained constant, possibly indicating early saturation in generalization ability due to architecture simplicity and small validation set. However, validation loss decreased from 0.64 to 0.59, suggesting improved prediction calibration. This evolution is shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

(a) Model accuracy and (b) Model loss. Both during training and validation.

Although no specific accuracy threshold was set, metric stabilization and absence of overfitting signs in so few epochs were interpreted as signs of adequate learning for this experimental micro-tensor. This behavior is typical in TinyML models implemented on resource-constrained platforms, aiming for functionally acceptable performance without compromising energy efficiency or embedded system latency [34,35]. Early stabilization in validation accuracy could relate to a small or low-diversity validation set.

Although the validation accuracy of 66.5% may seem moderate, it is consistent with the constraints of 8-bit quantized models deployed on microcontrollers and the relatively small dataset used (249 images). In UAV-based filtering tasks, this accuracy is sufficient to discard irrelevant frames and reduce transmission load, achieving the primary goal of energy savings. Future work will include dataset expansion and fine-tuning to improve generalization without significantly increasing computational cost.

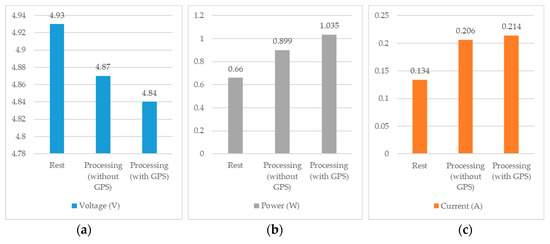

4.2. Embedded System Energy Consumption Measurement

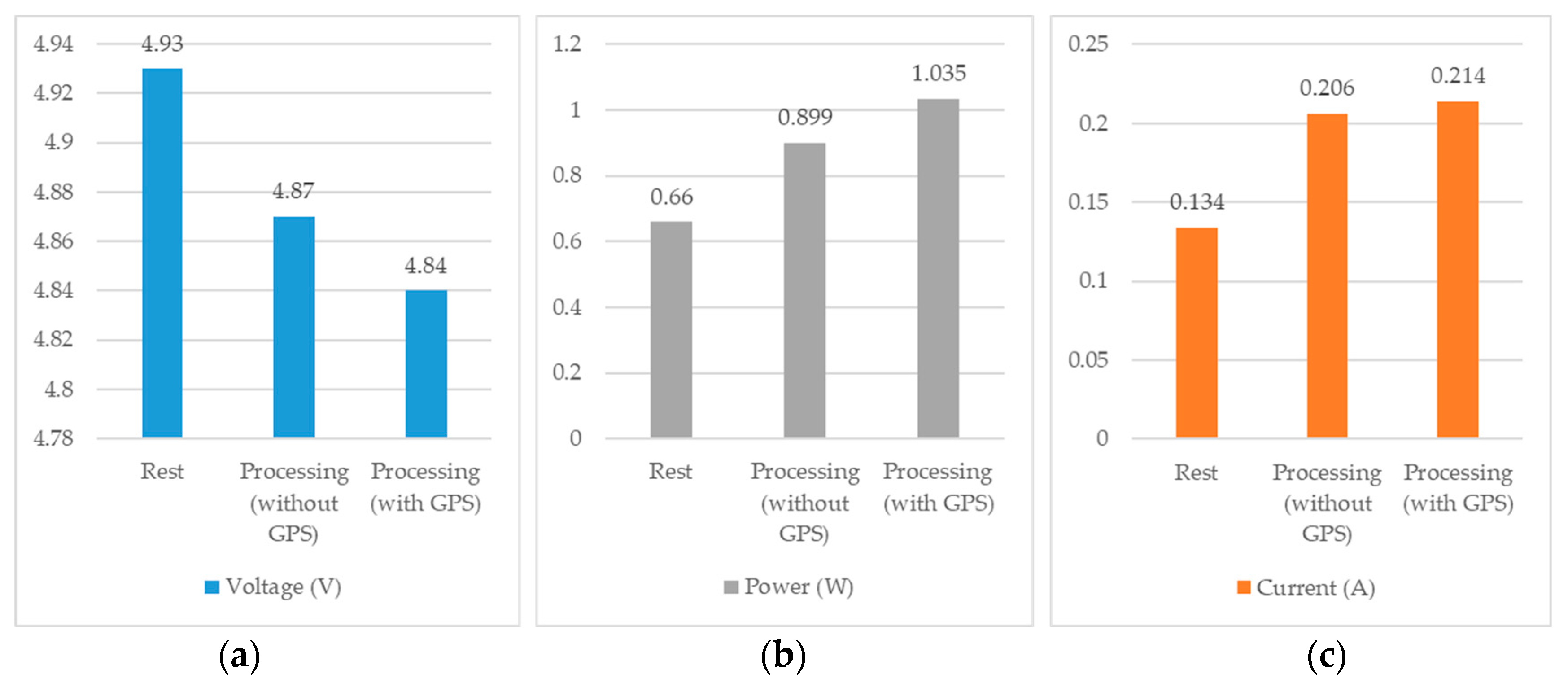

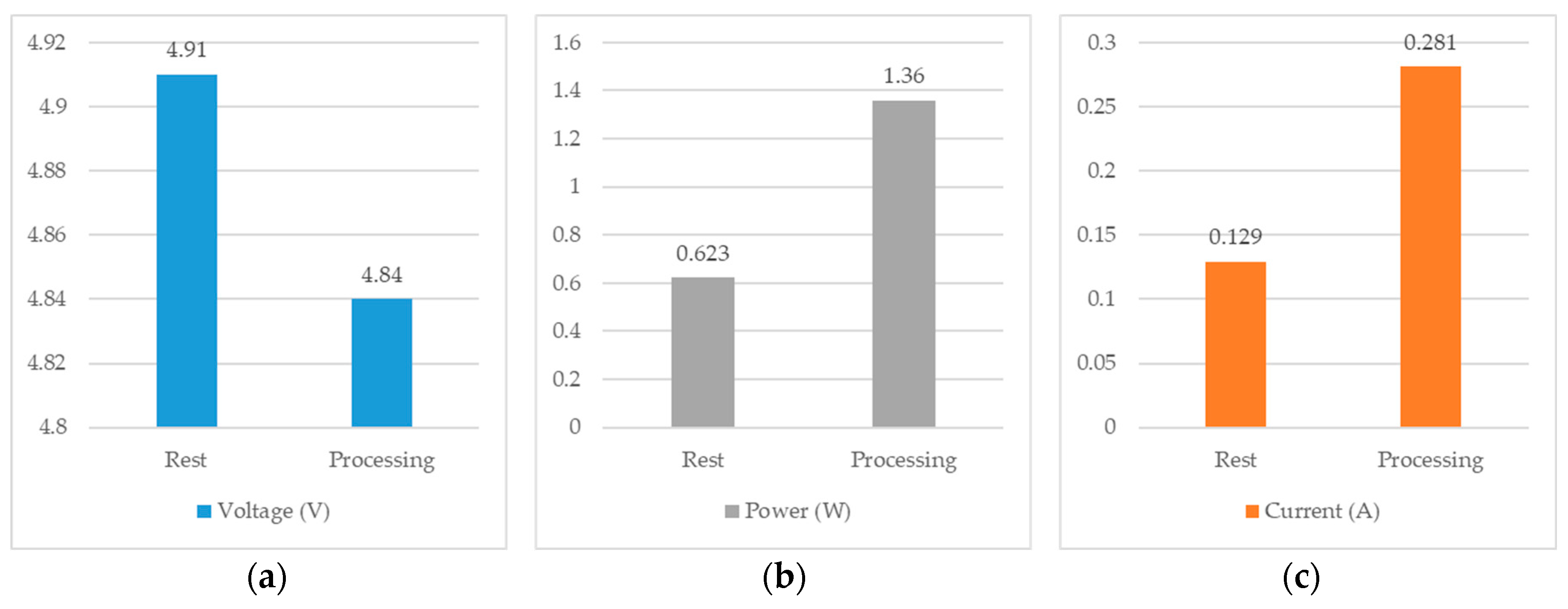

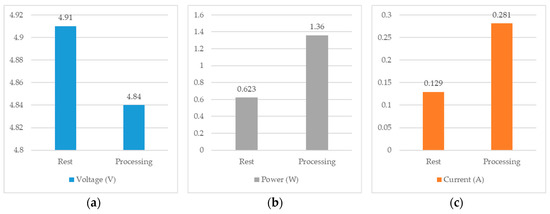

To assess system viability in low-power scenarios, energy consumed by the hardware during idle and active processing phases was measured, both with and without GPS, for Arduino Portenta boards and the alternative ESP32-CAM system. Measurements used a precision USB meter directly between the hardware and the power source. Figure 11 and Figure 12 show energy consumption results for both systems.

Figure 11.

Average energy consumption of the main system based on Arduino Portenta boards in terms of (a) Voltage, (b) Power and (c) Current.

Figure 12.

Average energy consumption of the alternative system based on ESP32-CAM boards in terms of (a) Voltage, (b) Power and (c) Current.

In idle, the main system consumed 0.134 A at 4.93 V (0.660 W). During active execution without GPS, consumption reached 0.206 A at 4.87 V (0.899 W). With GPS, consumption was 0.214 A at 4.84 V (1.035 W), a 36.2% increase from idle to inference without GPS. Adding MKR GPS board consumption resulted in a further 15% increase.

For the alternative system, idle consumption was 0.129 A at 4.91 V (0.623 W). During processing, consumption rose to 0.281 A at 4.84 V (1.360 W), a 118.3% increase from idle, higher than the main system. Both of the systems maintained consumption below 1.5 W during peak operation, making them viable for battery-powered UAV implementations.

4.3. Transmission Latency Measurement

Response times for each system were measured, including image capture and transmission times for both systems, as well as local processing time for the main system and server processing time for the alternative system. Results are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Latency times in both systems, main and alternative.

Both systems had a capture time of 1000 ms, mainly due to the set delay between data captures. Transmission times showed two values: from the data capture device to the first connection node (5823 ms for the main system to the Raspberry Pi, 6715 ms for the alternative to the broker), and from there to the data storage server (3135 ms and 3020 ms, respectively). Total transmission times were 8958 ms (main) and 9735 ms (alternative).

Processing times were also measured: the local model in the main system averaged 156 ms, while the server model in the alternative system averaged 297 ms. The main system’s average latency was 10,114 ms, while the alternatives were 11,032 ms.

4.4. System Comparison

Comparing both architectures reveals complementary approaches to intelligent traffic system monitoring. The main system prioritizes local processing to minimize connectivity dependency, while the alternative opts for immediate transmission and remote server processing. This duality allows evaluation of critical trade-offs between operational autonomy, hardware complexity, and scalability. Table 5 shows a comparative summary of key features.

Table 5.

Comparative table between main and alternative system features.

5. Discussion

This research focused on designing a system capable of capturing road data for traffic management on automated roads by embedding data acquisition systems on UAVs. The main system used Arduino Portenta H7 and Vision Shield boards programmed in MicroPython, while an alternative system was designed and implemented using ESP32-CAM programmed in Arduino language. Practically, Arduino Portenta boards offer several advantages over more powerful and expensive systems, enabling computation directly on the board, advantageous in terms of energy consumption, weight, and deployment complexity. The alternative system was proposed as a “direct competitor” in these terms, as the ESP32-CAM is equally lightweight and UAV-embeddable but lacks onboard computation capability.

Despite the existence of multiple object detection models, most with higher accuracy, the model used here is optimized for low-power microcontrollers, making it ideal for such systems. Compared to more powerful approaches, this solution enables basic filtering or detection tasks with minimal resource consumption and integration with the Arduino ecosystem.

Experimental implementation and validation of the system, based on UAVs equipped with Arduino Portenta boards and lightweight deep learning models, demonstrated the feasibility of real-time traffic monitoring and classification tasks directly at the edge, without cloud computing infrastructure dependency. Results show that integrating edge computing techniques in embedded systems can be an efficient and scalable alternative to traditional monitoring methodologies, which require significant investment in fixed equipment and greater connectivity dependency. As the system’s focus is to classify and structure visual information in real time, two systems capable of this task were developed, implementing image, geolocation, and timestamp data acquisition modules using the different boards.

Arduino Portenta boards demonstrated their ability to capture real-time images and perform basic object detection, unlike the ESP32-CAM system, which, while able to capture data, required an additional processing node for filtering, despite both using lightweight TensorFlow Lite models (185 kB for vehicle detector, 293 kB for people detector). These lightweight models were correctly implemented on memory-constrained devices and more powerful systems, with the latter enabling a more precise model capable of detecting object positions. This results in longer response times but improved data classification.

The two architectures evaluated in this study must be understood as complementary layers of a full deployment stack. In scenarios with reliable backhaul and powerful ingestion servers, the ESP32-CAM-MQTT-Kafka-Beam-MongoDB pipeline (as validated in [27]) enables centralized processing and large-scale analytics; however, our experiments show that edge inference on Portenta reduces transmission load and latency, which is critical where connectivity is intermittent. Combining both approaches (TinyML filtering on the UAV and configurable resolution/throttling policies enforced at the capture node) yields the best trade-off between data quality, energy use, and ingestion throughput.

The power consumption analysis shows that the Portenta system requires 1.035 W during active inference, while the ESP32-CAM consumes 1.36 W during image transmission. This difference has direct implications for UAV endurance: with a typical 4000 mAh UAV battery, the Portenta configuration would extend endurance by approximately 205 min compared to the alternative. Moreover, UAV flight time is inherently limited (≈20–30 min). Strategies to mitigate this include hardware optimization, efficient mission planning, and modular payload design.

Finally, the two systems should not be viewed in isolation but as complementary to a scalable backend ingestion pipeline. By combining onboard TinyML filtering (reducing unnecessary transmissions) with server-side compression and throttling policies validated in [27], deployments can balance autonomy, bandwidth usage, and long-term analytic requirements.

Application scenarios include those not requiring immediate response, where data can be integrated into the system for later analysis after mission completion. Another use case is rapid preprocessing by sending relevant extracted image information, especially useful for detecting people on road sections or vehicles in restricted access areas.

Future work includes updating Arduino Portenta board firmware to enable external library incorporation, switching from MicroPython to Arduino’s native C to leverage available data processing libraries. The system should also be optimized to increase inference capacity with lightweight ML models, always considering inherent storage and transmission limitations.

To make the trade-offs between the two architectures more explicit, we summarized the main usage scenarios and the corresponding recommended configuration in Table 6. This comparative view highlights when the Arduino Portenta (edge inference) or the ESP32-CAM (remote processing) is more appropriate, based on connectivity conditions, energy constraints, and accuracy requirements.

Table 6.

Recommended scenarios for each architecture.

As shown in Table 6, the two architectures should not be viewed as competitors but as complementary solutions. The Portenta-based edge system is best suited for autonomy and endurance, while the ESP32-CAM architecture is optimal when network resources and server capabilities are available. Hybrid deployments can combine both advantages, using onboard filtering to reduce data volume and server-side inference for higher accuracy.

6. Conclusions

This work compared two UAV-based data acquisition architectures for automated roads: (i) an Arduino Portenta H7 solution with edge inference and (ii) an ESP32-CAM system with remote processing. Experiments demonstrated that the Portenta-based approach reduces energy consumption by 36.2% and latency by ~9% compared to the alternative, making it suitable for connectivity-constrained scenarios. The ESP32-CAM approach simplifies hardware and facilitates rapid model updates. Together, these architectures provide complementary solutions for scalable, real-world ITS deployments. Future work will focus on integrating the edge nodes with our big-data ingestion pipeline (Kafka + Beam + MongoDB) to assess end-to-end performance under realistic network conditions.

Author Contributions

J.G.-G. was responsible for the design of the system architecture and the validation of the final prototype, performed the experiments, analyzed the results, and wrote part of the paper. C.Q.G.M. was responsible of project administration and funding acquisition and wrote part of the paper. D.G.P. wrote part of the paper. J.S.-S. supervised the research, specified the method, conceived the evaluation procedure, analyzed the results, organized and wrote part of the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Universidad Francisco de Vitoria, grant number UFV2025-16 “Optimization of autonomous drone navigation for the generation of adaptive 3D meshes using advanced reinforcement learning techniques”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are openly available in https://zenodo.org/record/5776219, 9 September 2025 at https://doi.org/10.3390/data7050053, reference number [34].

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Universidad Francisco de Vitoria, the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid and the Universidad Europea de Madrid for their support. Also, Lucia Doval is thankful for her invaluable help with the experiments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Saini, K.; Sharma, S. Smart Road Traffic Monitoring: Unveiling the Synergy of IoT and AI for Enhanced Urban Mobility. ACM Comput. Surv. 2025, 57, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanffy, L.; Lorinț, C.R.; Nicola, A. Development of a Low-Cost Traffic and Air Quality Monitoring Internet of Things (IoT) System for Sustainable Urban and Environmental Management. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Khattak, K.S.; Khan, Z.H.; Gulliver, T.A.; Abdullah. Edge Computing for Effective and Efficient Traffic Characterization. Sensors 2023, 23, 9385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yass, W.G.; Faris, M. Integrating computer vision, web systems and embedded systems to develop an intelligent monitoring system for violating vehicles. Babylon. J. Internet Things 2023, 2023, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portenta H7. Arduino Documentation. Available online: https://docs.arduino.cc/hardware/portenta-h7/ (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- Jiménez, A.A.; Márquez, F.P.G.; Moraleda, V.B.; Muñoz, C.Q.G. Linear and nonlinear features and machine learning for wind turbine blade ice detection and diagnosis. Renew. Energy 2019, 132, 1034–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.A.; Jhanjhi, N.; Brohi, S.N.; Usmani, R.S.A.; Nayyar, A. Smart traffic monitoring system using Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs). Comput. Commun. 2020, 157, 434–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butilă, E.V.; Boboc, R.G. Urban Traffic Monitoring and Analysis Using Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs): A Systematic Literature Review. Remote. Sens. 2022, 14, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosende, S.B.; Ghisler, S.; Fernández-Andrés, J.; Sánchez-Soriano, J. Implementation of an Edge-Computing Vision System on Reduced-Board Computers Embedded in UAVs for Intelligent Traffic Management. Drones 2023, 7, 682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christodoulou, C.; Kolios, P. Optimized tour planning for drone-based urban traffic monitoring. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 91st Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC2020-Spring), Antwerp, Belgium, 25–28 May 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Ectors, W.; Bellemans, T.; Janssens, D.; Wets, G. UAV-Based Traffic Analysis: A Universal Guiding Framework Based on Literature Survey. Transp. Res. Procedia 2017, 22, 541–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanmaz, E.; Quaritsch, M.; Yahyanejad, S.; Rinner, B.; Hellwagner, H.; Bettstetter, C. Communication and Coordination for Drone Networks. In Proceedings of the Ad Hoc Networks: 8th International Conference, ADHOCNETS 2016, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 26–27 September 2016; pp. 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashqer, M.I.; Ashqar, H.I.; Elhenawy, M.; Almannaa, M.; Aljamal, M.A.; Rakha, H.A.; Bikdash, M. Evaluating a Signalized Intersection Performance Using Unmanned Aerial Data. Preprint 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Soriano, J.; De-Las-Heras, G.; Puertas, E.; Fernández-Andrés, J. Sistema Avanzado de Ayuda a la Conducción (ADAS) en rotondas/glorietas usando imágenes aéreas y técnicas de Inteligencia Artificial para la mejora de la seguridad vial. Logos Guard. Civ. Rev. Científica Cent. Univ. Guard. Civ. 2023, 1, 241–270. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, H.; Post, J.; Kourtellis, A.; Porter, B.; Zhang, Y. Comparison of Object Detection Algorithms Using Video and Thermal Images Collected from a UAS Platform: An Application of Drones in Traffic Management. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2109.13185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, A.; Abid, U.; Gemma, L.; Perotto, M.; Brunelli, D. TinyML Platforms Benchmarking. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Applications in Electronics Pervading Industry, Environment and Society, Pisa, Italy, 21–22 September 2021; pp. 139–148. [Google Scholar]

- Gorospe, J.; Mulero, R.; Arbelaitz, O.; Muguerza, J.; Antón, M.Á. A Generalization Performance Study Using Deep Learning Networks in Embedded Systems. Sensors 2021, 21, 1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David, R.; Duke, J.; Jain, A.; Reddi, V.J.; Jeffries, N.; Li, J.; Kreeger, N.; Nappier, I.; Natraj, M.; Wang, T.; et al. TensorFlow Lite Micro: Embedded Machine Learning for TinyML Systems. In Proceedings of the Conference on Machine Learning and Systems, Virtual, 5–9 April 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Parashar, A.; Rhu, M.; Mukkara, A.; Puglielli, A. SCNN: An Accelerator for Compressed-sparse Convolutional Neural Networks. ACM SIGARCH Comput. Archit. News 2017, 45, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosende, S.B.; Fernández-Andrés, J.; Sánchez-Soriano, J. Optimization Algorithm to Reduce Training Time for Deep Learning Computer Vision Algorithms Using Large Image Datasets With Tiny Objects. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 104593–104605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Jang, S.-J.; Park, J.; Lee, E.; Lee, S.-S. Lightweight and Energy-Efficient Deep Learning Accelerator for Real-Time Object Detection on Edge Devices. Sensors 2023, 23, 1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, L.A.; Leithardt, V.R.Q.; Batista, V.F.L.; González, G.V.; Santana, J.F.D.P. Automated Road Damage Detection Using UAV Images and Deep Learning Techniques. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 62918–62931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dokic, K.; Martinovic, M.; Mandusic, D. Inference speed and quantisation of neural networks with TensorFlow Lite for Microcontrollers framework. In Proceedings of the 2020 5th South-East Europe Design Automation, Computer Engineering, Computer Networks and Social Media Conference (SEEDA-CECNSM), Corfu, Greece, 25–27 September 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aatab, S.; Freitag, F. Towards a Library of Deep Neural Networks for Experimenting with on-Device Training on Microcontrollers. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 9th World Forum on Internet of Things (WF-IoT), Aveiro, Portugal, 12–27 October 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MQTT: The Standard for IoT Messaging. Available online: https://mqtt.org/ (accessed on 31 May 2025).

- Individual mozilla.org Contributors. HTTP: Hypertext Transfer Protocol 2025. Available online: https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/HTTP (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- García-González, J.; Fernández-Andrés, J.; Aliane, N.; Sánchez-Soriano, J. Big Data and I2X Communication Infrastructure for Traffic Optimization and Accident Prevention on Automated Roads. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 133497–133509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raspberry Pi Ltd. Raspberry Pi Hardware. Available online: https://www.raspberrypi.com/documentation/computers/raspberry-pi.html (accessed on 31 May 2025).

- Portenta Vision Shield. Available online: https://docs.arduino.cc/hardware/portenta-vision-shield/ (accessed on 31 May 2025).

- MKR GPS Shield. Available online: https://docs.arduino.cc/hardware/mkr-gps-shield/ (accessed on 31 May 2025).

- ESP32 Camera Component. Available online: https://esphome.io/components/esp32_camera.html (accessed on 31 May 2025).

- Apache Software Foundation. Kafka 4.0 Documentation. Available online: https://kafka.apache.org/documentation/ (accessed on 31 May 2025).

- Rosende, S.B.; Ghisler, S.; Fernández-Andrés, J.; Sánchez-Soriano, J. Dataset: Traffic Images Captured from UAVs for Use in Training Machine Vision Algorithms for Traffic Management. Data 2022, 7, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banbury, C.R.; Reddi, V.J.; Lam, M.; Fu, W.; Fazel, A.; Holleman, J.; Huang, X.; Hurtado, R.; Kanter, D.; Lokhmotov, D.; et al. Benchmarking TinyML Systems: Challenges and Direction. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2003.04821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warden, P.; Situnayake, D. TinyML: Machine Learning with TensorFlow Lite on Arduino and Ultra-Low-Power Microcontrollers; O’Reilly Media: Sebastopol, CA, USA, 2019; Available online: https://books.google.es/books?id=tn3EDwAAQBAJ (accessed on 26 June 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).