Abstract

The Internet of Medical Things (IoMT) comprises the application of traditional Internet of Things (IoT) technologies in the healthcare domain. IoMT ensures seamless data-sharing among hospitals, patients, and healthcare service providers, thereby transforming the medical environment. The adoption of IoMT technology has made it possible to provide various medical services such as chronic disease care, emergency response, and preventive treatment. However, the sensitivity of medical data and the resource limitations of IoMT devices present persistent challenges in designing authentication protocols. Our study reviews the overall architecture of the IoMT and recent studies on IoMT protocols in terms of security requirements and computational costs. In addition, this study evaluates security using formal verification tools with Scyther and SVO Logic. The security requirements include authentication, mutual authentication, confidentiality, integrity, untraceability, privacy preservation, anonymity, multi-factor authentication, session key security, forward and backward secrecy, and lightweight operation. The analysis shows that protocols satisfying a multiple security requirements tend to have higher computational costs, whereas protocols with lower computational costs often provide weaker security. This demonstrates the trade-off relationship between robust security and lightweight operation. These indicators assist in selecting protocols by balancing the allocated resources and required security for each scenario. Based on the comparative analysis and a security evaluation of the IoMT, this paper provides security guidelines for future research. Moreover, it summarizes the minimum security requirements and offers insights that practitioners can utilize in real-world settings.

1. Introduction

The rising average age of the global population is accompanied by an increasing incidence of chronic disease. This trend is significantly increasing the demand for efficient healthcare services. The adoption of intelligent healthcare systems is essential if systems are to meet this demand. In this landscape, the Internet of Medical Things (IoMT) is emerging as a next-generation technology for healthcare services. The IoMT supports patient-health management through remote consultations and timely interventions. It is expected to play a significant role in improving the quality, efficiency, and sustainability of healthcare services.

First, the IoMT is transforming service delivery across both clinical and home settings. Point-of-care diagnostic tools enable clinicians to perform rapid tests in hospitals and outpatient facilities, while remote monitoring extends these benefits to home care, allowing continuous health tracking without disruption of daily life [1]. In addition, the IoMT enhances the efficiency of hospital operations and resource management by monitoring various resources, including equipment, medicines, and consumables, in real time. This enhances the efficiency of supply-chain management through intuitive status monitoring and automated ordering and linking. The IoMT provides interoperability by integrating medical devices with different standards. This allows for a consistent supply of medical data, enabling clinicians to access necessary information in real time. These capabilities enable the delivery of high-quality healthcare services such as preventive medicine, management of chronic disease, emergency response, and continuous monitoring.

However, despite these advantages, the scalability of the IoMT exposes new security vulnerabilities. Because most IoMT devices are network-connected, the attack surface is significantly expanded compared to traditional healthcare environments. Attacks on medical data go beyond simple information leaks and directly impact patient lives. These threats clearly demonstrate the need for a security framework tailored to the IoMT environment. Existing IT security systems are inadequate for the unique needs of healthcare environments and the characteristics of IoMT devices, requiring the development of an encryption strategy tailored to IoMT systems [2].

Secure and reliable data transmission is a key element supporting IoMT performance. Sensors and medical devices continuously generate sensitive health data. This data flow must simultaneously meet needs related to confidentiality, integrity, low latency, and energy efficiency. Some errors can pose threats to patient health. Furthermore, inadequate security measures to ensure authentication, confidentiality, and integrity make data exchange vulnerable, posing a serious threat to the protection of sensitive medical information [3]. Therefore, it is essential to verify the efficiency and security of IoMT communication protocols. The main contributions of the paper are as follows:

- (i)

- Conducting systematic and objective comparative analysis of recent IoMT security protocols to quantitatively evaluate their performance and security metrics.

- (ii)

- Verifying the recent IoMT security protocols to derive essential security requirements for IoMT environments.

- (iii)

- Providing security guidelines for future research based on the results of comparative analysis and security assessment.

2. Background

The IoMT has evolved in recent years through the integration of IoT technology into medical device systems and services. While the general IoT connects common objects such as home appliances and vehicles, the IoMT specifically links clinical devices that monitor vital signs and administer treatments [4]. This evolution has been driven by advances in low-power wireless communication and edge computing technologies, which hospitals and healthcare institutions have adopted to enhance service quality and accessibility [5].

2.1. IoT and IoMT

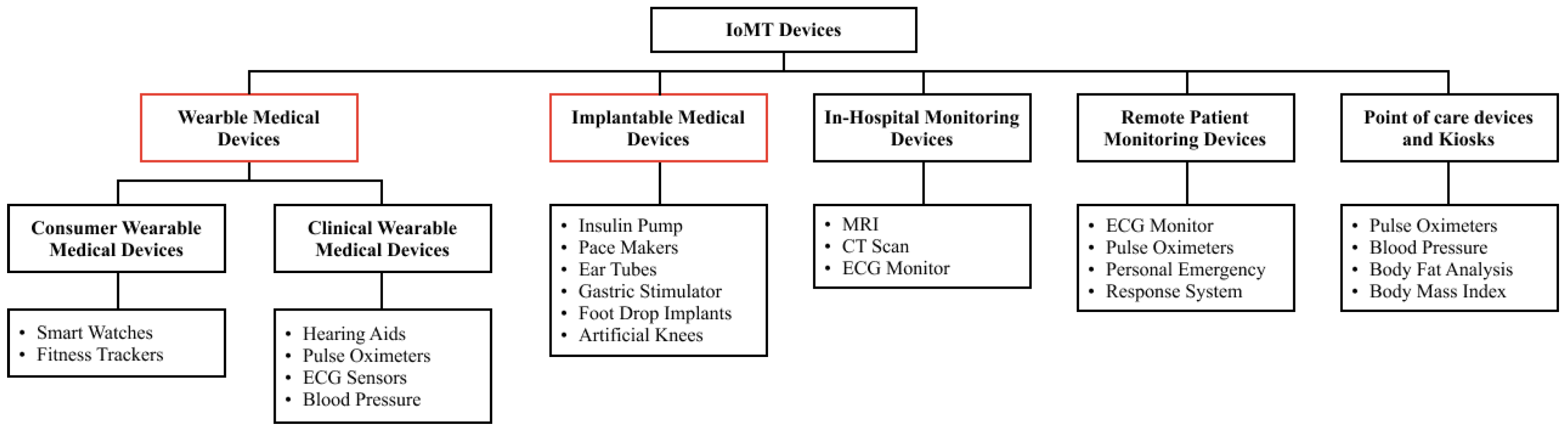

Figure 1 shows IoMT device classification. The IoT interconnects distinct physical entities, enabling embedded sensors and software to exchange data with edge and cloud platforms. Extending these principles into the clinical domain, the IoMT operates within care workflows to enable real-time monitoring, remote patient management, and early detection of anomalies, thereby improving patient outcomes through continuous monitoring, personalized treatment, and telemedicine [6,7]. The IoMT encompasses patient-worn devices (e.g., smartwatches, biosensor patches), hospital-deployed assets (e.g., smart beds, infusion pumps), and implantable systems that stream remote telemetry or deliver closed-loop therapies (e.g., pacemakers, neurostimulators) [8]. The IoMT sector continues to expand as companies consistently release specialized sensors and advanced monitoring tools. Unlike the general-purpose IoT, the IoMT handles sensitive health data, making robust security essential.

Figure 1.

Classification of IoMT devices.

IoMT devices can fall into two main categories: Implantable Medical Devices (IMDs) and Internet of Wearable Devices (IoWDs) [9]. IMDs primarily support long-term monitoring or treatment by directly interfacing with human tissue, whereas IoWDs operate externally to collect and transmit physiological data [10,11].

Cardiovascular IMDs: Implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs) detect and correct arrhythmias [12]. Left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) help maintain blood circulation in patients with severe heart failure [13].

Neurological IMDs: Deep brain stimulators (DBS) send electrical impulses to targeted brain regions to treat conditions such as Parkinson’s disease and epilepsy. Clinicians use spinal cord stimulators (SCS) to manage chronic pain. Vagus nerve stimulators (VNS) assist in managing seizures and mood disorders [14,15,16].

Metabolic and Endocrine IMDs: Implantable insulin pumps regulate blood glucose in diabetic patients [17,18].

Respiratory and Pulmonary IMDs: Diaphragm stimulators aid patients with respiratory conditions. Implantable airway sensors monitor airflow and detect abnormalities [19,20].

The use of IMDs involves challenges, including limited battery life, vulnerabilities associated with wireless communication interfaces, and risks to patients’ data privacy. The advancement of IMDs depends on reliable energy management, secure low-power communication, and compliance with healthcare safety and cybersecurity requirements. These factors remain critical challenges throughout the design, certification, and deployment of IMDs [21,22].

IoWDs function externally as a noninvasive alternative, collecting physiological data for continuous, near-real-time monitoring. They transmit this data to clinical information systems to support preventive care, long-term management of chronic conditions, and remote oversight. This process provides patients with timely feedback and reduces reliance on in-person visits [10].

Vital-Sign-Monitoring Wearables: Devices such as smartwatches and fitness trackers measure heart rate. They also track oxygen saturation (SpO2), body temperature, and sleep patterns. Wearables equipped with ECG functions detect irregular heart activity [23].

Glucose-Monitoring Wearables: Continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) sensors measure blood glucose levels. They provide real-time feedback to diabetic patients [24].

Smart Clothing and Adhesive Health Patches: ECG-enabled garments, such as smart shirts, monitor cardiovascular activity. Smart patches measure hydration, detect temperature variations, and analyze sweat composition [25,26].

Neurological Wearables: Brain–computer interface (BCI) devices analyze brain activity to support cognitive training and neurotherapy [27].

Although IoWDs are noninvasive, they present challenges, most notably in measurement accuracy, which varies depending on wearing conditions and device-specific characteristics. Furthermore, security threats such as data leakage and tampering, which can directly impact patient safety, must also be addressed. In this context, IoMT systems continuously generate vast amounts of patient-specific clinical data. To manage the complexity of IoMT systems, a layered architecture has been adopted. While various architectures exist, their components can be categorized into three core layers: perception, network, and application [28,29].

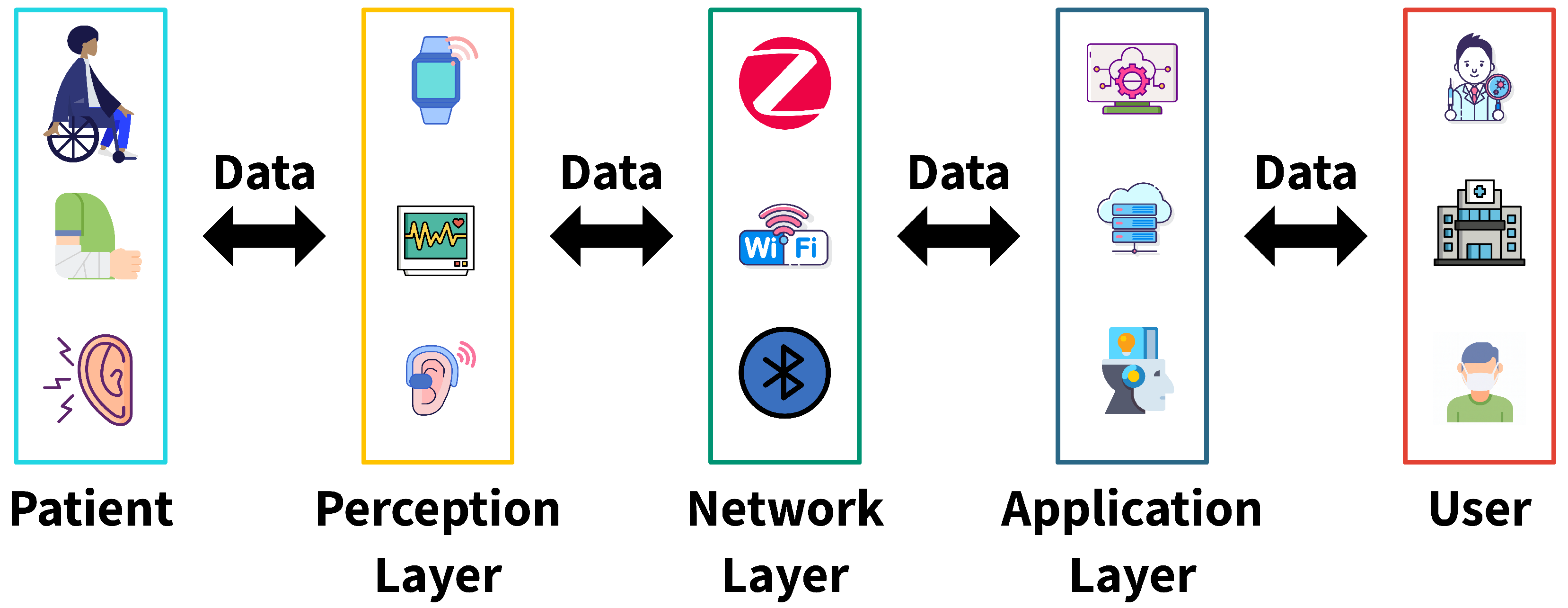

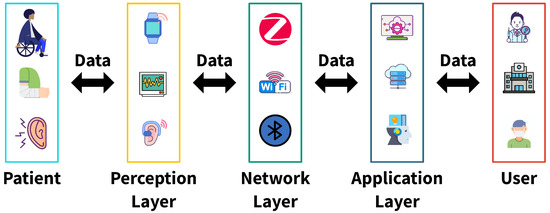

Figure 2 shows the hierarchical architecture of the IoMT. Patients access medical devices through the perception layer. This layer collects data and transmits it to the application layer via the network layer. The application layer stores the data and preprocesses it so that medical professionals can effectively utilize it.

Figure 2.

Layered architecture of the IoMT.

The perception layer handles all components that capture medical data at the source. It includes wearable health monitors, implantable devices, and hospital-grade diagnostic machines. These instruments collect raw physiological data, such as heart rate, oxygen saturation, glucose concentration, and other vital indicators. Wearable sensors play a central role in this layer. Devices such as smartwatches and biosensor patches continuously track the condition of a patient without disrupting daily routines. In addition to acquisition, many devices perform basic processing by filtering noise, compressing signals, and detecting abnormalities before transferring the processed information to the network layer [29].

The network layer is the intermediate layer connecting the perception layer and the application layer in the IoMT architecture. It securely and quickly transmits data collected by sensors to hospital servers, cloud platforms, or healthcare service providers. The primary purpose of this layer is to ensure data confidentiality, integrity, and availability during transmission while maintaining the real-time performance essential in healthcare environments and ensuring seamless connectivity. These functions are essential for ensuring uninterrupted data transmission, especially in life-threatening situations. In addition, edge computing devices are deployed at the network layer to reduce communication delays with cloud servers and enable immediate local processing of urgent data [30].

As the upper layer, the application layer aggregates data received from the network layer and delivers it to healthcare providers. This layer enables remote monitoring and control in medical settings, facilitates real-time assessment of a patient’s condition, and supports physicians in making data-driven diagnoses and treatment decisions. User interfaces, including the software and applications used at the application layer, play a critical role in managing the increasing complexity of system administration [31].

2.2. IoMT Communication Protocols

IoMT systems employ multiple communication protocols to connect devices, networks, and applications. Each component requires a suitable method for data transmission. At the perception layer, where data collection occurs, short-range protocols are common. RFID tags track medical equipment in hospitals. They are small and inexpensive and do not require batteries. A reader emits a signal, and the tag returns the information. NFC operates in a similar way but requires close contact (within a few centimeters). Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) is widely used in wearable devices because it minimizes power consumption. Most fitness trackers and health monitors rely on BLE to connect with smartphones [32]. ZigBee conserves energy and supports mesh networking, making it suitable for large-scale IoMT integration [33]. For longer distances, Wi-Fi is frequently deployed in hospitals due to its high transmission speed, although it consumes more power. Remote monitoring systems often adopt cellular networks such as 4G and 5G, especially for patients at home [34]. These connections enable clinicians to observe a patient’s condition without in-person visits. At the application layer, different protocols manage collected data. MQTT provides lightweight many-to-many communication through a publish–subscribe model. It reduces network overhead and supports three quality-of-service (QoS) levels for varying reliability requirements [35]. Constrained Application Protocol (CoAP) serves as another option and is particularly effective for devices with limited processing capacity [36]. Healthcare systems also apply standards such as Health Level 7 (HL7) to ensure consistent interpretation of medical information across institutions [37]. Standardization plays a critical role in enabling interoperability among hospitals and healthcare providers.

Protocol selection depends on device power capacity, data volume, and security requirements. Security remains a central concern due to the sensitivity of medical data. Each system layer must apply strong encryption and authentication mechanisms to guarantee secure access. An appropriate combination of these protocols enables real-time monitoring, health-trend analysis, and remote care delivery while meeting strict regulatory standards.

3. Recent Research

3.1. Literature Review

In this section, we review recent research on the IoMT. The papers cover the architecture of the IoMT, future directions, security requirements, and the authentication protocol or enhanced authentication protocol. A description of each paper is provided below, and Table 1 summarize these results.

Table 1.

Summary.

According to Askar et al. [38], the IoMT is a concept that uses IoT technology to improve healthcare systems to make them smarter and more proactive. The IoMT can integrate new technologies such as ML, Blockchain, Fog, and edge computing to provide benefits such as faster treatment, improved communication, and cost reduction. This research analyzes analyzes various IoMT technologies and solutions built on these paradigms and presents possible directions for future development and applications.

Razdan et al. [39] noted that IoMT-based healthcare systems improve the quality of life of all stakeholders, not just patients. However, there are challenges such as power consumption, energy efficiency, security and privacy, high data-transmission rates, and low latency. To solve these problems, researchers are developing technologies that integrate ML, blockchain, fog, and edge computing, and emphasize that these technologies are essential if we are to improve the performance and enhance the security of IoMT healthcare systems. This paper analyzes the current status and potential future applications of IoMT systems that leverage the latest technologies and suggests future research directions and innovative application cases to advance the healthcare industry.

Ghubaish et al. [41] find that the rapid development of micro-computing, mini-hardware manufacturing, and M2M communication has made it possible to reconfigure many networking applications with new IoT solutions. An IoMT system can remotely monitor patients with chronic diseases. Therefore, the IoMT can provide timely patient diagnoses that can save lives in emergency situations. However, the security of these critical systems is a major challenge facing their widespread use.

Hatzivasilis et al. [42] show that security threats are increasing because patients and healthcare professionals process healthcare data using their own devices through Bring Your Own Device (BYOD) use cases. The latest security and privacy controls in the IoMT environment aim to address this problem. On combining IoMT and CE, users can expect improved accessibility, cost reduction, rapid implementation, and improved efficiency. In conclusion, this paper presents key security-control measures to protect CE-based IoMT systems and provides practical guidelines for enhancing security and privacy.

Bhushan et al. [43] show that the use of the IoMT has brought about great changes in healthcare through the deployment of universal and inexpensive devices. However, they suggest limitations on the adoption of IoMT devices due to security and privacy issues. This paper emphasizes the importance of core security measures for securing IoMT systems and enhancing interconnectivity between healthcare domains to address these limitations. The paper identifies three principal security technologies applicable to the IoMT environment: asymmetric key algorithms, which ensure robust data protection and authentication; symmetric key algorithms, which offer fast and efficient data encryption; and keyless algorithms, which fulfill the security requirements of IoMT systems through non-traditional mechanisms.

Alsubaei et al. [40] assert that in the IoMT environment, security and privacy issues are considered serious due to the presence of various IoMT devices that transmit sensitive medical data to the cloud. Consequently, IoMT security assessments and the selection of appropriate protection measures are important, but can be difficult for users who lack security knowledge. To address this, the authors propose a security-assessment framework that can recommend security features for the IoMT and evaluate their protection and deterrence capabilities. This provides practical experience in IoMT security, promotes competition by enabling security solution providers to verify and evaluate product security, and promotes the design of IoMT solutions that reflect the security measures required by consumers.

Abdussami et al. [44] argue that sensitive data related to patient health are vulnerable to attacks. The authors propose an architecture utilizing cloud servers and edge-computing technologies suitable for local and emergency scenarios. The Provably Secured Lightweight Authenticated Key Agreement Protocol (PSLA2P) is a lightweight authentication and key-agreement protocol that can be deployed in the proposed network architecture for the modern health industry. It protects data privacy by providing anonymity, untraceability, and integrity to the patient. In this paper, we prove that the PSLA2P protocol is secure through Scyther formal verification. Through performance evaluation, we show that it is superior to other approaches in terms of computational cost, communication cost, and security features.

Qiu et al. [45] propose a lightweight mutual-authentication method using blockchain to improve privacy protection and secure communication. The protocol uses elliptic curve cryptography (ECC) and the Chinese remainder theorem (CRT) to perform identity authentication efficiently. It also uses non-fungible tokens (NFTs) to make identity information on the blockchain immutable and verifiable. To enhance security, it applies two-factor authentication by combining certificate-based verification with physically unclonable functions (PUF). Security analysis using AVISPA confirms resistance to replay attacks and man-in-the-middle attacks. Performance evaluation shows low communication and storage costs, making it usable on resource-limited devices. Ethereum-based simulations and hyperledger caliper load tests were conducted to verify practicality. However, risks such as device hijacking, vulnerabilities in centralized identity management, and delays in NFT registration remain.

According to Lo et al. [46], current authentication methods used in the IoMT in the healthcare sector rely on simple passwords. They lack additional layers of protection, posing a risk of data breaches. Furthermore, they are inadequately protected against threats posed by quantum computing. To address this issue, we propose a lightweight authentication protocol based on post-quantum cryptography. This aims to ensure the confidentiality and integrity of medical data while verifying the identities of users and devices. To defend against quantum computing attacks, lattice-based cryptography, a quantum-safe encryption method, can be utilized. The structure of lattices is based on mathematical challenges such as the shortest vector problem (SVP), closest vector problem (CVP), and learning with errors (LWE), which can serve as the foundation for future post-quantum cryptography. By applying lightweight lattice-based cryptography (LBC) to IoMT authentication protocols, the protocol can not only withstand quantum attacks, but also provide strong security against them. It also offers the key-generation efficiency critical for the performance and scalability of IoMT devices, enhances two-factor authentication, and improves user convenience during authentication.

Masud et al. [47] proposes the MASK (mutual authentication and secret key) protocol, which verifies the reliability of sensor nodes and users and defends against physical attacks using PUF. The MASK protocol guarantees key security properties such as mutual authentication, data confidentiality, integrity, anonymity, untraceability, and physical security. Performance evaluation shows that the protocol minimizes computation based on PUF, reducing the burden and keeping sensor nodes’ energy consumption and memory usage lower than they are in existing protocols. It also reduces the number of message exchanges to minimize network delay and power consumption. However, the MASK protocol has some limitations.

Miao et al. [48] propose a blockchain-based privacy-protection authentication-management protocol to address IoMT device vulnerabilities in open network environments. The proposed protocol introduces blockchain into the protocol to store device identity and authentication-key information. In addition, security is guaranteed through Chebyshev chaos maps. In this paper, security is proven through a random oracle model and BAN logic. The protocol is shown to resist attacks and result in various security properties. The results of functional comparison and performance analysis show that the proposed protocol has advantages for IoMT devices in terms of security, computational overhead, communication overhead, and storage overhead. However, the consideration is limited to the storage aspect through the application of blockchain. The response time, the efficiency of the blockchain consensus algorithm, and the method of bypassing TA to fully utilize a distributed ledger technology are not considered. Therefore, it is shown that blockchain mechanisms should be thoroughly studied in the future and that an efficient and secure authentication protocol should be designed.

Garg et al. [49] propose a new blockchain-based authentication and key-management protocol (BAKMP) for IoMT environments. The BAKMP provides secure key management between different communication entities. Authorized users can access medical data in a secure manner from the cloud server. All of the medical data are stored in a blockchain maintained by the cloud server. The BAKMP can resist security-vulnerability attacks such as replay attacks, man-in-the-middle attacks, impersonation attacks, and ephemeral secret leakage (ESL) attacks. The proposed protocol demonstrates security against various types of attacks through AVISPA. In addition, it shows better performance in terms of communication and communication costs in the security, authentication, and key-management phases compared to existing schemes.

Pradhan et al. [50] proposes a multi-authentication protocol based on blockchain and ECC. For security verification, ProVerif and BAN logic were used to demonstrate resistance against various attacks. Slither was utilized for smart contract-vulnerability analysis, and no known security vulnerabilities were found. Experimental results comparing the proposed method with existing approaches showed improved computational and communication performance, demonstrating its applicability in resource-constrained environments. However, limitations remain, such as transaction costs due to blockchain usage, higher communication overhead compared to competing protocols, and difficulties in resetting biometric authentication data if compromised. Therefore, further optimization and expansion are needed to enhance applicability in real medical environments.

Gautam et al. [51] thoroughly analyzed the authentication protocol for IoMT remote patient monitoring proposed by Chen et al. [52] and found that Chen’s protocol is vulnerable to various security threats. Chen et al. relies on a random Nonce generated by all entities for the security of the session key. Since any random Nonce can be computed by utilizing publicly transmitted messages, the protocol is vulnerable to session key attacks. The protocol proposed here addresses these shortcomings through the use of an ECC algorithm and encryption and hashing methods. The improved protocol shows resistance to various attacks such as insider attacks, replay attacks, impersonation attacks, man-in-the-middle attacks, ephemeral secret leakage attacks, and session key-disclosure attacks.

Su et al. [53] propose a new user-authentication protocol, 3ECAP, which considers both security and efficiency in the IoMT environment. To these ends, 3ECAP adopts a three-factor authentication method combining passwords, biometric information, and smart cards and prevents privilege-escalation attacks through fine-grained access control using a Merkle tree. Here’s a lightly polished version of your sentence for clarity and flow while keeping all technical details:

Furthermore, 3ECAP primarily relies on hash operations to minimize computational and communication overhead, and its security has been validated through formal analysis using ProVerif. A comparative analysis with existing authentication protocols confirmed that 3ECAP maintains low computational and communication costs while providing higher security. In particular, it allows users to update their biometric information and passwords, supports the addition of new sensor devices, and maintains both forward and backward security, which are important in the IoMT environment.

Deebak et al. [54] proposed a lightweight two-factor authentication framework (L2FAK) with privacy-preserving capability that utilizes mobile sinks for smart eHealth. In the S-IoMT environment, data-privacy protection and device security are essential factors. L2FAK utilizes mobile sinks to manage these security issues. L2FAK prevents potential threats such as privileged insider Additionally, L2FAK ensures secure mutual authentication and session key agreement, demonstrating resistance to user and gateway impersonation, privileged insider attacks, and replay attacks. L2FAK reduces computational costs and minimizes operational expenses, enhancing the performance of real-time systems. It employs lightweight computations to improve efficiency in system authentication and key agreement stages, achieving superior transmission efficiency and lower overhead compared to conventional methods.

3.2. Evaluation

Security requirements provide the foundation for evaluating the robustness of authentication protocols in IoMT environments. The core security requirements typically encompass authentication, mutual authentication, confidentiality, integrity, untraceability, privacy preservation, anonymity, multi-factor authentication, session key security, forward/backward secrecy, and lightweight operation. In addition, advanced requirements—including quantum resistance and emergency response mechanisms—are becoming increasingly important in healthcare scenarios, where the protection of sensitive medical data and the capacity for timely response to urgent situations are critical.

As shown in Table 2, most existing protocols consistently support authentication, integrity, and confidentiality, which are regarded as the fundamental security properties. However, only a limited number of protocols implement mutual authentication, indicating that many designs still rely on one-way authentication, in which the server verifies the user but the user cannot validate the server. Such asymmetry increases susceptibility to phishing and man-in-the-middle attacks. Consequently, achieving two-way trust through mutual authentication is indispensable for practical and secure deployment.

Table 2.

Security requirements supported by each protocol [44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,53,54].

The elements listed under Security Requirement in Table 2 represent the minimum recommended attributes tailored for IoMT scenarios. The essential security elements that must be satisfied include authentication, confidentiality, and integrity. In addition, considering the characteristics of IoMT devices, secure session key, lightweight operation, privacy preservation, mutual authentication, and freshness are also included. These attributes can be more practically beneficial when practitioners use the devices. A secure session key is necessary to ensure the security of messages exchanged within the session, while lightweight operation is included because IoMT devices have limited resources in practice. Privacy preservation is required because the information involved pertains to personal health data. Mutual authentication and freshness are also included to ensure mutual verification and secure communication during operation.

Privacy protection is addressed in [51,54]. This highlights that safeguarding users’ sensitive information requires not only cryptographic encryption but also system-level mechanisms that mitigate metadata exposure and behavioral pattern tracking. Similarly, only a limited number of protocols [44,48,49,50,51,53] implement freshness to prevent replay attacks. In addition, only protocols [44,48,51] provide forward and backward secrecy, thereby ensuring the confidentiality of both past and future sessions even if a session key is compromised.

Beyond these classical requirements, emerging threats call for additional considerations. The rapid progress of quantum computing poses fundamental risks to ECC- and RSA-based systems, underlining the need for quantum-resistant cryptographic algorithms in future protocol designs. Moreover, emergency security requirements—such as authentication bypass or rapid identification in urgent scenarios—are largely overlooked in existing works, despite their practical relevance in medical contexts where emergencies are frequent.

These observations underscore the point that while current protocols address fundamental security requirements, future designs must evolve to incorporate advanced properties—including mutual authentication, privacy preservation, quantum resistance, and emergency handling—to achieve comprehensive security in IoMT environments.

Table 3 lists the types and number of operations used in this papers [44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,53,54], and Table 4 shows hardware specifications and software configurations. The protocols commonly include hash operations and XOR operations and additionally include operations such as public key-based operations, symmetric key operations, and key exchange, as needed. Some protocols also introduce special operations such as fuzzy extractors for biometric information security, modular operation PUFs, and Merkle tree operations.

Table 3.

Comparison of computational overhead.

Table 4.

Experimental Environment.

Looking at the characteristics of each protocol, Abdussami et al. [44] mostly use only hash and XOR operations to simplify the operation structure and pursues lightweight operation by performing RSA operations only once. Qiu et al. [45] provide high-level asymmetric security with many ECC-based key-generation and exchange operations, but the number of operations is large. Lo et al. [46] also use Diffie–Hellman and RSA operations in a balanced manner and show intermediate complexity. On the other hand, the work by Masud et al. [47] consists of only hash and XOR, so it can be said to be the most lightweight protocol.

Miao et al. [48] combine various elements in authentication by adding biometric information extraction (fuzzy extractor) and modular operations with the basic operations, and Garg et al. [49] strengthen basic security security primarily using hash operations, supplementing them by AES symmetric encryption and digital signature verification. Pradhan et al. [50] proposed a protocol that utilizes AES encryption along with hash functions and XOR operations. Gautam et al. [51] chose a structure that secures basic integrity and confidentiality by using only hash operations, AES, and a small number of DH operations in a relatively simple way.

Su et al. [53] developed a complex structure including ECC key exchange, AES, RSA, and signature verification, aiming to increase defense against various attacks at the same time. Finally, Deebak et al. [54] use PUF and Merkle tree operations in addition to hash operations, XOR, AES, and RSA to additionally ensure security and integrity in special environments such as the IoMT.

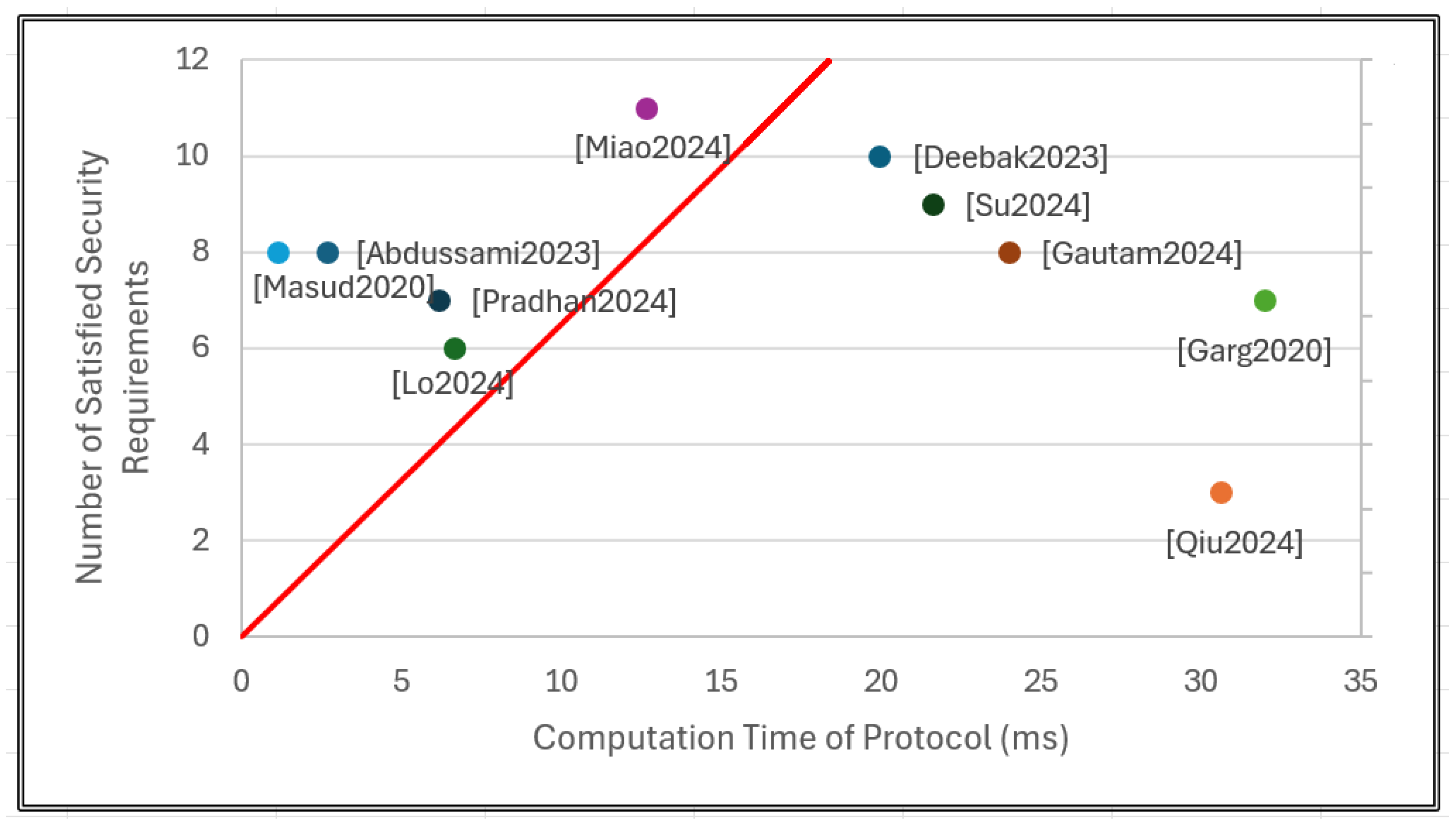

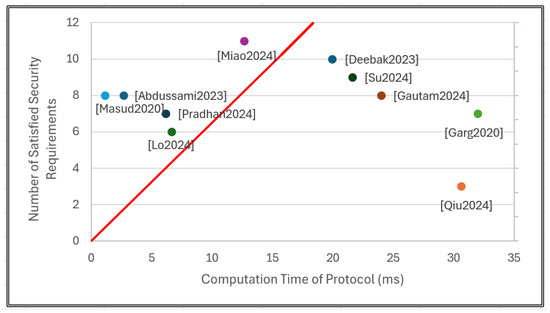

Figure 3 graphs the relationship between the computational time of each protocol and the number of security requirements satisfied. The x-axis represents the computational time (in milliseconds) required for each protocol, and the y-axis represents the number of security requirements satisfied. The trendline of the graph was derived by calculating the average slope of all data points. This provides an overall metric for evaluating the tradeoff between security and efficiency.

Figure 3.

Comparison of protocols by computational time and satisfaction of security requirements [44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,53,54].

From the graph, it can be observed that protocols positioned closer to the upper left side of the trendline achieve both higher security and greater computational efficiency. A position above and to the left of the trendline suggests that a protocol satisfies a relatively large number of security requirements while maintaining a lower computational burden, thus demonstrating superior performance. According to the graph, the protocol proposed by Miao et al. is especially notable.

This protocol satisfies a wide range of security requirements, demonstrating a high level of security. In addition, this protocol shows excellent efficiency, with a relatively low computational time compared to other protocols that provide similar security coverage. The balance between security strength and efficiency highlights the practical benefits of this protocol, making it a suitable candidate for environments where both high security and lightweight operation are important. In particular, the combination of lightweight design and meeting comprehensive security requirements shows that this protocol is well-suited for resource-constrained systems in IoMT or next-generation mobile networks.

4. Security Verification

In this section, we evaluate the security of existing proposed protocols and use formal verification tools to check whether each protocol satisfies the main security requirements. Formal verification is a method to comprehensively analyze the validity, safety, and reliability of a protocol through logical reasoning and checking via mathematical models [55]. In this paper, we verify various IoMT authentication protocols using representative formal techniques such as Scyther and SVO Logic. The verification procedure follows the Dolev–Yao adversary model, which assumes that the adversary can eavesdrop on, intercept, and synthesize any message.

For the detailed derivation of the SVO Logic reasoning steps and the Scyther verification process, please refer to the Supplementary Materials.

4.1. SVO Logic

SVO Logic has two rules of inference [56]:

- Modus Ponens: From and infer .

- Necessitation: From infer .

‘⊢’ is a meta-lingual symbol that is used in a logical system. ‘’ means that can derive from the formula (and the axioms given below), and this indicates that can be proven using and axioms. On the other hand, ‘’ means that is a theorem that can be derived using only axioms without additional assumptions or formulas, and this indicates that can be proven by itself in the logical system. Evaluation was carried out using SVO Logic notations in Table 5 and the axioms in Table 6, as follows.

Table 5.

SVO Logic Notation.

Table 6.

SVO Logic Axioms.

In this section, we present the result of Formal verification using SVO Logic for the 10 authentication protocols presented in this paper. In [44,48,49], the designed protocols clearly prove security through formal verification based on SVO Logic. The logical basis for secure session key exchange in each protocol is clearly presented. This is achieved through a structured reasoning process based on SVO Logic.

First, Abdussami et al. [44] supports mutual authentication and sharing of the secure session key with systematically derived steps such as (DA.4), (DA.5), (DA.9), (DA.13), (DA.17), and (DA.18), as given in the Appendix A of this study. These derivation steps validate that the session key is securely established between both entities. Specifically, in [48], steps (DE.11), (DE.16), and (DE.17), as given in the Appendix E of this study confirm the correctness of the key-exchange process. In particular, although the MSN’s indirect belief is not explicitly shown in the derivation step, it is confirmed that the authentication is stated as an assumption in (AE.14) of the Appendix E. This indicates that the MSN trusted the session key during the message-exchange process after the key had been shared.

Finally, in the case of [49], mutual authentication and secure session key exchange are clearly demonstrated. These properties are verified through a series of derivation steps, including (DF.5), (DF.10), (DF.15), (DF.20), (DF.21), and (DF.25), as given in the Appendix F of this study. As a result, the protocol is shown to be robust against key forgery and man-in-the-middle attacks.

In addition, each protocol satisfies forward/backward secrecy by deriving the session key through a combination of a hash function and a randomly generated number for each session. As illustrated in the session key-agreement process in [44], (DA.4), (DA.8), (DA.13), and (DA.17), as given in the Appendix A, from the derivation process, it can be inferred that each session key is generated independently using fresh randomness. This ensures that session keys are cryptographically isolated, preserving both forward and backward secrecy. In the [48], it is also derived in (DE.11), as given in the Appendix E of this study and (DE.16) that the session key is generated by a hash function with a new random number, which ensures key independence between sessions. In [49], the derivation steps (DF.5), (DF.10), (DF.15), and (DF.20), as given in the Appendix F of this study, confirm that the session key is freshly generated for each session. As the new key is not logically linked to any previous session, the protocol satisfies both forward and backward secrecy. In [50], the key agreement steps (DG.5) and (DG.12), as given in the Appendix G of this study, employ the session timestamp to generate a unique key value for each session. Consequently, the newly generated key value differs from that of the previous session, ensuring that the proposed protocol satisfies both PFS and PBS. In addition, by incorporating a mutual key verification process based on the session key in subsequent steps, the protocol is also verified to achieve the mutual authentication.

Whereas the protocols proposed in [45,51,53,54] appear to verify user identity through an authentication process on the surface, they lack a proper mutual authentication structure. This is revealed in the fact that session key verification was not performed, as the mutual trust in key sharing, which is one of the main security goals defined in SVO Logic, was not derived.

The SVO Logic verification of the protocols set goals for sharing and verifying session keys such as (GB.2), (GB.4), (GH.4), (GH.9), (GI.2), (GI.4), (GJ.3), and (GJ.6), as given in the Appendix B, Appendix H, Appendix I, and Appendix J of this study, but failed to derive the goals in the message-derivation phase.

In addition, the protocols proposed in [45,46,47,54] omit verification of the random numbers or timestamps included in messages, resulting in structural flaws that fail to prove message freshness. Consequently, these protocols are vulnerable to replay attacks. As a result of the formal verification, freshness-related assumptions were not explicitly adopted during the assumption phase in these protocols. Instead, they were expressed as hypotheses in forms such as (HB.1), (HB.2), (HB.3), (HC.1), (HC.2), (HD.1), (HD.2), (HD.3), and (HJ.1), as given in the Appendix B, Appendix C, Appendix D, and Appendix J of this study, indicating a lack of clear justification or evidence that these elements represent truly fresh values.

In SVO Logic, a hypothesis is treated as an assumption that lacks formal proof. As such, it cannot serve as a valid basis for deriving goals related to freshness, such as replay attack resistance or session key reliability. In other words, if freshness—one of the core security requirements—is not formally established, the protocol may become vulnerable to attacks involving the reuse of past messages, leading to threats such as session key exposure and authentication bypass.

In conclusion, the protocols proposed in [45,46,47,54] lack a systematic mechanism to formally prove message freshness. This limitation is evident in the SVO Logic analysis, where freshness-related assumptions are treated merely as unproven hypotheses. As a result, these protocols fail to achieve freshness-based security goals through formal reasoning, making them vulnerable to replay and time-based attacks and ultimately undermining their reliability as secure authentication protocols.

For transparency and reproducibility, we have included in the Appendix A, Appendix B, Appendix C, Appendix D, Appendix E, Appendix F, Appendix G, Appendix H, Appendix I and Appendix J the security verification we performed for all 10 protocols using SVO Logic: annotation, comprehension, interpretation, assumption, goal, and derivation.

4.2. Scyther

The Scyther tool is used to automatically verify the security properties of the protocol. For this purpose, the protocol is transformed into the Security Protocol Description Language (SPDL) and the participants (roles) are defined along with their corresponding behaviors, such as nonce generation, session key computation, and message transmission. Furthermore, claim() events are inserted within each role to determine whether the specified security requirements have been satisfied. Verification is carried out by modeling the protocol in SPDL and validating the achievement of the intended security goals through queries expressed in the form of claim() statements [57].

The Secret attribute is used to verify whether the confidentiality of a target element is preserved. When the Secret attribute is satisfied, the element is not exposed to the attacker even if it is transmitted over a public channel. The Secret attribute is used to check whether the confidentiality of specific data items is maintained within a protocol. The SKR attribute is similar to the Secret attribute, but it is specifically applied when verifying the confidentiality of a session key. The Alive attribute denotes the liveness of a role. It indicates that all agents participating in the protocol actively perform their roles until the end of communication. The Weakagree attribute ensures that when two agents believe that they have executed the protocol, they mutually agree on that fact. In other words, the communication counterpart must be the legitimate entity and not an attacker. The Nisynch attribute denotes non-injective synchronization. Non-injective synchronization verifies that everything occurs in execution exactly as intended by the protocol. The Niagree attribute refers to non-injective agreement on messages. It ensures that the messages exchanged within the protocol match exactly in their content.

The protocol [44] first allows the IoMT sensor and the medical server to authenticate each other. Then, it enables mutual authentication between the doctor and the medical server. We modeled the sensor–server and doctor–server communications as two separate files. In the sensor–server analysis, Alive and Weakagree claims for both entities returned “OK.” However, the Nisynch and Niagree claims failed. This indicates that the protocol does not guarantee correct message order or exact correspondence between transmitted and received messages. This result shows that the sensor–server communication requires stronger authentication mechanisms. In contrast, the doctor–server analysis showed that all Alive claims for both entities returned “OK.” These findings confirm the security of communication between the doctor and the medical server.

To evaluate the security of [45], we verified the Alive, Weakagree, Nisynch, and Niagree attributes of the participating entities. Participating entities include patients and doctors. Additionally, we analyzed whether the CID exchanged between them maintained confidentiality. Since IPFS functions solely as a medium for storage and transmission and does not perform any cryptographic operations, it was not defined as a separate role in the model. The lack of such measures creates a vulnerability that allows messages modified by a malicious patient to go undetected.

The analysis confirmed the confidentiality of the CID, as well as the Alive, Weakagree, Nisynch, and Niagree attributes for doctors and the Alive and Weakagree attributes for patients. However, the patient’s Nisynch and Niagree attributes failed to meet the security requirements, indicating vulnerabilities in synchronization and agreement.

They modeled the protocol [46] by combining the registration and authentication phases into a single file. As certain steps rely on public key encryption, they were represented using the function. The protocol does not establish a session key, so we did not test the SKR claim and instead examined only the confidentiality of the medical data . The analysis shows that Alive, Nisynch, Niagree, and Weakagree claims for the doctor, the Service Provider (SP), and the gateway all return “OK”. This outcome confirms their activities and mutual authentication.

Masud et al. [47] proposed a protocol in which each agent generates a PUF through the const declaration. The Scyther model includes the registration phase without omission. It also represents the registration and authentication processes within a single file. The gateway, sensor node, and doctor show “OK” for Alive, Nisynch, Niagree, and Weakagree claims. These results confirm liveness and mutual authentication among the entities. The SKR claim for the session keys also returns “OK,” verifying that the confidentiality of the session key remains intact. Therefore, the protocol meets essential security requirements.

In the modeling of the protocol [48], the registration phase operates over a secure channel. It is therefore simplified to highlight the essential information exchange. The Diffie–Hellman key exchange used in this process is modeled through a helper protocol. Claims such as Alive, Nisynch, Niagree, and Weakagree for both the gateway node and the user are all marked “OK”. This confirms liveness and mutual authentication between the entities. The SKR claim between the medical sensor node and the user is also marked “OK”. This result verifies that the confidentiality of the session key is preserved. No attacks were detected during the communication. These outcomes demonstrate that the protocol ensures secure transmission.

In the Scyther modeling of the protocol [49], we included only the user registration, login, and authentication with key-agreement phases. The preliminary phase defines a Trusted Authority (TA) responsible for distributing the required elements. For the user, Alive, Nisynch, Niagree, and Weakagree claims all return “OK.” These results confirm liveness and successful authentication. The SKR claim between the user and the cloud server also returns “OK,” ensuring user authentication and session key confidentiality from the server’s perspective. In contrast, the cloud server shows “Fail” for Alive, Nisynch, Niagree, and Weakagree claims. This result indicates that the protocol does not authenticate the server. However, because Scyther cannot accurately verify timestamps, cross-validation must be conducted with another tool, namely SVO as employed in this paper.

During the modeling of the [50], ambiguity arose in the computation involving the fog node’s private key . This issue was addressed by treating as equivalent to a nonce . In addition, we corrected several typing errors identified in the original text and reflected them in the Scyther code to ensure analytical accuracy. The verified properties included Alive, Weak Agreement, Nisynch, and Niagree for both the User (U) and the Fog Node (FN), along with the secrecy of the session key exchanged between them. The analysis revealed that the user’s Nisynch and Niagree properties, as well as the session key secrecy, failed to satisfy the security criteria. The fog node also failed to meet the Nisynch and Niagree properties, indicating vulnerabilities in synchronization and agreement assurance. This result reveals that the protocol does not provide server authentication. Given that Scyther cannot ensure accurate timestamp verification, cross-checking is required with an alternative method, in this case, the SVO, as utilized in this paper.

The proposed protocol [51] consists of message exchanges among the user, the gateway, and the sensor node. During the user-registration phase, we analyzed the use of the Diffie–Hellman key-exchange method and incorporated it into the modeling process by adding a supplementary protocol. We conducted the security verification by examining the Alive, Weakagree, Nisynch, and Niagree properties for each entity. We also verified the confidentiality of the session key exchanged among the entities. The analysis showed that all verification claims returned “OK”, which confirmed both the liveness of each entity and the satisfaction of mutual authentication. Furthermore, the results demonstrated the confidentiality of the session key, thereby proving that the proposed protocol ensures reliable security.

We modeled the registration phase of the protocol [53] by assuming it had already been completed. In this setting, the gateway transmitted all required elements together. The verification results indicate that the user satisfied all Alive, Nisynch, Niagree, and Weakagree claims. We also confirmed the confidentiality of both the session key and the gateway’s master key x. However, the gateway did not satisfy the AliveAlive and Weakagree claims, and the sensor device did not satisfy any of the Alive, Nisynch, Niagree, and Weakagree claims. These results indicate that the authentication of the gateway and the sensor device is ineffective during communication. The proposed protocol often relies on XOR functions. However, because Scyther is unable to process XOR operations, manual modeling becomes necessary; this can introduce unintended false positives. Thus, protocols containing XOR must be cross-validated with alternative verification tools.

The protocol [54] specified a single file that sequentially includes the registration and authentication steps. Analysis using Scyther revealed that the Alive, Nisynch, Niagree, and Weakagree claims for the Mobile Equipment (ME), Access Gateway (AG), and Medical Server (MS) all returned “OK.” This confirms that each participant’s activities were normal and that mutual authentication was successfully achieved.

5. Discussion

The analysis presented in Figure 2 shows that there is a trade-off relationship between computational cost efficiency and robust security among the proposed protocols. In general, protocols that satisfy many security requirements have higher computational costs. Other protocols with lower computational overhead have lower security. This relationship is very important in real environments, especially in resource-constrained environments and in environments where security and responsiveness are equally critical.

Table 7 briefly summarizes the formal verification results. This table indicates whether the authors of each paper conducted the verification and the results of our verification via SVO-Logic and Scyther. We observed that most protocols satisfied fundamental security requirements such as authentication, confidentiality, and integrity. However, many protocols are found to be inadequate in meeting the main security requirements, including key agreement, the consistency of communication objectives, and confidentiality assurance. Despite these limitations, the protocols presented in [44,48] demonstrated robustness in both verification approaches, indicating a comparatively higher level of security than the other protocols.

Table 7.

Security Verification Result.

Among the protocols reviewed in this paper, the scheme proposed by Miao et al. [48] stands out. This protocol shows a relaxation of the trade-off relationship between security and efficiency. The proposed scheme satisfies a wide range of security requirements. The proposed method maintains relatively low computational time compared to other protocols that achieve similar security levels. This shows that the protocol proposed by Miao et al. [48]. The protocol is suitable for environments such as IoMT systems that require both strong security and a lightweight protocol.

Miao et al. [48]’s protocol was formally verified using SVO Logic and Scyther. The analysis confirmed logical derivations of mutual authentication, session freshness, key agreement, and key confirmation. These results indicate that the protocol satisfies critical security properties while maintaining computational efficiency.

The verification results further emphasize the practical value of the protocol. It not only demonstrates mutual authentication, key agreement, and efficiency, but also shows potential applicability in real-world deployments. In particular, its strengths suggest that it may be well-suited for resource-constrained environments or scenarios requiring strong security guarantees. Nonetheless, moving from theoretical validation to practical adoption requires careful consideration of its limitations.

6. Conclusions

IoT technology has led to significant transformations in the medical sector. In particular, the growth of the elderly population and the increasing prevalence of chronic diseases have continuously heightened the demand for personalized medical services. To address these emerging challenges, the need for intelligent medical systems capable of supporting real-time patient monitoring and data-driven medical decision-making is becoming increasingly critical.

The IoMT is revolutionizing the provision of healthcare services across diverse environments by interconnecting MDs, wearable devices, and point-of-care diagnostic equipment. Furthermore, IoMT technologies are being integrated into hospital-management systems to facilitate the real-time monitoring of medical assets and facilities and to enable seamless sharing of health data between patients and healthcare providers. This integration enhances the delivery of various medical services, including preventive care, management of chronic disease, and emergency response.

Within IoMT environments, data transmission serves as a fundamental determinant of overall system efficiency and reliability. Health data collected by sensors and medical devices must meet stringent requirements concerning security, reliability, latency, and energy efficiency. Given the sensitive nature of medical information, any compromise in data integrity or transmission reliability could pose direct threats to patient safety. Consequently, the development of secure and efficient data-transmission methods is of paramount importance.

In practice, the selection of an authentication protocol must balance the importance of security requirements with the available computational resources. Lightweight schemes may be preferable for resource-constrained IoMT nodes, whereas critical systems require protocols with stronger security guarantees despite higher costs.

In this context, this paper comprehensively analyzes recently proposed authentication protocols in terms of security requirements, computational costs, and formal verification results to explore protocols suitable for the IoMT environment. The results highlighted the protocol proposed by Miao et al. [48], confirming the importance of balancing environmental characteristics and security in future IoMT protocol development.

This evaluation has several limitations. First, it assumed that all security requirements are equivalent and did not consider that their importance may vary depending on the application scenario. Second, the computational time was collected under general conditions, and actual performance may differ across hardware platforms and operational environments.

In future research, we plan to design an authentication protocol that optimizes the trade-off between security and computational efficiency by systematically categorizing diverse use cases and prioritizing security requirements according to their relative importance in each application environment.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://github.com/lsb0207/IoMT_SupplementFile (accessed on 2 October 2025).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.L. (Seungbin Lee) and J.K.; methodology, J.K.; validation, S.L. (Seungbin Lee), K.A.K. and J.K.; formal analysis, S.L. (Soowang Lee) and J.K.; investigation, S.L. (Seungbin Lee) and S.L. (Soowang Lee); data curation, K.A.K. and J.K.; writing—original draft preparation, S.L. (Seungbin Lee) and J.K.; writing—review and editing, S.L. (Seungbin Lee) and J.K.; visualization, S.L. (Seungbin Lee); supervision, J.K.; project administration, J.K.; funding acquisition, J.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) [grant number RS-2023-00210767].

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 3ECAP | Three-Factor Efficient and Cost-Aware Authentication Protocol |

| 3-Factor | Three-Factor Authentication |

| 4G/5G | 4th Generation/5th Generation |

| AES | Advanced Encryption Standard |

| AVISPA | Automated Validation of Internet Security Protocols and Applications |

| BAKMP | Blockchain-based Authentication and Key Management Protocol |

| BAN-Logic | Burrows–Abadi–Needham Logic |

| BCI | Brain–Computer Interface |

| BLE | Bluetooth Low Energy |

| BYOD | Bring Your Own Device |

| CE | Consumer Electronics |

| CGM | Continuous Glucose Monitoring |

| CoAP | Constrained Application Protocol |

| CRT | Chinese Remainder Theorem |

| CVE | Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures |

| CVP | Closest Vector Problem |

| DBS | Deep Brain Stimulator |

| DH | Diffie–Hellman |

| ECC | Elliptic Curve Cryptography |

| ECG | Electrocardiogram |

| EHRs | Electronic Health Records |

| ESL | Ephemeral Secret Leakage |

| HL7 | Health Level Seven |

| ICDs | Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillators |

| IMD | Implantable Medical Device |

| IoMT | Internet of Medical Things |

| IoMT-SAF | Internet of Medical Things – Security Assessment Framework |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| IoWD | Internet of Wearable Devices |

| L2FAK | Lightweight Two-Factor Authentication Framework |

| LBC | Lightweight Lattice-Based Cryptography |

| LTE | Long Term Evolution |

| LVADs | Left Ventricular Assist Devices |

| LWE | Learning with Errors |

| M2M | Machine-to-Machine |

| MASK | Mutual Authentication and Secret Key |

| MDs | Medical Devices |

| MITM | Man-In-The-Middle (Attack) |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| MQTT | Message Queuing Telemetry Transport |

| NFC | Near Field Communication |

| NFT | Non-Fungible Token |

| ProVerif | Protocol Verification Tool |

| PSLA2P | Provably Secured Lightweight Authenticated Key Agreement Protocol |

| PUF | Physically Unclonable Function |

| QoS | Quality of Service |

| RFID | Radio-Frequency Identification |

| RSA | Rivest–Shamir–Adleman (Public Key Cryptosystem) |

| SCS | Spinal Cord Stimulator |

| SDN | Software Defined Networking |

| Slither | Solidity Static Analysis Tool |

| S-IoMT | Smart Internet of Medical Things |

| SpO2 | Peripheral Capillary Oxygen Saturation |

| SVP | Shortest Vector Problem |

| TA | Trusted Authority |

| VNS | Vagus Nerve Stimulator |

| Wi-Fi | Wireless Fidelity |

| XAI | Explainable Artificial Intelligence |

| XOR | Exclusive OR |

Appendix A. Formal Verification Result for Abdussami et al. [44]

Annotation

Comprehension

Interpretation

Assumption

Goal

| Derivation | |

Appendix B. Formal Verification Result for Qiu et al. [45]

Annotation

Comprehension

Interpretation

Assumption

Goal

| Derivation | |

Appendix C. Formal Verification Result for Lo et al. [46]

Annotation

Comprehension

Interpretation

Assumption

Goal

| Derivation | |

Appendix D. Formal Verification Result for Masud et al. [47]

Annotation

Comprehension

Interpretation

Assumption

Goal

| Derivation | |

Appendix E. Formal Verification Result for Miao et al. [48]

Annotation

Comprehension

Interpretation

Assumption

Goal

| Derivation | |

Appendix F. Formal Verification Result for Garg et al. [49]

Annotation

Comprehension

Interpretation

Assumption

Goal

| Derivation | |

Appendix G. Formal Verification Result for Pradhan et al. [50]

Annotation

Comprehension

Interpretation

Assumption

Goal

| Derivation | |

Appendix H. Formal Verification Result for Gautam et al. [51]

Annotation

Comprehension

Interpretation

Assumption

Goal

| Derivation | |

Appendix I. Formal Verification Result for Su et al. [53]

Annotation

Comprehension

Interpretation

Assumption

Goal

| Derivation | |

Appendix J. Formal Verification Result for Deebak et al. [54]

Annotation

Comprehension

Interpretation

Assumption

Goal

| Derivation | |

References

- Jain, S.; Nehra, M.; Kumar, R.; Dilbaghi, N.; Hu, T.; Kumar, S.; Kaushik, A.; Li, C.z. Internet of medical things (IoMT)-integrated biosensors for point-of-care testing of infectious diseases. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2021, 179, 113074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xenofontos, C.; Zografopoulos, I.; Konstantinou, C.; Jolfaei, A.; Khan, M.K.; Choo, K.K.R. Consumer, commercial, and industrial iot (in) security: Attack taxonomy and case studies. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 9, 199–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejía-Granda, C.M.; Fernández-Alemán, J.L.; Carrillo-de Gea, J.M.; García-Berná, J.A. Security vulnerabilities in healthcare: An analysis of medical devices and software. Med Biol. Eng. Comput. 2024, 62, 257–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, P.; Huang, D.; Wu, D.; He, H.; Wei, Y.; Cui, Y.; Wang, R.; Peng, L. A survey of internet of medical things: Technology, application and future directions. Digit. Commun. Netw. 2024; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivagangatharani, B.; Rabiya, M.S. Enabling Technologies in IoMT Smart Healthcare: A Survey. In Proceedings of the 2024 10th International Conference on Communication and Signal Processing (ICCSP), Melmaruvathur, India, 12–14 April 2024; pp. 665–670. [Google Scholar]

- Gkonis, P.; Giannopoulos, A.; Trakadas, P.; Masip-Bruin, X.; D’Andria, F. A survey on IoT-edge-cloud continuum systems: Status, challenges, use cases, and open issues. Future Internet 2023, 15, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osama, M.; Ateya, A.A.; Sayed, M.S.; Hammad, M.; Pławiak, P.; Abd El-Latif, A.A.; Elsayed, R.A. Internet of medical things and healthcare 4.0: Trends, requirements, challenges, and research directions. Sensors 2023, 23, 7435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, T.; Khan, A.H.; Kanwal, K.; Daud, A.; Irfan, M.; Bukhari, A.; Alharbey, R. IoMT-Based Healthcare Systems: A Review. Comput. Syst. Sci. Eng. 2024, 48, 871–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sindhuja, R. A survey of Internet of Medical Things (IoMT) applications, architectures and challenges in smart healthcare systems. In Proceedings of the 1st ITM Web of Conferences, Coimbatore, India, 23–24 June 2023; EDP Sciences: Les Ulis, France, 2023; Volume 56, p. 05013. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, T.; Ji, S.; Jin, W.; Yang, Q.; Luo, Q.; Ren, T.L. Biocompatible and long-term monitoring strategies of wearable, ingestible and implantable biosensors: Reform the next generation healthcare. Sensors 2023, 23, 2991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Liu, X.; Peng, S.; Jiang, X.; Xu, K.; Chen, C.; Wang, Z.; Dai, C.; Chen, W. A review of wearable and unobtrusive sensing technologies for chronic disease management. Comput. Biol. Med. 2021, 129, 104163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özkartal, T.; Demarchi, A.; Caputo, M.L.; Baldi, E.; Conte, G.; Auricchio, A. Perioperative management of patients with cardiac implantable electronic devices and utility of magnet application. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varshney, A.S.; DeFilippis, E.M.; Cowger, J.A.; Netuka, I.; Pinney, S.P.; Givertz, M.M. Trends and outcomes of left ventricular assist device therapy: JACC focus seminar. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2022, 79, 1092–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.C.; Liao, Y.S.; Yeh, W.H.; Liang, S.F.; Shaw, F.Z. Directions of deep brain stimulation for epilepsy and Parkinson’s disease. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 680938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, C.M.; Latif, U.; Sack, A.; Govindan, S.; Sanderson, M.; Vu, D.T.; Smith, G.; Sayed, D.; Khan, T. Advances in spinal cord stimulation. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Wu, B.; Lin, R.; Cheng, Y.; Huang, J.; Chen, Y.; Bai, J. Vagus nerve stimulation: A physical therapy with promising potential for central nervous system disorders. Front. Neurol. 2024, 15, 1516242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Taj, I.; Farhan, K.; Tariq, B.; Raufi, N. Revolutionizing diabetes care: New insulin pump and algorithm-based software for automatic insulin delivery. IJS Glob. Health 2024, 7, e0431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaepelynck, P.; Renard, E.; Jeandidier, N.; Hanaire, H.; Fermon, C.; Rudoni, S.; Catargi, B.; Riveline, J.P.; Guerci, B.; Millot, L.; et al. A recent survey confirms the efficacy and the safety of implanted insulin pumps during long-term use in poorly controlled type 1 diabetes patients. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2011, 13, 657–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchoe, H.J.; Shin, H.W.; Shin, C.M.; Lim, C.M. Assisted breathing with a diaphragm pacing system: A systematic review. Yonsei Med. J. 2020, 61, 1024. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, A.S.; Pingree, G.; Chafin, A.; Fitzpatrick IV, T.H.; Nord, R.S. Respiratory sensing lead malfunction in upper airway stimulation: A single institution report. Laryngoscope 2024, 134, 1479–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Ahn, J.; Rhee, J.; Ahn, S. Application of wireless power transfer technology to implantable medical devices. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE MTT-S International Microwave Biomedical Conference (IMBioC), Suzhou, China, 16–18 May 2022; pp. 299–301. [Google Scholar]

- Catuogno, L.; Galdi, C. Implantable Medical Device Security. Cryptography 2024, 8, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, C.; Bartschke, A.; Fürstenau, D.; Schaaf, T.; Salgado-Baez, E. The Value of Smartwatches in the Health Care Sector for Monitoring, Nudging, and Predicting: Viewpoint on 25 Years of Research. J. Med. Internet Res. 2024, 26, e58936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Guzman, M.C.; Shang, T.; Zhang, J.Y.; Jornsay, D.; Klonoff, D.C. Continuous glucose monitoring in the hospital. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 36, 240–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zhang, J.; Li, C. Design of intelligent wearable equipment based on real-time dynamic ECG-monitoring system. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2023, 15, 6413. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, S.H.D.; Deen, G.R.; Bates, J.S.; Maiti, C.; Lam, C.Y.K.; Pachauri, A.; AlAnsari, R.; Bělskỳ, P.; Yoon, J.; Dodda, J.M. Smart skin-adhesive patches: From design to biomedical applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2213560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, J.; Huang, Z.; Huang, D.; Yu, H.; Li, Z. Recent progress in wearable brain–computer interface (BCI) devices based on electroencephalogram (EEG) for medical applications: A review. Health Data Sci. 2023, 3, 0096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Peng, Q.; Zhu, X.; Deng, T.; Cao, R.; Liu, W. Ensuring Trustworthy and Secure IoT: Fundamentals, Threats, Solutions, and Future Hotspots. Comput. Netw. 2025, 263, 111218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, M.; Pascale, F.; Santaniello, D. Internet of things: A general overview between architectures, protocols and applications. Information 2021, 12, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrabet, H.; Belguith, S.; Alhomoud, A.; Jemai, A. A survey of IoT security based on a layered architecture of sensing and data analysis. Sensors 2020, 20, 3625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calderón, D.; Folgado, F.J.; González, I.; Calderón, A.J. Implementation and experimental application of industrial IoT architecture using automation and IoT Hardware/Software. Sensors 2024, 24, 8074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koulouras, G.; Katsoulis, S.; Zantalis, F. Evolution of Bluetooth Technology: BLE in the IoT Ecosystem. Sensors 2025, 25, 996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zohourian, A.; Dadkhah, S.; Neto, E.C.P.; Mahdikhani, H.; Danso, P.K.; Molyneaux, H.; Ghorbani, A.A. IoT Zigbee device security: A comprehensive review. Internet Things 2023, 22, 100791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, D.H.; Duraisamy, K.; Armghan, A.; Alsharari, M.; Aliqab, K.; Sorathiya, V.; Das, S.; Rashid, N. 5G technology in healthcare and wearable devices: A review. Sensors 2023, 23, 2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshammari, H.H. The internet of things healthcare monitoring system based on MQTT protocol. Alex. Eng. J. 2023, 69, 275–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bormann, C.; Castellani, A.P.; Shelby, Z. Coap: An application protocol for billions of tiny internet nodes. IEEE Internet Comput. 2012, 16, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saripalle, R.; Runyan, C.; Russell, M. Using HL7 FHIR to achieve interoperability in patient health record. J. Biomed. Inform. 2019, 94, 103188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askar, N.A.; Habbal, A.; Mohammed, A.H.; Sajat, M.S.; Yusupov, Z.; Kodirov, D. Architecture, protocols, and applications of the internet of medical things (IoMT). J. Commun. 2022, 17, 900–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razdan, S.; Sharma, S. Internet of medical things (IoMT): Overview, emerging technologies, and case studies. IETE Tech. Rev. 2022, 39, 775–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsubaei, F.; Abuhussein, A.; Shandilya, V.; Shiva, S. IoMT-SAF: Internet of medical things security assessment framework. Internet Things 2019, 8, 100123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghubaish, A.; Salman, T.; Zolanvari, M.; Unal, D.; Al-Ali, A.; Jain, R. Recent advances in the internet-of-medical-things (IoMT) systems security. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 8, 8707–8718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatzivasilis, G.; Soultatos, O.; Ioannidis, S.; Verikoukis, C.; Demetriou, G.; Tsatsoulis, C. Review of security and privacy for the Internet of Medical Things (IoMT). In Proceedings of the 2019 15th International Conference on Distributed Computing in Sensor Systems (DCOSS), Santorini, Greece, 29–31 May 2019; pp. 457–464. [Google Scholar]

- Bhushan, B.; Kumar, A.; Agarwal, A.K.; Kumar, A.; Bhattacharya, P.; Kumar, A. Towards a secure and sustainable internet of medical things (iomt): Requirements, design challenges, security techniques, and future trends. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdussami, M.; Amin, R.; Vollala, S. Provably secured lightweight authenticated key agreement protocol for modern health industry. Ad Hoc Netw. 2023, 141, 103094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S.; Li, J.; Di, X.; Li, X.; Wu, Y.; Ibrahim, M. Lightweight mutual authentication scheme based on blockchain for the Internet of Medical Things. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 12, 8848–8861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, C.K.M.; Tan, S.F.; Chung, G.C. Enhanced Authentication Protocol for Securing Internet of Medical Things with Lightweight Post-Quantum Cryptography. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Engineering and Technology (IICAIET), Kota Kinabalu, Malaysia, 26–28 August 2024; pp. 625–630. [Google Scholar]

- Masud, M.; Gaba, G.S.; Alqahtani, S.; Muhammad, G.; Gupta, B.B.; Kumar, P.; Ghoneim, A. A lightweight and robust secure key establishment protocol for internet of medical things in COVID-19 patients care. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 8, 15694–15703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, J.; Wang, Z.; Wu, Z.; Ning, X.; Tiwari, P. A blockchain-enabled privacy-preserving authentication management protocol for Internet of Medical Things. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 237, 121329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, N.; Wazid, M.; Das, A.K.; Singh, D.P.; Rodrigues, J.J.; Park, Y. BAKMP-IoMT: Design of blockchain enabled authenticated key management protocol for internet of medical things deployment. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 95956–95977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, M.; Mohanty, S. A blockchain-assisted multifactor authentication protocol for enhancing IoMT security. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 39323–39332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, D.; Thakur, G.; Obaidat, M.S.; Hsiao, K.F.; Kumar, P. Security Analysis and Improvement of Authenticated Key Agreement Protocol for Remote Patient Monitoring IoMT. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Communications, Computing, Cybersecurity, and Informatics (CCCI), Beijing, China, 16–18 October 2024; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.M.; Liu, S.; Li, X.; Islam, S.H.; Das, A.K. A provably-secure authenticated key agreement protocol for remote patient monitoring IoMT. J. Syst. Archit. 2023, 136, 102831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Xu, Y. Secure and Lightweight Cluster-Based User Authentication Protocol for IoMT Deployment. Sensors 2024, 24, 7119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deebak, B.; Hwang, S.O. Federated learning-based lightweight two-factor authentication framework with privacy preservation for mobile sink in the social IOMT. Electronics 2023, 12, 1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO/IEC 29128-1:2023; Information Security, Cybersecurity and Privacy Protection—Verification of Cryptographic Protocols—Part 1: Framework. International standard; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

- Syverson, P.F.; Van Oorschot, P.C. On unifying some cryptographic protocol logics. In Proceedings of the 1994 IEEE Computer Society Symposium on Research in Security and Privacy, Oakland, CA, USA, 16–18 May 1994; pp. 14–28. [Google Scholar]

- Cremers, C.J. The scyther tool: Verification, falsification, and analysis of security protocols: Tool paper. In Computer Aided Verification, Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Computer Aided Verification, Princeton, NJ, USA, 7–14 July 2008; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 414–418. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).