Abstract

Post-oncologic skin is subject to multiple structural and functional impairments following chemotherapy and radiotherapy, including delayed epidermal turnover, compromised barrier integrity, and mitochondrial dysfunction. These changes can lead to persistent dryness, heightened reactivity, impaired regeneration, and reduced patient quality of life. In this context, topical dermocosmetic strategies are essential not only for improving comfort and hydration, but also for supporting key cellular pathways involved in mitochondrial protection and oxidative stress reduction. Despite the promise of natural antioxidant actives, their cutaneous efficacy is often limited by poor stability, low bioavailability, and insufficient penetration of the stratum corneum. The use of nanocarriers promotes deeper skin penetration, protects oxidation-prone antioxidant compounds, and enables a controlled and prolonged release profile. This review summarizes the current evidence (2020–2025) on skin delivery systems designed to enhance the efficacy, stability, and skin penetration of antioxidants. Knowledge gaps and future directions are outlined, highlighting how rationally engineered delivery systems for mitochondria-targeted actives could contribute to safer, more effective strategies for post-oncologic skin regeneration.

1. Introduction

Chemotherapy and radiotherapy, as cornerstone modalities in cancer therapy, are frequently accompanied by cutaneous adverse effects. The mechanism of chemotherapy involves targeting and destroying rapidly dividing cells—including healthy cells of the skin, hair follicles, and nail matrix [1,2]. As a result, therapy may lead to adverse reactions such as alopecia, rashes, hypersensitivity, or hyperpigmentation. These treatments intensify oxidative stress and reduce mitochondrial activity, resulting in damage to the skin and its appendages. These dermatologic toxicities can markedly affect patient’s quality of life and may lead to dose reductions or discontinuation of anticancer therapy [1,3,4]. In addition to serious complications such as hand-foot syndrome, alopecia, or mucosal disorders, skin following cancer treatment often exhibits increased reactivity and decreased tolerance to topical products. This may manifest as a tendency toward redness, telangiectasia, post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation, as well as decreased elasticity, dryness, and a sallow tone, resulting from chronic inflammation [2,5,6]. In addition to the physiological burden, visible skin alterations may have a profound psychosocial impact on patients during and after cancer therapy. Cutaneous changes such as erythema, hyperpigmentation, persistent dryness, and loss of skin elasticity are often perceived as stigmatizing, contributing to decreased self-esteem, social withdrawal, and reduced overall well-being. Importantly, these manifestations may persist long after the completion of oncologic treatment, leaving the skin in a state of prolonged sensitivity and impaired regenerative capacity [5].

At the cellular level, many of dermatologic manifestations are strongly associated with elevated oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction. Mitochondria are central to maintaining skin homeostasis, regulating energy metabolism and cellular repair. When their function is impaired, the skin’s regenerative potential declines significantly, resulting in persistent inflammation and delayed barrier recovery [7]. For the purpose of this review, the term “mitoprotective” is used to describe indirect protective effects on mitochondrial integrity, mediated primarily through antioxidant and free radical-scavenging activities, rather than through direct modulation or restoration of mitochondrial function.

Due to the persistent impairment of epidermal barrier function and delayed tissue regeneration observed after oncologic treatment, supportive dermocosmetic care is essential for restoring skin comfort, hydration, and structure [2]. However, the topical performance of numerous bioactive compounds with antioxidant or mitochondria-protective activity is often constrained not only by their limited skin penetration and intrinsic instability, but also by their pronounced sensitivity to external conditions. Many of these substances display poor solubility and degradability under variations in pH, temperature, or environmental stress, which further diminishes their functional efficacy [8]. This has led to increasing interest in delivery systems, including lipid-based nanocarriers, designed to enhance active ingredient protection, controlled release, and skin compatibility [9,10]. Therefore, the aim of this review is to summarize mitochondria-protective, natural-based cosmetic actives relevant to post-oncologic skin regeneration, and to discuss delivery systems that can improve their topical performance.

2. Post-Oncologic Skin: Structural and Functional Characteristics

Although most publications describe the skin as the largest organ of the human body and as the primary protective barrier, Sontheimer presents a contrasting view, noting that the skin is smaller in both mass and functional surface area than the musculoskeletal system and certain internal organs, such as the lungs and gastrointestinal tract [11].

It is composed of three main layers—the epidermis, dermis, and subcutaneous tissue—each characterized by specific structural features and functional roles that collectively ensure barrier integrity, sensory perception, thermoregulation, and the maintenance of cutaneous homeostasis [12,13,14,15]. The epidermis, of ectodermal origin, undergoes continuous self-renewal and is organized into several strata, including the basal, spinous, granular, and stratum corneum layers. Its predominant cell type, the keratinocyte, originates in the basal layer, where cells actively proliferate and gradually differentiate as they migrate toward the skin surface. The complete turnover of the epidermis typically occurs within approximately 4 to 6 weeks [16]. At the terminal stage of differentiation, keratinocytes form the stratum corneum (SC), a layer of flattened, non-viable corneocytes. The stratum corneum serves as the first line of defense, where corneocytes are embedded in a lamellar lipid matrix composed primarily of ceramides, cholesterol, and free fatty acids, effectively preventing transepidermal water loss (TEWL) and external irritation [16,17,18,19]. Skin cells act as a protective shield against external stressors such as UV radiation, infections, and pollutants, which induce the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that contribute to premature skin aging and the development of various dermatoses [10].

Cancer therapies, particularly chemotherapy and radiotherapy, can profoundly disrupt the structural and functional organization of the epidermis. Because keratinocytes in the basal layer undergo rapid and continuous proliferation, they are particularly vulnerable to cytotoxic agents that target dividing cells [16,20,21]. As a result, epidermal turnover becomes delayed, the stratum corneum may form incompletely, and the lamellar lipid matrix becomes quantitatively and qualitatively altered, especially in relation to ceramide composition [20,22]. In parallel, fibroblast function within the dermis may be affected, leading to reduced extracellular matrix synthesis and diminished skin elasticity over time. The combined impairment of epidermal barrier integrity and dermal support contributes to clinical manifestations commonly observed in post-oncologic skin, including dryness, erythema, hypersensitivity and delayed healing [23,24,25]. To better illustrate the multi-layered impact of oncologic treatments on cutaneous structure and function, Table 1 summarizes the principal alterations observed across the epidermis, dermis, and subcutaneous tissue. The changes are presented in relation to the underlying molecular mechanisms and their clinical manifestations, highlighting how cytotoxic injury, oxidative stress, and chronic inflammation collectively contribute to the persistent fragility, impaired regeneration, and heightened sensitivity characteristic of post-oncologic skin [14,25,26,27,28].

Table 1.

Structural and functional alterations in post-oncologic skin across different skin layers, associated biological mechanisms, and clinical manifestations.

These layered structural alterations reflect not only localized tissue injury but also more profound disturbances in the cellular mechanisms that maintain cutaneous homeostasis. Although the epidermal barrier, dermal extracellular matrix, and subcutaneous tissue volume are visibly affected, these changes are rooted in disruptions of cellular metabolism—particularly mitochondrial function. Mitochondria are dynamic double-membrane organelles present in virtually all eukaryotic cells, possessing their own mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) and playing central roles beyond mere energy production [30]. Their function relies on oxidative phosphorylation, where electrons derived from substrates such as glucose and fatty acids traverse the electron transport chain, generating a proton gradient across the inner mitochondrial membrane that drives adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production. Concurrently, the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle oxidizes acetyl-CoA to supply electrons to the chain, while mitochondria also support fatty acid oxidation, amino acid catabolism, and contribute to the urea cycle [31]. In the skin—a tissue with high turnover and metabolic demand—mitochondrial activity is crucial. Skin is composed of over 20 distinct cell types, each reliant on mitochondrial homeostasis for functions such as cell signaling, wound healing, hair growth, barrier maintenance and microbial defense [7,31]. Any deviation in mitochondrial function may, therefore, compromise cutaneous homeostasis, accelerating aging processes and increasing susceptibility to pathology. When mitochondrial balance is disturbed, cellular differentiation, matrix formation, redox stability, and tissue regeneration become impaired, contributing to progressive functional decline in the skin [7].

Radiotherapy is known to induce the production of ROS, resulting in oxidative injury to lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids in skin cells [29]. In acute radiation-induced dermatitis, mitochondrial dysfunction develops through several interconnected processes: destabilization of mitochondrial membrane potential and calcium imbalance, increased oxidative stress with suppression of antioxidant defenses such as superoxide dismutase and catalase, and reduced ATP synthesis that limits dermal repair. These mechanisms reinforce one another, whereby mitochondrial injury heightens oxidative stress and oxidative stress further impairs mitochondrial function. These alterations slow epidermal turnover and contribute to delayed healing [32]. Chemotherapeutic agents can also disturb redox equilibrium in cutaneous tissues. Drugs such as anthracyclines and alkylating agents increase intracellular ROS, promoting apoptosis particularly within highly active cells such as hair follicle matrix keratinocytes. In the hair follicle, the oxidative stress response is normally regulated by nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), which limits lipid peroxidation and prevents premature transition into the catagen phase. Dysregulation of this mechanism during chemotherapy contributes to hair loss and barrier fragility [33]. The ability to neutralize ROS may support not only the modulation of wound pH but also the attenuation of inflammatory responses by disrupting both cellular and humoral pathways. Consequently, antioxidant-based skin care has attracted significant interest for its multifaceted roles—not only in enhancing skin condition by mitigating oxidative stress and inflammation but also in providing antimicrobial protection [34].

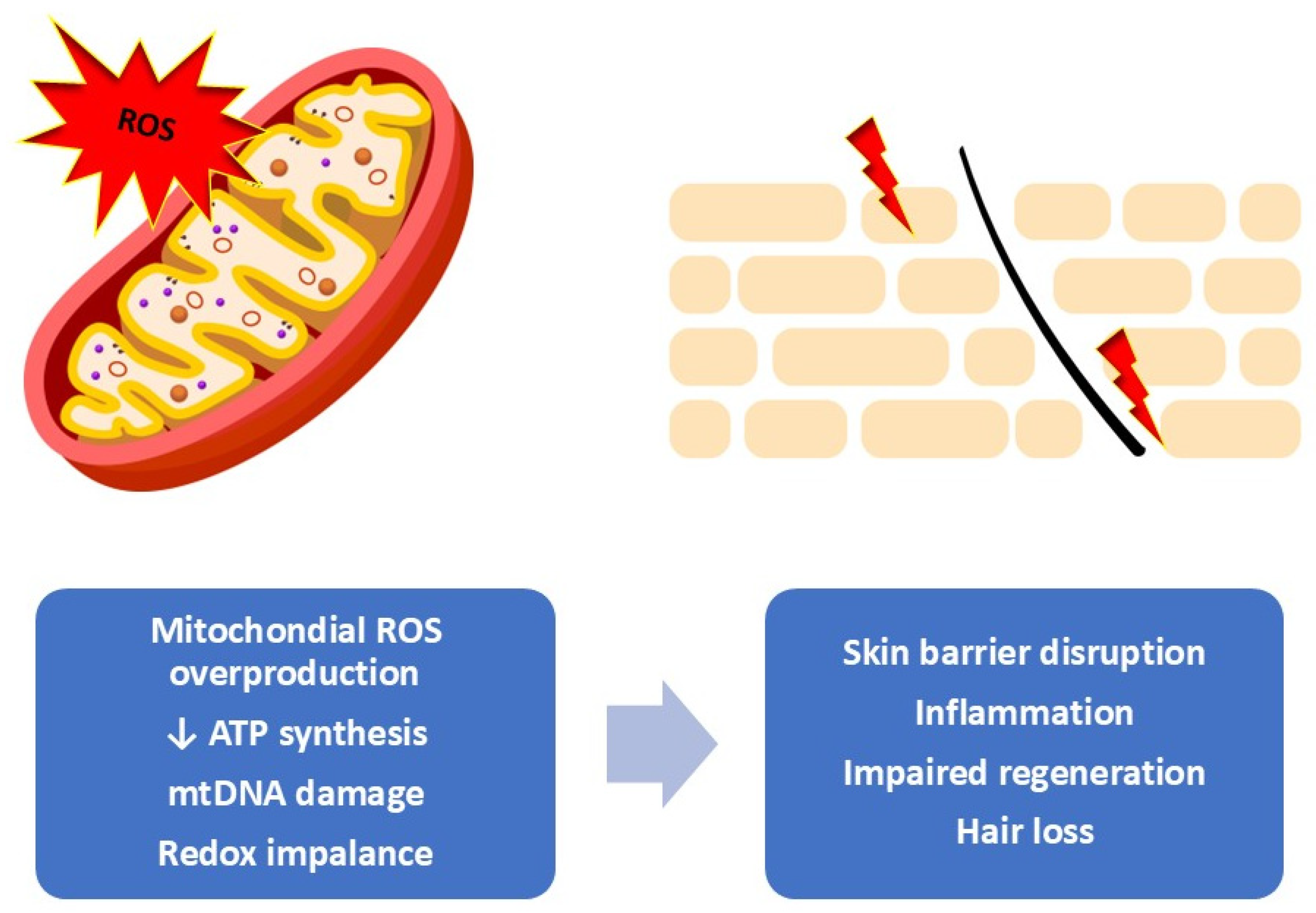

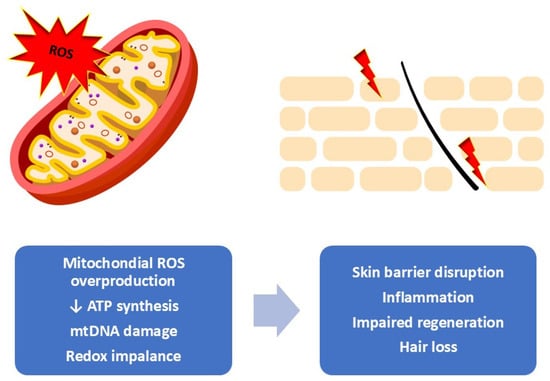

Cutaneous adverse effects associated with oncologic therapies can emerge at various stages—during active treatment, shortly after, or even months and years later, particularly in the context of radiotherapy or immunotherapy. These manifestations can substantially affect patient’s quality of life and influence how they experience and interpret their illness. Consequently, there is a growing agreement that structured skin care guidance should be provided throughout the entire stage of treatment. The use of supportive dermocosmetic or cosmeceutical strategies plays a critical role in reducing the severity of skin reactions and helping to maintain the integrity and comfort of the skin during and after cancer treatment [5]. Figure 1 shows the relationship between mitochondrial oxidative stress and the visible cutaneous alterations observed during and after oncologic therapies.

Figure 1.

Mitochondrial oxidative stress as a driver of skin dysfunction. Overproduction of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species leads to redox imbalance, reduced ATP synthesis, and mtDNA damage, resulting in impaired cellular metabolism and mitochondrial integrity. These changes contribute to barrier disruption, inflammation, reduced regenerative capacity, and hair loss at the tissue level [own work].

Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Protective Mechanisms in Skin

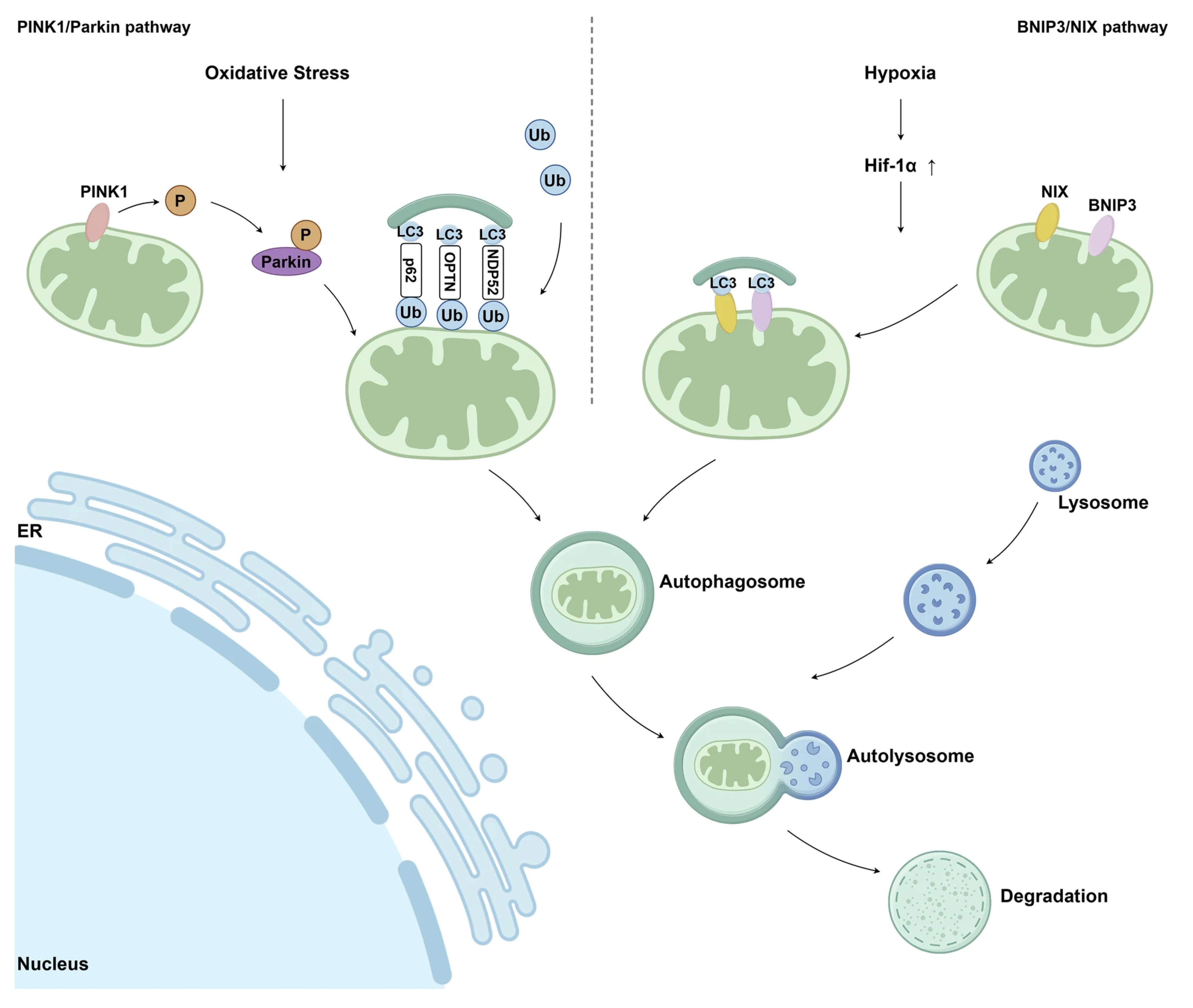

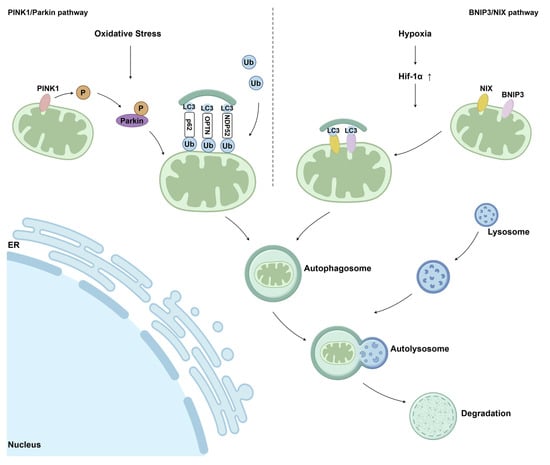

Accumulation of mtDNA (mitochondrial DNA) mutations and deletions progressively compromises mitochondrial bioenergetic capacity by impairing the efficiency of the electron transport chain (ETC), which in turn further amplifies mtROS (mitochondrial ROS) production, creating a self-perpetuating cycle of oxidative damage. Beyond bioenergetic failure, UVA-induced mitochondrial dysfunction promotes the release of pro-apoptotic factors, such as cytochrome c, thereby activating caspase-dependent apoptotic pathways in skin cells [35]. Mitochondrial dysfunction in post-oncologic skin extends beyond generalized oxidative stress and reflects a complex failure of mitochondrial quality control and repair mechanisms. In skin cells, the progressive accumulation of mitochondrial damage results from an imbalance between stress-induced injury and the efficiency of endogenous pathways responsible for maintaining mitochondrial integrity, bioenergetic competence, and cellular homeostasis [36]. At the molecular level, mitochondrial impairment is closely associated with dysregulation of mitochondrial dynamics, particularly the balance between fission and fusion processes [37]. Stress-mediated activation of dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1) promotes excessive mitochondrial fission, leading to mitochondrial fragmentation, reduced oxidative phosphorylation efficiency (OXPHOS), and increased susceptibility to apoptosis or cellular senescence. Concurrently, impaired fusion, regulated by mitofusins (MFN1/2) and optic atrophy protein 1 (OPA1), limits functional complementation between mitochondria, thereby accelerating bioenergetic decline in stressed epidermal and dermal cells [38]. To counteract mitochondrial damage, skin cells activate adaptive repair pathways centered on mitochondrial biogenesis and selective elimination of dysfunctional organelles. Mitochondrial biogenesis is primarily regulated by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha (PGC-1α), which coordinates the transcription of nuclear-encoded mitochondrial genes and supports the generation of new, functionally competent mitochondria [36,37]. Under conditions of chronic oxidative stress and inflammation, however, PGC-1α (Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alph) signaling may be attenuated, resulting in insufficient mitochondrial renewal and sustained cellular energy deficits [30]. An additional layer of mitochondrial quality control is provided by mitophagy, a selective autophagic process responsible for the removal of damaged mitochondria and the prevention of excessive reactive oxygen species accumulation and pro-inflammatory signaling [39]. UVA (ultraviolet A) exposure has been reported to interfere with this quality control mechanism, resulting in the persistence of dysfunctional organelles. Impaired mitophagy contributes to the accumulation of senescent keratinocytes and fibroblasts over time, which is closely associated with characteristic features of photoaged skin, including wrinkle formation, loss of elasticity, and pigmentary alterations [35]. Activation of the PINK1/Parkin pathway is critical for initiating mitophagy in response to mitochondrial membrane depolarization. Impairment of this pathway leads to the persistence of dysfunctional mitochondria, contributing to cellular senescence and chronic low-grade inflammation, processes commonly associated with aging and damaged skin. In addition to the PINK1/Parkin-dependent mechanism, mitophagy can also be initiated through receptor-mediated pathways involving BCL2/adenovirus E1B 19 kDa-interacting protein 3 (BNIP3) and its homolog NIX (BNIP3L). This pathway is activated predominantly under hypoxic or metabolic stress conditions and enables the direct recruitment of autophagic machinery to damaged mitochondria [40]. Mitophagy-based mitochondrial quality control mechanisms linking mitochondrial damage to skin dysfunction are summarized schematically in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Schematic illustration of the main mitophagy pathways involved in mitochondrial quality control. The PINK1/Parkin-dependent pathway and the BNIP3/NIX-mediated pathway regulate the selective removal of damaged mitochondria via autophagic degradation. Ub—ubiquitin; P—phosphorylation; LC3—microtubule-associated protein light chain 3; ER—endoplasmic reticulum [40] (Springer Nature open access under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License).

3. Dermocosmetics for Post-Oncologic Skin Care

After the completion of oncologic treatment, adequate support of cutaneous repair processes becomes very important to restoring the integrity and comfort of the skin and its appendages. Skin care intended for patients affected by treatment-induced dermatologic toxicities must rely on evidence-based, well-tolerated cosmetic ingredients characterized by a high safety profile, minimal irritancy, and proven efficacy [5,14,41]. Because xerosis is one of the most frequently reported concerns among post-oncologic patients, formulations should prioritize hydration, softening, and gentle cleansing. Cleansing products are recommended to have a skin-physiological pH, and bathing routines should avoid long and hot exposure, which may further compromise the epidermal barrier [2]. To minimize irritation, dermocosmetic formulations should incorporate mild, non-ionic surfactants, such as alkylpolyglucosides, which provide effective cleansing with reduced barrier disruption [2,16]. Urea is a widely used humectant, but in cases of severe radiation-induced dermatitis, its use may be contraindicated due to its keratolytic potential. Topical application of hyaluronic acid has demonstrated therapeutic benefit by enhancing hydration and supporting the regeneration process [2,42]. Soothing agents—including panthenol, glycerin, squalane, allantoin, propanediol, thermal water, and niacinamide—are also advantageous due to their barrier-strengthening and irritation-reducing properties. As a precursor of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+), niacinamide supports NAD+-dependent energy metabolism and redox balance in cells. These functions are essential for maintaining cellular resilience under oxidative and inflammatory stress. Evidence indicates that niacinamide contributes to DNA repair processes and mitigates oxidative damage, mechanisms that underpin its widespread application in dermo-cosmetic formulations designed to support skin regeneration and recovery in aging and photodamaged skin [37,43]. Improving the lipid organization of the stratum corneum is a central objective of post-oncologic skin care; therefore, emollients such as high-quality botanical oils and plant butters are frequently recommended [2,16]. Oils rich in bioactive compounds—such as rosehip or borage oils—provide essential fatty acids and natural antioxidants that support regenerative processes. Plant butters such as murumuru, cocoa, jojoba or shea butter enhance occlusion and barrier repair [5]. Ceramides are particularly valuable, as they contribute to the restoration of TEWL, modulation of barrier permeability, and the maintenance of a resilient and diverse skin microbiome. In post-oncologic skin, microbial diversity is often diminished due to inflammation and barrier damage, further supporting the role of microbiome-friendly formulations [23]. Prebiotic components, such as alpha-glucan oligosaccharide, may help promote microbial balance and barrier repair [16]. Caution is required when incorporating alpha-hydroxy acids, as their capacity to alter skin surface pH and disrupt the stratum corneum may exacerbate irritation in vulnerable skin [2]. Oncology-adapted cosmetic formulations should avoid unnecessary additives, especially fragrance compounds, ethanol, and high concentrations of plant extracts rich in allergens [2,28,44]. Because UV radiation exacerbates skin toxicity, photoprotection is considered essential in supportive care. In scalp care, cooling strategies can help reduce discomfort, and topical minoxidil may be used for non-hormonal management of therapy-induced alopecia [2,45,46].

In addition to moisturizers, soothing agents, and emollients, antioxidants constitute a particularly important category of active ingredients in post-oncologic dermocosmetics. These compounds protect cellular structures—including mitochondrial membranes—from oxidative injury, which is heightened during chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Antioxidants prevent lipid peroxidation, neutralize reactive oxygen species, and help re-establish physiological redox balance, which is significantly disrupted during oncologic treatment [5].

Among natural sources, numerous plants extract rich in polyphenols demonstrate potent radical-scavenging capacity and have been investigated for their potential to protect against ionizing radiation—an aspect of particular relevance in post-radiation skin care. Their broad phytochemical composition makes botanical extracts especially attractive for formulations aimed at reducing oxidative stress and supporting tissue regeneration [46]. Vitamin E is a well-established antioxidant commonly incorporated into dermocosmetic formulations, both to stabilize cosmetic base and to provide biological protection to the skin. In a randomized, triple-blind clinical trial evaluating a vitamin E nanoencapsulated cream in women undergoing radiotherapy, the authors reported a potential protective effect of nano-vitamin E, reflected by a delayed onset of radiodermatitis and a lower incidence of mild inframammary erythema [47].

Resveratrol, a polyphenolic antioxidant frequently incorporated into dermocosmetic formulations, has also demonstrated beneficial effects in oncology-related skincare. In a formulation evaluated among patients undergoing chemotherapy, topical application of cream with resveratrol significantly improved epidermal hydration. This effect was attributed to resveratrol’s strong antioxidant capacity, its ability to support endogenous repair processes, and its stimulatory influence on glycosaminoglycan synthesis, which enhances moisture retention in deeper skin layers [48]. Beyond its moisturizing and antioxidant effects, resveratrol has been associated with clinically relevant improvements in skin regeneration and photoaging-related parameters. Experimental and translational studies indicate that resveratrol enhances wound healing quality by supporting fibroblast and keratinocyte migration, improving angiogenesis, and promoting more organized tissue repair, which translates into improved scar quality. In the context of photodamage, resveratrol has demonstrated protective effects against UV-induced oxidative stress, including reduced matrix metalloproteinase activity, preservation of collagen structure, and attenuation of epidermal thickening. Additionally, resveratrol has been shown to protect mitochondrial DNA in human dermal fibroblasts exposed to UVA radiation, providing a rationale linking mitochondrial protection with clinically observed improvements in skin integrity and barrier function [37]. A small randomized study evaluating topical strategies for radiation-induced skin injury reported that a cream formulated with turmeric and sandalwood oil was able to delay or reduce the onset of radiodermatitis in patients undergoing radiotherapy, whereas the application of ascorbic acid, a potent antioxidant, did not demonstrate measurable therapeutic benefit in this context [49]. Another antioxidant of interest for dermocosmetic applications in post-oncologic skin care is quercetin, a naturally occurring polyphenolic flavonoid. Through its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activity, quercetin has demonstrated clinically relevant effects in conditions characterized by chronic inflammation, oxidative stress, and impaired skin regeneration. Evidence indicates that quercetin suppresses pro-inflammatory cytokine expression while enhancing endogenous antioxidant defense systems, contributing to improved redox balance in skin cells. Importantly, quercetin has been identified as a natural activator of mitophagy and a modulator of mitochondrial homeostasis, supporting the removal of dysfunctional mitochondria and promoting cellular resilience [37,50].

Copper tripeptide-1 (GHK-Cu) is a naturally occurring copper-binding tripeptide derived from the Gly-His-Lys sequence originally identified in human plasma [51]. It is widely recognized for its regenerative and anti-aging properties, supporting wound repair, dermal remodeling, and overall skin restoration [52]. By chelating and transporting copper ions essential for lysyl oxidase activity within fibroblast mitochondria, GHK-Cu participates in extracellular matrix maturation and cellular repair processes [53]. GHK-Cu modulates matrix metalloproteinases, enhances collagen, elastin, and glycosaminoglycan synthesis, and promotes fibroblast viability [54]. Preclinical studies have shown that topical GHK-Cu can attenuate chemotherapy-induced alopecia in animal models, accelerating hair regrowth—an effect not reproduced by copper salts or peptide alone without the metal ion [55]. Additional evidence demonstrates that GHK-Cu can penetrate the stratum corneum, facilitating copper ion transport through the lipophilic barrier. This property supports its potential use in topical patches or dermal delivery systems intended for inflammatory or impaired skin conditions [54,56].

In the context of mitochondrial protection, marine-derived raw materials merit particular attention, especially bioactive compounds originating from macroalgae and microalgae. To survive under the harsh and highly variable conditions of the marine environment, characterized by intense solar radiation, salinity fluctuations, and oxidative stress—marine organisms have evolved sophisticated adaptive mechanisms leading to the biosynthesis of structurally diverse and biologically active molecules. Among these compounds, mycosporine-like amino acids (MAA), produced by marine organisms such as phytoplankton and algae in response to elevated oxidative stress, represent a unique class of natural photoprotective agents. MAA act as efficient ultraviolet shields by absorbing UV radiation and dissipating the absorbed energy as harmless heat, thereby preventing photochemical reactions and secondary oxidative damage [57]. In addition, marine algae constitute an important source of bioactive polysaccharides, including fucoidan derived from brown algae. Notably, the biological activity of fucoidan is influenced by its molecular weight, with lower molecular weight fractions exhibiting enhanced tyrosinase inhibition, and suppression of melanogenesis at the cellular level [57,58]. In addition to its anti-photoaging effects, Undaria pinnatifida fucoidan has been shown to reduce mitochondrial ROS, preserve mitochondrial mass and membrane potential, and stimulate mitochondrial biogenesis via the AMPK/SIRT1/PGC-1α pathway in skin cell models exposed to ultraviolet irradiation, providing a mechanistic rationale for mitochondrial protection under conditions of cutaneous oxidative stress [59]. Moreover, extracts derived from the green microalga Chlorella vulgaris have been reported to enhance collagen production in the skin, support tissue regeneration processes, and mitigate wrinkle formation, indicating their potential relevance in skin anti-aging applications [60]. Astaxanthin (ASX) is a xanthophyll carotenoid with potent antioxidant properties, widely recognized for its ability to neutralize singlet oxygen, quench free radicals, and inhibit lipid peroxidation—mechanisms central to its cytoprotective effects [61,62,63]. This red-orange, lipophilic pigment, naturally sourced from microalgae, phytoplankton, and marine organisms, demonstrates markedly higher antioxidant capacity than β-carotene and vitamin E [64]. Owing to its extended conjugated double-bond system, ASX effectively interrupts oxidative chain reactions and exerts additional anti-inflammatory and photoprotective benefits, making it a promising mitochondria-supportive compound for post-oncologic skincare applications [62,65].

In addition to formulation feasibility and regulatory compliance of active ingredients, it should be emphasized that every cosmetic product placed on the European market must undergo a comprehensive safety assessment in accordance with Regulation (EC) No 1223/2009. This assessment is performed by a qualified safety assessor and is documented in the Cosmetic Product Safety Report, which integrates the toxicological profiles of ingredients, exposure assessment, and results of relevant laboratory testing to confirm safe use under normal and reasonably foreseeable conditions.

In the context of post-oncologic skin care, where skin barrier function and tolerance may be compromised, enhanced evaluation strategies are particularly recommended. These include non-invasive instrumental measurements, application and use tests conducted on subjects after oncologic therapy, as well as dermatological testing on sensitive skin. Such an approach ensures that oncology-adapted dermocosmetic products meet both regulatory safety requirements and the specific needs of vulnerable skin populations.

4. Active Ingredients Delivery Systems in Cosmetics

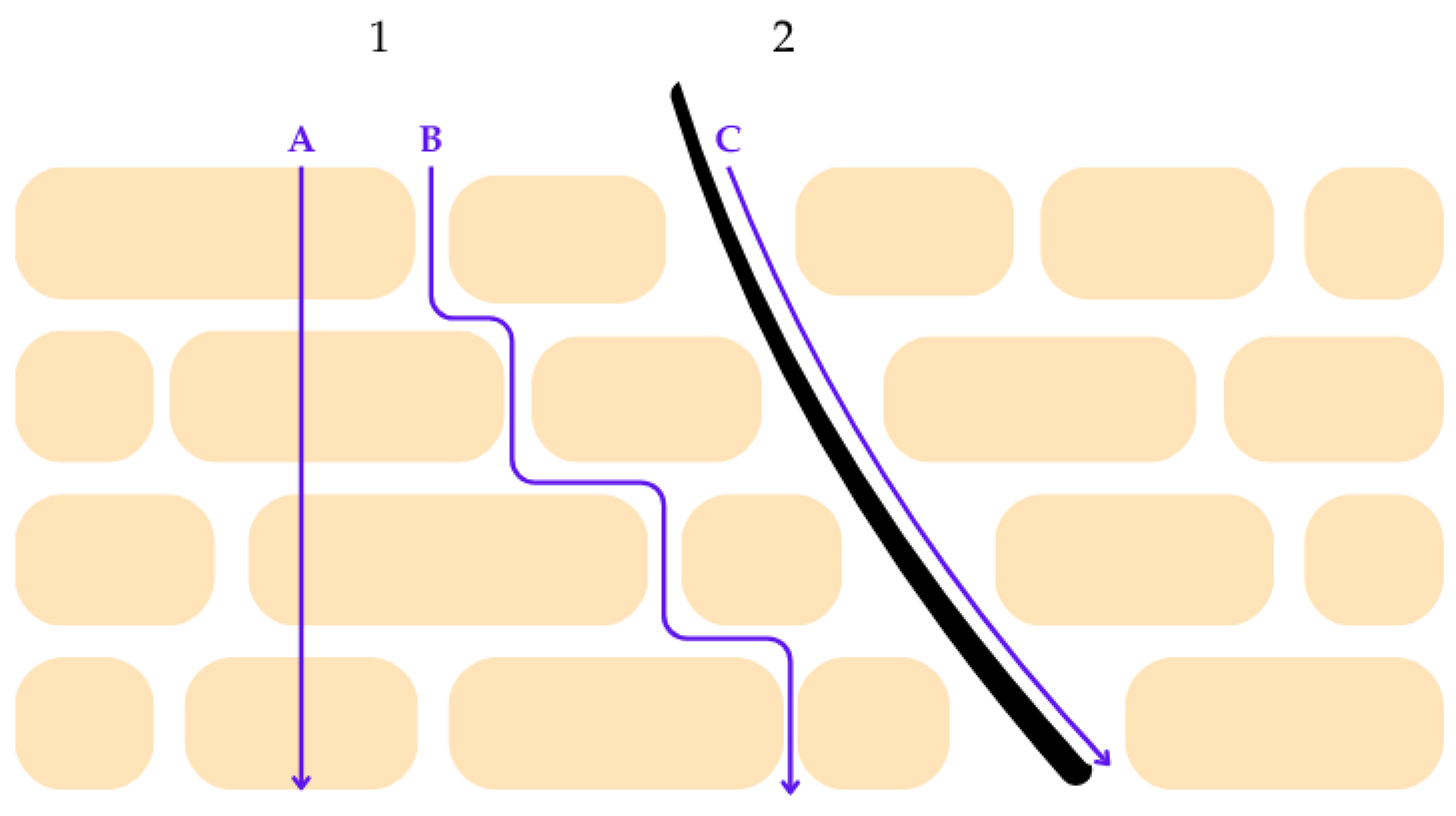

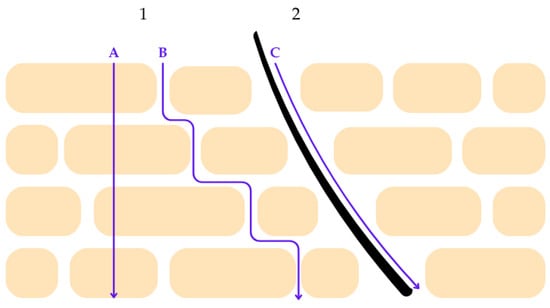

The functional impairment of the epidermal barrier in post-oncologic skin has direct implications for the cutaneous penetration and bioavailability of topical active ingredients. Under physiological conditions, the stratum corneum acts as the principal rate-limiting barrier to percutaneous absorption [66,67]. The permeation of active compounds across this layer may proceed through several pathways, including diffusion along the intercellular lipid structures, passage across corneocytes, and transport via cutaneous appendages such as hair follicles and sweat ducts. The relative contribution of each route depends on the physicochemical properties of the molecule, the structural organization of the stratum corneum lipids, and the integrity of the epidermal barrier [67,68]. Figure 3 summarizes these pathways schematically.

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of percutaneous penetration pathways across the stratum corneum. Route 1 illustrates transepidermal penetration, which comprises two distinct mechanisms: (A) the transcellular pathway, in which molecules diffuse directly through corneocytes, and (B) the intercellular pathway, characterized by diffusion along the lamellar lipid matrix between corneocytes. These pathways are primarily influenced by the physicochemical properties of the penetrant, including molecular size, polarity, and lipophilicity, as well as the structural organization of stratum corneum lipids. Route 2 represents the transappendageal pathway (C), whereby penetration occurs via skin appendages such as hair follicles and sweat ducts. Although this pathway contributes less to overall surface area penetration, it may play a significant role in the delivery of certain actives, particularly in compromised or inflamed skin. The figure highlights the complexity of cutaneous penetration mechanisms relevant to the design of dermocosmetic delivery systems. Reprinted from Ref. [68] (MDPI open access under the terms of the CC-BY license).

Given the compromised barrier function characteristic of irritated skin, understanding and modulating these pathways becomes particularly relevant for topical cosmetic formulations designed for post-oncological patients. Within this framework, agents capable of facilitating transdermal penetration may constitute a key category of functional excipients. For a molecule to efficiently diffuse across the stratum corneum, it must exhibit specific physicochemical properties, including relatively low molecular weight, balanced hydrophilic-lipophilic characteristics, and favorable thermodynamic behavior. Only a limited subset of compounds naturally fulfills these requirements, while most bioactive ingredients display insufficient permeability, preventing them from reaching therapeutic concentrations. Consequently, their topical or systemic activity is markedly reduced. The use of specialized carriers in dermatological and dermocosmetic formulations provides a strategy to overcome these intrinsic limitations by enhancing transport across the epidermal barrier [69].

Penetration enhancers refer to compounds capable of temporarily altering the skin’s barrier characteristics in a controlled manner, thereby facilitating improved passage of active ingredients without causing lasting structural damage. Their use allows formulations to achieve markedly improved performance by enabling active ingredients to reach the intended depth within the skin in concentrations sufficient to exert a therapeutic effect [68,70]. Topical application faces limitations in the context of mitochondrial protection, as many natural antioxidants—essential for mitigating oxidative stress and preserving mitochondrial function—exhibit poor solubility, low stability, or insufficient ability to penetrate the stratum corneum. To address these constraints, increasing research attention has focused on delivery systems such as, for example, lipid-based nanocarriers, which can enhance antioxidant stability, improve penetration, and enable controlled release within the viable epidermis and dermis [10].

4.1. Lipid-Based Nano-Encapsulation Systems

Nanotechnology stands out as a highly promising technological domain of the twenty-first century, creating avenues for advancement across numerous scientific fields, including medicine, pharmaceutical and cosmetic sciences, food technology, medicinal chemistry, bioengineering and genetic engineering. Given the rapid advancement of nanotechnology across multiple scientific domains, particular attention has been directed toward lipid-based nanosystems, which have emerged as highly effective carriers in cosmetic formulations [71,72].

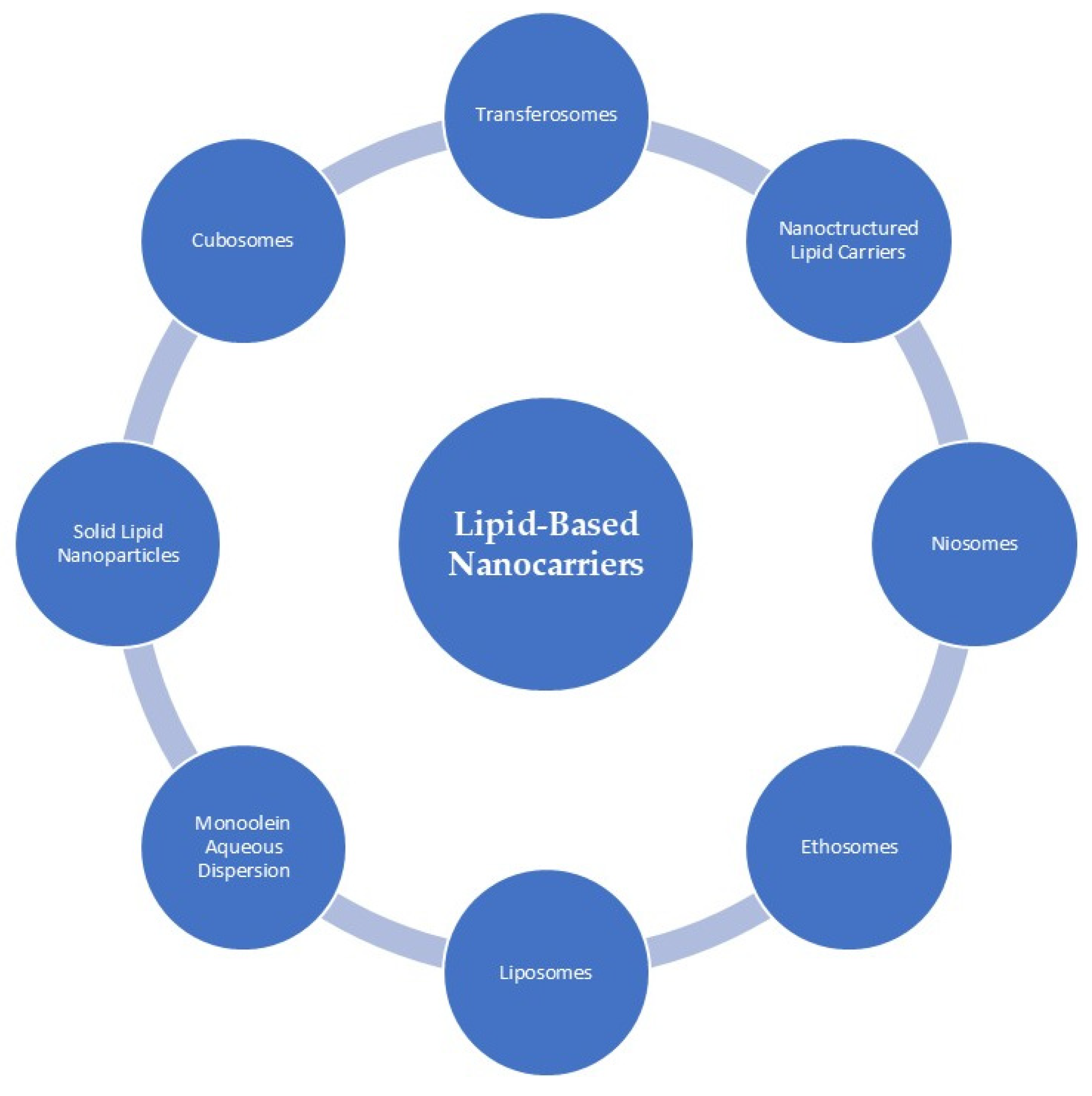

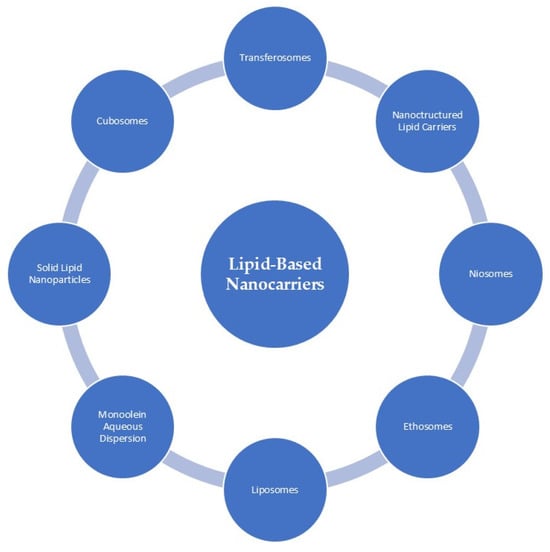

Lipids are recognized biological compounds that contribute structurally to cellular membranes. Characteristically soluble in organic solvents, they comprise hydrocarbons organized into compact lipophilic or amphiphilic assemblies and are fundamental to energy storage [34,73,74]. As a result, lipids have become important materials in cosmetic formulations, particularly in systems designed to transport active ingredients. The use of lipids in cosmetic formulations has grown substantially, largely because their structural properties closely resemble those of epidermal and SC lipids, and because they can improve skin penetration by interacting with the intracellular lipid domains of corneocytes. Through processes such as disrupting lipid packing, altering polarity, or increasing membrane fluidity, lipid-based carriers can facilitate the delivery of active molecules into deeper layers of the skin. Figure 4 presents the overall classification of lipid-based nanocarriers, whereas the following section focuses on those systems that, according to current literature, have been applied for the delivery of antioxidant compounds [34,73].

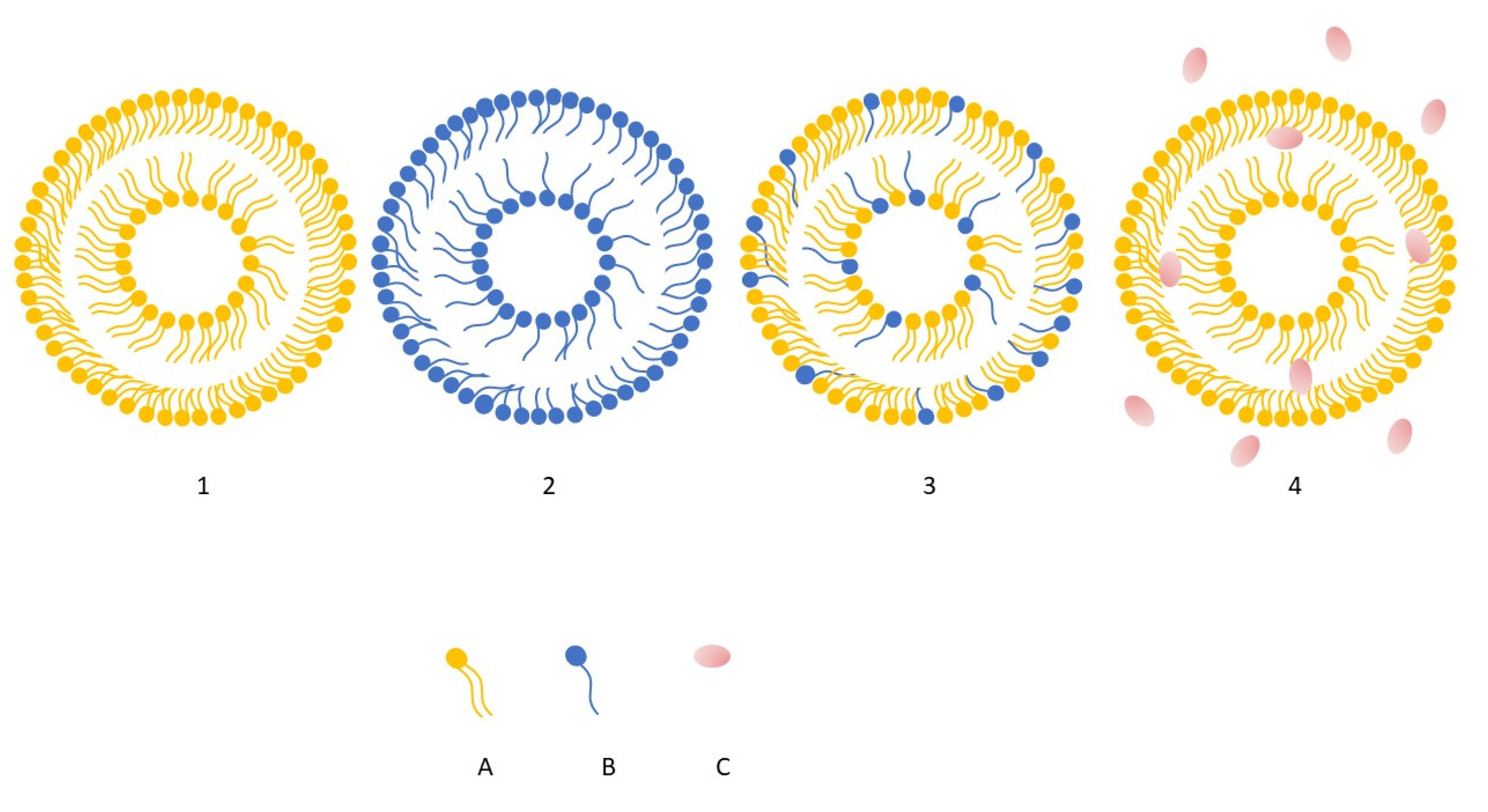

Figure 4.

Classification of lipid-based nanocarriers commonly applied in dermocosmetic formulations. The schematic overview includes liposomes, ethosomes, niosomes, transferosomes, solid lipid nanoparticles (SLN), nanostructured lipid carriers (NLC), cubosomes, and monoolein aqueous dispersions. These carrier systems differ in lipid composition, internal structure, and physicochemical properties, which influence their stability, cutaneous compatibility, and ability to enhance the availability of active compounds within the skin. In cosmetic applications, lipid-based nanocarriers are primarily employed to improve ingredient stability, modulate release profiles, and support penetration into superficial skin layers. Reprinted from Ref. [75] (MDPI open access under the terms of the CC-BY license).

4.2. Liposomes

Liposomal (LPS) delivery systems have become one of the most extensively investigated technologies in modern dermocosmetic formulation science. LPS were first identified in 1961 by British hematologist Dr Alec D. Bangham, with the initial description published in 1964 at the Babraham Institute in Cambridge. The term “liposome” is derived from the Greek words lipos (fat) and soma (body), reflecting their fundamental nature as lipid-based vesicular structures [76]. These vesicular structures, composed of concentric phospholipid bilayers, are capable of entrapping both water-soluble and lipid-soluble active compounds. Their high biocompatibility and close resemblance to cellular membranes render them particularly suitable for topical administration. A key benefit of employing liposomal delivery systems is their ability to markedly enhance the stability of labile antioxidant molecules [69,77,78,79,80]. This advantage stems from the intrinsic properties of liposomes as highly biocompatible, flexible, and non-toxic carriers capable of shielding sensitive actives from degradation and maintaining their functional integrity [81]. The physicochemical behavior of liposomes varies markedly depending on their lipid composition, as the specific constituents of the bilayer govern key characteristics such as membrane rigidity, vesicle size, release dynamics, and overall surface charge [82]. Phospholipids constitute the fundamental structural framework of liposomes, where their amphiphilic nature drives the spontaneous assembly into bilayer vesicles upon dispersion in aqueous media. Depending on their origin, phospholipids may be obtained from natural sources—such as phosphatidylcholine, phosphatidylserine, or phosphatidylinositol—or produced synthetically, including dipalmitoyl phosphatidylcholine or hydrogenated soy phosphatidylcholine. The specific phospholipid composition governs key attributes of the liposomal membrane, including its fluidity, surface charge, and interactions with biological tissues, thereby shaping encapsulation efficiency, release kinetics, and cutaneous penetration. In addition to phospholipids, cholesterol is a critical structural component of many liposomal systems. By inserting between the hydrocarbon chains of the bilayer, cholesterol modulates membrane order and reduces excessive lipid mobility, which leads to decreased permeability and improved mechanical robustness of the vesicle. Through interactions between its hydroxyl group and the polar regions of adjacent phospholipids, cholesterol contributes to tighter molecular packing and enhanced resistance to destabilizing environmental factors. As a result, appropriate cholesterol incorporation is widely used to optimize liposome rigidity, stability, and overall performance in topical formulations [83].

Encapsulation within phospholipid bilayers shields polyphenols from degradation induced by oxygen, light exposure, and thermal fluctuations, thereby preserving their chemical integrity and biological activity over time [77,84,85,86]. Furthermore, the nanoscale dimensions of liposomal carriers, combined with their amphiphilic character, facilitate more efficient traversal of the stratum corneum [10,84]. Another important feature of liposomal systems is their ability to provide controlled and prolonged release of encapsulated actives. This sustained delivery profile supports continuous antioxidant activity within the skin microenvironment, which is especially advantageous for formulations aimed at mitigating oxidative stress, promoting epidermal regeneration, or preventing photoaging.

4.3. Niosomes

Niosomes (NIS) represent a versatile and increasingly prominent class of vesicular nanocarriers, characterized by their bilayer architecture composed of amphiphilic nonionic surfactants in combination with lipidic components, typically cholesterol [87,88,89]. Owing to this unique structural organization, niosomal systems have attracted substantial interest in cosmetic and dermatological applications. The earliest commercial application of niosomes in skincare dates back to the 1970s, when L’Oréal developed an oil-in-water anti-ageing emulsion utilizing these vesicular systems [90,91]. This innovation later reached the cosmetic market in 1986 through Lancôme, a brand within the L’Oréal group, with the launch of a product marketed under the name Niosôme [91,92,93]. Compared with conventional liposomes, niosomes often demonstrate enhanced physicochemical stability and a superior ability to penetrate the skin barrier, making them an appealing alternative for the delivery of active ingredients in topical formulations [75,76,91]. The incorporation of nonionic surfactants offers distinct advantages for topical and transdermal delivery, as these materials are widely recognized for their favorable safety profile and markedly lower irritancy when compared with cationic or anionic surfactants [75]. These benefits have further contributed to the growing preference for niosomes over traditional liposomes, as the phospholipids used in liposomal systems are particularly susceptible to hydrolysis, oxidation, and rancidity—factors that compromise storage stability and reduce the bioavailability of encapsulated compounds. In niosomal formulations, the choice of surfactants is guided by parameters such as the hydrophilic–lipophilic balance (HLB) and the critical packing parameter (CPP), which support the selection of materials capable of forming stable vesicular structures. HLB values below 9 typically indicate oil-soluble surfactants, whereas values above 11 correspond to water-soluble ones. CPP helps predict whether the resulting assemblies will form spherical, non-spherical, bilayer, or inverted vesicles [75,76]. The preparation of niosomes involves selecting techniques that allow control over key structural parameters, including vesicle size, bilayer composition, and encapsulation efficiency [94]. Sonication is commonly used when smaller and more uniform vesicles are desired [94,95]. Niosomes are also valued for their ability to provide sustained release and to enhance delivery of active compounds to targeted skin layers. In cosmetic applications, these properties support their use in photoprotective formulations, where niosomes contribute to improved stability and controlled release of UV filters. By retaining sunscreens predominantly within the upper layers of the skin, niosomes may reduce systemic absorption while enhancing localized photoprotection—an aspect of particular relevance in skincare for individuals recovering from oncological treatments, where robust photoprotection is essential [94,96].

4.4. Transferosomes

The term transferosome was introduced in the early 1990s and is derived from Latin and Greek roots meaning “to carry” and “body,” referencing their role as deformable vesicular carriers capable of navigating the skin barrier [97]. Transferosomes (TFS) are highly flexible phospholipid-based vesicles composed of a bilayer enriched with edge activators—typically surfactants or other bilayer-modifying agents—that markedly enhance membrane elasticity and allow the vesicles to pass through narrow intercellular pathways of the stratum corneum. Owing to this deformable structure, transferosomes improve the stability, solubility, and dermal deposition of incorporated actives, while facilitating partitioning into the stratum corneum and transiently increasing lipid fluidity within the barrier [98,99]. They have attracted considerable interest as transdermal carriers because their ultra-flexible membranes enable the transport of larger quantities of active compounds into deeper cutaneous layers. Their penetration is driven by hydration or osmotic gradients, enabling transferosomes to enter the stratum corneum through both intercellular and transcellular pathways. As amphiphilic vesicles, they are capable of encapsulating hydrophilic and hydrophobic substances alike, broadening their applicability in topical and transdermal delivery [97,100]. The vesicular bilayer is typically constructed from natural or synthetic phospholipids, most commonly soy lecithin or phosphatidylcholine, which determine vesicle size, zeta potential, encapsulation efficiency, and membrane permeability. Edge activators constitute 10–25% of the vesicle composition and serve to soften the bilayer, enhancing its deformability and permeability [97]. Higher concentrations of surfactants are generally associated with reduced vesicle size and increased deformability [97,101]. Surface charge significantly influences skin permeation. Positively charged vesicles tend to demonstrate higher penetration efficiency compared with neutral or negatively charged vesicles, primarily due to electrostatic interactions with the negatively charged skin surface [97]. Transferosomes are therefore characterized by two essential features: high bilayer elasticity (ultra-deformability) and the ability to exploit hydration gradients across the skin, both of which contribute to improved permeation, deeper deposition, and controlled release of actives within target layers [97,102]. The penetration of transferosomes is mechanistically linked to osmotic gradients that arise when water evaporates from the vesicle suspension upon topical application. Their hydrophilic surface and strong water-binding capacity promote movement toward the more hydrated compartments of the epidermis, enabling spontaneous migration across the stratum corneum. Ultra-elastic membranes allow the vesicles to pass through microscopic pores, while the hydration gradient guides their progression from the dry outer stratum corneum to deeper, water-rich regions where vesicles rehydrate. This process is further supported by transepidermal water flux, which gradually dehydrates vesicles in the outer barrier and propels them into the viable epidermis. The lipid-to-surfactant ratio plays a crucial role in ensuring reversible bilayer deformation without compromising vesicle integrity or disturbing skin barrier structure. Overall, transferosome uptake reflects the dynamic gradient of water activity between the atmosphere, stratum corneum, and deeper epidermal layers [102]. Despite their advantages, several limitations have been noted. The hydrophilic surface of transferosomes may reduce loading efficiency for lipophilic molecules compared with liposomes. High concentrations of edge activators can promote transient pore formation within the bilayer, increasing the risk of leakage. Additionally, the hydration gradient within human skin is not uniform, which can affect the osmotic driving force and potentially result in depot formation within the stratum corneum. Moreover, large-scale manufacturing and industrial upscaling remain technically challenging, limiting broader commercial implementation [97].

4.5. Ethosomes

Ethosomes (ETH), first introduced by Touitou in 1996, are ultra-deformable, ethanol-rich vesicles designed to enhance the dermal delivery of active compounds, particularly those with high molecular weight or poor aqueous solubility, such as antioxidant agents [10,103]. Structurally, ethosomes are nanosized carriers composed of 2–5% phospholipids and a high ethanol content (20–40%), which distinguishes them from conventional liposomes. The elevated ethanol concentration imparts a negative surface charge and contributes to improved vesicle stability, flexibility, and dermal penetration [103].

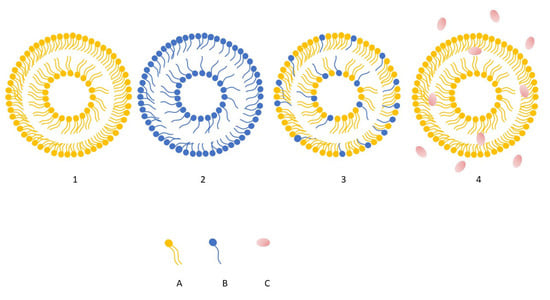

The combined action of phospholipids and ethanol is central to their delivery performance. Ethanol disrupts and fluidizes the highly ordered lipids of the stratum corneum while simultaneously increasing the elasticity of the ethosomal bilayer. As a result, the altered lipid packing of the skin allows the highly deformable ethosomal vesicles to pass through microscopic pathways within the barrier and transport encapsulated actives into deeper layers of the epidermis and dermis. Recent developments have led to advanced ethosomal systems—such as binary ethosomes and transethosomes, which further optimize penetration efficiency and structural stability [103]. Figure 5 illustrates the structural differences between three major vesicular nanocarrier systems used in dermal and transdermal delivery, namely conventional ethosomes, liposomes, niosomes, and transferosomes. Although all three share a bilayer-based structure, their composition and membrane organization differ, particularly in terms of phospholipid content, presence of nonionic surfactants or ethanol [10,104].

Figure 5.

Schematic illustration showing structural differences among liposomes (1), niosomes (2), transferosomes (3), ethosomes (4). Element (A) represent phospholipids, whereas (B) surfactants, (C) ethanol, predominantly present in the surrounding hydroalcoholic phase. For clarity and schematic simplicity, cholesterol has been omitted from the illustration [own work].

4.6. Lipid Nanoparticles

Lipid-based nanoparticles, including solid lipid nanoparticles (SLN) and nanostructured lipid carriers (NLC), represent an important class of topical delivery systems composed of physiologically relevant solid lipids stabilized by surfactants, forming colloidal particles stable at both room and body temperature [73,105,106]. Owing to their occlusive properties, these carriers enhance skin hydration and reinforce barrier integrity—features that, as previously discussed, are essential in post-oncologic skincare. Their lipidic composition contributes to low toxicity, high chemical stability, and efficient protection of light- or oxidation-sensitive actives such as retinol, coenzyme Q10, tocopherol, and ascorbyl palmitate [73,106]. However, the highly ordered crystalline structure of SLN may limit loading capacity and promote expulsion of entrapped compounds during storage [106,107]. NLC—considered the second generation of lipid nanoparticles—combine solid and liquid lipids, creating a less ordered matrix that enables higher encapsulation efficiency, reduced compound expulsion, and improved long-term stability. Increased proportions of liquid lipids can enhance physical stability, whereas lower amounts may support improved skin absorption [106]. Both SLN and NLC can enhance the dermal bioavailability of natural antioxidants due to their nanoscale dimensions, film-forming behavior, and close interaction with the stratum corneum [108]. These systems increase hydration, disrupt lipid packing, and widen intercorneocyte spaces, thereby facilitating penetration of encapsulated bioactives [106]. Surfactants present in the formulation may further fluidize SC lipids, promoting permeation. Beyond the epidermis, lipid nanoparticles can also target hair follicles, which function as long-term reservoirs capable of retaining actives for extended periods—a property particularly relevant in addressing chemotherapy-induced alopecia [106,107]. Key physicochemical parameters—including particle size, morphology, surface charge, and diffusional properties—critically influence skin penetration and release kinetics [106,107,109]. Collectively, SLN and NLC offer a biocompatible, solvent-free platform for delivering antioxidant and mitochondria-protective actives in topical formulations.

Overall, these lipid-based vesicular and particulate systems provide a versatile toolbox for enhancing the topical delivery of mitochondria-protective antioxidants in post-oncologic skin care. Their ability to protect labile molecules, modulate release kinetics, and improve cutaneous penetration is particularly relevant in skin that remains fragile, inflamed, and prone to oxidative imbalance after cancer treatment. To translate these technological concepts into practical dermocosmetic applications, it is essential to examine current experimental and clinical evidence on antioxidant-loaded lipid carriers.

5. Encapsulation of Antioxidant Actives in Lipid-Based Carriers: Recent Evidence

Lipid-based nanocarriers have been widely investigated as delivery platforms for antioxidant actives, with a focus on improving their stability, skin penetration, and overall topical performance. Recent publications describe a range of formulations incorporating various natural and synthetic antioxidants, evaluated through in vitro, ex vivo, and in vivo approaches. Table 2 summarizes representative studies from 2020 to 2025, outlining the delivery system used, the encapsulated antioxidant, and the main dermatological outcomes reported.

Nanocarrier technology has broad applications in functional cosmetics, enabling targeted delivery of active ingredients, sustained and controlled release, and improved stability and compatibility of sensitive compounds. Natural plant actives, increasingly favored by consumers, often face challenges such as poor solubility, low skin permeability, and irritation, which nanocarriers can overcome. Specially designed nanocarriers can co-deliver multiple actives with different physicochemical properties, achieving synergistic multi-target effects [110].

Table 2 provides an overview of lipid-based and advanced delivery systems for antioxidant actives and their key dermatological outcomes. Among the evaluated systems, nanostructured lipid carriers (NLC) and transferosomes (TFS) consistently demonstrate superior performance in enhancing skin penetration, stability, and controlled release. Liposomes and niosomes also show notable benefits, particularly in reducing inflammation and supporting epidermal integrity. These findings highlight NLC and TFS as the most promising carriers for dermocosmetic formulations aimed at mitigating oxidative stress and supporting mitochondrial protection in post-oncologic skin.

Table 2.

Overview of lipid-based and advanced delivery systems used for antioxidant actives and their key dermatological outcomes.

Table 2.

Overview of lipid-based and advanced delivery systems used for antioxidant actives and their key dermatological outcomes.

| Delivery System | Active Antioxidant | Key Findings | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| LPS | Ectoin + Haematococcus pluvialis extract (astaxanthin) + tetrahexyldecyl ascorbate | Pro-inflammatory cytokine reduction | [78] |

| LPS | GHK-Cu | Inhibition of elastase, reduction in the rate of elastin degradation, support of epidermal integrity | [54] |

| LPS | Niacinamide | Superior skin penetration and enhanced whitening efficacy cationic liposoms compared with neutral or anionic liposomes | [111] |

| LPS, TFS, ETH, Cerosomes | Coenzyme Q10 (Co-Q10) | The best efficacy of transethosomes as carriers for local delivery of Co-Q10 in the treatment of male androgenetic alopecia | [112] |

| ETH | Tocopherol Acetate | Improved skin retention, higher enhancement ratio, and strong targeting efficiency | [113] |

| ETH | Rutin | Transethosomes showed favorable nanovesicle properties, enhanced drug release, improved skin permeation, and stronger antibacterial activity than rutin suspension | [114] |

| SLN | α-Tocopherol | SLNs increased α-Tocopherol permeation and hydration of skin | [115] |

| NLC | α-Tocopherol | Improved stability of vitamin E and enhanced moisturizing and anti-aging effects | [116] |

| NLC/SLN | Co-Q10 | Q10-SLN improved penetration; both systems lowered ROS. Q10-NLC reduced melanin via tyrosinase inhibition and was more effective than free co-Q10 and Q10-SLN | [117] |

| NLC | Astaxanthin | Encapsulation into NLC effectively improved the thermal stability of ASTA and enhanced its UV stability through the protective NLC barrier | [118] |

| NLC | Curcumin | Dual NLC–hydrogel enhanced curcumin’s antioxidant activity, improved dermal cell responses, and enabled membrane penetration | [119] |

| NLC | Tocopherol | Delayed radiodermatitis onset with vitamin E- containing nanocream | [47] |

| NLC, Nanoemulsion Gel (NEG) | Resveratrol | NLCs showed higher antioxidant activity and better safety than NEGs | [120] |

| NLC | Dihydrooxyresveratrol | Extended dihydroxyresveratrol release, improved lipophilic membrane penetration, and hyperpigmentation-brightening potential | [121] |

| NLC | Quercetin, Omega-3 Fatty Acid | Quercetin–omega-3 NLC hydrogels offered strong antioxidant protection and promise for preventing skin damage | [122] |

| NLC | Resveratrol | Controlled release and anti-inflammatory activity | [123] |

| NLC | Hesperidin | Sustained release and enhanced anti-psoriatic efficacy of optimized hesperidin-NLC gel | [124] |

| NLC | Quercitin | NLC-enriched hydrogels increased quercetin retention in the skin and showed significant photoprotective effects against UVB-induced damage | [125] |

| TFS | Quercitin | Sustained release, strong permeation, and synergistic anti-inflammatory effect of quercitin-loaded tranferosomes | [126] |

| TFS, NIS | Melatonin | Melatonin-loaded transfersomes exhibited significant anti-inflammatory activity and stimulated collagen synthesis in vitro | [127] |

| NIS | Curcumin | Encapsulation of curcumin in a niosomal formulation markedly enhanced its antioxidant and anticancer activity | [128] |

| NIS | Curcumin | Niosomes enhanced curcumin’s antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory efficacy by improving delivery to the target site | [129] |

| NIS | Apigenin | Enhanced permeation and superior antioxidant, antibacterial, and anti-inflammatory effects of NIS gel with apigenin | [130] |

6. Summary and Future Perspectives

Lipid-based delivery systems have gained substantial attention in recent years due to their biocompatibility, ability to enhance dermal penetration, and capacity to protect unstable antioxidants from degradation. However, despite their technological advantages, the number of studies specifically investigating lipid carriers for antioxidant delivery in the context of post-oncologic skin care remains limited. Among the available evidence, nanocapsulated vitamin E demonstrated a potential protective effect by delaying the onset of radiodermatitis and reducing the incidence of mild inframammary erythema in women undergoing radiotherapy [47]. Other studies suggest that lipid-based quercetin formulations can enhance skin photoprotection [125]. This makes them a promising solution for UV protection creams for sensitive skin, which is particularly important in designing dermocosmetic strategies to support photosensitive and treatment-damaged skin. Encapsulation of tocopherol has been shown to improve its moisturizing and barrier-supporting function, while niosomal delivery significantly potentiated the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity of resveratrol [115,116,120,123]. Transferosome-loaded melatonin exhibited both anti-inflammatory action and collagen-stimulating effects, indicating additional benefits for skin regeneration [127]. Coenzyme Q10 encapsulated in lipid nanoparticles enhanced follicular targeting and demonstrated beneficial effects in androgenetic alopecia models, whereas GHK-Cu showed the capacity to inhibit elastase, reduce elastin degradation, and improve epidermal integrity properties valuable for damaged, xerotic post-oncologic skin [54,112]. Moreover, astaxanthin delivered via NLC showed superior skin penetration with preservation of antioxidant activity, reinforcing its promise as a mitochondria-protective cosmetic ingredient [118].

Overall, these findings underscore the broad potential of lipid-based nanocarriers to improve the stability, bioavailability, and dermal performance of antioxidant actives. Nevertheless, the application of such systems in post-oncologic skincare remains underexplored. Current dermocosmetic formulations dedicated to this population pre-dominantly emphasize occlusion, barrier restoration, and protection—elements that are undeniably essential for highly reactive, xerotic, and structurally compromised skin. However, despite their relevance, these approaches do not fully address a major pathogenic mechanism in post-treatment cutaneous dysfunction: persistent oxidative stress and increased mitochondrial vulnerability. Integrating advanced encapsulation systems with antioxidants of proven mitoprotective activity may open new therapeutic avenues for restoring epidermal homeostasis, reducing inflammation, and improving quality of life for cancer survivors. Mitochondria-protective antioxidant ingredients, which are capable of scavenging reactive oxygen species, represent a promising, yet underutilized, strategy for restoring cellular homeostasis in damaged skin.

The cosmetic actives discussed in this review are well-established ingredients with a long history of use in dermocosmetic formulations and well-characterized safety profiles. However, despite their widespread application in general skin care products, these compounds have not been specifically developed or systematically evaluated in formulations intended for post-oncologic skin. This gap highlights a disconnect between existing cosmetic knowledge and the specific needs of skin affected by oncologic therapies, which are characterized by impaired barrier function, increased sensitivity, and reduced regenerative capacity. Addressing this gap may support the development of more targeted cosmetic strategies for this vulnerable skin population.

While existing literature and commercially available dermocosmetic products for oncology patients predominantly focus on barrier repair, hydration, emolliency, and occlusive protection, the role of oxidative stress-mediated mitochondrial dysfunction in post-oncologic skin damage remains underexplored from a cosmetic formulation perspective. Unlike previous works that primarily emphasize penetration enhancement or anti-aging outcomes, this review positions mitochondrial protection as a central mechanistic framework linking oxidative stress, impaired regeneration, and long-term skin sensitivity in post-oncologic patients. In particular, we highlight how lipid-based delivery systems may indirectly support mitochondrial function by improving the stability, bioavailability, and cutaneous deposition of antioxidant actives. By bridging the clinical manifestations of post-oncologic skin damage with formulation science, this review aims to identify delivery strategies most relevant for the development of next-generation dermocosmetic products tailored to oncology-adapted skin care.

Future research should focus on advancing lipid nanocarriers as platforms for antioxidant delivery, with the ultimate goal of improving skin resilience, mitigating chronic inflammation, and supporting long-term cutaneous recovery in post-oncologic patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.B.; writing—original draft preparation, A.B.; writing—review and editing, A.F.-G. and A.W.; visualization, A.B.; supervision, A.F.-G. and A.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Latech Bernard Latanowicz (LaQ brand) for supporting this research within the ‘Implementation PhD’ Program.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Agata Burzyńska was employed by the company Latech Bernard Latanowicz (LaQ brand). The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ASX | Astaxanthin |

| ATP | Adenosine Triphosphate |

| CPP | Critical Packing Parameter |

| Co-Q10 | Coenzyme Q10 |

| Drp1 | Dynamin-related protein 1 |

| ER | Endoplasmic Reticulum |

| ETC | Electron Transport Chain |

| ETH | Ethosomes |

| GHK-Cu | Copper Trpeptide-1 |

| HLB | Hydrophilic-Lipophilic Balance |

| LC3 | Microtubule-associated protein light chain |

| LPS | Liposomes |

| MAA | Mycosporine-like amino acids |

| MFN1/2 | Mitofusins |

| mtDNA | Mitochondrial DNA |

| mtROS | Mitochondrial ROS |

| NAD+ | Precursor of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide |

| NEG | Nanoemulsion gel |

| NIS | Niosomes |

| NLC | Nanostructured Lipid Carriers |

| Nrf2 | Nuclear Factor Erythroid 2-Related Factor 2 |

| OPA1 | Optic Atrophy Protein 1 |

| OXPHOS | Oxidative Phosphorylation Efficiency |

| P | Phosphorylation |

| PGC-1α | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| SC | Stratum Corneum |

| SLN | Solid Lipid Nanoparticles |

| TCA | Tricarboxylic Acid Cycle |

| TEWL | Transepidermal Water Loss |

| TFS | Transferosomes |

| UV A | Ultraviolet A |

| Ub | Ubiquitin |

References

- Słonimska, P.; Sachadyn, P.; Zielinski, J.; Skrzypski, M.; Pikuła, M. Chemotherapy-Mediated Complications of Wound Healing: An Understudied Side Effect. Adv. Wound Care 2024, 13, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreno, B.; Khosrotehrani, K.; De Barros Silva, G.; Wolf, J.R.; Kerob, D.; Trombetta, M.; Atenguena, E.; Dielenseger, P.; Pan, M.; Scotte, F.; et al. The Role of Dermocosmetics in the Management of Cancer-Related Skin Toxicities: International Expert Consensus. Support. Care Cancer 2023, 31, 672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ladwa, R.; Fogarty, G.; Chen, P.; Grewal, G.; McCormack, C.; Mar, V.; Kerob, D.; Khosrotehrani, K. Management of Skin Toxicities in Cancer Treatment: An Australian/New Zealand Perspective. Cancers 2024, 16, 2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida, V.; Pires, D.; Silva, M.; Teixeira, M.; Teixeira, R.J.; Louro, A.; Dinis, M.A.P.; Ferreira, M.; Teixeira, A. Dermatological Side Effects of Cancer Treatment: Psychosocial Implications—A Systematic Review of the Literature. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mourelle, M.L.; Gómez, C.P.; Legido, J.L. Cosmeceuticals and Thalassotherapy: Recovering the Skin and Well-Being after Cancer Therapies. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsch, A.; Leboeuf, N.R.; Lacouture, M.E.; McLellan, B.N. Dermatologic Adverse Events of Systemic Anticancer Therapies: Cytotoxic Chemotherapy, Targeted Therapy, and Immunotherapy. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book 2020, 40, 485–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natarelli, N.; Gahoonia, N.; Aflatooni, S.; Bhatia, S.; Sivamani, R.K. Dermatologic Manifestations of Mitochondrial Dysfunction: A Review of the Literature. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sguizzato, M.; Pepe, A.; Baldisserotto, A.; Barbari, R.; Montesi, L.; Drechsler, M.; Mariani, P.; Cortesi, R. Niosomes for Topical Application of Antioxidant Molecules: Design and In Vitro Behavior. Gels 2023, 9, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.S.; Bawiskar, D.; Wagh, V. Nanocosmetics and Skin Health: A Comprehensive Review of Nanomaterials in Cosmetic Formulations. Cureus 2024, 16, e52754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, A.; Stefanuto, L.; Gasperi, T.; Bruni, F.; Tofani, D. Lipid Nanovesicles for Antioxidant Delivery in Skin: Liposomes, Ufasomes, Ethosomes, and Niosomes. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sontheimer, R.D. Skin Is Not the Largest Organ. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2014, 134, 581–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yousef, H.; Alhajj, M.; Fakoya, A.O.; Sharma, S. Anatomy, Skin (Integument), Epidermis; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Lotfollahi, Z. The Anatomy, Physiology and Function of All Skin Layers and the Impact of Ageing on the Skin. Wound Pract. Res. 2024, 32, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rübe, C.E.; Freyter, B.M.; Tewary, G.; Roemer, K.; Hecht, M.; Rübe, C. Radiation Dermatitis: Radiation-Induced Effects on the Structural and Immunological Barrier Function of the Epidermis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwashita, K.; Suzuki, K.; Ojima, M. Recent Advances in Understanding of Radiation-Induced Skin Tissue Reactions with Respect to Acute Tissue Injury and Late Adverse Effect. J. Radiat. Res. 2025, 66, 437–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreira, A.L.; Forneck, H.R.; Portilho, L. Skin Alterations Caused by Chemotherapies and Cosmetic Strategies for Soothing These Effects: A Review. J. Clin. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2021, 5, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouwstra, J.A.; Nădăban, A.; Bras, W.; McCabe, C.; Bunge, A.; Gooris, G.S. The Skin Barrier: An Extraordinary Interface with an Exceptional Lipid Organization. Prog. Lipid Res. 2023, 92, 101252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefèvre-Utile, A.; Braun, C.; Haftek, M.; Aubin, F. Five Functional Aspects of the Epidermal Barrier. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiyama, F.; Takahashi, N.; Ueda, Y.; Tada, S.; Takeuchi, N.; Ohno, Y.; Kihara, A. Correlations between Skin Condition Parameters and Ceramide Profiles in the Stratum Corneum of Healthy Individuals. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 8291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamae, N.; Ogai, K.; Kunimitsu, M.; Fujiwara, M.; Nagai, M.; Okamoto, S.; Okuwa, M.; Oe, M. Relationship between Severe Radiodermatitis and Skin Barrier Functions in Patients with Head and Neck Cancer: A Prospective Observational Study. Asia Pac. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2025, 12, 100625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazdrowski, J.; Polańska, A.; Kaźmierska, J.; Kowalczyk, M.J.; Szewczyk, M.; Niewinski, P.; Golusiński, W.; Dańczak-Pazdrowska, A. The Assessment of the Long-Term Impact of Radiotherapy on Biophysical Skin Properties in Patients after Head and Neck Cancer. Medicina 2024, 60, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolaou, A.; Kendall, A.C. Bioactive Lipids in the Skin Barrier Mediate Its Functionality in Health and Disease. Pharmacol. Ther. 2024, 260, 108681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, B.N.; Lin, J.; Buchwald, Z.S.; Bai, J. Skin Microbiome and Treatment-Related Skin Toxicities in Patients with Cancer: A Mini-Review. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 924849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Z.; Xu, C.; Song, B.; Zhang, S.; Chen, C.; Li, C.; Zhang, S. Tissue Fibrosis Induced by Radiotherapy: Current Understanding of the Molecular Mechanisms, Diagnosis and Therapeutic Advances. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nan, L.; Guo, P.; Hui, W.; Xia, F.; Yi, C. Recent Advances in Dermal Fibroblast Senescence and Skin Aging: Unraveling Mechanisms and Pioneering Therapeutic Strategies. Front. Pharmacol 2025, 16, 1592596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazdrowski, J.; Gornowicz-Porowska, J.; Kaźmierska, J.; Krajka-Kuźniak, V.; Polanska, A.; Masternak, M.; Szewczyk, M.; Golusiński, W.; Danczak-Pazdrowska, A. Radiation-Induced Skin Injury in the Head and Neck Region: Pathogenesis, Clinics, Prevention, Treatment Considerations and Proposal for Management Algorithm. Rep. Pract. Oncol. Radiother. 2024, 29, 373–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, F.A.; Manan, H.A.; Mustapha, A.W.M.M.; Sidek, K.; Yahya, N. Ultrasonographic Evaluation of Skin Toxicity Following Radiotherapy of Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh Dagher, S.; Blom, A.; Chabanol, H.; Funck-Brentano, E. Cutaneous Toxicities from Targeted Therapies Used in Oncology: Literature Review of Clinical Presentation and Management. Int. J. Womens Dermatol. 2021, 7, 615–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nepon, H.; Safran, T.; Reece, E.M.; Murphy, A.M.; Vorstenbosch, J.; Davison, P.G. Radiation-Induced Tissue Damage: Clinical Consequences and Current Treatment Options. Semin. Plast. Surg. 2021, 35, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad Jamil, H.; Abdul Karim, N. Mitochondrial Homeostasis: Exploring Their Impact on Skin Disease Pathogenesis. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2025, 189, 118349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martic, I.; Papaccio, F.; Bellei, B.; Cavinato, M. Mitochondrial Dynamics and Metabolism across Skin Cells: Implications for Skin Homeostasis and Aging. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1284410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, J.; Yu, Q.; Huang, G.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, N. Advances in Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Radiation Tissue Injury. Front. Physiol. 2025, 16, 1660330. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ibraheem, K.; Smith, A.; Collett, A.; Georgopoulos, N.T. Prevention of Chemotherapy Drug-Mediated Human Hair Follicle Damage: Combined Use of Cooling with Antioxidant Suppresses Oxidative Stress and Prevents Matrix Keratinocyte Cytotoxicity. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1558593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallan, S.S.; Ferrara, F.; Cortesi, R.; Sguizzato, M. Potential of the Nano-Encapsulation of Antioxidant Molecules in Wound Healing Applications: An Innovative Strategy to Enhance the Bio-Profile. Molecules 2025, 30, 641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, X.; Li, H.; Lee, J.S.; Lee, D.H. Role of Mitochondrial Dysfunction in UV-Induced Photoaging and Skin Cancers. Exp. Dermatol. 2025, 34, e70114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, T.; Li, R.; Gao, T. Role of Mitochondrial Dynamics in Skin Homeostasis: An Update. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golubnitschaja, O.; Sargheini, N.; Bastert, J. Mitochondria in Cutaneous Health, Disease, Ageing and Rejuvenation—The 3PM-Guided Mitochondria-Centric Dermatology. EPMA J. 2025, 16, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, D.C. Mitochondrial Dynamics and Its Involvement in Disease. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2020, 15, 235–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Kroemer, G.; Kepp, O. Mitophagy: An Emerging Role in Aging and Age-Associated Diseases. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Pang, Y.; Fan, X. Mitochondria in Oxidative Stress, Inflammation and Aging: From Mechanisms to Therapeutic Advances. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Martín, M.E.; Tarazona, J.V.; Hernández-Cano, N.; Mayor Ibarguren, A. The Importance of Cosmetics in Oncological Patients. Survey of Tolerance of Routine Cosmetic Care in Oncological Patients. Cosmetics 2025, 12, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deantonio, L.; Borgonovo, G.; Caverzasio, S.; Piliero, M.A.; Canino, P.; Puliatti, A.; Zilli, T.; Valli, M.C.; Richetti, A. Hyaluronic Acid 0.2% Cream for Preventing Radiation Dermatitis in Breast Cancer Patients Treated with Postoperative Radiotherapy: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. Breast 2025, 82, 104513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boo, Y.C. Mechanistic Basis and Clinical Evidence for the Applications of Nicotinamide (Niacinamide) to Control Skin Aging and Pigmentation. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cury-Martins, J.; Eris, A.P.M.; Abdalla, C.M.Z.; Silva, G.d.B.; Moura, V.P.T.d.; Sanches, J.A. Management of Dermatologic Adverse Events from Cancer Therapies: Recommendations of an Expert Panel. Bras. Dermatol. 2020, 95, 221–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Fu, R.; Jiang, T.; Duan, D.; Wu, Y.; Li, C.; Li, Z.; Ni, R.; Li, L.; Liu, Y. Mechanism of Lethal Skin Toxicities Induced by Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Inhibitors and Related Treatment Strategies. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 804212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulawik-pióro, A.; Goździcka, W.J. Plant and Herbal Extracts as Ingredients of Topical Agents in the Prevention and Treatment Radiodermatitis: A Systematic Literature Review. Cosmetics 2022, 9, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiroz Schmidt, F.M.; Serna González, C.V.; Mattar, R.C.; Lopes, L.B.; Santos, M.F.; Santos, V.L.C.d.G. Topical Application of a Cream Containing Nanoparticles with Vitamin E for Radiodermatitis Prevention in Women with Breast Cancer: A Randomized, Triple-Blind, Controlled Pilot Trial. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2022, 61, 102230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igielska-Kalwat, J.; Połoczańska-Godek, S.; Murawa, D.; Poźniak-Balicka, R.; Wachowiak, M.; Demski, G.; Cieśla, S. The Effect of the RadioProtect Cosmetic Formulation on the Skin of Oncological Patients Treated with Selected Cytostatic Drugs and Ionizing Radiation. Postep. Dermatol. Alergol. 2022, 39, 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacovelli, N.A.; Torrente, Y.; Ciuffreda, A.; Guardamagna, V.A.; Gentili, M.; Giacomelli, L.; Sacerdote, P. Topical Treatment of Radiation-Induced Dermatitis: Current Issues and Potential Solutions. Drugs Context 2020, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golubnitschaja, O.; Kapinova, A.; Sargheini, N.; Bojkova, B.; Kapalla, M.; Heinrich, L.; Gkika, E.; Kubatka, P. Mini-Encyclopedia of Mitochondria-Relevant Nutraceuticals Protecting Health in Primary and Secondary Care—Clinically Relevant 3PM Innovation. EPMA J. 2024, 15, 163–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waszkielewicz, A.M.; Mirosław, K. Peptides and Their Mechanisms of Action in the Skin. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 11495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogórek, K.; Nowak, K.; Wadych, E.; Ruzik, L.; Timerbaev, A.R.; Matczuk, M. Are We Ready to Measure Skin Permeation of Modern Antiaging GHK–Cu Tripeptide Encapsulated in Liposomes? Molecules 2025, 30, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortazavi, S.M.; Vadoud, S.A.M.; Moghimi, H.R. Topically Applied GHK as an Anti-Wrinkle Peptide: Advantages, Problems and Prospective. BioImpacts 2025, 15, 30071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dymek, M.; Olechowska, K.; Hąc-Wydro, K.; Sikora, E. Liposomes as Carriers of GHK-Cu Tripeptide for Cosmetic Application. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]