Abstract

Alopecia is a multifactorial disorder in which immune, endocrine, metabolic, and microbial systems converge within the follicular microenvironment. In alopecia areata (AA), loss of immune privilege, together with interferon-γ- and interleukin-15-driven activation of the JAK/STAT cascade, promotes cytotoxic infiltration, whereas selective inhibitors, including baricitinib, ritlecitinib, and durvalumab, restore immune balance and permit anagen reentry. In androgenetic alopecia (AGA), excess dihydrotestosterone and androgen receptor signaling increase DKK1 and prostaglandin D2, suppress Wnt and β-catenin activity, and drive follicular miniaturization. Combination approaches utilizing low-dose oral minoxidil, platelet-rich plasma, exosome formulations, and low-level light therapy enhance vascularization, improve mitochondrial function, and reactivate metabolism, collectively supporting sustained regrowth. Elucidation of intracellular axes such as JAK/STAT, Wnt/BMP, AMPK/mTOR, and mitochondrial redox regulation provides a mechanistic basis for rational, multimodal intervention. Advances in stem cell organoids, biomaterial scaffolds, and exosome-based therapeutics extend treatment from suppression toward structural follicle reconstruction. Recognition of microbiome and mitochondria crosstalk underscores the need to maintain microbial homeostasis and redox stability for durable regeneration. This review synthesizes molecular and preclinical advances in AA and AGA, outlining intersecting signaling networks and regenerative interfaces that define a framework for precision and sustained follicular regeneration.

1. Introduction

Hair loss (alopecia) is increasingly recognized not only as a cosmetic issue but as a systemic disorder arising from immune, endocrine, metabolic, and microbial disequilibrium [1]. Advances in molecular biology and dermatogenomics have established the hair follicle as a dynamic mini-organ that integrates immune privilege, hormonal regulation, and cellular bioenergetics [2]. Alopecia areata (AA) and androgenetic alopecia (AGA) remain the two dominant forms, serving as archetypes for autoimmune- and androgen-dependent diseases, respectively [3,4,5]. In AA, the breakdown of follicular immune privilege results from interferon-γ-driven activation of the JAK-STAT signaling pathway, leading to the upregulation of CXCL9/10/11 chemokines and the infiltration of autoreactive CD8+NKG2D+ cytotoxic T cells [6,7]. The resulting immune assault compromises matrix proliferation; however, the bulge stem-cell compartment remains preserved, enabling potential recovery when immune homeostasis is restored [8]. In contrast, AGA arises from androgen-mediated miniaturization of terminal hair follicles into vellus-like structures, driven by excessive dihydrotestosterone (DHT)-androgen receptor (AR) signaling within dermal papilla cells [9]. This activation induces the expression of transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) and dickkopf Wnt signaling pathway inhibitor 1 (DKK1), suppressing the regenerative Wnt/β-catenin pathway and promoting premature catagen transition [10]. Mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and metabolic inflexibility further exacerbate these processes by disturbing ATP synthesis and redox balance [11].

Recent evidence characterizes alopecia as a condition driven by intersecting immune, endocrine, metabolic, and microbial disturbances rather than by a single pathogenic pathway [12,13]. Multi-omics analyses indicate that alterations in glycolysis, lipid metabolism, and redox balance can modulate follicular vulnerability across different alopecia subtypes [14,15]. Shifts in the scalp microbiome may further modulate perifollicular inflammation and lipid turnover, with early studies suggesting that microbiome-targeted approaches could help stabilize the local scalp environment [16,17,18]. Overall, alopecia reflects the convergence of multiple biological signals within the follicular niche. Building on this framework, Table 1 summarizes the major clinical types of hair loss and the principal treatment strategies commonly applied to each category, providing a practical reference for understanding how distinct pathogenic processes guide therapeutic selection.

Table 1.

Types of Hair Loss and Major Treatment Methods.

In addition to etiologic and mechanistic classifications, currently available pharmacologic interventions remain limited. Only a small number of agents have received formal U.S. FDA approval for the treatment of alopecia, reflecting the complexity of translating mechanistic understanding into effective therapy. These include topical minoxidil and oral finasteride as the two principal standards for androgenetic alopecia, with their pharmacodynamic targets primarily centered on follicular potassium channels and androgen metabolism, respectively. Table 2 presents a concise overview of FDA-approved drugs for hair loss, along with their typical administration routes and common adverse effects, providing a regulatory and clinical framework for subsequent discussion of emerging therapeutics. Collectively, these approved agents underscore the gap between symptomatic management and proper follicular regeneration, highlighting the ongoing need for next-generation strategies that integrate molecular precision with long-term safety and efficacy.

Table 2.

FDA-Approved Drugs Against Hair Loss and Their Common Side Effects.

2. Alopecia Areata (AA)

2.1. Pathobiology and Therapeutic Rationale

Alopecia areata (AA) is a chronic, relapsing, and organ-specific autoimmune disorder characterized by sudden, non-scarring hair loss, where autoreactive cytotoxic lymphocytes selectively attack anagen-phase hair follicles [51]. The disorder exemplifies an intersection between immune dysregulation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and epithelial-immune crosstalk. In healthy individuals, the hair follicle maintains “immune privilege” through multiple tolerance mechanisms, including downregulation of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules, secretion of immunosuppressive cytokines such as TGF-β and α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone (α-MSH), and local production of kynurenine via indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO). These features collectively shield the follicular antigens from immune recognition, thereby preventing autoimmune activation. The collapse of this immune privilege constitutes a primary pathological event in AA. Under stress or in response to interferon-γ (IFN-γ) produced by natural killer (NK) cells and T helper 1 (Th1) lymphocytes, MHC class I and II expression on follicular keratinocytes and dermal papilla cells is upregulated [52,53]. This upregulation enables presentation of follicular antigens, which trigger cytotoxic responses from CD8+NKG2D+ T cells and NK cells. Concurrent secretion of chemokines such as CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11 further recruits additional effector cells into the perifollicular environment, forming a persistent inflammatory loop [54,55].

Within this microenvironment, interleukin-15 (IL-15) signaling maintains T-cell activation through the Janus kinase (JAK) 1/3 and Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription (STAT) 5 pathway, thereby linking local inflammation with systemic immune reactivity. The resulting infiltration of CD8+NKG2D+ T cells not only damages the hair matrix cells but also amplifies keratinocyte apoptosis and oxidative stress, establishing a chronic inflammatory milieu. Notably, the bulge region, which contains hair follicle stem cells (HFSCs), remains unaffected, potentially enabling regeneration if the immune balance can be restored.

Recent multi-omics analyses, including single-cell RNA sequencing and spatial metabolomics, have revealed that AA lesions exhibit distinct metabolic reprogramming, characterized by elevated glycolysis, suppressed fatty acid β-oxidation, and disrupted mitochondrial respiration [56,57,58]. This metabolic shift supports continuous T-cell activation and cytokine production, indicating that energy metabolism directly influences immune persistence. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation exacerbates tissue damage, while impaired NAD+/SIRT1 signaling reduces mitochondrial resilience, further perpetuating the autoimmune cycle.

Epigenetic regulation has also emerged as a determinant of chronic disease chronicity. Aberrant DNA methylation in immune-regulatory genes, such as IL2RA, PTPN22, and HLA-DRB1, correlates with prolonged disease activity and a reduced likelihood of spontaneous remission. Additionally, histone acetylation imbalance and altered microRNA expression (e.g., miR-155, miR-211, miR-125b) influence T-cell polarization and cytokine production. Single-cell transcriptomic studies have identified subsets of perifollicular T cells that co-express exhaustion markers (PD-1, TIM-3) alongside pro-inflammatory cytokines, implying a paradoxical state of “chronic activation despite exhaustion” [55]. Collectively, AA represents a dynamic model of immune/metabolic/epigenetic interplay, wherein immune privilege collapse, bioenergetic imbalance, and transcriptional reprogramming coalesce to produce a recurrent autoimmune phenotype.

2.2. JAK Inhibitors and Emerging Therapeutics

The JAK-STAT pathway serves as a key regulator of IFN-γ and IL-15 signaling in alopecia areata (AA) [59,60], driving a self-reinforcing inflammatory cycle by activating JAK1/2/3 in follicular keratinocytes and infiltrating lymphocytes. Targeted inhibition of this axis interrupts upstream cytokine amplification and prevents sustained cytotoxic recruitment.

Baricitinib, a selective JAK1/2 inhibitor, reduces STAT1/3 phosphorylation and downstream chemokines (CXCL9/10/11). In BRAVE-AA1/AA2 (n = 1200; 36 weeks), 30–40% achieved SALT75 with improved density and psychosocial well-being. Extension data demonstrate maintained efficacy through 104 weeks with mostly mild adverse events such as nasopharyngitis and headache [61,62,63,64]. Ritlecitinib (JAK3/TEC inhibitor) selectively modulates γ-chain cytokines, reducing CD8+NKG2D+ cytotoxicity while sparing regulatory T cell (Treg) integrity. In the ALLEGRO phase 3 study (n = 718; 24 weeks), SALT75 responses ranged from 29% to 41% [65,66,67]. Deuruxolitinib, another potent JAK1/2 inhibitor, sustained durable regrowth in CTP-543 (n = 1157; 48 weeks) with ~38% SALT75 and mostly mild AEs [68,69]. Continuous therapy maintained remission, whereas withdrawal frequently resulted in relapse, indicating incomplete restoration of immune homeostasis. Recent extension studies confirm durable benefit with ongoing treatment. Baricitinib maintains efficacy for up to 104 weeks [62,63], ritlecitinib shows sustained responses for 24 months [65,66], and deuruxolitinib preserves 48-week outcomes [64,68].

Next-generation JAK inhibitors aim to improve selectivity and long-term tolerability. Tyrosine kinase (TYK) 2 inhibitors, such as deucravacitinib, modulate the pseudokinase domain and selectively inhibit the IL-12, IL-23, and type I interferon pathways while preserving JAK1/2-related hematopoietic signaling. These agents show early promise in autoimmune dermatoses and may offer a safer immunologic rebalancing strategy for alopecia areata (AA). Beyond cytokine suppression, mitochondrial supportive compounds, including CoQ10 and the mitochondria-targeted analog MitoQ, enhance oxidative phosphorylation and reduce ROS-induced apoptosis in follicular cells [70,71,72,73].

Although synergistic activity with JAK inhibitors has not been established, these antioxidants help stabilize the redox and metabolic environments necessary for immune tolerance and follicular repair. Vitamin D analogs also promote Treg-supportive VDR signaling. Advances in drug delivery have expanded the therapeutic potential of JAK inhibition. Nano-emulsified and liposomal formulations of baricitinib and ritlecitinib show improved dermal penetration and follicular localization in ex vivo human and porcine skin models [74,75].

Human scalp pharmacokinetic data remain limited, but targeted nano-delivery may reduce systemic exposure while prolonging follicular residence time. Although baricitinib, ritlecitinib, and deuruxolitinib show favorable short-term tolerability, emerging evidence indicates that prolonged JAK inhibition can increase susceptibility to opportunistic infections, including varicella-zoster reactivation, and may elevate thromboembolic risk, with rare malignancies reported in autoimmune populations [69,76]. These observations emphasize the need for careful patient selection and routine monitoring during long-term therapy.

The expanding therapeutic landscape of AA is summarized in Table 3, which organizes emerging agents by molecular targets, mechanisms, and developmental stages. In addition to approved JAK inhibitors, the pipeline includes TYK2 inhibitors and mitochondrial-protective compounds such as CoQ10 and MitoQ, reflecting a shift toward integrated immune-metabolic modulation.

Increasing evidence links immune-driven cytokine activation with mitochondrial dysfunction. Persistent JAK/STAT and NF-κB signaling elevates mitochondrial ROS, disrupts ATP and redox balance, and activates mtDNA-NLRP3 inflammatory loops [77,78]. In summary, strategies that support mitochondrial function may contribute to the metabolic conditions favorable for follicular recovery. Nevertheless, because current evidence is mainly derived from preclinical studies and long-term clinical data remain scarce, further systematic investigation will be essential to determine their durability, clinical significance, and potential role in future therapeutic frameworks.

Table 3.

Therapeutic Pipeline for Alopecia Areata (AA).

Table 3.

Therapeutic Pipeline for Alopecia Areata (AA).

| Agent | Primary Target | Mechanism of Action | Development Stage | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baricitinib | JAK1/2 | IFN-γ-STAT1 inhibition | Approved | [61,62,63] |

| Ritlecitinib | JAK3/TEC | IL-15 blockade | Approved | [65,66] |

| Deuruxolitinib | JAK1/2 | Immune homeostasis restoration | Phase III | [68,69] |

| TYK2 inhibitors | TYK2 | IL-12/23, IFN-α modulation | Phase II | [79] |

| CoQ10 *, MitoQ ** | Mitochondria | Antioxidant, redox support | Preclinical | [70,71,72,73] |

* CoQ10: Coenzyme Q10. ** MitoQ: Mitoquinone mesylate (synthetic analog of coenzyme Q10).

2.3. Other Immunomodulators and Adjunct Strategies

Beyond JAK inhibitors, multiple immunomodulatory and regenerative approaches are being explored to re-establish follicular immune tolerance and stabilize the metabolic environment in alopecia areata (AA). These strategies target cytokine imbalance, oxidative stress, and microenvironmental disruption, reflecting a shift toward more selective immune recalibration. Phosphodiesterase-4 (PDE4) inhibitors such as apremilast increase intracellular cAMP and suppress IL-2, IL-17, TNF-α, and IFN-γ while enhancing IL-10 [80]. This anti-inflammatory profile reduces perifollicular activation, and small studies suggest partial regrowth with good tolerability, indicating a possible complementary role in immune-driven scalp disorders, including AA.

Biologic agents that modulate type-2 cytokines also show potential. Dupilumab, which blocks IL-4/IL-13 signaling through IL-4Rα, has improved hair density and perifollicular inflammation in AA patients with atopic features [81,82,83]. Early evaluations of IL-13-targeting antibodies such as tralokinumab and lebrikizumab support the concept that selective Th2 modulation may benefit specific AA subgroups [84,85].

Mitochondria-targeted antioxidants, including NAC and melatonin, help restore redox balance and protect follicular cells from ROS-mediated injury [86]. These compounds mitigate mitochondrial stress, a factor increasingly recognized as contributing to AA pathophysiology. Advances in biomaterials have introduced localized delivery platforms. Hyaluronic acid (HA) hydrogels allow for sustained release of JAK inhibitors, antioxidants, or cytokine blockers and can be combined with nanoparticles to enhance tissue retention and controlled release [87,88].

Overall, these emerging modalities demonstrate a shift toward multi-layered restoration of follicular homeostasis. Their integration with JAK inhibition or regenerative therapies may support more consistent disease control and improve the resilience of hair cycling.

3. Androgenetic Alopecia (AGA)

3.1. Pathobiology and Core Therapeutics

Androgenetic alopecia (AGA) is a gradually progressive, androgen-dependent disorder characterized by miniaturization of scalp hair follicles from thick terminal hairs into delicate, vellus-like structures [19]. Its pathogenesis reflects the interplay of genetic predisposition and systemic endocrine signaling. Dermal papilla cells (DPCs) residing at the base of affected follicles become hypersensitive to dihydrotestosterone (DHT), the more active derivative of testosterone, which is generated by 5α-reductase types I and II [89,90]. Upon binding to the androgen receptor (AR) within DPCs, DHT triggers a downstream transcriptional cascade that suppresses Wnt/β-catenin signaling while simultaneously inducing the expression of catagen-promoting mediators such as TGF-β1, DKK1, and prostaglandin D2 (PGD2) [91,92,93,94,95].

This androgenic signaling shortens the anagen phase by promoting the apoptosis of hair-matrix keratinocytes and diminishing the paracrine trophic support provided by dermal papilla cells (DPCs) [96,97]. Concurrently, elevated oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and increased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, particularly IL-6 and TNF-α, accelerate follicular catagen transition and structural degeneration [98]. Recent integrative transcriptomic and metabolic analyses of DPCs from individuals with androgenetic alopecia (AGA) have revealed a rigid bioenergetic phenotype characterized by reduced glycolytic activity, impaired mitochondrial respiration, and downregulation of metabolic regulatory genes. These findings indicate that chronic androgen exposure metabolically reprograms DPCs into a less adaptable, energy-deprived state, thereby undermining their ability to sustain follicular growth and regeneration [99,100].

From a genetic viewpoint, polymorphisms in AR, SRD5A2, and EDA2R loci have emerged as prominent susceptibility markers in male AGA [101,102]. Notably, single-nucleotide variants (SNPs) in SRD5A2, such as rs523349 (V89L), modulate 5α-reductase enzyme activity and correlate with AGA severity [103]. In women, genetic variations in CYP19A1 (which encodes aromatase) and ESR2 (estrogen receptor β) influence local androgen-to-estrogen conversion, thereby fine-tuning AR sensitivity and contributing to sex-specific phenotypes [104].

Therapeutically, 5α-reductase inhibitors, such as finasteride and dutasteride, remain foundational in the management of male AGA, capable of reducing scalp DHT levels by 60–90% in many subjects [105,106]. Finasteride selectively inhibits the type II isozyme predominant in hair follicles, whereas dutasteride targets both types I and II, offering more potent androgen suppression in recalcitrant cases [107,108]. To avoid systemic side effects, topical finasteride formulations have been increasingly adopted, as they deliver localized DHT inhibition with minimal systemic absorption [109,110].

3.2. Adjuncts, Devices, and Female Pattern Considerations

Although 5α-reductase inhibitors and topical minoxidil form the therapeutic backbone for androgenetic alopecia (AGA), real-world outcomes are frequently incomplete. Inter-individual variability in response, plateau effects after initial gains, and tolerability concerns (e.g., sexual adverse events with systemic antiandrogens or local irritation with topical agents) erode long-term adherence. These limitations have catalyzed a shift toward layered, mechanism-complementary approaches that reinforce follicular support while mitigating pharmacologic shortfalls.

Within this paradigm, low-dose oral minoxidil (LDOM), typically administered at 0.25–2.5 mg daily, has emerged as a pragmatic adjunct. By opening ATP-sensitive potassium channels (KATP channels) in vascular smooth muscle, minoxidil reduces arteriolar resistance. It improves scalp microperfusion, thereby enhancing oxygen and nutrient delivery to the follicular niche. In dermal papilla cells (DPCs), minoxidil upregulates pro-angiogenic programs (e.g., VEGF), which in turn promote perifollicular capillary remodeling, support matrix keratinocyte viability, and bias cycling toward anagen retention. Across controlled cohorts, LDOM has translated these microenvironmental gains into ~20–30% increases in hair density at 6–12 months, with dose-dependent, generally mild hypertrichosis as the most frequent trade-off. Notably, oral delivery can overcome the penetration ceiling inherent to topical formulations, widening the responder pool in both men and women [111,112,113,114].

Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) extends this vascular-trophic logic with a biologic stimulus [115]. Autologous concentrates enriched in PDGF, IGF-1, EGF, and allied mediators amplify stem/progenitor-cell activity, tune extracellular-matrix turnover, and promote angiogenesis around miniaturizing follicles [116]. Meta-analytic evidence indicates consistent gains in terminal hair counts versus placebo, whether PRP is used alone or layered onto standard care, with a favorable tolerability profile [117]. Mechanistically, PRP engages canonical growth pathways in DPCs and the outer root sheath (ORS) compartments, supplying regenerative cues that are often blunted in AGA despite adequate antiandrogen exposure [118]. Refinements in extracellular-vesicle therapeutics have further focused attention on PRP-derived exosomes (PRP-Exos). These nanoscale vesicles package miRNAs and proteins that activate Wnt/β-catenin signaling (e.g., upregulating β-catenin/LEF-1 while relieving SFRP1-mediated antagonism), thereby promoting follicular elongation and sustaining anagen in organ culture and in vivo models [119,120]. Compared to bulk PRP, exosomes offer batch-to-batch compositional stability and potentially more targeted delivery, positioning them as a next-generation therapy. These cell-free biotherapeutics can be combined with systemic or device-based regimens [121,122].

Low-level light therapy (LLLT), typically employing red wavelengths of ~630–680 nm, complements pharmacological and biological inputs by modulating mitochondrial function [123]. Photonic activation of cytochrome c oxidase improves electron-transport efficiency, increases ATP availability, and tempers oxidative stress within follicular cells, conditions conducive to anagen persistence and recovery from catagenic pressure [124]. Placebo-controlled trials with FDA-cleared home devices demonstrate statistically reliable increments in terminal hair counts, and preplanned combinations with minoxidil or PRP show additive-to-synergistic regrowth, consistent with orthogonal mechanisms converging on follicular energy balance and microvascular support [125,126,127].

In female pattern hair loss (FPHL), where systemic androgens may be normal yet local androgen signaling remains pathogenic, hormonal modulation is frequently required. Agents such as spironolactone and flutamide attenuate androgen-receptor activity and sebaceous-androgen tone, while topical estrogens or selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) can re-tilt the estrogen/DHT milieu toward cyclical stability [128,129]. In practice, women with recalcitrant disease often benefit from integrated regimens that layer LDOM, PRP, and LLLT atop hormonal modulation, leveraging complementary pathways (vascular, metabolic, inflammatory, and endocrine) to overcome the ceiling effects of monotherapy [130,131].

Finally, innovative molecular strategies are redefining antiandrogen precision at the follicular level. Androgen receptor-targeting small interfering RNA (SAMiRNA) micelles, designed against AR mRNA, selectively downregulate receptor synthesis within hair-bearing skin, thereby preserving local efficacy while minimizing systemic exposure [132]. In parallel, AR proteolysis-targeting chimera (PROTAC-AR) degraders utilize the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway to eliminate the androgen receptor (AR) protein, potentially dissociating therapeutic efficacy from dose-limiting off-target toxicity [133,134]. Although these modalities remain in the investigational stage, they exemplify a broader transition toward targeted, combination-ready interventions that can be rationally integrated with LDOM, PRP/PRP-Exos, and LLLT to achieve more profound and durable clinical responses.

Building upon these innovations, Table 4 provides an integrated overview of current and emerging therapeutic modalities for AGA, organized by agent or method, primary target, mechanism of action, and clinical stage. This summary encompasses both pharmacological standards, such as finasteride and dutasteride, which inhibit type I/II 5α-reductase and lower scalp DHT, as well as complementary approaches, including LDOM, PRP, and LLLT, that act through vascular, mitochondrial, and regenerative mechanisms. In female-pattern AGA, spironolactone and flutamide further expand the therapeutic spectrum by restoring endocrine balance by modulating the androgen receptor. In summary, contemporary AGA care is shifting from single-axis androgen suppression toward a multimodal approach to restore the follicular ecosystem, integrating vascular augmentation, mitochondrial support, regenerative signaling, and context-specific endocrine control. This paradigm not only clarifies why many patients plateau on legacy agents but also establishes a scalable framework for incorporating next-generation molecular tools, including SAMiRNA, PROTAC-AR degraders, and emerging bioenergetic modulators, as the evidence base continues to mature.

Table 4.

Current Therapeutic Options for Androgenetic Alopecia (AGA).

4. Molecular and Cellular Signaling Framework in Alopecia

4.1. Immune-Inflammatory Circuitry in Alopecia Areata (AA)

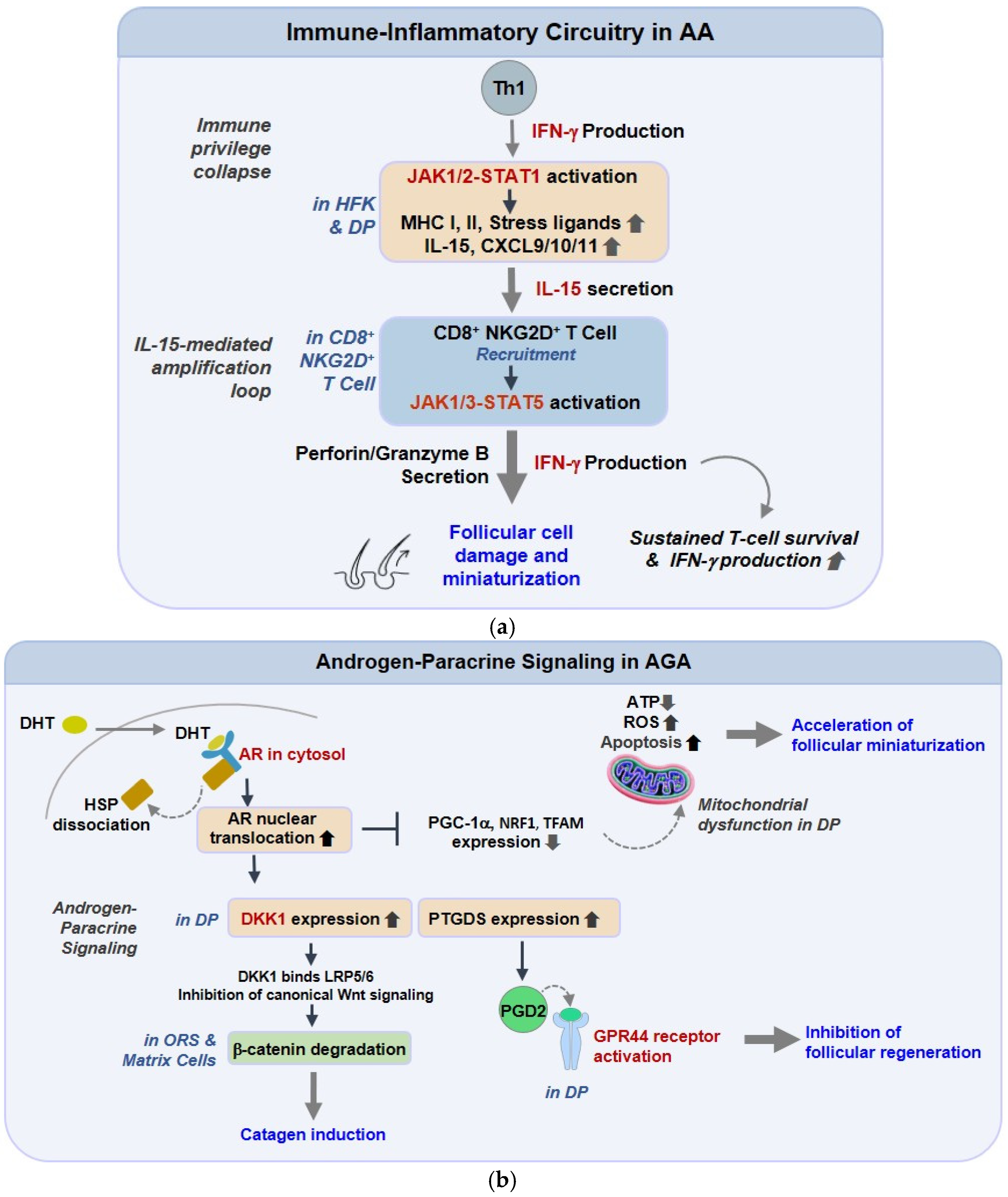

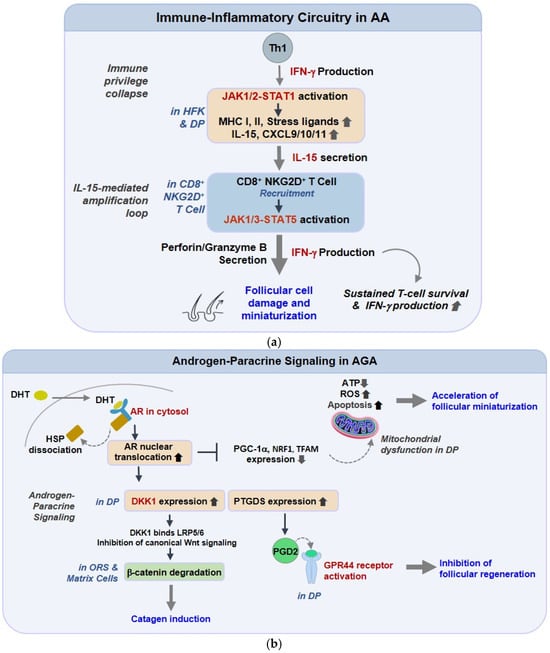

In AA, a compact but persistent cytokine loop turns transient danger signaling into chronic perifollicular immunity [135]. Interferon-γ (IFN-γ) licenses follicular epithelium and dermal papilla (DP) to express IL-15 and CXCR3 ligands (CXCL9/10/11), which, in turn, attract and maintain cytotoxic CD8+NKG2D+ T cells around anagen bulbs [136]. The same IFN-γ pressure upshifts MHC class I/II and stress ligands, dismantling hair-follicle immune privilege and enabling antigen display where it is usually muted. Functionally, IL-15-JAK1/3-STAT5 keeps resident memory T cells metabolically “on,” while IFN-γ-STAT1 reinforces chemokine transcription; the two arms create a feed-forward circuit that explains relapse after drug withdrawal [137]. Mechanism-directed interruption with JAK blockade reduces STAT phosphorylation, chemokine output, and lymphocyte ingress, and single-cell datasets now support a causal role for clonally expanded CD8+ cells in active lesions, rather than a secondary presence [138,139]. Oxidative stress and inflammasome priming further lower the threshold for this loop by enhancing danger signals and antigenicity, suggesting the need for layered immunologic and metabolic strategies in chronic disease. Collectively, these findings delineate a self-reinforcing immunologic circuit in which IFN-γ and IL-15 signaling sustain a cytotoxic niche around anagen follicles. As illustrated in Figure 1a, the overall framework of this immune-inflammatory network depicts how Th1-derived IFN-γ activates the JAK1/2-STAT1 pathways in hair-follicle keratinocytes (HFKs) and dermal papilla (DP) cells, inducing the expression of MHC class I/II, stress ligands, IL-15, and CXCL9/10/11 chemokines. These mediators recruit and energize CD8+NKG2D+ T cells, which, through the release of IFN-γ and cytolytic granules, perpetuate epithelial injury. The persistent IFN-γ-IL-15 feedback ultimately abolishes follicular immune privilege, driving apoptotic regression of the hair bulb and establishing the immunopathologic basis of alopecia areata.

Figure 1.

Immune-Inflammatory and Androgen-Paracrine Pathways Underlying Alopecia Signaling Pathways. (a) Immune-inflammatory circuitry in alopecia areata (AA). In AA, IFN-γ released by Th1 cells activates JAK1/2-STAT1 signaling in hair follicle keratinocytes and dermal papilla cells, inducing MHC class I/II, IL-15, and chemokines (CXCL9/10/11). These factors recruit cytotoxic CD8+NKG2D+ T cells, reinforcing the IFN-γ-IL-15 loop, disrupting immune privilege, and promoting epithelial apoptosis and follicular miniaturization. (b) Androgen-paracrine and metabolic signaling in androgenetic alopecia (AGA). In AGA, DHT-activated AR upregulates DKK1, suppressing Wnt/β-catenin signaling, and increases PGD2 via PTGDS, which limits follicular regeneration through GPR44/CRTH2. DHT-AR signaling also downregulates mitochondrial biogenesis regulators (PGC-1α, NRF1, TFAM), reducing ATP production and enhancing oxidative stress-driven regression.

4.2. Androgen-Paracrine Signaling in Androgenetic Alopecia (AGA)

AGA is driven less by circulating androgens than by local AR-dependent paracrine brakes that bias follicles toward regression. In DP cells, dihydrotestosterone (DHT) rapidly induces DKK1, a potent antagonist of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. The loss of Wnt tone removes survival cues from the outer root sheath (ORS) and matrix compartments, thereby accelerating catagen entry [140,141,142]. In parallel, PGD2 and its synthase, PTGDS, accumulate in the balding scalp, signaling through GPR44, which directly suppresses elongation and regeneration, including after wounding [143]. These brakes explain miniaturization even with “normal” systemic androgens. Mitochondrial profiling of balding DP reveals reduced respiratory flexibility and stress-susceptible bioenergetics, providing fertile ground for DKK1/PGD2 to tip the apoptosis-survival balance [144]. Conceptually, an AR-paracrine-mitochondrial triad converts hormonal cues into durable structural change, and each node is druggable (AR modulation, anti-DKK1/anti-GPR44 concepts, mitochondrial stabilizers). As summarized in Figure 1b, this schematic integrates the key elements of androgen-paracrine signaling in androgenetic alopecia. DHT binds to the androgen receptor (AR), leading to nuclear activation of DKK1 and PTGDS, which respectively inhibit Wnt/β-catenin-driven stem-cell renewal and stimulate PGD2-mediated suppression of follicular growth through GPR44/CRTH2. In parallel, DHT-AR signaling attenuates mitochondrial biogenesis regulators, lowering ATP production and increasing oxidative stress. Collectively, these converging mechanisms translate androgen sensitivity into progressive follicular miniaturization.

4.3. Regenerative Gateways: Wnt/BMP and β-Catenin Control

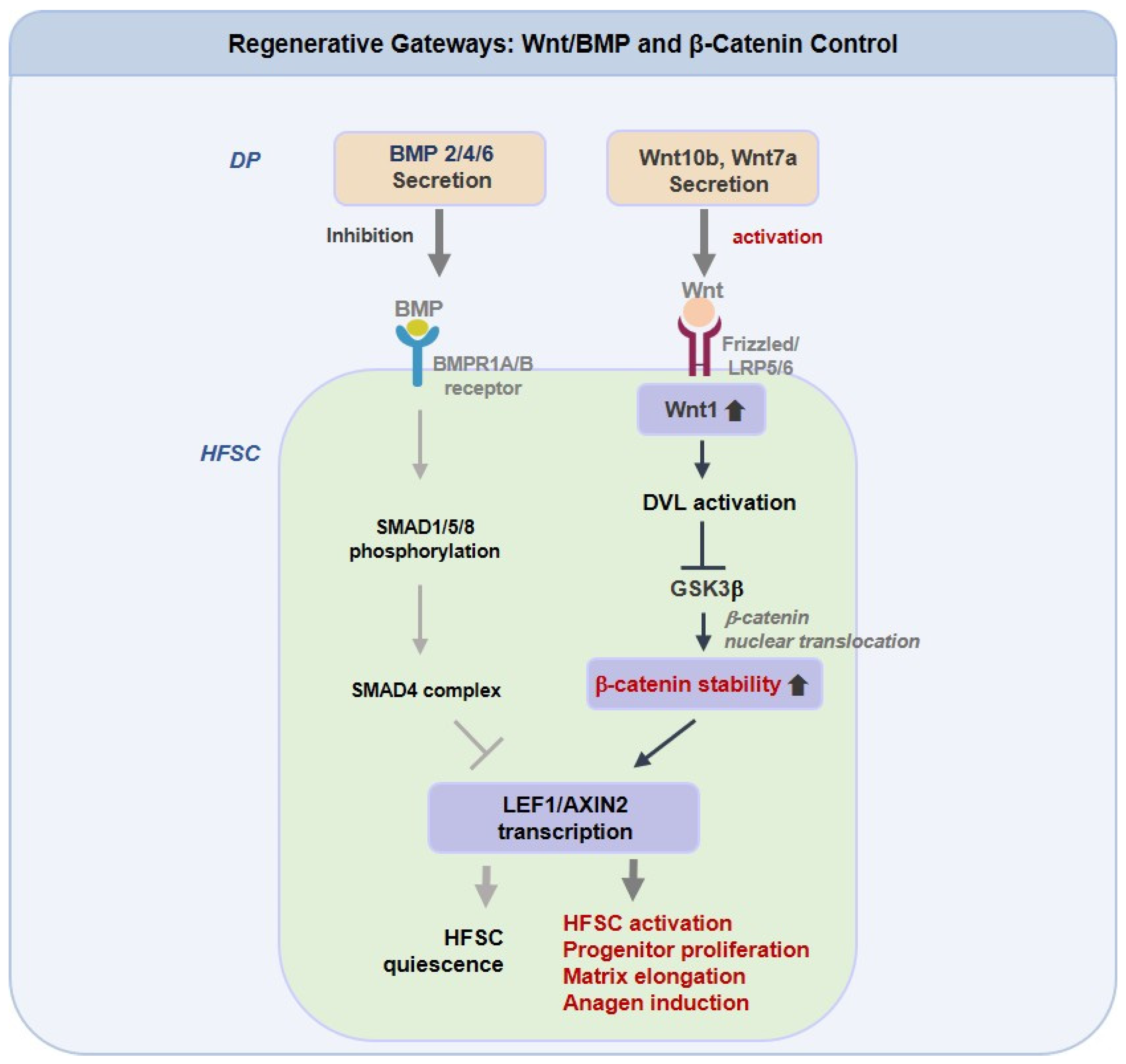

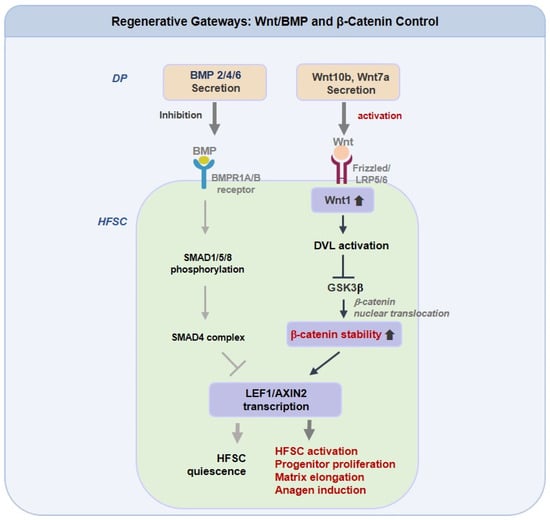

Anagen induction functions as a regulatory checkpoint. Canonical Wnt inputs, such as Wnt10b and Wnt7a, must first prevent β-catenin degradation to initiate the LEF1 and AXIN2 programs, but only when BMP constraints are sufficiently lifted [145,146]. The relative balance between Wnt activation and BMP suppression, rather than absolute Wnt levels, determines whether HFSCs commit to growth. Evidence ranges from GSK3β inhibition by valproate, which enhances human follicle elongation, to context-sensitive activators such as KY19382 that restore regrowth and wound-induced neogenesis under metabolic stress [147]. Recent findings also connect innate sensors such as TLR2 and mechanical tension to Wnt and BMP cross-modulation, indicating that niche environmental conditions shape drug responsiveness [148,149]. Therapeutic combinations that enhance Wnt signaling, together with redox support or biomaterial-based delivery, may provide longer anagen maintenance in stressed scalps compared with single-pathway approaches.

As illustrated in Figure 2, which presents an integrated schematic of Regenerative Gateways: Wnt, BMP, and β-Catenin Control, the figure summarizes the coordinated molecular signaling that governs HFSCs activation and regeneration through the interplay of Wnt, BMP, and β-catenin pathways. Dermal papilla-derived Wnt10b and Wnt7a activate the canonical Wnt and β-catenin cascade through Frizzled, LRP5/6, DVL, and GSK3β signaling, leading to β-catenin retention and transcriptional activation of LEF1 and AXIN2. This process promotes HFSCs activation, progenitor cell expansion, and anagen entry. In contrast, BMP2, BMP4, and BMP6 stimulate BMPR1A and BMPR1B, and the SMAD1, SMAD5, SMAD8, and SMAD4 complex, to counteract Wnt-dependent β-catenin activity, maintaining HFSC quiescence and limiting follicular regeneration. The dynamic equilibrium between these opposing signaling axes thus governs the regenerative balance of the follicular niche.

Figure 2.

Regenerative Gateways: Wnt/BMP and β-Catenin Control in Hair Follicle Stem Cells. Dermal papilla (DP)-derived Wnt10b and Wnt7a activate the canonical Wnt/β-catenin pathway in hair follicle stem cells (HFSCs) via Frizzled/LRP5/6-DVL-GSK3β signaling, leading to β-catenin stabilization and transcriptional activation of LEF1 and AXIN2. This cascade promotes HFSCs activation, progenitor proliferation, and anagen induction. Conversely, BMP2/4/6 signaling through BMPR1A/B and SMAD1/5/8-SMAD4 complex suppresses Wnt-driven β-catenin activity, maintaining HFSCs quiescence and restraining follicular regeneration.

4.4. Mitochondrial-Redox and Stress Integration

Hair-follicle fate maps cleanly onto mitochondrial competency [78]. PGC-1α/SIRT1 programs maintain ETC efficiency, limit ROS spillover, and sustain HFSC clonogenicity [150,151]. When this circuitry fails due to aging, androgen by-products, or systemic metabolic load, ROS-NF-κB signaling licenses chemokine and adhesion modules that degrade the niche and shorten anagen [152,153,154]. In AGA, DP cells exhibit rigid bioenergetics (low spare respiratory capacity, impaired maximal respiration); in AA, persistent T-cell cytokines create a redox environment that maintains high antigen presentation. These observations elevate mitochondria to a convergence node connecting immune tone with regenerative capacity. Accordingly, mitochondria-directed adjuvants (e.g., CoQ10/MitoQ, NAD+/SIRT1 activators, autophagy enhancers) are rational partners for JAK inhibitors or anti-androgens, buffering oxidative load while upstream inflammation is controlled [155,156].

4.5. Nutrient-Sensing and Growth Control: AMPK-mTOR Crosstalk

The activation state of HFSCs is influenced by nutrient-sensing pathways centered on AMPK and mTOR, which balance energy preservation with regenerative readiness [157]. AMPK acts as a stress-responsive checkpoint, promoting autophagy and mitochondrial maintenance, thereby helping HFSCs retain quiescence and recover after metabolic stress. In contrast, excessive mTORC1 activity drives anabolic programs that impair stem cell stability and reduce responsiveness to regenerative cues, such as Wnt signals [158]. Recent human follicle and organoid studies show that heightened mTORC1 signaling restricts follicle growth and disrupts melanogenic pathways, linking metabolic imbalance to miniaturization and pigment loss. AMPK-related support of autophagy and mitochondrial quality contributes to redox stability and facilitates structural repair, although its effects on glycolysis vary depending on the cellular state [159,160,161]. Together, these findings suggest that modulating the AMPK-mTOR balance may enhance regenerative outcomes in alopecia by reinforcing metabolic resilience alongside cytokine- and Wnt-directed therapies.

4.6. Apoptotic and Survival Checkpoints

Miniaturization and early catagen entry arise when stress-induced apoptotic pathways outweigh survival signaling within the outer root sheath and progenitor compartments. Persistent inflammatory or androgenic stimuli amplify this shift by increasing dermal papilla-derived DKK1, which suppresses Wnt/β-catenin activity, and by elevating prostaglandin D2 (PGD2)-GPR44 signaling that promotes mitochondrial permeabilization and caspase activation. In contrast, Wnt/β-catenin and PI3K-AKT pathways maintain metabolic function and anti-apoptotic gene expression. Chronic exposure to DKK1 or cytokine signals progressively biases follicles toward regression. Therapies that reinforce Wnt or AKT signaling or improve redox balance, combined with inhibition of DKK1 or PGD2-GPR44, show beneficial effects in autoimmune and androgen-mediated alopecia models [162].

In summary, hair follicle homeostasis should be understood as an integrated regulatory network that unites immune, endocrine, and metabolic cues, rather than a single linear cascade. As organized in Table 5, the intracellular landscape of alopecia integrates cytokine-driven inflammation, androgen-regulated transcriptional responses, and energy-sensing metabolic checkpoints into a shared regulatory matrix that determines whether the follicle regenerates or regresses.

Table 5.

Key Cellular Signaling Framework in Alopecia.

5. Stem Cell and Regenerative Approaches

Regenerative dermatology has shifted alopecia treatment toward restoring a functional follicular niche rather than solely suppressing inflammatory or hormonal injury [166]. Hair follicle stem cells (HFSCs) integrity remains central to follicular cycling, and organoid systems have demonstrated partial ex vivo follicle reconstruction, though no organoid-based therapy has reached clinical validation [167,168,169,170,171]. MSC-derived exosomes act as cell-free modulators that enhance angiogenesis, support HFSC proliferation, and reduce perifollicular inflammation through microRNA and growth factor–mediated signaling. Early studies show improved hair density and anagen prolongation, mediated by activation of Wnt/β-catenin and PI3K-AKT pathways [172,173,174,175,176]. Biomaterial scaffolds, such as collagen- or HA-based matrices, provide structural support and promote HFSC adhesion by mimicking dermal biomechanical and biochemical properties [177,178]. Complementary technologies, including 3D bioprinting and follicle-on-a-chip systems, enable controlled follicular assembly and preclinical screening of regenerative compounds [179,180,181]. Integration of patient-derived HFSCs or induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived progenitors represents a potential route for personalized follicular reconstruction [182,183]. Collectively, these strategies outline the foundation of regenerative trichology, which seeks to rebuild a self-sustaining follicular ecosystem capable of long-term repair. Although these platforms remain preclinical, they provide essential tools for defining next-generation therapeutic approaches.

6. Microbiome-Linked Studies

The scalp microbiome has recently been recognized as a dynamic ecosystem that influences cutaneous immunity, sebaceous lipid metabolism, and barrier resilience, thereby shaping the local environment required for follicular homeostasis [184,185]. Next-generation sequencing analyses have revealed that dysbiosis, characterized by an overrepresentation of Cutibacterium acnes and a depletion of Staphylococcus epidermidis, correlates with perifollicular inflammation and lipid oxidation in both alopecia areata (AA) and androgenetic alopecia (AGA) [186]. Such compositional shifts increase reactive oxygen species and trigger innate immune signaling cascades, providing a metabolic-inflammatory bridge between microbiome imbalance and follicular degeneration.

Recent metabolomic and metagenomic investigations have further identified microbial-derived metabolites, such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), indole derivatives, and secondary bile acids, as bioactive mediators that maintain immune tolerance and epithelial energy balance through G-protein-coupled receptors and aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) signaling [187,188]. These findings indicate that the microbiome not only modulates immune tone but also participates in nutrient sensing and mitochondrial communication within follicular niches.

Therapeutically, restoration of scalp microbial homeostasis via probiotic-derived lysates or postbiotic peptides has shown measurable clinical benefits. Topical formulations containing Lactobacillus plantarum lysate or heat-killed Lacticaseibacillus paracasei have demonstrated improved follicular density, reduced sebum oxidation, and normalization of microbial diversity in pilot human trials [189]. Postbiotics derived from Saccharomyces and lipid-based consortia have also been reported to minimize scalp sensitivity and restore microbial balance without the need for antibiotic exposure [190]. Together, these insights underscore a metabolic-microbial axis in follicular biology, suggesting that coordinated modulation of the scalp microbiome, mitochondrial redox state, and local immune signaling could yield sustained regenerative outcomes in alopecic conditions.

7. Conclusions

Alopecia is increasingly recognized as a systems-level disorder in which immune, endocrine, metabolic, and microbial networks intersect within a shared follicular ecosystem. Across alopecia areata (AA) and androgenetic alopecia (AGA), emerging research reframes disease not as a single-axis defect but as a loss of coordinated immune privilege, bioenergetic resilience, and epithelial and mesenchymal communication. Therapeutically, these insights have yielded two convergent directions. In AA, mechanism-guided interruption of IFN-γ, IL-15, JAK, and STAT signaling, exemplified by baricitinib, ritlecitinib, and deuruxolitinib, reestablishes immune equilibrium and promotes anagen reentry. In AGA, modulation of the DHT and AR axis is now combined with vascular and mitochondrial enhancement using low-dose oral minoxidil, trophic biologics such as PRP or PRP-derived exosomes, and device-based bioenergetic conditioning through low-level light therapy to counter follicular miniaturization and extend growth.

At the intracellular level, network profiling reveals actionable checkpoints across JAK and STAT signaling, as well as androgen-responsive paracrine inhibitors such as DKK1 and PGD2, Wnt and β-catenin signaling, and the balance of BMP, AMPK, and mTOR in energy sensing, mitochondrial redox regulation, and apoptosis survival thresholds that collectively determine follicular regression or regeneration. Regenerative platforms are now advancing beyond suppression toward accurate reconstruction through stem cell-derived organoids that reconstitute epithelial and mesenchymal assembly, mesenchymal exosome therapeutics that reprogram inflammatory niches, and biomaterial scaffolds delivering Wnt agonists, antioxidants, or cytokine modulators with spatial precision. In parallel, a microbiome-mitochondria axis has emerged as a controllable lever for durable niche restoration, supporting combinatorial strategies that align microbial homeostasis with redox balance and immune recalibration.

Ultimately, the trajectory of precision trichology will be shaped by integrative clinical frameworks that connect multi-omics biomarkers across immune, metabolic, and microbial domains, utilizing AI-driven modeling and patient-derived follicular systems. This approach enables predictive, mechanism-oriented, and sustainable regeneration, reconstructing follicular architecture and restoring function at cellular, tissue, and ecosystem levels.

Funding

This paper was supported (in part) by the Research Funds of Kwangju Women’s University in 2025 (KWU25-048).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created during this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AA | Alopecia Areata |

| AGA | Androgenetic Alopecia |

| AR | Androgen Receptor |

| DHT | Dihydrotestosterone |

| JAK | Janus Kinase |

| STAT | Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription |

| HFSCs | Hair Follicle Stem Cells |

| MSC | Mesenchymal Stem Cell |

| Wnt | Wingless-type MMTV integration site family, member 1 |

| LLLT | Low-Level Light Therapy |

| PRP | Platelet-Rich Plasma |

| NF-κB | Nuclear Factor Kappa B |

| AMPK | AMP-Activated Protein Kinase |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| SCFA | Short-Chain Fatty Acid |

| VEGF | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor |

| PGC-1α | Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma Coactivator 1-alpha |

| TYK2 | Tyrosine Kinase 2 |

| SIRT1 | Sirtuin 1; NAD-dependent deacetylase sirtuin 1 |

| TEC | Tyrosine-protein kinase TEC |

| DKK1 | Dickkopf Wnt signaling pathway inhibitor 1 |

| KATP | ATP-sensitive potassium channel |

References

- Paus, R.; Cotsarelis, G. The biology of hair follicles. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 341, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hordinsky, M.; Ericson, M. Autoimmunity: Alopecia areata. J. Investig. Dermatol. Symp. Proc. 2004, 9, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petukhova, L.; Duvic, M.; Hordinsky, M.; Norris, D.; Price, V.; Shimomura, Y.; Kim, H.; Singh, P.; Lee, A.; Chen, W.V.; et al. Genome-wide association study in alopecia areata implicates both innate and adaptive immunity. Nature 2010, 466, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhalifah, A. Alopecia areata update. Dermatol. Clin. 2013, 31, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Tosti, A.; Wang, E.C.E.; Heilmann-Heimbach, S.; Aguh, C.; Jimenez, F.; Lin, S.J.; Kwon, O.; Plikus, M.V. Androgenetic alopecia. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2025, 11, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilhar, A.; Keren, A.; Paus, R. A new humanized mouse model for alopecia areata. J. Investig. Dermatol. Symp. Proc. 2013, 16, S37–S38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilhar, A.; Keren, A.; Shemer, A.; d’Ovidio, R.; Ullmann, Y.; Paus, R. Autoimmune disease induction in a healthy human organ: A humanized mouse model of alopecia areata. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2013, 133, 844–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, L.; Dai, Z.; Jabbari, A.; Cerise, J.E.; Higgins, C.A.; Gong, W.; de Jong, A.; Harel, S.; DeStefano, G.M.; Rothman, L.; et al. Alopecia areata is driven by cytotoxic T lymphocytes and is reversed by JAK inhibition. Nat. Med. 2014, 20, 1043–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufman, K.D. Androgens and alopecia. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2002, 198, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inui, S.; Itami, S. Molecular basis of androgenetic alopecia: From androgen to paracrine mediators through dermal papilla. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2011, 61, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.I.; Griendling, K.K. Regulation of signal transduction by reactive oxygen species in the cardiovascular system. Circ. Res. 2015, 116, 531–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, K.C.; Klatte, J.E.; Dinh, H.V.; Harries, M.J.; Reithmayer, K.; Meyer, W.; Sinclair, R.; Paus, R. Evidence that the bulge region is a site of relative immune privilege in human hair follicles. Br. J. Dermatol. 2008, 159, 1077–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moussa, A.; Eisman, S.; Sinclair, R.D.; Bhoyrul, B. Treatment of alopecia areata of the beard with baricitinib. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2023, 88, 948–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polak-Witka, K.; Rudnicka, L.; Blume-Peytavi, U.; Vogt, A. The role of the microbiome in scalp hair follicle biology and disease. Exp. Dermatol. 2020, 29, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zouboulis, C.C.; Coenye, T.; He, L.; Kabashima, K.; Kobayashi, T.; Niemann, C.; Nomura, T.; Olah, A.; Picardo, M.; Quist, S.R.; et al. Sebaceous immunobiology—Skin homeostasis, pathophysiology, coordination of innate immunity and inflammatory response and disease associations. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1029818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Liao, X.; Tang, S.; Wang, Q.; Lin, H.; Yu, X.; Xiao, Y.; Tao, X.; Zhong, T. Potential Therapeutic Targets for Androgenetic Alopecia (AGA) in Obese Individuals as Revealed by a Gut Microbiome Analysis: A Mendelian Randomization Study. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, B.S.; Ho, E.X.P.; Chu, C.W.; Ramasamy, S.; Bigliardi-Qi, M.; de Sessions, P.F.; Bigliardi, P.L. Microbiome in the hair follicle of androgenetic alopecia patients. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0216330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Liu, X. Gut microbiome, metabolome and alopecia areata. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1281660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otberg, N.; Finner, A.M.; Shapiro, J. Androgenetic alopecia. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. N. Am. 2007, 36, 379–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirmirani, P. Hormones and clocks: Do they disrupt the locks? Fluctuating estrogen levels during menopausal transition may influence clock genes and trigger chronic telogen effluvium. Dermatol. Online J. 2016, 22, 13030/qt32r353c4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya, E.C.; Bruinsma, R.L.; Kelly, K.A.; Feldman, S.R. How suitable are JAK inhibitors in treating the inflammatory component in patients with alopecia areata and vitiligo? Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 2022, 18, 189–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blumeyer, A.; Tosti, A.; Messenger, A.; Reygagne, P.; Del Marmol, V.; Spuls, P.I.; Trakatelli, M.; Finner, A.; Kiesewetter, F.; Trueb, R.; et al. Evidence-based (S3) guideline for the treatment of androgenetic alopecia in women and in men. J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. J. Ger. Soc. Dermatol. JDDG 2011, 9, S1–S57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwack, M.H.; Sung, Y.K.; Chung, E.J.; Im, S.U.; Ahn, J.S.; Kim, M.K.; Kim, J.C. Dihydrotestosterone-inducible dickkopf 1 from balding dermal papilla cells causes apoptosis in follicular keratinocytes. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2008, 128, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuboi, R.; Niiyama, S.; Irisawa, R.; Harada, K.; Nakazawa, Y.; Kishimoto, J. Autologous cell-based therapy for male and female pattern hair loss using dermal sheath cup cells: A randomized placebo-controlled double-blinded dose-finding clinical study. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2020, 83, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festa, E.; Fretz, J.; Berry, R.; Schmidt, B.; Rodeheffer, M.; Horowitz, M.; Horsley, V. Adipocyte lineage cells contribute to the skin stem cell niche to drive hair cycling. Cell 2011, 146, 761–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maekawa, M.; Ohnishi, T.; Balan, S.; Hisano, Y.; Nozaki, Y.; Ohba, H.; Toyoshima, M.; Shimamoto, C.; Tabata, C.; Wada, Y.; et al. Thiosulfate promotes hair growth in mouse model. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2019, 83, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, D.M.; Chaudhry, I.H.; Harries, M. Scarring Alopecias: Pathology and an Update on Digital Developments. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundberg, J.P.; Hordinsky, M.K.; Bergfeld, W.; Lenzy, Y.M.; McMichael, A.J.; Christiano, A.M.; McGregor, T.; Stenn, K.S.; Sivamani, R.K.; Pratt, C.H.; et al. Cicatricial Alopecia Research Foundation meeting, May 2016: Progress towards the diagnosis, treatment and cure of primary cicatricial alopecias. Exp. Dermatol. 2018, 27, 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dlova, N.C.; Salkey, K.S.; Callender, V.D.; McMichael, A.J. Central Centrifugal Cicatricial Alopecia: New Insights and a Call for Action. J. Investig. Dermatol. Symp. Proc. 2017, 18, S54–S56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharquie, K.E.; Schwartz, R.A.; Aljanabi, W.K.; Janniger, C.K. Traction Alopecia: Clinical and Cultural Patterns. Indian J. Dermatol. 2021, 66, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.R.; Craiglow, B.G. Treatment of traction alopecia with oral minoxidil. JAAD Case Rep. 2022, 23, 112–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, O.; Senna, M.M.; Sinclair, R.; Ito, T.; Dutronc, Y.; Lin, C.Y.; Yu, G.; Chiasserini, C.; McCollam, J.; Wu, W.S.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Baricitinib in Patients with Severe Alopecia Areata over 52 Weeks of Continuous Therapy in Two Phase III Trials (BRAVE-AA1 and BRAVE-AA2). Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2023, 24, 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubin, R. First Systemic Treatment for Severe Alopecia Is Approved. JAMA 2022, 328, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, T.; Wang, T.; Tang, M.; Liu, N. Comparative efficacy and safety of JAK inhibitors in the treatment of moderate-to-severe alopecia areata: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1372810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papierzewska, M.; Waskiel-Burnat, A.; Rudnicka, L. Safety of Janus Kinase inhibitors in Patients with Alopecia Areata: A Systematic Review. Clin. Drug Investig. 2023, 43, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khera, M.; Than, J.K.; Anaissie, J.; Antar, A.; Song, W.; Losso, B.; Pastuszak, A.; Kohn, T.; Mirabal, J.R. Penile vascular abnormalities in young men with persistent side effects after finasteride use for the treatment of androgenic alopecia. Transl. Androl. Urol. 2020, 9, 1201–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, D.D.; Marchese, M.; Cone, E.B.; Paciotti, M.; Basaria, S.; Bhojani, N.; Trinh, Q.D. Investigation of Suicidality and Psychological Adverse Events in Patients Treated With Finasteride. JAMA Dermatol. 2021, 157, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, A.K.; Heran, B.S.; Etminan, M. Persistent Sexual Dysfunction and Suicidal Ideation in Young Men Treated with Low-Dose Finasteride: A Pharmacovigilance Study. Pharmacotherapy 2015, 35, 687–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, G.S.; Kim, J.H.; Oh, S.Y.; Park, J.M.; Hong, J.S.; Lee, Y.S.; Lee, W.S. Safety and Tolerability of the Dual 5-Alpha Reductase Inhibitor Dutasteride in the Treatment of Androgenetic Alopecia. Ann. Dermatol. 2016, 28, 444–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Kim, J.E.; Lew, B.L.; Huh, C.H.; Kim, J.; Kwon, O.; Kim, M.B.; Lee, Y.W.; Lee, Y.; Park, J.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Low-Dose (0.2 mg) Dutasteride for Male Androgenic Alopecia: A Multicenter, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Parallel-Group Phase III Clinical Trial. Ann. Dermatol. 2025, 37, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirshburg, J.M.; Kelsey, P.A.; Therrien, C.A.; Gavino, A.C.; Reichenberg, J.S. Adverse Effects and Safety of 5-alpha Reductase Inhibitors (Finasteride, Dutasteride): A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Aesthetic Dermatol. 2016, 9, 56–62. [Google Scholar]

- Perera, E.; Sinclair, R. Treatment of chronic telogen effluvium with oral minoxidil: A retrospective study. F1000Research 2017, 6, 1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vano-Galvan, S.; Pirmez, R.; Hermosa-Gelbard, A.; Moreno-Arrones, O.M.; Saceda-Corralo, D.; Rodrigues-Barata, R.; Jimenez-Cauhe, J.; Koh, W.L.; Poa, J.E.; Jerjen, R.; et al. Safety of low-dose oral minoxidil for hair loss: A multicenter study of 1404 patients. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2021, 84, 1644–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feaster, B.; Onamusi, T.; Cooley, J.E.; McMichael, A.J. Oral minoxidil use in androgenetic alopecia and telogen effluvium. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2023, 315, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obi, A.; McKinley, J.; Oladunjoye, E.; Williams, A.; Li, V.; Wu, J.; Yang, C.; Darwin, E.; Gulati, N.; Haskin, A.; et al. Doxycycline for central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia: A single center retrospective analysis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2024, 91, 331–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiang, C.; Sah, D.; Cho, B.K.; Ochoa, B.E.; Price, V.H. Hydroxychloroquine and lichen planopilaris: Efficacy and introduction of Lichen Planopilaris Activity Index scoring system. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2010, 62, 387–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffin, M.O.; Ceballos, G.; Villarreal, F.J. Tetracycline compounds with non-antimicrobial organ protective properties: Possible mechanisms of action. Pharmacol. Res. 2011, 63, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirmirani, P.; Willey, A.; Price, V.H. Short course of oral cyclosporine in lichen planopilaris. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2003, 49, 667–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, B.K.; Sah, D.; Chwalek, J.; Roseborough, I.; Ochoa, B.; Chiang, C.; Price, V.H. Efficacy and safety of mycophenolate mofetil for lichen planopilaris. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2010, 62, 393–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, S.J.; Hsu, S. Lichen planopilaris treated with thalidomide. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2001, 45, 965–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dainichi, T.; Iwata, M.; Kaku, Y. Alopecia areata: What’s new in the epidemiology, comorbidities, and pathogenesis? J. Dermatol. Sci. 2023, 112, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connell, S.J.; Jabbari, A. The current state of knowledge of the immune ecosystem in alopecia areata. Autoimmun. Rev. 2022, 21, 103061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutic Udovic, I.; Hlaca, N.; Massari, L.P.; Brajac, I.; Kastelan, M.; Vicic, M. Deciphering the Complex Immunopathogenesis of Alopecia Areata. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, T.; Cheret, J.; Scala, F.D.; Rajabi-Estarabadi, A.; Akhundlu, A.; Demetrius, D.L.; Gherardini, J.; Keren, A.; Harries, M.; Rodriguez-Feliz, J.; et al. Interleukin-15 is a hair follicle immune privilege guardian. J. Autoimmun. 2024, 145, 103217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passeron, T.; King, B.; Seneschal, J.; Steinhoff, M.; Jabbari, A.; Ohyama, M.; Tobin, D.J.; Randhawa, S.; Winkler, A.; Telliez, J.B.; et al. Inhibition of T-cell activity in alopecia areata: Recent developments and new directions. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1243556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivera-Ruiz, I.; Gay-Mimbrera, J.; Gomez-Arias, P.J.; Aguilar-Luque, M.; Juan-Cencerrado, M.; Mochon-Jimenez, C.; Parra-Peralbo, E.; Isla-Tejera, B.; Gomez-Garcia, F.; Ruano, J. Meta-Analysis of Gene Expression Reveals the Core Transcriptomic Profile of Lesional Scalp in Alopecia Areata. Dermatol. Ther. 2025, 15, 2729–2748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, X.; Qu, Y.; Huang, J. Evaluating the Causal Relationship Between Human Blood Metabolites and the Susceptibility to Alopecia Areata. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2025, 24, e70248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perlmutter, J.; Akouris, P.P.; Fremont, S.; Yang, B.; Toth, E.; Eze, M.; Wiseman, M. The Role of Reactive Oxygen Species in the Pathogenesis of Alopecia Areata: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ski. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2025, 38, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, B.A.; Craiglow, B.G. Janus kinase inhibitors for alopecia areata. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2023, 89, S29–S32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.; Park, S.H.; Lew, B.L.; Park, H. The new era of JAK inhibitors: Impelling updates in Alopecia Areata Guideline. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2024, 38, e602–e606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.; Korman, N.J.; Tsai, T.F.; Shimomura, Y.; Feely, M.; Dutronc, Y.; Wu, W.S.; Somani, N.; Tosti, A. Efficacy of Baricitinib in Patients with Various Degrees of Alopecia Areata Severity: Post-Hoc Analysis from BRAVE AA1 and BRAVE AA2. Dermatol. Ther. 2023, 13, 3181–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senna, M.; Mostaghimi, A.; Ohyama, M.; Sinclair, R.; Dutronc, Y.; Wu, W.S.; Yu, G.; Chiasserini, C.; Somani, N.; Holzwarth, K.; et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of baricitinib in patients with severe alopecia areata: 104-week results from BRAVE-AA1 and BRAVE-AA2. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2024, 38, 583–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, J.M.; Mayo, T.T.; Bergfeld, W.F.; Dutronc, Y.; Yu, G.; Ball, S.G.; Somani, N.; Craiglow, B.G. Clinical Outcomes for Uptitration of Baricitinib Therapy in Patients With Severe Alopecia Areata: A Pooled Analysis of the BRAVE-AA1 and BRAVE-AA2 Trials. JAMA Dermatol. 2023, 159, 970–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, B.; Ohyama, M.; Kwon, O.; Zlotogorski, A.; Ko, J.; Mesinkovska, N.A.; Hordinsky, M.; Dutronc, Y.; Wu, W.S.; McCollam, J.; et al. Two Phase 3 Trials of Baricitinib for Alopecia Areata. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 1687–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hordinsky, M.; Hebert, A.A.; Gooderham, M.; Kwon, O.; Murashkin, N.; Fang, H.; Harada, K.; Law, E.; Wajsbrot, D.; Takiya, L.; et al. Efficacy and safety of ritlecitinib in adolescents with alopecia areata: Results from the ALLEGRO phase 2b/3 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2023, 40, 1003–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blair, H.A. Ritlecitinib: First Approval. Drugs 2023, 83, 1315–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, B.; Zhang, X.; Harcha, W.G.; Szepietowski, J.C.; Shapiro, J.; Lynde, C.; Mesinkovska, N.A.; Zwillich, S.H.; Napatalung, L.; Wajsbrot, D.; et al. Efficacy and safety of ritlecitinib in adults and adolescents with alopecia areata: A randomised, double-blind, multicentre, phase 2b-3 trial. Lancet 2023, 401, 1518–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coppinger, A.J.; Wambier, C.G. Most men choose eyebrows versus scalp hair: Response to Mostaghimi et al., “Evaluation of eyebrow and eyelash regrowth and patient satisfaction in the phase 3 THRIVE-AA2 trial of deuruxolitinib in adult patients with alopecia areata”. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2025, 92, e203–e204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, B.; Senna, M.M.; Mesinkovska, N.A.; Lynde, C.; Zirwas, M.; Maari, C.; Prajapati, V.H.; Sapra, S.; Brzewski, P.; Osman, L.; et al. Efficacy and safety of deuruxolitinib, an oral selective Janus kinase inhibitor, in adults with alopecia areata: Results from the Phase 3 randomized, controlled trial (THRIVE-AA1). J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2024, 91, 880–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Xiong, R.; Jin, S.; Li, Y.; Dong, T.; Wang, W.; Song, X.; Guan, C. MitoQ alleviates H2O2-induced mitochondrial dysfunction in keratinocytes through the Nrf2/PINK1 pathway. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2025, 234, 116811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsaati, A.A.; Kaliyadan, F.; Alsaadoun, D.; Alzakry, L.M.; Alzabadin, R.A.; Hakami, T.H.; Rubaian, N.F.B. Vitamin D and its Analogs in Treatment of Mild to Moderate Alopecia Areata: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Indian Dermatol. Online J. 2025. online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirkman, D.L.; Stock, J.M.; Shenouda, N.; Bohmke, N.J.; Kim, Y.; Kidd, J.; Townsend, R.R.; Edwards, D.G. Effects of a mitochondrial-targeted ubiquinol on vascular function and exercise capacity in chronic kidney disease: A randomized controlled pilot study. Am. J. Physiol. Renal. Physiol. 2023, 325, F448–F456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jimenez-Herrera, E.A.; Lopez-Zenteno, B.E.; Corona-Rodarte, E.; Parra-Guerra, R.; Zubiran, R.; Cano-Aguilar, L.E.; Barrera-Ochoa, C.; Asz-Sigall, D. Vitamin D and Alopecia Areata: From Mechanism to Therapeutic Implications. Ski. Appendage Disord. 2025, 520–530, online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garros, N.; Bustos-Salgados, P.; Domenech, O.; Rodriguez-Lagunas, M.J.; Beirampour, N.; Mohammadi-Meyabadi, R.; Mallandrich, M.; Calpena, A.C.; Colom, H. Baricitinib Lipid-Based Nanosystems as a Topical Alternative for Atopic Dermatitis Treatment. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Wang, Y.; Guo, Q.; Cao, J.; Feng, Y.; Ke, X. Nanostructured lipid carriers promote percutaneous absorption and hair follicle targeting of tofacitinib for treating alopecia areata. J. Control. Release 2024, 372, 778–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ytterberg, S.R.; Bhatt, D.L.; Connell, C.A. Cardiovascular and Cancer Risk with Tofacitinib in Rheumatoid Arthritis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamanaka, R.B.; Glasauer, A.; Hoover, P.; Yang, S.; Blatt, H.; Mullen, A.R.; Getsios, S.; Gottardi, C.J.; DeBerardinis, R.J.; Lavker, R.M.; et al. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species promote epidermal differentiation and hair follicle development. Sci. Signal. 2013, 6, ra8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, B.; Schoeb, T.R.; Bajpai, P.; Slominski, A.; Singh, K.K. Reversing wrinkled skin and hair loss in mice by restoring mitochondrial function. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beard, A.; Trotter, S.C. JAK 1-3 inhibitors and TYK-2 inhibitors in dermatology: Practical pearls for the primary care physician. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2024, 13, 4128–4134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhaylov, D.; Pavel, A.; Yao, C.; Kimmel, G.; Nia, J.; Hashim, P.; Vekaria, A.S.; Taliercio, M.; Singer, G.; Karalekas, R.; et al. A randomized placebo-controlled single-center pilot study of the safety and efficacy of apremilast in subjects with moderate-to-severe alopecia areata. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2019, 311, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guttman-Yassky, E.; Renert-Yuval, Y.; Bares, J.; Chima, M.; Hawkes, J.E.; Gilleaudeau, P.; Sullivan-Whalen, M.; Singer, G.K.; Garcet, S.; Pavel, A.B.; et al. Phase 2a randomized clinical trial of dupilumab (anti-IL-4Ralpha) for alopecia areata patients. Allergy 2022, 77, 897–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kageyama, R.; Ito, T.; Hanai, S.; Morishita, N.; Nakazawa, S.; Fujiyama, T.; Honda, T.; Tokura, Y. Immunological Properties of Atopic Dermatitis-Associated Alopecia Areata. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, E.; Shokrian, N.; Del Duca, E.; Meariman, M.; Glickman, J.; Ghalili, S.; Jung, S.; Tan, K.; Ungar, B.; Guttman-Yassky, E. Dupilumab induces hair regrowth in pediatric alopecia areata: A real-world, single-center observational study. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2024, 316, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavoletti, G.; Chiei-Gallo, A.; Barei, F.; Marzano, A.V.; Ferrucci, S.M. Tralokinumab as a therapeutic option for patients with concurrent atopic dermatitis and alopecia areata. Int. J. Dermatol. 2024, 63, 374–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kussini, J.; Pfutzner, W.; Muhlenbein, S. A Case of Unexpected Successful Treatment of Alopecia Areata With Tralokinumab in a Patient With Atopic Dermatitis. Int. J. Dermatol. 2025, 64, 1905–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babadjouni, A.; Reddy, M.; Zhang, R.; Raffi, J.; Phong, C.; Mesinkovska, N. Melatonin and the Human Hair Follicle. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2023, 22, 260–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.M.; Chen, W.J.; Qin, Y.; Xu, D.; Lai, Y.K.; He, S.H. Innovative Hydrogel Design: Tailoring Immunomodulation for Optimal Chronic Wound Recovery. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e2412360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, H.W.; Yang, B.C.; Ren, Y.Q.; Xue, Y. Applications of Antioxidant Nanoparticles in Immune-Mediated Inflammatory Diseases. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuevas-Diaz Duran, R.; Martinez-Ledesma, E.; Garcia-Garcia, M.; Bajo Gauzin, D.; Sarro-Ramirez, A.; Gonzalez-Carrillo, C.; Rodriguez-Sardin, D.; Fuentes, A.; Cardenas-Lopez, A. The Biology and Genomics of Human Hair Follicles: A Focus on Androgenetic Alopecia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Randall, V.A. Androgens and hair growth. Dermatol. Ther. 2008, 21, 314–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inui, S.; Fukuzato, Y.; Nakajima, T.; Kurata, S.; Itami, S. Androgen receptor co-activator Hic-5/ARA55 as a molecular regulator of androgen sensitivity in dermal papilla cells of human hair follicles. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2007, 127, 2302–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawaya, M.E.; Price, V.H. Different levels of 5alpha-reductase type I and II, aromatase, and androgen receptor in hair follicles of women and men with androgenetic alopecia. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1997, 109, 296–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceruti, J.M.; Leiros, G.J.; Balana, M.E. Androgens and androgen receptor action in skin and hair follicles. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2018, 465, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhi, J.; Feng, M.; Feng, X.; Niu, X.; Chen, W.; Jiang, X.; Bai, R. Wnt/beta-Catenin Signaling Pathway Targeting Androgenetic Alopecia: How Far Can We Go Beyond Minoxidil and Finasteride? J. Med. Chem. 2025, 68, 18829–18856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Liu, F.; Zhou, M.; Chen, S.; Huang, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, Q.; Zhou, X.; Li, Z.; et al. Enhancement of hair growth through stimulation of hair follicle stem cells by prostaglandin E2 collagen matrix. Exp. Cell. Res. 2022, 421, 113411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Chen, M.; Liu, F.; Wang, Y.; Xu, S.; Sha, K.; Peng, Q.; Wu, Z.; Xiao, W.; Liu, T.; et al. Androgen Receptor-Mediated Paracrine Signaling Induces Regression of Blood Vessels in the Dermal Papilla in Androgenetic Alopecia. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2022, 142, 2088–2099.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Huang, J.; Fu, D.; Liu, Z.; Wang, H.; Wang, J.; Qu, Q.; Li, K.; Fan, Z.; Hu, Z.; et al. Transcriptome Analysis Reveals an Inhibitory Effect of Dihydrotestosterone-Treated 2D- and 3D-Cultured Dermal Papilla Cells on Hair Follicle Growth. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 724310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, H.G.; Jung, M.; Jeong, S.Y.; Kim, J.; Han, S.D.; Kim, H.; Lee, S.; Lee, Y.; You, H.; Park, S.; et al. Improvement of androgenic alopecia by extracellular vesicles secreted from hyaluronic acid-stimulated induced mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2024, 15, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chew, E.G.Y.; Lim, T.C.; Leong, M.F.; Liu, X.; Sia, Y.Y.; Leong, S.T.; Yan-Jiang, B.C.; Stoecklin, C.; Borhan, R.; Heilmann-Heimbach, S.; et al. Observations that suggest a contribution of altered dermal papilla mitochondrial function to androgenetic alopecia. Exp. Dermatol. 2022, 31, 906–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsusaka, H.; Wu, T.; Furuya, K.; Yamada-Kato, T.; Bai, L.; Tomita, H.; Sugano, E.; Ozaki, T.; Kiyono, T.; Okunishi, I.; et al. Comprehensive transcriptome data to identify downstream genes of testosterone signalling in dermal papilla cells. Sci. Data 2022, 9, 731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rebora, A. Pathogenesis of androgenetic alopecia. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2004, 50, 777–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prodi, D.A.; Pirastu, N.; Maninchedda, G.; Sassu, A.; Picciau, A.; Palmas, M.A.; Mossa, A.; Persico, I.; Adamo, M.; Angius, A.; et al. EDA2R is associated with androgenetic alopecia. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2008, 128, 2268–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.J.; Cha, H.J.; Lim, K.M.; Lee, O.K.; Bae, S.; Kim, C.H.; Lee, K.H.; Lee, Y.N.; Ahn, K.J.; An, S. Analysis of the microRNA expression profile of normal human dermal papilla cells treated with 5alpha-dihydrotestosterone. Mol. Med. Rep. 2015, 12, 1205–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukasik, A.; Kozicka, K.; Pisarek, A.; Wojas-Pelc, A. The role of CYP19A1 and ESR2 gene polymorphisms in female androgenetic alopecia in the Polish population. Postepy Dermatol. Alergol. 2022, 39, 708–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boersma, I.H.; Oranje, A.P.; Grimalt, R.; Iorizzo, M.; Piraccini, B.M.; Verdonschot, E.H. The effectiveness of finasteride and dutasteride used for 3 years in women with androgenetic alopecia. Indian J. Dermatol. Venereol. Leprol. 2014, 80, 521–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, G.S.; Sim, W.Y.; Kang, H.; Huh, C.H.; Lee, Y.W.; Shantakumar, S.; Ho, Y.F.; Oh, E.J.; Duh, M.S.; Cheng, W.Y.; et al. Long-Term Effectiveness and Safety of Dutasteride versus Finasteride in Patients with Male Androgenic Alopecia in South Korea: A Multicentre Chart Review Study. Ann. Dermatol. 2022, 34, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsen, E.A.; Hordinsky, M.; Whiting, D.; Stough, D.; Hobbs, S.; Ellis, M.L.; Wilson, T.; Rittmaster, R.S.; Dutasteride Alopecia Research, T. The importance of dual 5alpha-reductase inhibition in the treatment of male pattern hair loss: Results of a randomized placebo-controlled study of dutasteride versus finasteride. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2006, 55, 1014–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stough, D.B.; Rao, N.A.; Kaufman, K.D.; Mitchell, C. Finasteride improves male pattern hair loss in a randomized study in identical twins. Eur. J. Dermatol. 2002, 12, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Piraccini, B.M.; Blume-Peytavi, U.; Scarci, F.; Jansat, J.M.; Falques, M.; Otero, R.; Tamarit, M.L.; Galvan, J.; Tebbs, V.; Massana, E.; et al. Efficacy and safety of topical finasteride spray solution for male androgenetic alopecia: A phase III, randomized, controlled clinical trial. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2022, 36, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.W.; Juhasz, M.; Mobasher, P.; Ekelem, C.; Mesinkovska, N.A. A Systematic Review of Topical Finasteride in the Treatment of Androgenetic Alopecia in Men and Women. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2018, 17, 457–463. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vahabi-Amlashi, S.; Layegh, P.; Kiafar, B.; Hoseininezhad, M.; Abbaspour, M.; Khaniki, S.H.; Forouzanfar, M.; Sabeti, V. A randomized clinical trial on therapeutic effects of 0.25 mg oral minoxidil tablets on treatment of female pattern hair loss. Dermatol. Ther. 2021, 34, e15131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirmez, R.; Salas-Callo, C.I. Very-low-dose oral minoxidil in male androgenetic alopecia: A study with quantitative trichoscopic documentation. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2020, 82, e21–e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vastarella, M.; Cantelli, M.; Patri, A.; Annunziata, M.C.; Nappa, P.; Fabbrocini, G. Efficacy and safety of oral minoxidil in female androgenetic alopecia. Dermatol. Ther. 2020, 33, e14234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, P.M.; Sinclair, R.D.; Kasprzak, M.; Miot, H.A. Minoxidil 1 mg oral versus minoxidil 5% topical solution for the treatment of female-pattern hair loss: A randomized clinical trial. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2020, 82, 252–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Ji, Y.; Zhou, M.; Zhou, X.; Xie, Y.; Zeng, X.; Shao, F.; Zhang, C. Platelet-Rich Plasma for Androgenetic Alopecia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Cutan. Med. Surg. 2023, 27, 504–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Qu, K.; Lei, Q.; Chen, M.; Bian, D. Effectiveness of Platelet-Rich Plasma in the Treatment of Androgenic Alopecia: A Meta-Analysis. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2024, 48, 977–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olisova, O.; Potapova, M.; Suvorov, A.; Koriakin, D.; Lepekhova, A. Meta-analysis on the Efficacy of Platelet-rich Plasma in Patients with Androgenetic Alopecia. Int. J. Trichology 2023, 15, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, J.; Zhu, L.; Pan, M.; Shen, L.; Tang, Y.; Fan, L. The additive value of platelet-rich plasma to topical Minoxidil in the treatment of androgenetic alopecia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0308986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes-Silva, R.; Santos, M.; Sequeira, M.L.; Silva, A.; Antunes, T.; Valejo-Coelho, P.; Neiva-Sousa, M. Platelet-Rich Plasma Effectiveness in Treating Androgenetic Alopecia: A Comprehensive Evaluation. Cureus 2025, 17, e77371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, C.; Ding, Y.; Zhang, R.; Du, Y.; Bi, L.; Zhao, M.; Wang, C.; Wu, Q.; Jing, H.; Fan, W. Platelet-rich plasma-derived exosomes stimulate hair follicle growth through activation of the Wnt/beta-Catenin signaling pathway. Regen. Ther. 2025, 29, 435–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Seo, J.; Tu, S.; Nanmo, A.; Kageyama, T.; Fukuda, J. Exosomes for hair growth and regeneration. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2024, 137, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karimi, N.; Dincsoy, A.B. The Role of Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes in Skin Regeneration, Tissue Repair, and the Regulation of Hair Follicle Growth. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2025, 1479, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandrashekar, B.S.; Lobo, O.C.; Fusco, I.; Madeddu, F.; Zingoni, T. Effectiveness of 675-nm Wavelength Laser Therapy in the Treatment of Androgenetic Alopecia Among Indian Patients: Clinical Experimental Study. JMIR Dermatol. 2024, 7, e60858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, M.; Stockslager, M.; Oakley, J.; Womble, T.M.; Sinclair, R. Clinical Safety and Efficacy of Dual Wavelength Low-Level Light Therapy in Androgenetic Alopecia: A Double-Blind Randomized Controlled Study. Dermatol. Surg. 2025, 51, 416–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pillai, J.K.; Mysore, V. Role of Low-Level Light Therapy (LLLT) in Androgenetic Alopecia. J. Cutan. Aesthetic Surg. 2021, 14, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lueangarun, S.; Visutjindaporn, P.; Parcharoen, Y.; Jamparuang, P.; Tempark, T. A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials of United States Food and Drug Administration-Approved, Home-use, Low-Level Light/Laser Therapy Devices for Pattern Hair Loss: Device Design and Technology. J. Clin. Aesthetic Dermatol. 2021, 14, E64–E75. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, J.S.; Ku, W.Y.; Lee, J.H.; Ahn, H.C. Low-level light therapy using a helmet-type device for the treatment of androgenetic alopecia: A 16-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, sham device-controlled trial. Medicine 2020, 99, e21181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werachattawatchai, P.; Khunkhet, S.; Harnchoowong, S.; Lertphanichkul, C. Efficacy and safety of oral spironolactone for female pattern hair loss in premenopausal women: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group pilot study. Int. J. Women’s Dermatol. 2025, 11, e227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devjani, S.; Ezemma, O.; Jothishankar, B.; Saberi, S.; Kelley, K.J.; Makredes Senna, M. Efficacy of Low-Dose Spironolactone for Hair Loss in Women. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2024, 23, e91–e92. Available online: https://jddonline.com/articles/efficacy-of-low-dose-spironolactone-for-hair-loss-in-women-S1545961624P0e91X/ (accessed on 14 October 2025). [PubMed]

- Kaiser, M.A.; Almeida, S.M.; Rodriguez, M.; Issa, N.; Issa, N.T.; Jimenez, J.J. Low-Level Light Therapy and Minoxidil Combination Treatment in Androgenetic Alopecia: A Review of the Literature. Ski. Appendage Disord. 2023, 9, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, J.; He, Y.; Wan, H.; Gao, Y. Effectiveness of platelet-rich plasma in treating female hair loss: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ski. Res. Technol. 2024, 30, e70004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]