Abstract

Objective: This study aimed to develop eco-friendly zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) using Punica granatum (pomegranate) peel extract and to evaluate their antioxidant, antimicrobial, and photoprotective potential. Method: ZnO NPs were synthesized via a green chemistry route employing polyphenol- and flavonoid-rich peel extract as reducing and stabilizing agents. The nanoparticles were characterized using FTIR, SEM, XRD, DSC, DLS, and UV–Vis spectroscopy. Biological activities were assessed through in vitro assays including antioxidant (DPPH), anti-collagenase, anti-elastase, anti-tyrosinase, antimicrobial activity, and SPF determination. In vivo photoprotective efficacy was further evaluated in UVB-irradiated rat models, with histological analysis to confirm structural skin changes. Results: The optimized ZnO NPs exhibited an average particle size of ~194 nm with a zeta potential of −18.2 mV, indicating good stability. They demonstrated notable antioxidant activity (DPPH IC50 = 52.91 µg/mL), substantial tyrosinase inhibition (72% at 200 µg/mL), and antibacterial activity with inhibition zones up to 19 mm against S. aureus and 17 mm against E. coli. The nanoparticles also showed excellent UV absorption, with an SPF value of 29.8, exceeding the FDA threshold for effective sun protection. In vivo, topical application of ZnO NPs in UVB-exposed rats led to a 69% reduction in epidermal thickness and preservation of collagen fibers compared with UV controls. Conclusions: These findings confirm that P. granatum peel extract–mediated ZnO NPs possess significant antioxidant, antimicrobial, and photoprotective activities.

1. Introduction

Skin serves as a flexible and self-repairing barrier among the internal and external environment of the body [1]. The deterioration of skin quality due to age is called “skin aging” [2]. Skin aging is an inevitable biological phenomenon caused by exposure to harmful external influences (extrinsic aging) or the age-dependent decline of cell function (intrinsic aging) [3,4,5,6,7,8]. It is caused by a combination of hormonal imbalances, environmental factors, photoaging, and chronological aging. Changes in inner and outer layers of the skin can lead to visible signs including, such as dry and less elastic skin [9]. Dermal changes include a decrease in skin thickness, rupture to the collagenous and elastic fibers, and a decrease in the skin’s ability to retain moisture [10]. Pomegranate (Punica granatum L.), a member of the family Punicaceae, is well adapted to semi-arid, mid-temperate, and subtropical climatic conditions [11]. It is a fruit that is abundant in polyphenols and has been used extensively in traditional practices. This fruit is commercially grown in central Asia, particularly in parts of Iran, and is now cultivated all over the world. The peel of the pomegranate represents a significant agro-industrial by-product, comprising about 60% of the fruit’s total weight [12]. Pomegranate peel possesses multiple cosmeceutical benefits, including cell regeneration, UV protection, anti-aging, skin hydration, exfoliation, antimicrobial activity, and reduction in stretch marks [13]. It is particularly rich in hydrolysable tannins (punicalagin, punicalin), phenolic acids (ellagic acid, gallic acid), and flavonoids (catechin, quercetin, anthocyanins) [12,13,14]. These bioactives exhibit potent antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and photoprotective effects. Ellagic and gallic acids stimulate collagen and elastin synthesis while inhibiting matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), thereby preserving skin firmness and reducing wrinkle formation. Quercetin and anthocyanins further enhance antioxidant defenses and suppress oxidative stress through modulation of NF-κB, MAPK, and Nrf2 pathways, which are central to inflammation and photoaging. Collectively, these phytoconstituents provide a mechanistic rationale for the anti-aging and photoprotective properties of pomegranate peel extract. In addition to oxidative stress and UV-induced damage, microbial colonization of the skin contributes significantly to premature aging and related disorders. Skin-associated bacteria and their metabolites can induce inflammatory responses and accelerate collagen degradation, thereby aggravating wrinkle formation and barrier dysfunction. Moreover, antibacterial protection is particularly important in photoaged skin, which is more susceptible to infections. Hence, evaluation of the antibacterial potential of PPE–ZnO nanoparticles is relevant for anti-aging applications, as it highlights their multifunctional role in protecting the skin from both oxidative and microbial insults. Although zinc oxide (ZnO) has long been employed as a physical UV filter in sunscreen formulations due to its broad-spectrum UVA and UVB protection, conventional bulk ZnO possesses several drawbacks. These include its whitish appearance and chalky texture on the skin, photocatalytic activity leading to the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and limited cosmetic acceptability. These shortcomings reduce consumer compliance and may cause skin irritation under prolonged use. Nanoscale ZnO overcomes many of these limitations by providing greater transparency, better dispersion, improved photostability, and more efficient UV-blocking capacity. Furthermore, the use of phytochemical-assisted green synthesis stabilizes ZnO nanoparticles, reduces potential toxicity associated with chemical methods, and enhances their applicability in safe and sustainable cosmeceutical formulations. When employed in the green synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles, they not only act as reducing and capping agents but also synergistically enhance the cosmeceutical potential of the resulting nanomaterials. Because of its UV-filtering, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and non-comedogenic properties, zinc oxide is widely used in industrial practice, particularly as a key active in skincare formulations for photoprotection and anti-aging benefits [15]. Zinc Oxide nanoparticles are inorganic materials, nontoxic and Compatible with skin, offering self-cleansing and antimicrobial properties [16]. Nanoparticles are frequently synthesized using chemical and physical methods that are expensive, toxic to the environment [17]. Current problem with many cosmetic creams is the inclusion of synthetic antioxidant material like BHA, BHT, propylene glycol, etc., which have potential health hazards. Zinc oxide is generally regarded as safe material for humans [18]. It exhibits promising antioxidant activity, capable of penetrating the stratum corneum and protecting the skin against reactive oxygen species [19]. In addition to their antioxidant capacity, bioactive compounds such as ellagic acid, quercetin, and gallic acid in pomegranate peel extract modulate signaling pathways including NF-κB, MAPK, and Nrf2, thereby reducing oxidative stress, collagen degradation, and inflammatory responses in skin. Similarly, ZnO nanoparticles exert photoprotective effects by attenuating ROS-mediated activation of AP-1 and MMPs, which are key mediators of photoaging. The synergistic interaction between PPE phytochemicals and ZnO NPs may thus downregulate collagenase/elastase activity while enhancing antioxidant defense through the Nrf2–ARE pathway, providing a strong mechanistic basis for their cosmetic applications. Although various botanical extracts such as Aloe vera, Camellia sinensis, and Azadirachta indica have been used to synthesize ZnO nanoparticles, these systems often face challenges including variable phytochemical content, inconsistent particle size, limited stability, and incomplete evaluation of safety and efficacy. Few studies have systematically assessed both anti-aging and photoprotective performance of botanical ZnO systems in in vivo models. The peel of Punica granatum, an agro-waste rich in stable polyphenols and flavonoids (e.g., ellagic acid, gallic acid, quercetin), offers unique advantages: strong antioxidant and UV-absorbing properties, cost-effectiveness, and sustainability. By using PPE as a reducing and stabilizing agent, it is possible to develop ZnO NPs with enhanced stability, biocompatibility, and multifunctional efficacy, addressing key performance and safety gaps in earlier green-synthesized ZnO systems. Skin aging is strongly associated with chronic exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation, which accelerates photoaging by generating reactive oxygen species (ROS), activating matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), and causing collagen degradation and loss of elasticity. Therefore, effective UV protection is intrinsically linked to anti-aging, as preventing photodamage helps maintain skin structure and function. Zinc oxide nanoparticles play a dual role in this regard: as broad-spectrum UV filters they physically block and scatter UVA and UVB radiation, and when synthesized through phytochemical-assisted green methods, they are additionally stabilized by polyphenolic compounds that provide intrinsic antioxidant activity. This combined photoprotective and antioxidant mechanism makes phyto-assisted ZnO NPs highly promising for cosmeceutical applications targeting both sun protection and anti-aging. Green synthesis approaches prefer natural materials because they provide a renewable, cost-effective, and eco-friendly alternative to conventional chemical methods, while also reducing the risk of hazardous by-products. Among various botanical sources, pomegranate (Punica granatum) peel represents an especially sustainable option due to its abundance as an agro-waste by-product and its high content of stable polyphenols such as ellagic acid, gallic acid, punicalagin, quercetin, and anthocyanins. These bioactive compounds not only function as reducing and stabilizing agents during ZnO nanoparticle formation but also impart intrinsic antioxidant and UV-protective activity, thereby synergistically enhancing the cosmeceutical potential of the nanoparticles. The use of pomegranate peel extract thus combines environmental sustainability with functional efficacy, offering advantages over other natural materials that may be less abundant, less stable, or less effective in conferring photoprotective properties. This research aims for green synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles from pomegranate peel extract for anti-aging and sun protection activities. The bioactive compounds present in peel acts as reducing, capping and stabilizing agents in synthesis of nanoparticles and also render biocompatible functionalities due to synergistic activity at low concentration. This can be an innovative approach to sustainability by maximizing resource utilization and minimizing waste generation as nanoparticle prepared by green technology are far superior than other method [20,21].

2. Material & Method

2.1. Material

Pomegranates were procured from the local fruit market in Pune, Maharashtra. Zinc sulfate heptahydrate (ZnSO4·7H2O) was employed as the precursor for nanoparticle synthesis. Standard reference compounds including gallic acid, quercetin, ellagic acid, DPPH, and mushroom tyrosinase (≥1000 U/mg) for the anti-aging assay, along with Folin–Ciocalteu reagent, were used. All other reagents were of analytical grade and purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. The plant material (Punica granatum L., Family: Punicaceae) was taxonomically identified and authenticated by the Botanical Survey of India, Western Regional Centre, Pune, Ministry of Environment, Forests & Climate Change, Government of India (Ref. No. BSI/WRC/Ident. Cer./2022/0033220017534; dated 4 March 2022). The authenticated voucher specimen number is ASAA2. The specimen was collected from Pimpri, Pune, Maharashtra, India (18.627° N, 73.807° E) (Figure 1).

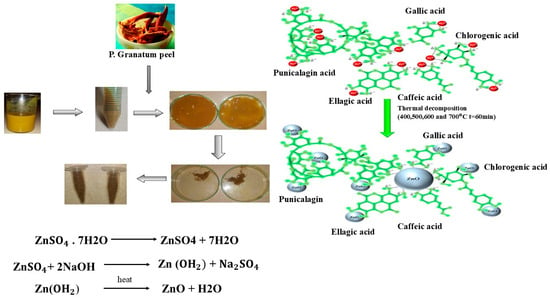

Figure 1.

Graphical Presentation of the Green Synthesis of ZnO Nanoparticles.

2.2. Procurement and Processing of Pomegranate Peel Extract

The peel was separated, washed thoroughly with distilled water, and shade-dried at room temperature (25–28 °C) for 7–10 days to preserve thermolabile phytochemicals. The dried material was then powdered and stored in an airtight container until further use.

2.2.1. Conventional Maceration

To prepare the pomegranate peel extract (PPE), 20 g of powder was logged in 100 mL of different solvents, namely methanol, distilled water, ethanol: water (50%: 50% and 70%: 30%) and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h in a shaking incubator at 200 rpm. After incubation, samples were filtered and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 15 min. The supernatants were concentrated using a rotary evaporator at 45 °C under vacuum (140 mbar) until dryness. The dried extracts were collected and stored at 4 °C for subsequent analysis of phenolic and flavonoid content, as well as antioxidant, antimicrobial, anti-aging, and sun-protection activities [22].

2.2.2. Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE):

The sonication method was employed to procure polyphenols from pomegranate peel powder. Four solvents were used: methanol, distilled water, ethanol: water (50%: 50% and 70%: 30%). Approximately 5 g peel powder was added with 100 mL of each solvent in a conical flask and subjected to sonication in water bath at 45 °C for 2 h. Resulting mixtures were filtered, centrifuged for 15 min at 3000 rpm. The supernatants were concentrated using a rotary evaporator at 45 °C under vacuum (140 mbar) until dryness. The dried extracts were collected and stored at 4 °C for further analysis [23]. Both conventional maceration and UAE methods were evaluated to compare extraction efficiency. Maceration, though time-consuming, is widely accepted for its simplicity and reproducibility, whereas UAE enhances polyphenol recovery through acoustic cavitation, leading to improved cell wall disruption and solvent penetration. In this study, comparative analysis demonstrated that aqueous macerated extract produced the highest yield and total phenolic content, making it the preferred extract for ZnO nanoparticle synthesis due to its safety and suitability for cosmetic applications. The extraction protocols were adapted from Malviya et al. (2014) and Feng et al. (2022), with minor modifications in solvent ratios, incubation time, and sonication conditions [22,23]. Different sample sizes (20 g for maceration and 5 g for UAE) were employed due to the inherent efficiency of the extraction methods. Maceration, being a passive process, requires a larger starting mass to achieve adequate yields, whereas UAE enhances cell wall disruption and solvent penetration through acoustic cavitation, enabling sufficient recovery with smaller quantities. Importantly, all extracts were subsequently concentrated, normalized, and tested at equivalent concentrations for biological activity, ensuring that variation in starting material did not influence the reliability of the results or the validity of conclusions.

2.3. Evaluation of Aqueous Extract

2.3.1. Total Phenols

Total phenolic content was determined using the Folin–Ciocalteu (FC) method with gallic acid as the standard, following the procedure described by Hadree et al., 2022 [24]. Briefly, 1 mL of PPE solution (1 mg/mL in distilled water) was mixed with 1 mL of FC reagent (diluted 1:10 with distilled water). After 5 min, 2 mL of sodium carbonate solution (7.5% w/v) was added, and the mixture was incubated at room temperature in the dark for 30 min. The absorbance was measured at 765 nm against a reagent blank using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer. A gallic acid calibration curve was prepared using standard solutions of 25, 50, 100, 150, and 200 µg/mL. Results were expressed as milligrams of gallic acid equivalents per gram of extract (mg GAE/g) [24].

2.3.2. TLC

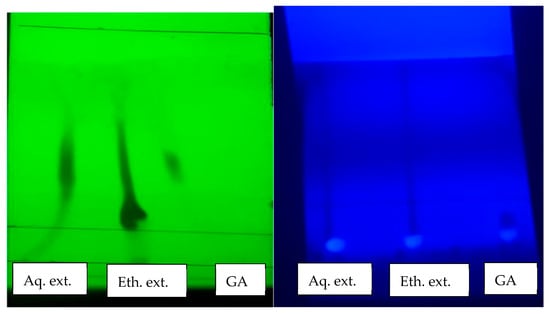

TLC was performed to confirm the presence of phenolic and flavonoid compounds in aqueous and ethanolic PPEs. Samples (10 µL of extract solution, 10 mg/mL) were spotted on silica gel 60 F254 plates (Merck) coated with 0.2 mm thick silica gel-G. Plates were developed using ethyl acetate: distilled water: formic acid (8:1:1, v/v/v) as the mobile phase. Spots were visualized under UV light at 254 nm and 365 nm and compared with standard reference compounds (gallic acid, quercetin, ellagic acid) [25]. (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Thin layer chromatography (TLC) of pomegranate peel extracts (aqueous and ethanolic) compared with gallic acid (GA) standard, visualized under UV (254 nm and 366 nm). Prominent spots in aqueous extract confirmed presence of phenolic compounds.

2.4. Preparation of Nanoparticles:

Green ZnO nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) were synthesized using Punica granatum peel extract (PPE) as both reducing and capping agent, adapted from prior peel-mediated ZnO protocols with minor modifications in reagent strength, temperature, and pH control. The zinc precursor solution was prepared at 5.75% w/v ZnSO4·7H2O (≈0.20 M). This corresponds to an equivalent molar concentration of ~0.20 M elemental Zn2+ (≈13.08 g/L), since each mole of ZnSO4·7H2O provides one mole of zinc ions. A chemically prepared ZnO batch without PPE was generated in parallel as a process control and used as a reference in all in vitro assays; bulk ZnO (commercial micronized powder) was also included where applicable.

- 1.

- Preparation of precursor and extract

- Zinc precursor: ZnSO4·7H2O was prepared at 5.75% w/v (≈0.20 M; 5.75 g in 100 mL deionized water).

- Plant extract: PPE (aqueous) obtained as described in Section 2.2.1, Section 2.2.2 and Section 2.3 was clarified by centrifugation and used fresh (room temperature).

- 2.

- Reaction setup

- Volume ratio: 20 mL PPE was added dropwise (~1 mL/min) into 100 mL of the ZnSO4·7H2O solution under constant stirring (600 rpm) at 60 °C on a temperature-controlled hotplate.

- pH control: pH was adjusted and maintained using 0.8% w/v NaOH (≈0.20 M) added dropwise to reach an alkaline medium (screened range pH 8–12 during optimization). A visible yellowish-white precipitate indicated ZnO NP formation.

- 3.

- Aging, collection, and washing: The reaction mixture was aged for 1 h off-heat while stirring (room temperature), then centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 20 min. The pellet was washed 3× with deionized water (and once with ethanol, optional) to remove unreacted ions and loosely bound organics.

- Drying and storage: The washed pellet was dried at 60 °C (hot-air oven) to constant weight, gently powdered in an agate mortar, and stored in amber vials in a desiccator until use.

- 4.

- Process notes and controls: A chemical-route ZnO (no PPE) batch was prepared in parallel for comparative UV–Vis/optical characterization as a method control (see Section 3.3.1). All glassware was pre-washed with dilute HNO3 and rinsed with deionized water to minimize adventitious ions.

- 5.

- Final synthesis conditions used for the main batches: Guided by the BBD study (Section Box–Behnken Design (BBD) Optimization), the optimized condition employed for preparative batches was pH 10, 60 °C, and 5.75% w/v ZnSO4·7H2O (≈0.20 M), yielding nanoparticles with ~194 nm hydrodynamic size, PDI 0.33, and ζ = −18.2 mV (see Section 2.5.7 and Section 3.2) [21,26,27,28,29].

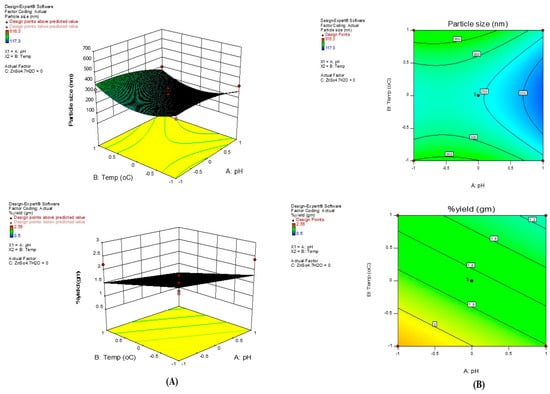

Box–Behnken Design (BBD) Optimization

Box–Behnken design (Design-Expert version 13) was used to optimize the ZnOPPE-NPs. The particle size, PDI, and yield (g) was selected as dependent variables, and the concentration of ZnSO4·7H2O (% w/v), pH, and temperature (°C) as independent variables, based on the results of their preliminary study. The software generated 13 formulations which are presented in Table 1. In our BBD, pH (A) and temperature (B) exerted a negative effect on particle size and a positive effect on yield, while ZnSO4·7H2O concentration (C) showed the opposite trend—increasing size and reducing yield at higher levels. These effects are captured by the fitted linear and quadratic models (Equations (4) and (5)), with tight agreement between adjusted/predicted R2 and overall R2, supporting model adequacy. The response surfaces and contour plots (Figure 3A,B locate a well-defined optimum that minimizes size while maintaining acceptable yield. Guided by these surfaces, we selected pH 10/60 °C/5.75% w/v ZnSO4·7H2O for preparative batches, which consistently produced ~194 nm particles with PDI ≈ 0.33 and ζ ≈ −18.2 mV. This optimization strategy and factor-directionality agree with prior green ZnO optimization using response-surface methods, which similarly report alkaline pH and moderate temperature as size-reducing and yield-enhancing, and higher precursor strength as size-increasing due to aggregation/growth kinetics [28], and are consistent with peel-mediated systems reported for citrus/pomegranate matrices [21,26,29]. Among the 13 runs presented in Table 1, Run 4 (pH 10, 60 °C, 5.75% w/v ZnSO4·7H2O) represented the optimal condition, yielding nanoparticles of ~194 nm with acceptable PDI and yield. This run was therefore selected for preparative synthesis and further characterization. To determine the best-fit model, the data for each response was fitted into several experimental design models. Each response was plotted as a 3-D graph, displaying the independent variables’ graphical representation against the responses. Based on the BBD surface response analysis (pH 8–12, 30–90 °C, 4.75–6.75% w/v ZnSO4·7H2O), subsequent preparative syntheses employed the optimized condition pH 10/60 °C/5.75% w/v, which consistently yielded the smallest particle size with acceptable yield and colloidal stability [28]. Although zeta potential was measured to assess the colloidal stability of PPE–ZnO nanoparticles (ζ = −18.2 mV), this parameter was not included as a dependent variable in the Box–Behnken Design (BBD) optimization. The optimization focused on particle size, PDI, and yield, which are directly governed by process variables (pH, temperature, and precursor concentration). In contrast, zeta potential primarily depends on the intrinsic phytochemical composition of the peel extract (polyphenols, flavonoids, proteins), which cannot be systematically varied in the same manner. Therefore, ζ-potential was reported as a characterization parameter confirming moderate stability, rather than as an optimization response.

Table 1.

Formulation development with design matrix of the Box–Behnken experiments.

Figure 3.

(A) 3D response surface plots. (B) Contour plots.

2.5. Characterization

2.5.1. UV–Visible Spectroscopy

Formation of ZnO NPs was confirmed by solution UV–visible spectrophotometry (Shimadzu UV-1601). Dispersions were scanned from 200–800 nm using deionized water as the blank in 1.0 cm quartz cuvettes.

Sample preparation and concentrations: A primary dispersion of PPE–ZnO NPs was prepared at 1.0 mg mL−1 in deionized water, bath-sonicated for 10 min to minimize reversible agglomerates, and then diluted to 50, 100, and 200 µg mL−1 with water to keep absorbance ≤ 1.0 AU throughout the scan. For comparison controls, (i) a chemical-route ZnO batch prepared without PPE (Section 2.4, process control) and (ii) PPE alone (matched to the same final mass concentration) were dispersed in water and measured under identical conditions. Where intrinsic color from PPE contributed background absorbance, a sample-matched PPE blank (PPE at the same concentration but without Zn precursor) was recorded and, when stated, subtracted to aid band-edge visualization.

Acquisition parameters: Baseline correction was performed against water prior to each series. Spectra were collected at 1 nm data pitch with medium scan speed and an instrument slit width set to the default analytical setting. Cuvettes were rinsed 3× with sample between runs.

Data handling and interpretation: Spectra were evaluated for the characteristic near-band-edge absorption of ZnO in the 360–380 nm region (excitonic/band-gap transition), distinguishing it from higher-energy π→π* contributions of PPE capping molecules (~250–270 nm). For clarity, first-derivative traces were optionally computed to locate the band-edge inflection, and spectra from the chemical-route ZnO control were overlaid to confirm ZnO-specific features. All measurements were performed in triplicate (n = 3), and representative spectra are reported. The UV–Vis procedure was adapted from prior peel-mediated ZnO reports with minor adjustments to dispersion and dilution steps [29].

2.5.2. FTIR

FTIR analysis was performed to molecular dispersion of extracts in nanoparticle synthesis. The technique enabled the identification of functional groups associated with compounds adsorbed on the nanoparticle surface, thereby providing molecular-level information. The spectra were noted to be in the range of 4000–400 cm−1. FTIR characterization of green-synthesized ZnO NPs followed the procedure reported by Shaban et al. (2022) [30].

2.5.3. PXRD Analysis

X-ray diffraction study was carried out to examine the crystalline structure of zinc oxide nano particles biosynthesized using extract. XRD analysis was performed as described by Abdelmigid et al. (2022) [26].

2.5.4. DSC

DSC study was carried out to study molecular dispersion and a change in melting temperature. Nanoparticles have a higher surface/volume ratio, which means that they can typically melt between −263.15 and −173.15 °C below the bulk material. To describe the decomposition and thermal stability of nanoparticles, DSC analysis was utilized, which measured the nanoparticles’ temperature between 50 and 600 °C at heating rate of 10 °C/min. To describe the decomposition and thermal stability of nanoparticles, DSC analysis was utilized, which measured the nanoparticles’ temperature between 50–600 °C at 10 °C/min, following the procedure outlined by Al-nehia et al. (2021) [31].

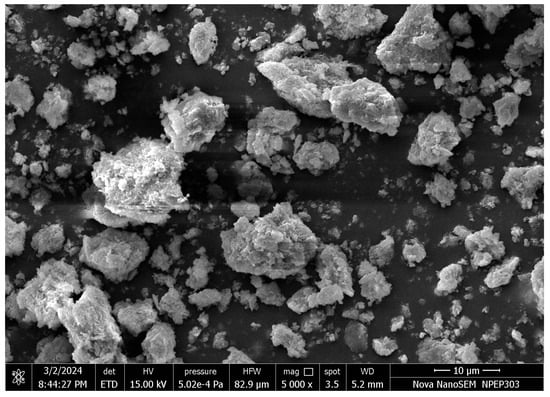

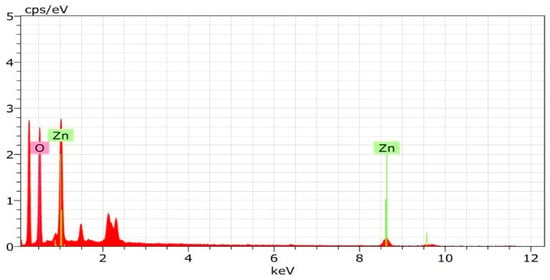

2.5.5. SEM & EDX

Morphology, size and shape of biosynthesized ZnO NPs of PPE were studied with SEM. The primary composition of prepared nanomaterials was examined using EDS spectra. The morphology and elemental analysis methods were adapted from Djearamane et al. (2022) [32].

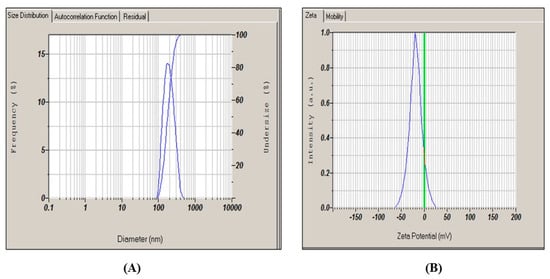

2.5.6. Size and Surface Charge Analysis

The size of the synthesized ZnO nanoparticles was determined using DLS technique. Zeta potential, a key parameter for assessing nanoparticle stability, was also measured. For analysis, 1 mg of ZnO nanoparticles was dispersed in 10 mL of distilled water, sonicated for 5 min, and subsequently analyzed using a Horiba SZ 100. Particle size and surface charge determination were performed as described by Yassin et al. (2022) [33]

2.5.7. DPPH Radical Scavenging

Free-radical scavenging activity was determined using the DPPH assay. Briefly, 1.0 mL of sample (1 mg mL−1 stock; working concentrations prepared in ethanol as required) was mixed with 2.0 mL of DPPH solution (80 µg mL−1 in absolute ethanol). A reagent blank contained ethanol instead of DPPH, and a sample blank contained ethanol instead of sample. Ascorbic acid served as a positive control at the same concentration series as the samples. Mixtures were vortexed and incubated for 30 min at 37 °C in the dark, then the absorbance was recorded at 517 nm against ethanol using a Shimadzu UV-1800 spectrophotometer with 1 cm pathlength cuvettes. Each condition was run in triplicate (n = 3). Radical scavenging was calculated as:

and IC50 values were obtained from the concentration–response curve. Methodology followed prior reports with minor adaptations [33].

DPPH scavenging (%) = A_blank − A_sample)/A_blank × 100

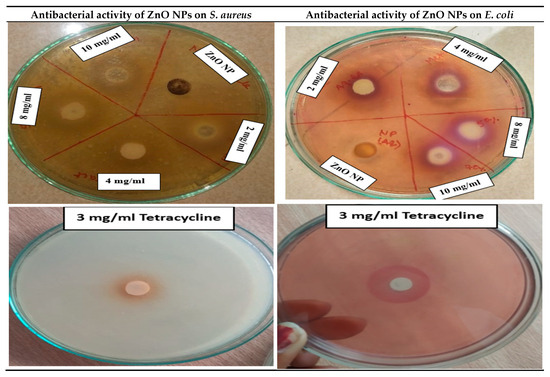

2.5.8. Antibacterial Activity

Antibacterial activity for obtained ZnO-PPE was evaluated using the pour plate method against Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli. Sterilized nutrient agar medium was prepared, and the test samples were distributed using sterilized water. The bacterial cultures were mixed with molten sterilized nutrient agar and poured into Petri plates, which were allowed to solidify undisturbed. Wells of 10 mm diameter were created using a sterile borer, with each plate containing four wells: one for plant extract (100 μL of PPE) and three for ZnO nanoparticles at concentrations of 2, 4, and 8 mg/mL (100 μL each). The plates were left at room temperature for a few hours and subsequently incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. For benchmarking, wells containing ZnO (no-PPE control) and bulk ZnO were included at the same concentrations (2, 4, and 8 mg/mL) under identical conditions to compare uncapped and micronized references with PPE–ZnO NPs. Following incubation, diameter of the inhibition zones was performed following the protocol of Chamkouri et al. (2022) [34].

2.5.9. Sun Protection

Optical absorption of ZnO samples was analyzed by UV-DRS (Shimadzu UV-2050) using BaSO4 as reference (200–800 nm). In vitro SPF was determined by the Mansur method (Labomed UVS-2700, 290–320 nm, 5 nm intervals). SPF was calculated using Mansur’s equation as in Elbrolesy et al. (2023) [35]. For benchmarking, three materials were tested under identical conditions:

- PPE–ZnO NPs (test),

- ZnO (no-PPE control) synthesized by the same chemical route but without plant extract (process control prepared in Section 2.4), and

- Bulk ZnO (commercial micronized powder).

Each material was dispersed at 1.0 g in 100 mL ethanol (10 mg mL−1 stock), vortexed and bath-sonicated 10 min, then measured neat or after dilution to maintain A(λ) within the linear range. SPF was calculated as: with CF = 10, using the standard EE × I weighting factors. Measurements were performed in triplicate (n = 3).

where CF = 10, A is the ZnO NPs absorbance, I is the solar intensity spectrum, and EE is the erythemal effect [35].

SPF = CF × EE × I (λ) × abs (λ)

2.6. In Vitro Anti-Aging Activity of Extract and Extract Loaded Nanoparticles

Anti-Tyrosinase Activity

Tyrosinase inhibition was quantified by the dopachrome method using L-DOPA as substrate, adapted from Silva et al., 2017, [36] and subsequent reports with minor modifications. Assays were performed in 96-well plates (200 µL final volume/well) using 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 6.8. Working solutions: mushroom tyrosinase (≥1000 U mg−1; stock prepared fresh in buffer and kept on ice), L-DOPA 2.0 mM in buffer (fresh, light-protected), and test samples (PPE and PPE–ZnO NPs) prepared in ethanol/buffer as needed. Unless otherwise stated, wells contained 140 µL buffer + 20 µL sample (or control) + 20 µL enzyme, equilibrated 5 min at 25–30 °C (dark); the reaction was initiated by adding 20 µL L-DOPA (final L-DOPA 0.2 mM). Formation of dopachrome was monitored at 475 nm after 10 min (endpoint) using 1 cm pathlength equivalent; kinetic reads (0–10 min) were optionally recorded to confirm linearity. Controls/Blanks: (i) Reaction control: 20 µL vehicle (matching sample solvent; 50% DMSO where applicable) instead of sample; (ii) Reagent blank: all components except L-DOPA to correct background; (iii) Sample blank (optional): sample without enzyme to correct intrinsic absorbance if colored. Positive control: L-ascorbic acid across the same concentration series. Each condition was run in triplicate (n = 3). % inhibition was calculated as

and IC50 values were obtained from concentration–response curves. References for the procedural basis are provided in [36,37]. In addition to PPE and PPE–ZnO NPs, ZnO (no-PPE control) and bulk ZnO were tested across the same concentration series; sample-matched blanks were recorded to correct any baseline scattering/absorbance.

[(A_control − A_sample)/A_control] × 100

2.7. In–Vivo Anti-Aging and Sun Protection Study

The in vivo anti-photoaging study was conducted using Wistar rats (6–8 weeks old, 150–180 g, both sexes, n = 6) divided into five groups as detailed in Table 2. All experiments were performed following the guidelines of the Committee for the Purpose of Control and Supervision of Experiments on Animals (CPCSEA), Government of India, and were approved by the Institutional Animal Ethics Committee (IAEC Reg. No. DYPIPSR/IEAC/Nov/23-24/P-20 Dated 30 November 2023). Animals were housed under controlled environmental conditions (22 ± 2 °C, 12 h light/dark cycle, 50–60% humidity) with food and water ad libitum. Photoaging was induced using a UVB irradiation source (solar simulator fitted with UVB lamps, 290–320 nm, peak at 312 nm; Spectroline, Melville, NY 11747USA) positioned 30 cm above the dorsal skin. The radiation dose was adjusted to 40–80 mJ/cm2 per exposure using a UV radiometer, three times per week for six consecutive weeks. During exposure, animals were restrained in well-ventilated cages to ensure uniform irradiation and prevent eye contact. The dorsal region (2 × 2 cm) was shaved 24 h prior to the first exposure. After wrinkle induction, topical treatment with formulations (extract, PPE–ZnO NPs, marketed cream, or vehicle) was applied at 0.25–0.5 g per inch2 daily throughout the study.

Table 2.

Grouping & treatment of animals.

At the end of the experimental period, animals were sacrificed under anesthesia, and skin tissues were collected for biochemical assays and histopathological evaluation (H&E staining). The study design is summarized in Table 2 [38].

3. Results & Discussion

The aqueous extract from Punica granatum peel contains proteins, tannins, alkaloids, phenolic compounds, flavonoids, glucosides, and saponins. These compounds have various chemical and physical characteristics that enhance the peel’s antioxidant, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and potentially anti-aging properties. As a result, the peel is valuable in therapeutic and cosmetic applications, and it also has the ability to reduce and stabilize metal ions. In this study, the aqueous peel extract of P. granatum was used to cap Zn2+ ions, thereby initiating nucleation in the reaction mixture and producing ZnO NPs. These ZnONPs were then stabilized and characterized using different methods, and their potential for anti-aging and sun protection was evaluated.

3.1. Evaluation of Aqueous Extract

3.1.1. Extraction Yield

The choice of solvent was a critical factor influencing extraction yield and the recovery of antioxidant compounds. In this study, five solvents were evaluated for their extraction efficiency. The yields were obtained in the following order: water > ethanol: water (50% 50%) > methanol > ethanol: water (30% 70%) > ethanol. Water produced the highest yield (24.2%), whereas ethanol gave the lowest (9.98%). The variation in extraction efficiency was attributed to differences in solvent polarity and their capacity to solubilize diverse phytochemical constituents. These results demonstrated that water, owing to its high polarity, was the most effective solvent for extracting a broad range of hydrophilic compounds from the plant matrix.

3.1.2. Determination of Total Phenols

Among the five pomegranate peel extracts (PPE), water showed the highest total phenolic content (TPC = 398 ± 1.78 mg GAE/g). This supports the selection of the aqueous macerated extract for downstream work, given both its phenolic richness and cosmetic safety. Across solvents, TPC varied with polarity; hydroalcoholic mixtures (e.g., 50% ethanol–water) and methanol provided intermediate TPC values, while ethanol alone was lowest. These observations are consistent with reports that polar and mixed-polarity media enhance recovery of hydrophilic phenolics, while pure ethanol underperforms for such constituents.

3.1.3. Thin Layer Chromatography

Thin layer chromatography (TLC) demonstrated the presence of key phenolic compounds, including gallic acid, ellagic acid, in both aqueous and ethanolic pomegranate peel extracts. At UV 254 nm, gallic acid appeared as green, fluorescent spots at Rf 0.10–0.11, with ethanolic extract showing similar spots at Rf 0.11 and an additional higher Rf (~0.75) indicating other phenolics. The aqueous extract showed dark bluish-green spots near Rf 0.10 and ~0.7, reflecting phenolic diversity. Under UV 366 nm, gallic acid displayed a faint spot at Rf 0.10, while ethanolic and aqueous extracts showed blue and bright green fluorescence at Rf 0.47 and 0.50, respectively. After Folin spraying, spots turned blue green, confirming phenolic identity. Although TLC is qualitative, sharper spots in aqueous extracts corresponded to higher phenolic content, confirmed by the Folin–Ciocalteu assay which showed greater mg GAE/g values in aqueous versus ethanolic extracts. These results affirm that aqueous extraction more effectively recovers bioactive phenolics like gallic acid.

3.2. Optimization of Prepared ZnO NPs

The optimal conditions for the green-mediated synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles (ZnONPs) from aqueous leaf extracts of Punica granatum were established using the Box–Behnken Design. The model revealed highly significant linear and quadratic effects, with a p-value < 0.0001. The adjusted and predicted R2 values (0.8054 and 0.9422, respectively) were in close agreement with the overall R2 value (0.99997), confirming a high level of model fitness. The improved green-mediated synthesis of ZnONPs using P. granatum peel extract is illustrated in Figure 3A,B which presents the 3D surface plots, graphical representations, and contour diagrams. In addition, the Lack of Fit test for the BBD model was found to be statistically insignificant (p > 0.05), confirming that the experimental data adequately fit the selected quadratic model without unexplained systematic variation. This further supports the robustness of the optimization model. Although ζ-potential was not included as a formal BBD response, it is closely related to reaction/incubation time and surface capping dynamics. Extended reaction times may increase particle growth and reduce surface charge density, thereby lowering colloidal stability, whereas optimized reaction duration (1 h aging) yielded a borderline ζ of −18.2 mV, sufficient for short-term dispersion. Future optimization models could integrate ζ-potential alongside particle size and yield to capture stability considerations more explicitly.

The results indicated that each factor influenced the green synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles (ZnONPs), with a strong correlation observed among the three variables in achieving enhanced synthesis. The Box–Behnken Design (BBD) provided optimal levels of each parameter for improved environmentally friendly ZnONP synthesis. In the present study, three independent factors—zinc sulfate heptahydrate concentration, temperature, and pH—were optimized across 13 experimental runs. The outcomes were analyzed using both linear and quadratic models. The relationship between % yield and independent variables was expressed by the following linear equation:

Y (% yield) = 1.67 − 0.19A − 0.34B + 0.46C

While the following second order polynomial quadratic equation represents the empirical relationship between particle size and the independent variables.

where Y denotes ZnO NP synthesis (% yield & particle size) whereas A, B, & C are pH, temperature & ZnSO4.7H2O concentration, respectively. Here, positive coefficient indicates decrease in particle size and increase in % yield while a negative effect means increase in particle size and decrease in % yield. The optimization results indicate clear factor–response trends: raising pH from 8→10 and temperature from 30→60 °C is associated with smaller hydrodynamic size and higher yield, whereas increasing ZnSO4·7H2O beyond ~5.75% w/v tends to increase size and reduce yield, likely due to accelerated growth and agglomeration at higher ionic strength. The regression terms (Equations (4) and (5)) capture these effects, and the BBD surfaces identify pH 10/60 °C/5.75% w/v as a robust operating window that balances nucleation and controlled growth. Notably, the optimized batch prepared under these conditions reproducibly delivered ~194 nm, PDI 0.33, ζ −18.2 mV (Section 2.5.7 and Section 3.2), aligning with the BBD predictions and confirming model validity. Similar optimization outcomes—favoring alkaline pH, moderate temperature, and moderate precursor strength—have been reported for green ZnO systems using BBD/RSM, and specifically for peel-mediated ZnO nanoparticles [28], including orange peel [21] and pomegranate peel contexts [26,29], thereby validating our optimization approach. Based on the regression coefficient analysis of the quadratic model, among the three tested variables, pH (A) and reaction temperature (B) showed a negative correlation with particle size and a positive correlation with % yield, whereas zinc sulfate concentration (C) displayed a positive correlation with particle size and a negative correlation with % yield. The ideal values for synthesizing the smallest NPs were located more easily by using 3D contour plots. These visual aids provided an interpretation of how two test variables interacted with a third variable held constant. The contour plots (Figure 3B) show that the experimental region contained the optimum point for reducing the average diameter of ZnO NPs and for increasing % yield. This validates the concentration ranges used for the independent variables in this study. The concave response surfaces obtained indicate that the operating conditions were ideal and well-defined. The relationship between temperature and metal concentration is illustrated in Figure 3A. The figure indicates that as temperature and metal concentration increased, the average diameter size decreased. This can be explained by the fact that, up to a certain point, increasing the concentration of metal ions causes particle growth to speed up, resulting in smaller-sized nanoparticles. Additionally, a reaction mixture containing a higher concentration of metal precursor may cause the growing nanoparticles to aggregate more, leading to the formation of larger nanoparticles. For the smallest particle size, we used moderate temperatures and metal concentrations. We found that the nanoparticle size increased as the temperature rose. At incorrect temperatures, the enzymes and active molecules involved in the biogenesis process became denatured, inactivated, or less active, leading to larger nanoparticles and reduced stability. Additionally, it was suggested that higher temperatures lead to smaller nanoparticles due to increased reaction rates and kinetic energy. To achieve the highest percent yield optimal pH, temperature and zinc sulfate concentration is required. The pH of the reaction medium significantly affects the stability and solubility of Zn2+ ions and the formation of zinc oxide nanoparticles while the temperature at which the synthesis is conducted affects the rate of nucleation and growth of nanoparticles. The optimal values of the variables were pH value 10, temperature 60 °C, and ZnSO4. 7H2O 5.75% w/v. The model predicted the smallest particles size of PPE_ZnO NPs that can be obtained using optimum conditions to be 194.1 nm and % yield to be 2.36 g.

Y (NPs Size) = 254.78 − 50.70A − 9.40B + 37.05C − 8.70AB − 9.15AC − 154.95BC + 41.14 A2 + 106.16B2 + 77.21C2

3.3. Characterization

3.3.1. UV-Vis Spectral Analysis

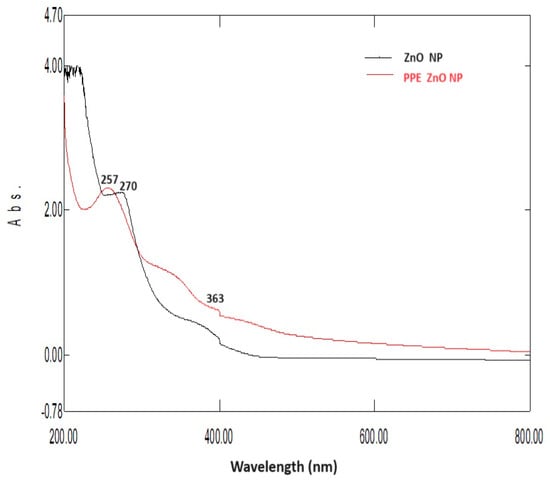

UV–Vis spectra of PPE–ZnO NPs showed two contributions: (i) a near-band-edge absorption of ZnO centered in the 360–380 nm region, consistent with the excitonic/band-gap transition of ZnO (Eg ≈ 3.2–3.3 eV), confirming nanoparticle formation; and (ii) a higher-energy band around ~250–270 nm attributable to π→π transitions of aromatic phenolics (and possibly weak n→π* features of carbonyl-containing constituents) from the PPE capping layer. We therefore describe the ZnO feature as band-edge absorption rather than surface plasmon resonance (SPR), which is not applicable to stoichiometric ZnO under our conditions. The modest shift in the band-edge position for PPE–ZnO relative to the control is compatible with differences in effective domain size and surface states, not plasmonic behavior. The UV–Vis absorption spectra for zinc oxide nanoparticles synthesized from pomegranate peel (PPE–ZnO NPs) showed characteristic absorbance peaks at 257 nm and 363 nm, while plain ZnO-NPs exhibited a single absorption band at 270 nm (Figure 4). The observed blue shift in PPE–ZnO NPs suggests a reduction in particle size, as smaller nanoparticles typically absorb at shorter wavelengths. These absorption features are consistent with the band-gap region of ZnO (360–380 nm), confirming the formation of ZnO nanoparticles. The spectral differences between PPE–ZnO NPs and plain ZnO-NPs further validate the successful phyto-assisted synthesis and demonstrate the stabilizing influence of phytochemicals from the peel extract. Similar findings of phytochemical-mediated ZnO exhibiting blue-shifted peaks compared to chemically synthesized ZnO have been reported in prior studies.

Figure 4.

UV–Vis absorption spectra of plain zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO-NPs) and pomegranate peel-mediated ZnO nanoparticles (PPE–ZnO NPs). PPE–ZnO NPs exhibited peaks at 257 nm and 363 nm, while plain ZnO-NPs showed a peak at 270 nm, indicating a blue shift due to smaller particle size and phytochemical stabilization.

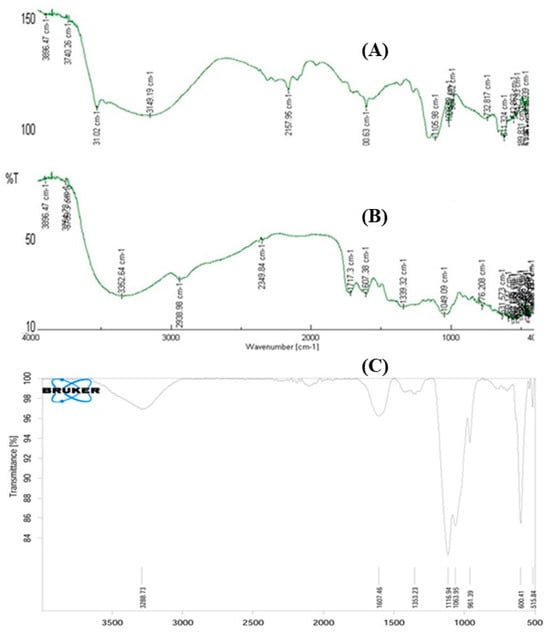

3.3.2. FTIR

FTIR analysis was carried out to identify functional groups and confirm the molecular dispersion of phytochemicals within the nanoparticles. The FTIR spectrum of pomegranate peel extract (PPE) (Figure 5, spectrum A) exhibited a strong band at 3149 cm−1, within the range of 3000–3700 cm−1, corresponding to O–H stretching vibrations of free hydroxyl groups. This confirmed the presence of flavonoids, polyphenols, and alcohols with hydrogen bonding. Additional peaks corresponding to C=O (~1700 cm−1), C=C (~1600 cm−1), and C–O–C (~1050–1100 cm−1) indicated aromatic and heterocyclic compounds, which can act as reducing and stabilizing agents. These phenolic groups are likely to bond with the ZnO surface during nanoparticle formation, functioning both as reducing and capping agents. In contrast, the FTIR spectrum of ZnSO4·7H2O (Figure 5, spectrum B) showed a broad band at 3352 cm−1 attributed to O–H stretching vibrations of crystalline water, along with strong sulfate ion absorptions at 1339 cm−1 and 1049 cm−1. Additional sulfate bending/stretching vibrations were observed at 776 cm−1, confirming the presence of hydrated sulfate groups in the precursor salt. The FTIR spectrum of PPE–ZnO nanoparticles (Figure 5, spectrum C) revealed a combination of both phytochemical signatures and Zn–O vibrations. Prominent peaks at 3288 cm−1 and 1607 cm−1 correspond to O–H and phenolic/aromatic C=C stretching, while bands at 1116, 1063, and 961 cm−1 reflected C–O vibrations from phytochemical capping agents. Importantly, new absorption bands at ~600 cm−1 and 515 cm−1 confirmed Zn–O stretching vibrations, validating the successful conversion of Zn2+ to ZnO nanoparticles. The strong feature at 1607 cm−1 is also characteristic of Zn–OH complexes, supporting the role of hydroxylated species in nanoparticle stabilization. FTIR analysis (Figure 5) demonstrated that PPE biomolecules acted as both reducing and capping agents, stabilizing the nanoparticles while ZnSO4 precursor bands disappeared after nanoparticle formation, confirming the successful synthesis of PPE–ZnO NPs. The comparative FT-IR spectra of PPE, ZnSO4·7H2O, and PPE–ZnO NPs are shown in Figure 5. The PPE spectrum exhibited a broad O–H stretching band (3000–3600 cm−1, max at 3149 cm−1), together with C=O, C=C aromatic (~1600 cm−1), and C–O/C–O–C (~1050–1150 cm−1) vibrations, consistent with the presence of polyphenols and flavonoids. In contrast, the ZnSO4 precursor spectrum displayed a broad O–H vibration from water of crystallization (~3350 cm−1) and intense sulfate ion bands at 1339, 1049, and 776 cm−1, with no phenolic features. The spectrum of PPE–ZnO NPs showed a combination of both organic and inorganic signals: retained O–H and aromatic bands at 3288 and 1607 cm−1, C–O peaks at 1116, 1063, and 961 cm−1, and, most importantly, new Zn–O stretching bands at ~600 and 515 cm−1. These spectral changes confirm the disappearance of sulfate vibrations, the persistence/shift in phenolic groups, and the emergence of Zn–O bonds, validating nanoparticle formation. The characteristic IR profile of the material in nanoparticle form is distinguished by (i) broader O–H bands due to surface hydroxyl groups and adsorbed moisture, (ii) attenuation and slight shifts in phenolic C–O and C=C bands due to coordination of PPE ligands with Zn atoms, and (iii) the diagnostic Zn–O absorption in the 400–600 cm−1 region. Mechanistically, PPE functions as a reducing and capping agent: phenolic –OH groups and enolic sites of flavonoids donate electrons, reducing Zn2+ to ZnO, while carbonyl and phenolic oxygen atoms coordinate to the nanoparticle surface, stabilizing it. This dual role explains why PPE–ZnO spectra retain organic signatures alongside new Zn–O features. Similar assignments have been reported in other studies of plant-mediated ZnO synthesis.

Figure 5.

Comparative FTIR spectra of (A) PPE, (B) ZnSO4·7H2O precursor, and (C) PPE–ZnO nanoparticles. PPE showed phenolic and aromatic functional groups, ZnSO4 exhibited characteristic sulfate vibrations, and PPE–ZnO NPs displayed both phytochemical peaks and Zn–O stretching, confirming phytochemical-mediated nanoparticle formation.

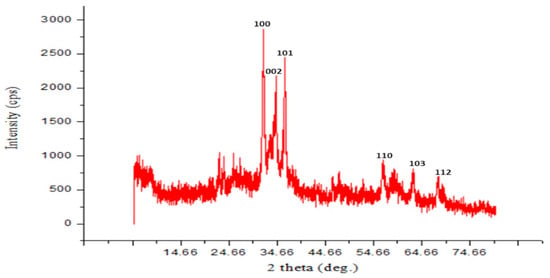

3.3.3. XRD Analysis

X-ray diffraction was used to analyze crystalline structure of zinc oxide nanoparticles that were biosynthesized using extracts from pomegranate peel.

The particles that were prepared were in the nanoscale range, as shown by the distinctive broadening of the X-ray diffraction peaks in the zinc oxide nanoparticle X-ray diffraction pattern, as seen in the figure. The spherical to hexagonal phase of ZnO with high crystallinity has been identified by the diffraction peaks at 31.8, 34.3, 36.2, 47.5, 56.4, 62.8, and 67.9°. It was found that all of these distinct peaks belonged to ZnO-NPs, and the synthesized ZnO-NPs do not contain any impurities. The crystallite diameter of zinc oxide nanoparticles was calculated using the Debye–Scherrer equation (D = Kλ/βcosθ). The diffraction peaks observed at 31.8°, 34.3°, 36.2°, 47.5°, 56.4°, 62.8°, and 67.9° were indexed to the hexagonal phase of ZnO with high crystallinity. All characteristic peaks corresponded to ZnO nanoparticles, and no impurity peaks were detected in the synthesized ZnO-NPs. Based on the Bragg’s diffraction angle (θ) and the full width at half maximum (β) of the prominent peak corresponding to the (101) plane at 36.2°, the crystallite size was estimated to be approximately 29 nm (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

XRD spectra of PPE_ZnO NPs.

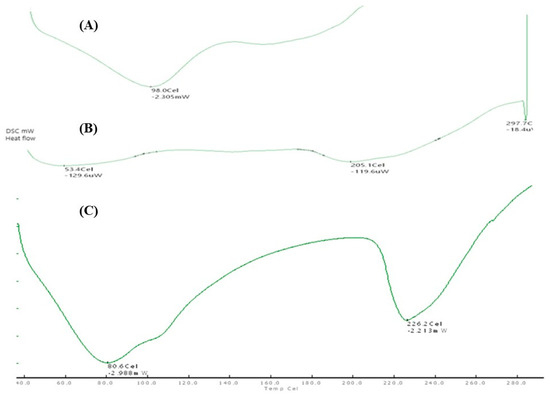

3.3.4. Differential Scanning Colorimetry

Pomegranate peel contains various organic compounds, some of which might have low melting points. An endothermic peak at 98 °C could signify the melting of such components, like certain phenolic compounds or sugars. ZnO nanoparticles may have surface hydroxyl groups (-OH) that can lose water upon heating, leading to an endothermic peak at 80 °C. A peak at 226 °C could indicate structural changes within the ZnO nanoparticles or interactions between ZnO and organic residues. The endothermic peak of PPE_ZnO NP may be associated with changes in the surface chemistry or morphology of the nanoparticles at elevated temperatures. This could involve processes such as surface restructuring, surface oxidation, or chemical reactions occurring on the nanoparticle surface. Similar thermal behavior of green-synthesized ZnO NPs was reported by Al-nehia et al. (2021), confirming that DSC provides insights into surface restructuring and stability of nanoparticles [30] (Figure 7A–C).

Figure 7.

DSC thermograms of (A) Pomegranate peel powder; (B) ZnO NP; (C) PPE_ZnO NP.

3.3.5. SEM and EDX

SEM is an effective technique for investigating material morphology and provides valuable information regarding nanoparticle size and shape. SEM images of ZnO nanoparticles synthesized using pomegranate extract revealed agglomerated, semi-spherical particles with high surface roughness. The surface morphology confirmed the agglomerated nature of the nanoparticles. SEM analysis further indicated that the nanoparticles were present as agglomerates, with average particle sizes of approximately 43.17 nm, 37.77 nm, and 26.98 nm, as shown in (Figure 4). Comparable SEM images of ZnO NPs synthesized with pomegranate and citrus peel extracts also revealed semi-spherical, agglomerated structures [26,27]. This indicates that phytochemicals influence surface morphology and aggregation. For comparison, SEM analysis was also performed on ZnO synthesized without PPE (chemical control). The plain ZnO sample showed larger, irregular agglomerates with relatively smoother surface morphology, indicating uncontrolled nucleation and growth in the absence of phytochemical capping. In contrast, the PPE–ZnO NPs exhibited semi-spherical particles with rougher surfaces and reduced aggregation, with an average particle size of 26.98–43.17 nm. These differences demonstrate the stabilizing role of PPE phytochemicals, which act as natural capping agents that restrict particle growth and minimize uncontrolled aggregation. The comparative SEM profiles thus confirm that PPE-mediated synthesis yields more uniform nanoscale features compared to chemically prepared ZnO.

Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy was employed to evaluate the elemental and chemical composition of the nanoparticles. The elemental mapping confirmed the distribution of Zn and O across the nanoparticle surface, enabling assessment of homogeneity and potential elemental segregation or clustering. EDS analysis verified the presence of zinc (Zn) and oxygen (O), the principal constituents of ZnO, confirming the successful formation of ZnO nanoparticles. The atomic percentage of oxygen was 77.01% with a weight percentage of 45.04%, whereas zinc exhibited an atomic percentage of 22.99% and a weight percentage of 54.96%. Minor additional elements were attributed to biomolecules from the pomegranate peel extract. These results indicated that the synthesized nanoparticles were obtained in a highly pure form. (Figure 8)

Figure 8.

SEM image of pomegranate peel-mediated zinc oxide nanoparticles.

EDX evaluated the elemental and chemical analysis. These maps show the distribution of Zn and O across the surface of the nanoparticles, allowing for the assessment of homogeneity and any elemental segregation or clustering. EDS analysis can confirm the presence of zinc (Zn) and oxygen (O), the primary elements comprising ZnO. The EDX of the NPs reveals formation of zinc oxide nanoparticles. The atomic weight of oxygen was 77.01%, while its present weight was 45.04%. On the other hand, the atomic weight of zinc was 22.99%, while its present weight was 54.96%, while the other minor constituents present in the ZnO-NPs were due to the presence of the peel extract of pomegranate. This indicates that the synthesized nanoparticles are in their purest form (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

EDX spectrum of pomegranate peel-mediated zinc oxide nanoparticles.

3.3.6. Size and Surface Charge Analysis

The biosynthesized PPE ZnO NPs’ average particle size and charge were determined through zeta potential analysis and dynamic light scattering (DLS). Average particle size was 194.1 nm. The polydispersity index was found to be 0.330. PDI = 0.330 indicates moderate polydispersity, consistent with a narrow-to-intermediate spread of sizes rather than a monodisperse population. The zeta potential (ζ = −18.2 mV) suggests limited electrostatic stabilization; some reversible clustering in aqueous media is therefore expected.

Dynamic light scattering (DLS) reports intensity-weighted size distributions by default, which disproportionately represent larger scatterers. We therefore provide both intensity- and number-weighted distributions (Figure 10. As expected, the intensity distribution skews to larger apparent sizes, while the number distribution shifts toward smaller sizes. This behavior reconciles the hydrodynamic size (~194 nm, DLS) with the primary particle sizes (≈26–43 nm, SEM) reported in Section 3.3.5, because (i) DLS measures the solvated hydrodynamic diameter (including adsorbed biomolecular layers) and soft agglomerates, and (ii) intensity weighting emphasizes the contribution of such larger species. Together with the ζ = −18.2 mV, these findings indicate mild agglomeration in water, which is common for phytochemical-capped ZnO NPs and consistent with the SEM-observed agglomerates. The PPE–ZnO nanoparticles displayed a zeta potential of −18.2 mV, which indicates borderline colloidal stability. This suggests that the nanoparticles may undergo mild reversible aggregation in aqueous media. Similar findings were reported by Abdelmigid et al. (2022), [26] where fruit peel-mediated ZnO nanoparticles exhibited ζ-potentials between −15 and −25 mV, reflecting moderate electrostatic stabilization. Djearamane et al. (2022) [31] also noted that phytochemical capping agents can only partially stabilize ZnO dispersions, requiring additional stabilizers for long-term formulation stability. Therefore, our observation is consistent with earlier reports and emphasizes the need for surfactants or polymeric excipients to enhance in-use stability when PPE–ZnO is incorporated into cosmeceutical products. This showed that the majority of the capping biomolecules on the biosynthesized ZnO NPs were negatively charged, resulting in electrostatic repulsion between the synthesized nanoparticles preventing them from agglomerating or aggregating in solution. (Figure 10). In the present study, the zeta potential of −18.2 mV indicates only borderline colloidal stability; this has important implications for formulation and in-use stability, as such systems may be prone to reversible aggregation during storage or upon dilution, necessitating additional stabilizers (e.g., polymers, surfactants) or optimized formulation strategies to ensure long-term performance. Our findings indicate that the PPE–ZnO NPs display a borderline ζ-potential (−18.2 mV), which is below the ±30 mV threshold commonly cited as indicative of robust colloidal stability. This limited surface charge likely contributed to the observed hydrodynamic size (~194 nm), which is substantially larger than the primary particle dimensions (26–43 nm, SEM) due to reversible aggregation in aqueous suspension. Similar trends have been reported in peel-mediated ZnO systems, where ζ-potentials between −15 and −25 mV correlated with hydrodynamic diameters of 150–250 nm (Abdelmigid et al., 2022; Djearamane et al., 2022) [26,31]. Compared to these reports, our values fall within the expected range for phytochemical-capped ZnO nanoparticles, underscoring the role of phenolic/flavonoid capping agents that provide partial but not complete electrostatic stabilization. To achieve long-term dispersion stability, additional strategies such as surfactant incorporation, polymeric coatings, or pH optimization may be required. These insights highlight that while our PPE–ZnO NPs are suitable for short-term biological assays, formulation adjustments will be essential for translational cosmeceutical applications.

Figure 10.

DLS and ζ-potential of PPE–ZnO NPs. (A) Intensity-weighted hydrodynamic size distribution (DLS) showing a main mode consistent with mild agglomeration in aqueous media andnumber-weighted distribution from the same data, highlighting the underlying smaller population; (B) ζ-potential distribution (mean −18.2 mV). Note: Intensity weighting emphasizes larger scatterers; number weighting better reflects the population count of smaller primary particles.

3.3.7. Antibacterial Activity of ZnO Nanoparticles

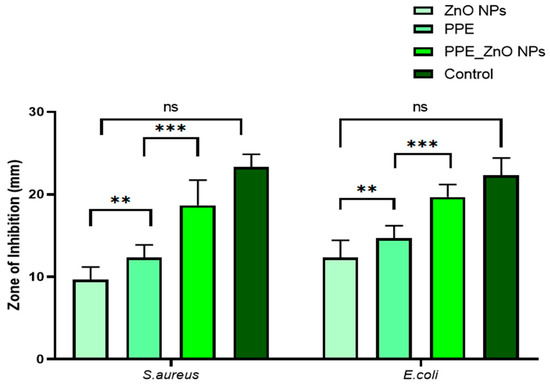

The in vitro antibacterial efficacy of PPE_ZnONPs was evaluated in a broad spectrum of pathogenic bacteria, including Staphylococcus aureus and E. coli. In this study, the antibacterial activity of synthesized ZnONPs against Gram-positive (Staphylococcus aureus) and Gram-negative (E. coli) bacteria were conducted using the agar well diffusion method. Tetracycline was used as a positive control against all tested bacterial strains (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Antibacterial activity of ZnO NPs.

At higher concentrations (10 μg/mL), the synthesized ZnO nanoparticles (ZnO-NPs) exhibited enhanced antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus. This could be attributed to the Gram-positive nature of S. aureus, which possesses a thick peptidoglycan layer that facilitates ZnO-NP penetration and subsequent growth inhibition, ultimately leading to cell death. Previous studies have reported that this structural feature may allow ZnO-NPs to disrupt the bacterial cell wall more effectively. In contrast, Gram-negative bacteria such as Escherichia coli, which contain lipopolysaccharides in their outer membrane, may initiate a counter-defense, making them comparatively less susceptible.

The inhibition zone diameters observed ranged from 9–19 mm for S. aureus and 8–17 mm for E. coli. Our inhibition zones (S. aureus: 9–19 mm; E. coli: 8–17 mm) align with prior reports on green ZnO synthesized using fruit-peel matrices. For example, ZnO derived from orange peel showed robust activity against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative strains under comparable agar-well diffusion conditions [21], while pomegranate-derived systems similarly reported stronger inhibition toward Gram-positive organisms, consistent with our S. aureus > E. coli trend [26,29]. In PPE-functionalized ZnO nanocomposites, phenolic capping layers (ellagic acid, gallic acid, quercetin, etc.) have been implicated in enhancing bacterial growth suppression relative to bare ZnO [19]. Collectively, these studies support our observation that peel-mediated ZnO exhibits antibacterial efficacy within the same magnitude range and bacterial susceptibility pattern as previously documented. The antibacterial activity of ZnO-NPs may be explained by multiple mechanisms, including: (i) generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS); (ii) electrostatic attraction and attachment of ZnO-NPs to microbial cell walls, leading to oxidative stress; (iii) mechanical disruption of the bacterial membrane due to nanoparticle penetration; and (iv) release of Zn2+ ions and formation of reactive oxygen molecules. Among the tested strains, S. aureus consistently showed greater susceptibility to ZnO-NPs than E. coli at all concentrations tested. Our results are consistent with Abdelmigid et al. (2022), who reported ZnO NPs synthesized using fruit peel extracts exhibited higher activity against Gram-positive bacteria than Gram-negative strains [26]. The antibacterial action of ZnO NPs is widely ascribed to multimodal mechanisms: (i) ROS generation (•OH, O2•−, 1O2) causing oxidative damage to membranes, proteins, and DNA; (ii) electrostatic adhesion of negatively/positively charged NP surfaces to the bacterial envelope, promoting local ROS stress and permeability changes; (iii) physical membrane perturbation/penetration by nanoscale particulates; and (iv) Zn2+ ion release, which disrupts enzyme function and homeostasis [20]. Peel-derived phytochemicals adsorbed on ZnO can further promote surface interactions and stabilize dispersion, improving the local contact with bacterial cells and explaining the observed enhancement vs. plain ZnO in our study [19,21]. The consistently greater susceptibility of S. aureus than E. coli is also mechanistically plausible: the thicker peptidoglycan layer in Gram-positive bacteria can favor NP binding and penetration, whereas the LPS-rich outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria offers an additional barrier and detox response, reducing net susceptibility. In conclusion, ZnO-NPs synthesized using pomegranate peel aqueous extract demonstrated superior antibacterial properties compared to plain ZnO, particularly against S. aureus and E. coli. This enhanced efficacy was attributed to the synergistic effect of the intrinsic antibacterial activity of ZnO-NPs combined with bioactive phytochemicals from the pomegranate peel extract (Figure 12). Thus, our zone-of-inhibition profile and strain selectivity mirror published peel-mediated ZnO reports and are consistent with the accepted multimodal ZnO antibacterial mechanisms.

Figure 12.

Antibacterial activity of ZnO NPs. All values are expressed as mean SEM, n = 6 by using Two Way ANOVA followed by multiple comparison test., ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, ns: Non-Significant.

3.3.8. Antioxidant Activity- DPPH Radical Scavenging Activity

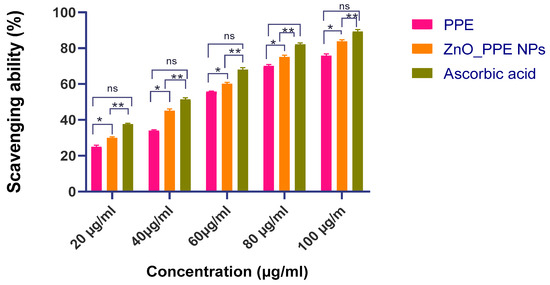

The DPPH assay is a widely used method for evaluating the free radical scavenging ability of nanoparticles. In this study, ZnO nanoparticles synthesized using Punica granatum peel extract (PPE–ZnO NPs) were compared with ascorbic acid as a standard antioxidant (Figure 13. At 100 μg/mL, PPE–ZnO NPs exhibited strong radical scavenging activity (83.8%), which can be attributed to phytochemicals such as gallic acid, ellagic acid, punicalagin, anthocyanins, rutin, and quercetin acting as capping agents. Antioxidant activity was assessed primarily for PPE–ZnO nanoparticle dispersions, while PPE alone was also tested under identical conditions as a control to establish baseline activity (Figure 13). Samples were prepared in methanol at concentrations of 25, 50, 100, 150, and 200 µg/mL. Each sample (1 mL) was mixed with 1 mL of 0.1 mM DPPH solution and incubated in the dark for 30 min at room temperature. Absorbance was measured at 517 nm against a methanol blank. Ascorbic acid was included as a standard antioxidant. The percentage inhibition was calculated as [(Acontrol − Asample)/Acontrol] × 100, and IC50 values were derived by non-linear regression analysis using GraphPad Prism 10.6.1. Although PPE–ZnO NPs exhibited slightly lower IC50 values (52.91 µg/mL) compared to PPE (56.2 µg/mL), the difference is modest and may not be statistically significant. Therefore, while both fall within the ‘strong antioxidant’ category, the advantage of PPE–ZnO NPs lies in the potential synergistic mechanism rather than absolute IC50 reduction. The phytochemicals from PPE act as surface capping agents that enhance ROS-scavenging in tandem with the intrinsic redox activity of ZnO. Moreover, when integrated into nanoscale form, PPE–ZnO NPs exhibit multifunctionality combining antioxidant activity with UV-protective and antimicrobial properties—which provides added value for cosmeceutical applications compared to PPE alone.

Figure 13.

DPPH scavenging activity comparison between PPE_ZnO NPs, PPE and Ascorbic acid. All values are expressed as mean SEM, n = 6 by using Two Way ANOVA followed by multiple comparison test. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, ns: Non-Significant.

The antioxidant activity of ZnO nanoparticles (ZnO-NPs) produced from aqueous pomegranate peel extract (PPE) was evaluated using the DPPH radical scavenging assay. A synergistic effect between PPE and ZnO-NPs was observed, as radical scavenging activity increased significantly with higher concentrations, suggesting that PPE phytochemicals contributed substantially to the antioxidant potential. As shown in Table 3, PPE–ZnO NPs exhibited an IC50 of 52.91 ± 0.30 µg/mL, which was slightly lower than PPE alone (56.2 µg/mL) and approached the standard ascorbic acid (35.1 µg/mL). These results demonstrate that incorporation of PPE bioactive into ZnO NPs enhances their antioxidant efficiency. Comparable IC50 values (50–60 µg/mL) were reported by Djearamane et al. (2022) [31] for fruit peel-mediated ZnO nanoparticles, while Ifeanyichukwu et al. (2020) [29] showed that polyphenol-rich extracts significantly reduce IC50 values relative to chemically synthesized ZnO. Similarly, Abdelmigid et al. (2022) [26] highlighted that peel-derived ZnO nanoparticles exhibit stronger antioxidant activity than bare ZnO due to synergistic capping effects of bioflavonoids. Taken together, these observations justify our findings and suggest that ellagic acid, gallic acid, and quercetin present in PPE contribute to the enhanced radical scavenging efficiency of PPE–ZnO NPs. The antioxidant potential of these nanoparticles is particularly relevant for cosmeceutical applications, where neutralization of reactive oxygen species plays a critical role in preventing oxidative skin damage and premature aging [26]. The antimicrobial activity of PPE–ZnO NPs may also indirectly contribute to their anti-aging efficacy. Chronic microbial colonization of skin accelerates wrinkle formation by inducing oxidative stress, inflammatory cytokines, and matrix metalloproteinase activity. ZnO NPs exert antibacterial effects through Zn2+-mediated membrane disruption and ROS generation, while phytochemicals such as ellagic acid and quercetin provide additional antioxidant and anti-inflammatory protection. This dual mechanism not only reduces microbial burden but also minimizes inflammation-driven extracellular matrix degradation, thereby linking antimicrobial action with improved photoprotection and anti-aging benefits.

Table 3.

shows antioxidant activity for ZnO NPs synthesized from P. granatum peel extract.

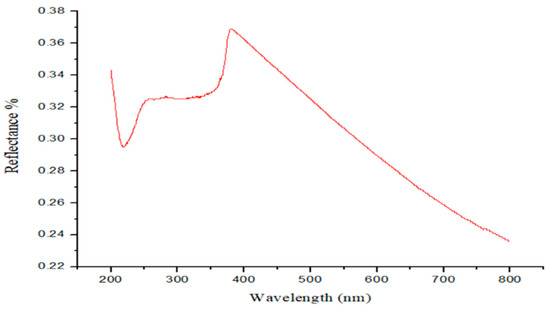

3.3.9. Optical Properties and Sun Protection Factor Performance of ZnO NPs

Spectroscopic analysis was employed to investigate the optical properties of the ZnO nanoparticles, as particle size is a critical factor influencing the overall material characteristics. The UV–visible diffuse reflectance spectrum of ZnO NPs exhibited very low reflectance across the UV region (280–370 nm), which encompasses the complete UV-B range (280–320 nm) and part of the UV-A range (320–372 nm). The nanoparticles exhibited strong UV absorption with an intense absorption peak observed between 200 and 370 nm, corresponding to very low diffuse reflectance. Typically, ZnO nanoparticles display a characteristic absorption peak, known as ‘band-gap absorption’ or ‘band-edge absorption,’ in the UV region at approximately 375 nm. This band-gap absorption arises from the excitation of electrons from the valence band to the conduction band. (Figure 14). ZnO–PPE NPs function predominantly as physical sunscreens, attenuating UV radiation by reflecting and scattering, while also exhibiting chemical absorption at the UV band edge due to their nanoscale size and band-gap transitions. The strong absorption observed in Figure 11 (200–370 nm, with band-gap absorption near 375 nm) confirms their role as UV absorbers, validating their SPF performance. Thus, ZnO–PPE NPs combine dual mechanisms: (i) physical blocking typical of ZnO particles and (ii) chemical absorption enhanced by their nanostructure and PPE phytochemical capping. The inclusion of Figure 11 is therefore significant, as it provides spectroscopic evidence that the nanoparticles not only scatter UV radiation but also absorb it effectively, supporting their multifunctional photoprotective role.

Figure 14.

Optical properties of ZnO NPs: a) UV–visible diffuse reflectance spectra of ZnO NPs.

The parameters (EE(λ) × I(λ)) required for determining the sun protection factor (SPF) values are presented in Table 4, and the in vitro SPF of ZnO nanoparticles was obtained using the Mansur method.

SPF in vitro = CF × λ = 290∑320 EE(λ) × I(λ) × abs(λ)

Table 4.

Determination of sun protection factor.

ZnO NPs SPF value (SPF = 29.8) indicated their strong probable as sunscreen agents in caring the skin against harmful UV radiation. Sunscreens with SPF ≥ 15 are considered to be operative in avoiding sunburn and reducing the risk of skin cancer and premature aging as per FDA guidelines. Therefore, ZnO NPs synthesized with PPE can be regarded as promising candidates for incorporation into formulations for sunscreen along with various personal products. Previous studies have shown ZnO NPs with SPF values above 15 are effective for UV protection; our SPF 29.8 aligns with Elbrolesy et al. (2023), confirming photoprotective efficacy [35]. For comparative analysis, SPF values were also determined for PPE alone, chemically synthesized ZnO (no-PPE control), and bulk ZnO powder under identical conditions. Among these, PPE–ZnO NPs exhibited the highest SPF (29.8), compared with lower SPF values for PPE (<10) and bulk ZnO (∼15). The no-PPE ZnO control showed intermediate SPF performance, confirming that PPE-mediated synthesis enhanced UV absorption and photoprotective efficacy. This comparative data demonstrates that the synergistic contribution of PPE phytochemicals and nanoscale ZnO morphology provides superior photoprotection compared to extract or bulk ZnO alone.

3.3.10. In Vitro Anti-Aging Activity

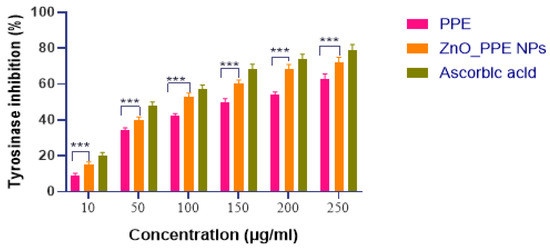

Anti-Tyrosinase Activity

The aqueous extract of pomegranate peel (PPE) (10–200 µg/mL) exhibited tyrosinase inhibitory activity in dose-dependent style. Inhibitory effect for PPE–ZnO NPs was greater than that of PPE alone at all tested concentrations, but lower than that of ascorbic acid (80%). The enhanced activity can be attributed to bioactive compounds present in PPE, including gallic acid, ellagic acid, rutin, and quercetin, which are known tyrosinase inhibitors (Figure 15).

Figure 15.

Effect of aqueous extract of Punica granatum &PPE_ZnO NPon tyrosinase activity using ascorbic acid as substrate. All values are expressed as mean SEM, n = 6 by using Two Way ANOVA followed by multiple comparison test *** p < 0.001, ns: Non-Significant.

When combined with ZnO NPs, these compounds may exhibit stronger inhibitory effects due to their increased local concentration at the enzyme’s active site and improved stability. Phenolic compounds and flavonoids present in PPE can bind to the copper ions at the active site of tyrosinase, which are necessary for its enzymatic activity. This binding may lead to a decrease in the enzyme’s ability to convert tyrosine to melanin, thereby diminishing or inhibiting its catalytic activity.

The tyrosinase inhibitory activities of both the aqueous extract of pomegranate peel (PPE) and the PPE_ZnO nanoparticles (NPs) were observed to increase with rising concentrations. Within the tested concentration range of 10–250 µg/mL, the tyrosinase inhibition for the aqueous extract varied between 9–63%, while the PPE_ZnO NPs exhibited a higher inhibition range of 15–72%. These results suggest that the ZnO nanoparticles synthesized from pomegranate peel extract possess significantly enhanced tyrosinase inhibitory activity compared to the extract alone. This superior activity can be explained by the nanoscale features and surface chemistry of ZnO NPs. The nanoparticles provide a high surface-to-volume ratio, which allows efficient adsorption and presentation of PPE-derived polyphenols (such as ellagic acid, gallic acid, and quercetin) at the enzyme interface. Zn2+ ions at the ZnO surface can further interact with tyrosinase active sites or promote redox cycling, thereby enhancing inhibition relative to the extract alone. In addition, the nanostructure facilitates improved cellular uptake and local concentration of bioactive phytochemicals, leading to synergistic enhancement of tyrosinase inhibition. Ascorbic acid, used as a reference standard, demonstrated excellent tyrosinase inhibitory activity at 79%. The tyrosinase inhibition exhibited by the PPE_ZnO NPs formulation was 72%, which is comparable to the reference standard and statistically significant (p < 0.0001). This highlights effective inhibitory outcome of the synthesized nanoparticles on tyrosinase, contributing to their potential as effective agents in anti-hyperpigmentation treatments. It should be noted that anti-tyrosinase activity primarily reflects inhibition of melanogenesis and does not fully capture anti-aging potential. Additional enzymatic targets such as elastase, collagenase, and hyaluronidase are directly involved in skin wrinkling, collagen degradation, and loss of elasticity. These assays were not performed in the current study, which represents a limitation. Future studies will incorporate these enzymatic evaluations to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the anti-aging properties of PPE–ZnO NPs.

3.3.11. In Vivo Study

Evaluation of UV Induced Photodamage

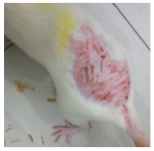

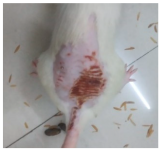

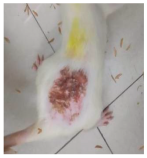

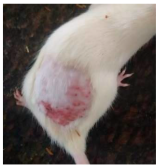

Across 42 days of UVB challenge, macroscopic assessment of the dorsal skin revealed clear group-wise differences in wrinkle onset and severity. In the UVB control (Group II), fine lines were visible by Day 15 and progressed to coarse, deeply etched wrinkles with surface roughness and dryness by Days 30–42, confirming successful photoaging induction under the stated irradiation conditions (290–320 nm, peak 312 nm). In contrast, the marketed anti-wrinkle cream (Group III) attenuated wrinkle depth and density, yielding visibly smoother dorsal skin compared to the UVB control. The PPE-only group (Group IV) produced a moderate protective effect (fewer coarse furrows and reduced dryness), whereas the PPE–ZnO NP formulation (Group V) showed the most pronounced macroscopic improvement—shallower wrinkle profiles and more uniform skin texture, consistent with photoprotection. These visual outcomes are congruent with our in vitro SPF data (SPF = 29.8), which exceeds the FDA effectiveness threshold (SPF ≥ 15) and implies robust attenuation of erythemogenic UV-B. Furthermore, the macroscopic protection aligns with histopathology, where PPE–ZnO NPs preserved dermal collagen architecture and reduced mean epidermal thickness by ~69% relative to UVB controls. These protective effects are consistent with findings by Shanbhag et al. (2019) [5], who showed that ZnO formulations derived from botanical extracts reduced UV-induced photoaging biomarkers, and with Abdelmigid et al. (2022) [26], who reported that green ZnO NPs preserved collagen density under UV stress. Taken together, these results indicate that dual protection—optical UV filtering by ZnO (broad UV absorption/low reflectance in the 280–370 nm window) combined with the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory potential of PPE polyphenols—translates into a visible anti-photoaging effect in the rat UVB model. The concordance between SPF performance, macroscopic wrinkle outcomes, and histological preservation strengthens the case for PPE–ZnO NPs as a photoprotective cosmeceutical candidate. While macroscopic wrinkle progression and histopathological features were documented, no formal wrinkle severity or histological scoring system was applied. Instead, validated quantitative surrogate endpoints such as SPF values, DPPH IC50 antioxidant data, and the percentage reduction in epidermal thickness (~69%) were used to support the findings. Future work should incorporate standardized wrinkle grading scales, histological scoring methods, or digital image analysis to provide more robust quantitative assessment as shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

The images shows the wrinkles on skin induced through UV irradiation against tropically applied formulation.

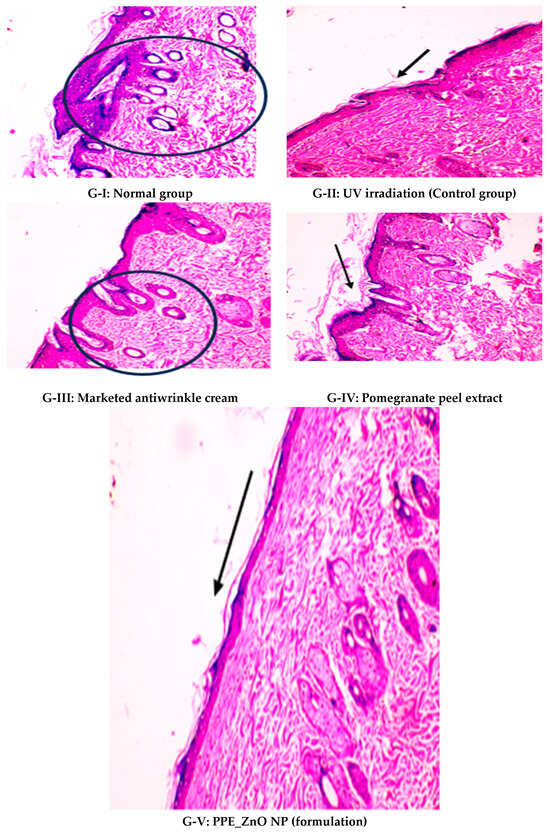

Histopathology