Abstract

The rapid growth of digital technology has fundamentally reshaped the entrepreneurial landscape, giving rise to complex digital entrepreneurial ecosystem. While digital entrepreneurship is often presented as a means of empowering women, its actual impact remains debated. By integrating social role theory (SRT), this study constructs and applies an integrated Gender–Technology–Entrepreneurship (GTE) framework. Through a grounded theory (GT) analysis of in-depth interviews with seven Chinese women digital entrepreneurs, this study examines the dual role of digital technology in simultaneously enabling and constraining their enterprises. Our findings reveal that digital technology functions as both an empowerment amplifier and a constraint mechanism. We further identify digital private domain entrepreneurship (DPDE) as a strategic adaptation. It involves constructing sustainable sub-ecosystems by leveraging privatized user relationships and emotional capital. This study contributes to a nuanced understanding of the dynamic interplay between gender, technology, and entrepreneurship. It also offers practical insights for entrepreneurs and policymakers aiming to foster sustainable digital ecosystems.

1. Introduction

Driven by advances in artificial intelligence (AI) and the platform economy, the digital technology revolution is not merely introducing new tools but also generating complex, interconnected digital entrepreneurial ecosystem. These ecosystems consist of a dynamic network of actors, institutions, and technologies that interact nonlinearly [1]. Within them, digital technology has profoundly reshaped the nature of uncertainty in entrepreneurial processes and outcomes. Consequently, it alters the core of innovation and entrepreneurship and generates significant transformations in traditional entrepreneurial models [2]. It thereby drives the boundary of entrepreneurial activities from originally discrete, stable, and enclosed states toward an increasingly permeable, fluid, and dynamic direction. Digital entrepreneurship is expanding across various sectors [3] and presents women entrepreneurs with unprecedented opportunities [4]. Women entrepreneurs operate within this digital entrepreneurial ecosystem not as passive recipients, but as adaptive agents. Their strategies and decisions interact with technological affordances and structural constraints. Therefore, understanding their entrepreneurship requires moving beyond examining isolated factors toward adopting a theoretical lens that can capture these systemic relationships. That is, the dynamic, recursive interactions between gendered structures, digital platform architectures, and entrepreneurial agency. These interactions collectively shape pathways to empowerment and constraint, and ultimately to sustainable venture outcomes.

Some scholars argue that digital entrepreneurship, characterized by flexible working hours, reduced commute requirements, and lower business costs, may better enable women to mitigate work–family conflict [5,6]. Furthermore, its lower entry barriers facilitate entrepreneurial development. This levels the entrepreneurial landscape for women and marginalized groups, potentially increasing entrepreneurial intentions [7]. Additionally, digital entrepreneurship is argued to diminish gender discrimination within traditional financial environments, decrease financial exclusion, and improve women’s access to financing [8,9,10].

However, traditional constraints faced by women entrepreneurs have not been fundamentally eliminated. Instead, they may encounter new challenges as digital technology penetrates more widely. For instance, the gender digital divide has emerged as a new constraint on female entrepreneurship. The development of digital technology has not created a level playing field for women entrepreneurs, and significant gender disparities persist in digital entrepreneurial practices [11,12]. Furthermore, real-world gender inequalities are similarly reproduced or even amplified in digital spaces [13], leading women to potentially face greater cultural, economic, and social challenges in the process of digital entrepreneurship [14]. Meanwhile, digital technology has also failed to help women effectively alleviate work–family tension. While digital media removes traditional physical and temporal barriers, it also deeply embeds workspaces within the home environment. It makes entrepreneurial activities a persistent and highly demanding presence, thereby exacerbating role conflict [7]. These difficulties significantly affect women’s motivation to pursue entrepreneurship and their entrepreneurial outcomes.

In summary, the existing literature offers a foundational yet fragmented understanding, often cataloging the benefits and drawbacks of digital entrepreneurship for women in parallel. However, it falls short of capturing the simultaneous and dynamic nature of their lived experience. This fragmented view inevitably obscures a critical question: Is digital technology a straightforward tool for empowerment conceptualized as the enhancement of women’s agency, resource access, and entrepreneurial success; or does it simultaneously reconstruct traditional constraints in more subtle, systemic forms? In other words, has the widely promoted narrative of “digital technology empowerment” been somewhat mythologized, thereby obscuring its practical complexities and limitations? Admittedly, the rapid development of digital technology is reshaping traditional understandings of entrepreneurship. But its complex relationship with gendered structures remains incompletely understood. Technology itself does not inevitably bring about equality. When applied within a society still characterized by gender bias, it may serve as a tool to break traditional barriers or evolve into a new form that deepens gender disparities. Therefore, it is essential to move beyond a simplistic “good-or-bad” dichotomy and instead focus on how digital technology interacts with gendered conditions across ecosystems. This focus will help shape concrete pathways for female entrepreneurship [15].

To address this gap, this study employs a grounded theory (GT) methodology and integrates social role theory (SRT) to develop a Gender–Technology–Entrepreneurship (GTE) framework. We conducted an in-depth exploration of the lived experiences of seven Chinese women digital entrepreneurs. By analyzing their experiential narratives, we seek to answer the pivotal question derived from our problematization: How does digital technology operate as both an instrument of empowerment and a vehicle for reconstructing constraints? Specifically, the study investigates: (1) How do systemic interactions within the digital entrepreneurial ecosystem create simultaneous pathways of both empowerment and constraint for women entrepreneurs? (2) What adaptation strategies do these entrepreneurs enact to navigate and negotiate this duality? Clarifying this issue not only enhances our understanding of the real relationship between digital technology and female entrepreneurship but also provides valuable insights for formulating effective support policies. Only by transcending the simplistic notion that “technology necessarily brings liberation” can we better support female entrepreneurial development in the digital entrepreneurial ecosystem. This study advances the theoretical understanding of how digital technology mediates female entrepreneurship. It also offers critical insights for designing more equitable and effective digital entrepreneurial ecosystem.

2. Theoretical Background and Framework

2.1. Digital Entrepreneurship Ecosystem in China

The digital entrepreneurial ecosystem in China exhibits distinct characteristics shaped by a unique interplay of state governance, platform management, and socio-cultural contexts. It collectively differentiates it from Western models and critically informs entrepreneurs’ experiences [16].

First, the Chinese government plays a constitutive and paradoxical role. Unlike ecosystems primarily driven by private markets, the Chinese government actively orchestrates development through a dual strategy of enabling infrastructure and strategic constraint. Foundational policies have dramatically reduced information costs and spurred entrepreneurial activity by enhancing connectivity and knowledge spillovers [17]. At the same time, systematic support provides direct momentum for digital startups, including tax incentives, talent programs, and local industrial funds [16]. However, this facilitative role is coupled with an assertive regulatory regime that imposes significant adaptation pressures on ventures [18].

Second, China’s digital entrepreneurial ecosystem is organized around domestic “super-platforms” such as Alibaba, Tencent, and ByteDance. This structure gives rise to a pervasive logic of “platform-dependent entrepreneurship”. These platforms provide indispensable infrastructure, such as payment systems, logistics, cloud services, and large user bases. These significantly lower entry barriers and accelerate innovation. However, this dependency establishes profound power asymmetries. The viability of enterprises may hinge heavily on platform governance rules, algorithmic changes, and competitive practices. This profound dependence effectively embeds entrepreneurs within a hierarchy controlled by platform interests [19].

Third, the individual agency and self-organizing dynamics of entrepreneurs are accentuated by profound regional and demographic disparities. The ecosystem is geographically stratified, with global hubs such as Beijing and Shenzhen concentrating venture capital and talent. In contrast, grassroots digitalization in lower-tier cities and rural areas often follows a necessity-driven, socially embedded model. For example, Taobao Villages and Douyin livestreaming commerce are spurred by poverty alleviation initiatives [20]. This stratification highlights how resource access is unevenly mediated by location and social networks. Crucially, gender intersects with these structures in distinct ways.

2.2. Digital Entrepreneurship of Women Entrepreneurs

Digital entrepreneurship is regarded as a potential direction for women due to its anticipated benefits at two levels. At the individual level, it offers unique work flexibility [4,21], enabling women to balance familial and professional roles through remote work [7]. Furthermore, it supports self-managed schedules, reduces commuting, and can yield quicker returns with lower initial investment [6]. It also helps overcome structural constraints imposed by traditional gender roles [22]. Specifically, women’s participation in e-commerce can alter socio-economic subordination in patriarchal and rural settings [8]. This empowerment improves their economic standing and family relations, and also contributes to addressing broader social issues, such as those involving left-behind children. Low-barrier platforms such as Taobao stores have enabled rural women to enter previously male-dominated sectors, and digital technology further empowers them to address multidimensional challenges [23].

At the business level, digital entrepreneurship offers women distinct comparative advantages. First, it features relatively low entry barriers, typically requiring no physical premises or expensive equipment, and relies on flexible operations and widely accessible digital skills [4,14]. The internet also facilitates real-time knowledge sharing and continuous learning within women-led entrepreneurial teams [24]. Second, digital technology supports the end-to-end entrepreneurial process, from market research and cost reduction to building global networks through social media [2,5,25]. Notably, the internet eliminates gender discrimination in online financial services, creating a more equitable financing environment for women entrepreneurs [26].

Despite its empowering potential, the digital economy may reproduce or even amplify existing gender inequalities. Digital technologies often fail to foster a level playing field. Instead, they introduce new systemic constraints that intersect with traditional barriers. This intersection puts women at risk of marginalization in digital entrepreneurial ecosystem. Structural hurdles, including gender discrimination, the digital divide, financial exclusion, and limited digital skills, continue to impede women’s full participation and development [27,28].

Firstly, insufficient professional and digital skills are key constraints for women entrepreneurs. Those in developing and less developed regions frequently miss out on digital dividends due to capability deficits [29]. Educational gaps, economic burdens, sociocultural biases, and low enrollment in Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics (STEM), and Information and Communication Technology (ICT) fields further limit women’s access to digital resources and foundational development. Additionally, women’s lower frequency of using digital tools for business purposes widens the gender digital divide.

Secondly, gender stereotypes persist in digital entrepreneurship. Dy, Marlow and Martin [7] observe that offline gender barriers are replicated or even amplified in online contexts. For instance, Chinese women digital entrepreneurs still face significant structural barriers when entering male-dominated sectors and constructing entrepreneurial identities [30]. In many regions, women entrepreneurs are pressured to adopt “masculine” behaviors to gain acceptance [4,7,30,31,32]. Male-dominated social norms and traditional gender role expectations thus constrain women’s participation modes and opportunities in the digital economy.

Finally, digital entrepreneurship has not effectively mitigated women’s work–family conflicts. Marlow [33] argues that the notion that home-based entrepreneurship effortlessly balances domestic and professional life is overly simplistic. Conversely, digital media embeds work within the home, eroding traditional physical and temporal boundaries and blurring work–life divisions. As women remain primary bearers of unpaid household and care labor, their working hours extend without relief from domestic responsibilities. This purported “balance” not only fails to alleviate role conflict but may exacerbate women’s physical and psychological burdens.

In conclusion, existing research adopts a dichotomous lens, enumerating women’s distinct advantages and disadvantages in digital entrepreneurship. However, they overlook the dynamic interplay between empowerment and constraint in their lived experiences. To move beyond static lists, this study aims to address this gap by constructing an integrated theoretical framework that models the complex interactions among gender norms, platform architectures, and entrepreneurial agency.

2.3. Social Role Theory (SRT)

Social Role Theory (SRT) is a social psychological theory that explains the emergence and dynamics of social psychology, behavior, and phenomena based on individuals’ social role attributes [34,35]. The concept of “role” originated as a theatrical term and was first adopted by the American sociologist George Herbert Mead for the analysis of sociological behavior [36]. Linton [37] formally introduced the concept of the “social role”, positing that an individual’s role is a culturally prescribed set of rights and obligations corresponding to their status, and that role enactment must conform to societal scripts.

Some scholars argue that society comprises interconnected status positions where individuals enact role-based behaviors. Each status position carries specific behavioral expectations. For instance, Schuler et al. [38] define SRT as a conceptual framework that links organizational attributes to individuals, thereby facilitating the exploration of individual attitudes and perceptions within organizations. Other scholars emphasize that roles emerge dynamically through interaction, requiring theoretical frameworks that capture these interactional processes. Biddle [34], for example, argues that the core proposition of SRT is that the social roles individuals occupy influence their self-perceptions and simultaneously shape their behavioral patterns. Consequently, each social role entails defined behavioral expectations, including norms of conduct, communication, and appearance. When adopting a social identity, individuals encounter role-based expectations from others that shape their behavior. Furthermore, the demands imposed by a social role are often specific, particular, and fragmented. It dictates how one should behave in various concrete situations to meet role requirements. Although scholars may hold nuanced interpretations of SRT, their perspectives consistently address the norms and expectations associated with specific social statuses or identities. Therefore, it is generally accepted that a social role represents a behavioral pattern structured by social position and societal expectations. It reflects multidimensional social attributes and underlies the formation of social groups [39,40].

According to SRT, perceivers develop group stereotypes through role-based social cognition [39]. Gender may lead to differences in social behavior by influencing both societal role expectations and individuals’ own beliefs or skills [41]. Specifically, by observing the social roles of men and women, men are stereotyped as possessing agency, characterized by goal pursuit, task orientation, and an emphasis on confidence and competence. Conversely, women are stereotypically perceived as possessing communion, characterized by relationship maintenance, a desire for belonging, and an emphasis on warmth and morality [42]. Society imposes stronger work-role expectations on men and family-role expectations on women. Consequently, individuals typically enact gender-distinct role behaviors [43]. However, when individuals appear in contexts incongruent with their stereotyped roles or exhibit behaviors inconsistent with those roles, the perceiver’s held stereotypes may gradually change. Therefore, from the perspective of SRT, women entrepreneurs constantly navigate the tension of social role expectations. On one hand, as regulated objects, they bear the role expectations imposed by various stakeholders throughout their entrepreneurial journey, including employees, clients, investors, and family members. On the other hand, as objects of perception, they engage in ongoing interactions with these stakeholders. Through these interactions, they continually scrutinize, negotiate, and reshape their understanding of role stereotypes. This process thereby gradually adjusts and shapes their entrepreneurial behaviors [44].

More specifically, Chinese society is deeply influenced by Confucian values, which reinforce traditional gender stereotypes through a patriarchal foundation [45]. These values assign women the primary role of caregivers and homemakers, an ideal captured in the concept of the “virtuous wife and caring mother”. And it also marginalized their roles in business and public life. These expectations are perpetuated through family, education, and media, creating a persistent role script that shapes women’s self-perception and entrepreneurial paths [46,47]. As objects of these social expectations, women entrepreneurs often encounter an inequitable environment. In China, society places a high value on interpersonal relationships (Guanxi) [48,49], which differs from practices in Western societies. Within such a relational context, individuals with greater access to social resources tend to be more entrepreneurial and achieve higher success rates [50,51]. However, constrained by culture, institutions, and gender stereotypes, women are perceived to have lower social capital. They typically lack initial business networks and have fewer opportunities to build professional connections than men [52,53,54]. This structural disadvantage suppresses their entrepreneurial frequency and scale. Single women entrepreneurs in China even face stigma and social penalties, further restricting their social capital and networks [55]. Similarly, as perceiving subjects, women internalize these gendered expectations, which affect their decision-making and legitimacy. Research shows that a significant gender gap exists in how entrepreneurs perceive China’s institutional environment. Women entrepreneurs often hold more negative views of the regulatory system, linked to their exclusion from political networks and key economic activities [56]. Furthermore, the gender-role orientation of Chinese women entrepreneurs shapes their perceptions of organizational and institutional legitimacy, influencing their strategic choices and operational models [57]. In general, social role expectations exert a profound influence on female entrepreneurship in China, both by imposing external entrepreneurial pressures and by shaping the internal perceptions that guide their strategic actions.

2.4. Gender–Technology–Entrepreneurship (GTE) Theoretical Framework

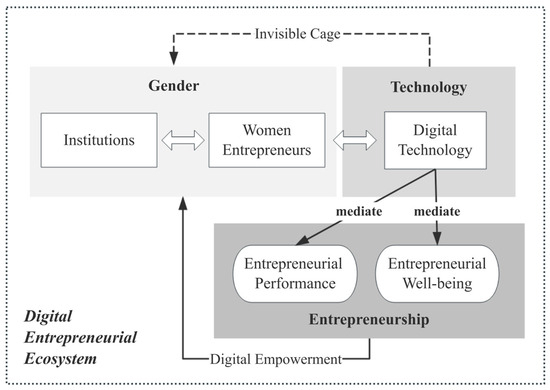

Although existing research has revealed the double-edged sword effect of digital technology, it often fails to explicate the dynamic, systemic interactions among gender norms, technological affordances, and entrepreneurial behavior. To theoretically integrate these elements, we conceptualize them as core components of a digital entrepreneurial ecosystem within our research theoretical framework. It allows us to model their interactions and potential feedback mechanisms conceptually. Therefore, building on SRT, this study constructs a Gender–Technology–Entrepreneurship (GTE) framework (Figure 1) and examines how micro-level adaptive behaviors give rise to macro-level patterns, while also considering the normative shaping of the digital entrepreneurial landscape by the slowly evolving parameter of social gender structures.

Figure 1.

Gender–Technology–Entrepreneurship (GTE) Theoretical Framework.

3. Method and Data

3.1. Method

Grounded Theory (GT), originating in sociology, is a qualitative research methodology rooted in pragmatism and symbolic interactionism [58,59]. It advocates for theory discovery directly from empirical data. Through the systematic analysis and coding of collected data and materials, the methodology aims to identify key concepts relevant to the research problem and establish logical connections between them, thereby constructing a theoretical explanatory framework pertinent to the research question [60,61]. As GT has evolved, three dominant schools have emerged: the classical GT, championed by Glaser; the procedural GT, advanced by Strauss; and the constructivist GT, associated with Charmaz [62].

This study adopts the procedural GT approach as the primary methodology for the following reasons. First, this study aims to address a “how” type of question. Strauss and Corbin posit that the procedural GT method moves beyond describing “what” to rigorously explain the “how” and “why.” Thereby, it allows researchers to maintain data grounding while appropriately leveraging theoretical sensitivity and academic imagination [63,64,65]. As a key method for generating new insights, it can help capture the practical logic and dynamic interactions in complex situations, thereby laying an empirical foundation for subsequent theoretical construction [66,67]. Second, compared to other schools, procedural GT places greater emphasis on structural rigor in the research process and the systematic nature of coding procedures. It provides a clear, concrete set of analytical steps and techniques. These guide researchers through comparative analysis, theoretical sampling, conceptual development, variation identification, and theoretical integration for in-depth analysis of collected data [68]. This highly structured methodology aims to explore and reveal the causal relationships underlying phenomena more effectively. As a result, it is particularly well-suited to research requiring a clear understanding of the intrinsic mechanisms of events or processes [65,69].

In sum, the procedural GT method enables the in-depth capture of women entrepreneurs’ subjective experiences. Furthermore, it facilitates the distillation of causal chains about digital empowerment while safeguarding the analysis against the imposition of pre-existing theoretical presuppositions [70].

3.2. Data Collection

In November 2024, the research team initiated contact with potential participants meeting the following criteria through “Era of Women Creators”, a representative female entrepreneurship support platform in Southwest China: (1) they are currently operating a start-up enterprise; and (2) systematically utilize digital tools such as platform operations, data-driven decision-making, and digital marketing, within their core business processes. To enhance sample diversity and achieve theoretical saturation, snowball sampling was employed after the first round of interviews. Initial interviewees were asked to recommend peers who met the study criteria. The first three participants recommended two individuals; subsequently, two additional recommendations were sought to introduce contrast in terms of age, sector, or business scale. We determined the final sample size based on the principle of theoretical saturation. Data collection and preliminary analysis occurred concurrently, and interviews continued until no additional theoretical insights or dimensions emerged within our emerging categories [63,71]. This final group of seven participants demonstrates purposively constructed heterogeneity across key demographic and business characteristics (see Table 1). It provides a solid foundation for revealing both common patterns and critical variations in women’s experiences within the digital entrepreneurial ecosystem.

Table 1.

Respondents’ Information.

Before conducting the interviews, the research team provided each participant with a formal interview invitation letter and a data confidentiality agreement, explicitly stating that the collected data would be used solely for academic research purposes. Upon obtaining written informed consent, the research team conducted one-on-one, face-to-face, semi-structured, in-depth interviews with seven women entrepreneurs. All interviews were conducted in private settings and lasted 90–120 min. With participants’ secondary authorization, each interview was audio-recorded in its entirety and subsequently verbatim transcribed. Interview transcripts were generated promptly after each session to ensure an authentic reconstruction of the interview context. The process resulted in a final corpus of approximately 110,000 Chinese characters.

The interview guide was designed entirely in accordance with the principles of thematic focus and dynamic interaction [72]; the complete interview outline is provided in the Appendix A. Thematically, a semi-structured framework was adopted. This framework outlined broad topics relevant to female digital entrepreneurship and provided suggested questions for each subtopic. Dynamically, the questions were designed to foster active dialogue. Interviewers listened to the entrepreneurs’ responses with an open mind and implemented a dynamic follow-up mechanism [73]. The purpose of this approach is to conduct an in-depth, contextualized investigation based on participants’ real-time narratives, rather than rigidly adhering to a predefined question list. When signals related to digital tool usage emerged, interviewers promptly posed open-ended questions to explore the “how” and “why”. For instance, when Participant 4 reported feeling compelled to use digital tools, the interviewer followed up by asking why this was the case and how these feelings influenced her business operations and plans. This mechanism ensured that we could deeply excavate the underlying causes of individual behaviors and capture complex, nonlinear causal logic.

3.3. Researcher Positionality and Reflexivity

Our research team comprises four members from a Chinese university or research institution, with backgrounds in entrepreneurial management, digital entrepreneurship, and sociology. In the study, we share the following key positions:

First, theoretical presuppositions. We all recognize the insights of SRT and are preliminarily aware that digital technology may simultaneously reproduce and challenge traditional gender orders. This leads us to pay particular attention to contradictory narratives within the interview data. Second, value orientation. We approach this research with deep empathy for women entrepreneurs and a firm belief in their agency. Third, positionality and distance. As academic researchers, we maintain a certain distance from the daily lives and business practices of the interviewees. While this may cause us to overlook some tacit knowledge, it also helps us maintain a rational, analytical perspective toward the cases studied [74].

To systematically manage the influence of our positions and enhance the credibility and confirmability of this study, we implemented a series of reflexive practices. For example, after each interview, we promptly wrote memos to record our impressions, observed emotional reactions, and potential unintentional guidance. These were later used for data analysis [75]. Additionally, two team members independently coded the data, then compared and discussed discrepancies to reach consensus.

This ongoing reflexive process does not entirely eliminate our positional influence but makes it transparent, manageable, and productive [76]. Our theoretical model is not an “objective truth” but a co-creation arising from systematic, reflective dialogue between the research team and rich, diverse empirical data. We believe that such transparent reflexivity strengthens the credibility and interpretive depth of the study.

4. Analysis and Results

4.1. Open and Axial Coding

The research team conducted procedural GT coding within the GTE theoretical framework using NVivo 12.0. Procedural GT encompasses three distinct phases: open coding, axial coding, and selective coding [64]. During the open coding process, we used the original statements of women entrepreneurs, and the data were disaggregated, conceptualized, and categorized [71]. We first classified, integrated, and labelled all interview data. Through repeated reading, comparison, and analysis of the original interview transcripts, key information was gradually extracted from fragmented empirical materials and condensed into theoretically meaningful concepts, ultimately forming the study’s initial conceptual and categorical system. As a result of open coding, 109 initial concepts (denoted by lowercase “a” followed by a number) were identified and grouped into 24 conceptual categories (denoted by uppercase “A” followed by a number).

Axial coding aims to establish systematic connections between concepts and categories using the paradigm model, thereby achieving data reintegration. In this study, we first interpreted and elucidated the 24 initial categories derived from open coding. Then, strictly following the classic logic of “causal conditions → phenomenon → context → intervening conditions → action strategies → outcomes” [77], these categories were classified and interrelated, ultimately leading to the distillation of 10 main categories (denoted by uppercase “B” followed by a number). The final open and axial coding outcomes are presented in Table 2 (only a portion of the initial concepts are shown to save space).

Table 2.

Open and Axial Coding Results.

4.2. Selective Coding and Theoretical Model

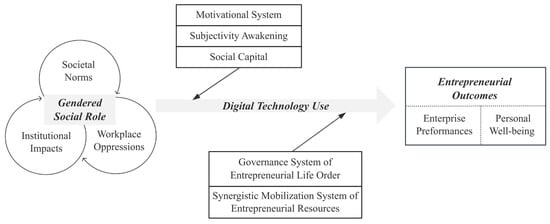

Selective coding constitutes the final phase in the procedural GT coding process. Its core objective is to integrate the internal relationships among the main categories systematically and, through repeated comparison, identify a core category that encompasses all existing concepts and categories. Building on this, the logical relationships between the main categories and the core category are delineated as a storyline, which serves as the basis for theoretical supplementation and integration, ultimately leading to the construction of a theoretical model that reflects the substantive issues under investigation. Through ongoing comparison across all levels of categories, this study ultimately distilled the core category as “Role Tension and Adaptive Construction of Women Entrepreneurs in the Digital Entrepreneurial Ecosystem”. This core category captures the holistic process. Within this process, women entrepreneurs act as adaptive agents. They operate against the backdrop of a macro-social-gender structure, which is a slow-changing parameter. Their experience is characterized by multiple, intertwined social role tensions, all of which are mediated by digital technology. Through strategic digital entrepreneurial adaptation, they ultimately pursue an emergent state of enhanced personal well-being and business sustainability. The resulting theoretical model derived from this procedural GT coding is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Role Tension and Adaptive Construction of Women Entrepreneurs in the Digital Entrepreneurial Ecosystem.

Figure 2 presents a theoretical model representing the adaptive construction process of women entrepreneurs within the digital entrepreneurial ecosystem. An in-depth analysis of this process and its underlying coding reveals a typical practical pattern among Chinese women digital entrepreneurs. First, their use of digital technology demonstrates a pragmatic and measured acceptance. They focus not on mindlessly pursuing technological advancement but on strategically leveraging it as a resource and capability. Second, they are experts at integrating and operating their personal social networks and localized resources. This skill enables them to build cooperative relationships based on trust and emotional bonds. Third and most critically, they strive to balance the grand narrative of platform algorithms with their personal life order. They emphasize autonomous control over operational rhythms and customer relationships. This control is essential for withstanding uncertainties within the digital entrepreneurial ecosystem and protecting personal well-being.

In essence, this entrepreneurial model involves entrepreneurs utilizing privatized user data and relational assets to establish direct, sustainable user connections through self-controlled digital channels, thereby conducting business activities. It transcends mere sales tactics, representing an entrepreneurial philosophy of actively constructing a sustainable sub-ecosystem within an ecology dominated by super-platforms. We term this core practical pattern “Digital Private Domain Entrepreneurship (DPDE)”.

DPDE effectively integrates the gentle attributes characteristic of women entrepreneurs. According to SRT, they are often associated with a warmth dimension [42]. This is reflected in greater empathy, care consciousness, and altruistic tendencies [78]. These attributes lead them to prioritize communication and coordination. They are expert at building and maintaining stable social relationship networks [79]. Therefore, their often-criticized homogeneous social networks can be transformed into trust-based and shared relational capital. It enables the continuous conversion of such capital into business value. Furthermore, DPDE helps women entrepreneurs reduce excessive dependence on and resistance towards the opaque algorithms of digital technology platforms. In the early stages of digital technology adoption, platform operating rules were relatively lenient and often free. This lowered the entry barrier for entrepreneurs, allowing most to enjoy technological dividends relatively [80]. However, as the platform economy deepened, algorithmic logic and capital rules became increasingly dominant. Operational rules became more complex, and promotional costs continued to rise [81]. In this context, DPDE became the preferred choice for many small-scale entrepreneurs. By building long-term, stable, and highly engaged user relationships, women entrepreneurs gradually accumulate trust through sustained, visible, and controllable interactions within the private domain. This trust helps them break progressively free from passive dependence on digital technology platforms. And it also enhances their sense of belonging and efficacy in their entrepreneurial endeavors.

4.3. Theoretical Saturation

The verification of theoretical saturation permeates the entire process of theoretical sampling and coding analysis. Firstly, regarding theoretical sampling, this study adheres to a dynamic principle, whereby sample selection is guided by the potential of samples to reveal new properties, dimensions, or relationships within the theoretical categories. When consecutively selected samples no longer provide new theoretical insights, a preliminary judgment of saturation is made, and sampling is terminated. Secondly, at the coding level, theoretical saturation is considered achieved when most statements begin to reiterate previous observations and no new concepts or categories emerge [82]. To transparently demonstrate this process, Table 3 tracks the emergence, stabilization, and theoretical replication across cases of the 11 main categories. By Interview 5, the vast majority of the main categories had emerged. Their properties were then fully elaborated and replicated in Interviews 6 and 7, with no new categories arising. The continuous refinement of category B5 through the final interview illustrates our ongoing efforts to test theoretical boundaries until saturation was confidently achieved. Concurrently, the entire coding process was conducted independently by another researcher in a “back-to-back” manner. A comparison was conducted at the level of initial concepts. The two coders collectively generated 135 codes. After alignment, agreement was reached on 109 of these codes, resulting in an inter-coder reliability percentage of 80.74% (109/135) for the initial coding stage. Their verification conclusions and the initial coding formed a cross-validation, collectively supporting the establishment of theoretical saturation [83].

Table 3.

Theoretical Saturation Analysis.

5. Discussion

5.1. The Perpetuation and Reconfiguration of Social Role Expectation

According to SRT, society externally assigns stronger work role expectations to men while emphasizing the fulfillment of family roles for women. At the same time, through long-term cultural conditioning and institutional arrangements, individuals of both genders internalize such gender expectations as part of their self-concept. This internalization then leads them to reproduce role behaviors that align with social norms [39]. As illustrated in the grounded model developed in this study, the perpetuation and internalization of traditional gender norms constitute the deep-rooted foundation of women’s role dilemmas. The results of axial coding clearly indicate that the traditional “men as breadwinners, women as homemakers” role script continues to be reproduced intergenerationally through channels such as family, education, and work. This norm is not only reflected in resource allocation but also profoundly shapes women’s cognitive frameworks [84]. For example, some interviewees expressed agreement with “biological determinism” (a7, a8). They attributed the constraints they encountered in daily life and in career development to innate biological gender traits. It is a clear manifestation of the deep internalization of social expectations. This internalization may lead women to self-limit from the outset of their careers, thereby foreshadowing their subsequent professional development trajectories [85,86]. For instance, Interviewee 2 stated during the interview:

“Women inherently possess a physiological structure that makes them more prone to jealousy than men—this is truly innate. … once such jealousy arises, it creates problems in the workplace. What does this lead to? It reduces their opportunities for advancement or even cuts short their career prospects.”

The deepening and reconfiguration of this role dilemma are particularly intense and complex in the workplace. On the one hand, the workplace harbors an implicit gender order that places women at a disadvantage [87,88,89], serving as a key force in maintaining and reinforcing their role dilemmas. For example, the persistent tension may arise between the responsibility-bound role of “motherhood” in the domestic sphere and the performance-oriented expectations of being an “agent” in the professional domain (a9). This conflict not only leads to cognitive overload and identity fragmentation for women. It also consolidates their marginalization in the labor market and entrepreneurial ecosystem. This consolidation occurs through mechanisms of resource deprivation, including inequalities in time allocation, social capital accumulation, and financing opportunities. Moreover, the “age constraints in the female labor market” (a26) place women under dual pressures of career development and family responsibilities during their prime childbearing years. This phenomenon may push them toward secondary career tracks that align with their familial roles [90]. As Interviewee 5 noted:

“Because women now take on many social roles—they are daughters, wives, and mothers in a family, and if they also have their own careers, they assume different roles. These multiple roles force them to constantly switch identities, which I think is a particular dilemma many women face. At work, we must perform well; at home, we must support our children with their studies; and when our parents are unwell, we must care for them. All these responsibilities seem to fall on us… things women must do.”

On the other hand, women are not merely passive recipients of socially assigned roles. In the process of accepting societal institutional and cultural conditioning while engaging in self-resistance, they actively reshape their social roles. When women clearly perceive structural injustices, it sparks their consciousness and actions of resistance. For instance, some interviewees attempted to break the workplace gender order through entrepreneurship (a31), representing a form of resistance to and reconfiguration of traditional role expectations and gender stereotypes. By creating their own work environments, they renegotiate the boundaries between work and family and define multifaceted identities of success [10].

Overall, the social role dilemmas of women present a dynamic cycle. Social gender norms, transmitted intergenerationally and internalized culturally, lead women to role scripts centered on the family. When they enter the workplace, institutionalized gender orders further reinforce and solidify these scripts, creating barriers to their development. Yet, this dilemma is being reconfigured through women’s growing subjective agency. Through daily strategic management and active resistance, they continually challenge and renegotiate the boundaries of established roles.

5.2. From Role Dilemmas to Entrepreneurial Agency

While SRT explained how individuals internalize external expectations to shape their behavioral patterns, women are not entirely passive in the process of enduring role dilemmas. Instead, they demonstrate a significant capacity for role-breaking and self-reconstruction. Thus, entrepreneurial behavior not only represents a substantial outcome of women’s breakthrough in overcoming role constraints. At the same time, it serves as a crucial driving force that propels this transformative process.

First, in the context of the digital technology era, the dissemination of open cultural content continually shapes women’s perceptions of gender roles, fostering the awakening of their subjective consciousness [91,92]. Entrepreneurial behavior constitutes women’s response to traditional social role expectations and a value-driven resistance following the awakening of their subjectivity. Interview data indicate that women’s initial motivations for choosing entrepreneurship increasingly reflect a pluralistic value orientation that extends beyond economic rationality. This shift marks a key change from survival-driven to opportunity-driven entrepreneurship [93,94,95]. Some interviewees regard entrepreneurship as an essential means for self-actualization (a54), while others adopt it as an active strategy to break away from family-prescribed life trajectories (a68). This decision-making process illustrates the whole progression of women entrepreneurs. It traces their journey from conscious awakening to the construction of agency. Furthermore, it highlights their active claim to the right of self-definition and control over their own development (a65, a66).

In this process, entrepreneurial practice serves as a vital force through which women actively seek to reshape their personal values after experiencing the structural role constraints (a67, a69, a102) [96]. By establishing and running their own businesses, they aim to deconstruct the traditional narrative that women should prioritize familial roles. As a result, they achieve a breakthrough in social roles, moving from passive acceptance to active construction. As Interviewee 3 reflected on her motivation for starting a business:

“He (the interviewee’s partner) never explicitly said he wanted me to stay at home without working, but his various behaviors made me feel very uncomfortable. As noted earlier, I repeatedly emphasized that, to demonstrate my continued value, I continued to pursue entrepreneurial activities. Because as a woman at home, even if you dedicate everything to the family, your sense of worth is often unrecognized—too easily overlooked. “

Second, the critical pathways to achieving entrepreneurship are reflected in two core mechanisms: the integration of resource systems and the development of psychological resilience in balancing entrepreneurship with life. In terms of resource integration, women entrepreneurs must demonstrate significant agency. This is necessary to confront the multiple constraints imposed by traditional norms and the resulting gender stereotypes [97]. They achieve breakthroughs by proactively accessing institutional resources (a80). For example, emphasizing shared values when building their core teams (a84), thereby creating a supportive environment that understands and encourages their role-transcending practices. Regarding psychological resilience, women entrepreneurs adopt various emotional regulation strategies to alleviate negative emotions triggered by daily entrepreneurial activities, including the use of digital technologies (a91) [98]. This process involves managing boundaries across multiple roles and coping with stress. Moreover, it reflects a dynamic capacity to balance the empowering and constraining aspects of digital tools.

5.3. Dual Impact Mechanism of Digital Technology

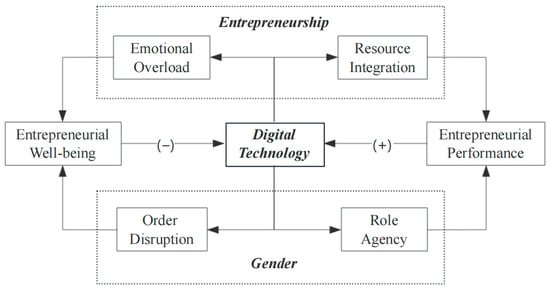

As previously discussed by scholars, digital technology plays the role of a “contradictory actor” in female entrepreneurial activities [4,7,30,99,100]. This study further revealed how these effects are mediated by two competing and complementary pathways within the GTE perspective (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Conceptual Model of the Dual-Impact Mechanisms of Digital Technology.

5.3.1. Positive Loops: Resource Integration, Role Agency, and Performance Improvement

Digital technology has become an affordable and powerful resource for women entrepreneurs (a47), enabling them to maintain baseline continuity in their enterprises at a low cost of trial and error [8,22]. Through low-cost, high-tolerance entry, they are better able to accept their social role dilemmas. It allows them to acquire both economic and psychological capital to sustain their enterprises and improve entrepreneurial performance.

First, with respect to institutional resource linkage, digital technology serves as a critical bridge. Women entrepreneurs could actively adopt digital empowerment strategies (a33). They can leverage digital platforms to efficiently bridge institutional resources (a80). This approach also helps achieve functional integration of human resources (a81) required for entrepreneurship. For instance, they could precisely reach target customers through social media and efficiently apply for entrepreneurial subsidies via online government platforms. Alternatively, they might participate in women-specific support programs offered by major e-commerce platforms, thereby alleviating resource shortages. Such efficient linkage directly translates digital technological advantages into tangible operational capital [101]. Second, in the governance of human resource relationships, the incorporation of digital technology significantly enhances trust-building and collaboration efficiency. Digital tools provide foundational support for transparent collaboration and strengthen team integration based on the principle of complementary capabilities [102,103]. Simultaneously, daily interactions and value demonstrations on social media implicitly screen and reinforce value alignment as a cornerstone of governance integration [104,105]. In this pathway, digital technology serves as an efficiency lever. It amplifies the positive impact of the synergistic mobilization system of entrepreneurial resources (B8), ultimately improving entrepreneurial performance (B11). For example, when talking about business development, one entrepreneur engaged in AI education said:

“I once followed up with my clients and asked them why they chose to take my class instead of another (male) tutor’s. They told me that when people hear about information technology, their first impression is that it is a male-dominated, highly technical field. However, after hearing my introduction, they felt it was presented in an easy-to-understand manner by a young woman (me) and were very willing to listen.”

“I rely on the trust my friends have in me (to conduct business). For example, after I completed my product presentation, many students who had never attended any of my classes paid directly and said, ‘I trust you.’ Please send me the recording, and I will listen to it when I have time.”

Concurrently, the success of this digital empowerment loop represents a form of entrepreneurial resistance by women entrepreneurs against traditionally assigned gender roles. By successfully building enterprises in digital spaces, they attain economic capital and establish subjective value. Women gradually come to define their actions through self-awareness. This catalyzes a paradigm shift in decision-making logic from other-centeredness to self-actualization, thereby sustaining baseline venture continuity amid role conflicts. This success challenges the presumption in SRT that prioritizes women’s caregiver role. It legitimizes their new identity as entrepreneurs and also helps reconstruct their social role, which mitigates role conflict to some extent. For instance, our entrepreneurs said in the interview:

“I have a friend who is a designer. She could not balance her work and her children, so she quit her job and then started an e-commerce business, which was very successful. In two years, she earned more than 4 million yuan and built a team of tens of thousands of people.”

“In my youth, I engaged in self-validation to demonstrate utility and worth to external others. However, I now recognize that such validation is unnecessary. Many women condition self-acceptance upon acquiring external approval, indicating insufficient intrinsic self-worth, actually.”

In summary, within the empowerment loop, digital technology enables women entrepreneurs to overcome the gendered resource constraints described by social role theory. It allows them to renegotiate and redefine their social roles through successful economic practices.

5.3.2. Negative Loops: Emotional Overload, Order Disruption, and Well-Being Erosion

Beneath the apparent empowerment narrative of digital technology lies its latent role as a constraining mechanism. It systematically depletes the psychological and cognitive resources essential for women entrepreneurs to engage in practical reasoning. At the same time, it intensifies the challenges of maintaining a balanced life. In turn, it may lead to long-term erosion of well-being.

Algorithmic black boxes and the traffic hegemony of digital technology may impose systemic technological subjugation on entrepreneurs (a38, a39). This is especially true on some common social media platforms. Many women seek to leverage the low barriers to entry of digital technology for entrepreneurship. However, the operational opacity created by algorithmic unknowability transforms their investments into gambles [4]. In practice, this offsets the often-idealized “low-barrier” advantage of the technology. Concurrently, the randomness of traffic distribution exacerbates their survival anxiety. This forces them to commit greater financial resources simply to secure attention within platform ecosystems. Moreover, this adverse effect tends to trap women entrepreneurs in compulsive dependence on technology, thereby reinforcing a vicious cycle. In a highly digital entrepreneurial environment, the fear of being excluded from the digital ecosystem compels them to passively accept established platform rules and join the “digitalization game”, even when harboring doubts. Due to relatively limited resource endowments, some women entrepreneurs may over-rely on digital technology as a perceived shortcut to breakthroughs. However, they usually lack full awareness of how algorithmic mechanisms further intensify the Matthew effect in resource allocation [106]. Thus, women entrepreneurs move from initially “hitching a ride” on digital trends to gradually becoming “taken hostage” by digital technology, with their autonomy significantly constrained. This generates negative emotions toward the use of digital tools (a43, a45). As Interviewee 4 admitted, while her current operations heavily depend on digital platforms, the return on investment remains far from optimistic, leading to excessive anxiety:

“But look at any shop today—who doesn’t use X (one Chinese digital platform)? It feels like an inevitable trend. If no one used it, it might not be necessary; we could focus on community-based business. But when everyone is on it, not having it makes you feel…left behind. And I use X myself; it really matters for consumption. For example, you wouldn’t just walk into any hair salon on the street—you’d check on X first: how good are the reviews, what are the prices? You wouldn’t simply walk in. Nowadays, that’s just how most people think about consumption.”

“It costs me thousands of RMB monthly on platform promotions, yet when not even a single customer comes from these efforts, I feel intensely frustrated, pressured, and anxious, completely overwhelmed by these feelings.”

Furthermore, the boundaryless nature of digital technology undermines women entrepreneurs’ spatiotemporal boundary management [7]. The illusion of flexibility offered by digital technology apparently enhances women entrepreneurs’ temporal sovereignty. Yet it simultaneously dissolves physical work boundaries. The perpetual intrusion of work demands into private spheres may trigger work intrusion cognitions. The continuous intrusion of work demands into the life sphere triggers work-intrusive cognitions (a92, a93). When caregiving responsibilities and client responsiveness persistently collide within the domestic sphere, it may paradoxically intensify the fragmentation of women’s social roles. Critically, when psychological load capacity breaches a critical threshold, it could trigger negative states such as emotional distress (a89). In such situations, the psychological toll of forced role integration may offset the sense of achievement brought by entrepreneurship. To maintain external performance, women entrepreneurs often feel compelled to sacrifice their inner well-being, plunging them into profound personal dilemmas. This high-intensity emotional labor and persistent role conflict severely drain their psychological and cognitive resources (a104) [107,108]. Interviewee 6 noted that, compared to regular employment, she found it much harder to separate work from life while running her own businesses:

“You will find that when you are free, you may still be thinking about work, but actually, this is not the state I want to be in. Sometimes, even when I have time, I find myself wondering whether I should start another business, expand into a new project, or develop another product. My thoughts still revolve around work. I can’t really step away and tell myself, ‘Today I have time—I won’t think about work at all, I’ll just spend time with my family.’ Honestly, my mind and body feel out of sync.”

Concurrently, this loop profoundly reveals how digital technology reinforces and modernizes traditional social role discipline. The “always-on” culture fostered by digital technology creates a new expectation of the “digital super-mother or super-woman entrepreneur”. Entrepreneurs often feel compelled to perfectly fulfill the dual roles of both online entrepreneur and offline mother or wife. While digital technology blurs physical boundaries, it simultaneously exerts pressure on societal expectations for women’s roles in both spheres [109,110]. Consequently, entrepreneurs are compelled to switch rapidly among their various social roles. This results in profound identity fragmentation and confusion about their own roles. This vividly embodies the digital role cage: while digital technology appears to grant the freedom to work anytime and anywhere, it in fact constructs an omnipresent, invisible prison.

In summary, the impact of digital technology on women’s entrepreneurship fundamentally stems from a complex interplay between empowerment and constraint. Entrepreneurs can leverage digital tools as a strategic lever to efficiently mobilize resources and drive business growth. However, they must simultaneously bear the ongoing costs of technology-intensified role conflicts and emotional labor. This tension, while enhancing entrepreneurial performance, often comes at the expense of deeper individual well-being, forming a core paradox in women’s entrepreneurial practice in the digital age that urgently requires attention.

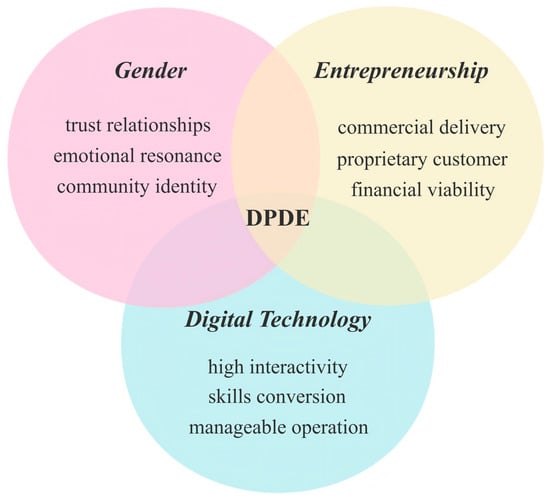

5.4. Systemic Adaptation Through DPDE

DPDE emerges as a critical systemic adaptation strategy for women navigating the dual mechanisms of the digital entrepreneurial ecosystem. Leveraging social platforms such as WeChat, Xiaohongshu, and Douyin, women entrepreneurs develop business models centered on trust-based, exclusive customer communities and closed-loop commercial systems [111,112]. This adaptation is evident in prevalent models such as short-video and live-streaming e-commerce. For example, short-video and live-streaming e-commerce have empowered many women with gig-like entrepreneurship and income expansion [8,113]. It is also evident in the social relationship-based “micro-business” model [114].

The strong growth of female DPDE results from its ability to effectively tackle the many challenges discussed earlier. It is more than a strategy; it is an emergent, sustainable sub-ecosystem that women entrepreneurs create within the broader digital platform ecosystem. From a GTE perspective, it represents a model of strategic technology adoption and entrepreneurial innovation based on gender-specific characteristics. In this model, digital technology functions as a lever for transforming gendered capital, while entrepreneurial action serves as a practice that reconstructs the social roles.

The sustainability of DPDE can be examined effectively from two perspectives. Its economic sustainability is fundamentally anchored in cultivating a proprietary customer base, thereby reducing dependence on the volatility and high costs associated with public traffic domains. Through sustained, refined operations and social interactions, women entrepreneurs can progressively build stable, trust-based relationships. This enables low-cost, highly efficient repeated reach to users. It also allows for accurate responses to diverse needs. Ultimately, it effectively enhances repurchase rates and user loyalty [111,112,115]. “Public domain entrepreneurship” typically entails intense competition on platforms such as Taobao. In contrast, the core characteristics of DPDE are different. They lie in deep control over customer relationships, high interactivity and emotional connection, and relatively manageable operational rhythms. This direct and recurring access to a loyal customer community ensures a more stable cash flow. It significantly lowers customer acquisition costs, thereby enhancing the venture’s overall financial viability and resilience against external shocks such as algorithmic volatility on major platforms [116].

Furthermore, DPDE is crucial in promoting the psychological resilience of women entrepreneurs. First, it enables women entrepreneurs to transform from “passive recipients” of social role expectations into “active architects”. Rather than merely juggling overlapping or conflicting roles, they systematically build and operate private traffic pools, thereby creating a space in which these roles can mutually reinforce one another. By effectively integrating traditionally marginalized feminine skills, such as emotional labor, relationship maintenance, and maternal experience with digital technology, women entrepreneurs are able to convert these capabilities into market-valued business capital. Second, the emotional resonance and strong sense of community identity cultivated within the private domain endow these entrepreneurs with a profound sense of meaning and autonomy. This enhanced sense of purpose and control directly boosts their entrepreneurial well-being. In turn, this boosted well-being serves as a fundamental motivational driver. It drives their continued engagement and sustained investment in their enterprises [117]. The conceptual model diagram is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Conceptual Model of DPDE under the GTE framework.

In sum, DPDE reduces reliance on unpredictable platform algorithms. It also facilitates the gradual formation of a self-sustaining business closed loop, thereby enhancing the robustness and sustainability of female entrepreneurial ventures. In turn, it fosters a unique and vibrant “she-economy” entrepreneurial ecosystem.

5.5. Theoretical Contributions and Practical Implications

This study makes several key theoretical contributions and offers practical implications. Theoretically, this study develops an integrated GTE framework that integrates SRT. It moves beyond linear narratives of digital empowerment. Instead, it models the recursive interplay between gendered structures, technological affordances, and entrepreneurial action. Moreover, the study theorizes a critical role transition pathway for women entrepreneurs, from navigating externally imposed role dilemmas to exercising entrepreneurial agency and ultimately to the agentic reconfiguration of social roles. Furthermore, it advances the literature on entrepreneurial strategy. It conceptualizes DPDE not just as a tactical choice, but as the agentic construction of a sustainable sub-ecosystem. This conceptualization helps reveal the emergent properties of complex entrepreneurial ecosystems.

Practically, the findings of this study also have important implications. For women entrepreneurs, the findings highlight the crucial role of strategic agency in navigating the digital landscape. It is of great importance for them to proactively leverage digital affordances. This involves reframing their identity and networks. It also means transforming perceived gendered constraints into unique relational capital and entrepreneurial means. These actions are crucial for building resilience and venture sustainability. At the same time, developing strong digital boundary management competencies is essential to mitigate the risks to well-being inherent in boundaryless work. Entrepreneurs should actively design routines and spatial cues to segment work and personal life, resisting the illusion of constant availability. Furthermore, cultivating critical awareness of algorithms is crucial. Women entrepreneurs should recognize that platform algorithms are opaque systems. These systems are designed for user engagement rather than fairness. This recognition could help them mitigate compulsive dependence and lead to more informed resource-allocation decisions. So, it may reduce existential anxiety and transform a state of passive subjugation into one of informed navigation.

For policymakers, it is essential to examine regulatory frameworks that require platforms to disclose their core principles governing content visibility, data usage, and traffic distribution, thereby promoting fairer competition. Complementing this, promoting equitable access and digital ability is vital. Public initiatives should specifically target women entrepreneurs, particularly those from marginalized groups, such as middle-aged women re-entering the workforce. This training should not only focus on basic digital skills but also on understanding algorithmic risks, platform governance, and effective boundary management strategies.

6. Conclusions

6.1. Research Findings

This study employed the integrated GTE framework to examine the complex dynamics influencing female entrepreneurship in the digital era. Through a GT analysis of seven Chinese women digital entrepreneurs, we revealed how components of the digital entrepreneurial ecosystem interact to produce dual outcomes. This study also identified the strategic adaptations entrepreneurs employ.

First, the digital entrepreneurial ecosystem is defined by competing feedback loops of empowerment and constraint. Digital technology functions not only as an empowerment amplifier that catalyzes resource synergy and mobilizes venture resilience, but also as a constraint mechanism that constructs a subtle digital role cage. This cage systematically blurs work–life boundaries, depletes psychological resources, and undermines personal well-being.

Second, the navigation of this system is driven by a core process of agentic role reconfiguration. Confronted with externally imposed role dilemmas, women entrepreneurs exercise entrepreneurial agency to strategically transform structural constraints into actionable means. This agentic practice facilitates a transition from passive role acceptance to the active renegotiation and reshaping of social roles within digital spaces.

Ultimately, DPDE represents a key systemic adaptation through which entrepreneurs actively construct a sustainable sub-ecosystem by recasting the rules of interaction and value exchange. This approach enables the conversion of traditionally feminized skills into valuable commercial capital, thereby fostering greater operational autonomy and venture sustainability.

In conclusion, the interplay between digital technology and female entrepreneurship is best characterized by complex embeddedness. Technology’s impact is neither deterministic nor uniformly positive, but is shaped by how entrepreneurs strategically deploy it within entrenched gendered structures. The emergence of DPDE illustrates a sophisticated pathway for women to harness digital affordances while actively mitigating their constraints, thereby contributing to a more resilient and sustainable digital entrepreneurial landscape.

6.2. Limitations and Future Research

While this study offers profound insights into the duality of digital empowerment for Chinese women entrepreneurs, several limitations remain. First, the in-depth analysis of this study reached theoretical sufficiency for framework development within this sample. Given the sample size (n = 7), the resulting saturation should be interpreted as conceptual completeness for these specific cases, not as encompassing all possible scenarios. Therefore, the generalizability of our framework should be assessed in future research using larger samples. Secondly, although rich in experiential depth, the GT analysis in this study limits the generalizability of the findings to all women entrepreneurs. This is particularly true for those in different sectors, using various digital models, or operating in significantly different cultural or economic contexts outside China. The experiences of women facing intersecting marginalizations, such as based on rural location, lower socioeconomic status, or ethnicity, may also be underrepresented. Finally, GT could capture perceptions and experiences of women entrepreneurs at a specific point in time. However, it cannot track the evolution of resilience performance and well-being dynamics longitudinally as ventures mature or digital ecosystems shift.

Building upon these limitations and our findings, future research could explore the following avenues: first, conduct large-scale, cross-cultural surveys to quantitatively test the proposed relationships between digital affordances, gendered role constraints, resilience performance dimensions, and well-being facets. This would assess the generalizability of the framework, particularly across diverse entrepreneurial models and national contexts with varying gender norms and digital infrastructures. Second, employ longitudinal mixed-methods designs tracking women digital entrepreneurs over time. This is crucial for understanding how resilience performance and personal well-being evolve in response to venture lifecycle stages, platform algorithm changes, and personal life events.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.W.; Data curation, L.W.; Formal analysis, L.W. and Q.Y.; Funding acquisition, Y.L.; Investigation, L.W.; Methodology, L.W. and Q.Y.; Resources, L.W. and Y.L.; Software, L.W. and Q.Y.; Supervision, J.L. and Y.L.; Visualization, L.W. and Q.Y.; Writing—original draft, L.W.; Writing—review and editing, Q.Y., J.L. and Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Major Program of National Social Science Foundation of China [grant number No. 23&ZD051] and the Civilization Mutual Learning and Globa Governance Research Program of Sichuan University. The APC was funded by the Corresponding Author.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Professor Committee of Business School, Sichuan University (ER20250010) on 24 September 2025.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to respondents’ privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Interview Outline

Note: Upon receiving a response to each question, the interviewer probes into the how and why.

- Please briefly introduce your entrepreneurial career. (e.g., founding story, business model, current operational status, team members, etc.)

- Which digital technologies have you utilized during your entrepreneurial journey? Did you encounter any difficulties in adopting these digital technologies?

- How would you evaluate the impact of digital technology on your entrepreneurial venture?

- What is your perspective on female entrepreneurship? (e.g., the macro-environment for female entrepreneurship, practical challenges faced by women entrepreneurs, etc.)

- What impacts has entrepreneurship brought to your personal life?

- From a practical standpoint, what other dimensions regarding the topic of female entrepreneurship do you believe warrant attention?

References

- Du, W.; Pan, S.L.; Zhou, N.; Ouyang, T. From a marketplace of electronics to a digital entrepreneurial ecosystem (DEE): The emergence of a meta-organization in Zhongguancun, China. Inf. Syst. J. 2018, 28, 1158–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambisan, S. Digital Entrepreneurship: Toward a Digital Technology Perspective of Entrepreneurship. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2017, 41, 1029–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Huo, D.; Wu, D. Digital economy development and venture capital networks: Empirical evidence from China. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 203, 123338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhajri, A.; Aloud, M. Female digital entrepreneurship: A structured literature review. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2023, 30, 369–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sussan, F.; Acs, Z.J. The digital entrepreneurial ecosystem. Small Bus. Econ. 2017, 49, 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ughetto, E.; Rossi, M.; Audretsch, D.; Lehmann, E.E. Female entrepreneurship in the digital era. Small Bus. Econ. 2020, 55, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dy, A.M.; Marlow, S.; Martin, L. A Web of opportunity or the same old story? Women digital entrepreneurs and intersectionality theory. Hum. Relat. 2017, 70, 286–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Cui, L. China’s E-Commerce: Empowering Rural Women? China Q. 2019, 238, 418–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, B.K.; Goh, G. Digital Entrepreneurs in Artificial Intelligence and Data Analytics: Who Are They? J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2020, 6, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAdam, M.; Crowley, C.; Harrison, R.T. Digital girl: Cyberfeminism and the emancipatory potential of digital entrepreneurship in emerging economies. Small Bus. Econ. 2020, 55, 349–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouse, J.; Woolnough, H. Engaged or Activist Scholarship? Feminist reflections on philosophy, accountability and transformational potential. Int. Small Bus. J.-Res. Entrep. 2018, 36, 429–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, B.E.; Pruchniewska, U. Gender and self-enterprise in the social media age: A digital double bind. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2017, 20, 843–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dy, A.M.; Martin, L.; Marlow, S. Emancipation through digital entrepreneurship? A critical realist analysis. Organization 2018, 25, 585–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappas, M.A.; Drigas, A.S.; Papagerasimou, Y.; Dimitriou, H.; Katsanou, N.; Papakonstantinou, S.; Karabatzaki, Z. Female Entrepreneurship and Employability in the Digital Era: The Case of Greece. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2018, 4, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson-Zetterquist, U.; Lindberg, K.; Styhre, A. When the good times are over: Professionals encountering new technology. Hum. Relat. 2009, 62, 1145–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, F.; Sun, H.; Ren, R.; Chang, W. Impact of the digital entrepreneurial ecosystem on startup performance: An empirical study from China. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2024, 96, 103611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Tao, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Ye, Y. The road to entrepreneurship: The effect of China’s broadband infrastructure construction. Econ. Anal. Policy 2023, 80, 1831–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creemers, R. China’s emerging data protection framework. J. Cybersecur. 2022, 8, tyac011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.; Shi, Q.; Zhang, Y. Platform economy and missing entrepreneurship: Evidence from E-commerce development policy in China. Econ. Transit. Institutional Change 2025, 33, 209–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; de Kloet, J. Platformization of the unlikely creative class: Kuaishou and Chinese digital cultural production. Soc. Media+ Soc. 2019, 5, 2056305119883430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, K.; Ma, R.; Zhao, L.; Wang, K.; Kamber, J. Did the cyberspace foster the entrepreneurship of women with children in rural China? Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1039108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, F.L.; Xiao, M. Women entrepreneurship in China: Where are we now and where are we heading. Hum. Resour. Dev. Int. 2021, 24, 104–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paoloni, P.; Secundo, G.; Ndou, V.; Modaffari, G. Women Entrepreneurship and Digital Technologies: Towards a Research Agenda. Adv. Gend. Cult. Res. Bus. Econ. 2019, 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, W. Knowledge transfer in intraorganizational networks: Effects of network position and absorptive capacity on business unit innovation and performance. Acad. Manag. J. 2001, 44, 996–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, N.; Wetsch, L.R.; Hull, C.E.; Perotti, V.; Hung, Y.-T.C. Market orientation in digital entrepreneurship: Advantages and challenges in a web 2.0 networked world. Int. J. Innov. Technol. Manag. 2012, 9, 1250045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barasinska, N.; SchÃfer, D. Is crowdfunding different? Evidence on the relation between gender and funding success from a German peer-to-peer lending platform. Ger. Econ. Rev. 2014, 15, 436–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helsper, E.J. A Corresponding Fields Model for the Links Between Social and Digital Exclusion. Commun. Theory 2012, 22, 403–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preston, A.; Qiu, L.; Wright, R.E. Understanding the gender gap in financial literacy: The role of culture. J. Consum. Aff. 2024, 58, 146–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, E.S.; Von Briel, F.; Davidsson, P.; Kuckertz, A. Digital or not—The future of entrepreneurship and innovation: Introduction to the special issue. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 125, 436–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Keane, M. Struggling to be more visible: Female digital creative entrepreneurs in China. Glob. Media China 2020, 5, 407–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, G.; McAdam, M. Women Entrepreneurs Negotiating Identities in Liminal Digital Spaces. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2023, 47, 1942–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Chan, R.C.K. Gendered digital entrepreneurship in gendered coworking spaces: Evidence from Shenzhen, China. Cities 2021, 119, 103411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marlow, S. Exploring future research agendas in the field of gender and entrepreneurship. Int. J. Gend. Entrep. 2014, 6, 102–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biddle, B.J. Recent Developments in Role-Theory. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1986, 12, 67–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.N.X.; Wang, J.P.; He, Y.L.; Nie, J.Y.; Wen, J.R.; Li, X.M. Incorporating Social Role Theory into Topic Models for Social Media Content Analysis. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2015, 27, 1032–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mead, G.H. Mind, Self & Society; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Linton, R. Culture, society, and the individual. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 1938, 33, 425–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuler, R.S.; Aldag, R.J.; Brief, A.P. Role conflict and ambiguity: A scale analysis. Organ. Behav. Hum. Perform. 1977, 20, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]