Abstract

Accurately grasping the relationship between science and technology finance efficiency (STFE) and carbon emission efficiency (CEE), and further exploring their interaction and synergistic development within the network structure are of great significance for promoting regional coordinated development, economic growth, and environmental issues. This article uses the super-efficient SBM model to measure the STFE and CEE in 30 provinces of China from 2011 to 2020, and innovatively introduces the Multi-Layer Network (MN) method to explore the characteristics of their network structure, synergistic evolution, and influencing factors. The results show that (1) the evolution of the MN structure is the result of synergistic development, which mainly forms the network pattern of the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei, the Yangtze River Delta, and the Qinghai–Gansu region with “triple-core, multi-zone”. (2) The STFE network plays a leading role in the MN structure by influencing the CEE network structure. (3) The layers of MN are connected in a disassortative way, while the network similarity is gradually increasing. (4) The number of communities of the MN is decreasing, and the agglomeration of the community structure is gradually increasing. (5) The performance of the MN structure has better robustness than the single-layer network under different strategies and different node retention levels of destruction. (6) The economic development level, government support rate, and industrial structure upgrading are the core factors affecting the value of weighted degree and closeness centrality, while betweenness centrality is mainly affected by the urbanization level and foreign direct investment level.

1. Introduction

The world’s increasing environmental challenges pose a severe threat to the progress of human society. Consequently, nations across the globe are becoming more preoccupied with figuring out how to lower their emissions of greenhouse gases, and to encourage green development and transformation. According to a report by the CPC’s 20th National Congress, it is imperative that we expedite the green transformation of the mode of development, aggressively and consistently advance the “double carbon” goal, and achieve the decarbonization and greening of economic development. As a main industry supporting the progress of various sectors, finance plays the role of guiding the flow of capital, thus improving the financing conditions of related industries and promoting the innovation and industrialization of technical and scientific accomplishments [1,2,3]. Science and technology finance (STF) is a new model for the integration of Sci-Tech and finance, which promotes the rapid development of the economy. Efficiency is an important index for comprehensively evaluating the development of STF, and STFE measures the input–output efficiency of the Sci-Tech system based on the consideration of the financial support of the financial system, which plays a key role in exploring the efficiency of scientific and technological innovation in enhancing CEE [4]. The improvement of CEE also forces the related industries to transform and upgrade to different degrees, inject fresh vitality into the development of STF, promote the prosperous of Sci-Tech innovation, and ultimately protect and improve the environment [5]. Therefore, realizing the deep integration and development of STFE and CEE is of great importance for improving green technological innovation and realizing a win–win situation for ecological environment improvement and economic development.

It is impossible to separate scientific and technical innovation activities from the assistance of financial resources, and the transformation of achievements and scientific and technical creation can be efficiently fostered by the combination of Sci-Tech and finance. Countries with a higher degree of global innovation have comparatively well-developed STF systems and financial markets, and studies have mostly examined the connection between finance and Sci-Tech innovation [6]. For example, Atanassov (2016) found that firms relying on the capital market to obtain long-term financing for technological innovation have more intellectual property rights and innovation outputs [7]. With the integration of Sci-Tech and financial development to improve enterprise innovation ability, optimize the distribution of financial resources, and promote economic growth, the role of advantages gradually appeared, and STF has progressively received attention from all sectors of society [8,9]. The term “Science and Technology Finance” was first proposed by the Shenzhen Science and Technology Bureau of China in 1993; relevant scholars have since extended and expanded its definition and connotations [10]. According to Changwen Zhao, it is a collection of financial tools, systems, regulations, and services that support the advancement of technology, the transformation of accomplishments, and the expansion of high-tech sectors [11]. Moreover, there has been increasing scholarly focus on the effects and mechanisms of pilot policies specifically designed for STF [8,12,13], the influence relationship between STF and other subjects [14], and the measurement of the efficiency of STF [15]. Among these approaches, the efficiency perspective offers a critical framework for quantifying the Sci-Tech Finance (STF) evaluation system. By systematically accounting for the input–output efficiency of both human and capital resources, it more accurately captures and explains how financial resources facilitate the transformation of scientific and technological innovations [15,16].

As environmental regulations tighten and the “dual-carbon” goal advances, we must examine whether strengthening STFE can simultaneously spur technological innovation in related industries and drive environmental improvement [17,18]. The impact of greenhouse gas emissions on the environment has drawn national attention in recent years [19]. Academic discussions have been triggered around the influence of financial development on carbon emissions [20,21]. At the same time, some scholars have conducted in-depth research on the mechanism by which technology finance affects carbon emissions, as well as the possible capital mismatches within this mechanism and the carbon reduction effects of different components of technology finance [22,23]. Furthermore, empirical research revealed that progress in finance will lower carbon emissions by raising the standard of technology and increasing the efficiency of energy use [24]. By measuring the degree of financial development using a variety of metrics, it has been discovered that carbon emissions are significantly impacted by financial scale and financial efficiency [25]. As for carbon emission-related research, scholars start from different industry perspectives and use different efficiency measurement methods to measure the efficiency of agricultural CEE [26], industrial CEE [5], tourism CEE [27], and other aspects. Carbon emission efficiency serves as a core indicator for assessing low-carbon economic development. It captures the efficiency of energy utilization, capital allocation, and human resource transformation. Enhancing CEE constitutes a pivotal pathway toward achieving the “dual-carbon” goals [28,29]. In terms of analyzing the spatial effects of CEE, the research perspectives are rich, and at the international [30], inter-provincial [31] and regional [32] levels, the spatial and temporal heterogeneity of CEE has been analyzed and explored from the perspectives of regional distribution differences [33], spatial spillover effects [34] and other perspectives, respectively. As for the analysis of influencing factors affecting CEE, scholars have also analyzed it in terms of energy consumption [35], urbanization level [36], and economic development [37]. As may be observed from the above, there are several theoretical and empirical investigations on the STFE and CEE, with gradually rich research contents and expanding research perspectives. However, the relationship between the STFE, that is, the efficiency of financial capital supporting the commercialization of scientific and technological advances, and how it affects the efficiency of carbon emissions, has not been involved. Furthermore, the study of the spatial correlation between STFE and CEE is rather limited, without considering the global connections, and it is difficult to reveal the corresponding complex relationship, hierarchical structure, and nested relationship between various regions. With the further deepening and advancement of regional synergistic development strategies, the rapid flow and dissemination of financial capital, information technology, and human resources between regions, the spatial association between regions has broken through the local geographic proximity, and gradually shows the characteristics of a spatial network structure, with a global spatial correlation network relationship having been formed [38]. However, the recent research on complex networks mainly concentrates on the construction of single-layer networks, which describe the single relationship between nodes with the same attributes, and it is hard to reflect the interaction between nodes with different attributes. To overcome the limitations of single-layer networks, Multi-Layer Networks have emerged as a growing research focus in network science. By representing systems through multiple interconnected layers, MNs enable a more comprehensive analysis of complex interactions across different types of relationships or objects [39,40]. Currently, MN theory is widely applied in numerous fields, including economics, finance, society, transportation, and so on, and it has yielded many study findings [41]. Owing to the financial system’s intricate structure [42], more and more scholars have begun to use MN analysis to study the correlations between financial systems [43], financial risk contagion [44], and asset price transmission mechanisms [45]. MNs are better equipped to capture the correlations and interactions across systems. Grounded in multi-layer complex network theory, this approach offers a more effective and practical framework for analyzing the intricate relationships among the constituent entities within complex systems [46].

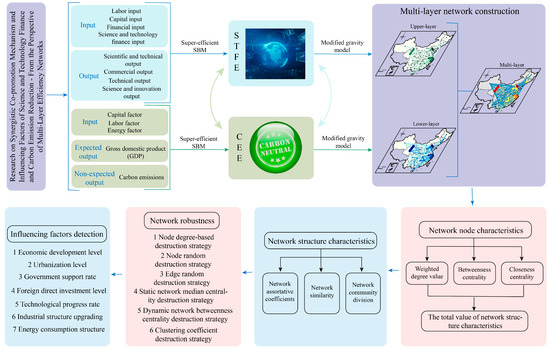

In this article, we build an MN of STFE and CEE from a global spatial perspective using the social network analysis method, and to explore the regional differences in their mutual influence and synergistic development mechanism based on spatial and temporal perspectives, with the intention to supplement the gaps within the field of STF research and broaden the research scale of CEE, which have important reference significance and policy insights for the promotion of the synergistic effect of STF and lowering carbon emissions, as well as the development of a virtuous circle among regions. The following are the article’s marginal contributions: First, innovative use of multi-layer complex network ideas for the construction of an MN of STFE and CEE, and an in-depth investigation of the node characteristics of the MN structure, network assortativity relationship and similarity, as well as community division and network robustness. Second, a more systematic and comprehensive approach reveals the mutual influence paths between the two systems of STFE and CEE, as well as their interactions within the network. Finally, the article broadened the research perspectives and scales of STF and carbon emissions, and deeply analyzed the mutual influence mechanism in the spatial structure, which is of great significance for the formulation of coordinated and co-promotional policies with differentiation by various regions and relevant departments. The research framework is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research framework.

2. Influencing Mechanism

2.1. Impact Pathways of STFE on CEE

In an attempt to provide more clarity on the impact path of STFE on CEE, this article tries to analyze and elaborate on following three aspects. Firstly, the improvement of STFE will promote economic growth and thus enhance CEE. Rooted in New Economic Growth Theory [47], the integration of science–technology and finance drives economic growth by leveraging the cumulative effect of human capital and the spillover effect of technological capital [8,9]. The new structuralism in economics considers technological progress as an important driving force for economic growth [48]. The advancement of STFE enhances the level of technological innovation and transformation in financial services, thereby driving technological progress and fostering rapid economic growth. The high-quality economic development produces a regional economic agglomeration effect, and at the same time, the corresponding region’s concern for environmental issues is increasing, and the relevant departments will invest more funds to combat environmental pollution and other issues, and promote regional low-carbon development, with the speed of economic development becoming faster than the speed of carbon dioxide emissions, so that CEE can be improved. Secondly, STFE will also improve CEE by improving the green technological innovation level [12,17]. Green technical innovation is essential for achieving low-carbon development and encouraging businesses to save energy and reduce emissions, while technological innovation and STF funding are inextricably linked. Financial innovation and scientific and technological innovation synergistic development of the STF innovation system causes the interaction between them to spiral upward, forming a technological and financial innovation driving effect, and thereby promoting green technological innovation [49]. Innovation in green technology advances the production and application of clean energy, reduces energy consumption, realizes the decarbonization of energy consumption, and thus improves CEE. In addition, the new technologies and products brought about by green technology innovation will greatly increase energy use efficiency and accelerate the transformation of industrial structures to green and advanced development, thus optimizing the structure of energy consumption and ultimately improving CEE. Finally, STFE improves CEE by increasing the financing capacity of enterprises. With the emergence of STF, Sci-Tech innovation investment and financing platforms, Sci-Tech financial branches and Sci-Tech microfinance companies and other lending institutions have emerged. The continuous improvement of the financing mechanism makes the relevant Sci-Tech enterprises obtain more sufficient financial support, which is conducive to alleviating the constraints of enterprise innovation financing, and the enhancement of the financing ability creates good conditions for businesses to engage in innovative scientific and technology activities, stimulating the innovation vitality of enterprises, and further promoting the transformation of the development of enterprises and modernization of the industrial structure, so as to lower carbon emissions and improve CEE.

2.2. Impact Pathways of CEE on STFE

By virtue of its superior Sci-Tech and financial resources, STF has played a great role in enhancing CEE in many aspects. Meanwhile, CEE also plays a guiding and driving role in improving the STFE, by enforcing the industrial structure’s green transformation, developing and transforming associated businesses, and increasing the effectiveness of resource allocation. Accordingly, the impact path of CEE on STFE will be elaborated upon, in the following three basic ways. Firstly, the improvement of CEE forces the industrial structure’s green transformation [50]. Under the active promotion of the “double carbon” target, it is certain that CEE will improve as a result of the relevant sectors using more clean energy and progressively shifting to high-level, low-carbonization and rationalization of their industrial structure. Technology development and funding sources cannot be separated from the support of STF, which will in turn lead to the improvement of STFE. Secondly, the improvement of CEE forces the transformation and progress of related enterprises [37]. Regarding the low-carbon environmental protection development paradigm trend, government financial allocations and financial institutions loans will lead to the emergence of technology enterprises and low energy consumption enterprises. Under the basis of improving CEE, all relevant enterprises will improve their governance level, optimize their enterprise structure, and innovate their development methods to meet the financing requirements. Therefore, the environmental policy driven CEE improvement helps to force enterprises to aggressively pursue technological innovation in energy-saving and emission-reducing fields, improve the management level, and promote their innovation and transformation development, thus improving the STFE. Finally, increasing CEE has a positive impact on increasing resource allocation efficiency [51]. On one hand, it will reduce costs and improve enterprise competitiveness by optimizing the use of resources. On another hand, expanding the production scale of enterprises will drive loan financing to financial institutions and boost the degree of technical innovation of businesses, thus promoting the development of STFE. In addition, the enhancement of CEE will optimize the structure of practitioners in financial institutions and Sci-Tech enterprises through the adjustment of human capital allocation in related industries, and promote the technical and management level of professionals, which will have an impact on STFE.

2.3. Interaction of the STFE and CEE in the Network

The spatial network structure is the distribution pattern of resources including population, capital, and technology in the regional space, and the nodes in the network space form an interactive relationship through the agglomeration and diffusion of factors [52]. The flow and diffusion of scientific and technical advances and financial components in the network increases the exchange of economic activities between regions and narrows the differences in STFE in each region. At the same time, the network reveals inter-regional linkage, and optimizing the network structure is conducive to the balanced distribution of resources, providing the necessary conditions for input–output maximization, and improving the productivity and innovation conversion rate, thus making a positive impact on CEE and the environment. Accordingly, both the STFE and the CEE system will be affected by the network.

However, the STFE network and the CEE network are not two independent network systems, and mutual propagation and flow of resource elements occur between different networks, leading to an interactive effect between the networks. The technological and financial resources in the STFE network affect the regional CEE through spatial diffusion, and similarly, the human, capital, and energy elements in the CEE network also affect the development of the STFE. The mutual influence between the two networks is conducive to improving the problem of a single network being affected by a single factor, and can further promote the synergistic development of the two networks through the effect of resource diffusion and optimal allocation, which is conducive to forming a cooperative relationship of complementary functions, enabling the nodes of the networks to fully utilize their regional strengths, so as to enhance each development’s efficiency.

3. Research Methodology and Data Description

To examine the spatiotemporal synergistic evolution of STFE and CEE, this study first measures both using the super-efficiency SBM model. A Multi-Layer Network is then constructed to analyze structural features, assortativity, network similarity, and community division. Furthermore, network robustness is assessed to evaluate the MN’s resilience to risk. Finally, Geo-detector analysis identifies the factors influencing the MN structure, providing an empirical foundation for its optimization.

3.1. Super-Efficient SBM Model

Due to the conventional DEA model, which ignores elements like the external environment, random variables, and non-expected outputs, there are some deviations in the measurement of the results. In this article, we measure the STFE and CEE based on the non-radial and non-angle super-efficiency SBM model, which incorporates the non-expected outputs into the calculation framework and introduces relaxation variables to effectively improve the measurement accuracy. The model was developed by [53], and the specific calculation formula is shown below as follows:

where is the target efficiency value and , , are the inputs, desired outputs, and non-desired outputs, respectively. , , denote the slack in inputs, desired outputs, and non-desired outputs, respectively. is a vector of weights.

3.2. Establishment of Multi-Layer Networks

3.2.1. Single-Layer Network Construction

To measure the network effect of a single system, a single-layer network is constructed. The traditional gravity model usually measures the spatial correlation strength between two regions with regional population and regional GDP as the key indicators, and lacks a systematic description of the comprehensive development between regions. Therefore, building upon the traditional gravity model, this article employs a modified version to delineate the spatial evolution of the STFE and CEE networks, and the form is as follows:

where is the adjustment factor, which is usually multiplied by a constant to facilitate the observation of the results. and represent the CEE network and the STFE network, respectively, and their indices are denoted by and , while represents the strength of correlation between any two points in the CEE network, and represents the correlation strength between any two points in the STFE network, and is the square of the spatial distance between points and .

3.2.2. Multi-Layer Network Construction

A Multi-Layer Network is built to examine the relationship between two networks. Recognizing that provinces within the core network exhibit stronger linkage intensity than ordinary node provinces, this study focuses its analysis on the core network. To highlight the interconnections among core nodes, an association matrix is constructed using the average value of inter-period linkages as the threshold, and this method accounts for spatial network distribution while adhering to the principles of information validity and comparability. In the formula, different superscripts represent different network layers: is the set of nodes, is the set of edges, and is the set of edge weights.

Here, is the upper-layer network, and is the lower-layer network; the upper and lower layers are directly associated, and the nodes between the two layers correspond to each other, one by one. We set the function of the Multi-Layer Network as function (8), where and are the CEE network and STFE network, respectively. Then, and are the weight values of the upper and lower layers, so set the weight relationship of the connected edges as = = 0.5. When measuring the Multi-Layer Network composed of science and technology finance efficiency (STFE) and carbon emission efficiency (CEE), the selection of equal weights (i.e., identical weights for each layer) is primarily based on the following scientific considerations.

First, this decision is grounded in theoretical foundations and model consistency. The primary objective of the coordinated development model employed in this paper is to gauge the degree of interactive coordination between systems, rather than to assess the absolute efficiency of any individual system. As elucidated in our analysis of the influencing mechanism, STFE and CEE are characterized by a reciprocal relationship of mutual influence and reinforcement. Treating these subsystems (STFE and CEE) as independent dimensions of equal significance, and consequently assigning them identical weights more accurately captures their synergy while mitigating potential biases associated with subjective weighting methods. This approach is consistent with the established logic in coupling models that treat carbon emissions and other variables (such as economic and social factors) equally, ensuring the model’s neutrality and comparability [54,55,56,57,58,59].

Second, this approach is grounded in data constraints and the rationale for methodological simplification. Collecting data that captures the nexus between STFE and CEE in China is currently fraught with significant challenges, involving impediments at both governmental and enterprise layers. Governmental data is characterized by fragmentation across disparate departments, including departments of environmental protection, finance, development and reform, and science and technology. This compartmentalization, coupled with a lack of unified standards and sharing mechanisms, impedes effective cross-regional and cross-industry integration. Additionally, selective disclosure by some local governments, driven by privacy concerns or pressures from performance appraisals, undermines data completeness. On the corporate front, particularly among small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), there is often a lack of technical capacity to systematically track carbon emissions or STFE input-output ratios. Furthermore, cost considerations result in a lack of incentive for voluntary data reporting. Adding to this challenge is the complexity of the STFE-CEE relationship (e.g., the non-linear effects of green innovation), which demands multi-dimensional indicators. The failure of current statistical systems to capture these dynamic interactions further widens the data gap.

Therefore, due to a lack of definitive a priori knowledge or compelling evidence that one subsystem contributes disproportionately to overall coordination, equal weighting represents a robust and conservative default. This strategy simplifies model configuration and mitigates the risk of distortion arising from subjective weight assignment, rendering it highly appropriate for exploratory studies or preliminary analyses.

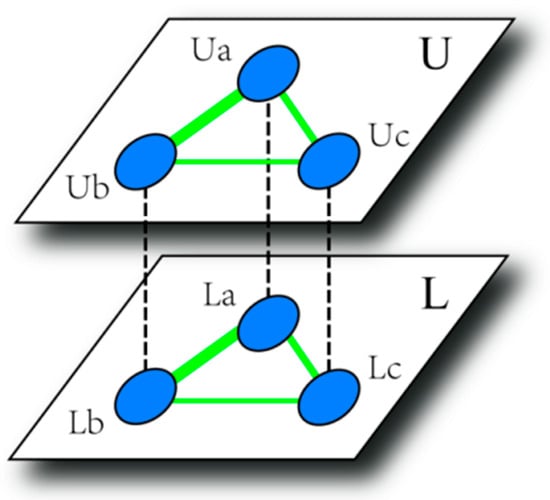

The correlation diagram of the MN is shown in Figure 2:

Figure 2.

Diagram of Multi-Layer Network correlations.

3.3. Characteristic Indexes of Multi-Layer Networks

3.3.1. Network Node Characteristics

This article employs weighted degree, betweenness centrality, and closeness centrality to measure interprovincial network linkage strength and external spillover effects.

- The weighted degree value: The degree value of a node indicates the total number of connections, and this article adopts the weighted degree value of MN to measure the overall degree of connectivity and control ability of provinces in the network.

- Betweenness centrality: Betweenness centrality captures a node’s influence over others and its control of network resources, while betweenness centrality specifically quantifies the proportion of all shortest paths passing through the node, measuring its role as an intermediary in connecting other nodes.

- Closeness centrality: Closeness centrality reflects a node’s average distance to all other nodes in the network. A node with higher closeness centrality occupies a more central position and thus holds greater structural importance within the network.

3.3.2. Characteristics of Inter-Layer Association of Multi-Layer Networks

- Network assortativity coefficient: The network assortativity coefficient quantifies the degree correlation between nodes in the upper and lower layers of an MN. A positive coefficient indicates an assortative network, where high-degree nodes in one layer connect to high-degree nodes in the other, and low-degree nodes connect to low-degree nodes. Conversely, a negative coefficient signifies a disassortative network, characterized by connections between high-degree and low-degree nodes across layers, where and represent the degree values at both ends of an edge, and E denotes the total number of edges in the network.

- Network similarity: Based on studying the mating relationship between nodes of MN, the similarity exploration of the structure between the upper and lower layers of the network is also necessary to analyze the synergistic development of the two different systems. In this article, the common neighbor similarity is chosen to measure the network similarity. If the number of common neighbors of the upper and lower layer networks is greater, it means that their similarity is higher, and vice versa for when it is lower. The idea is based on product networks, where and are, respectively, the adjacency matrices, is the transpose matrix, and is the similarity of the two matrices at the st iteration, whose value is a number from to . The closer the value is to n, the more similar the MN is.

3.3.3. Community Division of Multi-Layer Networks

A community division method based on modularity was developed by [60], followed by related literature extending the modularity approach to the field of MN research in 2010 [61]. The core idea is to consider a single node in a network as a community and merge the communities under the constraint of maximizing the modularity function to form a community partitioning structure with a similar structure or function. Since many studies have been conducted to analyze network community division, its formulation will not be repeated here.

3.4. Network Robustness: Analysis on the Function of Multi-Layer Networks

Networks often face disturbances that cause them to collapse suddenly. Network robustness refers to the capacity of a network to preserve its fundamental topological structure and core functions when subjected to internal failures or external disruptions. An in-depth look at the performance of network robustness can help to build more resilient and destruction-resistant network structures. Among them, the and are the sums of the shortest paths before and after the destruction, respectively, and their ratios can reflect the damage of the network structure in the face of different levels of destruction.

3.5. Geo-Detectors: Analysis of Influence Factors of Multi-Layer Networks

This study employs Geo-detector methodology, specifically factor detection and interaction detection, to analyze the spatiotemporal heterogeneity of influencing factors. Factor detection quantifies the explanatory power of each factor on network structure metrics using the q-statistic. The formula is

The q-statistic, ranging from 0 to 1, measures the explanatory power of each influencing factor on the dependent variable, with higher values indicating a stronger explanatory capacity. Here, h denotes the number of strata in the detection factor, N and represent the total sample size and variance, and and denote stratum sample size and variance, respectively. Interaction detection is a measure of whether the interactions of the influence factors strengthen or weaken the effect on the explained variables.

3.6. Indicator System and Data Sources

3.6.1. Evaluation Indicator System for STFE

To synthesize the existing literature [62] on the selection of indicators for evaluating the STFE and CEE, and to ensure that the inputs and outputs are truly and effectively reflected, the following indicator system is constructed. This article determines the input indicators of STFE from four aspects—labor input, capital input, financial input, and STF input—and then selects the corresponding output indicators from four perspectives: scientific and technological output, commercial output, technical output, and science and innovation output. In terms of input indicators, the full-time equivalent of R&D personnel is selected to reflect the human capital of scientific and technological activities in each region, the internal expenditure of R&D funds is selected to reflect the research expenditure on scientific and technological activities and experimental development within enterprises and public institutions, the financial allocation for Sci-Tech is selected to reflect the government’s support of science, technology, and innovation activities, and the Sci-Tech loans from financial institutions are selected to measure the financial industry’s support for Sci-Tech development. For output indicators, this study selects the number of patent applications to reflect regional scientific and technological activity, technology market turnover to quantify commercial STF output, main business income of high-tech industries to assess regional high-tech industry development, and sales revenue of new products to measure scientific and technological innovation outcomes. The specific variables of inputs and outputs are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Science and technology finance efficiency indicator system.

3.6.2. Evaluation Indicator System for CEE

According to the connotation of CEE, this article constructs CEE input indicators in terms of the capital factor, labor factor, and energy factor. The capital factor is estimated using the perpetual inventory method [63], with 2000 as the base year to derive provincial capital stock. Labor is represented by year-end employment figures, and energy is measured by provincial energy consumption. Expected output is defined as provincial GDP, while undesirable output is provincial CO2 emissions, calculated by applying energy-source-specific emission factors from the IPCC’s 2006 Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories. Specific variables are detailed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Carbon emission efficiency indicator system.

This study examines 30 Chinese provinces (excluding Xizang, Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan) from 2011 to 2020, based on data availability and reliability. Data are primarily sourced from the China Statistical Yearbook, China Science and Technology Statistical Yearbook, China Torch Statistical Yearbook, and China Energy Statistical Yearbook.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Overall Evolution of the Spatial Structure of Multi-Layer Networks

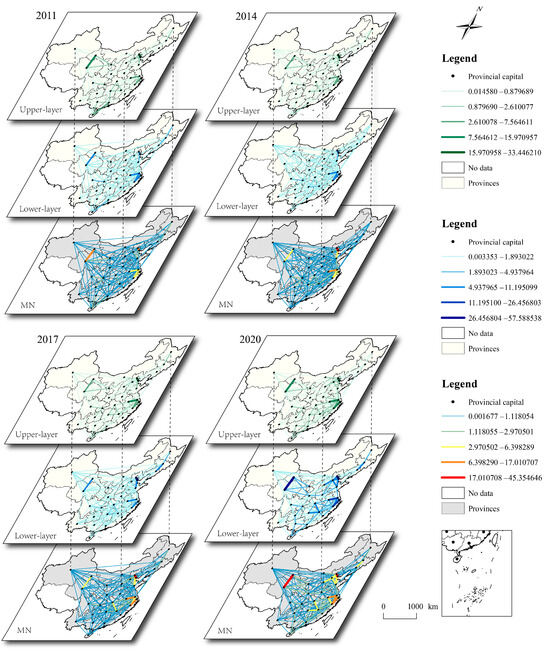

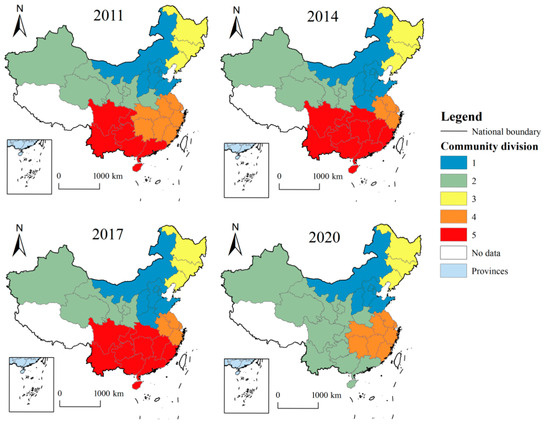

To better capture the evolving trends and dynamic structural shifts within the upper-layer, lower-layer, and MN spatial configurations, this article relies on the ArcGIS 10.7 visualization platform, and due to space limitations, four-time points as 2011, 2014, 2017, and 2020 were selected to visualize the network structure, as shown in Figure 3 (the upper-layer is the CEE network, and the lower-layer is the STFE network).

Figure 3.

Evolution of the Multi-Layer Network structure, 2011–2020.

Generally speaking, the correlation between the STFE network, the CEE network, and the coupled MN shows a spatial pattern of decreasing from the east coast to the inland area, and a spatial pattern of spreading to the Midwest regions. The eastern coast is mainly concentrated in the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei (BTH) region, which is centered on Beijing, and the Yangtze River Delta (YRD) region, which is centered on Shanghai, while the Midwest regions radiate to the rest of the country through the pattern of “two points and one belt”. The spatial structure of the MN exhibits a clear trend toward integration and coordinated development between its upper and lower layers, while also highlighting distinct spatial orientation and path dependence. Specifically, as the administrative subject and the provinces located in the center of power show a strong network connection, the spatial pattern shows the characteristics of the diffusion and driving role of the central nodes in the network.

Looking at different years separately, from 2011 to 2014, the network structure is not yet clear and the overall connectivity is weak. The core–edge structure of the network is obvious, and the center of the network shows a sparser network relationship with other regions. Maximum connectivity emerges primarily among three regions: the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei (BTH) region centered on Beijing, the Yangtze River Delta (YRD) region centered on Jiangsu and Zhejiang, and the Qinghai–Gansu region, giving rise to a tri-centric, multi-zonal network structure. This is inextricably linked to the rich Sci-Tech financial resources in the BTH and YRD regions and the environmental policies implemented by the government. The eastern coastal region is actively building an STF system, and elements such as scientific and technological innovation and financial capital are becoming increasingly sufficient to improve the STFE, and the Qinghai–Gansu areas have high CEE by virtue of their lower energy consumption and carbon emissions, thus presenting a significant radiation effect. From 2017 to 2020, with the flow and dissemination of financial, technological, and talent resources in spatial network structure, the node provinces dominated by network centers gradually spread their connections outward, with an overall high degree of network connectivity and a gradually stabilized pattern. The network connection gradually radiates from the eastern coastal area to the Midwest parts of the country, and the upper and lower layers of the network show a highly similar evolutionary trend, and the MN structure manifests the synergistic development of the two. Specifically, the Hubei–Hunan–Jiangxi triangle network structure began to emerge, and the network connection of the Pearl River Delta (PRD) region centered on Guangzhou was strengthened. Hubei, as a national transportation hub center, has frequent economic exchanges with other regions, and has both geographic location advantages and resource endowment conditions, which makes its network connection with various regions gradually strengthened and drives the formation of network center structure around it. In Guangdong, on account of the emphasis and development of the Shenzhen Science and Technology Bureau on STF and its developed economy, the network structure of the PRD has been significantly strengthened.

4.2. Characterization of Multi-Layer Network Structures

Based on the analysis of the spatial evolution of the overall network structure, to further explore the position and role of different provinces in the network, this article selects three network structure characteristic indicators, namely, weighted degree value, betweenness centrality, and closeness centrality, to analyze the characteristics of networks.

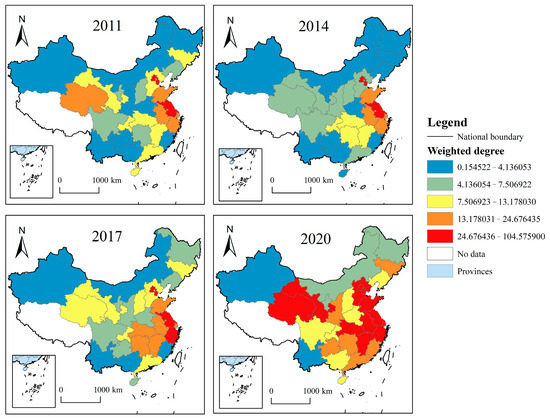

4.2.1. Spatial and Temporal Evolution of Weighted Degree Value

In terms of the spatial evolution pattern of the weighted degree value (Figure 4), generally speaking, the high-value areas are mainly concentrated along the eastern coast, and show a trend of gradual spreading to the Midwest regions. The high-value areas are predominately situated in Beijing, Tianjin, and Jiangsu, indicating that the above provinces are in the center of the network as they have more connections and are more related to other provinces. As important political and economic development centers, the BTH and YRD, under the policy background of a combination of Sci-Tech and finance and the active implementation of the “double-carbon” goal, play a stronger role in promoting the synergistic effect of STFE and CEE, which leads to a stronger network relationship and spatial spillover effect in the region. On the other hand, the Midwest regions, due to their remote geographical location and small economic scale, are at the fringe of the network and are more dependent on the technology, talents, and other resources of the economically developed regions. With the spread of financial, technological, and other elements in the network, the overall network connectivity is increasing. By 2020, the Midwest regions and the eastern coastal regions reflect a remarkable correlation, and the Gansu and Qinghai regions reach the highest level of weighted degree value. Qinghai vigorously carries out the ecological province’s plan, and from the practice of ecological civilization for construction, the total amount of carbon fixation by the ecosystem in Qinghai is the first in the country, represented by a huge surplus of carbon sinks. Gansu, as a province with high energy consumption intensity in Northwest China, actively adjusts the industrial structure and promotes energy saving, such that the correlation of the network with other regions is gradually increasing.

Figure 4.

Four-year comparison of the evolution of spatial patterns of weighted degree values.

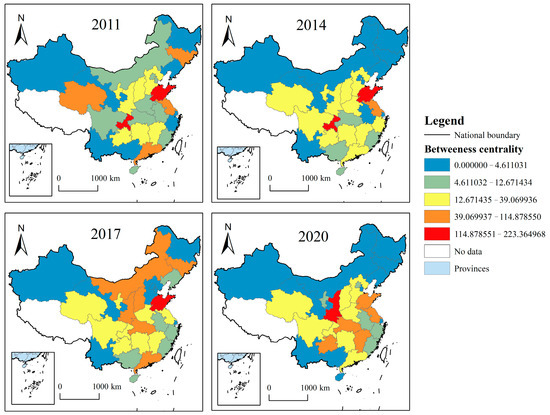

4.2.2. Spatial and Temporal Evolution of Betweenness Centrality

In terms of the spatial evolution pattern of betweenness centrality (Figure 5), in general, the high-value regions are not strongly spatially clustered and are scattered in a point-like manner, while the low-value regions have not changed significantly over the four-year period. The first echelon of high-value regions is mainly located in Shandong, Chongqing, and Shaanxi, indicating that these regions play an “intermediary” role in the flow of resources with other regions, and help establish spatial correlation between the peripheral nodes and the center nodes of the network. Shandong’s recent introduction of carbon emission reduction alternatives for the “two high” industries has effectively curbed carbon emissions. In addition, Shandong benefits from abundant energy resources and has strong control over the transfer of carbon emissions among other provinces. Chongqing, as the financial center of Southwest China, plays an important role as a “bridge” for the dissemination of Sci-Tech, finance, and other resource elements. The decline in betweenness centrality in Shandong and Chongqing indicates a reduced capacity to mediate inter-provincial linkages, while Shaanxi shows a trend of changing from a controlled to a controlling role, with strong “intermediation” power. Jiangsu, Guangdong, and Hubei, the second tier of high value, as well as the northern region with its high energy consumption, have gradually emerged as intermediary controllers in the evolution of the network. The rapid development of STF in Jiangsu and Guangdong has had a driving effect on the dissemination and diffusion of Sci-Tech and financial resources in the neighboring regions. Leveraging its unique geographic advantages, Hubei serves as a key intermediary linking the eastern and western regions, demonstrating the strong intermediary capacity of the network.

Figure 5.

Four-year comparison of the evolution of the spatial pattern of betweenness centrality.

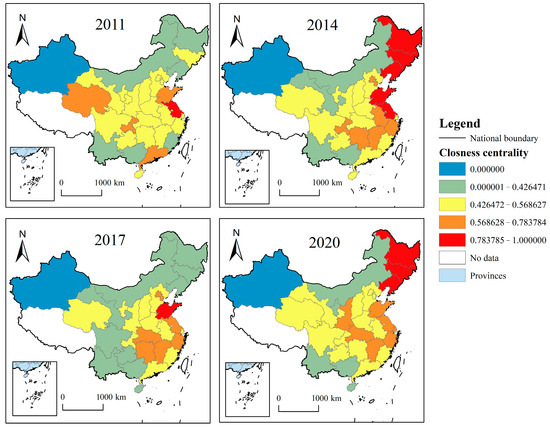

4.2.3. Spatial and Temporal Evolution of Closeness Centrality

In terms of the spatial evolution pattern of closeness centrality (Figure 6), in general, coastal areas are at the center of the overall network space, and the high-value areas are characterized by a fluctuating tendency to first rise, then fall, and finally rise again. Closeness centrality measures the distance between a node and other nodes; the shorter the distance between a node and other nodes, the higher the information transmission capacity of that point is, and the more likely it is to reside in the center of the network. High-value regions are mainly focused on Northeast, North, and East China, with strong control and dominance over Sci-Tech financial resources, and the above regions have a greater benefit relationship than spillover relationship for the improvement of CEE. As the technology revolution and industrial transformation continues to progress, the development of STF provides new opportunities for the revitalization of the northeastern industrial chain. As the industrial structure is actively being developed and transformed, the northeast region has effectively controlled energy consumption, which has greatly contributed to the improvement of CEE. The Midwest regions have a lower and marginal position in the network, and the overall closeness centrality value is low, but there is a trend of gradual increase. Among them, Xinjiang’s closeness centrality is zero for all four years, indicating that it is more difficult to create an intrinsic connection with other provinces, and even less likely to approach the center of the network. Qinghai, as a region with high CEE, has a decreasing trend of betweenness centrality and closeness centrality, although its spatial association with the overall network is gradually increasing. Due to its marginalized network status and backward level of economic development, its STFE is far behind its CEE, and the two independent systems have not shown good synergistic development, so it is more dependent on other regions in the network space, and shows a weaker controlling ability.

Figure 6.

Four-year comparison of the evolution of spatial patterns of closeness centrality.

4.2.4. Trends in the Evolution of the Total Value of Network Structure Characteristics

The previous section analyzed the spatial evolution trend and regional temporal and spatial heterogeneity of the three network structure characteristics of weighted degree value, betweenness centrality, and closeness centrality, and to further reveal the changes in the total value of the three in the upper and lower layers and the MN, and explore how the STFE network and the CEE network can be synergistically developed, and thus the graphs of the evolution trend of the total value of the three network structure indicators are shown here separately to facilitate observation and in-depth analysis. As shown in Figure 7, the total value of network indicators in the lower-layer network and the MN show a highly similar evolution trend, indicating that the STFE plays the role of a central subject in the overall network and exerts significant control over the upper-layer network. The STFE network “transports” financial resources, scientific and technological means, and human capital to the CEE network through inter-layer correlation, influencing its network structure and further optimizing the MN constructed, which is in line with the influencing mechanism analysis in the previous section. Among them, the total value of the weighted degree shows a significant rising trend and reaches the peak value in 2020, and the betweenness centrality represents a undulant upward trend and the total value changes greatly in different years, while the closeness centrality represents a fluctuating and stable tendency, and the overall total value basically stays unchanged from 2011 to 2020, and then changes greatly during the study period. In addition, the weighted degree value of the MN is not higher than the total value of the upper and lower networks, while the betweenness centrality and closeness centrality of the MN are notably higher than those of the single-layer network, demonstrating that the nodes of the MN structure show higher mediational control ability and shorter “distance” to network center. This provides compelling evidence that the multi-layer structure enhances the intermediary control capability of nodes within the overall network, effectively shortens the distance between nodes, and improves the efficiency of information and resource flows.

Figure 7.

Trends in the total value of network structure indicators.

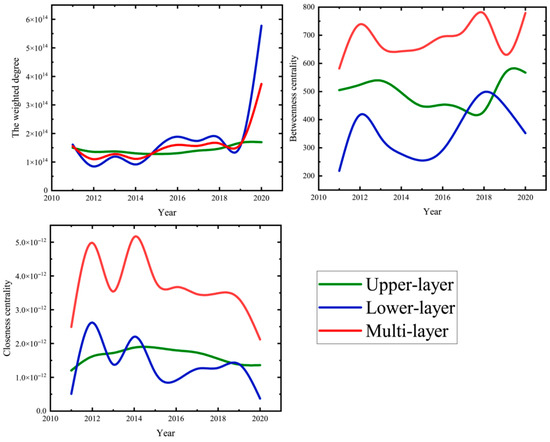

4.3. Network Assortative Coefficients and Similarity

To better reveal the overall structural characteristics and coupling of the MN, the network assortative coefficient and similarity are selected to measure the connectivity between different layers of the network and the similarity of different nodes in different layers. From Figure 8, the network assortative coefficients are all negative and fluctuating upward during the study period from 2011 to 2020, indicating that the network layers are in the mode of disassortative connection. The reason for this may be that the financial system is rich in objects and complex relationships, and is in constant change. In the financial market, there are many problems such as information asymmetry, resource mismatch, and market inefficiency. Financial networks are sparse, with a lot of indirect connections in the network, and therefore often exhibit disassortative relationships. With regard to the CEE network, as more non-core network connections in the periphery gradually increase, carbon emission transfers will probably occur between nodes with low similarity, and the degree of network aggregation decreases. According to the analysis of the coupling situation between the STFE network and the CEE network, it can be seen that the nodes of large degrees in the STFE network will exert their unique advantages in Sci-Tech and financial resources to guide and drive the ability of the nodes of small degrees in the CEE network to improve, so as to make the MN structure more stable and superior, and thus there is a disassortative relationship between the two layers of the network. With the diffusion of resources and the evolution of the division of labor pattern, the coefficient of heterogeneity is gradually increasing and the disassortative relationship is gradually decreasing, indicating that the pace of development of each system of the MN becomes more consistent and the synergistic tendency is increasingly visible.

Figure 8.

Trends in network assortative coefficients and similarity.

The node similarity metric based on common neighbors measures the proximity between two nodes. From Figure 8, it can be seen that the similarity between network layers is increasing with a significant rise and reaches a highest point in 2020. It indicates that after connecting the upper and lower layers of the network by correlation, the nodes of different network layers become more and more similar. It can be realized that the STFE network and the CEE network reflect a synergistic development trend. On the one hand, in recent years, the policy environment of STF has gradually become perfect, with the eastern coastal region occupying the absolute advantage and the Midwest areas continuing to catch up. Fiscal policy has gradually tilted to the Midwest regions, and financial support for Sci-Tech development has gradually developed towards market-oriented development, gathering rich scientific research talents and scientific and technological resources, and the emergence of various types of incubators and crowd source spaces has effectively improved innovation vitality and alleviated the disparity of the level of STFE between regions. On the other hand, under the positive influence of green innovation technology level improvement and enterprise financing efficiency enhancement, the CEE of each region has also been significantly improved, forcing relevant industries to upgrade their industrial structure and transform their enterprise development, thus forming a benign pattern in which the economic effect and the environmental effect are both favorable.

4.4. Structure of Community Division

Based on the optimization of the modularity function for community division of MN structure, community division structure is formed by merging or separating associations to observe and explore the evolution trend of community structure in the overall network. A community is a collection of closely related nodes in a network, with tight connections between communities within the community and looser connections between nodes in different communities. As shown in Figure 9, the MN structure was divided into five communities in 2011~2017, and the number of communities shrunk to four by 2020, indicating that the construction of the MN is conducive to the cohesion of the community structure, which can effectively alleviate the problems of unbalanced and insufficient regional development. From 2011 to 2014, the community structure in Northeast China remained unchanged, while North China merged with Henan to become a new community, and Southwest China expanded to the east to merge with Central and South China to become a larger community structure. This shift correlates with the in-depth advancement of China’s “The Rise of Central China” and “Large-scale Development of Western China” The merger of North China and Henan reflects the integration effects of the Central Plains Economic Zone, while the fusion of the Southwest and Central–South regions mirrors the strengthened economic ties between the Chengdu–Chongqing Economic Zone and the Urban Agglomeration in the Middle Reaches of the Yangtze River. From 2012 to 2013, China experienced a transitional period of regional economic development, and the “polarization” and “diffusion” effects of the regional economy were more pronounced than ever before. With its rich natural resources and developed resource-based industries, Southwest China’s economic growth rate surged during this period, with high export growth and huge potential for opening up, and the gap between this region and Central and South China gradually narrowed. The structure of this association remained unchanged from 2014 to 2017. The reason for this is that, against the backdrop of regions actively practicing the national strategy of promoting coordinated regional development, China’s overall regional development is in good shape and is moving forward in multiple directions, and the coordination of regional development is increasing. From 2017 to 2020, the northwest region downwardly merged with the southwest region to become the largest association structure, while the Yangtze River Delta region of East China broadened its boundaries to the west, to include three more provinces: Hubei, Hunan, and Jiangxi. This change is closely related to the longitudinal advancement of the “Yangtze River Economic Belt” and the formation of a new pattern in the “Large-scale Development of Western China”. Provinces with lower levels of economic growth agglomeration are mostly reflected in the northwest and southwest regions, and as regional integrated growth progresses, the northwest and southwest regions evolve into one community, which will help the southwest region to drive the northwest region to improve the STF, and meanwhile, the northwest area’s low-energy-consuming mode of economic development and the characteristics of industrial structure will also increase the southwest region’s CEE, thus forming a two-way promotion pattern. This structural adjustment also resonates with the national strategic orientation of fostering a “regional economic layout featuring complementary advantages and high-quality development”, further reinforcing the role of the Multi-Layer Network in cross-regional resource integration and green development synergy.

Figure 9.

Four-year comparison of the evolution of the spatial pattern of the community division structure.

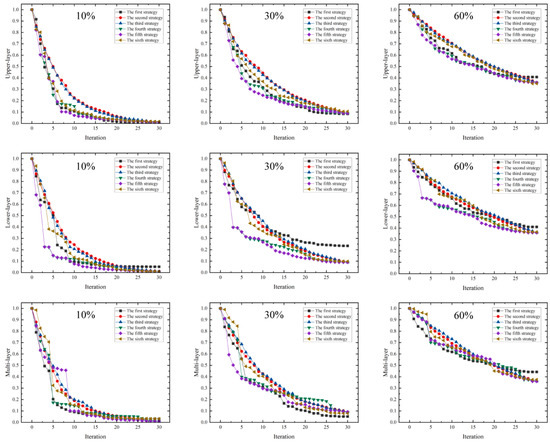

4.5. Network Robustness Test Results

Exploring whether the coupled connected MN has stronger destruction resistance, i.e., higher network robustness, than the single-layer network is of great significance for the design of destruction-resistant network structures. Figure 10 shows the changes in each index in the upper CEE network, the lower STFE network, and the MN when they are damaged by different degrees and different strategies, and the horizontal axis indicates the evolutionary trend of the network robustness indexes with the increase in the quantity of damaged nodes when they are attacked by different strategies, and the vertical axis indicates the ratio of the shortest total path lengths before and after the damage. The six strategies are node degree-based destruction strategy, node random destruction strategy, edge random destruction strategy, static network median centrality destruction strategy, dynamic network betweenness centrality destruction strategy, and clustering coefficient destruction strategy, and the degree of destruction is selected to retain 10%, 30%, and 60% of the network structural abilities.

Figure 10.

Network robustness with different destruction strategies.

The results indicate that across all attack scenarios, the destruction strategy based on node-betweenness centrality (particularly the dynamic strategy) consistently exhibits the highest destructive power. This suggests that in the actual regional economic system, provinces occupying key hub positions that carry substantial cross-regional flows of resources and emissions will, once impacted, inflict the most severe impact on the overall network’s effectiveness.

As can be seen from Figure 10, with 10% of the node capacity retained, the network robustness performance of the upper-layer and lower-layer network decreases the slowest when they are attacked by the nodes’ random destruction strategy, and fluctuates the most when they are attacked by the dynamic network betweenness centrality destruction strategy, especially when the lower-layer network decreases from 0.6 to 0.2 when it is undergoing the third iteration, which indicates that the nodes with large betweenness centrality are attacked first and the least resistant to the attack. The MN, on the other hand, shows different results from the upper and lower single-layer networks, as it is most affected by the node degree value destruction strategy, and the various strategies are more convergent in terms of the decrease in the attack. Although the betweenness centrality strategy still shows a steep decline, it appears after the number of iterations gradually increases, indicating that the MN structure has been better optimized than the single-layer network, and the nodes with large betweenness centrality values have better resistance to destruction. In the case of 30% of retained node capacity, again, it is most affected by the betweenness centrality destruction strategy, while the performance of the network edges shows better resistance. At 60% of retained node capacity, the network performance degradation is significantly lower, and the trend for each destruction strategy remains essentially the same.

Comparing the decline and trend of network performance in different nodes’ capacity retention values, it can be seen that the MN reduces the degree of destruction and gap size of the single-layer network under different strategies, indicating that the coupled and connected MN can improve the robustness of the system and weaken the risk of having a strong destructive strategy such that the network is not subjected to a single disturbance experiencing a collapse and paralysis. Consequently, designing stable network structures should prioritize nodes with higher betweenness centrality. Meanwhile, the above analysis of the temporal and spatial evolution of betweenness centrality shows that the areas with high betweenness centrality values only exist in a few regions, and the range tends to shrink gradually. Accordingly, centrality plays a role in connecting nodes and transferring resources in the network, and nodes with higher betweenness centrality play a crucial role in the network structure against the background of unbalanced regional economic development, unbalanced distribution of Sci-Tech and financial resources, and significant differences in the pattern of CEE in China.

5. Detection of Influencing Factors

To explore the factors affecting the differences in the evolution of MN structure, this article will draw on the literature to select the influencing factors from the impact of STFE and CEE, respectively, and use the ArcGIS 10.8 natural breakpoints to discretize the influencing factor data that has been detected with the help of Geo-Detector software.

5.1. Selection of Impact Factors

Drawing on relevant research findings [64,65], this article selects a total of seven influencing factors, namely, economic development level (EDL), urbanization level (UL), government support rate (GSR), foreign direct investment level (FDI), technological progress rate (TPR), industrial structure upgrading (ISU), and energy consumption structure (ECS), and explores their influencing effects on the value of weighted degree, betweenness centrality, and closeness centrality of MN, respectively. The related data description is shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Selection of influencing factors and data description.

5.2. Analysis of Single-Factor Impact Results

Table 4 demonstrates the results of detecting the network weighted degree value, betweenness centrality, and closeness centrality for each influence factor for the four periods of 2011, 2014, 2017 and 2020, respectively.

Table 4.

The explanatory power of influencing factors by year period (based on q-statistics).

From the results of the selected influencing factors on the weighted degree value, on the whole, the EDL, GSR, and ISU have the strongest influence on the weighted degree value, but their influence generally shows a downward trend. The influence of the UL, TPR, and ECS is gradually increasing, playing an increasingly important role in the MN association. Among them, the explanatory power of the GSR on the weighted degree value is higher overall, in the range of 0.35 to 0.7. In addition, both the EDL and the influence size of the GSR gradually decreased from 2011 to 2020, while the ISU shows a fluctuating downward trend. This indicates that the effect of the differences in the EDL, the differences in government financial support and policies, and the uneven upgrading of industrial structure in various regions on the enhancement of the association of each node of the network gradually decreases. The explanatory power of the UL on the weighted degree value is 0.1~0.3 in 2011–2017, and up to 0.531 in 2020. The explanatory power of the ECS in the study period showed the process of change by decreasing and then increasing, and reaching its highest value in 2020, when the explanatory power was 0.365. It proves that with the increase in the UL and the change in the ECS, there is a more significant impact on the development differences in STFE and CEE in each region. The explanatory power of the FDI is lower overall and did not pass the significance test in 2011, indicating that its role in enhancing the strength of the association of the nodes in the MN is not obvious.

From the results of the selected influencing factors on the betweenness centrality, the UL and FDI have, on average, the highest explanatory power in terms of betweenness centrality, and the highest explanatory power of all the influencing factors fluctuates greatly throughout the study period. From 2011 to 2014, the influence of seven influencing factors on the betweenness centrality was insignificant; only the GSR reached 0.375 in 2011, indicating that the GSR has a more significant impact on the role of provinces in spreading and diffusing resources through intermediaries. By 2017, the explanatory power of each influence factor has risen significantly, and the size of the influence is basically a smooth transition to 2020. It is worth noting that the explanatory power of the ISU and ECS both reached their highest values in 2017, and then decreased to a low point. This decline may be attributed to accelerated digital transformation, which has shifted the industrial structure of key intermediary regions from secondary to tertiary sectors, and concurrently driven the ECS toward lower energy intensity and greater clean energy adoption, thereby reducing their influence on network betweenness centrality.

From the results of the selected influencing factors on closeness centrality, overall, the EDL, GSR, TPR, and ISU are important factors affecting closeness centrality. Specifically, the EDL has an explanatory power size of more than 0.4 from 2011 to 2014, and the explanatory power fluctuation decreases to 0.312 from 2017 to 2020. The GSR and ISU explanatory power both reach their highest values in 2011, and then fluctuate downwards until 2020. In addition, the explanatory power of the TPR shows a fluctuating upward trend from 2011 to 2020, indicating that the improvement of the level of Sci-Tech helps the regions to better absorb technological resources, showing higher innovation capacity and competitiveness, and thus improving the STFE, consequently moving closer to the center of the network. Meanwhile, both economic development levels and government support for Sci-Tech innovation significantly enhance regional centrality within the network.

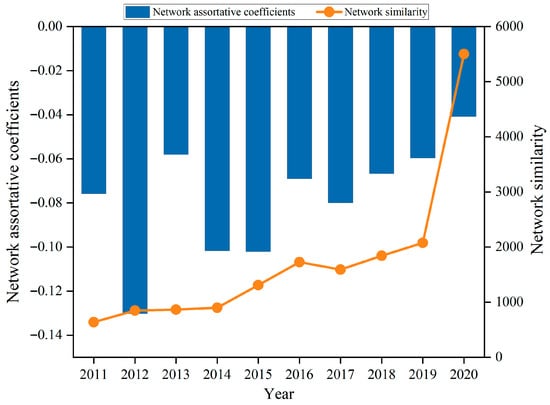

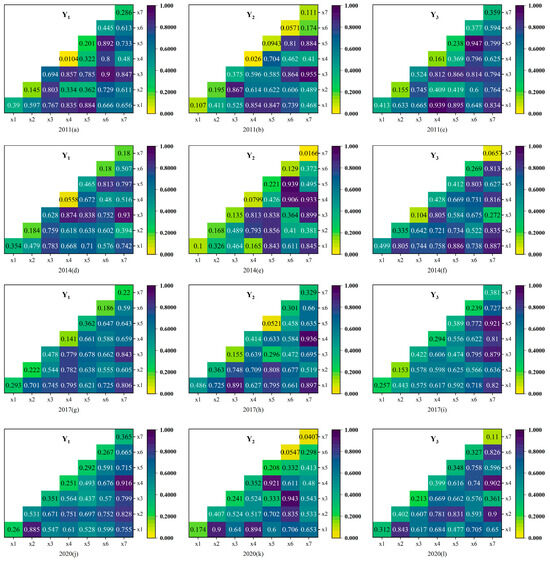

5.3. Interaction Detection Results

Figure 11 demonstrates the role of the interaction of the seven detection factors on the network weighted degree value, betweenness centrality, and closeness centrality for the four periods of 2011, 2014, 2017, and 2020, respectively. The interaction between the influencing factors mainly shows two-factor enhancement and non-linear enhancement, indicating that the selected influencing factors in this article interact to influence the network structural features in a stronger-role mechanism.

Figure 11.

Interaction results of impact factors from 2011 to 2020.

From the results of the interaction effects on the weighted degree values, the strongest combinations of interactions in 2011, selected for coefficients with q-values greater than 0.85, were X6X3, X6X5, X5X1, and X4X3, and their interaction values are 0.9, 0.892, 0.884, and 0.857, respectively, indicating that their interaction effects are more significant on the network weighted degree value compared to individual indicators. When selecting the coefficients with q-values greater than 0.8, in 2014, the combinations with the strongest interaction effects were X7X3, X4X3, X5X3, and X6X5, with interaction values of 0.93, 0.874, 0.838, and 0.813, respectively. The X6X5 and X4X3 combinations are still the strongest combinations, and remain unchanged. And in 2011–2014, the GSR and other influencing factors that form the interaction term are more significant than the more significant effect of the single factor, for the strongest combinations of the frequency that appear, indicating that strengthening the role of the GSR with other factors is more conducive to increasing the value of the weighted degree, helping to improve the strength of the association between each region and the rest of the region. In 2017, the combinations with the strongest interactions were X7X3 and X7X1, with values of 0.843 and 0.806, respectively. In 2020, the strongest interaction combinations are X7X4, X2X1, and X7X2, with values of 0.916, 0.885, and 0.828, respectively. It is evident that following the initial emergence of the ECS in the strongest combination of interactions in 2014, it is one of the strongest combinations of single factors for both 2017 and 2020, indicating that the ECS is gradually significant in influencing the effect of the weighted degree value and has become a core influence factor.

From the results of the interaction effects on betweenness centrality, screening the coefficients with q-values greater than 0.85, the strongest combinations of interactions in 2011 were X7X3, X7X5, X3X2, X6X3, and X4X1, with interaction values of 0.955, 0.884, 0.867, 0.864, and 0.854, respectively. In 2014, the strongest combinations of interaction were X6X5, X7X4, X6X4, X7X3, and X5X2, with interaction values of 0.939, 0.933, 0.906, 0.899, and 0.856, respectively. In 2017, the strongest combinations of interaction were X7X4, X7X1, and X3X1, whose interaction values are 0.936, 0.897, and 0.891, respectively. In 2020, the strongest interaction combinations were X6X3, X5X4, X2X1, and X4X1, with interaction values of 0.943, 0.921, 0.9, and 0.894, respectively. From 2011 to 2020, the most frequently occurring single-factor combinations of the strongest interactions are the ECS and GSR, indicating that the interaction of the GSR and ECS with other factors more significantly affects regional betweenness centrality.

From the results of the interaction effect on closeness centrality, screening for coefficients with q-values greater than 0.85, the strongest combinations of interactions in 2011 were X6X5, X4X1, X5X1, and X5X3, with interaction values of 0.947, 0.939, 0.895, and 0.866, respectively. In 2014, the strongest interaction combinations were X7X1 and X5X1, whose interaction values were 0.887 and 0.886, respectively. In 2017, the strongest combinations of interaction were X7X5 and X7X3, whose interaction values are 0.921 and 0.879, respectively. In 2020, the strongest combinations of interaction were X7X2 and X7X4, and their interaction values are 0.902 and 0.9, respectively. It can be seen that the interactions between the ECS, UL, GSR, FDI, and TPR are more significant than the individual indicators.

6. Discussion

From the evolutionary perspective, the network structure exhibits a clear trajectory from a “core-periphery” model to a “multi-polar radiation” pattern. The early single-core drive mode, which was highly dependent on policy and capital highlands such as the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region and the Yangtze River Delta, has gradually developed into a multi-center network pattern incorporating the middle reaches of the Yangtze River (Hubei–Hunan–Jiangxi), the Pearl River Delta, and the northwest (Gansu–Qinghai). This transformation aligns with the implementation of China’s regional coordinated development strategies, particularly the in-depth advancement of the “The Rise of Central China” and “Large-scale Development of Western China”, and corroborates findings from other studies [66,67,68,69,70,71]. The strengthening of the “intermediary” function of hub nodes in the central and western regions, such as Hubei and Chongqing, confirms that infrastructure connectivity and the integration of factor markets have effectively promoted the spatial reorganization of resource and emission linkages [72,73].

From the specific interpretation of disassortative connections in the context of STFE and CEE, in our study, we observed a persistent negative assortativity coefficient between the STFE and CEE networks. This implies that in cross-layer connections, provinces with high STFE (typically possessing advanced scientific and financial resources) tend to connect with provinces exhibiting low CEE, and vice versa. This pattern is not random; rather, it is a structural feature formed under the interplay of China’s regional development patterns and policy interactions. The first is the complementary nature of resources and the guiding role of policies. High-STFE provinces (such as the eastern coastal regions) possess distinct advantages in sci-tech and financial resources. Through channels like technology diffusion, green credit, and carbon finance market mechanisms, they provide technical and financial support to Low-CEE provinces (such as resource-based or highly industrialized provinces in the central and western regions with lower carbon efficiency). This “High-Low” connection pattern essentially reflects a cross-regional collaborative emission reduction mechanism; it is not merely “pollution transfer”, but rather a targeted driving effect where resource-rich regions empower areas with significant carbon emission reduction potential [74,75]. The second factor is the heterogeneity of regional development stages. Chinese provinces exhibit significant disparities in technological innovation capacity, industrial structure, and energy structure [76,77]. High-STFE provinces are mostly in the post-industrial stage, characterized by a high proportion of services and high-tech industries, leading to relatively high carbon efficiency. Conversely, Low-CEE provinces are often in the mid-industrialization stage, where economic growth remains heavily dependent on energy consumption. The disassortative connection between them effectively characterizes a coupling pathway where efficiency is improved through resource flows between provinces at different development stages. The third is the differentiation of network structure and function. Core nodes in the STFE network (e.g., Beijing, Shanghai, Guangdong) act as hubs in the integration and allocation of sci-tech finance resources. Their connection targets often include provinces with urgent demands for carbon reduction but insufficient internal capacity. This structure facilitates an “assistance-promotion” gradient development pattern, promoting the improvement of national overall carbon efficiency. It also explains why the network as a whole exhibits disassortativity; core nodes establish key links primarily with peripheral nodes to maximize the functional synergy of the entire network.

From the perspective of network flows, this disassortativity implies the following characteristics regarding the movement of resources and emissions. The first is the flow direction of technological and financial resources. The flow is primarily from high-STFE provinces to low-CEE provinces. This manifests as green technology transfer, financing for low-carbon projects, and carbon market quota trading, which assist the recipient provinces in upgrading their industrial structures and optimizing their energy structures. The second is the mitigation pathway for carbon emissions pressure. Low-CEE provinces, by acquiring external sci-tech and financial support, can reduce carbon emission intensity without compromising economic growth. Meanwhile, High-STFE provinces enhance their radiative effect on national emission reduction by exporting technology and management expertise, rather than relying solely on local reductions. The third is cross-regional environmental governance collaboration. This connection pattern aligns with the Chinese regional environmental governance philosophy of “common but differentiated responsibilities”. That is, developed regions, while reducing their own emissions, assist underdeveloped regions in enhancing their carbon emission reduction capacities, thereby promoting the overall carbon neutrality process.

By simulating multi-strategy attack scenarios, this study empirically verifies that the Multi-Layer Network formed by the coupling of STFE and CEE possesses stronger robustness than single-layer networks. This finding offers important insights for understanding system resilience and risk prevention in China’s regional coordinated development. Theoretically, the robustness advantage of the Multi-Layer Network confirms the view in complex system theory that “modularity” and “functional complementarity” enhance system stability [78]. In single-layer networks, attacks based on betweenness centrality lead to a sharp decline in global efficiency, reflecting the risk of “key node dependency” in China’s regional development, where a few hub provinces (such as eastern coastal economic and tech centers) shoulder excessive functions in resource transit and emission linkage. The multi-layer coupled network, through mutual backup and path redundancy between functional layers, effectively reduce the criticality of single nodes and mitigates the “bottleneck effect” where local failures trigger global paralysis. Combined with China’s reality, this conclusion has clear policy implications. Currently, China’s Sci-Tech finance resources and carbon emission activities exhibit high spatial agglomeration and imbalance, causing regions with high betweenness centrality to face both opportunities and systemic risks in the collaborative network. The study suggests that while continuing to reinforce the connectivity of key hubs, the regional coordinated development strategy should focus more on cultivating multi-level, multi-path collaborative sub-networks. For instance, the intermediary functions of central and western nodal cities in green technology diffusion and carbon markets should be enhanced to avoid excessive concentration of resource flows in a single corridor. Simultaneously, risk monitoring and emergency recovery mechanisms should be established for high-betweenness centrality regions to prevent network interruptions caused by major public events, economic fluctuations, or energy shocks.

The evolution of the Multi-Layer Network structure of STFE and CEE in China is driven by the complex non-linear interaction of multiple factors, with significant spatiotemporal heterogeneity in influence mechanisms. This conclusion not only verifies that regional coordinated development is a dynamic complex system process influenced by multi-factor coupling but also provides a new empirical perspective for understanding the synergistic path of green innovation and low-carbon transition in the Chinese context. The results deepen the understanding of the “Efficiency-Structure-Institution” interaction framework. In the early stages, government support and economic development levels showed strong explanatory power, confirming the foundational role of local government strength and resource endowments in the initial formation of regional collaborative networks [75]. However, over time, their influence has relatively decreased, while the effects of urbanization, technological progress, and energy consumption structure have continued to strengthen, even producing non-linear amplification effects through interactions. This indicates that as the collaborative network evolves from formation to deepening, the driving logic may shift from “policy and capital-driven” to a “technology-structure-ecology” composite drive. This finding resonates with innovation system theory regarding factor coupling and paradigm shifts; namely, green transition is not just technological substitution but a restructuring process of the socio-economic-technical system. Notably, energy consumption structure (X7) became a core interacting factor affecting network centrality and linkage strength in the middle and later stages. This empirically supports the proposition that “energy constraint is a key node in green innovation and financial resource allocation.” The transformation of China’s coal-dominated energy structure relates directly to carbon reduction performance and profoundly shapes the spatial flow and synergistic efficiency of Sci-Tech finance resources through cost signals, technology lock-in effects, and financial risk channels. Its strong interaction effects with urbanization level (X2) and foreign direct investment level (X4) suggest that the synergy of “Energy-Space-Opening” policies could generate systemic dividends.

Regarding policy implications, this study highlights the necessity of governance that is both differentiated and synergistic. On one hand, regional differences in the mechanisms of node influence factors suggest that policies should avoid a “one-size-fits-all” approach. For instance, eastern innovation hubs should reinforce the virtuous cycle of technological progress rate (X5) and industrial structure upgrading (X6) to enhance their radiative and control capabilities. In contrast, energy-rich and rapidly urbanizing central and western regions should focus on the fusion of energy consumption structure (X7) and high-quality urbanization, enhancing their network connectivity and intermediary functions through green infrastructure and financial tool innovation. On the other hand, the non-linear enhancement effects among factors indicate that isolated policies may have limited impact. Cross-departmental synergistic design is required, with particular attention to releasing technology spillovers and network enhancement effects during energy transition and foreign investment introduction through institutional innovation.