Abstract

Systemic cognition combines the humanities and social sciences with systems science to support a unified field, Human Systems Integration (HSI). It draws on complementary, sometimes conflicting, fields of research, including phenomenology, positivism, logic, teleological approaches, humanism, computer science, and engineering. It is time to gain a deeper understanding of our approach to HSI in complex socio-technical systems. Over the past fifty years, we have transformed our lives in unprecedented ways through technology, both in terms of useful and usable hardware and software resources. We have developed means of transport that enable geographical connectivity anywhere and at any time, which is now a standard feature. We have developed information systems that will allow people to communicate with each other in seconds, anywhere on the planet, and at any time. Systemic cognition aims to provide ontological support for discussing this sociotechnical evolution and to develop HSI not only based on a Human-Centered Design (HCD) approach, but also by focusing on society, which is becoming increasingly immersed in a world equipped with artificial resources (particularly with the growing incorporation of artificial intelligence), which separates us from nature. This article proposes an epistemological approach that extends contemporary theories of systemic and socio-cognitive modeling by integrating constructivism and research on HCD-based HSI developed over the last three decades. Aeronautical examples are used to support the concepts being developed.

1. Introduction

As you begin reading this article, you may wonder why we need to develop an approach called systemic cognition, which is proposed as a comprehensive and unified epistemic framework of sociotechnical systems (STSs) that integrates natural and artificial cognitive agents from a systemic perspective. STSs are large infrastructures that are incrementally created and maintained in context, which can be defined by various interrelated requirements based on economy, finance, technology, organizations, practices, and culture. This paper on systemic cognition is the result of a compilation and rationalization of various in-depth experiences in real-world projects using systems science [1] and engineering associated with human-centered design [2] developed in multiple industrial sectors, such as aerospace, energy production, defense, railways, and air traffic control. This epistemological contribution is therefore based on experience and is transdisciplinary. It is deeply based on constructivism. In this article, we consider constructivism to be a theory that does not rely on an a priori conceptual model for designing and developing new systems. Instead, the so-called systemic cognition framework is an ever-evolving result of experiences and social interactions, integrating new information with existing knowledge in a constructivist manner [3,4]. More specifically, the systemic cognition framework is derived from the active compilation of experiences acquired during the design and development of industrial sociotechnical systems.

From this perspective, this article differs drastically from typical scientific papers, featuring a more structured approach that progresses from a precise problem statement to a clear presentation of the proposed framework’s components, and ultimately to a demonstration of its utility through a detailed and methodical application. It is a story of a mix of experience-based conceptual models and knowledge representations that have emerged from real-world development using classical approaches, in search of an integrating framework. It is not a position paper that was written with supposedly good ideas that provide a preliminary research agenda for further research and development. It is a constructivist endeavor.

The central ingredient of systemic cognition is the concept of system. Therefore, what do we mean by system? A “system” is considered here as a conceptual model or representation of an artificial or a natural entity. A system is a construct of our mind, i.e., people generate systemic knowledge and meanings from their experiences, as considered by Jean Piaget, who posited that knowledge is the act of building knowledge [5,6,7].

Using systems engineering terminology, let us consider that a system is a system of systems [8]. For example, a human being can be viewed as a system composed of organs, which are considered systems also (e.g., a physician commonly talks about the cardiovascular system); an aircraft can be viewed as a system consisting of a flight management system, a landing gear system, and many other embedded systems (i.e., these systems are part of a larger system, namely an aircraft). In addition, a “system” is a continuously evolving knowledge representation or model of a natural or artificial entity, specifically a human or a machine [9]. A system has a life cycle and may become obsolete over time. For example, a civilization can be considered a system with its life cycle, from birth to development, and finally, collapse. Life “shows certain attributes, including responsiveness, growth, metabolism, energy transformation, and reproduction” [10]. Therefore, since a system has a life cycle, it is life-critical. It can be influenced by internal or external causes (i.e., events can occur that contribute to modifying or damaging the system, sometimes to the point of destroying it). Life criticality concerns technology, organizations, and people. When we focus on people, we usually discuss safety.

Cognition can be “the states and processes involved in knowing, which in their completeness include perception and judgment” [10]. Cognition, the experience of knowing, is usually distinguished from an understanding of feeling or willing. The proposed systemic approach will associate them.

Systems engineering has significant connections to multi-agent artificial intelligence [11] and (socio-)cognitive science [12,13], but a robust ontology for the resulting mix is lacking. We then need to develop deeper investigations that require appropriate concepts, terminologies, ontologies, cognitive models, and representations that homogenize systemic and agentic approaches to human–machine teaming from a cognitive perspective. Systemic cognition considers systems as resources for other systems, whether they are natural or artificial, human or machine, physical or cognitive. Systems as resources are necessarily based on trust, collaboration, and operational performance.

Ultimately, more than anything else, systemic cognition is being developed as an integrated framework for human systems integration (HSI) based on systems science knowledge and human-centered design (HCD) experience by defining appropriate life-critical concepts and attributes within a homogeneous framework and ontology that encompasses technology, organizations, and people [9].

2. From Reductionism to Sociotechnical Systems

Systemic cognition considers a sociotechnical system (STS) as a cognitive system of systems (e.g., mixing human and artificial intelligence). Nowadays, cars equipped with digital technologies, for example, can perceive their environment, learn from their experiences, anticipate the outcome of events, act to achieve goals, and adapt to changing circumstances [14]. This article goes beyond the current view of “isolated” cognitive systems by expanding and associating the cognition concept from intrinsic single-agent models (e.g., embodied cognition) to extrinsic multi-agent models (e.g., distributed cognition). Consequently, systemic cognition attempts to homogenize the description of natural and artificial entities within an STS, represented as systems, which are themselves systems of systems [9,15].

Systemic cognition extends beyond and breaks with the Cartesian body–mind duality paradigm [16,17,18]. Several authors have already emphasized theories and models to depart from this duality and underlying reductionism, including autopoiesis [19], embodied cognition [20], distributed cognition [21], cognition in vision science [14], and constructivism [5,6,7,17]. Jean-Louis Le Moigne criticized the Cartesian positivist dogma, commonly referred to as rationality, and its hegemonic status [3]. Like Ilya Prigogine and Edgar Morin, he argued for a “new alliance” between analytical and constructivist epistemology [4]. Systemic cognition is also strongly based on the social development of intelligence [22].

STSs are complex because they are highly interconnected, internally and externally. Most importantly, they encompass individuals who are themselves complex, as well as numerous interconnections between human and artificial entities. They also generate emergent phenomena, such as workload, social relationships, personality, stress, vigilance, situation awareness (SA) [23], human errors, distraction, intersubjectivity, trust, collaboration, fatigue, etc. Intersubjectivity refers to the phenomenon of shared understanding among agents in a network of agents. Throughout our lives, we strive to determine the limits within which an individual or, sometimes, the overall system can operate and survive. Again, we talk about life-critical systems.

We cannot purposefully understand a system by only cumulating the comprehension of each component. We need to observe the whole thing in action. For example, we must realize how interconnections between components define the system’s activity, robustness, and stability/instability. However, we will not understand why a system behaves as it does until we have a clear awareness of its purpose, in terms of cause and effect. The behavior of a system is more than the sum of its components’ behaviors (i.e., its activity produces emergent phenomena embedded within the system when it creates an activity in a specific context). For example, whenever we think and act, our brain, as a complex system of interconnected neurons, produces consciousness as an emergent phenomenon, as connectionist approaches attempt to replicate it [24].

In addition to the property of emergence, a complex system can adapt by managing internal interactions (i.e., interactions between sub-systems) and external interactions (i.e., interactions with other systems). It is a dynamic entity that behaves according to its purpose or function to preserve its identity. A dead or inactive entity will not be considered a life-critical system in a cognitive science sense (e.g., grains of sand). In contrast, a life-critical system may have properties such as homeostasis and autopoiesis. The phenomenon of homeostasis was first coined by Walter Cannon [25] and later mathematically formalized by Norbert Wiener as cybernetics [26], building upon the discovery of Claude Bernard, who referred to it as “internal environment preservation” [27]. As introduced by Maturana and Varela [19], autopoiesis is a model of the reproduction capability of a life-critical system. The systemic cognition approach adopts these phenomena and is deeply rooted in Vygotsky’s “Mind in Society” work in psychology and Minsky’s “Society of Mind” work in artificial intelligence. The former work can be summarized by the claim that “humans are the only animals who use tools to alter their inner world as well as the world around them” [28]. The latter work claims that “each mental agent by itself can only do a simple thing that needs no mind or thought at all… yet when we join these agents in societies, in certain very special ways, this leads to true intelligence” [12]. Departing from Meadows’ contribution to “Thinking in Systems” [29] and based on a constructivist epistemological approach [3], systemic cognition is grounded in the principle that the ability to understand complexity is developed gradually through progressive familiarity. It is the contextual purpose that determines the relevance of elicited knowledge. Complexity is at stake here.

How can we define complexity? We usually describe a situation or a system as complex when we do not understand it! Beyond this popular statement, we may understand a complex system in one context but not in another. Complexity awareness is strongly dependent on the context and the cognitive modeling process being used. Modeling is a matter of decision-making (i.e., making compromises). The more the modeling process is experienced in various contexts, the more familiar the corresponding complex system becomes; therefore, it is easier to comprehend and operate. Complexity is also a matter of uncertainty, unforeseen or unexpected situations, diversity, quantity, and heterogeneity of its components, as well as infinite overlaps between components and viewpoints, bifurcations, and potential unpleasant effects. Our cognitive limitations, divergent interests, antagonisms, complacency, and diverse or complementary backgrounds often influence our awareness of complexity.

3. Systemic Cognition in the Engineering Design Context

3.1. Encapsulating Logical and Teleological Formalisms

In the engineering design context, systemic cognition requires appropriate models and knowledge representations that encapsulate logical and teleological formalisms. Leplat and Hoc introduced the distinction between task and activity [30], which contributes to proposing a logical definition of a system, i.e., a system transforms a task (what is prescribed to be done) into an activity (what is effectively done). In engineering, a “logical definition” typically underlies linear causality, i.e., an activity is the consequence of executing a task using a deterministic logic. In systemic cognition, activity is not predetermined but observed in the real world or a simulated world that is sufficiently close to the real world.

A system typically uses something to produce something else. For example, people need to eat and exercise to maintain their health and well-being, and a car cannot bring you from A to B without fuel. Similarly, a pilot responsible for flying passengers from airport A to airport B (i.e., the purpose or role) has a high-level prescribed task that can be decomposed into several subtasks. Pilots must calculate the amount of fuel required according to the planned route, considering the relevant context (e.g., weather forecast, traffic, etc.). They have the necessary resources (i.e., systems) to execute the task (e.g., flying skills and knowledge, as well as flight attendants caring for passengers, etc.).

Understanding the system’s functions and structures is a teleological issue [31]. We proposed an HSI representation [9] based on the principles of teleological theory (i.e., goal-oriented functions that have roles or purposes within an organization). In philosophy, teleology (from Greek telos, “end,” and logos, “reason”) explains an entity by reference to some purpose, end, goal, or function [32]. For example, the purpose or function of an agent, such as a letter carrier, in an agency, such as the post office, is to deliver letters. This is how a letter carrier is defined teleologically as an agent or a system in an agency or a system of systems.

This teleological definition of a system, which associates role, context, and resources, enables the declarative description of system configurations. The term “declarative” must be considered in the psychological sense of declarative memory, which refers to memories for facts and events that can be consciously recalled and “declared” [33]. In computer science, a distinction is made between imperative and declarative programming. The former specifies the control flow of computation (i.e., a sequence of instructions to be executed). Examples of imperative languages are Fortran, C, Java, and PHP. The latter specifies the computation logic (i.e., what program must be executed). Examples of declarative languages are LISP and Prolog [34,35]. By metaphor, the actors’ characters in a theater play are declared (e.g., one is the mother of another who is empathetic and proactive). The scripts the actors perform are the constituents of an imperative program.

3.2. Logical and Teleological Definition of a Sociotechnical System

The various systems of a system of systems may not have the same purposes. They may even be conflicting. In a society based on maximizing individual interests, specific natural or artificial systems may compete for the same resources, which can undermine the system’s robustness and stability, particularly when resources become scarce. The concept of resource is crucial in systemic cognition, as it can refer to a matter or state, such as water or the amount of available water, or a system or process, such as a water supply system or a purification process.

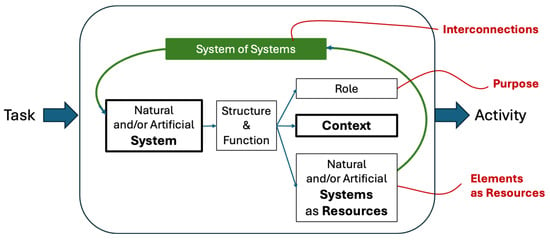

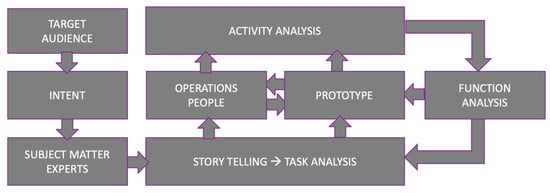

Let us now describe how the overall system works (Figure 1). Logically, a system transforms a task into an activity. Teleologically, a system is defined by its purpose or role (e.g., in the case of corporate policy, the objective will differ depending on whether the model is democratic, liberal, or authoritarian), a context of validity, and a set of available resources [9,36]. The fact that these resources are systems themselves captures the notion of a system of systems at the heart of the definition of a sociotechnical system.

Figure 1.

The logical and teleological definition of a sociotechnical system.

A system can be described by its structure and function, which can be expanded, either upstream or downstream, depending on the required degree of detail, natural and/or artificial, physical and/or cognitive (i.e., conceptual), and, more specifically, human and/or machine. Figure 1 depicts the declarative definition of an STS, which makes the system-of-systems recursive property explicit.

In Meadows’s terminology (in red in Figure 1), a system is defined by its elements that are resources (i.e., systems), its purpose, which is its role in the system of systems where it belongs, and interconnections that can be internal (i.e., a system is a system of systems) and external (i.e., a system belongs to a bigger system of systems). Once the purpose is set, regardless of whether we change its elements and interconnections, the system’s behavior will likely remain the same throughout its lifetime until this purpose becomes obsolete. This life-cycled stabilization could be called culture.

The declarative definition of a system proposed in Figure 1 has a remarkable reciprocity property (i.e., a system can be a resource for another system and may have this other system as a resource). For example, in the cockpit of an aircraft, the captain has a first officer as a resource, and vice versa in some cases (e.g., pilot flying [PF] and not-flying [PNF] or monitoring [PM] are functions that can be allocated to the captain or the first officer). As another example, astronauts are equally trained in leadership and followship (i.e., in some cases, the flight commander may ask one of the crew members to take charge of certain critical operations because of their specific skills).

4. Systemic Cognition Resources (SCRs) of a Sociotechnical System

Meadows claimed that stocks and flows are the foundation of any system. They are observable elements of the system. “Stocks represent the accumulations within a system, while flows represent the stock changes over time. Understanding the dynamics of stocks (quantities that build up or deplete) is critical for comprehending system behavior.” [29].

4.1. How Do Systemic Cognitive Resources and STSs Interact?

Systemic cognitive resources (SCR) are defined as stocks capable of providing various types of services to an STS, as defined by Meadows. A pilot flying an airplane requires multiple kinds of SCRs (e.g., workload, workload management systems, competences, skills, regulations, and mechanical instruments that support interaction between them and the airplane, among others). These SCRs can be physical, cognitive, or social in nature. They can also be systems themselves (i.e., a system may require the support of another system to execute a demanding task).

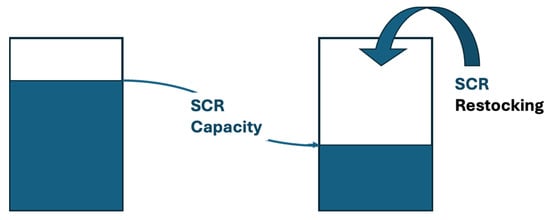

For example, people accumulate skills, knowledge, self-confidence, love, anger, stress, and other things that shape their personality and behavior (i.e., emergent phenomena). We can imagine a stock as a metaphor for a reservoir of water that can be used at any time to provide either water to another system or to receive water from another system. It is the same for a medical cabinet that contains medicines available in the event of illness. Whenever a water reservoir is used, its level decreases and must be restocked to maintain a reasonably safe level (Figure 2). The same is true for the medical cabinet: anytime a medicine product is taken from the cabinet, it must be replaced by another of the same type, and so on. Maintaining the right level of stock is a continuous process. Note that stocks can be considered as resources (e.g., a water reservoir is a resource that provides water when needed).

Figure 2.

SCR capacity use and restocking.

We will use the term SCR instead of stock in the rest of this article. For example, an airline, considered as an STS, has several processes, considered as SCRs, such as flight booking, safety assurance, marketing, and technical. Each SCR has the capacity to reach the goal it is assigned. SCRs are situated and can be distributed. Available SCRs define an STS’s capability, capacity, and availability to execute a task and transform it into an activity.

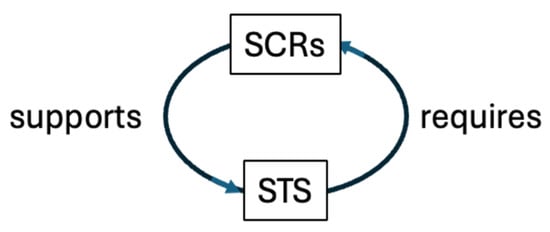

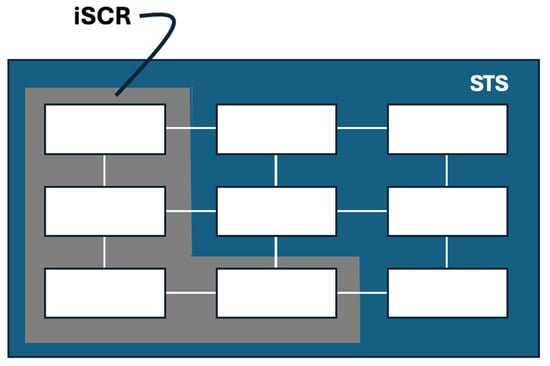

An SCR, such as workload, can be a state (e.g., the amount of workload that is reasonably acceptable for a human being to perform a task correctly) or an STS (e.g., a workload management system, which may be a system responsible for managing the utilization and regeneration of workload). More generally, any STS requires an appropriate set of SCRs that contribute to its proper functioning and survival (Figure 3). For example, an airplane, with its crew and passengers, requires an appropriate set of SCRs, including flight controls, seats, fuel, food, cabin crew, and various onboard systems, to ensure a safe and comfortable flight.

Figure 3.

A sociotechnical system (STS) requires systemic cognition resources (SCRs) to support it.

More specifically, if we consider work capacity as a stock, and therefore an SCR of an STS that can be a simple agent (human or machine) or a multi-agent system, a prescribed task requires the estimation of the related taskload, which must be compatible with the SCR’s work capacity. The execution of this task resulted in an activity (Figure 1) that ultimately determines the effective workload.

A taskload metric (TL) can be defined as the ratio between the required time (tR) and the available time (tA), expressed as TL = tR/tA, to execute a given task. TL could be considered a good indicator of workload capacity. If your TL is less than one, your availability to perform the corresponding task is good. If your TL is more than one, your availability to execute the corresponding task can be poor. In practice, subject matter experts adapt their workload between hypo-vigilance and stress thresholds. When they are skilled, they even need enough workload to be effective (e.g., adrenaline keeps expert pilots focused!). This is why taskload analysis, a prescriptive technique, supports other workload assessment techniques [37].

SCRs can be limiting (i.e., handicapping) or supporting (i.e., helpful). For example, workload can handicap work when it is too high (i.e., over the stress threshold) or too low (i.e., under the hypo-vigilance threshold). Workload can also help keep people in the work loop between stress and hypo-vigilance thresholds.

Among the aircraft pilot’s cognitive resources are the technical crew’s cognitive resources, including the pilot, as well as other cognitive resources (e.g., onboard embedded systems, air traffic controllers, and flight attendants). Onboard embedded systems are technological resources that deal with handling qualities, navigation, collision avoidance, and fuel management. Each SCR involves human, organizational, and technological factors, which can be considered stocks of valuable and necessary resources in context (e.g., stocks of situation awareness and survivability resources; a pilot’s awareness of the remaining quantity of fuel to reach the destination, for example).

4.2. Schemas, Information Flows, and SCR Metrics

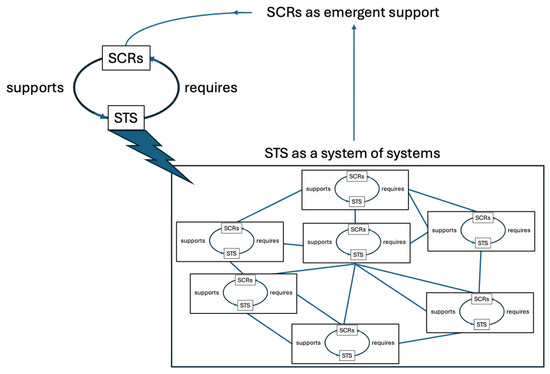

SCRs of individual systems are extended to systems of systems as emergent support (Figure 4). They are mutually inclusive, involving recursive modifications through multiple experiences and learning.

Figure 4.

SCRs of a system of systems as emergent support.

SCRs are reservoirs of dynamic and reconfigurable patterns or schemas [3,4,38,39] managed by an STS. They vary in quantity and quality as input and output information flows vary. They are dynamic, evolutionary, context-sensitive, and interactive with each other. Schemas are typically regarded as procedures. They can be more generally represented as interaction blocks or iBlocks [40]. An iBlock is defined by its context of validity, triggering conditions, tasks to be executed, goal(s), and abnormal final conditions. The iBlock representation has been successfully utilized in aeronautics for defining and validating cockpit instruments on board commercial aircraft.

Not only are SCRs dynamic, but interactions among STSs, equipped with their SCRs, are highly dynamic. At this point, let us try to reconcile Piaget’s and Vygotsky’s contradictory arguments on their respective theories of cognitive development. For Jean Piaget, the cognitive system assimilates and adapts to social interactions, whereas for Lev Vygotsky, cognition is the highest form of social behavior and, in essence, inherently social. SCRs could very well fit into both theories.

Consequently, at each level of granularity, the behavior of the STS in play results from activating schemas, which are reconfigurable systems of systems that interact to achieve their purposes. These schemas can be procedures or problem-solving systems, considered as chunks incrementally constructed from experience.

5. Systemic Cognition Methodology

Several concepts have been defined, including systems that involve structures and functions, as well as SCRs, which are necessary services to support STSs. At this point, a systemic cognition methodology must be proposed. More specifically, since an STS requires appropriate SCRs, various mechanisms must be defined, such as the identification and integration of emerging SCRs, SCR chunking, and strategies for dealing with unexpected events, redundancy, and resilience. But first, let us introduce the PRODEC method, which enables the creation and refinement of an STS.

5.1. The PRODEC Method for Incremental Emergent Function Discovery and Allocation

At this point, we will introduce the PRODEC method, which utilizes procedural knowledge (commonly referred to as scenarios) to generate declarative knowledge (widely referred to as configurations) [36,40]. The implementation and further analysis of procedural timelines for tasks and activities enable the incremental generation and consolidation of systems’ structures and functions, as presented in Figure 1. PRODEC belongs to the family of scenario-based design “techniques in which the use of a future system is concretely described at an early point in the development process” [41]. Figure 5 presents the PRODEC as an iterative, closed-loop process.

Figure 5.

PRODEC multi-looped process.

Traditionally, engineering begins by declaring technological requirements and then developing and verifying objects and machines that satisfy them. When technology is developed, it adapts to end-users by creating user interfaces and operational procedures that often compensate for design flaws generated by applying non-HCD approaches. Instead, systemic cognition supports coherent and effective scenario-based design. More specifically, PRODEC typically starts with task analysis, followed by the development of virtual prototypes that enable human-in-the-loop simulations (HITLS), allowing for the analysis of the observed activities.

Developing virtual prototypes as digital twins of sociotechnical systems requires flexible declarative systemic models based on the declarative representation depicted in Figure 1. These models are not defined forever. They evolve as they are put to work. They are dynamic and modifiable, which may become obsolete. They are developed incrementally and eventually stabilized.

A legitimate question is: How do we discover emerging features that suggest considering new structures and functions when we design a new system using PRODEC? PRODEC is a scenario-based design method that should be applied from the beginning of the design process and throughout the system’s life cycle. Based on appropriate operational scenarios, PRODEC considers function allocation as a dynamic process. This process helps avoid the development of technological black boxes, which are based solely on a priori, deliberate function allocation. Instead, allocating the proper functions to the right human and machine structures considerably simplifies the creation of user interfaces.

Emerging functions being discovered using PRODEC can be iteratively added. However, we need to be careful to check how they interact with each other. Indeed, they are likely to interact using various systemic interaction models [9], such as supervision, mediation, cooperation, or sometimes competition. The accumulation, appropriation, articulation, integration, anticipation, and action of systems (functions and structures) within the system of systems being considered must be thoroughly understood and mastered. Regulatory rules must be established to ensure the system of systems remains operational, which also means that it preserves each system it encompasses. This is the already introduced homeostatic property of living systems [25,26]. The more systems become autonomous within a system of systems, the more mandatory regulatory rules are required (e.g., a football match cannot be played without rules, as we have road rules to keep each vehicle safe). Bernard-Weil’s agonistic-antagonistic systems science (AASS) illustrated these phenomena in physiology and medicine to elucidate phenomena associated with conflict and cooperation [42]. They can be easily extended in the sociotechnical world.

For all these reasons, system-of-systems development requires attention, as we may quickly end up with a can of worms if rules supporting self-organization are not identified for stability purposes (e.g., road rules to stabilize road traffic). These rules can be event-driven (e.g., the system must adopt the best strategies and tactics to survive reactively) or goal-driven (i.e., coordination rules must be followed to maintain the overall system’s safety, efficiency, and comfort). In practice, it is a mix of the two (e.g., coordination rules are established iteratively, considering event-driven experience and the viability of goal-driven purposes). This is the primary objective of HCD, where STSs must be effectively designed with the operational context in mind [2].

5.2. Identification and Integration of Emerging SCRs

Marvin Minsky proposed a model of human intelligence in his philosophical essay, The Society of Mind [12], where he postulated that intelligence results from interactions between atomic elements called agents, which can be straightforward. He also postulated that an agent can be a society of agents. This concept is very close to the “system of systems” concept in systems engineering.

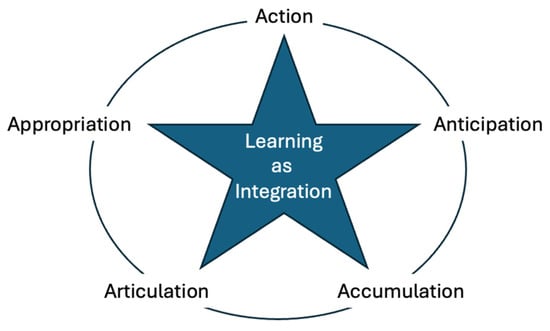

Harmonization within a system of systems results from individual learning of all its elements and from an incremental integration of organizational principles and rules used by its internal systems. In Tuomi’s organizational learning sense, these organizational regulations bring to life SCRs, which are incrementally integrated, using five main functions (Figure 6): anticipation, appropriation, articulation, accumulation, and action [43].

Figure 6.

SCR generation and integration as a learning mechanism based on Tuomi’s 5-A model.

Comparing the homeostatic system from cybernetic control theory, which focuses on regulation [27], with an autopoietic system, which focuses on reproduction [19], Tuomi proposed the 5-A model of knowledge generation, which reconciles positivism [44] and phenomenology [45], connecting behavior through observable cues and the creation and maintenance of meaning. Positivism is supported by scientific and quantitative research approaches (i.e., experimental and primarily based on data science and statistics). In contrast, phenomenology relies on qualitative and subjective approaches (i.e., primarily based on in-depth interviews).

The dynamics of SCR generation, whether individual or organizational, can generally be stable, except in chaotic situations where a bifurcation occurs (for example, in stock markets, sudden price falls, and disasters). This is a challenging systemic property, which should lead to more investigations into resources considered as shock absorbers, such as capacitors. Highly experienced individuals possess this stabilization capacity because they have accumulated and integrated sufficient knowledge and skills to respond correctly when an event occurs, even a dangerous one. This is the same for mature organizations. This phenomenon can be referred to as rational sociotechnical inertia. Consequently, the quality and quantity of life-critical properties can be assessed using life-critical indicators (e.g., safety, stability, resilience, trust).

5.3. SCR Chunking Mechanism

Meadows’s concept of stock, considered a life-critical factor and resource, is compelling from the perspective of chunking. Chunking, the process of breaking down knowledge into manageable chunks, has been presented as a general human learning mechanism [46] based on the concept of chunking, further developed by Allan Newell in his unified theories of cognition [47]. In this article, chunking is expanded to encompass the dynamics of SCRs, allowing us to discuss chunks of SCRs.

Analogously, we anticipate limitations, such as limited capacity, which is typically represented by seven plus or minus two chunks of knowledge [48], expanded to several SCR chunks to be discovered. It is essential to note that this cognitive limitation is a heuristic that should be used with caution. This 7 +/− 2 heuristic is in line with Piaget’s psychology of intelligence theory [3,4], but not with Vygotsky, who believed that human performance is never stable, because every new experience is an opportunity for new development, and therefore new capacities, which no one can predict how far they may go. This may be interpreted as the difference between using and refining procedures and learning problem-solving processes. That is the scientific debate between Jean Piaget and Lev Vygotsky. Still, from a social and systemic perspective, we must establish standards at some point and create a typical frame of reference to avoid drifting towards rigid doctrines that fail when events occur outside their context of validity.

5.4. The SPO Case

For example, the number of technical flight crewmembers in commercial cockpits for transatlantic flights decreased from five at the beginning of the 1960s to two at the start of the 1980s. The aviation industry is considering going to single-pilot operations (SPO). Regarding life-critical properties, flying with a captain and a first officer maintains sufficient usable SCRs in the event of pilot incapacitation, which is likely to render a pilot unable to perform their job. Consequently, in the SPO context, we need to demonstrate that either an artificial copilot or a ground remote operator could take care of the rest of the flight (refer to Figure 1 and Figure 4).

Reducing the number of technical crew members from three to two demonstrated that the airplane can be landed with only one pilot onboard in the event of the incapacitation of one of the crew members. We must now demonstrate that reducing the technical crew from two to one allows the aircraft to land without anyone on board if the sole pilot is unable to perform their duties. This is a singularity because with zero pilot onboard, the aircraft is no longer a classical airplane but a drone (or an uncrewed aerial vehicle). This means that SPO requires us to design and develop drones for commercial transportation and determine who will be ultimately responsible for flying them, implying that new emerging SCRs must be elicited and properly defined. This is a systemic problem that requires identifying the right systems/agents that need to take care of the overall safety, performance, and comfort of the flight. In the SPO case, will the professional person onboard have the function of a pilot, an engineer, a flight attendant, or all three? What will be the potential assistants? It is therefore crucial to investigate corresponding SCRs regarding safety, efficiency, and comfort, and allocate them appropriately.

In addition to schemas and information flows, SCR metrics must be defined to observe, understand, and evaluate STS behavior, and more specifically, comprehend how the STS is or should be regulated and stabilized. For example, workload is an SCR metric that needs to be controlled. Workload as a state should be neither too high to avoid stress, nor too low to prevent hypo-vigilance and maintain a reasonable level of proactivity. Workload regulatory processes, understood as SCRs, could be intrinsic or extrinsic. For example, inherent workload regulation can be achieved through learning and training to form expert cognitive patterns that enhance information processing, motivation, and time management under pressure. Extrinsic workload regulation can be achieved through collaboration with partners who can handle specific tasks. Both types of regulation are life-critical within the framework of systemic cognition. All information flows go from one system to another, whether elementary (i.e., a simple system as presented in Figure 1) or complex (i.e., a system of systems as presented in Figure 3).

5.5. Intrinsic and Extrinsic SCRs

In the same way, a distinction between intrinsic and extrinsic workload was made; intrinsic and extrinsic SCRs of an STS can be distinguished. Indeed, it is crucial to identify the association of STSs within or outside an STS that determines a relevant SCR for this STS. Keep in mind that an STS may represent a human, a machine, or a group of humans and machines interacting with each other, at various levels of granularity.

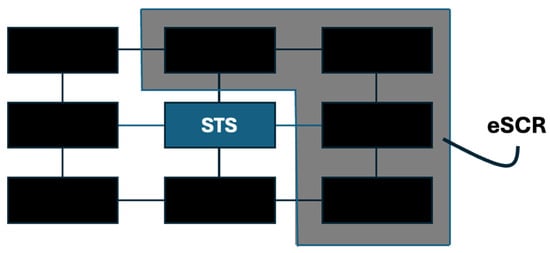

Figure 7 presents a relevant intrinsic SCR (iSCR) of an STS considered as a system of systems; in this case, the SCR is an association of internal STSs, which are parts of the STS. Figure 8 presents a relevant extrinsic SCR (eSCR) of the association of STSs external to the STS being considered.

Figure 7.

An intrinsic SCR (iSCR) of an STS is considered a system of systems (gray zone).

Figure 8.

An extrinsic SCR (iSCR) of an STS, constituted as an association of external STSs (gray zone).

This distinction provides a useful conceptual tool for identifying SCRs of an STS considered as a system of systems, which is included in a larger system of systems. iSCR can be seen as competencies, and eSCR as support of an STS. These competencies and support resources are incrementally structured by assimilation and accommodation, in Piaget’s sense [5,6,7]. Indeed, we learn by acquiring and adapting cognitive functions in the form of iSCRs (e.g., acquiring skills for debating in society), as well as socio-cognitive support from outside in the form of eSCRs (e.g., recognizing that we can rely on certain people or organizational structures). To illustrate human-machine coupling, a pacemaker is an instance of an iSCR, which is a system that is part of the human body (i.e., considered as a system of systems), or an eSCR, if we consider the pacemaker as an external support that activates the heart. The first option is probably correct because the pacemaker iSCR also requires adaptation with other internal body systems to prevent rejection. At this point, one may contest the use of STS terminology to denote the human heart or the pacemaker, but they are both part of a society of agents (systems) trying to work together. Therefore, STS terminology can be kept as a generic concept for organizational setups of human and machine systems.

5.6. Dealing with the Unexpected, Redundancy, and Resilience

In the context of artificial intelligence, a rational STS has no emotion or affectivity between systems, etc. This view is acceptable when everything can be expected. Conversely, it is a utopian view of a real human–machine system in unexpected situations. Human operators follow appropriate procedures or monitor automation in a rational world where everything is expected. In unexpected, rare, or unknown situations, human operators must solve problems in real-time, which shows the need for a constant search for emerging SCRs that can be integrated into the STS being considered.

STSs are continually evolving through a multi-regulation process. Experience feedback is incrementally processed, and new knowledge and skills are reinjected into life-critical resources, both iSCRs and eSCRs. Artificial SCRs, such as operational procedures and automation (i.e., eSCRs), have been successfully developed and used in expected situations. However, they can be very rigid in unexpected situations, where new types of iSCRs are required, which can be problem-solving skills when we need to deal with unforeseen situations, and creativity. Note that both problem-solving and creativity can be the functions of an eSCR. These cases require a high degree of flexibility, in-depth knowledge, and skills, as well as the coordination of multiple agents and systems. Consequently, other types of technological, organizational, and human SCRs must be designed and made available for unforeseen or rare situations. We have already provided some ideas [9].

SCRs constitute situational redundancy, which our market-based forces us to optimize. This optimization is currently focused on financial and short-term considerations. Indeed, the market economy must consider SCRs to prevent major disasters, rather than optimizing financial resources alone. For example, the Boeing 737 Max disasters are typical in this regard. Instead of choosing a less costly solution to reduce fuel consumption, they should have opted for reliable solutions that would not have ultimately grounded all aircraft of this type for months (e.g., the choice of a higher landing gear to allow the insertion of larger-diameter engines under the wings, to avoid potential instability problems caused by the solution of inserting the new engines in front of the wings).

Another solution could have been to make the aircraft’s angle-of-attack measurement system more redundant to prevent excessive movement of the horizontal stabilizer in response to a single failure, along with appropriate training for the airline’s crew. More generally, safety nets are reasonable solutions, but they require pilots to be aware of the potential actions they can take when contributing to them.

Regarding flight stability, a matter of physics, corresponding SCRs were not considered seriously. It should not be forgotten that the aircraft is a complex and life-critical artefact with which pilots need to familiarize themselves, particularly with the limits of the flight envelope. It is a life-critical system coming from the analytic thinking of engineers who understood that flying is a matter of thrust and lift, which, when combined correctly, enable humans to fly. Modeling the corresponding STS as a system of systems and considering the relevant SCRs would have explicitly highlighted the dilemma between a short-term, cost-driven solution and a medium-term, HSI-driven solution, thereby avoiding a financial disaster.

Aircraft have been successfully modeled using specific mathematical equations from aerodynamics, mechanics, electronics, and computer science algorithms. However, aircraft have become increasingly complex over the years because they are systems of systems, interconnected within a complex network of systems. A significant question has emerged: how much time is required to become familiar with this new complexity? To answer this question, we must first distinguish between the complexity of engineering and operations. They are linked, of course. The former is an engineering issue that involves developing technology to support flight, while the latter requires piloting skills that extend beyond hardware and software engineering. The former is usually a question of technological robustness, availability, and safety. The latter concerns human skills, compliance with regulatory rules, knowledge of the aviation environment, and airmanship. What makes all these requirements complex is that they are highly interrelated. In addition to the deliberative knowledge about an aircraft, emergent flying phenomena must be known and embodied (i.e., learning about aircraft pieces and their assembly differs from feeling the air before detecting a stall in flight, for example).

Flight safety is an SCR that pilots must fully integrate into their minds and bodies. In particular, the issue of stability will always be a crucial concern in aviation. It is a technological SCR that can be partly supported by the human situation awareness SCR, which is enhanced by highly sophisticated software that helps reduce the pilot’s cognitive load.

More generally, technological, organizational, and human SCRs are intimately related in context. For example, the Challenger and Columbia space shuttle accidents were driven by organizational SCRs (i.e., organizational complacency was a major SCR) [49]. This is why we need to better understand complexity issues and potential solutions that systemic cognition can propose.

6. Systemic Cognition Complexity

Today, an airplane is no longer just a maneuverable artifact resulting from our skills and intellectual reasoning, translated into a manageable mechanical object; it is a life-critical system with an artificial brain that collaborates with pilots as part of a human–machine team. As a result, we have developed drones that require new kinds of management and will be electronically interconnected with other aircraft for self-separation challenges, for example. Complexity arises from the number of entities and the interconnections between them when they are put to work. As this number increases, so does complexity.

6.1. Simplifying the Complicated and Familiarizing with the Complex

At this point, we need to better understand the distinction between complicated and complex. A complicated artifact can be simplified if the general laws of physics are satisfied (i.e., useful SCRs of complex systems are usually based on physics laws, specifically mechanics in engineering). A mechanical watch, for example, consists of a winding mechanism (i.e., the crown winds the movement and sets the hands), a barrel that stores the energy of the mainspring, a gear train that transmits the energy, a pallet fork and escape wheel that distribute the energy, a balance wheel and balance spring that regulate the energy, and hands that indicate the time and any other functions. A mechanical watch can be dismantled and rebuilt. This is not very easy, but it is doable!

A complex system cannot be simplified by taking it apart and rebuilding it, except for some parts that are separable (e.g., a human being is a complex system that cannot be simplified!). In other words, a complex system is more than the sum of its parts. It involves other properties, such as the emergence of phenomena, which are not included in any of the parts. It is complex by chance and necessity [50]. We can become familiar with its complexity and, consequently, find it simpler, creating increasingly easier relationships. Research scientists incrementally discover such properties and behaviors of complex systems (e.g., separability or non-separability of biological systems). Consequently, useful SCRs of complex systems can be incrementally defined by discovering these emergent properties.

6.2. Digital Society Complexity

Fifty years ago, we could clean the carburetor, change the lights, and perform other valuable maintenance tasks to keep our car running smoothly. Today, we cannot touch anything when our vehicle fails. Well, nobody even thinks about repairing their car. We must go to the shop. Somebody takes a tablet, connects it to the USB socket under the steering wheel, and tells us how much we will have to pay! The systemic cognition resource we had in our heads and hands fifty years ago, which helped us repair the car, has shifted toward a network of STSs, which are increasingly machine-driven and decreasingly human-driven. These STSs are generally helpful, but an unexpected failure can lead to huge recovery problems due to a lack of familiarity with them. An example is a flawed diagnosis (i.e., a technological SCR) that may be concealed in the complexity of the entire STS, especially when reimbursement is at stake (i.e., a financial SCR).

However, no matter how complex, an STS always has a purpose and is the product of previous purposes. Regarding the Boeing 737 Max 8 disaster, the software of its new Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS) was designed to prevent the aircraft from stalling by automatically pushing the nose of the plane down when a high angle of attack (AOA), or nose-up condition, was detected. This anti-stall life-critical resource was created and developed to address safety concerns (e.g., with too little instability margin). Even if all licensed pilots know that when an aircraft stalls, they must immediately lower the nose, some pilots think that the aircraft “does not want to take off,” and their reflex is to pull back on the stick to straighten the aircraft’s nose. A few of them did not consider that it was because the MCAS was compensating for an excessive angle of attack. Indeed, a conflict existed between the pilots and the MCAS in both accidents: the Indonesian Lion Air Flight 610 on 29 October 2018, and the Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302 on 10 March 2019. The pilots did not have sufficient situation awareness (i.e., a systemic cognitive resource regarding knowledge and expertise) to understand that the MCAS was attempting to compensate for a stall. Why could this kind of thing happen?

6.3. Short-Term Versus Longer-Term Complexity Management

It is not by considering issues of automation and technology maturity in a reductionist way that we will find the real cause of the problem. We must consider the system holistically. We must analyze the system’s complexity by considering engineering, operations, finance, and business. Why did Boeing build such a system as the MCAS? The answer to this question is extensively developed in the report produced by John Sterman and James Quinn of the MIT Sloan School [51].

Let us start a complexity analysis based on the following paragraph of this report: “Officially, Boeing, including CEO Dennis Muilenburg, repeatedly declared ‘… the 737 MAX is safe.’ However, as investigative reporter Peter Robison documented, ‘Behind the scenes, some of the largest and most respected airlines in the world were screaming that Boeing had hidden the existence of potentially deadly software inside their planes.’ Internal communications that Boeing handed over to the U.S. Department of Justice and Congressional investigators would later show that the company’s engineers and test pilots knew about the MCAS problem well before the crashes.” Again, here, the distinction between task and activity is essential. We must observe and analyze activity instead of limiting design and development decision-making to system architecture and task analysis.

Boeing’s initial intention was to change engines to reduce fuel consumption and pollution, and another crucial purpose was to compete with Airbus. The problem was that the Boeing 737 aircraft had been in service since the 1960s with engines smaller than those produced by the modern propulsion industry. When comparing the Boeing 737 to its competitor, the Airbus A320, a noticeable height difference is evident. Consequently, a straightforward engineering solution was to change the landing gear before installing new, larger-diameter engines. This was costly. This is why Boeing did not decide to change the landing gears. Instead, Boeing management asked its engineers to find an alternative solution. The solution was to install new, larger engines ahead of the wings. Since it was clear that this solution would modify the propulsion center, a software system had to be designed and developed to compensate for possible stalls, especially during takeoff. From a cognitive engineering perspective, it is never a good idea to add layer after layer of automation, which contributes to separating human operators from the real world and, consequently, significantly reduces situation awareness and tangibility.

6.4. SCR Management by Looking for Physical and Figurative Tangibility

Here is an example of conflicting systemic cognition resources (SCRs). The Boeing 737 Max 8 disasters present a life-critical design and engineering dilemma, where engineering and flight tests (SCR1) were less influential than finance and business (SCR2), likely due to a lack of SCR1’s powerful and authoritative explanation of the danger inherent in the sociotechnical solution adopted. Additionally, some pilots may struggle to understand and perceive it, particularly when they are unaware of its internal logic and external behavior. This issue may be due to a lack of communication between designers and pilots (SCR3), as well as inadequate in-depth training for pilots and their limited understanding of the aircraft design (SCR4). Furthermore, even if we understand the design logic of the MCAS, the most important thing is understanding its behavior in life-critical situations, such as takeoff.

This discussion is related to physical and figurative tangibility [9]. The MCAS raises issues of physical tangibility due to the potential for stall (i.e., the pilot cannot grasp flight physics correctly), and figurative tangibility because it is counterintuitive for some people (i.e., the pilot does not understand why the aircraft does not take off). In other words, the MCAS affordance is improper [52]. An affordance is the relationship between an object and its user in terms of the action suggested by the object to its user. Some handles suggest pushing a door, others pulling it. In the former case, the handle’s affordance is “push”; in the latter, the affordance is “pull.” People can adapt to many things, but some take longer to assimilate and accommodate. The MCAS is one of them. Using an HSI approach, human-in-the-loop simulations would have shown this lack of affordance, situation awareness, and tangibility (i.e., pilot’s operational SCRs). Consequently, different design decisions could have been made.

7. Modeling, Simulation, and Digital Twins

7.1. The Modeling and Simulation Need

At this point, we have seen that modeling SCRs could help prevent disasters. How can we become aware of the right SCRs we must know? What are they? As the MIT Sloan School report stated, some individuals were mindful of MCAS issues (i.e., the systemic cognitive factors induced by the MCAS design rationale, which are potential instability factors and possible decision-making conflicts between pilots and MCAS). Why were they not considered in time by decision-makers before it was too late, and disasters occurred? What kind of life-critical and technical structures and functions should be found to support choices of that type concretely and effectively? This article proposes a systemic approach to systemic cognition that can provide valuable answers to these questions, where a system is typically defined by its structure and function [53].

Today, digital engineering tools, such as virtual prototypes, provide valuable support for modeling and human-in-the-loop simulation at design time and during the whole life cycle of an STS. In other words, in aeronautics, these digital tools contribute to anticipating and sometimes replacing flight tests. Their development leads to the concept of digital twins (e.g., a digital replica of a real aircraft). The idea of digital twins originated during the Apollo missions, although it was not coined as such at that time, when NASA personnel involved needed virtual representations of physical objects. Remember the Apollo 13’s successful accident when ground personnel used a simulation of the capsule, oxygen tanks, and other things to put together a CO2 scrubber. This “digital twin” supported the development of a procedure that enabled the astronauts on board to build this CO2 scrubber using various devices available in the capsule. Today, digital engineering allows the development of digital twins that can be extremely tangible.

7.2. Digital Twins: Active Support for the Design Process and Its Solutions

These digital twins can then be utilized at any stage of the STS life cycle to elicit SCRs in practice, not just theoretically. It is an excellent tool for discovering emergent behavior in complex systems [54]. An STS can be tested early during the design and development phases, and relevant and practical SCRs can be validated. Designing, developing, testing, and using digital twins of a system of systems enables the identification of the real systems’ purposes and potentially conflicting purposes.

In the Boeing 737 Max 8 case, the aircraft is a system of systems, part of a larger system (e.g., the Boeing system within the commercial aircraft market). This system of systems includes pilots who are “subunits,” in Meadows’s terminology (i.e., pilots as systems in the aviation system of systems), having conflicting purposes with other subunits. In the MCAS case, before the accidents, there was a higher-level conflict between at least four STSs: the manufacturing subunit, Boeing’s senior management subunit, the design engineers’ subunit, and the test pilots’ subunit.

The main problem in developing complex STSs in various industrial sectors, such as aeronautics or the nuclear industry, is keeping a reasonable level of familiarity with the system’s complexity at all levels of the organization. The problem is that we are constantly being asked to simplify. It is time to understand that we cannot always simplify a complex system of systems; instead, we can become more familiar with it, and this may take time. In some cases, we can identify parts that can be isolated from the system of systems. This is the separability property of complex systems [55,56].

Digital twins are an excellent way to familiarize yourself with a complex STS as early as possible. As a result, we need to adapt the current short-term practices imposed by the market economy and allow for a further maturity period (i.e., technology maturity and maturity of practice and sociotechnical culture). As virtual twin technology continues to improve, simulations can be run, and activities can be observed, analyzed, and evaluated. Therefore, digital twins and human-in-the-loop simulation enable us to run testing as early as possible and avoid terrible mistakes, such as the Boeing MCAS case, and an unavoidable, painful recovery later in the life cycle. The aerospace industry has been using aircraft simulators for five decades. However, the kind of thing digital twins offer today represents a much wider field of exploration than just aircraft mechanics and handling qualities. Digital twins facilitate the integration of social, organizational, and financial perspectives, making them useful for informed decision-making, particularly regarding medium- and long-term consequences. The Boeing 737 Max 8 case is a typical example of this support that could have been used to anticipate catastrophic situations.

This analysis prompts us to explore the concept of context, as any systemic cognition resource is dynamic and evolves in space, as well as in many other dimensions. The SCR concept could be likened to life-critical capital, encompassing culture, knowledge, and mindsets. Indeed, we need to capitalize on many SCRs to handle complex STSs (e.g., consider the years of study and experience a medical doctor requires to achieve a safe level of autonomy).

8. Systemic Cognition in Context

8.1. What Do We Mean by Context?

Systemic cognition is necessarily situated (i.e., STSs and their SCRs must be relevant in their operational context). Terry Winograd [57] (pp. 401–419) claimed that something is in context “because of its operational relevance at a given time, not because of its inherent properties.” This is why subject matter experts are essential in analyzing, designing, and evaluating STSs: they understand the complexity of context.

The notion of context has long been explored. The term “context” originates from the Latin “contextus,” meaning “assembly” or “gathering.” In linguistics, it contributes to giving a text meaning (i.e., different contexts result in different meanings). Still, it is also used in the social sciences (i.e., various societies and cultures are examined in other contexts).

In philosophy, Dummett proposed the “context principle” to mark Frege’s principle [58]: “Never to ask for the meaning of a word in isolation, but only in the context of a sentence” [59] (p. xxii). In psychology and cognitive sciences, context is related to the notions of situation, field, milieu, distractor (e.g., in perception psychology), and background. Context is often viewed as a set of situational elements that include the processed object [60,61]. Brézillon considers context a matter of focus, where only a few situational elements are relevant to characterize it [62]. Contexts can be viewed as categories, such as flight phases in aviation (e.g., takeoff, initial climb, cruise, approach, and landing, among others), where context elements are persistent situation patterns within specific ranges [63,64]. Anind Dey defined the concept of context in human–computer interaction and discussed how context-aware applications function [65] (pp. 4–7). Lavelle proposed analytical, phenomenological, and pragmatic perspectives on technology in context [66].

In this article, “context” denotes what surrounds something to give it meaning. It is often understood as milieu, social environment, or even framework. More specifically, a system should be carefully thought out and, even more importantly, thoroughly tested in various situations. For example, in a house (context-1), a table refers to an object that usually has four legs and a flat surface on which to place objects. In contrast, in a book (context-2), a table can serve as a table of contents, where numbers are used to retrieve specific information.

People think with a context in mind, either guided by an intention (i.e., goal-driven) or circumstances created by the environment (i.e., event-driven). HSI requires engineering designers to explore how an STS will impact our lives before it is too late (e.g., before prejudicial, unexpected events occur). As Meadows described, “unlike random collections, systems maintain integrity and exhibit properties like adaptation and self-preservation.” This claim encourages considering homeostatic life-critical systems in context (i.e., recognizing that a system behaves according to its retroaction loops within its environment) [25,26].

8.2. Examples of Systemic Cognition in Context

Let us take the example of the American way of considering a home mailbox, which serves two purposes: receiving and sending letters. This mailbox has a “red” lever that indicates to the mail carrier if letters are to be sent when it is up (Figure 9a). In France, there is no such possibility; mailboxes are only defined as receiving letters or parcels. If you want to send a letter, you must find a public mailbox in the street (Figure 9b) or at the post office where your mail will be sent. Therefore, the definition of a mailbox as an SCR depends on the cultural context resulting from long-standing habits learned over time. Consequently, expectations differ: in the French context, nobody expects to receive letters sent from their mailbox at home, whereas in the US context, everybody does.

Figure 9.

(a) An American home mailbox and (b) a French public mailbox.

Another example is the Überlingen accident in 2002. The TCAS (Traffic Alert and Collision Avoidance System) was developed during the 1980s, following a decision of the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration based on a special type of airborne transponder capable of establishing communication between aircraft. It is an interrogative and cooperative system. It detects another aircraft near the plane on which it is installed. It provides two alerts, a “climb” for one aircraft and a “descent” for another. Pilots must then comply with these alert orders. One climbs and the other descends. After the TCAS was installed onboard, it had priority over an order from the air traffic controller (ATCO) on the ground (Context-1). The pilot must obey the TCAS. In the past, the ATCO was the boss (Context-0)! That is, the pilot had to follow the ATCO. In 2002, two aircraft collided over Überlingen, Germany. They were equipped with TCASs. One received the “Climb” order, the other the “Descent” order from the TCAS. Unfortunately, the ATCO sent a “Descent” order to the former, who obeyed without considering the contradictory TCAS order (i.e., two contradictory SCRs). Consequently, both aircraft descended and collided with each other. This is a context-driven accident, where the context was confused by one of the crew members. This can happen when relatively new systems are introduced that break with long-standing habits.

Systemic cognition could have helped to support a safer HSI approach. Indeed, introducing the TCAS profoundly modified how collision avoidance was implemented. In the past, the ATCO had the authority regarding control and accountability. The pilots were executors. The authority was on the ground and owned by humans. With the TCAS, pilots must still follow the instructions, but they report to the ATCO that they are climbing or descending. In practice, the ATCO knows what the aircraft is doing afterward. Therefore, it would have been safer to implement a link between the TCAS and a corresponding ground system to advise the ATCO about the conflict (i.e., a new Secondary Radar, or SCR). If this technological link had been in place, the Überlingen accident would probably not have happened.

9. Systemic Cognition and Human–AI Teaming

9.1. SCR Categories

Let us consider three types of SCRs in Rasmussen’s sense [67]: skill-based, rule-based, and knowledge-based. These types must be cross-referenced with three other factors of SCRs in the TOP model sense [36]: technological, organizational, or human (Table 1). For example, technological or organizational SCR rules or human SCR skills and knowledge could exist.

Table 1.

Types versus factors of SCRs.

This cross-referencing property is essential. Indeed, a rule-based technological SCR automates operational procedures typically handled by people, while a skill-based technological SCR automates human skills. Consequently, the shift in SCRs from people to technology can benefit people. Still, it is also likely to handicap people because it provides prostheses that remove human skills and competencies—the same thing for new organizational SCRs that may change cultures, regulations, and habits. Today, the renaissance of AI, with its intensive use of natural language generation, is distancing people from writing and speaking practices.

Doctolib is a French online booking platform allowing patients to book appointments with general practitioners or specialists. It is a very effective SCR in everyday situations (i.e., when there is no unexpected event). However, when unforeseen events occur, the health system’s complexity contributes to challenging and sometimes unpleasant situations. Let us provide a real example: a meeting was planned a month ago, and the patient went to the medical office. However, the secretary informed him that his appointment was canceled because the doctor was unavailable due to personal issues. The patient came from 120 km and was 73 years old. He was already tired and annoyed at having wasted a whole day traveling, as well as the cost of the fuel. He complained to the secretary, who said she was not responsible for this unexpected situation. He then asked who was responsible. She could not provide a name, except to suggest that the patient contact the virtual secretary dedicated to rescheduling an appointment. The problem here was trust. The patient, therefore, called the virtual secretary (i.e., another SCR), who gave him an appointment for 15 days later. He was not at all convinced about the commitment. Doctolib, as a technological rule-based SCR, turned out to be highly rigid and challenging to use effectively. Why? In addition to creating a complex problem-solving process due to its technology-centered engineering (i.e., not human-centered, by the fact that it does not consider traveling necessities for some people and unforeseen situations), it did not have the necessary skills to find a satisfactory solution to this unexpected situation for the suffering patient (e.g., instead of speaking with a real secretary who clearly explained what happened, the virtual secretary SCR had no clue about the traveling necessities).

9.2. The Shift from Control to Management to Collaboration

STSs involve shared awareness, communication, trust, and collaboration. People train to work in teams by learning to share situational awareness [68,69]. For example, making a commercial aircraft requires strong organizational business models, multi-agent complexity analysis, and personnel training. We must ensure that all team members, regardless of their size, either share the same corporate culture and values to work together and achieve objectives or can understand their cultural differences to adapt their situational awareness and behaviors accordingly.

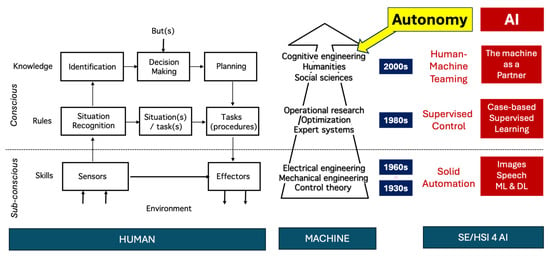

Human operators transitioned from controlling mechanical machines to managing highly computerized systems. This shift started in aviation during the 1980s. Human operators also shifted from manual to cognitive skills, from doing to thinking. Nowadays, we are exploring the shift from using a tool to collaborating with a technological partner. The single-agent era must give way to multi-agent frameworks, where agents encompass both humans and machines; we must master. Artificial agents will progressively learn from interactions with their environment, adapt to rapidly changing contexts, make independent decisions, and ultimately take critical roles within human–AI teams. Artificial agents will not be passive tools, but pro-active partners proposing solutions that can be discussed and challenged. However, it is essential to understand at which level these artificial agents will learn. In Rasmussen’s sense [67], it could be at the skill, rule, or knowledge-based level. Machine cognitive resources have changed from solid automation to supervisory control to human–machine teaming (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

The evolution of automation is based on Rasmussen’s model of human behavior, which shows the various types of artificial intelligence (AI) approaches.

9.3. Artificial Intelligence Has Multiple Cognitive Facets

Artificial intelligence (AI) also has several facets illustrated in Figure 7, where image and speech recognition, natural language processing, and connectionist machine learning can handle the skill-based behavioral level. Case-based reasoning, rule-based expert systems, and supervised machine learning are at the rule-based behavioral level. At the knowledge-based level, AI systems are no longer just tools but have become partners that require negotiation, delegation, and highly interactive capabilities. Regarding embedded AI systems, while we are increasingly confident about those at the skill-based and rule-based levels, the knowledge level remains exploratory. Indeed, when it is knowledge-based, human–AI teaming [70,71,72] requires considering AI-based technology not as a tool but as a partner. With this kind of new SCRs, where partnership, shared responsibilities, delegation, and authority are at stake, the pilot’s job changes profoundly.

Another change is the shift from following procedures to solving problems involving different cognitive resources. Before solving a problem, we need to state it correctly. This is something we hardly learn, if at all, at school. As a result, we often formulate problems incorrectly, and it is not surprising that the solutions are unsatisfactory. Teamwork between humans and artificial intelligence will require even more attention in this respect. Problem statements must be clearly established, shared, and discussed cooperatively within a human–machine team.

Moreover, AI is not limited to data processing tools. AI can be a partner that enhances human capabilities. It can learn from experience. People using AI need to familiarize themselves with the different personalities that AI partners can have. A long anthropological journey will be required better to understand the mutual familiarization of human agents and machines. Key issues include human–AI team coordination, regulatory and social rules, and the development of new human behaviors, knowledge, and skills. Mastering these issues is crucial to ensure effective situational awareness, informed decision-making processes, collaboration, trust, and optimal operational performance. We have modeled these vital resources, as illustrated by the results of the MOHICAN project [72].

9.4. Looking for Technological, Organizational, and Human Autonomy

The autonomy issue deserves more attention. In Figure 7, autonomy is attributed to the knowledge-based behavioral level, assuming that the rule-based and skill-based levels are sufficiently mature to manage the overall maturity of the system under consideration. SCRs are attached to each behavioral level. The appropriateness and consistency of these SCRs determine the system’s maturity. In addition, the autonomy of a system of systems (refer to Figure 4) depends on the maturity of the STSs and the appropriate dependencies among them (i.e., each STS can be supported by others through their SCRs).

The novelty of human–AI teams lies in the social/organizational perspective combined with the task execution duties. The syndrome of a human facing a single machine, which requires the development of user interfaces, is a thing of the past. We are entering an era of human and machine multi-agent collaborative work (i.e., a system of human and machine systems). Human–AI teams require more robust models of systemic cognition that define the distinct elements involved (i.e., human and machine models), as well as multi-agent architectures that outline the interconnections and the various achievable objectives or purposes of these teams. These models should integrate the knowledge needed to address complexity issues at various behavioral levels.

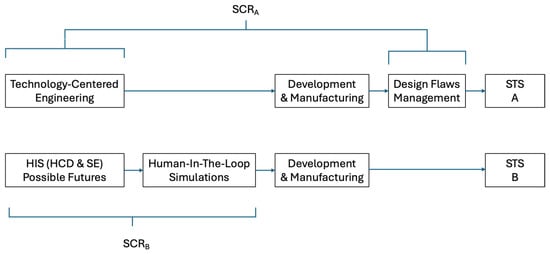

10. Systemic Cognition and Cost Management

Managing an STS, such as an aeronautical company, involves all the above, which must be associated with costs, benefits, and potential losses. Let us compare the technology-centered engineering process toward an STS A and the human systems integration involving possible futures (scenarios) that require human-in-the-loop simulations (HITLS) that support assessing potential activities. In the Boeing 737 Max MCAS disaster case, the cost of SCRA, which necessarily includes design flow management compensating for the lack of human-centered design (HCD), has been demonstrated to be much higher than the cost of SCRB, which would have included HITLS and HSI methodology since the beginning of the design process (Figure 8).

Management is often reluctant to invest in HSI during the design and development phases, as it is perceived as an unnecessary and additional process. However, if we do not consider human and organizational factors in the early stages of design, correcting the defects caused by this omission will be much more expensive. Furthermore, the HSI-centered design will make the STS B better than the STS A from an operational point of view, as it is based on usage and experience scenarios. (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Comparing technology-centered engineering and HSI processes.

Consequently, it is imperative to develop fair cost analyses that compare the investment in an HSI infrastructure with the recovery costs that would be incurred without such investment. A first set of calculations can be performed by considering relevant aircraft accidents. Therefore, it is recommended that such cost analyses be conducted whenever a new STS project is initiated, and that the calculations be updated incrementally to reflect ongoing changes. Such calculations are crucial to support decision-making throughout the entire life cycle of an STS, but most importantly, from the beginning.

Finally, HSI-centered cost management must be intimately linked to sociotechnical issues, with long-term considerations, rather than being restricted by short-term benefits, to contribute effectively to the overall sustainability of STS.

11. Four Contributing Projects

Four primary industrial research and development projects have substantially contributed to the development of the systemic cognition framework by providing experience-based knowledge over the last six years, in a constructivist manner. These projects were carried out as part of the duties coordinated by the author within the FlexTech Chair. Let us examine them briefly.

11.1. The Air Combat Virtual Assistant Project