Abstract

Financial institutions increasingly rely on data-driven decision systems; however, many operational models remain purely predictive, failing to account for confounding biases inherent in observational data. In credit settings characterized by selective treatment assignment, this limitation can lead to erroneous policy assessments and the accumulation of “methodological debt”. To address this issue, we propose an “Estimate → Predict & Evaluate” framework that integrates Double Machine Learning (DML) with practical MLOps strategies. The framework first employs DML to mitigate selection bias and estimate unbiased Conditional Average Treatment Effects (CATEs), which are then distilled into a lightweight Target Model for real-time decision-making. This architecture further supports Off-Policy Evaluation (OPE), creating a “Causal Sandbox” for simulating alternative policies without risky experimentation. We validated the framework using two real-world datasets: a low-confounding marketing dataset and a high-confounding credit risk dataset. While uplift-based segmentation successfully identified responsive customers in the marketing context, our DML-based approach proved indispensable in high-risk credit environments. It explicitly identified “Sleeping Dogs”—customers for whom intervention paradoxically increased delinquency risk—whereas conventional heuristic models failed to detect these adverse dynamics. The distilled model demonstrated superior stability and provided consistent inputs for OPE. These findings suggest that the proposed framework offers a systematic pathway for integrating causal inference into financial decision-making, supporting transparent, evidence-based, and sustainable policy design.

1. Introduction

1.1. From Prediction to Prescription: The Evolution of Data-Driven Decision Making

Over the past decade, advances in data science and artificial intelligence have fundamentally reshaped corporate decision-making. Early analytical practices centered on descriptive analytics, answering the fundamental question, “What happened?”. With the rise of machine learning (ML), the emphasis shifted toward predictive analytics, enabling firms to estimate “What is likely to happen next?”. However, in environments characterized by persistent uncertainty—financial crises, pandemics, and abrupt interest-rate movements—prediction alone is often insufficient for strategic intervention. For example, merely identifying that a customer has a high probability of delinquency does not prescribe that a standard intervention is the optimal strategy to mitigate that risk or prevent the outcome altogether [1].

Ensuring long-term sustainability therefore requires moving beyond forecasting and addressing a prescriptive question: “What intervention will causally reduce this customer’s likelihood of becoming delinquent?”. This is the core of prescriptive analytics. Crucially, this shift is not merely methodological but conceptual. Predictive models primarily leverage correlations—patterns of co-movement among variables—whereas prescriptive analytics demands insight into causal mechanisms, i.e., how specific actions drive changes in outcomes. While correlation describes co-occurrence, causation explains the mechanisms of change and their specific pathways. For sustainable management—where resource allocation and proactive risk mitigation are central—accurately estimating causal effects becomes indispensable.

1.2. The Importance of Causal Prescription: Credit Risk Management and Targeted Marketing

In the financial industry—particularly in credit risk management and targeted marketing—the failure to distinguish causal effects from spurious correlations can lead to severe consequences. A policy that uniformly reduces credit limits for customers predicted to have high delinquency risk may appear intuitive from a correlational standpoint. However, from a causal perspective, such a policy can be counterproductive or even catastrophic. For some customers, a limit reduction may serve as a useful constraint that prevents delinquency—the “Persuadable” segment. For others, the same intervention can act as a detrimental trigger that pushes them toward financial distress or even default—the “Sleeping Dogs” [2]. Indiscriminate intervention without identifying these adverse-response groups can erode the stability of the financial system and threaten long-term profitability. Thus, prescriptive analytics functions not merely as a tool for short-term profit optimization but as a fundamental mechanism for ensuring the system’s long-term viability and sustainability.

However, the opacity of traditional predictive models creates a critical barrier to adoption. Because these models often fail to distinguish actionable causality from spurious correlation, they struggle to meet the strict regulatory standards and safety requirements essential for core financial operations. Consequently, despite their potential, advanced algorithmic techniques have faced resistance in practice.

To operationalize this causal perspective, this study proposes a rigorous “Estimate → Predict & Evaluate” framework that integrates double machine learning (DML) with practical MLOps strategies. Within this framework, we leverage Uplift Modeling—a technique designed to estimate the incremental impact of a treatment at the individual level—to optimize decision-making. We begin by analyzing the structural success of a patented uplift framework in marketing contexts and then extend its logic to high-stakes credit risk management. Specifically, we address the following three research questions (RQs):

- (1)

- RQ1: Why was the two-stage architecture—separating causal estimation from targeting—effective in the patented uplift system used for marketing campaigns?

- (2)

- RQ2: How can computationally intensive causal models be efficiently distilled into deployable Target Models to enable real-time decision-making and robust off-policy evaluation (OPE)?

- (3)

- RQ3: Can this “Estimate → Predict & Evaluate” framework be successfully extended to high-confounding environments by utilizing double machine learning (DML) to address complex selection bias?

1.3. Contribution of This Study: A Sustainable “Estimate → Predict & Evaluate” Architecture

To bridge the gap between the theoretical importance of heterogeneous treatment effects [3] and the practical limitations of current industrial practices, this study proposes an integrated two-stage framework that synthesizes the strengths of both “data modeling” and “algorithmic modeling” cultures. The “Estimate → Predict & Evaluate” architecture provides a rigorous yet operationally feasible blueprint for causal targeting. While building upon the established rigor of double machine learning (DML) for causal estimation, the primary contribution of this study lies in the architectural integration of patented industrial logic (Korean Patent No. 10-2414960 [4]) with causal inference to systematically repay “methodological debt” and its expansion toward off-policy evaluation (OPE). The framework consists of two sequential components:

- (1)

- The Estimation Stage (Methodological Foundation): This stage employs double machine learning (DML), a methodology known for its econometric rigor, to control selection bias and confounding inherent in observational financial data. By isolating causal relationships from spurious correlations, DML yields unbiased individual-level conditional average treatment effect (CATE) estimates. Conceptually, this stage performs a “causal audit” on the data, stripping away noise induced by endogenous treatment assignment.

- (2)

- The Prediction & Evaluation Stage (Principal Contribution): The core innovation is the adaptation of the patented SHAP-Uplift Target Model into a causal-prescriptive context. We propose a knowledge-distillation process where DML-derived CATE estimates serve as training labels for a scalable, real-time Target Model. Through this knowledge-distillation process, the structural insights uncovered by DML are transferred into a lightweight predictive model suitable for real-time deployment. The resulting predictions form the backbone of off-policy evaluation (OPE) [5,6], enabling institutions to assess the expected performance of hypothetical interventions within a “Causal Sandbox”—a safe, counterfactual simulation environment in which untested policies can be evaluated without exposing actual customers to risk.

This two-stage architecture presents a concrete pathway for transforming high-risk heuristic decision systems into principled, causally grounded operational frameworks. Unbiased CATE estimates obtained with DML support the design of prescriptive targeting policies, while OPE quantifies the expected outcomes of these policies using historical data alone. Collectively, the proposed approach establishes a closed-loop system that links econometric identification, machine-learning scalability, and business value realization in a coherent and sustainable manner.

2. Theoretical Background and Related Work

This section reviews the fundamental theories underpinning our framework, focusing on the potential outcomes framework, causal machine learning, and the limitations of existing uplift modeling approaches in finance.

2.1. The Goal: Defining Causal Effects via Potential Outcomes

The Neyman–Rubin potential outcomes framework—the mathematical foundation of modern causal inference—provides a precise language for defining causal relationships. At the core of this framework lies the notion of counterfactual.

For each individual i, one can conceptualize two potential outcomes:

- (1)

- Yi(1), the outcome in a world where the individual receives the treatment (Di = 1), and

- (2)

- Yi(0), the outcome in a world without treatment (Di = 0)

The individual treatment effect (ITE) is defined as the difference between these two potential outcomes, . However, only one of these two counterfactual states can be observed for any given individual; the other necessarily remains unobserved. This impossibility of jointly observing both outcomes constitutes the Fundamental Problem of Causal Inference. As individual-level causal effects cannot be directly computed, researchers instead aim to estimate conditional average treatment effects (CATE), the expected difference in outcomes for individuals with similar characteristics.

A key identification requirement for estimating CATE from observational data is strong ignorability. This assumption states that, conditional on a sufficiently rich set of covariates , treatment assignment D is independent of the potential outcomes. Pearl’s graphical causal framework formalizes this requirement through the back-door criterion [7], emphasizing that all confounding paths must be blocked to recover unbiased causal effects from non-experimental data.

Formally, CATE is defined as:

This framework, established by Rubin’s foundational work [8], provides the bedrock for modern causal inference.

Reliable estimation of CATE enables a principled segmentation of the population into four causally meaningful groups, each associated with a distinct strategic implication for resource allocation:

- (1)

- Persuadables: Individuals who respond positively only when treated. These are the ideal targets for marketing actions or credit-policy interventions.

- (2)

- Sure Things: Individuals who achieve favorable outcomes regardless of treatment. Allocating resources to this group generates unnecessary deadweight loss.

- (3)

- Lost Causes: Individuals who exhibit negative outcomes regardless of treatment. Interventions here yield negligible benefit.

- (4)

- Sleeping Dogs: Individuals who exhibit worse outcomes because of the treatment. In credit settings, reducing limits for such customers can elevate delinquency risk and threaten portfolio stability.

This classification is not a matter of convenience but one of organizational survival under sustainable management. Excessive benefits to “Sure Things” drain resources needed elsewhere; neglecting “Persuadables” diminishes intervention effectiveness; and triggering “Sleeping Dogs” may escalate defaults, reduce household financial resilience, and impose significant social costs. During periods of credit stress, misguided targeting can widen the financially vulnerable population or exacerbate systemic indebtedness [9].

Hence, the ability to estimate CATE with high fidelity is not an optional sophistication—it is a foundational capability for maximizing utility under resource constraints while minimizing systemic and operational risk [10].

2.2. The Challenge: Selection Bias in Observational Financial Data

While estimating CATE is crucial, achieving it in practice poses significant challenges. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) address the causal inference problem elegantly by ensuring that treatment assignment is statistically independent of underlying characteristics, thereby guaranteeing balance between treated and control groups. In contrast, most business datasets—and virtually all credit risk datasets—are observational rather than experimental. In observational settings, treatment assignments are often correlated with key behavioral or risk attributes, giving rise to selection bias.

For example, if high-risk borrowers are systematically more likely to be targeted for a credit limit reduction, the borrower’s underlying delinquency risk becomes a confounder that influences both treatment assignment and subsequent outcomes. Without appropriate controls, a naïve comparison of delinquency rates between treated and untreated customers may lead to severely misleading conclusions. Observing a higher delinquency rate among customers who received a limit reduction does not imply that the reduction “caused” delinquency; more plausibly, those customers were assigned the treatment precisely because they were already at elevated risk.

Thus, observed outcome differences reflect a mixture of true treatment effects and pre-existing risk differentials. To obtain valid causal estimates, one must condition on a sufficiently rich covariate set X to block all back-door paths connecting treatment and outcome. When the back-door criterion is satisfied, causal effects can be recovered, even in the absence of randomized assignment.

2.3. Existing Approaches: Uplift Modeling and the Limits of Correlation

Uplift modeling serves as the practical implementation of CATE estimation in business analytics. Unlike standard predictive models that estimate the probability of an outcome , uplift models directly estimate the change in probability due to a treatment (i.e., the incremental impact). Traditionally, the Two-Model approach—formally classified as the T-Learner in the meta learning literature [11]—has been widely adopted [12]. In this framework, separate predictive models are trained for the treatment and control groups, and uplift is computed as the difference between the two predicted outcomes. However, this method suffers from compounded prediction errors; noise from both models accumulates, making it difficult to detect true treatment effects, particularly when the underlying signal is weak.

While uplift modeling has evolved to address heterogeneity, interpretability remains a challenge. Addressing this, Shoko et al. [13] recently proposed a framework combining SHAP values and Partial Dependence Plots (PDPs) to enhance the interpretability of credit risk models. SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) values, grounded in cooperative game theory, provide a unified measure of feature importance by attributing the prediction output to each input feature [14]. Building upon this foundation of predictive transparency, our study aims to extend the analytical scope to rigorous causal estimation. In high-stakes decision-making where confounding variables exist (e.g., credit limit assignments), distinguishing between spurious correlation and actionable causality is vital. Therefore, we incorporated double machine learning (DML) to complement the interpretability provided by Shoko et al., ensuring that policy decisions are grounded in estimated causal mechanisms.

2.4. The Solution: Econometric Identification via Double Machine Learning (DML)

To overcome the shortcomings of heuristic approaches and achieve genuinely causal prescriptions, this study adopted double machine learning (DML) as its core analytical engine. First introduced by Chernozhukov et al. [15], DML represents a hybrid methodology that combines the predictive flexibility of machine learning with the identification rigor of econometrics. Recent studies have successfully adapted this framework to complex financial domains, including industry-distress effects on loan recovery, the causal drivers of bond indices, and structural monetary policy transmission [16,17,18]. Its central idea is to leverage the partially linear model framework and the principle of orthogonalization to purge confounding effects from observational data. The procedure unfolds in three steps:

- (1)

- Estimation of nuisance functions.

High-performance machine learning algorithms (e.g., random forests, lasso regression) are used to estimate the components of the outcome and treatment assignment that are predictable from covariates. Specifically, models are trained to predict and

- (2)

- Double residualization.

Observed values are “purified” by subtracting the nuisance predictions, producing the residual outcome and residual treatment:

This step removes the variation in Y and D that is explained by covariates, thereby eliminating confounding pathways embedded in g(X) and m(X).

- (3)

- Estimation of the causal effect.

A regression of the residualized outcome on the residualized treatment yields an estimate of the treatment effect τ that is orthogonal to errors in the nuisance models [19].

This process systematically isolates the pure causal relationship by stripping away confounding effects layer by layer. Moreover, DML necessarily employs cross-fitting to eliminate overfitting bias. Through this rigorous procedure, DML attains strong statistical properties such as consistency and asymptotic normality, ensuring that the resulting CATE is not merely a point prediction but a statistically valid and robust estimator.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Description

To rigorously validate our framework across different causal regimes, we employed two distinct real-world datasets: a low-confounding marketing dataset (Case A) and a high-confounding credit risk dataset (Case B).

3.1.1. Case A: Marketing Uplift Data (Samsung Card)

For the low-confounding marketing environment (Case A), we utilized a dataset sourced from Samsung Card. The data collection focused on constructing a retrospective cohort of credit card borrowers to analyze the impact of targeted marketing on customer response. As a direct credit card issuer, the institution retains full control over the marketing channel, making Randomized Controlled Trials (A/B testing) operationally feasible. Consequently, this environment allows for the construction of a dataset with minimal confounding, serving as a “ground truth” benchmark. To ensure data quality, we restricted the cohort to customers holding an active credit account with a valid balance during the observation window. This curated data served as the input for the SHAP-Uplift Target Model (discussed in Section 3.2).

To maximize predictive power and capture subtle customer behavioral patterns, the raw transactional data underwent a rigorous feature engineering process. The resulting dataset comprised 1149 variables. This high-dimensional feature space was constructed by combining approximately 650 basic variables (e.g., demographics, transaction records) and a balance of sector-specific and time-series variables, alongside 101 newly engineered financial variables. Specifically, 1048 existing variables were engineered across eight behavioral dimensions: Personal Data, Card Usage, Credit & Limit, Loan Usage, Lock-in & Service Usage, Channel Contact, Sector Usage, and External Account Opening. This comprehensive structure ensures that the downstream model has access to a granular view of customer activity. The specific composition of these categories is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Description of Key Dimensions Prepared for the Marketing Uplift Model.

3.1.2. Case B: Credit Risk Data (PFCT)

In contrast to the marketing dataset, Case B utilizes a proprietary dataset from PFCT to validate our framework in a high-confounding environment. Since PFCT relies on aggregated Credit Bureau (CB) information rather than direct channel control, executing controlled A/B tests is structurally impossible. Consequently, this dataset reflects a realistic credit risk management scenario characterized by strict selection bias, where treatment assignment is highly correlated with borrower risk profiles.

The dataset spans two distinct observation periods: January to June 2022 and January to June 2023, ensuring that the model’s performance is robust across different macroeconomic conditions. It comprises a total of 2295 variables, specifically engineered to assess borrower solvency and delinquency probability. These variables, referred to as the Risk Features, serve as the core covariates () in our DML framework. The richness of this feature set is critical for satisfying the strong ignorability assumption as it captures a multidimensional view of a borrower’s financial health, ranging from traditional credit scores to detailed loan and delinquency histories. The key feature categories are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Description of PFCT Risk Features for the Credit Policy Model.

3.2. The Strengths and Limitations of a Heuristic Approach: The SHAP-Uplift Target Model

Uplift modeling has long been employed in marketing to estimate the causal effect of a treatment on individual behavior. To overcome the compounded estimation errors inherent in traditional approaches (discussed in Section 2.3), Samsung Card developed and patented the SHAP-Uplift Target Model, a two-stage framework that leverages model explainability.

In the first stage, a unified predictive model (e.g., XGBoost) is trained on the combined dataset with treatment status included as a feature. Once trained, the SHAP value (Lundberg & Lee [14]) associated with the treatment feature is computed for each individual. This SHAP attribution is then interpreted as a proxy for the individual’s uplift—or more precisely, a proxy for CATE.

In the second stage, these SHAP-based uplift scores are used as labels to train a downstream supervised learning model (the Target Model). This model takes customer covariates X as inputs and predicts the uplift score, ultimately serving as a scalable targeting mechanism. Because the pipeline relies on a single predictive model in the initial stage, training tends to be more stable and integrates seamlessly with existing machine-learning workflows.

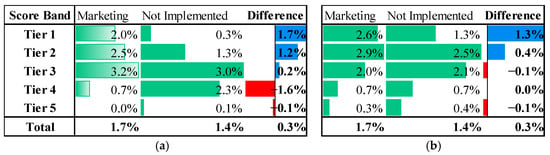

The comparative performance results presented in Figure 1 demonstrate that this approach mitigates the instability (e.g., rank reversal) commonly observed in conventional two-model approaches.

Figure 1.

Comparison of uplift modeling performance. (a) Conventional Two-Model approach; (b) single-model, two-stage SHAP-Uplift Target approach.

However, this methodology is valid only if the SHAP value of the treatment variable is a reliable approximation of the true CATE. This key assumption holds theoretically only when the treatment assignment D is independent of the covariates (), specifically in a perfectly Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) setting.

In such randomized environments, confounding is eliminated by design, allowing the feature attributions produced by the prediction model (SHAP values) to align with causal effects. The critical weakness of this methodology lies in its implicit causal interpretation of correlations in non-experimental settings. When confounders are not properly controlled, the SHAP value of the treatment variable reflects not only the pure treatment effect but also the influence of confounding variables that are systematically associated with the treatment.

In other words, using the SHAP value in place of no longer answers “How much did the treatment change the outcome?” but rather “How much did the treatment variable contribute to predicting the outcome?”. This discrepancy can deviate significantly from the causal quantity of interest in highly confounded settings. Such heuristic approaches, which ignore bias from confounding, can create an “illusion of causality”, posing a major risk factor that undermines efforts to build a sustainable financial system.

3.3. System-Level Integration: The DML-Then-Target Workflow and the Causal Sandbox

While DML provides statistically rigorous individual-level CATE estimates, directly deploying these estimates in real-time business decision systems presents practical challenges. DML involves a complex two-stage procedure, requires substantial computational resources, and can exhibit high variance at the individual level. To bridge the gap between econometric rigor and operational efficiency, we propose the DML-then-Target architecture, which serves as the primary methodological framework for the high-confounding credit policy analysis in Case B, drawing inspiration from knowledge distillation in deep learning and informed by practical insights from SHAP-Uplift Target.

The workflow operates sequentially.

- (1)

- First, DML serves as the teacher model, extracting refined causal signals (τ) from historical data.

- (2)

- Second, a supervised learning model—such as LightGBM or a deep neural network—acts as the student model. It is trained to predict the DML-estimated CATEs using only observable customer features X as inputs. In other words, the Target Model learns from the DML outputs treated as labels. This process transcends mere replication: the Target Model smooths out the statistical noise inherent in individual DML estimates and internalizes only the structural patterns linking inputs to treatment effects. From an MLOps perspective, heavy causal computations occur offline, while a lightweight and operationally efficient model is deployed in production environments, enhancing flexibility and scalability.

- (3)

- A final and essential step is verifying the effectiveness of the developed targeting policy. In high-stakes domains such as credit policy, conducting live experiments (e.g., A/B tests) is often constrained by ethical considerations and the risk of significant financial loss. Here, the Target Model—produced by the DML-then-Target workflow—serves as the foundation for off-policy evaluation (OPE). Specifically, the refined CATE predictions generated by the architecture are used to construct a hypothetical optimal policy π that assigns treatments to customers. The expected performance of this policy can then be unbiasedly estimated using inverse propensity weighting or doubly robust estimators.

In summary, the framework transforms historical data into a Causal Sandbox, enabling institutions to evaluate and compare numerous policy scenarios before implementation. This approach substantially mitigates operational risks associated with trial-and-error and supports the development of sustainable, evidence-based policies.

3.4. Unified Evaluation Mechanism: Operational Equivalence and OPE

A critical advantage of the proposed framework is the operational equivalence between the baseline SHAP-Uplift Target Model and the proposed DML-then-Target architecture. While their underlying estimation engines differ—one relies on heuristic feature attribution (SHAP) and the other on orthogonalized causal inference (DML)—both employ an identical two-stage distillation process.

In the SHAP approach (Section 3.2), the generated SHAP values function as proxy labels to train a downstream Target Model. Similarly, in the DML-then-Target approach (Section 3.3), the DML-estimated CATEs serve as training targets for a corresponding Target Model. Consequently, the final output in both cases is a scalar prediction generated by a supervised learning model. Since both outputs share this identical mathematical structure, the off-policy evaluation (OPE) framework validated in the marketing context can be directly transferred to the credit policy context. This allows us to rigorously evaluate the DML-based policy in high-stakes environments (Case B) using the same counterfactual logic that was empirically substantiated in the low-risk environment (Case A).

4. Results: Contrasting Case Studies from Financial Data

To empirically validate the effectiveness of the proposed framework, we present analyses of two contrasting operational environments. The logical progression of our analysis is twofold:

- (1)

- Validation of the Target Model & OPE Framework (Case A): First, we utilized the marketing dataset, where randomized controlled trials (A/B tests) were feasible. Here, we demonstrate that the predictions from the SHAP-based Target Model closely align with the actual experimental outcomes. This serves as a “ground-truth” validation, confirming that the “Proxy Label → Target Model → OPE” mechanism is reliable.

- (2)

- Application to High-Confounding Domain (Case B): Leveraging the validation from Case A, we then applied the DML-based Target Model to the credit policy dataset. Although live experimentation was infeasible here due to risk, the operational equivalence established in Section 3.4 allows us to confidently use OPE to identify adverse-effect segments (Sleeping Dogs) that heuristic models miss.

4.1. Case A: A Low-Confounding Environment—Randomized Marketing Campaigns

Case A draws on data from a credit-loan interest discount campaign conducted by Samsung Card. In this setting, the assignment of customers to the treatment and control groups was designed to be quasi-experimental, resulting in a setting with minimal confounding. We applied the SHAP-Uplift Target Model—previously compared with the Two-Model approach in Section 3.2—to estimate each customer’s uplift score (expected incremental response probability) and segment customers into multiple uplift tiers.

The model identified several key predictors contributing to uplift (i.e., expected interest-income gains), including recent surges in loan balances, frequency of cash-service usage, and revolving balance ratios. These findings align with standard financial-marketing intuition: customers who exhibit stronger liquidity demand tend to be more responsive to interest-rate incentives.

To validate the model’s effectiveness, we executed a large-scale campaign. We constructed the treatment group (approximately 220,000 customers who received the discount offer) and the control group (approximately 25,000 customers who did not) using a randomized assignment protocol prior to campaign execution. Table 3 compares the firm’s previous marketing strategy with the new uplift-based approach. Whereas the firm’s prior practice had been to differentiate offers based on predicted response probability, the test campaign instead targeted customers with the highest uplift scores.

Table 3.

Comparison of Pre- and Post-Uplift Marketing Policy Evaluation.

This strategy successfully identified highly persuadable customers, leading to a statistically significant increase in interest revenue. Table 4 details the quantitative performance metrics of the campaign. Notably, the uplift-based approach resulted in a relative interest rate increase of 0.55%p and an incremental loan volume of KRW 1.9 billion, even while reducing the offered discount by 3.00%p compared to the control group.

Table 4.

Performance metrics of the uplift-based interest rate discount campaign.

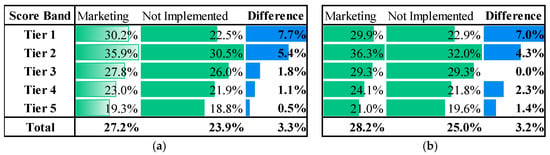

The second experiment was conducted using the same uplift score tiers, but with a different marketing policy—fuel discount benefits. In this campaign, approximately 38,000 customers were randomly assigned to treatment and 2000 to the control. Again, the SHAP-Uplift model was applied, and the resulting test campaign confirmed uplift effects in the top-tier customer segments identified by the model, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Uplift effects in customer segments for the fuel discount campaign. (a) Predicted Evaluation. (b) Test Result.

Across both randomized marketing campaigns—interest discount and fuel discount—the SHAP-Uplift Target Model reliably identified high-uplift segments and increased revenue, providing strong evidence of its practical usefulness. Crucially, these results demonstrate that the Target Model produced by the distillation pipeline can serve as a foundation for off-policy evaluation (OPE). This confirms that the framework functions as a practical Causal Sandbox, enabling firms to simulate new strategies using historical log data without conducting costly or risky live experiments.

The overarching implication is clear: in environments where confounding is minimal and treatment assignment approximates randomization, correlation-based explanatory tools such as SHAP can serve as reasonable proxies for causal effects. More importantly, the successful alignment between OPE estimates and A/B test outcomes in this “clean” environment serves as a vital proof-of-concept for our evaluation methodology. Building on this empirical ground truth, we now turn our attention to the high-stakes environment (Case B), a setting where such direct testing is structurally impossible but where the need for causal rigor is most acute.

4.2. Case B: A High-Confounding Environment—Applying and Evaluating the DML-Then-Target Workflow

Case B addresses a scenario involving a credit limit adjustment policy (e.g., increasing the minimum payment ratio) that is selectively applied to high-risk customers. This setting represents a typical credit policy environment characterized by the coexistence of strong confounding and selection bias. Prior work by Huh and Kim [20,21] demonstrates that in such highly confounded environments, a double machine learning (DML) framework can systematically adjust for high-dimensional and nonlinear confounding factors.

Crucially, this approach facilitates the identification of a specific customer segment for whom the policy appears beneficial on the surface but is, in fact, detrimental—the so-called Sleeping Dogs. For these customers, a limit-tightening policy paradoxically increases delinquency rates. Reliance on naïve observational analysis would likely deem the policy effective based solely on short-term delinquency metrics. However, after accounting for confounding factors such as underlying risk profiles, DML reveals that the policy’s pure causal effect is negative. Identifying this dynamic is essential for preventing financial losses arising from misguided interventions.

4.2.1. High-Confounding Environment: Implementation of the Workflow

Utilizing the proprietary dataset from PFCT, we implemented the DML-then-Target workflow and evaluated its performance. In the training phase, we first employed double machine learning (DML) to estimate individual-level conditional average treatment effects (CATEs). These DML-estimated treatment effects were then transformed into training labels for an XGBoost-based Target Model.

The Target Model is designed to predict the probability that a new customer belongs to the “Sleeping Dog” segment—customers whose delinquency risk escalates when the credit policy is applied. This probability serves as a core input for subsequent off-policy evaluation (OPE). Under this framework, the resulting prescriptive policy rationale is straightforward: customers identified by the DML-then-Target Model as having a high probability of being Sleeping Dogs should be excluded from the credit policy intervention. Using OPE, the institution can compare numerous candidate policies and identify the optimal strategy prior to deployment, thereby circumventing the risks associated with traditional trial-and-error.

4.2.2. Experimental Design

To rigorously validate the framework, we conducted two empirical experiments using the PFCT data:

- (1)

- Experiment 1: Training on January–April 2022 data; testing on May–June 2022;

- (2)

- Experiment 2: Training on January–April 2023 data; testing on May–June 2023.

In both experiments, treatment groups were defined using a data-driven thresholding method. Based on prior months’ claim-ratio differences, we performed a grid search over candidate percentiles to determine two thresholds (p1, p2). These thresholds partitioned the population into three regions: (−∞, p1], (p1, p2], (p2, ∞). We selected the threshold pair that maximized the chi-square statistic of the resulting contingency table between treatment assignment and binary delinquency outcomes.

To prevent overfitting and lookahead bias, we implemented strict evaluation protocols, including full separation of training and test periods, repeated threshold search, and independent execution of the DML and Target stages.

4.2.3. Model Comparison

Two candidate selection strategies were compared:

- (1)

- Candidate A—Direct DML Selection:

Group-level LinearDML models were fitted during the training period to estimate CATEs. The top 10% individuals were selected directly from these DML predictions and evaluated in the test period.

- (2)

- Candidate B—Target Model (Distilled Selection):

Using DML-estimated “top 10% membership” as the training label, we trained a simple fully connected neural network (2–3 layers, optimizer AdamW, 8 epochs). In the test period, the individuals selected by this model (the top 10%) were evaluated.

To ensure a fair comparison, we re-estimated “test-only CATE” for all selected individuals using a DML model trained exclusively on the test data. This removes selection bias and provides unbiased ground truth for evaluation.

4.2.4. Performance Evaluation

Across both experiments, the Target Model (Candidate B) consistently outperformed the direct DML selection (Candidate A) in terms of both average CATE and hit ratios. The detailed results for each year are presented in Table 5 and Table 6.

Table 5.

Experiment Results for 2022.

Table 6.

Experiment Results for 2023.

- (1)

- In 2022, the Target Model improved the mean CATE of the top decile by +0.0023 and increased the hit ratio by +0.3 percentage points.

- (2)

- In 2023, improvements were even greater: the mean CATE increased by +0.0026, and the hit ratio rose by +1.3 percentage points.

This performance gain suggests that the distillation process effectively mitigates statistical noise inherent in individual DML estimates and enhances model generalization.

The substantial performance advantage of the Target Model—particularly in 2023, where the hit ratio of the unique selections made by Candidate B (42.13%) far exceeded that of Candidate A (28.31%)—demonstrates that the distilled model exhibits greater robustness to macroeconomic shifts and temporal instability.

Overall, the empirical findings illustrate that the DML-then-Target architecture not only captures the underlying causal structure but also operationalizes it into actionable, scalable policy tools. The workflow enables a complete cycle of causal inference, model deployment, and ex-ante policy validation, bridging the gap between statistical rigor and real-world financial decision-making.

5. Discussion: Credit Risk as a Complex System and the Restoration of Causal Validity

This study proposes a new methodological framework for sustainable decision-making in modern financial systems, where opportunities created by explosive data growth coexist with heightened uncertainty. Building on the empirical analyses in Section 4, this section examines the proposed framework through the lenses of systems theory, behavioral economics, and sustainable finance. In particular, we conceptualize the widespread practice of deploying predictive models without addressing observational bias as a form of “methodological debt”, and explore how the DML-then-Target architecture offers a systemic remedy.

5.1. The Clash of Two Modeling Cultures and a Third Way: Causal Systems Modeling

Leo Breiman’s [22] distinction between the “data modeling culture” and the “algorithmic modeling culture” has shaped the trajectory of financial analytics over the past two decades. Credit risk management has traditionally been aligned with the data modeling culture, relying on logistic regression and other parametric models to satisfy regulatory expectations for transparency and stability. In contrast, areas such as marketing and fraud detection have embraced the algorithmic modeling culture—deep learning, boosting, and other machine-learning approaches—to maximize predictive accuracy.

However, constructing a sustainable financial system requires moving beyond this dichotomy. Case B, the high-confounding credit policy environment in our empirical analysis, starkly illustrates the limitations of algorithmic culture. Although the SHAP-Uplift model based on XGBoost performed well in prediction tasks, it failed to distinguish between two fundamentally different mechanisms: whether a credit-limit reduction causes delinquency, or whether high-risk customers are simply more likely to be assigned such reductions. This is a classic manifestation of the “Rashomon Effect” described by Breiman—many models may fit the data well, yet tell profoundly different stories about the underlying causal structure.

The DML-based approach proposed in this study offers a “third way”: Causal Systems Modeling. DML draws upon the predictive flexibility of machine learning (algorithmic culture) while retaining the identification discipline of econometrics (data modeling culture), enabling the unbiased estimation of the treatment effect. This is more than a technical hybrid; it represents a conceptual shift from pattern recognition based on correlation to structural understanding based on causality. For a business model to be sustainable, it must withstand external shocks. Such resilience is possible only when the system’s causal mechanisms are properly understood—and when decision rules are grounded in validated causal effects rather than superficial associations.

5.2. Methodological Debt in Financial Systems and Its Repayment

Just as “technical debt” in software engineering refers to short-term shortcuts that compromise long-term code quality, this study introduces the concept of “methodological debt” in the domain of data-driven decision-making. Methodological debt arises when organizations operating in environments with complex causal structures and pronounced selection bias adopt simple correlation-based predictive models as decision engines, often driven by convenience, computational speed, or cost reduction.

In high-confounding settings such as Case B, this debt is initially invisible. Heuristic models may appear to perform well in predicting short-term delinquency, creating an illusion of accuracy and effectiveness. However, these early gains are deceptive. Over time, methodological debt accrues “interest”, gradually distorting decision pipelines and ultimately threatening the stability of the entire financial system.

A central tenet of systems thinking is the recognition of feedback loops. Credit risk management is not a static classification task but a dynamic system in which customers and financial institutions continually interact. When decision-making is guided by models that misinterpret correlation as causation, a harmful positive feedback loop can emerge, amplifying instability. The accumulation mechanism of methodological debt unfolds as follows:

- (1)

- Correlation learning:

A correlation-based model identifies a strong association between “credit limit reduction” and “delinquency”.

- (2)

- Causal misinterpretation:

The model treats this correlation as causal or fails to identify the Sleeping Dog segment, recommending limit reductions indiscriminately.

- (3)

- Policy execution:

The institution acts on these recommendations, applying stricter policies to customers who are highly sensitive to liquidity shocks.

- (4)

- Real-world outcomes:

These customers respond with increased delinquency, not because of inherent risk, but because the policy itself triggers financial stress (the Sleeping Dog effect).

- (5)

- Feedback amplification:

The newly generated delinquency data re-enter the training pipeline, reinforcing the false belief that “limit-reduction recipients are high-risk”, thereby further entrenching model bias.

This self-reinforcing cycle can produce a “death spiral”—not only expanding the financially vulnerable population but also pushing otherwise stable customers toward default. As Sculley et al. [23] warned in the context of machine learning systems, hidden forms of technical debt can accumulate unnoticed until they manifest as systemic failures. In finance, methodological debt is even more dangerous, as it generates real social costs and jeopardizes institutional soundness. The DML framework proposed in this study serves as a repayment mechanism for this debt. By mathematically removing confounding influences, DML breaks the feedback loop and restores causal validity to the decision process, preventing the model-driven escalation of financial fragility.

5.3. A Systems-Dynamics Interpretation of Sleeping Dogs

The Sleeping Dog segment identified in this study is qualitatively distinct from ordinary non-responders in marketing contexts. These individuals function as latent fault lines within the financial system—potential triggers for instability whose behavioral mechanisms can be deeply understood through behavioral economics and complex systems theory.

According to the scarcity theory in behavioral economics, financial strain reduces cognitive bandwidth and induces myoptic decision-making, a phenomenon known as the “tunneling effect”. A credit-limit reduction delivers an acute scarcity shock to these customers. While rational-choice models assume that a reduced limit should simply result in reduced consumption, systemically vulnerable Sleeping Dog customers interpret the reduction as a threat to financial survival. In response, they may engage in extreme coping behaviors: resorting to high-interest loans, delaying payments on other obligations, or prioritizing immediate liquidity at the expense of long-term credit health. The DML model isolates precisely such individuals—those operating near “nonlinear tipping points” where small policy-induced shocks can generate disproportionately adverse outcomes.

From a systems-theoretic perspective, the default of a single borrower is not an isolated event. When a Sleeping Dog becomes delinquent, the consequences extend beyond the individual household to the financial institution’s asset quality. In today’s highly interconnected digital financial environment, information propagates rapidly through fintech platforms [24]. As a result, aggressive limit-reduction policies implemented by one institution may trigger market-wide credit tightening, creating ripple effects that escalate into broader credit contraction. Identifying and shielding Sleeping Dogs is, therefore, not merely a matter of firm-level risk management, but also constitutes a macroprudential imperative, essential for preventing contagion and preserving the stability of the financial system as a whole.

5.4. Bridging Theory and Practice: The Role of the DML-Then-Target Architecture

A major barrier preventing academically rigorous causal-inference models from adoption in business settings lies in their computational burden and operational complexity. The DML-then-Target architecture proposed in this study serves as a practical bridge between theoretical soundness and real-world deployability.

The DML model (the “teacher”) learns the underlying causal structure of the data, but its computational weight makes real-time deployment impractical. The Target Model (the “student”), in contrast, internalizes this causal knowledge in a lightweight form by learning from the CATE estimates produced by DML. While this process is analogous to knowledge distillation in deep learning, its goal here extends beyond mere model compression to “signal purification”. The empirical findings are notable: the Target Model consistently outperformed the original DML estimator in terms of hit ratio and the stability of the estimated CATE. This pattern indicates that the student model smooths out the statistical noise inherent in individual DML estimates and only extracts the structural patterns linking covariates to causal effects. In this sense, the two-stage architecture operates not only as a deployment convenience but also as a system-level filter that enhances external validity and model robustness.

One of the most innovative contributions of this study is the construction of a Causal Sandbox. Traditional A/B testing poses an ethical and economic dilemma: discovering the risk of a policy requires exposing real customers—potential Sleeping Dogs—to interventions that may trigger delinquency. However, as demonstrated earlier with the SHAP-Uplift Target Model’s suitability for off-policy evaluation (OPE), the Target Model produced by the DML-then-Target pipeline provides a reliable foundation for evaluating hypothetical policies. Using Inverse Propensity Weighting (IPW) or Doubly Robust (DR) estimators, decision-makers can obtain unbiased estimates of the expected return and risk of policies that have never been implemented in practice. This framework transforms financial decision-making from a “trial-and-error” paradigm into one based on “design and simulation”, representing an ideal realization of “model-driven” and “causally informed” decision processes.

5.5. Advancing Sustainable Finance and ESG Management

The implications of this study extend well beyond short-term profitability. The DML-then-Target framework is directly linked to broader goals of financial sustainability and Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). In particular, it offers several insights that align with ESG principles:

- (1)

- Economic Sustainability.

By avoiding unnecessary spending on “Sure-Things” customers and reallocating resources toward genuinely “Persuadables” segments, institutions can significantly enhance the efficiency of their marketing and risk-management operations. Such optimized resource allocation becomes a key competitive advantage that supports long-term financial stability and sustainable growth.

- (2)

- Social Value.

By identifying “Sleeping Dogs”, institutions can replace indiscriminate credit-limit reductions with more appropriate interventions—such as debt restructuring, counseling programs, or targeted support. This approach protects financially vulnerable segments and promotes “inclusive finance”. It also serves as a social safety net, preventing avoidable bankruptcies and enabling customers to remain productive participants in the economy over the long run.

- (3)

- Governance Transparency.

Causal models based on DML transform opaque risk scores into explicit rationales. By integrating OPE to simulate fairness-constrained strategies, this framework allows institutions to rigorously balance efficiency and equity. This approach ensures unbiased inputs, aligning with global regulatory expectations for Explainable AI (XAI) and strengthening institutional risk governance.

6. Conclusions: Causal Prescriptions as a Compass in an Age of Uncertainty

6.1. Summary and Scholarly Contributions

This study directly addresses the “methodological debt” accumulated in prediction-centric financial systems by establishing a rigorous framework for causal-prescriptive analytics. By integrating double machine learning (DML) with a novel knowledge-distillation architecture, we provide a systematic pathway for transforming observational data into actionable policy insights. The scholarly contributions and empirical findings are summarized as follows.

- (1)

- Methodological Transition: From Prediction to Causal Prescription: The transition to prescriptive targeting provides a robust foundation for institutional resource allocation, significantly improving substantive performance metrics over traditional correlational models. In marketing contexts (Case A), the framework successfully identified “Persuadable” segments, yielding a 0.55%p increase in the applied interest rate and KRW 1.9 billion in incremental loan volume, despite a 3.00%p reduction in offered discounts (Table 4). This validates that answering the prescriptive “what-if” question yields measurable gains in institutional efficiency.

- (2)

- Structural Insight Transfer via Knowledge Distillation: The distillation process effectively bridges the gap between complex econometric estimation and real-time industrial deployment. By utilizing unbiased CATE estimates as training labels, the Target Model smooths statistical noise into stable structural patterns. The 2023 credit data experiment (Case B) demonstrates this robustness: the distilled Target Model achieved a hit ratio of 42.13%, significantly outperforming the direct DML selection rate of 28.31% (Table 6). This confirms the framework’s superior generalization and stability under macroeconomic volatility.

- (3)

- The Causal Sandbox and Risk Mitigation: The framework establishes a “Causal Sandbox”—a counterfactual simulation environment for evaluating hypothetical interventions without customer exposure. In high-confounding credit environments, this sandbox proved indispensable for identifying “Sleeping Dogs”—customers whose delinquency risk escalates under limit-tightening policies. By pre-emptively excluding these segments, the framework ensures the development of sustainable policies that preserve institutional health while enhancing borrower resilience.

In summary, this research demonstrates that the methodological debt incurred by traditional ML practices can be effectively repaid. The proposed “Estimate → Predict & Evaluate” architecture bridges the gap between econometric rigor and industrial scalability, providing a sustainable and transparent paradigm for financial decision-making in an age of uncertainty.

6.2. Managerial Implications: Recommendations for Sustainable Business Models

For financial institutions, the findings of this study offer several actionable managerial implications.

- (1)

- First, investment priorities should shift from the quantity of data to the causal quality of data. Although institutions are allocating substantial resources to big data and AI initiatives, data that are not causally refined can accelerate misguided decisions. Financial firms must cultivate in-house causal inference capabilities within their data science units and revise model evaluation metrics from simple predictive accuracy to causal validity.

- (2)

- Second, customers should be viewed not as static entities but as adaptive agents embedded in a dynamic system. Customer behavior evolves in response to institutional policies. Particularly during periods of stress, policies that trigger latent vulnerabilities may ultimately return as financial losses. Supporting customers’ resilience through DML-based segmentation is, therefore, not merely a marketing strategy but a core component of risk management.

- (3)

- Third, the ethical accountability of algorithms must be implemented at a systemic level. Fairness and transparency [25] cannot be achieved by rhetoric alone. Methodologies such as DML—capable of mathematically controlling for bias and explicitly addressing confounders—are essential to prevent financial AI systems from reproducing social prejudice or disproportionately harming vulnerable populations.

6.3. Policy Recommendations and Societal Implications

From the perspective of regulatory authorities, the proposed framework can serve as a new toolkit for monitoring financial stability. Traditional stress tests primarily assess the impact of macroeconomic shocks. In contrast, causal modeling enables simulation of the micro- and macro-level ripple effects of specific institutional policies—such as credit line reductions or interest rate increases—on the household debt system. Moreover, as fintech platforms increasingly influence consumer behavior, regulators need analytical tools to monitor algorithmic impacts. The methodology presented in this study provides a theoretical foundation for developing guidelines to prevent “digital predation” and to ensure that algorithmic decisions in financial services remain aligned with consumer protection and market integrity.

6.4. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Despite the contributions of this study, several limitations remain and suggest avenues for future work.

- (1)

- First, there is the issue of unobserved confounders. While DML effectively removes bias stemming from observed covariates X, it cannot account for unmeasured factors—such as a borrower’s use of informal lending channels or psychological conditions—that may simultaneously influence treatment assignment and outcomes. Future research should incorporate sensitivity analysis methods, such as those proposed by Cinelli and Hazlett [26], including robustness values, to assess how strongly unobserved confounding would need to operate to overturn the study’s conclusions.

- (2)

- Second, the framework should be extended to dynamic treatment regimes (DTRs). This study analyzed only single-period interventions, but credit management is inherently a sequential decision-making process. Combining reinforcement learning with causal inference would enable the design of policy sequences that adapt to evolving customer states and optimize long-term payoffs.

- (3)

- Third, network effects merit deeper attention. Financial systems operate within borrower networks where one individual’s delinquency may propagate through supply chains or social ties. Incorporating interference effects into the modeling framework would allow for more realistic and fine-grained management of systemic risk.

6.5. Concluding Remarks

Data are often described as the “oil of the twenty-first century”, but just as unrefined crude oil can damage an engine, data lacking causal refinement can contaminate decision-making systems. In an era where uncertainty—financial crises, pandemics, and rapid technological disruptions—has become the norm, predictive models that merely replicate historical correlation patterns are no longer sufficient.

True prescriptive analytics does not end with forecasting what is likely to happen; it enables institutions to shape the future they wish to realize. The DML-then-Target framework proposed in this study serves as a lens that helps financial institutions escape the quagmire of “methodological debt” and confront the causal truths embedded in their data. In doing so, it can contribute to controlling risk, fostering co-growth with customers, and building a sustainable financial ecosystem. We have now reached a point where we must move beyond asking “What will happen?” and instead provide the most honest and rigorous answers that data and causal inference can offer to the question, “What should we do?”.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions and agreements with Samsung Card and PFCT.

Acknowledgments

The author extends their sincere gratitude to Joon (Tony) Huh for his invaluable assistance in facilitating access to the dataset and coordinating communication with the data provider. The author also expresses appreciation to the executive leadership of PFCT for their understanding regarding the academic utilization of the data, as communicated in advance. All data employed in this research were fully anonymized prior to analysis to ensure strict confidentiality and privacy compliance, and their usage was restricted exclusively to academic research purposes.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Devriendt, F.; Berrevoets, J.; Verbeke, W. Why you should stop predicting customer churn and start using uplift models. Inf. Sci. 2021, 548, 497–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascarza, E. Retention futility: Targeting high-risk customers might be ineffective. J. Mark. Res. 2018, 55, 80–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wager, S.; Athey, S. Estimation and inference of heterogeneous treatment effects using random forests. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2018, 113, 1228–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Jang, D.J.; Cho, C.K. Method and Device for Selecting Promotion Targets. Korean Patent No. 10-2414960, 27 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kiyohara, H.; Kishimoto, R.; Kawakami, K.; Kobayashi, K.; Nakata, K.; Saito, Y. Towards assessing and benchmarking risk—Return tradeoff of off-policy evaluation. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2311.18207. [Google Scholar]

- Chandak, Y.; Niekum, S.; da Silva, B.C.; Erik, E.; Kochenderfer, M.J.; Brunskill, E. Universal off-policy evaluation. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 34; Ranzato, M., Beygelzimer, A., Dauphin, Y., Liang, P.S., Vaughan, J.W., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 27475–27490. [Google Scholar]

- Pearl, J. Causality: Models, Reasoning, and Inference, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, D.B. Estimating causal effects of treatments in randomized and nonrandomized studies. J. Educ. Psychol. 1974, 66, 688–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, R.; Desbordes, R.; Eberhardt, M. The economic effects of “excessive” financial deepening. Oxf. Bull. Econ. Stat. 2025; Online First. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitsch, G.J.; Misra, S.; Zhang, W. Heterogeneous treatment effects and optimal targeting policy evaluation. Quant. Mark. Econ. 2024, 22, 115–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunzel, S.R.; Sekhon, J.S.; Bickel, P.J.; Yu, B. Metalearners for estimating heterogeneous treatment effects using machine learning. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 4156–4165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gubela, R.M.; Lessmann, S. Uplift modeling with value-driven evaluation metrics. Decis. Support. Syst. 2021, 150, 113648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoko, T.; Verster, T.; Dube, L. Comparative Analysis of Classical and Bayesian Optimisation Techniques: Impact on Model Performance and Interpretability in Credit Risk Modelling Using SHAP and PDPs. Data Sci. Financ. Econ. 2025, 5, 320–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.-I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30; Guyon, I., Luxburg, U.V., Bengio, S., Wallach, H., Fergus, R., Vishwanathan, S., Garnett, R., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 4765–4774. [Google Scholar]

- Chernozhukov, V.; Chetverikov, D.; Demirer, M.; Duflo, E.; Hansen, C.; Newey, W.; Robins, J. Double/debiased machine learning for treatment and structural parameters. Econom. J. 2018, 21, C1–C68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, H.-C.; Chen, J.-E. Exploring industry-distress effects on loan recovery: A double machine learning approach for quantiles. Econometrics 2023, 11, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, A.; Simonian, J. Deciphering the causal drivers of bond indexes: A double machine learning approach. J. Financ. Data Sci. 2025, 7, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ma, Y.; Zheng, J. How does structural monetary policy affect traditional bank lending? J. Asia Pac. Econ. 2025, 30, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, X.; Wager, S. Quasi-oracle estimation of heterogeneous treatment effects. Biometrika 2021, 108, 299–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huh, J.; Kim, J. Real-time risk management plan for revolving credit products based on new delinquency rates. J. Korean Innov. Soc. 2025, 20, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Huh, J.; Kim, J. Heterogeneous Causal Effects of Credit Policy in Confounded Financial Environments. Sejong University and Seoul National University, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2025. manuscript in preparation. [Google Scholar]

- Breiman, L. Statistical modeling: The two cultures. Stat. Sci. 2001, 16, 199–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sculley, D.; Holt, G.; Golovin, D.; Davydov, E.; Phillips, T.; Ebner, D.; Chaudhary, V.; Young, M.; Crespo, J.F.; Dennison, D. Hidden technical debt in machine learning systems. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 28; Cortes, C., Lawrence, N., Lee, D., Sugiyama, M., Garnett, R., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 2503–2511. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, S.; Qian, W.; Ren, Y.; Tsai, H.-T.; Yeung, B. The real impact of FinTech: Evidence from mobile payment technology. Manag. Sci. 2023, 69, 3230–3260. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, S. Fairness-Constrained Collections Policies: A Theoretical Model with Off-Policy Evaluation. Int. J. Sci. Technol. 2025, 16, 7902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinelli, C.; Hazlett, C. Making sense of sensitivity: Extending omitted variable bias. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B 2020, 82, 39–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.