Abstract

Artificial intelligence (AI) integration into human resource management (HRM) in recent years has revolutionized HRM processes, thus affecting employee job behavior and turnover intentions. While much of the existing research has focused on the decision-making capabilities of AI, how and when AI-driven HRM empathy influences employee behavior and performance remains unclear. This study draws on organizational commitment theory to investigate how AI-driven HRM empathy affects employee outcomes, including job and organizational engagement, job satisfaction, employee performance, and turnover intentions. A time-lagged survey design was employed to collect data from 359 employees in China. Structural equation modeling was used to analyze the relationships among the constructs. The findings revealed that AI-driven HRM empathy enhances employee engagement, which subsequently improves job satisfaction, enhances job performance, and decreases turnover intentions. This research advances understanding of how employees experience workplace technologies by highlighting the novel role of empathy as a human-like quality that is embedded in AI-enabled HRM systems. The findings suggest that organizations must develop targeted solutions for their AI-driven HRM workplace strategies. This research makes a valuable contribution to the developing knowledge about AI in human resources by demonstrating how AI-driven HRM empathy influences workplace participation and employee retention.

1. Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) is reshaping routine human resource management (HRM) practice by transforming how organizations recruit, develop, and retain talent patterns [1,2]. Across the HRM lifecycle, algorithmic screening tools, conversational recruitment bots, and predictive “people analytics” now inform day-to-day decisions [3]. Evidence links these systems to streamlined workflows, consistent data-driven judgments, and gains in job performance [4,5]. Therefore, organizations continue to expand AI-enabled HRM despite persistent concerns about displacement risks and ethical implications [6,7]. However, the scholarly conversation remains imbalanced: we know a great deal about adoption conditions and efficiency outcomes but far less about the relational experience employees have with AI in HRM settings, particularly whether and how perceived empathic qualities of these systems shape engagement, satisfaction, performance, and intentions to stay.

Research on AI at work largely falls into two streams. One investigates why organizations adopt AI by emphasizing technological readiness, structural arrangements, and external pressures [8,9,10]. The other probes what AI use does to employees by tracking outcomes, such as satisfaction, performance, and engagement [11,12]. Despite this progress, a notable blind spot remains: how employees experience empathy when interacting with AI-enabled HRM systems. This aspect matters amid active debate over whether machines can enact anything that resembles empathic behavior. Advocates contend that empathic features can nurture trust, psychological safety, and engagement [13,14]. Skeptics counter that “artificial empathy” may be performative or manipulative, thus inviting concerns about authenticity, transparency, and alienation [15,16,17]. Empathy is not merely a design capability but also a socioethical fault line that shapes how AI is applied in HRM.

Although AI tools, such as HRM chatbots and virtual assistants, are designed to mimic relational interaction, little is known about how employees interpret these systems as empathic or emotionally responsive. This gap matters because perceptions of empathy strongly shape trust, engagement, and satisfaction in human and digital exchanges [18]. Research has called for a deeper investigation into the ways AI affects engagement and organizational effectiveness [19]. At present, however, the HRM–AI literature lacks a comprehensive framework that connects AI capabilities to relational and emotional constructs that have traditionally been the domain of human managers. In this regard, AI-driven HRM empathy is conceptually distinct from managerial empathy: whereas the latter involves genuine recognition and response to employee emotions [20], the former refers to employees’ perceptions that AI systems are capable of simulating such empathic behaviors [21].

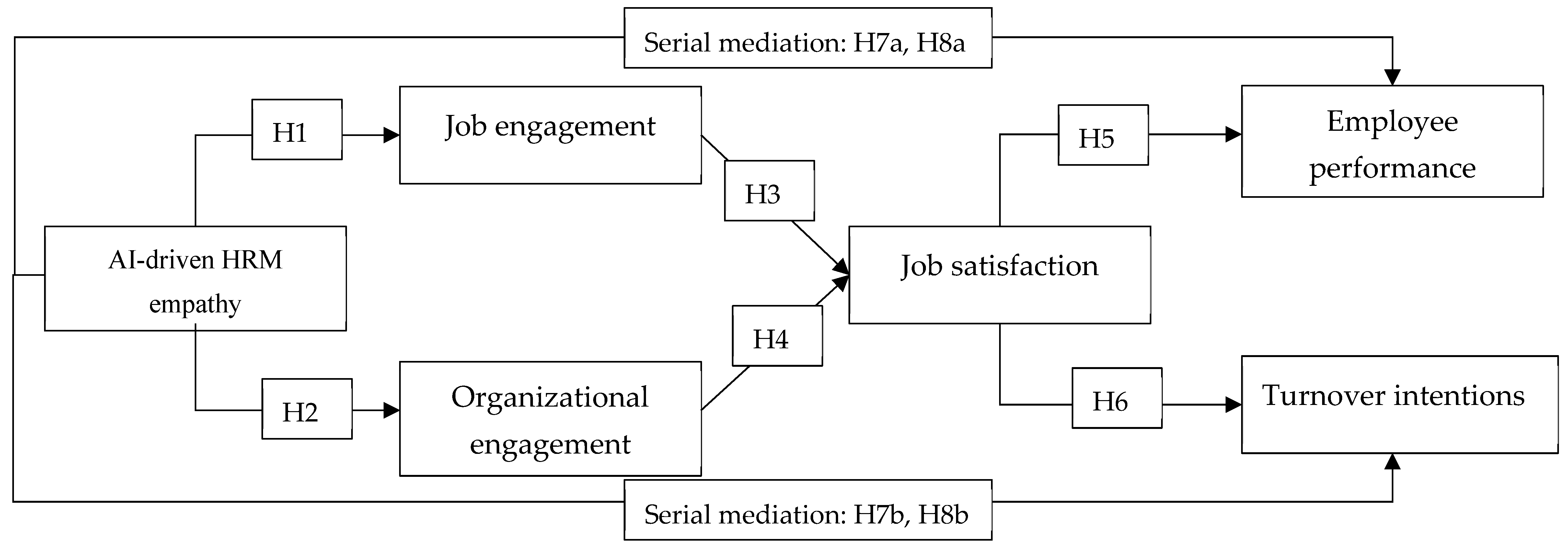

Our study addresses this limitation by drawing on organizational commitment theory [22] to investigate the relationship between AI-driven HRM empathy and employee engagement, job satisfaction, and consequent employee performance and turnover intentions (see Figure 1 for conceptual model). Job engagement refers to a positive, fulfilling, work-related state of mind in which an employee demonstrates vigor, dedication, and absorption [23]. Similarly, Saks et al. [24] defined organizational engagement as an individual’s engagement with the role, people, and their physical, cognitive, and emotional involvement during organizational role performances. AI-driven HRM empathy is the subject of the multidimensional investigation in this study to understand its effects on employee engagement, together with workplace experiences. Our study answers the following research question: How does AI-driven HRM empathy influence employee engagement, job satisfaction, performance, and turnover intention?

Figure 1.

Hypothesized model.

This study is grounded in organizational commitment theory to evaluate the perception of employees about AI-driven HRM empathy and how it contributes to key employee outcomes. Specifically, this work examines the pathways through which AI-driven HRM empathy shapes employee behavior and well-being. It makes a valuable contribution to organizational commitment theory by showing how AI-driven HRM empathy influences job satisfaction and reveals the methods that explain AI’s effect on workplace interactions. Moreover, this research provides concrete guidelines for enhancing AI adoption, which improves workforce involvement and enhances team loyalty while combating employee intentions to leave the organization.

The sections of the article are organized as follows: Section 2 presents the theoretical background and hypothesis development. Section 3 describes the methodology, including sampling, measures, and data collection. This section, discussing the methods, leads to Section 4, which presents the analysis and results. Finally, Section 5 provides a discussion of the results, implications for theory and practice, limitations, and future research directions.

2. Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

2.1. AI-Driven HRM Empathy

AI-driven HRM empathy is based on the broad empathy literature on social psychology, clinical psychology, and ethics [25]. Despite growing interest in AI applications in HRM, scholarly focus on empathy within this space remains relatively limited. Traditional HRM literature emphasizes empathy as a core competency that enhances leadership effectiveness, employee well-being, and interpersonal trust [20,26]. In recent years, researchers have begun to examine empathy in human–AI interaction by exploring whether artificial agents can simulate empathic behavior in organizational settings [10,13,27]. Empathy refers to the sense in interpersonal interactions, which involves understanding and sharing the emotional and cognitive states of the interaction partner [28]. On this basis, we define AI-driven HRM empathy as employees’ perception that an AI-driven HRM system has the capacity to detect, decode, and mimic their thoughts and emotions in an appropriate human-like manner. This concept builds on artificial empathy literature in human–machine interaction [10,21] and is contextualized within the domain of HRM to capture the relational dynamics between employees and AI-driven HRM. Although AI systems do not “feel” empathy, scholars have suggested that these systems can be designed to simulate empathic behaviors through affective computing, natural language processing, and adaptive response mechanisms [21]. Table 1 shows a concise literature review.

Table 1.

Concise literature review.

Although we acknowledge that AI empathy is not the same as that of humans, advanced technologies have enabled AI to simulate empathic behavior with increasing sophistication. For example, natural language processing is likely to help AI-driven HRM to interpret the semantic meaning and emotional tone of employee communications, thus enabling them to deliver contextually appropriate responses [14]. Moreover, AI tools enable system capabilities to recognize and respond empathically [13,21,29]. For example, AI-enabled chatbots can detect stress in employee language patterns and respond with encouragement or resources, while predictive “people analytics” platforms can anticipate disengagement and suggest targeted interventions [13,18,30]. Notably, AI simulates empathy not by experiencing emotions but by computationally modeling empathic behaviors that shape employees’ perceptions of being understood and supported.

While the adoption of AI in HRM by organizations has become a leading area of academic research (for a review, see [5]), prior studies have analyzed AI workplace implementation from a solitary standpoint by examining its automation capabilities [31,32] or the improvements it brings to the decision-making systems [33,34]. Various studies have examined either the intensity of AI utilization or its business-specific use within areas such as data processing, customer management, and operational optimization (e.g., [31,35]). However, research on AI-driven HRM empathy remains limited. Considering the critical role of empathy in the workplace [28] and the role that AI-driven HRM can play in shaping employees’ behavior and performance [7,36], the investigation of complete AI-driven HRM empathy requires a full assessment of how the diverse aspects of AI adoption affect job satisfaction and workplace involvement, and employee retention.

2.2. Organizational Commitment Theory

Organizational commitment offers a useful lens for understanding how employees respond to technology-mediated HRM. Becker [22] described commitment as the tendency to persist in courses of action once employees have made investments that would be lost if they withdrew. Subsequent work established commitment as a core indicator of employee attitudes and a reliable precursor of workplace behavior [37,38]. Porter et al. [39] emphasized its affective core, namely, the emotional bond between employees and their organizations. Meanwhile, the three-component model (affective, continuance, and normative) developed by Meyer and Allen [40] remains the dominant framework for theorizing why people stay engaged and contribute at work. As such, we focus on two routes, namely, affective commitment (emotional attachment/identification) and continuance commitment (perceived costs and foregone benefits of leaving), because they can be mapped directly onto our engagement–satisfaction mechanisms that shape employee outcomes.

Two broad streams have developed around this construct. One clarifies its conceptualization and measurements, while the other examines antecedents and consequences, such as job satisfaction, turnover intentions, trust, culture, and performance [41,42]. In parallel, information systems research shows that commitment shapes digital behaviors: committed users engage deeply, participate actively, and sustain usage over time [43,44]. Together, these literatures suggest that commitment is sensitive to cues in the work environment and in the technologies that structure employees’ daily experiences. Our hypotheses are consistent with this perspective because they treat job and organizational engagement as affective-commitment channels and job satisfaction as the evaluative appraisal through which commitment-related states translate into performance and reduced turnover intentions, thereby integrating the model into a single mechanism.

We argue that AI-driven HRM empathy, which pertains to employees’ perception that AI-driven HRM systems can recognize needs and respond in a human-like, supportive manner, functions as a salient environmental cue with implications for commitment-relevant states. When employees interpret AI-HRM interactions as empathic, they are likely to feel understood and supported, which strengthens affective bonds with the organization and reduces uncertainty around technology use. These perceptions should manifest proximally as high job and organizational engagement and downstream as increased job satisfaction, established pathways through which commitment translates into performance, and reduced turnover intentions.

Within this perspective, AI-driven HRM empathy operates through two linked mechanisms. First, it signals socioemotional support: empathic responses from AI-HRM increase psychological safety and convey that the organization values employees’ experiences. This pathway aligns with the affective commitment route and is reflected in high job and organizational engagement. Second, empathic AI-HRM reduces ambiguity about processes (e.g., recruitment, development, and appraisal) by stabilizing expectations and lowering perceived risks of loss associated with staying, thus being consistent with continuance commitment. As engagement rises, employees appraise their jobs favorably, which elevates satisfaction. Satisfied employees typically perform better and report weaker intentions to quit than those who are unsatisfied with their jobs. This study examines the effect of AI on employee behaviors and perceptions to improve the modern workplace understanding regarding how AI integration affects organizational commitment levels. This study uses organizational commitment theory as its grounding to propose the mechanisms (empathy → engagement → satisfaction → performance/turnover intentions) that underpin the direct and serial-mediation hypotheses.

2.3. AI-Driven HRM Empathy and Employee Engagement

Research defines employee engagement as a distinct multidimensional concept that includes mental aspects, emotional states, and behavioral indicators that are related to work performance outcomes [45,46]. Employees generally perform their task responsibilities and also engage in extra role behaviors in support of their organization [47]. In this view, employee engagement is divided into two distinct dimensions, namely, job engagement and organizational engagement, because it reflects the psychological commitment level for these job positions. Within organizational commitment theory, engagement is treated as an affective commitment-relevant state through which supportive organizational cues are translated into role investment and contribution [42,45]. Multiple essential elements that shape employee engagement have been identified in academic studies, including job crafting, job resources, and hindrances, as well as job demands along with intraorganizational social connections and social capital; job satisfaction has also been proven important [48,49]. Although studies have extensively explored multiple engagement influencers, they have not thoroughly examined the effects of AI-driven HRM empathy on workplace engagement metrics. According to organizational commitment theory, empathic AI-HRM signals socioemotional support and value congruence, which should strengthen employees’ affective attachment and elevate job-focused and organization-focused engagements. The discovery of positive connections between AI-driven HRM empathy and employee engagement can explain how AI affects workplace environments and employee dedication. This explanation will help organizations use their knowledge of this connection to maximize the benefits of AI for boosting employee engagement.

Uses and gratifications theory [50] demonstrates how people employ modern technology to address their requirements during active usage. The degree to which organizational workers understand AI determines their approach toward managing AI-driven tools in their professional duties and personal productivity tasks. Workplace operations become increasingly efficient when AI integration offers process optimization and assists with decisions while generating data-backed, data-driven insights for collaboration [51]. AI also strengthens workplace connectivity because it allows efficient knowledge distribution, customized educational methods, and flexible support procedures that benefit employee workflow and organizational targets. Furthermore, employee engagement improves through AI-driven HRM empathy because employees gain increased access to resources and communication functions efficiently. Tortorella et al. [52] demonstrated how AI analytics and automation increase employee engagement. Meanwhile, Moin et al. [53] demonstrated AI’s role in building organizational commitment. Organizations that plan to implement AI-driven HRM empathy programs can improve job engagement and organizational engagement. Based on these insights, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1.

AI-driven HRM empathy positively affects employees’ job engagement.

H2.

AI-driven HRM empathy positively affects employees’ organizational engagement.

2.4. Employee Engagement and Job Satisfaction

Employee engagement and job satisfaction are considered essential elements that impact employee well-being and achievement levels within the workplace [54,55]. Employee engagement describes the emotional and behavioral job-related involvement that workers exhibit through their work-driven commitment and psychological presence combined with enthusiasm [23,56]. The definition of job satisfaction indicates how workers evaluate their workplace experience through the assessment of intrinsic and extrinsic work elements, from workplace conditions to compensation opportunities and colleagues’ relationships [57,58]. Employee engagement functions as a dynamic workspace condition that affects employees’ work approach, while job satisfaction emerges as a workplace evaluation outcome from numerous enduring workplace factors. Studies have investigated the connection between employee engagement and job satisfaction and consistently shown that these variables strongly relate to each other. Employees who demonstrate engagement through enthusiasm and dedication and work with vigor create a strong perception of job fulfillment and satisfaction [59]. Employee engagement levels directly influence reported job satisfaction [60] because of three essential factors, namely, workplace support, autonomy, and psychological meaningfulness.

The perception that work produces meaningful and rewarding results leads employees to become satisfied with their job roles [58]. The job demands–resources model [61] functions as a theory to understand this phenomenon. Moreover, it depicts how job resources, including social support, skill variety, and autonomy, develop employee engagement, which drives job satisfaction. The engagement of employees leads them toward positive emotions, together with reduced stress and increased organizational attachment, which results in high job satisfaction [62]. Prior research [63] established that engaged employees demonstrate improved stress resilience, which enables them to sustain a favorable job perspective regardless of challenging work conditions. Given the extensive empirical evidence that supports the relationship between engagement and job satisfaction, we propose the following hypotheses:

H3.

Job engagement positively affects employees’ job satisfaction.

H4.

Organizational engagement positively affects employees’ job satisfaction.

2.5. Job Satisfaction, Employee Performance, and Turnover Intentions

Employee performance comprises two distinct aspects, namely, task performance, which represents job duty achievement, and contextual performance, which consists of team-based behaviors and organizational citizenship actions [64]. Job satisfaction creates employees who demonstrate high motivation levels along with engagement and productivity, which result in improved individual and organizational outcomes [65,66]. Organization commitment theory suggests that favorable technological work conditions for staff members bolster employees’ dedication and effort, along with superior performance results [67]. Research findings indicate that job satisfaction generates positive relationships between employee performance, which directly and subjectively affects results, such as sales, productivity, and assessments from supervisors [68].

Turnover intention refers to the opportunity that employees take to leave their organizational setting [69]. Employee dissatisfaction triggers them to look for different positions and serves as a primary turning point for workplace abandonment [70,71]. Hobfoll [72] suggested that workers who are dissatisfied with their jobs perceive a deprivation of their resources, which leads to thoughts about employment relocation. The dissatisfaction levels in organizations lead to increased employee turnover, which increases recruiting expenses and decreases workplace performance [73]. Staff members who feel satisfied will develop a strong commitment, which decreases their potential to leave their organization [74]. Thus, we hypothesize the following:

H5.

Job satisfaction positively influences employee performance.

H6.

Job satisfaction negatively influences turnover intentions.

2.6. Serial Mediation Effects

Consistent with the organizational commitment logic, we build on the preceding hypotheses and propose a serial mediation from AI-driven HRM empathy to employee outcomes. When AI-driven HR practices are perceived as empathetic, responsive, respectful, and supportive, employees tend to feel engaged with their work and their organization. Heightened engagement fosters job satisfaction, which is an evaluative state that channels positive energy into outcomes. Subsequently, satisfied employees improve their performance and have a decreased inclination to quit. Therefore, we treat engagement to satisfaction as the central conduit through which AI-driven HRM empathy influences downstream behaviors. We propose two parallel serial pathways that reflect the foci of engagement: a job-focused chain (job engagement → job satisfaction) and an organizational-focused chain (organizational engagement → job satisfaction). AI-HRM empathy influences employee performance and turnover intentions through these two pathways. Thus, we propose the following hypotheses:

H7a.

AI-driven HRM empathy has a positive indirect effect on employee performance through job engagement and job satisfaction.

H7b.

AI-driven HRM empathy has a negative indirect effect on turnover intentions through job engagement and then job satisfaction.

H8a.

AI-driven HRM empathy has a positive indirect effect on performance through organizational engagement and job satisfaction.

H8b.

AI-driven HRM empathy has a negative indirect effect on turnover intentions through organizational engagement and job satisfaction.

3. Research Methods

3.1. Data Collection

A structured survey questionnaire was designed and distributed among full-time employees in mainland China to validate the proposed model empirically. The sample from China was selected for the following reasons. First, Chinese organizations are rapidly adopting AI across departments, including HRM, where AI is increasingly being applied in recruitment, training, and performance evaluation. Second, China has a collective and high power distance culture, which shapes how employees interpret workplace experiences [75]. Prior work has suggested that individuals in such contexts may be more sensitive to empathic behavior than those in individualistic cultures [76]. Therefore, Chinese organizations provide an appropriate sample to test the influence of AI-driven HRM empathy on employees. In this study, eligibility was restricted to employees who use AI applications. Initially, human resource managers were contacted to provide a brief explanation of the purpose of the research. Then, HRM officials helped us contact employees to explain the purpose of the study. We emphasized confidentiality to the employees and distributed the survey link by e-mail and WeChat.

We employed validated measures from the literature to develop a questionnaire survey. The instrument was translated from English to Chinese and back-translated by bilingual experts [77]. Prior research has suggested that the temporal separation of the measurements of variables mitigates the possibility of common method bias [78]. Therefore, we collected data in three phases to avoid such bias [79]. In the first phase, employees reported their perception of AI-driven HRM empathy along with demographic information. Two weeks after the first phase, employees reported their responses on job engagement, organizational engagement, and job satisfaction. In the third phase, which was one month after phase one, the employees reported their turnover intentions, while the leaders reported the performance of their subordinates. In phase one, we shared the questionnaire with 540 employees. Subsequently, we received 410 responses. In phase two, among 410 employees, 395 provided their responses. In phase three, we received responses from 371 employees. Moreover, we received the performance ratings from the respondents’ direct supervisors. After eliminating 12 incomplete responses, 359 usable responses were retained for analysis, which resulted in a response rate of 66.5%. We assessed the nonresponse bias using the chi-square difference test of randomly selected key variables. Results suggest no significant difference between the first 25% and the final 25% of the respondents. Thus, the results suggest that our data were not affected by nonresponse bias.

The final sample captured a broad industrial cross-section: manufacturing (15%), professional services (28.7%), information technology (23.7%), hospitality and tourism (9.5%), and other sectors (23.1%). Work tenure was varied: 21.2% were less than 5 years, 51% were 6 to 10 years, 12% were 10 to 15 years, and 15.9% were above 15 years.

3.2. Measures

We followed prior studies [80] and used well-established multi-item scales. AI-driven HRM empathy was measured using three items that had been adapted from de Kervenoael, Hasan, Schwob, and Goh [18] and one item that had been adapted from Juquelier, Poncin, and Hazée [13]. We drew items from de Kervenoael and colleagues because their empathy indicators in human–robot service encounters capture the same individualized responsiveness we theorized in HRM, sensitivity to users’ needs, personalized attention, and convenient availability. Meanwhile, the single items from Juquelier and colleagues provided an affect-recognition indicator to cover the capacity of an AI-driven HRM system to read users’ emotions. As such, these items provided a well-aligned measure of AI-driven HRM empathy to our conceptualization. The scale was originally developed for hospitality-based human–robot interactions. The hospitality domain was selected because it emphasizes relational quality, emotional responsiveness, and trust, dimensions that are equally critical in HRM contexts where AI tools increasingly mediate employee interactions. Contextual appropriateness was ensured by revising the wording of the items to capture perceived emotional responsiveness, understanding, and communication quality in AI-HRM interactions. Although we adapted the construct, namely, perceived empathic responsiveness of AI tools, to AI-driven HRM empathy, it remained conceptually aligned. Moreover, AI-driven HRM empathy simulates human-like understanding and care, which is similar to that of the original measure. Nevertheless, the scale demonstrated acceptable reliability statistics, thereby validating the appropriateness of adapting the measure.

Items to measure employee job engagement and organizational engagement were adopted from Zhang, Ma, Xu, and Xu [67] based on Saks [60]. Job engagement was measured using three items, while organizational engagement was measured using four items. This dimension was validated in the information systems field by Zhang, Ma, Xu, and Xu [67]. Employee job satisfaction was measured with three items adapted from Moqbel et al. [81]. Employee performance used four items that were taken from Van Beurden et al. [82]. Additionally, employee turnover intentions relied on three items from Boswell et al. [83]. Items are presented in Appendix A below. Notably, all items employed a seven-point Likert continuum (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). We followed prior research and used the demographic information of respondents as control variables in our model. Specifically, we used employee education, job tenure, and industry type as controls in our analysis.

4. Analysis and Results

4.1. Analytical Approach

We tested our hypothesized model with covariance-based structural equation modeling (CB-SEM) in AMOS v24.0. CB-SEM allows the measurement and structural components of the model to be evaluated coherently in a theory-testing framework [84]. As such, this method provided us with a validated approach to test our theory-based model. Consistent with prior studies [85,86], we applied a two-step procedure: validating the measurement model via CFA and then estimating the structural model. Our constructs were reflective latent variables. Furthermore, our aim was to test the sequential (serial) mediation that had been specified by the theory. As such, we estimated simultaneous direct paths and path-specific indirect effects using bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals (5000 resamples), which provided well-calibrated inferences for mediation in SEM [87].

4.2. Measurement Model

We assessed the measurement model by performing a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). The construct reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity were also examined (see Table 2). The CFA results indicated that data provided reasonable fit indices (χ2 = 193.32, df = 174, CFI = 0.99, SRMR = 0.04, and RMSEA = 0.02) [88]. First, reliability was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE). All Cronbach’s alpha values ranged between 0.80 and 0.85, thus exceeding the acceptable threshold of 0.7. CR values ranged from 0.80 to 0.85, while AVE values ranged from 0.51 to 0.66. All values surpassed the required thresholds of 0.70 and 0.50, respectively, thus indicating strong internal consistency and convergent validity [89]. Notably, the value of AVE for AI-driven HRM empathy was 0.51, which was slightly above the recommended threshold of 0.50. Although this value was marginal, it was considered acceptable given that the construct also demonstrated strong CR (0.83). Meanwhile, all standardized factor loadings exceeded 0.60. These results suggested adequate convergent validity. Therefore, the marginal AVE did not compromise the interpretation of this construct within our structural model.

Table 2.

Results of the confirmatory factor analysis test.

Factor loadings for individual items were examined to assess convergent validity further. All loadings were above the 0.60 threshold (see Table 3). Discriminant validity was established using the approach of comparing the square roots of AVEs with correlations. Results revealed that the square root of each construct’s AVE was greater than its correlations with other constructs. These results confirmed that the measurement model demonstrated strong reliability and validity (see Table 4).

Table 3.

Factor cross-loadings.

Table 4.

Correlations matrix.

4.3. Structural Model

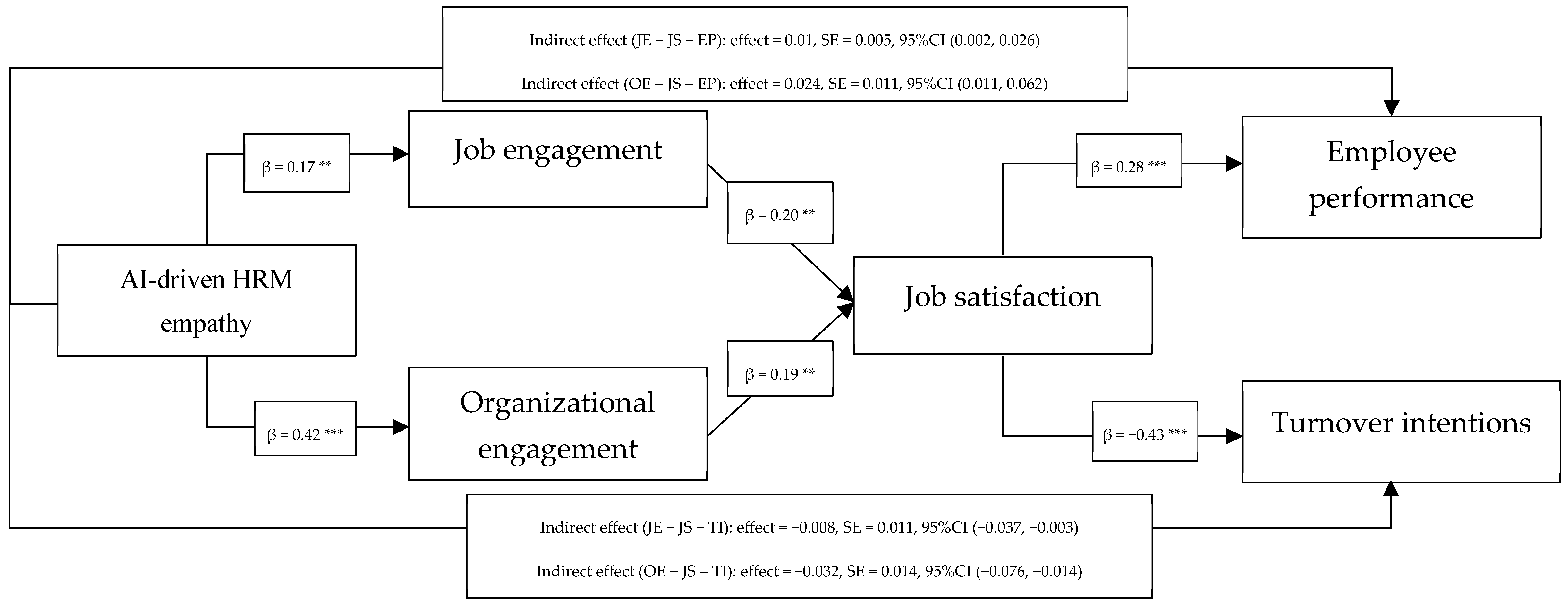

The analysis of the structural model provided acceptable fit indices (χ2 = 291.163, df = 183, CFI = 0.96, SRMR = 0.10, and RMSEA = 0.04) [88]. The results (Figure 2) revealed that AI-driven HRM empathy positively influenced employees’ job engagement (β = 0.17, t = 2.77, p < 0.01) and organizational engagement (β = 0.42, t = 6.91, p < 0.001), thus supporting H1 and H2. Job engagement significantly influenced job satisfaction (β = 0.20, t = 4.21, p < 0.001), while organizational engagement also had a strong positive effect on job satisfaction (β = 0.19, t = 4.26, p < 0.001), thereby validating H3 and H4.

Figure 2.

Results of hypothesis testing.** = p < 0.01, *** = p < 0.001.

Job satisfaction showed a significantly positive impact on employee performance (β = 0.28, t = 5.21, p < 0.001) and a significantly negative effect on turnover intentions (β = −0.43, t = −5.45, p < 0.001). Therefore, H5 and H6 were confirmed.

Moreover, the results indicated that all control variables (employee education, job tenure, and industry type) had an insignificant relationship with both outcomes. However, industry type had a significantly negative effect on turnover intentions (β = −0.13, t = −1.59, p < 0.05). These results suggested that control variables had minimal influence on our outcomes.

4.4. Mediating Effects

Finally, we tested the serial mediation effects using the SEM approach. AMOS 24.0 was used with a 95% confidence interval (CI) and 5000 bootstrap samples. The results indicated mediation in several paths. Job engagement and job satisfaction serially mediated the relationship between AI-driven HRM empathy and job performance. The CIs of the indirect effects did not include zero [Indirect effect = 0.01, SE = 0.005, 95% CI (0.002, 0.026)], thus supporting H7a. Additionally, organizational engagement and job satisfaction serially mediated the relationship between AI-driven HRM empathy and job performance. The CIs of the indirect effects did not include zero [Indirect effect = 0.024, SE = 0.011, 95% CI (0.011, 0.062)], thus confirming H8a.

Moreover, results demonstrated that job engagement and job satisfaction serially mediated the effect of AI-driven HRM empathy on employee turnover intentions [indirect effect = −0.008, SE = 0.011, 95% CI (−0.037, −0.003)]. These results provided support for H7b. In addition, we found that organizational engagement and job satisfaction mediated the relationship between AI-driven HRM empathy and employee turnover intentions [indirect effect = −0.032, SE = 0.014, 95% CI (−0.076, −0.014)], thus confirming H8b.

5. Discussion and Implications

5.1. Discussion of Results

The research explored the relationship of AI-driven HRM empathy with employees’ job satisfaction, work performance, and turnover intentions. The research analyzed AI-driven HRM empathy through its effects on employee engagement, which specifically incorporates job engagement and organizational engagement. The study demonstrated that AI-driven HRM empathy in the workforce leads to enhanced employee engagement through improved access to information, along with increased decision-making capabilities and efficient task performance. Job engagement, together with organizational engagement, directly affects the levels of job satisfaction among employees. High job satisfaction fosters employees who demonstrate excellent work performance while having a decreased likelihood of leaving or switching jobs. The findings emphasize how AI-driven HRM empathy can mold worker attitudes through positive behavioral changes, thus promoting strong employee dedication at work.

Based on H1 and H2, our study found that AI-driven HRM empathy serves as a critical factor that enhances job engagement and organizational engagement among employees. These findings align with those of prior research [52], which has demonstrated that AI applications positively impact the emotional, physical, and cognitive dimensions of engagement when they are integrated in human-centered environments, such as lean organizations. Multiple studies have shown that understanding technology leads employees to enhance their work commitment [90,91] while improving their organizational engagement [92]. These findings suggest that AI-driven HRM empathy develops employee trust in AI technologies; moreover, employees improve their work efficiency and engagement in their daily activities [13].

Based on H3 and H4, the results exhibited support for the positive role of organization and job engagement on job satisfaction. These findings align with prior research that investigated the role of engagement on job satisfaction [60]. Finally, the findings of our analysis indicate that job satisfaction is positively related to job performance and decreases turnover intentions. These findings confirm prior research in organizational behavior and human resource management that suggests that employee job satisfaction leads to positive employee behaviors [93,94]. One important finding is the slightly small but significantly indirect effect of AI-driven HRM empathy on employee performance via job engagement and job satisfaction. However, in organizational contexts, modest improvements in employee engagement and performance can scale meaningfully when applied across large workforces or high-cost performance domains. These small yet reliable paths indicate that AI-driven HRM empathy contributes to incremental but measurable improvements in employee outcomes over time.

5.2. Theoretical Implications

This study theoretically contributes in many ways to the current literature on HRM and AI. First, this work advances the literature on HRM and AI by introducing AI-driven HRM empathy as a critical mechanism that explains how employees’ perceptions of technology shape their work-related outcomes. We draw on organizational commitment theory to show that employees’ perceptions of empathic qualities in AI-enabled HRM systems influence them through dual pathways, thereby enhancing engagement and satisfaction while reducing turnover intentions. AI-driven HRM empathy increases employees’ access to meaningful resources and trust in workplace technologies, which subsequently fosters high engagement and job satisfaction. These findings extend the existing HRM research by shifting the focus from AI’s operational efficiency toward its relational and psychological impact on employees. Thus, the study provides a novel explanation for why and how employees react positively to AI adoption, thereby broadening the theoretical boundaries of digital transformation research in HRM.

Second, this study advances organizational commitment theory by positioning AI-driven HRM empathy as a novel antecedent of commitment. When employees perceive AI systems as empathic, they experience high levels of psychological safety, trust, and satisfaction, which foster affective commitment through strong emotional bonds with the organization. At the same time, perceptions of empathic AI reduce uncertainty and enhance perceived organizational support, thereby contributing to continuance commitment by strengthening employees’ sense of stability and lowering turnover intentions. In this way, AI-driven empathy extends organizational commitment theory into technology-mediated contexts by demonstrating that digital systems, not only human managers, can shape employees’ attachment to their organizations.

Lastly, this research helps expand the current knowledge about workplace technology use through its detection of how employees’ understanding of AI affects their work outcomes and their desire to leave the organization. Most previous research about AI has focused on technical and operational benefits [95], whereas the psychological and behavioral effects on employees have received limited research attention. Data reveal that employee performance improves when employees understand AI because their work process efficiency increases, while mental workload decreases, and their decision quality improves. Workers who perceive AI empathy generally maintain high job security along with promising career advancement, which reduces their intentions to leave their current organization. Workplace turnover risks become elevated for employees whose understanding of AI is basic because they experience concerns about job elimination and outdated skills [96]. The study expands AI workplace research through its assessment of employee retention and productivity by integrating AI-driven HRM empathy knowledge.

5.3. Practical Implications

This study offers some key practical implications for managers and organizations. First, AI integration success requires organizations to pursue training and adequate empathy programs for their employees to develop effective AI usage skills. Beyond generic literacy programs, organizations can design structured AI training workshops that are tailored to HRM applications. For example, hands-on learning should start with the very tools that employees use day to day, practical sessions with recruiting platforms that are powered by machine learning, HR chat assistants, and performance management tools. These tools can be paired with short modules on ethics and governance, bias, explainability, accountability, and privacy to build trust and fluency. Additionally, adoption can be facilitated by mixing scenario-based simulations, short “AI for HR” boot camps, and peer mentoring. These solutions can help people practice real workflows in a low-risk setting.

Second, our results indicate that AI can raise job satisfaction by taking repetitive work off employees’ plates, thus freeing them to focus on judgment-heavy tasks. Automation streamlines operations while enabling personalized workflows and work–life balance. Analytics can track sentiment and satisfaction trends so leaders can spot issues early. Organizations can also conduct micro-surveys to monitor perceptions of AI tools and use text analysis on anonymized feedback to surface emerging concerns and inform timely interventions.

Finally, when AI adoption leads to job insecurity in the workplace, workers may leave their jobs unless organizations take appropriate steps to manage the situation. Therefore, organizations should implement AI technology as a performance-enhancing tool for human labor rather than as a technology for job replacement. Communicating AI roles clearly and providing workers with chances to enhance their skills can build trust and decrease the employees’ safety concerns regarding job termination. Organizations can use AI-powered career development systems to help workers discover professional advancement paths and acquire new abilities. This support presents opportunities for internal career progression, which produces committed workers and minimizes employee turnover.

5.4. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Despite the several theoretical and practical contributions, this research contains various limitations that generate possibilities for upcoming academic investigations. The research mainly examines how employees’ empathy about AI influences their engagement with work, satisfaction level, work performance, and willingness to stay or switch jobs. AI-driven HRM empathy serves as an insufficient measure to understand AI implementation complexities that occur in workplaces. Additional factors, including employee attitudes toward AI self-efficacy and organizational AI readiness, need evaluation because they possibly influence workplace transformations that are stimulated by AI systems.

We also acknowledge the potential downsides of AI-driven empathy, including risks of overreliance on technology for relational functions and employee concerns about data privacy in emotionally responsive systems. These limitations point to the importance of balancing AI-enabled empathy with transparent communication and human oversight in HRM practices. As such, we invite scholars to advance the theory and empirical validation of AI-driven empathy and its associated risks to improve our understanding of this concept and its potential concerns.

While the study captured responses from diverse sectors, we have included industry type as a control variable in the structural model. The lack of significant influence suggests that the relationships observed (e.g., between AI-driven HRM empathy and performance outcomes) are consistent across sectors. Nevertheless, this consistency supports the generalizability of the findings within the sampled population. Nonetheless, we acknowledge that sector-specific dynamics may exist. We recommend future research to explore these distinctions through comparative or multigroup analysis.

Another limitation of this study is data collection. We collected data at three time points, which provided a remedy against common method bias. Future research should consider longitudinal or experimental designs to examine how perceptions of AI-driven HRM empathy develop over time and influence employee attitudes and behaviors. In addition, we collected data from Chinese employees. Chinese culture is collectivistic and characterized by high power distance. In this culture, employees’ response to empathy may differ from those in Western cultures. For example, individuals in cultures with high power distance may be receptive to directive or authoritative AI systems. They may interpret empathic behavior differently from those in cultures with low power distance. We suggest that the results be cautiously generalized to other cultural contexts. We invite future scholars to replicate our model in other countries to reinforce the robustness of the findings on the effects of AI-driven HRM empathy.

Although the bootstrapping CIs confirm statistically reliable serial mediation, the indirect effects that have been identified are relatively small (e.g., 0.024). Accordingly, these findings should be interpreted with caution because they reflect subtle rather than substantial practical implications. Although small indirect effects may accumulate significance over time or within large organizational contexts, their magnitude should not be overstated. We invite future researchers to evaluate other mediating factors that may have significant effects and explore conditions under which these indirect effects may be strengthened, such as in high-uncertainty environments.

Author Contributions

A.A. conceptualization, writing main manuscript; A.H.P. methods and analysis. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number W2433182.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of our institute. Informed consent was obtained from all employees who participated in this study.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data generated and used in this study are available from the corresponding author upon a reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the use of ChatGPT Version GPT-40 to avoid grammatical issues.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Measurement Scales

| Variable | Item | |

| AI-driven HRM empathy [13,18] | AIDH1 | AI systems in HRM usually understand my specific needs. |

| AIDH2 | AI systems in HRM usually give me individualized attention. | |

| AIDH3 | AI systems in HRM are available whenever it is convenient for me. | |

| AIDH4 | AI systems in HRM usually recognize my emotions. | |

| Job engagement [60] | JE1 | I really “throw” myself into my job. |

| JE2 | Sometimes I am so into my job that I lose track of time. | |

| JE3 | This job is all-consuming; I am totally into it. | |

| Organizational engagement [60] | OE1 | Being a member of this organization is very captivating. |

| OE2 | One of the most exciting things for me is getting involved with things happening in this organization. | |

| OE3 | Being a member of this organization makes me come “alive.” | |

| OE4 | Being a member of this organization is exhilarating for me. | |

| Job Satisfaction [81] | JS1 | I am very satisfied with my current job. |

| JS2 | My present job gives me internal satisfaction. | |

| JS3 | My job gives me a sense of fulfillment. | |

| Turnover intentions [83] | TI1 | I often think about quitting my job. |

| TI2 | I will probably look for a new job in the next year. | |

| TI3 | I don’t think about quitting my job. (R) | |

| Job performance [82] | JP1 | This employee carried out the core parts of the job well. |

| JP2 | This employee initiated better ways of doing the tasks. | |

| JP3 | This employee adapted well to changes in tasks. | |

| JP4 | The overall job performance of the employee met expectations. |

References

- Bankins, S.; Ocampo, A.C.; Marrone, M.; Restubog, S.L.D.; Woo, S.E. A multilevel review of artificial intelligence in organizations: Implications for organizational behavior research and practice. J. Organ. Behav. 2024, 45, 159–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prikshat, V.; Islam, M.; Patel, P.; Malik, A.; Budhwar, P.; Gupta, S. AI-Augmented HRM: Literature review and a proposed multilevel framework for future research. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 193, 122645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, H.; Chu, L.X.; Shipton, H. How and when AI-driven HRM promotes employee resilience and adaptive performance: A self-determination theory. J. Bus. Res. 2025, 192, 115279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, M.; Seringa, J.; Silvestre, T.; Magalhães, T. Use of artificial intelligence tools in supporting decision-making in hospital management. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prikshat, V.; Malik, A.; Budhwar, P. AI-augmented HRM: Antecedents, assimilation and multilevel consequences. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2023, 33, 100860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rožman, M.; Tominc, P.; Milfelner, B. Maximizing employee engagement through artificial intelligent organizational culture in the context of leadership and training of employees: Testing linear and non-linear relationships. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2023, 10, 2248732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, Z.; Liu, M.T.; Chark, R.; Zeng, S.; Song, X. How AI adoption in human resource management practices can enhance tourism employees’ organizational commitment. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2025, 63, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Jiang, M.; Jia, F.; Liu, G. Artificial intelligence adoption in business-to-business marketing: Toward a conceptual framework. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2022, 37, 1025–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uren, V.; Edwards, J.S. Technology readiness and the organizational journey towards AI adoption: An empirical study. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2023, 68, 102588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelau, C.; Dabija, D.-C.; Ene, I. What makes an AI device human-like? The role of interaction quality, empathy and perceived psychological anthropomorphic characteristics in the acceptance of artificial intelligence in the service industry. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 122, 106855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamba, S.F. Impact of artificial intelligence assimilation on firm performance: The mediating effects of organizational agility and customer agility. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2022, 67, 102544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Xue, X.; Wang, N.; Yin, X.; Tariq, H. The interplay of team-level leader-member exchange and artificial intelligence on information systems development team performance: A mediated moderation perspective. Int. J. Manag. Proj. Bus. 2024; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juquelier, A.; Poncin, I.; Hazée, S. Empathic chatbots: A double-edged sword in customer experiences. J. Bus. Res. 2025, 188, 115074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorin, V.; Brin, D.; Barash, Y.; Konen, E.; Charney, A.; Nadkarni, G.; Klang, E. Large language models and empathy: Systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2024, 26, e52597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Leach, R. The role of digitally-enabled employee voice in fostering positive change and affective commitment in centralized organizations. Commun. Monogr. 2020, 87, 425–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B. In AI we trust? Effects of agency locus and transparency on uncertainty reduction in human–AI interaction. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 2021, 26, 384–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montemayor, C.; Halpern, J.; Fairweather, A. In principle obstacles for empathic AI: Why we can’t replace human empathy in healthcare. AI Soc. 2022, 37, 1353–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Kervenoael, R.; Hasan, R.; Schwob, A.; Goh, E. Leveraging human-robot interaction in hospitality services: Incorporating the role of perceived value, empathy, and information sharing into visitors’ intentions to use social robots. Tour. Manag. 2020, 78, 104042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soulami, M.; Benchekroun, S.; Galiulina, A. Exploring how AI adoption in the workplace affects employees: A bibliometric and systematic review. Front. Artif. Intell. 2024, 7, 1473872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holt, S.; Marques, J. Empathy in leadership: Appropriate or misplaced? An empirical study on a topic that is asking for attention. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 105, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu-Thompkins, Y.; Okazaki, S.; Li, H. Artificial empathy in marketing interactions: Bridging the human-AI gap in affective and social customer experience. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2022, 50, 1198–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, H.S. Notes on the concept of commitment. Am. J. Sociol. 1960, 66, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Salanova, M.; González-Romá, V.; Bakker, A.B. The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. J. Happiness Stud. 2002, 3, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saks, A.M.; Gruman, J.A.; Zhang, Q. Organization engagement: A review and comparison to job engagement. J. Organ. Eff. People Perform. 2022, 9, 20–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, N.; Fabes, R.A. Empathy: Conceptualization, measurement, and relation to prosocial behavior. Motiv. Emot. 1990, 14, 131–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalra, A.; Briggs, E.; Schrock, W. Exploring the synergistic role of ethical leadership and sales control systems on salesperson social media use and sales performance. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 154, 113344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.; Park, J.; Ye, S. How AI enhances employee service innovation in retail: Social exchange theory perspectives and the impact of AI adaptability. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2025, 84, 104207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieseke, J.; Geigenmüller, A.; Kraus, F. On the role of empathy in customer-employee interactions. J. Serv. Res. 2012, 15, 316–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.B.; Hur, H.J. What makes people feel empathy for AI chatbots? Assessing the role of competence and warmth. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Interact. 2024, 40, 4674–4687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, I.; Pereira, A.; Mascarenhas, S.; Martinho, C.; Prada, R.; Paiva, A. The influence of empathy in human–robot relations. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2013, 71, 250–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babashahi, L.; Barbosa, C.E.; Lima, Y.; Lyra, A.; Salazar, H.; Argôlo, M.; Almeida, M.A.d.; Souza, J.M.d. AI in the workplace: A systematic review of skill transformation in the industry. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego, A.; Kurer, T. Automation, digitalization, and artificial intelligence in the workplace: Implications for political behavior. Annu. Rev. Political Sci. 2022, 25, 463–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Edwards, J.S.; Dwivedi, Y.K. Artificial intelligence for decision making in the era of Big Data–evolution, challenges and research agenda. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 48, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarrahi, M.H. Artificial intelligence and the future of work: Human-AI symbiosis in organizational decision making. Bus. Horiz. 2018, 61, 577–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, B.; Rahman, Z. Artificial intelligence and value co-creation: A review, conceptual framework and directions for future research. J. Serv. Theory Pract. 2024, 34, 7–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, C.; Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, R. The double-edged sword in the digitalization of human resource management: Person-environment fit perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 180, 114738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowday, R.T.; Steers, R.M.; Porter, L.W. The measurement of organizational commitment. J. Vocat. Behav. 1979, 14, 224–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A. Commitment before and after: An evaluation and reconceptualization of organizational commitment. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2007, 17, 336–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, L.W.; Steers, R.M.; Mowday, R.T.; Boulian, P.V. Organizational commitment, job satisfaction, and turnover among psychiatric technicians. J. Appl. Psychol. 1974, 59, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Allen, N.J. A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 1991, 1, 61–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, N.J.; Meyer, J.P. The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization. J. Occup. Psychol. 1990, 63, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, H.J.; Molloy, J.C.; Brinsfield, C.T. Reconceptualizing workplace commitment to redress a stretched construct: Revisiting assumptions and removing confounds. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2012, 37, 130–151. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, G.; Li, Y.; Hong, A. The strategic role of digital transformation: Leveraging digital leadership to enhance employee performance and organizational commitment in the digital era. Systems 2024, 12, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Tian, F.; Sun, X.; Zhang, D. The effects of entrepreneurship on the enterprises’ sustainable innovation capability in the digital era: The role of organizational commitment, person–organization value fit, and perceived organizational support. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saks, A.M.; Gruman, J.A. What do we really know about employee engagement? Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2014, 25, 155–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, C.; Patterson, M.; Dawson, J. Building work engagement: A systematic review and meta-analysis investigating the effectiveness of work engagement interventions. J. Organ. Behav. 2017, 38, 792–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizzi, L. Should HR managers allow employees to use social media at work? Behavioral and motivational outcomes of employee blogging. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2020, 31, 1285–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kular, S.; Gatenby, M.; Rees, C.; Soane, E.; Truss, K. Employee Engagement: A Literature Review; Kingston University: Kingston, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, P.; Turner, P. What is employee engagement? In Employee Engagement in Contemporary Organizations: Maintaining High Productivity and Sustained Competitiveness; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2020; pp. 27–56. [Google Scholar]

- Ruggiero, T.E. Uses and gratifications theory in the 21st century. Mass Commun. Soc. 2000, 3, 3–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, J. Artificial intelligence: Implications for the future of work. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2019, 62, 917–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortorella, G.L.; Powell, D.; Hines, P.; Mac Cawley Vergara, A.; Tlapa-Mendoza, D.; Vassolo, R. How does artificial intelligence impact employees’ engagement in lean organisations? Int. J. Prod. Res. 2025, 63, 1011–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moin, M.F.; Behl, A.; Zhang, J.Z.; Shankar, A. AI in the organizational nexus: Building trust, cementing commitment, and evolving psychological contracts. Inf. Syst. Front. 2025, 27, 1413–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.N.; Soomro, M.A.; Pitafi, A.H. AI in the workplace: Driving employee performance through enhanced knowledge sharing and work engagement. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Interact. 2024, 41, 10699–10712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riyanto, S.; Endri, E.; Herlisha, N. Effect of work motivation and job satisfaction on employee performance: Mediating role of employee engagement. Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2021, 19, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salanova, M.; Schaufeli, W.B. A cross-national study of work engagement as a mediator between job resources and proactive behaviour. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2008, 19, 116–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, E.A.; Sirota, D.; Wolfson, A.D. An experimental case study of the successes and failures of job enrichment in a government agency. J. Appl. Psychol. 1976, 61, 701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Towards a model of work engagement. Career Dev. Int. 2008, 13, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, G.; Pathak, R.; Kumari, S. Impact of employee engagement on job satisfaction and motivation. In Global Advancements in HRM Innovation and Practices; Bharti Publications: New Delhi, India, 2017; pp. 68–78. [Google Scholar]

- Saks, A.M. Antecedents and consequences of employee engagement. J. Manag. Psychol. 2006, 21, 600–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulou, D.; Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Schaufeli, W.B. The role of personal resources in the job demands-resources model. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2007, 14, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xanthopoulou, D.; Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Schaufeli, W.B. Reciprocal relationships between job resources, personal resources, and work engagement. J. Vocat. Behav. 2009, 74, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Sanz-Vergel, A.I. Burnout and work engagement: The JD–R approach. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2014, 1, 389–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borman, W.C.; Motowidlo, S.J. Task performance and contextual performance: The meaning for personnel selection research. Hum. Perform. 1997, 10, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T.A.; Thoresen, C.J.; Bono, J.E.; Patton, G.K. The job satisfaction–job performance relationship: A qualitative and quantitative review. Psychol. Bull. 2001, 127, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Bal, M.P. Weekly work engagement and performance: A study among starting teachers. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2010, 83, 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ma, L.; Xu, B.; Xu, F. How social media usage affects employees’ job satisfaction and turnover intention: An empirical study in China. Inf. Manag. 2019, 56, 103136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, N.P.; Whiting, S.W.; Podsakoff, P.M.; Blume, B.D. Individual-and organizational-level consequences of organizational citizenship behaviors: A meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tett, R.P.; Meyer, J.P. Job satisfaction, organizational commitment, turnover intention, and turnover: Path analyses based on meta-analytic findings. Pers. Psychol. 1993, 46, 259–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.J.; Lewis, G.B. Turnover intention and turnover behavior: Implications for retaining federal employees. Rev. Public Pers. Adm. 2012, 32, 4–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bothma, C.F.; Roodt, G. The validation of the turnover intention scale. SA J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.W. How job dissatisfaction leads to employee turnover. J. Bus. Pychology 1988, 2, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Wang, C.; Lan, Y.; Wu, X. Nurses’ turnover intention, hope and career identity: The mediating role of job satisfaction. BMC Nurs. 2022, 21, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Li, N.; Li, C.; Li, J. The boon and bane of creative “stars”: A social network exploration of how and when team creativity is (and is not) driven by a star teammate. Acad. Manag. J. 2020, 63, 613–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, C.; Humphrey, R.H.; Qian, S. A cross-cultural meta-analysis of how leader emotional intelligence influences subordinate task performance and organizational citizenship behavior. J. World Bus. 2018, 53, 463–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. Translation and content analysis of oral and written materials. In Handbook of Cross-Cultural Psychology: Methodology; Triandis, H.C., Berry, J.W., Eds.; Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 1980; Volume 2, pp. 389–444. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, C.C.; Owens, B.P.; Tesluk, P.E. Initiating and utilizing shared leadership in teams: The role of leader humility, team proactive personality, and team performance capability. J. Appl. Psychol. 2016, 101, 1705–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, S.H.; Saleem, F.; Murtaza, G.; Haq, T.U. Exploring the impact of green human resource management on environmental performance: The roles of perceived organizational support and innovative environmental behavior. Int. J. Manpow. 2022, 43, 742–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moqbel, M.; Nevo, S.; Kock, N. Organizational members’ use of social networking sites and job performance. Inf. Technol. People 2013, 26, 240–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Beurden, J.; Van de Voorde, K.; Van Veldhoven, M.; Jiang, K. Do managers and employees see eye to eye? A dyadic perspective on high-performance work practices and their impact on performance. J. Bus. Res. 2025, 190, 115190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boswell, W.R.; Watkins, M.B.; del Carmen Triana, M.; Zardkoohi, A.; Ren, R.; Umphress, E.E. Second-class citizen? Contract workers’ perceived status, dual commitment and intent to quit. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 454–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Ali, A. Enhancing team creative performance through social media and transactive memory system. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 39, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, H.; Abrar, M.; Ahmad, B. Humility breeds creativity: The moderated mediation model of leader humility and subordinates’ creative service performance in hospitality. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2023, 35, 4117–4136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, D.P.; Lockwood, C.M.; Williams, J. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2004, 39, 99–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a Silver Bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.W.K.; Chan, A. Knowledge sharing and social media: Altruism, perceived online attachment motivation, and perceived online relationship commitment. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 39, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, E.; Leidner, D.; Riemenschneider, C.; Koch, H. The impact of internal social media usage on organizational socialization and commitment. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Systems (ICIS), Milan, Italy, 15–18 December 2013; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Tavitiyaman, P.; So, C.Y.A.; Chan, O.L.K.; Wong, C.K.C. How task technology fits with employee engagement, organizational support, and business outcomes: Hotel executives’ perspective. J. China Tour. Res. 2022, 18, 1212–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Huang, Q.; Davison, R.M.; Yang, F. Role stressors, job satisfaction, and employee creativity: The cross-level moderating role of social media use within teams. Inf. Manag. 2021, 58, 103317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laguerre, R.A.; Barnes-Farrell, J.L. Bringing self-determination theory to the forefront: Examining how human resource practices motivate employees of all ages to succeed. J. Bus. Psychol. 2025, 40, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allal-Chérif, O.; Aranega, A.Y.; Sánchez, R.C. Intelligent recruitment: How to identify, select, and retain talents from around the world using artificial intelligence. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 169, 120822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, C.B.; Osborne, M.A. The future of employment: How susceptible are jobs to computerisation? Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2017, 114, 254–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).