Abstract

Cross-border e-commerce (CBEC) involves online transactions between sellers and consumers across national borders. Despite increasing volatility in international trade, the CBEC market continues to grow, making it critical to understand how firms manage logistics uncertainty. This study investigates how internal and external uncertainties differently influence logistics service flexibility (LSF) and logistics information system (LIS) utilization. Using survey data from 214 CBEC professionals primarily located in Korea, structural equation modeling (SEM) reveals divergent patterns: (1) external uncertainties enhance logistics flexibility, whereas internal uncertainties show no significant direct effect; (2) internal uncertainties negatively affect LIS utilization, while external uncertainties show a marginally positive relationship; and (3) LIS utilization mediates the negative pathway from internal uncertainty to flexibility. These findings indicate that firms respond asymmetrically to uncertainty sources, challenging the view that uncertainty universally promotes digital adaptation. Framing LSF (reconfiguration) and LIS use (sensing/seizing) as distinct dynamic capabilities, our results show source-contingent activation: external turbulence catalyzes reconfiguration, whereas internal frictions dampen sensing/seizing, indirectly suppressing flexibility. By identifying an indirect-only (negative) pathway from internal uncertainty via LIS, we refine dynamic capability theory in CBEC logistics and delineate boundary conditions under which uncertainty does not automatically induce digital adaptation.

1. Introduction

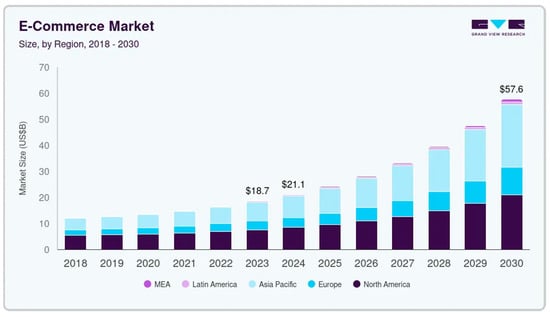

The global e-commerce market was valued at USD 18.7 trillion in 2023. It is projected to reach USD 57.6 trillion by 2030, as presented in Figure 1, representing an estimated annual average growth rate (CAGR) of 18.2% from 2024 to 2030 [].

Figure 1.

E-commerce worldwide market size 2018—2030 (see Supplementary Materials: https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/e-commerce-market, accessed on 5 October 2025).

Online purchases surged globally over three years before and after the COVID-19 pandemic, based on a dataset covering 44 economies and 26 sectors []. The expansion was accompanied by the diversification of e-commerce product categories, a rise in elderly online shoppers, and the adoption of omnichannel strategies across sales platforms. The adoption of advanced technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI), the Internet of Things (IoT), and augmented reality (AR), driven by the Fourth Industrial Revolution, is further reshaping the industry. Barlow & Li [] illustrated how internet-related technologies strengthened and widened linkages in the value network by providing a means for greater integration, information sharing, customization, visibility and flexibility, which has led to greater co-ordination and optimization. As an increasingly diverse range of commodities are purchased by a wider variety of buyers, the global cross-border e-commerce (CBEC) supply chain has become more complex, with business processes growing more intricate and uncertain. A primary source of operational uncertainty is the structural complexity of the CBEC supply chain in Korea, which involves an expanding and diverse network of stakeholders [].

A review of Korean academic publications from 2010 to 2020 reveals that CBEC-related research has been predominantly focused on marketing perspectives, particularly from the viewpoint of consumers []. Similarly, an analysis of 308 scientific papers published in journals indexed by the Chinese Social Sciences Citation Index (CSSCI) reveals that the dominant themes concern e-commerce and global business, government policy and regulation, and specific aspects of CBEC, particularly banking and logistics []. Despite this growing body of research, limited empirical attention has been paid to the operational dynamics of CBEC logistics—an area that offers greater practical applicability for CBEC-related companies in their day-to-day operations. In highly uncertain environments, companies prioritize flexibility, and effective supply chain flexibility is essential for managing diverse sources of uncertainties []. Giuffrida et al. [] emphasized the importance of uncertainty control in logistics and proposed product-level numerical optimization approaches.

Logistics information systems (LISs) can be one of the vehicles for achieving productivity improvement in logistics []. For example, Amazon improved forecast accuracy for over 400 million Stock Keeping Units (SKUs) by leveraging advanced LISs. Flexibility, on the other hand, can also enhance operational excellence. For example, I-Hub—a Korean e-commerce platform provider specializing in health supplements—strengthened its transportation flexibility by diversifying away from air freight toward a multimodal approach including ocean and intermodal options.

This study identifies uncertainty, logistics service flexibility, and LIS utilization as critical enablers for the effective implementation and optimization of CBEC global supply chains. It examines the interrelationships among these factors, with a specific focus on the mediating role of LIS.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Development of Research Hypotheses

2.1.1. Uncertainties and Dynamic Capabilities

In logistics and supply chain management, uncertainties arise from two primary sources: within the supply chain (internal) and from the external environment. Internal uncertainties refer to factors under the firm’s direct control, such as variability in internal processes, production, or information flows. External uncertainties stem from forces outside the organization’s immediate control, including market demand fluctuations, regulatory changes, political disruptions, or natural disasters. This distinction is well-established in the literature; for example, Simangunsong et al. [] classify uncertainties into internal organization, internal supply chain, and external environment groups, while Shi et al. [] (2016) and Tilokavichai et al. [] similarly distinguished internal uncertainties within direct supply chain activities from external uncertainties arising in the broader environment. In CBEC logistics, internal uncertainties might include fulfillment delays or IT system failures, whereas external uncertainties encompass customs clearance delays, exchange rate volatility, or sudden international regulatory changes. Recognizing these two domains of uncertainties is crucial, as they disrupt supply chain performance differently and necessitate distinct managerial strategies.

Flexibility in supply chains is widely regarded as an essential capability for managing such uncertainties and adapting to change. It forms a key part of supply chain agility and responsiveness, especially salient in the post-COVID-19 landscape marked by frequent and severe disruptions []. Flexibility denotes the logistics system’s ability to adapt or reconfigure operations—such as adjusting delivery modes, volumes, or schedules—to fulfill customer needs despite disruptions. Supply chain agility, which encompasses flexibility, helps organizations respond swiftly to uncertainties and gain competitive advantage. For instance, agile supply chains responded more rapidly to pandemic-induced shocks, with flexibility in processes like shipment rerouting and capacity scaling enabling superior crisis management. Wong et al. [] demonstrated that firms with greater delivery and production flexibility outperformed others under high environmental uncertainty, highlighting that uncertain environments intensify the need for flexibility. Lee and Park [] confirmed that environmental uncertainty positively influences supply chain flexibility, prompting firms operating in volatile markets to invest more in flexible practices. Moreover, prior research underscores the importance of matching flexibility levels to uncertainty levels, showing that firms with higher flexibility in uncertain environments outperform competitors. However, flexibility does not arise spontaneously; it is underpinned by a firm’s dynamic capabilities.

Dynamic Capabilities Theory offers a robust lens to explain why uncertainties propel firms to develop flexibility. Dynamic capabilities are an organization’s higher-order abilities to sense environmental changes, seize emerging opportunities, and reconfigure re-sources and processes in response to turbulent environments []. Supply chain flexibility, from this perspective, is an adaptive capability reflecting the firm’s capacity to restructure logistics resources and operations as uncertainties emerge. Strategic flexibility, framed as a dynamic capability, enables firms to respond effectively in uncertain environments. For example, Rehman and Jajja [] argued that turbulent settings motivate firms to build strategic flexibility and integration as adaptive mechanisms. Flexible logistics services—such as swiftly adjusting delivery modes, volumes, routes, or service offerings—empower supply chains to absorb or respond rapidly to both internal and external shocks. Flexibility thus manifests an organization’s capacity to dynamically reconfigure supply chain resources in real time to manage unexpected events. Environmental uncertainties act as a catalyst, encouraging firms to develop and deploy strategic flexibility. Organizations facing high unpredictability must learn and adapt quickly, cultivating agility and flexibility critical to survival and success. Recent studies reinforce that environmental turbulence significantly affects supply chain dynamic capabilities, with flexibility and agility being external reflections of these capabilities. From this perspective, we explicitly position logistics service flexibility (LSF) as the reconfiguration capability and logistics information systems (LIS) utilization as the sensing/seizing capability within the dynamic-capabilities framework, indicating that different uncertainty sources may trigger different capability sets.

Extending this understanding, this study examines how uncertainties influence logistics service flexibility and LIS utilization in CBEC supply chains. Logistics service flexibility is the ability to adapt delivery services, transportation modes, and fulfillment operations in response to evolving demands or disruptions []. Internal uncertainties—such as unreliable internal lead times, inventory inaccuracies, or IT failures—drive the need to enhance internal process flexibility and resilience. Zhang et al. [] suggested that firms mitigate these business uncertainties by increasing operational flexibility through cross-training, modular workflows, and scalable warehousing. This aligns with Dynamic Capabilities Theory, where organizations reconfigure internal resources to address variability and improve responsiveness. However, when internal frictions are high, firms may underinvest in or underutilize LIS due to concerns over data quality, interoperability, or governance, which in turn indirectly suppresses flexibility. External uncertainties—such as fluctuating global demand, customs delays, regulatory shifts, or pandemic. External uncertainties—such as fluctuating global demand, customs delays, regulatory shifts, or pandemics—similarly necessitate heightened logistics flexibility. High environmental uncertainty significantly affects delivery flexibility, as firms adjust shipment routes, supplier relationships, and distribution methods dynamically.

Alongside flexibility, logistics system utilization—the effective deployment and optimal use of logistics resources such as transportation assets, warehousing capacity, and labor—is critical for CBEC logistics performance. Efficient system utilization ensures maximum capacity is leveraged without overloading resources, enabling rapid reallocation or scaling of capabilities to respond to fluctuating demands and disruptions. High utilization underpins flexible logistics operations by facilitating quick adjustments in resource allocation and supporting diverse delivery modes and schedules. Conversely, poor utilization—either under- or over-utilization—can impair responsiveness and agility, limiting the supply chain’s ability to adapt. Advanced technologies and intelligent systems, including AI-driven route optimization and real-time data integration, support improved system utilization, enhancing both operational efficiency and flexibility. In our model, LIS utilization—encompassing real-time visibility, data integration, and analytics-driven decision support—operationalizes the sensing/seizing microfoundations that enable reconfiguration (LSF).

2.1.2. Impact of Internal and External Uncertainties on Logistics Service Flexibility

In the context of general logistics, uncertainties can be categorized based on stakeholders into internal uncertainties, which fall within the scope of direct involvement and control in the supply chain, and external uncertainties, which lie beyond direct involvement and control [,]. Logistics service flexibility generally refers to the capability of logistics systems to adapt delivery services, transportation modes, and fulfillment operations in response to evolving demands or disruptions []. Flexibility is a key component of supply chain agility and responsiveness, particularly in the post-COVID-19 landscape []. Prior research has shown that environmental uncertainties positively influence supply chain flexibility []. Zhang et al. [] suggested that business uncertainties can be mitigated by increasing flexibility in internal operations. Wong et al. [] further demonstrated that high levels of environmental uncertainties significantly affect delivery flexibility.

Service flexibility plays even more crucial role in CBEC logistics than in general logistics. CBEC operations involve additional complexities such as customs declarations, duties, international regulations, and multi-country transportation often with limited direct communication with customers or suppliers. High logistics service flexibility enables CBEC firms to reroute shipments, switch between transport modes, or modify fulfillment processes to maintain service continuity despite such disruptions.

Building on Dynamic Capabilities Theory, this study examines how internal and external uncertainties stimulate the need for logistics service flexibility in CBEC supply chains. Prior research demonstrates that environmental and business uncertainties positively influence operational flexibility [,,]. Extending these insights, this study proposes that both internal (e.g., process variability, IT failures) and external (e.g., customs delays, policy changes) uncertainties motivate firms to enhance logistics service flexibility as an adaptive mechanism. Accordingly, the following hypotheses are proposed.

H1.

Internal uncertainties in CBEC logistics positively influence logistics service flexibility.

H2.

External uncertainties in CBEC logistics positively influence logistics service flexibility.

2.1.3. Impact of Internal/External Uncertainties on Logistics Information Systems Utilization

Logistics Information Systems (LIS) are digital infrastructures that process, transmit, and analyze logistics-related data to support operational decision-making. LIS serves as comprehensive systems that integrate logistics functions—such as transportation, storage, handling, and packaging—throughout the entire supply chain, from production to consumption, to enhance overall logistics management efficiency [].

LIS utilization refers to the strategic use of information technologies that enhance risk management, accuracy, visibility, collaboration, and responsiveness across the supply chain. Effective LIS utilization positively influences performance, so firms should encourage effective LIS utilization to improve operational performance []. Vakhovych et al. [] further argued that the growing impact of diverse risks requires specialized risk management in logistics systems to enable rapid adaptation to external conditions, optimize material flows, and improve coordination. In a similar vein, Zeng et al. [] highlighted that the Information and Decision Risk Network (IDRN) is composed of a communication subnetwork—capturing transmission efficiency and delay—and a decision risk subnetwork—reflecting the diffusion of un-certainty and risk contagion triggered by information delays.

The scope of LIS has expanded significantly. Broadly defined, LIS encompasses transportation management systems, vehicle routing and scheduling systems, warehouse management systems, enterprise resource planning systems, and other digital solutions that support logistics operations []. Environmental uncertainty affects both the availability and quality of logistics-related information, which in turn influences the degree of innovation, development, and utilization of LIS; empirical evidence shows that companies actively leverage LIS to mitigate such uncertainty, with a significant positive relationship between uncertainty and LIS utilization []. Furthermore, in the context of CBEC logistics, LIS utilization can improve risk mitigation by protecting user data and privacy, preventing forgery and fraud, and enhancing traceability [].

This perspective underscores that disruptions in information flow amplify uncertainty and eventually reinforce the need for effective LIS utilization to mitigate such risks. Building on these insights, this study investigates the impact of uncertainty on LIS utilization within CBEC supply chains.

H3.

Internal uncertainties in CBEC logistics positively influence LIS utilization.

H4.

External uncertainties in CBEC logistics positively influence LIS utilization.

2.1.4. Impact of Logistics Information System Utilization on Logistics Service Flexibility

In practice, LIS typically consists of four core modules: Materials Management (MM), Sales and Distribution (SD), Warehouse Management Systems (WMS), and Transportation Management Systems (TMS). A robust LIS enables the integration of real-time data updates, supporting more accurate forecasting and early risk detection []. In the retail sector, particularly for consumer electronics, such systems can enhance customer service by providing more precise assistance []. Furthermore, customer feedback systems allow companies to gain nuanced insights into consumer preferences and pain points [], while active information sharing among stakeholders enhances supply chain flexibility []. The agility of logistics information systems has also been shown to improve flexibility within the supply chain [], and information sharing further strengthens the link between supplier learning and flexibility performance []. Building on these findings, this study examines the impact of LIS utilization on logistics service flexibility.

H5.

Logistics information system utilization in CBEC positively influences logistics service flexibility.

3. Results

3.1. Research Design and Data Collection

This study examines four constructs related to CBEC logistics: internal uncertainty (7 items), external uncertainty (8 items), logistics service flexibility (4 items), and logistics information system utilization (3 items). Items were adapted from established literature and measured on a 7-point Likert scale. Each respondent evaluated both high- and low-involvement products, resulting in 44 survey questions (22 per product category).

The survey was conducted from February to April 2022 via Google Forms and face-to-face questionnaires. Participants were professionals with substantial experience in CBEC logistics, including logistics service providers, shippers, consignees, CBEC platform providers, and related firms. A total of 268 responses were collected, of which 214 were retained after excluding incomplete or duplicate entries. Respondents were assured anonymity and voluntary participation. The demographic characteristics of the sample are summarized in Table 1. SPSS 25 and AMOS 27 were used for hypothesis testing.

Table 1.

Respondent Characteristics (N = 214).

3.2. Validation of Measurement Tools

3.2.1. Exploratory Factor Analysis

To assess the suitability of the data for exploratory factor analysis, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test was conducted. According to Huo et al. [], a KMO value of 0.9 or higher is considered marvelous, values in the 0.80 s are meritorious, those in the 0.70 s are middling, values in the 0.60 s are mediocre, those in the 0.50 s are miserable, and values below 0.5 are deemed unacceptable. The KMO value for this study was calculated as 0.854, indicating meritorious sampling adequacy. Bartlett’s test of sphericity was also performed to examine whether the correlation matrix was an identity matrix. The test yielded a statistically significant chi-square probability (p = 0.000), leading to the rejection of the null hypothesis and confirming that the data are appropriate for factor analysis. Factor loadings were assessed with a threshold of 0.4 or higher [], and Varimax rotation was applied to enhance interpretability.

3.2.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

The reliability coefficient (Cronbach’s α) was used to assess the internal consistency of item-scale variables. According to Bagozzi and Yi [], a reliability coefficient of 0.6 or higher is considered acceptable. In this study, reliability coefficients for all factors ranged from 0.821 to 0.937, as shown in Table 2, indicating strong reliability of the measurement tool. Construct reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE) were used to evaluate the validity and reliability of constructs. Hair [] suggested that a CR value of 0.7 or higher indicates sufficient reliability, while an AVE value of 0.5 or higher supports acceptable convergent validity. In this study, CR values ranged from 0.871 to 0.923, and AVE values ranged from 0.646 to 0.800, both exceeding their respective thresholds.

Table 2.

Confirmatory factor analysis results.

Additionally, Fornell and Larcker [] define that discriminant validity is established when a construct’s AVE is greater than the squared correlation between that construct and any other. In this study, all AVE values exceeded their corresponding squared correlations, confirming discriminant validity, as displayed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Factor analysis results.

3.2.3. Goodness-of-Fit and Model Validity

This study employed the structural equation modeling (SEM) method, following the approach of Fornell and Larcker []. To assess the goodness-of-fit of the SEM, Woo [] evaluated model suitability using three indices: the absolute fit index, the incremental fit index, and the parsimonious fit index. Table 4 presents the analysis results for the two independent variables-internal uncertainty and external uncertainty. The model fit indices indicate strong validity, with CFI = 0.97, NFI = 0.95, and TLI = 0.97, all exceeding the recommended threshold of 0.90. The root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), a common measure of model fit, was 0.05, which is at the acceptable threshold, indicating a good model fit. The chi-square divided by degrees of freedom (CMIN/DF) was 1.94, satisfying the criterion of 3 or lower [].

Table 4.

Goodness of fit of the research model.

3.3. Measurement Tool for Research

3.3.1. Research Testing Model

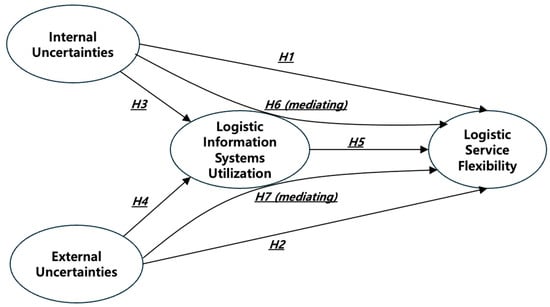

The research hypothesis test model for internal and external uncertainties on logistics service flexibility in CBEC is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

A diagram detailing the research model.

3.3.2. Relationship Between Internal and External Uncertainties, Logistics Service Flexibility, and LIS Utilization in CBEC Logistics

Table 5 summarizes the test results for hypotheses 1 to 5. The results for H1 indicate that internal uncertainty in CBEC logistics does not significantly affect logistics service flexibility (β = −0.041, p > 0.05); therefore, H1 is not supported. The results for H2 show that external uncertainty related to CBEC logistics positively impacts logistics service flexibility (β = 0.650, p < 0.05), thus H2 is supported. This finding aligns with a previous study by Lee and Park []. Similarly, Lei et al. [] describe emergencies—triggered by natural disasters or human factors—as complex, unpredictable, and socially hazardous events that heighten external uncertainty in logistics systems. From an information theory perspective, they further argue that indicators with greater information content reduce uncertainty by lowering entropy values. These insights reinforce the interpretation that external uncertainty encourages firms to actively enhance logistics service flexibility.

Table 5.

Result of relationship between independent variables and dependent variables.

H3 is not supported. The test results indicate that internal uncertainties in CBEC logistics negatively, instead of positively, impact the utilization of logistics information systems (β = −0.163, p < 0.05). Although H3 hypothesizes a positive effect, this significant negative relationship provides critical insights into managerial behavior under uncertainty. The findings suggest that LIS utilization tends to decrease as internal uncertainty increases. This pattern can be interpreted as firms becoming more reactive—resorting to manual interventions or ad hoc solutions—rather than pursuing systematic and data-driven responses when facing internal uncertainties in inventory control or product return handling.

Follow-up interviews with logistics professionals further reinforce this interpretation. A practitioner of a third party logistics service provider explained “When the return volume spikes unexpectedly and those are not proceeded accurately in ERP, managers tend to rely on manual counting and accounting adjustment. Similarly, another practitioner from a manufacturing company selling through CBEC channel noted “When unanticipated warehouse space shortage arises due to overproduction or weak sales, our first response is to find extra space rather than addressing the root causes of inaccurate forecasting in sales, production, or inventory.”

Such responses reveal a behavioral tendency to prioritize immediate, hands-on problem solving over system-based analysis during periods of internal turbulence—even though LIS is designed to enhance adaptability. This asymmetry offers an important theoretical implication: internal uncertainty can trigger short-term operational reactions that undermine digital system reliance, thereby reducing the potential benefits of LIS utilization.

This implication aligns with Tilokavichai et al. [], who reported that external uncertainties, such as customer demand, positively influence customer service performance, whereas internal uncertainties, such as product quality, packaging quality, and IT system reliability, exert a negative impact.

The test results for H4 show that external uncertainty in CBEC logistics does not positively impact the utilization of the logistics information systems (β = 0.599, p = 0.060). Although H4 is not supported at the 0.05 level, the near-significant result indicates a marginal relationship that warrants further exploration. One possible explanation for this outcome is the heterogeneity of firms in their digital maturity. While many CBEC firms still use LIS primarily for transactional efficiency and internal coordination mainly focusing on ERP systems, some advanced companies have begun upgrading or extending their systems to better interface with external information platforms—such as transportation information systems, customer relationship management tools, and other interorganizational databases—to monitor and control broader external risks. This divergence may have produced a borderline statistical effect, indicating that LIS responsiveness to external uncertainty is emerging but not yet widespread across the CBEC sector.

As a result, risks such as sudden tariff adjustments, geopolitical disruptions, and port strikes may not be effectively managed through enhanced LIS utilization in some companies, whereas others respond proactively with advanced LIS utilization. This finding highlights a gap between external uncertainty and system responsiveness—a critical direction for both LIS development and managerial practice. A thematically consistent outcome was reported by Carr and Kaynak [], who found that the hypothesized positive effect of advanced communication methods on inter-firm information sharing was not supported by their empirical evidence.

H5 is supported. This hypothesis examines the relationship between logistics information system utilization and logistics service performance. The results show that CBEC logistics information system utilization positively impacts logistics service flexibility (β = 0.495, p < 0.01), supporting H5. Kampf et al. [] also found that knowledge-based logistics information systems are linked to customers’ preference in their e-shopping.

3.3.3. The Mediating Role of LIS Utilization on the Relationship Between Internal and External Uncertainties and Logistics Service Flexibility

To examine the mediating role of logistics information system (LIS) utilization, the bootstrap test proposed by Preacher and Hayes [] was applied. The results, presented in Table 6, indicate that LIS utilization significantly mediates the relationship between internal uncertainty and logistics service flexibility (H6 supported, β = −0.081, p < 0.05). The negative coefficient indicates that the mediation occurs in an adverse direction—higher internal uncertainty diminishes LIS utilization, which consequently reduces logistics service flexibility. Although the direct effect of internal uncertainty on logistics service flexibility (H1) is not significant, the significant negative indirect effect through LIS utilization reveals a deteriorating causal path: higher internal uncertainty leads to reduced use of LIS, which in turn lowers logistics service flexibility. This indicates that internal problems not only disrupt operations directly but also weaken the digital mechanisms designed to enhance flexibility.

Table 6.

Mediating analysis results.

In contrast, no significant mediation is observed for external uncertainty (H7 not sup-ported, β = 0.297, p > 0.05). A similar absence of moderating effects was noted by Zakaria et al. [], who found that logistics information technology did not moderate the relationship between logistics relationships and service quality, suggesting that contextual or behavioral factors—such as trust and communication—may influence digital tool effectiveness.

4. Discussion

4.1. Overview of Key Findings

This study examined how internal and external uncertainties affect logistics service flexibility and LIS utilization in the context of CBEC logistics as summarized in Table 7. The findings indicate three notable patterns. The findings indicate three notable patterns. First, only external uncertainties significantly influence logistics service flexibility (H2), while internal uncertainties do not (H1).

Table 7.

Hypothesis test results.

Second, the results indicate distinct behavioral patterns between internal and external uncertainties in relation to LIS utilization. While the influence of external uncertainties on LIS utilization (H4) is not statistically supported, internal uncertainties exert a significant negative effect (H3). The result for H4, however, shows a marginal tendency in the expected direction (p = 0.06).

Third, LIS utilization mediates the relationship between internal uncertainties and logistics service flexibility (H6) but not between external uncertainties and logistics service flexibility (H7). The coefficient for the mediation in H6 test is slightly negative (β = −0.081), suggesting that under conditions of high internal uncertainty, greater use of LIS utilization may even inhibit flexibility rather than enhance it.

4.2. Differences Between Internal and External Uncertainties on Logistics Service Flexibility

The test results show that external uncertainties positively influence logistics service flexibility (H2), while internal uncertainties show no significant effect (H1). This contrast suggests that the source and perceived controllability of uncertainty are decisive factors shaping how firms pursue their service flexibilities in CBEC logistics.

External uncertainties—such as demand fluctuations, customs regulation changes, or geopolitical disruptions—are largely outside a firm’s immediate control. To mitigate these risks, firms enhance adaptive capabilities, particularly logistics service flexibility. In contrast, internal uncertainties—stemming from factors such as inaccurate forecasting, inventory imbalance, or production misalignment—are typically viewed as operational issues within managerial control. Instead of stimulating flexibility, these uncertainties often lead firms to adopt conservative or reactive measures, focusing on short-term corrections rather than systemic improvements. This pattern reflects a defensive orientation, where resources are directed toward immediate operational recovery rather than toward long-term flexibility enhancement.

Overall, this behavioral asymmetry contributes to understanding how CBEC firms differentially allocate flexibility resources under internal versus external uncertainty.

4.3. Negative Influence of Internal Uncertainties and Marginal Tendency of External Uncertainties on LIS Utilization

The findings reveal an unexpected but theoretically meaningful pattern: internal uncertainties negatively affect LIS utilization, while external uncertainties exhibit only a marginally positive relationship.

The negative association between internal uncertainty and LIS utilization (H3) highlights a divergence of digital response in CBEC logistics. When operational disruptions—such as inaccurate forecasting, product returns, or warehouse imbalances—arise within the firm’s control, managers appear to rely more on manual intervention or ad hoc solution than on systematic approaches. This phenomenon aligns with behavioral operations theory, which posits that perceived control and immediacy of response shape decision-making under pressure. It is found in follow-up interviews that internal uncertainties often expose weaknesses within firms’ own processes. In practice, managers tend to solve these issues through spreadsheet-based adjustments, manual counting, or temporary outsourcing, rather than utilizing LIS more effectively.

The hypothesis for the relationship between external uncertainties and LIS utilization (H4) is not supported but shows a marginally positive tendency (β = 0.599, p = 0.060), implying that some CBEC firms employ and utilize LIS to address external volatility. This outcome likely reflects heterogeneity of digital maturity across CBEC firms. Some advanced firms have expanded LIS utilization to integrate transportation management systems, Customer Relationship Management (CRM) platforms, or inter-organizational databases to track customs changes and supply disruptions. Others, however, still utilize LIS mainly for transactional efficiency, without extending its analytical or collaborative functions. This uneven digital evolution may explain why the hypothesized positive effect of external uncertainties on LIS utilization has not yet reached statistical significance.

Taken together, these results suggest a dual dynamic. Internal uncertainty triggers defensive reactions that suppress LIS utilization, while external uncertainty prompts emerging—but still partial—system-based adaptation. This asymmetry reveals both a managerial and technological gap: while LIS has the potential to serve as a stabilizing mechanism under turbulence, its actual adaption and utilization remain contingent on firms’ trust, digital readiness and strategy.

4.4. Mediating Role of LIS Utilization Between Internal Uncertainties and Logistics Service Flexibility

The analysis shows that LIS utilization significantly mediates the relationship between internal uncertainty and logistics service flexibility (H6), while no such mediation is found for external uncertainty (H7).

The negative mediation effect (β = −0.081, p < 0.05) indicates that higher internal uncertainty reduces firms’ reliance on LIS. This reduction, in turn, weakens their ability to maintain flexibility. This counterintuitive outcome reflects a behavioral bias toward manual and short-term responses under pressure. Instead of leveraging digital tools to analyze root causes, managers tend to bypass LIS in favor of direct, experience-based interventions, which limits organizational learning and system-based adaptation.

This pattern indicates that LIS utilization has not yet become an embedded reflex in daily decision-making. Its use depends on managerial confidence and perceived stability of internal processes. When those processes appear unreliable, digital systems are often sidelined—ironically reducing the very flexibility. Strengthening the mediating role of LIS therefore requires not only technical integration but also a shift in managerial mindset toward trusting system outputs even in times of disruption.

4.5. Methods and Characteristics of the Survey Sample

The study adopted a non-probability sampling method, combining purposive and quota approaches. The purposive sampling ensured that only professionals directly involved in CBEC logistics participated in the survey, thereby reflecting their specialized knowledge and operational experience. Additionally, a quota-based approach was applied to maintain a balanced distribution across firm types and job functions.

The survey sample by firm type was relatively skewed toward CBEC platform providers, who accounted for 64% of respondents. Compared with manufacturers or traditional logistics service providers that focus on physical operations, CBEC platform firms tend to emphasize information flows and digital coordination. This composition may have influenced the findings—particularly the prominent role of LIS utilization in the model. However, many major CBEC platform service providers in Korea, such as Coupang and SSG, also operate their own logistics networks and private-label products. Consequently, their responses partly capture the perspectives of manufacturers and logistics providers as well, mitigating the potential bias arising from the sample imbalance.

Overall, the sample is broadly reflective of the Korean CBEC logistics landscape. Nonetheless, broader international sampling and comparative analysis would be valuable to assess the generalizability of these findings.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Asymmetric Effects of Internal/External Uncertainties on Flexibility and Digital Adaptation

The results of this study provide nuanced insights into the role of uncertainties in shaping logistics service flexibility and LIS utilization in CBEC. One key finding is that external uncertainties exert a stronger influence on logistics service flexibility than internal uncertainties. This is consistent with previous logistics studies outside the CBEC domain. For instance, Wang [] demonstrated that demand uncertainty significantly increased third party logistics utilization and improved logistics performance, while operational stability—an internal factor—did not have a significant effect. Similarly, Wu et al. [] reported that international transport disruptions were among the most critical determinants of supply chain responsiveness in global trade. In contrast, studies focusing on domestic logistics contexts (e.g., []) highlighted the importance of internal operational uncertainties, such as warehouse efficiency and inventory control.

At the same time, the study uncovers an unexpected but theoretically meaningful pattern: internal uncertainties exhibit a statistically significant negative effect on LIS utilization. This finding contradicts conventional expectations that uncertainty generally stimulates digital system use. Instead, it suggests that firms experiencing high internal uncertainty—such as inventory imbalances or order-processing disruptions—tend to rely on manual interventions or ad hoc workarounds rather than structured, data-driven decision systems. This behavioral tendency reflects a dual dynamic of digital adaptation: while LIS is intended to enhance responsiveness under uncertainty, managers and end-users often revert to short-term reactive solutions instead of system-based problem solving.

Interestingly, the effect of external uncertainties on LIS utilization was not statistically significant, a finding that diverges from prior studies. For instance, Richey et al. [] reported that demand and market volatility encouraged firms to adopt more sophisticated information systems to enhance decision-making, while Müller et al. [] argued that uncertainty pressures generally accelerate digital adoption across supply chains. The lack of significance observed in the CBEC context suggests that existing LIS functionalities may not yet be well aligned with the types of external risks faced in cross-border operations, implying that current adoption is driven more by efficiency and compliance needs than by risk management.

Moreover, the non-significant influence of internal uncertainties on both logistics service flexibility and LIS utilization contrasts with studies that emphasized the role of internal efficiency in driving digital adoption (e.g., []). This discrepancy suggests that the unique operational environment of CBEC—characterized by cross-border flows, regulatory heterogeneity, and market volatility—shifts the locus of uncertainty from inside the firm to the external environment. In other words, while internal operational challenges remain relevant, they are not decisive triggers of adaptation in CBEC compared to the more urgent external disruptions.

Theoretically, these findings enrich Dynamic Capabilities Theory by differentiating between internal and external uncertainties as antecedents of logistics service flexibility and digital utilization. Prior applications of the theory often treated uncertainty as a single construct, but this study demonstrates that external uncertainties activate dynamic capabilities, whereas internal uncertainties can temporarily suppress their deployment. This finding contributes to a more nuanced understanding of how sensing–seizing–transforming activities operate asymmetrically depending on uncertainty type, aligning with Eisenhardt and Martin [], while clarifying that external volatility, rather than internal instability, primarily drives capability formation in CBEC logistics.

Finally, the results align partially, but not fully, with prior work. While the supported hypotheses confirm the critical role of external risks and LIS-mediated flexibility, the unexpected negative relationship for internal uncertainty challenges the prevailing assumption that uncertainty uniformly drives digital adaptation. This contrast deepens theoretical understanding of logistics adaptation in CBEC by showing that uncertainty can both enable and constrain digital transformation, depending on its source.

5.2. Academic Contributions

This study contributes to the literature on CBEC logistics by examining the interplay between uncertainties in logistics, logistics service flexibility, and LIS. While prior research has emphasized the importance of logistics flexibility in traditional supply chain contexts, few studies have concentrated its focus on CBEC logistics. By situating flexibility within the context of CBEC, this study extends the theoretical understanding of how logistics capabilities mitigate uncertainties in globalized digital trade.

Furthermore, the study advances the discourse on LIS by revealing a dual mechanism of digital adaptation: external uncertainty promotes greater LIS utilization to enhance coordination, whereas internal uncertainty can inhibit digital engagement through reactive managerial behaviors. This insight transforms what might appear as an “unsupported hypothesis” into a key contribution—demonstrating that the relationship between uncertainty and digital adaptation is asymmetric rather than uniform.

By integrating quantitative evidence with qualitative insights from logistics professionals, the paper provides a more comprehensive explanation of this dual mechanism and bridges behavioral, managerial, and technological perspectives. In doing so, it links the micro-level behaviors of logistics managers to macro-level capability development, thereby contributing to the application of Dynamic Capabilities Theory in digitally mediated logistics contexts. This study uniquely positions LIS not merely as an operational tool but as a dynamic capability contingent on behavioral and contextual conditions. This perspective encourages future research to explore how organizational routines and human responses interact with digital systems under different uncertainty conditions. This study shows that logistics flexibility and system utilization collectively contribute to superior service levels and resilience under uncertainty in CBEC settings. Companies investing in flexible transport options, adaptive scheduling, alternative sourcing, and optimized resource utilization perform better amid volatile environments—and our results clarify how: by framing LSF (reconfiguration) and LIS use (sensing/seizing) as distinct dynamic capabilities, our results show source-contingent activation: external turbulence catalyzes reconfiguration, whereas internal frictions dampen sensing/seizing, indirectly suppressing flexibility. By identifying an indirect-only (negative) pathway from internal uncertainty via LIS, we refine Dynamic Capability Theory in CBEC logistics and delineate boundary conditions under which uncertainty does not automatically induce digital adaptation.

5.3. Managerial Implications

Management should prioritize anticipating and adapting to shifts in external factors, such as demand volatility, regulatory changes, and supply chain disruptions, which significantly affect CBEC logistics. The findings suggest that maintaining a flexible logistics network is essential to mitigate uncertainties and sustain competitiveness.

In this regard, management should recognize the central role of LIS in integrating flexibility with external uncertainty management. Investments in LIS should go beyond technical upgrades to enhance interoperability with partners and support real-time data exchange. By leveraging LIS strategically, management can strengthen resilience, improve customer service, and reduce risks associated with disruptions. Therefore, LIS should be viewed not merely as support infrastructure but as a strategic asset that enhances visibility, coordination, and decision-making across the supply chain.

Given the fast-growing and rapidly changing nature of CBEC, proactive investment decisions in LIS should be emphasized even further. To ensure the effective utilization of LIS, companies should regularly review and update policies, foster a supportive organizational culture, and implement continuous training programs.

Finally, companies can respond to logistics issues more effectively by involving business partners and customers in decision-making, thereby fostering supply chain stability through shared responsibilities and information exchange []—a goal that can be further reinforced through the strategic use of LIS.

5.4. Future Directions

Logistics plays a more critical role in CBEC than in domestic e-commerce, making continuous improvement in CBEC logistics particularly important []. This objective can be further advanced through the effective utilization of LIS. Future research should explore ways to extend LIS functionalities for managing both internal and external uncertainties and examine the longitudinal stability of LIS’s mediating effects across different CBEC platforms. Comparative studies across various digital trade ecosystems may further deepen our understanding of effective resilience strategies. In summary, this study demonstrates that external uncertainties are the primary catalysts for logistics service flexibility and LIS utilization in CBEC, while LIS plays a pivotal mediating role in managing uncertainties for operational advantage. Companies should align their digital investments with the most critical sources of uncertainties, adopting a dual strategy that aggressively addresses external risks and systematically upgrades LIS capabilities to manage internal challenges.

5.5. Limitations

This study, while providing valuable insights, has several limitations that offer opportunities for future research. First, this study’s findings are specific to the context of CBEC logistics in Korea. Future research should undertake comparative studies across different regions or countries to enhance the generalizability of these findings. In addition, the considerable interval between the 2022 survey and the 2025 CBEC environment may modestly dilute the temporal relevance of the findings. Future studies could complement this work by conducting updated surveys and analyses to capture more recent perspectives.

Second, the sample composition was skewed toward CBEC platform providers, who accounted for 64% of respondents. Compared with manufacturers or traditional logistics service providers that focus on physical operations, platform providers can tend to emphasize information flows and digital coordination. This composition may have influenced the findings—particularly the central role of LIS utilization in the model. Future studies should aim for a more balanced respondent mix to provide a broader and more representative perspective across stakeholder groups

Third, while this study examined two independent variables, it did not specifically capture external uncertainties arising from competitors and customers within supply chains. For example, rising expectation of customers for shorter delivery lead time or real- time tracking can raise the target service levels for logistics operations. Similarly, competitors’ new promotional strategy or service enhancements driven by new technology adoption can influence firms’ flexibility requirements. Future research could examine how these market-driven external uncertainties affect logistics service flexibility in CBEC.

Fourth, this study did not cover the impact of rapidly evolving technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI) and blockchain, which are reshaping the logistics industry. Addressing these limitations will enhance the robustness and applicability of future research.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/e-commerce-market, Figure S1: E-commerce worldwide market size 2018–2030 (accessed on 5 October 2025).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.C. and H.K.; methodology, D.C.; software, H.K.; validation, S.C. and D.C.; formal analysis, H.K.; investigation, S.C.; resources, H.K.; data curation, H.K.; writing—original draft preparation, S.C.; writing—review and editing, D.C.; visualization, S.C.; supervision, D.C.; project administration, S.C.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in Green View Research at https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/e-commerce-market (accessed on 5 October 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| AR | Augmented Reality |

| CBEC | Cross Border E-Commerce |

| CRM | Customer Relationship Management |

| ERP | Enterprise Resource Planning |

| IDRN | Information and Decision Risk Network |

| LIS | Logistics Information System |

| LoT | Internet of Things (IoT) |

| LSF | Logistics Service Flexibility |

| MM | Material Management |

| SD | Sales and Distribution |

| 3PL | Third Party Logistics |

| TMS | Transportation Management System |

| WMS | Warehouse Management System |

References

- Grandviewresearch. E-Commerce Worldwide Market Size 2018–2030. Available online: https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/e-commerce-market (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Alcedo, J.; Cavallo, A.; Mishra, P.; Spilimbergo, A. Back to trend: COVID effects on e-commerce in 44 countries. J. Macroecon. 2025, 85, 103682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, A.; Li, F. Online value network linkages: Integration, information sharing and flexibility. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2005, 4, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J. Status and outlook of cross-border e-commerce in Korea. Korea Inst. Ind. Econ. Trade 2019, 19, 66–76. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y. Risk and risk management in cross border e-commerce. J. Int. Trade Insur. 2022, 23, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, J.; Hou, Z.; Chen, M.; ICEB, G. A study of the research hot topics and visualization analysis of cross-border ecommerce in China. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Electronic Business, Guilin, China, 2–6 December 2018; Available online: https://aisel.aisnet.org/iceb2018/94 (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Simangunsong, E.; Hendry, L.C.; Stevenson, M. Supply-chain uncertainty: A review and theoretical foundation for future research. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2012, 50, 4493–4523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuffrida, M.; Jiang, H.; Mangiaracina, R. Investigating the relationships between uncertainty types and risk management strategies in cross-border e-commerce logistics. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2021, 32, 1406–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Rahman, N.S.F.; Karim, N.H.; Md Hanafiah, R.; Abdul Hamid, S.; Mohammed, A. Decision analysis of warehouse productivity performance indicators to enhance logistics operational efficiency. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2023, 72, 962–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Zhang, A.; Arthanari, T.; Liu, Y. Third-party purchase: An empirical study of Chinese third-party logistics users. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2016, 36, 286–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilokavichai, V.; Sophatsathit, P.; Chandrachai, A. Establishing customer service and logistics management relationship under uncertainty. World Rev. Bus. Res. 2012, 2, 12–23. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, D.; Ruamsook, K.; Roso, V. Managing supply chain uncertainty by building flexibility in container port capacity: A logistics triad perspective and the COVID-19 case. Marit. Econ. Logist. 2020, 24, 92–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.Y.; Boon-Itt, S.; Wong, C.W. The contingency effects of environmental uncertainty on the relationship between supply chain integration and operational performance. J. Oper. Manag. 2011, 29, 604–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Park, C. A study on the relationship between integration and performance of the R&D chain in the context of environmental uncertainty: Focusing on the R&D perspective. Corp. Manag. Res. 2018, 25, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Teece, D.J. Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 1319–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A.U.; Jajja, M.S.S. The interplay of integration, flexibility and coordination: A dynamic capability view to responding environmental uncertainty. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2023, 43, 916–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zha, X.; Zhang, H.; Dan, B. Information sharing in a cross-border e-commerce supply chain under tax uncertainty. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2022, 26, 123–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.; Choi, S. An empirical study on the effect of service quality on logistics performance of logistics information systems. Electron. Trade Res. 2009, 7, 61–87. [Google Scholar]

- Mlimbila, J.; Mbamba, U.O. The role of information systems usage in enhancing port logistics performance: Evidence from the Dar Es Salaam port, Tanzania. J. Shipp. Trade 2018, 3, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakhovych, I.; Kryvovyazyuk, I.; Kovalchuk, N.; Kaminska, I.; Volynchuk, Y.; Kulyk, Y. Application of information technologies for risk management of logistics systems. In Proceedings of the 2021 62nd International Scientific Conference on Information Technology and Management Science of Riga Technical University (ITMS), Riga, Latvia, 14–15 October 2021; Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/9615297 (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Zeng, Z.; Wang, N.; Xu, D.; Chen, R. Cascading failure modeling and resilience analysis of coupled centralized supply chain networks under hybrid loads. Systems 2025, 13, 729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, J.E.; Bradley, R.V.; Fugate, B.S.; Hazen, B.T. Logistics information system evaluation: Assessing external technology integration and supporting organizational learning. J. Bus. Logist. 2014, 35, 338–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C. Effect of logistics information system and organizational learning degree under environmental uncertainty on logistics performance. Ind. Econ. Res. 2008, 21, 2179–2202. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, P.; Gu, L. Optimization of cross-border e-commerce logistics supervision system based on Internet of Things technology. Complexity 2021, 2021, 4582838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Noh, J.; Kim, J. A study on the utilization of green IT for green growth in Korea. Digit. Trade Rev. 2009, 7, 155–174. [Google Scholar]

- Mor, A.; Orsenigo, C.; Soto Gomez, M.; Vercellis, C. Shaping the causes of product returns: Topic modeling on online customer reviews. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 1, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoodi, L.; Mezei, J.; Heikkilä, M. Aspect-based sentiment classification of user reviews to understand customer satisfaction of e-commerce platforms. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 1, 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmenner, R.W.; Tatikonda, M.V. Manufacturing process flexibility revisited. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2005, 25, 1183–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Drave, V.A.; Bag, S.; Luo, Z. Leveraging smart supply chain and information system agility for supply chain flexibility. Inf. Syst. Front. 2019, 21, 547–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, B.; Haq, M.Z.U.; Gu, M. The impact of information sharing on supply chain learning and flexibility performance. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2021, 59, 1411–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J. Statistical Analysis Method SPSS/AMOS. Paju 21st Century Company. 2014. Available online: https://library.kribb.re.kr/search/catalog/view.do?bibctrlno=116301&ty=B&se=b0 (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Kang, H. A guide on the use of factor analysis in the assessment of construct validity. J. Korean Acad. Nurs. 2013, 43, 587–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the use of structural equation models in experimental designs. J. Mark. Res. 1989, 26, 271–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F. Multivariate Data Analysis; Kennesaw State University: Kennesaw, GA, USA, 2009; Available online: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/facpubs/2925/ (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, J. A study of itemized bias in multidimensional concepts in structural equation models. Korean Manag. Rev. 2015, 44, 1131–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, L.; Yu, S.; Ke, Y.; Deng, L.; Kang, Q. Evaluation model for emergency material suppliers in emergency logistics systems based on game theory-TOPSIS method. Systems 2025, 13, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, A.S.; Kaynak, H. Communication methods, information sharing, supplier development and performance: An empirical study of their relationships. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2007, 27, 346–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampf, R.; Lizbetinova, L.; Tislerova, K. Management of customer service in terms of logistics information systems. Open Eng. 2017, 7, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zakaria, H.; Zailani, S.; Fernando, Y. Moderating role of logistics information technology on the logistics relationships and logistics service quality. Oper. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2014, 3, 134–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M. Logistics Capability, Supply Chain Uncertainty and Risk, and Logistics Performance: An Empirical Analysis of the Australian Courier Industry. Ph.D. Thesis, RMIT University, Melbourne, Australia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, L.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, J.; Su, I.; Tian, S. Digital technologies and supply chain resilience: A resource-action-performance perspective. Inf. Syst. Front. 2025, 2025, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Dresner, M.; Xie, Y. Logistics IS resources, organizational factors, and operational performance: An investigation into domestic logistics firms in China. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2025, 30, 569–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richey, R.G.; Roath, A.S.; Adams, F.G.; Wieland, A. A responsiveness view of logistics and supply chain management. J. Bus. Logist. 2022, 43, 62–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, J.; Hoberg, K.; Fransoo, J.C. Realizing supply chain agility under time pressure: Ad hoc supply chains during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Oper. Manag. 2023, 69, 426–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Huo, B.; Ye, Y. The impact of IT use on supply chain coordination: The moderating role of environmental uncertainty. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2024, 39, 1809–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Martin, J.A. Dynamic capabilities: What are they? Strateg. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 1105–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamba, D.; Yadav, D.K.; Barve, A.; Panda, G. Prioritizing barriers in reverse logistics of e-commerce supply chain using fuzzy-analytic hierarchy process. Electron. Commer. Res. 2020, 20, 381–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Yang, Y.; Tso, G.K.; Li, Y. Analysis of launch strategy in cross-border e-commerce market via topic modeling of consumer reviews. Electron. Commer. Res. 2019, 19, 863–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).