Data-Driven Modeling of Demand-Responsive Transit: Evaluating Sustainability Across Urban, Rural, and Intercity Scenarios

Abstract

1. Introduction

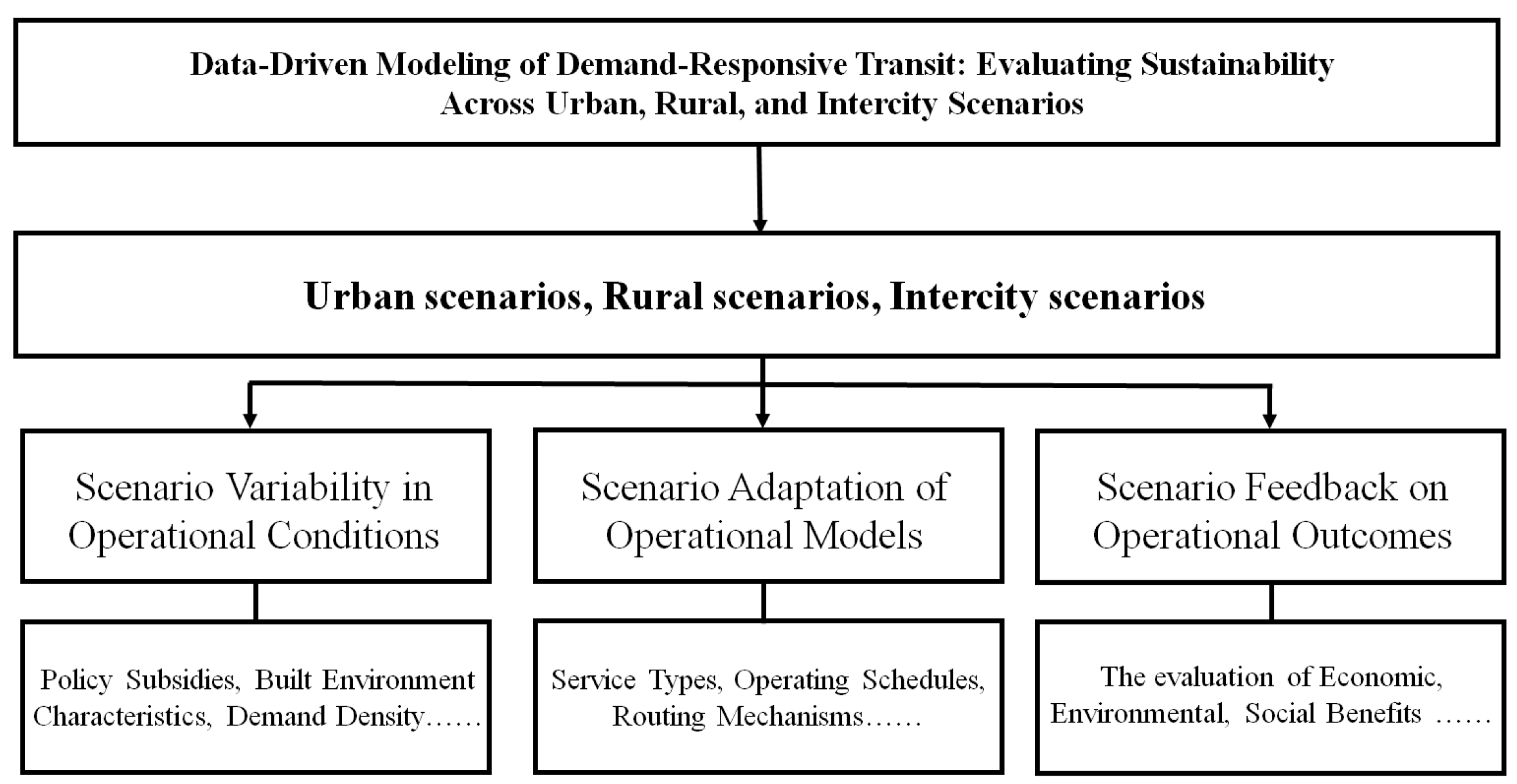

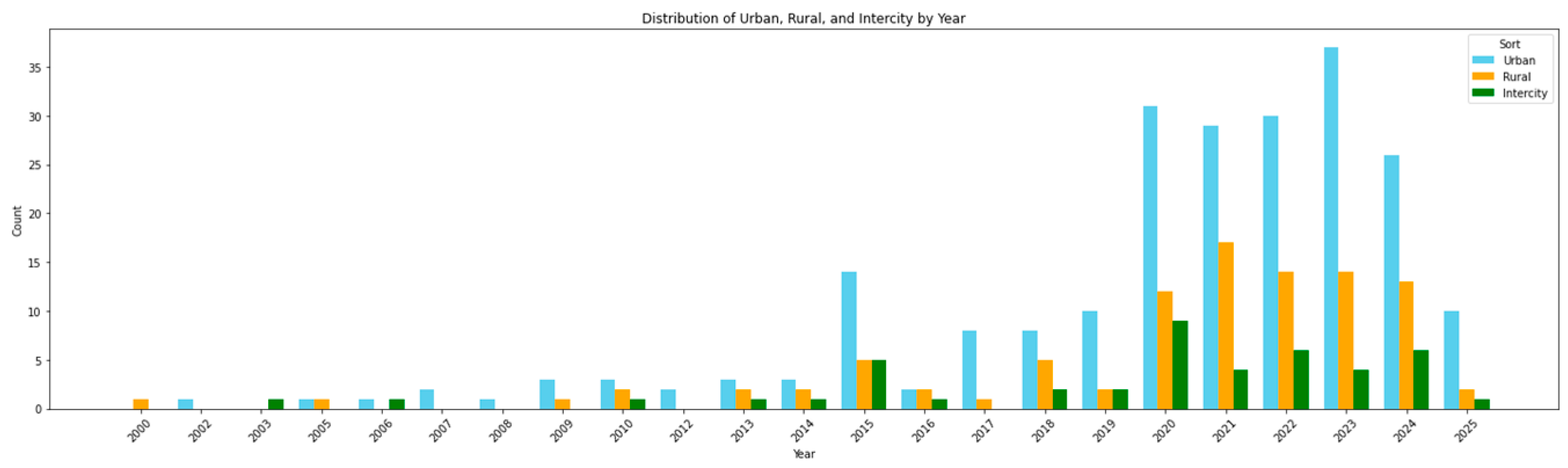

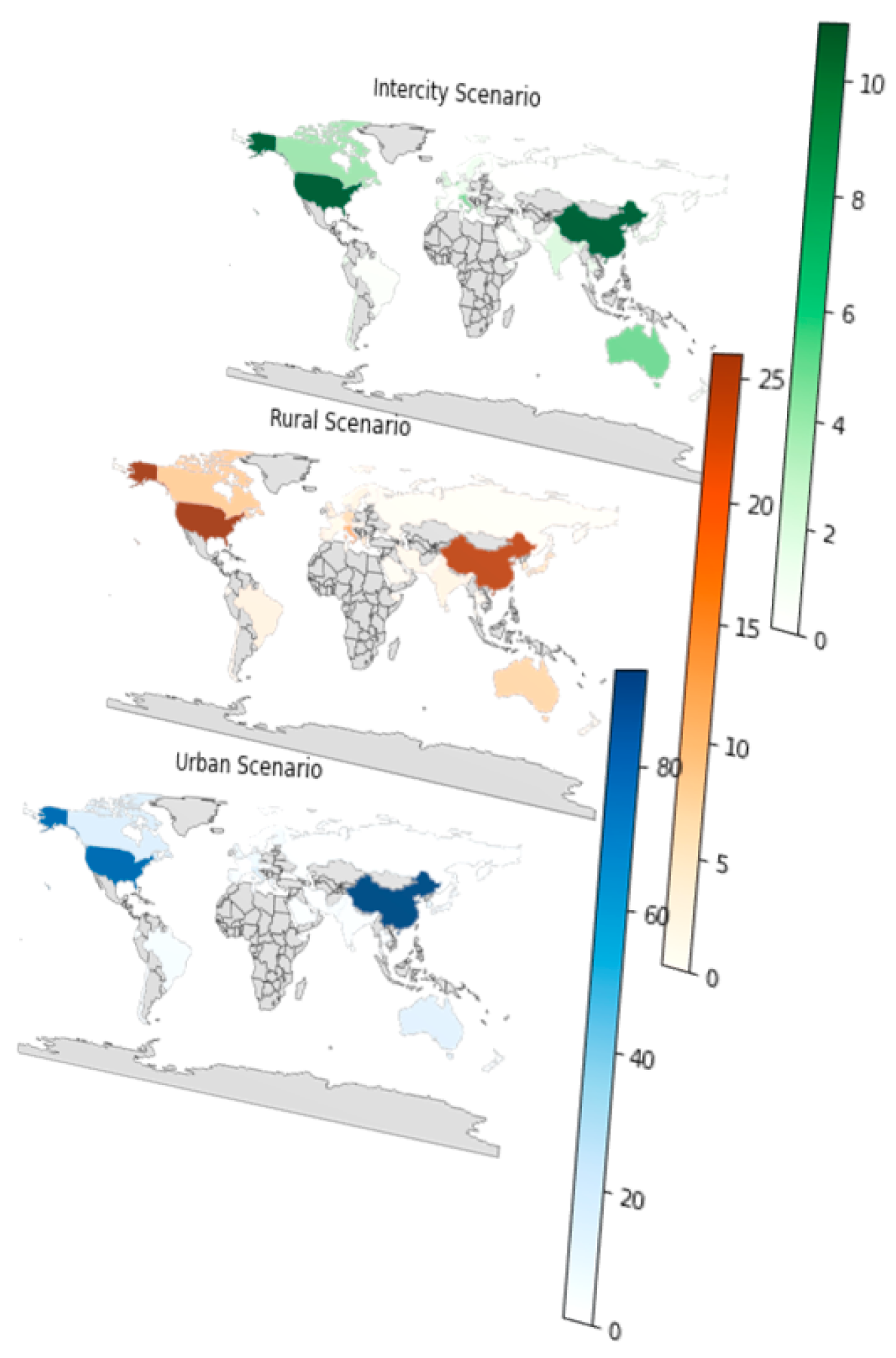

2. Data and Indicators

2.1. Data

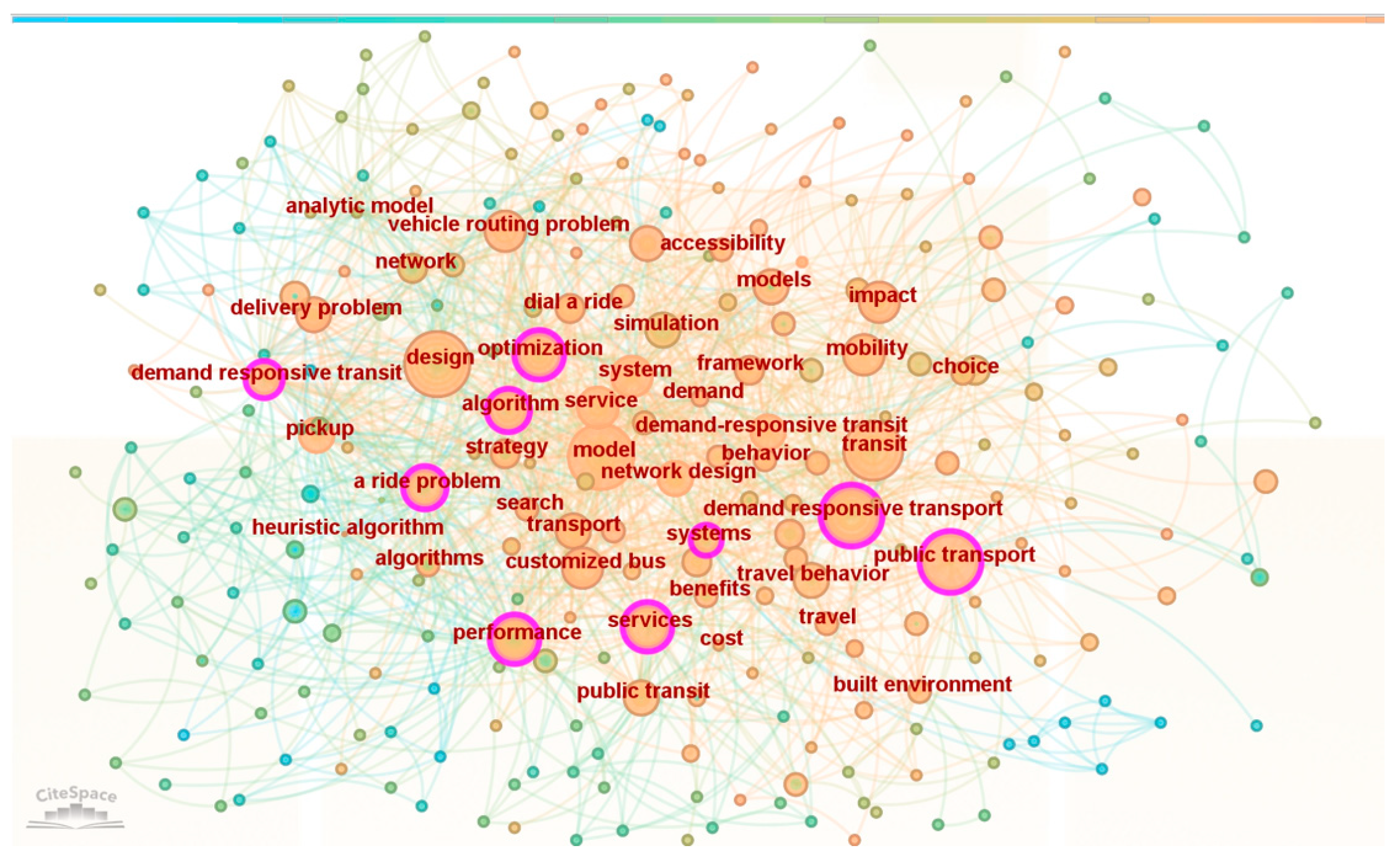

2.2. Indicators

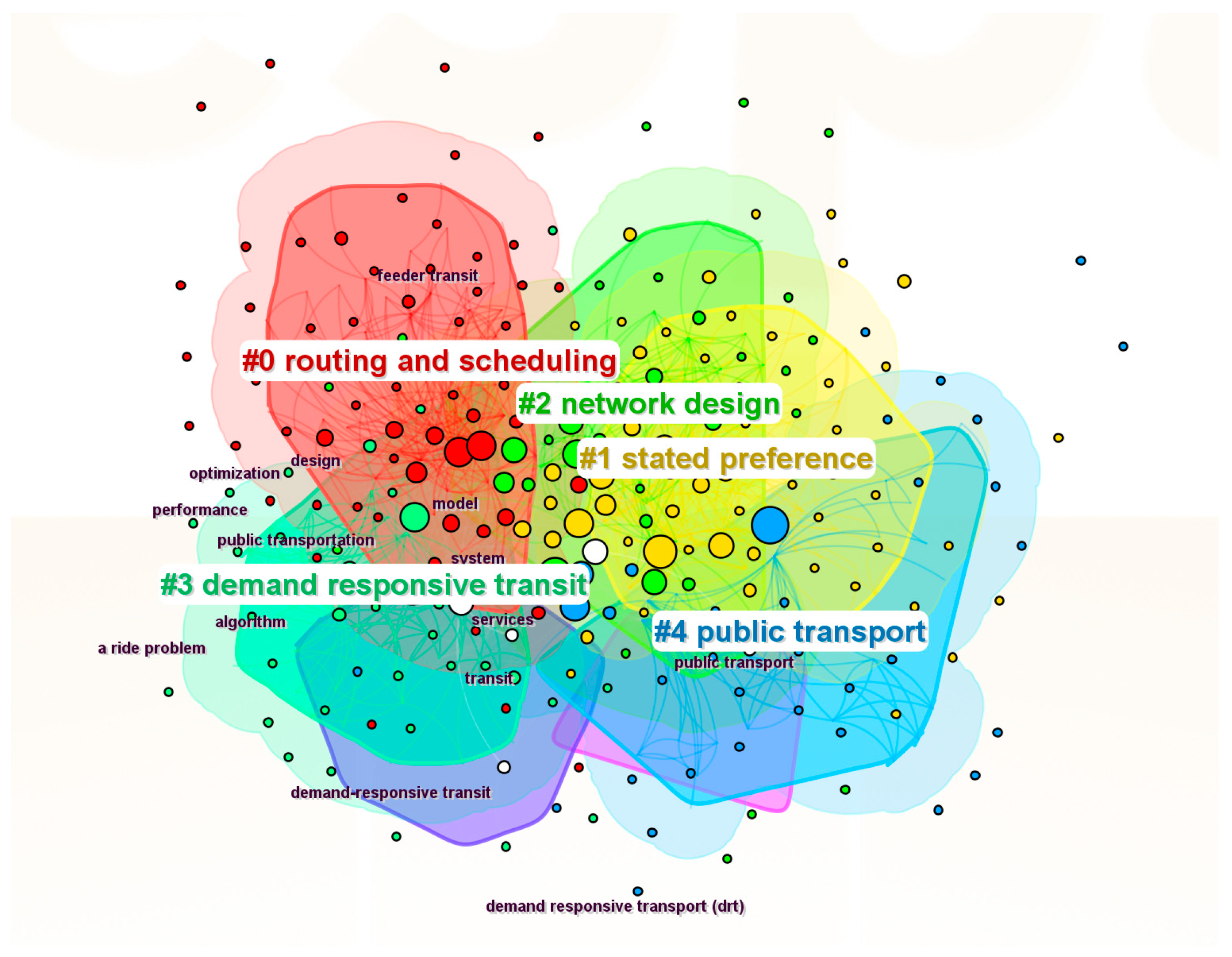

- Operational conditions, where clusters such as “stated preference” and keywords such as “mobility”, “public transit”, and “service” reflect demand estimation, fleet coordination, and infrastructure integration.

- Operational models, where clusters such as “routing and scheduling”, “network design”, and keywords such as “algorithm”, “optimization”, and “design” capture algorithmic control and simulation techniques.

- Operational outcomes, where clusters such as “demand-responsive transit” and “public transport” and keywords such as “systems”, “performance”, and “accessibility” emphasize accessibility, equity, and system resilience.

2.2.1. Operational Conditions

2.2.2. Operational Models

2.2.3. Operational Outcomes

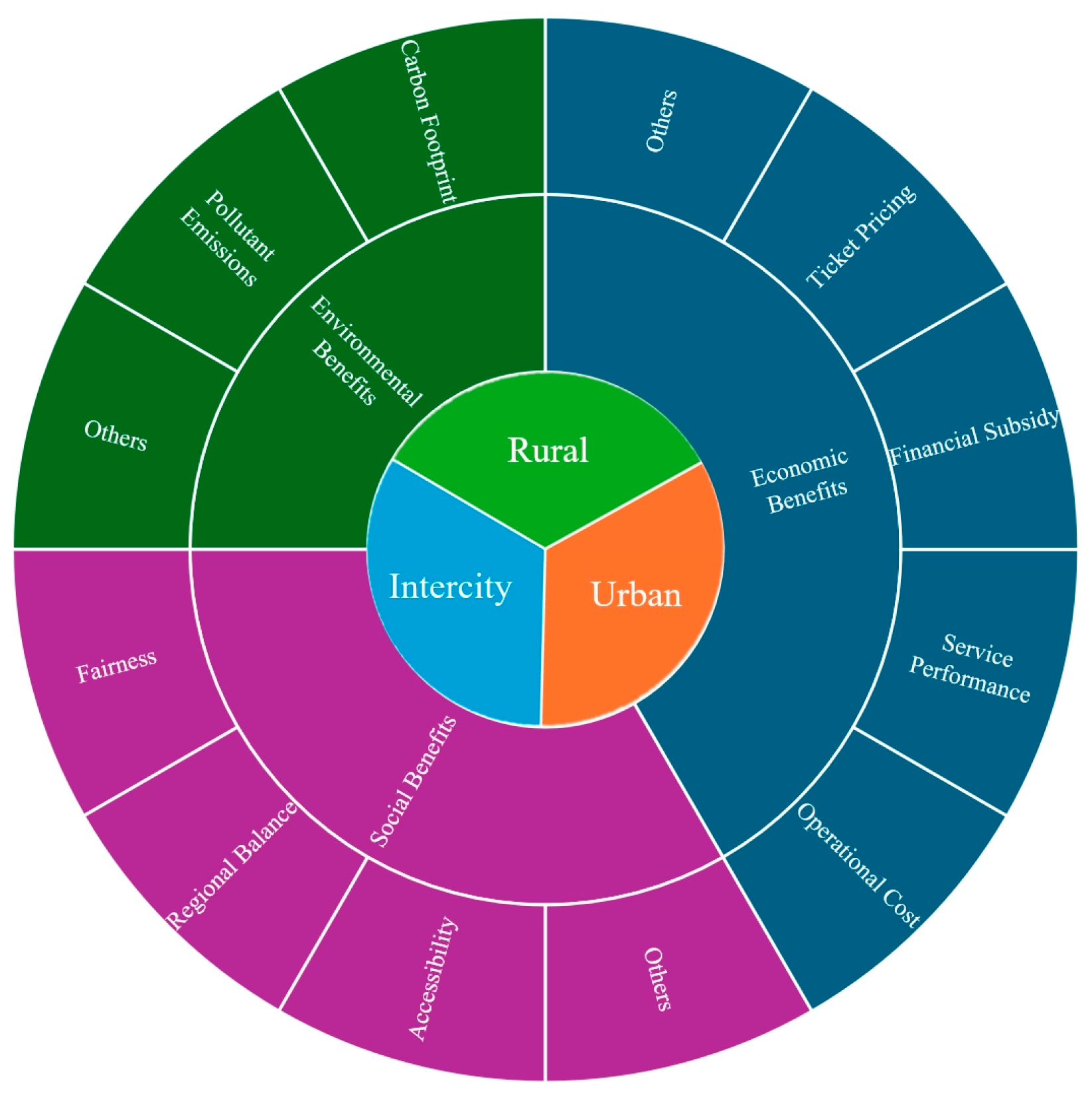

3. Scenarios

- Urban Scenarios. Indicators emphasize scheduling precision, passenger throughput, and multimodal integration, highlighting efficiency and coordination challenges in dense networks.

- Rural Scenarios. Indicators focus on cost-efficiency, service coverage, and resilience through shared passenger–freight operations, reflecting economic and social trade-offs in low-demand contexts.

- Intercity Scenarios. Indicators capture synchronization with multimodal nodes, travel time reliability, and systemic interdependencies, emphasizing connectivity and governance challenges across regions.

3.1. Urban Scenarios

3.2. Rural Scenarios

3.3. Intercity Scenarios

4. Discussion

5. Challenges

6. Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fu, X.; Zhang, J.; Chan, F.T.S. Determinants of Loyalty to Public Transit: A Model Integrating Satisfaction-Loyalty Theory and Expectation-Confirmation Theory. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2018, 113, 476–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flusberg, M. An Innovative Public Transportation System for a Small City: The Merrill, Wisconsin, Case Study; Transportation Research Record; Transportation Research Board: Washington, DC, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Daganzo, C.F. Approximate analytic model of many-to-many demand responsive transportation systems. Transp. Res. 1978, 12, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molenbruch, Y.; Braekers, K.; Caris, A. Typology and Literature Review for Dial-a-Ride Problems. Ann. Oper. Res. 2017, 259, 295–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, S.; Ho, C.; Hensher, D. Resurgence of Demand Responsive Transit Services—Insights from BRIDJ Trials in Inner West of Sydney, Australia. Res. Transp. Econ. 2020, 83, 100904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrel, A.L.; Mavrouli, S.M.; Natarajan, P.R.; Tarabay, R.; Broaddus, A. Greening the Commute: A Case Study of Demand for Employer-Sponsored Microtransit. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2024, 190, 104258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bing, X.; Li, Z.-C.; Fu, X. Optimization of Urban–Rural Bus Services with Shared Passenger-Freight Transport: Formulation and a Case Study. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2025, 192, 104355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imhof, S.; Frölicher, J.; Von Arx, W. Shared Autonomous Vehicles in Rural Public Transportation Systems. Res. Transp. Econ. 2020, 83, 100925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, R.; Yang, H.; Fan, W.; Wang, D. Optimizing Service Design for the Intercity Demand Responsive Transit System: Model, Algorithm, and Comparative Analysis. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 254, 124180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Gonzalez, M.J.; Liu, T.; Cats, O.; Van Oort, N.; Hoogendoorn, S. The Potential of Demand-Responsive Transport as a Complement to Public Transport: An Assessment Framework and an Empirical Evaluation. Transp. Res. Rec. 2018, 2672, 879–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.; Seshadri, R.; Azevedo, C.L.; Kumar, N.; Basak, K.; Ben-Akiva, M. Assessing the Impacts of Automated Mobility-on-Demand through Agent-Based Simulation: A Study of Singapore. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2020, 138, 367–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mageean, J.; Nelson, J.D. The Evaluation of Demand Responsive Transport Services in Europe. J. Transp. Geogr. 2003, 11, 255–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currie, G.; Fournier, N. Why Most DRT/Micro-Transits Fail—What the Survivors Tell Us about Progress. Res. Transp. Econ. 2020, 83, 100895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, J.; Wang, P.; Teng, J.; Loo, B.P.Y. Adaptability Analysis Methods of Demand Responsive Transit: A Review and Future Directions. Transp. Rev. 2023, 43, 676–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daganzo, C.E.; Ouyang, Y. A General Model of Demand-Responsive Transportation Services: From Taxi to Ridesharing to Dial-a-Ride. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2019, 126, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Li, C.; Wu, W.; Yang, Y. Exploring the Determinants of Demand-Responsive Transit Acceptance in China. Transp. Policy 2025, 165, 150–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vansteenwegen, P.; Melis, L.; Aktas, D.; Sorensen, K.; Vieira, F.S.; Montenegro, B.D.G. A Survey on Demand-Responsive Public Bus Systems. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2022, 137, 103573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soria, J.; Etzioni, S.; Shiftan, Y.; Ben-Elia, E.; Stathopoulos, A. Microtransit Adoption in the Wake of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Evidence from a Choice Experiment with Transit and Car Commuters. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2023, 157, 104395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khattak, A.; Yim, Y. Traveler Response to Innovative Personalized Demand-Responsive Transit in the San Francisco Bay Area. J. Urban Plan. Dev. ASCE 2004, 130, 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, A.; Dou, Z.; Qi, L.; Wang, L. Flexible Route Optimization for Demand-Responsive Public Transit Service. J. Transp. Eng. Part A Syst. 2020, 146, 04020132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, K.; Dessoulcy, M.; Zhou, Z. Factors Influencing Productivity and Operating Cost of Demand Responsive Transit. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2008, 42, 503–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lao, X.; Shen, Y.; Cao, J.; Ji, Y.; Du, Y. Does Implicit Attitude Affect Travel Mode Choice Behaviors? A Study of Customized Bus Attraction to Urban Railway Riders. Transp. Lett. Int. J. Transp. Res. 2025, 17, 1399–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yamamoto, T.; Liu, K. Key Determinants and Heterogeneous Frailties in Passenger Loyalty toward Customized Buses: An Empirical Investigation of the Subscription Termination Hazard of Users. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2020, 115, 102636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallaro, F.; Nocera, S. Integration of Passenger and Freight Transport: A Concept-Centric Literature Review. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2022, 43, 100718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buerstlein, J.; Lopez, D.; Farooq, B. Exploring First-Mile on-Demand Transit Solutions for North American Suburbia: A Case Study of Markham, Canada. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2021, 153, 261–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danilevičius, A.; Karpenko, M.; Křivánek, V. Research on the Noise Pollution from Different Vehicle Categories in the Urban Area. Transport 2023, 38, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Jin, J.G.; Wu, J.; Jiang, X. Optimizing Passenger Flow Control and Bus-Bridging Service for Commuting Metro Lines. Comput. Aided Civil. Eng. 2017, 32, 458–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostovasili, M.; Kanellopoulos, J.; Amditis, A. Integrated Passenger and Freight Transport: Seamless Door-to-Door Mobility and Optimal Use of Resources. In Transport Transitions: Advancing Sustainable and Inclusive Mobility; McNally, C., Carroll, P., Martinez-Pastor, B., Ghosh, B., Efthymiou, M., Valantasis-Kanellos, N., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 569–575. [Google Scholar]

- Pimentel, C.; Alvelos, F. Integrated Urban Freight Logistics Combining Passenger and Freight Flows—Mathematical Model Proposal. Transp. Res. Procedia 2018, 30, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Chen, X.; Potoglou, D.; Tian, M.; Fu, Y. Travel Impedance, the Built Environment, and Customized-Bus Ridership: A Stop-to-Stop Level Analysis. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2023, 122, 103889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, K.; Yamamoto, T.; Wang, D.; Lu, G. Built Environment as a Precondition for Demand-Responsive Transit (DRT) System Survival: Evidence from an Empirical Study. Travel Behav. Soc. 2023, 30, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Yang, M.; Wang, L.; Zhang, M.; Lei, D. Static and Dynamic Scheduling Method of Demand-Responsive Feeder Transit for High-Speed Railway Hub Area. J. Transp. Eng. Part A Syst. 2023, 149, 4023113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grahn, R.; Qian, S.; Hendrickson, C. Optimizing First- and Last-Mile Public Transit Services Leveraging Transportation Network Companies (TNC). Transportation 2023, 50, 2049–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rich, J. Let’s Walk! The Fallacy of Urban First- and Last-Mile Public Transport. Transportation 2024, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, R. Dynamic Scheduling of Flexible Bus Services with Hybrid Requests and Fairness: Heuristics-Guided Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning with Imitation Learning. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2024, 190, 103069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, B.; Leung, A.; Willcox, J. The Tale of Two Networks: Leveraging Digital Twin Inspired Simulations to Enhance on-Demand Transit Services. Transp. Plan. Technol. 2025, 48, 1530–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hu, Z.; Huang, H.; Lu, Z.; Wen, X. Optimization for Customized Bus Stop Planning, Order Schedule, and Routing Design in On-Demand Urban Mobility. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 10239–10251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Liu, Z. Terminal-Based Zonal Bus: A Novel Flexible Transit System Design and Implementation. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 238, 121793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Cen, X.; Lo, H.K. Zonal-Based Flexible Bus Service under Elastic Stochastic Demand. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2021, 152, 102367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Wei, G.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Guo, H. Optimizing Multi-Vehicle Demand-Responsive Bus Dispatching: A Real-Time Reservation-Based Approach. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Luo, S.; Zu, A.; Ji, H.; Kang, L.; Shao, C. Optimal Design of Fixed-Route and Demand-Responsive Transit with a Dynamic Stop Strategy. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2025, 199, 104581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chien, S.; Wirasinghe, S.C.; Kattan, L. Joint Optimization of Zone Area and Headway for Demand Responsive Transit Service under Heterogeneous Environment. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2022, 26, 3031–3042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Han, B.; Yang, R.; Zhao, P. Integrated Optimization of Stop Planning and Timetabling for Demand-Responsive Transport in High-Speed Railways. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corazza, M.V.; D’Eramo, S. Designing Transportation for Women: Night Paratransit Service for the Female Community of Sapienza University of Rome. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2025, 29, 101328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Levy, J.; Schonfeld, P. Optimal Zone Sizes and Headways for Flexible-Route Bus Services. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2019, 130, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Correia, G.H.D.A.; Van Arem, B. Optimizing the Service Area and Trip Selection of an Electric Automated Taxi System Used for the Last Mile of Train Trips. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2016, 93, 115–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.; Seshadri, R.; Le, D.-T.; Zegras, P.C.; Ben-Akiva, M.E. Evaluating Automated Demand Responsive Transit Using Microsimulation. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 82551–82561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, S.; Kim, H.; Lee, J. Combining Reinforcement Learning With Genetic Algorithm for Many-To-Many Route Optimization of Autonomous Vehicles. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 26931–26942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rich, J.; Seshadri, R.; Jomeh, A.J.; Clausen, S.R. Fixed Routing or Demand-Responsive? Agent-Based Modelling of Autonomous First and Last Mile Services in Light-Rail Systems. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2023, 173, 103676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghestani, A.; Najafabadi, S.; Salem, A.; Jiang, Z.; Tayarani, M.; Gao, O. An Application of the Node–Place Model to Explore the Land Use–Transport Development Dynamics of the I-287 Corridor. Urban Sci. 2023, 7, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpenko, M.; Prentkovskis, O.; Skačkauskas, P. Analysing the Impact of Electric Kick-Scooters on Drivers: Vibration and Frequency Transmission during the Ride on Different Types of Urban Pavements. Eksploat. I Niezawodn.–Maint. Reliab. 2025, 27, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, L.; Charles, P.; Tether, C. Evaluating Flexible Transport Solutions. Transp. Plan. Technol. 2007, 30, 249–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caulfield, B. Estimating the Environmental Benefits of Ride-Sharing: A Case Study of Dublin. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2009, 14, 527–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Araldo, A.; El Yacoubi, M. Planning Demand-Responsive Transit to Reduce Inequality of Accessibility. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2025, 199, 104544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, H.; Yu, B.; Liu, X. Optimizing Bus Bridging Services with Mode Choice in Response to Urban Rail Transit Emergencies. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2025, 323, 108–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotval-K, Z.; Wilkinson, A.; Brush, A.; Kassens-Noor, E. Impacts of Local Transit Systems on Vulnerable Populations in Michigan. Urban Sci. 2023, 7, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaičiūtė, K.; Katinienė, A.; Bureika, G. The Synergy between Technological Development and Logistic Cooperation of Road Transport Companies. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaMondia, J.; Bhat, C. Development of a Microsimulation Analysis Tool for Paratransit Patron Accessibility in Small and Medium Communities. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2010, 2174, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, R.; Mulley, C. Flexible Transport Services: Overcoming Barriers to Implementation in Low-Density Urban Areas. Urban Policy Res. 2012, 30, 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, R.; de Sousa, J.P.; Dias, T.G. Sustainable Demand Responsive Transportation Systems in a Context of Austerity: The Case of a Portuguese City. Res. Transp. Econ. 2015, 51, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capodici, A.E.; D’Angelo, R.; D’Orso, G.; Migliore, M. Demand Responsive Transport Services for Improving the Public Transport in Suburban Areas. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Environment and Electrical Engineering and 2022 IEEE Industrial and Commercial Power Systems Europe (Eeeic/I&Cps Europe), IEEE, Prague, Czech Republic, 28 June–1 July 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Sörensen, L.; Bossert, A.; Jokinen, J.-P.; Schlüter, J. How Much Flexibility Does Rural Public Transport Need?—Implications from a Fully Flexible DRT System. Transp. Policy 2021, 100, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronsvoort, K.; Alonso-Gonzalez, M.; Van Oort, N.; Molin, E.; Hoogendoorn, S. Preferences toward Bus Alternatives in Rural Areas of the Netherlands: A Stated Choice Experiment. Transp. Res. Rec. 2021, 2675, 524–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruzzone, F.; Scorrano, M.; Nocera, S. The Combination of E-Bike-Sharing and Demand-Responsive Transport Systems in Rural Areas: A Case Study of Velenje. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2021, 40, 100570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loyola, M.; Nelson, J.D. Flexible and Local: Understanding How on-Demand Transport Serves Rural Communities. Transp. Plan. Technol. 2024, 48, 1506–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davison, L.; Enoch, M.; Ryley, T.; Quddus, M.; Wang, C. A Survey of Demand Responsive Transport in Great Britain. Transp. Policy 2014, 31, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrada, J.; Poulhes, A. Economic and Socioeconomic Assessment of Replacing Conventional Public Transit with Demand Responsive Transit Services in Low-to-Medium Density Areas. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2021, 150, 317–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brake, J.; Nelson, J.D. A Case Study of Flexible Solutions to Transport Demand in a Deregulated Environment. J. Transp. Geogr. 2007, 15, 262–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallaro, F.; Nocera, S. Flexible-Route Integrated Passenger–Freight Transport in Rural Areas. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2023, 169, 103604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruzzone, F.; Cavallaro, F.; Nocera, S. The Integration of Passenger and Freight Transport for First-Last Mile Operations. Transp. Policy 2021, 100, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Yang, S.; An, K.; Ma, W. Operation Strategy Analysis for the Passenger and Freight Shared Transportation System. npj. Sustain. Mobil. Transp. 2025, 2, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Sun, Q.; Tang, Y. Demand-Responsive Transport Dynamic Scheduling Optimization Based on Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning Under Mixed Demand. In Proceedings of the Artificial Neural Networks and Machine Learning—ICANN 2024, Lugano, Switzerland, 17–20 September 2024; Wand, M., Malinovská, K., Schmidhuber, J., Tetko, I.V., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 356–368. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, A. “Crown Shyness” in Intercity Airport Shuttle Services: A Spatial Econometric Analysis of the Yangtze River Delta Airport Cluster. J. Transp. Geogr. 2025, 124, 104180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobruszkes, F.; Lennert, M.; Van Hamme, G. An Analysis of the Determinants of Air Traffic Volume for European Metropolitan Areas. J. Transp. Geogr. 2011, 19, 755–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Lee, E.; Lo, H.K. Offline Planning and Online Operation of Zonal-Based Flexible Transit Service under Demand Uncertainties and Dynamic Cancellations. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2024, 168, 104715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quadrifoglio, L.; Hall, R.W.; Dessouky, M.M. Performance and Design of Mobility Allowance Shuttle Transit Services: Bounds on the Maximum Longitudinal Velocity. Transp. Sci. 2006, 40, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceder, A. (Avi) Integrated Smart Feeder/Shuttle Transit Service: Simulation of New Routing Strategies. J. Adv. Transp. 2013, 47, 595–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cats, O.; Haverkamp, J. Strategic Planning and Prospects of Rail-Bound Demand Responsive Transit. Transp. Res. Rec. 2018, 2672, 404–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Fan, H.S.L. A New Computational Model for the Design of an Urban Inter-Modal Public Transit Network. Comput.-Aided Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 2007, 22, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Quddus, M.; Enoch, M.; Ryley, T.; Davison, L. Multilevel Modelling of Demand Responsive Transport (DRT) Trips in Greater Manchester Based on Area-Wide Socio-Economic Data. Transportation 2014, 41, 589–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferro, P.S.; Behrens, R. From Direct to Trunk-and-Feeder Public Transport Services in the Urban South: Territorial Implications. J. Transp. Land Use 2015, 8, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyravi, B.; Peleckienė, V.; Vaičiūtė, K. Research on the Impact of Motorization Rate and Technological Development on Climate Change in Lithuania in the Context of the European Green Deal. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djavadian, S.; Chow, J.Y.J. An Agent-Based Day-to-Day Adjustment Process for Modeling ‘Mobility as a Service’ with a Two-Sided Flexible Transport Market. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2017, 104, 36–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campisi, T.; Garau, C.; Acampa, G.; Maltinti, F.; Canale, A.; Coni, M. Developing Flexible Mobility On-Demand in the Era of Mobility as a Service: An Overview of the Italian Context Before and After Pandemic. In Proceedings of the Computational Science and Its Applications, ICCSA 2021, PT VI, Cagliari, Italy, 13–16 September 2021; Gervasi, O., Murgante, B., Misra, S., Garau, C., Blecic, I., Taniar, D., Apduhan, B., Rocha, A., Tarantino, E., Torre, C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 12954, pp. 323–338. [Google Scholar]

- Calabro, G.; Le Pira, M.; Giuffrida, N.; Inturri, G.; Ignaccolo, M.; Correia, G.H. de A. Fixed-Route vs. Demand-Responsive Transport Feeder Services: An Exploratory Study Using an Agent-Based Model. J. Adv. Transp. 2022, 2022, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inturri, G.; Giuffrida, N.; Ignaccolo, M.; Le Pira, M.; Pluchino, A.; Rapisarda, A.; D’Angelo, R. Taxi vs. Demand Responsive Shared Transport Systems: An Agent-Based Simulation Approach. Transp. Policy 2021, 103, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhao, X. Machine Learning Approach for Spatial Modeling of Ride sourcing Demand. J. Transp. Geogr. 2022, 100, 103310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, B.; Brickwedde, C.; Lienkamp, M. Multi-Agent Simulation of a Demand-Responsive Transit System Operated by Autonomous Vehicles. Transp. Res. Rec. 2018, 2672, 764–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Country | Policy Characteristics | Examples | Implications for DRT Sustainability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Germany | Strong Government Subsidies; Rural Service Support | Federal and State Subsidies for Rural DRT (e.g., “Bürgerbus” programs) | Continuity in Low-demand Areas; Stable Long-term Viability |

| France | National and Regional Subsidies; Integration with Public Transport | Regional Councils Subsidize; DRT Services Linked to Rail/Bus Networks | Promotes Multimodal Integration; Accessibility in Peripheral Regions |

| United States | Market-driven; Private Sector Innovation; Flexible Local Regulation | Via, Uber Pilots in >300 Cities; Local Governments Provide Regulatory Flexibility | Rapid Innovation and Expansion; Depends on Private Investment; Unstable Long-term Viability |

| Canada | Municipal-level Support; Emphasis on Rural Accessibility | Ontario and Quebec Rural DRT Pilots with Municipal Funding | Continuity in Low-demand Areas; Limited Scalability without Subsidies |

| China | Government-led Pilots; Integration with Smart City Initiatives | Beijing, Shenzhen DRT Pilots; Subsidies for Technology-Driven Services | Strong Public Investment; Potential for Large-scale Deployment |

| South Korea | Hybrid Model; Smart City and AI-driven Pilots | Seoul “Smart DRT” Projects; Integration with MaaS Platforms | Balances Efficiency and Inclusivity; Strong Technology Orientation |

| Malaysia | Public–private Collaboration; Technology-driven Pilots | Asia Mobility Project Integrating DRT with MaaS | Expands Coverage in Multi-area; Rapid Innovation and Expansion |

| Source | Factor | Objective | Real-Time Performance | Route | Scenes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wu et al. [35] | Fleet Size | Realize the dynamic scheduling of fault risk perception | Reservation Request + Immediate Request | Semi-flexible | Guangzhou Higher Education Mega Center, Guangdong province, China |

| Kaufman et al. [36] | Routing Design | Improve efficiency and fairness | Immediate Request | Semi-flexible | Experimental Simulation |

| Wang et al. [37] | Stop Planning | Improve service coverage and reduce detours | Immediate Request | Flexible | San Francisco |

| Wang et al. [38] | Routing Design | Make a trade-off between realizing route flexibility and curtailing excessive costs | Immediate Request | Semi-flexible | Xiong An, Hebei province, China |

| Lee et al. [39] | Routing Design | Divide the service area into zones to maximize the profit and minimize the detour time cost | Reservation Request + Immediate Request | Flexible | Chengdu, China |

| Zhou et al. [40] | Fleet Size | Optimizes the vehicle scheduling problem at a single time point | Immediate request | Flexible | Experimental Simulation |

| Zhang et al. [41] | Feeder Modes Combination | Pedestrian-friendly | Reservation Request + Immediate Request | Flexible +fixed | Experimental Simulation |

| Wang et al. [42] | Service Zone Identification | Minimize the average cost through optimizing service zone areas and associated headways | Immediate Request | Flexible | City of Calgary, Canada |

| Li et al. [43] | Integrated Optimization | Combine DRT’s strategy with high-speed railway timetabling | Reservation Request + Immediate Request | Flexible | Experimental Simulation |

| Corazza et al. [44] | Operating Period | Analyzes the Sapienza Women’s stated preferences to design a women-reserved night service | Reservation Request | Flexible | Sapienza’s Main Campus, Rome, Italy |

| Kim et al. [45] | Service Zone Size | Optimize headway and service zone size | Immediate Request | Semi-flexible | Experimental Simulation |

| Key Factor | Description | Challenges | Strategies | Case Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Built Environment | Impact of proximity to fixed-route infrastructure | Dispersed population patterns | Flexible stop placement | Brownsville, Texas |

| Policy Support | Role of policy incentives in DRT viability | Limited financial subsidies | Policy frameworks and institutional support | New South Wales, Australia |

| Demand Density | Influence of low population density on DRT demand | Limited access to conventional transit | Passenger–freight integration | Velenje, Slovenia |

| Operational Focus | Emphasis on stop coverage and timing | Economic constraints | Cost efficiency and convenience | Moree, Australia |

| Economic and Social Benefits | Prioritization of social benefits over profit | Insufficient funding for conventional transit | Enhancing social inclusion and accessibility | Northumberland, England |

| Scenario | Urban | Rural | Intercity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Operation Conditions | Similarities | Built Environment, Passenger Arrival Distribution, Demand Density | ||

| Differences | Financial Subsidy, Information Technologies, Shape of Service Areas | Legislative, Financial Subsidy, Shape of Service Areas | Information Technologies | |

| Operation Models | Similarities | Fleet Size, Time Schedule, Routing Design | ||

| Differences | Service Area, Stop Planning, Vehicle Capacity, Travelling Speed | Stop Planning | Vehicle Capacity | |

| Operation Outcomes | Similarities | Operational Cost, Environmental Cost | ||

| Differences | Service Performance, Funding Sources, Fare, Transport Equity, Personalized Mobility | Funding Sources, Transport Equity | Personalized Mobility | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Y.; Gao, L.; Zhao, X.; Ni, A. Data-Driven Modeling of Demand-Responsive Transit: Evaluating Sustainability Across Urban, Rural, and Intercity Scenarios. Systems 2025, 13, 1080. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13121080

Zhang Y, Gao L, Zhao X, Ni A. Data-Driven Modeling of Demand-Responsive Transit: Evaluating Sustainability Across Urban, Rural, and Intercity Scenarios. Systems. 2025; 13(12):1080. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13121080

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Yunxi, Linjie Gao, Xu Zhao, and Anning Ni. 2025. "Data-Driven Modeling of Demand-Responsive Transit: Evaluating Sustainability Across Urban, Rural, and Intercity Scenarios" Systems 13, no. 12: 1080. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13121080

APA StyleZhang, Y., Gao, L., Zhao, X., & Ni, A. (2025). Data-Driven Modeling of Demand-Responsive Transit: Evaluating Sustainability Across Urban, Rural, and Intercity Scenarios. Systems, 13(12), 1080. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13121080