Abstract

This study presents the design and evaluation of a multi-model artificial intelligence (AI) framework for proactive quality risk management in projects. A dataset comprising 2000 risk records was developed, containing four columns: Risk Description (input), Risk Category, Trigger, and Impact (outputs). Each output variable was modeled using three independent classifiers, forming a multi-step decision-making pipeline where one input is processed by multiple specialized models. Two feature extraction techniques, Term Frequency–Inverse Document Frequency (TF-IDF) and GloVe100 Word Embeddings, were compared in combination with several machine learning algorithms, including Logistic Regression, Support Vector Machines (SVMs), Random Forest, Multinomial Naive Bayes, and XGBoost. Results showed that model performance varied with task complexity and the number of output classes. Trigger prediction (28 classes), Logistic Regression, and SVM achieved the best performance, with a macro-average F1-score of 0.75, while XGBoost with TF-IDF features produced the highest accuracy for Risk Category classification (five classes). In Impact prediction (15 classes), SVM with Word Embeddings demonstrated superior results. The implementation, conducted in Python (v3.9.12, Anaconda), utilized Scikit-learn, XGBoost, SHAP, and Gensim libraries. SHAP visualizations and confusion matrices enhanced model interpretability. The proposed framework contributes to scalable, text-based, predictive, quality risk management, supporting real-time project decision-making.

1. Introduction

Risk management is considered a pillar of achieving project success across all industries because it is a process that helps teams predict potential challenges and take preventive measures to reduce disruptions. The traditional approach of addressing problems once they occur is no longer practical, especially as modern projects become more complex, with increased interdependencies and higher quality expectations [].

This situation has driven organizations to adopt predictive and data-driven risk management methods that go beyond reactive strategies.

The potential of artificial intelligence (AI) and Natural Language Processing (NLP) to detect hidden risk patterns is underlined by some transformative solutions for unstructured project documentation [].

Although AI and machine learning have proven successful in fields like healthcare, finance, and cybersecurity, their potential for predictive project risk management remains underdeveloped [].

In recent years, many scholars have focused on identifying risks using single-label or categorical models, but this approach fails to capture the multidimensional nature of project risks. Consequently, it is necessary to use a multi-label or multi-output modeling framework to interconnect different dimensions that generate risks []. Thus, this study proposes an automated risk detection and multi-classification framework based on NLP to systematically identify Risk Categories, Triggers, and Impacts from textual descriptions and to provide a more comprehensive view of project risk analysis.

Our research will focus on analyzing the complexity of real-world project data and on providing a decision-support system to enhance predictive accuracy, scalability, and interpretability in project risk management.

Within this context, the present study focuses on applying AI and NLP techniques to risk documentation to develop a decision-support framework that systematically identifies Risk Categories, Triggers, and Impacts solely from textual risk descriptions. By doing so, the research aims to transform how organizations handle risk information, moving from manual reviews to automated, evidence-based systems that support real-time decision-making.

1.1. Artificial Intelligence in Project Management

Artificial intelligence has become a disruptive force in project management processes and organizations, especially in project planning, performance monitoring, and execution. It provides organizations with more effective ways to manage complex projects. AI-based technology has undergone numerous advancements in computational intelligence, enabling it to learn and suggest actions, enhance judgment accuracy, and improve other operational aspects []. The risks can be better identified by reducing the passive evaluation and by enhancing proactive risk management, which entails anticipating and reducing risks before they become more serious, which are additional uses of AI in project management []. Because it gives decision-makers the ability to precisely manage the organization’s and its environment’s uncertainty, artificial intelligence (AI) is now regarded as a critical asset rather than an auxiliary one, giving projects resilience []. The specialization of AI applications is necessary to create adaptable and dynamic management systems.

The use of AI in the construction sector has skyrocketed due to long-running delays, cost escalations, and accident cases. According to the latest bibliometric analyses, it becomes clear that the application of machine learning (ML), Natural Language Processing (NLP), Knowledge-Based Reasoning (KBR), Optimization Algorithms (OAs), and Computer Vision (CV) has become popular for improving risk management practices [,]. For example, delays in construction have been predicted using ML-based models, and safety compliance is being monitored in real time with the help of image and video analytics by CV systems []. At the same time, NLP enables project managers to extract useful information from unstructured data, including project reports, contracts, and safety logs, thereby overcoming information overload []. All these applications highlight the benefits of AI in optimizing procurement, workforce coordination, and decision-making in construction project delivery frameworks []. In addition to construction, AI-powered models have great potential in large-scale infrastructures, where network effects between multiple stakeholders and financial interdependencies require predictive management [,]. Chen et al. [] observed that Gradient Boosting Decision Trees (GBDTs) and Principal Component Analysis (PCA) have the potential to reduce project costs by 12.4 per cent and achieved an 87.3 per cent accuracy in early risk prediction. Therefore, we believe that AI can be used at both the micro and macro levels in solving conflicts between stakeholders or in predicting environmental challenges [].

1.2. Sector-Specific Applications of AI in Risk Management

The use of AI in the construction sector has expanded rapidly due to ongoing delays, rising costs, and safety incidents. According to recent bibliometric analyses, it is clear that the application of machine learning (ML), Natural Language Processing (NLP), Knowledge-Based Reasoning (KBR), Optimization Algorithms (OA), and Computer Vision (CV) has become popular for enhancing risk management practices [,]. For example, ML-based models have been used to predict construction delays, while safety compliance is monitored in real-time through image and video analytics by CV systems []. Simultaneously, NLP enables project managers to extract valuable information from unstructured data such as project reports, contracts, and safety logs, helping to mitigate information overload []. These applications demonstrate the benefit of AI in optimizing procurement, workforce coordination, and decision-making within construction project delivery frameworks []. Beyond construction, AI-powered models hold significant potential for large-scale infrastructure projects, where network effects among multiple stakeholders and financial interdependencies require predictive management [,]. Chen et al. [] demonstrated that Gradient Boosting Decision Trees (GBDTs) and Principal Component Analysis (PCA) reduced project costs by 12.4 per cent and achieved an accuracy of 87.3 per cent in early risk prediction. These findings demonstrate how AI can be effectively applied at the macro level, such as in managing urban traffic, environmental forecasting, and resolving conflicts among stakeholders [].

1.3. Predictive Analytics and Risk Management

AI-driven predictive analytics is used in analyzing risk management within open innovation systems [] and is predominantly used in sectors under a high degree of uncertainty (e.g., healthcare) [].

It has been shown that ML and NLP methods can improve early risk detection, optimize resource allocation, and facilitate data-driven decision-making in complex, multi-stakeholder environments []. Cross-organizational risks, particularly those affecting open innovation projects, are complex and involve numerous stakeholders.

NPL techniques are used as strategic forecasting [] and for their potential to identify collaboration-related risks at an early stage [].

The uncertainty in collaborative projects has been reduced, even though the implementation of AI-based solutions is still in its early stages [].

Most organizations lack the knowledge or systems necessary to fully operationalize advanced AI tools for risk management in their projects, even in other organizations where these tools have been implemented successfully []. ML algorithms (e.g., Gradient Boosting, Random Forests, and Support Vector Machines (SVMs) were used to solve some organizational challenges [].

In the healthcare sector, the Gradient Boosting Machines generated a 15% improvement in operational efficiency by predicting both patient flow and staffing needs []. Moreover, AI models have been employed to anticipate cybersecurity vulnerabilities in IT projects, enabling proactive mitigation [].

Despite these advantages, concerns related to transparency, data management, and algorithm bias persist. To build accountability and stakeholder trust, explainable AI (XAI) methods are increasingly emphasized [].

Overall, this body of literature highlights a growing yet fragmented research area in which explainable, domain-specific models are essential to ensure the trustworthiness of AI-based risk management.

AI-based risk management has evolved in several sectors to become an integral part of project governance. Some of the most recent trends are linked to the implementation of simulation-based modeling, NLP-based knowledge extraction, and explainable AI solutions, with the latter contributing to an improvement in transparency in AI-based decisions, their accuracy, and the trust that stakeholders have in AI-based decision-making. The literature suggests that implementation challenges remain a major impediment, especially concerning the quality of data, governance models, and labor readiness. Nevertheless, AI technologies are also established as a source of resilience and creation in the modern project environment.

1.4. NLP in Risk Analysis

Natural Language Processing (NLP) is perceived as a disruptive technology in project risk analysis, enabling the extraction of structured information from large amounts of unstructured data, such as reports, communications, and contracts, at scale [,]. Conventional risk evaluation procedures may be based on manual reviews, which are time-consuming and subject to subjectivity.

On the other hand, NLP methods (e.g., text mining, topic modeling, and semantic analysis) enable the automatic identification of risk-related information []. NLP-based topic modeling with a Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) algorithm has identified recurrent patterns of risks in the construction industry, including cost overruns, safety issues, and resource allocation challenges []. These results are confirmed by experts in the domain []. Supervised classification and sentiment analysis have been applied in an industrial environment by other researchers, who achieved more than 90 per cent accuracy in risk identification [,]. Automated contract review has also been developed as part of NLP, in which techniques such as Named Entity Recognition (NER) and semantic similarity modeling have identified clauses that are risky either legally or financially, including clauses related to liability or penalties []. Recent advances in deep learning have included transformer models, such as BERT and RoBERTa, which currently achieve the highest performance in identifying risk-related patterns and sentiments []. Further fine-tuning of domains has also been demonstrated to increase accuracy in specialized domains, such as energy and infrastructure, by learning context-specific terms [].

Our findings contribute to improving the research. However, some gaps need to be closed in the future, such as the lack of models that simultaneously address multiple risk dimensions (e.g., Category, Trigger, and Impact), the scarcity of annotated datasets for text-based project risk classification, and also a lack of evaluations realized in comparison with the other project management frameworks. Furthermore, deep models can be highly accurate, but are usually black boxes, which spurs the desire to study interpretable NLP to gain trust and transparency [,].

1.5. Conceptual Frameworks and Governance in AI-Based Risk Management

Industry 4.0 can benefit from the implementation of AI within governance structures. Orthodox governance systems are often unable to cope with the dynamics of autonomous and algorithmic decision-making []. Algorithms and validation of continuous monitoring: A combination of algorithmic regulation, validation, and continuous monitoring is becoming increasingly recommended in high-risk sectors, including construction, finance, and healthcare [,]. Explainable AI (XAI) has become an essential component of governance, helping to overcome the issue of obscurity in ML algorithms and enhance accountability []. To guarantee ethical and legal adherence, regulators and organizations are creating certification systems and internal AI control committees []. Based on this premise, scholars have investigated the transformative value of AI in automating project management tasks. Adamantiadou and Tsironis [] show the role of intelligent agents and predictive models in improving the efficiency and flexibility of a workflow.

Nevertheless, transparency, ethical aspects, and human–AI cooperation remain problematic. For further research, it would be relevant to proceed with a multi-stakeholder approach to implement the application of AI [] successfully. Altogether, although the literature indicates significant progress in AI- and NLP-based risk management, it also reveals the fragmentation of fields and a lack of integrative frameworks. Therefore, our research fills that gap by proposing a multi-model structure for automated risk classification, trigger identification, and impact analysis of project textual data.

1.6. Critical Synthesis

According to the literature, AI technologies hold a great deal of promise for improving project management through automation, predictive modeling, and proactive risk detection. Solutions based on NLP are currently demonstrating success in the analysis of contracts and text-based risk detection but have problems with standardization and cross-industry validation. In the meantime, the management and ethical codes of AI are under development but not sufficiently operational, and the questions of transparency, accountability, and trust remain unaddressed, as Table 1 demonstrates. To encourage the responsible and efficient use of AI in project risk management, these gaps highlight the necessity of cross-sectoral research, standardized practices, and scalable governance structures.

Table 1.

Thematic contributions and gaps in AI project risk management.

According to the literature, the notion of applying AI and NLP to enhance project risk management is growing, especially in relation to predictive analytics and risk classification, which happens automatically. Nevertheless, there is little indication of widespread adoption, and the existing applications are typically limited to specific industries and lack consolidation. By developing a comprehensive AI-based framework for the proactive management of quality hazards in a project, incorporating sophisticated Natural Language Processing tools, explainable machine learning (e.g., SHAP values), and comparing feature extraction algorithms (TF-IDF vs. embeddings), this study will contribute to closing these gaps. The approach is assisting in the development of a decision-support system that is both scalable and operationally feasible, which may serve as the foundation for the subsequent application of AI-driven project risk governance.

1.6.1. Research Questions

Based on the gaps and issues detected in the literature on AI-driven risk management in terms of project settings, the present research will seek to answer the following critical questions:

- ➢

- Do artificial intelligence algorithms have reliable ways of classifying and predicting project risks, their triggers, and possible effects just by examining unstructured textual descriptions of project documents?

- ➢

- What machine learning algorithms and associated feature extraction (e.g., TF-IDF, Word Embeddings) approaches are more effective in organizing, processing, and extracting actionable information about various unstructured risk data?

- ➢

- How far can model interpretability tools enhance the reliability, transparency, and practicality of AI-based risk prediction systems for major project stakeholders and managers, thereby bridging the gap between advanced analytics and managerial decision-making?

1.6.2. Research Objectives

To address the research questions and based on the available knowledge base, the major objectives of this study are the following:

- ➢

- Design and test an artificial intelligence-based system that will predict types of project risks, their stimuli, and their possible outcomes based on an edited collection of project risk records.

- ➢

- Perform comparative study on two popular feature extraction methods—TF-IDF and Word Embeddings—together with a set of machine learning models such as Logistic Regression, Support Vector Machines, Random Forest, XGBoost, and Naive Bayes to determine the relative performance of each pair under different risk classification problems.

- ➢

- Determine and explain the issues and opportunities that arise from implementing AI into real-world project risk management conditions. Specifically, aspects of the concept include the interpretability of models, scalability, and the ability to integrate smoothly with existing project management processes.

- ➢

- Suggest a commonplace structure of a unitary choice support system. It is hoped that this system can be used not only to support proactive risk mitigation but also to enhance quality assurance throughout the project lifecycle, thereby creating a new synergy between the latest AI research and the practical applicability of project management.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

In responding to the research question, this paper adopts a quantitative and experimental approach to assessing the ability of artificial intelligence (AI) and Natural Language Processing (NLP) to enhance project management by facilitating the early detection of project risks. The aim is to create classification models that can predict three key risk parameters: Risk Category, Trigger, and Impact, which are predicted using textual descriptions of risk. Although these outputs are conceptually interdependent, they are modeled as discrete classification problems in this research to provide analytical clarity and interpretability, and to allow for a clear assessment of model performance on various dimensions of risk. The experimental setup is also simplified, as one thoroughly understands the behavior of each model under different conditions, which is facilitated by this structure. Future research will consider multi-output or sequence-based architectures to address the potential correlations between these dimensions. An original dataset was created, purged, and formatted for supervised learning. Several machine learning models were developed and tested with two different feature extraction techniques: Term Frequency–Inverse Document Frequency (TF-IDF) and Word Embeddings (GloVe). To further enhance predictive robustness, the study employed a design science research methodology, in which AI model artifacts and their evaluation metrics are created, evaluated, and refined through iterative cycles. Therefore, this ensures a gradual improvement in model accuracy and generalization through feedback and validation of model performance. Following established standards in AI and NLP research, the methodology describes the structured process used to build, evaluate, and justify the selected models and analytical choices. Therefore, this ensures a gradual improvement in model accuracy and generalization through feedback and validation of model performance.

2.2. Dataset Construction

The dataset was produced as part of the quality-oriented initiative’s AI-driven risk management project. To cover every risk factor, risk scenarios were compiled from data, domain literature, project management case studies, and simulated entries. An Excel file with the following columns (Table 2) lists the 2000 instances in the resultant database:

Table 2.

Project risk management dataset schema.

This methodical approach, according to the PMI, allows sufficient diversity for multi-class classification and ensures that it aligns with actual project risk documentation practices [].

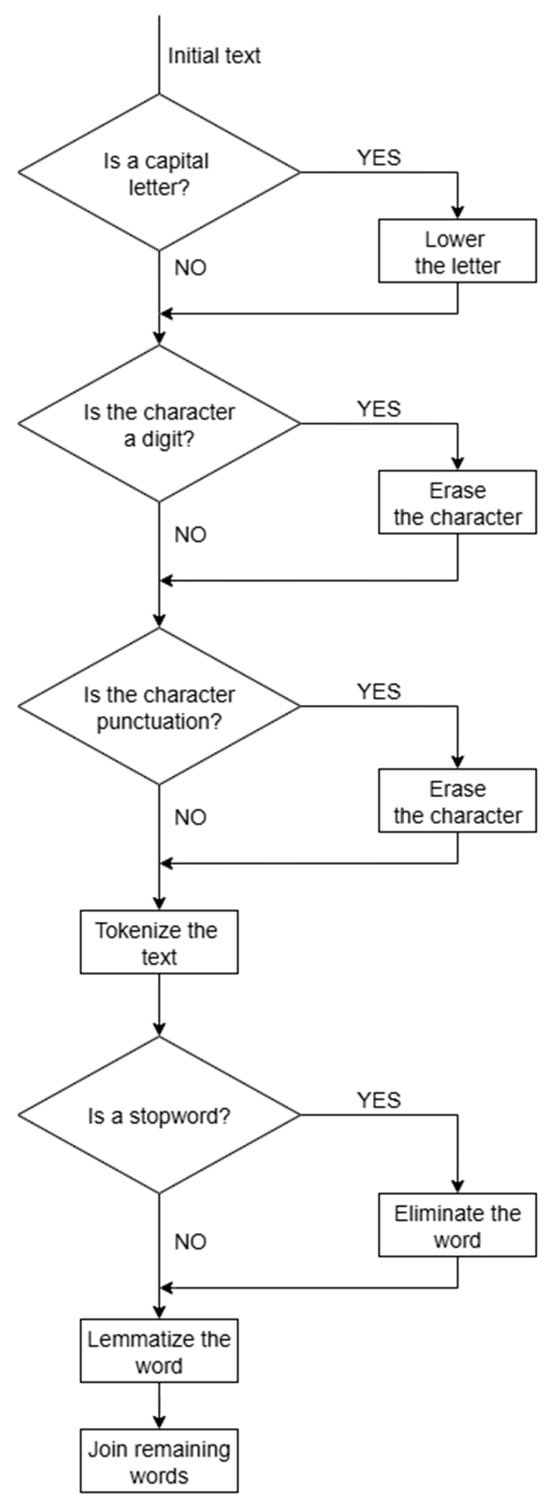

2.3. Data Preprocessing

The well-known NLP standards [] were followed for preprocessing the Risk Description into text for feature extraction:

- Text Normalization: All the text was turned to lowercase; the use of punctuation, numbers, and special characters were removed with the re module in Python. Tokenization: Whitespace-based splitting of sentences into tokens.

- Remove stopwords: A frequent list of stopwords (e.g., the, and, in, etc.) was eliminated by nltk stopword lists. Lemmatization: Words are shortened to their root form with the WordNetLemmatizer (e.g., delays–delay).

- Concatenation: Clean tokens were concatenated to create processed descriptions. The process reduces noise in text-based data and increases the discriminative ability of features [].

2.4. Feature Extraction

There were two complementary methods to extract features that were implemented.

2.4.1. TF-IDF

TF-IDF (Term Frequency–Inverse Document Frequency) is an effective technique for extracting textual features due to its simplicity and interpretability. It can be used well to point out key words in individual documents in comparison to the frequency in the corpus. Nevertheless, the literature notes the following limitations: Context Ignorance: TF-IDF fails to identify associations among words or semantic context, which can frequently lead to loss of meaning of polysemous words or context-dependent words. This has been studied in recent comparative studies [,].

Comparing the bag-of-words of the TF-IDF approach with more recent embedding techniques, it is found to be deficient in terms of capturing nuance and word order. Performance in Modern NLP Tasks: TF-IDF may be effective for document classification and information retrieval, but studies [,,,] suggest that its usefulness is less pronounced in tasks with richer contexts, such as sentiment analysis or semantic similarity.

2.4.2. Word Embeddings

Word Embeddings, which include those generated by the GloVe model, have changed the meaning of feature representation by embedding semantic meaning in dense continuous vectors. In particular, the GloVe model uses data of global co-occurrence to generate embeddings that are informative of both syntactic and semantic characteristics []. The main critical arguments in the literature are as follows: Semantic Richness: Word Embeddings utilize vectors to measure similarity between words, which contrasts with TF-IDF, and can significantly enhance downstream NLP tasks []. Dimensionality and Interpretability: The rich dimensionality of embeddings (e.g., 100 dimensions in GloVe-Wiki-Gigaword-100) is useful at the expense of interpretability, which is inferior to sparse ones such as TF-IDF. Sentence Embedding Approach: Sentence-level representation based on averaging word vectors is common, but the literature [] has noted that this can be counterproductive to compositional structure and that alternative approaches of BERT or sentence-transformers can preserve sentence context.

2.5. Experimental Setup

2.5.1. Train–Test Split

Stratified sampling was used to divide the dataset into 80% training (1600 instances) and 20% testing (400 instances) sets, ensuring that there is no disruption in the class distributions in terms of the Risk Category, Trigger, and Impact columns.

2.5.2. Classification Models

Five supervised machine learning algorithms are implemented in Table 3:

Table 3.

Overview of machine learning algorithms and their justifications.

2.6. Evaluation Metrics

The model performance was estimated using macro-averaged metrics, which were calculated with an equal weight to each of the classes without considering the frequency:

- Precision: Fraction of correct optimistic prediction (per class).

- Recall: The possibility of recognizing all true positives of classes.

- F1-Score: The harmonic means of false positives and false negatives based on precision and recall.

- Confusion Matrices: Visualization of performance per-class with heatmaps in seaborn module version 0.13.2.

Since the dataset is multi-class (e.g., the 28 Trigger classes), the macro-averaging method was preferred over the micro-averaging method, as it avoids bias in the most dominant classes [].

Besides the standard models used in our research, we also acknowledge the existence of more modern and task-oriented models, which are typically employed in short-text and multi-label classification, including convolutional neural networks (CNNs), hierarchical classifiers, transformer-based encoders, and AutoML models. Although these models were not part of the experimental pipeline, which allowed for a focus on strong and interpretable baselines, they are mentioned here in the context of contextual benchmarking. Recent comparative studies indicate that transformer-based models may be more accurate in specific areas, but they may require significantly more data and computation. In comparison, the current research lays a clear groundwork for future studies to build upon by incorporating hierarchical or sequence-aware models and testing them on various datasets. Therefore, this provides a distinct basis for cumulative improvement and methodological comparability among studies.

The entire experiment was written in Python 3.9.12 in a Jupyter Notebook version 7.4.7 environment, and the libraries used are demonstrated in Table 4 below:

Table 4.

Experimental environment and key python libraries.

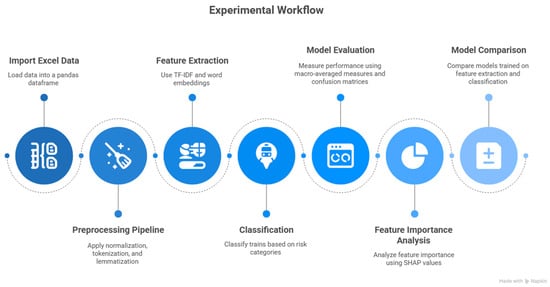

The flow of the experimental work is presented in the following way:

- Import Excel data to a pandas dataframe.

- Use preprocessing pipeline (normalization, tokenization, lemmatization).

- TF-IDF and Word Embeddings based on parallel branches. Classify the Trains based on Risk Category, Trigger, and Impact.

- Measure models on macro-averaged measures and confusion matrices.

- Use SHAP values to analyze importance of features.

- Compare the performance of models that are trained on feature extraction and classification.

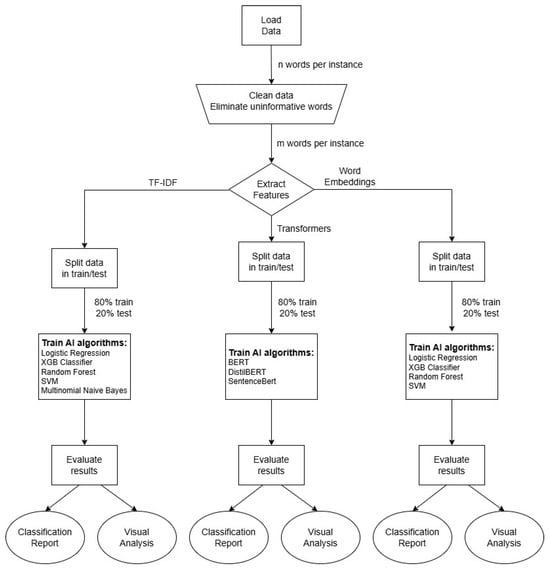

The visual representation of this methodology is made by the figures that summarize the pipeline (workflow diagram) and preprocessing pipeline (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Experimental workflow diagram (source: authors).

3. Results

3.1. Overview of Experimental Findings

The database from the project is organized using an Excel file with four columns: Risk Description, Risk Category, Trigger, and Impact. In the study, we considered only the first column, “Risk Description”, as an input for the AI algorithms, and the other three columns—"Risk Category”, “Trigger”, and “Impact”—as outputs for each model. A specific model was trained to map the input to each of the other columns. Therefore, for a final decision, the input must pass through at least three models.

For a comprehensive analysis in the study, we used 2000 instances from the database. Each column contains a different number of classes, with each class having a varying number of instances (represented by lines in the associated Excel file).

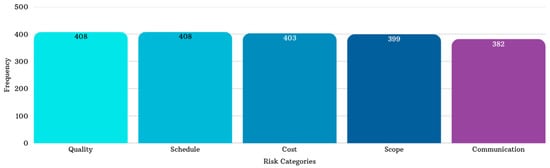

3.2. Data Characteristics

Risk Category has five classes: Communication, Cost, Quality, Schedule, Scope. A histogram with the number of instances for each class is presented in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2.

Distribution of risk categories (source: authors).

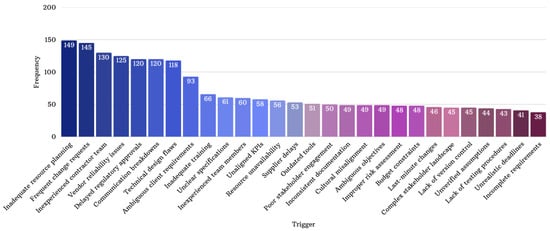

Trigger has 28 classes: Ambiguous client, Ambiguous objectives, Budget constraints, Communication breakdowns, Complex stakeholder landscape, Cultural misalignment, Delayed regulatory approvals, Frequent change requests, Improper risk assessment, Inadequate resource planning, Inadequate training, Incomplete requirements, Inconsistent documentation, Inexperienced contractor team, Inexperienced team members, Lack of testing procedures, Lack of version control, Last-minute changes, Outdated tools, Poor stakeholder engagement, Resource unavailability, Supplier delay, Technical design flaws, Unaligned KPIs, Unclear specifications, Unrealistic deadlines, Unverified assumptions, Vendor reliability issues. A histogram with the instance frequency for each class is illustrated in Figure 3 below.

Figure 3.

Count of trigger instances per risk category (source: authors).

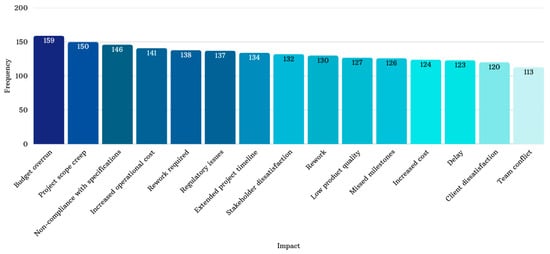

Impact has 15 classes: Extended project timeline, Stakeholder dissatisfaction, Project scope creep, Rework required, Budget overrun, Non-compliance with specifications, Increased operational cost, Rework, Delay, Regulatory issues, Missed milestones, Low product quality, Client dissatisfaction, Increased cost, Team conflict. A histogram with the number of instances for each class is presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Number of instances for each class (source: authors).

3.3. Tools and Environment

Python programming language scripts were used to design all AI algorithms, data handling, and data visualization. We used Python version 3.9.12 under the Anaconda Distribution package managing system and, as an Integrated Development Environment, we used Jupyter Notebook. The main modules/libraries employed in the scripts were pandas, sklearn, matplotlib, re, seaborn, XGBoost, SHAP, numpy and Gensim. For each library, the purpose within the larger context of the study is explained below:

- Pandas was used to load the data from an Excel file and pack it into a dataframe.

- Sklearn has multiple uses. At the beginning of the program, it was used for splitting the data into train and test, with a ratio of 80% for training the models and 20% for testing the ability to generalize. To extract features and form the text, a method called TfidfVectorize was utilized from the feature_extraction submodule of sklearn. After that, certain AI models were deployed using this library—models like the following: Logistic Regression, Random Forest classifier, Multinomial Naive Bayes and Support Vector Machine. Finally, for a comprehensive evaluation of the trained models, submodule metrics were employed with the main methods being classification_report, confusion_matrix, and ConfusionMatrixDisplay.

- Matplotlib was utilized to display and save graphics and images.

- Re was employed in the data cleaning process to lower all the letters, to eliminate punctuation, numbers and special characters, and to remove extra spaces.

- Seaborn was used to make a heatmap for the misclassification matrix.

- XGBoost was employed to deploy and train an Extreme Gradient Boosting AI model.

- SHAP was used to evaluate the importance of each word in a visual manner.

- Numpy used for small functions like sorting the results in ascending/descending order based on an importance coefficient.

- Gensim was used to download and load the GloVe-wiki-gigaword-100 model.

3.4. Experimental Workflow

The workflow of the algorithm is presented in Figure 5 and Figure 6. Initially, after loading the data in a dataframe format, a cleaning procedure was run on the text information from the Risk Description column (this procedure is thoroughly described in Figure 7) to remove information that is not relevant for the AI algorithm’s classification process. The cleaning process entails a number of minor actions, including straightforward ones like changing all letters to lowercase, eliminating all numerals from the text, and deleting all punctuation characters. Furthermore, after this set of operations, a tokenization process that splits the text into tokens/words after the space character was performed. The stopwords (examples: the, in, on, to, of, that, etc.) in English were eliminated and each word was reduced to its base form in the lemmatize process (examples: running become run, dogs become dog). The resulting words were then concatenated/united, thus resulting in the cleaned form of the initial text.

Figure 5.

The workflow of the algorithm (source: authors).

Figure 6.

Data preprocessing pipeline (source: authors).

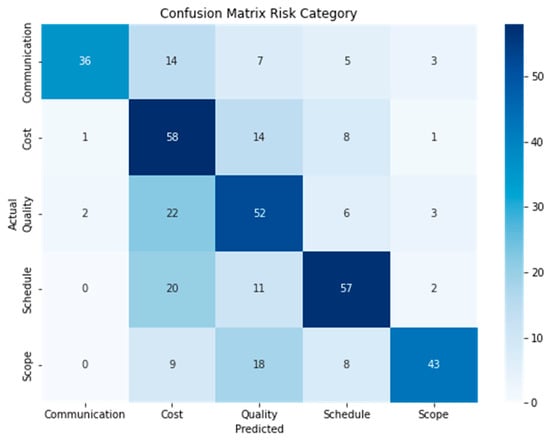

Figure 7.

Confusion matrix for the best model (source: authors).

For feature extraction, two methods were used, thus resulting in a split into two branches for the workflow: Term Frequency–Inverse Document Frequency (TF-IDF) and Word Embeddings with GloVe-wiki-gigaword-100 model. In each branch, a split dataset of 80% for training (1600 instances) and 20% for testing (400 instances) was performed. For the TF-IDF feature extraction branch, five AI algorithms were tested, namely Logistic Regression, XGB Classifier, Random Forest, SVM, and Multinomial Naive Bayes. For the second branch, the Multinomial Naive Bayes was omitted, since it is mostly employed for classifying for TF-IDF features, not for other methods of feature extraction. The evaluation of the performance of each model was evaluated both as a numerical value, through metrics such as macro-average values for precision, recall, and F1-score, and in a visual manner, using a misclassification matrix (Figure 5 and Figure 6).

Despite the promising results, several limitations exist. First, our model has been tested on a domain-specific dataset, which may limit its scalability or generalization to other industries such as IT, healthcare, or infrastructure. Second, we employed classical machine learning models that restrict the ability to capture deeper semantic structures in complex risk descriptions. Future work will include cross-domain evaluation, data expansion, and the incorporation of deep-learning architectures and multi-output or sequence-based models. These enhancements will improve flexibility, situational awareness, and the robustness of automated risk analysis.

3.5. Model Evaluation

The models’ performances were evaluated using macro-averaged metrics (precision, recall, and F1-score) and confusion matrices.

3.5.1. Risk Category Classification

The evaluation of the results for all the AI algorithms for both TF-IDF and Word Embeddings for the “Risk Category” is presented in Table 5 and Table 6 below.

Table 5.

Comparative results of TF-IDF and Word Embeddings for Risk Category classification.

Table 6.

Performance analysis of transformer models for Risk Category using three metrics.

Considering the number of classes for this column, namely five, a random guess by the model would determine a macro-average precision of 0.2. For this first model, the best results are obtained by the XGB Classifier using TF-IDF features, with a macro-average precision of 0.68, a macro-average recall of 0.61, and a macro-average F1-score of 0.63. The confusion matrix for the best model is presented below (Figure 7), from which it can be observed that the model has the most visible problems with the Cost and Quality classes. There are many other instances from the different classes that are classified into these two. There are 115 misclassified items for this issue.

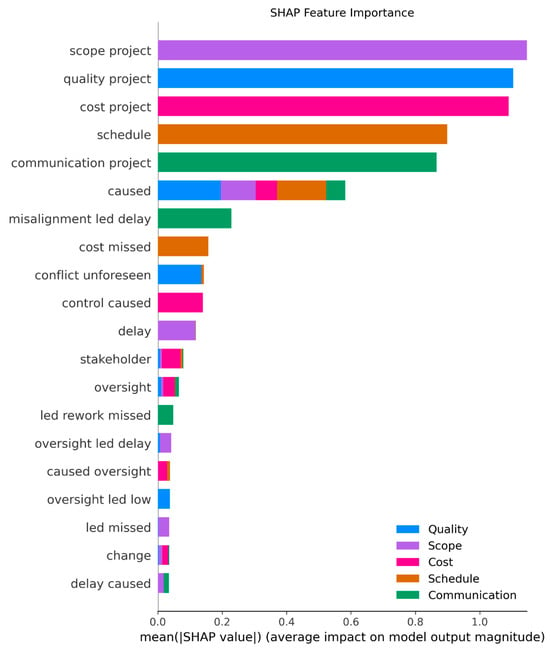

The SHAP plot analysis for the Risk Category column shows that the model clearly makes certain strong key linguistic associations with specific Risk Categories as follows:

- For the Quality class, the n-grams with the most impact on the decision-making process are “quality project”, with a magnitude above 1, followed by “conflict unforeseen” and “oversight led low”, with lower magnitudes, just under 0.2.

- For Scope, the main n-grams used by the model to make a decision are “scope project”, with a magnitude greater than 1, followed by “delay”, “oversight led delay”, and “led missed”, with magnitudes lower than 0.2.

- For the Cost category, the specific n-grams are “cost project”, with the highest magnitude above 1, followed by “control caused”, “stakeholder”, “oversight”, and “caused oversight”, with significantly lower values for the magnitude.

- For the Schedule category, the most important n-grams are “schedule”, with a magnitude close to 1, and “cost missed”, with a magnitude value of approximately 0.2.

- For the Communication class, the n-grams that have the most importance are “communication project”, with the most significant magnitude, just under 1, followed by “misaligned led delay” and “led rework missed”.

As can be seen from the figure, some features overlap across different categories. The most relevant examples are words like “caused”, which has a significant magnitude on all five categories, “oversight”, that has a predominant impact for the Cost class but also a degree of importance for the Quality and Communication classes, and “delay caused”, that has an almost equal importance for both Scope and Communication. This behavior creates a semantic ambiguity that leads to some extent of overlap between different categories of risk (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

The most important 20 n-grams in a SHAP analysis for Risk Category using TF-IDF feature extraction and XGB Classifier for five different classes (source: Authors).

The evaluation of the results for all the AI algorithms for both TF-IDF and Word Embeddings for “Trigger” is presented in Table 7 and Table 8 below.

Table 7.

Comparative results of TF-IDF and Word Embeddings for Trigger prediction.

Table 8.

Performance analysis of transformer models for Trigger using three metrics.

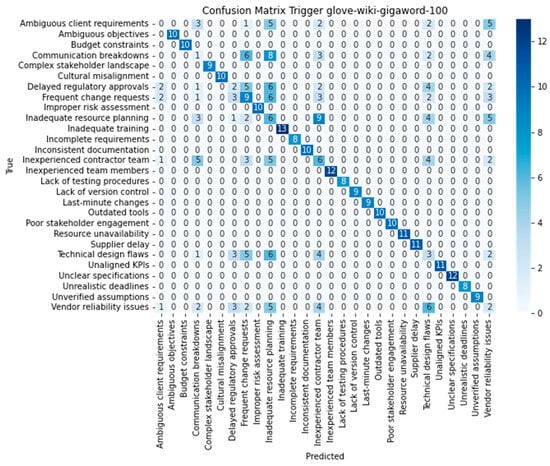

Considering the number of classes for the Trigger factor, namely 28, a random guess on a large sample size would yield a macro-average precision of around 0.04. In this case, the results were nearly similar for most of the models, with the highest values for all three metrics obtained by Logistic Regression, SVM with both TF-IDF features and Word Embeddings with GloVe100, and Random Forest with GloVe100 features. The highest values were 0.75 for macro-average precision, 0.75 for macro-average recall, and 0.75 for macro-average F1-score. The confusion matrix (Figure 9) for Logistic Regression with GloVe100 feature extractor is presented below. Most classes achieve a very good result, as is seen with the concentration of the values on the principal diagonal of the matrix, but improvements must be made for certain classes such as the following: “Ambiguous client requests”, with the worst results obtained for any class, “Communication breakdowns”, “Delayed regulatory approvals”, “Frequent change requests”, “Inadequate resource planning”, “Inexperienced contractor team”, “Technical design flaws”, and “Vendor reliability issues”.

Figure 9.

The confusion matrix for Logistic Regression with GloVe100 feature extractor (source: authors).

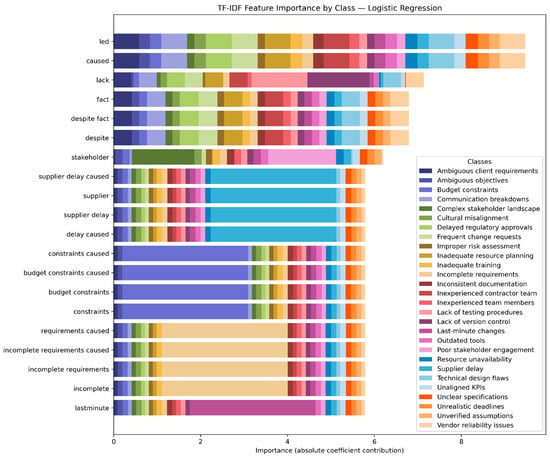

3.5.2. Trigger Classification

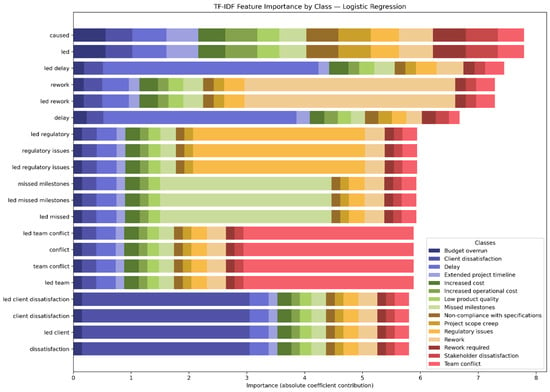

We used Logistic Regression with the TD-IDF feature extraction method to provide a visual word-level interpretation using a SHAP plot, because it maintains a one-to-one relationship between the model’s input dimension and n-grams.

A Word Embedding method, such as GloVe, is not an ideal option for the SHAP plot, because the features are represented by dense embedding dimensions, not plain words like those in TF-IDF. In this Figure, the 20 most important n-grams are presented, with how they contribute to the model decision for classifying into one of the 28 categories (each with a different color). There are a few n-grams that are predominant for a single class. Examples include “supplier delay caused”, “supplier”, and “delay caused”, which make a significant contribution to the model for the class “supplier delay”. Other n-grams that exhibit mostly single class contributions are “constraints caused”, “budget constraints caused”, “budget constraints”, and “constraints” for the “Budget constraints” class. Another set of n-grams that display the same behavior is “requirements caused”, “incomplete requirements caused”, “incomplete requirements”, and “incomplete” for the “Incomplete requirements” class. There are also examples of cross-class, non-specific n-grams, such as “led”, “caused”, “fact”, “despite fact”, and “despite”, which appear in all 28 classes with mostly similar coefficients. This behavior suggests that this set of n-grams is generic and not discriminative enough to establish a direction for one class (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Most important 20 n-grams in a SHAP plot for Trigger category using TF-IDF for feature extraction and Logistic Regression for 28 classes (source: authors).

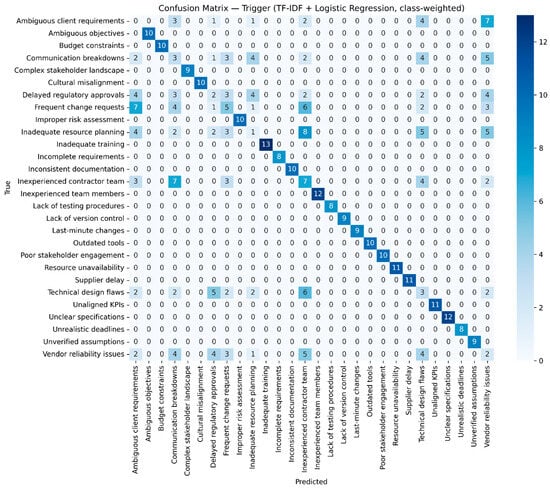

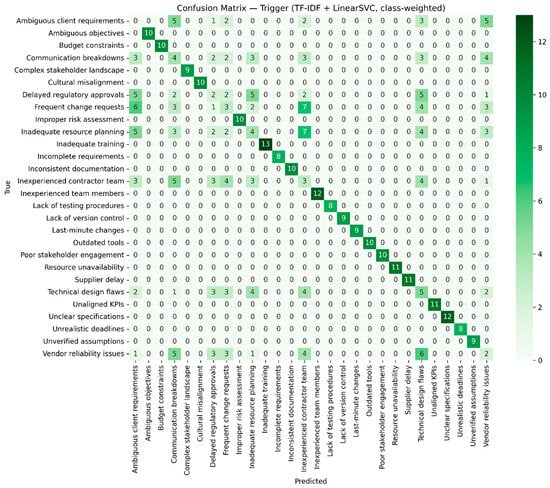

One of the main issues in the Trigger category is class imbalance, with classes such as “Inadequate resource planning”, “Frequent change requests”, and “Inexperienced contractor team” having roughly three times more instances than classes like “Incomplete requirements”, “Unrealistic deadlines”, or “Lack of testing procedures”. As a potential solution, a weighting technique was employed during training for both Logistic Regression with TF-IDF and SVM with TF-IDF, achieving the highest scores across all three performance metrics. The weights were calculated using the compute_class_weight method from the Scikit-learn module. This strategy involves assigning smaller classes larger weights and larger classes smaller weights to reduce potential bias in the classifier towards classes with a large number of examples. The computed values for the 28 classes are shown in the table below.

As shown in Table 9, classes with fewer instances, marked in blue, have higher weights, while classes with more examples, marked in red, have lower weight values. Table 10 presents the primary performance metrics for the two models analyzed, to which class weighting techniques have been applied.

Table 9.

Weights used to mitigate the imbalance present in the Trigger category.

Table 10.

Performance metrics results after applying weighting techniques for Logistic Regression and SVM.

The results from the classification report, from which the three performance metrics were extracted, do not indicate a significant improvement from using the weighting technique; the values for macro-average precision, macro-average recall, and macro-average F1-score remain unchanged. This conclusion can also be strengthened through a visual analysis of the two confusion matrices presented in Figure 11 and Figure 12.

Figure 11.

Confusion matrix for Logistic Regression after applying the weighting technique to mitigate the imbalanced distribution of classes.

Figure 12.

Confusion matrix for SVM after applying the weighting technique to mitigate the imbalanced distribution of classes.

3.5.3. Impact Classification

The evaluation of the results for all the AI algorithms for both TF-IDF and Word Embeddings for “Impact” are presented in Table 11.

Table 11.

Performance Evaluation of AI Algorithms for “Impact” Classification.

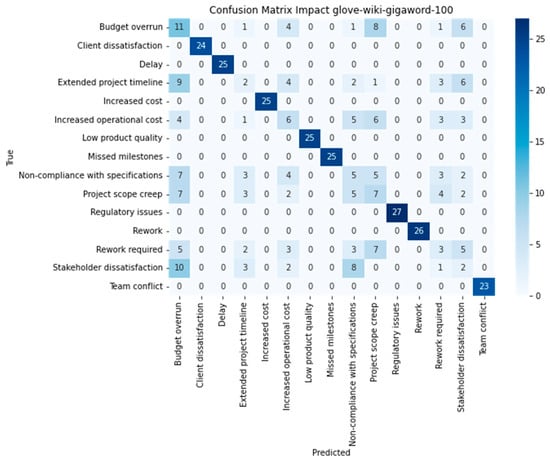

For the number of classes in the “Impact” column, namely 15, a random guess would result in a macro-average precision of 0.07. Analyzing the three metrics, the best result using macro-average precision is obtained by SVM with Word Embeddings GloVe100 as a feature extractor. The best result using macro-average recall and macro-average F1-score are obtained by Logistic Regression with Word Embeddings GloVe feature extractor. The confusion matrix (Figure 13) for Logistic Regression with GloVe100 is presented below. There are six classes of poor results: “Extended project timeline”, “Increased operational cost”, “Project scope creep”, “Non-compliance with specifications”, “Rework required”, and “Stakeholder dissatisfaction”. An apparent confusion in the model, as evident in the matrix, exists between “Project scope creep” and “Non-compliance with specifications” (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

The confusion matrix for Logistic Regression with GloVe100 (source: authors).

A detailed interpretability analysis is provided in the figure above, using a multiclass SHAP-style plot, where TF-IDF with Logistic Regression is used to classify the Impact categories. There are a few sets of n-grams that make a dominant contribution for one class; these are known as strong discriminative n-grams. The first set of strong discriminative n-grams is given by “led delay” and “delay,” which provide a significant contribution to the decision-making process for the “Delay” class. A second set of n-grams, including “led issues”, “regulatory issues”, and “led regulatory issues”, leads the model for the “Regulatory issues” class. For the “Team conflict” class, the set of n-grams that are highly correlated with this outcome are “led team conflict”, “conflict”, “team conflict”, and “led team”. Another example is the set of n-grams “led client dissatisfaction”, “client dissatisfaction”, “led client”, and “dissatisfaction”, which indicate the “Client dissatisfaction” class. Two generic n-grams, such as “caused” and “led”, have mixed contributions towards all classes (Figure 12).

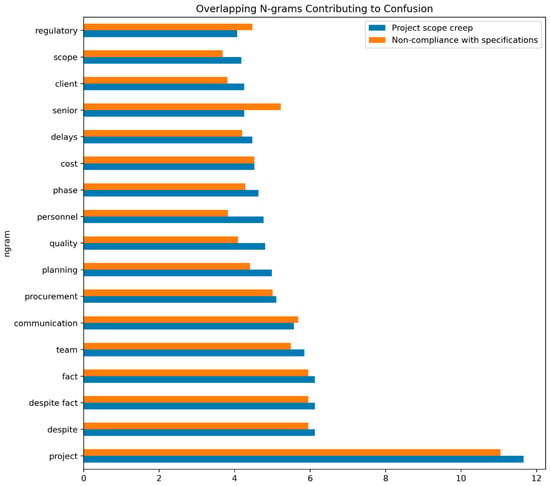

A misclassification between two classes, “Project scope creep” and “Non-compliance with specifications”, is highlighted by the confusion matrix for the Impact category. We performed a linguistic analysis on the overlapping n-grams of the two classes (see Figure 14) because they are the most frequent and informative shared information.

Figure 14.

Most significant 20 n-grams in a SHAP plot for Impact category using TF-IDF for feature extraction and Logistic Regression for 15 classes (source: authors).

The image highlights a consistent overlap with terms such as “project”, “despite”, “despite fact”, “fact”, “team”, “communication”, “procurement”, “planning”, “quality”, and “personnel”, that appear with similar weights in both classes. This suggests that the terminology and textual descriptions of the two classes are highly similar, indicating that the model has limited distinctive information to separate the two cases.

We calculated cosine similarity between the two centroid vectors for each class (“Project scope creep” and “Non-compliance with specifications”) in the TF-IDF feature space to enhance visual analysis (Figure 15). Therefore, the two classes exhibit a high degree of similarity related to n-grams, which is proved by the value (e.g., 0.9543192005838137).

Figure 15.

Most frequent and informative overlapping n-grams for “Project scope creep” and “Non-compliance with specifications” (source: authors).

The cosine similarity ranges from 1 to 0, with values close to 1 indicating that the two texts are almost identical in vocabulary or semantics (they share many important terms), and values close to 0 indicating a lack of similarity or unrelated textual information. This metric confirms that the model struggles to distinguish between the two classes because there is insufficient distinctive information for each class.

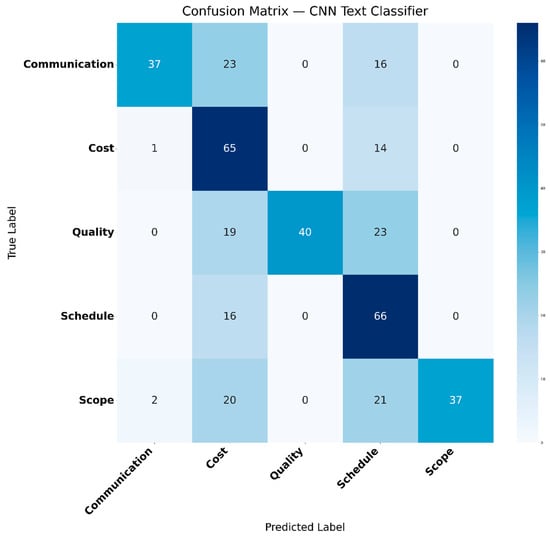

3.6. Task-Specific Models

Initially, CNNs were developed for image analysis and interpretation; nowadays, they have been applied in many areas, including text classification. To extend the initial scope of the model comparison, a modern deep learning architecture was tested on the dataset. This extension of the starting framework allows us to evaluate whether or not a CNN can discover/learn different patterns that classical machine learning models like Logistic Regression, SVM, XGBoost, Random Forest, or Naive Bayes cannot.

We tested a CNN text classification architecture that has the text embeddings as an input, followed by a convolutional 1D layer, a GlobalMaxPooling1D layer, a Dense layer with 128 neurons with a Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) activation function, a Dropout layer to avoid overfitting, and, finally, the last layer is a Dense layer with one neuron for each class. The model was compiled using sparse categorical cross-entropy. The resulting model utilizes 2,055,685 trainable parameters. The results for all three categories (“Risk Category”, “Trigger”, and “Impact”) are analyzed by the main performance metrics utilized in the paper in Table 12 and Table 13 below:

Table 12.

Performance analysis of Transformer models for Impact using three metrics.

Table 13.

CNN model for classifying Risk Category, Trigger, and Impact.

For the Trigger and Impact categories, the results align with those of all the other models. A notable difference appears in the Risk Category, where the macro-average precision is significantly higher than that of all the different models. However, the other two metrics remain the same. This behavior can also be seen in Figure 16.

Figure 16.

Misclassification matrix for CNN Risk Category classification.

4. Discussion

4.1. Dataset Insights and Organization

The data was grouped into four columns, namely, Risk Description, Risk Category, Trigger, and Impact. The Risk Description was the only input in this analysis, and the other three columns were the outputs in this prediction. Individual models were trained individually on each output; this implies that the system had to run at least three AI models on a single input description to provide a complete classification.

The dataset includes three main independent categories: “Risk Category”, “Trigger”, and “Impact”. Each category corresponds to different taxonomies and semantics. Each category has a high degree of independence; there are different numbers of classes (5, 28, and 15, respectively); each class has distinct decision n-grams in the SHAP plots; and the data distributions differ across classes. One of the main purposes of the article was to develop a modular approach to selecting the best model for each category and to analyze the classification performance across a wide range of AI models. The outputs are annotated independently and do not share a common label structure, so trying a multi-output model would force the architecture to share features for tasks that are not closely related. Sequence-aware models were also not included in the study, because the problem was formulated from the beginning as predicting three different classes, not generating a sequence as an output.

The data was 2000 cases of different real-life project risk scenarios across various output categories. One can refer to the Risk Category, which includes five distinct classes (Communication, Cost, Quality, Schedule, Scope). Comparatively, there were 28 and 15 classes in the Trigger and Impact columns, respectively. This is a critical imbalance in the classes: whereas Risk Category models could sensibly divide five classes, Trigger and Impact classification created a more challenging learning context, exposing the model to the risk of false classification.

Across all three categories (“Risk Category”, “Trigger”, “Impact”), the tested machine learning models display similar performance, as demonstrated by the three metrics analyzed (“macro-average precision”, “macro-average recall”, “macro-average F1-score”). The nature of the dataset can provide some explanations for this similarity. For the “Risk Category”, all classes achieve good results by identifying a set of n-grams that characterize each class. The clearest confusion is between Cost and Quality, as quality is generally closely linked to cost. For the Trigger category, certain classes show nearly perfect prediction precision, such as the following: “Ambiguous objectives”, “Budget constraints”, “Inadequate training”, “Incomplete requirements”, etc., but some categories exhibit cross-class confusion due to similar or closely related feature spaces, like (“Technical design flaws”, “Inexperienced contractor team”) and (“Technical design flaws”, “Communication breakdowns”). Another issue is classes that lack sufficiently distinct key n-grams to clearly differentiate them, including “Delayed regulatory approvals”, “Frequent change requests”, “Technical design flaws”, and “Vendor reliability issues”. Therefore, we believe that future work should involve reorganizing the dataset multiple times and testing the same best algorithm to find the optimal number of classes. Moreover, for the Impact category, one significant issue was confusion between two classes (“Non-compliance with specification” and “Project scope creep”), which was thoroughly analyzed and found to be due to the high similarity of their feature/n-gram spaces. A similar problem was identified between “Rework required” and “Stakeholder dissatisfaction”.

4.2. Architecture and Feature Extraction Options Modeled

There were two strategies of feature extraction:

- TF-IDF (Term Frequency–Inverse Document Frequency): This is a standard technique that does well in sparse data representation.

- Word Embeddings (GloVe100): A semantic method of obtaining contextual meaning of a pre-trained embedding model.

This approach enabled us to compare the performance trade-offs of more interpretable, lightweight features (TF-IDF) and more semantically rich embeddings (GloVe). The models used for testing are Logistic Regression, SVM, Random Forest, XGBoost, and Multinomial Naive Bayes (using only TF-IDF), selected for their complementary nature. The ease of interpretation and stability of simpler algorithms, such as Logistic Regression, were offset by their greater predictive ability on complex classifications, as demonstrated by ensemble algorithms like XGBoost.

4.3. Target Variable Analysis of Performance

4.3.1. Risk Category

In this task, the highest-performing model was XGBoost with TF-IDF, with a macro-average precision of 0.68 and a macro-average F1-score of 0.63.

The results demonstrate a significant improvement over random guessing (baseline precision of 0.20 across five classes), indicating that even brief textual representations of risks contain sufficient information to be useful in categorization. Nonetheless, the confusion matrix revealed that some misclassifications still occurred between Cost and Quality, indicating a semantic overlap between the two categories. Indicatively, risks conceptualized based on defective supplier deliverables may have a high probability of influencing both quality performance and cost increases. This vagueness highlights the need for more discriminating labeling and perhaps multi-labeling in subsequent versions.

4.3.2. Trigger

Trigger prediction was the most difficult with 28 classes, but it also gave surprisingly good results. Several models, such as Logistic Regression, SVM, and Random Forest with both TF-IDF and GloVE embeddings, attained macro-average precision, recall, and F1-scores of 0.75. These high scores suggest that risk descriptions often include explicit hints about root causes (e.g., “slow regulatory approvals” or “poor resource planning”); therefore, predicting the triggers is more reliable. The confusion matrix, on the other hand, revealed problematic classifications, including but not limited to ambiguous client requests, communication breakdowns, and vendor reliability issues, where overlapping language may have contributed to reduced accuracy. This observation advises to reduce semantic ambiguity.

4.3.3. Impact

The prediction of Impact was also more challenging, with a macro-average accuracy of 0.63. The highest accuracy, a macro-average of 0.63, was achieved with SVM using GloVe embeddings (refer to Table 13). The mix of classes, such as Project Scope Creep and Non-Compliance with Specifications, was especially severe. This is also characteristic of the problems in assessing the outcomes of projects: effects are usually interlinked and situational, and one risk may lead to impact across multiple dimensions (time, cost, quality).

These results highlight the importance of integrating AI with interpretability and domain expertise to validate predictions in the context of a real-world project.

4.4. Lessons Learned and Implications

Accordingly, with Kineber et al.’s [] results, our findings contribute to the academic literature because we demonstrated the ability of NLP methods to extract meaningful patterns from unstructured construction project text.

Therefore, our approach is different from Kineber et al.’s [], because their research was oriented to automated extraction using general-purpose language models; our methodology was based first on a domain-specific preprocessing strategy; second, our tailored classification categories aligned with project management risk frameworks; and, finally, we employed an interpretability layer designed to support decision-making by project stakeholders.

This combination allows not only the accurate classification of textual risks but also actionable, transparent outputs that can be directly leveraged in project governance, addressing a usability and explainability gap in prior work.

The following are some of the issues that we point out and critically interact with in previous work: Class imbalance and Data Quality: In line with issues related to class imbalance in datasets, which Yazdi et al. [] identify as one of the challenges in their comparative analysis of AI + risk management, class imbalance in a dataset may bias model learning to those classes with higher percentages, as well as undermine performance in those with lower percentages []. Such an imbalance may be addressed through methods such as synthetic oversampling (SMOTE), data augmentation, or more targeted data collection, ensuring that higher-risk types (though rare) are represented.

Model Selection and Parsimony: The good results of simpler models (Logistic Regression, SVM) in our experiments are consistent with the literature on explainability: frequently, simpler, more transparent models can compete with complex models in the real world, particularly where trust and interpretability are important. According to Hassija et al. [], black-box models are difficult to implement unless they are explained in a simple way. This supports the notion that, in risk-sensitive areas, model simplicity, as well as interpretability, might be a more palatable option for stakeholders than marginal gains from highly complex models.

Interpretability and Trust of Stakeholders: The general direction of explainable AI (XAI) aligns with our explanations of the model using SHAP. Rane et al. highlight that these explanations contribute to the fight against opacity and bias and enable ethical choices []. Transparent explanation layers can therefore bridge the divide between the model’s outputs and managers’ thinking, supporting the belief in AI systems integrated into project governance.

Future Architectures and Scalability: Our modular pipeline’s scalability enables expanding and adopting transformer-based models to process richer, unstructured content in the future. Nevertheless, Coovadia [] warns that sound AI governance frameworks should complement scaling to address accountability, oversight, and fairness. Therefore, governance maturity should be accompanied by technical scale-up.

To enhance the connection between the study evidence and its empirical utility, we have explained, through the study, the limits of the models’ reliability and how they apply to actual decision-making situations. In particular, the enhanced performance in Risk Category classification demonstrates that the tool is handy for high-level risk screening. On the other hand, the low performance in Impact prediction highlights areas in which human verification is important. Having such distinctions made explicit allows stakeholders to know when model outputs are usable autonomously and when they need to be supplemented with expert judgment. Furthermore, interpretable models are of increasing interest and attention for their remarkable contribution to transparency, as project managers can trace the effects of a particular textual hint on predictions, which builds credibility within the project’s environment and enables better decision-making and governance of individual textual hints on predictions, thereby enhancing trust and enabling more informed project governance decisions.

4.5. Future Considerations

The findings of this article indicate that AI-centered instruments can help anticipate triggers and categories when dealing with unstructured risk descriptions; however, they may still be limited in capturing the more subtle influences of risk.

Our findings extend earlier benchmarking studies by demonstrating not only the classification performance of NLP models but also their interpretability boundaries. Compared with prior LLM-based risk classification research, our model emphasizes structured outputs and domain transparency, thereby improving stakeholder trust and practical usability.

The following research ought to work on solving these problems by using context-sensitive embedding like those offered by BERT or GPT models to improve the learning of subtle associations between risk, triggers, and effects. The analysis of multi-label classification techniques might help gain a more refined insight into the multidimensionality of risks as well. Additional information should also be provided with the real project logs in other industries that have been adopted in the real world to increase the overall generalizability and strength of the system [,]. Finally, the usefulness of AI in project risk management can be made more practical with the help of the model being incorporated within the decision-support dashboards, where interactive visualizations can be implemented, allowing the managers to evaluate, track, and reduce the risks, preventing the occurrence of the risks in the first place. For example, the comprehensive and comparative approach to complex systems demonstrates the relevance of assessing the reliability of time-varying components to reduce risks and uncertainty [].

5. Conclusions

This paper aimed to discuss how artificial intelligence (AI) and Natural Language Processing (NLP) can revolutionize project risk management by automating the process of risk classification, prediction of risk type, risk triggers, and risk impacts. By critically reviewing various machine learning models, such as Logistic Regression, Support Vector Machines (SVMs), Random Forest, and XGBoost, and feature extractors, such as TF-IDF and Word Embeddings, the study has shown that AI-based methods can be very accurate in detecting risk information when the description is made in a text only format. This addresses the first type of research question, demonstrating that predictive models can accurately interpret unstructured risk information and provide actionable insights to decision-makers.

The second research question was the comparative analysis of models and the method of feature extraction, and it was found that Word Embeddings with tree-based algorithms (e.g., XGBoost) outperformed simpler methods in terms of predictive accuracy and generalizability. The results indicate the importance of applying the semantically rich representations to generalize the particulars of the project risk documentation, proving the point that AI should be introduced in the project management environment. This study addresses the third research question, specifically, the issue of interpretability. The explainable AI models included in the study (e.g., SHAP) were selected because they result in not only accurate but also transparent models, which will enable project managers to understand how the models make predictions. This will provide the user with confidence, which is vital in striking a balance between technical and managerial decisions.

To meet its aims, this study has formulated and tested an efficient AI-based framework that could be used to derive and anticipate risk-related information using unstructured data. It offers practical advice on the choice of the most effective method of feature extraction and machine learning models, providing a systematic comparison of the performance of these methods. It showed that it is possible to combine interpretability tools to aid in making decisions, thus gaining more trust in AI-based solutions. It defined methods of implementation, which prepare the way towards proactive and scalable risk management systems. Ultimately, the project will help shift project risk management towards a proactive, information-driven process, rather than a document-driven, reactive one.

These findings support the idea that AI and NLP technologies can serve as an effective competitive edge, as they enable the identification of risks early, informed decision-making, and a positive influence on the project’s finalization. The future research that can be conducted is to apply this framework to larger and domain-specific data, to real-time project monitoring, and to collaborative studies on hybrid methods to integrate structured and unstructured risk data.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.F. and A.B.-S.; methodology, K.F. and A.-G.N.; software, A.-G.N.; validation, A.B.-S. and A.-G.N.; formal analysis, A.-G.N.; investigation, K.F.; resources, K.F. and A.B.-S.; data curation, A.-G.N.; writing—original draft preparation, K.F.; writing—review and editing, A.B.-S.; visualization, K.F. and A.-G.N.; supervision, A.B.-S.; project administration, A.B.-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used Perplexity Pro (o3-Pro) to polish and clarify certain conceptual ideas. The authors have thoroughly reviewed and edited all generated content and take full responsibility for the final version of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| XGBoost | Extreme Gradient Boosting |

| NLP | Natural Language Processing |

| KBR | Knowledge-Based Reasoning |

| OA | Optimization Algorithms |

| CV | Computer Vision |

| GBDT | Gradient Boosting Decision Tree |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| XAI | Explainable Artificial Intelligence |

| LDA | Latent Dirichlet Allocation |

| NER | Named Entity Recognition |

| BERT | Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers |

| SHAP | Shapley Additive Explanations |

| TF-IDF | Term Frequency–Inverse Document Frequency |

| XGB Classifier | Extreme Gradient Boosting Classifier |

| SMOTE | Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique |

References

- Elseknidy, M.; Al-Mhdawi, M.; Qazi, A.; Ojiako, U.; Mahammedi, C.; Pour Rahimian, F. Developing a sustainability-driven risk management framework for green building projects: A literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 519, 145891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalogiannidis, S.; Kalfas, D.; Papaevangelou, O.; Giannarakis, G.; Chatzitheodoridis, F. The role of artificial intelligence technology in predictive risk assessment for business continuity: A case study of Greece. Risks 2024, 12, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, Y.; Marchena, J.; Awlla, A.H.; Li, J.J.; Abdalla, H.B. The AI-Powered evolution of big data. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shobanke, M.; Bhatt, M.; Shittu, E. Advancements and future outlook of Artificial Intelligence in energy and climate change modeling. Adv. Appl. Energy 2025, 17, 100211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimzai, I.A.; Mohammadi, M.Q. The Integration of Artificial Intelligence in Project Management: A Systematic Literature Review of emerging trends and challenges. TIERS Inf. Technol. J. 2024, 5, 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, K.; Zhu, Z.; Mbachu, J.; Ghanbaripour, A.; Moorhead, M. Artificial intelligence in risk management within the realm of construction projects: A bibliometric analysis and systematic literature review. J. Innov. Knowl. 2025, 10, 100711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, R.; Bryde, D.J.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Graham, G.; Foropon, C. Impact of artificial intelligence-driven big data analytics culture on agility and resilience in humanitarian supply chain: A practice-based view. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2022, 250, 108618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebayo, Y.; Udoh, P.; Kamudyariwa, X.B.; Osobajo, O.A. Artificial Intelligence in Construction Project Management: A Structured literature review of its evolution in application and future trends. Digital 2025, 5, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakoma, P.; Nyimbili, P.H.; Tembo, M.; Mwanaumo, E.M. A performance forecasting model for optimizing CDF-Funded construction projects in the Copperbelt Province, Zambia. J. Contemp. Urban Aff. 2025, 9, 290–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sinan, M.A.; Bubshait, A.A.; Aljaroudi, Z. Generation of Construction Scheduling through Machine Learning and BIM: A Blueprint. Buildings 2024, 14, 934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieland-Jorna, Y.; van Kooten, D.; A Verheij, R.; de Man, Y.; Francke, A.L.; Oosterveld-Vlug, M.G. Natural language processing systems for extracting information from electronic health records about activities of daily living. A systematic review. JAMIA Open 2024, 7, ooae044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kineber, A.F.; Elshaboury, N.; Oke, A.E.; Aliu, J.; Abunada, Z.; Alhusban, M. Revolutionizing Construction: A Cutting-Edge Decision-Making model for artificial intelligence implementation in sustainable building projects. Heliyon 2024, 10, e37078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, S.; de Arroyabe, J.C.F.; Sena, V.; Gupta, S. Stakeholder diversity and collaborative innovation: Integrating the resource-based view with stakeholder theory. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 164, 113955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, M.M.; Esaam, R. Revitalization approaches to maximize heritage urban DNA characteristics in declined cities: Foah City as a case study. J. Contemp. Urban Aff. 2023, 7, 56–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Dai, T.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhao, E. GBDT-IL: Incremental Learning of gradient boosting decision trees to detect botnets in Internet of Things. Sensors 2024, 24, 2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarker, I.H. AI-Based modeling: Techniques, applications and research issues towards automation, intelligent and smart systems. SN Comput. Sci. 2022, 3, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakaria, M.; Lynda, D.; Ramdane, B. Bagging Ensemble Based on Multi-Layer Perceptron Neural Network for Landslide Susceptibility Assessment. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Earth Observation and Geo-Spatial Information (ICEOGI), Algiers, Algeria, 22–24 May 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin Rashid, A.; Kausik, A.K. AI Revolutionizing Industries Worldwide: A comprehensive overview of its diverse applications. Hybrid Adv. 2024, 7, 100277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasetyo, M.L.; Peranginangin, R.A.; Martinovic, N.; Ichsan, M.; Wicaksono, H. Artificial Intelligence in Open Innovation Project Management: A Systematic literature review on technologies, applications, and integration requirements. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2024, 11, 100445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dritsas, E.; Trigka, M. Exploring the intersection of machine learning and big Data: A survey. Mach. Learn. Knowl. Extr. 2025, 7, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagannathan, M.; Roy, D.; Delhi, V.S.K. Application of NLP-based topic modeling to analyse unstructured text data in annual reports of construction contracting companies. CSI Trans. ICT 2022, 10, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salimimoghadam, S.; Ghanbaripour, A.N.; Tumpa, R.J.; Rahimi, A.K.; Golmoradi, M.; Rashidian, S.; Skitmore, M. The rise of Artificial intelligence in project Management: A Systematic literature review of current opportunities, enablers, and barriers. Buildings 2025, 15, 1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soori, M.; Jough, F.K.G.; Dastres, R.; Arezoo, B. AI-Based Decision Support Systems in Industry 4.0, a review. J. Econ. Technol. 2024, 4, 206–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, Z.; Alizadehsani, R.; Cifci, M.A.; Kausar, S.; Rehman, R.; Mahanta, P.; Bora, P.K.; Almasri, A.; Alkhawaldeh, R.S.; Hussain, S.; et al. A review of Explainable Artificial Intelligence in healthcare. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2024, 118, 109370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Bouri, R.; Taylor, T.; Youssef, A.; Zhu, T.; A Clifton, D. Machine learning in patient flow: A review. Prog. Biomed. Eng. 2021, 3, 022002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jada, I.; Mayayise, T.O. The impact of artificial intelligence on organisational cyber security: An outcome of a systematic literature review. Data Inf. Manag. 2023, 8, 100063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Amiery, A. The ethical implications of emerging AI technologies in healthcare. MedMat 2025, 2, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, N.; Touran, A.; Wang, Q.; Beauchamp, N. Construction risk identification using a multi-sentence context-aware method. Autom. Constr. 2024, 164, 105466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikmen, I.; Eken, G.; Erol, H.; Birgonul, M.T. Automated construction contract analysis for risk and responsibility assessment using natural language processing and machine learning. Comput. Ind. 2025, 166, 104251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boamah, F.A.; Jin, X.; Senaratne, S.; Perera, S. AI-driven risk identification model for infrastructure project: Utilising past project data. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 283, 127891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supriyono; Wibawa, A.P.; Suyono; Kurniawan, F. Advancements in natural Language Processing: Implications, challenges, and future directions. Telemat. Inform. Rep. 2024, 16, 100173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eker, H. Natural Language Processing risk assessment application developed for marble quarries. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, X.; Li, G.; Hou, J.; Fan, C. Research on Automatic Classification of mine safety Hazards using Pre-Trained Language Models. Electronics 2025, 14, 1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.W.; Shin, Y.J.; Kim, K.J.; Kwon, S. Development of an automated construction contract review framework using large language model and domain knowledge. Buildings 2025, 15, 923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.-W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-Training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Minneapolis, MI, USA, 2–7 June 2019; Scientific Research Publishing: Irvine, CA, USA, 2019; pp. 4171–4186. Available online: https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=3984485 (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Jim, J.R.; Talukder, A.R.; Malakar, P.; Kabir, M.; Nur, K.; Mridha, M. Recent advancements and challenges of NLP-based sentiment analysis: A state-of-the-art review. Nat. Lang. Process. J. 2024, 6, 100059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feretzakis, G.; Vagena, E.; Kalodanis, K.; Peristera, P.; Kalles, D.; Anastasiou, A. GDPR and large language models: Technical and legal obstacles. Futur. Internet 2025, 17, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saki, S.; Soori, M. Artificial intelligence, machine learning and deep learning in advanced transportation systems, a review. Multimodal Transp. 2025, 5, 100242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, A.; Nene, M.J. A five-layer framework for AI governance: Integrating regulation, standards, and certification. Transform. Gov. People Process Policy 2025, 19, 535–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Reniers, G.; Yang, M. A multidisciplinary review into the evolution of risk concepts and their assessment methods. Processes 2024, 12, 2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassija, V.; Chamola, V.; Mahapatra, A.; Singal, A.; Goel, D.; Huang, K.; Scardapane, S.; Spinelli, I.; Mahmud, M.; Hussain, A. Interpreting Black-Box Models: A review on Explainable Artificial intelligence. Cogn. Comput. 2023, 16, 45–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantanowitz, L.; Hanna, M.; Pantanowitz, J.; Lennerz, J.; Henricks, W.H.; Shen, P.; Quinn, B.; Bennet, S.; Rashidi, H.H. Regulatory aspects of AI-ML. Mod. Pathol. 2024, 37, 100609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamantiadou, D.S.; Tsironis, L. Leveraging Artificial intelligence in Project Management: A Systematic review of applications, challenges, and future directions. Computers 2025, 14, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigar, M.; Juli, J.F.; Golder, U.; Alam, M.J.; Hossain, M.K. Artificial intelligence and technological unemployment: Understanding trends, technology’s adverse roles, and current mitigation guidelines. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2025, 11, 100607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PMI. Risk Management in Portfolios, Programs, and Projects: A Practice Guide|Project Management Institute. 2021. Available online: https://www.pmi.org/standards/risk-management-in-portfolios (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Manning, C.D.; Schütze, H.; Raghavan, P. Introduction to Information Retrieval; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, P.; Cardoso, F.; Váz, P.; Silva, J.; Abbasi, M. Performance and scalability of data cleaning and preprocessing tools: A benchmark on large Real-World datasets. Data 2025, 10, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]