1. Introduction

Fostering critical thinking and rhetorical competence are cornerstones of English higher education [

1]. A key pedagogical instrument in this endeavor is the provision of diagnostic, formative feedback on argumentative writing. For second-language (L2) learners, who must concurrently master linguistic conventions and logical principles, such feedback is especially critical [

2,

3]. However, delivering this type of nuanced, individualized guidance at scale represents a formidable systemic challenge for educational institutions, prompting significant investigation into the design of intelligent educational systems [

4].

Initial forays into this domain were dominated by the psychometric paradigm of Automated Essay Scoring (AES) [

5]. These early-generation systems, whether based on hand-engineered linguistic features or deep learning models, were engineered to predict a holistic score that correlates with human expert judgment [

6]. While useful for summative assessment, their pedagogical utility is constrained because they are fundamentally agnostic to the logical soundness of the argument [

7]. They operate on statistical proxies for writing quality—such as lexical diversity, syntactic complexity, or the presence of cohesion markers—rather than on a formal model of reasoning. Consequently, a student is told how well they have written, but not why their argument succeeds or fails.

The recent advent of the generative paradigm, powered by Large Language Models (LLMs), has opened new avenues. LLMs possess an unprecedented capacity for fluent and contextually-aware text generation, enabling them to produce feedback in natural language [

8]. Yet, this fluency often belies a critical weakness: a lack of grounded, verifiable reasoning. LLMs excel at generating semantically plausible prose, but they lack an explicit, internal model of logical validity [

9]. As a result, their feedback often consists of high-level stylistic heuristics (e.g., “strengthen your claim”) without a causal diagnosis of a specific structural defect, leading to suggestions that are plausible but ultimately unactionable [

10].

Concretely, these developments leave at least two practical problems unsolved in current writing instruction. First, most existing systems either provide only holistic scores (AES) or surface-level suggestions on grammar and style (LLM-based tools), but they do not diagnose whether the logical structure of the argument is sound. As a result, students often receive feedback about “how well” they wrote instead of “where and why” their reasoning breaks down. Second, teachers face a scalability bottleneck: delivering detailed, argument-focused feedback at scale is extremely time-consuming, especially in L2 contexts where cohorts are large and the need for formative support is high. These two problems are pedagogically crucial because structural weaknesses in reasoning—such as unsupported claims, irrelevant premises, or missing counterarguments—directly undermine students’ critical thinking development, yet they are precisely the aspects that current automated systems struggle to target.

This paper argues for a neuro-symbolic synthesis to transcend the limitations of these two paradigms. Our central thesis is that robust, reliable, and pedagogically valuable feedback must be conditioned on an explicit, symbolic representation of an essay’s argumentative structure. We conceptualize this as a semantic-to-symbolic-to-semantic pipeline. First, the unstructured semantics of the essay are converted into a formal symbolic structure—an argument graph. This graph is then subjected to rigorous symbolic reasoning. Crucially, the topology of an argument graph is not arbitrary; it encodes logical dependencies. Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) [

11], through iterative message-passing, are uniquely capable of performing relational reasoning on this structure. They can learn to identify structural motifs—such as isolated claim nodes (unsupported assertions) or disjoint subgraphs (irrelevant lines of reasoning)—that serve as direct, machine-readable analogues of well-defined argumentative flaws. The findings of this symbolic analysis are then converted back into the semantics of natural language feedback.

We operationalize this vision in ARGUS, a GNN-guided framework for generating actionable feedback. ARGUS executes our proposed pipeline in three integrated stages: (1) An LLM-based Argument Graph Parser performs the initial semantic-to-symbolic conversion, transforming the raw essay text into a directed, multi-relational argument graph. (2) This symbolic blueprint is then passed to a Relational Graph Convolutional Network (R-GCN) [

12], our Structural Flaw Detector, which conducts a structural audit to identify nodes or subgraphs that violate principles of sound argumentation. (3) Finally, the precise location and type of these detected flaws, encoded as a compact vector embedding, serve as a direct conditioning signal for a second LLM, the Guided Feedback Generator. This final symbolic-to-semantic step generates feedback that is causally anchored to a specific, diagnosed structural defect.

Against this background, our goal is to build an automated feedback system that (i) reasons explicitly over a student’s argumentative structure, rather than relying only on surface text features, and (ii) translates this reasoning into concrete, revision-oriented guidance at a scale that is infeasible for human teachers alone. ARGUS instantiates this goal through a semantic-to-symbolic-to-semantic pipeline: it converts essays into argument graphs, performs graph-based diagnosis of structural flaws, and then conditions an LLM on these flaws to generate targeted feedback.

Our primary contributions are threefold:

We design and implement ARGUS, a novel end-to-end neuro-symbolic system engineered to generate fine-grained, structurally-aware feedback. We detail its modular architecture and the systemic integration of its components, presenting a representative instantiation of GNN-guided conditional generation for Automated Writing Evaluation (AWE).

We demonstrate the efficacy of a GNN-guided generation process, where structural flaw embeddings from an R-GCN are used to steer an LLM, resulting in feedback that is significantly more specific and actionable than that from a standalone LLM or models conditioned on non-graphical structural representations.

Through extensive experiments and human evaluation, we show that ARGUS not only achieves high accuracy in the underlying argument mining task but also produces feedback that is judged by human experts as substantially more helpful for student revision.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 reviews related work in automated writing evaluation and argument mining.

Section 3 provides a detailed description of the ARGUS framework and its components.

Section 4 outlines our experimental setup, including the dataset, baselines, and evaluation metrics.

Section 5 presents and analyzes our quantitative and qualitative results. Finally,

Section 6 discusses the implications and limitations of our work and offers concluding remarks.

2. Related Work

Our research is situated at the intersection of three synergistic fields. Automated Writing Evaluation (AWE) provides the educational motivation; Argument Mining supplies the theoretical and technical foundation for understanding argumentative structure; and Neuro-Symbolic AI offers the paradigm for integrating structured reasoning with fluent language generation.

2.1. Automated Writing Evaluation (AWE)

Historically, AWE systems such as e-rater [

13] and the Intelligent Essay Assessor [

14] have focused on holistic scoring using linguistic features or, more recently, deep learning [

15]. While this approach is useful for summative assessment, it provides limited formative value because it is agnostic to the logical soundness of the argument and often functions as a “black box.” A growing body of work now provides formative feedback, but it typically targets sentence-level revisions such as grammatical error correction [

16] or cohesion [

17], seldom addressing the macro-structure of the argument. Our work directly targets this critical gap by providing feedback grounded in the essay’s underlying logical topology.

2.2. Argument Mining

Argument Mining (AM) aims to extract argumentative components (e.g., claims, premises) and their relations (e.g., support, attack) [

18,

19]. Methodologies have evolved from feature-based models and neural sequence labelers [

20] to text-to-text generation, which better captures global graph structures by generating a linearized representation [

21]. We adopt this powerful text-to-graph paradigm for our parser. However, where most AM work stops at extraction, our work takes the crucial next step: using the extracted structure to diagnose flaws and generate pedagogically useful feedback.

2.3. Neuro-Symbolic AI for Text

Neuro-Symbolic AI seeks to combine the pattern recognition of neural networks with the explicit reasoning of symbolic systems [

22], such as using knowledge graphs to ground LLMs [

23]. Similar cross-modal feature enhancement strategies have also proven effective in other fields, such as video saliency prediction via feature enhancement and temporal recurrence [

24], and spatiotemporal dual-branch fusion for driver attention prediction [

25], where dual branches encode complementary spatial and temporal cues in a way analogous to our semantic–structural pipeline. Our work focuses on a specific subdomain: GNN-guided text generation. In this paradigm, a GNN first reasons over a graph to produce a meaningful embedding, which then serves as a direct conditioning signal for an LLM’s generation process. This approach, proven effective in structured domains like code synthesis [

26], allows us to apply a GNN-guided framework to writing feedback. By using an R-GCN to explicitly identify structural flaws and encode this information, we ensure the resulting feedback is causally linked to a diagnosed weakness. Closely related in spirit, Yuan et al. introduce G-TEx, a graph-guided textual explanation framework in which a GNN encodes highlight graphs to condition an encoder–decoder LLM and improve the faithfulness of natural language explanations, providing independent evidence that graph-guided generation can strengthen factual grounding in text [

27].

2.4. LLM-with-Structure in Writing Feedback

Recent work has begun to inject discourse structure, like Rhetorical Structure Theory (RST) trees, to provide feedback on coherence and organization [

28]. This approach, however, does not diagnose the logical validity of argumentative moves. Furthermore, these tree structures are typically linearized or embedded rather than analyzed graph-theoretically. In contrast, ARGUS operates on an argument graph, using a GNN to reason about non-hierarchical dependencies (e.g., cycles, missing supports) and diagnose verifiable logical defects.

Other systems integrate argument-centric structure, such as linear sequences of Argumentative Units (AUs), and use LLM prompting to provide formative guidance [

29]. These methods help students with component inclusion and local cohesion but do not perform global graph-based reasoning. Their integration is typically prompt-level conditioning on linearized components, whereas ARGUS propagates signals over a global argument graph via a GNN to perform topology-aware flaw diagnosis.

Complementary to our design, Miandoab et al. propose IntelliProof, an argumentation-network-based, structured, LLM-driven framework that explicitly models claims and support relations to guide feedback for English essays, further underscoring the value of combining symbolic argument structure with large language models in educational settings [

30].

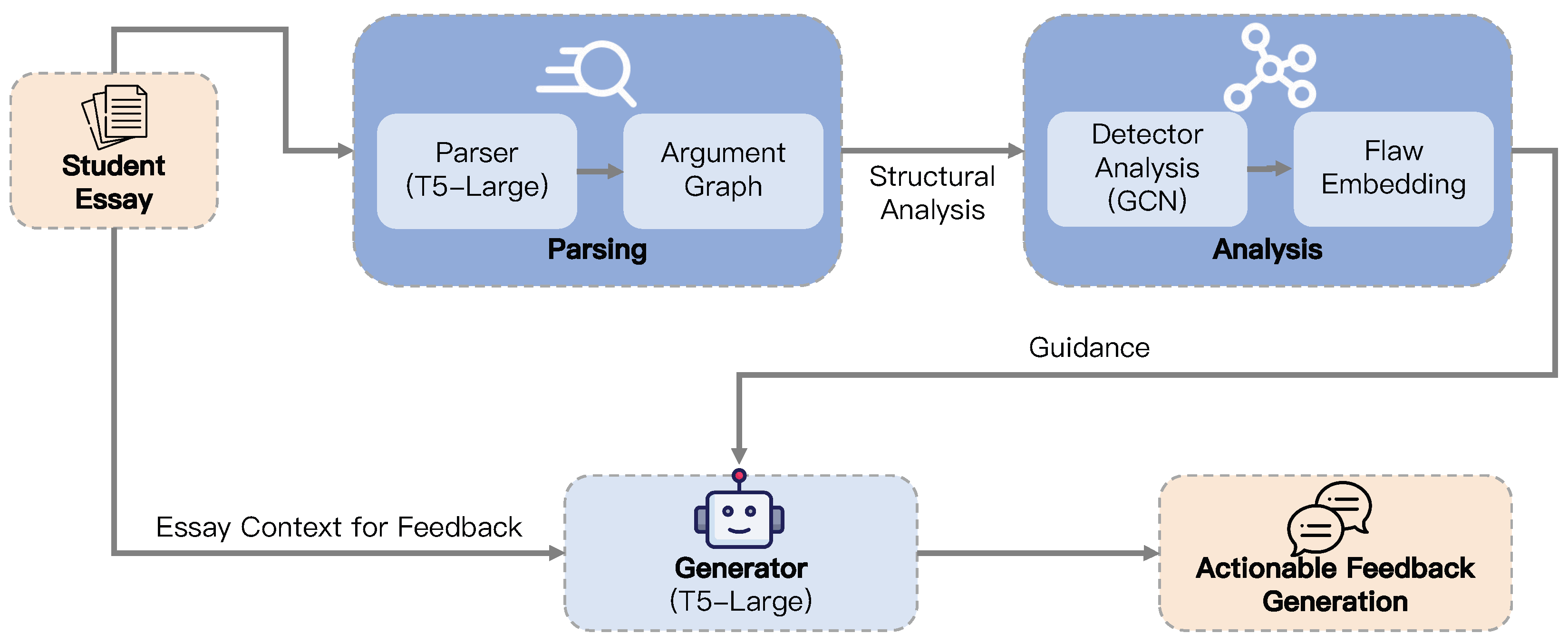

3. The ARGUS System Architecture

The ARGUS system operationalizes our neuro-symbolic philosophy through a multi-stage data processing pipeline that transforms a raw student essay into targeted, structurally-aware feedback. The system’s architecture is engineered to emulate the cognitive workflow of an expert writing instructor: first, deconstructing the argument’s logic; second, diagnosing specific reasoning errors; and finally, articulating constructive, actionable advice. This integrated system consists of three core modules, as illustrated in

Figure 1.

3.1. Module 1: Argument Graph Parsing Subsystem

The initial stage converts the unstructured essay text, a sequence of tokens

, into a formal, machine-readable argument graph

. We formulate this as a text-to-graph generation task, where a fine-tuned T5-Large model [

31] learns the mapping

. The model takes the full essay

E as input and generates a linearized, textual representation of the graph,

. This representation consists of a sequence of tuples defining argumentative components (ACs) and their relations. For example, the sentence “University education should be free because it promotes social equality” would be mapped to a string like: (AC1, Claim, “University education should be free”); (AC2, Premise, “it promotes social equality”); (Relation, AC2, supports, AC1).

This generative approach is more flexible than traditional token-level classification, as it can naturally handle nested or overlapping components and complex relational structures. Pedagogically, this stage is critical as it translates the student’s prose into a formal blueprint of their reasoning, making their logic amenable to the objective, automated analysis that follows. In contrast to purely token-level models, this explicit graph construction step makes subsequent reasoning modules aware of which spans function as claims or premises and how they are connected.

3.2. Module 2: Structural Flaw Detection Subsystem

Once the argument graph is constructed, the second stage analyzes its topology and semantics to identify logical weaknesses. We use a Relational Graph Convolutional Network (R-GCN) [

32], which is adept at handling multi-relational graphs like ours. The graph nodes are the ACs, and the edges are the ‘supports’ and ‘attacks’ relations.

Node initialization. Before the message-passing process, each node i in the graph is initialized with a rich semantic representation derived from its corresponding text span, . We use a pre-trained sentence-transformer to compute an initial embedding for each node: . This step ensures that the GNN’s structural reasoning is informed by the semantic content of each claim and premise.

Relational message passing. The R-GCN then iteratively updates each node’s hidden representation,

, by aggregating messages from its neighbors across

L layers. The core propagation rule for layer

l is:

where

is the set of neighbors of node

i under relation

,

is a relation-specific learnable weight matrix, and

is a normalization constant. The relation-specific transformation is crucial for distinguishing between the logical functions of ‘supports’ and ‘attacks’.

Hybrid flaw prediction. After L layers of message passing, the system performs a hybrid diagnosis using two mechanisms:

- 1.

Topological flaw detection: We apply a set of graph-based algorithms and checks directly to the argument graph G to identify flaws defined by structure and relations (e.g., ‘Unsupported Claim’, ‘Circular Reasoning’, ‘Missing Counterargument’). These checks are explicit, verifiable, and do not rely on the GNN’s learned embeddings.

- 2.

Semantic flaw detection: We use the final node embeddings (which are now enriched with structural context from the GNN) to detect node-level semantic issues. For example, a classifier is trained to predict the probability of ‘Vague Evidence’ based on the final embedding of a ‘Premise’ node: .

The complete, expanded taxonomy of seven flaws is detailed in

Table 1. The final output of this module is the flaw embedding

, a vector representation derived from the GNN’s graph-level embedding

and concatenated with a one-hot vector indicating which specific flaws were detected. This rich embedding serves as the conditioning signal for Module 3. By separating topological checks from embedding-based classifiers, the detector remains both interpretable at the graph level and sensitive to subtle semantic cues within individual components. The entire process is detailed in Algorithm 1.

The operational thresholds, such as requiring at least two distinct branches to support a thesis (

), are based on common pedagogical rubrics.

We recognize that these static values may not generalize perfectly across all contexts.

However, this highlights a key advantage of our neuro-symbolic design over end-to-end black-box models: these thresholds are transparent, interpretable, and easily modifiable.

In a future deployment, this value

k could be exposed as a configurable parameter, allowing instructors to adapt the system to diverse assignments or instructional standards (e.g., requiring

for a graduate-level paper).

While a full sensitivity analysis of these thresholds (e.g., varying

k) is a valuable direction for future work, we used a fixed, pedagogically-grounded value (

) for this study.

| Algorithm 1 Structural Flaw Detection via R-GCN |

| Require: Argument Graph ; Component text spans |

| Ensure: Flaw Embedding ; List of Detected Flaws |

| 1: Initialize node embeddings where for each node |

| ▹ Message Passing Layers

|

| 2: for layer to do |

| 3: for each node i in V do |

| 4: |

| 5: for each relation type r in do |

| 6: for each neighbor j of i with relation r do |

| 7: |

| 8: end for |

| 9: end for |

| 10: |

| 11: end for |

| 12: end for |

| ▹ Flaw Prediction Layer |

| 13: |

| 14: |

| 15: |

| 16: |

| |

| 17: return |

3.3. Module 3: Guided Feedback Generation Subsystem

The final stage generates natural language feedback,

. This stage uses the same T5-Large architecture but operates in a conditional generation setting, guided by the GNN’s output. The model’s objective is to maximize the conditional probability of the feedback given the original essay

E and the flaw embedding

:

To achieve this, the flaw embedding

is integrated directly into the T5 decoder’s attention mechanism. At each decoding step, the decoder attends not only to the encoded representation of the essay text but also to the structural flaw information encapsulated in

. This is typically implemented by projecting

and prepending it to the sequence of encoder hidden states that the decoder’s cross-attention mechanism attends to. This GNN-guided approach ensures that the feedback is causally anchored to a verifiable structural weakness. From a pedagogical standpoint, this mirrors the concept of scaffolding within a student’s Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD). The GNN identifies a precise area for improvement, and the LLM provides the targeted linguistic support necessary for the student to bridge that gap. As a result, the generated comments are not only fluent but also explicitly tied to identifiable weaknesses in the argument graph, helping students understand both what to revise and why the revision is needed.

4. Experimental Setup

4.1. Dataset

We used the Argument Annotated Essays (AAE-v2) corpus [

33], a dataset of L2 English persuasive essays with the standard train/validation/test split.

To improve coverage of rarer structural flaw types and strengthen our models, we additionally collected 150 L2 persuasive essays from the same population; 120 essays were added to the training set and 30 to the test set. These essays were first parsed with the original ARGUS parser and then manually corrected to obtain high-quality argument graphs.

The augmented corpus is used for training and evaluating both the argument parser (Module 1) and the R-GCN flaw detector (Module 2).

To train the R-GCN flaw detector, we manually labeled flaw instances in the original AAE-v2 training graphs and in the 120 additional training essays, resulting in a total of 220 labeled argument graphs for the flaws defined in

Table 1.

This annotation procedure achieved high inter-annotator agreement (Cohen’s

).

4.2. Baselines

We compared the feedback generated by ARGUS against seven baselines:

Rule-Based: A system providing feedback based on simple heuristics, such as checking for the presence of keywords like “for example” or “because” as proxies for evidence.

Fine-tuned T5-Large (T5-FT): Our Stage 3 generator model but without the GNN-based flaw embedding as a conditioning input. It is fine-tuned on the same essay-feedback pairs as ARGUS but relies solely on the essay text.

RST-Guided T5 (RST-T5): A baseline conditioned on a non-graphical discourse structure. It parses the essay into an RST tree, encodes the linearized tree, and prepends this vector to the T5 decoder, guiding generation based on discourse flow rather than argumentative logic.

GEC + Coherence LLM (GEC+Coh-LLM): To represent the capabilities of sophisticated, real-world AWE tools that focus on surface-level and discourse-level issues, we constructed a reproducible composite baseline. This pipeline first uses a state-of-the-art GEC model (GECToR) to correct grammatical errors. Then, it uses an RST parser to extract discourse features, which are fed into a GPT-4 prompt (distinct from our other GPT-4 baselines) designed to generate feedback only on grammar, style, and general coherence/flow, explicitly avoiding argumentative logic.

Linearized Graph-Prompt (T5-LGP): To directly challenge the contribution of our GNN’s reasoning module, this baseline uses the same argument graph generated by our Module 1 parser. However, instead of using a GNN, it linearizes this graph into a text sequence and prepends it to the T5-FT model’s input as a structured prompt. This baseline isolates the effect of providing symbolic structure as text versus as a reasoned embedding.

ToT-Structured Prompt (GPT-4-ToT): To compare our explicit neuro-symbolic approach with advanced prompting techniques, this baseline uses GPT-4 (the same model as GPT-4-ZS) but provides it with a sophisticated multi-step, Tree-of-Thought (ToT)/chain-of-thought style prompt. The prompt instructs the model to first identify the main claim, then list all supporting premises, then critically evaluate each premise for logical flaws (e.g., unsupported, irrelevant), and finally synthesize these findings into feedback. This represents a strong, state-of-the-art “in-context reasoning” baseline that explicitly encourages step-by-step reasoning over the argument.

Zero-Shot GPT-4 (GPT-4-ZS): A state-of-the-art proprietary LLM, prompted with a carefully crafted zero-shot instruction to provide feedback on the student’s argumentative structure.

We selected these baselines over commercial AWE tools (e.g., Grammarly) for two reasons. First, commercial systems are proprietary “black boxes,” making reproducible comparison difficult. To address this gap while maintaining reproducibility, we have included the GEC+Coh-LLM composite baseline, which simulates the function of these tools by focusing on surface and coherence feedback. Second, while tools like our GEC+Coh-LLM baseline target grammar and style, ARGUS is designed to diagnose deep logical flaws. Therefore, our chosen baselines (T5-FT, RST-T5, GEC+Coh-LLM, T5-LGP, GPT-4-ToT, and GPT-4-ZS) represent a comprehensive and appropriate comparison for our specific task.

For the GPT-4-ZS, GPT-4-ToT, and GEC+Coh-LLM baselines, we experimented with several prompt variants (e.g., more explicit rubrics, stepwise reasoning instructions, and alternative decompositions of the task) and selected the best-performing prompts based on performance on the validation set. Nevertheless, the performance of these proprietary LLM baselines remains somewhat sensitive to prompt design, which we regard as an inherent limitation of our current evaluation. In contrast, ARGUS bases its behavior on an explicit, learned flaw-detection module and graph-grounded generator, making its diagnostic focus less dependent on the precise wording of natural-language instructions.

4.3. Software and Implementation Details

All models were implemented in Python 3.10 using the PyTorch 2.1.0 deep learning framework (Meta Platforms, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA). Transformers-based architectures such as T5-Large and FLAN-T5-XXL were accessed via the Hugging Face Transformers library (version 4.40.0; Hugging Face, Inc., New York, NY, USA). Sentence embeddings were obtained using the “all-mpnet-base-v2” and “e5-base-v2” checkpoints from the Sentence-Transformers library (version 2.3.0). GPT-4-based baselines and the LLM-as-a-Judge experiments were run through the OpenAI API using the gpt-4.1-preview model (OpenAI, San Francisco, CA, USA).

4.4. Evaluation Metrics

We evaluated our system in two phases: the performance of the argument mining pipeline and the quality of the final generated feedback.

Argument Mining Evaluation:

We evaluated the Argument Graph Parser using standard micro F1-scores for two sub-tasks: (1) Component Identification, which measures the ability to correctly identify the text spans and types of components, and (2) Relation Identification, which measures the ability to correctly classify the relationship between two given components.

Feedback Quality Evaluation: To ensure a robust and statistically powerful evaluation, we randomly selected 213 essays from the test set. We then recruited four expert annotators (all PhD candidates in Applied Linguistics with teaching experience) to rate the feedback on a 5-point Likert scale across four dimensions:

Specificity: Does the feedback refer to a concrete part of the student’s essay? (1 = Very Generic, 5 = Very Specific)

Accuracy: Is the identified weakness a genuine flaw in the argument? (1 = Inaccurate, 5 = Accurate)

Actionability: Does the feedback provide a clear, actionable suggestion for improvement? (1 = Not Actionable, 5 = Very Actionable)

Helpfulness: What is the overall pedagogical value of the feedback? (1 = Not Helpful, 5 = Very Helpful)

To explore scalable evaluation, we also test the use of LLM-as-a-Judge, using GPT-4 with a detailed rubric to score the feedback along the same dimensions and measure its correlation with human judgments.

To ensure the reliability and validity of our evaluation, we implemented a rigorous rating protocol. First, the four annotators participated in a training session where they jointly scored five sample feedback instances, discussing discrepancies until a consensus on the application of the rubric was reached. For the main evaluation, the feedback from all models for a given essay was presented to the annotators in a randomized and anonymized order. This double-blind setup prevented potential bias related to the source of the feedback or the order of presentation (i.e., primacy or recency effects). Each of the 213 essays, along with the corresponding feedback from all eight models, was rated by all four annotators.

Given the ordinal nature of the 5-point Likert scale, we used the non-parametric Wilcoxon signed-rank test for paired comparisons between ARGUS and each baseline model on the four evaluation metrics. We report non-parametric effect sizes using Cliff’s delta () along with their 95% confidence intervals to move beyond a reliance on p-values alone. All p-values were adjusted using the Holm–Bonferroni correction to rigorously control for the family-wise error rate across multiple comparisons. Inter-rater reliability (IRR) among the four annotators was assessed using Krippendorff’s alpha () for ordinal data, and we report this metric with its 95% confidence interval to demonstrate the stability of our judgments.

5. Results and Analysis

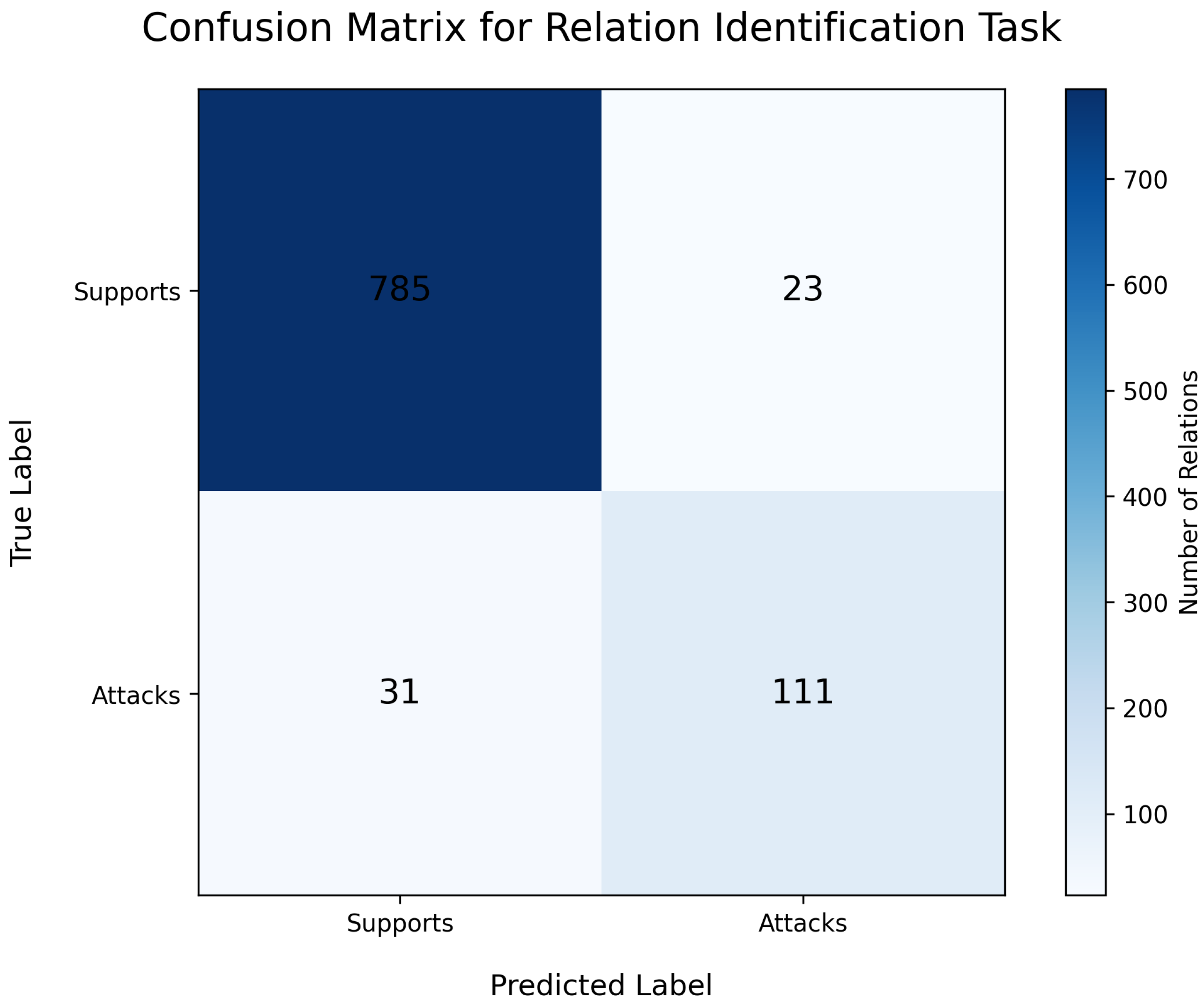

5.1. Argument Mining Performance and Robustness Analysis

The success of the entire ARGUS framework is predicated on the accuracy of its initial argument graph parsing stage.

Table 2 presents the performance of our T5-based parser on the AAE-v2 benchmark. Our model achieves F1-scores of 90.4% for component identification and 86.1% for relation identification, establishing a strong foundation for the GNN. These scores are obtained after augmenting the training split with 150 additional L2 essays (

Section 4), and they represent gains of +1.2 and +1.6 absolute F1 points over the original release of ARGUS for components and relations, respectively. The generative text-to-graph approach demonstrates an advantage by jointly modeling component and relation extraction, capturing complex, non-local dependencies. On parser-predicted argument graphs from the same expanded dataset, the R-GCN flaw detector achieves a macro-averaged F1-score of 0.83 across the seven flaw types, providing reliable structural supervision for downstream feedback generation.

The performance gap between component and relation identification is expected. Identifying components relies on local patterns, while relation identification is inferentially more complex. As the confusion matrix in

Figure 2 illustrates, the model’s primary error is distinguishing between the minority ‘attacks’ class and the majority ‘supports’ class, often due to subtle linguistic cues (see

Appendix E). Nevertheless, the high accuracy on the prevalent ‘supports’ relation is sufficient for constructing a dependable graph structure.

However, while the overall performance is strong, it is crucial to analyze the nature of the parser’s errors, as they directly impact the validity of the downstream feedback. A manual review of the 50 component predictions with the lowest confidence scores from our validation set revealed that the most common and consequential error is the misclassification of a ‘Premise’ as a ‘Claim’ (18 of 50 cases, 36%). This typically occurs when a premise is phrased assertively. Such errors are particularly problematic due to propagation: in 15 of these 18 instances, the misclassified premise was subsequently and correctly identified by the GNN as having no incoming support links, leading the system to generate incorrect feedback about an ‘Unsupported Claim’. This analysis underscores the “garbage in, garbage out” challenge and highlights the critical importance of parser accuracy, a point we revisit in our discussion of future work in

Section 6.

To further quantify the practical risk of this error propagation on our final feedback, we manually audited the parser’s output for the 50 essays used in our human evaluation. We identified a total of 43 parser errors (e.g., component or relation misclassifications) that had the potential to trigger an incorrect flaw diagnosis. We then cross-referenced these 43 potential errors with our human evaluation data from

Section 5.2. Of these 43 errors, we found that only 7 (16.3%) actually propagated and resulted in feedback that was rated as ‘Inaccurate’ (mean score < 3.0) by our human annotators. The remaining 36 errors (83.7%) were either ‘silent’ (did not trigger a GNN flaw) or the GNN’s graph-level reasoning was robust to the local error (e.g., a single misclassified relation did not change the overall ‘Under-supported Thesis’ diagnosis). This analysis suggests that while parser accuracy remains a critical dependency, our neuro-symbolic pipeline, particularly the GNN’s reasoning over the complete graph, provides a degree of robustness against the cascading impact of minor, localized parsing errors.

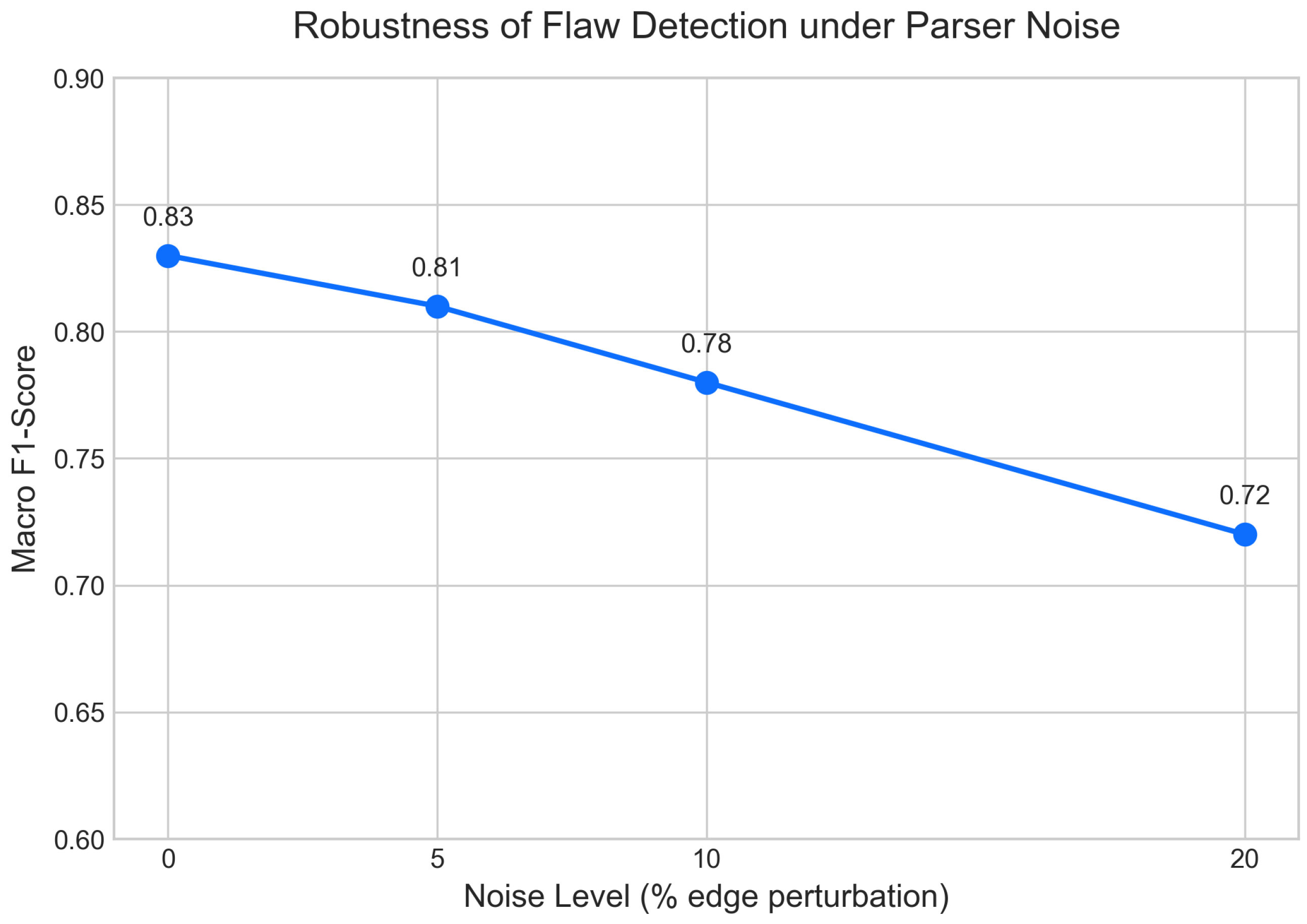

To supplement this manual audit with a more systematic stress test, we conducted a perturbation analysis on our GNN flaw detector (Module 2). As shown in

Table 3 and

Figure 3, we simulated parser errors by intentionally corrupting the argument graphs from the test set with increasing levels of random “edge noise” (i.e., adding, deleting, or mislabeling relations). The results demonstrate the system’s “graceful degradation.” At a 5% noise level, the Macro F1-score for flaw detection drops by only 2.0 percentage points (from 0.83 to 0.81). At a 10% noise level, the score remains 0.78, meaning the detector retains approximately 94% of its original performance, and even at a 20% noise level—a rate substantially higher than our parser’s observed error rate—the system still maintains a Macro F1-score of 0.72. This systematic analysis, combined with our manual audit, provides strong evidence that the GNN-based reasoning module is not “brittle” and can maintain high diagnostic utility even with imperfect, real-world parser outputs.

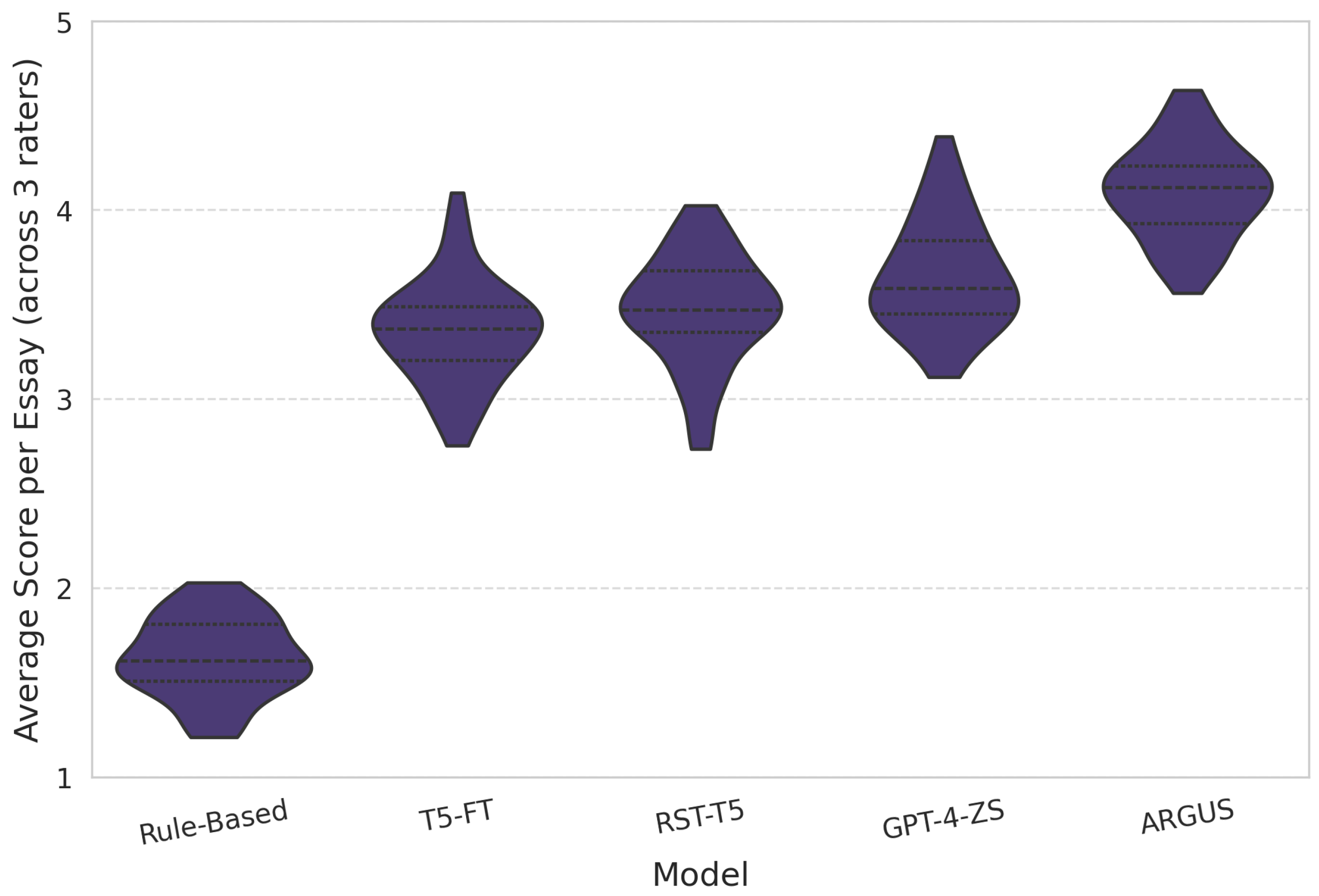

5.2. Feedback Quality: Human Evaluation

The ultimate measure of our system’s utility is the quality of the feedback it generates. Our evaluation is based on a large-scale human assessment of 213 essays, rated by four trained expert annotators, resulting in 852 ratings per model for each metric. Before analyzing the scores, we assessed the consistency of our expert judgments on this full dataset. The inter-rater reliability was found to be substantial (Krippendorff’s

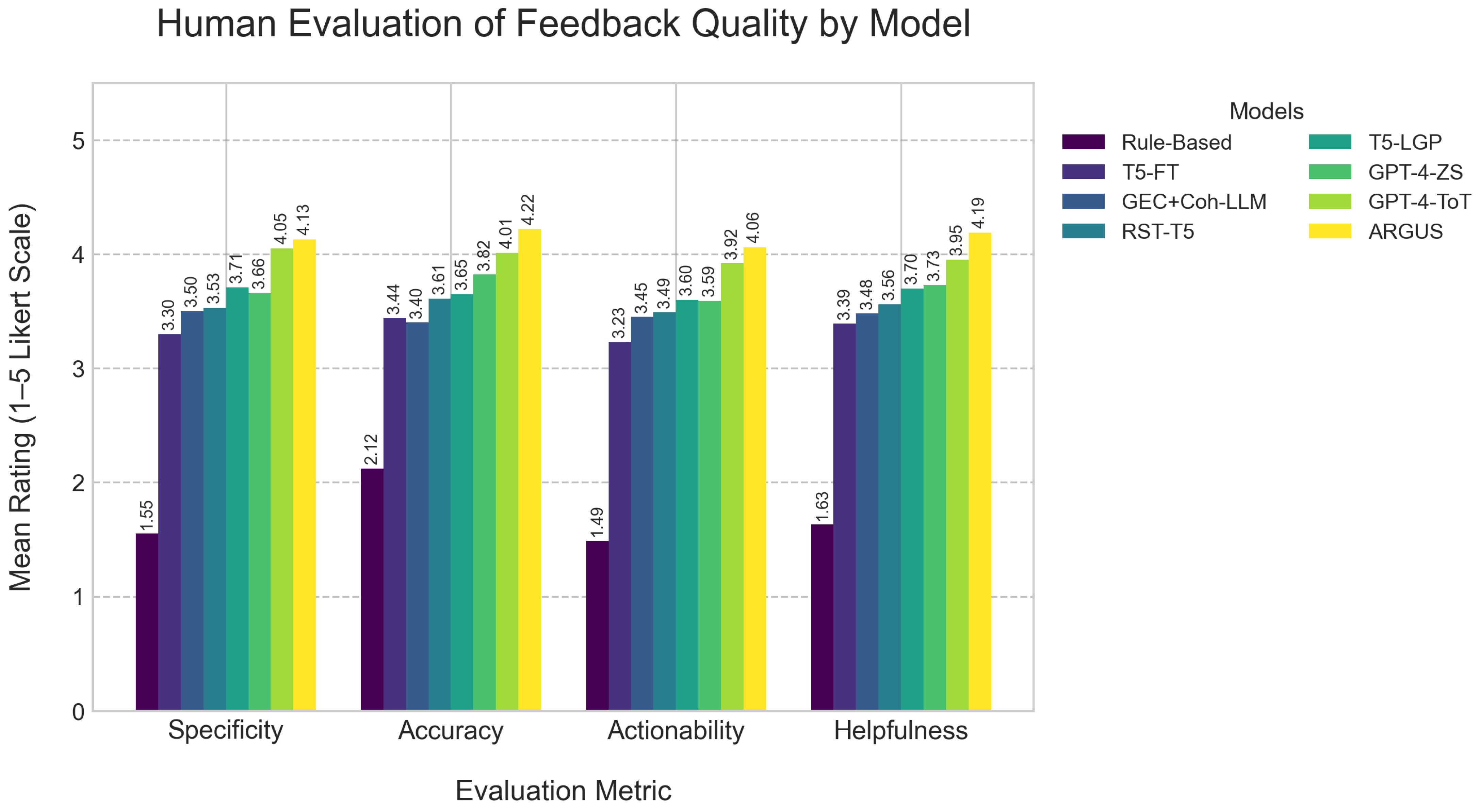

, 95% CI [0.71, 0.81]), indicating that the four annotators applied the scoring rubric with a high degree of consistency. The results of our large-scale human evaluation, presented in

Table 4, show that ARGUS provides a consistent and meaningful advantage over all baselines. Wilcoxon signed-rank tests confirmed that ARGUS was rated significantly higher than all other models, including the new, strong GPT-4-ToT and T5-LGP baselines, on all four metrics (all Holm–Bonferroni adjusted

, with all Cliff’s

effect sizes showing medium to large advantages). To provide a more granular view of these ratings, detailed visualizations of the score distributions on both a per-essay and per-rater basis are available in

Appendix F.

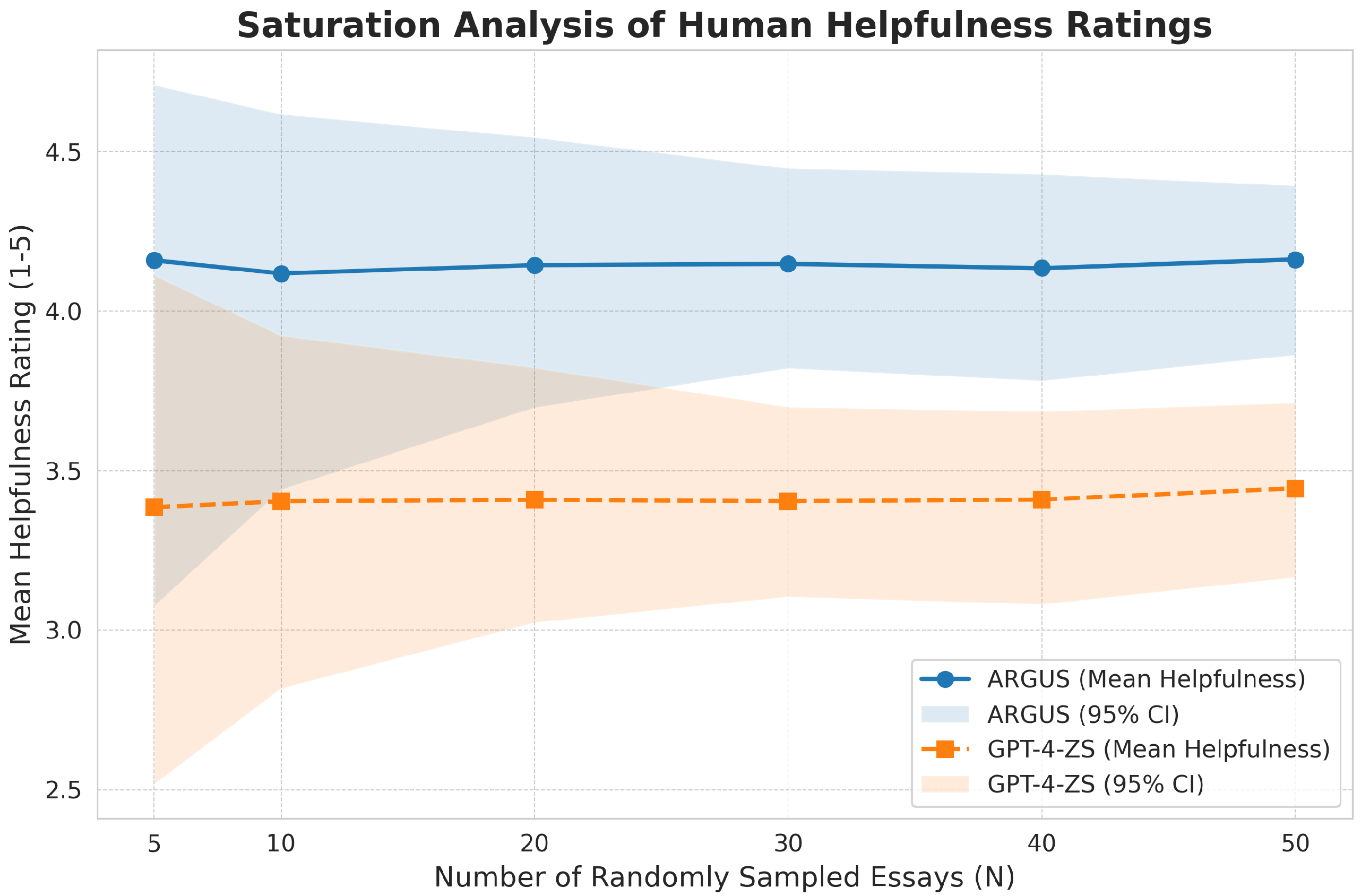

Figure 4 summarizes the mean human ratings for each model, and

Figure 5 illustrates how these results stabilize as the number of sampled essays increases.

A key finding from our new baselines is the comparison between ARGUS and T5-LGP (Linearized Graph-Prompt). The T5-LGP baseline, which provides the symbolic graph as mere text to the T5 model, performs significantly better than the standard T5-FT (), confirming that structural information is highly beneficial. However, ARGUS, which reasons over this graph with a GNN, significantly outperforms T5-LGP on all metrics, especially Accuracy (4.22 vs. 3.65) and Specificity (4.13 vs. 3.71). This comparison empirically demonstrates that our core contribution is not simply providing structure, but explicitly reasoning over it with the GNN module to produce a diagnostic flaw embedding.

Furthermore, we compared ARGUS to the powerful GPT-4-ToT baseline, which uses advanced in-context reasoning to simulate a flaw-finding process. While GPT-4-ToT is a very strong baseline that outperforms the zero-shot GPT-4-ZS (Accuracy 4.01 vs. 3.82; Helpfulness 3.95 vs. 3.73), ARGUS still achieves a statistically significant lead across all four metrics. Our qualitative analysis suggests this gap stems from the difference between explicit and implicit reasoning. The GNN-based diagnosis in ARGUS is more systematic and less prone to the stochastic failures of in-context reasoning, leading to feedback that is rated as consistently more Accurate (4.22 vs. 4.01) and pedagogically Helpful (4.19 vs. 3.95).

The inclusion of the GEC+Coh-LLM baseline provides an important contextual anchor. This model, which simulates commercial AWE tools, scores reasonably well on Specificity (3.50) and Actionability (3.45) because it correctly identifies surface-level errors. However, its Helpfulness score (3.48) is significantly lower than all argument-structure-aware models (), and its Accuracy (3.40) is among the lowest. This quantitatively confirms our hypothesis: systems that ignore deep argumentative logic, even if they are good at grammar and coherence, are rated by experts as less accurate and less helpful for the core task of improving argumentation.

The comparison with the T5-FT baseline further validates this point. Despite being fine-tuned on the same data, the unguided T5-FT model lags significantly behind all structure-aware models. This highlights the limitations of a purely correlational approach; lacking an explicit reasoning model, T5-FT learns to associate text features with feedback but often defaults to plausible but generic suggestions. The superior Accuracy score of ARGUS (4.22) is particularly noteworthy, confirming that the GNN-identified flaws correspond to genuine pedagogical weaknesses.

Feedback length was not explicitly controlled during generation. However, a post-hoc analysis revealed comparable average token counts for the main generative models (ARGUS: 63 tokens; GPT-4-ZS: 71 tokens; T5-FT: 55 tokens; RST-T5: 58 tokens), suggesting that observed differences in quality are not merely an artifact of verbosity. The Rule-Based feedback was naturally much shorter (avg. 16 tokens).

5.3. Ablation: GNN Reasoning vs. Structured Prompting

To rigorously quantify the unique contribution of our GNN-based reasoning module (Module 2), we conducted a targeted ablation study. Instead of comparing ARGUS to the weaker T5-FT (no structure) baseline, we compare it against the much stronger T5-LGP (Linearized Graph-Prompt) baseline. This comparison isolates the key research question: is it sufficient to just provide the symbolic graph as a text prompt, or does explicitly reasoning over the graph’s topology via a GNN yield superior results?

The results, shown in

Table 5, demonstrate a clear and significant advantage for the GNN-reasoning approach.

We analyzed the comparison using Wilcoxon signed-rank tests and the Cliff’s delta effect size. The full ARGUS system, leveraging the GNN’s diagnostic embedding, produced feedback that was rated as significantly more effective than providing the same structure as a prompt. The largest and most important difference was in

Accuracy (

), supporting our hypothesis that the GNN’s explicit reasoning is a more reliable method for diagnosing flaws than an LLM attempting to interpret a linearized graph-as-text. We also observed medium, positive effects on Specificity (

), Actionability (

), and overall Helpfulness (

).

This finding is central to our paper’s contribution. The T5-LGP model’s struggle (relative to ARGUS) suggests that while LLMs are good at incorporating textual information from a prompt, they are not optimized for performing the multi-hop, topological reasoning (e.g., “find all nodes of type ‘Claim’ with an in-degree of zero”) that a GNN is explicitly designed for. The GNN module acts as a specialized “reasoning engine” that performs this symbolic diagnosis and feeds a compact, targeted “flaw embedding” to the generator. This proves to be a more effective and reliable architecture than asking the generator to simultaneously parse a linearized graph and generate feedback.

Taken together, these ablation results reinforce our central claim: explicitly modeling graph structure with a dedicated reasoning module is not merely an implementation detail, but a key design choice that materially improves the pedagogical usefulness of the feedback.

Robustness of GNN Components

We investigated how variations in the GNN architecture and its inputs affect the final feedback quality, with overall helpfulness serving as the primary metric for comparison. As summarized in

Table 6, our system demonstrates high robustness across all tested variations. The detailed results for all four quality metrics are available in

Table A3.

For the graph readout function, which aggregates node embeddings into a single graph representation, we compared our standard ‘Mean Pooling’ with ‘Sum Pooling’ and ‘Attention Pooling’. While mean pooling performed strongest, the differences were minor, with helpfulness scores varying by less than 2.5%. This suggests that the rich information captured in the node embeddings is effectively aggregated by even simple pooling methods.

Similarly, we tested the sensitivity to the flaw set by removing the most complex and least frequent flaw, ‘Circular Reasoning’, from the training and detection process. The resulting feedback quality remained almost identical, indicating that the system’s performance is not overly reliant on any single flaw type and is effective at identifying more common issues like unsupported claims.

Finally, we replaced the ‘all-mpnet-base-v2’ sentence-transformer, used for node initialization, with another high-performing model, ‘e5-base-v2’. Again, the impact on the final helpfulness score was minimal. This demonstrates that the ARGUS framework is robust to the choice of the underlying sentence encoder, provided that a sufficiently powerful model is used to capture the semantics of the argumentative components. Overall, these findings confirm the stability and robust design of our GNN-guided feedback generation pipeline.

5.4. LLM-as-a-Judge Analysis

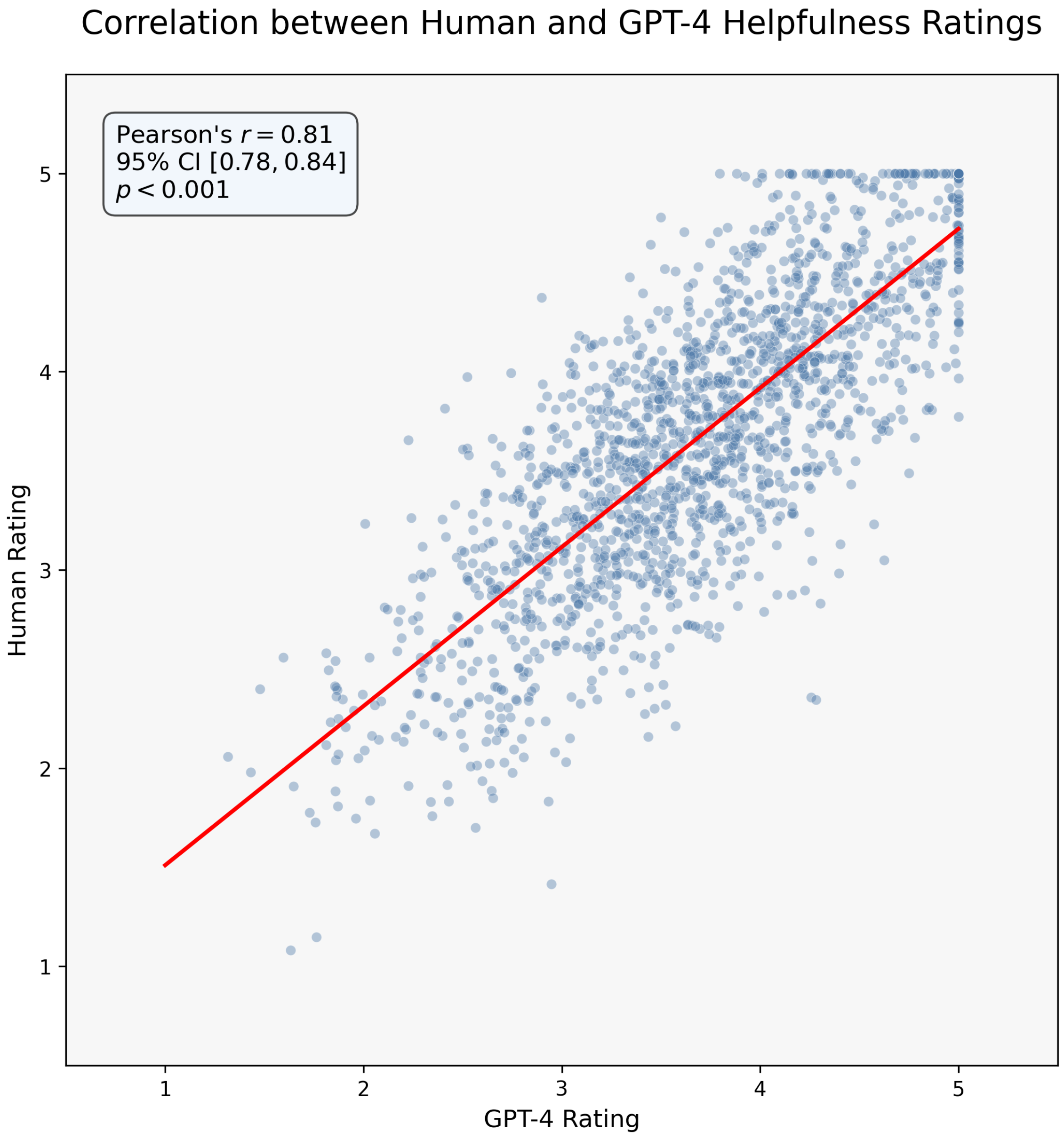

Recognizing the cost and scalability limitations of human evaluation, we explored the viability of using GPT-4 as an automated judge. The scatter plot in

Figure 6 shows a very strong and statistically significant Pearson correlation (

, 95% CI [0.78, 0.84],

) between GPT-4’s ratings and our four human experts’ mean ratings for overall helpfulness. This analysis was conducted on the full set of 1704 generated feedback instances (213 essays × 8 models). Together, these findings indicate that a carefully prompted LLM can approximate expert judgments well enough to support rapid prototyping and model comparison, even if it does not fully replace human evaluation. This result is encouraging, suggesting that for rapid, iterative development cycles, a well-prompted LLM can serve as a reliable and cost-effective proxy for human judgment.

To further investigate the validity of the LLM-as-a-Judge approach and address potential concerns of “circular validation”—i.e., that the LLM judge might simply prefer any LLM-generated style—we conducted an additional counterfactual preference test. We randomly selected 20 essays from our evaluation set. For each essay, we presented GPT-4 with two feedback options in a blind, randomized order: the feedback from our full ARGUS (GNN-guided) system and the feedback from the T5-FT (no GNN) baseline. We then asked GPT-4 to choose which feedback was more helpful. The results showed that GPT-4 overwhelmingly preferred the ARGUS feedback in 85% (17 out of 20) of the cases. This strongly suggests that the LLM judge is not simply rewarding a generic LLM “style,” but is capable of distinguishing and rewarding the higher quality (i.e., specificity, accuracy, and actionability) brought by the GNN’s structural guidance.

However, the deviation from a perfect correlation is also instructive. A qualitative review of outlier cases, where human and LLM scores diverged significantly, revealed systematic differences. The LLM judge was highly adept at pattern-matching against the rubric’s explicit criteria (e.g., rewarding feedback that directly quoted the student’s text). In contrast, human judges were better at appreciating pedagogical nuance, such as the motivational tone of the feedback or the creativity of a suggested revision. This highlights a crucial takeaway: while LLMs can automate the evaluation of objective quality dimensions, human oversight remains indispensable for assessing the holistic and student-centered aspects of educational feedback.

5.5. Qualitative Analysis

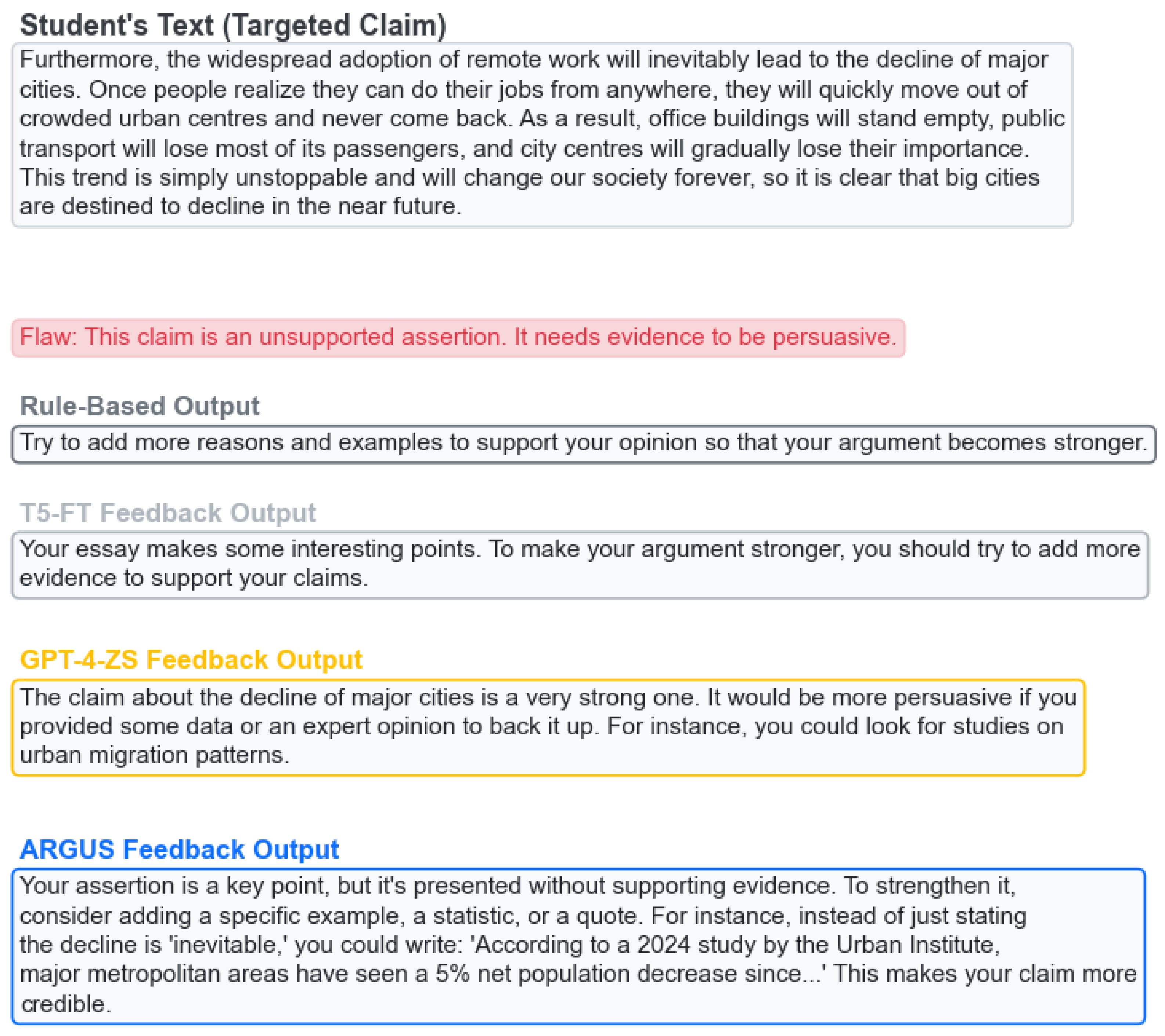

To complement our quantitative results,

Figure 7 provides a concrete example of the different types of feedback produced by each model for the same unsupported claim. This example serves as a practical illustration of the aggregate scores reported in

Table 4. The Rule-Based baseline produces a very short and generic comment (e.g., “Add more reasons to support your idea.”), reflecting its reliance on simple keyword heuristics rather than a structural understanding of the argument. The T5-FT output is generic, while GPT-4 provides good, actionable advice. The ARGUS feedback, however, stands out for its diagnostic structure. It systematically localizes the issue, quotes the problematic text, provides a clear diagnosis of the structural flaw (“presented without supporting evidence”), and then offers a menu of concrete strategies for revision. This structured, multi-part feedback is a direct output of the GNN-guided generation process and exemplifies the kind of specific, pedagogically-scaffolded guidance our system is designed to provide.

5.6. Analysis of Flaw-Specific Guidance

A central claim of our work is that the GNN provides *targeted* guidance, steering the generator to address specific issues rather than producing generic advice. To test this hypothesis, we conducted an experiment to measure the semantic alignment between the flaw type used to condition the generator and the content of the resulting feedback. For this analysis, we used a feedback-topic classifier based on a fine-tuned DistilBERT model. The classifier was trained on a manually labeled set of 500 feedback examples generated by our models and achieved a five-class accuracy of 92% on a held-out test set. The confusion matrices in

Table 7 and

Table 8 show the results.

The performance of ARGUS, detailed in

Table 7, confirms that the flaw embedding acts as an effective control vector. The model demonstrates a strong ability to generate on-topic feedback, with diagonal alignment scores as high as 80.9% for ‘Unsupported Claim’. This provides clear evidence of a causal link between the GNN’s symbolic diagnosis and the final semantic output. Importantly, the system is not infallible. As anticipated, it found it most challenging to generate specific feedback for the more abstract ’Circular Reasoning’ flaw, achieving a 69.8% on-topic rate and consequently reverting to generic advice more frequently in this condition. The off-diagonal entries also reveal logical, low-level patterns of confusion; for example, an ‘Unsupported Claim’ might occasionally elicit feedback classified as addressing an ‘Under-supported Thesis’ (5.1%), as these concepts are pedagogically related. This level of imperfection and nuanced performance is expected in a real-world system and highlights areas for future refinement.

In stark contrast, the unguided T5-FT model, shown in

Table 8, exhibits a clear lack of focus. While it produces on-topic feedback more often than random chance, indicating some learned correlations, it defaults to ’Generic Advice’ in the majority of cases (between 68.1% and 72.3%). This suggests that without an explicit structural map of the argument, the model struggles to reliably diagnose specific logical failures from raw text alone. Its on-topic performance is inconsistent, ranging from a modest 19.6% for ‘Irrelevant Premise’ down to 13.2% for the more difficult ‘Circular Reasoning’ flaw. This comparison provides compelling quantitative evidence for our core thesis: the GNN’s symbolic reasoning is not just a helpful addition, but a necessary component to ensure that the generated feedback is consistently precise, diagnostic, and pedagogically targeted.

To further ground these quantitative findings,

Appendix H presents a representative failure case in which a subtle circular reasoning pattern leads ARGUS to revert to relatively vague, partially generic feedback. This example makes the limitation noted above more concrete and highlights that, for some abstract flaws, the current system still under-specifies the exact nature of the reasoning problem.

6. Discussion and Future Work

Our work presents ARGUS as a blueprint for intelligent educational systems that function as sophisticated, automated formative assessment tools integrated into the writing process. This design provides pedagogical scaffolding aligned with Vygotsky’s theory of the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) [

35]. The GNN acts as an expert diagnostician (identifying where help is needed), and the guided LLM provides the targeted scaffold (providing how to help). This human–AI collaborative model, supported by recent work [

36,

37], positions ARGUS as a powerful assistive tool to augment, not automate, the instructor’s role.

This pedagogical grounding is realized through the core success of ARGUS: its principle of graph-grounded generation. By forcing the LLM generator to condition its output on a symbolic representation of a structural flaw—identified and localized by a GNN—we effectively mitigate the tendency of standalone LLMs to produce vague, ungrounded advice. This represents a valuable methodological shift from merely emulating human feedback to explicitly modeling the diagnostic reasoning process that underlies it. Furthermore, this approach offers a degree of interpretability often missing in end-to-end systems. We can trace a piece of feedback directly back to a specific topological pattern in the argument graph (e.g., an unsupported claim is a node with an in-degree of zero), addressing the “black box” problem that has historically hindered educator trust in AWE systems.

Our structural design choices were also guided by pedagogical considerations. While argumentation theory recognizes a rich set of relation types (e.g., rebuttals, undercutters, concessions),

our target users are L2 novice writers for whom mastering the foundational ‘Support’ configuration is the primary learning objective.

In our corpus analysis of the augmented AAE-v2 essays, over 95% of diagnostically relevant structural issues could be expressed in terms of missing or misdirected supporting and attacking links. Introducing a larger inventory of fine-grained relations would substantially increase the complexity of the annotation scheme and the cognitive load imposed on learners, without a commensurate gain in formative value.

By modeling only ‘supports’ and ‘attacks’, ARGUS focuses instructional attention on the core reasoning moves that novice writers most frequently struggle with, while keeping the feedback taxonomy compact and interpretable. Consequently, our current representation is less expressive than full-fledged argumentation frameworks: it cannot capture all nuances of rebuttals or undercutters, may miss certain complex argumentative patterns, and is best suited to essay genres where basic support/attack relations dominate.

Similarly, the hand-crafted threshold used in the ‘Under-supported Thesis’ definition reflects common expectations in L2 academic writing rubrics, where at least two independent lines of support for a central claim are typically required in short essays. Rather than being an arbitrary heuristic, this choice encodes an explicit, instructor-aligned standard that can be inspected, discussed, and, if necessary, adapted. One advantage of our neuro-symbolic design is that such thresholds are exposed as transparent parameters of the graph-based flaw definitions and do not have to be “rediscovered” as opaque weights inside a neural model. In future deployments, k can be tuned to match course-specific requirements (e.g., for longer or more advanced essays), allowing instructors to calibrate ARGUS to their local curriculum without retraining the entire system.

The implications of this semantic-to-symbolic-to-semantic blueprint could extend to other structured domains (e.g., code, mathematical proofs) [

38]. However, we acknowledge several limitations. The pipeline’s efficacy is contingent on the parser. As highlighted in our error analysis, parser errors can propagate [

39], though our robustness analysis showed a high degree of resilience. Future work could explore joint training to mitigate this. First, while we have significantly expanded the flaw taxonomy from four structural patterns to seven hybrid flaws (including the semantic-level ‘Vague Evidence’), this taxonomy could be further enriched. For example, the current ‘Vague Evidence’ detector is a first step, and future work could develop more nuanced classifiers to detect other content-level weaknesses, such as ‘weak warrants’ or ‘logical fallacies’. Second, our reliance on the AAE-v2 dataset (L2 learners) limits generalizability. While a preliminary zero-shot test on scientific abstracts showed partial transferability, validating the system on diverse genres and native-speaker data is a crucial next step.

Third, we acknowledge that the sample size for our human evaluation is relatively modest. While our LLM-as-a-Judge analysis (r = 0.81) provides additional confidence, a larger-scale human study is needed.

Furthermore, while our 3-stage pipeline is more computationally intensive than a single LLM query, we view this as a necessary trade-off for accuracy and interpretability. Our latency analysis confirms the system is practical (~1.53 s per essay), as the GNN reasoning step is exceptionally fast (0.06 s).

Fourth, although constructing 220 manually labeled argument graphs required a non-trivial one-time annotation effort, we argue that this cost is sustainable for new curricula and genres. Because the flaw taxonomy and graph schema are reusable across courses that share similar argumentative rubrics, new deployments do not require re-annotating hundreds of essays from scratch. In practice, we expect that adapting the R-GCN flaw detector to a new course would require carefully annotating on the order of 50–80 essays, with additional unlabeled data incorporated via weak supervision or self-training. Developing such semi-supervised adaptation strategies is an important direction for future work.

Finally, the ultimate measure of an educational system’s success is its impact on student learning. While a longitudinal study is necessary, we conducted two preliminary studies to assess pedagogical feasibility. First, a ‘revision feasibility’ proxy study found that experts preferred ARGUS’s revision path over GPT-4-ZS in 66% of cases (vs. 18%). Furthermore, a small-scale (N = 20 students, N = 3 instructors) follow-up usability study confirmed the feedback’s pedagogical value: students rated its comprehensibility (M = 4.4/5) and actionability (M = 4.2/5) as high, while instructors affirmed its diagnostic accuracy and high potential for classroom adoption (M = 4.5/5). These findings suggest our feedback can translate into effective revision, a hypothesis we will test in future classroom-based RCTs. This points toward integrating ARGUS into Learning Management Systems (LMS) to provide instructors with cohort-level analytics and support data-driven teaching.

7. Ethics Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with ethical guidelines. The primary dataset used for training and evaluation, the Argument Annotated Essays (AAE-v2) corpus, is a publicly available and fully anonymized resource.

In addition, we collected an institutional extension set of 150 L2 persuasive essays, which were fully anonymized prior to annotation and used solely for model training and evaluation.

For the human evaluation of the generated feedback, we recruited four PhD candidates in Applied Linguistics. All participants were provided with a detailed description of the research goals and the rating task. They provided informed consent prior to their participation and were informed of their right to withdraw at any time. The participants received compensation for their time and expert contributions.

8. Conclusions

In this paper, we have designed, implemented, and evaluated ARGUS, a novel neuro-symbolic system for providing actionable feedback on L2 argumentative writing. By systematically integrating an LLM-based argument parser, an R-GCN for structural flaw detection, and a GNN-conditioned feedback generator, the ARGUS system creates a virtuous cycle where semantic understanding informs symbolic reasoning, which in turn grounds semantic generation. Our experiments demonstrate that this integrated system architecture allows ARGUS to generate feedback that is significantly more specific, actionable, and helpful than strong LLM baselines. This work contributes to the field of AI and digital systems engineering by presenting a robust methodology for creating intelligent teaching systems. It represents a promising step towards developing AI-powered platforms that can provide the kind of deep, structural guidance needed to foster critical thinking in argumentative writing contexts and support meaningful education reform. In future work, we aim to extend this neuro-symbolic template beyond L2 persuasive essays, adapting the flaw taxonomy and graph schema to genres such as scientific writing and policy briefs, as well as to native-speaker corpora. We are also interested in reducing the supervision burden by exploring semi-supervised and transfer-learning strategies that reuse the existing structural detectors across related curricula. Finally, we plan to conduct larger-scale, classroom-based studies that integrate ARGUS into learning management systems and measure its longitudinal impact on students’ revision behavior and argumentative competence.