Abstract

Sustainable development, which integrates economic progress with environmental stewardship to serve societal needs, seeks a balanced approach to resource utilization and intergenerational equity. Implementing carbon policies to limit emissions in production is an effective measure that also puts pressure on the supply chain’s profitability. Meanwhile, the emergence of the price reference effect affects consumers’ behavior and the decisions of supply chain members. This study constructs a dual-channel supply chain model under three carbon policy scenarios within a manufacturer-led Stackelberg game framework. The model is solved analytically to examine equilibrium outcomes and investigate the influence of channel competition, the price reference effect, and carbon policies on profitability and carbon emissions across different scenarios. The results are as follows. (1) As consumers’ online channel preference increases, manufacturers’ profits turn from falling to rising, especially under a lower carbon tax (higher carbon quota), with profit growing earlier. (2) A stronger price reference effect encourages higher emission reduction efforts, selling prices, and profits in smaller markets. However, this effect can reduce prices and profits due to increased competition and pricing pressure in larger markets. (3) The influence of carbon tax and emission quota on emission reduction and price depends on the initial carbon emission of the product, and their interaction has different impacts on total profits at different initial emission levels. (4) Within the mixed policy, the supply chain can obtain better economic and environmental benefits at a specific range of basic market demand. This study provides valuable references for formulating tactics to cope with low-carbon demand and price reference effects, as well as for developing effective environmental protection policies.

1. Introduction

The international community has begun to act in response to global climate change. The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), adopted in 1992, advocates maintaining the concentration of atmospheric greenhouse gases at a level that “prevents dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate System”. Increased carbon dioxide levels lead to a warmer climate, ultimately causing various environmental problems [1]. This was followed by global climate negotiations, such as the Paris Agreement and the Kyoto Protocol, aimed at limiting carbon emissions and mitigating global warming [2,3].

Implementing environmental policies is essential in addressing climate change, environmental conservation, and sustainable progress promotion [4]. Carbon tax and cap-and-trade policies, which aim to reduce carbon emissions, have become the most widely used mechanisms for limiting emissions [5,6]. It has been shown that the cap-and-trade mechanism has achieved remarkable effects in the European Union and other regions, effectively reducing carbon emissions [7], while the implementation of carbon tax policy in Sweden and other countries has also proved its effectiveness in reducing emissions [8]. However, single policy instruments possess inherent limitations. While carbon taxes directly increase emission costs for enterprises, their effect on emission reduction is limited and may impose additional burdens on society; conversely, cap-and-trade systems are constrained by inadequate market mechanisms and limited coverage, making it difficult to comprehensively incentivize all emitting entities to participate in reduction efforts. Therefore, overcoming the shortcomings of single policies and establishing a more efficient, flexible, and low-cost emission-reduction mechanism has become a key issue in policy design and research [9]. In this context, mixed carbon policies (combining carbon tax with carbon trading) have gradually attracted attention. In recent years, practices in countries such as Sweden and Denmark have demonstrated that mixed strategies can achieve complementary advantages, as the synergy between price-based and quantity-based mechanisms can both stabilize emission-reduction expectations and enhance policy flexibility, thus exhibiting superior cost-effectiveness in reducing emissions from high-emission sectors [9].

Enterprises prioritize profits and may hesitate to reduce emissions due to the required investment in manpower, resources, and funds [10]. Carbon policies, however, incentivize eco-friendly practices, fostering sustainable supply chains and economic/environmental benefits. Nations like Sweden and Denmark have implemented mixed policies in high-emission sectors, combining carbon taxes and trading regulations [9]. Analyzing the impacts of these policies across various enterprises can help develop effective emission-reduction strategies.

Additionally, the price reference effect arises when consumers perceive a gain or loss due to discrepancies between a product’s market price and their reference price, derived from historical prices [11]. This effect influences purchasing decisions by shaping perceptions of a product’s value based on price and quality, significantly impacting supply chain pricing and strategies [11,12]. By understanding this effect, enterprises can guide consumer decisions through strategies such as setting optimal prices and improving low-carbon performance.

Exploring how supply chain firms can address the price reference effect under carbon-emission policies to optimize production and pricing decisions is crucial, enabling members to achieve greater economic benefits while reducing production emissions. Based on the background above, this study aims to explore the following topics:

- The optimal decisions include emission reduction levels, wholesale price, online direct selling price, and offline retail price, along with supply chain profits under three policy scenarios;

- The impact of channel preferences, price reference effects, and carbon parameters on optimal outcomes;

- Comparing supply chains’ economic and environmental benefits under different policy scenarios.

This study develops a supply chain model that addresses emissions reduction and pricing across three policy scenarios, accounting for price reference effects and channel competition. It analyzes how these factors and carbon parameters influence optimal outcomes and explores mixed policy strategies to achieve economic and environmental benefits. The main innovations of this study are summarized below.

On the one hand, the existing studies of the dual-channel supply chain [13,14] have mostly focused on production operation efficiency and pricing strategies without incorporating carbon-emission policies; the studies of the price reference effect [11,15,16] have been limited to consumer choices and the dynamics of reference prices, and have lacked exploration of consumers’ low-carbon preferences or policy constraints. While the related studies of carbon-emission policies [17,18] quantified the effects of carbon-emission policies, they ignored the interaction between consumer behavior and channel structure. This study makes a breakthrough by combining carbon tax and cap-and-trade policies with price reference effects and channel preference into a unified framework, revealing a multi-factorial coupling mechanism; adjusting the parameters of carbon policy shifts the inflection point in the relationship between channel preference and the manufacturer’s profit. Such a synergy among the “policy–behavior–channel” has not been systematically modeled in existing research. This study provides a new paradigm for cross-dimensional decisions in green supply chains.

On the other hand, there is a lack of systematic exploration of the role of mixed policies in supply chains among existing studies. While some studies [5,19,20] analyzed the independent impacts of carbon tax or cap-and-trade policies on supply chains, and Xu et al. [17] compared the effects of a single policy; both failed to thoroughly investigate the synergies between the two mechanisms, and have not examined the potential economic and environmental trade-offs of mixed policies. This study constructs a decision model within the context of the mixed policy and reveals its dual mechanism of “constraints and incentives”; the carbon tax constrains emissions through fixed costs (high-emission enterprises need to bear a higher tax burden) and cap-and-trade incentivizes emission reductions through the carbon market (low-carbon enterprises obtain revenues from the sale of additional quotas). Meanwhile, the study finds significant situational dependence in mixed policies balancing economic and environmental benefits; the specific market size affects the allocation of carbon quotas. It provides a micro-basis for governments to design regional, phased carbon policies (prioritizing mixed policies in high-demand regions) and to promote the innovation of policy precision and sustainable business practices.

The remainder of this study is organized as follows. Section 2 offers an overview of related research. Section 3 introduces the problem, assumptions, and notations. Section 4 and Section 5 develop a dual-channel supply chain model for three scenarios and analyze it. Section 6 employs numerical analysis to validate the results. Section 7 summarizes the findings, managerial insights, and limitations.

2. Literature Review

The literature review for this study was conducted using a systematic approach: “broad retrieval, precise screening, and focused analysis”. Firstly, a preliminary literature pool was established through combinatorial keyword searches guided by research questions. Subsequently, the identified sources were critically evaluated for their relevance to three key themes, i.e., dual-channel supply chains, the price reference effect, and carbon-emission policy. The review was ultimately refined by concentrating on seminal, high-impact, and cutting-edge publications to identify research gaps and establish a theoretical foundation for this study.

2.1. Dual-Channel Supply Chain

Many studies have recently examined dual-channel supply chains [13,21,22,23]. Multi-channel competition has received increasing attention. Price competition between retailers and manufacturers is inevitable, as identical products are priced differently across channels due to varying customer perceptions [24]. Giri et al. [25] evaluated pricing and recycling strategies across five decision-making scenarios, offering guidance for dual-channel supply chains to optimize pricing, product recycling, and overall benefits. Xu et al. [20] studied dual-channel green decisions under carbon policy, designing contracts for Pareto improvements, boosting environmental awareness, and profits. Cao et al. [26] explored the coordination strategies of online-offline supply chains by considering horizontal inventory transshipment pricing policy and corporate environmental responsibility. Xu et al. [27] examined trade credit financing for retailers in a dual-channel supply chain with capital constraints, and explored the impacts of free-riding behavior and consumer switching behavior on decisions, as well as the role of coordination contracts. Yang et al. [28] developed a dual-channel BOPS (buy online and pick up in store) supply chain model considering product return risks, analyzing how service cost coefficient and offline consumer loyalty affect optimal decisions and profits under manufacturer- or retailer-managed BOPS channels. Xu et al. [29] analyzed a dual-channel network with a well-funded online supplier and a capital-limited offline retailer, addressing capital constraints and pricing. They proposed a coordination mechanism using real data to provide practical supply chain optimization recommendations. Pal et al. [23] developed a dual-channel model for green innovation, using interval values to resolve conflicts and propose optimal strategies under different scenarios, enhancing traditional supply chain management. Hamzaoui et al. [14] simultaneously optimized manufacturing, storage costs, distribution strategies, and pricing for sales and leasing products, to a limited extent, to advise managers overseeing the pricing, production, and distribution decisions.

Previous studies [14,30,31] have focused on the operational optimization and low-carbon management of dual-channel supply chains, with an emphasis on pricing strategies, channel coordination, and emission-reduction mechanisms. The studies adopted contract coordination [27,32], and differentiated pricing strategies to maximize economic benefits while achieving sustainable development. However, existing research rarely explores comprehensive strategies to address complex challenges such as channel conflict, market competition, and dynamic market scale. More importantly, few studies have integrated online channel preferences with carbon policy constraints to examine the synergistic effects of these factors on supply chain performance. Therefore, by revealing the interaction between channel preferences and carbon policies, this study provides a new theoretical perspective for the management of dual-channel supply chains.

2.2. Price Reference Effect

Price reference effect was considered to explore the correlation among reference price, consumer behavior, and supply chain strategies. Xu and Liu [33] studied three recycling modes and found that higher reference price coefficients reduce manufacturer and retailer profits, and scenarios without reference price effects are generally more beneficial. Lin [34] studied price promotions based on the reference price effect, showing that they benefit manufacturers, retailers, and consumers, and highlighted scenarios in which retailers are keen to offer such promotions. Zhang and Chiang [15] examined how pricing decisions are made under reference price effects, providing relevant insights for marketers of durable products. Prakash and Spann [35] investigated the impact of dynamic pricing on the internal reference price effect. An experimental study found that customers react strongly to price inflation but not to price falls. Yan et al. [36] introduced reference prices into the product line design. They examined the influence of reference prices on optimal quality and price decisions for a given quantity of products. The results show that the product line’s optimal quality range narrows as the price comparison grows significantly. Wang et al. [16] studied optimal pricing across sales cycles, accounting for demand uncertainty and reference prices. Their findings help sellers navigate market volatility, improve sales efficiency, and refine pricing strategies. Huang et al. [37] constructed a sustainable supply chain using psychological accounting theory, analyzing government subsidies through reference prices.

The price reference effect has a crucial impact on consumer behavior and supply chain pricing strategies. Much research [11,35] showed that consumer reference price significantly affects purchase decisions and profit sharing. Chen et al. [38] further developed the algorithm to optimize dynamic pricing and verified the moderating role of the reference effect in demand response. However, most existing studies focus on single-channel or traditional market environments, paying insufficient attention to the complex interaction mechanisms in dual-channel networks (online-offline synergies) and to low-carbon activities (pricing changes under carbon policies). By integrating channel competition, low-carbon constraints, and market heterogeneity, this study explores the mechanism of the price reference effect in a multi-dimensional context, aiming to address unaddressed areas.

2.3. Carbon-Emission Policy

Studies on carbon-emission policies highlight the roles of carbon taxes and cap-and-trade in economic development, proposing mixed policies to encourage emission reductions. Entezaminia et al. [39] introduced a cooperative policy for production and trading under cap-and-trade, aiding managers in timing carbon permit trades and adjusting productivity to cut costs and emissions. Li et al. [40] designed multiple carbon policies by combining economic order quantity and economic production quantity models. It indicated that carbon prices and carbon taxes have a non-linear complementary relationship. Lyu et al. [19] examined optimal outcomes under various policies, impacts of carbon parameters, and preferences for recycling. They recommended tailored policies for manufacturers based on recycling behavior. Yang et al. [41] analyzed emission-reduction measures, online channels, and cap-and-trade regulation, and the optimal management decisions for supply chain members within the cap-and-trade regulation. Zhang et al. [42] developed a closed-loop model of electric vehicle battery power under the cap-and-trade constraint. It suggested that manufacturers choose recycling models and invest in carbon reduction. Govindan et al. [43] developed a bi-objective linear model incorporating a carbon tax to reduce carbon footprint. It helped companies to consider environmental factors better when operating closed-loop networks. Harijani et al. [44] noticed budget-constrained economic and environmental problems and developed a multi-period model to minimize the supply chain’s carbon tax and total cost. Xu et al. [17] found that carbon trading promotes economic growth more than a carbon tax but is less effective at reducing emissions. Chen et al. [45] analyzed carbon-trading prices and privatization, suggesting the need for government intervention. Wang et al. [46] explored the effects of two carbon quota allocation methods—grandfathering and benchmarking—on capital-constrained supply chain decisions under the carbon trading mechanism. They investigated the impact of carbon reduction strategies on supply chain performance. In contrast to previous studies that focused on a single carbon policy, Zhu et al. [47] integrated consumer awareness, green technology, and mixed policies, reflecting real-world low-carbon supply chain dynamics.

Studies have widely investigated the effects of carbon tax and cap-and-trade policies on manufacturer behavior, environmental awareness, social welfare, and supply chains. Several studies [5,19,42] showed that these policies, combined with consumer environmental awareness, can reduce emissions and enhance manufacturer competitiveness. In addition, certain research [9,47] explores mixed policies, analyzes policy interactions, examines price correlations, assesses recycling under different policies, and considers implementation scenarios. However, there is limited research on the application of mixed policies in supply chains and their impact on production and pricing decisions. This study further investigates the key parameter settings of mixed policies and their effects and reveals the advantages and applicable conditions of mixed policies by comparing the operational performance of supply chains under mixed policies and single policies, to support the organic design of carbon policies.

Table 1 clarifies the differences between this study and related literature.

Table 1.

Related literature of this study.

3. Research Methodology

This study employs game theory to construct and solve the analytical model. As a mathematical framework for analyzing strategic interactions among rational decision-makers, game theory is widely applied in supply chain management to model behavioral patterns of conflict or cooperation among participants. The Stackelberg game, a typical sequential game, is particularly useful for characterizing the prevalent “leader-follower” structure in supply chains. This hierarchical decision-making mechanism effectively captures power asymmetry and strategic interdependence among supply chain members.

In supply chain contexts, game theory serves as an analytical tool to examine how manufacturers, retailers, and other stakeholders formulate operational and strategic decisions—including pricing, production planning, and emission-reduction strategies—under varying policy regimes and market conditions. To illustrate this application, Zhao et al. [9] developed a mixed Stackelberg-Cournot framework to analyze duopoly competition in supply chains. Their model structure specifies that manufacturers are first movers in determining emission-reduction levels, followed by sequential decisions on wholesale and retail pricing. The equilibrium solutions were obtained through backward induction. Similarly, Huang et al. [37] established a Stackelberg game incorporating government intervention, with decision sequencing following government-manufacturer-retailer hierarchy. By employing backward induction, the study derived optimal solutions for product greenness, wholesale and retail prices under alternative power structures and governmental objectives. Collectively, these investigations validate the efficacy of Stackelberg games in modeling sequential and interdependent decision-making processes characteristic of complex supply chain systems.

4. Problem Description, Assumptions and Notations

This study develops a dual-channel, closed-loop model involving a manufacturer and a retailer. The manufacturer, as the leader in a Stackelberg game, produces low-carbon products for online and offline sales, setting emission-reduction targets, wholesale prices, and online prices, followed by the retailer setting offline prices. After the products are sold, the manufacturer recycles a specific rate of the used and expired products. Three carbon-emission policy scenarios are considered: a single carbon tax policy, a single cap-and-trade policy, and a mixed policy with a carbon tax and cap-and-trade.

In addition to studying the optimal decision on the emission reduction level, the online direct selling price, and the offline retail price, with the maximization of supply chain members’ profit as the optimization objective. It is also necessary to explore the impact of channel preference, price reference effect, and carbon-emission policies on the optimal solution, and to compare the economic and environmental benefits of mixed policies versus a single policy.

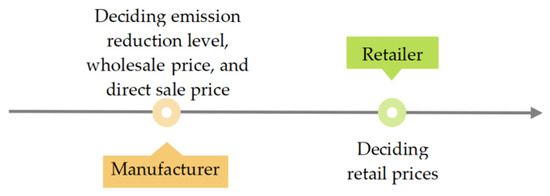

As Figure 1 illustrates, after the government promulgates a carbon-emission policy, the manufacturer, as the Stackelberg leader, sets emission-reduction, wholesale, and online prices, followed by the retailer setting the offline retail price.

Figure 1.

Decision sequence.

To examine the influence of channel competition and price reference effects on supply chain decisions, product demand is modeled as a linear function of the selling price, the emission-reduction level, and the reference price, with order quantities set to match product demand for each channel. Reference to previous studies [23,38,49], the demand functions are expressed as ; . Here, is expressed as the basis market demand, is consumers’ online channel preferences (), a higher indicates that consumers tend to use online channels. is the price elasticity coefficient (), and and indicate online direct selling price and offline retail price, respectively. is consumers’ low-carbon preference, indicating consumer environmental awareness. is expressed as consumers’ reference prices based on historical price information [12,50], is the price reference coefficient (), A higher means more sensitive to the difference between the reference price and the selling price [51]. and denote demand changes due to the price reference effect, where prices below/above consumer benchmarks create perceived gains/losses, accelerating/slowing demand [11,52].

To curb emissions in production, manufacturers invest in reduction technologies. As emission reduction levels rise, cutting emissions becomes harder, causing investment costs to increase significantly [53]. Present studies [19,20,48] show that emission-reduction costs follow a quadratic function of the emission reduction level: . Where is the cost coefficient of emission reduction (), assumed as a one-off expenditure [5], so is regarded as a larger value [30]. is the emission reduction level per unit of product.

The manufacturer develops recycling systems for used products, assuming a recycling rate of at a cost of per unit for products sold through both channels. is expressed as the cost coefficient of recycling (). According to related studies [54,55,56], the cost function of recycling is expressed as .

The manufacturer determines total carbon emissions by controlling product emission reduction levels and production-generated emissions [57]: . Where is the initial carbon emissions per unit of product, representing emissions before investment in emission reductions. Within a carbon tax policy, the manufacturer pays a fee per unit of for carbon emission, denoted as . Under the cap-and-trade policy, the manufacturer receives free carbon permits . If actual emissions exceed the quota, it buys permits at a price , denoted as ; if the emissions are below, it can sell the remaining quota for additional revenue, . Carbon quota settings influence carbon market supply and demand; strict limits reduce supply, raising prices, while lenient limits increase supply, lowering prices. Benjaafar et al. [58] showed that carbon trading price is a linear function of the carbon quota, i.e., , where is a constant, is the elasticity coefficient of carbon quota to carbon trading prices (). The costs/benefits arising from carbon policies in the three scenarios are as follows: a carbon tax policy only, ; a cap-and-trade policy only, ; mixed policies, .

All parameters in their models are shared information. Table 2 shows the notations of the study.

Table 2.

Notations.

5. Model Development and Analysis

This section develops three dual-channel models for varying policy scenarios. Model TA and Model CT apply only carbon tax and cap-and-trade policies, respectively. At the same time, Model M combines both, examining their interrelation with online channel preference, price reference effect, and optimal outcomes.

5.1. Single Tax Policy (Model TA)

The manufacturer pays a certain tax based on the actual emissions from production under a single carbon tax policy.

The profits of the manufacturer and retailer:

The first and second terms in Equation (1) are manufacturers’ revenues from sales and wholesaling, the third is emission-reduction cost, the fourth is recycling cost, and the last is carbon policy cost. Equation (2) is the retailer’s revenues from sales.

The total profit of the supply chain is the sum of the manufacturer and the retailer:

The optimal decision solutions in Model TA are shown as Table 3. The detailed derivation is in Appendix A.1.

Table 3.

The optimal solutions in Model TA.

5.2. Single Cap-and-Trade Policy (Model CT)

Model CT implements a cap-and-trade policy in which manufacturers receive a fixed carbon quota. Exceeding the quota requires purchasing permits; surplus quota can be traded for revenue.

The profits of the manufacturer and the retailer:

The last item in Equation (4) is the cost–benefit of cap-and-trade.

The total profit of the supply chain:

The optimal decision solutions in Model CT are shown as Table 4. The detailed derivation is in Appendix A.2.

Table 4.

The optimal solutions in Model CT.

5.3. Mixed Policy (Model M)

Model M explores a mixed carbon tax and cap-and-trade strategy, assuming the manufacturer pays the carbon tax and trades in the carbon market.

The profits of the manufacturer and the retailer:

The last item in Equation (7) is the cost–benefit of the mixed policy.

The total profit of the supply chain:

The optimal decision solutions for Models M (decentralized and centralized) are shown in Table 5. The detailed derivation sees Appendix A.3.

Table 5.

The optimal solutions in Model M.

5.4. Model Analysis

Based on the optimal outcome in Model M, the online channel preferences, price reference effect, and carbon taxes/quota were discussed in Propositions 1–4.

Proposition 1.

The correlation between online channel preferences and manufacturer’s profits:

- (1)

- When or , online channel preference is positively correlated with manufacturer’s profit at , and has a negative correlation at .

- (2)

- When or , online channel preference is positively correlated with manufacturer’s profit at , and has a negative correlation at . Where

- (3)

- At , basis market demand is negatively (positively) correlated with thresholds (); at , it has a positive (negative) relationship with thresholds ().

Proof.

See Appendix A.4. □

Under decentralization, consumer online preferences influence manufacturers’ and retailers’ decisions and profits. Higher online demand raises direct selling prices, increasing manufacturer revenue, but lowers offline demand, wholesale, and retail prices.

Manufacturers’ profits initially decrease and then increase as online channel preference grows. Proposition 1(1) and (2) show that with a low carbon tax or high quota (low carbon price), profits go from falling to rising at , whereas, with high carbon tax or relatively low carbon quota (high carbon price), profits only start to rise at . With lenient government control (low carbon tax or high quota), manufacturers can offset costs through efficiency and emissions improvements, with some impact on online profits. However, strict control (high taxes or low quotas) significantly raises emission costs, heavily affecting online profits and requiring stronger online preferences to recover profits.

Proposition 1(3) shows that thresholds and are affected by basic market demand . Low online preference narrows the profit-reducing scope of carbon tax/quota as market demand grows; high preference widens the profit-boosting scope. Market scale, linked to production and sales, affects emissions, underscoring the need for government consideration in policy formulation.

The above analysis reveals the interplay among consumer channel preferences, profits, and external environmental policies. This interplay can be conceptualized as the cost threshold effect of channel transformation, a U-shaped pattern in a manufacturer’s profits during the transition to online channels, characterized by an initial decline followed by a subsequent rise. The level of external environmental costs, such as carbon prices predominantly determines the duration of this transitional period. This structured principle indicates that a lenient policy environment can lower the threshold for corporate channel transformation, while stringent regulations can raise it. Therefore, this finding provides a theoretical basis for understanding corporate adaptive strategies in complex market environments and suggests that policymakers must comprehensively consider the incentives and constraints that policy tools impose on endogenous strategic adjustments when promoting industrial upgrading.

Proposition 2.

The relationship between the price reference effect and the optimal outcome:

- (1)

- When , the price reference coefficient is positively correlated with the emission reduction level; when , they are negatively correlated.

- (2)

- When , the price reference coefficient is positively correlated with selling price; when , they are negatively correlated.

- (3)

- When , the price reference coefficient is positively correlated with the total profit; when , they are negatively correlated. Where

- ,, and .

- (4)

- The reference price is positively correlated with the threshold , , and

Proof.

See Appendix A.5. □

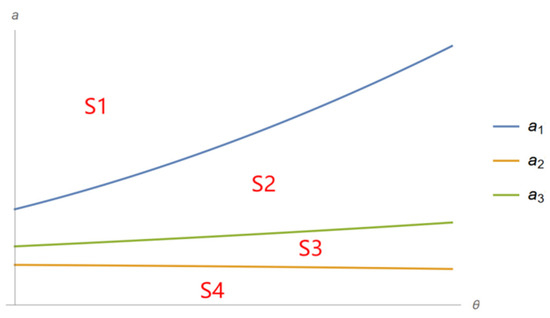

This study primarily examines the price reference effect using the reference price and the price reference coefficient. As , , , and , the rising reference price increases the optimal outcomes. Proposition 2 examines how the price reference coefficient affects optimal outcomes in Model M, with varying correlations under different market demands. Thresholds , and determine the impact of on emission reduction level, prices, and total profit. Figure 2 and Table 6 show the market demand split across four regions at three thresholds.

Figure 2.

Effect of price reference coefficient on basic market demand threshold.

Table 6.

Correlation between optimal outcomes and price reference coefficient.

In low-demand markets (Area S4), optimal outcomes improve as the price reference coefficient rises. Increased emission reduction attracts eco-conscious consumers, enabling higher selling prices to offset technology costs, boosting profits while supporting sustainability.

With moderate market demand, increasing the price reference coefficient shifts from Area S2 to S3, requiring higher emission reduction levels. Initially, supply chain profit declines then rises. A weak price reference effect complicates pricing, potentially reducing profits. A stronger effect increases consumer price sensitivity, easing purchase decisions and enabling supply chains to capture market share with appropriate pricing and relatively lower prices.

In moderate-to-high-demand markets, reduce selling prices as the price reference coefficient rises, since a stronger effect amplifies demand fluctuations. To counterbalance demand decline, lower prices to narrow the gap. Additionally, market expansion enables economies of scale, allowing enterprises to share cost savings with consumers, boosting competitiveness and sales.

Proposition 2(4) indicates that a higher reference price raises the primary market demand threshold, increasing the likelihood of positive impacts on optimal decisions and profits. High reference prices reflect consumer expectations for quality and low-carbon performance, increasing price sensitivity. This pressure forces enterprises to adopt additional measures to meet consumer demands and narrow the gap between selling and reference prices.

Based on the above analysis, this study reveals that the price reference effect exerts a dual influence on supply chain management, presenting both opportunities and challenges. The general patterns indicate that this effect requires dynamic coordination between pricing and emission-reduction strategies in response to demand fluctuations. It creates a strategic inflection point characterized by an initial profit decline followed by an increase, particularly in medium-demand markets, while simultaneously raising market entry barriers that compel continuous value innovation. These findings demonstrate that reference price serves not merely as a parameter for pricing decisions, but as a critical nexus connecting consumer cognition with supply chain strategy. This managerial logic can be extended to other market environments where quality perception and price comparison coexist.

Proposition 3.

When , carbon taxes (carbon quota) are positively (negatively) related to the emission reduction level; when , carbon taxes (carbon quotas) have a negative (positive) relationship. Where

Proof.

See Appendix A.6. □

Proposition 3 analyses the influence of carbon taxes and carbon quotas on the emission reduction level. When initial carbon emissions are below the threshold , they are relatively low. Increasing the carbon tax encourages enterprises to adopt more efficient technologies and to focus on reducing their carbon footprint rather than paying higher taxes, leading to a positive correlation between the carbon tax and emission reductions. However, since initial emissions are already low, a higher carbon quota may exceed actual emissions, reducing the incentive to reduce emissions and creating a negative correlation. Conversely, when initial emissions are high, even with advanced technologies, reducing emissions remains challenging, and enterprises may prioritize profit over emission reduction. In this case, the carbon tax is negatively correlated with emissions reductions, whereas the carbon quota is positively correlated.

Proposition 4.

When , carbon taxes (carbon quota) are positively (negatively) correlated with selling price; when carbon taxes (carbon quotas) are negatively (positively) correlated. Where

Proof.

See Appendix A.7. □

Proposition 4 examines the impact of carbon taxes and quotas on selling prices in Model M. When initial carbon emissions exceed the threshold , supply chain members may pass on the higher carbon tax burden to consumers by raising prices. Conversely, a higher carbon quota loosens emission restrictions, increases carbon permits, and encourages enterprises to lower prices to boost demand. For products with low initial emissions, carbon taxes have a minimal impact, and tighter carbon quotas incur lower additional costs.

The findings of Propositions 3 and 4 not only elucidate the mechanisms of carbon tax and carbon quota within the specific supply chain model but also distill universally applicable principles of carbon policy effects. On the one hand, this study reveals that the effect of carbon policy shows significant initial-state dependence, i.e., policy effectiveness varies with initial emissions, suggesting that policymaking should be tailored to the specific emission profiles of different entities. On the other hand, there exists an asymmetry in the pathways through which carbon tax and quota operate; carbon tax primarily influences emission reduction through technological incentives, whereas carbon quota affects pricing via market supply constraints. These findings indicate that in the design of mixed policy instruments, precise alignment with the emission characteristics of market entities is essential.

6. Comparative Analysis

This section compares total profits and emissions under a mixed policy with those under two single policies to highlight the advantages of the mixed approach.

6.1. Model M vs. Model TA

The comparison of the supply chain’s profits and emissions in Model M and Model TA is shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

Comparison of Model M and Model TA.

The expressions of threshold see Appendix A.8.

As shown in Table 7, in relatively smaller markets (), product demand and enterprise size tend to decrease, reducing the cost of implementing emission-reduction measures and making green technologies more feasible. Under a single carbon tax policy, firms face a heavier tax burden, especially in smaller markets with higher emission-reduction costs, which can strain finances. In contrast, the mixed policy, with higher carbon quotas, incentivizes emission-reduction investments, and promotes greener production and supply chain transitions. Governments often provide additional support to help smaller-market firms meet emission-reduction goals. The mixed policy thus offers a strong foundation and favorable environment for enterprise emission-reduction efforts.

As the basic market expands (), enterprises scale up production, increasing emissions and emission-reduction costs. Strict carbon policies may strain finances short-term, but manageable. Costs can be offset by innovation, efficiency, and economies of scale, lowering per-unit emission costs and enhancing competitiveness.

In terms of carbon emissions, loose carbon quotas in mixed policies may reduce enterprises’ incentives to reduce emissions, undermining carbon control. Stricter quotas are necessary to effectively limit supply chain emissions, potentially surpassing single-carbon tax policies in reductions. Essential for motivating enterprises and achieving emission goals.

Referring to Table 7, Corollary 1 examines the conditions under which Model M demonstrates superior benefits.

Corollary 1.

When , and , the economic and environment benefits in Model M are better than those in Model TA.

Proof.

See Appendix A.9. □

When the market size is high (), a lower government-set carbon quota () under a mixed policy leads to higher supply chain profits and lower carbon emissions, offering superior economic and environmental benefits compared to a single carbon tax policy.

Under a single carbon tax policy, higher emissions increase carbon tax costs, squeezing profit margins. While this may push enterprises to invest in emission-reduction technologies, the high costs and time required make it an inefficient incentive for effective emission reduction. In contrast, a mixed policy combines carbon taxes and quotas, balancing economic growth and environmental protection. Stricter carbon quotas under this policy improve emission-reduction efficiency, especially as economies of scale increase. The carbon trading mechanism further incentivizes energy-saving measures, allowing enterprises to sell excess quotas if their emissions are below the limit. This enhances economic efficiency while meeting environmental goals.

6.2. Model M vs. Model CT

The comparison of the supply chain’s profits and emissions in Model M and Model CT is shown in Table 8.

Table 8.

Comparison of Model M and Model CT.

The expressions of threshold see Appendix A.10.

As shown in Table 8, in smaller markets (), governments can adopt flexible carbon allowances, setting higher quotas alongside a carbon tax to incentivize emission reduction without significantly reducing supply chain profitability. Due to low competition and low emission-reduction costs, the mixed policy may yield higher profits than a single cap-and-trade policy, as the carbon tax encourages emission cuts. In contrast, higher quotas minimize the impact on profits.

In larger markets (), despite stricter carbon quotas increasing emission-reduction challenges, technological advancements and efficiency improvements can lower costs and boost supply chain profits. Thus, the mixed policy may still outperform a single cap-and-trade policy in profitability.

Regarding carbon emissions, stricter quotas directly limit emissions, while the carbon tax incentivizes reduction efforts, collectively lowering total emissions, as outlined above.

Based on Table 8, the conditions under which Model M has advantages are deducted from Corollary 2.

Corollary 2.

When , and , the economic and environmental benefits in Model M are better than those in Model CT.

Proof.

See Appendix A.11. □

The mixed policy is particularly effective in larger markets (), where tighter carbon quotas can boost supply chain profits and reduce emissions. The threshold guides governments in setting quotas; for markets above this size, generous quotas can incentivize emission reduction without overly burdening enterprises. The carbon tax complements quotas, further encouraging emission cuts.

In summary, within specific ranges, mixed policies can achieve a win-win for environmental protection and economic growth across different market conditions.

6.3. Discussion

The implementation of mixed policies requires coordinated efforts from governments, enterprises and consumers. Governments should lead the establishment of a regulated carbon trading market, clarifying trading rules and quota allocation schemes, while setting reasonable tax rates and dynamic adjustment mechanisms aligned with economic development and emission-reduction targets. Differentiated carbon tax and emission standards should be formulated according to sector-specific characteristics and enterprise scale, as well as establishing a comprehensive carbon emissions monitoring and assessment system. Meanwhile, measures such as fiscal subsidies and tax incentives should be employed to encourage enterprises to invest in low-carbon transformation.

Differentiated design is key to the effective implementation of mixed policies. Energy-intensive industries, characterized by high carbon-emission intensity and limited reduction potential, should be subject to higher tax rates to curb emissions. Large enterprises, which possess greater financial and technological capabilities, can afford higher tax burdens, while small and medium-sized enterprises need more flexible policies to ensure fairness. This differentiated approach, based on sector characteristics and enterprise scale, requires detailed emissions data and assessments of reduction potential. By scientifically determining the tax structure, a balance between emission reduction and economic efficiency can be achieved [59].

As a highly flexible policy mix, effective mixed policies can achieve more significant emission reductions at lower costs and with less economic loss [60]. As an early country to implement both a carbon tax and an Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS), the experience of the United Kingdom has provided a valuable reference for the European Union in implementing its ETS, particularly in the integration and coordination of the two policies. Upon joining the EU ETS, Northern European countries helped establish a consistent carbon price signal across the European Union, which has profoundly influenced the daily operations and strategic investment decisions of enterprises. However, significant fluctuations in carbon prices may affect the effectiveness of carbon taxes levied on non-ETS sectors. For instance, when ETS carbon prices are excessively low while carbon tax rates are excessively high, it may trigger a shift in carbon emissions from ETS-covered sectors to non-ETS sectors. Therefore, to ensure that carbon taxes and emissions trading policies work synergistically to establish a comprehensive, stable, and effective carbon price, it is essential to carefully design and maintain the relationship between the carbon tax and the ETS carbon price [61].

Since the carbon quota set by the government determines the supply-demand dynamics in the carbon market, the carbon trading price examined in this study is negatively correlated with the carbon quota [58]. From Corollaries 1 and 2, under specific conditions, mixed carbon policies can achieve dual economic and environmental advantages that surpass those of single-policy approaches. This superiority stems from their inherent synergistic mechanism; a stricter carbon quota sets a clear environmental baseline, while the flexibility of carbon taxes helps curb excessive emissions and balance corporate costs. The effective functioning of this mechanism relies on a stable and sufficiently large market, which ensures the efficient transmission of carbon price signals. From a theoretical perspective, the design of mixed policies addresses “market failures”. Rather than replacing market mechanisms, it enhances market self-regulation by providing stable carbon price signals, thereby guiding enterprises to make long-term strategic decisions aligned with emission reduction goals. Consequently, the theoretical optimum identified by this model serves as a robust reference for designing mixed policy instruments in the real world that effectively integrate government intervention with market forces.

7. Numerical Analysis

This section employs numerical simulation to further validate the propositions above. According to relevant factors and existing research [19,54,58], the following parameters are considered: ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; .

7.1. Effect of Online Channel Preferences on the Optimal Manufacturer’s Profits

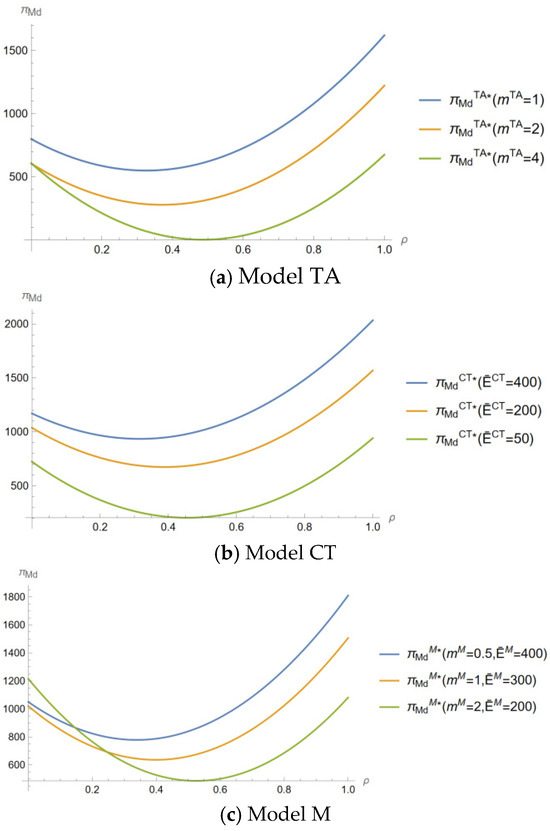

To observe the correlation between consumers’ online channel preferences and manufacturers’ profits for different carbon taxes and carbon quota, three situations are set up in each of the three models: ; ; and . Let , , and , exploring changes in optimal manufacturer profits as affected by online channel preferences at .

As in Figure 3, the manufacturer’s profit falls when online channel preference is low but rises as preference increases to a specific range. The profit inflection point varies with carbon tax and quota levels, occurring earlier under low tax/high quota. Lighter taxes or generous quotas allow higher profits even with lower online preference. Conversely, higher tax or tighter quota increase costs and pressure, reducing profits, but higher online preference can boost sales and offset these costs. This phenomenon reveals a dynamic interplay between policy and market forces, rooted in the trade-off between policy-induced costs and channel-related benefits. The profit inflection point serves as a critical juncture, marking strategic pivots in its online channel strategy from the investment phase to the returns phase. In this process, carbon policies act as a constraint that suppresses short-term profits yet simultaneously function as an external driver compelling accelerated transformation. Conversely, a lenient policy environment may diminish the urgency for such strategic adjustments. Consequently, decision-makers must cultivate strategic foresight that looks beyond short-term profit fluctuations, leveraging policy pressure as a catalyst to accurately identify and act upon these strategic inflection points.

Figure 3.

Effect of online channel preferences on manufacturer’s profit.

7.2. Effect of Price Reference Coefficient on the Optimal Outcomes

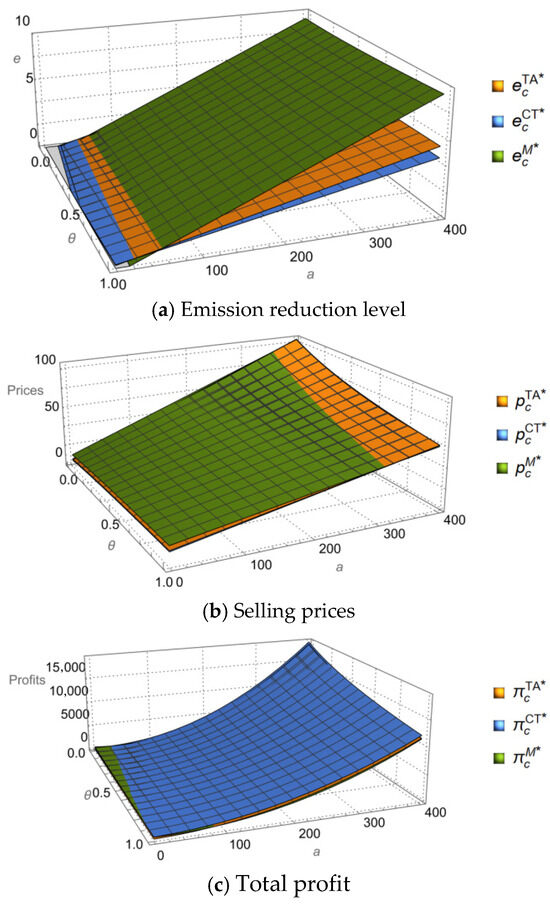

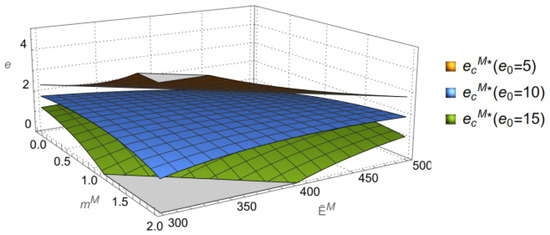

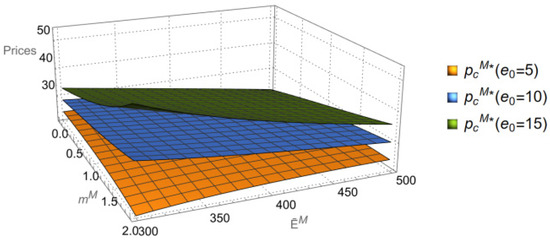

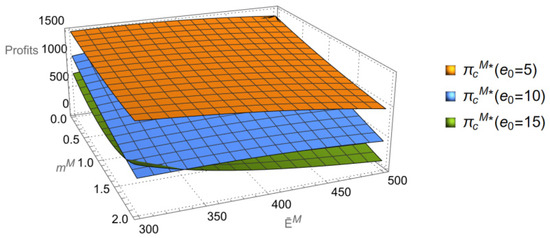

This subsection observes the effect of the price reference coefficients on the optimal outcome. As Proposition 2, the change in the optimal outcome affected by price reference coefficient shows different correlations at different market sizes. Setting , and , , , , , and , observing changes in optimal outcomes as affected by price reference coefficient at .

As shown in Figure 4a, when primary market demand is low, the emission reduction level slightly increases with the price reference coefficient. Higher price sensitivity reduces consumer demand, prompting firms to lower emissions and enhance product environmental friendliness. With high market demand, emission reduction levels remain stable despite price reference effects. Model M, combining carbon tax and cap-and-trade, achieves greater emission reductions compared to single-policy models.

Figure 4.

Effect of price reference coefficient on optimal outcomes.

In Figure 4b, with lower market demand, firms can more easily influence the market and raise selling prices. At higher demand, prices are higher, but increased consumer price sensitivity forces firms to lower prices, making products appear more reasonably priced and boosting sales.

In Figure 4c, higher selling prices in smaller markets lead to greater profits. However, at higher market demand, stronger price sensitivity reduces sales and profits as consumers resist high prices.

These findings collectively indicate that emission-reduction and pricing strategies constitute a dynamic response to the core constraint of price sensitivity, within the strategic latitude defined by market scale. They reveal the complex trade-offs firms face among environmental investments, market share, and short-term profitability. This complexity necessitates a departure from one-size-fits-all approaches, requiring decision-makers to dynamically recalibrate and optimize their operational priorities in response to evolving market conditions.

7.3. Effect of the Carbon Tax and Carbon Quota on the Optimal Outcomes

This subsection observes the influence of carbon tax and carbon quota on the optimal outcome. Propositions 3 and 4 show different correlations for different initial emissions per unit. There are three level, , and let , , , examining changes in supply chain decision at and as influenced by mixed policies.

As shown in Figure 5, at and , rising carbon taxes and tighter quotas incentivize firms to reduce emissions to avoid additional costs. The combined effect of carbon tax and cap-and-trade increases pressure, prompting more emission-reduction efforts. However, at , the optimal reduction level is lower, as firms may minimize costs by reducing investment, even dropping to zero. These results highlight the positive impact of carbon taxes and quotas on emission reduction in most cases.

Figure 5.

Effect of mixed carbon tax and quota on emission reduction level.

In Figure 6, at , firms face minimal cost pressure from rising carbon taxes and tighter quotas, maintaining stable selling prices. At and , increased carbon taxes and reduced quotas leading firms to pass the costs onto consumers through higher prices. It reflects the economic incentive of carbon policies for low-carbon products and the penalty for high-carbon products.

Figure 6.

Effect of mixed carbon tax and quota on sale price.

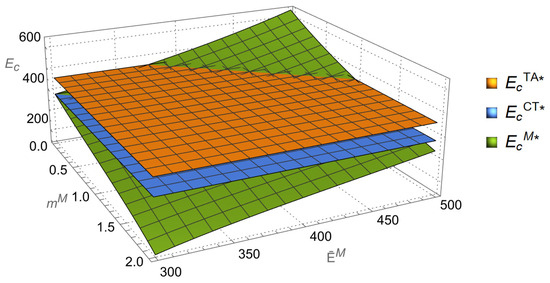

Figure 7 illustrates that at , firms profit from lower carbon taxes and accessible quotas, but rising taxes increase costs, impacting supply chain profits. Loose quotas ease permit access but also raise costs. At and , higher taxes and stricter quotas apply. Low taxes and relaxed quotas can boost profits, but rising taxes require balancing tax and quota costs, potentially reducing profitability. Profits stabilize at but decline more at .

Figure 7.

Effect of mixed carbon tax and quota on total profit.

These findings reveal a central thesis; the efficacy of carbon policy is not linear but is highly contingent upon the initial emission, which determines its response to regulatory pressure and ultimately entails complex trade-offs between environmental goals and economic viability. This series of trade-offs underscores the necessity for decision-makers to treat carbon footprint as a core strategic variable. They must adopt tiered strategies, ranging from green monetization and cost reduction to disruptive innovation, tailored to their specific emission profile, while also collaborating across their supply chains to navigate carbon constraints.

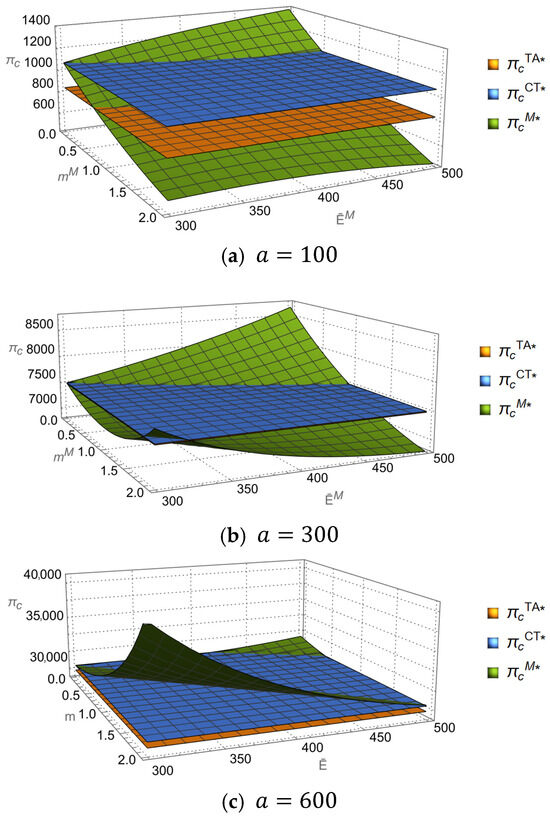

7.4. Comparison of Economic Benefits Under Different Policies

This subsection compares total supply chain profits in three scenarios. Setting three levels, , let , , , and , investigating the supply chain profits under three policies at and .

As shown in Figure 8a,b, at and , the total profit in Model M is often not significantly higher than in Model TA and Model CT. A single carbon tax has a minimal impact on profitability due to low tax payments, while a single cap-and-trade policy increases costs as firms buy more carbon permits, reducing profits. In most cases, Model M outperforms Model TA but falls short of Model CT. Additionally, in smaller markets, a higher carbon quota improves profits under the mixed policy.

Figure 8.

Total profit of supply chain under three models.

At in Figure 8c, Model M generally yields higher profits than Model TA and Model CT. Here, stricter carbon quotas enhance profitability under the mixed policy.

Thus, the economic benefits of a mixed policy are not static; rather, they exhibit a dynamic synergy with market scale and the stringency of the carbon quota. This reveals the fundamental trade-off between policy certainty and market flexibility. Enterprises need to deem policy adaptability as a core competitive strength and dynamically adjust their carbon strategies based on their respective market cycles. The strategic focus in smaller markets should be on cost control, while in larger markets, stringent quotas ought to be perceived as a strategic signal to courageously invest in emission-reduction technologies, with a view to constructing a sustainable cost-leading advantage.

7.5. Comparison of Environmental Benefits Under Different Policies

This subsection compares total carbon emissions in three scenarios. Let , , , , and , observing the total carbon emission under three policies at and .

Figure 9 shows that high carbon quotas and low taxes in Model M led to higher emissions than in Model TA and Model CT. The stricter taxes and quotas in Model M reduce emissions, with its environmental benefits arising from the synergistic effects of policy instruments. This result highlights the core trade-off in policy design, striking an optimal balance among policy stringency, environmental effectiveness, and economic cost. Enterprises should transcend the limitations of passive compliance by proactively internalizing the incentives of mixed policies as a competitive advantage and actively engage in policy dialog to co-shape an optimal framework that achieves synergistic environmental and economic development.

Figure 9.

Total emission of supply chain under three models.

8. Conclusions and Managerial Insights

8.1. Conclusions

This study considers the price reference effect and channel competition, constructs the emission reduction and pricing dual-channel model, obtains the optimal decision under three carbon-emission policy scenarios, and examines the impacts of channel preference, price reference effect, and mixed policies on the optimal outcomes. It also discusses the better conditions for economic and environmental benefits within the mixed policy. The main findings can be summarized as follows, which systematically answer the research questions posed in this study.

- The optimal decisions under the three policy scenarios have been rigorously derived, elucidating the dual mechanism of “constraint and incentive” inherent in different carbon policies. This study provides precise solutions for optimal emission reduction level, wholesale price, and selling prices across policy contexts. All equilibrium outcomes emerge from strategic trade-offs between environmental compliance costs and market returns generated through channel competition and consumer preference dynamics.

- The impact of parameters such as channel preference, price reference effect, carbon tax, and carbon cap on optimal outcomes is context dependent. Firstly, a non-linear relationship exists between online channel preference and manufacturer profitability. Specifically, profit follows a U-shaped trajectory as online preference increases, initially declining before reaching a turning point and subsequently rising. Carbon policy parameters, tax rates and quota stringency, directly determine the location of this inflection point. More lenient carbon policies can prompt this profit turning point to occur earlier. Secondly, the impact of the price reference effect is contingent on market conditions. In markets with lower basic market demand, a strong price reference effect leads to enhanced emission reduction level, selling prices, and profitability. Conversely, in high-demand markets, it intensifies channel competition, leading to depressed prices and diminished profits, thereby complicating emission-reduction decisions. Thirdly, the effectiveness of carbon taxes and quotas is highly based on initial emission per unit. Low-emission producers can effectively manage compliance costs and maintain price stability, even achieving profit gains under tightening quotas. In contrast, high-emission manufacturers must resort to price adjustments and cost restructuring to mitigate regulatory pressure. Notably, the profitability is optimized under specific policy settings: either “low tax/lenient quota” or “high tax/stringent quota” regimes. It indicates that economic incentives and regulatory constraints jointly drive the advancement of green products.

- The mixed policy can achieve a “win-win” outcome for both economic and environmental performance through its synergistic effect under specific conditions. Based on a comparative analysis of the three policies, the mixed policy does not represent a mere superposition of single-policy instruments. Its core advantage lies in the synergistic effects; the carbon quota establishes a baseline for environmental performance, while the carbon tax provides continuous economic incentives to exceed this baseline. Numerical simulations further reveal that the mixed policy realizes its full synergistic potential in large and stable markets, particularly when governments set more flexible carbon quotas, thereby simultaneously improving supply chain profitability and emission reductions.

8.2. Managerial Insights and Limitations

There are some management implications outlined in the abovementioned research.

Firstly, changes in consumers’ online channel preferences will affect manufacturers’ sales and profits. Managers should monitor data to capture demand changes in time and flexibly adjust channel and pricing strategies. For example, optimizing the cost structure by integrating the “order online + pick up offline” mode. Enterprises need to strengthen supply chain flexibility to cope with the growth of customized demand, while coordinating online and offline resources to avoid the erosion of profits from channel conflicts.

Secondly, while the price reference effect offers opportunities for businesses to develop competitive products and increase market share, it also intensifies competition and price volatility, enterprises need to design differentiated pricing based on market structure. For instance, building perceptions of price-value-performance through transparent cost-based pricing. Managers should construct a dynamic pricing mechanism that integrates the monitoring of price fluctuations in real time and breaks through homogeneous competition by technological innovation to reduce consumer price sensitivity.

Finally, considering the price reference effect and mixed policy, enterprises should design differentiated pricing based on initial emissions to attract various consumer groups, and optimize the supply chain to adapt to policy changes, reduce emissions, and enhance competitiveness.

There are also some limitations to this study:

- This study solely examines fixed reference prices; future research should account for variable reference prices influenced by market conditions, promotions, and competitor pricing to fully understand their impact on consumer behavior.

- Mixed policies, though beneficial for efficiency and emission reductions, are complex to implement. They require setting appropriate carbon taxes and quotas, establishing robust supervision, and customizing measures for different industries. Continuous adjustment and refinement are necessary to ensure their effectiveness.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.H., Y.Y. and H.T.; methodology, Y.H., S.G., F.Z. and H.T.; formal analysis, Y.H., Y.Y. and H.T.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.H.; writing—review and editing, S.G., F.Z. and H.T.; supervision, S.G. and H.T.; project administration, S.G., F.Z. and H.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Tianjin Natural Science Foundation Multi-Investment Project (Grant No. 24JCQNJC00210).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Derivation of Table 3.

- (a)

- Under decentralization, a Stackelberg game emerges between a manufacturer and a retailer, characterized by manufacturer dominance. The following is studied by backward induction.

Firstly, according to retailer’s profit function, .

Let , then we obtain .

Substituting into manufacturer’s profit function, the Hessian matrix is

Based on the assumption that , and is regarded as a larger value (), it can be concluded that the second principal minor , and the third principal minor ; therefore, is concave in , and .

Let , , and , we get

and

Substituting , , and into , we get

Then, obtain the optimal profit and total emission.

To keep the optimal decision variables in a reasonable range (e.g., , , ), it is assumed that the parameters satisfy the following conditions:

- (1)

- At , , and

- (2)

- At , when , ; when , . Where

- (b)

- From the profit function of total supply chain, the Hessian matrix is

Based on the assumption that , and is regarded as a larger value (), it can be conducted that the second principal minor , and the third principal minor ; therefore, is concave in , and .

Let , , and , we get

, , and .

Substituting , , and , obtain the optimal profit and total emission.

To keep the optimal decision variables in a reasonable range (e.g., , and ), it is assumed that the parameters satisfy the following conditions:

Appendix A.2

Derivation of Table 4.

This part is analogous to the methodology presented in Appendix A.1.

Appendix A.3

Derivation of Table 5.

This part is analogous to the methodology presented in Appendix A.1.

Appendix A.4

Proof of Proposition 1.

The first-order partial derivative of manufacturer’s profits was judged based on online channel preferences.

- (1)

- At , when , ; when , .

- (2)

- At , when , ; when ,

- (3)

- When , and ; when , and . □

Appendix A.5

Proof of Proposition 2.

The first-order partial derivation of the optimal outcome on price reference coefficient is analyzed.

- (1)

- When , , when ,

- (2)

- At , the selling prices in both channels are also equal (). When , , when , .

- (3)

- When , , when , .

- (4)

- , and . □

Appendix A.6

Proof of Proposition 3.

When , and , when , and . □

Appendix A.7

Proof of Proposition 4.

When , , and , when , , and . □

Appendix A.8

The expressions of threshold

where , and .

Appendix A.9

Proof of Corollary 1.

The supply chain’s total profits and emissions between Model M and Model TA:

- (1)

- At , when , and ; when , and .

- (2)

- At , when , and ; when , and .

To sum up, in the case of , and , Model M yields higher profits and lower emissions than Model TA. □

Appendix A.10

The expressions of threshold .

where , and .

Appendix A.11

Proof of Corollary 2.

The supply chain’s total profits and emissions between Model M and Model CT:

- (1)

- At , when , and ; when , and .

- (2)

- At , when , and ; when , and .

To sum up, in the case of , and , Model M yields higher profits and lower emissions than Model CT. □

References

- Harvey, L.D.D. Allowable CO2 concentrations under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change as a function of the climate sensitivity probability distribution function. Environ. Res. Lett. 2007, 2, 014001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christoff, P. The promissory note: COP 21 and the Paris Climate Agreement. Environ. Politics 2016, 25, 765–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, K.H.; Kakinaka, M. Renewable energy consumption, carbon emissions, and development stages: Some evidence from panel cointegration analysis. Renew. Energy 2019, 132, 1049–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, F.; Ntim, C.G. Environmental Policy, Sustainable Development, Governance Mechanisms and Environmental Performance. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2017, 27, 415–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Yang, J. Optimal decisions for competitive manufacturers under carbon tax and cap-and-trade policies. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 156, 107244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nong, D.; Simshauser, P.; Nguyen, D.B. Greenhouse gas emissions vs CO2 emissions: Comparative analysis of a global carbon tax. Appl. Energy 2021, 298, 117223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellerman, A.D.; Buchner, B.K. Over-Allocation or Abatement? A Preliminary Analysis of the EU ETS Based on the 2005–06 Emissions Data. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2008, 41, 267–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, J.J. Carbon Taxes and CO2 Emissions: Sweden as a Case Study. Am. Econ. J. Econ. Policy 2019, 11, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Jin, S.; Jiang, H. Investigation of complex dynamics and chaos control of the duopoly supply chain under the mixed carbon policy. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2022, 164, 112492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Cao, X.; Alharthi, M.; Zhang, J.; Taghizadeh-Hesary, F.; Mohsin, M. Carbon emission transfer strategies in supply chain with lag time of emission reduction technologies and low-carbon preference of consumers. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 264, 121664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Kevin Chiang, W.y.; Liang, L. Strategic pricing with reference effects in a competitive supply chain. Omega 2014, 44, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Gou, Q.; Tang, W.; Zhang, J. Joint pricing and advertising strategy with reference price effect. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2016, 54, 5250–5270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Yuan, P.; Hua, L. Pricing and financing strategies of a dual-channel supply chain with a capital-constrained manufacturer. Ann. Oper. Res. 2022, 329, 1241–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamzaoui, A.F.; Turki, S.; Rezg, N. Unified strategy of production, distribution and pricing in a dual-channel supply chain using leasing option. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2024, 62, 7167–7185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chiang, W.-Y.K. Durable goods pricing with reference price effects. Omega 2020, 91, 102018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Bi, W.; Liu, H. Dynamic Pricing with Parametric Demand Learning and Reference-Price Effects. Mathematics 2023, 11, 2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Pan, X.; Li, J.; Feng, S.; Guo, S. Comparing the impacts of carbon tax and carbon emission trading, which regulation is more effective? J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 330, 117156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.X.; He, P.F.; Cheng, T.; Xu, S.Y.; Pang, C.; Tang, H.J. Optimal strategies for carbon emissions policies in competitive closed-loop supply chains: A comparative analysis of carbon tax and cap-and-trade policies. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2024, 195, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, R.; Zhang, C.; Li, Z.; Li, Y. Manufacturers’ integrated strategies for emission reduction and recycling: The role of government regulations. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 163, 107769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Wang, C.; Zhao, J. Decision and coordination in the dual-channel supply chain considering cap-and-trade regulation. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 197, 551–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, R.; Pei, Z. Return policies and O2O coordination in the e-tailing age. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 50, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouri-Harzvili, M.; Hosseini-Motlagh, S.-M.; Pazari, P. Optimizing the competitive service and pricing decisions of dual retailing channels: A combined coordination model. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 163, 107789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, B.; Sarkar, A.; Sarkar, B. Optimal decisions in a dual-channel competitive green supply chain management under promotional effort. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 211, 118315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, H.; Sun, Y. Implementing coordination contracts in a manufacturer Stackelberg dual-channel supply chain. Omega 2012, 40, 571–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, B.C.; Chakraborty, A.; Maiti, T. Pricing and return product collection decisions in a closed-loop supply chain with dual-channel in both forward and reverse logistics. J. Manuf. Syst. 2017, 42, 104–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, B.; You, T.; Liu, C.; Zhao, J. Pricing and Channel Coordination in Online-to-Offline Supply Chain Considering Corporate Environmental Responsibility and Lateral Inventory Transshipment. Mathematics 2021, 9, 2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Tang, H.; Lin, Z.; Xin, B. Inventory and Ordering Decisions in Dual-Channel Supply Chains Involving Free Riding and Consumer Switching Behavior with Supply Chain Financing. Complexity 2021, 2021, 530124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Lai, I.K.W.; Tang, H. Pricing and Contract Coordination of BOPS Supply Chain Considering Product Return Risk. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Tang, H.; Lin, Z.; Lu, J. Pricing and sales-effort analysis of dual-channel supply chain with channel preference, cross-channel return and free riding behavior based on revenue-sharing contract. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2022, 249, 108506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, L. Carbon emission reduction decisions in the retail-/dual-channel supply chain with consumers’ preference. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 141, 852–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Hu, Z.; Shi, V.; Wang, Q. Manufacturer’s encroachment strategy with substitutable green products. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2021, 235, 108102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Tang, H.; Huang, Y. Decisions of pricing and delivery-lead-time in dual-channel supply chains with data-driven marketing using internal financing and contract coordination. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2023, 123, 1005–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Liu, N. Research on closed loop supply chain with reference price effect. J. Intell. Manuf. 2014, 28, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z. Price promotion with reference price effects in supply chain. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2016, 85, 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, D.; Spann, M. Dynamic pricing and reference price effects. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 152, 300–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Zhao, W.; Yu, Y. Optimal product line design with reference price effects. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2022, 302, 1045–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Du, B.; Chen, Z.; Cheng, J. The government subsidy design considering the reference price effect in a green supply chain. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 22645–22662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Hu, P.; Hu, Z. Efficient Algorithms for the Dynamic Pricing Problem with Reference Price Effect. Manag. Sci. 2017, 63, 4389–4408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entezaminia, A.; Gharbi, A.; Ouhimmou, M. A joint production and carbon trading policy for unreliable manufacturing systems under cap-and-trade regulation. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 293, 125973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Lai, K.K.; Li, Y. Remanufacturing and low-carbon investment strategies in a closed-loop supply chain under multiple carbon policies. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2022, 27, 170–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, Y. Optimal pricing and green decisions in a dual-channel supply chain with cap-and-trade regulation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 28208–28225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Tian, Y.-X.; Han, M.-H. Recycling mode selection and carbon emission reduction decisions for a multi-channel closed-loop supply chain of electric vehicle power battery under cap-and-trade policy. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 375, 134060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindan, K.; Salehian, F.; Kian, H.; Hosseini, S.T.; Mina, H. A location-inventory-routing problem to design a circular closed-loop supply chain network with carbon tax policy for achieving circular economy: An augmented epsilon-constraint approach. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2023, 257, 108771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harijani, A.M.; Mansour, S.; Fatemi, S. Closed-loop supply network of electrical and electronic equipment under carbon tax policy. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 78449–78468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Sun, C.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhou, P. Carbon emission reduction policy with privatization in an oligopoly model. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 45209–45230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Lin, F.; Cheng, T.C.E.; Jia, F.; Sun, Y. Carbon allowance approach for capital-constrained supply chain under carbon emission allowance repurchase strategy. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2023, 123, 2488–2521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Xi, X.; Goh, M. Differential game analysis of joint emission reduction decisions under mixed carbon policies and CEA. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 358, 120913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M. Green investment and e-commerce sales mode selection strategies with cap-and-trade regulation. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2023, 177, 109036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Pang, C.; Tang, H. Pricing and Carbon-Emission-Reduction Decisions under the BOPS Mode with Low-Carbon Preference from Customers. Mathematics 2023, 11, 2736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fibich, G.; Gavious, A.; Lowengart, O. Explicit Solutions of Optimization Models and Differential Games with Nonsmooth (Asymmetric) Reference-Price Effects. Oper. Res. 2003, 51, 721–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Gou, Q.; Liang, L.; Huang, Z. Supply chain coordination through cooperative advertising with reference price effect. Omega 2013, 41, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazumdar, T.; Raj, S.P.; Sinha, I. Reference Price Research: Review and Propositions. J. Mark. 2005, 69, 84–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Ji, J.N. Pricing and carbon emission reduction decisions in supply chains with vertical and horizontal cooperation. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2017, 191, 286–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, C.H.; Wang, C.X.; Zhao, Y.B. Closed-loop supply chain models for a high-tech product under alternative reverse channel and collection cost structures. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2014, 156, 108–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.K.; Akmalul’Ulya, M. Analyses of the reward-penalty mechanism in green closed-loop supply chains with product remanufacturing. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2019, 210, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.R.; Wu, Q.H. Carbon emission reduction and product collection decisions in the closed-loop supply chain with cap-and-trade regulation. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2021, 59, 4359–4383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Ma, J.; Li, J. Dynamic production and carbon emission reduction adjustment strategies of the brand-new and the remanufactured product under hybrid carbon regulations. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 172, 108517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjaafar, S.; Li, Y.; Daskin, M. Carbon Footprint and the Management of Supply Chains: Insights From Simple Models. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2013, 10, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Lin, F.; Cheng, T.C.E. Low-Carbon Transition Models of High Carbon Supply Chains under the Mixed Carbon Cap-and-Trade and Carbon Tax Policy in the Carbon Neutrality Era. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, J.; Owen, A.D. Emission trading schemes: Potential revenue effects, compliance costs and overall tax policy issues. Energy Policy 2009, 37, 4595–4603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solilová, V.; Nerudová, D. Overall Approach of the EU in the Question of Emissions: EU Emissions Trading System and CO2 Taxation. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2014, 12, 616–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]