Simple Summary

The marine bivalves of the genus Hyotissa (family Gryphaeidae) are important for ocean ecosystems and fisheries; however, their molecular biology information is notably scarce. Our study aimed to specifically explore crucial defense genes called superoxide dismutases (SODs), which act as the body’s natural defenders against cellular damage. We discovered 46 diverse SOD genes in three Hyotissa species. Our analysis revealed that these genes possess both ancient, conserved features and newer, diversified characteristics. Intriguingly, we found specialized SODs like Dominin and copper-only SOD repeat proteins (CSRPs), exhibiting structural changes hinting at new roles. These variations suggest Hyotissa’s protective genes have adapted to perform various tasks, potentially enabling them to thrive in demanding reef environments characterized by high ultraviolet radiation and high oxygen levels. This study provides foundational transcriptomic resources for Hyotissa and offers new insights into the evolution and environmental adaptation of SOD genes in marine bivalves.

Abstract

The genus Hyotissa (family Gryphaeidae) comprises ecologically and economically important marine bivalves, yet their molecular biology remains poorly characterized. This study presents de novo transcriptome sequencing of three Hyotissa species—H. sinensis, H. inaequivalvis, and Hyotissa sp.—to systematically identify and characterize the superoxide dismutase (SOD) gene family, a crucial component of the antioxidant defense system. We identified 46 SOD genes, including both Cu/Zn-SOD and Fe/Mn-SOD types, which exhibited considerable variation in molecular properties, domain architecture, and potential phosphorylation sites. Phylogenetic analysis revealed both evolutionary conservation and diversification of SODs across species. Notably, we identified homologs of two specialized SOD types: Dominin, which showed mutations in metal-binding sites suggestive of functional divergence, and copper-only SOD repeat proteins (CSRPs), which retained copper-binding residues but lost zinc-binding capacity. These findings suggest that the SOD family in Hyotissa has undergone significant functional diversification, potentially as an adaptive response to their high-oxygen, high-ultraviolet reef habitats. This study provides foundational transcriptomic resources for Hyotissa and offers new insights into the evolution and environmental adaptation of SOD genes in marine bivalves.

1. Introduction

The superfamily Ostreoidea, which includes the families Gryphaeidae and Ostreidae, represents a major clade of marine bivalves [1]. While Ostreidae has been relatively well-studied, Gryphaeidae diverged earlier, during the Permian–Triassic period [2]. Within Gryphaeidae, the genus Hyotissa has notably rich species [3], making it a valuable group for understanding evolutionary trajectories and adaptive diversification in Ostreoidea. Hyotissa species are widely distributed in tropical and subtropical waters of the Western Atlantic, Indo-Pacific, and Eastern Pacific [4,5]. They are typically large, with thick shells, prominent radial ribs, and unique vesicular microstructures [6,7]. The complex three-dimensional structure of their shells provides habitat for diverse microfauna, underscoring their ecological importance [8]. Additionally, the adductor muscle of Hyotissa species—comprising over half of their soft tissue—is highly valued for its quality, giving these species significant economic value and aquaculture potential [9].

Superoxide dismutase (SOD) is a key antioxidant enzyme that catalyzes the dismutation of superoxide anion (O2−) into oxygen and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), thereby mitigating reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reducing oxidative damage [10,11,12]. SODs are classified based on their metal cofactors into Cu/Zn-SOD, Fe/Mn-SOD, and Ni-SOD types [13]. In eukaryotes, Cu/Zn-SODs are further divided into intracellular (icCu/Zn-SOD) and extracellular (ecCu/Zn-SOD) forms, which differ in subcellular localization and function [14]. Recent studies have revealed considerable expansion and functional diversification of the SOD gene family in some invertebrates [15,16,17]. For instance, the extracellular Cu/Zn-SOD homolog Dominin in oysters appears to have lost canonical SOD activity, acquiring new roles in metal binding and immune regulation [18,19,20]. Similarly, the recently discovered copper-only SOD (Cu-only SOD) and its multi-domain form, copper-only SOD repeat proteins (CSRPs), retain conserved copper-binding sites for catalysis but have mutated zinc-binding sites, further enriching the functional diversity of the SOD family [21,22].

Unlike Ostreidae species such as the Pacific oyster (Crassostrea gigas), which inhabit estuarine, intertidal, or shallow marine environments with muddy or sandy substrates, Hyotissa species typically attach to coral reefs or other hard substrates [23,24]. These habitats are characterized by clear water, stable high salinity, warm temperatures, and intense ultraviolet radiation, leading to elevated oxidative stress [23]. Such conditions, particularly high UV exposure and temperature, promote persistent ROS production [25]. As SODs constitute the first line of defense in the antioxidant system, the pronounced oxidative stress in Hyotissa habitats may have driven adaptive evolution in their SOD gene family, resulting in a more robust antioxidant defense system.

Advances in high-throughput sequencing have revolutionized biological research, enabling large-scale genomics and transcriptomics projects [26]. However, despite the recent completion of the first chromosome-level genome for H. hyotis [27], genomic and transcriptomic data for Hyotissa remain scarce in public databases like NCBI. This data gap has led to species misidentification (e.g., H. hyotis being mislabeled as H. sinensis) and has hindered related research. To address this, we performed de novo transcriptome sequencing of three Hyotissa species and systematically identified and characterized their SOD genes. Our analysis of molecular characteristics, conservation, and specificity provides a foundation for understanding environmental adaptation and phenotypic evolution in Gryphaeidae oysters.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

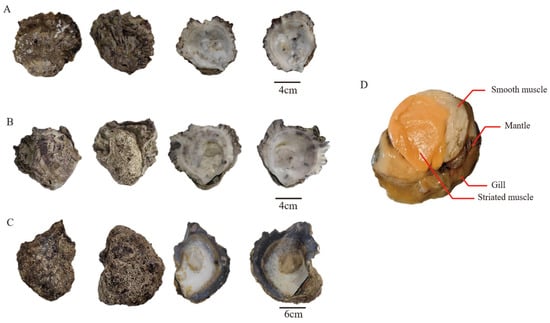

Five wild Hyotissa individuals were collected from Weizhou Island, Beihai City, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, China (21°02′4″ N, 109°06′6″ E). Based on mitochondrial 16S rRNA gene fragment sequencing, three species were identified: individuals 1 and 3 as Hyotissa inaequivalvis, individual 2 as Hyotissa sp. and individuals 4 and 5 as Hyotissa sinensis [28]. After collection, each oyster was dissected to separate gill, mantle, smooth muscle, and striated muscle tissues (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Shell morphology of three Hyotissa species. (A) Hyotissa sp., (B) H. inaequivalvis, (C) H. sinensis, (D) Schematic of tissues for transcriptomic analysis.

2.2. Total RNA Extraction and Quality Control

Total RNA was extracted from four tissues using the TRNzol Universal Reagent Kit (TIANGEN, Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA integrity (RIN) and quality were assessed using an Agilent 5400 Bioanalyzer (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Only RNA samples with a concentration ≥ 50 ng/µL, a RIN value > 6.0, and no detectable protein or organic solvent contamination were used for cDNA library construction.

2.3. Library Construction and Sequencing

Libraries were constructed and sequenced by Novogene Corporation (Beijing, China). The Fast RNA-seq Lib Prep Kit V2 (Abclonal, Wuhan, China) was used for mRNA enrichment, fragmentation, and cDNA library construction. Libraries were preliminarily quantified with a Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (Thermo, Waltham, MA, USA), diluted to 1.5 ng/μL, and insert size was assessed with an Agilent 5400 Bioanalyzer. After confirming expected insert size, the effective concentration was quantified via qRT-PCR to ensure ≥1.5 nM. Qualified libraries were sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq X Plus platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA), generating 150 bp paired-end reads, with a target data output of 6 G for each library.

2.4. RNA-Seq Data Processing and Quality Control

Raw read quality was assessed with FastQC (v0.12.1) for base quality, GC content, duplication rate, overrepresented k-mers, and quality score distribution [29]. MultiQC (v1.30) aggregated quality metrics across samples [30]. Raw reads were processed with fastp (v0.19.7) [31] to remove adapter-containing reads, poly-N sequences, and low-quality reads, yielding clean reads. Q20 scores, Q30 scores, and GC content of the clean data were calculated.

2.5. Transcriptome Assembly

In this study, we performed independent de novo transcriptome assembly and annotation for five Hyotissa individuals. For each oyster, high-quality sequencing data were assembled de novo using Trinity (v2.13.2), yielding five separate transcriptomes [32]. The assembly was performed using default parameters optimized for transcriptome data. The completeness of the transcriptome assembly was assessed using Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs (BUSCO) software (v5.5.0) with default parameters. Each assembly was compared with the mollusca_odb10 database (http://busco.ezlab.org/) (accessed on 10 December 2025) to evaluate its completeness [33]. Then, TransDecoder (v5.5.0) was used to predict the open reading frames (ORFs) of the filtered nucleotide sequences and translate them into protein sequences [34]. The longest protein sequence from the resulting protein sequence file was extracted as the input file for subsequent analysis.

2.6. Transcriptome Assembly and SOD Gene Identification

SOD genes were identified from transcriptomic data of five Hyotissa individuals. Gene IDs were labeled with individual-specific prefixes (“Hsi1-2”, “Hin1-2”, “Hsp1”) to denote species origin. Candidate SOD sequences were obtained using BLAST (v2.12.0) and HMMER (v3.2.1) with significant hits (E-value ≤ 1.00 × 10−10) and SOD domain matches (PF00080, PF00081, PF02777; E-value ≤ 1.00 × 10−10). Domain presence was verified with SMART (https://smart.embl.de/) (accessed on 15 May 2025). Genes with partial coding sequences were excluded from further analysis.

2.7. Molecular Characterization of SOD Family Members

Amino acid length, molecular weight (kDa), isoelectric point (pI), instability index, aliphatic index, and grand average of hydropathicity (GRAVY) were calculated using Expasy ProtParam (https://web.expasy.org/protparam/) (accessed on 15 May 2025) with default parameters [35]. Subcellular localization was predicted with WoLFPSORT (https://wolfpsort.hgc.jp/) (accessed on 15 May 2025) with default parameters [36]. Phosphorylation sites were predicted using NetPhos (v3.1) (https://services.healthtech.dtu.dk/services/NetPhos-3.1/) (accessed on 15 May 2025) [37]. The prediction score ranges from 0.000 to 1.000, and sites with a score above the threshold of 0.500 were considered positive predictions. Signal peptides and transmembrane domains were analyzed using SignalP 6.0 with default settings (https://services.healthtech.dtu.dk/services/SignalP-6.0/) (accessed on 15 May 2025) [38]. Conserved motifs were identified with MEME (https://meme-suite.org/meme/tools/meme) (accessed on 15 May 2025), with the maximum number set to 10 and other parameters as default [39].

2.8. Sequence Alignment and Phylogenetic Analysis

The SOD genes identified from the transcriptome data of Hyotissa were subjected to multiple sequence alignment with the SOD protein sequences retrieved from the NCBI database for Pacific oyster (Crassostrea gigas), human (Homo sapiens), mouse (Mus musculus), zebrafish (Danio rerio), fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster), and nematode (Caenorhabditis elegans). The alignment was performed using MAFFT software (v7.526) with the BLOSUM62 amino acid substitution matrix [40]. The best substitution model (WAG+G) was selected using MEGA 11, and a phylogenetic tree was constructed using the Maximum Likelihood (ML) method in MEGA 11, with branch support assessed by the bootstrap method with 1000 replicates.

To further analyze the evolutionary relationships of the two specialized SOD types in oysters, Dominin and CSRP, the Dominin3 (XP_011439797.1) and CSRP (XP_034330263.1) sequences from C. gigas were used as a reference to search for homologous sequences in transcriptomic data from five individuals of the Hyotissa genus, with an E-value threshold of less than 1 × 10−10 and a query coverage greater than 40% as screening criteria. The homologous Dominin sequences identified from the Hyotissa genus were subjected to multiple amino acid sequence alignment with the intracellular Cg-Cu/Zn-SOD (XP_034334952.2) from C. gigas [20], Cg-Dominin3, human extracellular SOD (HuEcSOD, P08294), and human cytoplasmic SOD (HuCySOD, P00441) to analyze their key active sites, and a phylogenetic tree was constructed. Additionally, the individual SOD domains of Hyotissa CSRP were aligned with HuEcSOD (P08294), HuCySOD (P00441), and C. gigas intracellular Cu/Zn-SOD (XP_034334952.2) using multiple sequence alignment to analyze the conserved amino acid residues essential for copper ion coordination in their active sites.

3. Results

3.1. Technical Validation of Transcriptome Sequencing

Illumina sequencing generated 464,824,286 paired-end reads (Table 1). The number of raw reads per sample ranged from 21,172,853 to 24,393,919. MultiQC reports confirmed high base quality (Phred score > 35) and high mean quality scores across sequences. After processing with fastp, 456,109,722 high-quality clean read pairs were obtained. This corresponded to a per-sample clean read count range of 20,776,969 to 25,021,203 reads. Q20 and Q30 scores were ≥98.07% and ≥94.23%, respectively, and GC contents were within expected ranges (Table 1). After assembly, the number of transcripts across the five samples ranges from 327,624 to 379,502, with assembly continuity, as measured by N50, varying between 1324 and 1595 bp (Table S1). Additionally, BUSCO analysis revealed high completeness (Table S2). These findings show that a high-quality RNA-seq dataset was successfully generated. Raw transcriptome data are available in the NCBI SRA under accession number PRJNA1356962.

Table 1.

Summary of sequencing data quality.

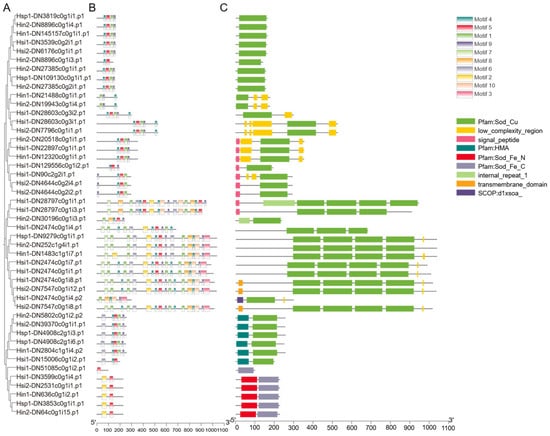

3.2. Identification of the SOD Gene Family

A total of 46 SOD family genes were identified from the five Hyotissa transcriptomes: six each from Hin1 and Hsp1, ten from Hin2, sixteen from Hsi1, and eight from Hsi2 (Table 2 and Table S3). Domain analysis classified five sequences as Fe/Mn-SODs, based on the presence of N-terminal Fe/Mn-SOD α-hairpin (PF00081) and C-terminal Fe/Mn-SOD (PF02777) domains; one sequence contained only the C-terminal domain. The remaining sequences contained one to four Sod_Cu domains (PF00080) and were identified as Cu/Zn-SOD homologs. Six of these also contained a heavy metal-associated (HMA) domain (PF00403) (Figure 2).

Table 2.

Physicochemical properties of Hyotissa SOD proteins.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic, motif, and domain analysis of Hyotissa SODs. (A) ML phylogenetic tree of SOD proteins. (B) Conserved motifs (colored boxes). (C) Conserved domains. Hsi: Hyotissa sinensis, Hin: Hyotissa inaequivalvis, Hsp: Hyotissa sp.

Physicochemical properties varied widely: amino acid lengths ranged from 95 to 1035 residues, molecular weights from 11.06 to 112.32 kDa, and pI from 5.10 to 9.75 (mostly 5.5–7.8). Instability indices ranged from 14.29 to 54.06, with many exceeding 40, indicating potential instability. Aliphatic indices were generally high (>70), suggesting thermostability. All proteins had negative GRAVY values, indicating hydrophilicity. Twelve proteins possessed signal peptides, suggesting extracellular secretion or organelle localization. Phosphorylation sites ranged from 5 to 130, with Hin1-DN1483c1g1i7.p1 having the highest number, indicating potential for functional diversification.

MEME analysis identified ten conserved motifs (Figure 2B). Motif 1, associated with the Sod_Cu domain, was present in all Cu/Zn-SODs. Except for Hsi1-DN51085c0g1i2.p1, all Fe/Mn-SODs contained Motif 2 (N-terminal Fe/Mn-SOD α-hairpin) and Motif 5 (C-terminal Fe/Mn-SOD domain).

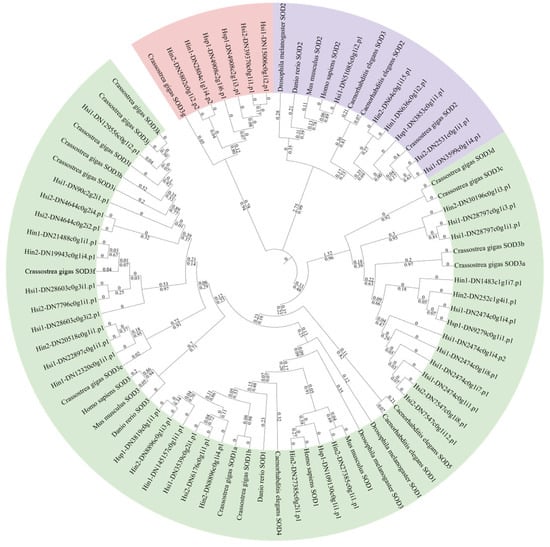

3.3. Phylogenetic Analysis of Hyotissa SOD

A phylogenetic tree was constructed using SOD sequences from Hyotissa and six other species. Due to significant expansion in C. gigas, its SODs were designated SOD1a-b, SOD2, and SOD3a-l based on relationships with intracellular Cu/Zn-SOD (SOD1), Mn-SOD (SOD2), and extracellular Cu/Zn-SOD (SOD3). The tree revealed three major clades: Cu/Zn-SOD (48% bootstrap), Mn-SOD (99% bootstrap), and copper chaperone for SOD (94% bootstrap) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

ML phylogenetic tree of SODs from Hyotissa and six reference species, with bootstrap values from 1000 replicates and branch lengths displayed. Green: Cu/Zn-SOD, Purple: Mn-SOD, Red: Copper chaperone for SOD. Hsi: Hyotissa sinensis, Hin: Hyotissa inaequivalvis, Hsp: Hyotissa sp.

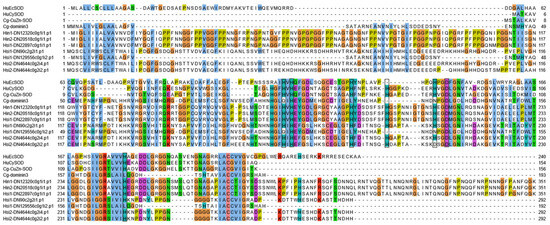

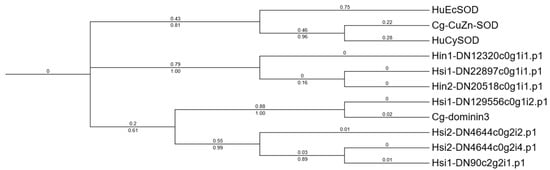

3.4. Sequence Analysis of the ecSOD Homolog Dominin in Hyotissa

Seven Dominin homologs were identified in the Hyotissa transcriptomes. Sequence alignment with Cg-Cu/Zn-SOD, Cg-Dominin3, HuEcSOD, and HuCySOD showed that Hsi1-DN129556c0g1i2.p1 shared five metal-binding site mutations with Cg-Dominin3, while Hsi2-DN4644c0g2i2.p1 had only one mutation. The other five homologs were identical to Cg-Cu/Zn-SOD at all seven metal-binding sites (Figure 4). Phylogenetic analysis indicated divergent evolution: one group was orthologous to C. gigas Dominin3, while the other formed a distinct clade (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Multiple alignment of Hyotissa Dominin homologs with reference SODs-Cg-icCu/Zn-SOD, Cg-Dominin3, HuCySOD, and HuEcSOD. Black boxes: Metal-binding sites. Hsi: Hyotissa sinensis, Hin: Hyotissa inaequivalvis.

Figure 5.

ML phylogenetic tree of Hyotissa Dominin homologs and reference SODs. Cg-Cu/Zn-SOD, Cg-Dominin3, HuCySOD, and HuEcSOD, with bootstrap values from 1000 replicates and branch lengths displayed. Hsi: Hyotissa sinensis, Hin: Hyotissa inaequivalvis.

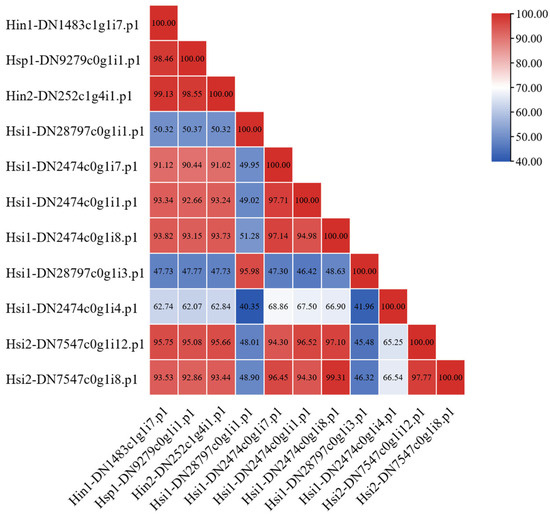

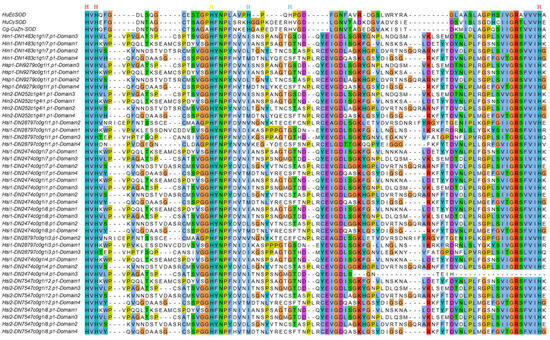

3.5. Sequence and Domain Comparison of Hyotissa CSRPs

Eleven CSRPs were identified among the 46 SOD genes. Pairwise amino acid identity ranged from 40.35% to 99.31% (Figure 6). The amino acid coordinates for all Cu-SOD domains are listed; two CSRPs were found to contain only three such domains, while the remaining nine contained the typical four-domain architecture (Table S4). Except for two sequences with three Cu-SOD domains, all others had four. Alignment showed that Hyotissa CSRP domains retained the five conserved residues for Cu2+ coordination but had mutations in two histidine residues critical for Zn2+ binding (Figure 7).

Figure 6.

Amino acid sequence similarity of Hyotissa CSRPs (percent similarity shown). Hsi: Hyotissa sinensis, Hin: Hyotissa inaequivalvis, Hsp: Hyotissa sp.

Figure 7.

Alignment of Hyotissa CSRP Cu-SOD domains with reference SODs. Red: Cu-binding sites, Yellow: Dynamic histidine, Blue: Zn-binding sites. Hsi: Hyotissa sinensis, Hin: Hyotissa inaequivalvis, Hsp: Hyotissa sp.

4. Discussion

Despite extensive omics data for Ostreidae (e.g., C. gigas, C. hongkongensis) [24,41], Hyotissa (Gryphaeidae) remains underrepresented in public databases—with only H. hyotis’ genome recently published [27]. This scarcity has hindered studies of trait-associated genes (e.g., stress resistance, biomineralization) and molecular mechanisms of adaptation, and our de novo transcriptomes of three Hyotissa species address this gap, providing a resource for functional gene mining and evolutionary research.

The 46 identified SOD genes (Cu/Zn-SOD, Fe/Mn-SOD) exhibit broad variation in domains, physicochemical properties, and phosphorylation sites—suggesting functional flexibility. Phylogenetic alignment with model organisms confirms their evolutionary conservation while highlighting Hyotissa-specific diversification, likely driven by coral reef stressors (high UV, oxidative stress). Since such stress results in elevated ROS levels, antioxidant enzymes are upregulated in response to stress stimuli in order to protect the organism from cellular damage [42,43]. The Hyotissa-specific SOD lineages may facilitate a more robust and tiered defense system, allowing these bivalves to thrive in highly fluctuating reef habitats.

Dominin, a major plasma protein in Crassostrea virginica, constitutes over 40% of plasma and pallial cavity fluid protein, indicating a critical physiological role. Despite having a Cu/Zn-SOD domain, mutations in five metal-coordinating histidines abolish SOD activity [18,19,20]. Among the seven Dominin homologs identified in Hyotissa, phylogenetic analysis revealed two groups: one orthologous to C. gigas Dominin3 and another distinct clade. Beyond descriptive sequence alignment—which showed varying mutations in metal-binding sites—we infer potential functional divergences. Sequence alignment showed varying metal-binding site mutations: Hsi1-DN129556c0g1i2.p1 shared five mutations with Cg-Dominin3, likely losing SOD activity, while Hsi2-DN4644c0g2i2.p1 had only one mutation, potentially preserving SOD activity [20]. The other five homologs contain fully conserved metal-binding sites, indicating they may function as active extracellular SODs (EC-SODs). This contrasts sharply with Ostreidae oysters, which appear to have evolved Dominin primarily as a non-enzymatic protein, possibly leaving them without an EC-SOD-active form. These differences suggest divergent evolutionary paths in immune-related protein function between oyster families, which may reflect adaptation to distinct physiological or environmental challenges.

CSRPs, multi-domain copper-only antioxidant enzymes, have been identified in various oysters [17]. They possess SOD activity and are upregulated under stress, indicating a role in extracellular antioxidant defense [22]. We identified several CSRP homologs, four with Cu-SOD domains and two with three domains. The latter deviates from the typical four-domain architecture in Ostreidae, possibly due to incomplete assembly. One domain in Hsi1-DN2474c0g1i4.p1 lacked a full set of conserved residues. These are tentatively classified as “candidate CSRP genes with three Cu-SOD domains,” requiring full-length cDNA validation. If confirmed, a three-domain CSRP in Hyotissa would suggest that the four-domain structure is not essential for antioxidant defense under certain evolutionary pressures. From an evolutionary perspective, the reduction in repeated domains often correlates with functional specialization, structural stability adjustment, and adaptive optimization [44]. The three-domain architecture in Hyotissa may therefore not represent a simple loss but a refined adaptation to its unique habitat. This streamlined form could alter protein–protein interactions or ROS-scavenging kinetics, representing an evolutionary trade-off that balances antioxidant capacity with the specific environmental pressures characteristic of its niche, such as thermal fluctuations, hypoxia, or osmotic stress.

Finally, this study has limitations that should be addressed in future research: the small sample size (n = 5 individuals) may limit the representativeness and generalizability of the findings, the three-domain CSRP structure requires full-length cDNA cloning to rule out assembly gaps, SOD activity assays (e.g., for Dominin and CSRPs) are needed to confirm enzymatic capacity, and integrating additional Hyotissa genomes will clarify SOD family evolution across Gryphaeidae.

5. Conclusions

In summary, this study provides high-quality transcriptomic resources for three Hyotissa species, addressing a significant data gap. We systematically identified the SOD gene family and revealed its evolutionary relationships through cross-species comparison. Further analysis of Dominin and CSRP homologs uncovered potential diversity in antioxidant defense mechanisms within this genus. Crucially, the next critical step involves rigorous functional validation of the identified SOD genes, for example, through gene expression analysis under oxidative stress, protein activity assays, or RNA interference experiments. These future functional assays, combined with genomic data from additional species, will not only validate our current findings but also further elucidate the evolutionary history of the SOD family in bivalves and the molecular basis of their environmental adaptation.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/biology15010004/s1, Table S1: Transcriptome statistics. Table S2: BUSCO completeness assessment. Table S3: Raw transcript expression levels (TPM) of SOD genes in Hyotissa. Table S4: Physicochemical properties of Hyotissa CSRP. Supplementary material provides the complete sequences (FASTA format) of all 46 superoxide dismutases, their predicted functional motifs and domain annotations, as well as the generated multiple sequence alignments and phylogenetic trees (Newick format).

Author Contributions

Q.X. and Z.L. designed and supervised the experiment. X.K. performed the experiments. X.K., S.L., S.Z. and Y.L. analyzed the data. X.K. and S.L. wrote and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32002428, 32273110), the “3315” Innovative Team of Ningbo City, Ningbo Public Welfare Science and Technology Program (2023S144, 2021S009), the Key Research and Development Program of Ningbo City (2023Z125), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFD2400304), the Fundamental Research Funds for Zhejiang Province Universities, and the China Agriculture Research System supported by MOF and MARA.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study focused solely on non-vertebrate oysters and did not involve human participants, vertebrate animals, or endangered species. Therefore, ethical approval was not required. Oyster specimens were collected in accordance with local regulations and permits. No protected areas or endangered species were involved.

Data Availability Statement

The raw transcriptome sequencing data have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under accession number PRJNA1356962. The 16S rRNA sequence for species identification has been deposited in the NCBI database under accession numbers PX690962, PX690963, PX690964, PX690965, PX690966.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Yunwang Shen from Zhejiang Ocean University for his invaluable assistance with the de novo transcriptome assembly.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bouchet, P.; Rocroi, J.-P.; Bieler, R.; Carter, J.G.; Coan, E.V. Nomenclator of bivalve families with a classification of bivalve families. Malacologia 2010, 52, 1–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Li, C.; Wang, H.; Xu, Z. Diversity and evolution of living oysters. J. Shellfish. Res. 2018, 37, 755–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Liu, H.; Heng, X.; Zhang, Y.; Fan, M.; Wang, S.; Liu, C.; Gu, Z.; Wang, A.; Yang, Y. The complete mitochondrial genome of Hyotissa sinensis (Bivalvia, Ostreoidea) indicates the genetic diversity within Gryphaeidae. Biodivers. Data J. 2023, 11, e101333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coan, E.V.; Valentich-Scott, P. Bivalve Seashells of Tropical West America: Marine Bivalve Mollusks from Baja California to Northern Peru; Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History: Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 2012; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- Harry, H.W. Synopsis of the supraspecific classification of living oysters (Bivalvia: Gryphaeidae and Ostreidae). Veliger 1985, 28, 121–158. [Google Scholar]

- Checa, A.G.; Linares, F.; Maldonado-Valderrama, J.; Harper, E.M. Foamy oysters: Vesicular microstructure production in the Gryphaeidae via emulsification. J. R. Soc. Interface 2020, 17, 20200505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancho Vaquer, A.; Griesshaber, E.; Salas, C.; Harper, E.M.; Checa, A.G.; Schmahl, W.W. The diversity of crystals, microstructures and texture that form Ostreoidea shells. Crystals 2025, 15, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuschin, M.; Baal, C. Large gryphaeid oysters as habitats for numerous sclerobionts: A case study from the northern Red Sea. Facies 2007, 53, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duprat-Bertazzi, G.; Garcia-Dominguez, F. Reproductive cycle of the rock oyster Hyotissa hyotis (Linné, 1758) (Gryphaeidae) at the la Ballena Island, Gulf of California, México. J. Shellfish. Res. 2005, 24, 987–993. [Google Scholar]

- Sies, H.; Berndt, C.; Jones, D.P. Oxidative stress. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2017, 86, 715–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Raamsdonk, J.M.; Hekimi, S. Superoxide dismutase is dispensable for normal animal lifespan. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 5785–5790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Branicky, R.; Noë, A.; Hekimi, S. Superoxide dismutases: Dual roles in controlling ROS damage and regulating ROS signaling. J. Cell Biol. 2018, 217, 1915–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, J.; Shin, D.; Getzoff, E.; Tainer, J. The structural biochemistry of the superoxide dismutases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Proteins Proteom. 2010, 1804, 245–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zelko, I.N.; Mariani, T.J.; Folz, R.J. Superoxide dismutase multigene family: A comparison of the CuZn-SOD (SOD1), Mn-SOD (SOD2), and EC-SOD (SOD3) gene structures, evolution, and expression. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2002, 33, 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Wei, M.; Zhu, Q.; Zheng, X.; Chen, X. Whole-genome identification of SOD gene family revealed the expansion of SOD in Chinese mitten crab, Eriocheir sinensis. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part D Genom. Proteom. 2025, 56, 101618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, S.; Zhao, L.; Xun, X.; Lou, J.; Li, M.; Li, X.; Wang, S.; Zhang, L.; Hu, X.; Bao, Z. Genome-wide identification and characterization of SOD s in Zhikong scallop reveals gene expansion and regulation divergence after toxic dinoflagellate exposure. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Bao, Z.; Lin, Z.; Xue, Q. Genome-wide identification and characterization of superoxide dismutases in four oyster species reveals functional differentiation in response to biotic and abiotic stress. BMC Genom. 2022, 23, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itoh, N.; Xue, Q.-G.; Schey, K.L.; Li, Y.; Cooper, R.K.; La Peyre, J.F. Characterization of the major plasma protein of the eastern oyster, Crassostrea virginica, and a proposed role in host defense. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2011, 158, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scotti, P.D.; Dearing, S.C.; Greenwood, D.R. Characterisation of cavortin, the major haemolymph protein of the Pacific oyster (Crassostrea gigas). N. Z. J. Mar. Freshw. Res. 2007, 41, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, Z.; Liu, Y.; Chang, G.; Lin, Z.; Xue, Q. Molecular characterization of two CuZn-SOD family proteins in the Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2022, 260, 110736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinett, N.G.; Peterson, R.L.; Culotta, V.C. Eukaryotic copper-only superoxide dismutases (SODs): A new class of SOD enzymes and SOD-like protein domains. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 4636–4643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.; Liu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Liu, S.; Lin, Z.; Xue, Q. Copper only SOD repeat proteins likely act as an extracellular superoxide dismutase in oyster antioxidant defense. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 20465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titschack, J.; Zuschin, M.; Spötl, C.; Baal, C. The giant oyster Hyotissa hyotis from the northern Red Sea as a decadal-scale archive for seasonal environmental fluctuations in coral reef habitats. Coral Reefs 2010, 29, 1061–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Fang, X.; Guo, X.; Li, L.; Luo, R.; Xu, F.; Yang, P.; Zhang, L.; Wang, X.; Qi, H.; et al. The oyster genome reveals stress adaptation and complexity of shell formation. Nature 2012, 490, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Caparros, P.; De Filippis, L.; Gul, A.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Ozturk, M.; Altay, V.; Lao, M.T. Oxidative stress and antioxidant metabolism under adverse environmental conditions: A review. Bot. Rev. 2021, 87, 421–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundaray, J.K.; Dixit, S.; Rather, A.; Rasal, K.D.; Sahoo, L. Aquaculture omics: An update on the current status of research and data analysis. Mar. Genom. 2022, 64, 100967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, C.; Yang, Y.; Tan, Y.; Li, Q.; Liu, S. Chromosome-level haplotype-resolved genome assembly of the giant honeycomb oyster, Hyotissa hyotis. Sci. Data 2025, 12, 1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, C.; Chen, M.; Wang, H.; Ma, P. Diversity and distribution of oysters from Weizhou Island, China. J. Oceanol. Limnol. 2025, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cock, P.J.; Fields, C.J.; Goto, N.; Heuer, M.L.; Rice, P.M. The Sanger FASTQ file format for sequences with quality scores, and the Solexa/Illumina FASTQ variants. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, 1767–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewels, P.; Magnusson, M.; Lundin, S.; Käller, M. MultiQC: Summarize analysis results for multiple tools and samples in a single report. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 3047–3048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. Fastp: An ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabherr, M.G.; Haas, B.J.; Yassour, M.; Levin, J.Z.; Thompson, D.A.; Amit, I.; Adiconis, X.; Fan, L.; Raychowdhury, R.; Zeng, Q.; et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011, 29, 644–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simão, F.A.; Waterhouse, R.M.; Ioannidis, P.; Kriventseva, E.V.; Zdobnov, E.M. BUSCO: Assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 3210–3212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, B.J.; Papanicolaou, A.; Yassour, M.; Grabherr, M.; Blood, P.D.; Bowden, J.; Couger, M.B.; Eccles, D.; Li, B.; Lieber, M.; et al. De novo transcript sequence reconstruction from RNA-seq using the Trinity platform for reference generation and analysis. Nat. Protoc. 2013, 8, 1494–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duvaud, S.; Gabella, C.; Lisacek, F.; Stockinger, H.; Ioannidis, V.; Durinx, C. Expasy, the Swiss Bioinformatics Resource Portal, as designed by its users. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, W216–W227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, P.; Park, K.-J.; Obayashi, T.; Fujita, N.; Harada, H.; Adams-Collier, C.; Nakai, K. WoLF PSORT: Protein localization predictor. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, W585–W587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blom, N.; Sicheritz-Pontén, T.; Gupta, R.; Gammeltoft, S.; Brunak, S. Prediction of post-translational glycosylation and phosphorylation of proteins from the amino acid sequence. Proteomics 2004, 4, 1633–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teufel, F.; Almagro Armenteros, J.J.; Johansen, A.R.; Gíslason, M.H.; Pihl, S.I.; Tsirigos, K.D.; Winther, O.; Brunak, S.; von Heijne, G.; Nielsen, H. SignalP 6.0 predicts all five types of signal peptides using protein language models. Nat. Biotechnol. 2022, 40, 1023–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, T.L.; Boden, M.; Buske, F.A.; Frith, M.; Grant, C.E.; Clementi, L.; Ren, J.; Li, W.W.; Noble, W.S. MEME SUITE: Tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, W202–W208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K.; Standley, D.M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: Improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Li, Q.; Xu, L.; Wei, P.; He, P.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Guan, J.; Zhang, X.; Lin, Y.; et al. Chromosome-level analysis of the Crassostrea hongkongensis genome reveals extensive duplication of immune-related genes in bivalves. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2020, 20, 980–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Xie, C.; Dong, M.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, H.; Han, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wei, L.; Wang, X. Effects of ambient UVB light on Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas mantle tissue based on multivariate data. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 274, 116236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valavanidis, A.; Vlahogianni, T.; Dassenakis, M.; Scoullos, M. Molecular biomarkers of oxidative stress in aquatic organisms in relation to toxic environmental pollutants. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2006, 64, 178–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Björklund, Å.K.; Ekman, D.; Elofsson, A. Expansion of protein domain repeats. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2006, 2, e114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.