Pattern Learning and Knowledge Distillation for Single-Cell Data Annotation

Simple Summary

Abstract

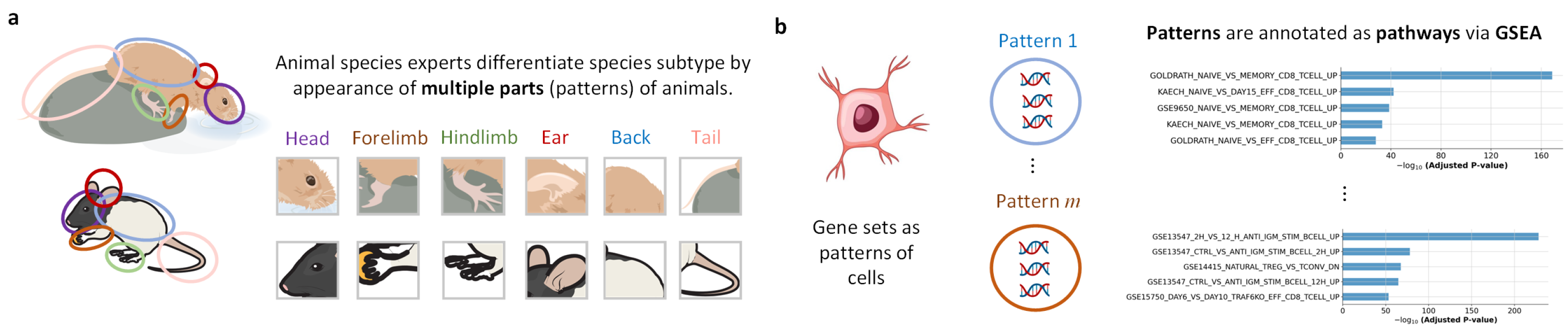

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Overall of PLKD

2.2. Inference

2.3. Training

2.4. Interpretability

- Step 1: take the j-th linear matrix from Teacher, sum it up to obtain the vector , calculate the mean of this vector as , select the indexes with values greater than the mean from , and use the genes corresponding to these indexes to form a gene set.

- Step 2: use GSEA (Gene Set Enrichment Analysis) combined with pathway annotation (gmt file on the web or locally) to obtain the pathway name corresponding to this gene set.

- Step 3: run steps 1 and 2 for other Linear matrices.

3. Datasets and Experimental Settings

3.1. Datasets

3.2. Experimental Settings

4. Results

4.1. Cell Type Annotation

4.2. Gene Inference

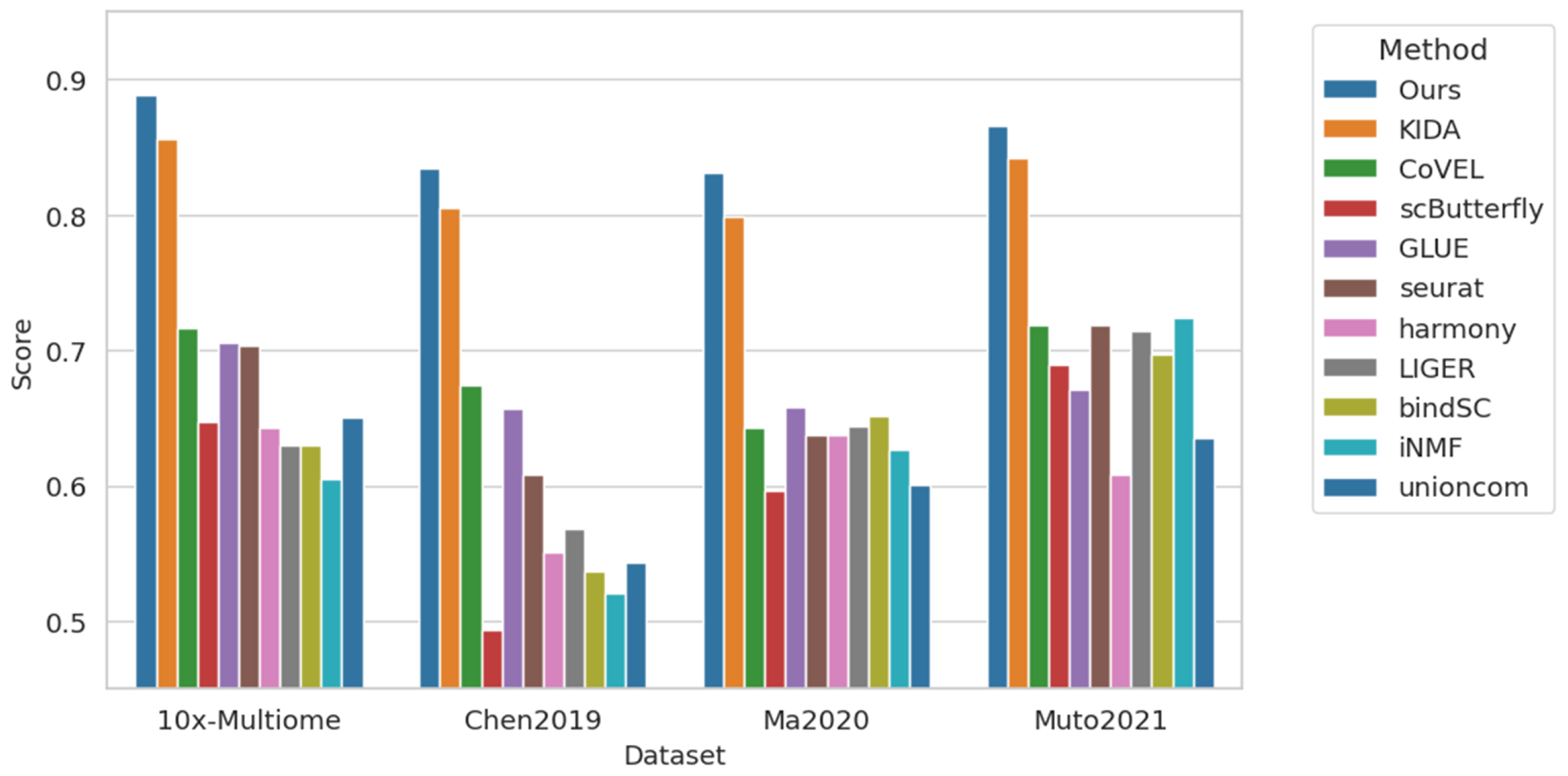

4.3. Cross-Modal Annotation

4.4. Ablation Study

- (1)

- Neither divergence-based clustering loss nor self-entropy loss is used, the optional knowledge-based mask is used, and no noise is added to reference labels; see row 2 of Table 5.

- (2)

- Use divergence-based clustering loss and self-entropy loss, do not use the optional knowledge-based mask, and do not add noise to reference labels; see row 3 of Table 5.

- (3)

- Use divergence-based clustering loss and self-entropy loss, use optional knowledge-based mask, and add noise to reference labels. For example, randomly modify the original correct label to another label, and the noise ratio is 0.1, 0.15 and 0.2, respectively; see rows 4–6 of Table 5.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- He, H.; Tang, Z.; Chen, G.; Xu, F.; Hu, Y.; Feng, Y.; Wu, J.; Huang, Y.-A.; Huang, Z.-A.; Tan, K.C. sckan: Interpretable single-cell analysis for cell-type-specific gene discovery and drug repurposing via kolmogorov-arnold networks. Genome Biol. 2025, 26, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, Q.; Chen, G.; Yang, Z.; Zhong, W.; Chen, C.Y.-C. Meta learning with graph attention networks for low-data drug discovery. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2023, 35, 11218–11230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Z.; Chen, G.; Yang, H.; Zhong, W.; Chen, C.Y.-C. Dsil-ddi: A domain-invariant substructure interaction learning for generalizable drug–drug interaction prediction. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2023, 35, 10552–10560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, Z.; Huang, F.; Fu, H.; Quan, Y.; Zhou, X.; Liu, S.; Zhang, W. Hierarchical graph representation learning for the prediction of drug-target binding affinity. Inf. Sci. 2022, 613, 507–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Chen, G.; Tang, Z.; Chen, C.Y.-C. Dual modality feature fused neural network integrating binding site information for drug target affinity prediction. npj Digit. Med. 2025, 8, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heumos, L.; Schaar, A.C.; Lance, C.; Litinetskaya, A.; Drost, F.; Zappia, L.; Lücken, M.D.; Strobl, D.C.; Henao, J.; Curion, F.; et al. Best practices for single-cell analysis across modalities. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2023, 24, 550–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luecken, M.D.; Theis, F.J. Current best practices in single-cell rna-seq analysis: A tutorial. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2019, 15, e8746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, T.; Butler, A.; Hoffman, P.; Hafemeister, C.; Papalexi, E.; Mauck, W.M.; Hao, Y.; Stoeckius, M.; Smibert, P.; Satija, R. Comprehensive integration of single-cell data. Cell 2019, 177, 1888–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, F.A.; Angerer, P.; Theis, F.J. Scanpy: Large-scale single-cell gene expression data analysis. Genome Biol. 2018, 19, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virshup, I.; Bredikhin, D.; Heumos, L.; Palla, G.; Sturm, G.; Gayoso, A.; Kats, I.; Koutrouli, M.; Berger, B.; Pe’er, D. The scverse project provides a computational ecosystem for single-cell omics data analysis. Nat. Biotechnol. 2023, 41, 604–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Yang, Y.; Xie, C.; Ni, M.; Liu, J.; Yang, H.; Mu, F.; Wang, J. Contrastive learning enables rapid mapping to multimodal single-cell atlas of multimillion scale. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2022, 4, 696–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Lin, X.; Li, Z.; Wu, H. A comprehensive comparison of supervised and unsupervised methods for cell type identification in single-cell rna-seq. Briefings Bioinform. 2022, 23, bbab567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, X.; Wang, Z.; Huang, J.; Parthasarathy, S.; Moosavinasab, S.; Huang, Y.; Lin, S.M.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, P.; Sun, H. Graph embedding on biomedical networks: Methods, applications and evaluations. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 1241–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, H.; Wang, C.; Maan, H.; Pang, K.; Luo, F.; Wang, B. scgpt: Toward building a foundation model for single-cell multi-omics using generative ai. Nat. Methods 2024, 21, 1470–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Wang, W.; Wang, F.; Fang, Y.; Tang, D.; Huang, J.; Lu, H.; Yao, J. scbert as a large-scale pretrained deep language model for cell type annotation of single-cell rna-seq data. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2022, 4, 852–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Lu, J.; Wu, H. Cellcano: Supervised cell type identification for single cell atac-seq data. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Xu, H.; Tao, W.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Han, J. Transformer for one stop interpretable cell type annotation. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Chen, G.; Chen, S.; He, H.; You, L.; Chen, C.Y.-C. Knowledge-based inductive bias and domain adaptation for cell type annotation. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Xu, X.; Zhang, J.; Li, X. Batch alignment of single-cell transcriptomics data using deep metric learning. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Hao, S.; Andersen-Nissen, E.; Mauck, W.M.; Zheng, S.; Butler, A.; Lee, M.J.; Wilk, A.J.; Darby, C.; Zager, M.; et al. Integrated analysis of multimodal single-cell data. Cell 2021, 184, 3573–3587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghverdi, L.; Lun, A.T.L.; Morgan, M.D.; Marioni, J.C. Batch effects in single-cell rna-sequencing data are corrected by matching mutual nearest neighbors. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018, 36, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, H.T.N.; Ang, K.S.; Chevrier, M.; Zhang, X.; Lee, N.Y.S.; Goh, M.; Chen, J. A benchmark of batch-effect correction methods for single-cell rna sequencing data. Genome Biol. 2020, 21, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chazarra-Gil, R.; van Dongen, S.; Kiselev, V.Y.; Hemberg, M. Flexible comparison of batch correction methods for single-cell rna-seq using batchbench. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, e42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korsunsky, I.; Millard, N.; Fan, J.; Slowikowski, K.; Zhang, F.; Wei, K.; Baglaenko, Y.; Brenner, M.; Loh, P.; Raychaudhuri, S. Fast, sensitive and accurate integration of single-cell data with harmony. Nat. Methods 2019, 16, 1289–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Tan, G.; Gou, C. Cascaded iterative transformer for jointly predicting facial landmark, occlusion probability and head pose. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2024, 132, 1242–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Tan, G. Id-nerf: Indirect diffusion-guided neural radiance fields for generalizable view synthesis. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 266, 126068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Dong, X.; Song, W.; Chong, Z.; Tang, Z.; Zhou, J.; Cheng, Y.; Chen, L.; Li, H.; Yan, Y.; et al. Consistentid: Portrait generation with multimodal fine-grained identity preserving. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.16771. [Google Scholar]

- Baltrušaitis, T.; Ahuja, C.; Morency, L.-P. Multimodal machine learning: A survey and taxonomy. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2018, 41, 423–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steyaert, S.; Pizurica, M.; Nagaraj, D.; Khandelwal, P.; Hernandez-Boussard, T.; Gentles, A.J.; Gevaert, O. Multimodal data fusion for cancer biomarker discovery with deep learning. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2023, 5, 351–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Xu, F.; Wei, L.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, J.; Wei, L.; Wei, D.-Q. Afp-mfl: Accurate identification of antifungal peptides using multi-view feature learning. Briefings Bioinform. 2023, 24, bbac606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Huang, F.; Xiong, Z.; Zhang, W. A multi-modal contrastive diffusion model for therapeutic peptide generation. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 20–27 February 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, X.; Zhang, J.; He, Y.; Zhang, X.; Lin, Z.; Partarrieu, S.; Hanna, E.B.; Ren, Z.; Shen, H.; Yang, Y.; et al. Explainable multi-task learning for multi-modality biological data analysis. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Z.; Chen, G.; Chen, S.; He, H.; Huang, J.; Dong, T.; Zhou, J.; Zhao, L.; You, L.; Chen, C.Y.-C. Modal-next: Toward unified heterogeneous cellular data integration. Inf. Fusion 2025, 125, 103479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Chen, G.; Chen, S.; Yao, J.; You, L.; Chen, C.Y.-C. Modal-nexus auto-encoder for multi-modality cellular data integration and imputation. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 9021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Z.; Wang, F.; Yang, F.; Song, J.; Chen, C.Y.-C.; Yao, J. scTransMIL bridges patient-level phenotypes and single-cell transcriptomics for cancer screening and heterogeneity inference. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trosten, D.J.; Lokse, S.; Jenssen, R.; Kampffmeyer, M. Reconsidering representation alignment for multi-view clustering. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 1255–1265. [Google Scholar]

- Kampffmeyer, M.; Løkse, S.; Bianchi, F.M.; Livi, L.; Salberg, A.-B.; Jenssen, R. Deep divergence-based approach to clustering. Neural Netw. 2019, 113, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zhao, B.; Song, X.; Lyu, C.; Chen, W.; Xiong, Y.; Wei, D.-Q. Subtype-dcc: Decoupled contrastive clustering method for cancer subtype identification based on multi-omics data. Briefings Bioinform. 2023, 24, bbad025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Li, O.; Tao, D.; Barnett, A.; Rudin, C.; Su, J.K. This looks like that: Deep learning for interpretable image recognition. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 32, Proceedings of the 33rd International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–14 December 2019; Neural Information Processing Systems Foundation, Inc. (NeurIPS): San Diego, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Z.; Yang, H.; Chen, C.Y.-C. Weakly supervised posture mining for fine-grained classification. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 23735–23744. [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.-I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30, Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; Neural Information Processing Systems Foundation, Inc. (NeurIPS): San Diego, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30, Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; Neural Information Processing Systems Foundation, Inc. (NeurIPS): San Diego, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hinton, G.; Vinyals, O.; Dean, J. Distilling the knowledge in a neural network. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1503.02531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luecken, M.D.; Burkhardt, D.B.; Cannoodt, R.; Lance, C.; Agrawal, A.; Aliee, H.; Chen, A.T.; Deconinck, L.; Detweiler, A.M.; Granados, A.A.; et al. A sandbox for prediction and integration of dna, rna, and proteins in single cells. In Proceedings of the 35th Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2021) Track on Datasets and Benchmarks, Online, 1 May–8 June 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Z.-J.; Gao, G. Multi-omics single-cell data integration and regulatory inference with graph-linked embedding. Nat. Biotechnol. 2022, 40, 1458–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Qin, S.; Si, W.; Wang, A.; Xing, B.; Gao, R.; Ren, X.; Wang, L.; Wu, X.; Zhang, J.; et al. Pan-cancer single-cell landscape of tumor-infiltrating t cells. Science 2021, 374, abe6474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maynard, K.R.; Collado-Torres, L.; Weber, L.M.; Uytingco, C.; Barry, B.K.; Williams, S.R.; Catallini, J.L.; Tran, M.N.; Besich, Z.; Tippani, M.; et al. Transcriptome-scale spatial gene expression in the human dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Nat. Neurosci. 2021, 24, 425–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Lake, B.B.; Zhang, K. High-throughput sequencing of the transcriptome and chromatin accessibility in the same cell. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 1452–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, S.; Zhang, B.; LaFave, L.M.; Earl, A.S.; Chiang, Z.; Hu, Y.; Ding, J.; Brack, A.; Kartha, V.K.; Tay, T.; et al. Chromatin potential identified by shared single-cell profiling of rna and chromatin. Cell 2020, 183, 1103–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muto, Y.; Wilson, P.C.; Ledru, N.; Wu, H.; Dimke, H.; Waikar, S.S.; Humphreys, B.D. Single cell transcriptional and chromatin accessibility profiling redefine cellular heterogeneity in the adult human kidney. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Z.; Huang, J.; Chen, G.; Chen, C.Y.-C. Comprehensive view embedding learning for single-cell multimodal integration. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 20–27 February 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Conde, C.D.; Xu, C.; Jarvis, L.B.; Rainbow, D.B.; Wells, S.B.; Gomes, T.; Howlett, S.K.; Suchanek, O.; Polanski, K.; King, H.W.; et al. Cross-tissue immune cell analysis reveals tissue-specific features in humans. Science 2022, 376, eabl5197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, F.; Pellegrini, M. Actinn: Automated identification of cell types in single cell rna sequencing. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, 533–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xiang, G.; Jiang, A.Y.; Lynch, A.; Zeng, Z.; Wang, C.; Zhang, W.; Fan, J.; Kang, J.; Gu, S.S.; et al. Metatime integrates single-cell gene expression to characterize the meta-components of the tumor immune microenvironment. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 2634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoris, C.V.; Xiao, L.; Chopra, A.; Chaffin, M.D.; Sayed, Z.R.A.; Hill, M.C.; Mantineo, H.; Brydon, E.M.; Zeng, Z.; Liu, X.S.; et al. Transfer learning enables predictions in network biology. Nature 2023, 618, 616–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Zhang, J.; Nie, Z. Large-scale cell representation learning via divide-and-conquer contrastive learning. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.04371. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, S.; Zhang, J.; Luo, Y.; Wu, Y.; Nie, Z. Langcell: Language-cell pre-training for cell identity understanding. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.06708. [Google Scholar]

- Welch, J.D.; Kozareva, V.; Ferreira, A.; Vanderburg, C.; Martin, C.; Macosko, E.Z. Single-cell multi-omic integration compares and contrasts features of brain cell identity. Cell 2019, 177, 1873–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, J.; Liang, S.; Mohanty, V.; Miao, Q.; Huang, Y.; Liang, Q.; Cheng, X.; Kim, S.; Choi, J.; Li, Y.; et al. Bi-order multimodal integration of single-cell data. Genome Biol. 2022, 23, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Liu, J.; Kriebel, A.R.; Preissl, S.; Luo, C.; Castanon, R.; Sandoval, J.; Rivkin, A.; Nery, J.R.; Behrens, M.M.; et al. Iterative single-cell multi-omic integration using online learning. Nat. Biotechnol. 2021, 39, 1000–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, K.; Bai, X.; Hong, Y.; Wan, L. Unsupervised topological alignment for single-cell multi-omics integration. Bioinformatics 2020, 36, i48–i56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Zhao, X.; Tang, S.; Jiang, Q.; Li, S.; Li, S.; Chen, S. scButterfly: A versatile single-cell cross-modality translation method via dual-aligned variational autoencoders. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 2973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| DatasetName | Task | Cell Counts | Type Counts | Batch Counts | Modality | Organ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMMC | annotation | 69,249 | 22 | 13 | RNA | HomoBMMC |

| PBMC | annotation | 9058 | 19 | 2 | RNA | HomoPBMC |

| Pan-cancer | annotation | 71,113 | 23 | 13 | RNA | HomoCancers |

| DLPFC | annotation | 47,329 | 7 | 12 | Spatial RNA | HomoCortex |

| 10x-Multiome | integration | 9631 × 2 | 19 | N/A | RNA + ATAC | HomoPBMC |

| Chen-2019 [48] | integration | 9190 × 2 | 22 | N/A | RNA + ATAC | MouseCortex |

| Ma-2020 [49] | integration | 32,231 | 22 | 4 | RNA + ATAC | MouseSkin |

| Muto-2021 [50] | integration | 44,190 | 13 | 5 | RNA + ATAC | HomoKidney |

| BMMC | PBMC | DLPFC | Pan-Cancer | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Method | Acc | F1 | Acc | F1 | Acc | F1 | Acc | F1 |

| Seurat | 0.714 | 0.528 | 0.688 | 0.605 | 0.646 | 0.630 | 0.758 | 0.737 |

| ACTINN | 0.826 | 0.803 | 0.874 | 0.800 | 0.729 | 0.704 | 0.787 | 0.760 |

| CellTypist | 0.866 | 0.852 | 0.931 | 0.930 | 0.787 | 0.702 | 0.712 | 0.649 |

| TOSICA | 0.912 | 0.902 | 0.958 | 0.935 | 0.939 | 0.931 | 0.885 | 0.863 |

| Cellcano | 0.877 | 0.826 | 0.958 | 0.955 | 0.838 | 0.761 | 0.748 | 0.716 |

| MetaTiME | 0.910 | 0.913 | 0.870 | 0.855 | 0.738 | 0.731 | 0.869 | 0.842 |

| Geneformer | 0.931 | 0.897 | 0.968 | 0.966 | 0.947 | 0.927 | 0.856 | 0.846 |

| scBERT | 0.906 | 0.885 | 0.979 | 0.978 | 0.930 | 0.897 | 0.870 | 0.832 |

| CellLM | 0.922 | 0.896 | 0.966 | 0.963 | 0.934 | 0.930 | 0.836 | 0.821 |

| LangCell | 0.930 | 0.896 | 0.980 | 0.958 | 0.949 | 0.932 | 0.874 | 0.834 |

| scGPT | 0.925 | 0.897 | 0.945 | 0.951 | 0.953 | 0.927 | 0.866 | 0.849 |

| KIDA | 0.931 | 0.902 | 0.980 | 0.972 | 0.953 | 0.947 | 0.891 | 0.866 |

| Ours | 0.944 | 0.921 | 0.971 | 0.963 | 0.961 | 0.955 | 0.916 | 0.902 |

| Dataset | Method | kBET | ASW (Cell Type) |

|---|---|---|---|

| BMMC | PCA | 0.32 | 0.28 |

| PLKD | 0.89 | 0.81 | |

| Pan-cancer | PCA | 0.15 | 0.35 |

| PLKD | 0.78 | 0.64 |

| Ma2020 (RNA) | Ma2020 (ATAC) | Muto2021 (RNA) | Muto2021 (ATAC) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [49] | [49] | [50] | [50] | |||||

| Method | Acc | F1 | Acc | F1 | Acc | F1 | Acc | F1 |

| Seurat | 0.912 | 0.905 | 0.701 | 0.700 | 0.748 | 0.739 | 0.869 | 0.864 |

| Actinn | 0.854 | 0.839 | 0.791 | 0.777 | 0.812 | 0.799 | 0.760 | 0.752 |

| CellTypist | 0.697 | 0.643 | 0.668 | 0.612 | 0.755 | 0.714 | 0.723 | 0.701 |

| Tosica | 0.915 | 0.903 | 0.905 | 0.905 | 0.874 | 0.869 | 0.821 | 0.819 |

| Cellcano | 0.864 | 0.853 | 0.946 | 0.940 | 0.855 | 0.841 | 0.922 | 0.921 |

| MetaTiME | 0.645 | 0.613 | 0.601 | 0.601 | 0.656 | 0.649 | 0.603 | 0.602 |

| Geneformer | 0.929 | 0.916 | 0.906 | 0.897 | 0.888 | 0.861 | 0.882 | 0.871 |

| scBERT | 0.933 | 0.928 | 0.922 | 0.920 | 0.894 | 0.890 | 0.868 | 0.867 |

| CellLM | 0.941 | 0.917 | 0.909 | 0.883 | 0.908 | 0.853 | 0.877 | 0.841 |

| LangCell | 0.948 | 0.922 | 0.916 | 0.896 | 0.921 | 0.898 | 0.842 | 0.829 |

| scGPT | 0.940 | 0.926 | 0.914 | 0.909 | 0.901 | 0.894 | 0.879 | 0.862 |

| KIDA | 0.949 | 0.932 | 0.951 | 0.944 | 0.925 | 0.917 | 0.923 | 0.914 |

| Ours | 0.951 | 0.939 | 0.956 | 0.952 | 0.938 | 0.922 | 0.936 | 0.921 |

| Loss | Mask | Noise | Acc (T) | ARI (T) | Acc (S) | ARI (S) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ✓ | ✓ | 0 | 0.974 | 0.935 | 0.981 | 0.966 |

| × | ✓ | 0 | 0.905 | 0.526 | 0.897 | 0.405 |

| ✓ | × | 0 | 0.962 | 0.928 | 0.969 | 0.914 |

| ✓ | ✓ | 0.1 | 0.942 | 0.908 | 0.944 | 0.906 |

| ✓ | ✓ | 0.15 | 0.892 | 0.868 | 0.901 | 0.831 |

| ✓ | ✓ | 0.2 | 0.868 | 0.768 | 0.862 | 0.795 |

| Group | Cell Count Range | F1-Score | Recall | Precision |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | >5000 | 0.831 | 0.774 | 0.982 |

| Medium | 1000–5000 | 0.888 | 0.997 | 0.824 |

| Low | <1000 | 0.848 | 1.000 | 0.771 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, M.; Ren, B.; Li, X. Pattern Learning and Knowledge Distillation for Single-Cell Data Annotation. Biology 2026, 15, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010002

Zhang M, Ren B, Li X. Pattern Learning and Knowledge Distillation for Single-Cell Data Annotation. Biology. 2026; 15(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Ming, Boran Ren, and Xuedong Li. 2026. "Pattern Learning and Knowledge Distillation for Single-Cell Data Annotation" Biology 15, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010002

APA StyleZhang, M., Ren, B., & Li, X. (2026). Pattern Learning and Knowledge Distillation for Single-Cell Data Annotation. Biology, 15(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology15010002