Abstract

The extensive application of carbon fibers (CFs) and their composites in aerospace and electronics has established the optimization of their electrical conductivity as a critical research priority. Conventional electrodeposition techniques are limited by CF inherent chemical inertness and low surface energy, which increase the energy barrier for copper deposition, leading to defective coatings and weakened interfacial bonding. This study demonstrated that sodium hypophosphite (NaH2PO2) enhances CF copper deposition efficiency through concentration gradient experiments (0–30 g/L), revealing its modulation of deposition kinetics, crystallographic evolution, and interfacial adhesion strength. Electrochemical analysis showed that NaH2PO2 accelerates initial copper nucleation by reducing activation energy without forming complexes. Increasing its concentration expanded monofilament diameter from 8.55 to 9.26 μm post-deposition, with copper loading rising 28.89%. XRD analysis identified 20 g/L as the optimum for crystallinity, producing maximal grain size (8.27 nm) and predominant (111) orientation. This structure achieved a conductivity of 1.63 × 103 S·cm−1 (55.24% enhancement) and improved breaking force from 13.54 to 14.57 cN. Adhesion tests showed that the 20 g/L group maintained stability comparable to the control. These results suggest that 20 g/L is the preferred concentration balancing conductivity enhancement with mechanical stability. This approach offers a novel strategy for fabricating highly conductive CF composites.

1. Introduction

Electronic devices have become ubiquitous in modern technologies, ranging from construction and smart home systems to transportation and communication infrastructure, where conductive materials play critical roles. Copper remains widely recognized as the predominant conductive material, owing to its superior electrical and thermal conductivity coupled with substantial geological abundance [1,2,3]. The growing emphasis on lightweight design and multifunctional integration in aerospace [4], automotive [5], and new-energy transportation [6] sectors has led to stringent technical requirements for conductive materials to simultaneously exhibit enhanced mechanical performance and lightweight characteristics [7,8]. However, the inherent high density and limited mechanical strength of copper have significantly constrained its deployment in advanced engineering applications. Therefore, developing high-performance conductive alternatives to traditional copper-based materials has become a crucial research priority in materials science [9].

Carbon fibers (CFs) have emerged as a promising next-generation conductive material owing to its exceptional specific strength, outstanding specific modulus, combined thermal and electrical conductivity, and low density [10,11,12,13,14,15]. Nonetheless, CFs exhibit markedly inferior electrical conductivity relative to metallic materials, along with low surface energy and poor interfacial compatibility. Surface metallization has proven to be an effective strategy for improving interfacial performance and enhancing the electrical conductivity of CFs [16,17,18,19,20]. Mainstream CF metallization techniques encompass electroplating [21], electroless plating [22], molten salt deposition [23], and vapor-phase deposition [24]. Electroplating demonstrates distinct advantages for industrial-scale production, including cost efficiency, simplified processing, rapid deposition rates, and high production efficiency. Among common coating metals, copper demonstrates superior modification efficacy on CF surfaces. The resulting copper-plated CFs (CF-Cu) exhibit remarkable enhancements in both electrical and thermal transport properties. For instance, Xu et al. [25] successfully engineered a three-dimensional interconnected copper network structure using CF felt as the scaffold through electrodeposition technology, subsequently impregnated with epoxy resin to fabricate composite materials. Their results revealed a positive correlation between electrical conductivity and copper volume fraction, achieving 2.60 × 103 S·cm−1 at 3.59 vol% copper content—an 11-order-of-magnitude enhancement compared to non-metallized counterparts. When copper content increased to 31.72 vol%, conductivity increased to 7.49 × 104 S‧cm−1. Notably, post-metallization thermal conductivity reached 30.69 W·m−1·K−1, representing a 140-fold enhancement relative to pure epoxy resin. Yi et al. [26] investigated the Wiedemann–Franz law in CF-Cu systems, revealing that these composites synergistically integrate metallic electrical conduction with insulating matrix-derived thermal transport mechanisms. The Lorentz coefficient displayed thickness- and temperature-dependent deviations from theoretical values (2.44 × 10−8 W·Ω·K−2). Thermal transport dominance exhibited temperature-dependent transitions: copper layers prevailed below 300 K, whereas CFs became primary heat conductive pathways near 300 K. Electrical conduction remained copper-dominated throughout the tested temperature range.

However, copper’s high reduction potential confers marked sensitivity to the current density [27]. During electrodeposition, CF bundles consistently exhibit dark-core defects characterized by incomplete metallization of CFs, combined with suboptimal coating quality, thereby significantly restricting the engineering applicability of CF-Cu composites. Interface modification strategies, such as pre-deposited metallic interlayers, effectively mitigate these defects. Tran et al. [9] demonstrated that sequential magnetron-sputtered gold interlayer deposition followed by copper electroplating yields CF/Au/Cu composite wires with uniform metal distribution. The resulting composite demonstrated a conductivity of 4.40 × 105 S·cm−1 (75% of pure copper), tensile strength of 3.27 GPa (approximately an order of magnitude higher than copper), and substantially reduced density, showcasing superior performance metrics for replacing conventional metallic conductors. Han et al. [28] engineered Ni-Cu graded coatings on high-modulus CFs via sequential electroplating. Post-nickel deposition resistivity was measured at 9.94 × 10−5 Ω·cm, decreasing to 5.80 × 10−5 Ω·cm after copper deposition, achieving 90.35% and 94.37% reductions compared to pristine CFs. Moreover, post-deposition heat treatment has been recognized as an effective quality optimization technique. Zhang et al. [29] systematically investigated the effects of annealing temperature on CF-Cu’s electrical and mechanical performance. Peak performance was achieved at 600 °C: conductivity increased to 8.42 × 104 S·cm−1 (78-fold enhancement compared to non-annealed samples), with tensile strength and modulus reaching 2.98 GPa and 147.22 GPa, respectively, corresponding to 39% and 19% improvements over the control group.

In strategies to control copper electrodeposition on carbon materials, the introduction of reducing agents into plating baths also remains a principal approach. Sodium hypophosphite (NaH2PO2) exhibits promising potential in related applications due to its cost-effectiveness, safety profile, and chemical stability [30]. Chu et al. [31] successfully prepared copper-coated graphite powder by modifying the plating bath with NaH2PO2. Their study demonstrated that the additive promotes copper nucleation on graphite surfaces, significantly accelerating initial deposition stage and achieving maximum copper encapsulation (approximately 70%) at 10–15 g/L. However, the application of NaH2PO2 in copper deposition on CF surfaces remains underexplored. This work undertakes a systematic investigation of NaH2PO2 concentration effects on both plating bath characteristics and CF-Cu composite performance. Electrochemical analysis elucidated the mechanistic functions of NaH2PO2, combined with SEM characterization of copper growth morphologies on CF surfaces, providing experimental validation for advancing its applications in CF surface electrodeposition.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The cathode employed 12 K polyacrylonitrile-based CF (monofilament diameter ~7 μm) supplied by TaiWan Plastics Corporation. A phosphor bronze sheet (P content: 0.30 ± 0.05%) served as the anode to minimize interference from electrolyte variations. The plating solution was composed of analytical-grade chemicals: copper(II) sulfate pentahydrate (CuSO4·5H2O, Tianjin Yongda Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., Tianjin, China), trisodium citrate dihydrate (Na3Cit, Na3C6H5O7·2H2O, Xilong Scientific Co., Ltd., Guangzhou, China), potassium sodium tartrate tetrahydrate (KNaT, NaKC4H4O6·4H2O, Tianjin Kermel Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., Tianjin, China), sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS, CH3(CH2)11OSO3Na, Tianjin North Union Fine Chemicals Development Co., Ltd., Tianjin, China), and sodium hypophosphite monohydrate (NaH2PO2·H2O, Tianjin Beichen Fangzheng Reagent Factory, Tianjin, China). The electrolyte temperature and pH were maintained at 40 ± 0.5 °C and 4.60 ± 0.05, respectively. All solutions were prepared with deionized water. Detailed electrolyte formulations are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Composition and concentration of electroplating solution for CF-Cu sample preparation.

2.2. Preparation of CF-Cu

In the pre-treatment phase, CFs underwent thermal oxidation at 450 °C under atmospheric conditions for 30 min to eliminate residual slurry and induce surface roughening, producing roughened CFs (denoted as r-CF). For electroplating, both the r-CF cathode and phosphor-copper anode were positioned in the electrolytic bath. The electrodeposition was conducted under controlled conditions: a constant temperature of 40 °C and an applied voltage of 5 V were maintained for 10 min. Post-processing involved sequential rinsing with deionized water until no residual copper particles were observed, followed by a vacuum drying step at 45 °C for 4 h. The specimen nomenclature (CF-Cu-0 to CF-Cu-30) corresponds to NaH2PO2 concentrations from 0 to 30 g/L.

2.3. Electrochemical Testing

All measurements were performed using a CHI760e electrochemical workstation (Shanghai Chenhua Instrument Co., Ltd., Shanghai China) with a conventional three-electrode system. A platinum sheet electrode (1 × 1 cm2) served as the counter electrode, and a saturated calomel electrode (SCE, 0.2412 V vs. standard hydrogen electrode, SHE) was used as the reference electrode. All measurements were performed in triplicate to validate reproducibility.

- Cathodic polarization curve measurement

In the actual plating bath (Table 1), r-CFs functioned as the working electrode, with their immersion depth controlled at 1.5 cm. Cathodic polarization profiles were acquired via dynamic scanning at 10 mV s−1 over the potential window of −1.2 V to 0.5 V (vs. SCE) [31].

- 2.

- Cyclic voltammetry (CV) test

The electrolyte compositions for testing are detailed in Table 2. A glassy carbon (GC) electrode served as the working electrode, with a defined potential window of −2.5 V to 2.5 V (vs. SCE) and a scan rate of 20 mV·s−1 [32,33]. Prior to each electrochemical measurement, the working electrode surface was polished using 0.05 μm alumina slurry and thoroughly rinsed to ensure the surface is flat and smooth.

Table 2.

Composition of cyclic voltammetry test solution (NaH2PO2·H2O concentration: 20 g/L; other chemicals are the same as in Table 1).

2.4. Current Efficiency Test

Current efficiency is a critical parameter for evaluating the performance of electroplating solutions. In this study, copper coulometry was employed to quantify the electrodeposition current efficiency. The coulometric electrolyte was formulated with 125 g/L CuSO4·5H2O, 25 mL/L concentrated sulfuric acid (98%) and 50 mL/L anhydrous ethanol. A three-electrode coulometer configuration—with two copper plates as anodes and one as the cathode—was assembled and connected in series with the electrolytic cell. The electrodeposition parameters were controlled as follows: a current density of 0.20 A·dm−2, a temperature maintained at 25 °C using a thermostatic bath, and a deposition time of 10 min. The current efficiency η was calculated as , where and denote the mass of deposited elemental copper in the test solution and coulometer, respectively. This approach eliminates the need for standard electrochemical equivalents, as both systems primarily consist of copper electrodeposition.

2.5. Coating Adhesion Test

The adhesion integrity of copper coatings is a critical determinant of material reliability, as delamination is a primary failure mode in many applications. To assess this key property, this study systematically evaluated coating adhesion using thermal shock and ultrasonic treatment methodologies. The mass loss rate () for both methods was calculated using the equation: , where represents the post-electroplating mass, and denotes the stabilized post-treatment mass. Thermal shock testing was performed in compliance with ASTM B571-23 standard protocols [34]. Specimens were maintained in an SRJX-4-13A muffle furnace (Shaoxing Shangyu Daoxu Kexi Instrument Plant, Shaoxing, China) at 250 °C for 30 min, then immediately immersed in an ice-water bath for 5 min. This thermal cycle was repeated five times. Specimens were collected after the 1st, 3rd, and 5th cycles. Parallel ultrasonic processing was performed using a DY-020 ultrasonic machine (Shenzhen Juli Environmental Protection Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China), with specimens systematically sampled at 10 min intervals throughout the 40 min exposure. All specimens underwent sequential post-treatment: deionized water rinsing, vacuum desiccation, and gravimetric treatment.

2.6. Characterization

Surface morphology was characterized using a Hitachi S-3500 tungsten-filament scanning electron microscope (SEM, Tokyo, Japan). Prior to observation, samples were sputter-coated with gold. The surface tension of the plating solution was measured in quintuplicate using a JWY-200B tensiometer (Chengde Youte Testing Instrument Manufacturing Co., Ltd., Chengde, China). Filament diameters were measured using a Keyence VK-X1000 confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM, Osaka, Japan). Triplicate measurements along the axis of each filament were averaged to obtain the representative diameter. X-ray diffraction (XRD, Tokyo, Japan) analysis was performed on a Rigaku Ultima IV diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 0.15406 nm). Continuous scans were performed over a 2θ range of 20–80° with a step size of 0.02° and a scan rate of 6°/min [29]. The electrical resistivity of individual filaments was measured using the four-point probe technique with an ST2258C meter (Suzhou Jingge Electronics Co., Ltd., Suzhou, China), and ten independent specimens were analyzed to obtain the statistical mean. Tensile testing of single fiber filaments was conducted using an XQ-1A tensile tester (Shanghai New Fiber Instrument Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Effect of NaH2PO2 on Copper Deposition on CF Surface

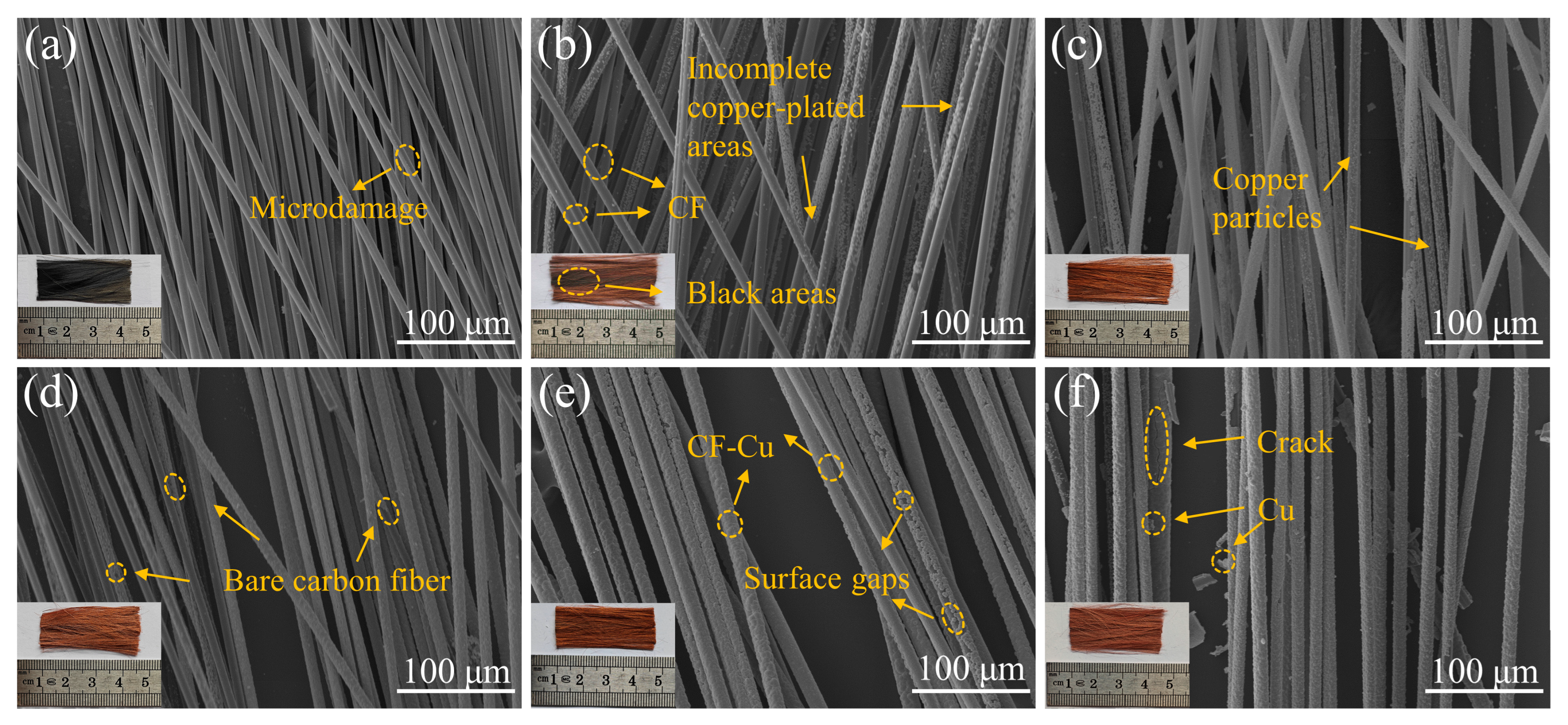

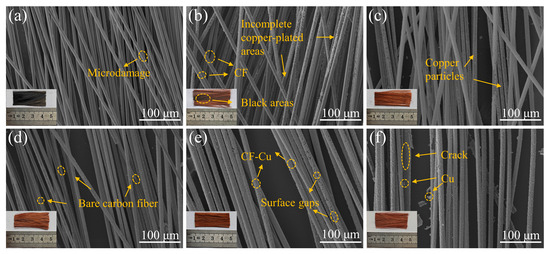

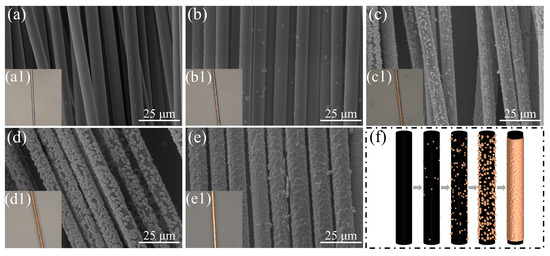

Incomplete copper deposition predominantly occurs within the core regions of CF bundles during electroplating [35]. Confocal micrographs in the inset of Figure 1 reveal distinct dark regions matching uncoated CF cores in specimens prepared without NaH2PO2, with such darkening mitigated upon introduction of this additive. As shown in Figure 1, SEM analysis was performed to systematically characterize the morphological evolution of CFs subjected to graded NaH2PO2 concentrations. Figure 1a presents the surface morphology of pretreated CFs, revealing an absence of structural defects, which confirms that the oxidative pretreatment preserved CF integrity while retaining their original mechanical performance characteristics [36]. Figure 1b–f shows a progressive morphological transition at the core regions of fiber bundles, corresponding to increasing NaH2PO2 concentrations, with improved copper deposition integrity and decreasing fractions of uncoated fibers as the reagent concentration increases. In the low-concentration regime (0–5 g/L, Figure 1b,c), copper nucleation appeared as discrete particulate deposits on fiber surfaces, failing to form continuous metallic coatings. In the transition regime (10–20 g/L, Figure 1d,e), incomplete copper coverage persisted, with localized coating discontinuities exposing the underlying CF substrates. At high concentrations (30 g/L, Figure 1f), although complete copper encapsulation was attained, residual particulate depositions persisted near the CF-Cu interface. Subsequent sedimentation analysis of electroplating baths revealed substantial accumulation of copper particulates, particularly pronounced in electrolytes with high NaH2PO2 concentrations. This observation implies the presence of residual metallic particulates in the electrolyte phase, which may trigger spontaneous agglomeration cascades that compromise bath stability.

Figure 1.

Core region morphologies of CF-Cu under different concentrations of NaH2PO2: (a) r-CF; (b) CF-Cu-0; (c) CF-Cu-5; (d) CF-Cu-10; (e) CF-Cu-20; (f) CF-Cu-30. The illustrations are actual photographs of the samples.

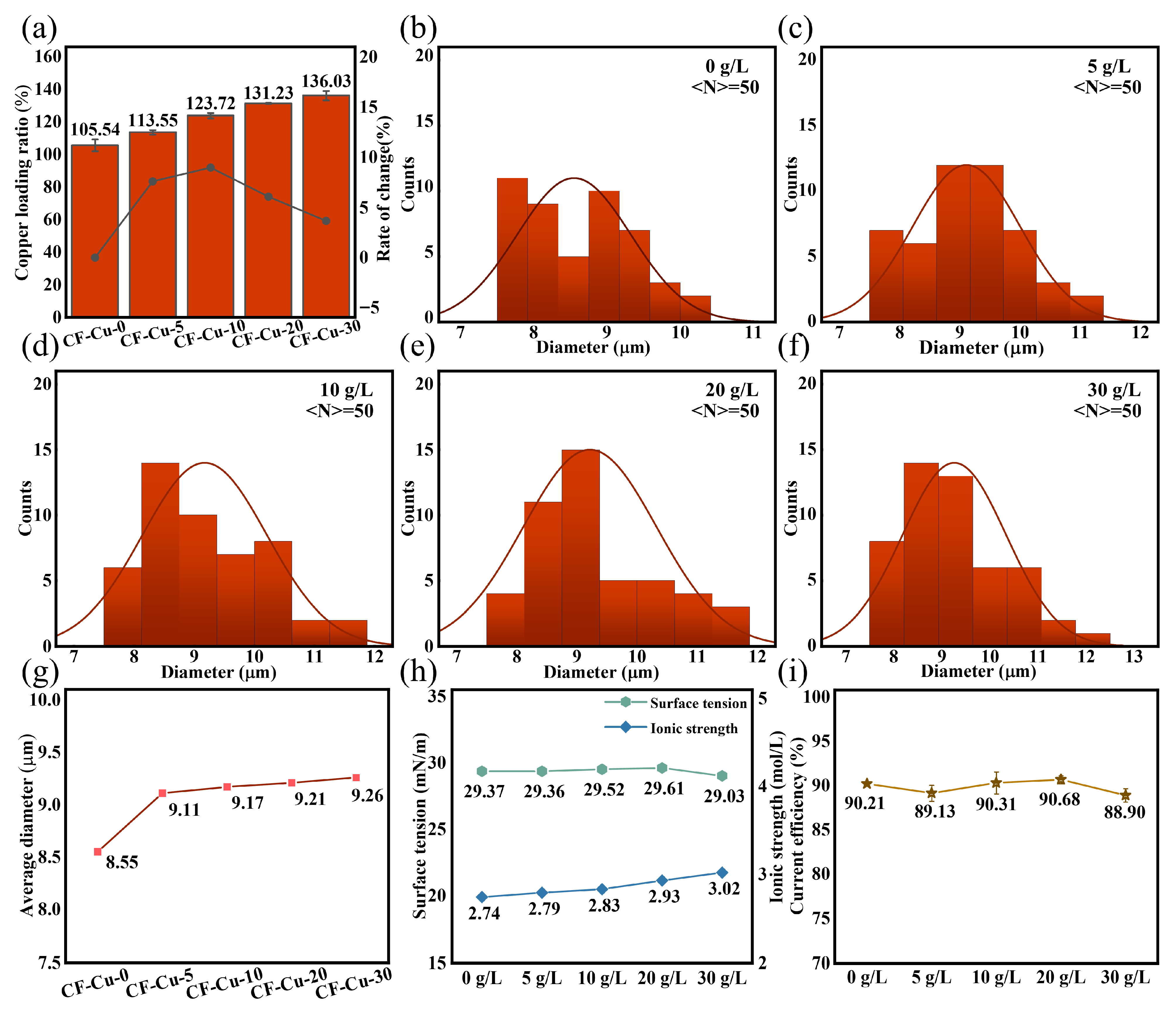

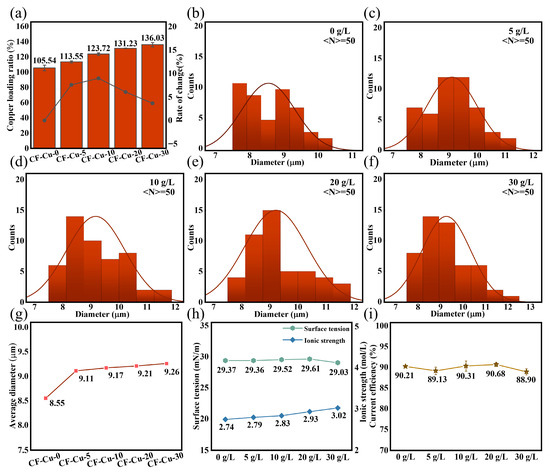

Numerical analysis of copper loading ratio, defined as , where and represent the pre- and post-electroplating masses of CF, was conducted using gravimetric measurements. The copper mass fraction exhibited a significant concentration-dependent increase from 105.54% to 136.03% as the NaH2PO2 concentration increased from 0 to 30 g/L (Figure 2a). Notably, incremental growth rates progressively decreased from 17.23% (0–10 g/L interval) to 3.66% (20–30 g/L interval), indicating reduced loading efficiency at concentrations ≥ 20 g/L, consistent with a surface deposition threshold. Statistical analysis of CLSM-measured monofilament diameters (50 pieces per sample, randomly selected) demonstrated that NaH2PO2 enhanced copper deposition at bundle cores and promoted peripheral fiber coating. Quantitative analysis integrating diameter distributions (Figure 2b–f) and concentration-dependent trends in mean diameters (Figure 2g) revealed that stepwise increases in the NaH2PO2 concentration caused a sustained shift in the dominance of large-diameter CF-Cu (≥10 μm) from the [10,11) range to the [12,13) μm range, with an increase in the mean diameter of the sample from 8.55 to 9.26 μm. Small-diameter CF-Cu (≤9 μm) maintained stable size distributions in the 7–9 μm range across all tested concentrations. These findings demonstrate compensatory deposition mechanisms at bundle cores, consistent with the morphological evolution shown in Figure 1. Comparative analysis of Figure 2a,g demonstrates that copper loading and CF-Cu diameter showed marked increases at low to moderate NaH2PO2 concentrations (0–20 g/L), reaching a plateau at higher concentrations (20–30 g/L).

Figure 2.

Basic parameters of CF-Cu and plating solution under different concentrations of NaH2PO2: (a) variation of copper loading; (b–f) diameter distribution; (g) variation in average diameter; (h) surface tension and ionic strength; (i) current efficiency.

In electrochemical deposition systems, surface tension and cathodic current efficiency are critical parameters for evaluating plating solution performance. Surface tension describes interfacial wettability at the substrate surface, whereas cathodic current efficiency, rooted in Faraday’s laws, quantifies energy dissipation caused by hydrogen evolution side reactions [37]. Figure 2h illustrates slight surface tension variation (29.37 ± 0.34 mN/m) across the NaH2PO2 concentration gradient (0–30 g/L). The concomitant increase in ionic strength (2.74 to 3.02 mol/L) results from complete dissociation of NaH2PO2 into Na+ and H2PO2−. The weak amphiphilicity of H2PO2− induces negligible surfactant activity. These results confirm that NaH2PO2 does not affect cathodic wettability through surface tension modification. Quantitative analysis via copper coulombmeter (Figure 2i) demonstrates selective regulation of hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) and copper deposition processes. Cathodic current efficiency remained stable (89.85% ± 0.70%) regardless of additive concentration at 0.2 A/dm2, indicating that the promotion of HER was weaker than the enhancement of copper deposition. This low energy dissipation characteristic endows NaH2PO2 with significant application value in optimizing CF plating bath systems.

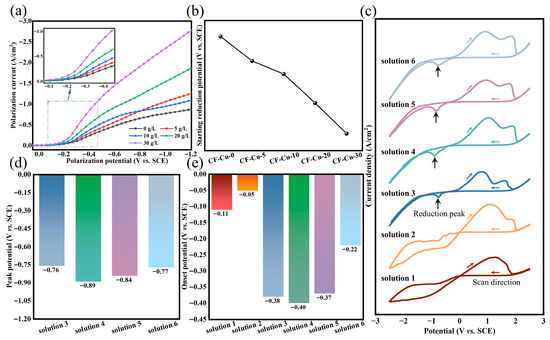

To clarify the mechanistic role of NaH2PO2 in copper deposition onto CF surfaces, electrochemical measurements were performed under simulated electroplating experimental conditions. Using r-CFs as the working electrode, cathodic polarization measurements were systematically conducted in electroplating baths with varying concentrations of NaH2PO2. As shown in Figure 3a, the cathodic polarization curves exhibit positive potential shifts with increasing NaH2PO2 concentrations. This potential shift indicates improved copper ion deposition efficiency. Tangential extrapolation was used to determine the onset reduction potentials of Cu2+ in different electrolytes. As evidenced in Figure 3b, the onset reduction potentials decrease with increasing NaH2PO2 concentration. This finding suggests that NaH2PO2 facilitates cathodic electron transfer, thereby reducing the activation energy barrier for Cu2+ reduction [31]. Under the same external conditions, this results in a significant increase in the rate of Cu2+ reduction, consistent with the morphological evolution of copper deposits on CF surfaces shown in Figure 1b–f.

Figure 3.

Plating solutions with different concentrations of NaH2PO2: (a) cathodic polarization curves; (b) initial reduction potential of copper and plating solutions with different components; (c) cyclic voltammetry curves; (d) reduction peak potential; (e) onset potential.

A GC electrode was employed as the cathode in a component-decoupling experimental design. CV curves were analyzed to elucidate the synergistic interactions between electrolyte components and to systematically investigate their effects on copper reduction deposition kinetics [38]. As shown in Figure 3c, the CV profiles exhibited marked disparities among different components, confirming the specific regulatory effects of additives on the deposition process. The CV characteristics of Solution 1 (CuSO4 only) and Solution 2 (CuSO4 + NaH2PO2) are highly similar. Both systems exhibit a characteristic curve crossing. In the cathodic region, neither shows a distinct reduction peak, and the current density on the reverse (anodic) scan exceeds that of the forward (cathodic) scan. This indicates that the reaction kinetics are governed by the nucleation and growth of copper on the electrode surface rather than by mass transport limitations [39,40]. These similarities confirm that copper exists as free ions in both systems and that sodium hypophosphite does not form complexes with copper. In contrast, the introduction of the complexing agent Na3Cit (Solution 3) causes a characteristic reduction peak to appear. This demonstrates that Na3Cit alters the copper speciation: copper ions are bound in complexes rather than existing as free ions. Consequently, the reduction reaction becomes restricted by the diffusion of these complexed species to the cathode, effectively regulating the deposition process. Upon addition of KNaT as an auxiliary complexing agent (Solution 4), the reduction peak underwent broadening. Electrochemical analysis (Figure 3d) revealed a negative shift in peak potential (EP, −0.13 V), indicative of elevated activation energy requirements and kinetically limited copper deposition processes. Notably, the leveling effect of Na3Cit was significantly enhanced under co-complexation conditions, with synergistic coordination between Na3Cit and KNaT improving coating densification and deposition uniformity. However, this combination complicated copper deposition on CF bundle cores during electroplating. Incorporation of SDS surfactant (Solution 5) showed negligible influence on CV profiles. Its primary functions include lowering interfacial tension, enhancing electrolyte wettability, and facilitating hydrogen evolution reactions. The introduction of NaH2PO2 (Solution 6) induced a positive EP shift ( 0.07 V), confirming its role in promoting copper deposition. The coordinated regulatory effects of complexing agent remained effective, achieving simultaneous optimization of CF bundle core deposition kinetics and coating structural integrity.

The onset reduction potential (EO) serves as a reliable metric for the minimum overpotential required to initiate reduction processes in the electrochemical system. Tangent line analysis of Figure 3c quantitatively determined EO values for different electrolyte formulations, as shown in Figure 3e. Solutions 1 and 2 demonstrated substantial potential differences ( 0.11 V) relative to other groups, confirming their alignment with the direct Cu2+ reduction mechanism, consistent with previous analyses. The lower EO of Solution 2 (−0.11 V vs. −0.05 V) verifies the reductive activation capability of NaH2PO2. However, the limited potential difference ( 0.06 V) between the two solutions suggests the absence of stable coordination complexes between NaH2PO2 and copper ions under experimental conditions. In complexant-modified systems (Solutions 3–4), pronounced cathodic shifts ( 0.26 V) in EO revealed enhanced activation energy requirements for copper deposition from complexed species. SDS incorporation (Solution 5) induced a modest anodic shift ( 0.03 V), while NaH2PO2 addition (Solution 6) produced a marked anodic shift ( 0.15 V). This potential modulation confirms that NaH2PO2 enhances Cu2+/Cu0 electrochemical conversion efficiency through reduction in activation energy barriers, consistent with the proposed mechanism.

Distinct variations were observed in the anodic potential region. The shoulder feature of Solution 1’s anodic peak indicates sequential single-electron transfer (Cu0 ⟶ Cu+ ⟶ Cu2+), excluding direct bivalent oxidation [33]. Solutions 2–6 exhibited distinct peak splitting. Single-component CV tests showed negligible reduction features in the cathodic region (−1.0 to −0.4 V) compared with mixed electrolytes, accompanied by weak oxidative responses in the 1.2–2.2 V range (Figure S1a). Magnified current traces (Figure S1b) demonstrated that SDS induced no discernible response, Na3Cit caused minor cathodic shift (current density change, 0.00150 A·cm−2), and KNaT and NaH2PO2 generated weak reduction peaks. These currents were two orders of magnitude lower than those in mixed systems, confirming copper electrodeposition as the predominant reduction pathway. In the 1.2–2.2 V range, two well-defined oxidation peaks emerged: hypophosphite oxidation at 1.56 V ( 0.00243 A·cm−2) and citrate ligand oxidation at 1.79 V ( 0.00472 A·cm−2) (Figure S1c). Both peak potentials exceeded Solution 1’s copper oxidation potential ( 1.25 V) by 0.31 V (NaH2PO2) and 0.54 V (Na3Cit), respectively. This potential overlap with copper’s shoulder region (1.45–1.70 V) creates superimposed voltammetric signatures through additive current contributions from ligand oxidation and copper oxidation, explaining the anodic peak splitting in Figure 3c. Other components exhibited minimal interference, with KNaT inducing slight curve elevation during positive scanning ( 0.00100 A·cm−2), while SDS showed no detectable Faradaic response.

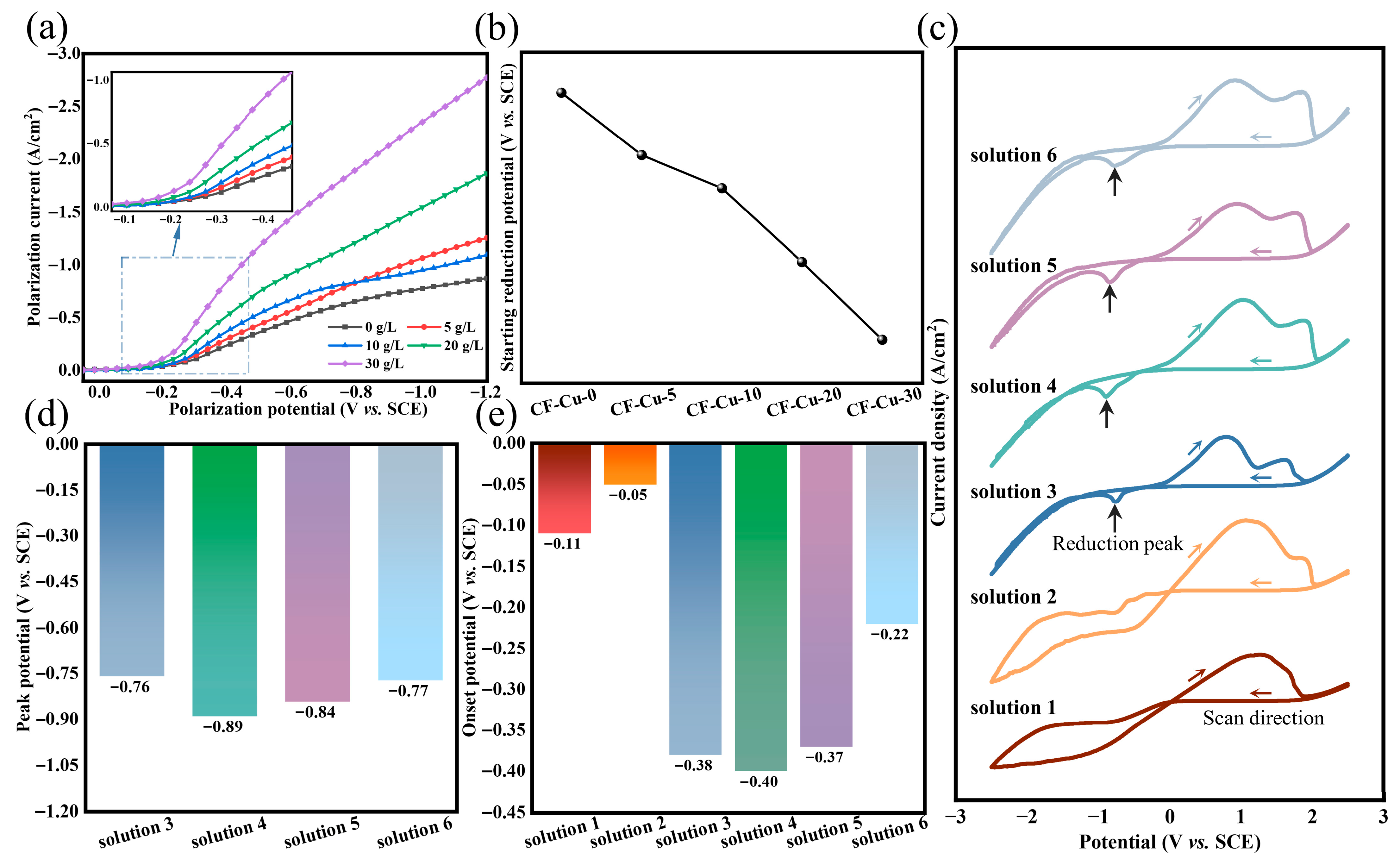

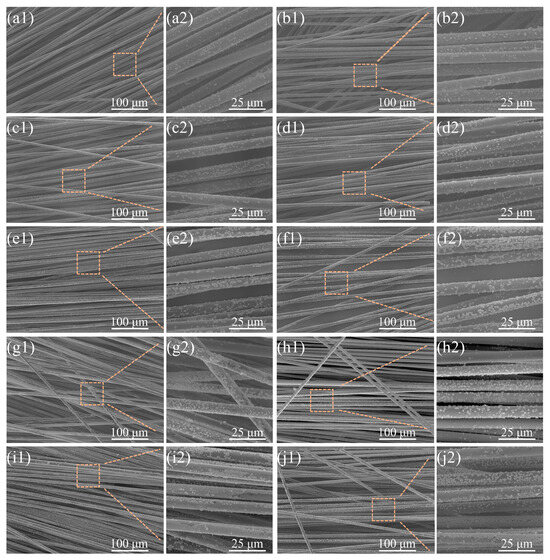

To further elucidate the mechanistic role of NaH2PO2, a two-factor experimental design was implemented under controlled process conditions. Systematic analysis was performed on the independent effects and synergistic interactions of deposition duration (15 s vs. 30 s) and NaH2PO2 concentration (0–30 g/L). Comparative SEM analysis of comparable specimen domains is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Copper loading on CFs with different concentrations of NaH2PO2 at electroplating times of 15 s (left) and 30 s (right): (a1–b2): 0 g/L; (c1–d2): 5 g/L; (e1–f2): 10 g/L; (g1–h2): 20 g/L; (i1–j2): 30 g/L.

In the longitudinal dimension, samples prepared with fixed deposition time but varying NaH2PO2 concentrations were compared (15 s group left vs. 30 s group right). A pronounced nucleation density gradient correlated with NaH2PO2 concentration was observed, with CF surfaces exhibiting higher copper particle coverage at increased concentrations. Partial copper particle coalescence was observed at 30 g/L (Figure 4(i1–j2)), contrasting with exclusively discrete copper particles in NaH2PO2-free controls (0 g/L, Figure 4(a1–b2)). Notably, copper particle size remained independent of the NaH2PO2 concentration, as evidenced by consistent size distributions in high- and low-concentration regimes (such as Figure 4(c2,d2,g2,h2)). Temporal analysis showed that particle size increased with deposition time, independent of nucleation density alterations. Self-limiting deposition emerged at 20–30 g/L (Figure 4(g1–j2)), where morphological convergence indicated nucleation thresholding, consistent with the reduced copper loading rate increment observed in Figure 2a. These results confirm that NaH2PO2 primarily initiates nucleation without significantly affecting post-nucleation growth dynamics.

In the plating bath without NaH2PO2, copper ions are mainly complexed by Na3Cit to form stable complexes. During electroplating, the negatively charged CF surface attracts positively charged species; however, strong complexation keeps the concentration of free copper ions low, limiting copper deposition. Specifically, the complexes must dissociate to release copper ions, which then undergo adsorption, reduction, and nucleation on the CF surface [41]. NaH2PO2 acts primarily at this stage. The reductive deposition of copper on CF surfaces proceeds through two sequential stages: (1) adsorption-coupled reductive nucleation at active sites and (2) progressive growth into continuous metallic coatings [31,36]. NaH2PO2 modulates the first stage by lowering the copper reduction potential, thereby reducing the activation energy barrier for nucleation. This adjustment induces higher nuclei density in cathodic regions of CFs. The negatively charged CF surface facilitates the preferential adsorption of both nascent copper nuclei and dissolved Cu2+, extending even to the core regions of CF bundles. Consequently, NaH2PO2 substantially enhances the density of copper particles on CF surfaces, promoting their coalescence into continuous, compact copper layers. However, excessive concentrations cause the saturation of nucleation sites on CF surface. This leads to nucleation in the bulk solution, generating free copper powder and reducing bath stability. In this acidic bath (pH 4.6), the primary reaction involving NaH2PO2 is accompanied by a change in the valence state of phosphorus, with electron transfer occurring in the redox reaction [31,42,43]:

NaH2PO2 + H2O ⟶ NaH2PO3 + 2H

The overall reaction equation of the entire system can be presented as follows:

CuSO4 + NaH2PO2 + H2O ⟶ Cu + H2SO4 + NaH2PO3

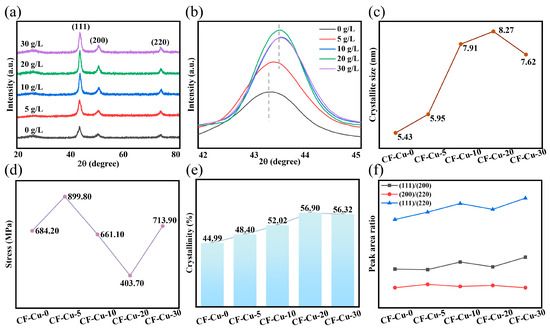

3.2. Effect of NaH2PO2 on Plating of CF-Cu

XRD analysis was employed to evaluate the quality of the copper coating. To ensure measurement reliability, fiber bundles were sectioned and evenly dispersed on the sample stage. Figure 5a presents the diffraction patterns of different samples, exhibiting three crystalline characteristic peaks and one amorphous peak. The amorphous peak was identified as the typical CF diffraction peak [17,25]. The persistent presence of carbon diffraction peaks at elevated NaH2PO2 concentrations indicates incomplete copper coating of individual filaments in CF-Cu bundles. This phenomenon arises from a mechanical interlocking bonding mechanism at the copper–fiber interface, where localized void formation or coating detachment may occur during adhesion, aligning with observations by Zhang et al. [29,35]. The CF-Cu-0 sample displayed three well-defined diffraction peaks at 2θ = 43.30°, 50.29°, and 74.05°. These peaks correspond to the (111), (200), and (220) crystallographic planes of copper’s Face-Centered Cubic (FCC) structure (JCPDS No. 04-0836) [8,27,30]. Figure 5b compares the Cu(111) diffraction peaks across specimens. NaH2PO2 introduction significantly enhanced the Cu(111) diffraction peak intensity (maximum in 20 g/L group), concurrent with a characteristic peak shift from 43.30° to 43.53°. This angular shift corresponds to reduced interplanar spacing (d-spacing) and unit cell volume contraction. However, this concentration-dependent behavior exhibits non-monotonic characteristics. Compared to the 10 g/L group, the 20 g/L specimen displayed a peak shift toward lower angles, indicating unit cell expansion, whereas 30 g/L samples restored the right-shifting trend with volume contraction (Table S1). This oscillatory contraction-expansion pattern of the unit cell volume was consistently observed in both Cu(200) and Cu(220) planes, with corresponding diffraction peak shifts detailed in Figure S2.

Figure 5.

Properties of CF-Cu with different additions of NaH2PO2: (a) X-ray diffraction spectra; (b) high-resolution diffraction peak of Cu(111) crystal plane; (c) crystallite size; (d) internal stress of the coating; (e) change in crystallinity; (f) change in the area ratio of crystal diffraction peaks.

The crystalline evolution of copper coatings was quantitatively analyzed through Gaussian fitting analysis, and the specific data are summarized in Figure S2a–e. As shown in Figure 5c, the crystallite size () calculated from the fitting parameters (Table S2) reveal that the introduction of NaH2PO2 substantially enhanced grain coarsening. CF-Cu-20 demonstrated a D of 8.27 nm, representing a 52.30% increase compared to the control group CF-Cu-0 ( 5.43 nm). Internal stress evolution in the coating was quantified through Williamson–Hall analysis (Figure S3, inset), where the linear slope directly reflects the strain parameter. Based on the equation, (where is the internal stress, ε denotes strain, and represents Young’s modulus, with 110 GPa for copper), the computational results in Figure 5d show that CF-Cu-20 achieved the lowest internal stress ( 403.70 MPa), corresponding to a 41.00% reduction compared to CF-Cu-0 ( 684.20 MPa). Crystallinity and preferential orientation were evaluated through peak area analysis and texture coefficient calculations. Figure 5e reveals a non-monotonic dependence of crystallinity on NaH2PO2 concentration, with CF-Cu-20 achieving the peak value of 56.90%. This corresponds to a 1.26-fold increase relative to CF-Cu-0, signifying optimal crystal integrity. Figure 5f shows stable (200)/(220) peak area ratios, while both (111)/(200) and (111)/(220) ratios demonstrated an overall upward trend. Despite slight deviations in CF-Cu-20, its (111) texture coefficient (Table S3) exceeds that of CF-Cu-0, confirming the (111) plane as the predominant growth orientation. This preferential alignment originates from minimized lattice mismatch spacing during electrodeposition, thereby facilitating epitaxial alignment along this crystallographic orientation [44]. These (111)-oriented copper coatings exhibit enhanced electromigration resistance and reduced electrical resistivity, fulfilling the functional requirements for CF-Cu composite applications [22].

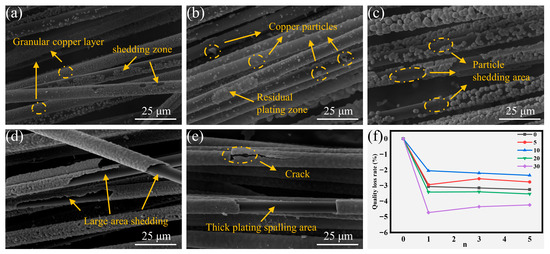

Thermal shock and ultrasonic testing were employed to evaluate the interfacial bond strength at the copper-CF interface. After five thermal shock cycles, the morphological evolution and corresponding mass loss rates of coatings across all experimental groups are presented in Figure 6. The predominant failure mode manifested as lamellar spallation of continuous copper coatings under thermal stress. The low-concentration groups (CF-Cu-0 and CF-Cu-5) exhibited minimal mass loss (Figure 6f), attributable to their lower copper loading capacity and larger proportion of uncoated CF regions. While local detachment of intact coatings occurred in low-concentration groups, particulate loss remained the primary failure mode (Figure 6a). Particulate detachment was generally limited due to sparse particle distribution in these groups, consistent with the observed structural coherence (Figure 6b). Among the medium-concentration groups, CF-Cu-10 showed enhanced spallation resistance compared to CF-Cu-20, despite exhibiting higher internal stresses. This performance divergence arises from differences in their microstructural characteristics. Although both medium-concentration groups exhibited comparable copper loading capacities (Figure 2a), CF-Cu-20 experienced adhesive failure of its continuous coating structure under thermal stress, while CF-Cu-10’s particulate morphology localized the delamination to discrete regions (Figure 6c,d), demonstrating distinct stress dissipation pathways. High-concentration groups developed significant internal stresses due to copper overloading, leading to progressive crack propagation that ultimately caused extensive coating delamination and significant mass loss (Figure 6e).

Figure 6.

Morphologies of coating damage on CF-Cu after five thermal shock treatments with different additions of NaH2PO2: (a) CF-Cu-0; (b) CF-Cu-5; (c) CF-Cu-10; (d) CF-Cu-20; (e) CF-Cu-30 and (f) Mass loss rate.

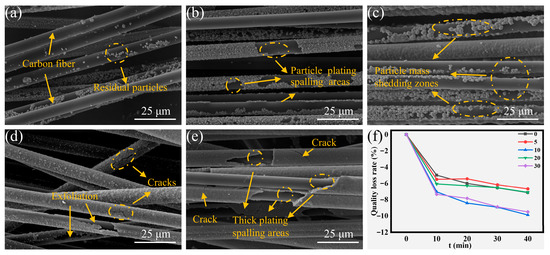

Ultrasonic treatment for 40 min induced distinct morphological alterations and differential mass loss characteristics among all experimental groups, as shown in Figure 7. The low-concentration groups maintained minimal mass loss, whereas high-concentration counterparts exhibited maximum mass depletion, correlating with the previously elucidated failure mechanisms (Figure 7a,b,e). Of particular note, medium-concentration groups displayed an inverse mass loss pattern relative to thermal shock failure modes (Figure 7f). This inversion originates from fundamentally different damage mechanisms between cavitation-induced mechanical stresses and thermal stress. Particulate-loaded coatings displayed higher susceptibility to ultrasonic degradation, whereas monolithic coating architectures exhibited enhanced resistance to sonication-induced damage. Specifically, the particulate-laden CF-Cu-10 showed extensive interfacial delamination, whereas CF-Cu-20 retained sufficient interfacial adhesion between the coating and the CF substrate despite visible microcracks (Figure 7c,d). Collectively, the extent of mass loss was determined by the integrated effects of coating morphology and coating quality, with their relative contribution varying across different failure modalities.

Figure 7.

Morphologies of coatings on CF-Cu after 40 min ultrasonic damage treatment with different additions of NaH2PO2: (a) CF-Cu-0; (b) CF-Cu-5; (c) CF-Cu-10; (d) CF-Cu-20; (e) CF-Cu-30 and (f) Mass loss rate.

Notably, although the addition of NaH2PO2 has been experimentally demonstrated to facilitate copper deposition, enhance coating integrity, and reduce internal stress, the macroscopic interfacial bonding strength did not exhibit a commensurate increase. This suggests that the adhesion between copper and CFs is governed by other critical factors. The primary reason is the inherent chemical inertness of CFs, which impedes the formation of strong chemical bonds with copper. In this study, interfacial bonding was attributed primarily to mechanical interlocking arising from copper deposition into surface asperities, rather than chemical interaction. This observation aligns with the findings of Zhang and Han [28,29]. The efficacy of this physical anchoring mechanism is constrained by the surface topography of the CFs. Consequently, despite the formation of a denser coating, substantial enhancements in macroscopic adhesion strength remain challenging. Therefore, achieving fundamental improvements in interfacial bond strength necessitates the exploration of interfacial modification strategies that surpass the limitations of the current methodology.

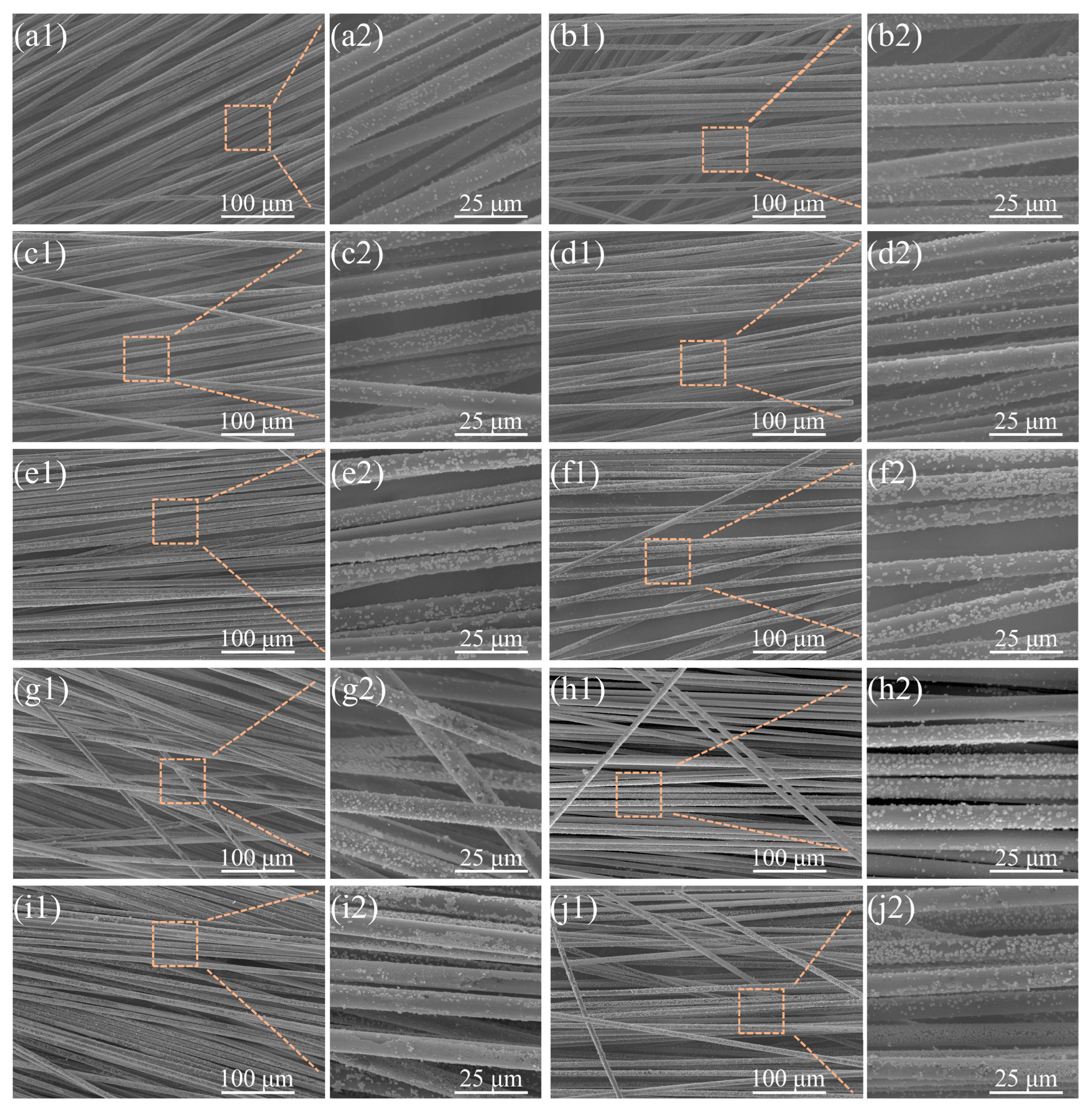

3.3. The Adhesion and Growth Process of Copper on CF Surfaces

The microstructural evolution during copper adsorption–deposition on CF surfaces was systematically characterized (Figure 8). Oxidized CF surface demonstrated lamellar groove morphology (Figure 8a), creating preferential anchoring sites that facilitate mechanical interlocking with the copper coating. Initial adsorption analysis (Figure 8) revealed site-selective copper particulate deposition on CF surfaces, where spatial heterogeneities in polar group distribution, surface defects, and roughness collectively generated reaction microdomains promoting Cu2+ reduction through synergistic effects of electrostatic accumulation, elevated surface energy, and complex field distribution [35,36,45,46]. Initial nucleation exhibited spatially discrete particle distribution, as evidenced by sparse particle attachment and the absence of copper coloration (Figure 8(b1)). As deposition progressed, adsorbed copper particles underwent continuous growth via Cu2+ absorption, concomitant with nucleation at other surface sites (Figure 8c). Copper particles predominantly covered most CF surfaces at this stage, where CLSM imaging (Figure 8(c1)) confirmed localized metallic luster, while exposed CF areas persisted between particles without 3D interconnectivity. Significantly, dimensional variation and spatial density of adhered copper particles predominantly dictated the diameter distributions characteristics of CF-Cu monofilaments. The evolution of island-type interconnected architectures was driven by progressive particle coalescence (Figure 8d), leading to improved surface coverage and incipient coating formation. The surface displayed macroscopic copper metallization, where CF substrate exposure was confined to limited regions (Figure 8(d1)). While the established conductive network effectively improved electrical conductivity, mechanical stability limitations were identified through ultrasonic testing, especially in low-concentration specimens where core fibers predominantly maintained this architecture (Figure 1). Terminal deposition stage achieved complete copper coating formation through coalescence of coarse particles via interconnections, presenting characteristic rough surface morphology (Figure 8e). Complete CF encapsulation was attained, exhibiting a copper-wire-like appearance without observable CF exposure, which confirms full substrate coverage (Figure 8(e1)). Inter-filament diameter variations are attributable to heterogeneities in current density distribution across individual CF. The schematic diagram of copper deposition process on CF surfaces is presented in Figure 8f.

Figure 8.

Process of copper loading on CFs in the presence of NaH2PO2 (a–e) and corresponding CLSM images (a1–e1); (f) schematic diagram.

3.4. Effect of NaH2PO2 on the Properties of CF-Cu

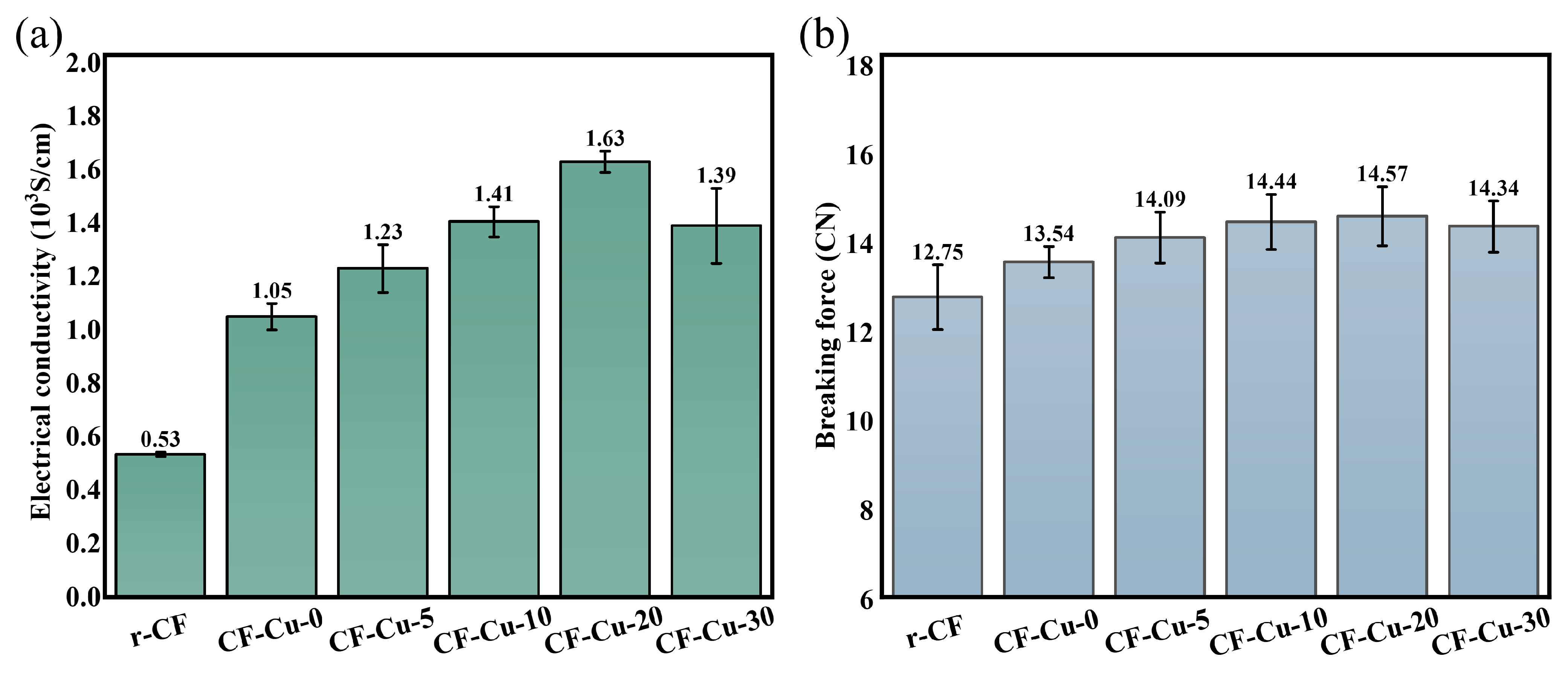

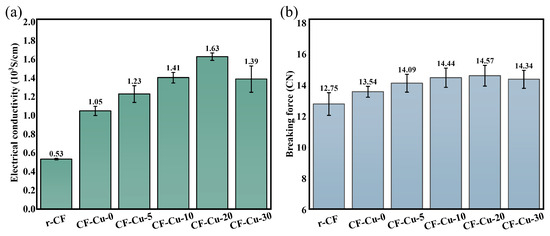

Figure 9a presents a comparative analysis of the electrical properties between r-CF and CF-Cu specimens. As evidenced by experimental data, CF-Cu-0 demonstrated a single-filament conductivity of 1.05 × 103 S·cm−1, representing a 98.11% improvement compared to r-CF (0.53 × 103 S·cm−1). This conductivity enhancement is attributed to the superior intrinsic conductivity of copper (5.71 × 105 S·cm−1). Given that the material’s conductivity is largely governed by the copper layer, the quality of the coating directly determines the overall electrical performance [9,26]. At optimal NaH2PO2 concentration (20 g/L), CF-Cu-20 exhibited enhanced conductivity of 1.63 × 103 S·cm−1, corresponding to a 55.24% improvement relative to CF-Cu-0. This performance augmentation is attributed to NaH2PO2 facilitating the formation of a densely interconnected copper coating. Diminished interparticle spacing facilitated metallic bridge formation, thereby reducing interfacial contact resistance while establishing continuous electron conduction pathways, as evidenced by microstructural characterization (Figure 4). Furthermore, NaH2PO2 promoted grain coarsening and induced preferential (111) plane orientation in the copper coating (Figure 5). These structural modifications enhanced crystallinity while mitigating internal stress and microdefect formation, consequently suppressing electron scattering phenomena [29]. However, when the NaH2PO2 concentration exceeds 20 g/L, this optimized mechanism is disrupted. Specifically, an excessive concentration of the reducing agent accelerates the deposition rate, leading to a significant increase in internal stress within the coating. This makes the coating more susceptible to cracking and delamination, manifesting as a marked decrease in adhesion strength (Figure 6 and Figure 7). This compromise in structural integrity is the primary cause of the degradation in electrical conductivity.

Figure 9.

(a) Electrical properties and (b) mechanical properties of CF-Cu prepared in plating solutions with different concentrations of NaH2PO2.

As demonstrated in Figure 9b, the copper coating produced a 6.20% increase in breaking force for CF-Cu-0 relative to r-CFs, a result ascribed to its mechanical reinforcement effect. CF-Cu-20 achieved the maximum breaking force of 14.57 cN, representing only a 7.61% increase compared to CF-Cu-0. This limited mechanical improvement originates from copper’s inherently inferior mechanical characteristics relative to CFs. While the mechanical performance of CF-Cu is predominantly dictated by the CF substrate, factors including coating–substrate adhesion, structural integrity, and coating quality still modulate the overall properties. Experimental findings reveal that although NaH2PO2 showed limited improvement in coating–substrate adhesion, its effectiveness in enhancing coating compactness and optimizing microstructure counterbalanced the detrimental effects of interfacial weakness, ultimately contributing to breaking force improvement. When the concentration of NaH2PO2 is excessively high, the degradation of the coating quality diminishes its reinforcing effect, and the breaking force decreases accordingly.

4. Conclusions

This study successfully prepared CF-Cu bundles via electrodeposition in NaH2PO2-modified baths, achieving enhanced copper encapsulation integrity. The experimental results suggested three principal findings:

- The properties of CF-Cu exhibit a distinct relationship with the NaH2PO2 concentration in the plating solution. Elevated concentrations correlate positively with augmented copper loading and improved core CF encapsulation integrity in CF-Cu bundles. Optimal performance was achieved at 20 g/L, where single-filament electrical conductivity increased from 1.05 × 103 (at 0 g/L) to 1.63 × 103 S·cm−1, coupled with breaking force enhancement from 13.54 cN to 14.57 cN. Beyond this concentration, both electrical and mechanical properties exhibited deterioration.

- Cathodic polarization curve analysis indicates that NaH2PO2 lowers the reduction potential of Cu2+. CV and SEM analyses confirmed that NaH2PO2 does not produce coordination complexes with Cu2+ but primarily increases nucleation density on CF surfaces through lowered activation energy for copper deposition, resulting in enhanced coating densification. XRD analysis demonstrated three microstructural changes at the optimal concentration (CF-Cu-20): a 52.30% increase in grain coarsening, a reduction in internal stress to 403.70 MPa, and a preferential orientation along the (111) crystallographic plane. However, adhesion tests showed no significant improvement in interfacial bonding strength between the coating and substrate. CF-Cu-30 exhibited 4.25% and 9.50% mass loss under thermal shock and ultrasonic impact tests, respectively. In contrast, CF-Cu-20 maintained structural stability with no significant quality deterioration compared to the control group, demonstrating optimal performance characteristics with balanced coating properties.

- SEM observations delineated four sequential copper deposition phases on CF surfaces: initial particle adsorption, particle growth with concurrent new nucleation, interparticle bridging, and final continuous coating formation. Notably, these phases progressed dynamically in parallel during copper deposition, with current density variations among monofilaments correlating with this parallel progression and ultimately manifesting as diameter discrepancies.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/fib14010005/s1. Table S1: Changes in interplanar spacing of CF-Cu with the addition of NaH2PO2 at different concentrations in the plating solution. Table S2: XRD crystal peak diffraction angles (2θ), full widths at half maximum (FWHM), and grain sizes (D) of CF-Cu with the addition of NaH2PO2 at different concentrations in the plating solution. Table S3: Changes in texture coefficients of CF-Cu with the addition of NaH2PO2 at different concentrations in the plating solution. Figure S1: Single plating solution component: (a) CV curve, (b) high-resolution image of the reduction region, and (c) high-resolution image of the oxidation region. Figure S2: High-resolution images of (a) (200) crystal plane diffraction peak and (b) (220) crystal plane diffraction peak of copper. Figure S3: XRD fitting plots of CF-Cu under different concentrations of NaH2PO2: (a) CF-Cu-0, (b) CF-Cu-5, (c) CF-Cu-10, (d) CF-Cu-20, and (e) CF-Cu-30 (inset is the Williamson–Hall plot).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.L., W.J., T.Y. and K.Q.; validation, H.L., T.Y. and K.Q.; formal analysis, H.L., S.H. and S.C.; investigation, H.L., W.J. and W.Y.; resources, K.Q.; data curation, H.L., S.H., G.Z., W.Y. and S.C.; writing—original draft preparation, H.L.; writing—review and editing, T.Y. and K.Q.; project administration, S.H. and G.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article or Supplementary Materials.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the Physical-Chemical Materials Analytical & Testing Center at Shandong University, Weihai.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CFs | carbon fibers |

| CF-Cu | copper-plated carbon fibers |

References

- Shi, B.; Shang, Y.; Pei, Y.; Pei, S.; Wang, L.; Heider, D.; Zhao, Y.Y.; Zheng, C.; Yang, B.; Yarlagadda, S.; et al. Low tortuous, highly conductive, and high-areal-capacity battery electrodes enabled by through-thickness aligned carbon fiber framework. Nano Lett. 2020, 20, 5504–5512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lund, A.; Wu, Y.; Fenech-Salerno, B.; Torrisi, F.; Carmichael, T.B.; Muller, C. Conducting materials as building blocks for electronic textiles. MRS Bull. 2021, 46, 491–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daneshvar, F.; Tagliaferri, S.; Chen, H.; Zhang, T.; Liu, C.; Sue, H.-J. Ultralong electrospun copper–carbon nanotube composite fibers for transparent conductive electrodes with high operational stability. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2020, 2, 2692–2698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Li, N.; Childs, P.R.N. Light-weighting in aerospace component and system design. Propuls. Power Res. 2018, 7, 103–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, S.; Maaß, F.; Kamaliev, M.; Hahn, M.; Gies, S.; Tekkaya, A.E. Lightweight in automotive components by forming technology. Automot. Innov. 2020, 3, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohatgi, P.; Weiss, D.; Srivatsan, T.S.; Ghaderi, O.; Zare, M. Solidification processing of aluminum alloy metal matrix composites for use in transportation applications. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2024, 55, 4867–4881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cliche, M.-L.; Mone, R.; Liberati, A.C.; Stoyanov, P. Influence of fiber direction on the tribological behavior of carbon reinforced peek for application in gas turbine engines. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2025, 511, 132212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.; Lee, D.-M.; Park, M.; Park, S.; Lee, D.S.; Kim, T.-W.; Lee, S.H.; Lee, S.-K.; Jeong, H.S.; Hong, B.H.; et al. Performance enhancement of graphene assisted cnt/cu composites for lightweight electrical cables. Carbon 2021, 179, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.Q.; Lee, J.K.Y.; Chinnappan, A.; Loc, N.H.; Tran, L.T.; Ji, D.; Jayathilaka, W.A.D.M.; Kumar, V.V.; Ramakrishna, S. High-performance carbon fiber/gold/copper composite wires for lightweight electrical cables. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2020, 42, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Gao, Y.; Li, T.; Ma, L.; Qi, Q.; Yang, T.; Meng, F. Advances in carbon fiber-based electromagnetic shielding materials: Composition, structure, and application. Carbon 2024, 226, 119203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, K.B.M.; Kumar, M.A.; Mahalingam, S.; Raj, B.; Kim, J. Carbon fiber-reinforced polymers for energy storage applications. J. Energy Storage 2024, 84, 110931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, A.; Zhang, S.; Guo, B.; Niu, D. A review on new methods of recycling waste carbon fiber and its application in construction and industry. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 367, 130301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almushaikeh, A.M.; Alaswad, S.O.; Alsuhybani, M.S.; AlOtaibi, B.M.; Alarifi, I.M.; Alqahtani, N.B.; Aldosari, S.M.; Alsaleh, S.S.; Haidyrah, A.S.; Alolyan, A.A.; et al. Manufacturing of carbon fiber reinforced thermoplastics and its recovery of carbon fiber: A review. Polym. Test. 2023, 122, 108029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Zhang, W.; Li, B.; Zhu, J.; Wang, C.; Song, G.; Wu, G.; Yang, X.; Huang, Y.; Ma, L. Recent advances of interphases in carbon fiber-reinforced polymer composites: A review. Compos. Part B Eng. 2022, 233, 109639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basheer, B.; Akhil, M.G.; Rajan, T.P.D.; Agarwal, P.; Vijay Saikrishna, V. Copper metallization of carbon fiber-reinforced epoxy polymer composites by surface activation and electrodeposition. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2024, 487, 131016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, H.; He, X.; Zhu, P.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, T.; Qu, X. Microstructure and thermal properties of copper matrix composites reinforced by 3d carbon fiber networks. Compos. Commun. 2023, 44, 101758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, J.-J.; Lü, Z.-Z.; Sha, R.-Y.; Zu, Y.-F.; Dai, J.-X.; Xian, Y.-Q.; Zhang, W.; Cui, D.; Yan, C.-L. Improved wettability and mechanical properties of metal coated carbon fiber-reinforced aluminum matrix composites by squeeze melt infiltration technique. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2021, 31, 317–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheon, J.; Kim, M. Impact resistance and interlaminar shear strength enhancement of carbon fiber reinforced thermoplastic composites by introducing mwcnt-anchored carbon fiber. Compos. Part B Eng. 2021, 217, 108872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Zhang, L.; Song, J.; Wang, X.; Liu, H. Superhydrophobic nickel-electroplated carbon fibers for versatile oil/water separation with excellent reusability and high environmental stability. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 24390–24402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Guo, L.; Qi, L.; Sun, J.; Wang, J.; Cao, Y. Growth mechanism and thermal behavior of electroless cu plating on short carbon fibers. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2021, 419, 127294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tang, B.; Gao, Y.; Wu, X.; Chen, J.; Shan, L.; Sun, K.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, K.; Yu, J.; et al. Epoxy composites with high thermal conductivity by constructing three-dimensional carbon fiber/carbon/nickel networks using an electroplating method. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 19238–19251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Q.; Li, G.; Zhou, Z.; Qu, Y.; Chen, R.; Gao, X.; Xu, W.; Nie, S.; Tian, C.; Li, R. Effect of Ni2+ concentration on microstructure and bonding capacity of electroless copper plating on carbon fibers. J. Alloy Compd. 2021, 863, 158467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, H.; He, X.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, J.; Qu, X. Effect of tungsten carbide interface decoration on thermal and mechanical properties of carbon fiber reinforced copper matrix composites. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 41, 110810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, F.; Masuda, C.; Fujii, H. In situ chemical vapor deposition of metals on vapor-grown carbon fibers and fabrication of aluminum-matrix composites reinforced by coated fibers. J. Mater. Sci. 2017, 53, 5036–5050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Cui, Y.; Bao, D.; Lin, D.; Yuan, S.; Wang, X.; Wang, H.; Sun, Y. A 3D interconnected cu network supported by carbon felt skeleton for highly thermally conductive epoxy composites. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 388, 124287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, H.; Kim, J.Y.; Gul, H.Z.; Kang, S.; Kim, G.; Sim, E.; Ji, H.; Kim, J.; Choi, Y.C.; Kim, W.S.; et al. Wiedemann-franz law of cu-coated carbon fiber. Carbon 2020, 162, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.-H.; Chung, K.C. Investigation of a copper–nickel alloy resistor using co-electrodeposition. J. Appl. Electrochem. 2020, 50, 535–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W.; Qian, X.; Ma, H.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y. Effect of nickel electroplating followed by a further copper electroplating on the micro-structure and mechanical properties of high modulus carbon fibers. Mater. Today Commun. 2021, 27, 102345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Yu, J.; Su, C.; Di, C.; Ci, S.; Mou, Y.; Fu, Y.; Qiao, K. The effect of annealing on the properties of copper-coated carbon fiber. Surf. Interfaces 2023, 37, 102630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, D.; Liu, T.; Jiang, G.; Chen, W. Synthesis of highly stable dispersions of copper nanoparticles using sodium hypophosphite. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2012, 128, 1443–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Y.; Yu, G.; Hu, B.; Dong, Q.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X. Effect of hypophosphite on electrodeposition of graphite@copper powders. Adv. Powder Technol. 2014, 25, 477–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Li, W.; Liu, X.; Feng, M.; Yang, J. Study on structure and performance of surface-metallized carbon fibers reinforced rigid polyurethane composites. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2020, 31, 1805–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giurlani, W.; Fidi, A.; Anselmi, E.; Pizzetti, F.; Bonechi, M.; Carretti, E.; Lo Nostro, P.; Innocenti, M. Specific ion effects on copper electroplating. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2023, 225, 113287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ASTM B571-23; Standard Practice for Qualitative Adhesion Testing of Metallic Coatings. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2023.

- Zhang, G.; Yang, W.; Ding, J.; Liu, M.; Di, C.; Ci, S.; Qiao, K. Influence of carbon fibers on interfacial bonding properties of copper-coated carbon fibers. Carbon Lett. 2024, 34, 1055–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Liu, L.; Zhong, C.; Shen, B.; Hu, W. Effect of carbon fiber surface treatment on cu electrodeposition: The electrochemical behavior and the morphology of cu deposits. J. Alloy Compd. 2011, 509, 3532–3536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turoňová, A.; Gálová, M.; Šupicová, M. Parameters influencing the electrodeposition of a ni-cu coating on fe powders. I. Effect of the electrolyte composition and current density. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2003, 7, 684–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, Y.-D.; Dow, W.-P. Accelerator screening by cyclic voltammetry for microvia filling by copper electroplating. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2013, 160, D3021–D3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satpathy, B.; Jena, S.; Das, S.; Das, K. A comparative study of electrodeposition routes for obtaining silver coatings from a novel and environment-friendly thiosulphate-based cyanide-free electroplating bath. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2021, 424, 127680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Ortega, C.M.; Liu, Z.; Du, J.; Wu, X.; Cai, Z.; Sun, L. In situ study of copper electrodeposition on a single carbon fiber. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2013, 690, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rode, S.; Henninot, C.; Vallie`res, C.; Matlosz, M. Complexation chemistry in copper plating from citrate baths. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2004, 151, C405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, A.; Chen, K. Mechanism of hypophosphite-reduced electroless copper plating. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1989, 136, 72–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Yang, B.; Lu, B.; Huang, L.; Xu, S.; Zhou, S. Electrochemical study on electroless copper plating using sodium hypophosphite as reductant. Acta Phys.-Chim. Sin. 2006, 22, 1317–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Park, B.-I.; Park, C.; Hong, S.M.; Han, T.H.; Koo, C.M. Rta-treated carbon fiber/copper core/shell hybrid for thermally conductive composites. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 7498–7503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varentsova, V.I.; Varenstov, V.K.; Bataev, I.A.; Yusin, S.I. Effect of surface state of carbon fiber electrode on copper electroplating from sulfate solutions. Prot. Met. Phys. Chem. Surf. 2011, 47, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafailović, L.D.; Trišović, T.; Stupavská, M.; Souček, P.; Velicsanyi, P.; Nixon, S.; Elbataioui, A.; Zak, S.; Cordill, M.J.; Hohenwarter, A.; et al. Selective cu electroplating enabled by surface patterning and enhanced conductivity of carbon fiber reinforced polymers upon air plasma etching. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 992, 174569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.