A Green Binary Solvent System for the PLA Nanofiber Electrospinning Process: Optimization of Parameters

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. X-Ray Diffraction Analysis of PLA Grades

2.3. Solution Preparation and Stability

2.4. Viscosity Measurements

2.5. Electrospinning Process

2.6. Morphological Characterization (SEM)

2.7. Thermal Properties by DSC

2.8. Tensile Testing

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Crystalline Structure of PLA Grades by XRD

3.2. Solution Stability and Solubility Behavior

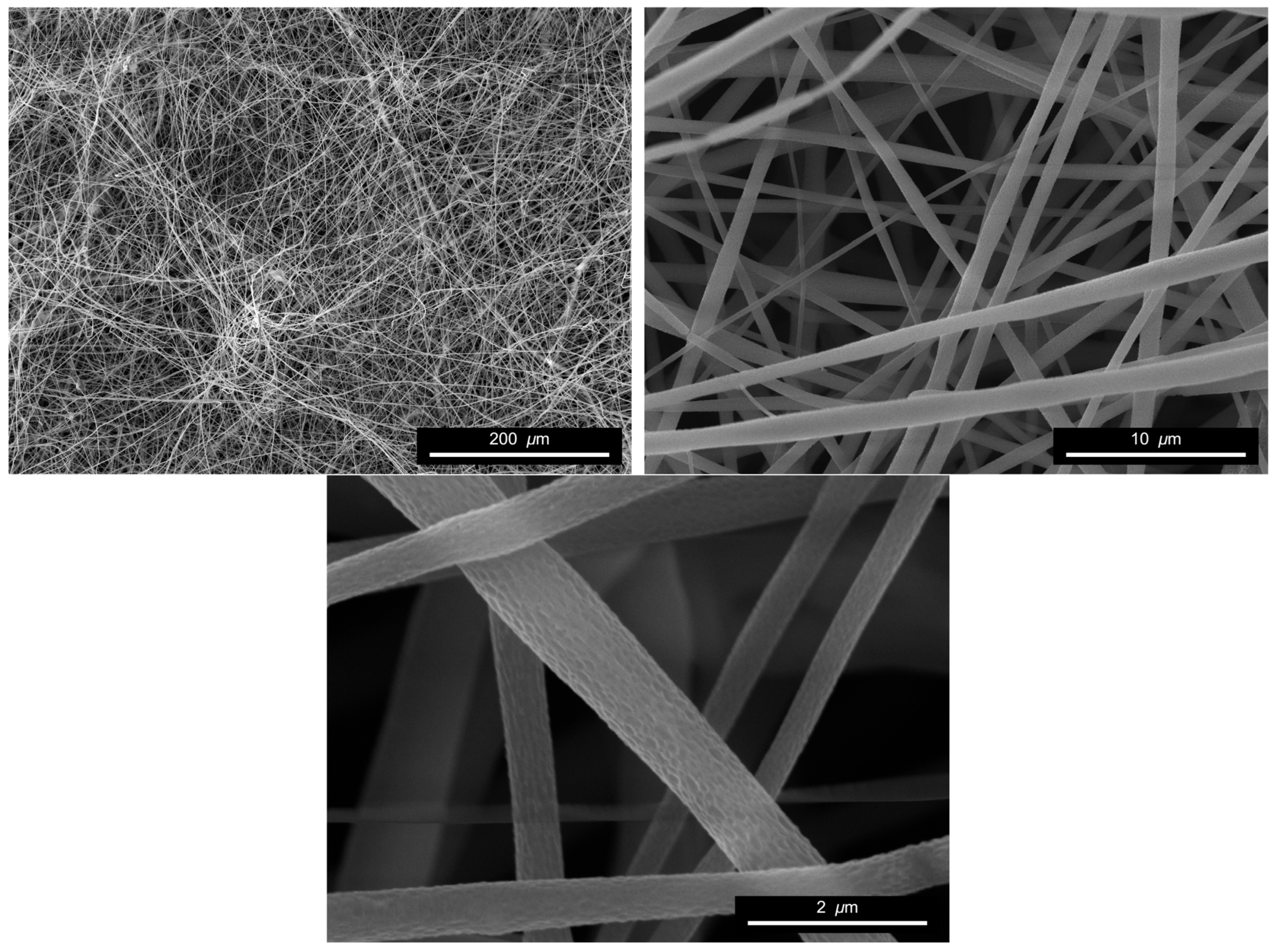

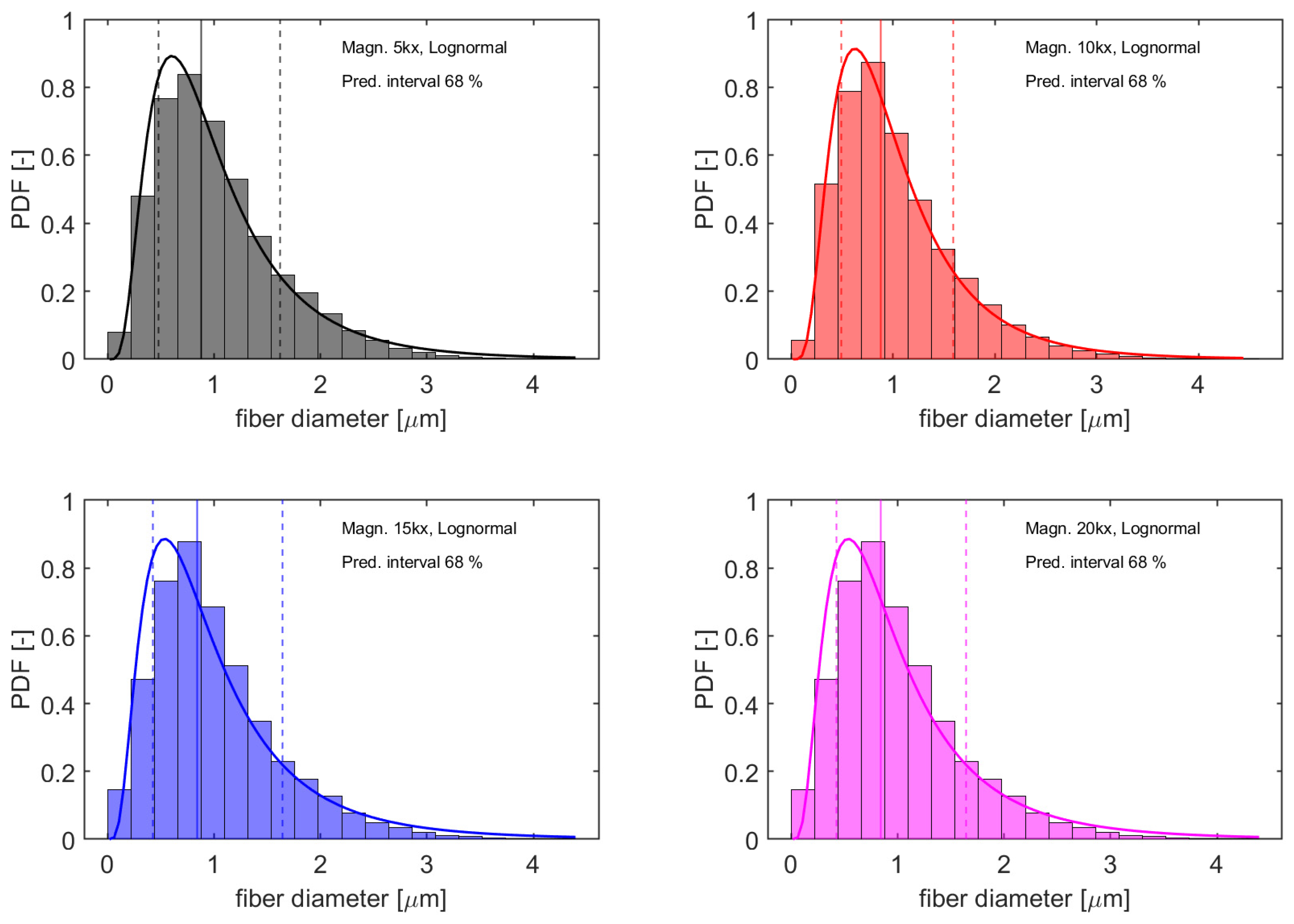

3.3. Morphology of Electrospun Fibers

3.4. Thermal Behavior by DSC

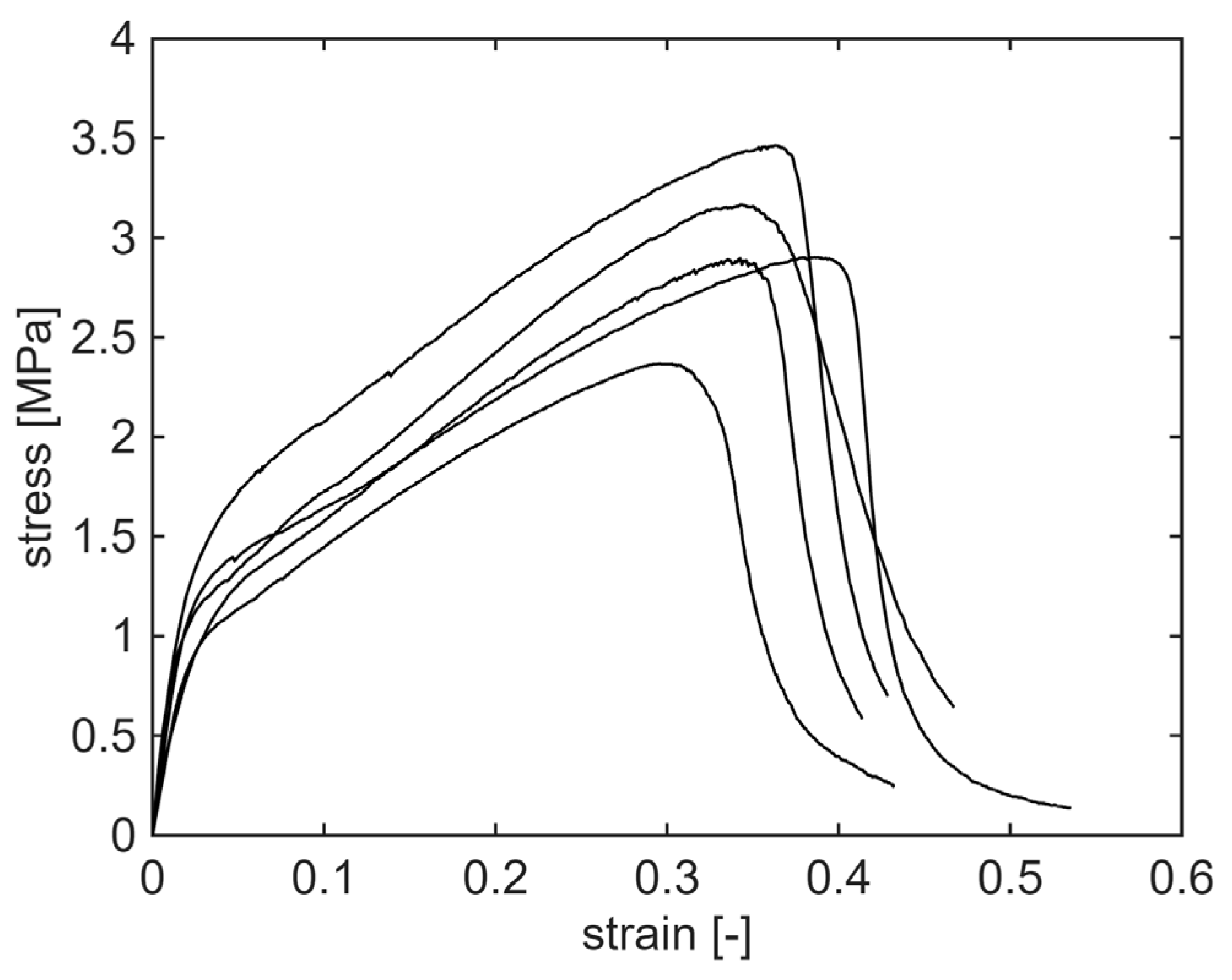

3.5. Mechanical Properties of Electrospun Mats

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Castañeda-Rodríguez, S.; González-Torres, M.; Ribas-Aparicio, R.M.; Del Prado-Audelo, M.L.; Leyva-Gómez, G.; Gürer, E.S.; Sharifi-Rad, J. Recent Advances in Modified Poly (Lactic Acid) as Tissue Engineering Materials. J. Biol. Eng. 2023, 17, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khouri, N.G.; Bahú, J.O.; Blanco-Llamero, C.; Severino, P.; Concha, V.O.C.; Souto, E.B. Polylactic Acid (PLA): Properties, Synthesis, and Biomedical Applications—A Review of the Literature. J. Mol. Struct. 2024, 1309, 138243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Yin, G.; Sun, S.; Xu, P. Medical Applications and Prospects of Polylactic Acid Materials. iScience 2024, 27, 111512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, J. Research Progress in Toughening Modification of Poly(Lactic Acid). J. Polym. Sci. Part B Polym. Phys. 2011, 49, 1051–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Lin, Y.; Liu, M.; Meng, L.; Li, C. A Review of Research and Application of Polylactic Acid Composites. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2023, 140, e53477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chieng, B.W.; Ibrahim, N.A.; Yunus, W.M.Z.W.; Hussein, M.Z. Poly(Lactic Acid)/Poly(Ethylene Glycol) Polymer Nanocomposites: Effects of Graphene Nanoplatelets. Polymers 2014, 6, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peixoto, T.; Nunes, J.; Lopes, M.A.; Marinho, E.; Proença, M.F.; Lopes, P.E.; Paiva, M.C. Poly(Lactic Acid) Composites with Few Layer Graphene Produced by Noncovalent Chemistry. Polym. Compos. 2022, 43, 8409–8425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokharel, A.; Falua, K.J.; Babaei-Ghazvini, A.; Nikkhah Dafchahi, M.; Tabil, L.G.; Meda, V.; Acharya, B. Development of Polylactic Acid Films with Alkali- and Acetylation-Treated Flax and Hemp Fillers via Solution Casting Technique. Polymers 2024, 16, 996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadimitriou, L.; Manganas, P.; Ranella, A.; Stratakis, E. Biofabrication for Neural Tissue Engineering Applications. Mater. Today Bio 2020, 6, 100043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolova, M.P.; Chavali, M.S. Recent Advances in Biomaterials for 3D Scaffolds: A Review. Bioact. Mater. 2019, 4, 271–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarei, M.; Shabani Dargah, M.; Hasanzadeh Azar, M.; Alizadeh, R.; Mahdavi, F.S.; Sayedain, S.S.; Kaviani, A.; Asadollahi, M.; Azami, M.; Beheshtizadeh, N. Enhanced Bone Tissue Regeneration Using a 3D-Printed Poly(Lactic Acid)/Ti6Al4V Composite Scaffold with Plasma Treatment Modification. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 3139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sofokleous, P.; Chin, M.H.W.; Day, R. Phase-Separation Technologies for 3D Scaffold Engineering. In Functional 3D Tissue Engineering Scaffolds; Woodhead Publishing: London, UK, 2018; pp. 101–126. [Google Scholar]

- Szlek, D.B.; Fan, E.L.; Frey, M.W. Multifunctional, Flexible, Electrospun Lignin/PLA Micro/Nanofiber Mats from Softwood Kraft, Hardwood Alcell, and Switchgrass CELF Lignin. Fibers 2025, 13, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, K.; Molnár, K. The Influence of In Vitro Degradation on the Properties of Polylactic Acid Electrospun Fiber Mats. Fibers 2024, 13, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casasola, R.; Thomas, N.L.; Georgiadou, S. Electrospinning of Poly(Lactic Acid): Theoretical Approach for the Solvent Selection to Produce Defect-Free Nanofibers. J. Polym. Sci. Part B Polym. Phys. 2016, 54, 1483–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casasola, R.; Thomas, N.L.; Trybala, A.; Georgiadou, S. Electrospun Poly Lactic Acid (PLA) Fibres: Effect of Different Solvent Systems on Fibre Morphology and Diameter. Polymer 2014, 55, 4728–4737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabulut, H.; Unal, S.; Ulag, S.; Ficai, A.; Ficai, D.; Gunduz, O. Mapping the Influence of Solvent Composition over the Characteristics of Polylactic Acid Nanofibers Fabricated by Electrospinning. ChemistrySelect 2024, 9, e202301142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tundo, P.; Selva, M. The Chemistry of Dimethyl Carbonate. Acc. Chem. Res. 2002, 35, 706–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyo, S.-H.; Park, J.H.; Chang, T.-S.; Hatti-Kaul, R. Dimethyl Carbonate as a Green Chemical. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2017, 5, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldal, D.G.; Topuz, F.; Holtzl, T.; Szekely, G. Green Electrospinning of Biodegradable Cellulose Acetate Nanofibrous Membranes with Tunable Porosity. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 994–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Parize, D.D.; de Oliveira, J.E.; Foschini, M.M.; Marconcini, J.M.; Mattoso, L.H.C. Poly(Lactic Acid) Fibers Obtained by Solution Blow Spinning: Effect of a Greener Solvent on the Fiber Diameter. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2016, 133, 43379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva Parize, D.D.; Foschini, M.M.; De Oliveira, J.E.; Klamczynski, A.P.; Glenn, G.M.; Marconcini, J.M.; Mattoso, L.H.C. Solution Blow Spinning: Parameters Optimization and Effects on the Properties of Nanofibers from Poly(Lactic Acid)/Dimethyl Carbonate Solutions. J. Mater. Sci. 2016, 51, 4627–4638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado-Illescas, M.D.P.; Casares-López, J.M.; González-Martín, M.L.; Gallardo-Moreno, A.M.; Luque-Agudo, V. Toward Sustainable PLA Films by Replacing Chloroform for the Green Solvent Dimethyl Carbonate. Surf. Interfaces 2025, 59, 105843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capello, C.; Fischer, U.; Hungerbühler, K. What Is a Green Solvent? A Comprehensive Framework for the Environmental Assessment of Solvents. Green Chem. 2007, 9, 927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciarleglio, G.; Toto, E.; Laurenzi, S.; Santonicola, M.G. Biocompatible PLA/nHAp Coatings for Titanium Implants Fabricated by Green Electrospinning. MRS Commun. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olejnik, O.; Masek, A. Bio-Based Packaging Materials Containing Substances Derived from Coffee and Tea Plants. Materials 2020, 13, 5719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friné, V.-C.; Hector, A.-P.; Manuel, N.-D.S.; Estrella, N.-D.; Antonio, G.J. Development and Characterization of a Biodegradable PLA Food Packaging Hold Monoterpene–Cyclodextrin Complexes against Alternaria Alternata. Polymers 2019, 11, 1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coltelli, M.-B.; Bertolini, A.; Aliotta, L.; Gigante, V.; Vannozzi, A.; Lazzeri, A. Chain Extension of Poly(Lactic Acid) (PLA)–Based Blends and Composites Containing Bran with Biobased Compounds for Controlling Their Processability and Recyclability. Polymers 2021, 13, 3050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Topuz, F.; Park, S.-H.; Szekely, G. Biobased Thin-Film Composite Membranes Comprising Priamine–Genipin Selective Layer on Nanofibrous Biodegradable Polylactic Acid Support for Oil and Solvent-Resistant Nanofiltration. Green Chem. 2022, 24, 5291–5303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingeo Biopolymer 3251D Technical Data Sheet. Available online: https://www.natureworksllc.com/~/media/Files/NatureWorks/Technical-Documents/Technical-Data-Sheets/TechnicalDataSheet_3251D_injection-molding_pdf.pdf (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Ingeo Biopolymer 4043D Technical Data Sheet. Available online: https://www.natureworksllc.com/~/media/Technical_Resources/Technical_Data_Sheets/TechnicalDataSheet_4043D_films_pdf.pdf (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Luminy LX175 Technical Data Sheet. Available online: https://totalenergies-corbion.com//wp-content/uploads/2025/02/pds-luminy-lx175-20220722.pdf (accessed on 24 December 2025).

- Ciarleglio, G.; Russo, T.; Vella, S.; Toto, E.; Santonicola, M.G. Electrospray Fabrication of pH-Responsive Microspheres for the Delivery of Ozoile. Macromol. Symp. 2024, 413, 2400031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciarleglio, G.; Pagani, L.; Ferri, L.; Toto, E.; Santonicola, M.G. Nanofibrous Coatings of Poly(Lactic Acid) and Nano-Hydroxyapatite for Enhanced Biocompatibility of Titanium Implants. Macromol. Symp. 2025, 414, e70248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Xia, Y. Electrospinning of Nanofibers: Reinventing the Wheel? Adv. Mater. 2004, 16, 1151–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, R.; Turcott, A.; Banuelos, L.; Dowey, E.; Goodwin, B.; Cardinal, K.O. SIMPoly: A Matlab-Based Image Analysis Tool to Measure Electrospun Polymer Scaffold Fiber Diameter. Tissue Eng. Part C Methods 2020, 26, 628–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ASTM E1356-08; Standard Test Method for Assignment of the Glass Transition Temperatures by Differential Scanning Calorimetry. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2014.

- Ciarleglio, G.; Pagani, L.; Toto, E.; Laurenzi, S.; Santonicola, M.G. Electrospun PLA/Nano-Hydroxyapatite Fiber Coatings for Improved Corrosion Protection of Titanium Implants. Surf. Interfaces 2025, 76, 107848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández Sánchez, F.; Molina Mateo, J.; Romero Colomer, F.J.; Salmerón Sánchez, M.; Gómez Ribelles, J.L.; Mano, J.F. Influence of Low-Temperature Nucleation on the Crystallization Process of Poly(l-Lactide). Biomacromolecules 2005, 6, 3283–3290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Tashiro, K.; Tsuji, H.; Domb, A.J. Disorder-to-Order Phase Transition and Multiple Melting Behavior of Poly(l-Lactide) Investigated by Simultaneous Measurements of WAXD and DSC. Macromolecules 2008, 41, 1352–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puchalski, M.; Kwolek, S.; Szparaga, G.; Chrzanowski, M.; Krucińska, I. Investigation of the Influence of PLA Molecular Structure on the Crystalline Forms (α’ and α) and Mechanical Properties of Wet Spinning Fibres. Polymers 2017, 9, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, C.; Azagury, A.; Baker, C.M.; Mathiowitz, E. The Characterization and Quantification of the Induced Mesophases of Poly-l-Lactic Acid. Polymer 2021, 226, 123822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoclet, G.; Seguela, R.; Lefebvre, J.M.; Elkoun, S.; Vanmansart, C. Strain-Induced Molecular Ordering in Polylactide upon Uniaxial Stretching. Macromolecules 2010, 43, 1488–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoclet, G.; Seguela, R.; Lefebvre, J.-M.; Rochas, C. New Insights on the Strain-Induced Mesophase of Poly(d,l-Lactide): In Situ WAXS and DSC Study of the Thermo-Mechanical Stability. Macromolecules 2010, 43, 7228–7237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoclet, G.; Seguela, R.; Vanmansart, C.; Rochas, C.; Lefebvre, J.-M. WAXS Study of the Structural Reorganization of Semi-Crystalline Polylactide under Tensile Drawing. Polymer 2012, 53, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezabeigi, E.; Wood-Adams, P.M.; Drew, R.A.L. Isothermal Ternary Phase Diagram of the Polylactic Acid-Dichloromethane-Hexane System. Polymer 2014, 55, 3100–3106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rissanen, M.; Puolakka, A.; Nousiainen, P.; Kellomäki, M.; Ellä, V. Solubility and Phase Separation of Poly(L,D-Lactide) Copolymers. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2008, 110, 2399–2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, P.X. Biomimetic Materials for Tissue Engineering. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2008, 60, 184–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thammawong, C.; Buchatip, S.; Petchsuk, A.; Tangboriboonrat, P.; Chanunpanich, N.; Opaprakasit, M.; Sreearunothai, P.; Opaprakasit, P. Electrospinning of Poly(l-Lactide-Co-Dl-Lactide) Copolymers: Effect of Chemical Structures and Spinning Conditions. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2014, 54, 472–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megelski, S.; Stephens, J.S.; Chase, D.B.; Rabolt, J.F. Micro- and Nanostructured Surface Morphology on Electrospun Polymer Fibers. Macromolecules 2002, 35, 8456–8466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lim, C.T.; Ramakrishna, S.; Huang, Z.-M. Recent Development of Polymer Nanofibers for Biomedical and Biotechnological Applications. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2005, 16, 933–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadas, D.; Nagy, Z.K.; Csontos, I.; Marosi, G.; Bocz, K. Effects of Thermal Annealing and Solvent-Induced Crystallization on the Structure and Properties of Poly(Lactic Acid) Microfibres Produced by High-Speed Electrospinning. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2020, 142, 581–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarani, E.; Pušnik Črešnar, K.; Zemljič, L.F.; Chrissafis, K.; Papageorgiou, G.Z.; Lambropoulou, D.; Zamboulis, A.N.; Bikiaris, D.; Terzopoulou, Z. Cold Crystallization Kinetics and Thermal Degradation of PLA Composites with Metal Oxide Nanofillers. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 3004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarus, B.K.; Mwasiagi, J.I.; Fadel, N.; Al-Oufy, A.; Elmessiry, M. Electrospun Cellulose Acetate and Poly(Vinyl Chloride) Nanofiber Mats Containing Silver Nanoparticles for Antifungi Packaging. SN Appl. Sci. 2019, 1, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarus, B.K.; Fadel, N.; Al-Oufy, A.; El-Messiry, M. Investigation of Mechanical Properties of Electrospun Poly (Vinyl Chloride) Polymer Nanoengineered Composite. J. Eng. Fibers Fabr. 2020, 15, 1558925020982569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawal, A.; Singh, D.; Maurya, A.; Szenti, I.; Kukovecz, A.; Kudisonga, C.; Heitzmann, M. Tensile Strength of Continuous and Disordered Fibrous Mats: A Tale of Two-Length Scales. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2025, 46, 2400943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Grade | Mw [kg/mol] | MFI [g/10 min] | D-Lactide Content [%] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3251D | 55–90 | 80 | 1.2 |

| 4043D | 200 | 6 | 4.3 |

| LX 175 | 160–200 | 6 | 4 |

| Test ID | Solution ID | PLA [wt%] | AC [wt%] | DMC [wt%] | DMC/AC Weight Ratio | Viscosity [cP] | Voltage [kV] | Flow Rate [mL/h] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 14 | 9.0 | 45.5 | 45.5 | 1.0 | 155.5 ± 0.2 | 15 | 0.5 |

| 2 | 20 | 0.5 | ||||||

| 3 | 10 | 0.5 | ||||||

| 4 | 10 | 1 | ||||||

| 5 | 15 | 1 | ||||||

| 6 | 20 | 1 | ||||||

| 13 | 28 | 10.9 | 29.4 | 59.7 | 2.0 | 310.6 ± 0.3 | 12.5 | 1 |

| 14 | 12.5 | 0.5 | ||||||

| 15 | 10 | 0.25 | ||||||

| 17 | 20 | 0.25 | ||||||

| 18 | 20 | 0.5 | ||||||

| 19 | 20 | 1 |

| Sample | Tg (°C) * | ΔCp (J/g°C) * | Tcc (°C) | ∆Hc (J/g) | Tm (°C) | ∆Hm (J/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLA PELLET | 64.79 ± 0.22 | 0.50 ± 0.18 | - | - | 180.68 ± 1.58 | 40.84 ± 3.54 |

| PLA NF | 61.84 ± 0.60 | 0.559 ± 0.045 | 103.33 ± 1.42 | 11.45 ± 1.18 | 154.06 ± 0.02 | 22.88 ± 1.04 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pini, T.; Ciarleglio, G.; Toto, E.; Santonicola, M.G.; Valente, M. A Green Binary Solvent System for the PLA Nanofiber Electrospinning Process: Optimization of Parameters. Fibers 2026, 14, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/fib14010006

Pini T, Ciarleglio G, Toto E, Santonicola MG, Valente M. A Green Binary Solvent System for the PLA Nanofiber Electrospinning Process: Optimization of Parameters. Fibers. 2026; 14(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/fib14010006

Chicago/Turabian StylePini, Tommaso, Gianluca Ciarleglio, Elisa Toto, Maria Gabriella Santonicola, and Marco Valente. 2026. "A Green Binary Solvent System for the PLA Nanofiber Electrospinning Process: Optimization of Parameters" Fibers 14, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/fib14010006

APA StylePini, T., Ciarleglio, G., Toto, E., Santonicola, M. G., & Valente, M. (2026). A Green Binary Solvent System for the PLA Nanofiber Electrospinning Process: Optimization of Parameters. Fibers, 14(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/fib14010006