Abstract

Human health is profoundly influenced by external factors, with stress being a primary contributor. In this context, the digestive system is particularly susceptible. The prevalence of diseases affecting the small intestine and colon is increasing. Consequently, insoluble plant fibers, such as cellulose and hemicellulose, play a crucial role in promoting intestinal transit and maintaining colon health. Lettuce is a widely consumed leafy vegetable with high nutritional value and has been intensively studied through hydroponic cultivation. This study aims to optimize the cultivation conditions and freeze-drying process of Lugano and Carmesi lettuce varieties (Lactuca sativa L.) by identifying the optimal growth conditions, freeze-drying duration, and sample surface area in order to achieve an optimal percentage of insoluble fibers. Carmesi and Lugano varieties were selected based on their contrasting growth characteristics and leaf morphology, allowing to assess whether treatments and processing conditions have consistent effects on different types of lettuce. The optimal freeze-drying parameters were determined to include a 48 h freeze-drying period, a maximum sample surface area of 144 cm2, and growth under combined conditions of supplementary oxygenation and LED light exposure. The optimal fiber composition, cellulose (21.61%), hemicellulose (11.84%) and lignin (1.36%), was found for the Lugano variety, which exhibited lower lignin and higher cellulose contents than the Carmesi variety. The quantification of hemicellulose, cellulose and lignin was performed using the well-known NDF, ADF and ADL methods. Therefore, optimized freeze-dried lettuce powder, particularly from the Lugano variety, presents a high-value functional ingredient for enriching foods and developing nutritional supplements aimed at digestive health.

Keywords:

lettuce; fibers; cellulose; hemicellulose; lignin; freeze-drying; response surface methodology 1. Introduction

Dietary fiber plays an essential role in maintaining a balanced diet, with a significant contribution to digestive health and gut function. In modern diets, which are increasingly dominated by highly processed foods, adequate fiber intake has become a critical factor in preventing digestive system disorders, including constipation, impaired blood glucose regulation, and dyslipidemia. Both soluble and insoluble dietary fibers contribute to these protective effects, supporting intestinal transit and interacting with the gut microbiota to promote metabolic homeostasis [1]. In this context, fruits and vegetables represent accessible and sustainable dietary sources of fiber, particularly when they also provide bioactive compounds with additional health benefits. Lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) is one of the most widely consumed leafy vegetables by the European population; however, its production has been increasingly affected by climate change, resulting in a marked decline in yield and export volumes in recent years [2]. Despite having a lower total fiber content compared to some other vegetables [3], lettuce remains of interest due to its widespread consumption and its richness in phytochemicals, including phenolic compounds, carotenoids (particularly xanthophylls), and chlorophyll, which exhibit antidiabetic, anti-inflammatory, hepatoprotective, antimicrobial, anti-obesity, antiproliferative, antiviral, and anticancer activities [4]. In addition, lettuce provides essential vitamins (C, E, folate) and minerals (Na, K, Ca, Zn, Fe, P, Mg), supporting its role in a balanced diet.

From a structural perspective, the insoluble fraction of dietary fiber—composed mainly of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin—plays a key role in stimulating intestinal transit and maintaining gastrointestinal health. The content and composition of these insoluble fibers, as well as that of bioactive compounds, are strongly influenced by cultivation conditions. Lettuce can be grown using various systems, including soil-based cultivation, greenhouse systems, and soilless techniques such as nutrient film technique (NFT), deep water culture (DWC), ebb-and-flow technique, and aeroponics [5,6,7]. Beyond the cultivation system itself, environmental factors such as CO2 concentration, dissolved oxygen availability, and light characteristics (spectrum and intensity) have been shown to influence plant growth and nutritional quality, including fiber-related parameters [8,9]. For example, Ali et al. [10] demonstrated that continuous and pulsed LED lighting significantly affected the yield and nutritional composition of lettuce, while Ouyang et al. [11] reported that variations in dissolved oxygen concentration and temperature altered growth, photosynthesis, yield, and quality attributes of L. sativa.

Beyond its role as a fresh vegetable, lettuce holds significant potential for valorization as a functional food ingredient. The growing demand for clean-label and health-promoting products has increased interest in natural sources of dietary fiber for food enrichment [12]. Fiber-rich plant powders can enhance the nutritional value of foods while also improving functional properties such as water retention, viscosity, and structural stability [13]. Moreover, the development of such ingredients from underutilized plant biomass aligns with circular economy principles, enabling the transformation of agricultural products into value-added supplements and functional ingredients [14]. In this context, freeze-drying represents a particularly suitable post-harvest processing method, as it preserves thermolabile nutrients, bioactive compounds, and the structural integrity of plant cell walls more effectively than conventional drying techniques [15,16,17].

While numerous studies have examined the influence of cultivation conditions on the phytochemical profile of lettuce, a notable research gap exists regarding the systematic evaluation and optimization of post-harvest freeze-drying parameters in relation to the insoluble fiber fraction. Importantly, although dietary fiber is often discussed as a whole, the present study focuses exclusively on insoluble dietary fiber, namely cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin. In this work, different cultivation strategies (natural oxygenation, supplementary oxygenation, and supplementary oxygenation combined with LED illumination) were evaluated and integrated as categorical factors within an optimization framework targeting the freeze-drying process. Response Surface Methodology (RSM) was employed to model and optimize the combined effects of lettuce variety, cultivation conditions, and key freeze-drying parameters (drying duration and sample surface area) on the composition of insoluble fibers. The novelty of this study lies in this integrated approach, which links pre-harvest cultivation strategies with post-harvest processing optimization to obtain a characterized, fiber-rich lettuce powder with potential applications as a natural functional ingredient for digestive health.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Obtaining the Plant Material

The plant material used in this study comes from the University of AgronomicSciences and Veterinary Medicine of Bucharest (Bucharest, Romania). It consisted of two lettuce (L. sativa L.) varieties: Lugano RZ (Lollo Bionda) and Carmesi RZ (Lollo Rossa). These varieties were cultivated in a nutrient film technique (NFT) system under three different conditions: natural oxygenation (NO), supplementary oxygenation (SO), and a combination of LED illumination with supplementary oxygenation (LED + SO). The LED illumination covered a wavelength range of 380–840 nm, with blue (450 nm) and red (660 nm) light provided at a 50:50 ratio. The photoperiod was 14 h of light per day, and the PPFD of the supplemental light was in the range of 460–500 µmol m−2 s−1. The dissolved oxygen concentration in the supplementary oxygenation treatment ranged from 8.1 to 9.0 mg/L, and from 6.8 to 7.8 mg/L in the natural oxygenation treatment for both varieties. The pH of water was 6.9 to optimize nutrient uptake. The nutrient solution consisted of nitrate-based fertilizers, complemented with MKP and providing a balanced supply for macro- and micronutrients, with an electrical conductivity ranging from 2.3 to 3.2 mS/cm. The germination period was approximately 5 days after sowing, and the lettuce plant was cultivated in NFT cycle for 40 days. The maximum and minimum temperatures were 21 °C (day) and 15 °C (night). The average RH% during growth was 57.41 ± 1.02%. Harvesting the lettuce at maturity involved cutting the heads, washing them with distilled water, cutting them into pieces, and storing them at −80 °C until the next step. Following harvest, washing and freezing, the plant material was subjected to freeze-drying and subsequently analyzed for the targeted parameters (hemicellulose, cellulose and lignin content). For the lettuce growth trial, at each treatment applied (NO, SO and LED + SO), the number of replicates was ten.

2.2. Freeze-Drying of Plant Material—Optimization Process

The freeze-drying of plant material was performed with an emphasis on optimizing the process parameters. The freeze-drying was carried out using a Christ LyoCube 4-8 LSC plus unit (Martin Christ, Osterode am Harz, Germany-EU). To optimize the freeze-drying conditions, two key variables were monitored: the total duration of the process and the exposed surface area of the plant material. Each head of lettuce was washed with distilled water, the leaves were cut from the head and chopped and stored at −80 °C for freeze-drying. Each tray contained 25 g of chopped lettuce leaves. The lettuce leaves taken for freeze-drying and then analyzed were randomly selected from the ten replicates for each treatment applied. The selected leaves were mature and fully expanded, located in the middle section of the plant. The vacuum level during principal drying varied between 0.5 and 1 mbar, the temperature in the sample chamber was −55 °C, and the condenser temperature was maintained at approximately −85 °C during the freeze-drying process. After freeze-drying, lettuce samples corresponding to each treatment were pooled and homogenized to obtain a representative composite sample, which was subsequently used for insoluble dietary fiber analysis.

2.3. Experimental Methodology—Response Surface Methodology (RSM)

In the present study, RSM was employed to optimize the responses corresponding to hemicellulose, cellulose and lignin content. A randomized experimental design was implemented, involving four independent variables (two numerical and two categorical) and three dependent variables, resulting in a total of 22 experimental runs for the quadratic model.

The optimization of lettuce cultivation conditions and freeze-drying process was conducted using the software package Design Expert 13.0.5.0. (State-Ease Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA), involving a D-optimal point exchange design type. The objective was to identify the optimal conditions for maximizing cellulose and hemicellulose content and minimizing lignin content in the plant material. The four independent variables considered were: freeze-drying duration (48, 60, and 72 h), sample surface area (49, 96.5, and 144 cm2), lettuce variety (‘Carmesi’ vs. ‘Lugano’), and cultivation method (NO, SO, LED + SO). The coding and levels of the independent variables are presented in Table 1. Second-order polynomial models were developed to describe the relationships between the responses and the experimental factors.

Table 1.

Independent variables: levels and coding.

2.4. Fiber Content Analysis (NDF, ADF, ADL)

The analysis of dietary fiber content involved determining the levels of neutral detergent fiber (NDF), acid detergent insoluble fiber (ADF) and acid detergent lignin (ADL). These parameters were measured using a Velp Scientifica SA30520200 FIWE 6 Fiber Analyzer (Interworld Highway, LLC, Long Branch, NJ, USA). The analytical procedure followed the methods developed by Van Soest [18], which are widely recognized for accurately determining the fiber fractions of plant material. For each determination (ADF, NDF, ADL), P2 glass crucibles with pore size 40–100 microns were used, in which 1 g of crushed sample, passed through a 1 mm sieve, was weighed.

The NDF fraction was obtained using a hydrolyzing method based on neutral detergent solutions, including neutral sodium lauryl sulfate (C12H25NaO4S), disodium ethylenediaminetetraacetate (EDTA), sodium borate decahydrate (Na2B4O7·10H2O), disodium phosphate anhydrous (Na2HPO4), and anhydrous sodium sulfite (Na2SO3). The samples were maintained at reflux for 60 min from the start of boiling, subjected to filtration and washing (boiled water and acetone) and dried for 8 h at 105 °C.

The ADF and ADL fractions were determined according to the official methods AOAC 973.18 and ISO 13906:2008, respectively. The ADF fraction was obtained by digestion in the presence of an acid detergent solution containing cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (C19H42BrN) and sulfuric acid 1N. As in the case of NDF, the samples were maintained at reflux for 60 min from the start of boiling, subjected to filtration and washing (boiled water and acetone) and dried for 8 h at 105 °C.

The ADL fraction is based on the solubilization of cellulose with 72% sulfuric acid. In this process, after being maintained at reflux for 60 min from the start of boiling for digestion with detergent acid solution, filtration and washing (boiled water and acetone), the samples were subjected to cold extraction with 72% sulfuric acid for 3 h, stirring every hour. After this step, the samples were filtered, washed (boiled water and acetone) and dried for 8 h at 105 °C.

Accordingly, the hemicellulose, cellulose and lignin contents were calculated using the following formulas:

Hemicellulose (%) = NDF − ADF

Celullose (%) = ADF − ADL

Lignin (%) = ADL

2.5. FTIR Fiber Analysis

Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy was employed to identify the functional groups associated with hemicellulose, cellulose, and lignin in the lettuce samples following NDF extraction. The analyses were performed using an FTIR-ATR (QATR-10) spectrometer (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). Spectra were recorded over a wavelength range of 4000–400 cm−1, with 64 scans acquired per sample at a nominal resolution of 4 cm−1.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

All experiments were performed using biological replicates, with ten lettuce heads per cultivation treatment. Data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Response Surface Methodology (RSM) was applied to evaluate the combined effects of cultivation conditions, lettuce variety, freeze-drying duration, and sample surface area on insoluble dietary fiber composition. Model significance and factor effects were assessed using analysis of variance (ANOVA). Differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05. The adequacy of the models was evaluated using coefficients of determination (R2, adjusted R2, predicted R2) and lack-of-fit tests. Statistical analysis and model generation were performed using Design-Expert software (Version 13, State-Ease Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Effect of Freeze-Drying Process on the Fiber Content of Lettuce

To investigate the influence of various technological parameters in lettuce cultivation and freeze-drying process (freeze-drying duration, sample surface area, lettuce variety and cultivation method) on the content of hemicellulose, cellulose and lignin in lettuce, an experimental design based on response surface methodology (RSM) was employed, including both numerical and categorical factors. The results obtained varied according to these independent variables. Table 2 presents the experimental design along with the corresponding responses. The experiment was structured as a randomized design for RSM, comprising 22 runs.

Table 2.

Experimental design.

The experiments led to hemicellulose content ranging from 7.74 to 11.47%, lignin content ranging from 0.88 to 6.66%, and cellulose content from 16.41 to 20.65%, with all values expressed as percentages of dry mass.

3.2. Statistical Analysis and Validation of the RSM Model for Fiber Content in Lettuce

To optimize the fiber content in lettuce samples grown using different cultivation methods (NO, SO and LED + SO), quadratic models were developed for each response variable using RSM, based on a customized experimental design. Subsequently, analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed for the quadratic models, and the results obtained are summarized in Table 3, including F and p-values, as well as R2, adjusted R2 and predicted R2 for each response variable.

Table 3.

ANOVA of quadratic models.

As shown, the model F-value for lignin, hemicellulose and cellulose indicates that the models are significant, with only a 0.01% probability that an F-value this large could occur due to random error. Furthermore, p-values less than 0.05 denote significant model terms. Specifically, for lignin, the significant terms are A, B, D, A2 and B2; for hemicellulose, they are A, B, D, AB, AD and B2; and for cellulose, they are A, B, C, D, AB, AD, BD, and B2.

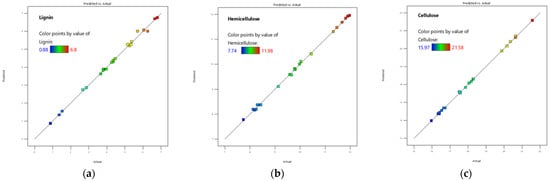

Regression analysis demonstrated that the predicted values closely fitted the experimental results, with R2 coefficients exceeding 0.99 for all models. The Predicted R2 values were in reasonable agreement with the Adjusted R2 values, indicating strong predictive ability. Adequate Precision, which measures the signal-to-noise ratio, confirmed that each model had an adequate signal. To illustrate this, Figure 1 presents plots of predicted versus actual values for the studied responses.

Figure 1.

Predicted versus actual response values for (a) lignin, (b) hemicellulose and (c) cellulose.

To make predictions for specific factor levels, the model equations must be used. The coded equations, expressed in terms of coded factors, are presented in Table 4, allowing the relative impact of each factor to be assessed by comparing the coefficients.

Table 4.

Model equations expressed in coded factors.

3.3. Evaluation and Validation of Optimal Freeze-Drying Conditions

To validate the RSM models and the identified optimal freeze-drying conditions, the lignin, cellulose and hemicellulose content were re-analyzed. The experimental values for these dependent variables were compared with the values statistically predicted under the optimal conditions. By aiming to minimize freeze-drying duration and lignin content, while maximizing the sample surface area, cellulose and hemicellulose content, the optimal conditions were determined (Table 5), with a desirability function of 0.988.

Table 5.

Optimal condition for the freeze-drying process.

The results confirm the effectiveness of applying quadratic models through statistical approaches to optimize the freeze-drying process, taking into account the plant characteristics and its cultivation method, in order to achieve the targeted fiber content in lettuce. A critical finding was the significantly superior performance of the Lugano variety over the Carmesi one. The statistical models consistently identified the variety as a significant factor, with Lugano yielding a more favorable fiber profile, higher in cellulose and lower in lignin, across comparable processing and cultivation conditions. This establishes Lugano as the unequivocal variety of choice for producing a high-quality fiber ingredient. Furthermore, the simultaneous application of supplementary oxygenation and LED lighting (LED + SO) during cultivation proved more effective than the other two methods, namely natural oxygenation (NO) or supplementary oxygenation alone (SO).

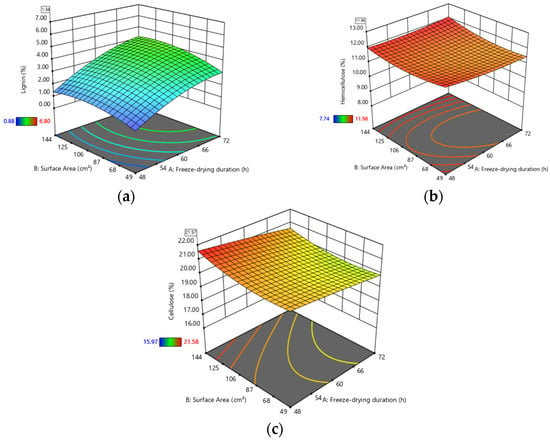

3.4. Response Surface Analysis (3D Response Surface Plots) for RSM Models

To visually assess the interaction between the independent variables and their combined effects on the studied responses, 3D response surface plots were generated using the Design Expert software package, based on the quadratic RSM models described above. The 3D representations are shown in Figure 2, corresponding to the optimal solution for the Lugano lettuce variety cultivated with simultaneous LED + SO application.

Figure 2.

3D plots of responses as a function of freeze-drying duration and sample surface area for (a) lignin, (b) hemicellulose and (c) cellulose.

It should be acknowledged that the experimental domain was constrained by practical and operational considerations, and therefore, the identified optimum reflects the best achievable conditions within the predefined design space rather than an absolute global optimum.

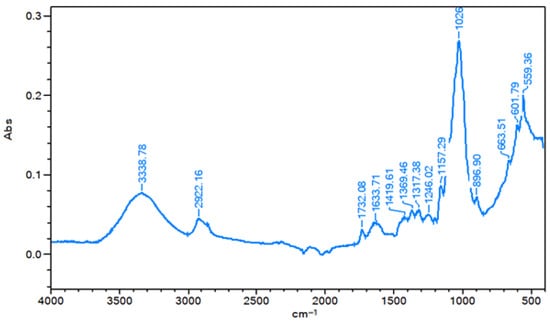

3.5. FTIR Analysis of Lettuce Fibers

Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy was performed to identify the functional groups associated with lignin, hemicellulose, and cellulose in lettuce. The FTIR spectrum of the freeze-dried sample obtained under optimal process conditions (see Table 5) is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

FTIR spectrum of lettuce freeze-dried under optimal process conditions.

As observed, the spectrum recorded in the range of 4000–400 cm−1 exhibits characteristic absorption bands corresponding to cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin. These bands were identified by comparing the absorption peaks obtained for the Lugano lettuce sample under optimal conditions with those reported in the literature [19,20,21,22].

For cellulose, the bands at 3338.78 cm−1 and 2922.16 cm−1 are attributed to O-H and C-H stretching vibrations, respectively. Additionally, the bands at 1157.29 cm−1, 1026 cm−1, and 896.9 cm−1 can be assigned to C-O-C stretching and glycosidic bond vibrations in cellulose. Furthermore, the band at 1419.61 cm−1 corresponds to CH2 scissoring vibrations, while the band at 1369.46 cm−1 is associated with aliphatic C-H bending.

In contrast, the band at 1732.08 cm−1 can be attributed to the C=O stretching vibration of alkyl esters, characteristic of acetylated hemicellulose. The band at 1246.02 cm−1 corresponds to C-O-C or C-O stretching vibrations, while the band at 1026 cm−1 is associated with C-O-H vibrations in carbohydrates, also indicative of hemicellulose. Furthermore, the band at 1633.71 cm−1 may also reflect the contribution of hemicellulose in this region.

Lignin was identified by several characteristic absorption bands. The band at 1419.61 cm−1 is associated with C=O stretching and C-C skeletal vibrations of the aromatic ring, combined with asymmetric C-H in-plane bending vibrations in O-CH3 groups. The band at 1369.46 cm−1 corresponds to symmetrical C-H bending vibrations in CH3 groups and O-H in-plane bending vibrations in phenolic structures. The bands at 1317.38 cm−1 and 1246.02 cm−1 are attributed to skeletal vibrations of the syringyl and condensed guaiacyl ring, asymmetric stretching vibrations of the CAr-O-C linkage, and C-O stretching vibrations in phenolic compounds. Additionally, the bands at 1026 cm−1 can be assigned to C-O vibrations of phenols as well as C-H in-plane bending vibrations of the syringyl and guaiacyl rings. The band 896.90 cm−1 corresponds to out-of-plane C-H bending vibrations of the aromatic ring. Finally, the band at 1633.71 cm−1 can also be associated with lignin, reflecting aromatic C=C vibrations of the phenylpropanoid ring.

4. Discussion

This study successfully employed RSM to optimize the cultivation conditions and freeze-drying process of lettuce, demonstrating a viable pathway to maximize its value as a source of insoluble dietary fiber. The utilization of lettuce, whether for human consumption, animal feed, composting or biogas production, involves the presence of insoluble fibers such as cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin, each playing multiple roles, whose importance varies depending on the specific application. Cellulose, the predominant structural polysaccharide in plant cell walls, contributes to human nutrition by facilitating intestinal transit and promoting a feeling of satiety. Hemicellulose, also a polysaccharide, is more readily fermentable than cellulose and may serve a prebiotic function in the human colon. In contrast, lignin, a complex phenolic polymer, is largely undigested in the human upper gastrointestinal tract and does not provide metabolic energy. However, it contributes to the textural integrity of the plant material.

It should be emphasized that freeze-drying does not induce chemical conversion of cellulose, hemicellulose, or lignin; therefore, the observed variations in insoluble dietary fiber composition reflect relative differences expressed on a dry-weight basis, rather than true biochemical transformations. These apparent differences can be attributed to variations in tissue structure, moisture distribution, matrix porosity, and particle size after grinding, which may influence the efficiency of fiber fraction recovery during NDF, ADF, and ADL analysis.

Although the freeze-drying process entails higher operational costs compared to conventional methods, it was selected for its unparalleled advantages in preserving thermolabile compounds and the microstructural integrity of plant materials [23,24]. Unlike conventional drying techniques (e.g., oven, sun, or microwave drying), which can degrade bioactive components and alter physical properties, freeze-drying operates at low temperatures under vacuum. This is critical for preventing the degradation of fibrous structures and preserving the functionality of dietary fibers. For instance, in the case of wheatgrass, freeze-drying was more effective than shade and oven drying in retaining chlorophyll, flavonoids, saponins and antioxidant activity [25]. Similarly, a study on the leaves of pumpkin (Cucurbita moschata Duchesne ex Poir, var. Butternut squash) demonstrated that freeze-drying is superior to oven, sun, solar, and microwave drying in preserving color, pigments, phenolic metabolites, in vitro antioxidant activity, and antidiabetic properties [26]. Moreover, freeze-drying has been shown to be highly effective in long-term preservation of plant materials, maintaining minerals and vitamins in kale leaves [27].

While the potential of plant-derived insoluble fibers for biopolymer preparation is well-documented in the literature [13,28,29], their specific role in supporting human metabolic functions has been less explored. This gap in research has consequently limited their targeted inclusion as functional ingredients in dietary supplements.

In this context, the potential of cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin present in bamboo shoots (with a dietary fiber content of 45.65%) was evaluated as a dietary fiber supplement, demonstrating reductions in triglycerides (TG), blood glucose (GLU), total cholesterol (CHOL), high-density lipoprotein (HDL-C), and low-density lipoprotein (LDL-C) in high-fat diet mice [30].

Furthermore, fibers from lettuce have been shown to reduce intestinal glucose and lipid absorption in an in vitro model [31].

The optimized fiber profile obtained in this study is particularly advantageous for human nutrition. The achieved composition of 21.61% cellulose, 11.84% hemicellulose, and 1.36% lignin is comparable to, and in the case of cellulose, superior to, values reported for other lettuce valorization streams, such as the 17.7% cellulose and 5.2% lignin found in romaine lettuce waste [32]. The low lignin content is a key benefit, as it enhances the overall digestibility and palatability of the fiber-rich powder [30]. This tailored composition makes the optimized Lugano lettuce powder a superior candidate for incorporation into functional foods and nutraceuticals aimed at promoting digestive health. This potential is supported by studies on other plant fibers, such as those from bamboo shoots, which demonstrated hypolipidemic and hypoglycemic effects in vivo [30], and in vitro models showing lettuce fibers’ ability to reduce glucose and lipid absorption [31]. It is crucial to emphasize that this optimal nutritional profile was uniquely and consistently associated with the Lugano variety. For instance, under the optimal LED + SO cultivation and identical freeze-drying parameters, Lugano achieved a final cellulose content of 21.61% and a lignin content of only 1.36%, whereas Carmesi reached only 20.36% cellulose with a significantly higher lignin content of 4.27% (Table 3, Runs 16 vs. 19). This contrast underscores that the choice of cultivar is an important variable in obtaining a high-quality fiber ingredient, with Lugano emerging as the unequivocal candidate for this application.

Consequently, the lettuce biomass processed under our optimized conditions transcends its role as a conventional fresh vegetable. It is repositioned as a high-value functional ingredient, with direct applications as a nutritional supplement or a “superfood” powder. Its tailored fiber profile and natural origin make it an ideal candidate for developing innovative functional foods and nutraceuticals aimed at promoting digestive health and meeting the growing consumer demand for clean-label wellness products.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates a successful strategy for valorizing lettuce into a high-value functional ingredient, aligning with the principles of a circular bioeconomy. By employing Response Surface Methodology, we optimized a freeze-drying process that is both efficient (48 h) and effective, maximizing the yield of beneficial insoluble fibers. A key finding was the identification of the Lugano variety as superior to Carmesi for this purpose, which is a conclusion statistically validated by our models. When cultivated under the resource-efficient nutrient film technique (NFT) enhanced with supplementary oxygenation and LED lighting, the Lugano variety yielded a tailored fiber profile, high in cellulose (21.61%), moderate in hemicellulose (11.84%), and low in lignin (1.36%), ideal for human nutrition. Consequently, this work provides a sustainable framework for transforming an agricultural product into a nutritious “superfood” powder or a functional ingredient, thereby creating new value streams from lettuce production and contributing to sustainable food systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.M.S. and A.O.; methodology, A.S.T. and M.D.C.; software, S.M.S.; validation, A.O. and A.S.T.; formal analysis, S.M.S.; investigation, S.M.S. and C.L.C.; resources, M.D.C.; data curation, A.S.T.; writing—original draft preparation, S.M.S. and A.S.T.; writing—review and editing, A.O.; visualization, M.D.C. and C.L.C.; supervision, A.O. and C.L.C.; project administration, A.O.; funding acquisition, A.S.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

S.M.S., M.D.C., C.L.C. and A.O. gratefully acknowledge the support of the Ministry of Research, Innovation and Digitization (Ministry of Education and Research—National Authority for Research), CCCDI—UEFISCDI, project number PN-IV-P7-7.1-PTE-2024-0607, contract 57PTE/2025, within PNCDI IV. The authors gratefully acknowledge the research funding offered by the University of Agronomic Sciences and Veterinary Medicine of Bucharest—Romania, Internal Research Project 850/30.06.2023.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Martinez, T.M.; Meyer, R.K.; Duca, F.A. Therapeutic Potential of Various Plant-Based Fibers to Improve Energy Homeostasis via the Gut Microbiota. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messe Berlin GmbH. European Statistics Handbook 2024; Messe Berlin: Berlin, Germany, 2024; Available online: https://messe-berlinprod-media.e-spirit.cloud/a1df0db7-5587-490f-b68d-2d8767a5500f/fruit-logistica/downloads-alle-sprachen/european_statistics_handbook_2024.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Shi, M.; Gu, J.; Wu, H.; Rauf, A.; Emran, T.B.; Khan, Z.; Mitra, S.; Aljohani, A.S.M.; Alhumaydhi, F.A.; Al-Awthan, Y.S.; et al. Phytochemicals, Nutrition, Metabolism, Bioavailability, and Health Benefits in Lettuce—A Comprehensive Review. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gontijo, L.N.; da Silva, C.O.; Stort, L.G.; Duarte, R.M.T.; Betanho, C.; Tassi, E.M.M. Nutritional composition of vegetables grown in organic and conventional cultivation systems in Uberlândia, MG. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2017, 12, 1848–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Li, X.; Tang, B.; Gu, M. Growth Responses and Root Characteristics of Lettuce Grown in Aeroponics, Hydroponics, and Substrate Culture. Horticulturae 2018, 4, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kinani, H.A.A.; Jerca, O.I.; Bobuțac, V.; Drăghici, E.M. Comparative Study on Lettuce Growing in NFT and Ebb and Flow System. Sci. Pap. Ser. B Hortic. 2021, 65, 361–368. [Google Scholar]

- Chamoli, N.; Kumar, M.; Das, S.; Prabha, D.; Chauhan, J.S. Comparative Analysis of Hydroponically and Soil-Grown Lettuce. J. Mt. Res. 2024, 19, 583–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeehen, J.D.; Smart, D.J.; Mackowiak, C.L.; Wheeler, R.M.; Nielsen, S.S. Effect of CO2 Levels on Nutrient Content of Lettuce and Radish. Adv. Space Res. 1996, 18, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, L.; Guo, W. Red and Blue Wavelengths Affect the Morphology, Energy Use Efficiency and Nutritional Content of Lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.). Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 8374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Santoro, P.; Ferrante, A.; Cocetta, G. Investigating Pulsed LED Effectiveness as an Alternative to Continuous LED through Morpho-Physiological Evaluation of Baby Leaf Lettuce (Lactuca sativa L. var. Acephala). S. Afr. J. Bot. 2023, 160, 560–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Z.; Tian, J.; Yan, X.; Shen, H. Effects of Different Concentrations of Dissolved Oxygen or Temperatures on the Growth, Photosynthesis, Yield and Quality of Lettuce. Agric. Water Manag. 2020, 228, 105896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasso, S. Extruded snacks from industrial by-products: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 99, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleimanian, Y.; Sanou, I.; Turgeon, S.L.; Canizares, D.; Khalloufi, S. Natural Plant Fibers Obtained from Agricultural Residue Used as an Ingredient in Food Matrixes or Packaging Materials: A Review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2022, 21, 371–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurgilevich, A.; Birge, T.; Kentala-Lehtonen, J.; Korhonen-Kurki, K.; Pietikäinen, J.; Saikku, L.; Schösler, H. Transition towards Circular Economy in the Food System. Sustainability 2016, 8, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsumair, A.; Mlambo, V.; Lallo, C.H.O. Effect of drying method on the chemical composition of leaves from four tropical tree species. Trop. Agric. 2014, 91, 179–186. Available online: https://journals.sta.uwi.edu/ojs/index.php/ta/article/view/932 (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Nawawi, N.I.M.; Ijod, G.; Abas, F.; Ramli, N.S.; Mohd Adzahan, N.; Mohamad Azman, E. Influence of Different Drying Methods on Anthocyanins Composition and Antioxidant Activities of Mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana L.) Pericarps and LC-MS Analysis of the Active Extract. Foods 2023, 12, 2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurčević Šangut, I.; Pavličević, L.; Šamec, D. Influence of Air Drying, Freeze Drying and Oven Drying on the Biflavone Content in Yellow Ginkgo (Ginkgo biloba L.) Leaves. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Soest, P.J.; Robertson, J.B.; Lewis, B.A. Methods for Dietary Fiber, Neutral Detergent Fiber, and Nonstarch Polysaccharides in Relation to Animal Nutrition. J. Dairy Sci. 1991, 74, 3583–3597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wei, Y.; Xu, J.; Xu, N.; He, Y. Quantitative Visualization of Lignocellulose Components in Transverse Sections of Moso Bamboo Based on FTIR Macro- and Micro-Spectroscopy Coupled with Chemometrics. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2018, 11, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canteri, M.H.G.; Renard, C.M.G.C.; Le Bourvellec, C.; Bureau, S. ATR-FTIR Spectroscopy to Determine Cell Wall Composition: Application on a Large Diversity of Fruits and Vegetables. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 212, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javier-Astete, R.; Jimenez-Davalos, J.; Zolla, G. Determination of Hemicellulose, Cellulose, Holocellulose and Lignin Content Using FTIR in Calycophyllum spruceanum (Benth.) K. Schum. and Guazuma crinita Lam. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0256559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostryukov, S.G.; Matyakubov, H.B.; Masterova, Y.Y.; Kozlov, A.S.; Pryanichnikova, M.K.; Pynenkov, A.A.; Khluchina, N.A. Determination of Lignin, Cellulose, and Hemicellulose in Plant Materials by FTIR Spectroscopy. J. Anal. Chem. 2023, 78, 718–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratti, C. Hot air and freeze-drying of high-value foods: A review. J. Food Eng. 2001, 49, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oikonomopoulou, V.P.; Krokida, M.K.; Karathanos, V.T. The Influence of Freeze Drying Conditions on Microstructural Changes of Food Products. Procedia Food Sci. 2011, 1, 647–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, C.B.; Bains, K.; Kaur, H. Effect of Drying Procedures on Nutritional Composition, Bioactive Compounds and Antioxidant Activity of Wheatgrass (Triticum aestivum L.). J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 56, 491–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashitoa, F.M.; Shoko, T.; Shai, J.L.; Slabbert, R.M.; Sultanbawa, Y.; Sivakumar, D. Influence of Different Types of Drying Methods on Color Properties, Phenolic Metabolites and Bioactivities of Pumpkin Leaves of var. Butternut squash (Cucurbita moschata Duchesne ex Poir). Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 694649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korus, A. Effect of Pre-Treatment and Drying Methods on the Content of Minerals, B-Group Vitamins and Tocopherols in Kale (Brassica oleracea L. var. acephala) Leaves. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 59, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, I.; Vargas, J.; Yang, L.; Felfel, R.M. A Review of Natural Fibres and Biopolymer Composites: Progress, Limitations, and Enhancement Strategies. Materials 2024, 17, 4878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, R.; Pathak, L.; Vyas, P. Biobased Polymers of Plant and Microbial Origin and Their Applications—A Review. Biotechnol. Sustain. Mater. 2024, 1, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Wu, L.; Yang, H.; Pan, Y. Using the Major Components (Cellulose, Hemicellulose, and Lignin) of Phyllostachys praecox Bamboo Shoot as Dietary Fiber. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 669136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powthong, P.; Jantrapanukorn, B.; Suntornthiticharoen, P.; Luprasong, C. An In Vitro Study on the Effects of Selected Natural Dietary Fiber from Salad Vegetables for Lowering Intestinal Glucose and Lipid Absorption. Curr. Nutr. Food Sci. 2021, 12, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Salvador, J.L.; Marques, M.P.; Brito, M.S.C.A.; Negro, C.; Monte, M.C.; Manrique, Y.A.; Santos, R.J.; Blanco, A. Valorization of Vegetable Waste from Leek, Lettuce, and Artichoke to Produce Highly Concentrated Lignocellulose Micro- and Nanofibril Suspensions. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 4499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.