Highlights

What are the main findings?

- Cellulose cryogels and aerogels are promising smart hemostatic materials

- Physicochemical and mechanical properties are connected with in vitro tests

- In vivo studies are essential to highly porous cellulose-based scaffolds in biomedicine

What are the implications of the main findings?

- When producing cellulose cryogels and aerogels with optimal hemostatic properties, it is necessary to meet several criteria simultaneously. These include both the properties of the new smart materials themselves and their ability to interact with blood and tissues in living organisms.

Abstract

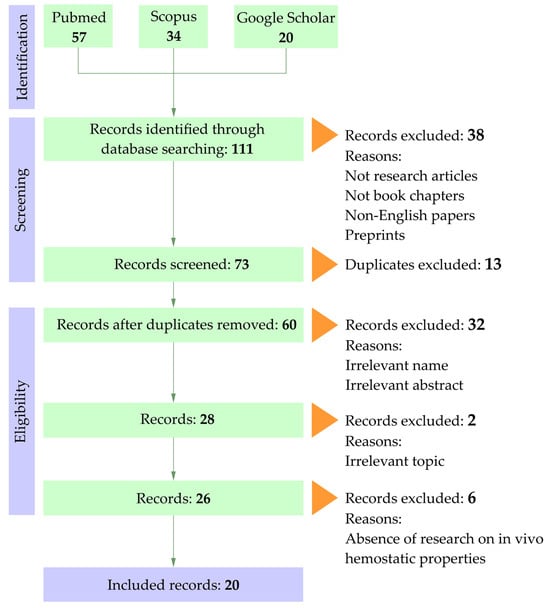

A promising application of smart materials based on natural polymers is the potential to solve problems related to hemostasis in cases of severe bleeding caused by injury or surgery. This can be a life-threatening situation. Cellulose and its modified derivatives represent one of the most promising sources for creating effective hemostatic systems, as well as for various sensing applications related to disease detection, infection diagnosis, chronic condition monitoring, and blood analysis. The aim of this review was to identify key criteria for the efficiency of cellulose-based gels with hemostatic activity. Experimental studies aimed at evaluating new hemostatic devices were analyzed based on international sources using the PRISMA methodology. A total of 111 publications were identified. Following the identification and screening stages, 20 articles were selected for the final qualitative synthesis. The analyzed publications include experimental studies focused on the development and analysis of highly porous cellulose-based scaffolds in the form of aerogels and cryogels. The type and origin of cellulose, as well as the influence of additional components and synthesis conditions on gel formation, were investigated. Three major groups of key criteria that should be considered when developing new cellulose-based highly porous scaffolds with hemostatic functionality were identified: (I) physicochemical and mechanical properties (pore size distribution, compressive strength, and presence of functional groups); (II) in vitro tests (blood clotting index, red blood cell adhesion rate, hemolysis, cytocompatibility, and antibacterial activity); (III) in vivo hemostatic efficiency (hemostasis time and blood loss) in compliance with the 3Rs policy (replacement, reduction, refinement). The prospects for the development of highly porous cellulose-based scaffolds are not only focused on their hemostatic properties, but also on the development of smart platforms.

1. Introduction

Hemostatic agents significantly reduce the negative consequences of injuries and surgical interventions caused by uncompensated blood loss [1,2,3,4]. However, traditional methods of controlling bleeding have several limitations, including side effects, low adhesion, slow hemostasis, or complexity of use [1]. Therefore, medical devices with hemostatic properties must combine safety, high efficiency, versatility, and usability. This is especially important in emergency medicine, where rapid and reliable achievement of hemostasis can save lives [2,5].

Promising sources for the development of hemostatic agents are natural polysaccharides, such as cellulose-based materials [5,6]. Due to their biocompatibility, biodegradability, high blood absorption capacity, cost-effectiveness, and renewability, they represent a component in the development of new hemostatic compositions [3]. Traditional cotton gauze is widely used as a hemostatic material because of its advantages—safety, flexibility, wound conformability, hypoallergenicity, and low cost [5]. However, its limited pro-coagulant activity, insufficient red blood cells adhesion and low platelet activation reduce its clinical hemostatic efficacy [4].

Recently, cellulose derivatives have been widely used in the development of new agents for stopping bleeding [7,8,9]. Purified cellulose undergoes physical treatment (size reduction, nanostructuring) or chemical modification (acetylation and etherification, crosslinking, particle hydrophobization), which significantly improves its properties: increasing surface area, enhancing water retention, and others [3,4,6,7,8]. Materials with hemostatic effects are often obtained by forming complexes from cellulose and sodium alginate salts, starches, or activated biopolymers [5].

The chemical transformation of natural cellulose to produce highly porous scaffolds—aerogels and cryogels—is gaining special popularity. Aerogels are ultra-lightweight porous materials produced by dissolution, solvent exchange, and drying with supercritical CO2 [6]. The preparation of cellulose-based cryogels involves freezing aqueous solutions of amorphized linear polymers or monomers followed by freeze-drying [8]. There are several biomedical studies exploring cellulose and polysaccharide-based cryogels, in which authors note a large and interconnected pore structure that facilitates gas exchange in the wound area, absorbs wound exudate, and simultaneously provides a suitable environment for cell viability [8,10]. Through chemical surface modification, sensing applications based on aerogels and cryogels have been developed to detect specific molecules and bacteria in the bloodstream, which is particularly important for early cancer diagnosis, infection detection, and monitoring chronic conditions such as diabetes [7]. Therefore, cryogels show significant potential for hemostatic agents, wound dressings and applications in regenerative biomedicine and biosensor tissue engineering, enabling advancements in medical diagnostics and treatments [8,9].

Despite the active development of novel hemostatic devices, there is a major issue in selecting evaluation criteria that objectively reflect hemostatic performance. Thus, the objective of this systematic review was to identify key efficiency criteria for highly porous cellulose-based scaffolds exhibiting hemostatic activity. Based on these properties, new materials with additional modifications have the potential to form smart platforms that can combine several properties for use in biomedical applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Method

The PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews guidelines were applied for study selection and data presentation [11]. The literature search was conducted in Scopus, PubMed, and Google Scholar using the following terms and combinations: (“haemosta*” OR “hemosta*”) AND (“platelets” OR “blood” OR “erythrocyte” OR “plasma” OR “RBC”) AND “cellulose” AND (“aerogel” OR “cryogel” OR “xerogel”).

2.2. Paper Selection

All identified studies were screened based on their titles and abstracts. Acceptable articles were experimental studies or book chapters in English. Preprints and duplicates were excluded. Publications were considered if they contained information on the development of cellulose-based aerogels and cryogels, their physicochemical properties, and results from in vitro and in vivo experiments evaluating hemostatic properties. Xerogels are a new type of cellulose modification, but no information has been found regarding their use as a hemostatic agent. Studies that included only one of the selected groups were excluded. The selection flow is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart.

2.3. Data Extraction

Information regarding author affiliations, publication years, study design, raw material sources for aerogel/cryogel preparation, fabrication methodology, physicochemical characterization, hemostatic evaluation approaches, laboratory animal species, and primary outcomes was extracted by one author (N.A.) into an Microsoft Excel 2016 spreadsheet. The data were independently verified by authors (A.R., K.A., L.L.). Disagreements were resolved by consensus or, when required, consultation with a fourth reviewer (A.S.).

3. Results

A total of 111 publications were identified in the databases: Scopus—34, PubMed—57, and Google Scholar—20. Following the identification and screening stages, 20 articles were selected for the final qualitative synthesis (Table 1). The analyzed publications include experimental studies focused on the development and analysis of highly porous cellulose-based scaffolds in the form of aerogels (13 studies) and cryogels (7 studies).

Table 1.

Brief description of highly porous cellulose-based scaffolds.

Aerogels made by supercritical drying with carbon dioxide have low density, small pores, and high specific surface area, with chemical stability against aggressive media. Cryogels, produced through freeze-drying of hydrogels, also have low density but smaller specific surface area and larger pores due to water crystal growth. The methodology of fabrication of aerogels and cryogels is cost-effective and allows control over pore size and shape, enabling tailored properties for specific applications.

Researchers used various types of cellulose for the creation of hemostatic materials. Specifically, samples of plant and bacterial origin, as well as their modifications (TEMPO-oxidized, carbonized, microcrystalline, phosphorylated, carboxymethyl cellulose, hydroxyethyl cellulose), are employed. Notably, Wan et al. (2024) used waste pomelo peel as a cellulose feedstock [15]. In most studies, researchers tend to use plant-derived cellulose due to its widespread availability, accessibility, and ease of modification. Microcrystalline cellulose, as the most common form of polymer, is characterized by high availability and excellent mechanical properties. However, its processing is challenging due to its significant crystallinity, which complicates the production of highly porous structures. To enhance the hydrophilicity and stability of gels, chemical modifications such as carboxymethylation and oxypropylation are necessary, increasing the content of hydroxyl and carboxyl groups that promote swelling. Despite the wide variety of raw materials, the presence of impurities and high processing costs limit reproducibility of research and practically exclude industrial application [31,32].

Bacterial cellulose and nanocellulose are advanced materials in the study of cryogels and aerogels; however, their cost remains high. Bacterial cellulose is easy to sterilize, biocompatible, and suitable for medical applications, but its low content of functional groups hampers surface modification. Nanocellulose’s small fiber size provides a large surface area and high reactivity, facilitating functionalization and blending with polymers, but the complexity of production limits scalability [33].

In many studies, aerogels or cryogels are multi-component systems; instead, auxiliary matrices and modifiers such as chitosan, collagen, gelatin, agar, and alginates are commonly used. Additionally, halloysite, bioactive glass, organic acids, dopamine derivatives, Ag nanoparticles, and zeolites are considered promising components for the formation of cellulose-based composite systems. Chitosan is given particular attention in the development of hemostatic agents due to its high biocompatibility, biodegradability, and ability to actively stimulate blood clotting. It has attractive properties for erythrocytes and platelets, which promotes rapid thrombus formation. Additionally, chitosan has antibacterial properties, reducing the risk of infections when using hemostatic agents and its ability to form gels helps create effective local hemostatic materials [10,25,28].

Parameters for obtaining highly porous cellulose-based scaffolds determine their mechanical and physicochemical properties, including porosity, pore size, and pore size distribution. Particular attention was paid to the initial components (concentration during gelation, type of cellulose used, and its modifications), methods of forming the porous structure (dissolution time, water replacement techniques), parameters for solvent removal, and the type of drying employed. The method of freeze-drying is widely used for the preparation of highly porous cellulosic scaffolds. It involves freezing hydrogels followed by sublimation of water under deep vacuum conditions, bypassing the liquid phase. This process ensures perfect preservation of the initial structure and geometric shape of the materials [8].

An important feature of the examined publications is the multifactorial analysis of variations in scaffolds that differ in the qualitative and quantitative composition of their main components. For example, in the study [20] two types of scaffolds are investigated: nanoporous zeolite-anchored cellulose nanofibers (nZ@CNFs) and Ca2+-exchanged nZ@CNFs (Ca-nZ@CNF). In the research by Cao et al. [24], a complex of carboxymethyl cellulose and dopamine (CMC/DA) with various concentrations of EDC/NHS additives (12.5/6.25, 25/12.5, 50/25, 100/50 mg/mg) is analyzed, as well as CMC/DA enriched with silver (CMC/DA/Ag). It should be noted that in many studies, some of the parameters analyzed are not presented in the main text but are contained in additional files to the articles. Considering the variability in composition and the multi-component nature of the studied samples, analyzing the efficiency of such systems requires a structured approach to classification the criteria used to evaluate hemostatic activity, which formed the basis for the subsequent structuring of results in this review.

4. Discussion

The highly porous scaffolds used in studies of hemostatic properties were predominantly produced via freezing followed by freeze-drying. The freezing stage is a distinct and critical step in the preparation of cryogels, as it determines the growth rate and size of ice crystals, which in turn define the pore size within the material [34]. This method typically results in partial structural collapse and the formation of large pores with a relatively low specific surface area [35,36]. Such effects become particularly evident when water-based solvents are used, as crystallization of solvents with high freezing points promotes the development of large, irregular cavities [37]. In several studies [10,20,21,22,26,27,28,29], aerogels with hemostatic functionality were obtained through freezing and drying techniques consistent with cryogelation. The replacement of water by solvents such as ethanol or methanol, which possess lower freezing points [14,15,17,18], mitigates this effect on pore formation. However, the exposure to low temperatures and vacuum pressure during freeze-drying creates surface tension within the pores, which alters the internal morphology of the scaffolds. These conditions often lead to pore wall thickening and partial collapse, increasing the overall density and decreasing the specific surface area of the resulting material.

Pore size is known to play a crucial role in stimulating vascularization and regulating cellular infiltration, depending on the cell type involved [36,38]. Consequently, insufficient attention to the physicochemical and mechanical characterization of gels limits the understanding of their structure–property relationships and hinders a comprehensive assessment of hemostatic performance. In general, freeze-drying offers significant advantages for obtaining mechanically stable and elastic highly porous materials. The ability to control the freezing rate allows adjustment of pore size and overall porosity [37], which in turn provides optimal conditions for blood contact and blood clot formation [16,39].

Based on the reviewed literature, three primary groups of criteria were identified for assessing cellulose-based hemostatic materials.

4.1. Physicochemical and Mechanical Properties of Cellulose-Based Hemostatic Scaffolds

Most studies include scanning electron microscopy (SEM) or atomic force microscopy (AFM) imaging with analysis of pore size and distribution (Table 2). According to the IUPAC classification, pores are divided into three categories: micropores (<2 nm), mesopores (2–50 nm), and macropores (>50 nm) [40].

Table 2.

Physicochemical and mechanical properties of cellulose-based hemostatic scaffolds.

When it comes to hemostatic materials, special attention is paid to macro- and mesoporous structures, since they largely determine the interaction between the scaffold and blood components. Macropores (>50 nm), which are usually formed during cryogelation, allow cellular components such as erythrocytes and platelets to penetrate the matrix, increasing the effective contact area and enhancing adhesion, which accelerates hemostasis. The macroporous structure also determines the shape memory property by sorbing wound exudate [13], while the ability to release excess moisture allows the scaffold to retain its shape and fit snugly to the entire wound surface, preventing bleeding over the entire wound area, especially in the case of incompressible cavity wounds [23]. The compressive modulus of elasticity must be adapted to the type of body tissue because of mechanical strength of highly porous structure. The cellulosic nature of scaffolds promotes the contact activation of hemostasis mechanisms; mainly the formation of thrombin and the rapid formation of platelet plugs [25]. Negatively charged surfaces can activate coagulation factors (XI, XII, precallikrein), accelerating internal coagulation. Calcium ions on the surface enhance thrombin activation [38].

Mesopores (2–50 nm), in contrast, are too small to allow cell penetration since blood cells are several orders of magnitude larger (erythrocytes ~6–8 µm, platelets ~2–4 µm). The role of mesoporous structures lies primarily in the adsorption of plasma proteins (fibrinogen, albumin, complement components), which influences platelet adhesion and activation. Thus, mesopores regulate hemocompatibility through protein–surface interactions rather than serving as physical channels for cellular passage [38,39].

It should be noted that in several studies, exact pore sizes or ranges were not reported, allowing only approximate estimation based on SEM micrographs. The majority of analyzed scaffolds can be classified as macroporous gels (12 of 20 publications), though some exhibit combined macro- and mesoporous architectures without quantitative assessment of their ratio [13,18,20,25,30].

Porosity values reported selected studies range from 70.0% to 97.5%. It is evident that porosity affects mechanical strength, whereas pore size has a more pronounced impact on hemostatic efficiency. Compressive strength is a key parameter, as it determines the structural stability of the gel upon contact with aqueous media or blood. Only about half of the reviewed studies provide quantitative compressive strength data, which vary widely (0.002–0.700 MPa), reflecting differences in testing methods and preventing direct comparison of results. In our view, a suitable hemostatic scaffold should exhibit sufficient mechanical integrity to prevent structural collapse during application while maintaining efficient interaction with the wound surface.

Many authors also analyze the chemical bonding and functional groups within the gels using Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) or nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR, 1H or 13C), though these data are not summarized in this review. Some researchers additionally consider the presence of coagulation factors—most notably Ca2+ ions—within the gel matrix, which play a pivotal role in the coagulation cascade by promoting the conversion of prothrombin to thrombin [20].

Hence, the key criteria in this first group include pore size determination, compressive strength, characterization of reactive functional groups, and evaluation of coagulation-related components such as calcium ions.

4.2. In Vitro Tests

The second group of parameters includes studies of the interaction between the developed gels and biological media in vitro (Table 3). The blood clotting index (BCI) is one of the most widely used metrics for assessing hemostatic materials. In approximately 70% of the reviewed works, the BCI values varied from 0.05 to 89.76%. Lower BCI values indicate faster and more efficient coagulation, identifying these materials as more promising hemostatic systems. This correlation has been consistently confirmed for both aerogels and cryogels [12,13,14,15,18,19,20,22,24,25,28].

Table 3.

In vitro analysis of cellulose-based hemostatic gels.

Another key parameter is the adhesion rate of red blood cells and platelets to the gel surface, which depends on the presence of reactive functional groups. The adhesion of these cellular components plays a critical role in initiating and maintaining hemostasis. However, not all studies account for both cell types; in several works [12,13], only erythrocyte adhesion was evaluated (52.91%, 80.45%, and 40.00%, respectively).

The hemolysis ratio of erythrocytes was reported in most publications [12,13,14,15,16,17,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. According to the American Society for Testing and Materials standard (ASTM F756–2000), hemolysis should not exceed 5%. Most authors confirmed that their measured values were below this threshold; several studies provided specific values ranging from 0.66% to 2.30% [12,14,17,19,21,25,28]. These results indicate negligible cytotoxic effects and validate the biocompatibility of direct blood contact.

Additionally, cytocompatibility analyses revealed high cell viability (>90% in 15 of 20 studies), consistent with ISO 10993–5 requirements (Switzerland, 2009) [22]. Several studies also assessed the antibacterial activity of the gels, mainly against S. aureus (Gram-positive) and E. coli (Gram-negative) [10,11,14,17,23,25,26,27,28], with bactericidal ratios against E. coli ranging 2 from 70% to 100%. The incorporation of antibacterial agents via ionic, covalent or hydrogen bonding, Ag nanoparticles, chitosan, dopamine can prevent microbial contamination of wounds and reduce the risk of infection-related complications.

Compared with the first group, in vitro tests—covering BCI, erythrocyte and platelet adhesion, hemolysis, cytocompatibility, and antibacterial activity—provide insight into the interaction mechanisms between porous scaffolds and biological systems, confirming their safety prior to in vivo testing.

4.3. In Vivo Hemostatic Efficiency

This group is the most clinically relevant since it directly determines the therapeutic potential of hemostatic materials (Table 4). Most studies employed rats as experimental animals, and less frequently rabbits, consistent with the 3Rs policy (replacement, reduction, refinement) and international biomedical ethics [19]. The most common experimental models included liver punch biopsy wounds (3–5 mm in diameter, 1–5 mm deep) and distal tail amputations (1–2 cm). A femoral artery bleeding model was used only once [14].

Table 4.

In vivo analysis of cellulose-based hemostatic gels.

The general in vivo testing protocol comprised anesthesia, surgical field preparation, wound induction, immediate gel application, and measurement of hemostasis time and blood loss. Cotton or double-layer gauze was used as negative controls, while commercial gelatin sponges served as positive controls. We consider gauze and cotton inappropriate reference materials, as they exhibit minimal procoagulant activity and therefore poor hemostatic performance. The absence of a standard reference material (SRM) remains a major obstacle for comparing in vivo results.

Meng Wang et al. [18] did not perform direct hemostatic tests but instead used the aerogel as a skin graft material in animal experiments, which can be regarded as a modified form of in vivo assessment.

The tail amputation model is faster and simpler than the liver bleeding model and is often used as an auxiliary test for evaluating coagulation parameters before or after the main experiment. In contrast, noncompressible wounds of parenchymal organs such as the liver are considered more objective, as they mimic severe surgical trauma involving both venous and arterial bleeding [41]. The choice of model should depend on the material’s intended use: for cellulose-based gels as dressing materials, surface compressible bleeding models (tail) are appropriate; for adhesive porous scaffolds, internal noncompressible bleeding models (liver) are preferable.

Post-hemostasis morphological evaluation using scanning electron microscopy [29,30] revealed dense fixation of erythrocytes within the gel matrix and a developed fibrin network, confirming that bleeding cessation occurs through blood–cellulose interaction, local thrombus formation, and the development of a platelet–fibrin matrix on the gel surface.

On one hand, published data indicate that highly porous cellulose-based cryo- and aerogels possess significant potential in biomedical applications due to their rapid hemostatic response, effective water absorption, enhanced erythrocyte and platelet adhesion, and activation of the coagulation cascade [12,27]. Their efficiency is attributed to abundant hydroxyl groups, hydrophilicity, and high porosity. Upon blood contact, the scaffolds rapidly absorb liquid into the porous channels, triggering autocatalytic coagulation activation, platelet aggregation, and erythrocyte adhesion, ultimately leading to thrombus formation [10]. The criteria identified in this review should be considered essential for the rational design of new hemostatic biomaterials.

On the other hand, current studies reveal several limitations. Most focus solely on in vitro hemostatic performance, with insufficient evaluation of blood–cell interactions and tissue responses in vivo. Data on biocompatibility and potential cytotoxicity are often fragmentary, complicating the assessment of clinical safety and efficacy. Furthermore, systematic comparisons of porosity parameters, scaffold density, and gel preparation methods are lacking, hindering understanding of hemostatic mechanisms. Long-term effects such as material degradation, inflammation, and microbial adhesion remain insufficiently explored.

The assessment of hemostasis effectiveness can be carried out using biosensor devices, such as dielectric micro-sensors that measure the dielectric permittivity of biopolymers [42]. To develop wearable medical systems and personalized human–machine sensor interfaces, it is necessary to use functional materials that provide flexibility for electronic devices while also being biocompatible and safe for application on wound surfaces [43]. Currently, cellulose-based materials have found widespread application in various fields of sensor technology for the fabrication of deformation and humidity-sensitive sensors, owing to their unique properties and responsiveness [44]. Analytical methodologies for blood components can significantly enhance the functionality of hemostatic materials across various practical applications. Non-organic aerogels, which are already extensively used in biosensors and electrodes within intelligent sensing systems for biomolecule detection in biomedicine, present a promising platform for integration into highly porous cellulose scaffolds employed in hemostasis. Such integration could enable innovative diagnostic capabilities, for example, amperometric glucose monitoring in the vicinity of the wound for diabetic patients, where hyperglycemia impairs wound healing and elevates infection risk [45,46]. Additionally, the development of analytical techniques based on differential pulse voltammetry for measuring dopamine concentrations in critically ill patients experiencing severe hemorrhage could be instrumental, as precise regulation of dopamine levels is crucial for maintaining adequate blood pressure and circulatory stability [47,48]. Therefore, such biocompatible materials as cellulose-based scaffolds can serve as foundational components for devices that monitor hemostasis, thereby enabling the development of systems for real-time assessment and evaluation of hemostatic function.

The accuracy of hemostasis efficacy assessment can be enhanced through biosensor technologies, particularly by using cellulose-based scaffolds as components of sensor devices. Through chemical surface modification, sensing applications based on aerogels and cryogels have been developed to detect specific molecules and bacteria in the bloodstream, which is particularly important for early cancer diagnosis, infection detection, and monitoring chronic conditions such as diabetes [7]. The creation of highly porous scaffolds should not be limited solely to effective hemostasis, as cellulose cryo- and aerogels simultaneously possess properties beneficial for sensor systems: high porosity (rapid absorption), large specific surface area (adsorption of proteins/cells), rich surface chemistry (introduced functional groups), and mechanical flexibility. These properties allow for the incorporation of indicators (pH indicators, electrochemical sensors, biomolecular recognition elements, or conductive fillers) into the matrix, enabling the detection of local signals related to the status of bleeding and wound healing [49].

Within the framework of scientific and practical analysis, the main controllable parameters characterizing the condition during hemorrhage are identified:

- i.

- Absorbed fluid volume (indirect assessment of blood loss). Changes in mass/volume/swelling of the gel can be easily recorded gravimetrically or through capacitive/resistive measurements when conductive elements are incorporated into the matrix. This provides real-time information about the rate and volume of blood loss [50]

- ii.

- Local pH. During massive blood loss or hypoperfusion, tissue pH may decrease (local acidosis). Incorporation of pH-sensitive dyes or electrode-based indicators into the matrix allows detection of such shifts, which is important for early diagnosis of ischemia or infection. Smart wound dressings with pH detection have been demonstrated [51]

- iii.

- Ionic composition/electrical conductivity. Changes in Na+, K+, and Ca2+ concentrations—e.g., during infusion therapy or coagulopathy—influence the electrical conductivity of wound exudate. Incorporation of conductive fillers (carbon nanomaterials, MXene, etc.) enables monitoring of conductivity/impedance, which correlates with blood composition and the degree of hemostatic progression [52,53]

- iv.

- Protein/coagulation profile. Adsorption of fibrinogen, platelets, and other proteins alters the optical, mechanical, and rheological properties of the gel (transparency, stiffness, conductivity). These changes can be detected optically (light transmission/scattering) or mechanically (stiffness, resonance frequency). Several studies demonstrate protein and cell detection on biopolymer matrices [49].

- v.

- Biomarkers of infection/inflammation. Embedding biospecific elements (antibodies, enzymes, nucleic-acid probes) into the cellulose matrix enables detection of bacterial markers, lactate, or inflammatory molecules—critical for evaluation of post-hemostatic infection risk [51].

Simultaneous hemostasis and wound monitoring enable the rapid assessment of the hemostatic agent’s efficacy and facilitate the timely implementation of additional interventions if necessary. Furthermore, this approach allows for the detection of infection or perfusion deterioration through the analysis of parameters such as pH, temperature, and biomarkers. Additionally, it can reduce the frequency of dressing changes and invasive procedures via remote monitoring using smart dressings [51,52].

Therefore, future research should adopt an integrated approach, including standardized hemostasis models, validated reference materials, biocompatibility and immune response evaluation, and systematic correlation of structural and functional characteristics. Highly porous cellulose-based scaffolds exhibit excellent hemostatic properties due to their optimized porosity and high hydrophilicity. Modification with functional components such as Au nanoparticles or chitosan can enable detection and quantification of important biomarkers and analytes (glucose, pH levels, or specific proteins) directly during the hemostasis process [51]. Cellulosic aerogels and cryogels hold promising potential for use as hemostatic materials in medical applications. However, their successful integration into clinical practice needs a comprehensive research program. Efforts should focus on several key areas: ensuring hygienic cleanliness, assessing long-term stability during storage, understanding the immune response they elicit, and examining their interaction with biological tissues.

5. Conclusions

In this review, we identified three major groups of key criteria that should be considered when developing new cellulose-based highly porous scaffolds with hemostatic functionality:

- I.

- Physicochemical and mechanical properties (pore size distribution, compressive strength, and presence of functional groups).

- II.

- In vitro tests (blood clotting index, red blood cell adhesion rate, hemolysis, cytocompatibility, and antibacterial activity).

- III.

- In vivo hemostatic efficiency (hemostasis time and blood loss) in compliance with the 3Rs policy (replacement, reduction, refinement).

The systematization of published data shows that modern cellulose modifications represent a promising basis for the development of safe and effective hemostatic materials. However, the absence of a standard reference material (SRM)—with gauze or cotton still being used as controls—as well as the lack of unified evaluation methods and the high variability of experimental designs, significantly complicate the comparability of results across studies.

According to the proposed criteria, a complete and comprehensive characterization of the developed highly porous scaffolds is missing in all analyzed publications. The studies by Ahmad Mahmoodzadeh et al. [14] and Zhan Xu et al. [16] appear to be the most complete in terms of structural and functional characterization.

In conclusion, we propose several practical recommendations for the design and characterization of cellulose-based gels:

- −

- When preparing gels according to the methodologies described in this review, with minimal modification of synthesis parameters, analysis of the first group of criteria is sufficient.

- −

- When modifying the synthesis process while using similar raw materials, physicochemical and mechanical characterization should be supplemented by in vitro tests to confirm the effect of changes on hemostatic response.

- −

- When developing a fundamentally new gel, it is necessary to analyze all groups of criteria, define the intended hemostatic application, and select an appropriate in vivo bleeding model.

Future research should focus on the standardization of methodological research protocols, justification of efficacy metrics, and a more detailed investigation of structure–property–effect relationships. However, despite the significant potential of using highly porous cellulose-based scaffolds for the development of smart platforms, their advancement faces several existing limitations that may impede their implementation and widespread adoption. These include biocompatibility, sensor selectivity and sensitivity, as well as reliability.

Additionally, the development of smart platforms based on cellulose scaffolds from plant and bacterial raw materials for monitoring the condition of damaged tissue, blood loss, blood analysis, and microenvironmental factors is considered a promising area of research. These technologies enable real-time, precise diagnostics, enhance treatment efficacy, and improve patient outcomes by providing continuous monitoring of physiological parameters.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.A.S. and A.S.A.; methodology, N.A.S. and K.A.M.; data curation, N.A.S. and L.L.S.; writing—original draft preparation, N.A.S. and A.R.S.; writing—review and editing, A.R.S., A.S.A. and L.L.S.; visualization, K.A.M.; supervision, A.S.A.; project administration, A.R.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The Russian Science Foundation supported preparation of this review article (project 25-24-20063).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Northern (Arctic) Federal University named after M.V. Lomonosov and Northern State Medical University (Arkhangelsk) for technical support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hickman, D.A.; Pawlowski, C.L.; Sekhon, U.D.; Marks, J.; Gupta, A.S. Biomaterials and advanced technologies for hemostatic management of bleeding. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1700859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, F.; Zuo, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, F.; Li, C.; Zeng, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, F. Centrifugal Spinning-Derived Biomimetic Aerogel for Rapid Hemostasis with Minimal Blood Loss. Nano Lett. 2025, 25, 6040–6050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukatuka, C.F.; Mbituyimana, B.; Xiao, L.; Qaed Ahmed, A.A.; Qi, F.; Adhikari, M.; Shi, Z.; Yang, G. Recent Trends in the Application of Cellulose-Based Hemostatic and Wound Healing Dressings. J. Funct. Biomater. 2025, 16, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cidreira, A.C.M.; de Castro, K.C.; Hatami, T.; Linan, L.Z.; Mei, L.H.I. Cellulose nanocrystals-based materials as hemostatic agents for wound dressings: A review. Biomed. Microdevices 2021, 23, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezvani Ghomi, E.; Niazi, M.; Ramakrishna, S. The evolution of wound dressings: From traditional to smart dressings. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2023, 34, 520–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budtova, T.; Aguilera, D.A.; Beluns, S.; Berglund, L.; Chartier, C.; Espinosa, E.; Gaidukovs, S.; Klimek-Kopyra, A.; Kmita, A.; Lachowicz, D.; et al. Biorefinery approach for aerogels. Polymers 2020, 12, 2779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noman, M.T.; Amor, N.; Ali, A.; Petrik, S.; Coufal, R.; Adach, K.; Fijalkowski, M. Aerogels for biomedical, energy and sensing applications. Gels 2021, 7, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyshkunova, I.V.; Poshina, D.N.; Skorik, Y.A. Cellulose cryogels as promising materials for biomedical applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrabi, S.M.; Sharma, N.S.; Shatil Shahriar, S.M.; Xie, J. Nanofiber aerogels: Recent progress and biomedical applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 45323–45353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Dai, Q.; Zhu, S.; Feng, Q.; Qin, Z.; Gao, H.; Cao, X. An ultrafast water absorption composite cryogel containing Iron-doped bioactive glass with rapid hemostatic ability for non-compressible and coagulopathic bleeding. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 469, 143758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pochinkova, P.A.; Gorbatova, M.A.; Narkevich, A.N.; Grjibovski, A.M. Updated brief recommendations onwriting and presenting systematic reviews: What’s new in PRISMA-2020 guidelines? Mar. Med. 2022, 8, 88–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, M.; Yang, X.; Shi, T.; Yang, Y. All-natural aerogel of nanoclay/cellulose nanofibers with hierarchical porous structure for rapid hemostasis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 278, 134592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Chen, F.; Wu, M.; Xiang, J.; Yan, F.; Xie, Y.; Tong, Z.; Chen, Y.; Cai, L. Biocompatible and antibacterial Flammulina velutipes-based natural hybrid cryogel to treat noncompressible hemorrhages and skin defects. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 960407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoodzadeh, A.; Moghaddas, J.; Jarolmasjed, S.; Kalan, A.E.; Edalati, M.; Salehi, R. Biodegradable cellulose-based superabsorbent as potent hemostatic agent. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 418, 129252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, W.; Feng, Y.; Tan, J.; Zeng, H.; Jalaludeen, R.K.; Zeng, X.; Zheng, B.; Song, J.; Zhang, X.; Chen, S.; et al. Carbonized cellulose aerogel derived from waste pomelo peel for rapid hemostasis of trauma-induced bleeding. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2307409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Tian, W.; Wen, C.; Ji, X.; Diao, H.; Hou, Y.; Fan, J.; Liu, Z.; Ji, T.; Sun, F.; et al. Cellulose-based cryogel microspheres with nanoporous and controllable wrinkled morphologies for rapid hemostasis. Nano Lett. 2022, 22, 6350–6358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Li, X.; Wei, L.; Ma, S.; Wang, J.; Zhu, W.; Wang, H. Engineering high-performance composite cellulose materials for fast hemostasis. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2024, 10, 5313–5326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Sun, P.; Zhang, J.; Li, D.; Liu, Y.; Xia, Y.; Shao, L.; Jia, M. Intelligent and biocompatible cellulose aerogels featured with high-elastic and fast-hemostatic for epistaxis and wound healing. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 277, 134239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendes, B.B.; Gómez-Florit, M.; Araújo, A.C.; Prada, J.; Babo, P.S.; Domingues, R.M.; Reis, R.L.; Gomes, M.E. Intrinsically bioactive cryogels based on platelet lysate nanocomposites for hemostasis applications. Biomacromolecules 2020, 21, 3678–3692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Jin, Z.; Kamiya, T.; Liu, X.; Tian, Y.; Xia, R.; Wang, G.; Li, T.; Zhang, Q. Nanoporous zeolite anchored cellulose nanofiber aerogel for safe and efficient hemostasis. Small 2025, 21, 2500696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, G.; Park, M.; Lim, H.; Lee, B.T. Natural TEMPO oxidized cellulose nano fiber/alginate/dSECM hybrid aerogel with improved wound healing and hemostatic ability. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 243, 125226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Hu, X.; Mequanint, K.; Luo, G.; Xing, M. Platelet vesicles synergetic with biosynthetic cellulose aerogels for ultra-fast hemostasis and wound healing. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2024, 13, 2304523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakya, K.R.; Nigam, K.; Sharma, A.; Jahan, K.; Tyagi, A.K.; Verma, V. Preparation and assessment of agar/TEMPO-oxidized bacterial cellulose cryogels for hemostatic applications. J. Mater. Chem. B 2024, 12, 3453–3468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Li, Q.; Zhang, S.; Liu, Z.; Lv, X.; Chen, J. Preparation of biodegradable carboxymethyl cellulose/dopamine/Ag NPs cryogel for rapid hemostasis and bacteria-infected wound repair. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 222, 272–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chu, C.; Chen, C.; Sun, B.; Wu, J.; Wang, S.; Ding, W.; Sun, D. Quaternized chitosan/oxidized bacterial cellulose cryogels with shape recovery for noncompressible hemorrhage and wound healing. Carbohydr. Polym. 2024, 327, 121679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.; Li, Y.; Tong, X.; Chen, L.; Wang, L.; Li, T.; Zhang, Q. Strongly-adhesive easily-detachable carboxymethyl cellulose aerogel for noncompressible hemorrhage control. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 301, 120324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Pan, S.; Wang, L.; Liu, X.; Jin, Z.; Xia, R.; Zhang, Q. Superhydrophobic cellulose nanofiber aerogels for efficient hemostasis with minimal blood loss. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 47294–47302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Liu, L.; Chen, L.; Chen, G.; Wei, Y.; Hong, F.F. Synthesis of hemostatic aerogel of TEMPO-oxidized cellulose nanofibers/collagen/chitosan and in vivo/vitro evaluation. Mater. Today Bio 2024, 28, 101204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, W.; Li, W.; Wang, G.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, Q. Water-swellable cellulose nanofiber aerogel for control of hemorrhage from penetrating wounds. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2022, 5, 4886–4895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Chen, L.; Liu, X.; Xia, R.; Li, W.; Wang, G.; Zhang, Q. Zeolite firmly anchored regenerated cellulose aerogel for efficient and biosafe hemostasis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 304, 140743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, L.Y.; Weng, Y.X.; Wang, Y.Z. Cellulose aerogels: Synthesis, applications, and prospects. Polymers 2018, 10, 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Huang, T.; Yang, J.H.; Zhang, N.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Z.W. Green synthesis of hybrid graphene oxide/microcrystalline cellulose aerogels and their use as superabsorbents. J. Hazard. Mater. 2017, 335, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, L.; Yang, Y.; Pang, B.; Xu, W.; Duan, G.; Zhang, K. Recent progress on nanocellulose aerogels: Preparation, modification, composite fabrication, applications. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2005569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouras, H.; Zou, F.; Tillier, Y.; Buwalda, S.; Budtova, T. Starch aerogels, cryogels and xerogels for biomedical applications. In Proceedings of the Advanced Functional Polymers for Medicine, Utrecht, The Netherlands, 5–7 June 2024; Available online: https://hal.science/hal-04659189v1 (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- Rodríguez-Dorado, R.; López-Iglesias, C.; García-González, C.A.; Auriemma, G.; Aquino, R.P.; Del Gaudio, P. Design of aerogels, cryogels and xerogels of alginate: Effect of molecular weight, gelation conditions and drying method on particles’ micromeritics. Molecules 2019, 24, 1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croll, T.I.; Gentz, S.; Mueller, K.; Davidson, M.; O’Connor, A.J.; Stevens, G.W.; Cooper-White, J.J. Modelling oxygen diffusion and cell growth in a porous, vascularising scaffold for soft tissue engineering applications. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2005, 60, 4924–4934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchtová, N.; Budtova, T. Cellulose aero-, cryo-and xerogels: Towards understanding of morphology control. Cellulose 2016, 23, 2585–2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, J.H.; Lam, Y.W.; Fraser, S.T. Cellular dynamics of mammalian red blood cell production in the erythroblastic island niche. Biophys. Rev. 2019, 11, 873–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Guo, B.; Wu, H.; Liang, Y.; Ma, P.X. Injectable antibacterial conductive nanocomposite cryogels with rapid shape recovery for noncompressible hemorrhage and wound healing. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawrence, M.; Jiang, Y. Porosity, pore size distribution, micro-structure. In Bio-Aggregates Based Building Materials. RILEM State-of-the-Art Reports; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2017; Volume 23, pp. 39–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darya, G.; Mohammadi, H.; Dehghan, Z.; Nakhaei, A.; Derakhshanfar, A. Animal models of hemorrhage, parameters, and development of hemostatic methods. Lab. Anim. Res. 2025, 41, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maji, D.; De La Fuente, M.; Kucukal, E.; Sekhon, U.D.; Schmaier, A.H.; Gupta, A.S.; Suster, M.A. Assessment of whole blood coagulation with a microfluidic dielectric sensor. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2018, 16, 2050–2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Zhu, Y.; Cheng, W.; Chen, W.; Wu, Y.; Yu, H. Cellulose-based flexible functional materials for emerging intelligent electronics. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2000619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ummartyotin, S.; Manuspiya, H. A critical review on cellulose: From fundamental to an approach on sensor technology. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 41, 402–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Xu, Y.; Han, D.; Wang, X.; Li, T.; Hu, H.; Yi, Z.; Ni, A. 3D porous graphene aerogel@GOx based microfluidic biosensor for electrochemical glucose detection. Analyst 2020, 145, 5141–5147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, J.-M.; Yang, M.; Kim, D.S.; Lee, T.J.; Choi, B.G.; Kim, D.H. High performance electrochemical glucose sensor based on three-dimensional MoS2/graphene aerogel. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 15, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajkumar, C.; Veerakumar, P.; Chen, S.-M.; Thirumalraj, B.; Liu, S.-B. Facile and novel synthesis of palladium nanoparticles supported on a carbon aerogel for ultrasensitive electrochemical sensing of biomolecules. Nanoscale 2017, 9, 6486–6496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariyappan, V.; Jeyapragasam, T.; Chen, S.-M.; Murugan, K. Mo-W-O nanowire intercalated graphene aerogel nanocomposite for the simultaneous determination of dopamine and tyrosine in human urine and blood serum sample. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2021, 895, 115391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardes, B.G.; Del Gaudio, P.; Alves, P.; Costa, R.; García-Gonzaléz, C.A.; Oliveira, A.L. Bioaerogels: Promising Nanostructured Materials in Fluid Management, Healing and Regeneration of Wounds. Molecules 2021, 26, 3834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, D.K.; Trinh, K.T.L. Advances in wearable biosensors for wound healing and infection monitoring. Biosensors 2025, 15, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Wang, F.; Ye, H. MXene-based flexible electronic materials for wound infection detection and treatment. npj Flex. Electron. 2024, 8, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazizadeh, E.; Deigner, H.-P.; Al-Bahrani, M.; Muzammil, K.; Daneshmand, N.; Naseri, Z. DNA bioinspired by polyvinyl alcohol -MXene-borax hydrogel for wearable skin sensors. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2025, 386, 116331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirshafiei, M.; Afshar, A.K.; Yazdian, F.; Rashedi, H.; Rahdar, A.; Aboudzadeh, M.A. Bacterial cellulose: A sustainable nanostructured polymer for biosensor development. RSC Sustain. 2026. Advance Article. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.