Highlights

What are the main findings?

- The fiber fragment size and frequency were found to have a statistically significant difference between secondhand denim (length 370.5 µm, diameter 16.9 µm, 3093 fiber fragments per filter) and new denim (320.7 µm, 13.8 µm and 5962 fiber fragments per filter, respectively).

- This study concluded that the amount of fiber fragmentation material shed by secondhand denim was 23.2% of that shed by new denim specimens.

What is the implication of the main finding?

- Even though secondhand specimens shed less fiber fragments than new clothing, there is still shed material that needs to be considered, including dyes and processing chemicals that can contribute to anthropogenic contamination of the environment.

- The amount of mass shed and dimensional information from this study of fiber fragments is valuable information that can contribute to consumers’ and secondhand retailers’ decision-making processes when considering what is potentially entering the environment and in purchase decisions.

Abstract

Demand for clothing is estimated to increase globally by 4.5% per year, and secondhand clothing is often used to fill that demand. A clear understanding of the environmental impact of secondhand items would support transparency around sustainability, which is a rising consumer concern. This study focuses on the characteristics of the fiber fragment material released during the laundering of secondhand, 100% cotton denim clothing, and the implications of secondhand clothing’s contribution of fiber fragments to the environment. The test method used was AATCC TM212-2021, with detergent, conditioned specimens, and filters. The specimens included thirteen pairs of secondhand men’s 100% cotton jeans (SHS) and two pairs of new jeans (CN controls). This study concluded that the amount of fiber fragmentation material shed by SHS was 23.2% of that shed by CN. While this is less than is shed by new clothing, there is still shed material to consider, including dyes and processing chemicals that can contribute to anthropogenic contamination of the environment. The fiber fragment size and frequency were found to have statistically significant differences between SHS (length 370.5 µm, diameter 16.9 µm, 3093 fiber fragments per filter) and CN (320.7 µm, 13.8 µm, and 5962 fiber fragments per filter).

Keywords:

fragment; laundering; material wear; microfiber; fiber fragmentation; denim; secondhand clothing; cotton 1. Introduction

Demand for clothing is estimated to increase globally by 4.5% a year according to the Institution of Mechanical Engineers [1]. Secondhand clothing is one viable possibility for meeting this demand; current secondhand clothing sales have reached USD 100–120 billion in 2019 [2]. It is estimated that secondhand clothing sales will continue to increase by 127% by 2026 [3]. The rise in secondhand clothing consumption has its origins in multiple factors, such as consumer budget pressures, unique styling opportunities, platform creation, destigmatization and cultural acceptance, and sustainability practices. Oscario [4] found that social media has created a new perception of secondhand clothing, especially for Generation Z. This is supported by the ability of social media to create, share, and circulate information. Studies have found direct support for the positive effects of social media on young consumers’ attitudes towards and engagement with secondhand clothing in Malaysia, the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe, and China [5,6,7,8,9].

The new perception has boosted the purchase of secondhand clothing and its resale by social influencers and on resale apps [10,11].

As Sicurella of National Public Radio notes, reflecting this broad cultural trend,

“Not surprisingly, social media is driving the obsession. Influencers post massive thrift hauls on Instagram, TikTok and YouTube. That’s where trends emerge. [including] environmental sustainability [which] has become a significant priority influencing the shopping choices of young consumers”.[10] (p. 4)

There are risks to the adoption of secondhand clothing by consumers. Hur [12] and Koay et al. [13] found that the perceived concerns were self-image, limitations of self-enhancement and self-expression (aesthetics), cleanliness, and quality when comparing secondhand clothing users and non-secondhand clothing users. This is similar to findings from an earlier study by Yan et al. [14], in which secondhand clothing shoppers and non-secondhand clothing shoppers had differing levels of concern due to environmental attitudes, perceived cleanliness, and vintage style (aesthetics), with less sensitivity to prices. In a cohort study, it was observed that younger consumers perceive the greatest risk for purchasing secondhand clothing to be to self-image and aesthetics, while older consumers focus on self-image, functional risk (product not holding up to intended use), and sanitary risk (risk of disease and dirt) [15]. Hur [12] concluded that secondhand retailers need to include sustainability marketing and quality control strategies in promotions, addressing concerns that consumers have about non-standardized quality and a lack of awareness of the benefits of secondhand garments. Kuupole et al. [16] and Acquaye et al. [17], in studies in Ghana on intentions of secondhand clothing adoption, surmised that more education of consumers for sustainable clothing purchases and disposal is needed. To address these concerns, they suggested, respectively, government policies and workshops and seminars; or limiting the importation of this clothing, increasing the availability of waste bins, and establishing recycling plants. A clear understanding of quality guidelines for secondhand items would support these proposals [18,19] and contribute to the transparency of sustainability and circularity, a growing consumer concern.

An important component of secondhand clothing is denim garments, often in the form of jeans. Maximize Marketing Research’s 2025 report [20] on the upcycled denim market states that secondhand denim is increasingly significant as part of the used apparel movement and as a singular sustainability trend, with recycled denim accounting for approximately USD 10 billion of the overall denim demand in 2024. With resale in apparel growing, denim remains a key factor, due to its durability, branding, potential sustainability, and the consumer demand for vintage/upcycled styles. Market players for recycled denim include easily recognized brands with sustainability/recycling programs, such as MUD Jeans, Patagonia, Urban Outfitters, and Nudie Jeans, and upcycling retailers that are coming into their own, such as Beyond Retro, Zero Waste Daniel, RE/DONE, Broken Ghost Clothing, 1/OFF Paris, and Rentrayage [21]. Several studies’ data back what consumers recognize as the environmental benefits of secondhand clothing use. Levi Strauss & Co. [22] estimates that 2565 L of the 3791 L (67.6%) of water utilized over a jean’s lifetime is from cotton fiber cultivation; thus, when a garment is given a second life, that initial water investment for the fiber is mitigated. Additionally, by doubling the number of times a garment is worn, giving it a secondhand life, the greenhouse gases from that garment’s production could be lowered by 44% [23]. Chemical pollution and textile landfill waste can also be lessened by the continual reuse of already created garments [24].

Even with an item as durable as denim, fiber fragments, which are released during the home laundering process, have been found in environments as remote as the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, serving as indicators of anthropogenic pollution from garment use [25,26]. Athey et al. [25] focused on microscopically and spectroscopically identifying microfibers in Canadian lake and ocean sediment samples (n = 30+) along with fish digestive track samples. The results indicated that up to 23% of the fiber fragments identified from the environment were indigo denim cotton. The mass, length, and diameter of the fiber fragments were not collected. Suaria et al. [26] collected 916 seawater samples from around the globe. Using µFTIR characterization of fibers and digital microscopy to capture diameter and length data, the study’s results indicated that only 8.2% of oceanic fibers observed were synthetic, with 79.5% being cellulosic, and the remaining 12.3% being of animal origin. For all collected fragmented fiber types, there was a range of 0.09–27.06 mm in length and a range of 5 to 239 μm in diameter. Mass information was not collected. Deheyn et al. [27], in their citizen study of the waterway and air pollution of Ghana’s Kantamanto secondhand clothing market, focused on identifying microfiber accumulation. The study found that a majority of microfibers in rainwater and air samples were from synthetic fibers. However, the chemical analysis of waterborne microparticles revealed a distribution of cotton (29%), polypropylene (26%), polyester (14%), nylon (11%), and polyethylene (9%). This distribution of polymers closely corresponds to the ratio of materials found in the market.

Numerous studies have concentrated on new fabric microfiber shedding during laundering, with a majority focusing on synthetic fibers [28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35]. Given the data above regarding the prevalence of cellulose-based fibers in the environment, it is interesting to see a recent trend in studies to include testing fabric of natural fibers and cellulose-based manufactured fibers, along with synthetic fiber-based fabrics [25,36,37,38,39]; however, those that focus particularly on cellulose are few. As reported by Hazlehurst et al. [39], there is significant variation in methods, equipment, filtration, and analysis among laundering studies. There are very few studies that focus on shedding fiber fragments during laundering from secondhand clothing and their specific contribution to microfibers in the environment. Athey et al. [25] compared specimens from both new (n = 3) and “used” (n = 5) jeans in their environmental microfiber study and found that new garments released significantly greater numbers of microfibers. Rathinamoorthy et al. [40] reviewed studies that focused on artificially aged polyester garments to gauge the effects on microfiber creation during laundering and found that overall, the garments that had been aged shed more fiber fragments.

Testing and quality measures are built into first-use clothing items but are frequently unobserved for secondhand clothing items. With the increase in sales of secondhand clothing, understanding the environmental interactions of resale cotton garments through laundry wastewater provides consumers and vendors with much-needed information regarding purchase decisions, sustainability, environmental impact, marketing policies, and opportunities. While creating parameters for quality testing of secondhand clothing can be a challenge, since each item may have a different history of use, fiber fragment release studies can serve as a starting point for understanding the qualities of secondhand denim, as well as provide data to inform transparency and sustainability. The purpose of this study is to provide visual, mass, length, and diameter data on the fiber fragment material released by secondhand, 100% cotton denim clothing, as found in typical secondhand venues, and the implications of secondhand clothing’s contribution of fiber fragments to the environment. The goal is to provide a snapshot of the denim jeans available and the fiber fragments that can result from their use in a second life, an area of laundering studies that has not been captured in microfiber investigations.

2. Materials and Methods

The American Association of Textile Chemists and Colorists (AATCC) TM212-2021 Test Method for Fiber Fragment Release During Home Laundering [41] with detergent and Drying Option A was the protocol used in this study. Drying Option A requires that the prepared fabric specimens be placed in a standard atmosphere of 21 °C ± 2 °C (70 °F ± 4 °F) and 65% ± 5% RH for at least four hours prior to testing. Each specimen is laid separately and covered with aluminum foil to reduce possible contamination from air deposition. An overview of the AATCC TM212-2021 protocol steps can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

AATCC TM 212-21 Protocol Overview. 35+ h are needed to prepare, process, and analyze each pair of jeans.

In this experiment, men’s large 100% cotton jeans were selected from local resale shops to provide samples of secondhand denim. The secondhand 100% cotton garment was chosen to reflect the gap in fiber fragmentation laundering studies focusing on secondhand garments and allow for control of the fiber content in the study. Large men’s jeans were ideal in that they provided continuous fabric for each of the four specimens per jean, with no seaming in the sampled areas. There were 16 pairs available, 13 of which met the fabric size criteria to cut the four specimens from each pair of jeans measuring 200 mm by 340 mm (8 in by 13.5 in), with the longest edge parallel to the selvage. The specimen edges were finished with a clean-finish hem, seam type EFb-1, which is an edge finishing seam with a turned-under edge and one row of stitches. The finished specimens measured 100 ± 10 mm 240 ± 10 mm (4 ± 0.4 in 9.5 ± 0.4 in) each. The samples were taken from the front left calf (A), back left thigh (B), right back calf (C), and right front thigh (D) for each pair of jeans.

The variety of available secondhand jeans was documented by brand name, country of origin, weave pattern, color (warp and weft yarns), mass per unit area (g/m2), and thickness, as seen in Table 2. All of the samples in this study range from 300 to 600 g/m2, in mass per unit area, which is categorized as heavy denim [39], and were similar in weave pattern and color. A 500-196-30 Mitutoyo Digital AOS Absolute Caliper was used to measure denim thickness. The fabric thickness varied with the mass per unit area but was all in the range for the heavy denim category. For the controls (CN), two pairs of jeans were purchased online from a vendor with a similar price point and denim fabric as the secondhand jeans, if the secondhand jeans were to be purchased new (Table 2). The specimen preparation was repeated for the CN. A total of 52 (13 jeans with four specimens each) secondhand (SHS) specimens and 8 (2 jeans with four specimens each) CN specimens were then prepared according to the test procedure, which requires 4 specimens per test item (jean).

Table 2.

Brand, country of origin (COO), weave pattern, color, mass per area, and thickness information for 13 secondhand pairs of jeans and two control jeans. Note that 16 secondhand pairs were originally gathered. Jeans 6, 7, and 11 were not used because they lacked sufficient fabric without seaming in the sample areas. Original study numbers were kept throughout the study to prevent confusion regarding samples.

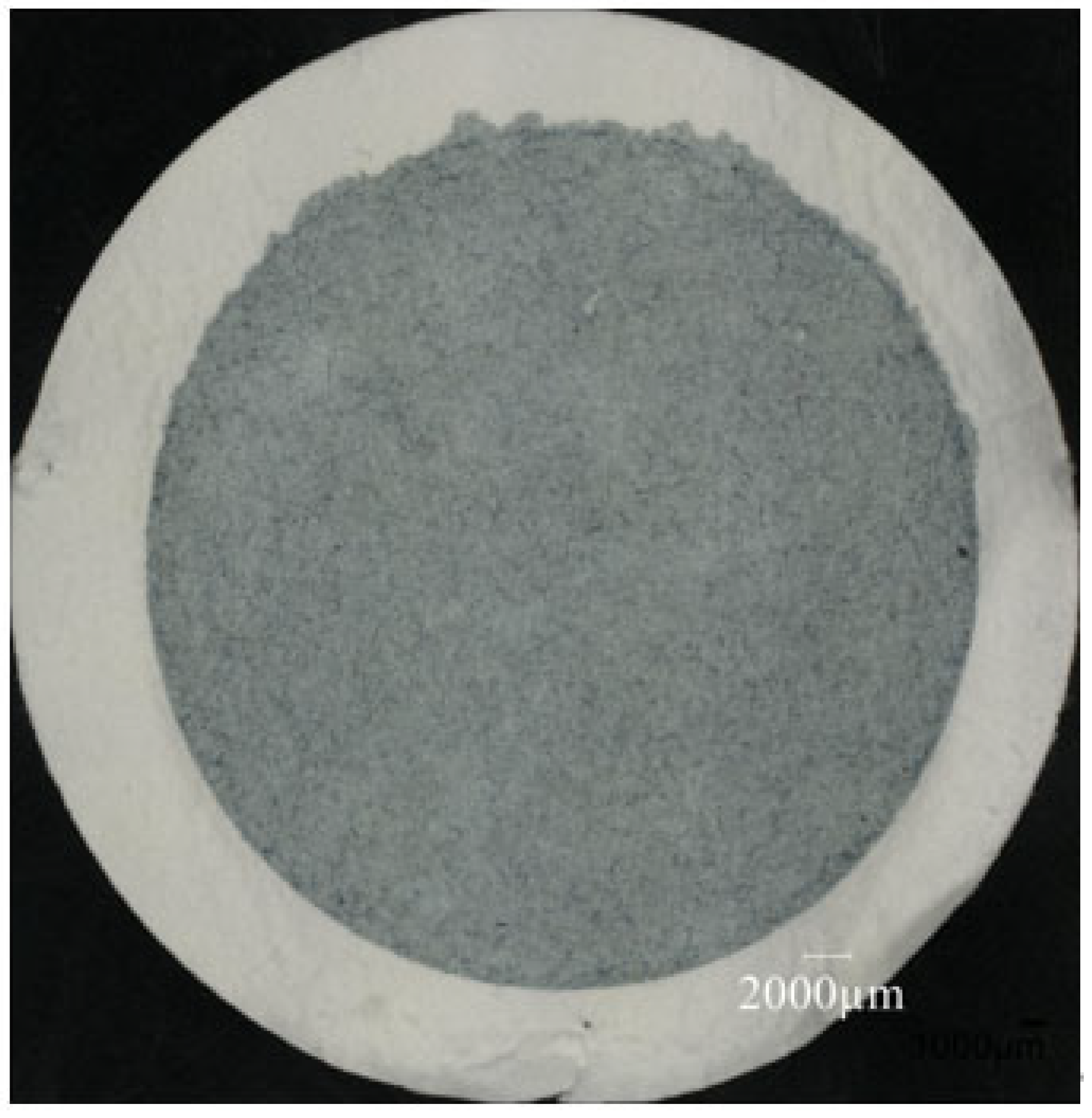

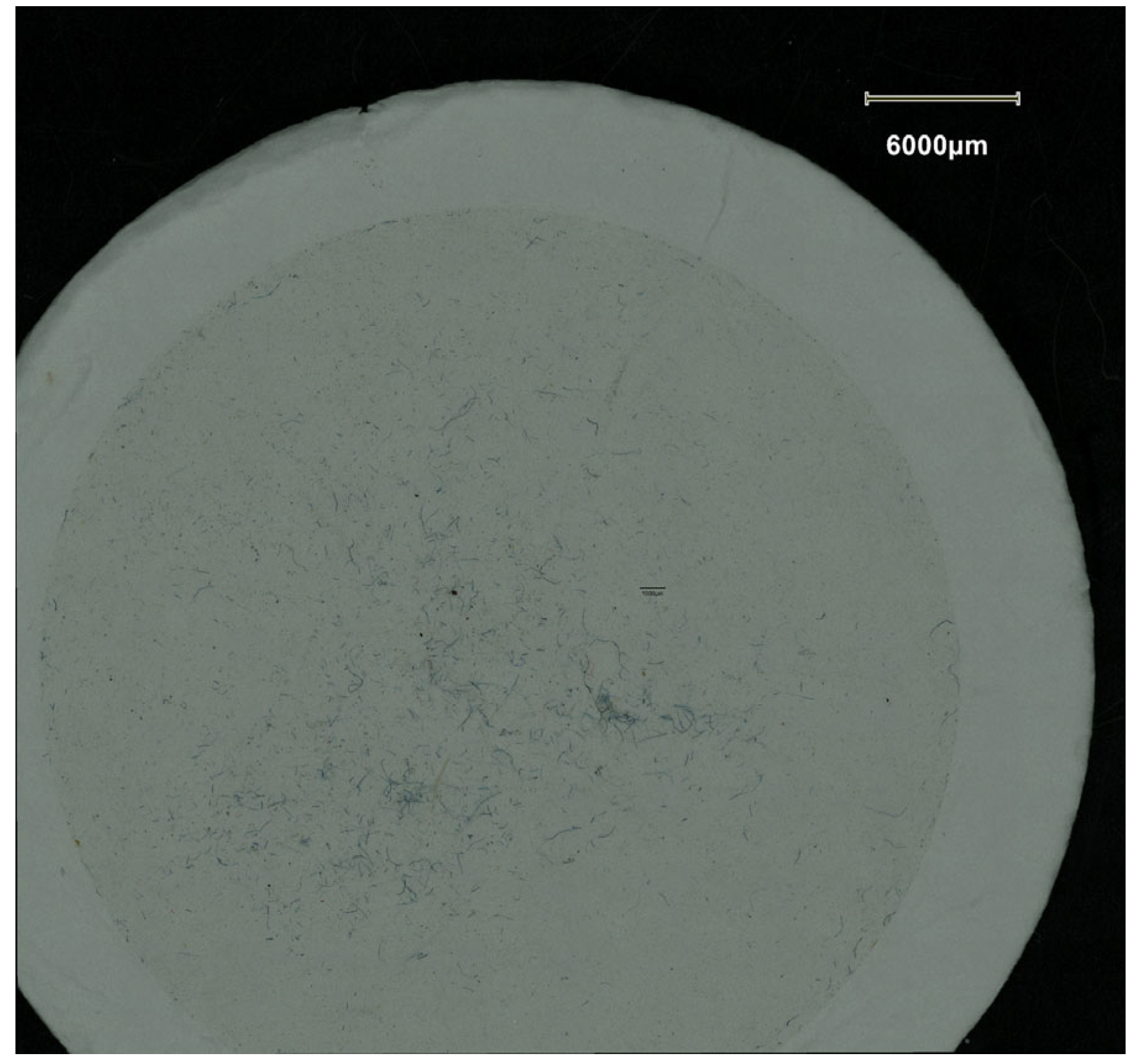

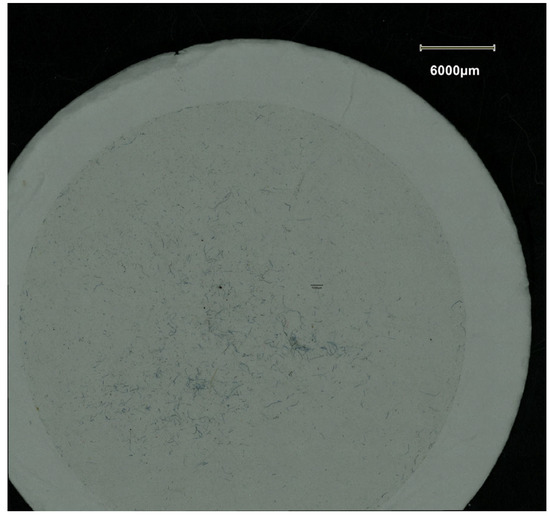

An SDL Atlas AATCC Launder-Ometer Model 10 was used, which allows three specimens and one calibration blank to be run simultaneously. The specimens were processed for one wash cycle. In this procedure, each sample is individually laundered in a canister to prevent specimen interaction and cross-contamination. The samples are washed for 45 min at 40 ± 2 °C, in a solution consisting of 0.25% of AATCC High Efficiency (HE) Standard Reference Liquid Detergent without optical brightener and deionized water. The overview in Table 1 provides details of the AATCC TM 212-2021 process. The wash water for each SHS and CN specimen canister was individually filtered to collect fragmented fiber content as directed by AATCC TM 212-2021. Each specimen’s wash water was filtered with a borosilicate glass fiber filter with no binder, 1.6 μm pore size, and 47 mm filter diameter. The filters had been prepared, conditioned, and weighed individually before the filtration process. After filtration, they were conditioned (see Table 1) and re-weighed for the mass of shed fiber. Two filters of the four filters per jean were randomly selected from each of the 13 secondhand jeans, for a total of 26 SHS filters that were analyzed, and two filters of the four filters per jean were randomly selected from each of the two control jeans, for a total of four of the eight CN filters. The difference between the pre-weighed and post-weighed filters gave the shed material mass. An example of a processed filter is shown in Figure 1.

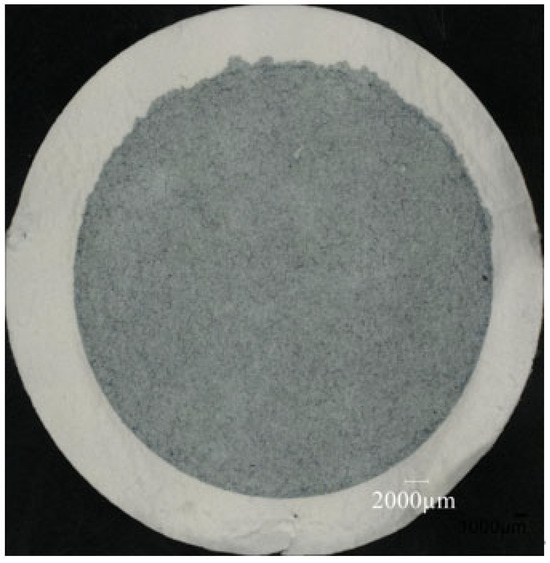

Figure 1.

Example filter 1B. 20× magnification.

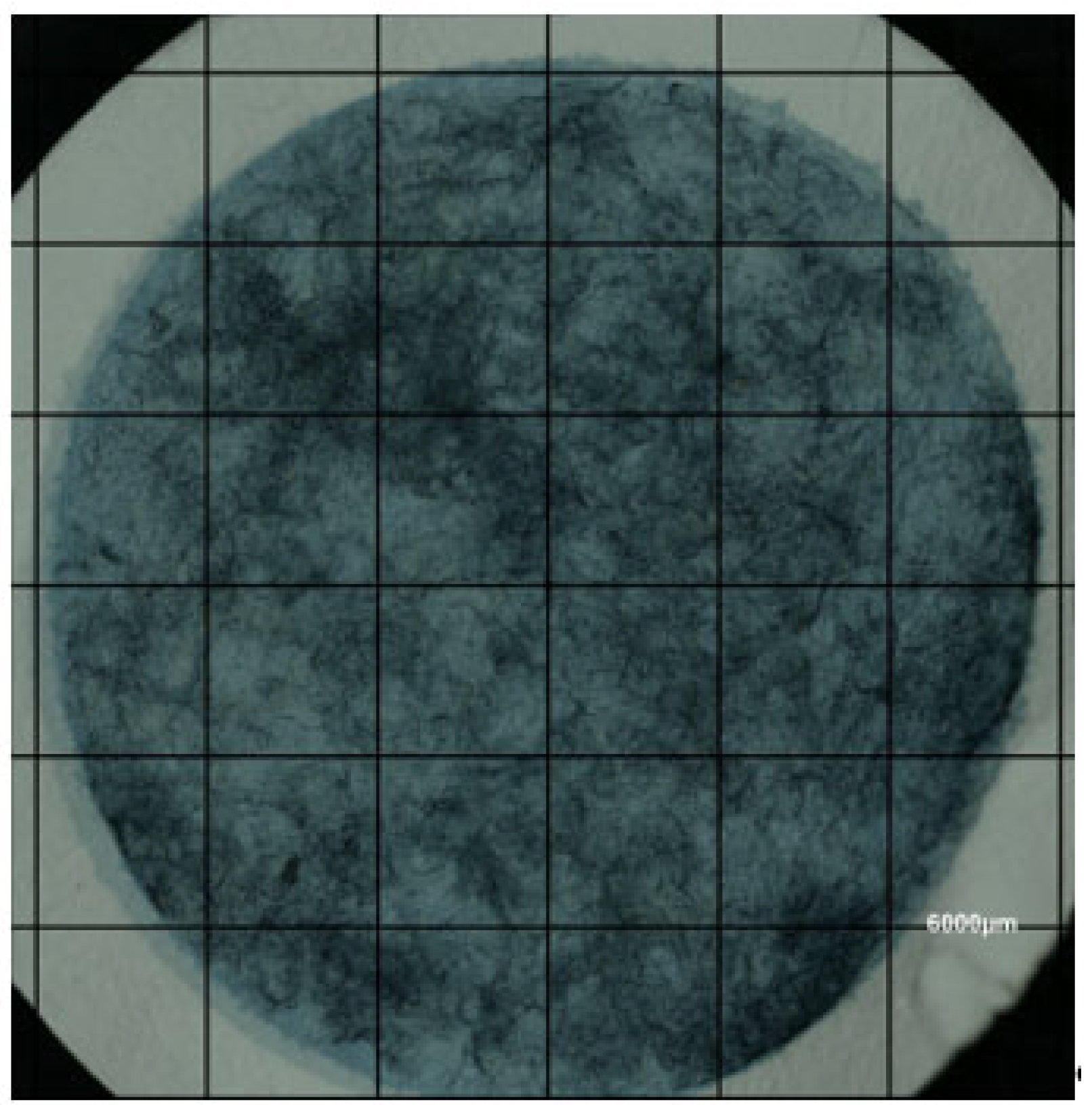

Using a Keyence Digital Microscope 7100, a microphotograph was taken of each of the selected 26 SHS and four CN filters at 50× magnification. A grid was superimposed on each of the filter micrographs, subdividing each into 27 6000 µm × 6000 µm squares, as seen in Figure 2. On each filter micrograph, one square was randomly selected from each upper left, center, and lower right region, resulting in three selected squares per filter micrograph and a total of 12 CN squares and 78 SHS squares analyzed. The count, length, and diameter of the fibers in each of the chosen squares were determined by measuring and counting all fiber fragments using the Keyence VHX-7000 Version 1.4.25.19 measurement software. Data and statistics on fiber counts and measurements were analyzed using Python 3.12 with add-on modules (NumPy 2.2.3, pandas 2.2.3, Matplotlib 3.20.2, seaborn 0.13.2, and SciPy 1.15.2).

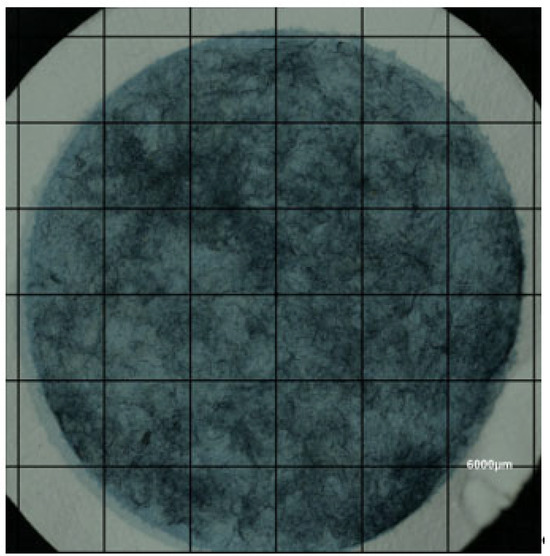

Figure 2.

Example of filter 2C with superimposed 6000 µm × 6000 µm square mesh for sampling. Please also note the intense blue “coating” on the filter. 50× magnification.

3. Results

3.1. Visual Description

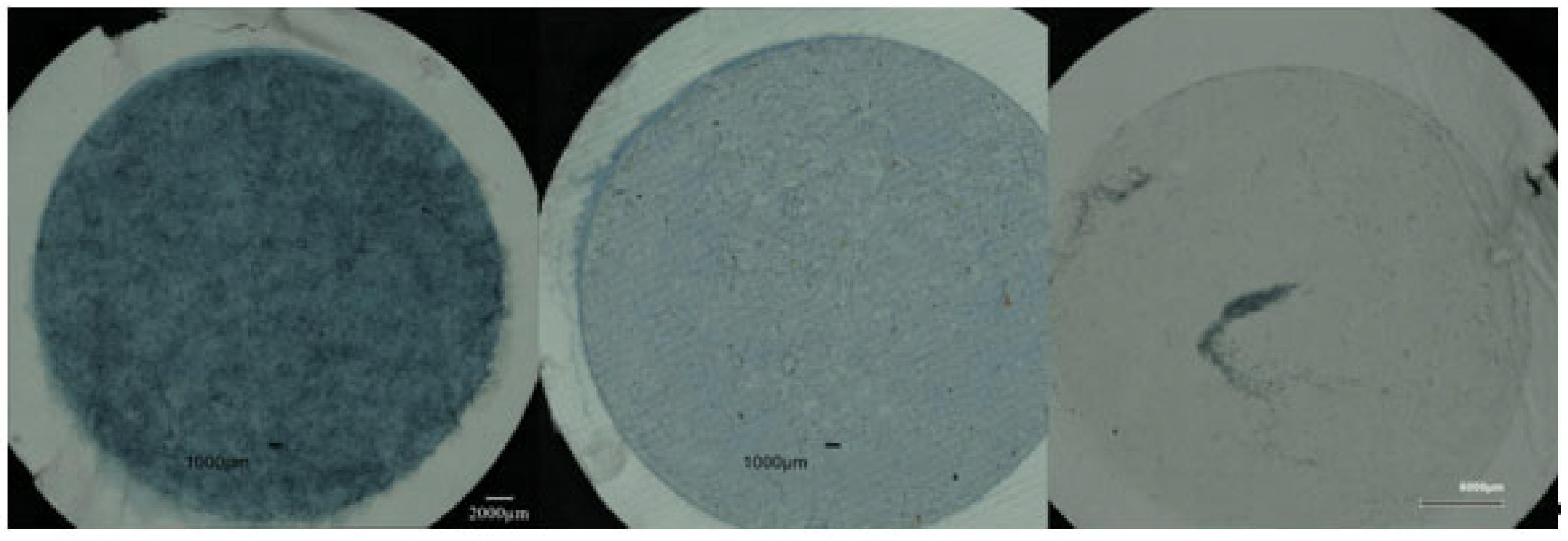

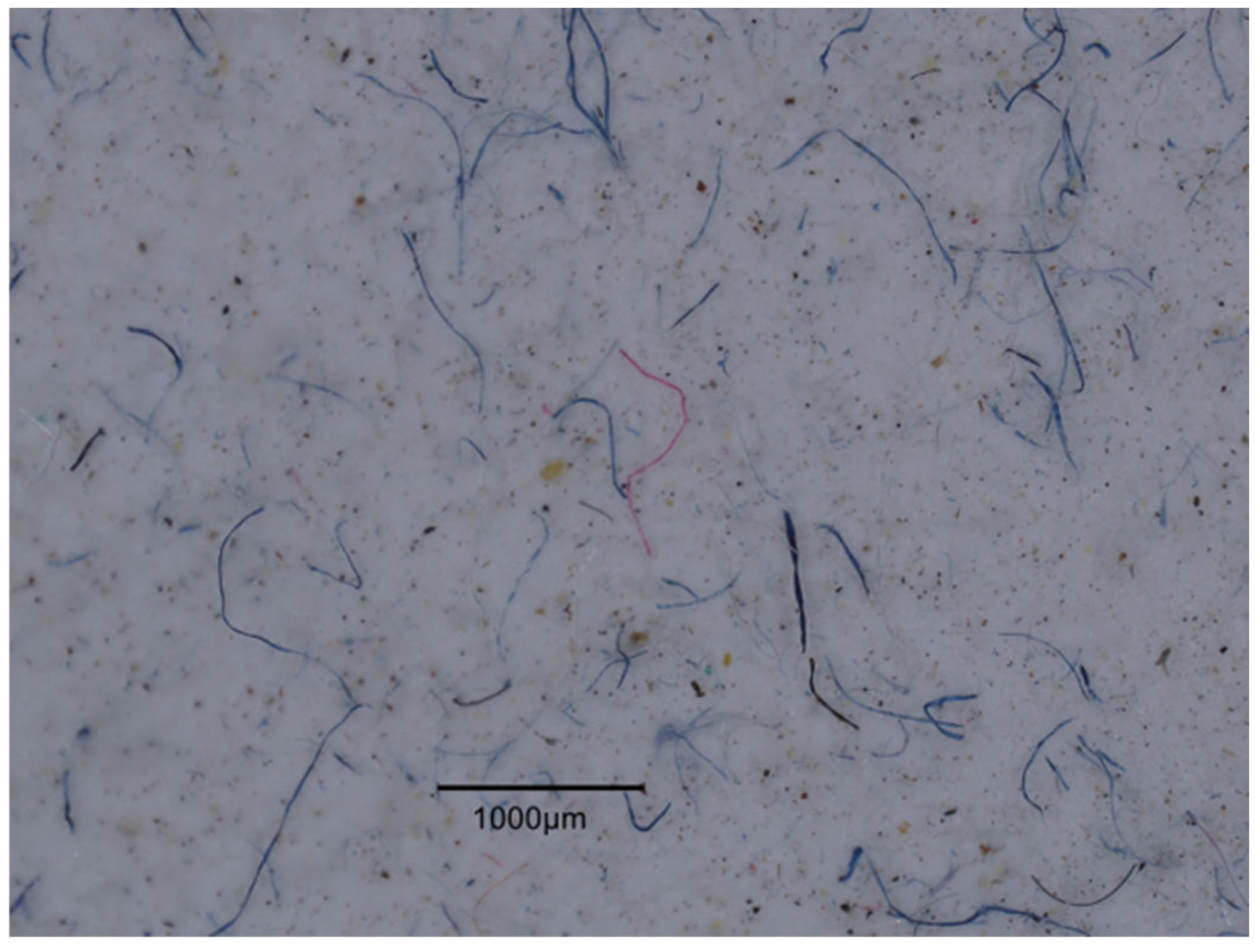

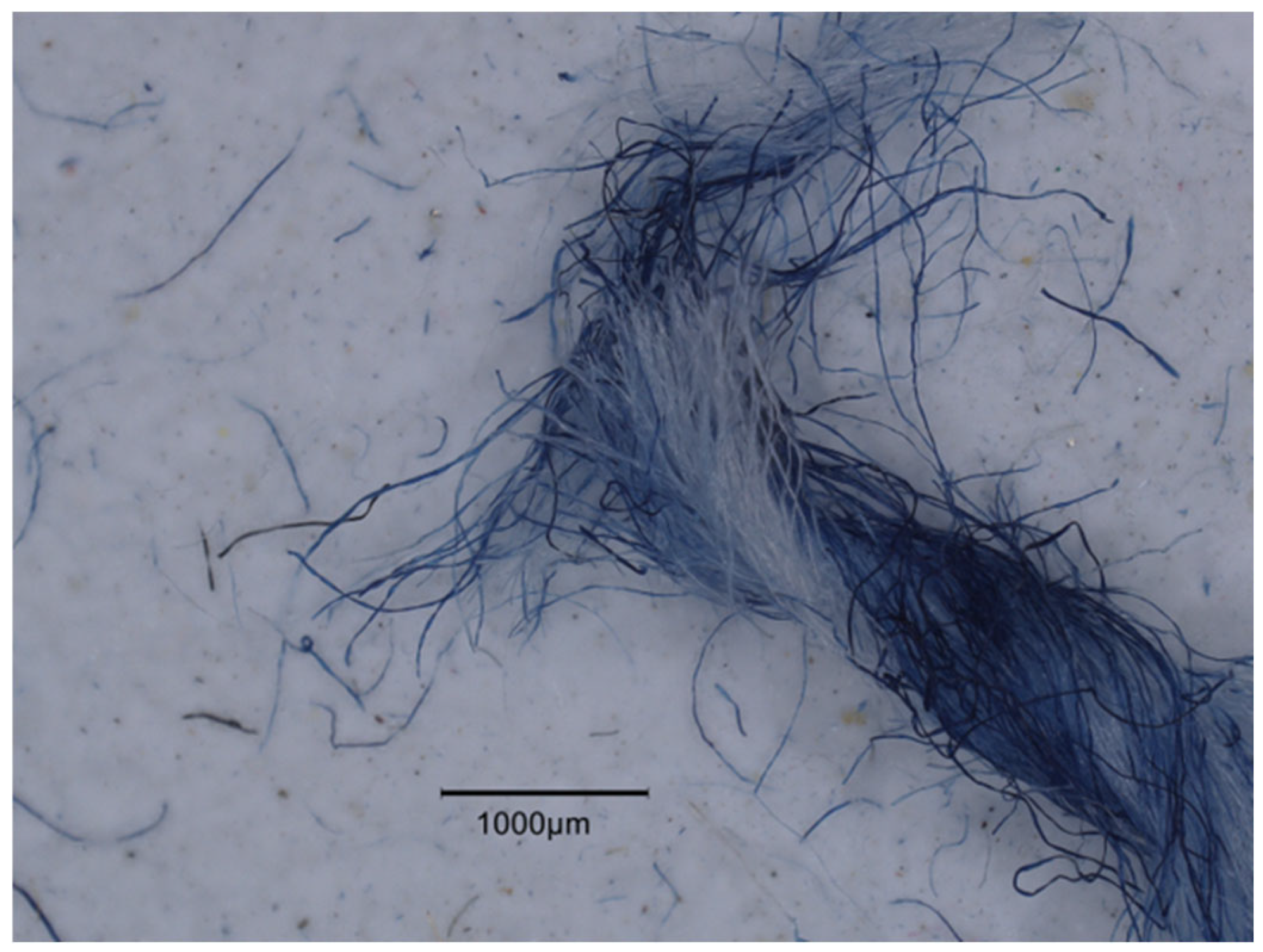

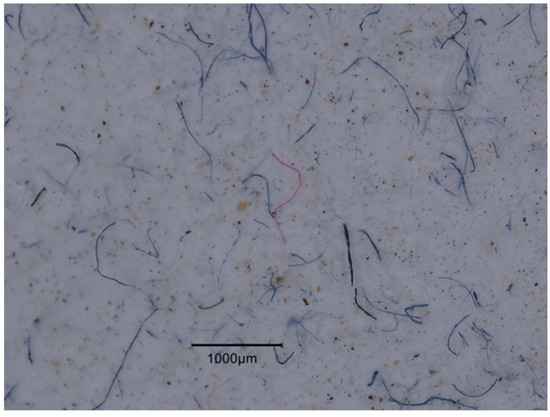

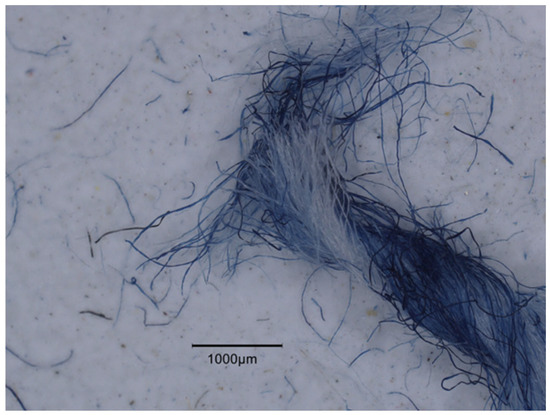

For an example of the diversity of fiber fragments and particulates and the resulting overall visual of the filters, see Figure 3. Many fiber fragments were individually deposited on the filters as seen in Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6. At times, clumps that indicate potential yarn structure, as illustrated in Figure 7, were found. The fiber fragments collected from the specimen filters were most prevalently blue and white. This finding was expected due to the blue and white yarns that comprised the denim fabric (Table 2), which is traditionally characterized by blue warp yarns and white fill yarns. Occasionally, a red, yellow, or black fiber fragment was found; this was also expected, as some detailing and thread used for the seams of the jeans were in these colors. The fiber fragments were most often identified as cotton, again expected due to the selection of 100% cotton jeans. A small number of synthetic fiber fragments were observed, likely due to sewing construction thread or possible transfer from storage and use, as these are secondhand items. Unidentified, non-fibrous particulates were also observed on some filters. The particulates ranged from light to dark in color and were granular. On some filters, there was a blue or grayish “coating.” It is speculated that this could be dye, if the dye were not cleared during the coloring process, or other additives on the denim fabric, or dirt. Figure 4 and Figure 6 illustrate the particulates and grayish color. Since the samples are secondhand and their history is unknown, any of these factors could contribute to this observation. Some microfiber studies [27,42] have noted similar particulate material on filters, whereas others have not [25,38,43]. Since particulate observation was not the focus of those studies, the absence of particulate material does not necessarily mean it is not present; it may simply have not been collected and noted during a study’s processing.

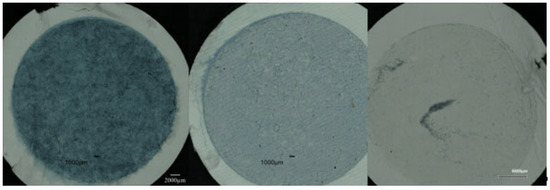

Figure 3.

Selection of processed filters collected. Top left to right: 2A, 10A, and 13B. Please note the varied appearance of the filters in color and fiber distribution. 50× magnification.

Figure 4.

Sample 15C has fiber fragments and granular particulates. 50× magnification.

Figure 5.

Sample 4C exhibits fewer fiber fragments, fewer particulates, and no coating of the filter when compared to other filters. 50× magnification.

Figure 6.

Sample 1B displays a grayish coating, particulates, and fiber fragments. An example of observed red and black fibers can be found in the center of the micrograph. 50× magnification.

Figure 7.

16A illustrates a large clump of white and blue cotton fiber fragments found on the filter. 50× magnification.

3.2. Fiber Fragmentation Measurements and Statistics

The average mass of the shed material was 0.0236 g (SHS) and 0.1014 g (CN), which indicates that SHS specimens shed only 23.3% of the mass of the CN specimens. The standard deviation for the mass of the released material from the SHS samples ranged from 0.000 g to 0.014 g. The average percentage of shed material released for the SHS samples was 0.0010%, with a standard deviation of 0.0022%. Previous studies that focused on multiple wash cycles and the shed mass of cotton garments found that with more cycles, less mass was accumulated [37,38], supporting the findings here. It is postulated in the current study that the CN samples had a larger shed mass release on average due to the lack of laundering prior to TM 212-2021 processing, and thus, very limited loss of fiber fragments and other materials until they were processed for this study. To better visualize the material released by the SHS samples, the 0.0236 g was from a sample that represents about 7.35% of the surface area of a man’s 30 × 30 jeans. If the average of the material released by the SHS samples were scaled up to account for the total surface area of a 30 × 30 man’s jeans, it would come to 0.3210 g, while the CN would be 1.380 g. If the 0.3210 g of material loss was constant for each wash cycle and the secondhand jeans were washed ten times a year, 3.210 g of materials would be released into the laundry wastewater for one pair of secondhand jeans. The cumulative significance of the shed material should be considered for all the secondhand jeans in use and being laundered.

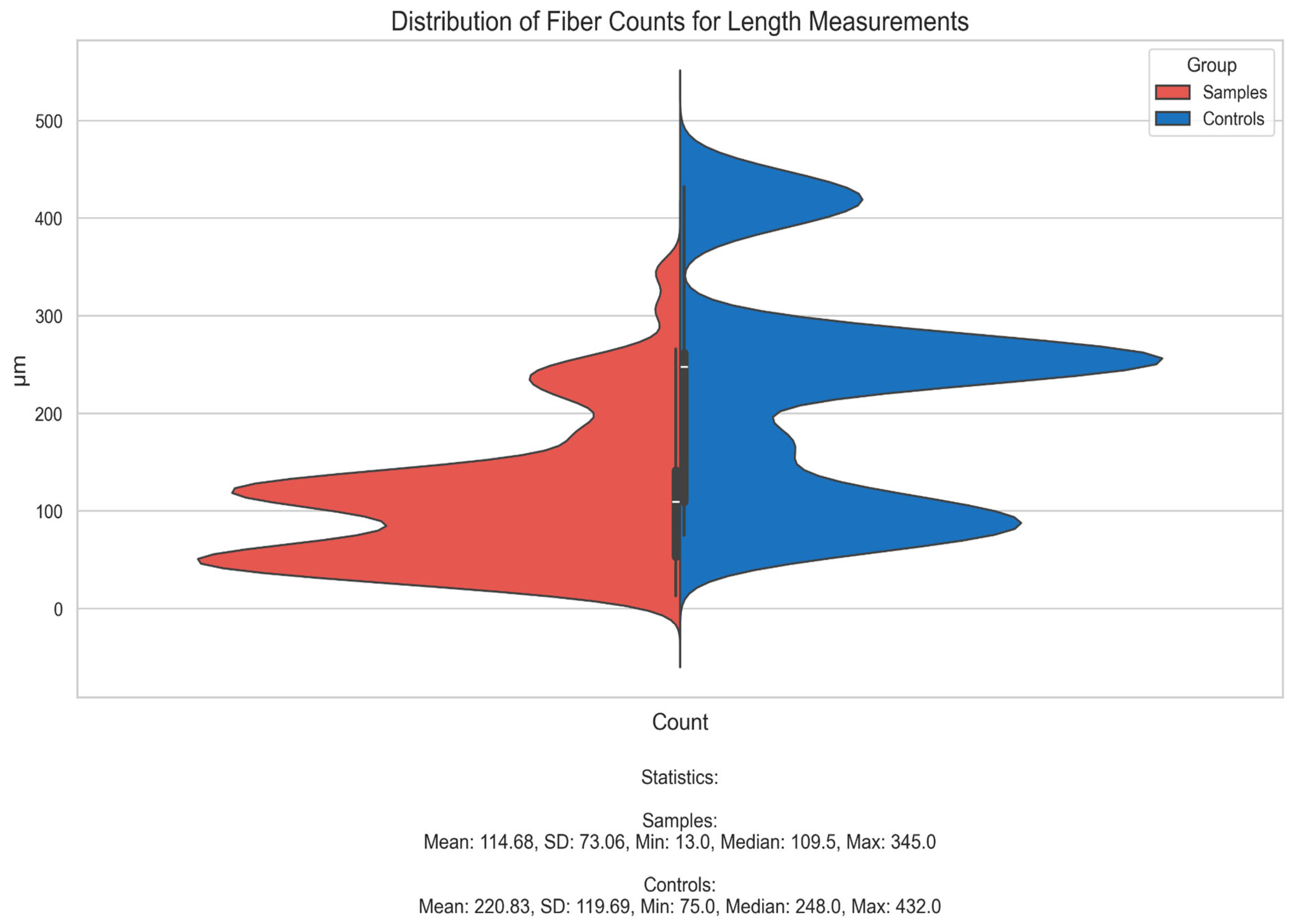

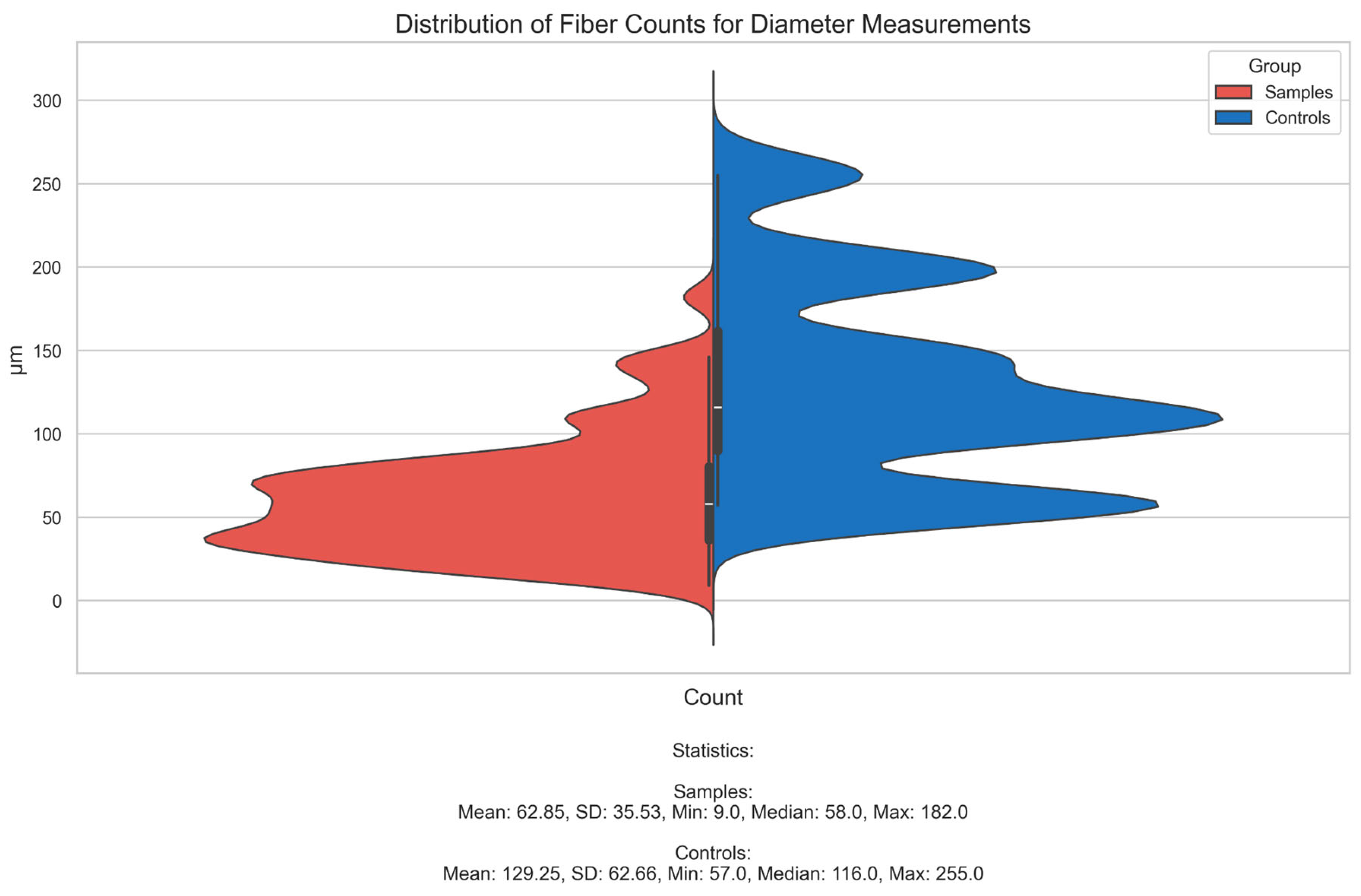

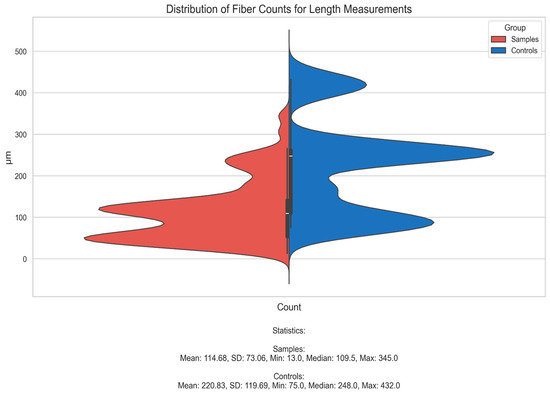

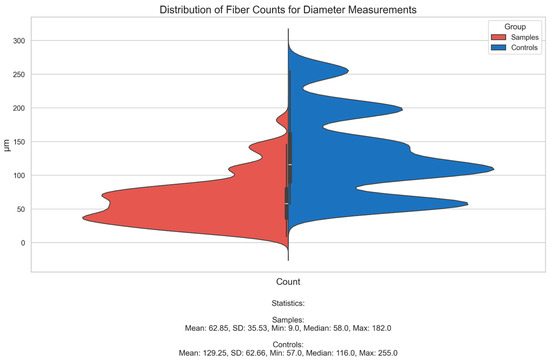

A summary of descriptive statistics for the fiber fragments can be found in Table 3. On average, the SHS produced longer (mean length 370.5 µm) and thicker fiber fragments (mean diameter 16.9 µm) but produced fewer fiber fragments (3093 fiber fragments per filter) when compared to CN (320.7 µm, 13.8 µm, and 5962 fiber fragments per filter, respectively). The length, diameter, and count data were determined to be non-parametric by D’Angostino-Pearson tests (all p-values < 0.00001). The distribution of fiber lengths and diameters (both in µm) can be visualized in Figure 8 and Figure 9, respectively. Other studies have also described the non-normal distribution of cotton fiber fragments [37,44]. To determine if there was a statistically significant difference between the CN and SHS, the data were evaluated by the Kruskal–Wallis H-test. Statistically significant differences between CN and SHS were found in fiber lengths (p-value < 0.00001), diameters (p-value < 0.00001), and counts (p-value 0.0022). The average diameters and lengths were consistent with those reported in other cotton fiber studies [45,46]. The size of the maximum diameters in the current study may be due to the release of cohesive clusters of fiber fragments from the yarns. The yarns would have many fibers in contact with each other due to the cohesion of cotton fibers, which is often associated with the fibers’ convolutions. In the findings, SHS produces a smaller number but larger average diameter and length of fiber fragments compared to CN. Studies focusing on recycled cotton for yarns and multiple wash cycles [43,47,48] found that longer fiber fragments were released from yarns made from “used” cotton (either in recycling the cotton or multiple washings) than from new cotton materials. This suggests a similar trend in fiber fragment length, as seen in the current study. A possible explanation for the data is that the CN shed a greater number of smaller fibers and fragments that were not completely processed out during yarn and fabric construction and were captured in their initial wash in this study. Through previous use and laundering, it is hypothesized that the SHS had already shed many of the smaller fragments and would produce larger fiber fragments in the test process due to previous wear and laundering.

Table 3.

Summary of fiber sample and control statistics.

Figure 8.

Distribution of fiber counts for length measurements. This provides a visual illustration of the maximum and minimum lengths for the SHS (red) and CN (blue) fiber fragments.

Figure 9.

Distribution of fiber counts for diameter measurements. This provides a visual illustration of the maximum and minimum diameters for the SHS (red) and CN (blue) fiber fragments.

4. Discussion

The current study provides an introduction to the environmental impact of secondhand cotton garments, particularly denim, through fiber fragmentation in laundry wastewater. Secondhand clothing provides a much-needed resource to fulfill growing garment demands while also mitigating water usage, greenhouse gas emissions, and landfill waste. Denim is a key player in secondhand sales, due to its durability and vintage cultural value. The results of the laundering experiment in this study yielded, on average, a smaller amount of fiber fragmentation material from secondhand jeans (23.2%) than that shed from new jeans. While this was less than new clothing, there is still a consequence of shed material, including dyes and processing chemicals that can contribute to anthropogenic contamination of the environment [25,26,49,50,51]. The impacts of this contamination can include potential effects on terrestrial and aquatic food webs through ingestion by multiple organisms [52,53,54]. In particular, cotton and nature-based manmade fibers have the potential to persist in the environment and carry chemicals associated with industrial treatments into ecosystems [55,56,57,58]. The fiber fragment size and frequency were also found to differ in secondhand (longer, larger diameter, fewer) versus new denim jeans (shorter, smaller diameter, and more common). The effects of the dimensions of fiber fragments, such as being shorter vs. longer, in the environment are still under investigation [50,52,59,60]. The amount of mass shed and dimensional information from this study of the fiber fragments is valuable information that can contribute to consumers’ and secondhand retailers’ decision-making processes when considering what is potentially entering the environment and making purchase decisions.

Future research can focus on the rate of change in the shedding of fiber fragmentation material from secondhand fabrics over multiple wash cycles, as well as the identification of particulate and coating materials found on the filters. The long-term decomposition of natural fibers and the chemistry they carry from industrial processes is another possible area of future study. Future studies could also develop protocols and data collection methods for secondhand clothing to conduct basic quality tests, such as tensile testing, pilling, and abrasion, for comparison with new materials. This comparison would help researchers to understand more about the potential use and secondhand lifetime duration, as well as estimate the entrance and exit points into circularity loops. Another path for future research would be to consider the fiber fragment contribution from recycled cotton yarns used to create new fabrics and garments, for comparison with the contribution from secondhand garments.

5. Conclusions

The data from the current study fills a gap in laundering studies that do not address fiber fragment analysis from secondhand clothing, specifically, natural fibers such as cotton. The thirteen men’s large 100% cotton jeans (SHS) were collected from local resale shops for a representative sample of jeans in the secondhand market. Men’s large jeans were selected as they provided areas of fabric for specimen creation without seaming or interruption. Two control jeans (CN) of a similar type were selected from new 100% cotton jeans. Fifty-two (thirteen jeans with four specimens each) secondhand samples and eight (two jeans with four specimens each) controls were processed according to the AATCC TM212-2021 Test Method for Fiber Fragment Release During Home Laundering with Drying Option A. After selection and processing, the filtered materials were analyzed for the mass of shed materials and the count, length, and diameter of the fiber fragments on randomly selected filters, totaling 26 SHS and four CN. This study concluded that the amount of fiber fragmentation material shed by SHS was 23.2% of that shed by CN. While this is less than new clothing, there is still shed material to consider, including dyes and processing chemicals that can contribute to anthropogenic environmental contamination. The fiber fragment size and frequency were found to have a statistically significant difference between SHS (average length 370.5 µm, average diameter 16.9 µm, and 3093 fiber fragments per filter) and CN (average length 320.7 µm, average diameter 13.8, µm, and 5962 fiber fragments per filter).

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data sets presented in this article are not readily available because the data are part of an ongoing study. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to amanda.thompson@ua.edu.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges the statistical advice of Lisa Davis.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Institution of Mechanical Engineers Engineering out Fashion Waste. Report. 2018, pp. 1–18. Available online: https://www.imeche.org/policy-and-press/reports/detail/engineering-out-fashion-waste (accessed on 19 April 2024).

- Boston Consulting Group. Driven by Gen-Z; Preowned Clothing is Expected to Make up 27% of the Average Resale Buyer’s Closet by 2023. Vestiaire Collective Report, 2019. Available online: https://www.bcg.com/press/5october2022-preowned-clothing-resale-buyers (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- THREDUP. Resale Report 2023. THREDUP. Available online: https://www.thredup.com/resale (accessed on 9 January 2024).

- Oscario, A. The transformation of second-hand clothes shopping as popular sustainable lifestyle in social media era. E3S Web Conf. 2023, 388, 04020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, J.; Quoquab, F.; Sadom, N.Z.M. Mindful consumption of second-hand clothing: The role of eWOM, attitude and consumer engagement. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2021, 25, 482–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djafarova, E.; Foots, S. Exploring ethical consumption of generation Z: Theory of planned behaviour. Young-Consum. Insight Ideas Responsible Mark. 2022, 23, 413–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, S.; Jiang, Z.; Jewon, L. Sustainable style without stigma: Can norms and social reassurance influence secondhand fashion recommendation behavior among Gen Z? J. Glob. Fash. Mark. 2024, 15, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnstone, L.; Lindh, C. Sustainably sustaining (online) fashion consumption: Using influencers to promote sustainable (un)planned behaviour in Europe’s millennials. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 64, 102775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Xu, H.; Song, H.-Y. Exploring the Key Factors Affecting Customer Satisfaction in China’s Sustainable Second-Hand Clothing Market: A Mixed Methods Approach. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sicurella, S. When Secondhand Becomes Vintage: Gen Z has Made Thrifting a Big Business. National Public Radio 2021. Available online: https://www.npr.org/2021/06/18/1006207991/when-second-hand-becomes-vintage-gen-z-has-made-thrifting-a-big-business (accessed on 30 May 2024).

- Gallagher, J. Thrift stores get pricier: Shoppers can’t discount impact of inflation and canny clothing resellers. Wall Str. J. 2022, A14. [Google Scholar]

- Hur, E. Rebirth fashion: Secondhand clothing consumption values and perceived risks. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 273, 122951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koay, K.Y.; Cheah, C.W.; Lom, H.S. Does perceived risk influence the intention to purchase second-hand clothing? A multigroup analysis of SHC consumers versus non-SHC consumers. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2023, 32, 530–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, R.; Bae, S.Y.; Xu, H. Second-hand clothing shopping among college students: The role of psychographic characteristics. Young Consum. Insight Ideas Responsible Mark. 2015, 16, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koay, K.Y.; Cheah, C.W. Effects of perceived risk on consumers’ intentions to purchase second-hand clothing: A comparison across four generations. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2025, 37, 3626–3644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuupole, E.; Appiah, N.A.; Kuupole, H.B.; Siaw, S.D.; Sefenu, F.Y.; Adjei, D.A. Assessing Consumer’s Purchase Practices and their Awareness on use and disposal of Second-hand Clothes. Fash. Text. Rev. 2025, 6, 285–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acquaye, R.; Seidu, R.K.; Eghan, B.; Fobiri, G.K. Consumer attitude and disposal behaviour to second-hand clothing in Ghana. Sci. Afr. 2023, 21, e01887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Encino-Munoz, A.G.; Yilan, G. Second-hand clothing and sustainability in the fashion sector: Analyzing visions on circular strategies through SWOT/ANP method. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 493, 144909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katende-Magezi, E. The Impact of Second Hand Clothes and Shoes in East Africa: PACT2 Study; CUTS International: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; Available online: https://www.cuts-geneva.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/PACT2-STUDY-The_Impact_of_Second_Hand_Clothes_and_Shoes_in_East_Africa.pdf (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Maximizemarketresearch.com. Report ID 186403. Available online: https://www.maximizemarketresearch.com/market-report/upcycled-denim-products-market/186403/? (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Singh, S. Global Denim Market Overview. Market Research Future. ID: MRFR/CR/5669-CR. 2021. Available online: https://www.marketresearchfuture.com/reports/denim-market-7135 (accessed on 8 March 2025).

- Levis Strauss & Co. The Lifecycle of a Jean: Understanding the Environmental Impact of a Pair of Levi’s® 501® Jeans. Available online: https://levistrauss.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Full-LCA-Results-Deck-FINAL.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. A New Textiles Economy: Redesigning Fashion’s Future 2017. Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/a-new-textiles-economy (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- EPA. United States Environmental Protection Agency. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/facts-and-figures-about-materials-waste-and-recycling/textiles-material-specific-data (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Athey, S.; Adams, J.K.; Erdle, L.M.; Jantunen, L.M.; Helm, P.A.; Finkelstein, S.A.; Diamond, M.L. The widespread environmental footprint of indigo denim microfibers from blue jeans. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2020, 7, 840−847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suaria, G.; Achtypi, A.; Perold, V.; Lee, J.R.; Pierucci, A.; Bornman, T.G.; Aliani, S.; Ryan, P.G. Microfibers in oceanic surface waters: A global characterization. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deheyn1, D.D.; Ayesu, J.B.; Skinner, B. Microplastics found in high concentrations around Kantamanto, the world’s largest secondhand textile market in Accra, Ghana: A citizen science study. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIlwraith, H.K.; Lin, J.; Erdle, L.M.; Mallos, N.; Diamond, M.L.; Rochman, C.M. Capturing Microfibers—Marketed Technologies Reduce Microfiber Emissions from Washing Machines. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 139, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Falco, F.; Gentile, G.; Di Pace, E.; Avella, M.; Cocca, M. Quantification of Microfibres Released during Washing of Synthetic Clothes in Real Conditions and at Lab Scale. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2018, 133, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Falco, F.; Cocca, M.; Avella, M.; Thompson, R.C. Microfiber Release to Water, Via Laundering, and to Air, via Everyday Use: A Comparison between Polyester Clothing with Differing Textile Parameters. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 3288−3296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Qiao, F.; Lei, K.; Li, H.; Kang, Y.; Cui, S.; An, L. Microfiber Release from Different Fabrics during Washing. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 249, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carney Almroth, B.M.; Åström, L.; Roslund, S.; Petersson, H.; Johansson, M.; Persson, N.-K. Quantifying Shedding of Synthetic Fibers from Textiles; a Source of Microplastics Released into the Environment. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 1191−1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Napper, I.E.; Thompson, R.C. Release of Synthetic Microplastic Plastic Fibres from Domestic Washing Machines: Effects of Fabric Type and Washing Conditions. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2016, 112, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirc, U.; Vidmar, M.; Mozer, A.; Kržan, A. Emissions of Microplastic Fibers from Microfiber Fleece during Domestic Washing. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 22206−22211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, M.A.; Crump, P.; Niven, S.J.; Teuten, E.; Tonkin, A.; Galloway, T.; Thompson, R. Accumulation of Microplastic on Shorelines Woldwide: Sources and Sinks. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 9175−9179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambrano, M.C.; Pawlak, J.J.; Daystar, J.; Ankeny, M.; Cheng, J.J.; Venditti, R.A. Microfibers generated from the laundering of cotton, rayon and polyester based fabrics and their aquatic biodegradation. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 142, 394–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sillanpää, M.; Sainio, P. Release of polyester and cotton fibers from textiles in machine washings. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 19313–19321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesa, F.S.; Turra, A.; Checon, H.H.; Leonardi, B.; Baruque-Ramos, J. Laundering and Textile Parameters Influence Fibers Release in Household Washings. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 257, 113553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazlehurst, A.; Tiffin, L.; Sumner, M.; Taylor, M. Quantification of microfibre release from textiles during domestic laundering. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 43932–43949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathinamoorthy, R.; Raja Balasaraswathi, S. A review of the current status of microfiber pollution research in textiles. Int. J. Cloth. Sci. Technol. 2021, 33, 364–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Association of Textile Chemist and Colorist AATCC TM212-2021: Test Method for Fiber Fragment Release During Home Laundering. Available online: https://members.aatcc.org/store/tm212/3573/ (accessed on 10 June 2023).

- Vassilenko, E.; Watkins, M.; Chastain, S.; Mertens, J.; Posacka, A.M. Domestic laundry and microfiber pollution: Exploring fiber shedding from consumer apparel textiles. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0250346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, H.; Zambrano, M.C.; Leonas, K.; Pawlak, J.J.; Venditti, R.A. Do Recycled Cotton or Polyester Fibers Influence the Shedding Propensity of Fabrics during Laundering? AATCC J. Res. 2022, 7, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Cho, Y.; Park, C.H. Effect of cotton fabric properties on fiber release and marine biodegradation. Text. Res. J. 2022, 92, 2121–2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradow, J.M.; Davidonis, G.H. Quantitation of Fiber Quality and the Cotton Production-Processing Interface: A Physiologist’s Perspective. J. Cotton Sci. 2000, 4, 34–64. Available online: https://cotton.org/journal/2000-04/1/upload/jcs04-034.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Elmogahzy, Y.E. Engineering Textiles—Integrating the Design and Manufacture of Textile Products, 2nd ed.; Woodhead: Cambridge, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Palacios-Marín, A.V.; Jabbar, A.; Tausif, M. Fragmented fiber pollution from common textile materials and structures during laundry. Text. Res. J. 2022, 92, 2265–2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, A.N.; Lara, L.Z.; De Falco, F.; Turner, A.; Thompson, R.C. Effect of the age of garments used under real-life conditions on microfibre release from polyester and cotton clothing. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 348, 123806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albarano, L.; Maggio, C.; La Marca, A.; Iovine, R.; Lofrano, G.; Guida, M.; Vaiano, V.; Carotenuto, M.; Pedatella, S.; Spica, V.R.; et al. Risk assessment of natural and synthetic fibers in aquatic environment: A critical review. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 934, 173398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanton, T.; James, A.; Prendergast-Miller, M.T.; Peirson-Smith, A.; KeChi-Okafor, C.; Gallidabino, M.D.; Namdeo, A.; Sheridan, K.J. Natural Fibers: Why Are They Still the Missing Thread in the Textile Fiber Pollution Story? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 12763–12766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Pleiter, M.; Velázquez, D.; Edo, C.; Carretero, O.; Gago, O.; Barón-Sola, A.; Hernández, L.E.; Yousef, I.; Quesada, A.; Leganés, F.; et al. Fibers spreading worldwide: Microplastics and other anthropogenic litter in an Arctic freshwater lake. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 722, 137904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selonen, S.; Dolar, A.; Jemec Kokalj, A.; Skalar, T.; Dolcet, L.P.; Hurley, R.; van Gestel, C.A.M. Exploring the impacts of plastics in soil—The effects of polyester textile fibers on soil invertebrates. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 700, 134451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jemec, A.; Horvat, P.; Kunej, U.; Bele, M.; Kržan, A. Uptake and effects of microplastic textile fibers on freshwater crustacean Daphnia magna. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 219, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlin, J.; Craig, C.; Little, S.; Donnelly, M.; Fox, D.; Zhai, L.; Walters, L. Microplastic accumulation in the gastrointestinal tracts in birds of prey in central Florida, USA. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 264, 114633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Athey, S.N.; Carney Almroth, B.; Granek, E.F.; Hurst, P.; Tissot, A.G.; Weis, J.S. Unraveling Physical and Chemical Effects of Textile Microfibers. Water 2022, 14, 3797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, C.; Windsor, F.M.; Munday, M.; Durance, I. Natural or Synthetic—How Global Trends in Textile Usage Threaten Freshwater. Environ. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 718, 134689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, L.; Kim, S.A.; Kim, T.H.; Kim, J.; An, Y.-J. Synthetic and Natural Microfibers Induce Gut Damage in the Brine Shrimp Artemia franciscana. Aquat. Toxicol. 2021, 232, 105748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateos-Cárdenas, A.; O’Halloran, J.; van Pelt, F.N.A.M.; Jansen, M.A.K. Beyond Plastic Microbeads—Short-Term Feeding of Cellulose and Polyester Microfibers to the Freshwater Amphipod Gammarus duebeni. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 753, 141859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, J.I.; An, Y.-J. Length- and Polymer-Dependent Ecotoxicities of Microfibers to the Earthworm Eisenia Andrei. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2022, 257, 109354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.S.; Kim, K.; Hong, S.H.; Park, K.-I.; Park, J.-W. Impact of Polyethylene Terephthalate Microfiber Length on Cellular Responses in the Mediterranean Mussel Mytilus galloprovinciallis. Mar. Environ. Res. 2021, 168, 105320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).