Abstract

The incorporation of recycled tyre polymer fibres (RTPF) in cementitious composites provides an effective and sustainable approach in tyre waste management while offering potential benefits in mitigating early-age volume deformations. This study evaluates the influence of RTPFs, used in dry (RTPFd) and pre-wetted (RTPFw) states, on key hydration processes governing autogenous shrinkage in cement pastes with w/c of 0.4 and 0.22. The results show that RTPF reduced workability and altered the setting process due to the fibre–matrix mechanical interactions. Incorporation of RTPFs induced changes in water distribution at the fibre surface, delaying self-desiccation and maintaining higher internal relative humidity. While RTPFs offer a beneficial reduction in autogenous shrinkage by 12–41% in mixtures with w/c of 0.4 and by 15–34% in mixtures with w/c of 0.22, RTPFs also increased porosity, which contributed to a reduction in 28-day compressive strength of up to 16%. These findings highlight the dual effect of RTPF on early-age performance and provide insight into their potential application in sustainable cementitious composites.

1. Introduction

The increasing annual demand for automotive tyres has resulted in a continuous rise in end-of-life tyres (ELTs), raising environmental concerns regarding landfilling, flammability, contaminant leaching and pest infestation. In response, the European Union has prohibited the landfilling of whole and shredded tyres and restricted their use as industrial fuel [1,2], promoting material recovery as the preferred option. Croatia has implemented similar measures through the Waste Management Act and Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) schemes, ensuring high collection and recycling rates. Although various recycling methods exist, mechanical recycling currently dominates the global tyre recycling market due to its cost-effectiveness and relatively low environmental impact [3,4]. This process typically yields 75–80% rubber, 10–15% steel, and about 10% polymer fibres. While crumb rubber and steel have established secondary material use streams, the recovery and utilisation of recycled tyre polymer fibres remain limited, despite their potential to partially replace virgin synthetic fibres in cementitious composites.

Recycled tyre polymer fibres (RTPF) consist mainly of polyester and polyamide [5,6]. Detailed analysis in [7,8] showed that these fibres comprise 60% polyethylene terephthalate (PET), 25% polyamide 66 (PA66), and 15% polybutadiene terephthalate (PBT). Residual rubber particles, dust, and trace compounds such as zinc oxide and accelerators may remain attached to the fibre surface and can interact with the alkaline pore solution, potentially influencing hydration reactions and pore solution chemistry [9,10,11]. In addition to the type of polymer, RTPFs are also considered hybrid due to their geometric characteristics. RTPFs generally fall within the microfibre range, with diameters between 8 and 38 µm and lengths below 12 mm, although recycling introduces significant geometrical and compositional variability [7,12,13]. Previous studies have reported tensile strengths of 475–760 MPa and elastic moduli of around 3–4 GPa for RTPFs [13,14], indicating that, despite their recycled nature, these fibres can provide a meaningful contribution.

RTPF have been successfully incorporated into various cementitious matrices, where their addition typically results in a moderate reduction in workability, an increase in entrapped air, and changes in fresh density [15,16]. Reported effects on compressive strength are less consistent; many studies indicate no statistically significant reduction at moderate dosages, while others highlight strength losses associated with increased porosity and a weaker fibre–matrix interfacial transition zone (ITZ) [13,14,17]. Several authors showed that RTPFs can reduce autogenous and early-age shrinkage, attributing this either to their potential as water reservoirs where RTPFs may retain a small amount of moisture within fibre bundles or on the fibre surface [15,16], or to the hydrophobic nature of the fibres, which promotes gradual release of retained liquid [13]. However, the underlying mechanisms remain only partially understood.

The effects are fundamentally linked to the evolution of pore structure and internal moisture transport, particularly in low w/c systems. Pore structure develops as hydration products progressively fill the space originally occupied by water and unhydrated cement, leaving capillary pores whose size and connectivity depend mainly on w/c and the degree of hydration [18]. In low w/c systems, limited internal water leads to rapid self-desiccation and reduced internal relative humidity associated with autogenous shrinkage [19,20,21], while superplasticizers—necessary to achieve workability at low w/c—further modify hydration and pore refinement, often intensifying early-age moisture loss [22,23,24,25]. In this context, polymer fibres can locally influence hydration and microstructural development through changes in packing density, bleeding channels along the fibre surface, and nucleation and growth of hydration products [26,27,28,29,30,31,32].

The influence of polymer fibres on hydration and microstructure has been widely studied for commercial fibres such as PP, PVA, PET, and PE, showing that their geometry, stiffness and surface chemistry control ITZ porosity, bond quality, and pore structure [28,29,33,34]. Hydrophilic fibres like PVA can promote local densification of the ITZ and refine pore structure, whereas hydrophobic fibres such as PP and PET often result in more porous interfacial regions, larger voids and reduced bond strength [35,36,37,38]. Both natural and synthetic fibres may also affect hydration kinetics through water absorption or desorption, ion complexation, or heterogeneous nucleation, thereby influencing early-age deformations and shrinkage [33,39,40,41].

In contrast, the specific role of RTPFs in hydration behaviour, internal relative humidity (IRH) evolution, pore morphology and autogenous shrinkage in high-performance systems remains insufficiently studied, mostly due to their heterogeneous composition, residual surface coatings, and contaminants. Most existing studies on RTPF in cementitious composites focus on mechanical performance, crack control, and overall shrinkage behaviour, while providing limited information on the underlying hydration processes and microstructural changes. In particular, there is a lack of systematic data on how the moisture condition of RTPFs (dry and pre-wetted) and the use of different w/c ratios affect heat evolution, degree of hydration, internal relative humidity, and pore size distribution. Furthermore, the relationship between RTPF-induced changes in porosity and the concurrent reduction in autogenous shrinkage and compressive strength has not yet been quantified consistently.

This study therefore aims to assess the role of recycled tyre polymer fibres (RTPFs) in the key hydration processes governing autogenous shrinkage in cement pastes with two w/c ratios of 0.40 and 0.22. Cleaned RTPFs were incorporated at a constant volume fraction of 1.1% of the cement paste volume in both dry and pre-wetted conditions. Effects on hydration are evaluated by testing isothermal calorimetry, internal relative humidity, and autogenous shrinkage, while microstructural development is characterised by mercury intrusion porosimetry, scanning electron microscopy, and compressive strength. The results are used to clarify the mechanisms by which RTPFs influence early-age behaviour, with particular emphasis on water redistribution, self-desiccation, and the interrelation of shrinkage mitigation and strength reduction.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

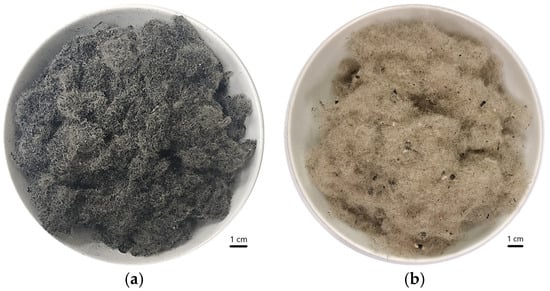

The materials used were ordinary Portland cement CEM I 52.5 N (Nexe d.d., Našice, Croatia), distilled water, recycled tyre polymer fibres (Gumiimpex GRP Ltd., Varaždin, Croatia), and polycarboxylate ether (PCE) superplasticizer (MasterGlenium ACE430 (BASF SE, Ludwigshafen, Germany)). All materials were stored for 24 h in the laboratory at a temperature of 20 ± 2 °C. The RTPF used in this study is obtained from the recycling of waste tyres by the local Croatian company Gumiimpex-GRP Ltd. The recycling process involved mechanical shredding, resulting in the recovery of rubber, steel, and polymer fibres. In this way, the RTPF also contains small rubber particles and dust. This initial state of the fibres is referred to ‘as received’. The cleaned RTPF that was used in this study was prepared following the cleaning process described in [7], which includes vibrating sieves where a controlled air stream separates the materials by density: heavier particles (rubber and dust) settle at the bottom, while the lighter RTPFs remain in the upper part of the device. Figure 1 shows the difference in RTPF as received (left) and after the cleaning process (right).

Figure 1.

Visual appearance of the RTPF: (a) as received and (b) cleaned.

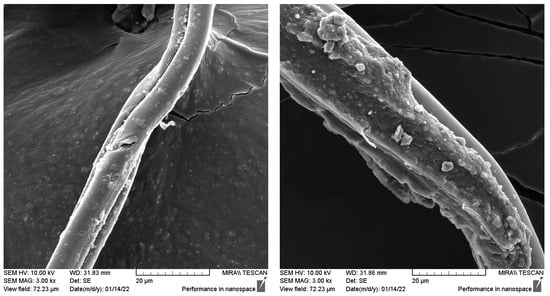

The average length of the RTPF was 8 mm and the average diameter was 18 µm, Figure 2, yielding an aspect ratio of 444. Given that these fibres are recycled materials, the variability in geometric properties is substantial, with coefficient of variation of 58% for length and 28.4% for diameter. Additional information regarding the characteristics of the RTPF used can be found in [8].

Figure 2.

SEM micrographs of cleaned RTPF.

2.2. Material Characterisation

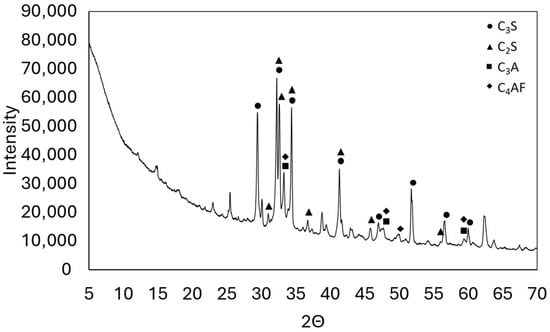

The chemical composition of the cement was determined by X-ray fluorescence (XRF) and loss on ignition (LOI), as presented in Table 1. Based on these values, the mineral composition of the cement was calculated using Bogue’s equations. The values obtained are 67.97, 6.51, 9.00, and 7.51 for C3S, C2S, C3A, and C4AF, respectively. XRD diffractogram is shown in Figure 3, while the Blaine method (ASTM C204 [42]) determined a specific surface area (fineness) of 2670.46 cm2/g for the cement used.

Table 1.

XRF analysis results of CEM I 52.5 N.

Figure 3.

XRD diffractogram of cement CEM I 52.5 N.

Two distinct fibre conditions were used in this study: RTPFd which refers to cleaned fibres stored under laboratory conditions, indicating a dry condition, and RTPFw, indicating clean fibres pre-wetted in water for 24 h before use. To assess how fibre moisture conditions influence fibre–matrix interactions and early-age behaviour, both fibre states were characterised in terms of surface wettability and water retention.

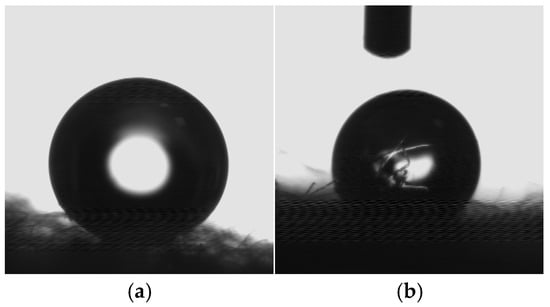

The wetting contact angle was determined with the OCA 20 goniometer (DataPhysiscs, Filderstadt, Germany) using distilled water while the water retention value (WRV) was determined according to the ASTM D2402-07:2018 [43] and DIN 53814:1961. The wetting contact angle for RTPFd was 179.74 ± 0.11. For RTPFw the wetting contact angle was 134.87 ± 9.46, reflecting a 24.97% lower value relative to RTPFd, indicating an increase in the hydrophilicity of the fibres following 24 h of water exposure. A high contact angle value indicates a strong hydrophobicity of the material, as illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Wetting contact angle test for (a) RTPFd and (b) RTPFw.

The water retention value (WRV) was determined according to the ASTM D2402 [43]. The value obtained for RTPFd was 0.36 ± 0.05%, while the value for RTPFw was slightly higher, at 0.56 ± 0.06%. Since the WRV method quantifies the amount of water that remains bound to the fibre despite mechanical efforts—spinning at 3000 rpm for 20 min—it is obvious that RTPFs tend to retain water on their surfaces rather than absorbing it. These results are consistent with the known characteristics of polymer fibres.

2.3. Methodology and Mix Design

A methodology was developed to account for different moisture conditions that the fibres may exhibit prior to mixing in cement composites. Eight mixtures were prepared: M0/U0 were reference mixtures without RTPF, while M1/U1 containing RTPFd, M2/U2, and M3/U3 incorporated RTPFw (Table 2). The M mixtures had a w/c of 0.4, while U mixtures had 0.22. The w/c ratios were selected to represent different hydration regimes, with w/c = 0.40 exhibiting moderate self-desiccation and w/c = 0.22 experiencing severe internal moisture deficiency and high autogenous shrinkage.

Table 2.

Mixture designation, fibre condition, and w/c ratios.

To ensure consistent RTPF content across mixtures with different w/c, the dosage was determined on a volumetric basis. Although the w/c ratio is expressed as a mass ratio, all mixture components were normalised to the same total volume. The combined volume of cement and water was then used as the reference volume for calculating the RTPF quantity, so that the mass of RTPF corresponded to 1.1% of this volume. This approach ensured an equivalent volumetric proportion of RTPF regardless of the mixture composition. For U mixtures, a superplasticizer was required to maintain workability, with a usage level of 1.45% by mass of cement.

The difference between M2/U2 and M3/U3 mixtures lies in how the RTPF was pre-wetted. In M2/U2, RTPF was pre-wetted using the mixing water itself, whereas in M3/U3, it was pre-wetted using additional water before being added to the mix, which resulted in a higher water-to-cement ratio.

All mixtures were prepared within a total mixing time of 9 min. First, water was mixed with RTPF, and superplasticizer for U mixtures, for 1 min at a lower spinning rate. Next, cement was added and mixed for 2 min at a lower spinning rate and 2 min at the higher spinning rate. A 2 min break was taken, followed by 2 min mixing at the higher spinning rate.

2.4. Methods

The consistency of cement paste was determined by using a flow table in accordance with EN 1015-3 [44], while the setting time was measured with an automatic Vicat apparatus according to EN 196-3 [45]. The relative humidity was monitored using the HC2-AW-USB measuring station (Rotronic Instrument Corp, Hauppauge, NY, USA). The cement paste was cast in small cylindrical moulds (Φ/h = 45/40 mm) inside the measuring station, closed with sensor and mechanically sealed in controlled laboratory conditions (20 ± 2 °C and 60% RH), while the measurement was performed with a time step of five minutes within a duration of seven days. Two samples were tested for each mixture, and the data were averaged. A comparable experimental setting was used in previously published literature [46].

Isothermal calorimetry experiments were conducted using a TAM Air calorimeter (TA Instruments, New Castle, DE, USA), wherein about 10 g of externally mixed cement paste was filled within 20 mL glass ampoules. The heat flow was recorded for 168 h at 20 ± 2 °C. The acquired data was also used to determine setting time, whereby the initial setting time (IST) is identified when the first derivative curve reaches its maximum value, and the final setting time (FST) is determined when the value approaches zero [47,48]. The differences between the setting times determined using the Vicat apparatus and isothermal calorimetry are primarily due to the methodology where the Vicat method focuses on the physical setting point, whereas isothermal calorimetry measures change in heat as a result of chemical reactions. It is assumed that these methods complement each other and provide a more comprehensive understanding of the setting of the cement paste.

The isothermal calorimetry data was further used to determine degree of hydration using Equation (1), where labels have the following meaning: α is the degree of hydration, Qt is the cumulative heat in time t, and Q∞ is the total cumulative heat determined using Equation (2), in which the share for mineral composition, w (%), is determined with Bogue’s equations, and heat values H (J/g) are determined as shown in [49].

Mercury intrusion porosimetry (MIP) was conducted using an AutoPore IV 9500 (Micromeritics, Norcross, GA, USA). The maximum applied pressure reached 206 mPa, allowing the detection of pore sizes as small as 5 nm. Hydration of the samples was stopped via immersion in isopropanol for 7 days, followed by vacuum drying for another 7 days. For testing, two specimens were fractured into smaller pieces, approximately 2.5 g each, and were sourced from the central region of the original sample.

The autogenous shrinkage of the paste mixtures was determined according to ASTM C1698 [50] using the sealed corrugated tubes in controlled laboratory conditions (20 ± 2 °C and 60% RH), and not subjected to external forces, from the time of final setting. The tests were carried out for seven days on three samples and the mean value is given.

Compressive strength was tested according to EN 1015-11 [51], and the tests were carried out at the age of 1, 3, 7, and 28 days for three samples at each age, and the mean value with the standard deviation is given.

Microstructure was examined using a scanning electron microscope (SEM, JEOL JSM IT500 LV, JEOL Ltd. Tokyo, Japan). The SEM analyses were performed in low-vacuum with a chamber pressure of 40–45 Pa, and an accelerating voltage of 15 kV. Polished cross-section of the samples was prepared to perform analyses.

A summary of all experimental procedures, including standards, specimen geometry, and number of tested samples, is provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of experimental procedures.

3. Results

3.1. Workability

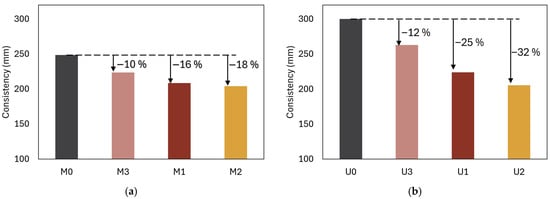

Figure 5 shows the influence of RTPF on workability, expressed in terms of consistency. The most significant difference was observed in M2 (−18%), followed by M1 (−16%) and M3 (−10%) compared to the reference M0. A similar trend was observed, to a greater extent, for the U2 (−32%), followed by the U1 (−25%) and the U3 (−12%) in comparison to the reference U0.

Figure 5.

Workability expressed by consistency for (a) M and (b) U mixture. The values of the total water content in the mixtures decrease from left to right.

All mixtures containing RTPFs exhibited lower consistency compared to the reference mixtures, regardless of the fibre condition. This trend demonstrates the greater influence of the fibres as elongated obstacles on workability as previously described for polymer fibres [37]. It is further shown that even the additional water in the M3 and U3 did not help achieve the level of consistency of the reference M0 and U0. The results align with the study conducted by Chen et al. [14], which demonstrated that RTPF pre-wetted in mixing water resulted in mixtures with reduced consistency compared to those with dry RTPF.

3.2. Setting Time

The influence of the RTPF on the setting time is shown in Table 4. In M mixtures, the RTPF influence is mainly in the form of a physical barrier to movement and network formation which leads to a faster initial setting time of the M1 (−18%) and M2 (−15%) compared to the reference M0. In M3, the additional water maintains the overall water balance, but the fibres stiffen the matrix and act as nucleation sites, slightly accelerating internal network formation and shortening the initial setting time (−7%), which is still accelerated compared to M0. Based on the results, the influence of the RTPFs on the initial setting time of M mixtures was largely physical. Only minor differences were caused by the different RTPF pre-treatments. The differences determined by isothermal calorimetry are less obvious, and are less than 2% for all the mixtures, as the RTPFs did not have a significant effect on chemical reactions. The trend in the initial setting is also followed with the final setting time.

Table 4.

Setting time for M and U mixtures.

For U mixtures, the trend of physical influence that can be observed with the Vicat apparatus remains, only to a greater extent, showing the faster initial setting for U1 (−46%), U2 (−38%), and U3 (−24%) compared to the reference U0. A difference is now visible with final setting time which is accelerated for U1 (−13%) and U2 (−30%), but for U3 mixture (+7%), the additional water resulted in a change in the trend due to the higher water scarcity in the system. The differences for reference and mixtures with RTPFs measured with isothermal calorimetry differ only up to 5%. Nevertheless, the differences in setting time of U mixtures determined with these two methods are attributed to the water scarcity and the use of PCE superplasticizer, which has a retarding effect on the hydration process and is visible with isothermal calorimetry [23].

3.3. Heat of Hydration and Degree of Hydration

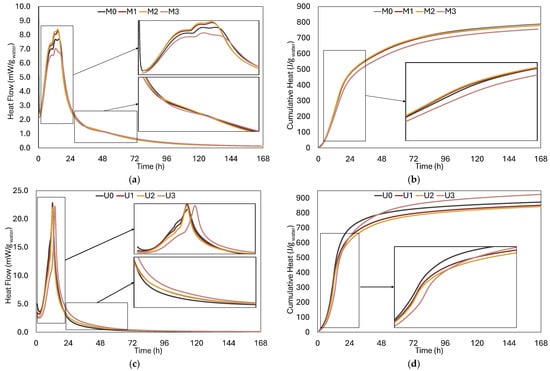

The results of the heat flow measurement indicate that the M mixtures with higher w/c exhibit lower and broader main peaks in contrast to the U mixtures with lower w/c, as shown in Figure 6. The findings are consistent with earlier studies [47,52], which indicate that an increased w/c leads to a greater dilution of cement in the solution, resulting in a lower hydration rate and reduced heat generation during the early stages of hydration. Furthermore, reduced water availability accelerates the hydration reaction, leading to increased initial heat generation due to the proximity of cement particles and the increased intensity of the reaction [53].

Figure 6.

Heat flow and cumulative heat for (a,b) M and (c,d) U mixtures.

In M mixtures, RTPF pre-treatment had little influence on the acceleration period. Nevertheless, it did result in a distinct enhancement of heat flow peak, indicating that more material is involved in generation of hydration heat, which was evidently linked to the availability of water for hydration. A similar result was observed for the M1 and M2, both of which contained the same quantity of water. The heat flow results demonstrate that, compared to the reference M0, RTPF retains a certain volume of water, leading to lower water content in M1 and M2. Conversely, incorporating RTPFw into M3 resulted in increased water content and decreased heat flow, further illustrating RTPF’s capacity to influence water consumption.

The influence of RTPFs was particularly noticeable in U mixtures with lower relative humidity. It was observed that RTPFs altered the acceleration phase. The peak values were significant, with the maximum values recorded for U1 and U2 exceeding that of the reference mixture U0 by 10.45% and 6.45%, respectively. In the U3, the deceleration effect was detected. In particular, the peak heat flow in the U3 mixture was delayed by 1.72 h compared to the reference U0. Cumulative heat measurements also revealed a significant increase for the U3 after 24 h, and this increase continued after 48 h.

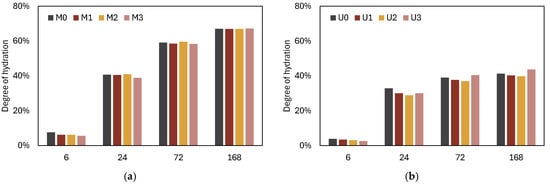

The degree of hydration was determined during the initial hydration phase and followed for 6, 24, 48, and 168 h, as shown in Figure 7. The results showed that the degree of hydration (DoH) was initially slightly lower for the mixtures with RTPF, with a greater extent for U than M mixtures. The effects in U mixtures were more pronounced due to the lower w/c ratio and the retarding influence of the superplasticizer. Further hydration, until 168 h, lead to an equalisation of the DoH values for M mixtures, while for the U mixtures, U1 and U2 still showed 3% lower values while U3 showed a 6% increase in value, compared to reference mixture without fibres.

Figure 7.

Degree of hydration for (a) M and (b) U mixtures.

3.4. Pore Morphology

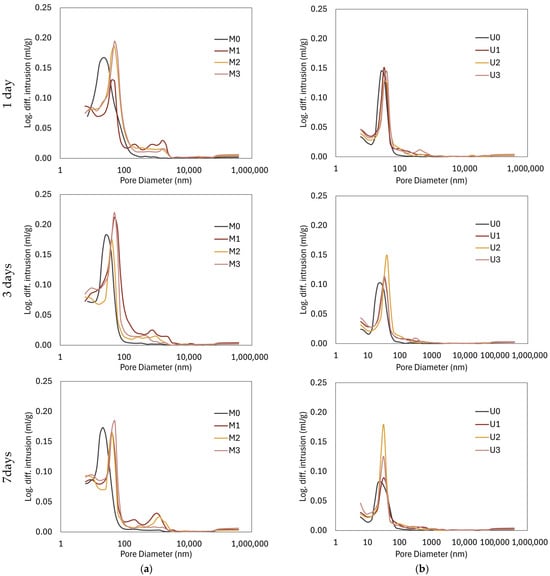

The first derivative of the cumulative pore volume curves is presented in Figure 8, while the porosity of the mixtures over time is summarised in Table 5. The results confirm that pore volume reduced over time and that lowering the w/c ratio from 0.4 to 0.22 reduces porosity as expected, since a lower w/c ratio leads to a denser microstructure [54].

Figure 8.

First derivative of the cumulative pore volume results for (a) M and (b) U mixtures.

Table 5.

Total porosity of the M and U mixtures.

An exception to this behaviour was observed with the M1 mixture, despite a greater number of repeated examinations, where porosity increased after 3 days of hydration compared to after 1 day, followed by a decrease after 7 days. This change was accompanied by an increase in the critical pore entry radius, which increased from 40.32 nm on day 1 to 50.42 nm on day 3, and decreased to 40.32 nm after 7 days. The deviation from the trend was assigned to inaccessible porosity, i.e., pore refinement and enclosure by facilitating the deposition of hydration products on their surface and an increase in the proportion of tiny pores or ink-bottle pores that are inaccessible to mercury [55]. It is important to note that MIP technique detects connected pores accessible to mercury under pressure, potentially overlooking isolated or disconnected pores.

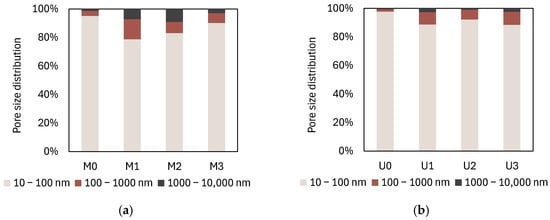

For both M and U mixtures, noticeable differences in the influence of RTPFs on porosity are observed within the pore range of <100 nm, depending on the condition of the fibres, as seen in Figure 9. The peak values shift toward larger diameters, while in U mixtures, the peaks also reflect an increase in mercury intrusion quantity. For pores larger than 100 nm, there is a consistent increase in volume relative to the reference mixture, with this effect being more pronounced in M mixtures. The difference was more pronounced for mixtures with RTPFd in comparison to RTPFw. This trend is also reflected in the increase in total porosity, as shown in, Table 5.

Figure 9.

Distribution of micro, mezzo and macro capillary pores: (a) M and (b) U after 7 days.

3.5. Change in Internal Relative Humidity

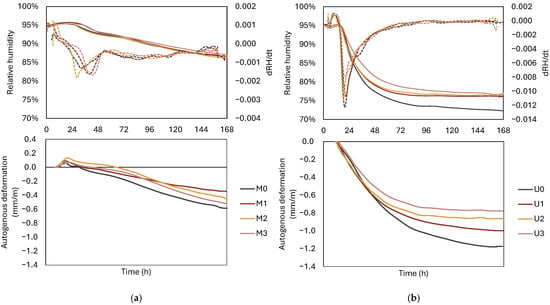

Figure 10 illustrates the impact of RTPFs on the relative humidity of cement paste. The graphs show the values for internal relative humidity and first derivative determining the rate change in RH in time. The relative humidity change for the duration of test was less than 10% for the M mixtures and 20% for the U mixtures, indicating greater self-desiccation. Namely, the water content decrease was reflected in reduced water availability for hydration, resulting in desaturation of the finer pores and thus reduced RH [53].

Figure 10.

Autogenous shrinkage and internal relative humidity with first derivative in time for (a) M and (b) U mixture.

The M mixtures exhibited no substantial variations in relative humidity are attributable to the incorporation of fibres within the observed timeframe. During the testing period, the high RH in the cement paste indicates sufficient water content and the presence of the RTPF did not disturb the process.

Moisture variations in internal RH for U mixtures from 12 to 24 h, as indicated by dRH/dt curves, are directly associated with the faster ongoing hydration process. Despite observable moisture loss, mixtures with RTPFs exhibited higher internal RH compared to the reference U0. The results indicate that RTPFs slowed the process of water consumption and resulted in a higher RH of the paste of approximately 6% at the end of the test period, compared to the reference mixture U0.

Although the changes are small, the fibres tend to change the water content at the micro level, i.e., along the fibre surface, which reduces water loss and ultimately leads to higher RH. In U3 mixtures, higher internal humidity was sustained relative to other U mixtures, particularly U0, due to the additional water introduced into the system.

3.6. Autogenous Shrinkage

Autogenous shrinkage results are shown in Figure 10, representing the mean value where the time zero is defined based on the setting time determined using the isothermal calorimetry method, as shown in Table 4. The results obtained indicate that the influence of RTPF varies, depending on the w/c ratio.

In the M mixtures, a swelling peak is observed, which is further increased by the presence of RTPFs. The peak swelling values for M1 and M2 mixtures were 41% and 108% greater compared to M0, respectively, while the value for the M3 mixture was approximate to the reference, although with a certain time delay. Bleed water reabsorption is the most likely cause of the initial expansion, mostly associated with water-to-cement ratios above 0.30 [56]. The final autogenous shrinkage values for M1, M2, and M3 mixtures were 41%, 23%, and 12% lower compared to M0.

In the U mixtures, a swelling peak was not observed but the trend for the mixtures with RTPF changes compared to that of U0. That is, up to 36 h, the value of autogenous shrinkage is similar, but after 36 h, there is a decrease in the value of autogenous shrinkage in mixtures with RTPF. The shrinkage value after 7 days for U1, U2, and U3 was 15%, 27%, and 34% lower compared to U0, respectively. The highest difference with the U3 was attributable to the additional water, while the values for U1 and U2, although less significant, still improved in terms of the autogenous shrinkage value after 7 days.

3.7. Compressive Strength

The results of the compressive strength tests are shown in Table 6. The results are given for 24, 72, and 168 h as well as for 28 days.

Table 6.

Compressive strength values for M and U mixtures.

For the M mixtures, the influence of RTPF was more pronounced, especially for M3 (higher water content), which showed a continuous decrease, with a 35% drop after 24 h. M1 and M2 mixtures showed an increase of 3% and 7%, respectively. After 28 days, M1, M2, and M3 achieved a decrease of 6.5%, 5%, and 16% compared to the M0.

For the U mixtures with RTPF, no significant changes were observed after 24 h, except for U3 (higher water content), which deteriorated by 10%. After 28 days, U1, U2, and U3 showed a decrease of 7%, 6%, and 10%, respectively, compared to the U0.

The results on compressive strength presented in the literature are not unambiguous, i.e., there is no uniform trend in the influence of the RTPF. Rather, the effects of the remaining rubber content and the changes in porosity as well as modified interfacial transition zone, which affect the changes in compressive strength, are more significant, i.e., the influence of the cement matrix is greater than the influence of the RTPF [7,14,16].

4. Discussion

This study investigated the influence of RTPFs on the early-age properties of cement paste mixtures under two contrasting hydration regimes defined by w/c of 0.4 (M mixtures) and 0.22 (U mixtures). The results show that RTPFs influence the response through two coupled mechanisms: moisture redistribution and microstructural modifications associated with ITZ formation and fibre-induced heterogeneity. The balance between these mechanisms depends strongly on water availability.

The earliest effect of RTPF can be seen in the workability results (Figure 5), which are determined by the consistency of the mixtures shortly after mixing. At this point, when free water is still abundant, regardless of the w/c, the dominant influence of RTPF is as an elongated inclusion which increases internal resistance and friction, increasing the probability of contacts and network formation, thereby decreasing the workability [57,58,59,60]. The restrictive effect of the RTPF on the workability of the mixtures was not mitigated even in the M3 and U3, indicating that the additional water was not sufficient to counteract the influence of the fibres’ physical role.

The effect persists during setting. The M mixtures with RTPF showed accelerated initial setting determined by Vicat, as shown in Table 4, and were attributable to the formed mechanical bonds, indicating setting time, as determined with Vicat forming earlier than chemical bonds, as determined with isothermal calorimetry, because hydration reactions were influenced primarily by water availability. In U mixtures, the use of a superplasticizer resulted in a clear delay in the heat flow peak, enhancing the divergence between physical and chemical setting indicators.

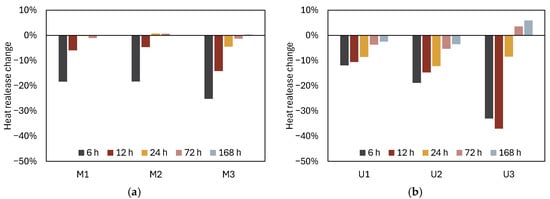

The influence of water redistribution due to the incorporation of RTPF was further showed in Figure 11, where a heat release change was observed compared to the reference mixtures. Mixtures containing RTPF retained more water, resulting in higher internal RH, as seen in Figure 10. However, this retained water was not readily available for cement hydration, leading to a slower hydration reaction and reduced heat release. Consequently, the degree of hydration was also lower at a very early age (Figure 7a,b). This behaviour is consistent with the concept of non-classical internal curing, where fibres redistribute but do not absorb or store significant amounts of water.

Figure 11.

Heat release change in relation to the reference for (a) M and (b) U mixtures.

By the end of the first 24 h, differences in hydration and microstructural development between the M and U mixtures begin to differentiate due to variations in their w/c ratio. In M mixtures (w/c = 0.40), internal RH remains high (>90%), which limits moisture gradients and prevents mobilisation of fibre-retained water. As a result, RTPF has only a marginal effect on heat evolution and DoH and primarily act as physical inclusion. In U mixtures (w/c = 0.22), strong self-desiccation (change of 20%) drives water consumption from the system. Here, RTPF mixtures maintain RH by up to 6% higher than U0, delaying RH drop and modifying calorimetry acceleration peaks. The U3 mixture, containing additional water, exhibits delayed but greater cumulative heat, indicating water release once RH gradients become sufficiently strong.

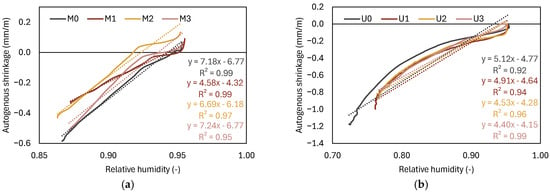

When correlating RH and autogenous shrinkage values, mixture M1, which shows lower autogenous shrinkage, also shows lower slope compared to M0, as shown in Figure 12. This indicates that the dependent variable, i.e., autogenous shrinkage, progresses at a slower rate, but with strong correlation for both.

Figure 12.

Autogenous deformation and relative humidity correlation for (a) M and (b) U mixture.

The effect of pre-wetted RTPF in M2 also shows a reduced slope compared to M0, though the effect is less pronounced than in M1. Despite a very strong correlation obtained, the data points show increased variability, particularly in the region of higher RH.

Furthermore, the reference mixture M0 and M3 mixture with additional water exhibit nearly identical slopes (7.18 and 7.24), indicating a similar rate of change. The lower RH in U mixtures prevented initial autogenous swelling, meaning autogenous deformation manifested solely as shrinkage. Mixtures with RTPF (U1, U2 and U3) obtained a slower progression of autogenous shrinkage, as higher RH levels in the very early stage promote the delay of self-desiccation.

The hydration process is similarly characterised by a slower progression, as seen in Figure 7 and Figure 11, which in turn leads to a reduction in autogenous shrinkage. Despite the changes in heat release and the degree of hydration reaching comparable levels by the end of the test period, the autogenous shrinkage remains lower in mixtures containing RTPF.

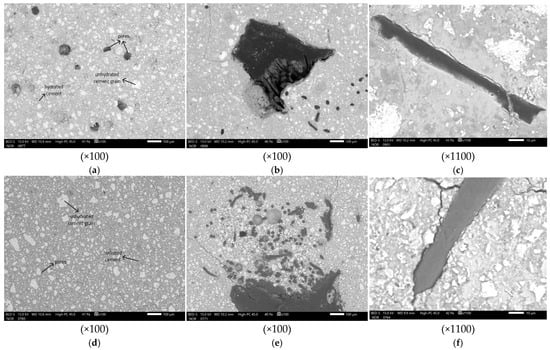

Microstructural investigations provide an explanation for the observed changes in strength and shrinkage. MIP results revealed that RTPF increases total porosity and shifts the pore size distribution towards larger pore entry radius, particularly in the M mixtures, as seen in Figure 9. The proportion of coarse pores (>100 nm) was higher in RTPF-containing mixtures, which is consistent with the presence of fibre–matrix interfacial zones and air pockets generated during mixing. In the denser U mixtures, the relative changes in porosity were smaller but still detectable, indicating that fibre-induced heterogeneity is partially moderated by the compact matrix [35]. SEM observations further support this where local discontinuities and more porous regions near RTPF and rubber residues are present. SEM images of the M mixture exhibited a more porous structure and fewer unhydrated cement particles (Figure 13a). U mixtures showed a less porous structure but had a higher content of unhydrated cement particles (Figure 13d). The differences obtained were also confirmed with the previous test, as shown in Table 5 and Figure 7. Different ITZ characteristics and disturbances in cement matrix continuity were detected in the mixtures as ascribed to rubber residue (Figure 13b,e) and RTPF (Figure 13c,f). The inclusion of rubber particles introduces discontinuities due to impeded bonding and limited mechanical interlocking. Rubber particles also attract air bubbles during mixing, increasing porosity and influencing the matrix disruptions.

Figure 13.

SEM micrographs after 1 day for (a) M0 and (d) U0; rubber residues in (b) M1 and (e) U2; and RTPF in (c) M1 and (f) U1.

In several SEM images, cracks were observed along the inclusion boundaries at the interface transition zones (ITZs). While it indicates possible weaknesses or discontinuities at the ITZ between the RTPF and the cement paste, caution is needed when interpreting these features. The SEM observations can be influenced by sample preparation, particularly polishing [54]. Due to the significant differences in hardness between the cement paste, rubber, and fibres, erosion of the ITZ areas can occur, exaggerating or even creating cracks that may not be representative of the actual microstructure of the material. Therefore, although the presence of cracks appears as a recurring feature in the images, further investigation using alternative methods would be required to confirm the integrity and behaviour of the ITZs.

A similar ITZ was described around the polymer fibres which contribute to the overall porosity of fibre-reinforced composites [29,35]. With flexible fibres, the mechanism of ITZ formation involves a combination of factors that can lead to a more compact and denser ITZ compared to rigid fibres due to bending and conforming to the surrounding cement paste, reducing the gap between the fibre and the matrix. Furthermore, different wetting properties would affect different ITZ properties [61].

Mixtures with RTPF exhibit a moderate reduction in compressive strength compared to the reference M0/U0, which is more pronounced in the M group (up to ~16% at 28 days) and smaller in the U group (<10%). The strength loss correlates with increased porosity and coarser pore structures, rather than with any clear inhibition of hydration. Degree of hydration estimated from calorimetry correlates well with compressive strength, indicating that, at the paste scale, the main effect of RTPF is not to stop hydration but to redistribute water in space and to introduce localised weak zones. The effect of additional water in the M3 mixture was mostly visible as a temporary delay in strength development and an increase in porosity, indicating that simply increasing mixing water primarily raises the effective w/c rather than providing targeted internal change, while the additional water in U3 leads to delayed but enhanced heat release and a more sustained rate of strength gained at early age.

5. Conclusions

This paper primarily focused on assessing the effects of recycled tyre polymer fibres (RTPF) on hydration properties governing autogenous shrinkage during the early age. Based on the results, the following conclusions can be drawn:

- ―

- RTPFs decrease consistency and shorten setting time, by acting as long inclusions that require wetting, and they increase internal fraction, restrict movement, and accelerate network formation. These effects are more pronounced in low-w/c mixtures, where the matrix is stiffer and more sensitive to fibre-induced hindrance.

- ―

- The RTPFs retain a limited amount of water on their surfaces and in fibre bundles, releasing it when strong moisture gradients develop, particularly in low w/c systems. RTPF-containing mixtures maintained higher RH than the reference by up to ~6% after several days.

- ―

- RTPF alters hydration kinetics locally but does not suppress overall hydration. Calorimetry showed modified acceleration peaks and cumulative heat, especially in mixtures with pre-wetted RTPF and additional water. However, DOH values converge towards those of the reference mixtures by 7 days.

- ―

- RTPF inclusion resulted in lower autogenous shrinkage, with the effect being more pronounced in mixtures with lower w/c. By prolonging higher internal RH and modifying pore structure, RTPF lowers the rate and magnitude of autogenous shrinkage. The beneficial effect is strongest when RTPFs are pre-wetted and additional water is supplied by RTPFs, rather than simply added to the mixture.

- ―

- Mixtures with RTPF indicate higher total porosity and coarsen the pore size distribution, particularly for M mixtures. RTPF-related ITZs formed and entrapped air, and increased the volume of coarse pores.

- ―

- Strength reductions are modest—up to ~16% at 28 days for M mixtures and below 10% for U mixtures—and correlate with increased porosity and coarser pores, not with fundamental changes in bulk hydration. All U mixtures still achieve compressive strengths above 100 MPa at 28 days.

The findings indicate that the incorporation of RTPFs had a positive effect on reducing early-age autogenous shrinkage. This behaviour was achieved by two mechanisms: (a) water redistribution during the early phase, causing slower self-desiccation, and (b) higher total porosity as well as higher proportion of larger pores, which subsequently resulted in lower compressive strength.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, K.D. and A.B.; methodology, K.D. and A.B.; validation, A.B. and V.Z.S.; formal analysis, K.D. and A.B.; investigation, K.D.; resources, A.B.; data curation, K.D.; writing—original draft preparation, K.D.; writing—review and editing, A.B. and V.Z.S.; visualisation, K.D.; supervision, A.B.; project administration, A.B.; funding acquisition, A.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The presented research is part of the scientific project “Cementitious composites reinforced with waste fibres”—ReWire (UIP-2020-02-5242), funded by the Croatian Science Foundation and carried out at the University of Zagreb Faculty of Civil Engineering.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset is available upon request from the authors.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks go to Gumiipex—GRP d.o.o. (www.gumiimpex.com) (accessed on 3 December 2025) for providing resources and continuous support in the implementation of the ReWire project. Acknowledgment is also extended to the Slovenian Research and Innovation Agency (ARIS) programme group P2-0273. Further appreciation goes to the Faculty of Textile Technology and the Faculty of Chemical Engineering and Technology for providing access to their laboratories, which enabled the testing necessary for this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Official Journal of the European Communities. L182 Directive 1999/31/EC of the Council of 26 April 1999 on the Landfill of Waste; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 1999; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Official Journal of the European Union. L334 Directive 2010/75/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 24 November 2010 on Industrial Emissions (Integrated Pollution Prevention and Control); European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2010; pp. 17–119. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Z.; Pramanik, A.; Basak, A.K.; Prakash, C.; Shankar, S. Material recovery and recycling of waste tyres-A review. Clean. Mater. 2022, 5, 100115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astute Analytica Tire Recycling Market: Market Size, Industry Dynamics, Opportunity Analysis and Forecast for 2025–2033. 2025. Available online: https://www.astuteanalytica.com/industry-report/tire-recycling-market (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Parres, F.; Crespo-Amorós, J.E.; Nadal-Gisbert, A. Characterization of Fibers Obtained from Shredded Tires. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2009, 113, 2053–2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onuaguluchi, O.; Banthia, N. Durability performance of polymeric scrap tire fibers and its reinforced cement mortar. Mater. Struct. Constr. 2017, 50, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baričević, A.; Jelčić Rukavina, M.; Pezer, M.; Štirmer, N. Influence of recycled tire polymer fibers on concrete properties. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2018, 91, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrduljaš, B.; Baričević, A.; Pucić, I.; Carević, I.; Didulica, K. Alkali resistance of selected waste fibres to model cement environment. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 19, e02411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Farzadnia, N.; Shi, C.; Ma, X. Shrinkage and strength development of UHSC incorporating a hybrid system of SAP and SRA. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2019, 97, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamashiro, J.R.; Angel de la Rubia, M.; Rubio-Marcos, F.; Rojas-Hernandez, R.E.; Silva, L.H.P.; de Paiva, F.F.G.; Kinoshita, A.; Terrades, A.M. Doping engineering for controlled hydration and mechanical properties in Portland cement mortar with ultra-low ZnO concentration. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 78, 107748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.Q.; Li, S.; Ji, B.; Zhao, X.; Rahat, M.H.H.; Nguyen, T.N.; Le, B.C.; Zhang, W.; Brand, A.S. Mitigation of zinc and organic carbon leached from end-of-life tire rubber in cementitious composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 432, 136589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrduljaš, B.; Mauko Pranjić, A.; Štefančic, M.; Didulica, K.; Baričević, A. Influence of Alkali-resistant Glass Fibers Distribution on Properties of Cementitious Composites. In Durability of Building Materials and Components for Sustainability; Li, K., Fang, D., Eds.; Tsinghua University: Beijing, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, H.; Chen, M.; Zhang, M. Engineering properties of sustainable engineered cementitious composites with recycled tyre polymer fibres. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 370, 130672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Sun, Z.; Tu, W.; Yan, X.; Zhang, M. Behaviour of recycled tyre polymer fibre reinforced concrete at elevated temperatures. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2021, 124, 104257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serdar, M.; Baričević, A.; Jelčić Rukavina, M.; Pezer, M.; Bjegović, D.; Štirmer, N. Shrinkage Behaviour of Fibre Reinforced Concrete with Recycled Tyre Polymer Fibres. Int. J. Polym. Sci. 2015, 2015, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baričević, A.; Pezer, M.; Jelčić Rukavina, M.; Serdar, M.; Štirmer, N. Effect of polymer fibers recycled from waste tires on properties of wet-sprayed concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 176, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Feng, P.; Lyu, C.; Ye, S. The role of sulfate ions in tricalcium aluminate hydration: New insights. Cem. Concr. Res. 2020, 130, 105973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, P.K.; Monteiro, P.J.M. Concrete: Structure, Properties and Materials, 4th ed.; McGraw-Hill: Columbus, OH, USA, 1986; Volume 8. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, N.P.; Gunasekara, C.; Law, D.W.; Houshyar, S.; Setunge, S.; Cwirzen, A. A critical review on drying shrinkage mitigation strategies in cement-based materials. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 38, 102210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aïtcin, P.C. Portland Cement; Elsevier Ltd.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Marchon, D.; Flatt, R.J. Mechanisms of Cement Hydration; Elsevier Ltd.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.H.; Sisomphon, K.; Ng, T.S.; Sun, D.J. Effect of superplasticizers on workability retention and initial setting time of cement pastes. Constr. Build. Mater. 2010, 24, 1700–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Daake, H.; Stephan, D. Setting of cement with controlled superplasticizer addition monitored by ultrasonic measurements and calorimetry. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2016, 66, 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Yu, Q.; Brouwers, H.J. Effect of PCE-type superplasticizer on early-age behaviour of ultra-high performance concrete (UHPC). Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 153, 740–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abadassi, M.; El Bitouri, Y.; Azéma, N.; Garcia-Diaz, E. Effect of Excessive Bleeding on the Properties of Cement Mortar. Constr. Mater. 2023, 3, 164–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eik, M.; Antonova, A.; Puttonen, J. Phase contrast tomography to study near-field effects of polypropylene fibres on hardened cement paste. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2020, 114, 103800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultangaliyeva, F.; Carré, H.; La Borderie, C.; Zuo, W.; Keita, E.; Roussel, N. Influence of flexible fibers on the yield stress of fresh cement pastes and mortars. Cem. Concr. Res. 2020, 138, 106221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Li, Z.; Yang, E.H. Quantitative characterization of anisotropic properties of the interfacial transition zone (ITZ) between microfiber and cement paste. Cem. Concr. Res. 2019, 122, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Chen, Y.; Liang, M.; Yang, E.H.; Schlangen, E. Distribution of porosity surrounding a microfiber in cement paste. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2023, 142, 105188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Kanstad, T.; Jacobsen, S.; Ji, G. Bonding property between fiber and cementitious matrix: A critical review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 378, 131169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassimi, F.; Khayat, K.H. Shrinkage of high-performance fiber-reinforced concrete with adapted rheology. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 232, 117234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohajerani, A.; Hui, S.Q.; Mirzababaei, M.; Arulrajah, A.; Horpibulsuk, S.; Kadir, A.A.; Rahman, M.T.; Maghool, F. Amazing types, properties, and applications of fibres in construction materials. Materials 2019, 12, 2513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Li, Q.; Huang, B.; Liu, X.; Xu, S. Effects of PVA fibers on microstructures and hydration products of cementitious composites with and without fly ash. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 360, 129533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machovič, V.; Lapčák, L.; Borecká, L.; Lhotka, M.; Andertová, J.; Kopecký, L.; Mišková, L. Microstructure of interfacial transition zone between PET fibres and cement paste. Acta Geodyn. Geomater. 2013, 10, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, N.P.; Gunasekara, C.; Law, D.W.; Houshyar, S.; Setunge, S. Microstructural characterisation of cementitious composite incorporating polymeric fibre: A comprehensive review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 335, 127497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamage, N.; Patrisia, Y.; Gunasekara, C.; Law, D.W.; Houshyar, S.; Setunge, S. Shrinkage induced crack control of concrete integrating synthetic textile and natural cellulosic fibres: Comparative review analysis. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 427, 136275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakravan, H.R.; Ozbakkaloglu, T. Synthetic fibers for cementitious composites: A critical and in-depth review of recent advances. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 207, 491–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostami, R.; Zarrebini, M.; Mandegari, M.; Mostofinejad, D.; Abtahi, S.M. A review on performance of polyester fibers in alkaline and cementitious composites environments. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 241, 117998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.C. Hydration and internal curing properties of plant-based natural fiber-reinforced cement composites. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2022, 17, e01690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.X.; Pel, L.; Smeulders, D. Influence of water-soluble leachates from natural fibers on the hydration and microstructure of cement paste studied by nuclear magnetic resonance. Cem. Concr. Res. 2024, 185, 107629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.X.; Ji, Y.L.; Pel, L.; Sun, Z.; Smeulders, D. Early-age hydration and shrinkage of cement paste with coir fibers as studied by Nuclear Magnetic Resonance. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 336, 127460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C204-18e1; Test Methods for Fineness of Hydraulic Cement by Air-Permeability Apparatus. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2018.

- ASTM D2402; Test Method for Water Retention of Textile Fibers (Centrifuge Procedure). ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2018.

- EN 1015-3:1999/A1:2004; Methods of Test for Mortar for Masonry—Part 3: Determination of Consistence of Fresh Mortar (by Flow Table), Adopted as HRN EN 1015-3:2000/A1:2005. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2005.

- EN 196-3:2005; Methods of Testing Cement—Part 3: Determination of Setting Times and Soundness, Adopted as HRN EN 196-3:2009. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2009.

- Gwon, S.; Choi, Y.C.; Shin, M. Internal curing of cement composites using kenaf cellulose microfibers. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 47, 103867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Ge, Z.; Wang, K. Influence of cement fineness and water-to-cement ratio on mortar early-age heat of hydration and set times. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 50, 657–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saladi, N.; Montanari, L.; Mohebbi, A.; Cooper, M.A.; Graybeal, B. Assessing the setting behavior of ultra-high performance concrete. Mater. Struct. 2024, 57, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linderoth, O.; Wadsö, L.; Jansen, D. Long-term cement hydration studies with isothermal calorimetry. Cem. Concr. Res. 2021, 141, 106344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C1698-19; Standard Test Method for Autogenous Strain of Cement Paste and Mortar. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2019.

- EN 1015-11:2019; Methods of Test for Mortar for Masonry—Part 11: Determination of Flexural and Compressive Strength of Hardened Mortar, Adopted as HRN EN 1015-11:2019. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2019.

- Zhutovsky, S.; Kovler, K. Effect of internal curing on durability-related properties of high performance concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 2012, 42, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyrzykowski, M.; Lura, P. Effect of relative humidity decrease due to self-desiccation on the hydration kinetics of cement. Cem. Concr. Res. 2016, 85, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scrivener, K.; Snellings, R.; Lothenbach, B. A Practical Guide to Microstructural Analysis of Cementitious Materials, 1st ed.; Scrivener, K., Snellings, R., Lothenbach, B., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Moro, F.; Böhni, H. Ink-bottle effect in mercury intrusion porosimetry of cement-based materials. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2002, 246, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohr, B.J.; Hood, K.L. Influence of bleed water reabsorption on cement paste autogenous deformation. Cem. Concr. Res. 2010, 40, 220–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Chen, W.; Zhong, H.; Chi, D.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, M. Experimental study on dynamic compressive behaviour of recycled tyre polymer fibre reinforced concrete. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2019, 98, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emdadi, A.; Mehdipour, I.; Libre, N.A.; Shekarchi, M. Optimized workability and mechanical properties of FRCM by using fiber factor approach: Theoretical and experimental study. Mater. Struct. 2015, 48, 1149–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grünewald, S. Fibre Reinforcement and the Rheology of Concrete; Roussel, N., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing Limited: Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Khayat, K.H.; Meng, W.; Vallurupalli, K.; Teng, L. Rheological properties of ultra-high-performance concrete—An overview. Cem. Concr. Res. 2019, 124, 105828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Deng, F.; Chi, Y. Nano-mechanical behavior of the interfacial transition zone between steel-polypropylene fiber and cement paste. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 145, 619–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).